Avoidant restrictive food intake disorder definition

Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) (for Parents)

What Is ARFID?

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) is an eating disorder. Children with ARFID are extremely picky eaters and have little interest in eating food. They eat a limited variety of preferred foods, which can lead to poor growth and poor nutrition.

ARFID usually starts at younger ages than other eating disorders. Unlike anorexia and bulimia, which are more common in girls, boys are more likely to have ARFID.

What Are the Signs of ARFID?

Picky eating and a general lack of interest in eating are the main features of ARFID. People with ARFID may not feel hungry or are turned off by the smell, taste, texture, or color of food. Some kids with ARFID are afraid of pain, choking, or vomiting when they eat.

Many kids with ARFID are underweight. But others are normal weight or overweight, especially if they eat only junk food.

Kids with ARFID are more likely to have:

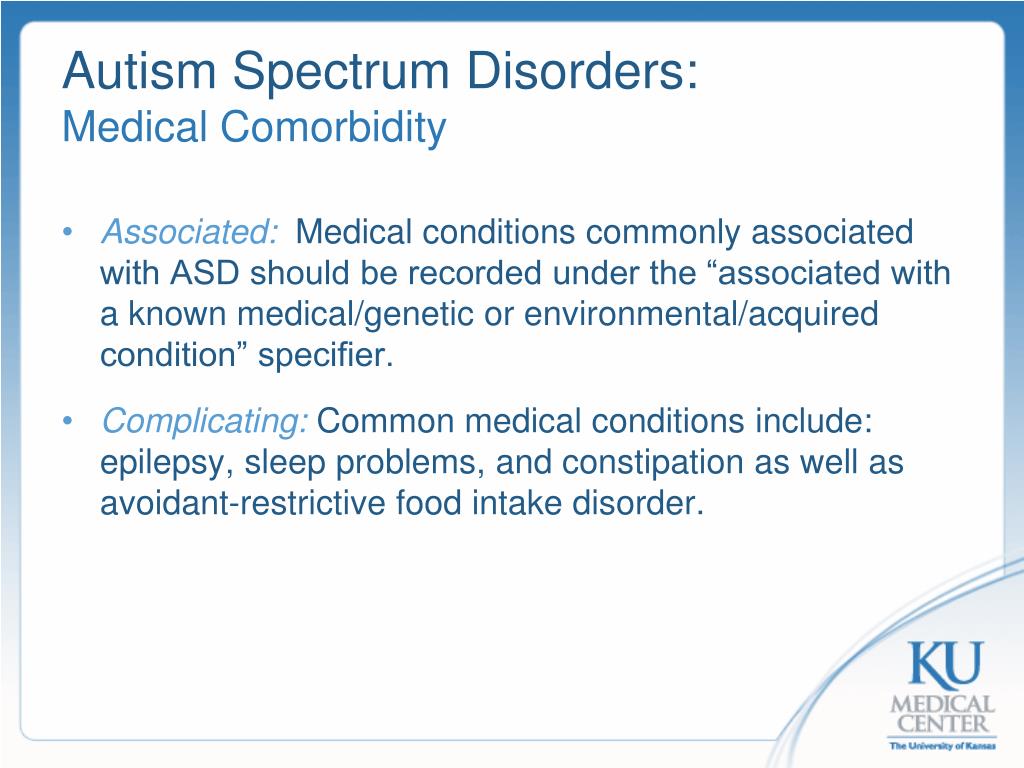

- anxiety or obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

- autism spectrum disorder or attention deficit disorder (ADHD)

- problems at home and school because of their eating habits

What Problems Can Happen with ARFID?

ARFID may lead to problems from poor nutrition. Kids with the disorder may:

- not get enough vitamins, minerals, and protein

- need tube feeding and nutrition supplements

- grow poorly

- have delayed puberty

- become overweight or obese

The lack of nutrition associated with ARFID can cause:

- dizziness and fainting due to low blood pressure

- a slow pulse

- dehydration

- weakened bones (osteoporosis) and muscles

- stopped menstrual periods (amenorrhea)

What Causes ARFID?

The exact cause of ARFID is not known. Many experts believe that a combination of psychological, genetic, and triggering events (such as choking) can lead to the condition. Some kids with ARFID have gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or other medical conditions that can lead to feeding problems.

How Is ARFID Diagnosed?

If a doctor thinks a child might have ARFID, they'll do an exam and ask about the child's medical history, eating and exercise habits, and emotional issues.

Doctors and mental health professionals will look for:

- significant weight loss

- serious nutritional deficiencies

- poor appetite, lack of interest in food, or food avoidance

Symptoms should not be because of a lack of access to food (food insecurity), another eating disorder (anorexia), or other medical problems.

Doctors may order blood tests, urine tests, or an electrocardiogram (ECG) to check for problems.

If you think your child may have ARFID, talk to your doctor. Dealing with the condition early on is the best way to successfully treat it.

How Is ARFID Treated?

ARFID is best treated by a team that includes a doctor, dietitian, and therapist who specialize in eating disorders. Treatment may include nutrition counseling, medical care, and feeding therapy. If choking is a concern, a speech-language pathologist can do a swallowing and feeding evaluation.

The main goals of treatment are to:

- Achieve and maintain a healthy weight and healthy eating patterns.

- Increase the variety of foods eaten.

- Learn ways to eat without fear of pain or choking.

Doctors might prescribe medicines to increase appetite or treat anxiety. If anxiety is a concern, the therapist will teach children and families ways to handle worries around food.

Most children with ARFID can be treated at home, but some will need to go to a more intensive hospital-based program. Someone with severe weight loss and malnutrition or serious health issues will need treatment in a hospital. Some children with ARFID will need tube feeding or nutrition formulas to get the calories and vitamins they need.

ARFID can be hard to overcome, but learning about healthy eating and addressing fears helps many kids and teens feel better and do well. When the whole family works together to change mealtime behaviors, a child is likely to have continued success.

How Can Parents Help?

ARFID is linked to strong emotions and worries around food. Be supportive and encourage positive attitudes about exercise and nutrition at home. Try these tips:

Be supportive and encourage positive attitudes about exercise and nutrition at home. Try these tips:

- Be a role model. Serve and eat a variety of foods.

- Schedule regular meals and snacks.

- Have regular family meals. Keep the mood at the table pleasant and avoid struggles during mealtimes.

- Encourage your child to try new foods, but do not force them to eat.

- Reward positive eating behaviors.

- Find ways to manage anxiety and stress around food. Taking a couple of deep breaths can help your child relax. Yoga, meditation, music, art, dance, writing, or talking to a friend can help manage stress.

If you are concerned your child may have an eating disorder, call your doctor for advice. The doctor can recommend nutrition and mental health professionals who have experience treating eating disorders in kids and teens. You also can find support and more information online at:

- The National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA)

Reviewed by: Colleen Sherman, PhD

Date reviewed: August 2021

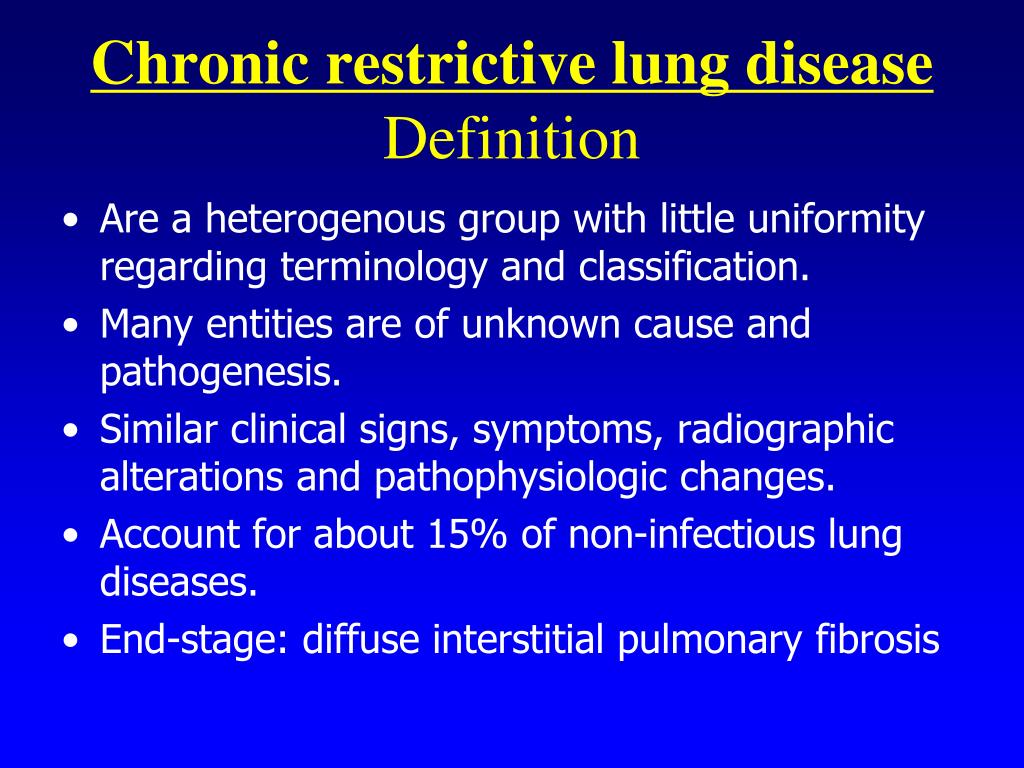

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID)

Any person, at any stage of their life, can experience an eating disorder. More than one million Australians are currently living with an eating disorder (1).

More than one million Australians are currently living with an eating disorder (1).

Of people with eating disorders, 3% have anorexia nervosa compared to 12% with bulimia nervosa, 47% with binge eating disorder and 38% with other eating disorders (1). Of people with anorexia nervosa, 80% are female (2).

Eating disorders are not a choice but are serious mental illnesses. Eating disorders can have significant impacts on all aspects of a person’s life – physical, emotional and social. The earlier an eating disorder is identified, and a person can access treatment, the greater the opportunity for recovery or improved quality of life.

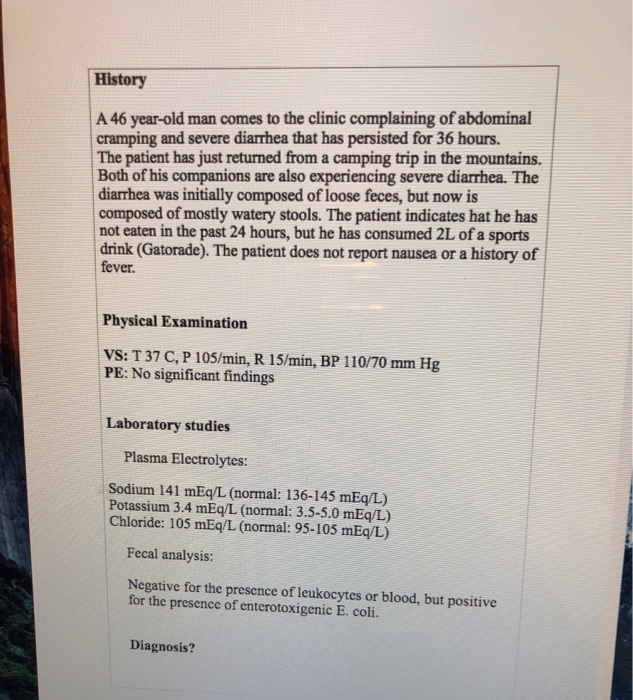

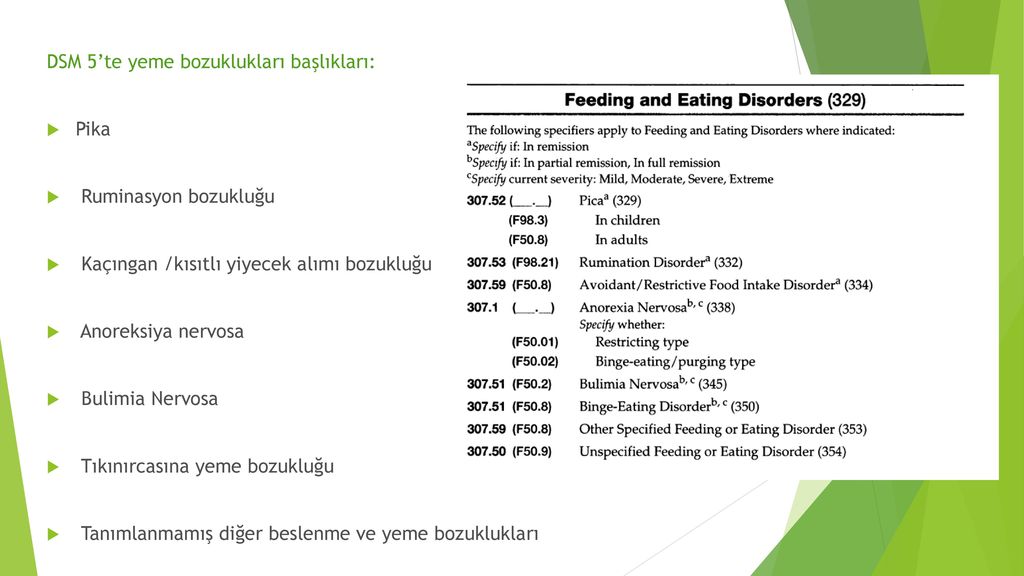

Figure 1. Prevalence of eating disorders by diagnosis

What is ARFID?

A person with ARFID will avoid and restrict food, however this is NOT due to body image disturbance.

ARFID is a serious eating disorder characterised by avoidance and aversion to food and eating. The restriction is NOT due to a body image disturbance, but a result of anxiety or phobia of food and/or eating, a heightened sensitivity to sensory aspects of food such as texture, taste or smell, or a lack of interest in food/eating secondary to low appetite (2).

ARFID is more commonly present in childhood and adolescence, however, it can occur in people of any age, gender, background, and sexual orientation (3). ARFID is predicted to occur in 1 in 300 people in Australia (4).

ARFID is more than just ‘picky eating’. People with ARFID may avoid or only eat small amounts of food, or limit variety of foods leading to nutritional deficiencies. Distinguishing ARFID from fussy eating can be difficult, however adults and children with ARFID generally experience an extreme aversion to certain foods or have a general lack of interest in food or eating. A person’s avoidance of food becomes concerning when it affects their ability to meet their energy and nutritional needs, resulting in weight loss, malnutrition or an inability to maintain growth and development.

Characteristics of ARFID

Eating disturbance

A person with ARFID will avoid food and/or restrict their intake due to one or more of the following reasons:

• Restriction: The person shows little or no interest in food and/or eating

• Avoidance: The person avoids certain foods based on sensory characteristics (e. g. texture, smell, sight, taste)

g. texture, smell, sight, taste)

• Aversion: The person has a fear or phobia of aversive consequences of e ating (e.g. vomiting, choking, allergic reaction)

Complications

The restricted intake of food is associated with one or more of the following:

• Significant weight loss or, in children, a failure to achieve expected weight gain or growth. However, a person with ARFID can present at any weight.

• Significant nutritional deficiency due to limited food variety or insufficient intake of nutrients required for the body to function.

• Dependence on feeding via tube through the mouth, stomach or intestines (also known as enteral feeding) to meet nutritional needs.

• Marked interference with psychosocial functioning as the eating problem can have a significant impact on day-to-day life. Due to difficulties in eating with others, only eating particular foods, or taking much longer to eat, functioning at school, work, and home can be challenging.

How is ARFID different to other eating disorders?

ARFID may look similar to anorexia nervosa in that some people with ARFID will severely restrict their food intake, resulting in inadequate energy consumption and similar medical consequences. Other people with an ARFID diagnosis may eat enough to maintain body weight but due to limited variety of foods suffer consequences of specific nutrient deficiencies. In direct contrast to people with anorexia nervosa, people with ARFID do NOT avoid food or restrict their intake due to a fear of gaining weight or concern over their body, weight, and shape.

A diagnosis of ARFID will NOT be made if another eating disorder (e.g. anorexia nervosa) better explains the symptoms. Similarly, a health professional will make sure that the eating disturbance is not caused by another medical condition or best explained by another mental disorder, and the weight loss or failure to grow is NOT secondary to physical disorders such as gastrointestinal issues.

Is there a link between ARFID and autism?

People with autism may have similar anxiety around eating certain foods as do people with ARFID. While there is some overlap between autism and ARFID (5), more research is needed to understand the relationship between the two.

Risk factors

The elements that contribute to the development of ARFID are complex, and involve a range of biological, psychological and sociocultural factors. Any person, at any stage of their life, is at risk of developing an eating disorder. An eating disorder is a mental illness, not a choice that someone has made.

Warning signs

• Delayed growth

• Weight loss

• In children, a failure to gain weight

• Reduced appetite

• Brittle nails, dry hair, hair loss

• Tiredness or lack of energy

• Other symptoms of micronutrient deficiencies

• Anxiety and/or distress around food and mealtimes

• Difficulty concentrating or learning

• Lack of interest in food and/or eating

• Refusal to eat or a reduction in foods previously eaten

• Slow eating

• Stating a fear of choking or eating certain foods

• Fear of vomiting of certain foods

• Difficulty eating meals with others

• Only eating a small number of foods. These foods may be similar in taste, texture, smell, or sight

These foods may be similar in taste, texture, smell, or sight

It is never advised to ‘watch and wait’. If you or someone you know may be experiencing an eating disorder, accessing support and treatment is important. Early intervention is key to improved health and quality of life outcomes.

Impacts and complications

A person with ARFID may experience serious medical and psychological consequences.

The restriction of food can result in a lack of essential nutrients and calories that the body needs to function normally. This could result in serious medical complications including:

• Heart problems

• Osteoporosis: a reduction in bone density caused by a specific nutritional deficiency

• Nutritional deficiencies including anaemia or iron deficiency, low vitamin A, low vitamin C

• Malnutrition characterised by fatigue, weakness, brittle nails, dry hair, hair loss, and difficulty concentrating, low energy

• Growth failure, failure to thrive, or stunted growth in children and adolescents

• Kidney and liver failure

• Electrolyte disturbances

• Low blood sugar

• Gastrointestinal problems

Some of the psychological impacts and complications associated with ARFID include:

• Anxiety

• Depression

• Social anxiety or social withdrawal

• Low self-esteem

Treatment options

ARFID is a relatively new diagnosis and the research is still growing around which treatments are effective. For all eating disorders, early intervention and treatment are likely to lead to better outcomes. The goals of treatment for ARFID will be determined by the underlying cause for the avoidance of food, for example, a phobia, an aversion to texture, or a lack of interest in food.

For all eating disorders, early intervention and treatment are likely to lead to better outcomes. The goals of treatment for ARFID will be determined by the underlying cause for the avoidance of food, for example, a phobia, an aversion to texture, or a lack of interest in food.

Current evidence suggests cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) is an effective treatment for people with ARFID (2). Treatment may involve gradually exposing the person to feared foods, relaxation training, and support to change eating behaviours.

Responsive feeding therapy (RFT) has also been used for the treatment of ARFID in children, however the guiding principles of RFT could also be applied for adolescents and adults (6). Responsive feeding involves parents or carers establishing mealtime routines with pleasant interactions and few distractions, modelling mealtime behaviour, and allowing the child to respond to hunger cues (6).

There are no medications for treating ARFID (2). If someone with ARFID also experiences anxiety or depression, there are some medications that can help with these symptoms. Your GP will help you to decide on the best treatment for you.

Your GP will help you to decide on the best treatment for you.

Some people with ARFID will need admission to hospital if the restriction causes severe medical complications, such as cardiac or gastrointestinal problems, or blood pressure or heart rate fluctuations. Treatment in hospital can ensure the person receives the nutritional intake they need for their body to function normally.

Most people can recover from an eating disorder with community-based treatment. In the community, the minimum treatment team includes a medical practitioner such as a GP and a mental health professional.

Recovery

It is possible to recover from ARFID, even if a person has been living with the illness for many years. The path to recovery can be long and challenging, however, with the right team and support, recovery is possible. Some people may find that recovery brings new understanding, insights and skills.

Getting help

If you think that you or someone you know may have ARFID, it is important to seek help immediately. The earlier you seek help the closer you are to recovery. Your GP is a good ‘first base’ to seek support and access eating disorder treatment.

The earlier you seek help the closer you are to recovery. Your GP is a good ‘first base’ to seek support and access eating disorder treatment.

To find help in your local area go to NEDC Support and Services.

Download the ARFID fact sheet here.

1. Deloitte Access Economics. Paying the price: the economic and social impact of eating disorders in Australia. Australia: Deloitte Access Economics, ; 2012.

2. Thomas JJ, Lawson EA, Micali N, Misra M, Deckersbach T, Eddy KT. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: a three-dimensional model of neurobiology with implications for etiology and treatment. Current psychiatry reports. 2017;19(8):1-9.

3. Norris ML, Spettigue WJ, Katzman DK. Update on eating disorders: current perspectives on avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in children and youth. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment. 2016;12:213.

4. Hay P, Mitchison D, Collado AEL, González-Chica DA, Stocks N, Touyz S. Burden and health-related quality of life of eating disorders, including Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID), in the Australian population. Journal of eating disorders. 2017;5(1):1-10.

Journal of eating disorders. 2017;5(1):1-10.

5. Dovey TM, Kumari V, Blissett J. Eating behaviour, behavioural problems and sensory profiles of children with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), autistic spectrum disorders or picky eating: Same or different? European Psychiatry. 2019;61:56-62.

6. Wong G, Rowel K. Understanding ARFID Part II: Responsive Feeding and Treatment Approaches National Eating Disorder Information Centre - Bulletin. 2018;33(4).

Avoidance/Restrictive Eating Disorder - Drink-Drink

Contents

- What are the symptoms of ARFID?

- What causes ARFID?

- How is ARFID diagnosed?

- How is ARFID treated?

- What are the prospects for children with ARFID?

What is avoidant/restrictive eating disorder (ARFID)?

Avoidant/restrictive eating disorder (ARFID) is an eating disorder characterized by eating very little or avoiding certain foods. This is a relatively new diagnosis that expands on a previous diagnostic category of eating disorders in infancy and early childhood that was rarely used or studied.

People with ARFID have developed some feeding or eating problems that cause them to avoid certain foods or consume food entirely. As a result, they cannot get enough calories or nutrients from their diet. This can lead to nutritional deficiencies, stunted growth, and problems with weight gain. In addition to health complications, people with ARFID may also experience difficulties at school or at work due to their condition. They may have trouble participating in social activities, such as eating with other people and maintaining relationships with other people.

ARFID usually presents in infancy or childhood and may persist into adulthood. At first, this may resemble the fussy eating habits of childhood. For example, many children refuse to eat vegetables or foods of a certain smell or texture. However, these finicky eating habits usually resolve within a few months without causing growth or development problems.

Your child may have ARFID if:

- the problem with eating is not caused by an eating disorder or other medical condition

- eating problem is not caused by lack of food or cultural eating habits

- eating problem is not caused by an eating disorder such as bulimia

- they do not follow the normal weight gain curve for their age last month

You can make an appointment with your child's doctor if your child shows signs of ARFID. Treatment is necessary to address both the medical and psychosocial aspects of the condition.

Treatment is necessary to address both the medical and psychosocial aspects of the condition.

If left untreated, ARFID can lead to serious long-term complications. It is important to make an accurate diagnosis right away. If your child is not eating enough but is at a normal weight for his age, you should still make an appointment with the doctor.

What are the symptoms of ARFID?

Many of the signs of ARFID are similar to other conditions that can cause your child to become malnourished. No matter how healthy you think your child is, you should contact your doctor if you notice that your child:

- seems underweight

- does not eat as often or as much as he should

- often seems irritable and cries often

- seems upset or withdrawn

- struggles to pass a bowel movement or seems to be in pain while doing so

- regularly appears tired and lethargic

- vomits frequently

- lacks age-appropriate social skills and tends to shun others

ARFID can sometimes be mild. Your child may not show many of the signs of malnutrition and may simply appear to be a picky eater. However, it is important to let your child's doctor know about your child's eating habits at their next checkup.

Your child may not show many of the signs of malnutrition and may simply appear to be a picky eater. However, it is important to let your child's doctor know about your child's eating habits at their next checkup.

Lack of certain foods and vitamins in your child's diet can lead to more severe vitamin deficiencies and other health problems. Your child's doctor may need to do a more detailed examination to determine the best way to make sure your child is getting all the important vitamins and nutrients.

What causes ARFID?

The exact cause of ARFID is unknown, but researchers have identified certain risk factors for this disorder. This includes:

- be male

- under 13 years of age

- have gastrointestinal symptoms such as heartburn and constipation

- have food allergies

Many cases of poor weight gain and malnutrition are associated with an underlying digestive disorder. However, in some cases, the symptoms cannot be explained by physical health problems. Possible non-medical reasons for your child's inadequate eating habits may include the following:

Possible non-medical reasons for your child's inadequate eating habits may include the following:

- Your child is afraid or stressed.

- Your child is afraid to eat because of a past traumatic incident such as choking or severe vomiting.

- Your child is not receiving adequate emotional response or care from a parent or primary caregiver. For example, the child may be frightened by the temper of the parents, or the parent may become depressed and withdraw from the child.

- Your child just doesn't like certain textures, tastes or smells.

How is ARFID diagnosed?

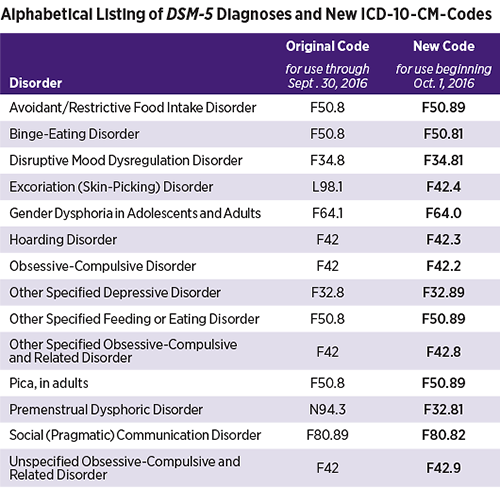

ARFID has been introduced as a new diagnostic category in the new edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). This guide is published by the American Psychiatric Association to help clinicians and mental health professionals diagnose mental disorders.

Your child may be diagnosed with ARFID if they meet the following DSM-5 diagnostic criteria:

- They have feeding or eating problems, such as avoiding certain foods or showing no interest in food at all.

- They have not gained weight for at least one month.

- They have lost a lot of weight in the last month.

- They depend on external food or supplements for their nutrition.

- They are nutritionally deficient.

- Their eating problems are not caused by an underlying illness or mental disorder.

- Their eating problems are not caused by cultural eating habits or lack of affordable food.

- Their eating problems are not caused by an existing eating disorder or poor body image.

Make an appointment with your child's doctor if your child has signs of ARFID. The doctor will weigh and measure your child, plot the numbers on a graph, and compare them to the national average. They may want to do more testing if your child weighs much less than most other children of the same age and gender. Testing may also be needed if there are sudden changes in your child's growth pattern.

If your doctor determines that your child is underweight or malnourished, they will perform various diagnostic tests to look for conditions that may be limiting your child's growth. These tests may include blood tests, urine tests, and imaging tests.

These tests may include blood tests, urine tests, and imaging tests.

If the doctor does not find an underlying condition, he will likely ask you about your child's eating habits, behavior and family environment. Based on this conversation, the doctor may refer you and your child to:

- dietitian for nutrition advice

- psychologist to study family relationships and possible triggers for any anxiety or sadness your child may be experiencing

- speech therapist or occupational therapist to determine if your child has oral or motor delays

If your child's condition is believed to be neglect, abuse, or poverty, a social worker or child protection officer may be assigned to work with you and your family.

How is ARFID treated?

Hospitalization may be required in an emergency. While there, your baby may need a feeding tube to get adequate nutrition.

In most cases, this type of eating disorder is treated before hospitalization is required. Nutritional counseling or regular meetings with a therapist can be very effective in helping your child overcome the disorder. Your child may need to follow a special diet and take prescribed supplements. This will help them achieve the recommended weight during treatment.

Nutritional counseling or regular meetings with a therapist can be very effective in helping your child overcome the disorder. Your child may need to follow a special diet and take prescribed supplements. This will help them achieve the recommended weight during treatment.

Once the vitamin and mineral deficiencies are corrected, your child may become more attentive and regular feeding may become easier.

What are the prospects for children with ARFID?

Because ARFID is still a new diagnosis, information about its development and outlook is limited. Generally, an eating disorder can be easily resolved by addressing it as soon as your child begins to show signs of persistent malnutrition.

If left untreated, an eating disorder can lead to physical and mental retardation, which can affect your child for life. For example, if certain foods are not included in your child's diet, oral motor development may be affected. This can lead to speech delays or long-term problems eating foods with a similar taste or texture. Treatment should be sought immediately to avoid complications. Talk to your doctor if you are concerned about your child's eating habits and suspect they have ARFID.

Treatment should be sought immediately to avoid complications. Talk to your doctor if you are concerned about your child's eating habits and suspect they have ARFID.

6 Common Types of Eating Disorders and Their Symptoms

Although the term "eating" is in the name, eating disorders are more than just food. These are complex mental illnesses that often require the intervention of medical and psychological experts to reverse their course.

These disorders are described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders of the American Psychiatric Association, Fifth Edition (DSM-5).).

In the United States alone, about 20 million women and 10 million men have suffered or had an eating disorder at some point in their lives.

This article describes the 6 most common types of eating disorders and their symptoms.

- What are they

- Causes

- anorexia

- Bulimia

- Compulsive overeating

- Peak

- Rumination

- Avoids

- Other

What are eating disorders?

Eating disorders are a range of psychological conditions that cause the development of unhealthy eating habits. They may begin with an obsession with food, body weight, or body shape.

They may begin with an obsession with food, body weight, or body shape.

In severe cases, eating disorders can cause serious health consequences and even death if left untreated.

People with eating disorders can have a variety of symptoms. However, most of them involve severe food restriction, overeating, or body cleansing such as vomiting or excessive exercise.

While eating disorders can affect people of either sex at any stage of life, they are most common in adolescents and young women. Up to 13% of young people may experience at least one eating disorder by age 20.

Summary: Eating disorders are mental health conditions marked by an obsession with food or body shape. They can affect anyone, but are most common among young women.

What causes eating disorders?

Experts believe that eating disorders can be caused by many factors.

One of them is genetics. Twin and adoption studies involving twins separated at birth and adopted by different families provide some evidence that eating disorders may be hereditary.

We offer you: 6 foods to help reduce anxiety

This type of study has generally shown that if one twin develops an eating disorder, the other twin has an average of 50% chance of developing an eating disorder.

Another reason is character traits. In particular, neuroticism, perfectionism, and impulsivity are three personality traits often associated with a higher risk of developing an eating disorder.

Other potential causes include perceived pressure to be thin, cultural preferences for thinness, and exposure to media promoting such ideals.

Some eating disorders seem to be virtually non-existent in cultures that have not embraced Western ideals of thinness.

However, culturally accepted ideals of thinness are widespread in many parts of the world. However, in some countries, few people develop an eating disorder. Thus, they are likely caused by a number of factors.

More recently, experts have suggested that differences in brain structure and biology may also play a role in the development of eating disorders.

In particular, levels of serotonin and dopamine, which transmit information to the brain, may be factors.

However, more research is needed before firm conclusions can be drawn.

Summary: Eating disorders can be caused by several factors. These include genetics, brain biology, personality traits, and cultural ideals.

1. Anorexia nervosa

Anorexia nervosa is probably the best known eating disorder.

Here are 8 foods and drinks to avoid with arthritis

Arthritis usually develops during adolescence or early adulthood and affects women more than men.

People with anorexia usually consider themselves overweight, even if they are significantly underweight. They tend to constantly monitor their weight, avoid eating certain foods, and severely restrict their calorie intake.

Symptoms of anorexia nervosa

Common symptoms of anorexia nervosa include:

- being significantly underweight compared to people of the same age and height

- a very restrictive diet

- intense fear of gaining weight or persistent behavior to avoid gaining weight despite being underweight

- relentless desire to lose weight and unwillingness to maintain a healthy weight

- strong influence of body weight or perceived body shape on self-esteem

- distorted body image, including denial of serious underweight

Obsessive-compulsive symptoms are also often present. For example, many people with anorexia often have constant thoughts about food, and some may obsessively collect recipes or hoard food.

For example, many people with anorexia often have constant thoughts about food, and some may obsessively collect recipes or hoard food.

Such people may also have difficulty eating in public places and have a strong desire to control their environment, which limits their ability to act spontaneously.

Anorexia is officially classified into two subtypes - the limiting type and overeating and the purging type.

Restrictive people lose weight solely through diet, fasting, or excessive exercise.

People with overeating and detoxification may overeat large amounts of food or eat very little. In both cases, after eating, they are cleansed using activities such as vomiting, taking laxatives or diuretics, or excessive exercise.

Anorexia can cause serious harm to the body. Over time, people living with the condition may experience thinning bones, infertility, brittle hair and nails, and fine hair growth all over the body.

We offer you: Calories in avocados: are they good for health?

In severe cases, anorexia can lead to heart, brain or multiple organ failure and death.

Summary: People with anorexia nervosa can limit their food intake or compensate for it with various cleanses. They have a strong fear of gaining weight, even if it is severely malnourished.

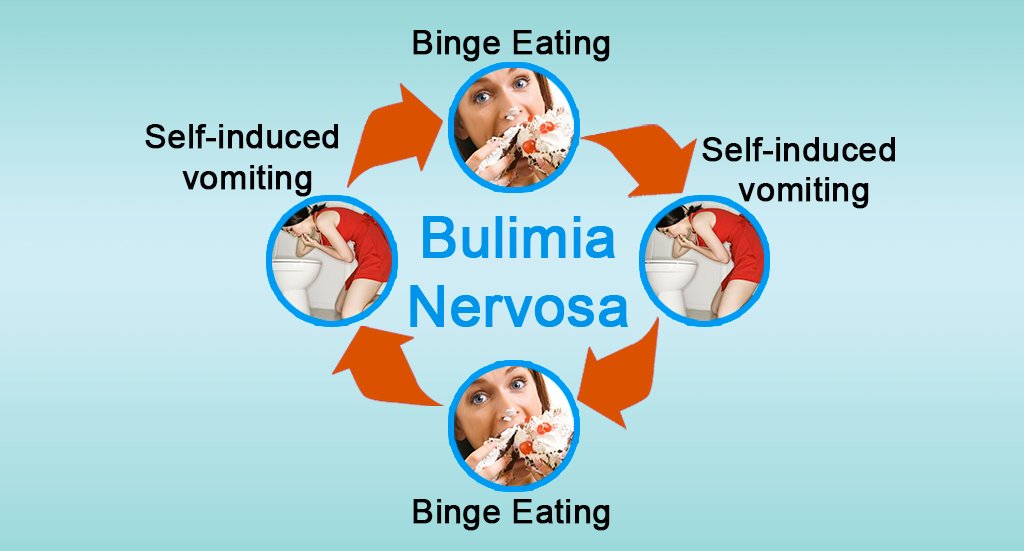

2. Bulimia nervosa

Bulimia nervosa is another known eating disorder.

Like anorexia, bulimia tends to develop during adolescence and early adulthood and appears to be less common in men than in women.

People with bulimia often eat unusually large amounts of food during a certain period.

Each episode of overeating usually continues until the person becomes painfully full. During overeating, a person usually feels that they cannot stop eating or control how much they eat.

Overeating can occur with any type of food, but most often occurs with foods that a person would normally avoid.

People with bulimia then try to cleanse the body to compensate for the calories consumed and relieve intestinal discomfort.

Common cleansing methods include forced vomiting, fasting, laxatives, diuretics, enemas, and excessive exercise.

Symptoms can be very similar to those of binge eating or the purging subtype of anorexia nervosa. However, people with bulimia usually maintain a relatively normal weight rather than losing weight.

Symptoms of bulimia nervosa

General symptoms of bulimia nervosa include:

- recurrent episodes of binge eating with a sense of loss of control

- repetitive episodes of inappropriate purging behavior to prevent weight gain

- self-esteem is overly dependent on body shape and weight

- 900, despite normal weight

Side effects of bulimia can include inflammation and sore throat, swollen salivary glands, worn tooth enamel, tooth decay, acid reflux, intestinal irritation, severe dehydration, and hormonal imbalances.

In severe cases, bulimia can also cause imbalances in electrolyte levels such as sodium, potassium and calcium. This can cause a stroke or heart attack.

This can cause a stroke or heart attack.

Summary: people with bulimia nervosa eat large amounts of food in short periods of time and then purge. Fear of gaining weight despite normal weight.

3. Compulsive overeating.

Binge eating disorder is considered one of the most common eating disorders, especially in the United States.

We offer you: 17 evidence-based benefits of omega-3 fatty acids

It usually starts in adolescence and early adulthood, although it can develop later.

People with this disorder have symptoms similar to those of bulimia or the binge eating subtype of anorexia.

For example, they usually eat unusually large amounts of food in relatively short periods of time and feel a lack of control when overeating.

People with binge eating disorder do not limit their calorie intake and do not use cleansing methods such as vomiting or excessive exercise to compensate for their overeating.

Symptoms of binge eating

Common symptoms of binge eating include:

- eating large amounts of food quickly, in secret, and to the point of being unpleasantly full, despite not feeling hungry

- feeling out of control during binge episodes

- feelings of distress, such as shame, disgust or guilt when thinking about overeating

- not using cleansing habits such as calorie restriction, vomiting, excessive exercise, or using laxatives or diuretics to compensate for overeating

People with Compulsive overeating is often overweight or obese. This can increase the risk of medical complications associated with being overweight, such as heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes.

Summary: People with binge eating regularly and uncontrollably consume large amounts of food in short periods of time. Unlike people with other eating disorders, they don't cleanse.

4. Pika

Pika is another eating disorder associated with eating something that is not considered food.

People suffering from pica need inedible substances such as ice, dirt, soil, chalk, soap, paper, hair, cloth, wool, pebbles, washing powder or cornstarch.

We offer you: 10 signs and symptoms of hypothyroidism

Peak can occur in adults, as well as in children and adolescents. However, this disorder is most commonly seen in children, pregnant women, and those with psychiatric disorders.

People with pica may be at increased risk of poisoning, infections, intestinal injury, and nutritional deficiencies. Depending on the substances ingested, pica can be fatal.

However, to be considered pica, the consumption of non-food substances must not be a normal part of one's culture or religion. Also, peers should not view it as a socially acceptable practice.

Summary: People with pica tend to consume non-food substances. This disorder can particularly affect children, pregnant women, and people with mental disorders.

5. Chewing disorder.

Rumination disorder is another recently discovered eating disorder.

It describes the condition in which a person regurgitates food that he has previously chewed and swallowed, chews it, and then either re-swallows it or spit it out.

This rumination usually occurs within the first 30 minutes after a meal. Unlike diseases such as reflux, this is voluntary.

This disorder may develop in infancy, childhood, or adulthood. In infants, it tends to develop between 3 and 12 months of age and often goes away on its own. Children and adults with this condition usually need therapy to manage it.

If not resolved in infants, rumination disorder can lead to weight loss and severe malnutrition, which can be fatal.

Adults with this disorder may limit the amount of food they eat, especially in public places. This can lead to weight loss and weight loss.

Summary: Rumination disorder can affect people at all stages of life.

People with this condition usually regurgitate recently swallowed food. They then chew it again and either swallow it or spit it out.

6. Food avoidance/restriction disorder.

Food avoidance/restriction disorder is a new name for an old disorder.

We offer you: Brown vs white rice: better for your health?

This term replaces what was known as "feeding disorder in infancy and early childhood", a diagnosis previously given to children under 7 years of age.

Although avoidance/restrictive eating disorder usually develops in infancy or early childhood, it may persist into adulthood. Moreover, it is equally common among men and women.

People with this disorder experience eating disorders, either due to a lack of interest in food or an aversion to certain smells, tastes, colors, textures, or temperatures.

Symptoms of food avoidance/restriction

General symptoms of food avoidance/restriction disorder include:

- food avoidance or restriction that prevents the person from eating enough calories or nutrients

- eating habits that interfere with normal social functions eg eating with others

- weight loss or poor development for age and height

- nutritional deficiency or dependence on supplements or tube feeding

It is important to note that avoidance/restrictive eating disorder goes beyond normal behaviors such as picky eating in toddlers or reduced food intake in older adults.

Furthermore, this does not include refusing or restricting the consumption of food due to lack of availability or due to religious or cultural practices.

Summary: Food avoidance/restriction disorder is an eating disorder that causes people to become malnourished. This is either due to a lack of interest in food or a strong aversion to the smell or taste of certain foods.

Other common eating disorders

In addition to the six eating disorders listed above, there are also lesser known or less common eating disorders. They usually fall into one of three categories:

- Purification disorder. People with a purging disorder often use purging methods such as vomiting, laxatives, diuretics, or excessive exercise to control their weight or shape. However, they do not drink.

- Night eating syndrome. People with this syndrome often eat excessively, often after awakening from sleep.

- Other specified feeding or eating disorder (OSFED). Although not listed in the DSM-5, this includes any other conditions that have symptoms similar to those of an eating disorder but do not fit into any of the above categories.

One disorder that may currently be covered by OSFED is orthorexia. Although orthorexia has been increasingly mentioned in the media and in scientific research, the current DSM has not yet recognized it as a distinct eating disorder.

We offer you: Polyphenol Foods List: Best Polyphenol Foods

People with orthorexia tend to be obsessively focused on healthy eating to the point where it disrupts their daily lives.

For example, the victim may exclude entire food groups for fear that they are unhealthy. This can lead to malnutrition, severe weight loss, difficulty eating out, and emotional distress.

People with orthorexia rarely focus on losing weight. Instead, their self-worth, identity, or satisfaction depends on how well they adhere to the dietary rules they set.