Do not jump to conclusions

5 Ways to Stop Yourself From Jumping to Conclusions

Source: fizkes/Shutterstock

You see your partner walking through the door with a shopping bag that seems too small to hold what you asked for from the supermarket. Immediately, you accuse your partner of failing to follow through on this simple chore. As it turns out, though, you were the one who made the error. The bag actually does contain everything you requested, but it was so well-packed, it seemed inadequate for the job. Now you’ve got to apologize, but the lack of trust you created with your suspicion has caused a tiny dent in your relationship.

People jump to conclusions all the time, whether in romantic relationships or in ordinary, day-to-day interactions. You see a stranger apparently cutting in front of you on the sidewalk, and so you become instantly annoyed. A more careful look makes it clear that the person wasn’t being rude at all, but was just trying to hold the hand of her child, who was in danger of being lost in the crowd.

The subject line of an email from a friend of yours appears to be canceling the dinner you two were planning. You’re aggravated and a little bit hurt. However, after you open the email, you realize that he simply wanted to confirm. It’s a good thing you didn’t shut the email in disgust and not show up at the appointed time.

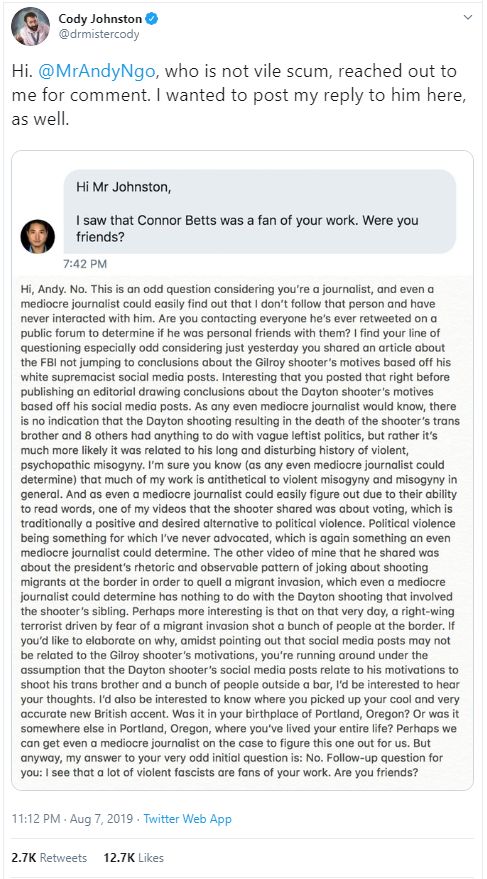

As it turns out, jumping to conclusions can not only interfere with your relationships but if it is a severe enough pattern, it can also be harmful to an individual’s mental health. You might be surprised to learn that the cognitive tendency of jumping to conclusions, abbreviated as “JTC,” is implicated in social anxiety and delusional disorders in what researchers call the “Threat Anticipation Model.” In new research by the University of East Anglia (UK)’s James Hurley and colleagues (2018), JTC interpretation bias is tested as a process that leads people to assume, wrongly, that a situation presents them with physical, social, or psychological harm. In other words, you’re confronted with an emotionally ambiguous situation and automatically conclude that the situation will come out badly for you because other people are out to hurt you. Putting this everyday tendency into a clinical context, then, you can see that if you perceive people who mean you no harm as having evil intent, your mental health (if not relationships) will be negatively impacted.

Putting this everyday tendency into a clinical context, then, you can see that if you perceive people who mean you no harm as having evil intent, your mental health (if not relationships) will be negatively impacted.

There is a standard test used to measure JTC, and it involves presenting you with a series of probabilistic choices to make (judging which of two jars a colored bead came from). People who score high on the JTC measure are ready to make their decisions about the bead's source before they actually have enough data to justify that decision. In the Hurley et al. study, eight men and four women (average age 39.4 years old) were drawn from a community mental health center and given training intended to reduce their JTC tendencies. Of the 12 participants, five had a diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia, three had a psychotic disorder, three had schizoaffective disorder, and one had delusional disorder. Their diagnoses were made approximately 10 years prior to the intervention, and 11 of the 12 individuals were taking antipsychotic medications. In addition to having these clinical diagnoses, the participants also had elevated scores on a measure of social anxiety. Their tendency to hold inflexible beliefs was also assessed, as this could contribute to JTC by priming individuals to make decisions consistent with their existing views.

In addition to having these clinical diagnoses, the participants also had elevated scores on a measure of social anxiety. Their tendency to hold inflexible beliefs was also assessed, as this could contribute to JTC by priming individuals to make decisions consistent with their existing views.

The specific training method focused on JTC indeed served to reduce the tendency to reach premature conclusions, as well as belief inflexibility in nine of the 12 participants. Paranoia was reduced in six of the 12, and one person’s social anxiety was alleviated by the training. An alternate cognitively focused training method was compared to the JTC-focused intervention, but it was not as effective in modifying JTC specifically. The JTC intervention, developed by King’s College London’s Helen Waller and colleagues (2011), is known as the “Maudsley Review Training Programme” (MRTP).

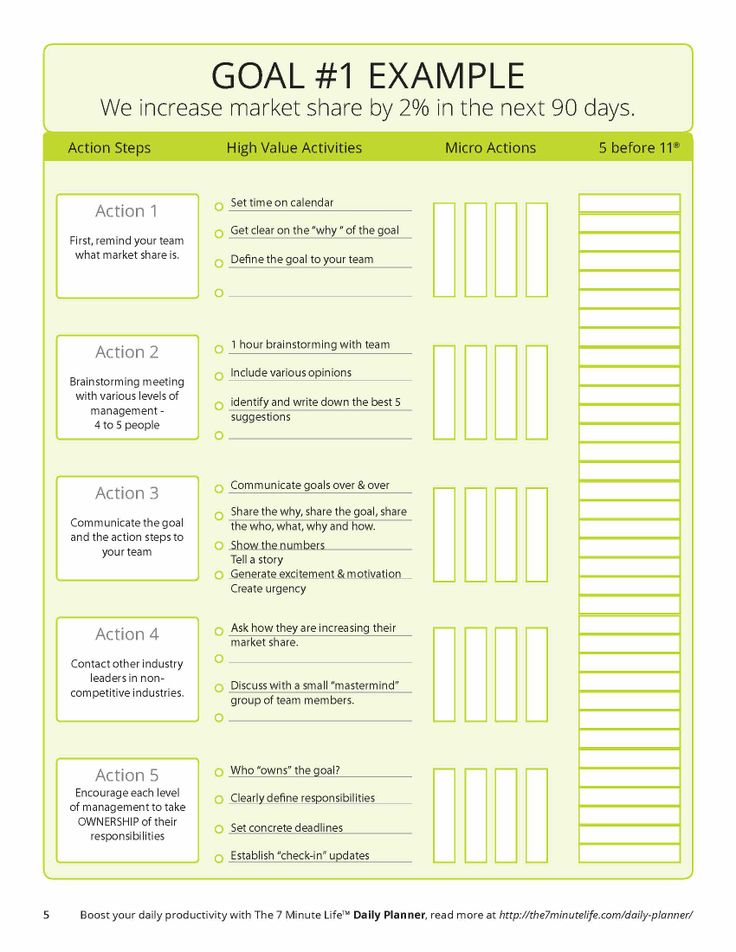

If this ingrained cognitive bias can be reduced in individuals with clinically diagnosed disorders, it stands to reason that the approach could also be beneficial to individuals who do not have these disorders but nevertheless approach their interactions with a negative bias. Looking now at the MRTP, see how you might benefit from this five-step method:

Looking now at the MRTP, see how you might benefit from this five-step method:

1. Think about times when you jumped to the wrong conclusions. Thinking your partner failed to follow through on your wishes or assuming a parent was being rude are just two instances that people can encounter during their daily lives. What about you? When was the last time you accused your partner of some flaw or failing that turned out to be an unfair criticism? When might you have turned right instead of left, because you didn’t read a sign carefully enough?

2. Test your ability to see the whole picture. In the MRTP, participants see part of a picture, one bit at a time (e.g., seeing the handle of a jug prior to seeing the rest of it). They had to guess what the entire picture represented. Participants were then instructed to look at more parts of the picture before deciding what it was.

3. See how easily you are fooled by illusions. Back in Introductory Psychology, you might have been given the “Mueller-Lyer” illusion in which you see two double-headed arrows. One set of arrows faces out and the other faces inward. The two lines are actually the same length, but you are fooled by the arrows into thinking the one with the outward-facing arrows is longer. If you rush to judgment, you’re more likely to be fooled by the illusion; by learning to take your time, you will be able to overcome this visual trick.

One set of arrows faces out and the other faces inward. The two lines are actually the same length, but you are fooled by the arrows into thinking the one with the outward-facing arrows is longer. If you rush to judgment, you’re more likely to be fooled by the illusion; by learning to take your time, you will be able to overcome this visual trick.

4. Ask yourself if you are too quick to form an impression of a person. In the training, participants see a picture of a person who is described as looking at them and staring. Through training, participants learn to change their immediate judgment (e.g., they’re being looked at critically) to consider other options (e.g., the person is actually watching a TV screen behind your head).

5. See how many times other people jump to conclusions in movies or television that depict the tendency in a humorous way. Remember the classic episode of Friends when Ross told Rachel they were on a “break”? It took years for this rift to be resolved, all due to mistaken suspicions that the characters had of each other. By watching other people suffer the negative consequences of jumping to conclusions, you can see the logical flaws that your own thinking might contain.

By watching other people suffer the negative consequences of jumping to conclusions, you can see the logical flaws that your own thinking might contain.

To sum up, solid relationships with others depend on solid evidence. Allow yourself to take the time and willingness to suspend judgment, and your relationships will be all the more fulfilling.

When People Decide Based on Insufficient Information – Effectiviology

Jumping to conclusions is a phenomenon where people reach a conclusion prematurely, on the basis of insufficient information. For example, a person jumping to conclusions might assume that someone they just met is angry at them, simply because that person wasn’t smiling at them while they talked, even though there are many alternative explanations for that behavior.

People jump to conclusions in many cases, and doing so can lead to a variety of issues. As such, in the following article you will learn more about the concept of jumping to conclusions, and see how you can avoid doing it yourself, as well as how you can deal with people who do it.

Contents

Examples of ways people jump to conclusions

The following are examples of common ways in which people jump to conclusions:

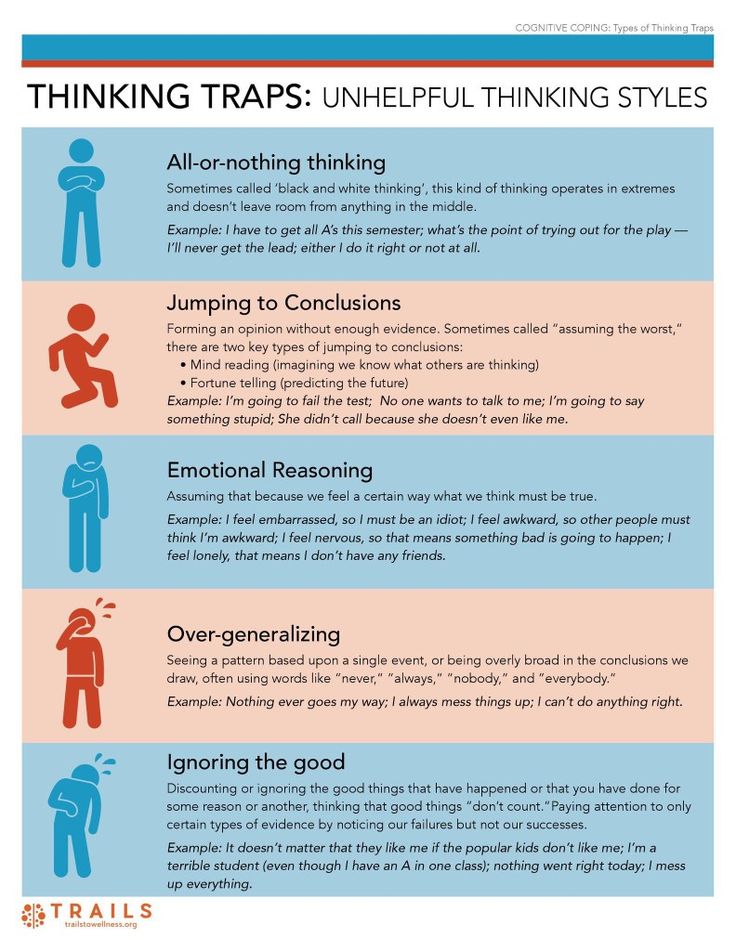

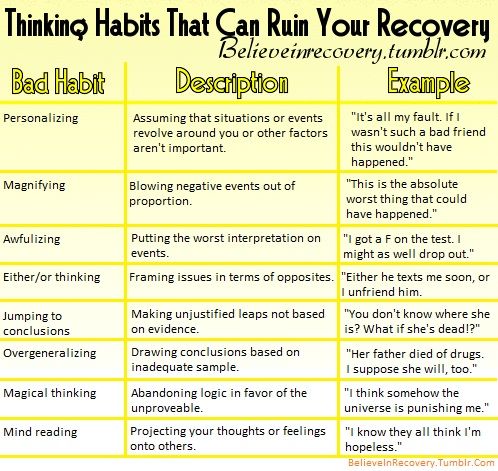

- Casual assumption. Casual assumption involves making a relatively minor, intuitive assumption, that is based on your preexisting knowledge, experience, and beliefs. For example, a casual assumption could involve seeing a restaurant whose windows are smudged, and immediately deciding that the food they serve must be bad.

- Inference-observation confusion. Inference-observation confusion involves mistaking something that you inferred using logic, for something that you observed. For example, inference-observation confusion could involve seeing someone driving a fancy car, and believing that we observed someone who is rich, when in practice we merely inferred that that person is rich based on their car, rather than observed it.

- Fortune telling. Fortune telling involves assuming that you know exactly what will happen in the future.

For example, fortune-telling could involve thinking that you’re going to fail a test, because you struggled with some of the practice questions.

For example, fortune-telling could involve thinking that you’re going to fail a test, because you struggled with some of the practice questions. - Mind reading. Mind reading involves assuming that you can accurately know what other people are thinking. For example, mind-reading could involve thinking that someone must hate you, simply because they didn’t seem enthusiastic when you told them “good morning”.

- Extreme extrapolation. Extreme extrapolation involves taking a minor detail or event and using it in order to conclude something relatively major. For example, extreme extrapolation could involve seeing some smoke come out of a house window, and immediately assuming that the house is on fire.

- Overgeneralization. Overgeneralization involves taking a piece of information that applies to specific cases and then applying it in other, more general cases, beyond what is reasonable. For example, overgeneralization could involve assuming that because you didn’t get along with one person from a certain social group, then you won’t get along with anyone else from that group either.

This is also referred to as hasty generalization or faulty generalization in some cases.

This is also referred to as hasty generalization or faulty generalization in some cases. - Labeling. Labeling involves making assumptions about people, based on behaviors or opinions that are stereotypically associated with a group that they belong to. For example, labeling could involve assuming that someone doesn’t like a certain hobby, simply because people of their gender don’t usually engage in it.

Note that there is sometimes overlap between these different forms of jumping to conclusions. Labeling, for example, can be viewed as a type of overgeneralization, and many forms of jumping to conclusions can be seen as types of casual assumptions.

Furthermore, keep in mind that the concept of jumping to conclusions isn’t limited to the forms described above, and people can also jump to conclusions in other ways.

Finally, note that while the concept of jumping to conclusions is most commonly associated with jumping to negative conclusions, people can jump to conclusions that are either positive, negative, or neutral in nature.

Why people jump to conclusions

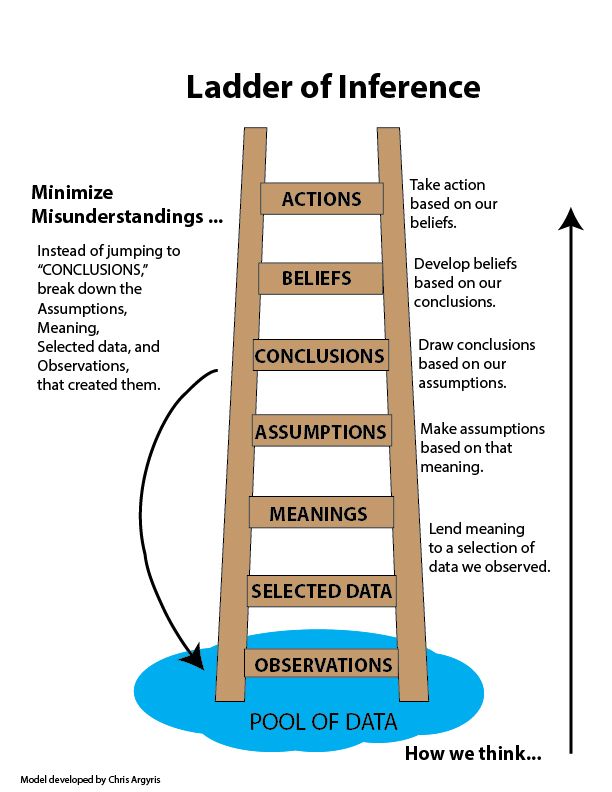

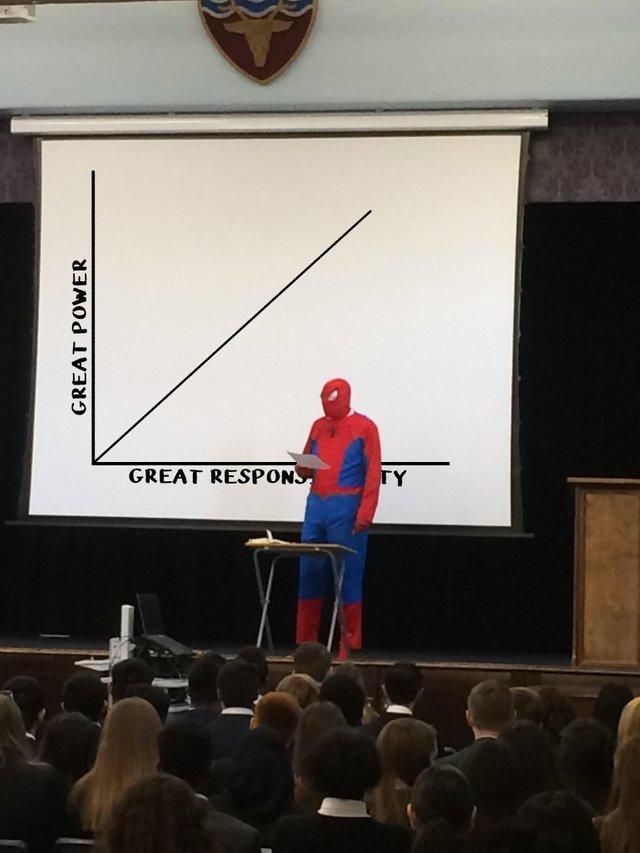

The main reason why people jump to conclusions is that our cognitive system relies on mental shortcuts (called heuristics), which increase the speed of our judgment and decision-making processes, at the cost of reducing their accuracy and optimality. In some cases, people misapply certain heuristics, which causes them to take mental shortcuts that are too extreme, in a way that leads them to jump to conclusions.

Below, you will learn more about this concept, and about the general psychology of jumping to conclusions.

Jumping to conclusions as a cognitive bias

The concept of jumping to conclusions is generally seen as a cognitive bias, in cases where people jump to conclusions as a result of the imperfect way in which our cognitive system works, which can cause us to rush ahead and make intuitive judgments, without relying on sufficient information and a thorough reasoning process.

In general, jumping to conclusions is a natural phenomenon, and can actually lead to reasonable results in many situations, such as when we need to reach a decision quickly. This is why we repeatedly jump to conclusions in minor ways throughout our day, particularly when it comes to making observations or decisions that aren’t very important.

This is why we repeatedly jump to conclusions in minor ways throughout our day, particularly when it comes to making observations or decisions that aren’t very important.

Jumping to conclusions in this manner involves the use of heuristics that allow us to assess situations and make decisions quickly, at the cost of increasing the likelihood that the outcome of our thought process will be sub-optimal. Usually, this speed-optimality tradeoff is worthwhile, especially if we only apply heuristics in proper situations and in a reasonable manner.

However, jumping to conclusions in this manner can become problematic when our heuristics are applied incorrectly, such as when they lead us to make a giant leap from a minor detail to a major conclusion, even though we have almost no evidence that supports our conclusion.

For example, jumping to conclusions is often a problem in medical fields, where practitioners frequently fail to properly validate an initial diagnosis or consider possible alternatives to that diagnosis (a phenomenon sometimes referred to in this context as premature closure).

Note: the tendency to jump to conclusions is associated with certain types of scientifically unfounded beliefs, such as belief in the paranormal and belief in witchcraft.

Factors affecting the tendency to jump to conclusions

Certain factors increase the likelihood that people will jump to conclusions.

For example, when people who hold some preexisting belief are presented with information relating to that belief, they are generally more likely to jump to conclusions and interpret that information as confirming their belief, compared to people who don’t hold the same belief.

Another factor that can affect the likelihood that people will jump to conclusions is the desire for closure and certainty. Such desire can mean that if someone has only partial information about something, they might jump to conclusions in order to achieve a sense of certainty, even if the conclusion that they reached is likely to be incorrect. However, it’s unclear whether or not this factor truly affects people’s reasoning on a large-scale, as research on the topic shows that there isn’t always a direct link between the need for closure and jumping to conclusions.

Overall, various factors could make people more or less likely to jump to conclusions. However, outside of a few main factors, such as the desire to confirm one’s preexisting beliefs, the exact role of such factors is difficult to predict, especially when it comes to individual cases.

Jumping to conclusions and mental disorders

People with certain mental disorders are sometimes prone to engage in jumping to conclusions, which can lead them to experience various delusions and paranoid thoughts. For example, a schizophrenic person might think that the government is spying on them, because they jump to conclusions after hearing their computer make a strange sound.

However, this does not mean that jumping to conclusions is necessarily indicative of a mental disorder, as people who have no disorders also display this type of reasoning, which is generally a serious problem only in extreme cases. Furthermore, there is some criticism of the research on the topic, which suggests that the relationship between these disorders and the jumping-to-conclusions bias is indirect, and could be explained, at least partially, by other factors, such as general cognitive abilities.

Jumping to conclusions as a logical fallacy

The concept of jumping to conclusions is generally viewed as a cognitive phenomenon, that causes people to jump to conclusions unintentionally. However, jumping to conclusions can also be seen as a logical fallacy in some cases, and specifically when people rely on arguments that involve jumping to conclusions, either intentionally or unintentionally.

People’s unintentional use of the jumping-to-conclusions fallacy is generally prompted by the jumping-to-conclusions bias. This means that the jumping-to-conclusions bias causes people to jump to conclusions when it comes to their internal reasoning process, which in turn causes them to use the jumping-to-conclusions fallacy in their arguments.

However, when it comes to the intentional use of the jumping-to-conclusions fallacy, it’s possible to present arguments that rely on this fallacy even when the person presenting the argument isn’t actually affected by the bias, and is fully aware that their argument is logically flawed. For example, consider the following statement:

For example, consider the following statement:

“We shouldn’t listen to him; he’s a politician, an politicians never care about the common people.”

This argument contains the jumping-to-conclusions fallacy, since it takes one fact (the person in question is a politician), and uses it in order to justify an unfounded conclusion (that we shouldn’t listen to the person in question), based on overgeneralization of the group that the person in question belongs to. The person using this fallacy could either be jumping to conclusions unintentionally, as a result of their own jumping-to-conclusions bias, or they might be doing so intentionally, because they believe that it will help them persuade the audience to support their stance.

However, keep in mind that both in this case and in general, jumping to conclusions doesn’t necessarily lead to a conclusion that is wrong. Rather, it leads to a conclusion that is insufficiently supported, since it’s based on insufficient information, which means that the process used to reach that conclusion is unsound, even if the conclusion itself is right.

Note: the jumping-to-conclusions fallacy is sometimes also referred to by other names, such as the hasty conclusion fallacy, and the where there’s smoke there’s a fire fallacy.

How to avoid jumping to conclusions

The main way to avoid jumping to conclusions is to ensure that you conduct a valid, evidence-based reasoning process, instead of relying on intuitive judgments that are based on insufficient information. There are various techniques that you can use in order to accomplish this, including the following:

- Slow down, and force yourself to think through a given situation instead of immediately accepting on your initial intuition as necessarily true.

- Actively ask yourself what information could help you reach a valid conclusion, and how you can get that information.

- Collect as much information as you can before forming an initial hypothesis.

- Come up with a number of plausible competing hypotheses.

- Avoid favoring a single hypothesis too early on.

- Actively try to justify the reasoning process that you’ve conducted so far, and identify any potential flaws in your reasoning.

- Question whether any observations that you made are actually inferences.

- Question all your premises, and ensure that they are well-founded.

- Actively ask yourself whether you might be rushing to form a conclusion too early.

- Actively ask yourself whether your chosen hypothesis is the one that makes the most sense, given the available evidence.

- Think about other times where you, or someone that you know, jumped to conclusions in a similar situation.

Furthermore, you can benefit from using various other debiasing techniques, that will allow you to think in a more rational manner and avoid jumping to conclusions; which techniques you should use will depend on your specific situation. For example, if your problem is that you jump to conclusions by assuming that you can tell what other people are thinking based on minimal evidence, then you will likely want to use debiasing techniques such as visualizing things from other people’s perspective.

Finally, note that in order to properly identify the nature of your jumping-to-conclusion problem, you should read through the information in this article, and especially through the part about the common ways in which people jump to conclusions. Doing so will improve your ability to understand how and why you jump to conclusions, which in turn will help you to choose debiasing techniques that are more effective in your particular case.

Note: a useful concept that can help you avoid jumping to conclusions in many situations is Hanlon’s razor, which suggests that when someone does something that leads to a negative outcome, you should avoid assuming that they acted out of an intentional desire to cause harm, as long as there is a different plausible explanation for their behavior.

How to respond to people who jump to conclusions

The main way to respond to someone who is jumping to conclusions is to point out the flaw in their reasoning, and specifically the fact that they have reached a conclusion prematurely, on the basis of insufficient information. You can achieve this in various ways, including by showing how little information they used to form their conclusion, pointing out what information they’re missing, and suggesting alternative conclusions that also make sense given what they know.

You can achieve this in various ways, including by showing how little information they used to form their conclusion, pointing out what information they’re missing, and suggesting alternative conclusions that also make sense given what they know.

However, keep in mind that there are some differences in how you should respond to someone who is displaying an unintentional jumping-to-conclusions bias, compared to how you should respond to someone who is intentionally using the jumping-to-conclusions fallacy for rhetorical purposes.

Specifically, when responding to someone who is jumping to conclusions unintentionally, your main goal is to help them internalize the issue with their reasoning. You can accomplish this using the same techniques that you would use to avoid jumping to conclusions yourself, with necessary modifications.

For example, consider a situation where a friend of yours assumes that someone hates them, simply because that person didn’t smile at them during a conversation. You could help your friend understand that they’re jumping to conclusions here, by helping them come up with alternative hypotheses that could explain this behavior.

You could help your friend understand that they’re jumping to conclusions here, by helping them come up with alternative hypotheses that could explain this behavior.

Conversely, when responding to someone who is jumping to conclusions intentionally, for rhetorical purposes, the main goal of your response should generally be to demonstrate the flaw in their logic. This means that you should focus on proving why the way that they reached a conclusion is flawed, by showing that there’s a problem with the premises of their argument, or by showing that their conclusion cannot be reasonably derived from those premises.

For example, consider a situation where your opponent in a debate jumps to conclusions, by claiming to know what you’re thinking based on what you’ve previously said on related topics, in an attempt to turn the audience against you. In this case, you could point out that your opponent’s version of your views is unfounded, and provide further evidence that demonstrates that the way they presented your stance isn’t in line with what you’ve previously said on the topic.

Finally, note that a technique that can be beneficial regardless of whether the person jumping to conclusions is doing so unintentionally or intentionally, is to ask them to fully justify their reasoning. When someone’s jumping to conclusions is unintentional, this can help them notice and internalize the flaws in their reasoning, and, when someone’s jumping to conclusions is intentional, this can help expose the flaws in their reasoning, and make their fallacious arguments harder to defend.

Summary and conclusions

- Jumping to conclusions is a phenomenon where people reach a conclusion prematurely, on the basis of insufficient information.

- People jump to conclusions in various ways, including by engaging in extreme extrapolation, overgeneralization, and labeling.

- People often display a jumping-to-conclusions bias as a result of the imperfect way in which our cognitive system works, which can cause us to rush ahead and rely on intuitive judgments, instead of using sufficient information and a proper reasoning process.

- You can reduce the degree to which you and others experience the jumping-to-conclusions bias by using various debiasing techniques, such as slowing down your reasoning process, collecting as much information as possible before forming an initial hypothesis, and coming up with a number of competing hypotheses for a given phenomenon.

- People sometimes the jumping-to-conclusions fallacy intentionally for rhetorical purposes; if you recognize that someone is doing this, you should focus on proving why the way that they reached a conclusion is flawed, by showing that there’s a problem with the premises of their argument, or by showing that their conclusion cannot be reasonably derived from those premises.

Never, never, never jump to conclusions. After all, everything may not be as you thought. — Discuss

Never, never, never jump to conclusions. After all, everything may not be as you thought. — DiscussFROM

Olya Toroptseva

Never, never, never jump to conclusions. After all, everything may not be as you thought. happening conclusion

After all, everything may not be as you thought. happening conclusion

1048

137

12

Answers

AR

Andrey Rachkov

fighter pilot operational speed: take 200 instrument readings per minute with your eyes and respond to them immediately. 60% of US Air Force losses in Vietnam were technically unable to control the aircraft. The sniper, of course, has a different task. Different professions, like different situations, require a person to display different qualities.

0

SO

Sergey Ovchinnikov

I agree, when they caught Chikotilo, they shot two innocent people who had served their time. But someone proved their guilt. Did they bear any responsibility?

But someone proved their guilt. Did they bear any responsibility?

0

JF

Jacobshavn Fhtagn

"it's not at all what you thought" begged his wife drunk and happy Nikolai, who had just arrived at midnight, timidly erasing lipstick around his mouth

0

Lyubov Selezneva

just about - many errors are from haste. for example, girls rush to marry the first person they meet for fear of remaining an old maid...

0

Akmal Zakirovich

You, like an angel incarnate:

Gentle, sweet, sincere.

In features - no flaw to be found,

My love, you are flawless.

0

Vadim Kozlov-Member of the Russian Federation. If you have any questions - Call 8 926 571 18 95

ALWAYS. for something, in any case, I will rush to make a decision! Sure! Everything will be as you thought!

0

Alexander Morozov

Precisely and before making any decision, listen to several opinions of opposing sides

0

Vladimir Tavkun

Olenka you are right in our life everything changes and something happens and we can meet you

0

Diamen

The thought is correct, only the form of the question is fussy-babtsova, which deprives the thought of goodness.

0

Today I'm Baking, Tomorrow I'm Brewing Beer, I'll Take the Child from the Queen...

- yes; I'm not in a hurry, I'm not in a hurry, but in the end, for some reason, everything is as usual..

0

EX

Elena Khalilova

A woman has a lot of fantasies and because of this a lot of stupid things are done

0

Sober

I was convinced more than once. As soon as I forget, I immediately get into trouble. Olenka - you are super

0

Anatoly Koshik

ASK your IDENTIFIER he will tell you I always consult with him

0

SG

Sergey Gavrilov

hurry up to live before you have time to look back, and life is behind you, what did you manage to do?

0

Sergey )))))

I think. ... a timely decision should not be a quick decision...

... a timely decision should not be a quick decision...

0

Igor Kovalchuk

Do not believe your eyes. Suspend everything 10 times. Then make a decision.

0

Dilshod'$

Write an answer...

Hello!

did the parameters change or what?

0

VM

Valery Mankov

Golden words. I say this to everyone, but still the smart ones are "what the hell!"...

0

Oltaviro

In reality, everything is not at all like it really is?

0

Ildus Rizvanov

in reality, everything is not at all like it really is

0

Next page

There will be no war with Russia? Do not rush to conclusions.

..

.. InoSMI materials contain only assessments of foreign media and do not reflect the position of the InoSMI editorial staff

Although Moscow now seems ready to talk about Ukraine, it is difficult to say whether its terms will be acceptable to the United States or what is more important - for Kyiv. Meanwhile, according to the commander of NATO forces, General Philip Breedlove, Russian troops can capture the south and east of Ukraine in three to five days. The stakes are extremely high, and against this background, it is time for us to reconsider some fundamental ideas about wars.

Paul J. Saunders

While Moscow now seems ready to talk about Ukraine, it's hard to say whether its terms will be acceptable to the United States or, more importantly, Kyiv. Meanwhile, according to the commander of NATO forces in Europe, General Philip Breedlove (Philip Breedlove), Russian troops could capture the south and east of Ukraine in three to five days. The stakes are extremely high, and against this background, it is time for us to reconsider some fundamental ideas about wars.

The 19th-century American humorist Josh Billings, a contemporary and rival of Mark Twain, wrote that "it's not lack of knowledge that gets you into trouble, but solid knowledge that simply doesn't correspond to reality." Unfortunately, after two decades of America being the only superpower, much of what our president, our politicians and our experts know about the war seems to fall into that category. Characteristically, when discussing how we should respond to the Russian annexation of Crimea, everyone in Washington unanimously says: America will not go to war with Russia. It is a pity, but this confidence is based on false premises - and this is very dangerous.

Many believe that the United States, with the world's largest military power, can decide for itself whether to fight or not. After two major wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, military operations in the Balkans and Libya, and the decision not to participate in the events in Syria, Americans have become accustomed to the idea that we can calmly discuss military measures while others are waiting for our decision, and have become convinced that no one is ready to challenge us. However, although Trotsky was wrong about almost everything, politicians should remember one of his phrases: "You may not be interested in the war, but then the war will be interested in you."

However, although Trotsky was wrong about almost everything, politicians should remember one of his phrases: "You may not be interested in the war, but then the war will be interested in you."

Is Russia prepared to directly attack US troops or other targets? Unlikely: the US military is much stronger than the Russian one, and Russian officials acknowledge this. However, while Russian President Vladimir Putin correctly judged that the United States would not fight in retaliation for his actions, that does not mean that his calculations will always be correct and that he will not one day go too far. In the end, a fair amount of what he is sure of is not true either.

This brings us to the second false premise, which assumes that we, Putin, the European Union, the new Ukrainian government and the Crimean leadership can jointly control what is happening. Meanwhile, it is completely refuted by the sad fate of the February 21 agreement between Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych and his opponents (they are also successors). Nothing came of this deal - the demonstrators on the Maidan demanded the immediate departure of Yanukovych. At the same time, the US, the EU and the top of the Ukrainian opposition were quite satisfied with the agreements, and Putin, together with the Crimean authorities, reluctantly put up with them. Yanukovych fled Kyiv and Ukraine out of fear of the mob, not of opposition leaders from the political elite.

Nothing came of this deal - the demonstrators on the Maidan demanded the immediate departure of Yanukovych. At the same time, the US, the EU and the top of the Ukrainian opposition were quite satisfied with the agreements, and Putin, together with the Crimean authorities, reluctantly put up with them. Yanukovych fled Kyiv and Ukraine out of fear of the mob, not of opposition leaders from the political elite.

The annexation of Crimea took place almost without violence. In the east and south of Ukraine, the situation has turned out to be more difficult and may continue to worsen. How long will the current relative calm last? If protests and demonstrations elsewhere lead to new outbreaks of violence, will Moscow intervene? What will NATO do if the weak Ukrainian army and volunteer detachments resist Russia? Where is the border between Eastern and Western Ukraine? Will the Russian General Staff be ready to stop the offensive on this conditional border and come to terms with the emergence in Western Ukraine of a hotbed of militants in the Pakistani spirit? Will Moscow dare to attack the arms shipments that many in America advocate for, or will it respond in a different way? Karl von Clausewitz once remarked that, once started, the war develops according to its own logic, each time bringing things to extremes. Unfortunately, we forget about it all the time.

Unfortunately, we forget about it all the time.

Many of us talk about "tough sanctions", suggesting that draconian economic measures could force Moscow to change course - or at least hit it hard - but not lead to armed conflict. This view is based on another false premise, that sanctions are an alternative to war, not a prelude to it. Iran, Iraq, North Korea, and a number of other countries have indeed endured sanctions without attempting to fight back with armed force, but none of these states is among the leading powers. The last time the United States imposed tough sanctions against such a power was at 1940-1941 by restricting trade with the Empire of Japan, culminating in a de facto oil embargo with a ban on the export of iron, steel, copper and other metals, as well as aviation fuel. Although President Franklin Delano Roosevelt feared that we would provoke Japan, the administration ultimately decided that Tokyo would understand how unwise it was to attack the United States. However, the Japanese leaders considered that it was more dangerous for them to yield to Washington. What decision would Putin make in a similar situation?

However, the Japanese leaders considered that it was more dangerous for them to yield to Washington. What decision would Putin make in a similar situation?

Some console themselves with the fact that between 1941 and 2014 there is one important difference - the nuclear arsenal of the United States and Russia. It is assumed that if nuclear deterrence prevented a direct confrontation between America and the Soviet Union during the Cold War, then it can again perform the same function. However, are Barack Obama and Vladimir Putin ready to use nuclear weapons? More importantly, does each of them believe that the other can use nuclear weapons in the event of a non-nuclear war over Ukraine? If at least one of the leaders believes that the opponent will definitely back down, the nuclear deterrence factor that prevents a non-nuclear war may not work. Similarly, this factor may not prevent the escalation of the conflict. As a matter of fact, Moscow has already started rattling its nuclear weapons.