Differential diagnosis for ptsd

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Making the Diagnosis

ABSTRACT: Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is an anxiety disorder that can develop after a traumatic event is witnessed or experienced. It commonly involves actual or threatened death, serious injury, or threat to a person’s physical integrity, combined with feelings of intense fear, helplessness, or horror. Traumatic events that may cause PTSD include violent personal assaults, natural or man-made disasters, (i.e., terrorist attacks, motor vehicle accidents, rape, physical and sexual abuse, and other crimes), or military combat. Patients with PTSD continue to exhibit symptoms of anxiety, hypervigilance, sleep difficulties, anger, and irritability, in addition to psychological numbness and interpersonal, social, educational, and vocational dysfunctions. They also remember and often relive the traumatic events. The purpose of this article is to introduce primary care clinicians to the history, epidemiology, biological causes, and psychosocial complications of PTSD to review the diagnostic evaluation and the biopsychosocial and spiritual interventions that have been used in treatment.

Although it was not given a formal name, the psychiatric diagnosis that is now known as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has been recognized through the centuries by several other monikers including shell shock, battle fatigue, soldier heart, accident neurosis, as well as concentration camp or post-rape syndrome. Exposure to traumatic events has been a part of the human condition since the creation of Adam and Eve1 and symptoms of PTSD have been documented in the lives of heroes and heroines throughout history and literature—examples include Trojan War characters Agamemnon and Achilles in the Odyssey, and Shakespeare's Henry IV and Lady Macbeth.2

Researchers and clinicians first got involved in studying the plight and sufferings of Vietnam War veterans and set their goal to create a single diagnostic entity to include multiple psychiatric symptoms. As a result, PTSD was formally recognized as a diagnosis in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III), published in 1980. 3

3

PTSD was originally only referenced as a consequence to a catastrophic traumatic event that was considered outside the range of usual human experience—such as war, torture, rape, manmade disasters (i.e., the Holocaust, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center), natural disasters (i.e., earthquakes, hurricanes, flooding and volcano eruptions), and everyday incidents (i.e., factory explosions, airplane crashes and automobile accidents).4

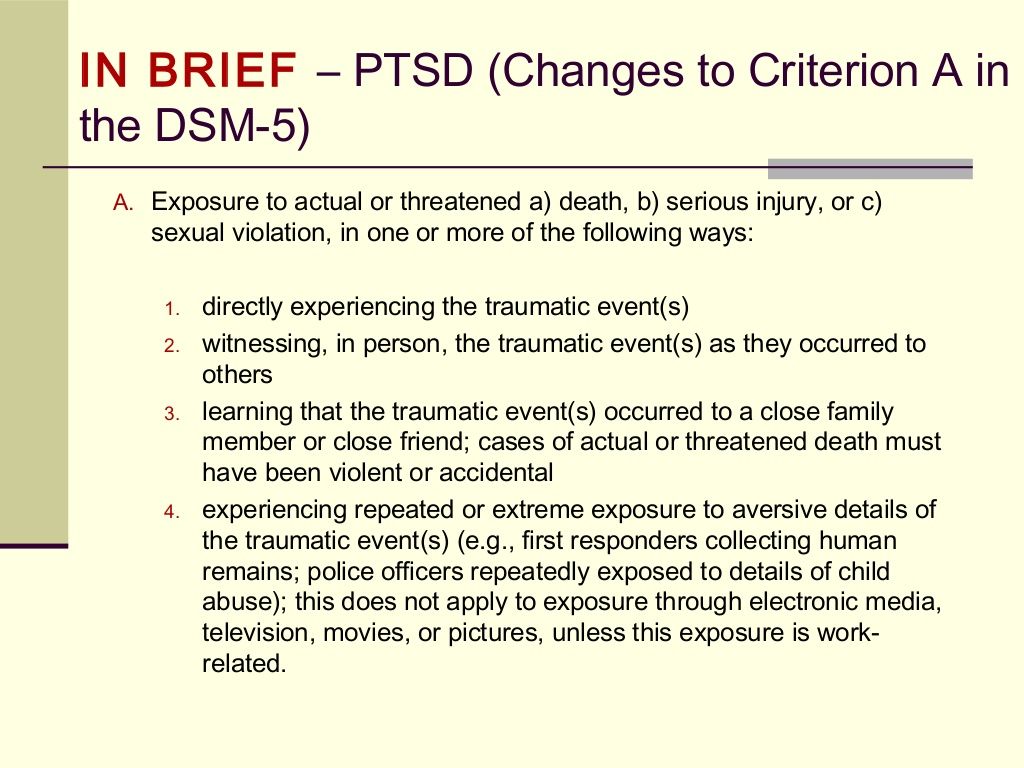

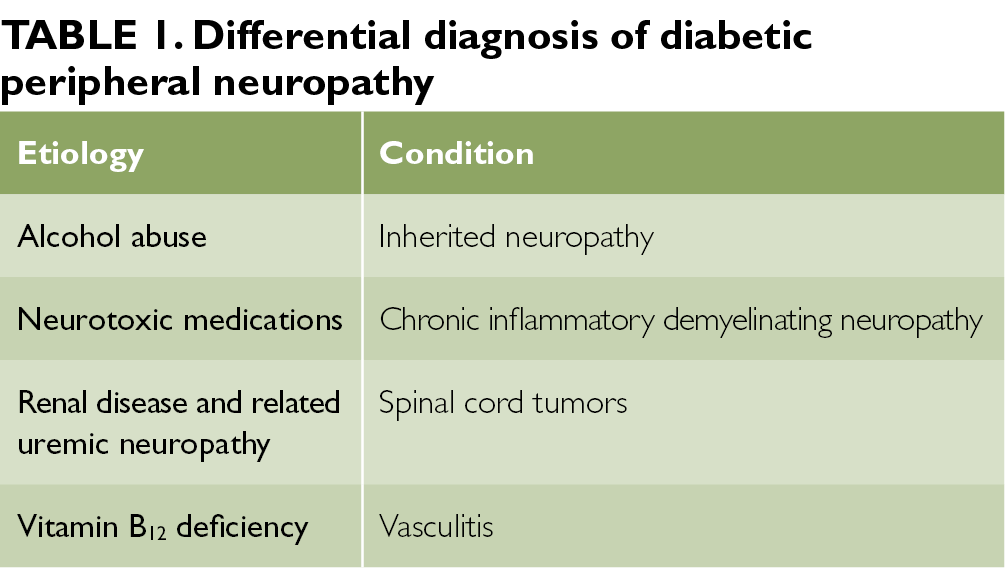

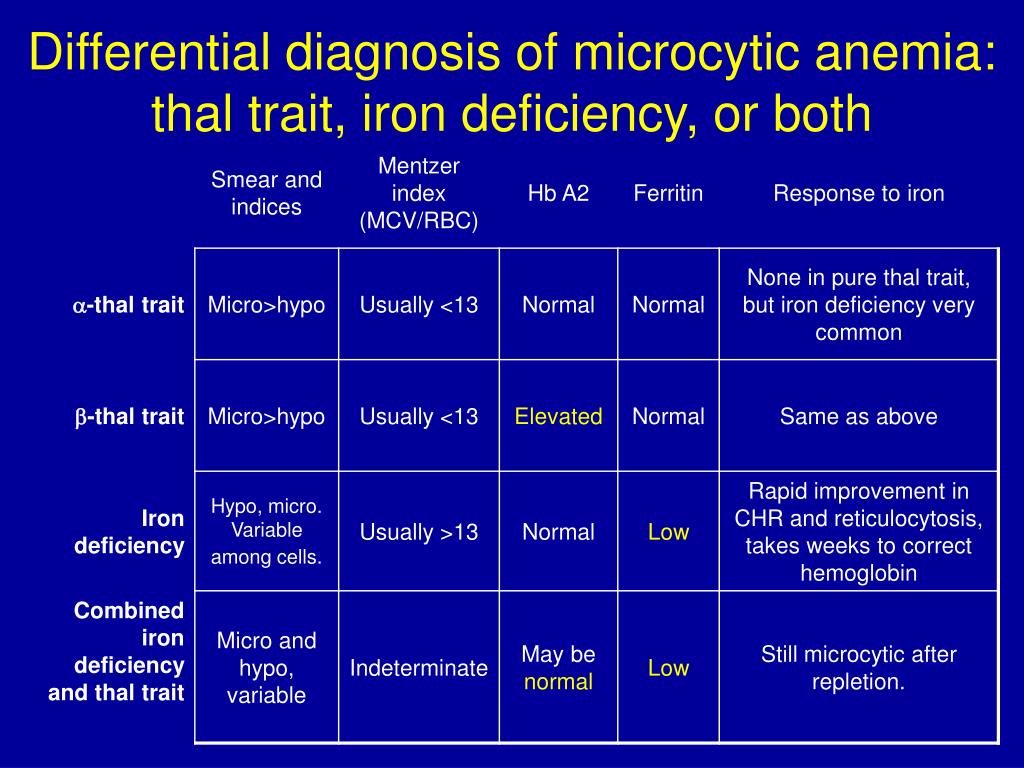

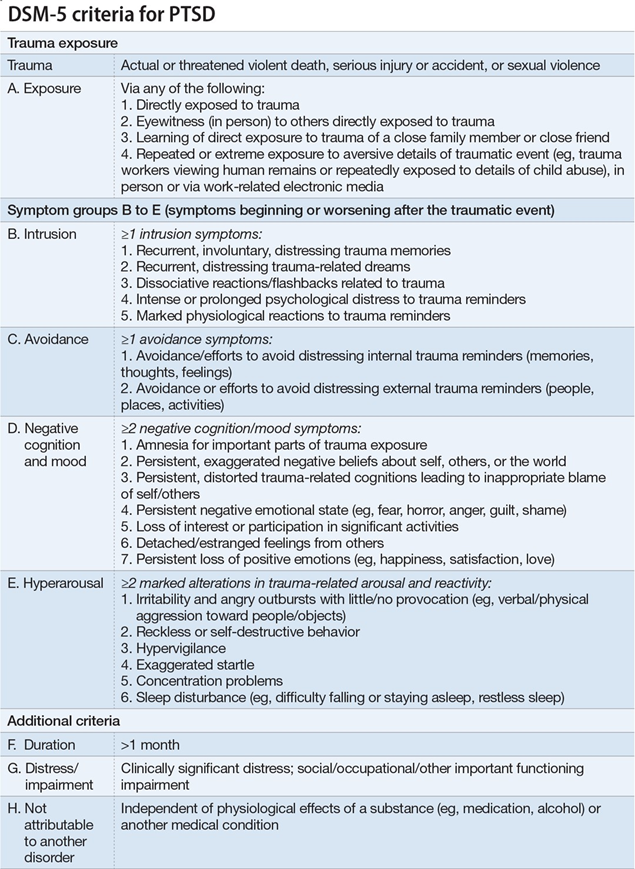

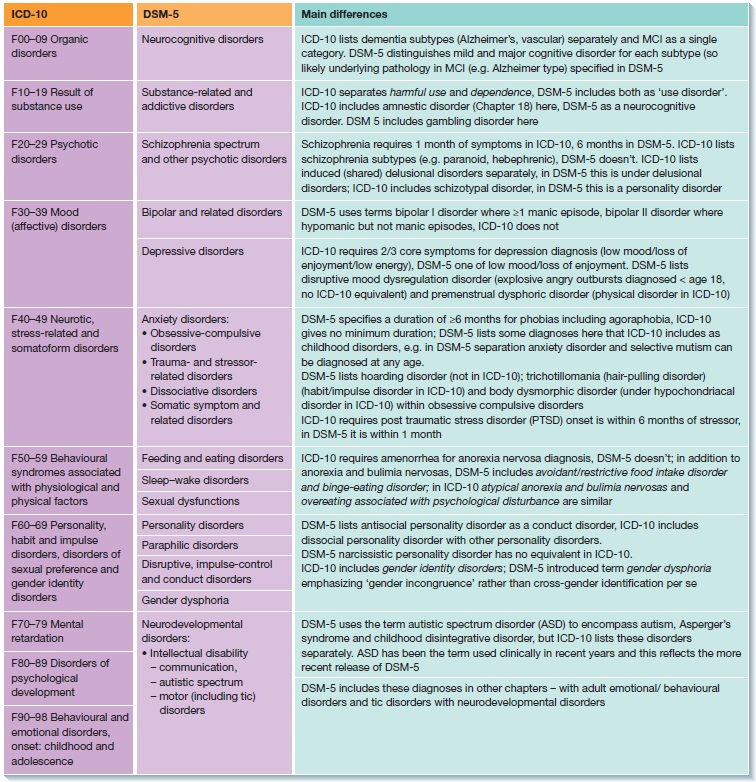

Over time, the PTSD diagnosis has been revised (Table 1) to include exposure to trauma as a necessary element.5 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), published in May of 2013, reclassified PTSD from an anxiety disorder into a new class of "trauma and stressor-related disorders."5As such, a diagnosis of PTSD now requires exposure to a traumatic or stressful event—a decision made based on the clinical recognition of variable expressions of distress as a result of traumatic experience.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The lifetime prevalence of PTSD among adults in the US is estimated to be 6.8%.6,7 Furthermore, the lifetime prevalence in men is 3.6% vs. 9.7% in women; the 12-month prevalence is 1.8% in men vs. 5.2% in women.8 The 6-month prevalence of PTSD is estimated to be 3.7% in boys vs. 6.3% in girls, and is associated with high rates of truancy, vandalism, alcohol use, and running away, especially if it occurs before the age of 15.8

Looking at worldwide estimates, lifetime PTSD prevalence ranges from 0.3% in China to 6.1% in New Zealand.9 However, it is important to note that countries may use differing methodological approaches to collect their data and statistics.9

The estimated lifetime prevalence of PTSD among Vietnam War veterans was calculated at 30.9% for men vs. 26.9% for women.10 PTSD is estimated in 10.1% of Gulf War veterans.11 Among Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan and Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans, PTSD prevalence is 13. 8%.12

8%.12

It is estimated that 80% of patient with PTSD will have co-occurring medical and/or psychiatric disorder.13,14 PTSD is more common among individuals with low socioeconomic status and, particularly in those living in areas in which violence is endemic.9,15 PTSD is more common in women than in men,8,15 and affects people of all ages (younger and elderly persons are the most vulnerable).13-15 Adults who are exposed to psychological trauma are at the highest risk to develop PTSD.15

CAUSES OF PTSD

PTSD is caused by experiencing, witnessing, or being confronted with an event that involves serious injury, death, or threat to the physical integrity of an individual, along with an emotional response of helplessness and/or intense fear or horror.5 The interaction between a person's biological vulnerability based on genetic (inherited) contributions, psychological characteristics, social or environmental factors, and the exposure to traumatic events could lead or prevent the development of PTSD. 12-14

12-14

Biological disturbances. The main biological disturbances in PTSD seems to result from a dysgulation in the naturally occurring stress hormones and an increased sensitivity in the brain anxiety circuits.16 In addition, patients with PTSD were found to have hypersensitivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA)16,17 and have increased activation in the brain anatomical fear centers—the amygdala, hypothalamus, locus ceruleus, periaqueductal gray, and parabrachial nucleus.18 Another precursor to PTSD, kindling was first described in patients who experienced seizures, where a sub-threshold electrical or chemical brain stimulation eventually lead to a full-blown seizure and subsequent chronic stimulation led to spontaneous seizures.19

Traumas that are followed by intrusive thoughts or the reliving of events might kindle the limbic nuclei, which leads to the manifestation of core PTSD symptoms—hypervigilance, avoidance, and increase startling reactions. 20 It is still unknown whether these biological changes were present before the traumatic event and predisposed the person to develop PTSD or whether these changes were the result of the PTSD.15-17

20 It is still unknown whether these biological changes were present before the traumatic event and predisposed the person to develop PTSD or whether these changes were the result of the PTSD.15-17

Personal and psychosocial factors. The interaction between various identified psychosocial and environmental factors with personal characteristics can increase an individual’s vulnerability to develop PTSD. These factors include:

• Characteristics of the trauma itself. The trauma’s proximity and severity, as well as the duration of an individual’s exposure to the trauma, should be considered. Examples of severe traumatic events that could lead to PTSD include terrifying violent attacks, war, assault, rape, torture, kidnapping, child abuse, serious accidents, and natural or man-made disasters (Table 2).2

• Characteristics of the individual. These include prior exposure to trauma, family history, childhood adverse events like parental separation and preexisting psychiatric conditions, especially substance abuse, anxiety, or depression. 22 There is also evidence of gender specificity; combat exposure, childhood neglect, physical abuse, and molestation are commonly associated with PTSD in men, while women are at a greater risk for PTSD after violent traumatic events (i.e., rape, threat with a weapon, molestation, and physical abuse).22 Clinical observations have consistently shown a correlation between the development of PTSD in adults who were traumatized as children and an association between early trauma exposure and subsequent retraumatization.23The internal and external PTSD vulnerability characteristics are summarized in Table 3.24

22 There is also evidence of gender specificity; combat exposure, childhood neglect, physical abuse, and molestation are commonly associated with PTSD in men, while women are at a greater risk for PTSD after violent traumatic events (i.e., rape, threat with a weapon, molestation, and physical abuse).22 Clinical observations have consistently shown a correlation between the development of PTSD in adults who were traumatized as children and an association between early trauma exposure and subsequent retraumatization.23The internal and external PTSD vulnerability characteristics are summarized in Table 3.24

• Posttraumatic factors. These include the early emergence of avoidance or numbing, hyperarousal, and re-experiencing symptoms. An accurate PTSD prognosis could significantly improve with the development of posttraumatic growth and resilience (Table 4). Religious and spiritual beliefs, hopefulness, optimistic attitudes, insight, taking initiative, humor, creativity, and independence have all shown to be important factors in enhancing resilience. 25,26 The traumatic event is perceived as an opportunity to turn adversity into an opportunity to achieve higher life goals.24-26

25,26 The traumatic event is perceived as an opportunity to turn adversity into an opportunity to achieve higher life goals.24-26

COMPLICATIONS WITH PTSD

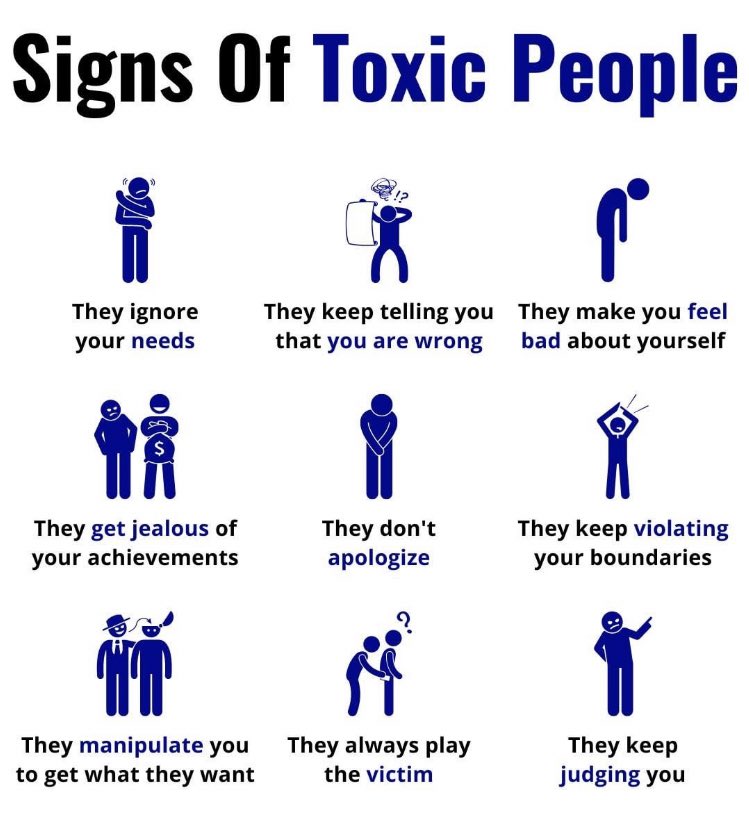

Significant disruption of relationships, high unemployment, divorce, and substance abuse are common complications that may result from irritability, isolation, anger, impulsive behaviors, and compromised coping skills.4,12 Patients with PTSD are also at increased risk for the presence of co-occurring psychiatric disorders—such as generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, panic disorder, panic attacks, agoraphobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, and somatization disorder.13

Patients with PTSD and any of these disorders may be at a particularly high risk for suicide.12,13 In addition, PTSD patients who are victims of physical and or sexual assault are at high risk for developing mental health complications, homicide, and suicide. 27 Studies have shown an association between PTSD and the risk of developing dementia among older US male veterans.28 PTSD has also been linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.29

27 Studies have shown an association between PTSD and the risk of developing dementia among older US male veterans.28 PTSD has also been linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.29

ASSESSMENT AND EVALUATION

Although the exception to the rule, some patients with PTSD may display altered behavior, agitation, and extreme startle reactions. They may be confused and disoriented. Memory lapse may be observed, though it could be trauma-specific or more widespread.30 Patients have been observed to have poor concentration, lack of impulse control, and altered speech.31

Mood and affect may change depending on the type and timing of the questions; feelings of anxiety, guilt, and/or fear may be predominant even in the absence of depression. Thoughts and perception may also be altered despite the absence of florid psychosis. Patients may express suicidal or homicidal ideations without a specific plan to act on them, particularly around certain anniversary dates related to the traumatic events. 30,31

30,31

To make a diagnosis, primary care providers first need to obtain the relevant history of traumatic stress exposure and posttraumatic stress symptoms to evaluate patients for other psychiatric disorders, including PTSD. 4,13,30,31 The DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria (Table 5), and the corresponding mnemonic “TRAUMA” (Table 6), can both serve as guides.5

In addition, there are several important associated features to evaluate:

• Impaired affect modulation and/or self-destructive and impulsive behavior.

• Dissociative symptoms.

• Depression and/or feelings of ineffectiveness, shame, despair, and hopelessness.

• Obsession with being "permanently damaged," or under constant "threat."

• Loss of religious and/or spiritual beliefs.

• Hostility, anger, and violence.

• Personality change, social withdrawal and/or social impairment.

• Interpersonal problems or relationship conflicts.

• Somatic and sexual dysfunction.

• Survivor guilt and preoccupation with sins of omission and/or sins of commission.

• Addiction.

Finally, the Short Screening Scale (Table 7)32 can easily be administered in a primary care setting.

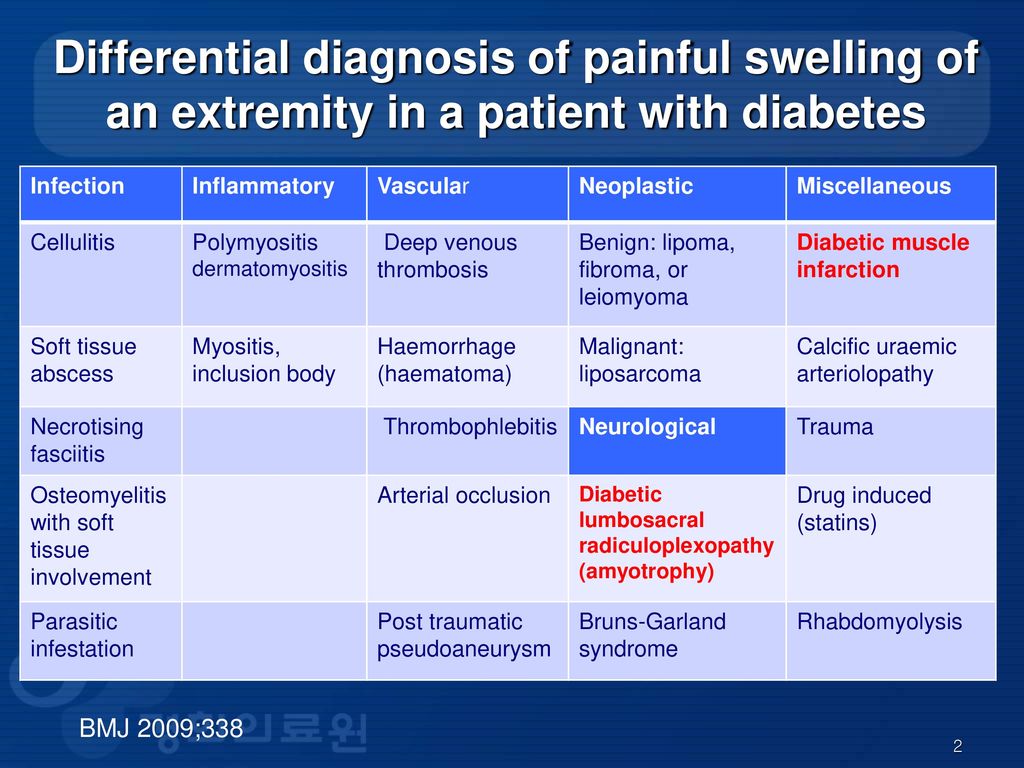

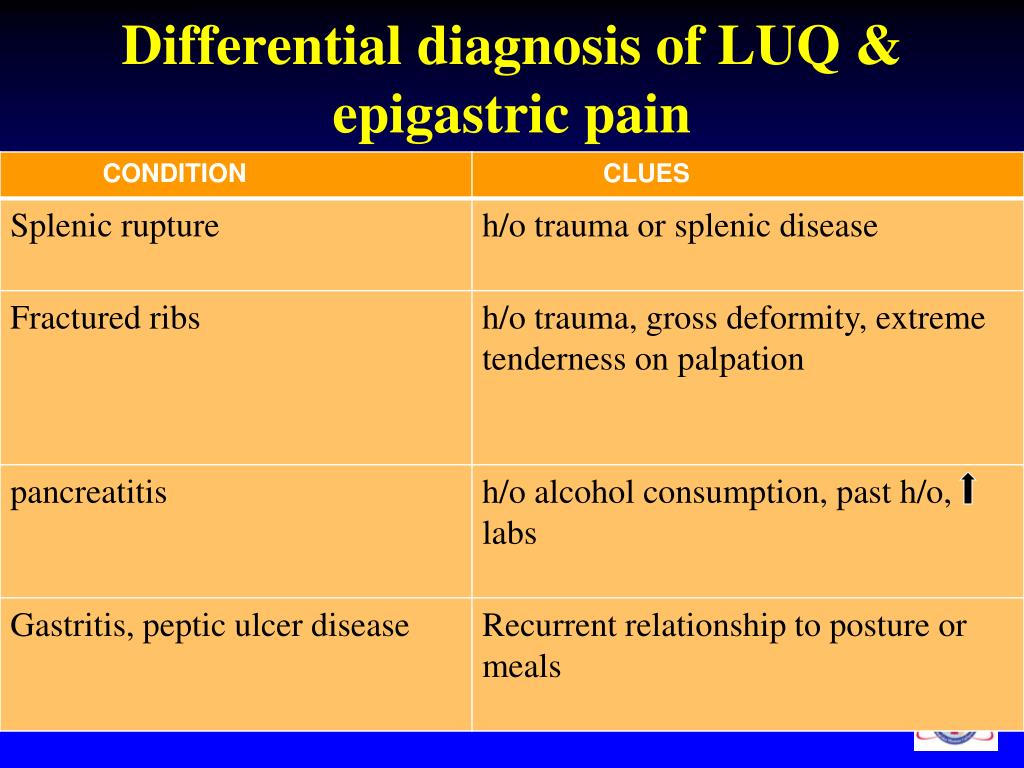

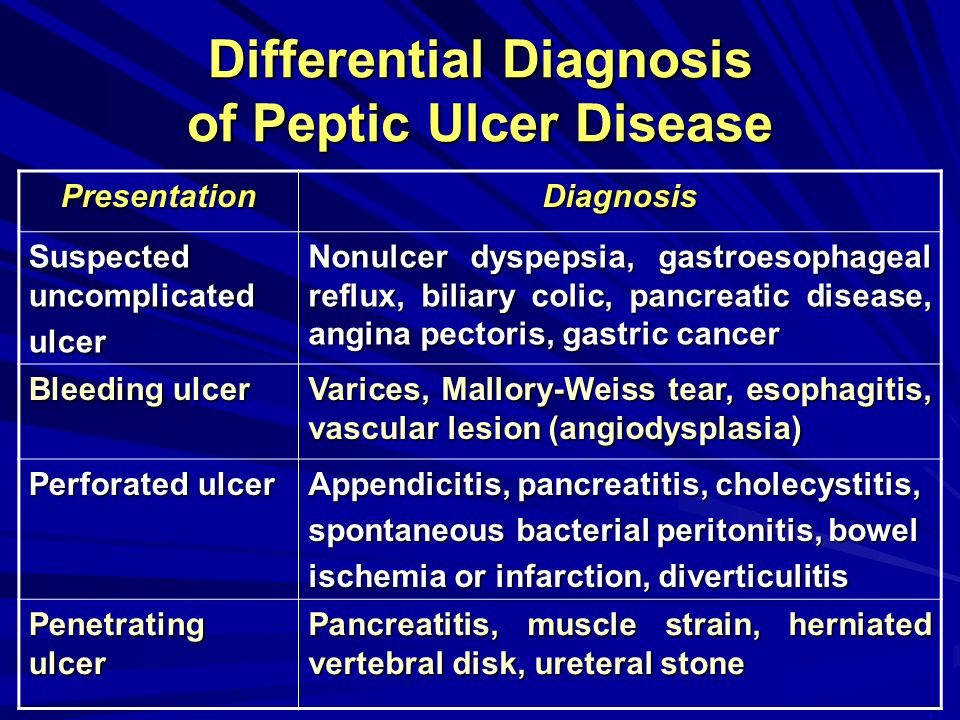

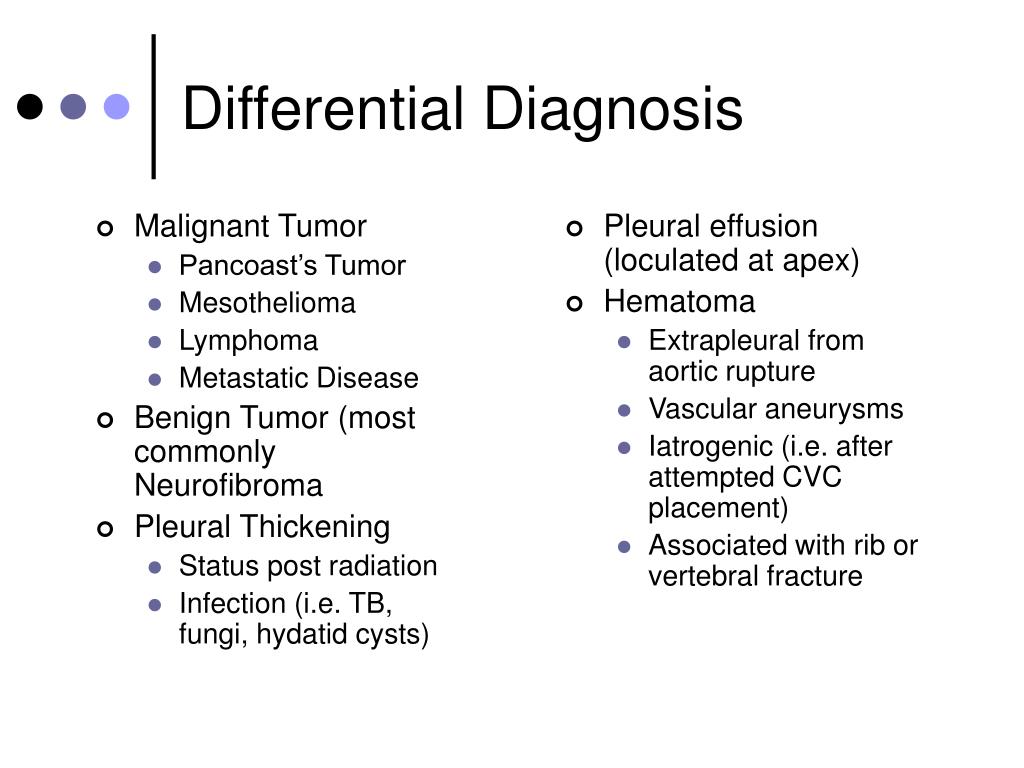

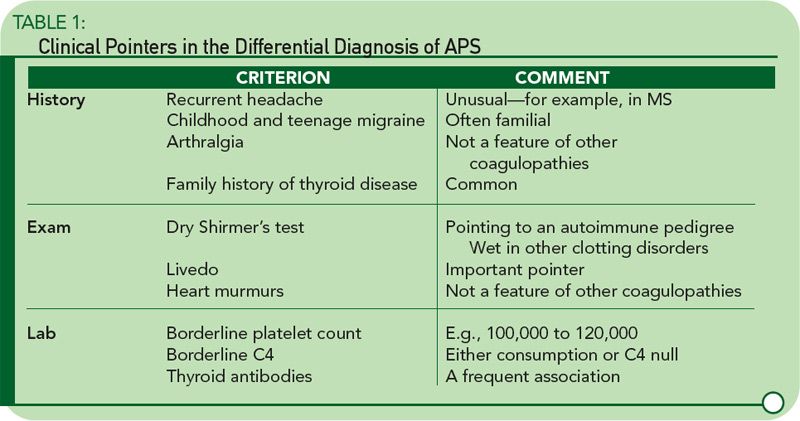

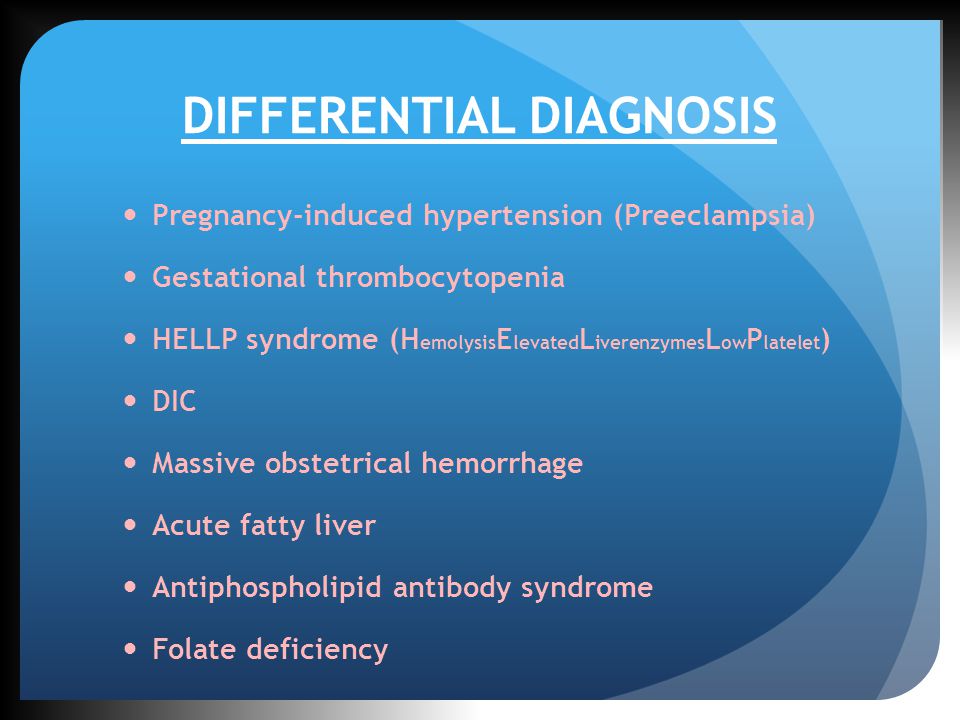

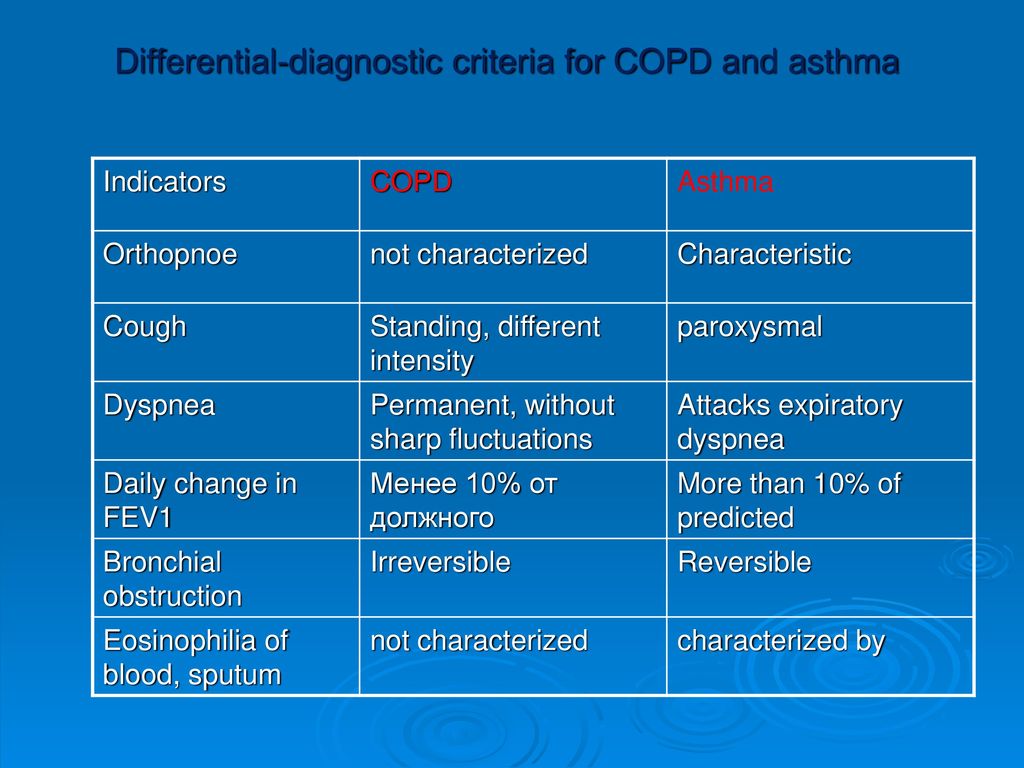

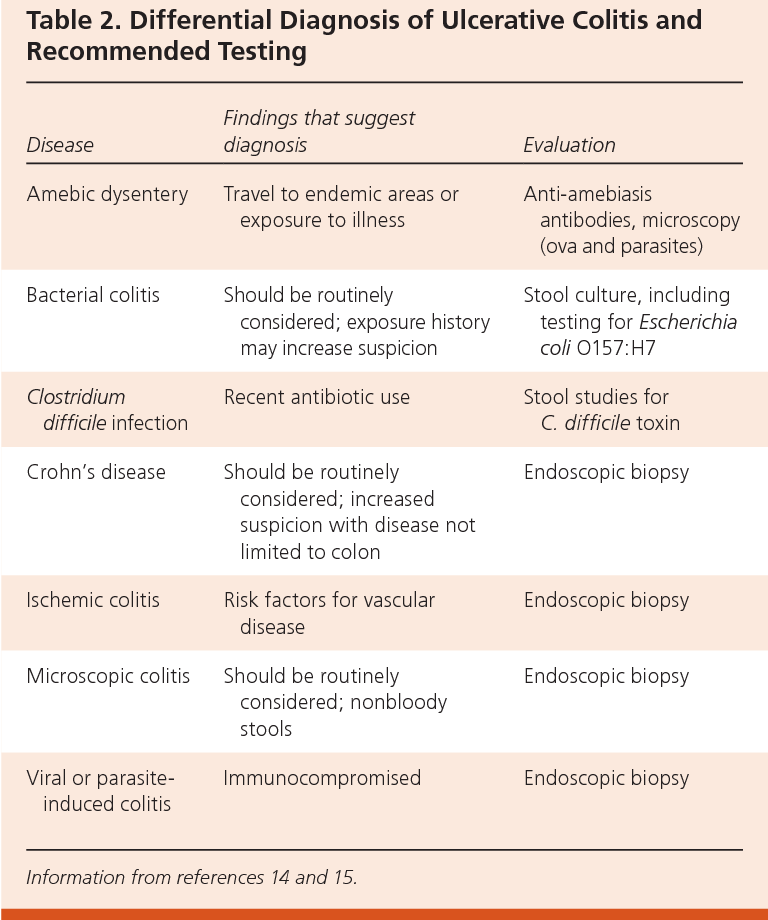

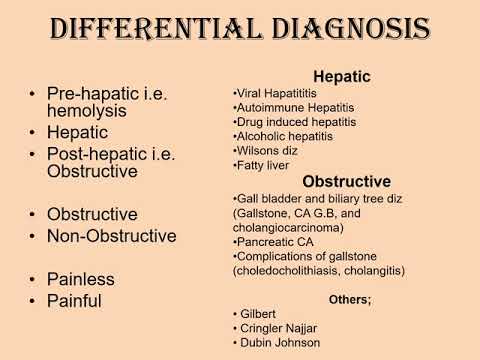

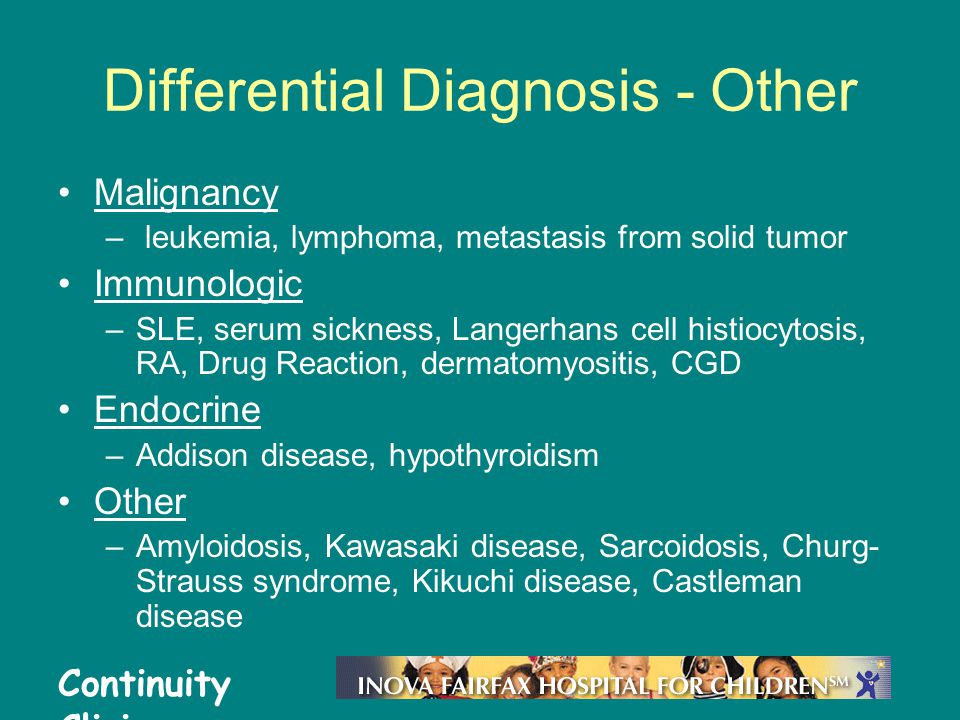

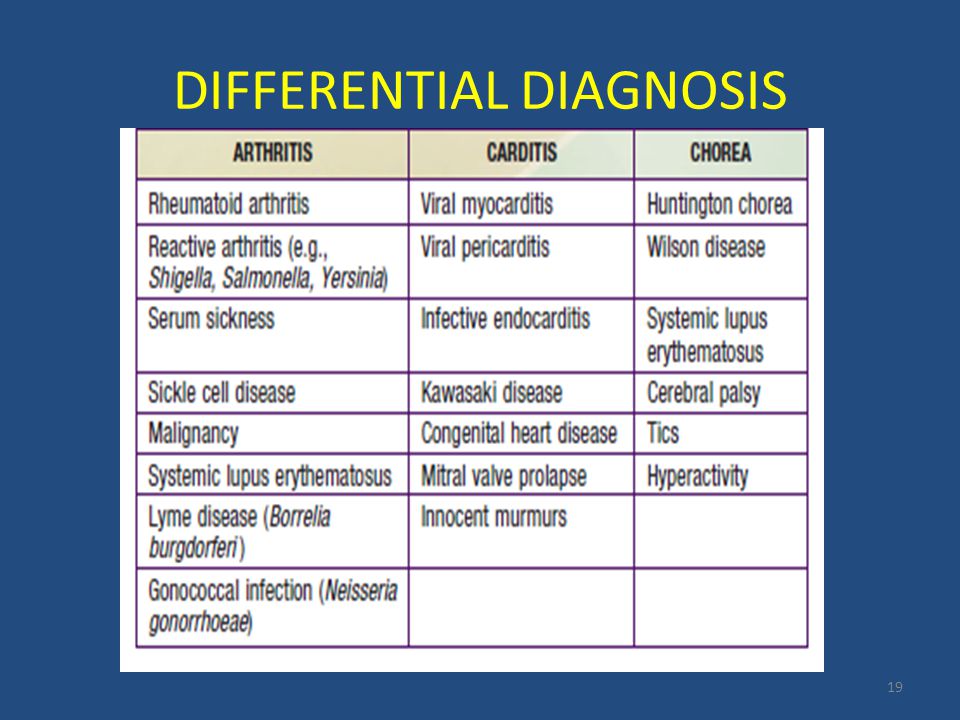

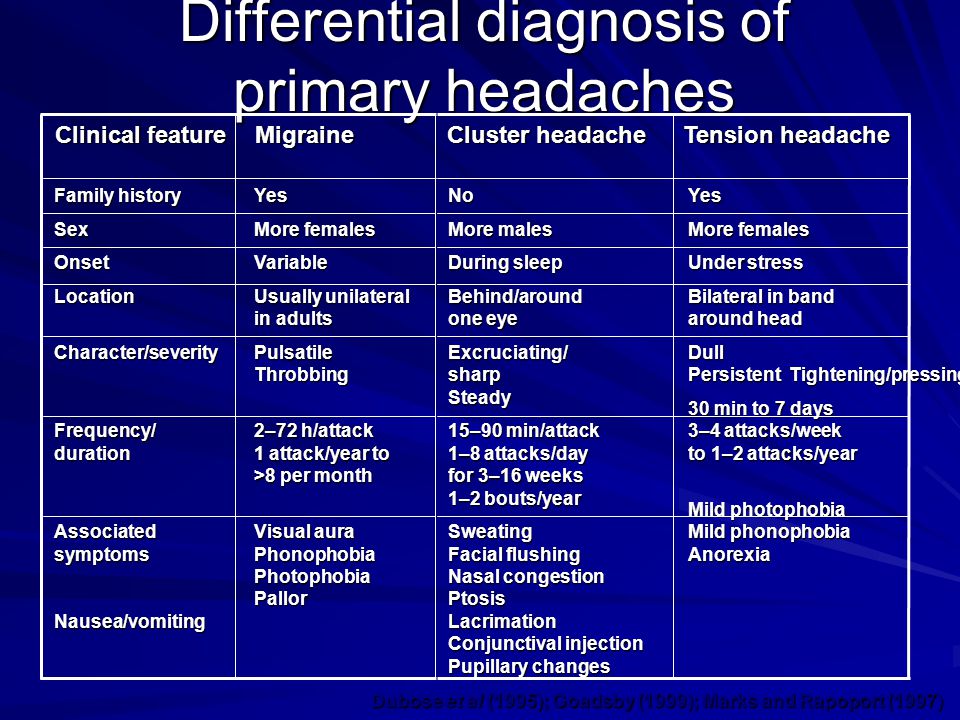

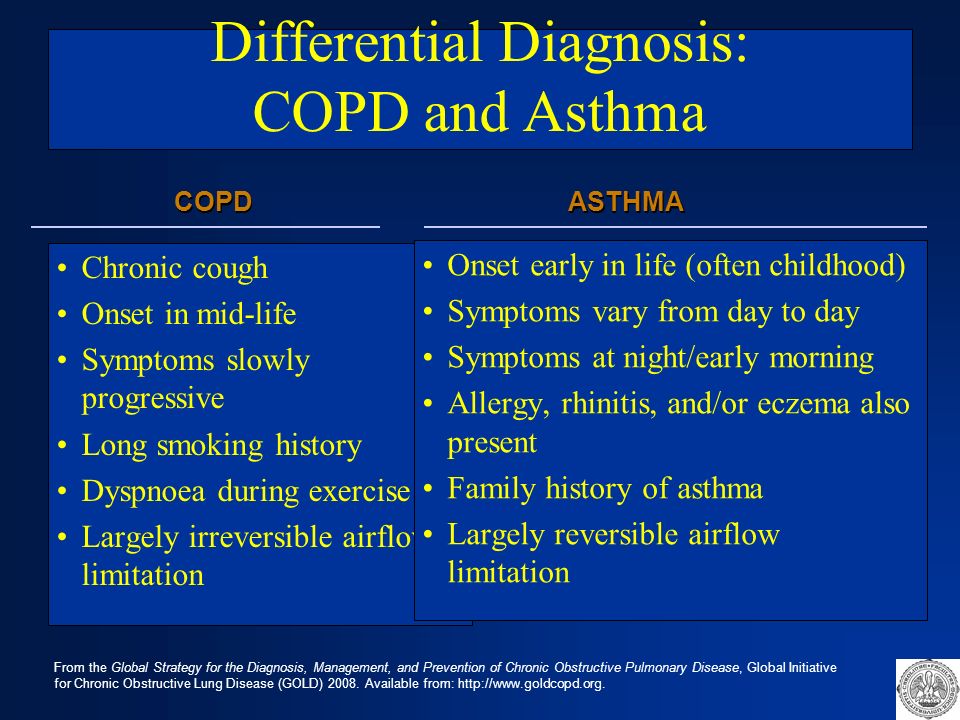

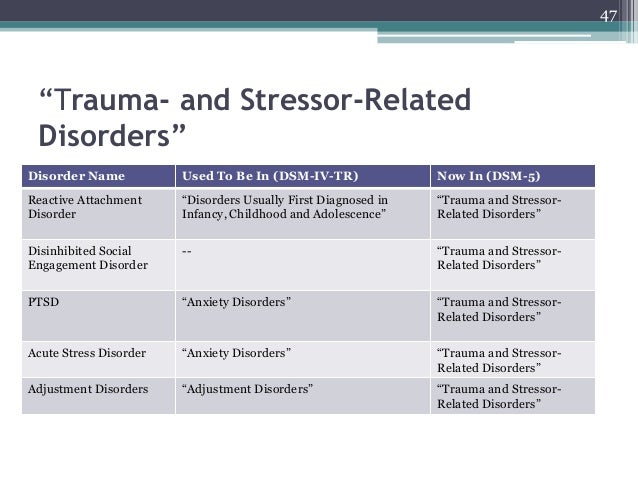

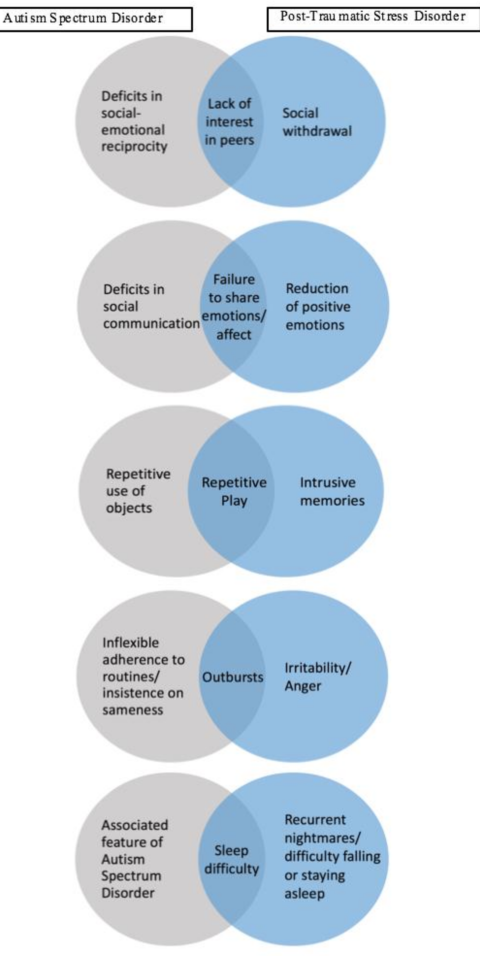

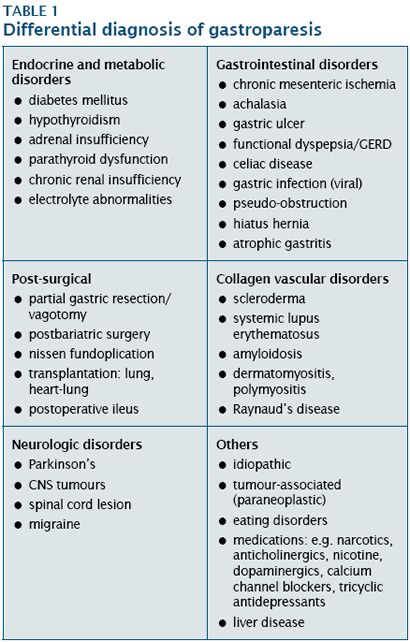

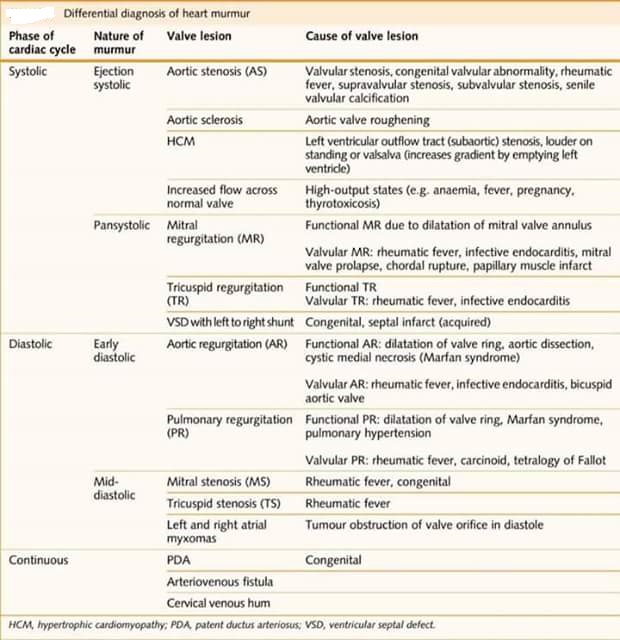

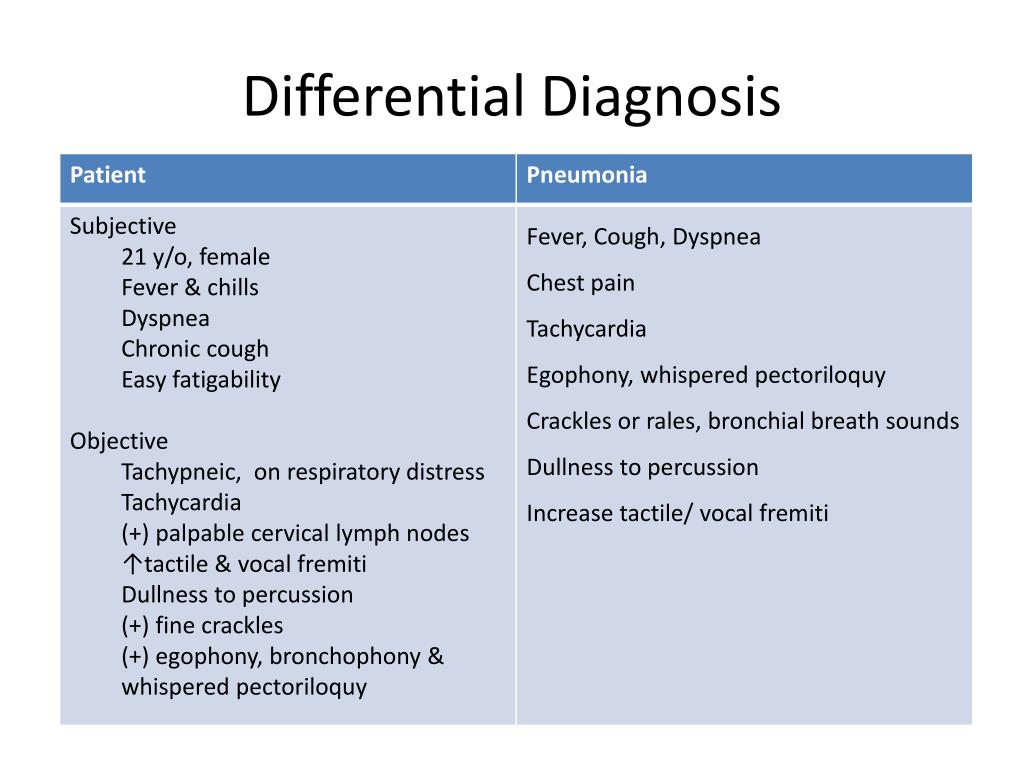

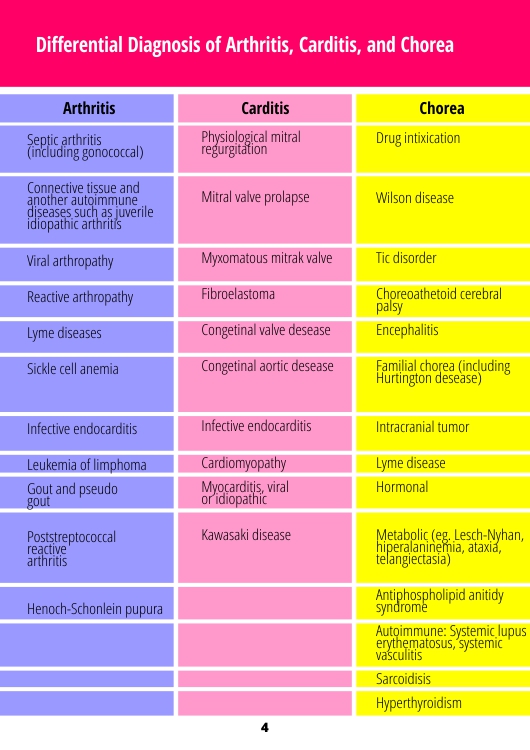

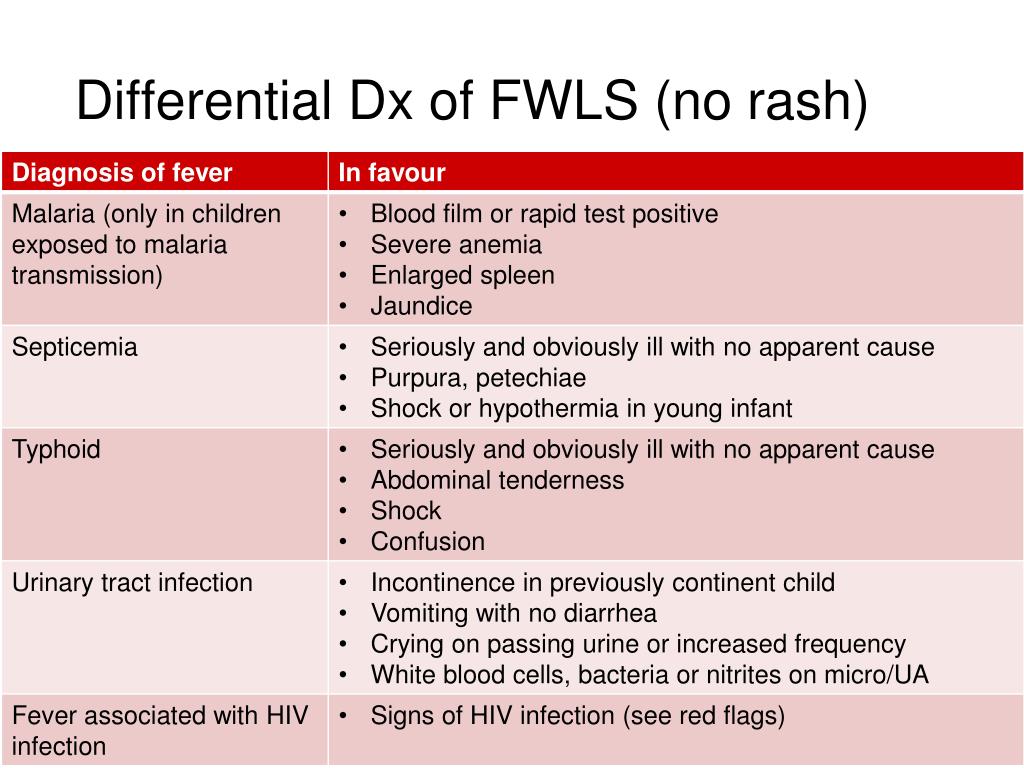

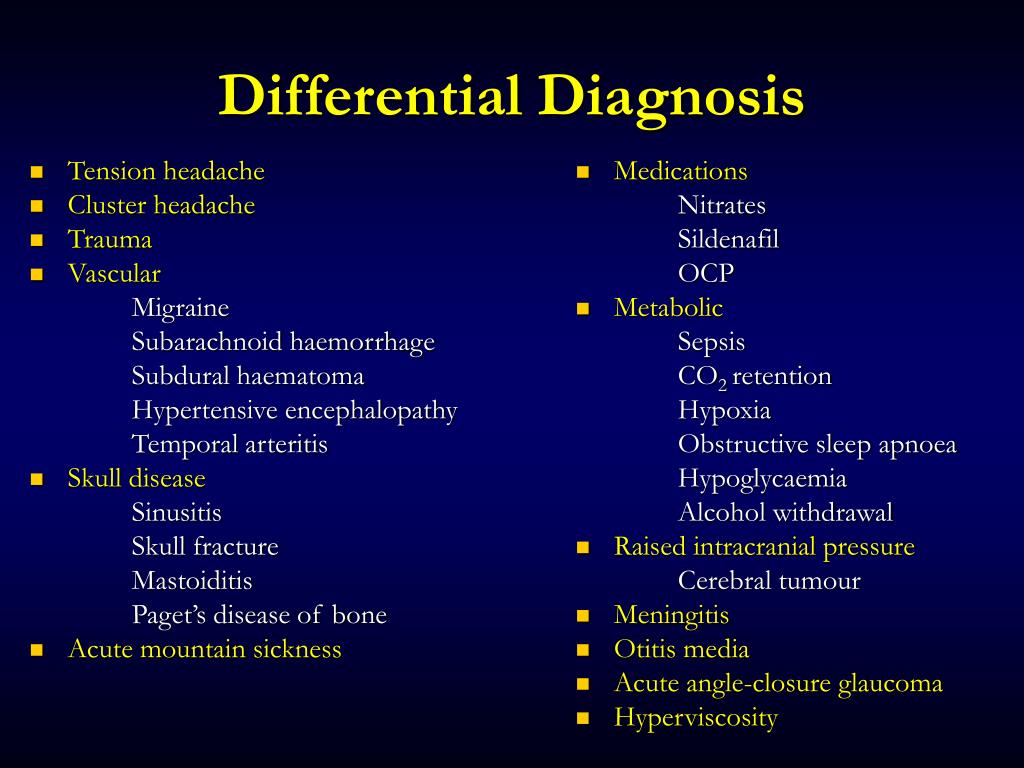

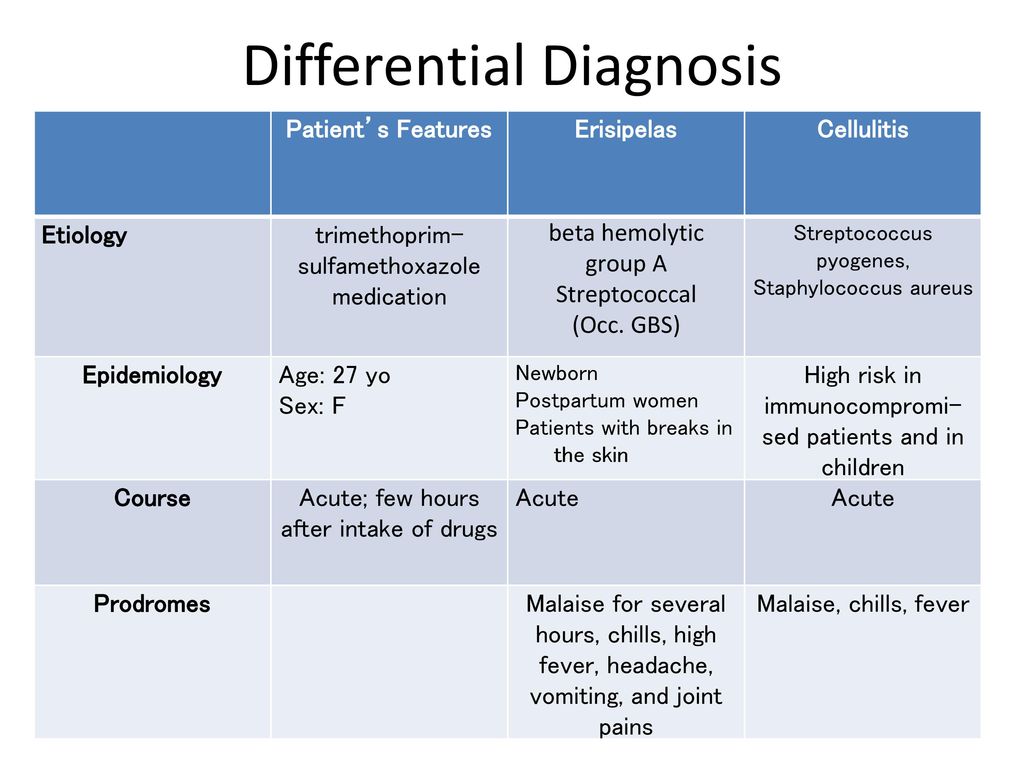

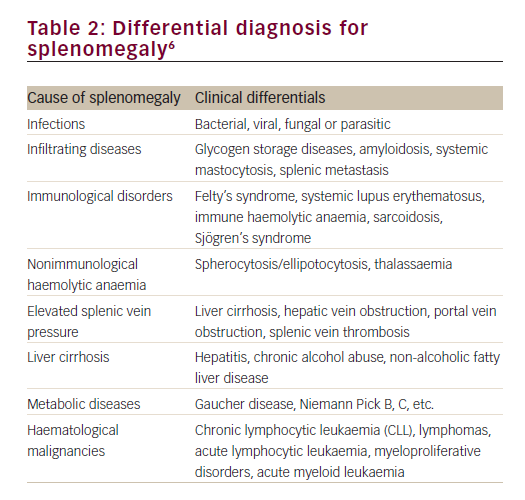

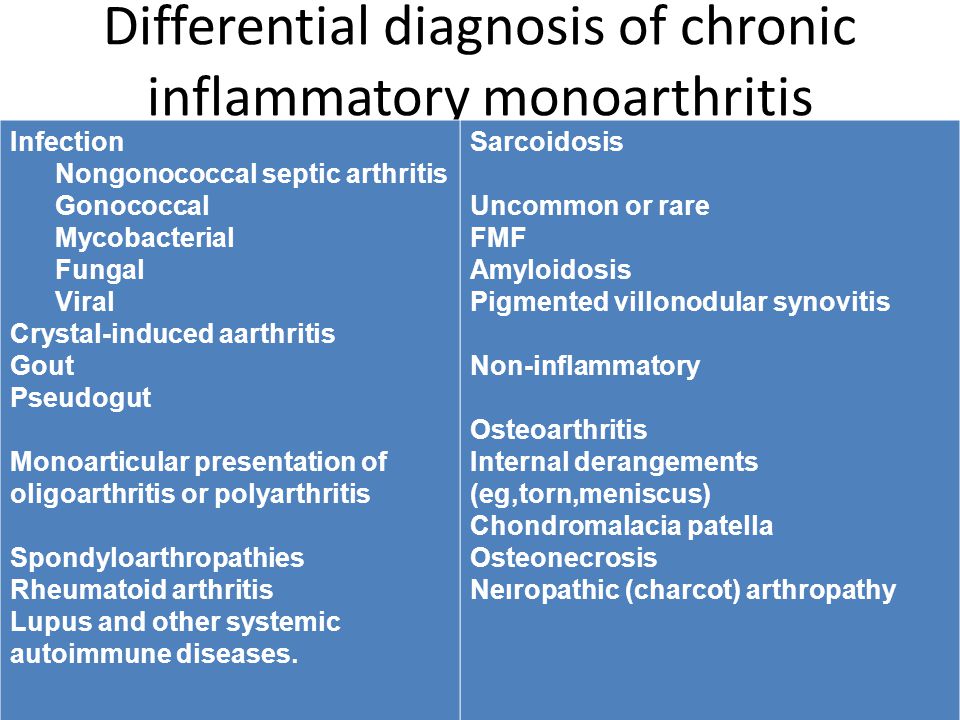

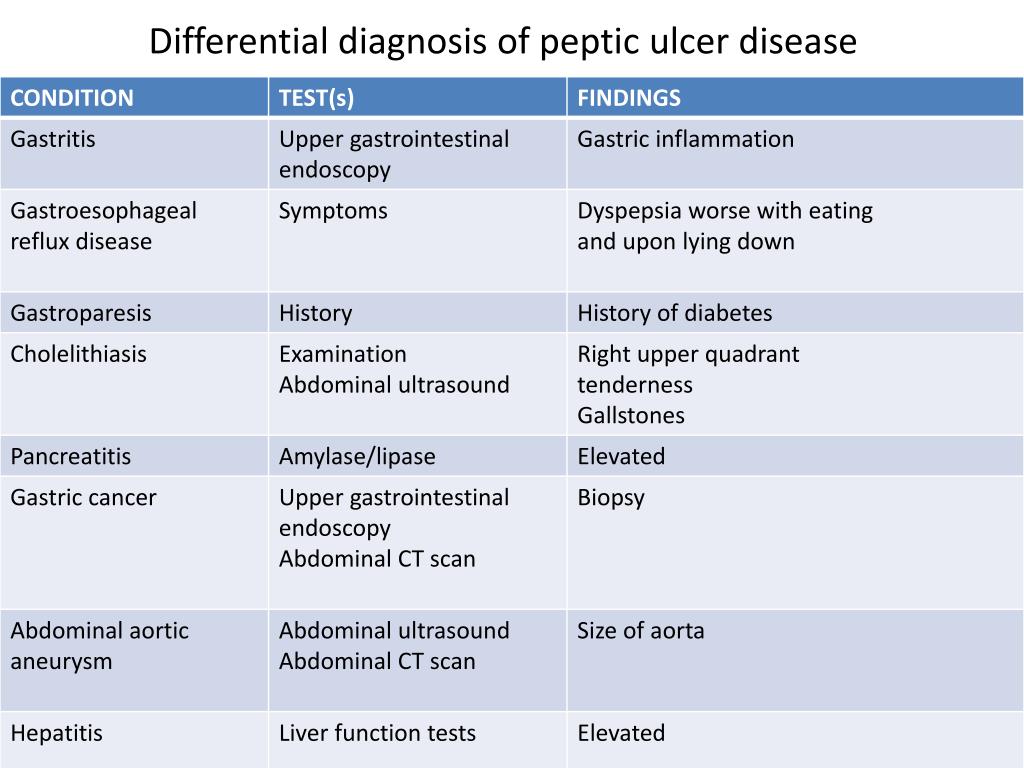

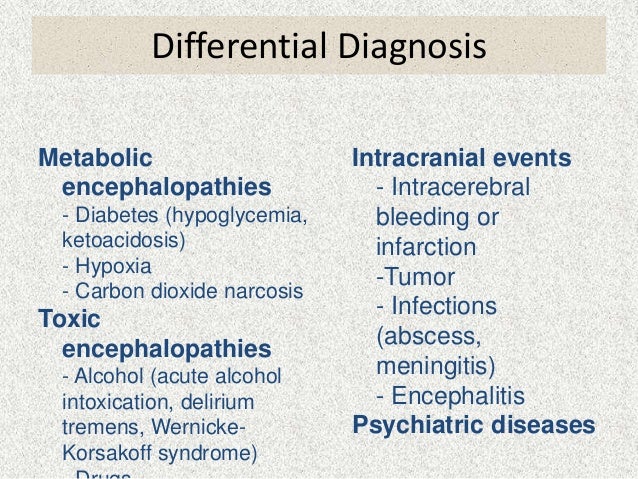

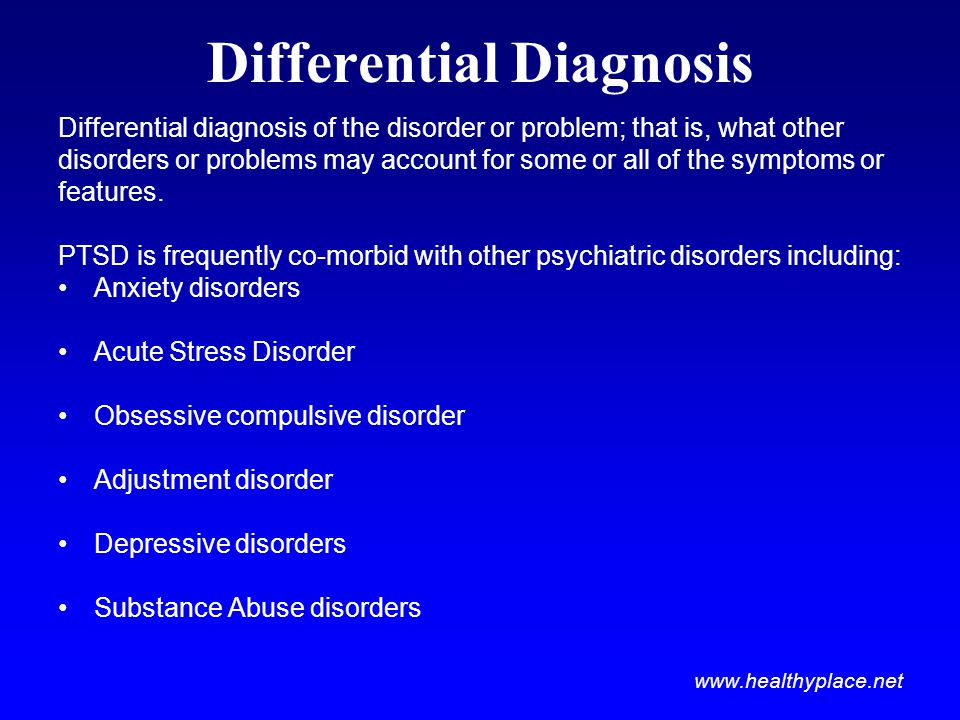

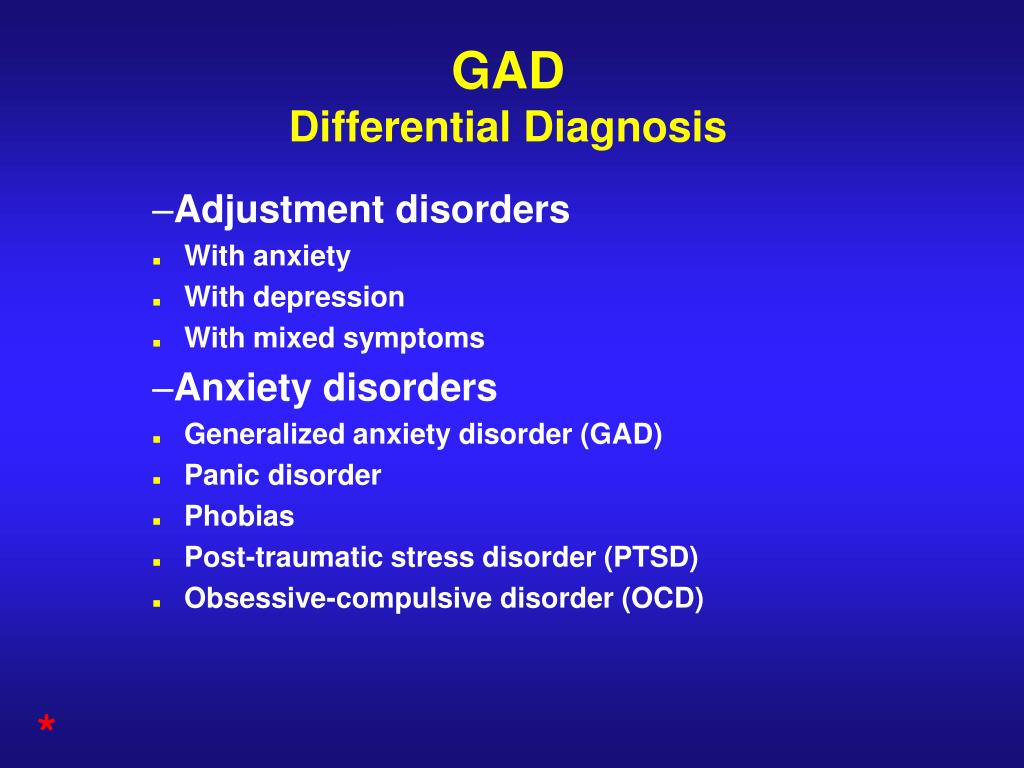

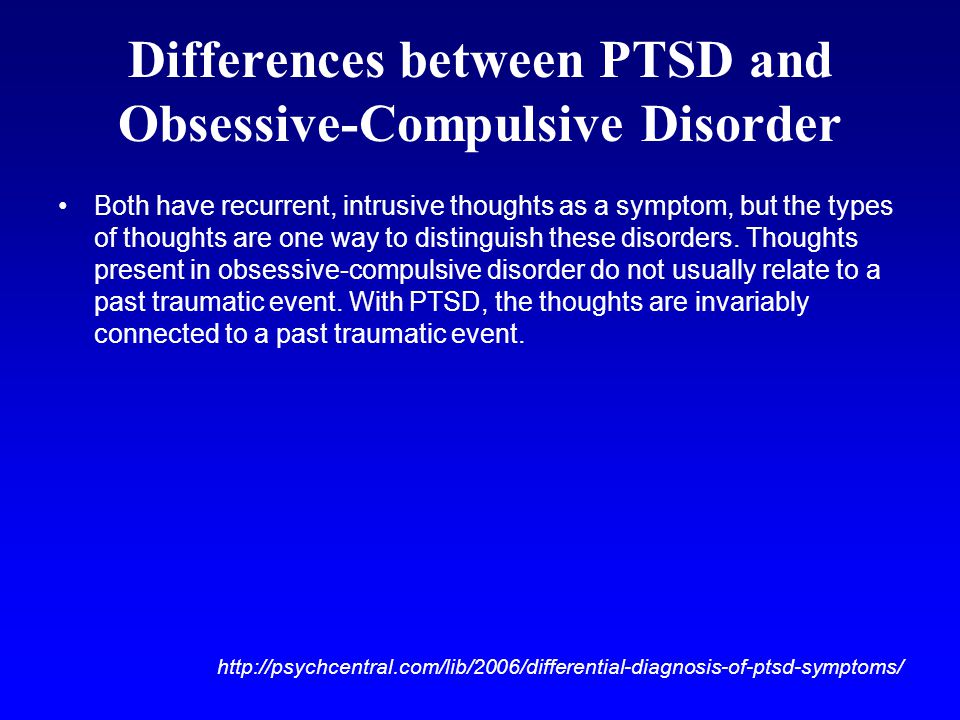

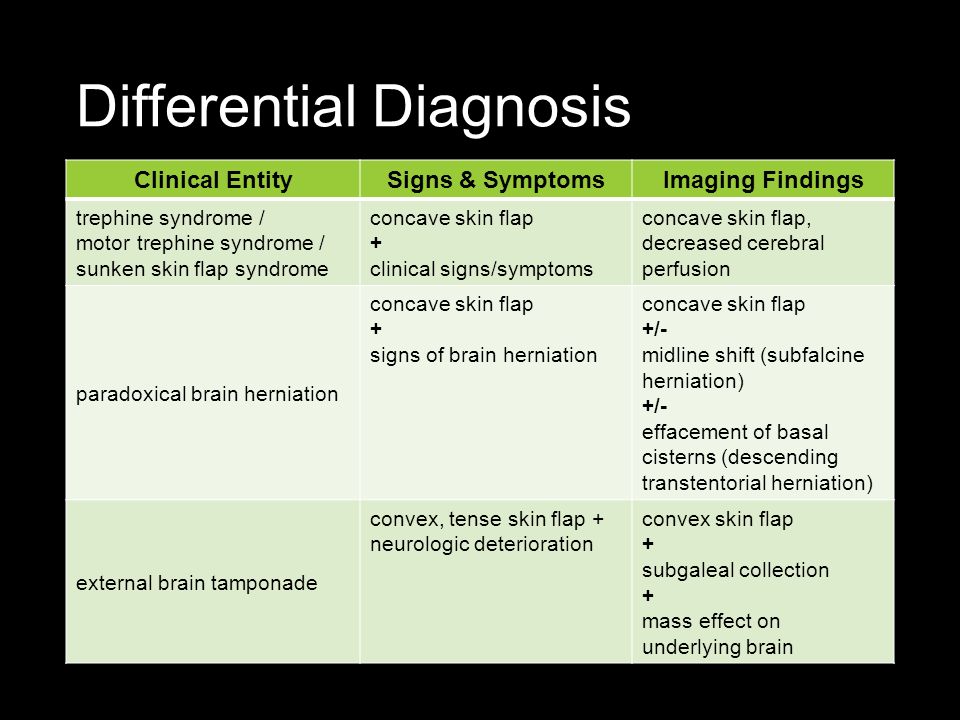

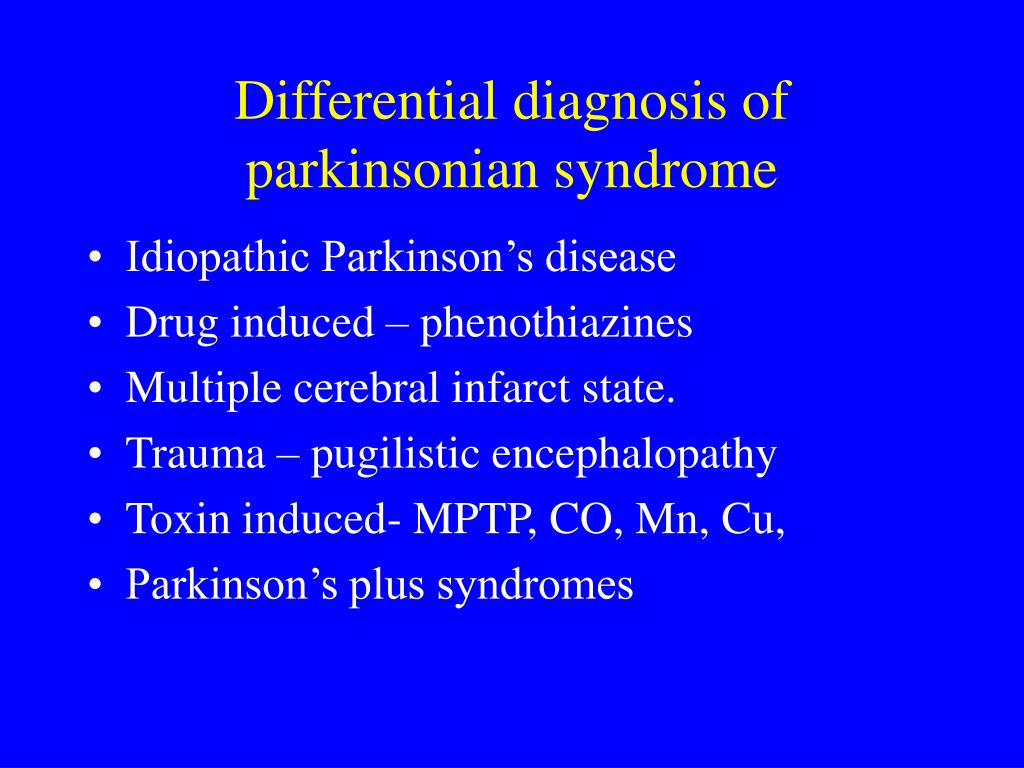

Differentials diagnosis. In the differential diagnosis of PTSD, it is important to consider acute stress disorder, dissociative disorders, depression, generalized anxiety, panic disorder, phobias, substance abuse, psychiatric manifestation of medical conditions, and malingering (Table 8).4 Primary care providers need to be keenly aware that PTSD commonly presents with the psychiatric conditions described in its differential diagnosis and to screen for signs of such co-occurring conditions during a patient’s initial evaluation.34

Physical examination. PTSD patients may have a disheveled appearance and poor personal hygiene. These patients may also present with physical injuries from recent traumatic events, such as bruises from physical abuse, injuries from assault, accidents, natural disasters, or terrorist attacks.35 The physical examination should focus on to alleviate the medical problems that may be causing the most significant distress symptoms, including insomnia, restlessness, fatigue, an exacerbation of medical problems that existed prior to the traumatic experience, and/or newly developed medical and neurological conditions. There is some evidence to indicate a relationship between PTSD and cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, and cognitive disorders.28,29

These patients may also present with physical injuries from recent traumatic events, such as bruises from physical abuse, injuries from assault, accidents, natural disasters, or terrorist attacks.35 The physical examination should focus on to alleviate the medical problems that may be causing the most significant distress symptoms, including insomnia, restlessness, fatigue, an exacerbation of medical problems that existed prior to the traumatic experience, and/or newly developed medical and neurological conditions. There is some evidence to indicate a relationship between PTSD and cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, and cognitive disorders.28,29

After controlling for risk factors such as alcohol consumption, weight, current substance abuse, and smoking, many PTSD patients—especially those in the combat veterans population—have nonspecific ECG abnormalities, atrioventricular conduction defects, infarctions, hypertension, and early onset cognitive decline.

Additional research is still needed to learn more about these associations before any general conclusion can be reached on the increased co-morbidity of the physical and medical conditions, and how these bodily system dysfunctionsmay be related to PTSD.13,35,36

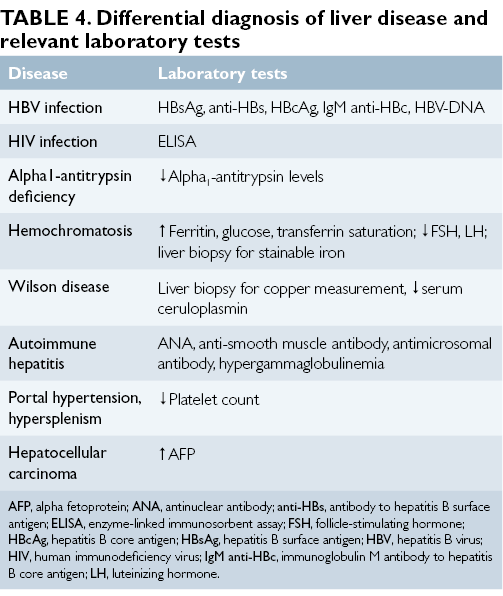

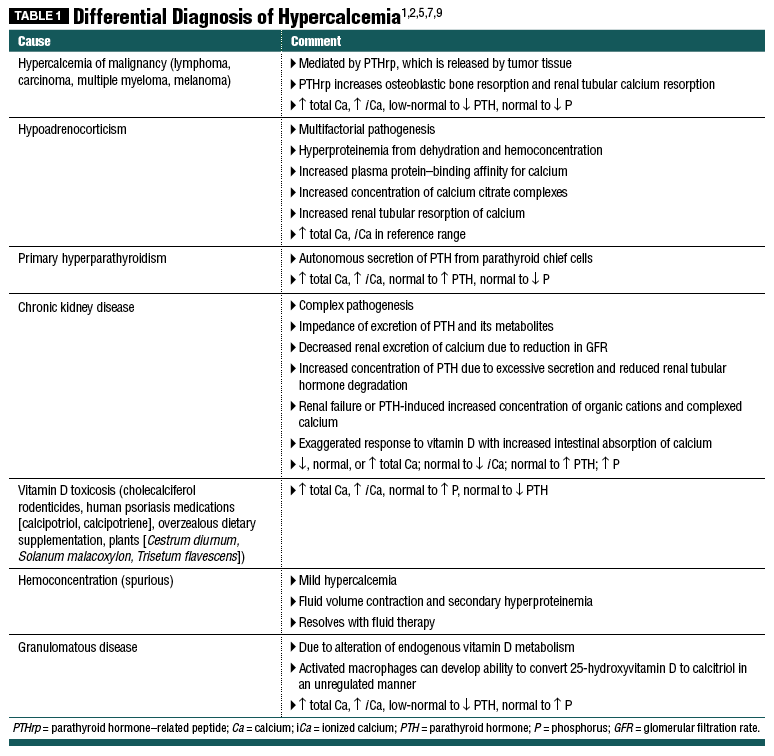

Laboratory testing. Although laboratory tests are not absolutely indicated for healthy individuals without physical injuries, it is important to consider screening patients with PTSD for thyroid abnormalities and substance abuse. Research studies have found decreased cortisol levels, elevated norepinephrine and epinephrine levels, and abnormal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity in patients with PTSD.36 Chronic insomnia and or ongoing daytime somnolence may warrant sleep study evaluation.

Brain imaging. Although routine brain imaging is not recommended for the diagnosis of PTSD, the presence of prominent cognitive symptoms could warrant brain imaging. 37 Computed tomography (CT) may identify traumatic brain injuries; magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies of some PTSD patients have shown a decreased hippocampus size and abnormal amygdale. Studies in monozygotic twins show an association between a small hippocampus and the predisposition for the development of PTSD. The suggested laboratory and other studies for PTSD evaluation are summarized in Table 9.13,35-37

37 Computed tomography (CT) may identify traumatic brain injuries; magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies of some PTSD patients have shown a decreased hippocampus size and abnormal amygdale. Studies in monozygotic twins show an association between a small hippocampus and the predisposition for the development of PTSD. The suggested laboratory and other studies for PTSD evaluation are summarized in Table 9.13,35-37

The comprehensive treatment of PTSD usually requires an integrated, multidimensional, interdisciplinary approach that combines patient education with pharmacological and psychological treatments and psychosocial and spiritual interventions. Treatment progress is often complicated by the presence of co-occurring psychiatric and medical conditions that need to be well managed. For example, if alcohol or substance abuse problems are present, they should be integrated in the overall treatment and management of patients. The September issue of Consultant will highlight treatment options for PTSD. ■

■

Acknowledgments:

The author thanks Dr Avak Howsepian for his constructive criticisms; Ms Susan E Shyshka, FACHE, for her administrative and leadership support, Dr Peter Watson for his encouragement; Dr Wessel Meyer for his clinical support; Dr Margaret Aimer for her supervision; Drs Robert Hierholzer, Nestor Manzano, Scott Ahles, and Craig C. Campbell for their academic guidance; and Dr Matthew Battista and Mr Leonard Williams, PA, for their encouragement.

References

1.Book of Genesis: Genesis 39-41. In: Holy Bible, New International Version, (NIV). Biblica, Inc.; 2011.

2.Trimble MD. Post-traumatic stress disorder: history of a concept. In Figley CR (ed). Trauma and its Wake: The Study and Treatment of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. New York: Brunner/Mazel; 1985.

3.The American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed). Washington, DC; 1980.

4.Khouzam HR, Tan DT, Gill SG. The patient with posttraumatic stress disorder. In: Handbook of Emergency Psychiatry. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Mosby;2007:453-473.

The patient with posttraumatic stress disorder. In: Handbook of Emergency Psychiatry. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Mosby;2007:453-473.

5.The American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed). Washington, DC; 2013.

6.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Delmer O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593-602.

7.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication.Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617-627.

8.Kilpatrick DG, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R, et al. Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity: results from the National Survey of Adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(4):692-700.

9.Kessler RC, Üstün TB (eds). The WHO World Mental Health Surveys: global perspectives on the epidemiology of mental disorders. New York: Cambridge University Press:1-580.

New York: Cambridge University Press:1-580.

10.Kulka RA, Schlenger WA, Fairbanks JA, et al. Trauma and the Vietnam War generation: Report of findings from the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study. New York: Brunner/Mazel; 1990.

11.Smith-Osborne A. Mental health risk and social ecological variables associated with educational attainment for gulf war veterans: implications for veterans returning to civilian life. Am J Community Psychol. 2009;44(3-4):327-337.

12.Tanielian T, Jaycox L (eds). Invisible Wounds of War: Psychological and Cognitive Injuries, Their Consequences, and Services to Assist Recovery. Santa Monica, Calif: RAND Corporation; 2008.

13.Khouzam HR, Ghafoori B, Hierholzer R. Progress in the identification,diagnosis and treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder In: Corales TA (ed). Trends in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Research. New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc; 2005:1-28.

14.Álvarez MJ, Roura P, Foguet Q, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder comorbidity and clinical implications in patients with severe mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2012;200(6):549-552.

Posttraumatic stress disorder comorbidity and clinical implications in patients with severe mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2012;200(6):549-552.

15.Norris F, Sloane LB. The epidemiology of trauma and PTSD. In: Friedman MJ, Keane TM, Resick PA (eds). Handbook of PTSD: Science and Practice. New York: Guilford Press; 2007:78-98.

16.Yehuda R, Bierer LM. Transgenerational transmission of cortisol and PTSD risk. Prog Brain Res. 2008;167:121-35.

17.Phillips ML, Drevets WC, Rauch SL, Lane R. Neurobiology of emotion perception I: The neural basis of normal emotion perception. Biol Psychiatry.2003;54:504-514.

18.Laurent V, Westbrook RF. Distinct contributions of the basolateral amygdala and the medial prefrontal cortex to learning and relearning extinction of context conditioned fear. Learn Mem. 2008;15(9):657-66.

19.Post RM, Weiss N, Smith MA. Sensitization and kindling: implications for the evolving neural substrates of posttraumatic stress disorder. In: Friedman MJ, Charney DS, Deutch AY (eds). Neurobiological and Clinical Consequences of Stress: From Normal Adaptation to PTSD. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1995:203-224.

In: Friedman MJ, Charney DS, Deutch AY (eds). Neurobiological and Clinical Consequences of Stress: From Normal Adaptation to PTSD. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1995:203-224.

20.Liberzon I, Britton JC, Phan KL. Neural correlates of traumatic recall in posttraumatic stress disorder. Stress. 2003;6:151-156.

21.Wolff N, Frueh BC, Shi J, et al. Trauma exposure and mental health characteristics of incarcerated females self-referred to specialty PTSD treatment.Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(8):954-958.

22.Karunakara UK, Neuner F, Schauer M, et al. Traumatic events and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder amongst Sudanese nationals, refugees and Ugandans in the West Nile. Afr Health Sci. 2004;4(2):83-93.

23.Barlow J, Birch L. Midwifery practice and sexual abuse. Br J Midwifery. 2004;12(2):72-75.

24.Ahmed AS. Post-traumatic stress disorder, resilience and vulnerability. Adv Psychiatry Treat. 2007;13:369-375.

25. Bonanno GA. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? Am Psychol.2004;59(1):20-28.

Bonanno GA. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? Am Psychol.2004;59(1):20-28.

26.Charney DS. Psychobiological mechanisms of resilience and vulnerability: implications for successful adaptation to extreme stress. Am Psychiatry. 2004;161(2):195-216.

27.Nakajima S, Masaya I, Akemi S, Takako K. Complicated grief in those bereaved by violent death: the effects of post-traumatic stress disorder on complicated grief. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2012;14(2):210-214.

28.Yaffe K, Vittinghoff E, Lindquist K, et al. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Risk of Dementia Among US Veterans Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):608-613.

29.Boscarino JA. A prospective study of PTSD and early-age heart disease mortality among Vietnam veterans: implications for surveillance and prevention.Psychosom Med. 2008;70:668-676.

30.Samuelson KW, Neylan TC, Lenoci M, et al. Longitudinal effects of PTSD on memory functioning. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2009;15(6):853-861.

Longitudinal effects of PTSD on memory functioning. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2009;15(6):853-861.

31.Vasterling JJ, Duke LM, Brailey K, et al. Attention, learning, and memory performances and intellectual resources in Vietnam veterans: PTSD and no disorder comparisons. Neuropsychology. 2002;16(1):5-14.

32.Breslau N, Peterson EL, Kessler RC, Schultz LR. Short screening scale for DSM-IV posttraumatic stress disorder. Am Psychiatry. 1999;156:908-911.

33.Khouzam HR. A simple mnemonic for the diagnostic criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder. West J Med. 2001;174(6):424.

34.Khouzam HR, Donnelly NJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder. Safe, effective management in the primary care setting. Postgrad Med. 2001;110(5):60-2, 67-70, 77-78.

35.Gilbertson MW, Orr SP, Rauch SL, Pitman RK. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder. In: Stern TA, Rosenbaum JF, Fava M, et al (eds). Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry (1st ed). Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2008.

Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2008.

36.Boscarino JA. Posttraumatic stress disorder and physical illness: results from clinical and epidemiologic studies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1032:141-153.

37.Dickie EW, Brunet A, Akerib V, Armony JL. An fMRI investigation of memory encoding in PTSD: influence of symptom severity. Neuropsychologia.2008;46(5):1522-1531.

Is It PSTD or Something Else?

PTSD Differential Diagnosis: Is It PSTD or Something Else?- Conditions

- Featured

- Addictions

- Anxiety Disorder

- ADHD

- Bipolar Disorder

- Depression

- PTSD

- Schizophrenia

- Articles

- Adjustment Disorder

- Agoraphobia

- Borderline Personality Disorder

- Childhood ADHD

- Dissociative Identity Disorder

- Narcissistic Personality Disorder

- Narcolepsy

- Oppositional Defiant Disorder

- Panic Attack

- Postpartum Depression

- Schizoaffective Disorder

- Seasonal Affective Disorder

- Sex Addiction

- Specific Phobias

- Teenage Depression

- Trauma

- Featured

- Discover

- Wellness Topics

- Black Mental Health

- Grief

- Emotional Health

- Sex & Relationships

- Trauma

- Understanding Therapy

- Workplace Mental Health

- Original Series

- My Life with OCD

- Caregivers Chronicles

- Empathy at Work

- Sex, Love & All of the Above

- Parent Central

- Mindful Moment

- News & Events

- Mental Health News

- COVID-19

- Live Town Hall: Mental Health in Focus

- Podcasts

- Inside Mental Health

- Inside Schizophrenia

- Inside Bipolar

- Wellness Topics

- Quizzes

- Conditions

- ADHD Symptoms Quiz

- Anxiety Symptoms Quiz

- Autism Quiz: Family & Friends

- Autism Symptoms Quiz

- Bipolar Disorder Quiz

- Borderline Personality Test

- Childhood ADHD Quiz

- Depression Symptoms Quiz

- Eating Disorder Quiz

- Narcissim Symptoms Test

- OCD Symptoms Quiz

- Psychopathy Test

- PTSD Symptoms Quiz

- Schizophrenia Quiz

- Lifestyle

- Attachment Style Quiz

- Career Test

- Do I Need Therapy Quiz?

- Domestic Violence Screening Quiz

- Emotional Type Quiz

- Loneliness Quiz

- Parenting Style Quiz

- Personality Test

- Relationship Quiz

- Stress Test

- What's Your Sleep Like?

- Conditions

- Resources

- Treatment & Support

- Find Support

- Suicide Prevention

- Drugs & Medications

- Find a Therapist

- Treatment & Support

Medically reviewed by Ashleigh Golden, PsyD — By Brittany VanDerBill — Updated on June 23, 2021

If you’re not sure whether your symptoms are due to PTSD or something else, it may be worth asking your doctor or therapist about differential diagnoses (conditions with similar symptoms).

Going through a jarring or traumatic event isn’t easy. Afterward, you may find it difficult to put the experience behind you. You might continue to feel unusually anxious long after this difficult or traumatizing situation has passed.

A traumatic experience can sometimes lead to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), though not all trauma leads to PTSD. And many other conditions have overlapping symptoms with PTSD, which can make getting an accurate diagnosis more complex.

Having some anxiety or additional worries is natural after something bad happens. But when do your symptoms signal PTSD? And could they be a sign of something other than PTSD?

The condition we know as post-traumatic stress disorder was once used almost exclusively to describe the symptoms of veterans who had experienced combat during war. But in these instances, the condition was referred to as “shell shock.” Today, modern research has helped us understand that PTSD can arise from other trauma, too.

The American Psychological Association notes that PTSD is considered to be an anxiety issue related to a traumatic occurrence.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5) definition of trauma requires “actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence.” Examples of trauma can include combat experience, abuse or assault, or surviving a natural disaster.

Some symptoms of PTSD can include:

- vivid and unwanted memories of the traumatic event

- staying away from anything related to the event or where it took place

- shame or guilt about what happened

- changes in mood

- anger or rage

- causing harm to oneself

It’s important to note that not everyone who goes through a traumatic event has PTSD. Additionally, you may discover that you have PTSD along with another condition.

A differential diagnosis is when a doctor works out which disorder someone has when several disorders have overlapping symptoms.

Receiving an accurate diagnosis is often an important first step toward finding the treatments, coping methods, and support networks that will help you heal. Talking with a doctor or therapist about your symptoms and experiences will help you find the right diagnosis and treatment plan for you.

It’s important not to attempt your own differential diagnosis at home — only licensed mental health professionals, like counselors, therapists, clinical social workers, psychologists, and psychiatrists — can make this assessment.

The following conditions share some similarities with PTSD:

- acute stress disorder

- complex PTSD

- dissociative disorders

- adjustment disorder

- generalized anxiety disorder

- depression

- panic disorder

- phobias

- substance use disorders

We look at some of these conditions in more detail below.

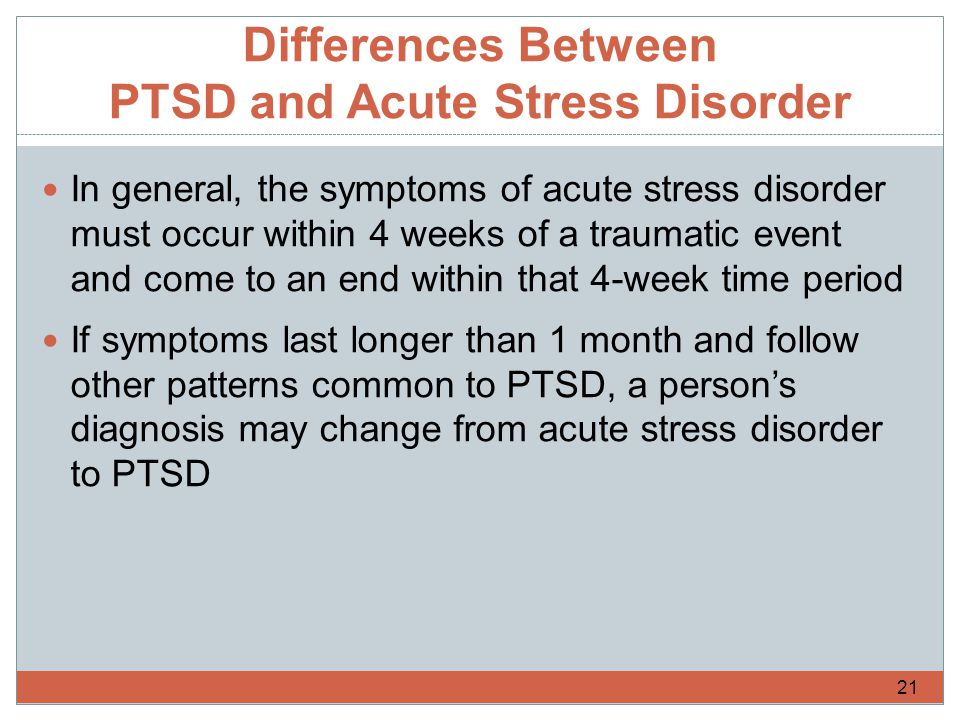

Acute stress disorder

This disorder has some highly similar symptoms to PTSD. The main factor that is considered in a PTSD differential diagnosis in this instance is how long you’ve experienced your symptoms. Generally speaking, PTSD requires symptoms to last for at least one month.

The main factor that is considered in a PTSD differential diagnosis in this instance is how long you’ve experienced your symptoms. Generally speaking, PTSD requires symptoms to last for at least one month.

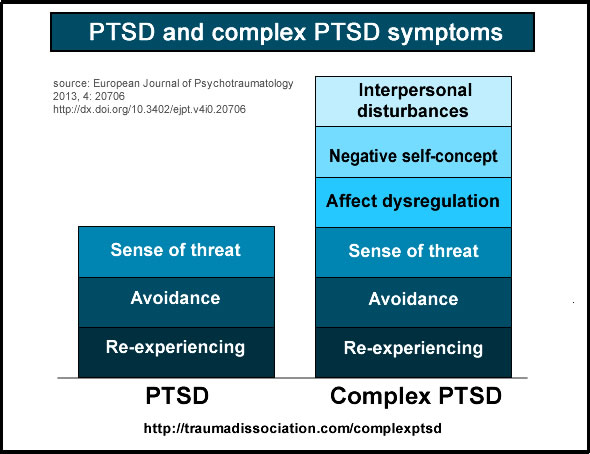

Complex PTSD

Complex PTSD has similar symptoms to PTSD, but the cause is different. While PTSD is usually linked with a single event, complex PTSD develops after repeated exposure to traumatic events, such as childhood neglect or abuse within a relationship.

Complex PTSD is not listed in the DSM-5, but many therapists recognize and treat its symptoms.

Dissociative disorders

Dissociation is one way the body deals with traumatic experiences. When you experience trauma, you might feel a disconnect between your mind and body. This helps give you some distance from the traumatic event.

While dissociation has a useful function in the moment, people with PTSD may notice that dissociation occurs again later on, and it can interrupt their daily lives. For example, someone with PTSD might feel as though they are detached from reality during a flashback.

A variety of dissociative disorders exist, and they often share some common symptoms. These include:

- dissociative identity disorder

- depersonalization/derealization disorder

- dissociative amnesia

The causes of dissociative disorders are often rooted in past traumas, so they are closely linked with PTSD. There’s also a subtype of PTSD that is a form of dissociative disorder. It’s important to reach out for professional help to distinguish which condition may be impacting you.

Generalized anxiety disorder

One reason that PTSD can be confused with generalized anxiety disorder is the intense anxiety you experience with both conditions. Intrusive thoughts and a tendency to feel angry or on edge are also fairly common with both.

People with generalized anxiety disorder have a history of anxiety across a wide range of circumstances, whereas people with PTSD often experience anxiety in response to a major trauma.

Depression

Sometimes, the symptoms of depression and PTSD can look and feel alike. People with depression may feel hopeless, or they may feel intense amounts of shame and guilt. People with PTSD also tend to experience this extreme shame, but it’s primarily focused on the event that occurred.

People with depression may feel hopeless, or they may feel intense amounts of shame and guilt. People with PTSD also tend to experience this extreme shame, but it’s primarily focused on the event that occurred.

Panic disorder

Someone with panic disorder may experience intense feelings of anxiety. This can be related to a specific object or situation. In these cases, you might avoid that specific thing to prevent a panic attack from occurring. A person who experienced trauma may avoid certain situations as well, so these two conditions can feel quite similar in this way.

Substance use disorder

When a person has a substance use disorder, they may experience a few symptoms in common with PTSD. For instance, substance use disorders could cause high anxiety or feelings of being on edge. They could also bring changes in mood and habits, just like with PTSD.

A differential diagnosis can be helpful in distinguishing between PTSD and something else. However, it is possible that you may have both PTSD and another condition with similar characteristics.

When this happens, it’s referred to as comorbidity.

Substance use disorder is a particularly common comorbidity. The PTSD Alliance reports that more than 7 million people in the United States have PTSD. Of those people, they note that as many as 40% also experience addiction.

Further, researchers estimate that almost 52% of males experiencing PTSD have a substance use disorder.

If you’re living with PTSD and substance use disorder or other conditions, don’t lose hope. Many resources exist for people experiencing these conditions.

You may want to begin by seeking help from your primary care physician. They can provide referrals to additional resources where necessary. If you already have a trusted counselor or psychiatrist, they would be a safe and helpful person to reach out to.

It’s important to be honest and open about all of your symptoms when speaking with any mental health professional you work with. This includes symptoms related to PTSD and those that could be related to other conditions, such as panic disorder or depression. Doing so ensures that you will receive the help that you need to start healing.

Doing so ensures that you will receive the help that you need to start healing.

There are various evidence-based treatments for PTSD, including:

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). CBT helps people challenge the patterns of behaviors, feelings, and thoughts that are causing distress.

- Cognitive processing therapy (CPT). CPT helps people modify and challenge unhelpful trauma-related beliefs.

- Prolonged exposure therapy. This type of CBT teaches people to gradually approach memories, feelings, and places related to the trauma to learn that they aren’t dangerous.

Suicide prevention

If you or someone you know is considering suicide, you’re not alone. Help is available right now:

- Call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 24 hours a day at 800-273-8255.

- Text “HOME” to the Crisis Text Line at 741741.

- Call the Veterans Crisis Line 24 hours a day at 800-273-8255

Not in the U. S.? Find a helpline in your country with Befrienders Worldwide.

S.? Find a helpline in your country with Befrienders Worldwide.

The important thing to remember with PTSD is that there is hope. Millions of other people are also going through PTSD. Many more are also experiencing other conditions as well.

Knowing that you aren’t alone can help give you the courage to reach out and ask for some help. Contact your primary care physician or, if you know of one already, a mental health professional. They will have the training to help you with your PTSD and other conditions. They also can refer you to other professionals who can provide further assistance as needed.

If you’re unsure how to ask someone for help, this guide will assist you in finding the words to begin your path to healing. You might also find that podcasts can be helpful on this journey. While not a substitute for treatment, they may help you feel less alone or more supported on your path to wellness.

Getting help for PTSD is important for healing, and by taking the time to read this article, you’re taking those first steps toward healing.

Last medically reviewed on June 23, 2021

6 sourcescollapsed

- CSTS uniformed services university. (n.d.).

cstsonline.org/assets/media/documents/CSTS_CTC_Asking_for_Help_Do_You_Know_How.pdf - Mann SK, et al. (2021). Posttraumatic stress disorder.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559129/ - Pai A, et al. (2017). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the DSM-5: Controversy, change, and conceptual considerations.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5371751/ - Post-traumatic stress disorder. (n.d.).

apa.org/topics/ptsd - PTSD treatments. (2020).

apa.org/ptsd-guideline/treatments - van Huijstee J, et al. (2018). The dissociative subtype of post-traumatic stress disorder: Research update on clinical and neurobiological features.

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29063485/

FEEDBACK:

Medically reviewed by Ashleigh Golden, PsyD — By Brittany VanDerBill — Updated on June 23, 2021

Read this next

What Are the Symptoms of PTSD?

Medically reviewed by Karin Gepp, PsyD

How do you know if you have PTSD? There's a long list of symptoms and diagnostic criteria.

Here's what you need to know.

Here's what you need to know.READ MORE

Can You Recover from Trauma? 5 Therapy Options

Trauma-informed therapy can help you reduce the emotional and mental effects of trauma. Here are the best options for trauma-focused treatments.

READ MORE

Podcast: There’s More to Trauma than PTSD

Learn about the differences between PTSD and other forms of trauma, how to identify it, and what can be done about it.

READ MORE

How Does PTSD Affect Relationships?

Medically reviewed by N. Simay Gökbayrak, PhD

PTSD is a mental health condition that may affect different aspects of your life, including your relationships. Here's how and what to do.

READ MORE

Types of PTSD

Medically reviewed by N.

Simay Gökbayrak, PhD

Simay Gökbayrak, PhDPost-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can be broken down by type and severity of symptoms. Each type has different treatments and ways to manage it.

READ MORE

Residual Symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Medically reviewed by Kendra Kubala, PsyD

Treatment isn't always the end of PTSD. Some people might have residual symptoms, but they can be managed.

READ MORE

What Is Imagery Rehearsal Therapy (IRT)?

Medically reviewed by Nicole Washington, DO, MPH

If you often have nightmares because of trauma in your past, imagery rehearsal therapy could help you manage and reduce them.

READ MORE

What Causes Depression?

Medically reviewed by Akilah Reynolds, PhD

What causes depression? Experts suggest it's a complex blend of your biology, psychology, and social environment.

READ MORE

What Causes Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID)?

Medically reviewed by Jeffrey Ditzell, DO

An important part of treating dissociative identity disorder is working out its causes and healing the trauma that often underlies this condition.

READ MORE

Feeling Empty? What It Means and What to Do

It's natural to feel empty or numb from time to time. But what happens when you've been feeling empty for a while now?

READ MORE

Post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents

Children are exposed to a variety of traumatic events, and each child has a different reaction to trauma. Some deal with shocks relatively painlessly, while others may develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, depression, and other behavioral problems. In an article by G. Hornor "Posttraumatic Stress Disorder", published in the Journal of Pediatric Health Care (2013; 27 (3): e29-e38), provides data that will help professionals working with children to better understand the diagnosis, prevalence, risk factors and comorbidity of PTSD, as well as understand the methods of treatment of this disorder.

In an article by G. Hornor "Posttraumatic Stress Disorder", published in the Journal of Pediatric Health Care (2013; 27 (3): e29-e38), provides data that will help professionals working with children to better understand the diagnosis, prevalence, risk factors and comorbidity of PTSD, as well as understand the methods of treatment of this disorder.

According to DSM-IV criteria, symptoms of PTSD develop in a person who has been exposed to excessive trauma. Trauma can occur if a person (APA, 1994): has personally experienced an event that directly threatened life or health; witnessed the death, injury or threat to the life of others; learned of a sudden or tragic death, serious injury or threat to someone close.

Response to trauma includes intense fear, feelings of hopelessness, terror, inappropriate or agitated behavior. In PTSD as a result of trauma, characteristic symptoms develop, such as repetitive feelings of re-experiencing the trauma, avoidance of trauma reminders, insensitivity and indifference, and persistent signs of hyperarousal (APA, 1994). For a diagnosis of PTSD, a patient must have had symptoms for more than one month associated with clinically significant distress or impairment in social, academic, or other functioning. A traumatic event experienced can occur at a very early age. In particular, children are at risk of physical abuse or may witness domestic violence (Hornor, 2011). Children, due to the circumstances determined by this stage of development, spend most of their time at home with their parents and often cannot avoid situations of violence. Young children have limited coping abilities (De Young et al., 2011).

For a diagnosis of PTSD, a patient must have had symptoms for more than one month associated with clinically significant distress or impairment in social, academic, or other functioning. A traumatic event experienced can occur at a very early age. In particular, children are at risk of physical abuse or may witness domestic violence (Hornor, 2011). Children, due to the circumstances determined by this stage of development, spend most of their time at home with their parents and often cannot avoid situations of violence. Young children have limited coping abilities (De Young et al., 2011).

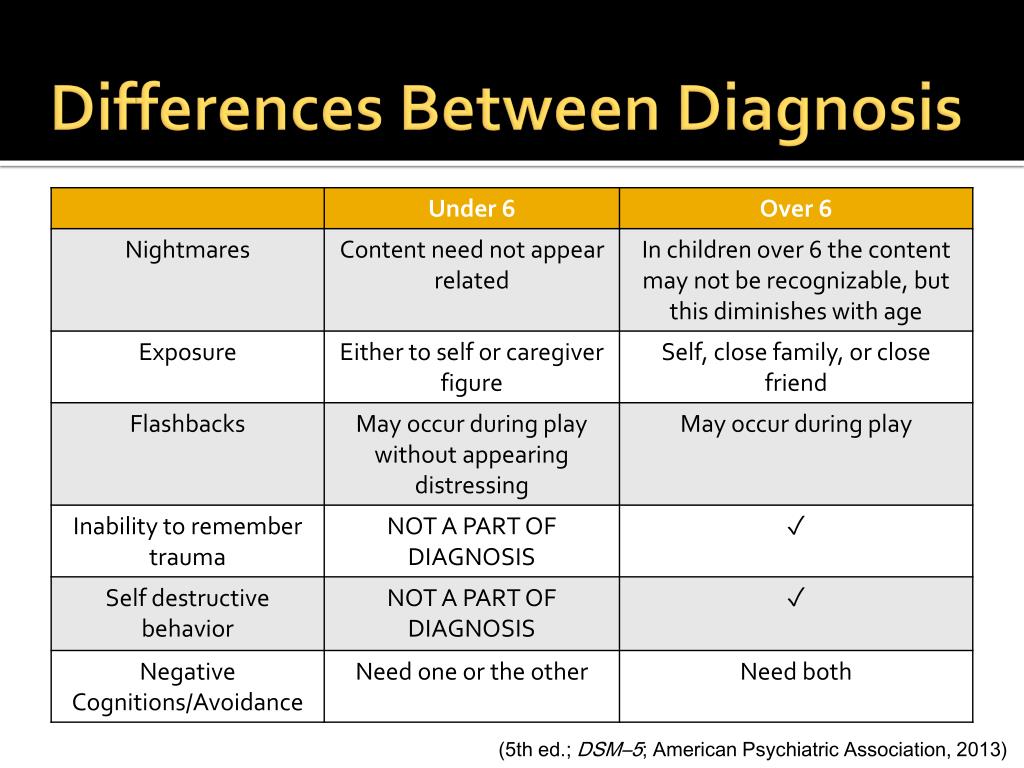

Based on research, it is known that infants and preschool children may present with three traditional clusters of PTSD symptoms: re-experiencing, avoidance, insensitivity, and hyperarousal (Scheeringa et al., 2003). Young children may re-experience trauma in their games, which include violence, repetitiveness, and anxiety where aspects of the trauma are played over and over again (Lieberman and Knorr, 2007). Children may talk about trauma, which is not always accompanied by discomfort, and also suffer from disturbing nightmares, often without awareness of the content. Like older children and adolescents, young children may exhibit intense emotional or physiological responses when internal or external stimuli are reminiscent of trauma. Children are less likely to experience flashbacks or dissociative episodes (De Young et al., 2011).

Children may talk about trauma, which is not always accompanied by discomfort, and also suffer from disturbing nightmares, often without awareness of the content. Like older children and adolescents, young children may exhibit intense emotional or physiological responses when internal or external stimuli are reminiscent of trauma. Children are less likely to experience flashbacks or dissociative episodes (De Young et al., 2011).

In young children who have experienced a traumatic event, hyperarousal may be manifested by disturbed sleep, irritability, temper tantrums, restlessness, constant alertness to danger, overreaction to stimuli, difficulty concentrating, and decreased activity (Pynoos et al., 2009).

Children sometimes show slight or obvious avoidance of conversations, people, places, objects, or situations that remind them of the trauma. Insensitivity may manifest as withdrawal from family and friends, or limitation in play or other activities.

The revision of the DSM-5 currently under consideration includes a revision of the diagnostic criteria in children. The priority is to reflect in the criteria the influence of the child's developmental phases on the manifestations of PTSD. In school-age children and adolescents, Scheeringa et al. (2011) propose to include severe illness or death of a parent or institutionalization in the definition of trauma. Because children may be exposed to a traumatic event, it is not possible to determine the time of onset of PTSD symptoms in such cases.

The priority is to reflect in the criteria the influence of the child's developmental phases on the manifestations of PTSD. In school-age children and adolescents, Scheeringa et al. (2011) propose to include severe illness or death of a parent or institutionalization in the definition of trauma. Because children may be exposed to a traumatic event, it is not possible to determine the time of onset of PTSD symptoms in such cases.

Characteristic symptoms of PTSD according to DSM-IV

- Constant feeling of re-experiencing the traumatic event

- children may play out various aspects of the trauma in games

- Continued uncomfortable dreams about the event: children may experience frightening dreams with unclear content

- Actions/feeling as if the event is repeating:

- sensation of the event returning

- illusions, hallucinations and dissociative episodes of the recurring event

- children may experience a repetition of the event

- Internal and external stimuli reminiscent of the event lead to5: 90.

3

3 - intense psychological discomfort

- physiological response

- Constant avoidance of trauma-related stimuli, indifference and insensitivity, as expressed by 3 or more of the following:

- avoidance of thoughts, feelings, or talking about the traumatic event

- avoidance of activities, places, or people that are reminiscent of the trauma

- inability to remember an important aspect of the traumatic event

- greatly reduced interest in participating in various activities

- avoidance of other people

- limited spectrum affective manifestations or inability to have normal feelings

- feeling of doom and hopelessness of the future

- Permanent symptoms of increased excitement should manifest at least two of the following signs:

- difficulties with falling asleep or maintenance of sleep

- Anger or irritability

- Excessive coughing

- Excessive provision for stimuli

-

Epidemiology and risk factors

The prevalence of PTSD among children and adolescents is not easy to determine.

Blom and Oberink (2012) reviewed 17 studies that reported the prevalence of PTSD among young people who had experienced various traumatic events. It was found that this indicator ranges from 5.3 to 98% depending on the type of event. The highest level was determined among children and adolescents who survived wars, political persecution or repression, and the lowest among those who had serious illnesses or injuries.

Blom and Oberink (2012) reviewed 17 studies that reported the prevalence of PTSD among young people who had experienced various traumatic events. It was found that this indicator ranges from 5.3 to 98% depending on the type of event. The highest level was determined among children and adolescents who survived wars, political persecution or repression, and the lowest among those who had serious illnesses or injuries. Unfortunately, children are at risk of traumatic events in society, schools, and even within their families. Historically, trauma has most commonly been associated with catastrophic events such as terrorism, war, famine, and genocide. Many children live in conditions of violence, danger and poverty. Millions are subject to trauma, abuse and mistreatment. There are also injuries that cannot be prevented, such as serious injury or illness, the loss of a parent through illness, death, imprisonment, or natural disaster.

Children who experience a traumatic event are probably more likely than adults to develop PTSD (Fletcher, 1996).

Even if trauma in childhood did not result in PTSD, there is an increased risk of the disorder as well as other health problems in adults (Widom, 1999; Dube et al., 2003). Copeland et al. (2007) found that in adolescents aged 14-16 years, when compared with children aged 9-13 years, due to a traumatic event, pre-existing anxiety and family distress are significant determinants of the development of PTSD over the next year.

Even if trauma in childhood did not result in PTSD, there is an increased risk of the disorder as well as other health problems in adults (Widom, 1999; Dube et al., 2003). Copeland et al. (2007) found that in adolescents aged 14-16 years, when compared with children aged 9-13 years, due to a traumatic event, pre-existing anxiety and family distress are significant determinants of the development of PTSD over the next year. Suliman et al. (2009) found that adolescents who experienced multiple traumatic events had more PTSD symptoms than those who experienced only one. However, after a single injury, girls were more likely than boys to develop PTSD.

Comorbidity

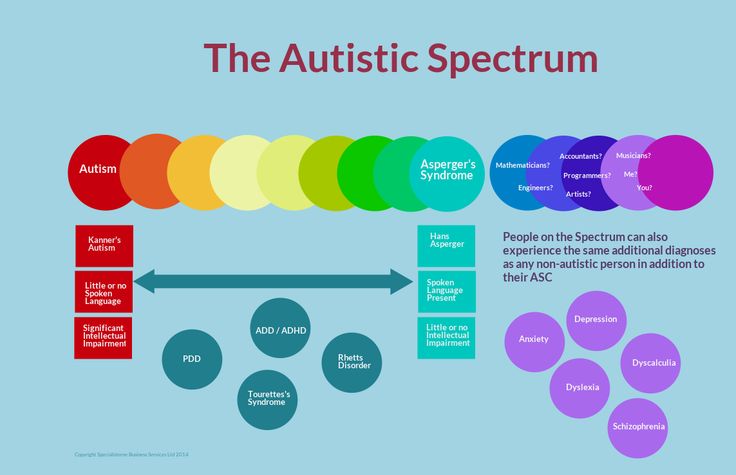

A traumatic event can have a variety of negative consequences in children. Therefore, it is not unusual for PTSD to be associated with other psychiatric disorders. According to De Young et al. (2011), the incidence of comorbid oppositional protest disorder (OPD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) increases with a diagnosis of PTSD.

Depression and anxiety can also occur as a result of a traumatic event in childhood and accompany PTSD (Suliman et al., 2009). Substance abuse disorders are significantly correlated with childhood trauma as well as comorbid PTSD. Khoury et al. (2010) discussed the relationship between PTSD and substance abuse disorders in adults who experienced traumatic events in childhood. Thus, the presence of PTSD symptoms in childhood was more likely to lead to the development of substance abuse disorders in adults compared with traumatic events in childhood without PTSD symptoms.

Seng et al. (2005) studied the comorbidity of PTSD and physical illness in girls (ages: 0-8 and 9-17 years), revealing the relationship between PTSD and a wide range of causes of ill health. Girls with PTSD were likely to have more circulatory problems, infectious and gastrointestinal diseases, and subjective disease conditions such as weakness, muscle pain, and chronic fatigue. The comorbid effect of PTSD extends into adulthood, and PTSD can affect the course and outcome of pregnancy (Seng et al.

, 2011).

, 2011). Landolt et al. (2011) studied comorbidity in PTSD from a specific perspective, namely the influence of PTSD in parents on children's reactions to traumatic events.

In 4.3% of children and 16.5% of parents, the severity of PTSD symptoms was moderate or severe 5-6 weeks after diagnosis of a serious illness or injury, and after one year, these rates were 1.6 and 17.4%, respectively . In children diagnosed with diabetes, the level of PTSD symptoms was the lowest, and those with traumatic injuries were the highest. In children diagnosed with cancer, PTSD symptoms were less common than reported in previous studies (Bruce, 2006). Mothers and fathers of children were found to have a higher level of PTSD symptoms according to all examination methods. The concept of an association was not supported by the study data: PTSD symptoms in parents influenced the recovery of children, but in children they did not affect the recovery of parents.

Diagnosis and treatment

Diagnostic assessment of the impact of trauma on children presents a number of difficulties, since children, especially young children, have limited verbal abilities and it is difficult for them to describe their symptoms (Loeb et al.

, 2011). Parents tend to underestimate their child's symptoms and find it difficult to give accurate and clear information about their child's behavior. Children in care home settings with a large number of caregivers may constitute a separate risk group for child abuse, abandonment and other forms of traumatization, and their anamnestic information is sometimes difficult to confirm (Oswald et al., 2010). In clinical practice, it is very important to have the appropriate tools and/or skills to identify traumatized children in a timely and efficient manner.

, 2011). Parents tend to underestimate their child's symptoms and find it difficult to give accurate and clear information about their child's behavior. Children in care home settings with a large number of caregivers may constitute a separate risk group for child abuse, abandonment and other forms of traumatization, and their anamnestic information is sometimes difficult to confirm (Oswald et al., 2010). In clinical practice, it is very important to have the appropriate tools and/or skills to identify traumatized children in a timely and efficient manner. The Pediatric Symptom Checklist (PSC-17), which is completed by parents, is used as a screening tool for symptoms of emotional and behavioral disorders in primary care settings (Gardner et al., 2007). It has three subscales that assess attention, externalized (destructive behavior) and internalized (anxiety and depression) problems in a child (Gardner et al., 1999). PSC-17 was developed for use in children aged 6 to 18 years in order to more accurately identify these problems (Gardner et al.

, 2007).

, 2007). A large number of screening and diagnostic tools are available to assess trauma in the lives of children and adolescents. Strand et al., (2005) reviewed 25 of these published methods with psychometric properties. The existing methods are different, in some the source of information is the messages of the child or parents, others are performed by professionals. These techniques are considered useful tools and are widely used in mental health and primary care settings. Most of these techniques require experience and skills in working with traumatized children.

Trauma-focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT-T) is the most commonly used treatment for PTSD in children and adolescents. Its proven efficacy is supported by a large database (Silverman et al., 2008). CBT-T was originally developed for use with child survivors of sexual abuse and later adapted for children who have experienced various traumatic events such as domestic violence, street crime, grief, natural disasters (Lang et al.

, 2010). CBT-T is a standardized yet flexible treatment for children diagnosed with PTSD (Cohen et al., 2006). It includes interventions based on cognitive-behavioural, family and humanistic principles. The effectiveness of CBT-T is supported by evidence from studies in school-age children and adolescents (Cohen et al., 2004; Cohen, Mannarino, 1996, 1998; Deblinger et al., 1996; King et al., 2000).

, 2010). CBT-T is a standardized yet flexible treatment for children diagnosed with PTSD (Cohen et al., 2006). It includes interventions based on cognitive-behavioural, family and humanistic principles. The effectiveness of CBT-T is supported by evidence from studies in school-age children and adolescents (Cohen et al., 2004; Cohen, Mannarino, 1996, 1998; Deblinger et al., 1996; King et al., 2000). Scheeringa et al. (2010) studied the efficacy of CBT-T in the treatment of very young children (3 to 6 years of age) who had experienced a traumatic event. Children were randomly assigned to receive 12 sessions of CBT-T or to a no-treatment waiting list (12 weeks). Those who underwent CBT had a significant improvement in PTSD symptoms compared to the waiting list, but no associated symptoms of depression, separation anxiety, ODA, or ADHD. After 12 weeks, all participants, including those in the waiting list, were offered CBT-T. By the 6th month of follow-up, patients continued to show improvement in PTSD symptoms, but symptom scores for comorbid disorders remained mediocre.

A validated successful treatment option for PTSD in adults, adolescents and children is long-term exposure therapy (Rothbaum et al., 2000; Aderka et al., 2011; Gilboa-Schechtman et al., 2010). This modality of therapy is based on the concept of weakening the random links that connect the symptoms of PTSD.

Child-parent psychotherapy has been used as a treatment modality for preschool children who have experienced traumatic events. Joint participation in the sessions of the child, parents and professional in order to improve parenting skills provides the conditions for safe and adequate assistance to the child. Ippen et al. (2011) found that this method was effective in the treatment of preschool children who had suffered multiple traumas. High-risk children showed significant improvement in PTSD symptoms after parent-child psychotherapy and were less likely to meet criteria for PTSD after treatment. The mothers who participated in the therapy also showed improvements in PTSD symptoms and depression.

Researchers at the Cochrane Collaboration (Hetrick et al., 2010) investigated whether a combination of psychological and pharmacological treatments improves therapeutic response in PTSD compared to using each alone. Current treatment guidelines recommend the use of both therapies, especially in cases of resistant PTSD. Despite an exhaustive literature search, only four studies were identified, involving 124 people, that met the inclusion criteria for a Cochrane review, and only one of these was conducted in children and adolescents. For example, Cohen et al. (2007) examined the potential benefit of adding the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor sertraline or placebo to CBT-T to improve symptoms of PTSD in sexually abused children. The study participants were 24 girls aged 10 to 17 years. Evidence supporting the benefit of adding sertraline to psychotherapy was minimal. Subsequently, similar results were obtained in a study by Robb et al. (2010). Thus, there are not enough trials identified to draw a definitive conclusion on the outcome of treating patients with PTSD with a combination of psychological and pharmacological therapies.

Diagnostic assessment of injury

Parents Draw a family tree with the names and ages of parents, siblings, and other relatives. Determine which of them lives with the child. Which of the relatives does the child visit, who lives there? Does the child have contact with both parents? If not, why, how long, since when have the parents not been in contact with each other? Has anything changed in your child's life lately?

- serious illness, injury or death of parents/relatives

- divorce of parents

- departure from home of one of the parents

- military service of one of the parents

- imprisonment of one of the parents

Have you contacted child care before? If yes, why? Have parents been subjected to legal action? If yes, why? Does either parent have a history of sexual or physical abuse, abuse, abandonment, or caregiving in childhood? Are there concerns about sexual, physical or emotional abuse for the child or other children in the family? Has the child been sexually or physically abused before? Does either parent abuse alcohol or drugs? Has either parent been previously contacted by mental health services for a mental disorder or mental retardation? Is there a family history of domestic violence? If yes, has the child been abused? Did the parents have concerns about anyone in the family or any of the neighbors/neighborly children? If yes, why?

Child Does anything bother or annoy the child? Is the child afraid to be at home? At school? Among neighbors? If yes, why? Is the child sad? If yes, why? Using the words of the child, ask: someone touched something, touched, did he damage his intimate places.

Ask the teenager if anyone had sexual contact with him/her without his/her will, or touched him/her in a sexual way when he/she did not want it. What happens if a child creates problems? Does anyone beat him, push him, punish him? If yes, how exactly? What happens when mother and father fight? Did the child see that someone beat, pushed the mother or father?

Ask the teenager if anyone had sexual contact with him/her without his/her will, or touched him/her in a sexual way when he/she did not want it. What happens if a child creates problems? Does anyone beat him, push him, punish him? If yes, how exactly? What happens when mother and father fight? Did the child see that someone beat, pushed the mother or father? Practical relevance

It is important to understand that children, even very young children, can develop symptoms of PTSD or other mental and behavioral disorders as a result of trauma. If diagnostic screening results indicate a history of traumatic event, especially if there is more than one, consideration should be given to referral to a mental health professional or therapist trained in working with traumatized children and adolescents. If child abuse is detected, it is advisable to inform the child care services. Before discharging a child, make sure that the child safety plan meets the requirements of the child welfare services.

If emotional and/or behavioral complaints are presented, the patient should be assessed for past trauma. The child and parents should be asked about domestic violence, sexual abuse, parenting practices, and physical abuse. It is recommended to find out if any serious illness or loss of a loved one has occurred. It is important to remember that PTSD can be accompanied by ADHD, OPD, depression and anxiety. Trauma children may not be the only family members in need of mental health care. If screening indicates that parents or loved ones have experienced trauma, they should also be briefly assessed. Is it useful to find out if any of the parents sought mental health care in the past because of abuse or loss? Parents should be informed about how their stress can affect the child.

Anything that could harm a child should be eliminated, such as domestic violence, sexual and physical abuse. What cannot be eliminated must be minimized, including through therapy, such as the consequences of street crime, loss or serious illness or injury.

Prepared by Stanislav Kostyuchenko

Read the original text of the document at www.medscape.com0001

PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) is a mental illness that occurs several weeks or months after a severe life-threatening event - military operations (both soldiers and civilians), captivity, man-made disasters, attacks, rape, natural disasters, terrorist acts.

The diagnosis and treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder is carried out by a psychotherapist.

The disorder may begin weeks or years after the traumatic experience. Traumatic neurosis is a person's "stuck" in an extreme situation, he constantly mentally returns to it and cannot forget.

The criteria for PTSD are as follows:

- The person was in a situation threatening life or health, was a participant or even just a witness.

- During the event, he experienced helplessness, horror, fear.

- The situation has remained in the past, but the patient with PTSD constantly experiences it - mentally, in nightmares, returns to it again and again. He does not share his experiences with those around him, he keeps everything in himself.

Important

A person is not able to objectively assess his state of health and cope with emotions. He begins to react inadequately to real events, does not perceive new information, tries to isolate himself from communication, reacts sharply to criticism and jokes.

A person becomes a shadow of his former self, because he does not exist in the present. Referring to a psychotherapist is the only effective way to cope with a traumatic disorder.

Features of the development and diagnosis of PTSD

The breakdown is often preceded by a latent period of relative calm. After an injury, a person can lead a normal life for six months or even longer. In PTSD, the signs that signal the disease are as follows:

- experiences, anxiety and tension appear, which are associated with a traumatic situation.

They are repeated at any time of the day: at night - in nightmares, during the day - in thoughts, memories;

They are repeated at any time of the day: at night - in nightmares, during the day - in thoughts, memories; - there are flashbacks - a person is "transferred" to a past situation, re-experiencing it very vividly and ceases to orient himself in reality, the state is similar to clouding of consciousness. Last from a few seconds to several hours;

- people withdraw into themselves, lose interest in work and communication. At the same time, he can react to innocent remarks and jokes with impulsive, cruel beatings.

Post-traumatic stress disorder is characterized by agitation, aggression, increased caution, and suspicion. A person avoids any mention of what happened (actions, places, conversations), becomes anxious and emotionally retarded.

Important

Internal tension leads to fatigue, apathy, emptiness. Memory and attention deteriorate. A person becomes distracted, which leads to constant mistakes at work. Often this condition is accompanied by depressed mood (depression), thoughts of suicide.

In post-traumatic stress disorder, symptoms may include complaints of:

- insomnia or superficial sleep;

- increased sweating;

- heartbeat, interruptions in the work of the heart;

- fatigue, hypersensitivity.

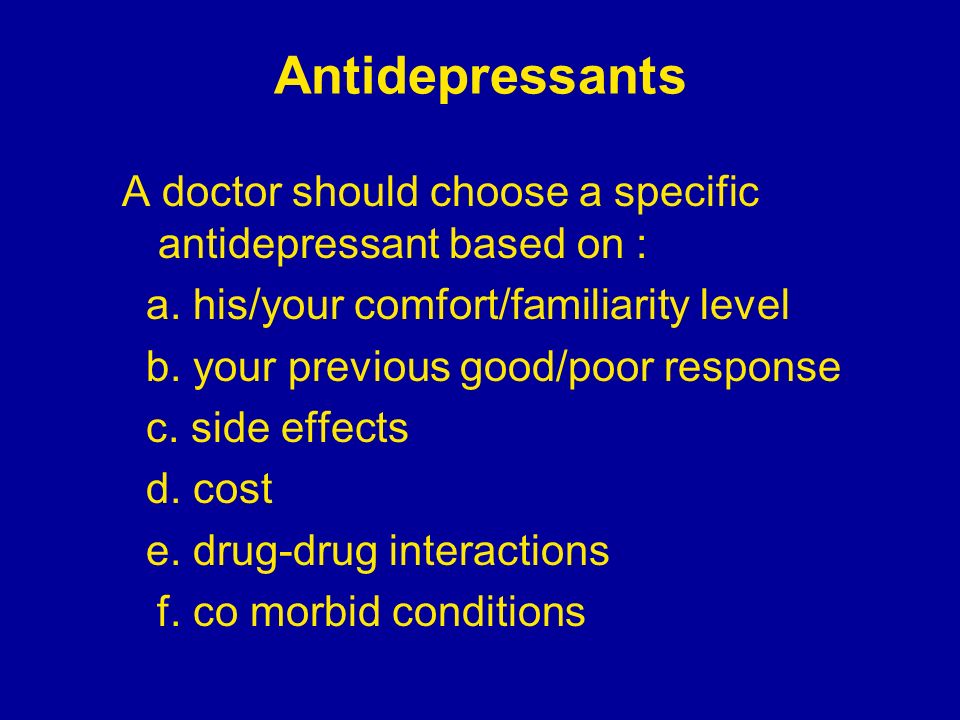

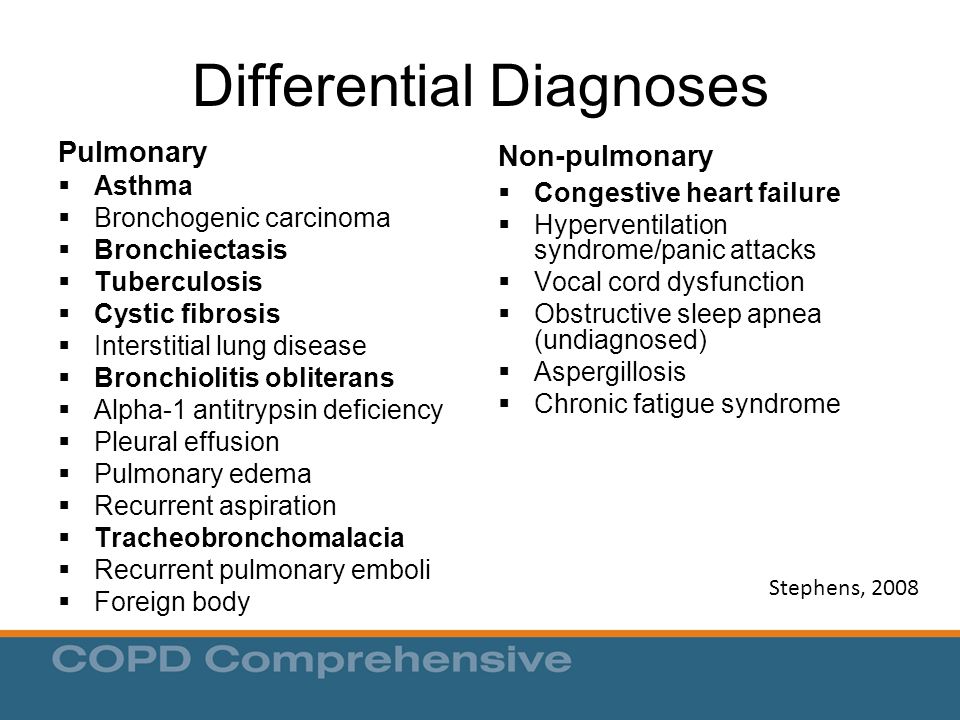

A psychotherapist diagnoses a disease at an individual consultation - collects an anamnesis (life history), evaluates complaints, tries to find out the causes of the disorder. Psychic trauma can trigger the development of other mental illnesses - severe depression, endogenous diseases. For differential diagnosis, a pathopsychological study is also used (performed by a clinical psychologist).

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) treatment

Psychotherapy sessions are the basis of recovery. They help the patient accept and process the traumatic experience in order to move on. Treatment for PTSD includes:

- Individual psychotherapy.

- Medical correction of symptoms (anxiety, depression, irritability, sleep problems).

- biofeedback therapy.

- Group therapy.

With PTSD, the disease can be overcome with the help of cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy. The psychotherapist teaches the patient not to run away from the traumatic situation, helps to increase self-control and cope with painful memories.

BFB therapy (biofeedback therapy) is a relaxation technique that relieves internal tension and reduces muscle stiffness. The patient learns to control breathing, pulse, pressure. He can use these techniques at an unfavorable moment to regain control over his condition.

Biofeedback Therapy is a modern, non-pharmacological method of treating mental disorders that helps patients gain control over their bodies.

Group therapy is based on the support and interaction of people who have also experienced various traumatic situations. At the sessions, they learn to express their thoughts, show emotions and look with hope into the future.