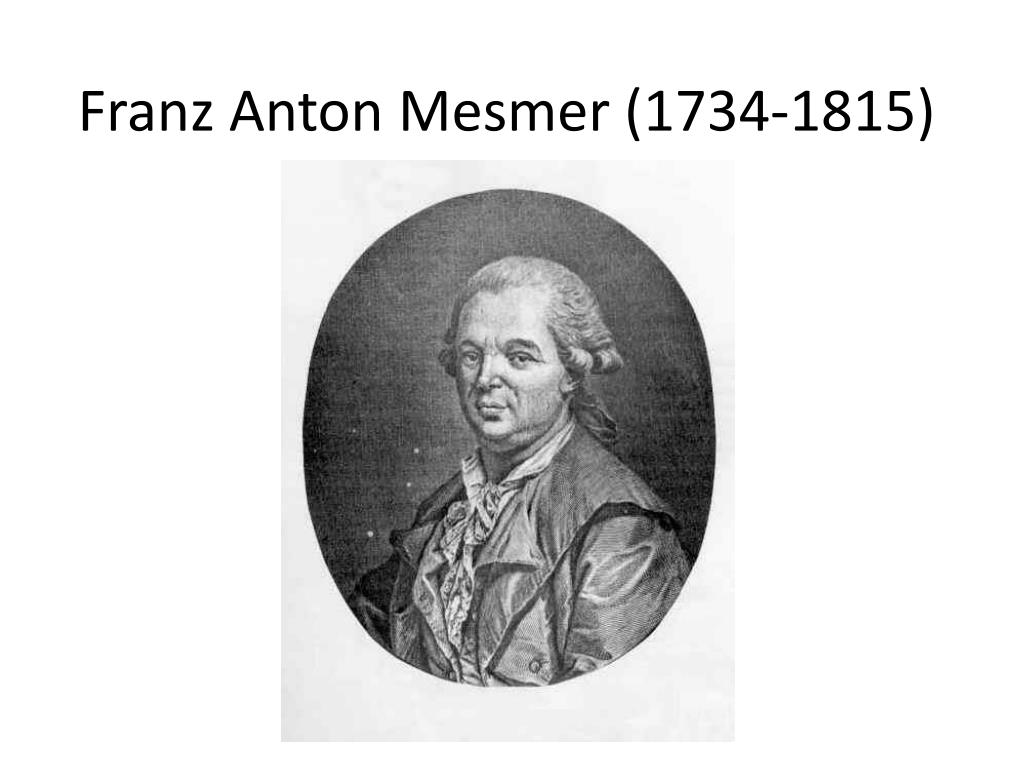

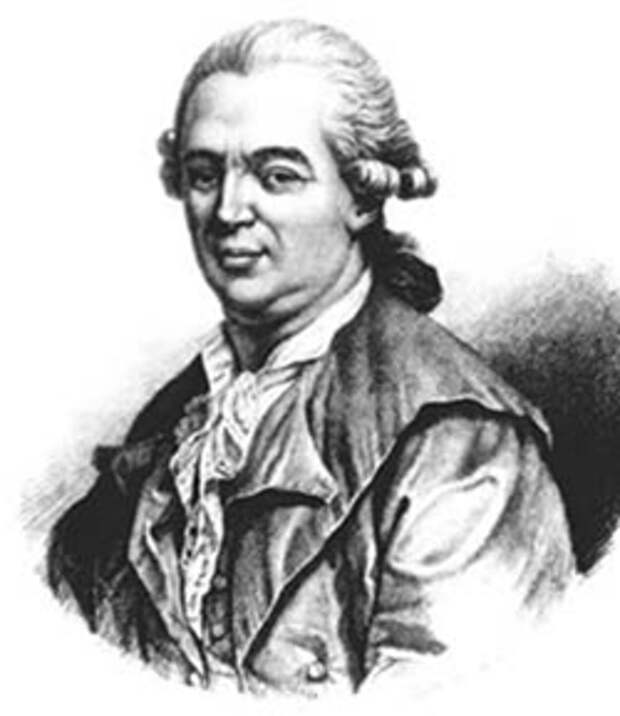

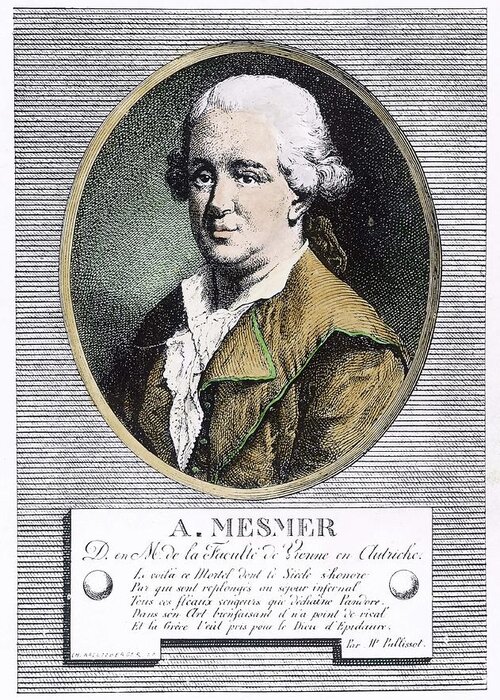

Dr anton mesmer

hypnosis | Definition, History, Techniques, & Facts

- Key People:

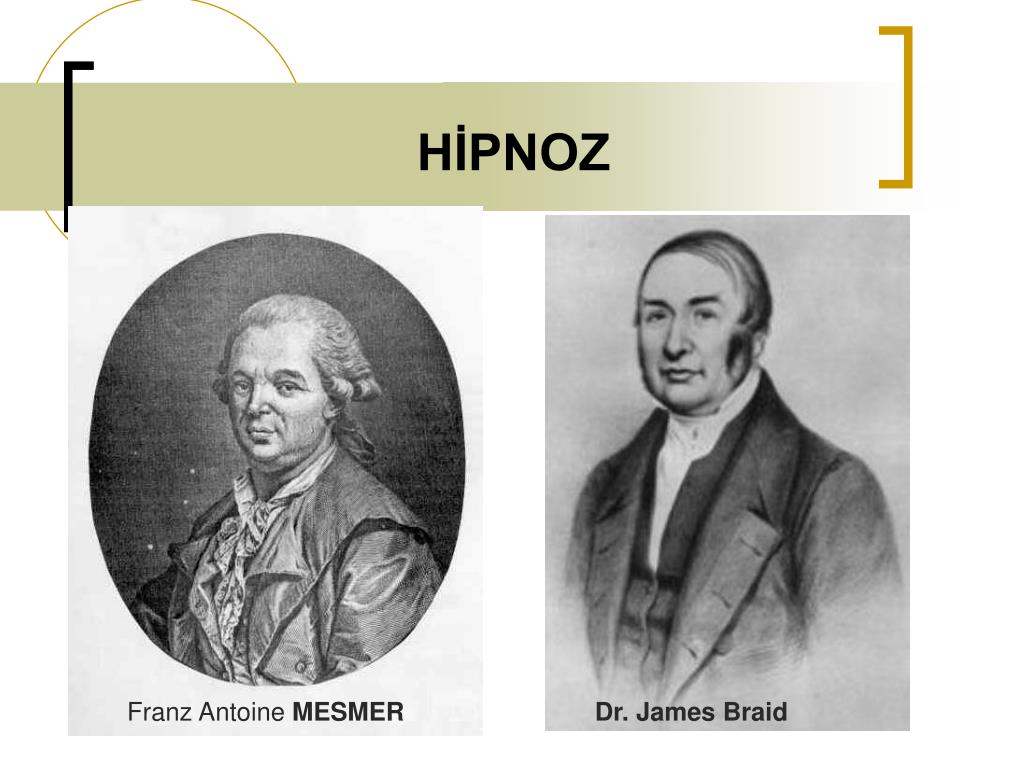

- Josef Breuer James Braid John Elliotson Clark L. Hull Franz Anton Mesmer

- Related Topics:

- autohypnosis animal magnetism trance posthypnotic amnesia posthypnotic suggestion

See all related content →

Summary

Read a brief summary of this topic

hypnosis, special psychological state with certain physiological attributes, resembling sleep only superficially and marked by a functioning of the individual at a level of awareness other than the ordinary conscious state. This state is characterized by a degree of increased receptiveness and responsiveness in which inner experiential perceptions are given as much significance as is generally given only to external reality.

The hypnotic state

The hypnotized individual appears to heed only the communications of the hypnotist and typically responds in an uncritical, automatic fashion while ignoring all aspects of the environment other than those pointed out by the hypnotist. In a hypnotic state an individual tends to see, feel, smell, and otherwise perceive in accordance with the hypnotist’s suggestions, even though these suggestions may be in apparent contradiction to the actual stimuli present in the environment. The effects of hypnosis are not limited to sensory change; even the subject’s memory and awareness of self may be altered by suggestion, and the effects of the suggestions may be extended (posthypnotically) into the subject’s subsequent waking activity.

Britannica Quiz

Introduction to Psychology Quiz

Psychology is a scientific discipline that studies mental states and behavior in humans and other animals, according to Britannica. How much do you know about it?

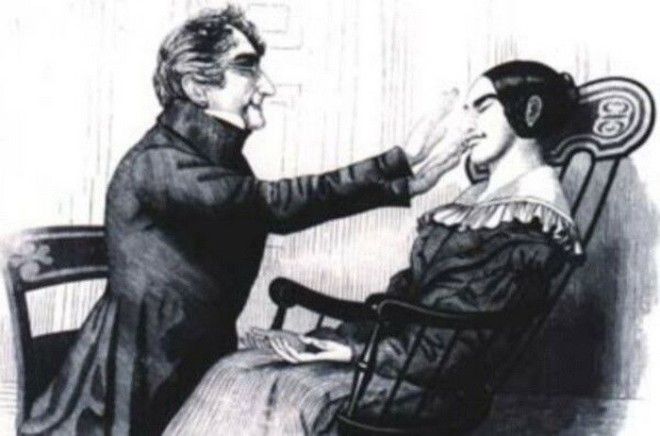

History and early research

The history of hypnosis is as ancient as that of sorcery, magic, and medicine; indeed, hypnosis has been used as a method in all three. Its scientific history began in the latter part of the 18th century with Franz Mesmer, a German physician who used hypnosis in the treatment of patients in Vienna and Paris. Because of his mistaken belief that hypnotism made use of an occult force (which he termed “animal magnetism”) that flowed through the hypnotist into the subject, Mesmer was soon discredited; but Mesmer’s method—named mesmerism after its creator—continued to interest medical practitioners. A number of clinicians made use of it without fully understanding its nature until the middle of the 19th century, when the English physician James Braid studied the phenomenon and coined the terms hypnotism and hypnosis, after the Greek god of sleep, Hypnos.

Because of his mistaken belief that hypnotism made use of an occult force (which he termed “animal magnetism”) that flowed through the hypnotist into the subject, Mesmer was soon discredited; but Mesmer’s method—named mesmerism after its creator—continued to interest medical practitioners. A number of clinicians made use of it without fully understanding its nature until the middle of the 19th century, when the English physician James Braid studied the phenomenon and coined the terms hypnotism and hypnosis, after the Greek god of sleep, Hypnos.

Hypnosis attracted widespread scientific interest in the 1880s. Ambroise-Auguste Liébeault, an obscure French country physician who used mesmeric techniques, drew the support of Hippolyte Bernheim, a professor of medicine at Strasbourg. Independently they had written that hypnosis involved no physical forces and no physiological processes but was a combination of psychologically mediated responses to suggestions. During a visit to France at about the same time, Austrian physician Sigmund Freud was impressed by the therapeutic potential of hypnosis for neurotic disorders. On his return to Vienna, he used hypnosis to help neurotics recall disturbing events that they had apparently forgotten. As he began to develop his system of psychoanalysis, however, theoretical considerations—as well as the difficulty he encountered in hypnotizing some patients—led Freud to discard hypnosis in favour of free association. (Generally psychoanalysts have come to view hypnosis as merely an adjunct to the free-associative techniques used in psychoanalytic practice.)

On his return to Vienna, he used hypnosis to help neurotics recall disturbing events that they had apparently forgotten. As he began to develop his system of psychoanalysis, however, theoretical considerations—as well as the difficulty he encountered in hypnotizing some patients—led Freud to discard hypnosis in favour of free association. (Generally psychoanalysts have come to view hypnosis as merely an adjunct to the free-associative techniques used in psychoanalytic practice.)

Despite Freud’s influential adoption and then rejection of hypnosis, some use was made of the technique in the psychoanalytic treatment of soldiers who had experienced combat neuroses during World Wars I and II. Hypnosis subsequently acquired other limited uses in medicine. Various researchers have put forth differing theories of what hypnosis is and how it might be understood, but there is still no generally accepted explanatory theory for the phenomenon.

Applications of hypnosis

The techniques used to induce hypnosis share common features. The most important consideration is that the person to be hypnotized (the subject) be willing and cooperative and that he or she trust in the hypnotist. Subjects are invited to relax in comfort and to fix their gaze on some object. The hypnotist continues to suggest, usually in a low, quiet voice, that the subject’s relaxation will increase and that his or her eyes will grow tired. Soon the subject’s eyes do show signs of fatigue, and the hypnotist suggests that they will close. The subject allows his eyes to close and then begins to show signs of profound relaxation, such as limpness and deep breathing. He has entered the state of hypnotic trance. A person will be more responsive to hypnosis when he believes that he can be hypnotized, that the hypnotist is competent and trustworthy, and that the undertaking is safe, appropriate, and congruent with the subject’s wishes. Therefore, induction is generally preceded by the establishment of suitable rapport between subject and hypnotist.

The most important consideration is that the person to be hypnotized (the subject) be willing and cooperative and that he or she trust in the hypnotist. Subjects are invited to relax in comfort and to fix their gaze on some object. The hypnotist continues to suggest, usually in a low, quiet voice, that the subject’s relaxation will increase and that his or her eyes will grow tired. Soon the subject’s eyes do show signs of fatigue, and the hypnotist suggests that they will close. The subject allows his eyes to close and then begins to show signs of profound relaxation, such as limpness and deep breathing. He has entered the state of hypnotic trance. A person will be more responsive to hypnosis when he believes that he can be hypnotized, that the hypnotist is competent and trustworthy, and that the undertaking is safe, appropriate, and congruent with the subject’s wishes. Therefore, induction is generally preceded by the establishment of suitable rapport between subject and hypnotist.

Get a Britannica Premium subscription and gain access to exclusive content. Subscribe Now

Subscribe Now

Ordinary inductions of hypnosis begin with simple, noncontroversial suggestions made by the hypnotist that will almost inevitably be accepted by all subjects. At this stage neither subject nor hypnotist can readily tell whether the subject’s behaviour constitutes a hypnotic response or mere cooperation. Then, gradually, suggestions are given that demand increasing distortion of the individual’s perception or memory—e.g., that it is difficult or impossible for the subject to open his or her eyes. Other methods of induction may also be used. The process may take considerable time or only a few seconds.

The resulting hypnotic phenomena differ markedly from one subject to another and from one trance to another, depending upon the purposes to be served and the depth of the trance. Hypnosis is a phenomenon of degrees, ranging from light to profound trance states but with no fixed constancy. Ordinarily, however, all trance behaviour is characterized by a simplicity, a directness, and a literalness of understanding, action, and emotional response that are suggestive of childhood. The surprising abilities displayed by some hypnotized persons seem to derive partly from the restriction of their attention to the task or situation at hand and their consequent freedom from the ordinary conscious tendency to orient constantly to distracting, even irrelevant, events.

The surprising abilities displayed by some hypnotized persons seem to derive partly from the restriction of their attention to the task or situation at hand and their consequent freedom from the ordinary conscious tendency to orient constantly to distracting, even irrelevant, events.

The central phenomenon of hypnosis is suggestibility, a state of greatly enhanced receptiveness and responsiveness to suggestions and stimuli presented by the hypnotist. Appropriate suggestions by the hypnotist can induce a remarkably wide range of psychological, sensory, and motor responses from persons who are deeply hypnotized. By acceptance of and response to suggestions, the subject can be induced to behave as if deaf, blind, paralyzed, hallucinated, delusional, amnesic, or impervious to pain or to uncomfortable body postures; in addition, the subject can display various behavioral responses that he or she regards as a reasonable or desirable response to the situation that has been suggested by the hypnotist.

One fascinating manifestation that can be elicited from a subject who has been in a hypnotic trance is that of posthypnotic suggestion and behaviour; that is, the subject’s execution, at some later time, of instructions and suggestions that were given to him while he was in a trance. With adequate amnesia induced during the trance state, the individual will not be aware of the source of his impulse to perform the instructed act. Posthypnotic suggestion, however, is not a particularly powerful means for controlling behaviour when compared with a person’s conscious willingness to perform actions.

Many subjects seem unable to recall events that occurred while they were in deep hypnosis. This “posthypnotic amnesia” can result either spontaneously from deep hypnosis or from a suggestion by the hypnotist while the subject is in a trance state. The amnesia may include all the events of the trance state or only selected items, or it may be manifested in connection with matters unrelated to the trance. Posthypnotic amnesia may be successfully removed by appropriate hypnotic suggestions.

Posthypnotic amnesia may be successfully removed by appropriate hypnotic suggestions.

Hypnosis has been officially endorsed as a therapeutic method by medical, psychiatric, dental, and psychological associations throughout the world. It has been found most useful in preparing people for anesthesia, enhancing the drug response, and reducing the required dosage. In childbirth it is particularly helpful, because it can help to alleviate the mother’s discomfort while avoiding anesthetics that could impair the child’s physiological function. Hypnosis has often been used in attempts to stop smoking, and it is highly regarded in the management of otherwise intractable pain, including that of terminal cancer. It is valuable in reducing the common fear of dental procedures; in fact, the very people whom dentists find most difficult to treat frequently respond best to hypnotic suggestion. In the area of psychosomatic medicine, hypnosis has been used in a variety of ways. Patients have been trained to relax and to carry out, in the absence of the hypnotist, exercises that have had salutary effects on some forms of high blood pressure, headaches, and functional disorders.

Though the induction of hypnosis requires little training and no particular skill, when used in the context of medical treatment, it can be damaging when employed by individuals who lack the competence and skill to treat such problems without the use of hypnosis. On the other hand, hypnosis has been repeatedly condemned by various medical associations when it is used purely for purposes of public entertainment, owing to the danger of adverse posthypnotic reactions to the procedure. Indeed, in this regard several nations have banned or limited commercial or other public displays of hypnosis. In addition, many courts of law refuse to accept testimony from people who have been hypnotized for purposes of “recovering” memories, because such techniques can lead to confusion between imaginations and memories.

Martin T. Orne A. Gordon Hammer The Editors of Encyclopaedia BritannicaSwabia | historical region, Germany

- Key People:

- Walafrid Strabo Franz Anton Mesmer Franz, Freiherr von Mercy Hatto I J.

A. Bengel

A. Bengel

- Related Places:

- Germany

See all related content →

Summary

Read a brief summary of this topic

Swabia, German Schwaben, historic region of southwestern Germany, including what is now the southern portion of Baden-Württemberg Land (state) and the southwestern part of Bavaria Land in Germany, as well as eastern Switzerland and Alsace.

Swabia’s name is derived from that of the Suebi, a Germanic people who, with the Alemanni, occupied the upper Rhine and upper Danube region in the 3rd century ad and spread south to Lake Constance and east to the Lech River. Known first as Alemannia, the region was called Swabia from the 11th century. The Franks under Clovis mastered the Alemanni about ad 500; later in the 6th century, the Franks established a duchy in Alemannia to control the region, which gained autonomy under the later Merovingians but lost it under the Carolingians. The Lex Alemannorum, a code based on Alemannic customary law, first emerged in the 7th century. By the 7th century Irish missionaries began to introduce Christianity. Centres of Christian activity included the abbeys of St. Gall and of Reichenau and the bishoprics of Basel, Constance, and Augsburg; most Swabian sees came into the archepiscopal province of Mainz.

The Lex Alemannorum, a code based on Alemannic customary law, first emerged in the 7th century. By the 7th century Irish missionaries began to introduce Christianity. Centres of Christian activity included the abbeys of St. Gall and of Reichenau and the bishoprics of Basel, Constance, and Augsburg; most Swabian sees came into the archepiscopal province of Mainz.

Britannica Quiz

History: Fact or Fiction?

Get hooked on history as this quiz sorts out the past. Find out who really invented movable type, who Winston Churchill called "Mum," and when the first sonic boom was heard.

Swabia was one of the five great Stamm (stem, or tribal) duchies of earlier medieval Germany—with Franconia, Saxony, Bavaria, and Lotharingia (Lorraine)—and was held by successive families. Rudolf of Rheinfelden, duke in 1057, was set up as German king in 1077 in opposition to Henry IV, who in 1079 appointed the rebel’s son-in-law, Frederick I of Hohenstaufen, duke of Swabia. Frederick’s grandson was elected German king as Frederick I Barbarossa in 1152; and Swabia remained a dynastic possession of the Hohenstaufen until the extinction of their male line in 1268. Thereafter, local nobles, especially the counts of Württemberg, appropriated the ducal and royal lands. The German king Rudolf of Habsburg salvaged parts of the duchy for his son, Rudolf II of Austria; but by 1313, with the death of the latter’s son, the ducal title fell out of use.

Thereafter, local nobles, especially the counts of Württemberg, appropriated the ducal and royal lands. The German king Rudolf of Habsburg salvaged parts of the duchy for his son, Rudolf II of Austria; but by 1313, with the death of the latter’s son, the ducal title fell out of use.

In the late European Middle Ages the so-called Swabian leagues played an important part in changing struggles between cities supported by the Holy Roman emperor, territorial magnates, and petty nobility. In 1321, in the first league, 22 Swabian imperial (free) cities, including Ulm and Augsburg, banded together to support Emperor Louis IV in return for his undertaking not to mortgage any of them to a vassal; Count Ulrich III of Württemberg was induced to join them in 1340. In opposition, the Swabian knights in 1366 formed their own league, the Schleglerbund (from the German Schlegel, “Mallet,” or “Hammer,” on their insignia). In the ensuing civil war, Eberhard II, Ulrich III’s son and successor, joined by the Schleglerbund, defeated the Swabian cities in 1372.

Ulm organized a new league of 14 Swabian imperial cities in 1376 with the aims of protecting the members’ status against the threat of mortgaging and safeguarding their commercial interests. In 1377 this new league defeated Eberhard II’s son Ulrich at Reutlingen, and it was a force in southern Germany until Eberhard II defeated it in 1388. In 1395 Eberhard III of Württemberg toppled the Schleglerbund by taking its fortress at Heimsheim.

In 1488 a new, more comprehensive Swabian league was formed, at Esslingen, not only of 22 imperial cities but also of the Swabian knights’ League of St. George’s Shield, bishops, and princes (Tirol, Württemberg, the Palatinate, Mainz, Trier, Baden, Hesse, Bavaria, Ansbach, and Bayreuth). The league was governed by a federal council of three colleges of princes, cities, and knights calling upon an army of 13,000 men. It aided in the rescue of the future emperor Maximilian I, Frederick III’s son, held prisoner in the Netherlands, and later was his main support in southern Germany. It helped to suppress the Peasants’ Revolt (1524–25). The Reformation caused the league to be disbanded in 1534.

It helped to suppress the Peasants’ Revolt (1524–25). The Reformation caused the league to be disbanded in 1534.

Get a Britannica Premium subscription and gain access to exclusive content. Subscribe Now

The name of Swabia was perpetuated in that of the Swabian Kreis (“circle,” or administrative district), one of the zones into which Germany was divided, from the 16th century onward, for purposes of imperial administration. First organized in 1500, the Swabian Kreis was fully established in 1555 and lasted until the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806. There was also a Swabian Bench of Cities in the old imperial Diet (Reichstag).

Mesmer Franz Anton | |

1734-1815 | CV |

XPOHOCPROJECT INTRODUCTIONCHRONOS FORUMCHRONOS NEWSCHRONOS LIBRARYHISTORICAL SOURCESCVINDEXGENEALOGY CHARTSCOUNTRIES AND STATESETHNONYMSRELIGIONS OF THE WORLDHISTORICAL ARTICLESTEACHING METHODOLOGYSITE MAPAUTHORS OF CHRONOSRelated projects:RUMYANTSEV MUSEUMDOCUMENTS OF THE XX CENTURYHISTORICAL GEOGRAPHYRULERS OF THE WORLDWAR OF 1812WORLD ISLAVYETHNOCYCLOPEDIAAPSUARARUSSIAN FIELD | Franz Anton Mesmer Mesmer Franz Anton (1734-1815) - Austrian physician, founder of the doctrine animal magnetism ("mesmerism"). Kondakov I.M. Psychology. Illustrated dictionary. // THEM. Kondakov. - 2nd ed. add. And a reworker. - St. Petersburg, 2007, p. 325-326. Read more:Historical persons of Austria (biographical handbook) Compositions:Memorie sur la Decouverte du Magnetisme Animal. Carlsruhe: Michel Maklot, 1781; Aphorismes de m. Mesmei dictes a l'assemblee de ses eleves. P.: Quinquet, 1785. Literature:Shertok L., Saussure R. The Birth of the Psychoanalyst: From Mesmer to Freud. M.: Progress, 1991.

|

|

| CHRONOS: WORLD HISTORY ON THE INTERNET |

| | CHRONOS exists since January 20, 2000,Editor Vyacheslav RumyantsevWhen quoting, give a link to CHRONOS |

Franz Anton Mesmer - frwiki.

wiki

wiki "Mesmer" redirects here. For the Canadian artist, see Messmer (hypnotist).

Franz Anton Mesmer , born in Moos and died in Meersburg - German physician from the country of Baden, founder of the theory of animal magnetism or mesmerism.

Summary

- 1 Biography

- 1.1 Family origin

- 1.2 Postgraduate studies (1752-1766)

- 1.3 Vienna (1768-1777)

- 1.3.1 First case

- 1.3.2 The Beginning of Glory

- 1.4 Paris (1778-1785)

- 1.4.1 Mesmer plant in Paris

- 1.4.2 Mesmer's theories (1779)

- 1.4.3 Bucket method (1780)

- 1.4.4 Society for General Harmony (1784)

- 1.4.5 Study of the practices of Mesmer (1784)

- 1.4.6 Crisis of 1784-1785 and departure from France

- 1.

5 Last travels (1786-1815)

5 Last travels (1786-1815) - 1.5.1 Revolutionary period

- 1.5.2 Frauenfeld

- 2 Personality

- 2.1 Music sponsorship

- 2.2 Character

- 3 points of view

- 3.1 Quack Doctor

- 3.2 Pioneer doctor

- 3.3 Doctor of Enlightenment

- 4 Works

- 5 Offspring

- 6 Notes and references

- 7 See also

- 7.1 Bibliography

- 7.2 Related Articles

- 7.3 External links

biography

family background

He was born in the village of Iznang, on the shores of Lake Constance, where his father, Anton, was a master forester in the service of the Prince-Bishop of Constance. Nothing is known about his childhood and youth until the age of 18.

Postgraduate studies (1752-1766)

In 1752, Franz Anton Mesmer entered the Jesuit University of Dillingen (de), where he studied theology; in 1754 he entered the University of Ingolstadt for the third year of theology.

Then he entered the law faculty of the University of Vienna (1759BC), then to medicine (1760).

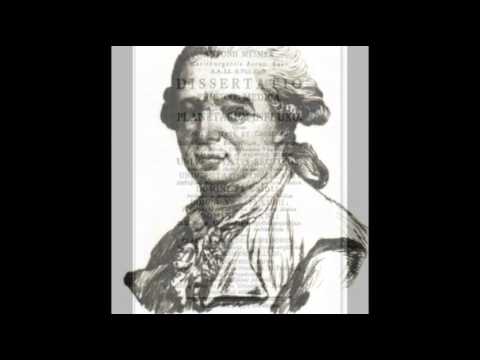

In 1766, at the age of 33, Mesmer published his doctoral thesis in medicine: Dissertatio Physico-medica de planetarum Infxu On the influence of the planets on the human body , in which we find the influence of the theories of the Belgian physician Jan Baptist van Helmont ( " Magnetic treatment of wounds ", 1621), the German Jesuit Athanasius Kircher and the English astronomer Isaac Newton.

According to the authors, Mesmer here is under the influence of occultism or iatro-mechanism (mechanism in medicine). For Robert Darton, this dissertation is just a mixture of astrology and Newtonism. According to Rauska, he is not exactly an occultist, as he is far-sighted and cares little about the fidelity of ancient tradition, nor is he "iatromechanic" because he does not seek measurements or experimentation.

This thesis gives rise to a concept, still vague, but which he will develop later, the concept of "animal gravity": influences between people of the same cosmic order as the influences of stars between them.

Vienna (1768-1777)

In January 1768, Mesmer married the wealthy widow Maria Anna von Posch (called "von Bosch" in Mozart's correspondence). Many Viennese musicians visit their house frequently, especially Haydn, Gluck and Leopold Mozart (see Music Sponsorship section).

First case

In 1773, he treated a 27-year-old patient, Miss Osterlin, in his own home, who had repeated painful and convulsive attacks. He has just learned that English doctors use magnets to treat certain diseases.

The first attempts with iron magnets were unsuccessful, he attributed the failures to the imperfection of the magnets. He then uses magnetic plates invented by the Jesuit Father Maximilian Hell, an astronomer at the court of Vienna. It adapts the shape of these plates to the part of the body being treated.

On July 28, 1774, Mesmer reported that he forced his patient to swallow a mixture containing iron, and then attached three magnets to his body: one on his stomach, another on each leg.![]() Thus, it causes a crisis or "artificial flush", the patient is cured of this attack by becoming insensitive to the magnets.

Thus, it causes a crisis or "artificial flush", the patient is cured of this attack by becoming insensitive to the magnets.

Miss Esterlin improves to the point that she marries Mesmer's stepson (son of the widow von Posch).

After arguing with Hell over the paternity of this process, Mesmer will insist on the fact that animal magnetism is different from mineral ferrofluid. He interprets his patient's healing as coming from his own magnetic fluid, with the magnets playing only an amplifying and guiding role.

Mesmer transforms an ancient occult, fetishistic and magical tradition that attributed magnetic and mysterious powers to individual parts of the human body (strands of hair, anatomical relics...). He believes that it is the therapist, the living person in his totality, who can heal and alleviate with his personal magnetism.

Celebrity debut

Mesmer with his magnet, the "magic column" by sculptor Peter Lenk, located in Meersburg.

In June 1775 he went to Baron Gorecki de Gorka, a Hungarian nobleman in Slovakia, to be cured of his nervous spasms. On this occasion, there is evidence of a tutor of the baron's house, who watched Mesmer, trying to expose him as a charlatan. This mentor named Seifert reports that Mesmer carried magnets with him, including in his bed, and that he admitted that his magnetic power was weaker than that of the exorcist father Johann Joseph Gassner.

At the end of 1775, Mesmer was convinced that with the help of magnets he could surpass Gassner. He achieved several sensational cures. The Prince Elector summons him to Munich to demonstrate his abilities. He was appointed a member of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences, giving his opinion on Gassner, whom he considered to be endowed with extraordinary magnetic power.

In 1776-1777 he treated the blindness of Maria Theresa von Paradis, an 18-year-old musician who had been blind since the age of four. Mesmer manages to partially restore his vision, for which his parents were initially very grateful to him. But the doctors who attended to the musician dispute the cure: they emphasize that the patient claims to see only in the presence of Mesmer.

But the doctors who attended to the musician dispute the cure: they emphasize that the patient claims to see only in the presence of Mesmer.

After a conflict between Mesmer and the Paradis family, the musician interrupts her treatment. According to Mesmer, neither the family nor the patient were interested in a cure, it would have been the end of the career of a blind musician and the generosity of the Austrian Empress.

Paris (1778-1785)

Mesmer's departure from Vienna to Paris is the subject of several interpretations. He would have been forced to leave due to his failure with Heaven and the hostility of his colleagues. It is also said that the young patient fell in love with Mesmer, who would not remain indifferent.

According to Ellenberger, the real reason for his departure was his hypersensitive and unstable nature. At the end of 1777, Mesmer is going through a phase of depression, he walks through the forest, talking to the trees. Gradually, he gains self-confidence and sets himself the task of making his discovery known to the whole world. So he left for Paris in February 1778, he left Vienna, but also his wife, whom he would never see again.

So he left for Paris in February 1778, he left Vienna, but also his wife, whom he would never see again.

Mesmer installation in Paris

Parisian atmosphere is different from Vienna. Unlike the Austrian Empire, which was endowed with a stable and vigorous government, a solid administration and an efficient police force, life in Paris is hectic, under weak and unstable political power and a corrupt economy. During the Franco-British War, the Parisian public was enthusiastic about American independence and was ready to move from one fad to another.

He first settled in Créteil in May 1778, his clientele growing, then he judged at the Hôtel Bourret on the Vendôme then at the Hôtel Bullion on the corner of the Rue Coq-Heron (today n o 9) and Orléans-Saint-Honore ( now rue du Louvre), near Saint-Eustache, and again at the Hôtel de Coigny on rue Coq-Héron. He accepts high society patients to get their attention, demanding exorbitant fees.

He really wants to contact the academic authorities. He was assisted by Charles Deslon, personal physician to the Comte d'Artois (the king's brother), with whose support he published in 1779 his 88-page memoirs of the discovery of animal magnetism followed by his 27 famous sentences describing his theory.

Mesmer's Theories (1779)

His 27 suggestions can be summed up in four fundamental principles:

- a subtle physical fluid fills the universe, serving as an intermediary between man, earth and celestial bodies, as well as between people themselves;

- disease occurs due to the poor distribution of this fluid in the human body, and treatment is reduced to restoring this lost balance;

- Techniques allow this fluid to be channeled, stored and shared with other people;

- "crises" can be provoked in patients and cured.

Mesmer's Aphorisms (1785).

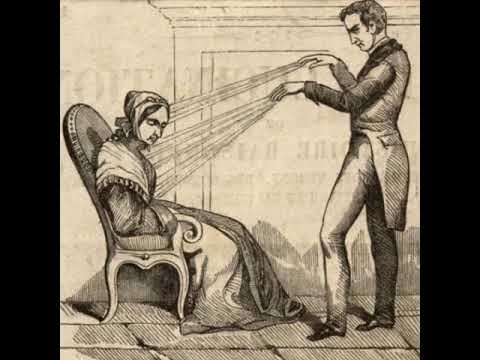

According to Mesmer, animal magnetism is the ability of any person to heal his neighbor with the help of a "natural fluid", the source of which would be a magnetizer and which he would spread through "passages" called "mesmerian passages" all. body. He said that he was able to provoke a crisis with his mere presence or his gestures.

body. He said that he was able to provoke a crisis with his mere presence or his gestures.

Mesmer behaves like an Enlightenment thinker because he rejects any mystical theory, looking for a "rational" explanation. He thinks he found it by applying a principle similar to Newton's universal gravitation. This principle or fluid can exist in several forms, including electricity and animal magnetism.

Mesmer attributes to this liquid poles, discharges, conductors, insulators and accumulators. Thus, he believes that he can artificially provoke crises of the disease to be cured, while at the same time being a method of treatment. It is thus inspired by the methods of the exorcist Gassner: crisis, evidence of demonic possession, is also the first stage of an exorcism on the road to dispossession.

Then he quotes the famous aphorism: "There is only one disease, one remedy, one remedy." The whole history of medicine is just an illusion. No medicine, no therapeutic process has ever cured a patient. Cures the animal magnetism of doctors who use it without noticing it. Animal magnetism is a universal remedy that meets the ideal of the Enlightenment: the dream of "medicine in its perfection".

Cures the animal magnetism of doctors who use it without noticing it. Animal magnetism is a universal remedy that meets the ideal of the Enlightenment: the dream of "medicine in its perfection".

Paris was soon divided between those who considered Mesmer a charlatan forced to flee Vienna and those who believed that he had made a great discovery.

In 1780, Charles Deslon published Observations on Animal Magnetism .

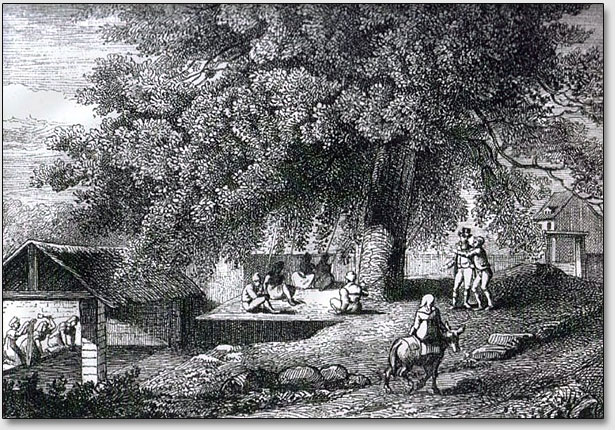

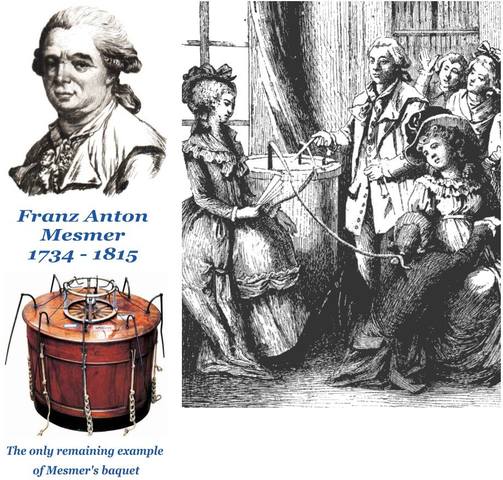

Ladle method (1780)

Reconstruction of the Mesmer bath.

In 1780, with more patients than he could treat individually, Mesmer introduced the collective method of treatment known as the bath. A large tub filled with magnetized water, the edges of which are perforated through which bent iron rods pass at various heights so that they can be applied to the various parts of the body to be treated. In addition to these rods, ropes connect all patients to each other and to the bath.

Patients gathered around Mesmer's bath.

An English doctor, passing through Paris in May 1784, noticed that he could treat up to two hundred patients at the same time. The whole production was designed to amplify magnetic influences: large mirrors and musical sounds emanating from magnetized instruments, including a glass harmonica played by Mesmer himself. For the poor, he offers another collective treatment, but outdoors: magnetized wood.

It is during this collective treatment that the contagious phenomena of "magnetic crises" occur, during which the women of the best Parisian society lose control of themselves, burst into "hysterical" laughter, faint, convulse, etc.

Mesmer is heavily criticized by the medical faculty, but he has powerful clients such as the lawyer Nicolas Bergasse and the banker Guillaume Kornmann.

In May 1781 Mesmer left Paris for Spa (now in Belgium), where he wrote his historical summaries of facts relating to animal magnetism, which he sent to scientific companies around the world. He returned to Paris at the end of 1781. He stayed at Spa for the second time from July to December 1782.

He returned to Paris at the end of 1781. He stayed at Spa for the second time from July to December 1782.

Then he realizes that he has reached a dead end, he is still not recognized by scientific societies, in particular the Academy of Sciences or the Royal Society of Medicine in France. In addition, his partner Charles Deslon took advantage of his absence from Paris to create a personal clientele of animal magnetism, which he sees as an attempt to supplant him.

In March 1783 he founded the Lodge of Harmony, the future Society for Universal Harmony.

Society for Universal Harmony (1784)

Mesmer organizes, with the help of Nicolas Bergasse and Guillaume Kornmann, a subscription for the purchase of "Mesmer's secret". To this end, they created the Society for General Harmony in 1784, the subscribers becoming the owners of the secret, forming a society dedicated to the teaching and dissemination of Mesmer's doctrine.

This society is both a commercial enterprise, a private school and a Masonic lodge. The financial success is enormous: the most illustrious names of Paris and the Court can be found among subscribers such as Noailles, Montesquieu and the Marquis de Lafayette.

The financial success is enormous: the most illustrious names of Paris and the Court can be found among subscribers such as Noailles, Montesquieu and the Marquis de Lafayette.

Armand Marc Jacques de Chastenet de Puysegur and his two brothers will be members of this company.

1784 was the heyday of Mesmer and the beginning of his end. His company made him a considerable fortune, subsidiaries were set up in other cities in France, but this growing excitement caught the attention of the royal family.

An Inquiry into the Practices of Mesmer (1784)

Animal Magnetism Investigation Commission. Objects, magnetized or not, appear to the patient as the opposite of what they are: what the patient "imagines" is at work, not the nature of the object.

In March 1784, at the instigation of Deslons and despite the protests of Mesmer, Louis XVI created two commissions to study the practice of animal magnetism: one from the Academy of Sciences and the Academy of Medicine, and the other from the Royal Society of Medicine.

The members of the commission are among the greatest scientists of the day: astronomer Jean Sylvain Bailly, doctors Joseph-Ignace Guillotin and Jean d'Arcet, chemist Antoine Lavoisier, physicists such as US Ambassador Benjamin Franklin and Jean-Baptiste Le Roy. , botanist Antoine Laurent de Jassi.

These scientists are based on Mesmer's 27 proposals put forward by Charles Deslon, who presents and explains his own practices of animal magnetism. Lavoisier then established an applied model of the experimental method: the question was not whether animal magnetism cured patients or not, but whether Mesmer had indeed discovered the physical existence of a new fluid. It was concluded that no evidence of the existence of a "ferrofluid" was found.

Therapeutic possibilities explored by the Royal Society of Medicine are not denied, but attributed to "imagination" (in the literal sense of the time: suggestion or influence from the image). Jean Sylvain Bailly concludes that "imagination without magnetism produces convulsions. ..magnetism without imagination produces nothing."

..magnetism without imagination produces nothing."

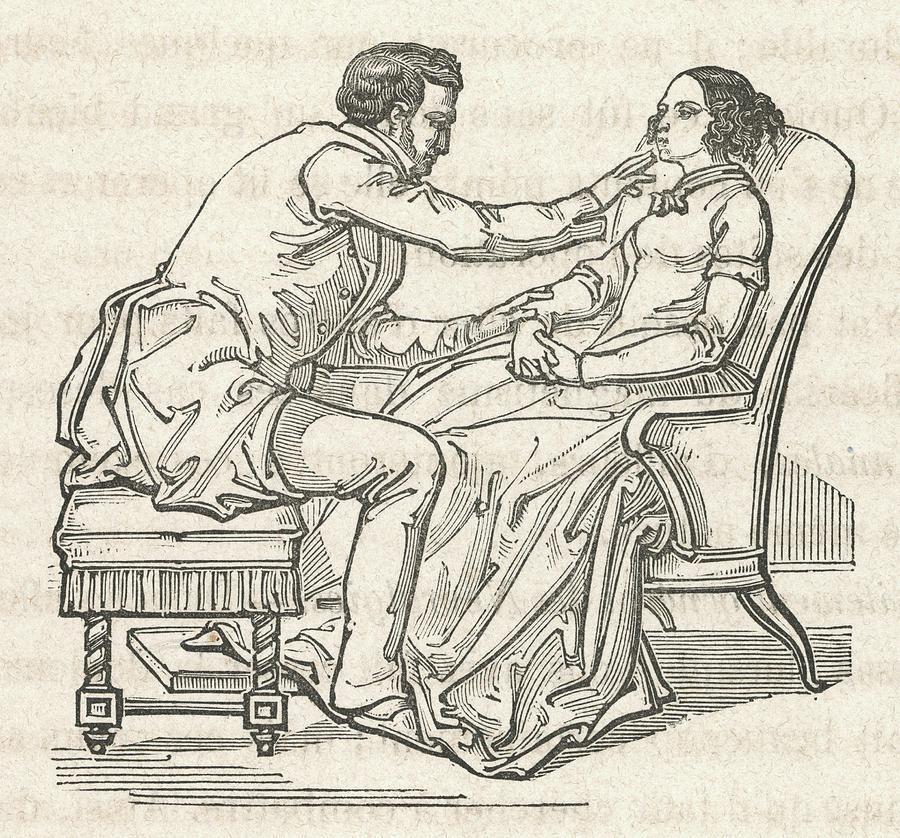

The hypnotist doctor ( hypnotist doctor ) takes advantage of the situation. English lithograph from 1852.

Second secret report sent to the King (published under the First Empire). He warns against the erotic dangers that the male magnetizer manifests towards his magnetized patients: "magnetic treatment can only be dangerous to morality." On the other hand, one of the commissioners, Antoine Laurent de Jussieu, disassociates himself from his colleagues by writing a special report in which he states that "the physical influence of man on man must be recognized" and that this agent was probably "Animal warmth" .

However, since the commission only observed Deslon's work, many argued that the latter was not really familiar with Mesmer's system. The latter was outraged that the commissioners addressed their questions to the "traitor" Deslon, and not to him. However, this circumstance did him good, because when the prosecutor decided to ban animal magnetism, Bergass managed to lift the ban on Mesmer, since, from a legal point of view, Deslon's actions did not concern Mesmer's practice.

The reports of 1784 not only did not harm the development of the magnetic movement, but, on the contrary, gave it publicity. This effect was reinforced by Jassi's controversial opinion and by the fact that in the same year one of Mesmer's most faithful disciples, the Marquis de Puysegur, made new discoveries in a state hitherto unknown to consciousness, which he called. "Magnetic dream".

For the future of mesmerism, see

Crisis of 1784-1785 and departure from France

If academic research does not prevent the development of mesmerism, Mesmer himself knows many failures. In terms of popular fame, he is often ridiculed, subjected to cartoons, popular songs, and satirical plays. On April 16, 1784, he was deeply offended by attending a concert organized at court by the blind harpsichordist Maria Theresa Paradis from Vienna, the very one whom he was supposed to heal. All eyes turned to Mesmer to show his recklessness.

Mesmer, de Puysegur and Deleuze.

More serious for Mesmer are the reviews published by scholars and scholars. An anonymous author publishes Antimagnetism ( 1784), emphasizing the similarities in methods between animal magnetism and exorcism. Dr. Touré published Investigations and Doubts in Animal Magnetism (1784), examining Mesmer's 27 statements one by one to indicate that they had already been formulated by occult doctors of past ages and that Mesmer's theory was far from new. only the renewal of abandoned doctrines. Another physician-physicist Jean-Paul Marat in his Memories of Medical Electricity (Rouen 1783 and Paris 1784) emphasizes that animal magnetism cannot be presented as a physical theory.

Finally, Mesmer's students themselves find his teaching vague and inconsistent and want to formulate it differently. At that time, Mesmer pursued therapeutic goals through individual harmony. Bergass sees more, foreseeing universal harmony and social harmony. Magnetism is no longer a remedy, but a political pretext, a struggle against despotism, conceived as a social therapy. Bergass publishes a new philosophy of the world: Theory of the world and organized beings, following the principles of M. *** (1784).

In addition, Mesmer perceives the discovery of the "magnetic dream" by his student Puysegur as a personal attack that shames him. In August 1784, he was called by the Harmony Society of Lyon to hold a demonstration before Prince Henry of Prussia, brother of Frederick II, where he completely failed.

Mesmer broke with Bergasse, Kornmann and other influential members of the Société de l'harmonie. This split reflects political divisions: Mesmer is committed to apoliticality, moreover, he is more suited to satisfy his immediate interests of greed, but also to the self-centered and intransigent nature of his personality.

Probably at the beginning of 1785 Mesmer left Paris and France. According to Ellenberger, his reaction would have been the same as in 1777 (leaving Vienna): wounded with pride, suffering from depression, he fled.

Last travels (1786-1815)

Little is known about the last part of his life. For the last decade, his followers did not know where he was or if he was still alive. The movement he founded remains under the leadership of Puysegur.

After leaving Paris, he would have lived in England for several years under an assumed name. He then travels through Austria, France, Germany and Switzerland.

revolutionary period

In 1790 he returned to Vienna to touch the legacy of his wife's death. He found his Austrian friends and set up a salon where we sympathetically discussed the French Revolution, including the Constitution of 1791. He returned for a time to Paris, which he left again in 1793 during the Terror. Upon returning to Vienna after the execution of Louis XVI, he was suspected of revolutionary complicity. Imprisoned for two months, he was released on December 4, 1793 years.

He moved to Switzerland and settled in Wagenhausen in the canton of Thurgau. In 1794, his name was involved in a "Jacobin conspiracy" directed against François II (the future François I of Austria, Marie Antoinette's nephew). His Austrian friends had become radically "Viennese Jacobins" during his absence, while Mesmer himself would have been closer to the Club des Feuillants than to the Club des Jacobins.

In 1798, under the leadership of the Directory, he returned to Paris in the hope of recovering some of his property and obtaining a pulpit in a hospital to spread his teachings. He spent three or four years in Paris and Versailles. He then wrote his memoirs in 1799 year. He received financial compensation from the government in the amount of £400,000.

Frauenfeld

He settled in Switzerland, in Frauenfeld (Thurgau). He has lost most of his fortune, but he still has enough to live as a wealthy aristocrat isolated from the world, away from the doctors who rejected him and from his followers who betrayed him.

Lorenz Oken visited him in 1809. At the end of this stay, Oken called the doctors to meet with Mesmer. Johann Christian Reil then invited Mesmer to come and practice in Berlin at an institution recognized by the Prussian authorities. Mesmer, speaking of his advanced age, declines the invitation, but, on the contrary, offers to receive at home any person authorized by Oken. At the request of a commission set up by Chancellor Karl August von Hardenberg, Dr. Christian Wohlfarth - a "mesmerist" and a member of the Prussian Academy - traveled to Frauenfeld, where he arrived in September 1812.

Mesmer's grave in Meersburg, 2006.

Wolfart, a romantic and German patriot, is struck by Mesmer's character, who, like the old German aristocracy, expresses himself exclusively in French. Mesmer bequeathed his manuscripts to Wohlfahrt, who translated and published them in 1814, but only in part, under the title Mesmerimus oder System der Wechselwirkungen, Theorie und Anwendung des thierischen Magnetismus . This latest work is not only about Mesmer's medical ideas, but also about his opinions on issues ranging from education to prisons, passing public holidays and taxes.

Unfortunately, most of the manuscripts left by Wohlfarth have been lost. According to Ellenberger "Wolfart was so careless that in his translation he gave Mesmer the first name Friedrich instead of Franz. »

A year or two before his death, Messmer settled in Meersburg, on the shores of Lake Constance, where he died on March 5, 1815, a few kilometers from his native village of Isnang.

Personality

Music sponsorship

During his Viennese period, Mesmer was a young physician who, having married, lived like a man of the world on a large, magnificent estate, where he distinguished himself as a connoisseur and advocate of the arts.

Artists who frequent his home include the musicians Haydn and Gluck and the Mozart family. Thus, Leopold Mozart introduces his infant son Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, age twelve, to Mesmer. The first performance of Mozart's second opera, Bastien und Bastienne , will take place at the private theater Mesmer le .

Mozart will later make a reference to Mesmer (his bath and his liquid), but ridicule him in his opera Così fan tutte (1790).

Mesmer was also one of the first to play the glass harmonica, a musical instrument perfected by Benjamin Franklin.

Character

Signed by Franz Anton Mesmer.

When Mesmer arrived in Paris, he was 43 years old. He is described as a handsome man, tall and energetic, distinguished person with refined manners. He expresses himself very well in French, despite a strong German accent. He was quickly accepted in French society: communicating at ease with princes and nobles, he knew how to combine charm and authority in order to convince people and receive important services.

His disappointed supporters paint a bitter picture: Mesmer was convinced that he had made an important discovery that the whole world should accept immediately, but he alone should reveal it at his own whim. He demands absolute dedication from his followers, but in return he is not interested in the ideas of others and does not show gratitude. Proud and self-centered, he immediately breaks down, feeling indifference as hostility, and the slightest criticism as persecution.

According to Ellenberger, the fluctuations in his career reflect his psychopathology. In unstable mood and pathological hypersensitivity, he has periods of elation and depression, hypomania and despondency. Toward the end of his life, he is reported to have expressed a delusion, saying that the water in the rivers was magnetized because he, Mesmer, was magnetizing the sun.

Perspectives

Franz Anton Mesmer remains a controversial figure both in his time and among historians. According to the authors, he can be presented first as a charlatan doctor who inspired occultism and spiritualism in XIX th centuries; or as a pioneer of hypnosis and dynamic psychotherapy; or as an influential physician of the Enlightenment, representative of the conflicts and controversies of his day.

Quack Doctor

The Age of Enlightenment has also been called the "Golden Age of Quackery" by medical historians. From this point of view, the social demand for individual health is growing, but institutional control over the practice of health remains insufficient. The practice of health care is a growing sector of the free market economy. In this context, "technological" therapeutic inventions appear, including those based on magnetism and electricity, such as those of the American doctor Elisha Perkins (1741-1799) or the Scottish doctor James Graham (sexologist) (fr.) (1745-1794).

Mesmer would be the best known exponent of these new methods, which are also presented in a theatrical way, arousing the enthusiasm of the public, which corresponds to the term of quackery from XVI E century. Since his time, and during two centuries of controversy, Mesmer has often been accused of being a charlatan and an upstart adventurer. In support of this thesis: evidence of his growing greed and even dishonesty, his tub of collective conversion, pictorial anecdotes or delusional comments.

Hence the popularity of spiritism and mediums in the second half of the XIX - centuries will be in the continuity of the spread of hypnosis.

For others, such as Rauski, "the concept of quackery should not be used, because it is not an accurate historical category but an ethical value judgment clothed in dubious objectivity." Doctors in power would be constantly accused of marginalizing or excluding competitors or adversaries. For example, Jean-Paul Marat, who blames both Mesmer and Ledru, also owns a "medical electricity store".

It would then be appropriate to distinguish in Mesmer's life and work between a "clear project" and "irrational delirium."

Innovative doctor

Generally speaking, most historians believe that the Mesmer case cannot be reduced to a case of quackery. According to Roy Porter (in), it is also "one of the figures of the transition from magic to modern psychotherapy": Mesmer would have been a pioneer of hypnosis.

In the words of Henri Ellenberger, "we can trace modern dynamic psychiatry back to Mesmer's animal magnetism, and that in this respect descendants have shown themselves exceptionally ungrateful towards him." If mesmerism has been discredited, Mesmer himself opens the way where Jean-Martin Charcot, Pierre Janet and Sigmund Freud can be found.

Stefan Zweig in his essay "Healing by the Spirit" (1931) even makes of Mesmer a Christopher Columbus: like the one who believed he had found India by discovering America, Mesmer believed that he had discovered the magnetic fluid where the concept of the unconscious existed .

Franklin Rawsky discusses Mesmer's observations or practices that foreshadow or anticipate psychoanalytic concepts such as the role of the patient and the phenomenon of transference. Likewise, the collective treatment of the bathroom, in which Mesmer poses as the leader of the group, would be the order of group therapy.

Doctor of Enlightenment

Animal magnetism and the followers of mesmerism, divided into divergent currents, have been studied more than Mesmer himself.

Magnetizer to induce hypnotic trance. Engraving from 1794.

Mesmer is not a marginal, but a doctor imbued with the new principles of Enlightenment medicine. He was a student of Gérard van Swinten (1700–1772), who presented the University of Vienna with the ideas of his teacher Hermann Burrhave (1668–1738). Medicine is the science of observing the living body, which is practiced in bed.

His confrontation with the sorcerer Gassner, who is the source of his career as a hypnotist, represents the medicalization of magical and mystical currents still very present in from the 18th - th century. In states of "possession", convulsive suffering, "nervous or vaporous" illnesses, Mesmer intends to transfer the miraculous power of the sorcerer or exorcist to the healing power of the magnetizer.

Mesmer is a supporter of Reason and enlightened despotism. He rejects both the old Galenism and all sorts of superstitions. A fan of Newton and Rousseau, he believes in nature's cure project, which is being developed for the happiness of mankind. According to Rauska, by creating a "society of universal harmony", Mesmer inspires his followers not only will to heal, but also desire to heal , which explains his success.

Mesmer is neither a theorist nor a great reader, and he has hardly explained his doctrine. But his ideas seem to be those of sensualistic materialism inspired by Helvetius, baron d'Holbach. As a representative of the Aufklarung , Mesmer directly inspired Lorenz Oken (1779–1851), the leader of the German natural philosophy .

Works

- On the influence of the planets on the human organism , 1766

- Memoirs of the Discovery of Animal Magnetism , 1779, digital edition available at wiki source, in version ePub (ISBN 9782362740015) or Kindle ( ISBN 9782362740039 Editions1 by Mesmeria7)

- Dissertation on the discovery of animal magnetism , Paris, Allia , , 96 pp.

( ISBN 2844852262) (ISBN 9782362740114) in Mesmeria Editions.

Offspring

His fame in the English-speaking world will be such that the verb "hypnotize" ( literally and figuratively), as they say in English, not only hypnotizes , but hypnotizes ; the verbal form mesmerizing (literally mesmerizing) is also used as an adjective meaning fascinating (to refer to a show, movie, book, etc.).

Honore de Balzac was a follower of mesmerism and animal magnetism. He expands on this theme in detail in his novel Ursula Miruet where we see a skeptical Dr. Minore being persuaded to treat his ward: Ursula.

In 1887 Guy de Maupassant mentions Mesmer's name and describes hypnotic phenomena in his second version of Horl.

In 1936, Dr. Jean Vinchon, together with the publisher Amédée Legrand, published a study entitled "The Mystery of the Mesmer and son" .

In 1994 Roger Spottiswoode directed Mesmer about the life of a doctor (especially hypnosis) with Alan Rickman as Franz Anton Mesmer.

In 2017, Barbara Albert made the film Mademoiselle Paradis, about Mesmer's conversion to Maria Theresa Paradis.

Mesmer is mentioned in Kiyoshi Kurosawa's Cure , in which a former psychology student who has gone insane has disturbing hypnotic powers.

Also quoted by Abraham Van Helsing in Francis Ford Coppola's Dracula .

Brian O'Doherty's novel The Strange Case of Miss P. (1992) is dedicated to the treatment of the blind musician Maria Theresa von Paradis.

Alexandre Dumas describes a treatment session in "The Queen's Necklace" .

Michel Halberstadt writes the incredible story of Mademoiselle Paradis (2008 edition, Albin Michel) about the cure and the "romance between Paradis and Mesmer". 9 A b c d e and f Ellenberger 1974, pp. 57-58.

Biography . Studied theology and medicine. AT further studied the practical application of magnetism. Research . In 1776 he came to the conclusion that magnetotherapy was beneficial acts on the patient not by the magnet itself, but by a mysterious force (fluid), coming from the magnetizer. According to him, the planets act on people by means of certain magnetic forces that can be accumulated and transmitted for the purpose elimination of pain. Methods . Developed a treatment that was named by him "bake" (from French baque - chan). This psychotherapeutic technique was based on metaphor of "animal magnetism" ( Rudestam K. Group psychotherapy M.: Progress, 1990 ). It lies in the fact that several patients are located around a wooden vat of water with iron rods in the lid. Sick they take these rods with their hands or apply them to the diseased organ. Magnetizer must touch the vat and transfer his energy through it so that its healing the effect was exerted on all patients at the same time.

Biography . Studied theology and medicine. AT further studied the practical application of magnetism. Research . In 1776 he came to the conclusion that magnetotherapy was beneficial acts on the patient not by the magnet itself, but by a mysterious force (fluid), coming from the magnetizer. According to him, the planets act on people by means of certain magnetic forces that can be accumulated and transmitted for the purpose elimination of pain. Methods . Developed a treatment that was named by him "bake" (from French baque - chan). This psychotherapeutic technique was based on metaphor of "animal magnetism" ( Rudestam K. Group psychotherapy M.: Progress, 1990 ). It lies in the fact that several patients are located around a wooden vat of water with iron rods in the lid. Sick they take these rods with their hands or apply them to the diseased organ. Magnetizer must touch the vat and transfer his energy through it so that its healing the effect was exerted on all patients at the same time. At the same time it was formulated the position that in order to achieve the greatest success of treatment it is necessary to combine such factors as the good health of the doctor; individual predisposition to bioenergy interactions; choosing a quiet place for the session and the achievement of good morale; session duration should gradually lengthen from 10 to 20 minutes. The effectiveness of this method was due primarily to the fact that patients were immersed in a state of trance, which Mesmer associated with somnambulism. In addition, healing was achieved in due to the fact that patients began to believe in their own strength, which increased due to assimilation by them of "animal magnetism" and became sufficient to cope with disease. Thus, Mesmer's experiments were among the first in which In large material, a positive effect of suggestion was recorded. Historic context . Mesmer's teaching had a significant impact on philosophy romanticism and on the natural science study of hypnotism and suggestion.

At the same time it was formulated the position that in order to achieve the greatest success of treatment it is necessary to combine such factors as the good health of the doctor; individual predisposition to bioenergy interactions; choosing a quiet place for the session and the achievement of good morale; session duration should gradually lengthen from 10 to 20 minutes. The effectiveness of this method was due primarily to the fact that patients were immersed in a state of trance, which Mesmer associated with somnambulism. In addition, healing was achieved in due to the fact that patients began to believe in their own strength, which increased due to assimilation by them of "animal magnetism" and became sufficient to cope with disease. Thus, Mesmer's experiments were among the first in which In large material, a positive effect of suggestion was recorded. Historic context . Mesmer's teaching had a significant impact on philosophy romanticism and on the natural science study of hypnotism and suggestion.

/pic3667676.jpg)