Does caffeine cause migraines

The Ambiguous Role of Caffeine in Migraine Headache: From Trigger to Treatment

1. Steiner T.J., Stovner L.J., Birbeck G.L. Migraine: The seventh disabler. Headache. 2013;53:227–229. doi: 10.1111/head.12034. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2. Collaborators G.H. Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:954–976. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1–211. doi: 10.1177/0333102417738202. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

4. Alstadhaug K.B., Andreou A.P. Caffeine and Primary (Migraine) Headaches-Friend or Foe? Front. Neurol. 2019;10:1275. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.01275. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

5. Hindiyeh N.A. , Zhang N., Farrar M., Banerjee P., Lombard L., Aurora S.K. The Role of Diet and Nutrition in Migraine Triggers and Treatment: A Systematic Literature Review. Headache. 2020 doi: 10.1111/head.13836. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. Lipton R.B., Diener H.C., Robbins M.S., Garas S.Y., Patel K. Caffeine in the management of patients with headache. J. Headache Pain. 2017;18:107. doi: 10.1186/s10194-017-0806-2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. Spencer B. Caffeine withdrawal: A model for migraine? Headache. 2002;42:561–562. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2002.02137.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Ward N., Whitney C., Avery D., Dunner D. The analgesic effects of caffeine in headache. Pain. 1991;44:151–155. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90129-L. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

9. Ogawa N., Ueki H. Clinical importance of caffeine dependence and abuse. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2007;61:263–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819. 2007.01652.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2007.01652.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10. Heckman M.A., Weil J., Gonzalez de Mejia E. Caffeine (1, 3, 7-trimethylxanthine) in foods: A comprehensive review on consumption, functionality, safety, and regulatory matters. J. Food Sci. 2010;75:R77–R87. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2010.01561.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

11. Fried N.T., Elliott M.B., Oshinsky M.L. The Role of Adenosine Signaling in Headache: A Review. Brain Sci. 2017;7:30. doi: 10.3390/brainsci7030030. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. Baratloo A., Rouhipour A., Forouzanfar M.M., Safari S., Amiri M., Negida A. The Role of Caffeine in Pain Management: A Brief Literature Review. Anesth Pain Med. 2016;6:e33193. doi: 10.5812/aapm.33193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

13. Haskell-Ramsay C.F., Jackson P.A., Forster J.S., Dodd F.L., Bowerbank S.L., Kennedy D.O. The Acute Effects of Caffeinated Black Coffee on Cognition and Mood in Healthy Young and Older Adults. Nutrients. 2018;10:1386. doi: 10.3390/nu10101386. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Nutrients. 2018;10:1386. doi: 10.3390/nu10101386. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

14. Nawrot P., Jordan S., Eastwood J., Rotstein J., Hugenholtz A., Feeley M. Effects of caffeine on human health. Food Addit. Contam. 2003;20:1–30. doi: 10.1080/0265203021000007840. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

15. Miners J.O., Birkett D.J. The use of caffeine as a metabolic probe for human drug metabolizing enzymes. Gen. Pharmacol. 1996;27:245–249. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(95)02014-4. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

16. Grosso G., Godos J., Galvano F., Giovannucci E.L. Coffee, Caffeine, and Health Outcomes: An Umbrella Review. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2017;37:131–156. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071816-064941. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

17. Nehlig A. Effects of coffee/caffeine on brain health and disease: What should I tell my patients? Pract. Neurol. 2016;16:89–95. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2015-001162. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

18. Cornelis M.C. The Impact of Caffeine and Coffee on Human Health. Nutrients. 2019;11:416. doi: 10.3390/nu11020416. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Cornelis M.C. The Impact of Caffeine and Coffee on Human Health. Nutrients. 2019;11:416. doi: 10.3390/nu11020416. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

19. Bruce C., Yates D.H., Thomas P.S. Caffeine decreases exhaled nitric oxide. Thorax. 2002;57:361–363. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.4.361. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

20. Umemura T., Ueda K., Nishioka K., Hidaka T., Takemoto H., Nakamura S., Jitsuiki D., Soga J., Goto C., Chayama K., et al. Effects of acute administration of caffeine on vascular function. Am. J. Cardiol. 2006;98:1538–1541. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.06.058. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

21. Higashi Y. Coffee and Endothelial Function: A Coffee Paradox? Nutrients. 2019;11:2104. doi: 10.3390/nu11092104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

22. Joris P.J., Mensink R.P., Adam T.C., Liu T.T. Cerebral Blood Flow Measurements in Adults: A Review on the Effects of Dietary Factors and Exercise. Nutrients. 2018;10:530. doi: 10.3390/nu10050530. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Nutrients. 2018;10:530. doi: 10.3390/nu10050530. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

23. Gererd D. Coffee and Health. John Libbey Eurotext; Esher, UK: 1994. [Google Scholar]

24. Vidyasagar R., Greyling A., Draijer R., Corfield D.R., Parkes L.M. The effect of black tea and caffeine on regional cerebral blood flow measured with arterial spin labeling. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:963–968. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

25. Haanes K.A., Labastida-Ramírez A., Chan K.Y., de Vries R., Shook B., Jackson P., Zhang J., Flores C.M., Danser A.H.J., Villalón C.M., et al. Characterization of the trigeminovascular actions of several adenosine A. J. Headache Pain. 2018;19:41. doi: 10.1186/s10194-018-0867-x. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

26. Yang H.S., Liang Z., Yao J.F., Shen X., Frederick B.D., Tong Y. Vascular effects of caffeine found in BOLD fMRI. J. Neurosci. Res. 2019;97:456–466. doi: 10.1002/jnr.24360. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

doi: 10.1002/jnr.24360. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

27. Xu F., Liu P., Pekar J.J., Lu H. Does acute caffeine ingestion alter brain metabolism in young adults? Neuroimage. 2015;110:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.01.046. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

28. Blaha M., Benes V., Douville C.M., Newell D.W. The effect of caffeine on dilated cerebral circulation and on diagnostic CO2 reactivity testing. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2007;14:464–467. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2006.03.019. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

29. Lunt M.J., Ragab S., Birch A.A., Schley D., Jenkinson D.F. Comparison of caffeine-induced changes in cerebral blood flow and middle cerebral artery blood velocity shows that caffeine reduces middle cerebral artery diameter. Physiol. Meas. 2004;25:467–474. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/25/2/006. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

30. Addicott M.A., Yang L.L., Peiffer A.M., Burnett L.R., Burdette J.H., Chen M.Y. , Hayasaka S., Kraft R.A., Maldjian J.A., Laurienti P.J. The effect of daily caffeine use on cerebral blood flow: How much caffeine can we tolerate? Hum. Brain Mapp. 2009;30:3102–3114. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20732. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

, Hayasaka S., Kraft R.A., Maldjian J.A., Laurienti P.J. The effect of daily caffeine use on cerebral blood flow: How much caffeine can we tolerate? Hum. Brain Mapp. 2009;30:3102–3114. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20732. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

31. Couturier E.G., Laman D.M., van Duijn M.A., van Duijn H. Influence of caffeine and caffeine withdrawal on headache and cerebral blood flow velocities. Cephalalgia. 1997;17:188–190. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1997.1703188.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

32. Sigmon S.C., Herning R.I., Better W., Cadet J.L., Griffiths R.R. Caffeine withdrawal, acute effects, tolerance, and absence of net beneficial effects of chronic administration: Cerebral blood flow velocity, quantitative EEG, and subjective effects. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2009;204:573–585. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1489-4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

33. Marchand S., Li J., Charest J. Effects of caffeine on analgesia from transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;333:325–326. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508033330521. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;333:325–326. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508033330521. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

34. Derry C.J., Derry S., Moore R.A. Caffeine as an analgesic adjuvant for acute pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009281.pub3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

35. Laska E.M., Sunshine A., Mueller F., Elvers W.B., Siegel C., Rubin A. Caffeine as an analgesic adjuvant. JAMA. 1984;251:1711–1718. doi: 10.1001/jama.1984.03340370043028. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

36. Zaeem Z., Zhou L., Dilli E. Headaches: A Review of the Role of Dietary Factors. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2016;16:101. doi: 10.1007/s11910-016-0702-1. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

37. Liang J.F., Wang S.J. Hypnic headache: A review of clinical features, therapeutic options and outcomes. Cephalalgia. 2014;34:795–805. doi: 10.1177/0333102414537914. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

38. Basurto Ona X., Osorio D. , Bonfill Cosp X. Drug therapy for treating post-dural puncture headache. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007887.pub3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

, Bonfill Cosp X. Drug therapy for treating post-dural puncture headache. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007887.pub3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

39. Han M.E., Kim H.J., Lee Y.S., Kim D.H., Choi J.T., Pan C.S., Yoon S., Baek S.Y., Kim B.S., Kim J.B., et al. Regulation of cerebrospinal fluid production by caffeine consumption. BMC Neurosci. 2009;10:110. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-10-110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

40. Kalladka D., Siddiqui A., Tyagi A., Newman E. Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome secondary to caffeine withdrawal. Scott. Med. J. 2018;63:22–24. doi: 10.1177/0036933017706892. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

41. Chattha N., Webb T., Hargroves D., Balogun I., Bertoni M. Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome after sudden caffeine withdrawal. Br. J. Hosp. Med. (Lond.) 2019;80:730–731. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2019.80.12.730. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

42. Manzoni G.C. Cluster headache and lifestyle: Remarks on a population of 374 male patients. Cephalalgia. 1999;19:88–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1999.019002088.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Manzoni G.C. Cluster headache and lifestyle: Remarks on a population of 374 male patients. Cephalalgia. 1999;19:88–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1999.019002088.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

43. Scher A.I., Stewart W.F., Lipton R.B. Caffeine as a risk factor for chronic daily headache: A population-based study. Neurology. 2004;63:2022–2027. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000145760.37852.ED. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

44. Kluonaitis K., Petrauskiene E., Ryliskiene K. Clinical characteristics and overuse patterns of medication overuse headache: Retrospective case-series study. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2017;163:124–127. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2017.10.029. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

45. Dong Z., Chen X., Steiner T.J., Hou L., Di H., He M., Dai W., Pan M., Zhang M., Liu R., et al. Medication-overuse headache in China: Clinical profile, and an evaluation of the ICHD-3 beta diagnostic criteria. Cephalalgia. 2015;35:644–651. doi: 10.1177/0333102414552533. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

46. Diamond S., Balm T.K., Freitag F.G. Ibuprofen plus caffeine in the treatment of tension-type headache. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000;68:312–319. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2000.109353. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Diamond S., Balm T.K., Freitag F.G. Ibuprofen plus caffeine in the treatment of tension-type headache. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000;68:312–319. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2000.109353. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

47. Jacobs B., Dussor G. Neurovascular contributions to migraine: Moving beyond vasodilation. Neuroscience. 2016;338:130–144. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.06.012. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

48. Guieu R., Devaux C., Henry H., Bechis G., Pouget J., Mallet D., Sampieri F., Juin M., Gola R., Rochat H. Adenosine and migraine. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 1998;25:55–58. doi: 10.1017/S0317167100033497. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

49. Aurora S.K., Kori S.H., Barrodale P., McDonald S.A., Haseley D. Gastric stasis in migraine: More than just a paroxysmal abnormality during a migraine attack. Headache. 2006;46:57–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00311.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

50. Silberstein S. Gastrointestinal manifestations of migraine: Meeting the treatment challenges. Headache. 2013;53:1–3. doi: 10.1111/head.12113. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Headache. 2013;53:1–3. doi: 10.1111/head.12113. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

51. Messlinger K., Lennerz J.K., Eberhardt M., Fischer M.J. CGRP and NO in the trigeminal system: Mechanisms and role in headache generation. Headache. 2012;52:1411–1427. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2012.02212.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

52. González S., Salazar N., Ruiz-Saavedra S., Gómez-Martín M., de Los Reyes-Gavilán C.G., Gueimonde M. Long-Term Coffee Consumption is Associated with Fecal Microbial Composition in Humans. Nutrients. 2020;12:1287. doi: 10.3390/nu12051287. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

53. Arzani M., Jahromi S.R., Ghorbani Z., Vahabizad F., Martelletti P., Ghaemi A., Sacco S., Togha M., On behalf of the School of Advanced Studies of the European Headache Federation (EHF-SAS) Gut-brain Axis and migraine headache: A comprehensive review. J. Headache Pain. 2020;21:15. doi: 10.1186/s10194-020-1078-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

54. Martami F., Togha M., Seifishahpar M., Ghorbani Z., Ansari H., Karimi T., Jahromi S.R. The effects of a multispecies probiotic supplement on inflammatory markers and episodic and chronic migraine characteristics: A randomized double-blind controlled trial. Cephalalgia. 2019;39:841–853. doi: 10.1177/0333102418820102. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Martami F., Togha M., Seifishahpar M., Ghorbani Z., Ansari H., Karimi T., Jahromi S.R. The effects of a multispecies probiotic supplement on inflammatory markers and episodic and chronic migraine characteristics: A randomized double-blind controlled trial. Cephalalgia. 2019;39:841–853. doi: 10.1177/0333102418820102. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

55. Lipton R.B., Pavlovic J.M., Haut S.R., Grosberg B.M., Buse D.C. Methodological issues in studying trigger factors and premonitory features of migraine. Headache. 2014;54:1661–1669. doi: 10.1111/head.12464. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

56. Peroutka S.J. What turns on a migraine? A systematic review of migraine precipitating factors. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2014;18:454. doi: 10.1007/s11916-014-0454-z. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

57. Mollaoğlu M. Trigger factors in migraine patients. J. Health Psychol. 2013;18:984–994. doi: 10.1177/1359105312446773. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

58. Hoffmann J. , Recober A. Migraine and triggers: Post hoc ergo propter hoc? Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2013;17:370. doi: 10.1007/s11916-013-0370-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

, Recober A. Migraine and triggers: Post hoc ergo propter hoc? Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2013;17:370. doi: 10.1007/s11916-013-0370-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

59. Wöber C., Wöber-Bingöl C. Triggers of migraine and tension-type headache. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2010;97:161–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Rockett F.C., Castro K., de Oliveira V.R., da Silveira P.A., Chaves M.L.F., Perry I.D.S. Perceived migraine triggers: Do dietary factors play a role? Nutr. Hosp. 2012;27:483–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Aguggia M., Saracco M.G. Pathophysiology of migraine chronification. Neurol. Sci. 2010;31:S15–S17. doi: 10.1007/s10072-010-0264-y. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

62. Bigal M.E., Lipton R.B. Modifiable risk factors for migraine progression. Headache. 2006;46:1334–1343. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00577.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

63. Guendler V.Z., Mercante J.P., Ribeiro R.T., Zukerman E., Peres M.F. Factors associated with acute medication overuse in chronic migraine patients. Einstein (Sao Paulo) 2012;10:312–317. doi: 10.1590/S1679-45082012000300010. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Einstein (Sao Paulo) 2012;10:312–317. doi: 10.1590/S1679-45082012000300010. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

64. Bergman E.A., Massey L.K., Wise K.J., Sherrard D.J. Effects of dietary caffeine on renal handling of minerals in adult women. Life Sci. 1990;47:557–564. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(90)90616-Y. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

65. Kirkland A.E., Sarlo G.L., Holton K.F. The Role of Magnesium in Neurological Disorders. Nutrients. 2018;10:730. doi: 10.3390/nu10060730. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

66. Wöber C., Brannath W., Schmidt K., Kapitan M., Rudel E., Wessely P., Wöber-Bingöl C., Group P.S. Prospective analysis of factors related to migraine attacks: The PAMINA study. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:304–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01279.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

67. Seal A.D., Bardis C.N., Gavrieli A., Grigorakis P., Adams J.D., Arnaoutis G., Yannakoulia M., Kavouras S.A. Coffee with High but Not Low Caffeine Content Augments Fluid and Electrolyte Excretion at Rest. Front. Nutr. 2017;4:40. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2017.00040. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Front. Nutr. 2017;4:40. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2017.00040. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

68. Couturier E.G., Hering R., Steiner T.J. Weekend attacks in migraine patients: Caused by caffeine withdrawal? Cephalalgia. 1992;12:99–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1992.1202099.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

69. Schulte L.H., Jürgens T.P., May A. Photo-, osmo- and phonophobia in the premonitory phase of migraine: Mistaking symptoms for triggers? J. Headache Pain. 2015;16:14. doi: 10.1186/s10194-015-0495-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

70. Yalcin N., Chen S.P., Yu E.S., Liu T.T., Yen J.C., Atalay Y.B., Qin T., Celik F., van den Maagdenberg A.M., Moskowitz M.A., et al. Caffeine does not affect susceptibility to cortical spreading depolarization in mice. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2019;39:740–750. doi: 10.1177/0271678X18768955. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

71. Goadsby P.J., Silberstein S.D. Migraine triggers: Harnessing the messages of clinical practice. Neurology. 2013;80:424–425. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31827f100c. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Neurology. 2013;80:424–425. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31827f100c. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

72. Martin P.R. Managing headache triggers: Think ‘coping’ not ‘avoidance’ Cephalalgia. 2010;30:634–637. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2009.01989.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

73. Mikulec A.A., Faraji F., Kinsella L.J. Evaluation of the efficacy of caffeine cessation, nortriptyline, and topiramate therapy in vestibular migraine and complex dizziness of unknown etiology. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2012;33:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2011.04.010. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

74. Lee M.J., Choi H.A., Choi H., Chung C.S. Caffeine discontinuation improves acute migraine treatment: A prospective clinic-based study. J. Headache Pain. 2016;17:71. doi: 10.1186/s10194-016-0662-5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

75. Mostofsky E., Mittleman M.A., Buettner C., Li W., Bertisch S.M. Prospective Cohort Study of Caffeinated Beverage Intake as a Potential Trigger of Headaches among Migraineurs. Am. J. Med. 2019;132:984–991. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.02.015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Am. J. Med. 2019;132:984–991. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.02.015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

76. Beh S.C., Masrour S., Smith S.V., Friedman D.I. The Spectrum of Vestibular Migraine: Clinical Features, Triggers, and Examination Findings. Headache. 2019;59:727–740. doi: 10.1111/head.13484. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

77. Tai M.S., Yap J.F., Goh C.B. Dietary trigger factors of migraine and tension-type headache in a South East Asian country. J. Pain Res. 2018;11:1255–1261. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S158151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

78. Taheri S. Effect of exclusion of frequently consumed dietary triggers in a cohort of children with chronic primary headache. Nutr. Health. 2017;23:47–50. doi: 10.1177/0260106016688699. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

79. Park J.W., Chu M.K., Kim J.M., Park S.G., Cho S.J. Analysis of Trigger Factors in Episodic Migraineurs Using a Smartphone Headache Diary Applications. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0149577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149577. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2016;11:e0149577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149577. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

80. Peris F., Donoghue S., Torres F., Mian A., Wöber C. Towards improved migraine management: Determining potential trigger factors in individual patients. Cephalalgia. 2017;37:452–463. doi: 10.1177/0333102416649761. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

81. Rist P.M., Buring J.E., Kurth T. Dietary patterns according to headache and migraine status: A cross-sectional study. Cephalalgia. 2015;35:767–775. doi: 10.1177/0333102414560634. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

82. Fraga M.D., Pinho R.S., Andreoni S., Vitalle M.S., Fisberg M., Peres M.F., Vilanova L.C., Masruha M.R. Trigger factors mainly from the environmental type are reported by adolescents with migraine. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2013;71:290–293. doi: 10.1590/0004-282X20130023. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

83. Neut D., Fily A., Cuvellier J.C., Vallée L. The prevalence of triggers in paediatric migraine: A questionnaire study in 102 children and adolescents. J. Headache Pain. 2012;13:61–65. doi: 10.1007/s10194-011-0397-2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

J. Headache Pain. 2012;13:61–65. doi: 10.1007/s10194-011-0397-2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

84. Schürks M., Buring J.E., Kurth T. Migraine features, associated symptoms and triggers: A principal component analysis in the Women’s Health Study. Cephalalgia. 2011;31:861–869. doi: 10.1177/0333102411401635. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

85. Yadav R.K., Kalita J., Misra U.K. A study of triggers of migraine in India. Pain Med. 2010;11:44–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00725.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

86. Hauge A.W., Kirchmann M., Olesen J. Trigger factors in migraine with aura. Cephalalgia. 2010;30:346–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2009.01930.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

87. Andress-Rothrock D., King W., Rothrock J. An analysis of migraine triggers in a clinic-based population. Headache. 2010;50:1366–1370. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2010.01753.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

88. Chakravarty A., Mukherjee A., Roy D. Trigger factors in childhood migraine: A clinic-based study from eastern India. J. Headache Pain. 2009;10:375–380. doi: 10.1007/s10194-009-0147-x. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Chakravarty A., Mukherjee A., Roy D. Trigger factors in childhood migraine: A clinic-based study from eastern India. J. Headache Pain. 2009;10:375–380. doi: 10.1007/s10194-009-0147-x. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

89. Fukui P.T., Gonçalves T.R., Strabelli C.G., Lucchino N.M., Matos F.C., Santos J.P., Zukerman E., Zukerman-Guendler V., Mercante J.P., Masruha M.R., et al. Trigger factors in migraine patients. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2008;66:494–499. doi: 10.1590/S0004-282X2008000400011. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

90. Wöber C., Holzhammer J., Zeitlhofer J., Wessely P., Wöber-Bingöl C. Trigger factors of migraine and tension-type headache: Experience and knowledge of the patients. J. Headache Pain. 2006;7:188–195. doi: 10.1007/s10194-006-0305-3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

91. Takeshima T., Ishizaki K., Fukuhara Y., Ijiri T., Kusumi M., Wakutani Y., Mori M., Kawashima M., Kowa H., Adachi Y., et al. Population-based door-to-door survey of migraine in Japan: The Daisen study. Headache. 2004;44:8–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.04004.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Headache. 2004;44:8–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.04004.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

92. Bánk J., Márton S. Hungarian migraine epidemiology. Headache. 2000;40:164–169. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2000.00023.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

93. Van den Bergh V., Amery W.K., Waelkens J. Trigger factors in migraine: A study conducted by the Belgian Migraine Society. Headache. 1987;27:191–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1987.hed2704191.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

94. Hagen K., Thoresen K., Stovner L.J., Zwart J.A. High dietary caffeine consumption is associated with a modest increase in headache prevalence: Results from the Head-HUNT Study. J. Headache Pain. 2009;10:153–159. doi: 10.1007/s10194-009-0114-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

95. Baratloo A., Mirbaha S., Delavar Kasmaei H., Payandemehr P., Elmaraezy A., Negida A. Intravenous caffeine citrate vs. magnesium sulfate for reducing pain in patients with acute migraine headache; a prospective quasi-experimental study. Korean J. Pain. 2017;30:176–182. doi: 10.3344/kjp.2017.30.3.176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Korean J. Pain. 2017;30:176–182. doi: 10.3344/kjp.2017.30.3.176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

96. Goldstein J., Hagen M., Gold M. Results of a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, single-dose study comparing the fixed combination of acetaminophen, acetylsalicylic acid, and caffeine with ibuprofen for acute treatment of patients with severe migraine. Cephalalgia. 2014;34:1070–1078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

97. Pini L.A., Guerzoni S., Cainazzo M., Ciccarese M., Prudenzano M.P., Livrea P. Comparison of tolerability and efficacy of a combination of paracetamol + caffeine and sumatriptan in the treatment of migraine attack: A randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, cross-over study. J. Headache Pain. 2012;13:669–675. doi: 10.1007/s10194-012-0484-z. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

98. Láinez M.J., Galván J., Heras J., Vila C. Crossover, double-blind clinical trial comparing almotriptan and ergotamine plus caffeine for acute migraine therapy. Eur. J. Neurol. 2007;14:269–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01594.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Eur. J. Neurol. 2007;14:269–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01594.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

99. Goldstein J., Silberstein S.D., Saper J.R., Ryan R.E., Lipton R.B. Acetaminophen, aspirin, and caffeine in combination versus ibuprofen for acute migraine: Results from a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, single-dose, placebo-controlled study. Headache. 2006;46:444–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00376.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

100. Goldstein J., Silberstein S.D., Saper J.R., Elkind A.H., Smith T.R., Gallagher R.M., Battikha J.P., Hoffman H., Baggish J. Acetaminophen, aspirin, and caffeine versus sumatriptan succinate in the early treatment of migraine: Results from the ASSET trial. Headache. 2005;45:973–982. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05177.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

101. Peroutka S.J., Lyon J.A., Swarbrick J., Lipton R.B., Kolodner K., Goldstein J. Efficacy of diclofenac sodium softgel 100 mg with or without caffeine 100 mg in migraine without aura: A randomized, double-blind, crossover study. Headache. 2004;44:136–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.04029.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Headache. 2004;44:136–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.04029.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

If you have migraines, put down your coffee and read this

During medical school, a neurologist taught me that the number one cause of headaches in the US was coffee.

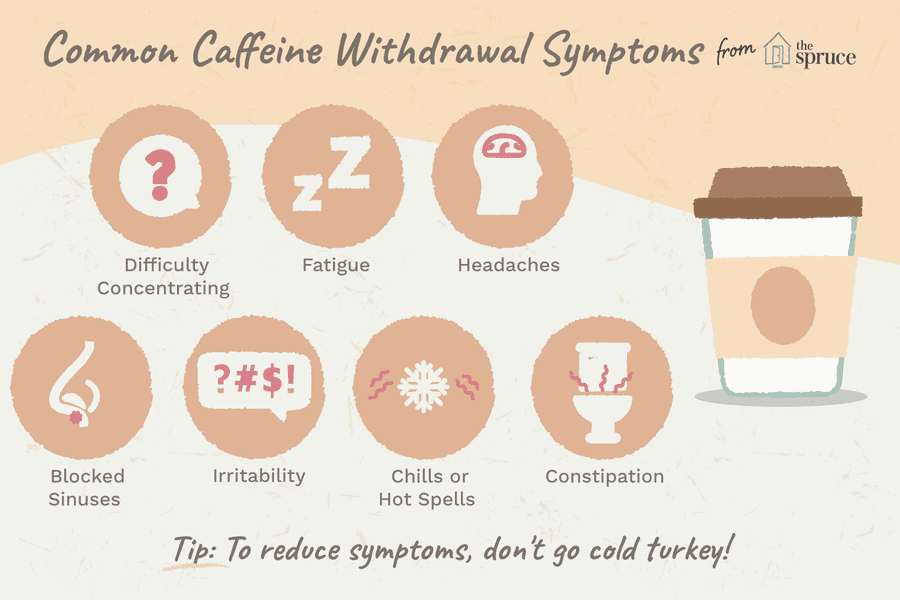

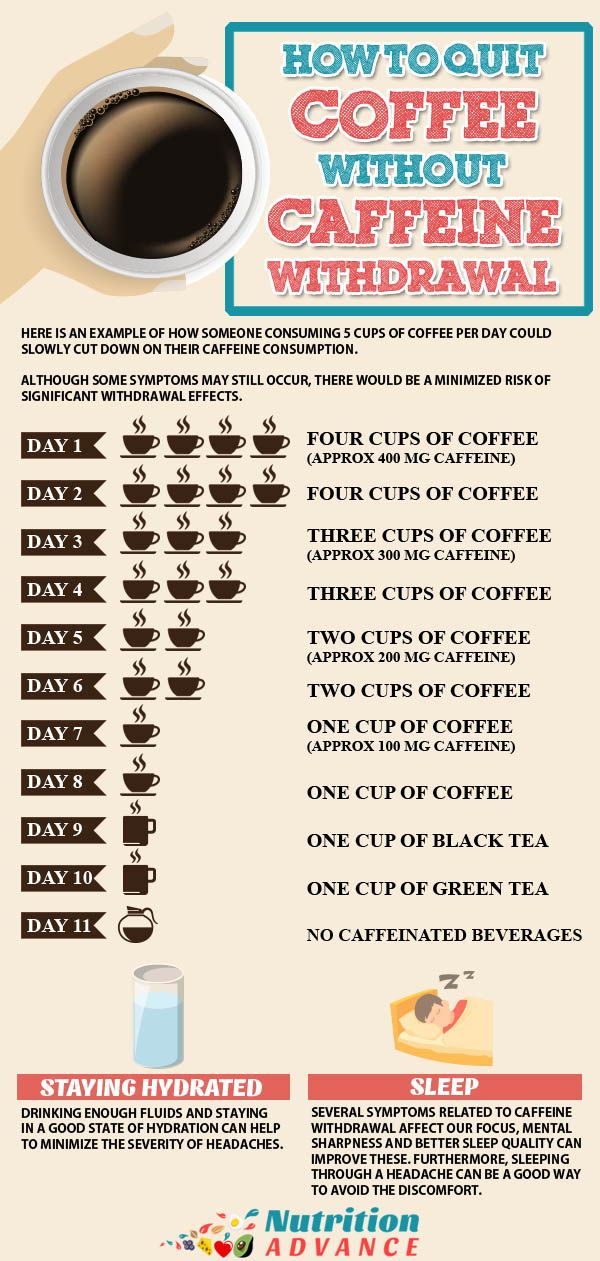

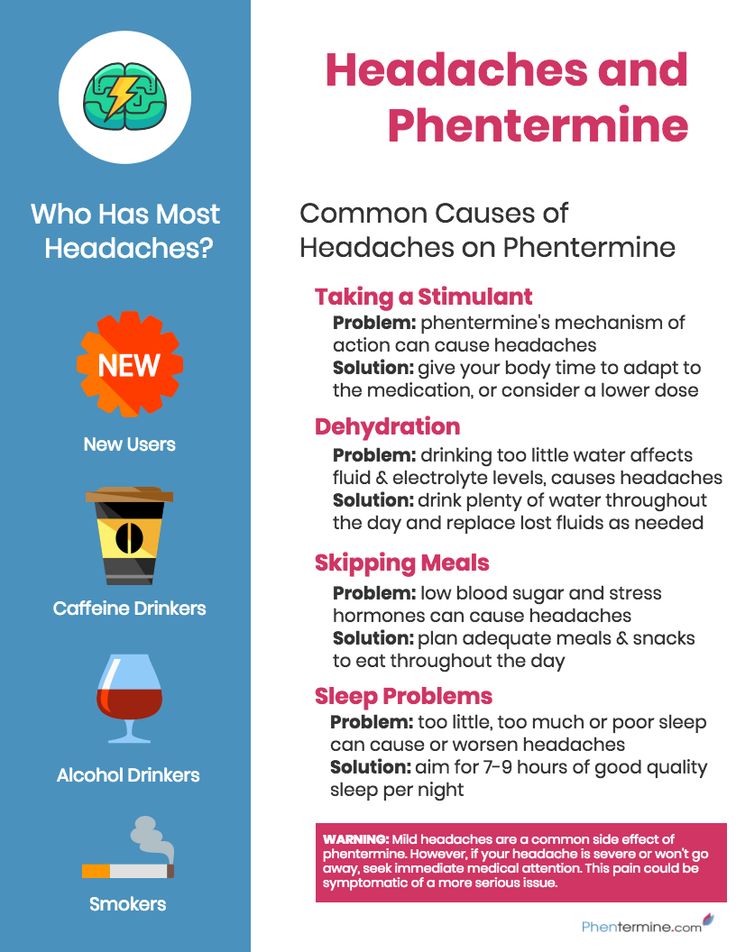

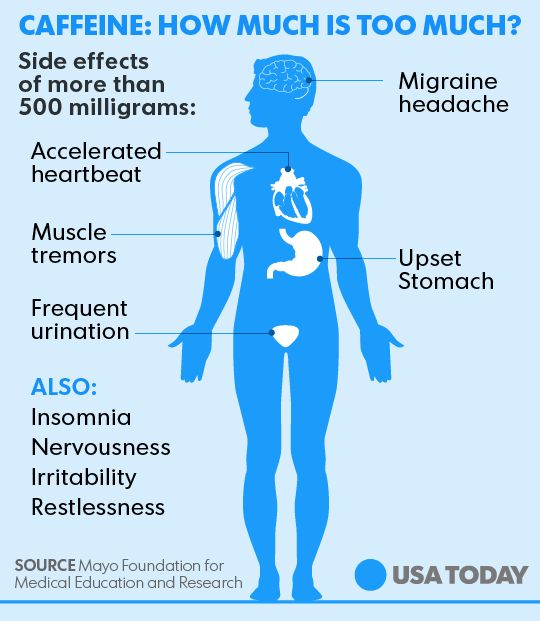

That was news to me! But it made more sense when he clarified that he meant lack of coffee. His point was that for people who regularly drink coffee, missing an early morning cup, or even just having your first cup later than usual, can trigger a caffeine withdrawal headache. And considering how many daily coffee drinkers there are (an estimated 158 million in the US alone), it’s likely that coffee withdrawal is among the most common causes of headaches.

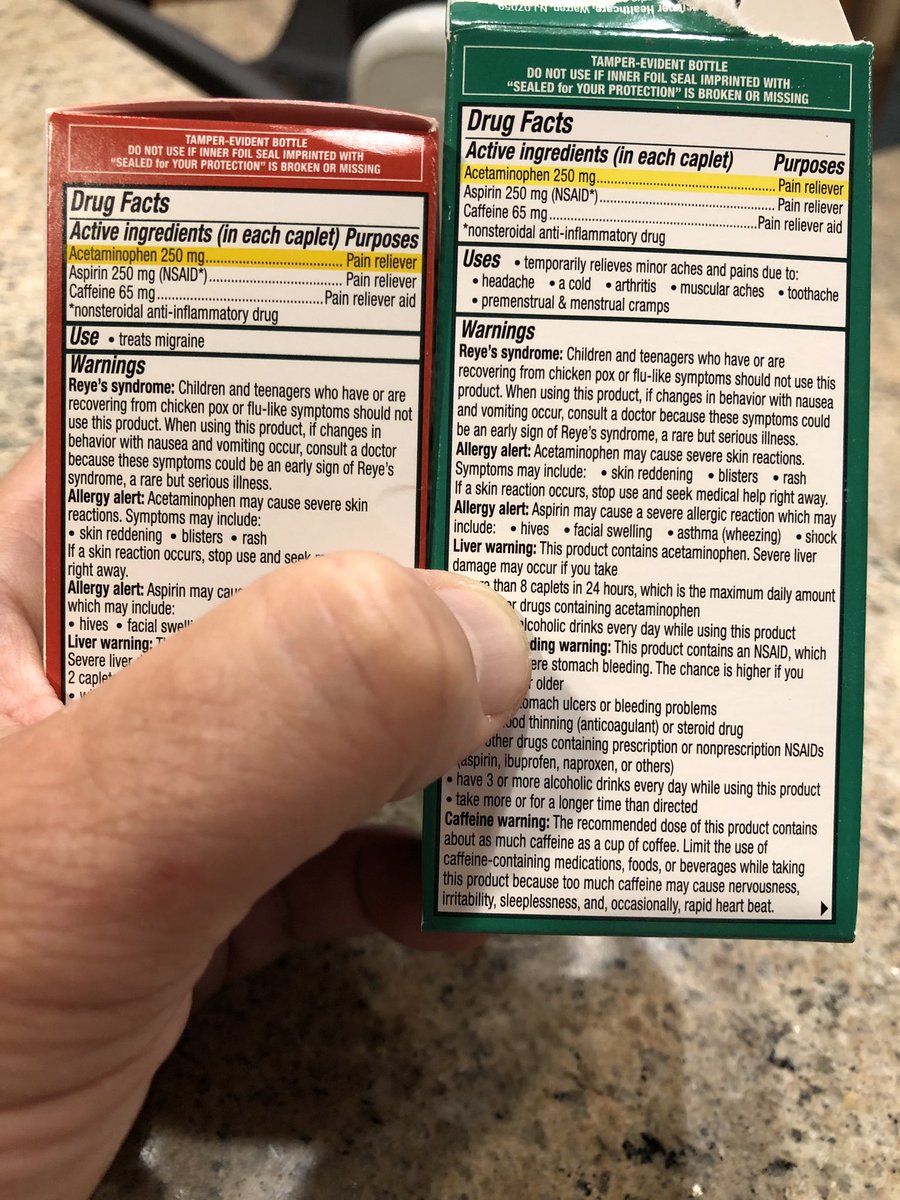

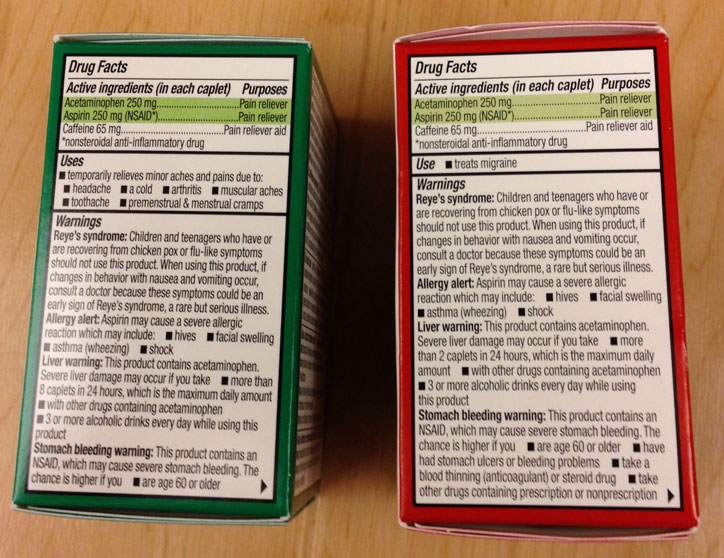

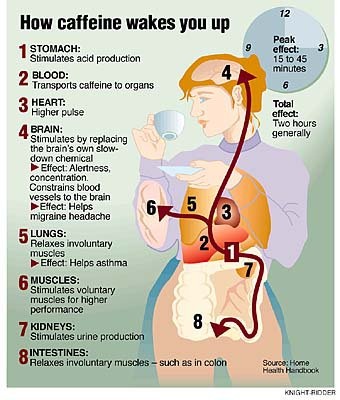

Later in my neurology rotation, I learned that caffeine is a major ingredient in many headache remedies, from over-the-counter medicines such as Excedrin and Anacin, to powerful prescription treatments such as Fioricet. The caffeine is supposed to make the other drugs in these combination remedies (such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen) work better; and, of course, it might be quite effective for caffeine-withdrawal headaches.

The caffeine is supposed to make the other drugs in these combination remedies (such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen) work better; and, of course, it might be quite effective for caffeine-withdrawal headaches.

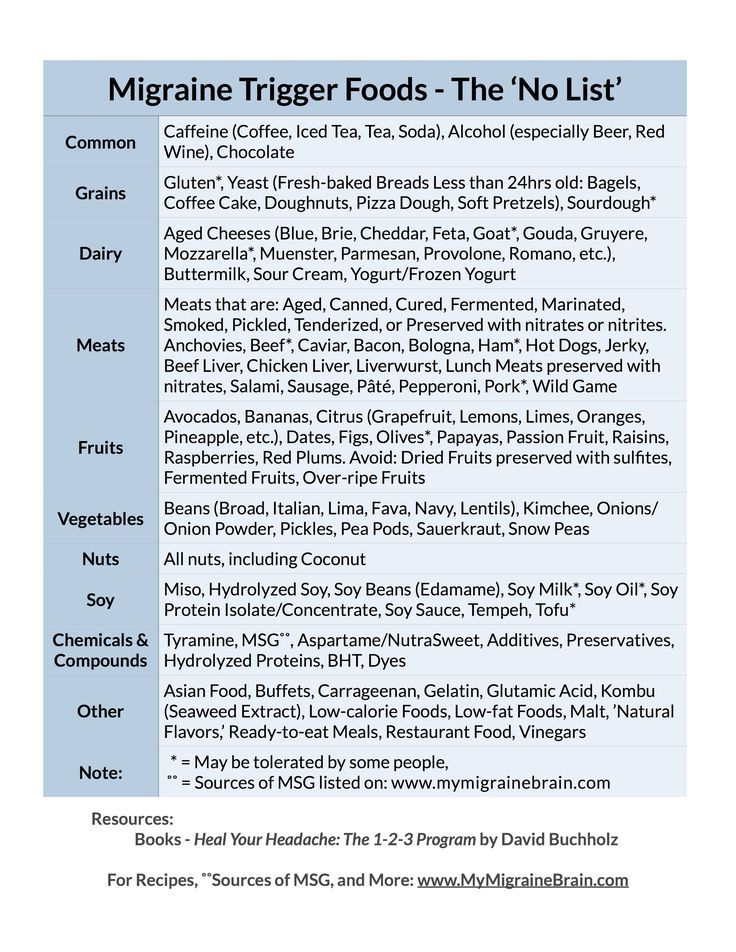

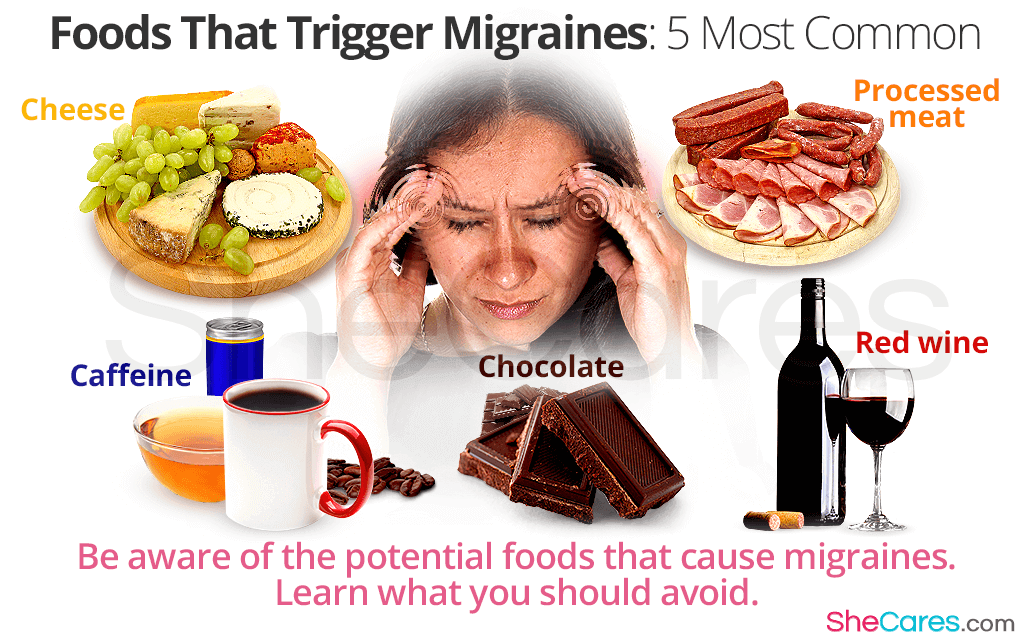

But then I learned that for people with migraine headaches, certain drugs, foods, and drinks should be avoided, as they can trigger migraines. At the top of this list? Coffee.

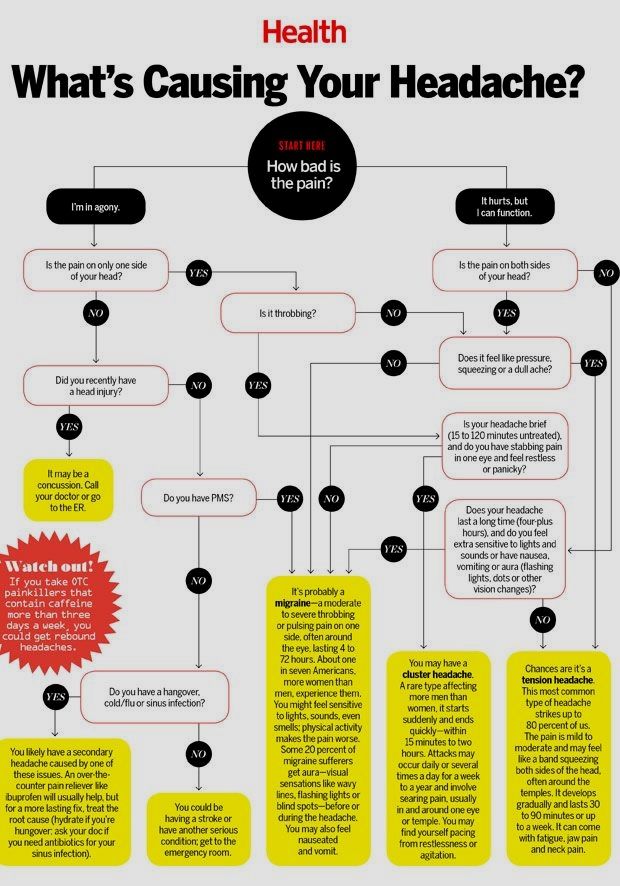

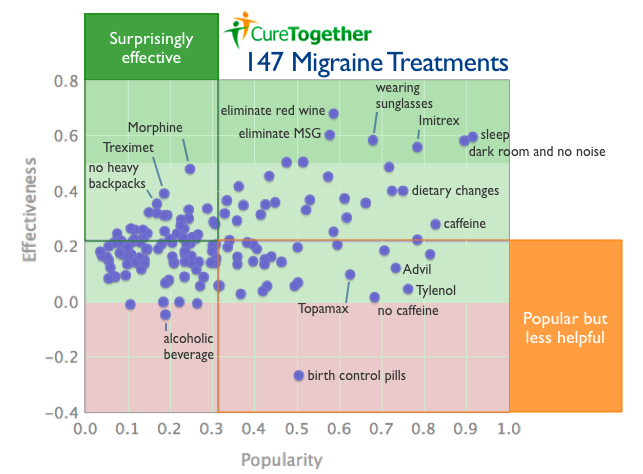

So, to review: the caffeine in coffee, tea, and other foods or drinks can help prevent a headache, treat a headache, and also trigger a headache. How can this be?

Migraine headaches: Still mysterious after all these years

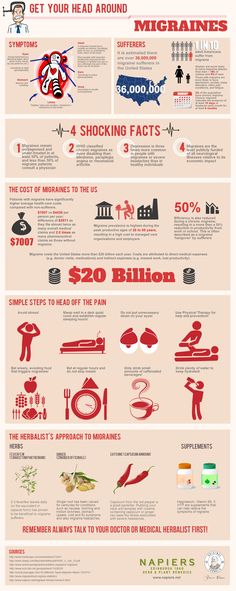

Migraine headaches are quite common: more than a billion people reportedly suffer from migraines worldwide. Yet, the cause has long been a mystery — and it still is.

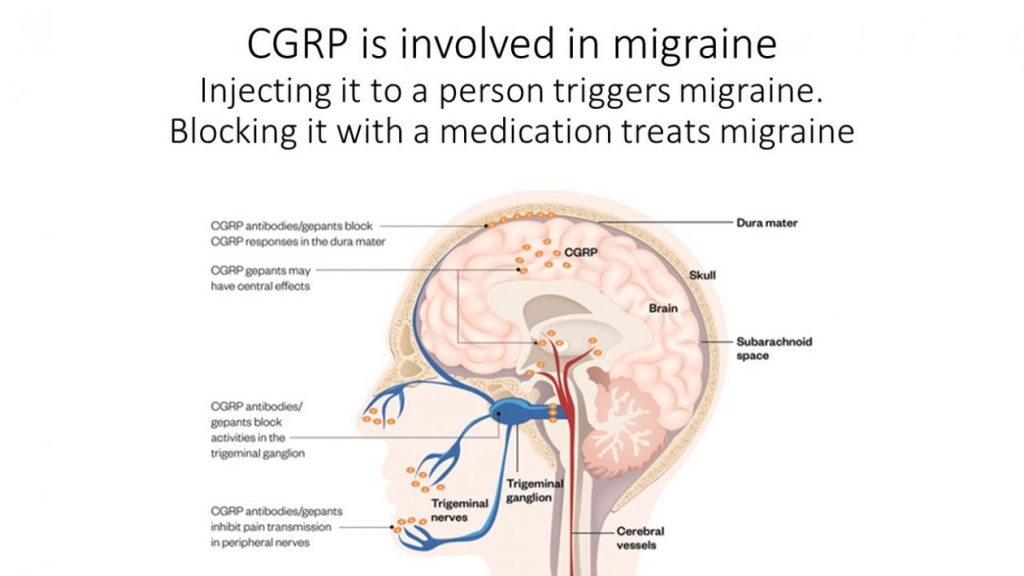

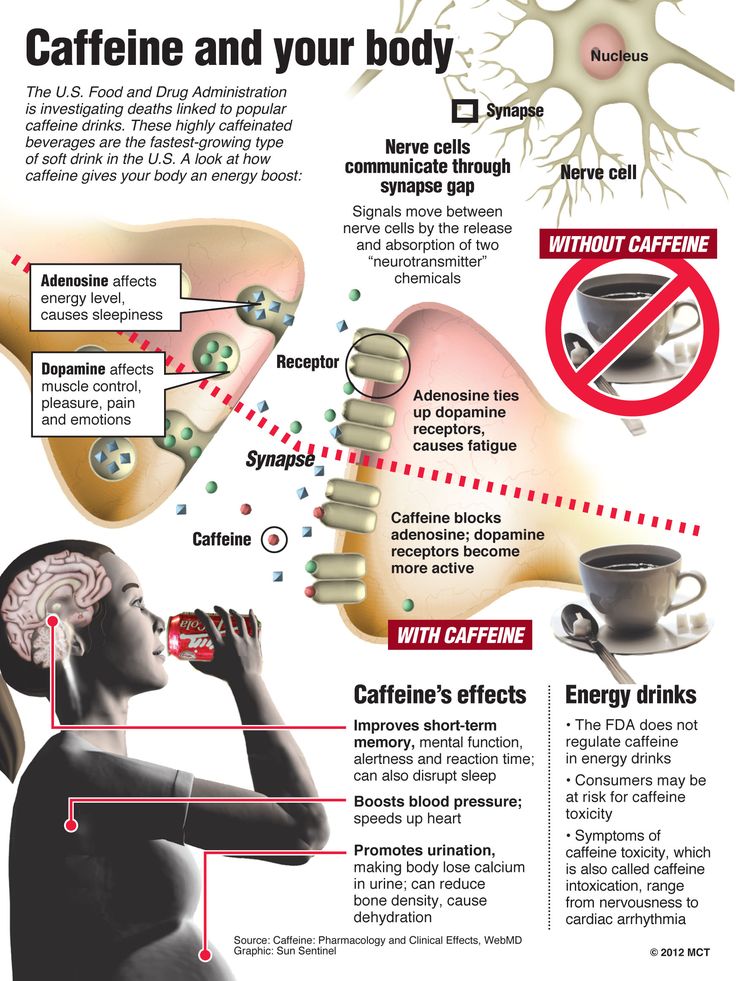

Until recently, the going theory was that blood vessels around the brain go into spasm, temporarily constricting and limiting blood flow. Then, when the blood vessels open up, the rush of incoming blood flow leads to the actual headache.

That theory has fallen out of favor. Now, the thinking is that migraines are due to waves of electrical activity spreading across the outer portions of the brain, leading to inflammation and overreactive nerve cells that send inappropriate pain signals. Why this begins in the first place is unknown.

Migraines tend to run in families, so genetic factors are likely important. In addition, chemical messengers within the brain, such as serotonin, may also play a central role in the development of migraines, though the mechanisms remain uncertain.

People prone to migraines may experience more headaches after coffee consumption (perhaps by effects on serotonin or brain electrical activity), but coffee itself, or the caffeine it contains, is not considered the actual cause of migraines. Certain foods or drinks like coffee are thought to trigger episodes of migraine, but the true cause is not known.

A new study about coffee and migraines: how much is too much?

In a new study published in the American Journal of Medicine, researchers (including several from the hospital where I work) asked 98 people with migraines to keep a diet diary that included how often they consumed caffeinated beverages (including coffee, tea, carbonated beverages, and energy drinks). This information was compared with how often they had migraines. Here’s what they found:

This information was compared with how often they had migraines. Here’s what they found:

- The odds of having a migraine increased for those drinking three or more caffeinated beverages per day, but not for those consuming one to two servings per day; the effect lasted through the day after caffeine consumption.

- It seemed to take less caffeine to trigger a headache in those who didn’t usually have much of it. Just one or two servings increased the risk of migraine in those who usually had less than one serving per day.

- The link between caffeine consumption and migraine held up even after accounting for other relevant factors such as alcohol consumption, sleep, and physical activity.

Interestingly, the link was observed regardless of whether the study subject believed that caffeine triggered their headaches.

One weakness of this study is that the researchers did not actually measure caffeine consumption. Instead, they defined one serving of a caffeinated beverage as 8 ounces of regular coffee, 6 ounces of tea, a 12-ounce can of caffeinated soda, or 2 ounces of an energy drink. But caffeine content in different caffeinated beverages can vary widely. For example, an 8-ounce serving of coffee from Starbucks can have twice the caffeine as a similar-sized serving from a Keurig K-Cup. They also did not include caffeine-containing foods in the study, although such amounts tend to be quite small compared with the beverages studied.

Instead, they defined one serving of a caffeinated beverage as 8 ounces of regular coffee, 6 ounces of tea, a 12-ounce can of caffeinated soda, or 2 ounces of an energy drink. But caffeine content in different caffeinated beverages can vary widely. For example, an 8-ounce serving of coffee from Starbucks can have twice the caffeine as a similar-sized serving from a Keurig K-Cup. They also did not include caffeine-containing foods in the study, although such amounts tend to be quite small compared with the beverages studied.

The bottom line

There is a lot about the connection between caffeine consumption and migraine headaches that remains uncertain. Until we know more, it seems wise to listen to your body: if you notice more headaches when you drink more coffee (or other caffeinated beverages), cut back. Fortunately, this latest research did not conclude that people with migraines should swear off coffee entirely.

If you like coffee as much as I do, it may seem unfair that you need to keep drinking it to prevent a headache. And if you’re prone to migraines, it might seem unfair that you have to limit your coffee intake to avoid headaches. Either way, you’d be right.

And if you’re prone to migraines, it might seem unfair that you have to limit your coffee intake to avoid headaches. Either way, you’d be right.

Migraine provocateurs

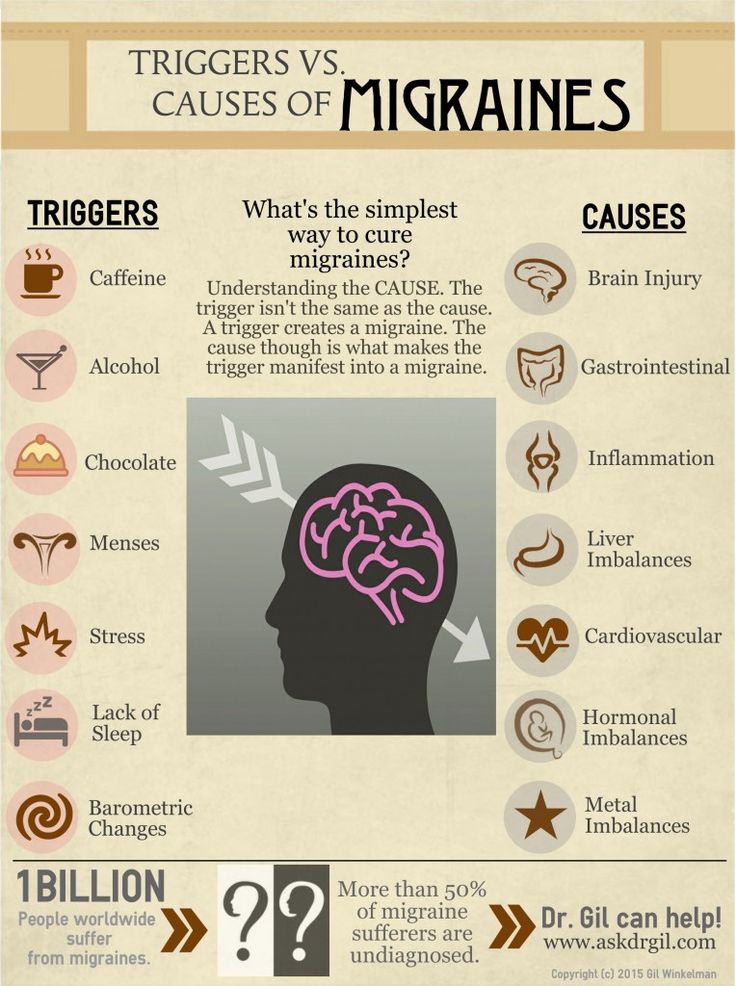

People with migraine often report that their attacks are triggered by some kind of trigger.

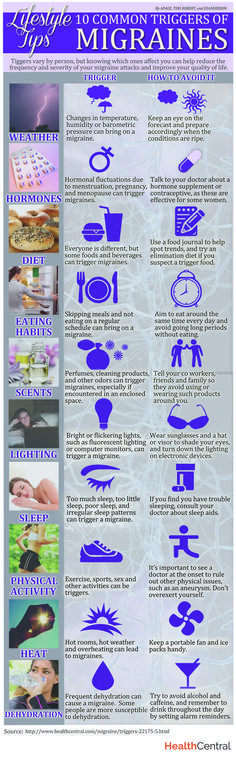

A study in which 200 people with migraine participated showed that 90% of them know at least one provocateur of their own migraine. The most frequently cited were physical or emotional stress (77%), menstruation (72% of women), bright lights or flashes of light (65%), and strong odors (61%) [1].

How do migraine triggers work?

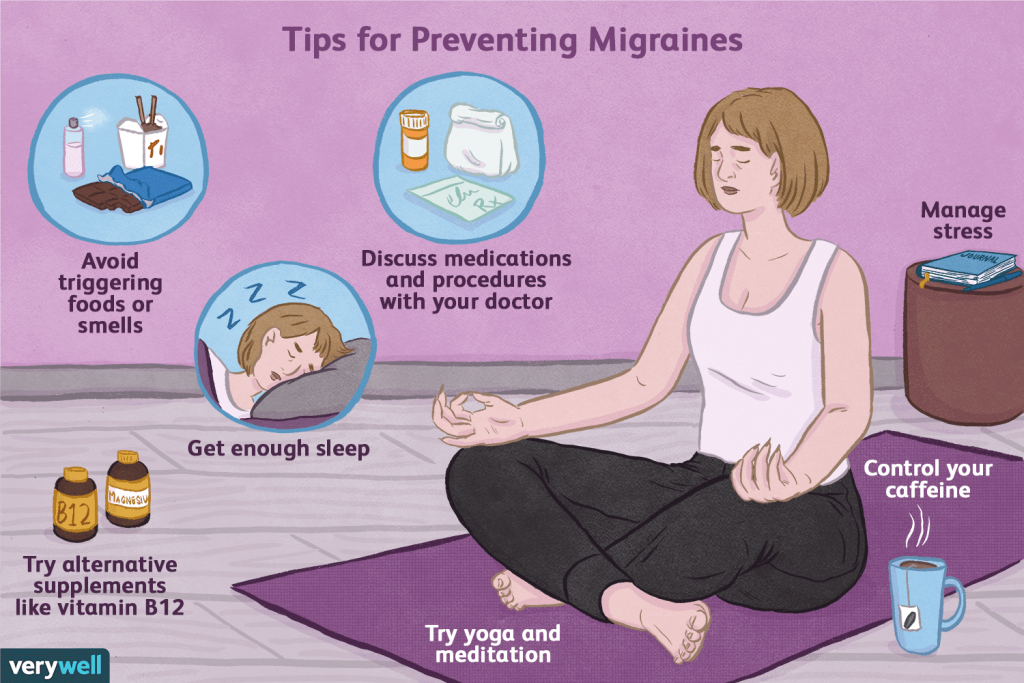

According to modern concepts, the cause of migraine is increased excitability of nerve cells (neurons). This is an inherited feature of the brain. Neurons in people suffering from migraine are very sensitive to various external and internal influences. They may be affected by:

- changes in hormone levels during the menstrual cycle,

- stress

- and, paradoxically, stress resolution,

- sleep disturbance (both insufficient and excessive sleep),

- alcohol,

- bright light or flashes of light.

In response to a trigger, electrical activity in easily excitable nerve cells changes and a cascade of biochemical disturbances is triggered that cause symptoms of a migraine attack [2].

What is important to know about migraine provocateurs (triggers)

- Sometimes "your" attack provocateur can cause it, sometimes not.

- A migraine attack requires a combination of two or more triggers.

- Something that is a trigger can also relieve a migraine attack (for example, caffeine).

- "Classic" migraine triggers: red wine, dark chocolate, stress - not all migraine sufferers provoke an attack.

- A few words about caffeine

After hearing from a doctor or a friend that caffeine can trigger an attack, many people with migraine completely refuse tea and coffee and look for a pill in horror after accidentally drinking a caffeinated drink.

Indeed, caffeine can trigger a migraine attack in some people. But you can still take it off!

But you can still take it off!

It works like this. During a migraine attack, the work of the gastrointestinal tract slows down. The taken pills remain in the stomach, and must be absorbed in the intestines. Caffeine increases gastrointestinal motility and helps painkillers be absorbed.

Caffeine also has a direct anti-migraine effect - therefore, it is part of various combined painkillers. But it is important to remember that these medications should not be overused, as excessive caffeine intake can make migraine attacks more frequent and severe [5].

Should I stop eating certain foods?

There is no scientific data that would confirm or disprove the effectiveness of "anti-migraine" diets. People with migraines usually notice which foods trigger their attacks and learn to avoid them. Foods that can trigger a migraine attack include red wine, beer, dark chocolate, hard cheeses, citrus fruits, nuts, foods containing preservatives, and fast food.

Hunger can also provoke a migraine. Therefore, it is important to eat regularly and in a balanced way (for example, following the Mediterranean diet). And it will be much more effective in preventing seizures than complex diets [4, 5].

References:

- Andress-Rothrock D., King W., Rothrock J. "An analysis of migraine triggers in a clinic-based population". // header. – 2010. – v.50. - 1366-1370.

- Chakravarty A. "How triggers trigger acute migraine attacks: a hypothesis". // Med Hypotheses. -2010. – v.74. – p.750-753

- Dodick D.W. Migraine triggers. // Headache. – 2009. – v.49. – p.958-961

- Martin P.R. Behavioral management of migraine headache triggers: learning to cope with triggers. // Curr Pain Headache Rep. – 2010. – v.14. p.221-227.

- Rothrock J.F. "The truth about triggers". // Headache. – 2008. – v.48. – p.499-500

Photo by alexey-turenkov_unsplash

Coffee can help with migraines and headaches

For some people, coffee is great for headaches. So why don't doctors recommend this method to everyone?

So why don't doctors recommend this method to everyone?

Anastasia Nikiforova

May help or harm

If an annoying headache makes you want to crawl to the coffee maker, then we have some pretty conflicting information for you. In short, coffee can help you, or it can hurt you. Want details? Let's tell!

Do you drink coffee when you have a headache?

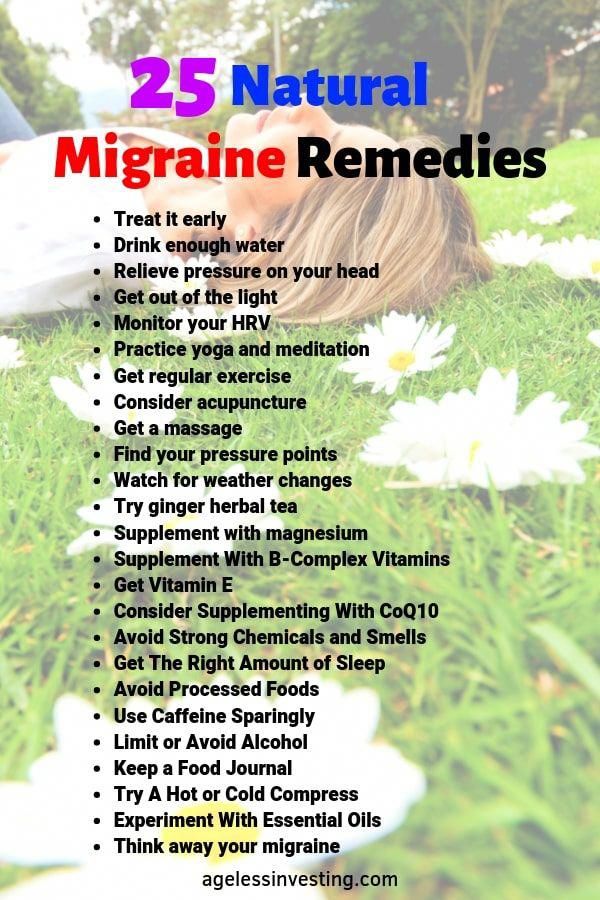

According to experts, caffeine can both relieve and aggravate a headache: the effect depends on many factors specific to you and your habits. So before you head out for a cup of coffee or a bottle of cola - caffeine, after all - there are some data to consider. Here's what you need to know.

Caffeine relieves headaches - in some cases

Caffeine, according to nutritionists and doctors, does not always help headaches. For pain caused by dilated blood vessels in the brain (a condition known as vasodilation), caffeine can help. It causes blood vessels to constrict, which reduces painful swelling.

It causes blood vessels to constrict, which reduces painful swelling.

Caffeine can also relieve tension headaches by relaxing spasmodic muscles in the neck or back of the head (a slightly paradoxical but real effect). And here lies the difficulty: an excessive amount of caffeine can make the muscles tighten and even overexert. And, characteristically, he will do it very quickly and without declaring war.

There is no magic dose. And specific too

It would be great if we knew exactly how many cups of coffee it takes to relieve a headache. We would also agree to the recommended dosage of pure caffeine in milligrams per kilogram of body weight, if only it could do something with a heavy head in the morning.

But this is unknown to science, alas. And we are unlikely to get more specific answers: caffeine affects people too differently.

Some people are genetically more sensitive to caffeine and should avoid coffee as a pain reliever. If after one cappuccino you're running around like an energizing bunny, maybe you should spare your tender receptors.

If after one cappuccino you're running around like an energizing bunny, maybe you should spare your tender receptors.

In any case, one or two cups is enough for everyone. In extreme cases - three or four, more definitely not worth it. After a certain amount of coffee, many people even begin to feel sleepy. But we do not recommend using it instead of sleeping pills, there will be problems with falling asleep or with the quality of sleep.

Source of caffeine matters

Coffee, tea, chocolate and soda are some of the most common sources of caffeine. Particular caution should be exercised in relation to energy drinks - doctors associate their use with dizziness, convulsions and even strokes, and at a very young age. If you are fond of energy drinks and suffer from headaches, it is better to quit - the neurostimulants contained in them only harm you.

For information, a regular cup of coffee contains 106 to 164 mg of caffeine, and a can of soda contains 38 to 46 mg. Sugar and other chemicals can make you feel bad, and the energy from a sweet fizz will pass faster than from a cup of flavored drink. .

Sugar and other chemicals can make you feel bad, and the energy from a sweet fizz will pass faster than from a cup of flavored drink. .

Very individual

Some people need ibuprofen and a half hour nap, others need a cold compress on their eyes for a few minutes. For someone - a massage of the cervical-collar zone (try it if you haven't tried it yet). And, of course, sometimes coffee will also flash among these methods. Different people are helped by different ways of dealing with headaches.

And if you suffer from headaches, a holistic approach can make all the difference. Sleep schedule adjustment, enough water, physical activity should come first in the fight for a clear mind.

Only then does it make sense to find out how caffeine affects you and whether you need other medications or stimulants. Lack of sleep, an unhealthy diet, and a sedentary lifestyle cause headaches more often than you might think.