Discipline for teenagers

Discipline strategies for teenagers | Raising Children Network

Discipline: pre-teens and teenagers

Discipline isn’t about punishment. It’s about guiding children towards appropriate ways to behave. For pre-teens and teenagers, discipline is about agreeing on and setting appropriate limits and helping them behave within those limits.

When your child was younger, you probably used a range of discipline strategies to teach them the basics of good behaviour. Now your child is moving into the teenage years, you can use limits and boundaries to help them learn independence, take responsibility for their behaviour and its outcomes, and solve problems.

Your child needs these skills to become a young adult with their own standards for appropriate behaviour and respect for others. An important part of this is learning to stick to some clear rules, agreed on in advance, and with agreed consequences.

Teenagers don’t yet have all the skills they need to make all their own decisions, so your agreed limits for behaviour help your child make good choices about how to behave.

Teenage discipline is most effective when you:

- communicate openly with your child – this allows you to talk about how the limits and rules are working, and guide your child towards good choices

- build and maintain a warm and loving family environment – this helps your child feel safe to make mistakes as they learn to manage their own behaviour.

Negotiation is a key part of communicating with pre-teens and teenagers and can help avoid problems. Negotiating with your child shows that you respect their ideas. It also helps your child learn to compromise as part of decision-making.

Agreeing on clear limits with pre-teens and teenagers

Clear limits and expectations can discourage problem behaviour from happening in the first place. Limits also help your child develop positive social behaviour, including showing concern for others.

Here are some tips for setting clear limits:

- Involve your child in working out limits and rules.

When your child feels that you listen to them and they can contribute, they’ll be more likely to see you as fair and stick to the agreed rules.

When your child feels that you listen to them and they can contribute, they’ll be more likely to see you as fair and stick to the agreed rules. - Be clear about the behaviour you expect. It can help to check that your child has understood your expectations. For example, you could say, ‘Please come home after the movie’. But it might be clearer to say, ‘Come straight home after the movie ends and don’t go anywhere else’.

- Discuss responsibilities with your child. For example, ‘I’m responsible for providing for you. You have responsibilities too, like tidying your room’.

- Agree in advance with your child on what the consequences will be if they don’t stick to the rules you’ve agreed on.

- Use descriptive praise when your child follows through on agreed limits. For example, ‘Thanks for coming straight home from the movie’.

- Be willing to discuss and adjust rules as your child shows responsibility or gets older – for example, by extending your child’s curfew.

To check whether your family rules are realistic and reasonable, you could talk with other parents who have children of the same age. Many schools can also help with guidance.

Using consequences as part of teenage discipline

Sometimes your child might behave in ways that test your limits or break the rules you’ve agreed on. One way to deal with this is by using consequences.

Here’s how.

Make the consequence fit

If you can make the consequence fit the misbehaviour, it gets your child to think about the issue. It can also feel fairer to your child. For example, if your child is home later than the agreed time, a fitting consequence might be having to come home early next time.

Withdraw cooperation

This strategy aims to help your child understand your perspective and learn that they need to give and take. It also helps your child understand that every action has a consequence. By doing the right thing, your child can get a positive consequence. But doing the wrong thing means they get a negative consequence.

But doing the wrong thing means they get a negative consequence.

For example, if your child wants you to wash a special item of clothing, you could say you’ll do this if they put all their dirty clothes in the laundry basket. Try to avoid making this into a bribe.

Let your child know beforehand that you might withdraw your cooperation as a consequence for misbehaviour. For example, ‘If you want me to iron your shirt for tonight, you need to speak respectfully to me’. Saying that you’re prepared to follow through with a consequence is sometimes enough to influence behaviour.

Withdraw privileges

This consequence should be used sparingly. If you use it too much, it won’t work as well.

The idea is to remove something that you know your child enjoys – for example, visits to a friend’s house, access to technology, or access to activities. You need to let your child know in advance that this is what you plan to do, so that they can weigh up whether losing the privilege is worth it.

You don’t need to withdraw privileges for a long time for this consequence to be effective. Aim for a short withdrawal that occurs within the few days following the misbehaviour.

Reinforcing consequences

Whatever consequence you choose, these strategies might help to reinforce it.

Communication

It’s important to explain calmly and clearly what the problem is to your child. Tell your child how they haven’t stuck to the rules you agreed on, and let them know that you’ll be applying the agreed consequence.

Self-reflection

The idea is to encourage your child to think about their behaviour and how it could be different in the future.

You can talk with your child about the agreement you had, and what they think should happen as a consequence of breaking it. Often teenagers will be much harsher than their parents. This allows you to settle on future consequences that you both see as fair.

It’s best to balance rules and consequences with warmth and positivity. Try to praise your child or give positive attention more often than you correct or criticise.

Try to praise your child or give positive attention more often than you correct or criticise.

Why teenagers test the limits

Teenagers have the job of developing into independent adults. One way they do this is by testing boundaries and seeing how other people react to their behaviour. This teaches them what the social expectations are. As they get feedback, they learn what’s expected.

On top of this the teenage brain goes through massive growth and development during adolescence. As a result teenagers try new things but don’t always make good decisions. They’re more influenced by peers. And they feel things more intensely than you do.

At the same time, teenagers are getting better at seeing the big picture and reasoning. This means they question their world more and use creative ways to solve problems.

For all these reasons, teenage behaviour might sometimes seem hard to manage. But you can work on behaviour with your child and guide them away from tricky situations.

How to Discipline a Teenager Who Doesn't Care About Consequences

Many parents discipline their teens by taking away their cell phone privileges, video games, or screen time, or giving them extra chores. Despite having once worked, these strategies often don’t work after a while. So how to discipline a teenager who doesn’t care about consequences?

Consequences and Behaviorism

Using consequences to discipline is an example of behavioral management, which is based on behaviorism1. It is a type of discipline strategy commonly prescribed by teachers or behaviorists.

The type of consequences employed by parents is usually negative although both positive and negative consequences can be used.

Behaviorism is a theory or doctrine that explains how the environment influences an animal’s or person’s behavior. It asserts that people and animals are not free to act as they please, but instead are controlled by external forces.

Behaviorists believe that behavior can be changed as the environment changes through a process called operant conditioning. Using operant conditioning, a person can form an association between the environment and the behavior. One learns how to behave in a given environment through associative learning.

Using operant conditioning, a person can form an association between the environment and the behavior. One learns how to behave in a given environment through associative learning.

In this view, it is the environment that determines a child’s behavior. Negative behaviors are the result of bad training. If we apply the right consequences, we will get appropriate behaviors.

The decline of Behaviorism

Behaviorism gained popularity in the 1960s. It was the first time psychology was considered a science because one could repeat the results reliably with the same inputs.

The power of conditioned learning was demonstrated through numerous experiments using animals such as pigeons or rats2.

What’s the problem?

The problem is people are not lab rats.

Humans are a lot more sophisticated than lab animals. To assume that everything a person does could be explained or influenced by the environment is incorrect, and that has been clearly proven in studies3–5.

While behaviorism declines in its use and influence within psychology, this shift hasn’t spread among parents. A lot of parents are still using consequences to discipline their children because it really seems to work… but only the first few times they use it.

Why is behavior management still used in classrooms

Then why do teachers still learn behavior management in their training if behaviorism is so bad6?

It is common for teachers to use behavior management in the classroom since it is an effective way to control a group’s behavior. In the short term, behavioral management techniques can often affect a crowd’s behavior reliably.

This is why when most parents first start using consequences, they see positive results. But the short-term results usually don’t last.

Because a child is not a pigeon.

A child’s brain has a mind and a mental process, which behaviorists conveniently disregard when promoting behaviorism.

Why are punitive consequences especially harmful for teenagers

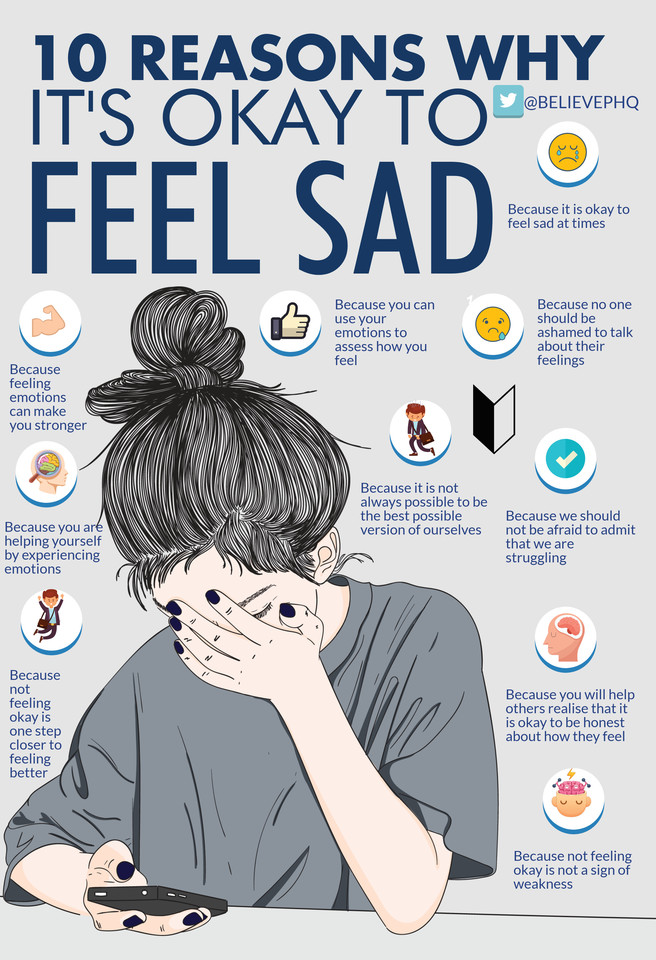

Fighting constantly is bad for anyone’s mental health, but it’s particularly harmful to teenagers since their brains are more vulnerable during adolescence.

Conflicts between parents and children are linked to adolescents’ aggression7, anger management issues, anxiety, and depression8.

Adolescents who engage in high levels of conflicts with their parents also tend to display mood, emotional, and behavior problems9.

Conflicts over mundane domestic issues are one of the best predictors of adolescent maladjustment10. They are also linked to several psychiatric disorders, such as conduct disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder 11.

How to discipline a teenager who doesn’t care about consequences

Don’t use consequences to discipline

Stop treating your child as a lab animal! They have feelings and thoughts like all people.

Imagine, if someone punishes you on a daily basis to bend you to their will, do you think you will gladly accept and comply all the time?

You may, at the beginning. But at some point, you probably will start fighting back. You may argue over the rules or punishment. You may also get angry when that doesn’t work. That’s normal. You are seeking justice and protection for yourself. Temper tantrums appear because you are frustrated.

You may argue over the rules or punishment. You may also get angry when that doesn’t work. That’s normal. You are seeking justice and protection for yourself. Temper tantrums appear because you are frustrated.

But when our children have arguments with us and get upset, we call them “a defiant teenager.”

So, when we are punishing teens and not allowing them to fight back, we are not only treating our kids as lab animals but also as second-class citizens who have no right to speak up or defend themselves.

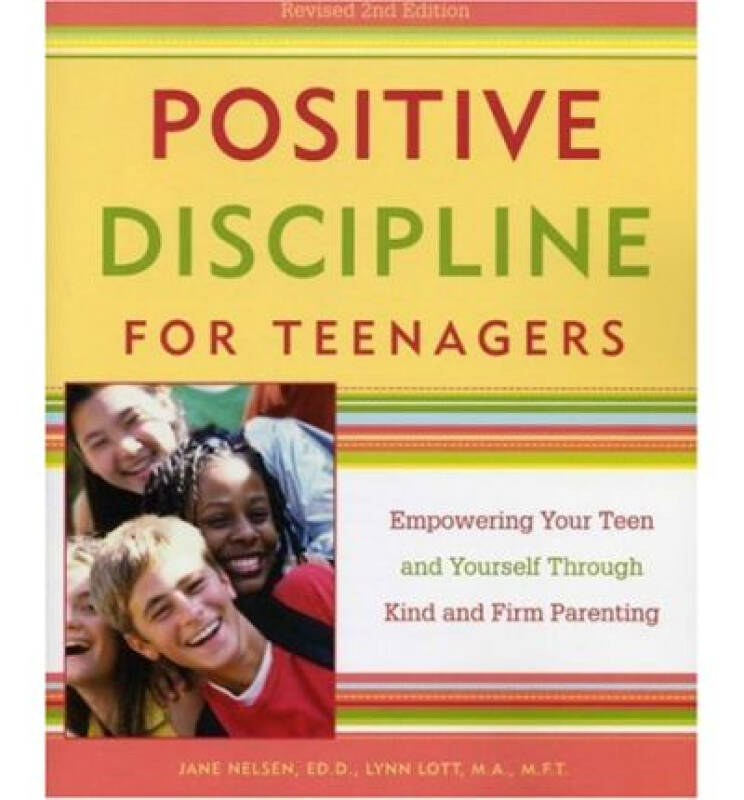

Teach them how to think

Discipline means to teach, not to punish.

The purpose of discipline is not to make kids suffer, but to teach them positive behavior.

A better way to discipline is to teach them how to think critically.

Critical thinking skills are crucial to the development of teenagers.

Parents have been telling their children what to do ever since they were babies. The habit is ingrained in us.

But teenagers are no longer babies. These young adults are developing their independence. We cannot just tell them what to do. We must also explain why they should do it.

These young adults are developing their independence. We cannot just tell them what to do. We must also explain why they should do it.

This is how teenagers learn to make good decisions.

Teenagers don’t suddenly develop sound judgment the moment they turn 18. It is a skill that takes time and practice to develop.

When you set appropriate limits, give them reasons. Explain the pros and cons of every decision, so that they have a process to follow when they need to make their own decisions.

When appropriate, use natural consequences

Natural consequences are the most effective consequences when the issue is not health or safety-related.

Parents often fret about their teens’ unfinished school work or failing grades, but they don’t realize that they cannot hold their teens’ hands forever. Unless you plan to punish or bribe your teen through college, which will most likely not work once they turn 18, let them fail now. It’s better to fail now than to wait until they turn 18.

You cannot care for a teen their entire life if they don’t care about their own future. They need to face the logical consequences of their actions sooner rather than later.

Focus on issues, not personal blames

Parents tend to have more frequent and more intense conflicts when they believe their teenager’s bad behavior is a result of their personality12. They are upset because they think that their children are misbehaving with malicious intentions to hurt them. Frustrated parents tend to have distorted beliefs such as perfectionism, obedience, and ruination more than non-distressed parents.

So when there are conflicts or incidents that require discipline, focus on the issue, not personal attributions that will do nothing but make everyone angrier.

Repair your relationship

If you have been using punishments for teenagers to the point that your child no longer cares, then it is very likely that your relationship has been damaged.

A strained relationship cannot help your teen behave. Listening and learning are more likely to happen when your child feels connected to you. Start now if you want to save this relationship.

Listening and learning are more likely to happen when your child feels connected to you. Start now if you want to save this relationship.

The key to strengthening a relationship is not just spending more time together.

Quality time matters more.

Relationships between parents and children are special, but they’re not that different from those between friends, neighbors, coworkers, or spouses.

Kids are people too.

To build a good relationship, You need to care about them, treat them with kindness and respect, help when they need it, and give them support when they’re discouraged.

The same applies to building any kind of relationship.

The only difference between a parent-child relationship and one with an adult is that we must also protect them.

One of the best ways to teach teens appropriate behavior is to re-establish a close relationship with them.

Studies find that adolescents who have a supportive relationship with parents are less likely to engage in delinquent behavior due to peer pressure13.

A positive relationship and a pleasant family life can go a long way in teaching teens good behavior.

Teach them how to disagree respectfully

Some parents believe that any disagreement from their children is backtalk. However, disagreeing with someone is not the same as talking back. It is possible to disagree with someone respectfully, a crucial skill that many children don’t learn at home.

If you want your child to become a leader, not just someone who follows orders from others, you must give them the confidence and skills to discuss disagreement respectfully.

So the next time you want to discipline your teen, take some deep breaths. Avoid power struggle in the heat of the moment. Teach them calmly how to disagree respectfully. Focus on the issue, not personal attributes. Teach them a process to critically think through the problem to make better choices. Most importantly, let them practice making decisions and doing the right thing.

Motivate your teenager intrinsically

If the discipline issue involves a lack of motivation, motivate them intrinsically to inspire behavior change.

Intrinsic motivation means your teen will want to do an activity because they enjoy it, not because they will be rewarded or punished.

Also See: Parenting Teens

Need Help Motivating Kids?

If you are looking for additional tips and an actual step-by-step plan to motivate your teenager, this online course How To Motivate Kids is a great place to start.

It gives you the steps you need to identify motivation issues in your child and the strategy to help your child build self-motivation and become passionate about learning.

Once you learn this science-based strategy, motivating your child becomes easy and stress-free.

References

-

1.

Watson JB, Kimble GA. Behaviorism. Routledge; 2017. doi:10.4324/9781351314329

-

2.

Pineño O. ArduiPod Box: A low-cost and open-source Skinner box using an iPod Touch and an Arduino microcontroller.

Behav Res. Published online June 28, 2013:196-205. doi:10.3758/s13428-013-0367-5

Behav Res. Published online June 28, 2013:196-205. doi:10.3758/s13428-013-0367-5 -

3.

Mahoney MJ. Scientific psychology and radical behaviorism: Important distinctions based in scientism and objectivism. The restoration of dialogue: Readings in the philosophy of clinical psychology. Published online 1992:115-124. doi:10.1037/10112-014

-

4.

Mandler G. Origins of the cognitive (r)evolution. J Hist Behav Sci. Published online 2002:339-353. doi:10.1002/jhbs.10066

-

5.

Moore J. Behaviorism. Psychol Rec. Published online July 2011:449-463. doi:10.1007/bf03395771

-

6.

Kellam SG, Brown CH, Poduska JM, et al. Effects of a universal classroom behavior management program in first and second grades on young adult behavioral, psychiatric, and social outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. Published online June 2008:S5-S28. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.004

-

7.

Branje SJT, van Doorn M, van der Valk I, Meeus W. Parent–adolescent conflicts, conflict resolution types, and adolescent adjustment. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. Published online March 2009:195-204. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2008.12.004

-

8.

Forehand R, Brody G, Slotkin J, Fauber R, McCombs A, Long N. Young adolescent and maternal depression: Assessment, interrelations, and family predictors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. Published online 1988:422-426. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.56.3.422

-

9.

Slater EJ, Haber JD. Adolescent adjustment following divorce as a function of familial conflict. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. Published online 1984:920-921. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.52.5.920

-

10.

Barber JG, Delfabbro P. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. Published online 2000:275-288. doi:10.1023/a:1007546023135

-

11.

Marmorstein NR, Iacono WG.

Major depression and conduct disorder in youth: associations with parental psychopathology and parent-child conflict. J Child Psychol & Psychiat. Published online February 2004:377-386. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00228.x

Major depression and conduct disorder in youth: associations with parental psychopathology and parent-child conflict. J Child Psychol & Psychiat. Published online February 2004:377-386. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00228.x -

12.

Grace NC, Kelley ML, McCain AP. Attribution processes in mother-adolescent conflict. J Abnorm Child Psychol. Published online April 1993:199-211. doi:10.1007/bf00911316

-

13.

de Kemp RAT, Scholte RHJ, Overbeek G, Engels RCME. Early Adolescent Delinquency. Criminal Justice and Behavior. Published online August 2006:488-510. doi:10.1177/0093854806286208

Teenager and discipline. - All Brains

A teenager does not go to school, does not do his homework, is late, wakes up, does not sleep at night, sits at the computer until the morning ... What can be done about this and can something be changed? This issue is of particular concern to parents of teenagers. They try different methods of influence, appeal to conscience, punish, encourage, persuade, despair that the situation is getting out of control, yesterday, a cute and obedient child stops obeying, becomes uncontrollable, teachers at school complain that the teenager violates discipline.

So what is discipline and is it equal to obedience?

Let's look in the dictionary.

Discipline - restraint, strictness, as well as the rules of behavior of the individual, corresponding to the norms accepted in society or the requirements of the rules of the order. Strict and exact implementation of the rules adopted by a person for implementation.

Traditionally, discipline is maintained with the help of the "carrot and stick" - for compliance, they are encouraged, for violations, they are punished. Everyone has their own methods of reward and punishment, but in many ways they are similar: for violation, they lose something pleasant, interesting, and for compliance they promise something that the child really wants. Sometimes it works, but more often it is ineffective. The reason is just in the teenager himself and in our previous experience of communicating with him. The rules adopted in the family are born together with the family, not suddenly. From birth, a child is brought up with this notorious “Carrot and stick” method, remember, “If you don’t eat soup, then”, “If you don’t do your homework, then . ..”, i.e. there is no positive reinforcement, we do not see and do not encourage the good that is in the child, so the teenager gets used to punishment. Let's remember what is the main task facing a teenager? This is separation. There comes a time when the child begins to argue whether he is being treated fairly, whether what his parents think is so important, he does not take anything for granted, is ready to give up what will benefit him. He forms his own criteria of what is acceptable and what is not necessary for self-discipline, and they do not always coincide with those accepted in society. What is more important for us, that he should follow them, not always fair, remember history, or form his own, according to his convictions? It is difficult for parents to accept that our and his rules do not match, but the world is changing, so it is important to figure out and understand whether his rules will help or hinder a teenager in life.

..”, i.e. there is no positive reinforcement, we do not see and do not encourage the good that is in the child, so the teenager gets used to punishment. Let's remember what is the main task facing a teenager? This is separation. There comes a time when the child begins to argue whether he is being treated fairly, whether what his parents think is so important, he does not take anything for granted, is ready to give up what will benefit him. He forms his own criteria of what is acceptable and what is not necessary for self-discipline, and they do not always coincide with those accepted in society. What is more important for us, that he should follow them, not always fair, remember history, or form his own, according to his convictions? It is difficult for parents to accept that our and his rules do not match, but the world is changing, so it is important to figure out and understand whether his rules will help or hinder a teenager in life.

It is difficult to remain calm with a teenager when the situation repeats itself from day to day and gets out of control. At the same time, it is desirable to answer the following questions as accurately as possible, without labeling, avoiding the words “always, usually”:

At the same time, it is desirable to answer the following questions as accurately as possible, without labeling, avoiding the words “always, usually”:

— What exactly does a teenager do?

— When does he usually do this?

How often?

For example, the son did not go to school on Tuesday. On this day, he has physics. It happens every Tuesday.

Try to describe the event in detail and impartially, this will help to understand what is actually happening in the life of a teenager. It is possible that the child has a conflict with the physics teacher, so he tries to avoid meeting him.

There may be several reasons for what happens to a teenager:

- Demand for attention and comfort. If a teenager does not receive the attention necessary for normal development, then he finds his own way of protest.

- A teenager really needs his parents, their attention, if he is not enough, then he tries to get it anywhere. Because he is used to punishment, then he begins to do something out of the ordinary in order to attract attention to himself in this way.

And here he is - in the spotlight, albeit in this way! Both the teenager and the parents are to blame for the violation of contact. It is important to understand what I, a parent, am doing wrong, why are our relationships and our contact broken? Am I contributing to the fact that we are moving away so much? Do I see his needs? What can I do?

And here he is - in the spotlight, albeit in this way! Both the teenager and the parents are to blame for the violation of contact. It is important to understand what I, a parent, am doing wrong, why are our relationships and our contact broken? Am I contributing to the fact that we are moving away so much? Do I see his needs? What can I do? - Struggle for self-assertion against parental guardianship or authority. For a teenager, it is important not that his decision is correct, but that it is his decision!

This kind of protest occurs when we severely restrict a teenager. Here it is important to understand that do not we require the implementation of family rules just because they exist? Rules are good, they are safety, they are for everyone to respect each other's boundaries, so that everyone is comfortable. But this is not a dogma. If there are rules in the family that are unacceptable for a teenager, does he need to follow them? - Desire to take revenge, children are often offended by their parents.

Revenge for the pain they experienced. Parents do not even notice the small grievances inflicted on the child. When they accumulate, they cause pain. - Assertion of one's insolvency or inferiority, loss of faith in one's own strengths and significance.

A protest arises when the interests and desires of adolescents are not taken into account, when their opinion is not important. - Decreased self-esteem of a teenager. The bitter experience of failures and criticism in his address has been accumulated, he generally loses self-confidence, a syndrome of learned helplessness arises. Comes to the conclusion: “There is nothing to try”, warns his failure. External behavior shows "I'm bad", "I don't care"

This happens when we do not believe in the strength of the child, in his abilities, we do not believe that he will succeed.

Teenagers are a closed people, they won't tell you what is happening to them. But by listening to their feelings, parents can understand what is happening with their child.

If I feel irritated now, then most likely my child needs attention. But can I give it now if I don't have the strength, the time? Therefore, it is important to understand what good I could give myself, take care of myself. When we are full, when we have resources, then we begin to see another person and we can give him attention.

If parents become angry, the child fights for rights and freedom. He does not have enough space to decide something himself. It is important to stop and think why I cannot give him this freedom, what does it mean for me personally if he gets more freedom? How will this affect my life, will it really change my life? If it really changes your life, tell your teenager honestly about it, give him the right to choose.

If you are hurt and offended, then most likely the teenager wants you to feel how hurt he is. Tell him that you are now hurt and offended, and you understand how much it hurts him now. Not always the cause of pain is you, sometimes it is society. A teenager cannot bear this pain, he gives it to his parents. Need support.

A teenager cannot bear this pain, he gives it to his parents. Need support.

If the parents feel hopeless and desperate, then most likely the child is also experiencing his failure and has come to terms with it. This is a heavy feeling, it is easier to go into a computer game, into a dream. It is necessary to find the strengths of a teenager, but not just to find, but to believe in them. It has to be very specific things that he does well or he won't believe you.

By applying a system of rewards and punishments, success can be achieved fairly quickly, but for how long? At what cost? Will it help our children in the future?

Almost all parents would like their children to have such a quality as self-discipline, but it does not appear immediately. The child goes through certain stages of the formation of moral norms.

At first, he follows the rules for selfish reasons, to avoid punishment or to get reward. Having grown older, the approval of significant people, the fear of condemnation, a sense of order becomes important for him. As he grows up, in adolescence, he understands the relativity of the rules, requires an explanation of their usefulness and validity, and fulfills them if there is an agreement. In youth, their own internal system of principles is formed.

As he grows up, in adolescence, he understands the relativity of the rules, requires an explanation of their usefulness and validity, and fulfills them if there is an agreement. In youth, their own internal system of principles is formed.

Parents form family rules. Now that your child is still a teenager, it is important to understand if all your rules would be useful to him if he was your age? Which ones could be ignored? And how would your life change if you didn't follow them too? Be honest with yourself when answering these questions, and maybe then it will be easier for you to live and communicate with your children?

Veronika Petrova

Rules and punishments: how to discipline teenagers

Respect their opinion, value trust, discuss with them sanctions for breaking family rules

Sometimes teenagers behave as if their main goal is to break all restrictions and test adults for strength. In such situations, threats of punishment usually do not work, it is important to explain to them the consequences of their behavior. Maintaining discipline is primarily about making and following rules together, encouraging desirable behavior, and maintaining family trust.

Maintaining discipline is primarily about making and following rules together, encouraging desirable behavior, and maintaining family trust.

Rules against penalties

Discipline does not always involve punishment, it is more about encouraging children to behave in ways that we consider reasonable and useful for themselves. In the case of adolescents, the development of rules and restrictions and help in following them play a key role in this.

With younger children, such educational measures as, for example, an outright ban work quite well. To teach a child the basics of good behavior, it is not always necessary to explain in detail the reasons for this or that “no” - parental authority is enough.

When a child becomes a teenager, he begins to challenge this authority - this is part of growing up. Parents now need to use reasoned rules and limits to help their teen gain independence, solve problems, and learn to take responsibility for their own behavior and outcomes.

These should be clear, pre-agreed rules with clear implications. For example, such: computer games only after homework is done; if the child is visiting or walking, he calls his parents every two hours; come home no later than 10 pm. Discuss not only the rules themselves, but also the sanctions for violating them, such as forfeiting some pocket money: he must know in advance what he is risking.

A teenager is more likely to listen to you if you communicate openly with him, explain how rules work and why rules are necessary, and encourage the right choice in a given situation. And a warm and loving environment in the family will help the child feel safe, even when he made a mistake or violated the prohibition.

Let him be sure that his parents love him for who he is, and not for his actions. In such an environment, children learn to control their behavior faster and more easily agree with parental rules.

Another key part of communication with a teenager is dialogue and negotiation. The desire to discuss disagreements and come to a common decision makes him understand that his parents respect his ideas and the right to independence. In addition, working together on problems teaches you how to compromise and helps you understand the need for it in the decision-making process.

The desire to discuss disagreements and come to a common decision makes him understand that his parents respect his ideas and the right to independence. In addition, working together on problems teaches you how to compromise and helps you understand the need for it in the decision-making process.

Rules should be clear and understandable

Restrictions and rules that an adolescent can understand reduce the likelihood of problem behavior and teach them to care about other people and their feelings. Here's how to make the rules for a teenager clearer.

- Involve your child in developing the rules. If he feels that he is being heard, he can contribute and offer his own options for restrictions and sanctions for their violation. This means that they are more likely to consider the rules fair and adhere to them.

- Be clear about what you want your child to do and make sure he understands what you say. For example, a phrase like “Please come home after the movie” can mean different things to children and parents.

But there will be no disagreement, to put it more precisely - for example: "Come home immediately after the end of the film, do not go anywhere along the way."

But there will be no disagreement, to put it more precisely - for example: "Come home immediately after the end of the film, do not go anywhere along the way."

- Assign responsibilities. For example, “I am responsible for you and provide for you. You also have responsibilities: do your homework, take care of the cat, and clean your room at least once a week.”

- Agree in advance on the consequences of not following the rules. They also need to be formulated as clearly as possible.

- Praise your child when they follow the rules. For example, "Thank you for coming home right after the movie, as we agreed."

- Be prepared to discuss and adjust the rules as the child gets older or behaves more responsibly—for example, by “postponing” home time later. This will be a proof of your trust for him and will show that you recognize his right to independence.

Consequences as part of adolescent discipline

Sometimes adolescents behave as if they are specifically testing parental prohibitions and established rules for strength. A good way to deal with this behavior is to have natural consequences. Here are some ways.

A good way to deal with this behavior is to have natural consequences. Here are some ways.

Sanctions must match the violation

Good interventions are those that make the child think about the particular aspect of the behavior that causes problems. In addition, it is more fair to the child. For example, if he arrives home later than the agreed hour, a suitable measure might be to demand an earlier return next time.

Termination of cooperation

This method helps the child to understand someone else's point of view and teaches that it is necessary not only to take, but also to give. For example, if a teenager wants you to drive him to class or visit, you can say that you will do this if he follows the rules and fulfills his obligations. Communicate such consequences in advance, for example: “If you want me to continue to give you a ride, come home on time. If you are late, next time you will have to take the bus or walk.”

Revoke privileges

This measure should be used sparingly - if used too often, it will not work. The idea is to temporarily deprive a teenager of what he likes - trips to visit friends, access to TV or the Internet. In this case, it is also better to warn the child in advance about the consequences so that he can evaluate for himself whether the game is worth the candle or it is better to follow the rules. There is no need to deprive privileges for a long time, otherwise the teenager will get used to the new state of affairs. A couple of days after the offense is enough. And these should be precisely privileges, and not activities or contacts that are vital for the child.

The idea is to temporarily deprive a teenager of what he likes - trips to visit friends, access to TV or the Internet. In this case, it is also better to warn the child in advance about the consequences so that he can evaluate for himself whether the game is worth the candle or it is better to follow the rules. There is no need to deprive privileges for a long time, otherwise the teenager will get used to the new state of affairs. A couple of days after the offense is enough. And these should be precisely privileges, and not activities or contacts that are vital for the child.

Whatever educational measures you choose, reflection will help to reinforce the desired behavior. Every time something goes wrong and the rules are not being followed, invite your child to think about what they can do to change their behavior in the future. Remind that you worked out the rules together and he agreed to them. Ask how he would have acted in your place and what measures he would consider adequate and effective.

/pic3667676.jpg)