History insane asylum

History of Psychiatric Hospitals • Nursing, History, and Health Care • Penn Nursing

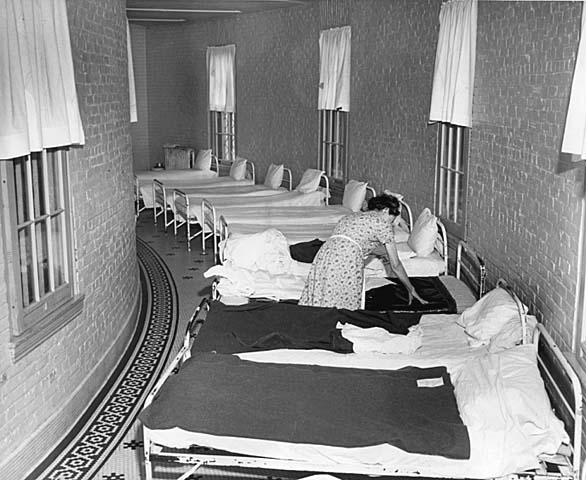

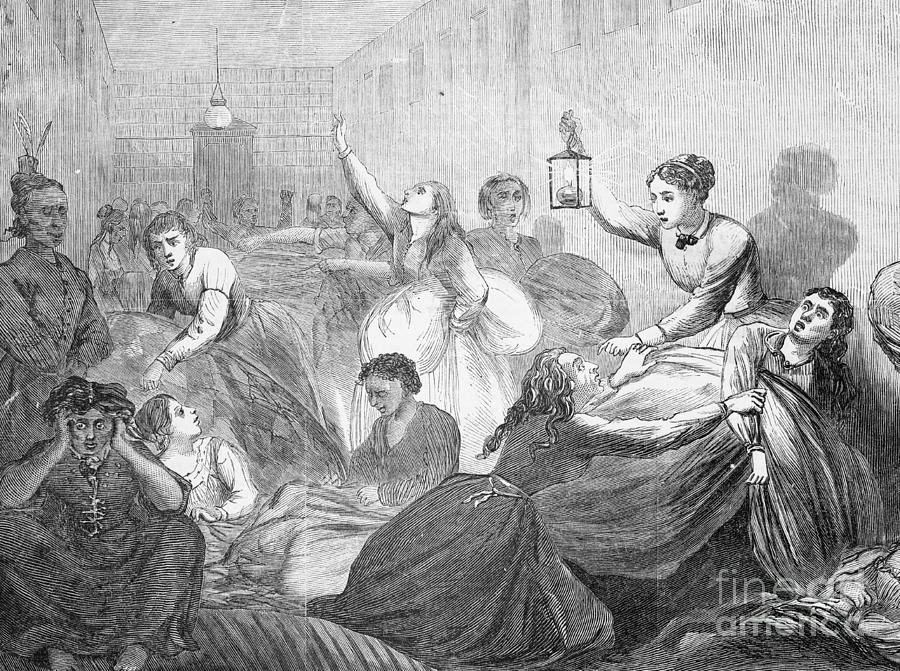

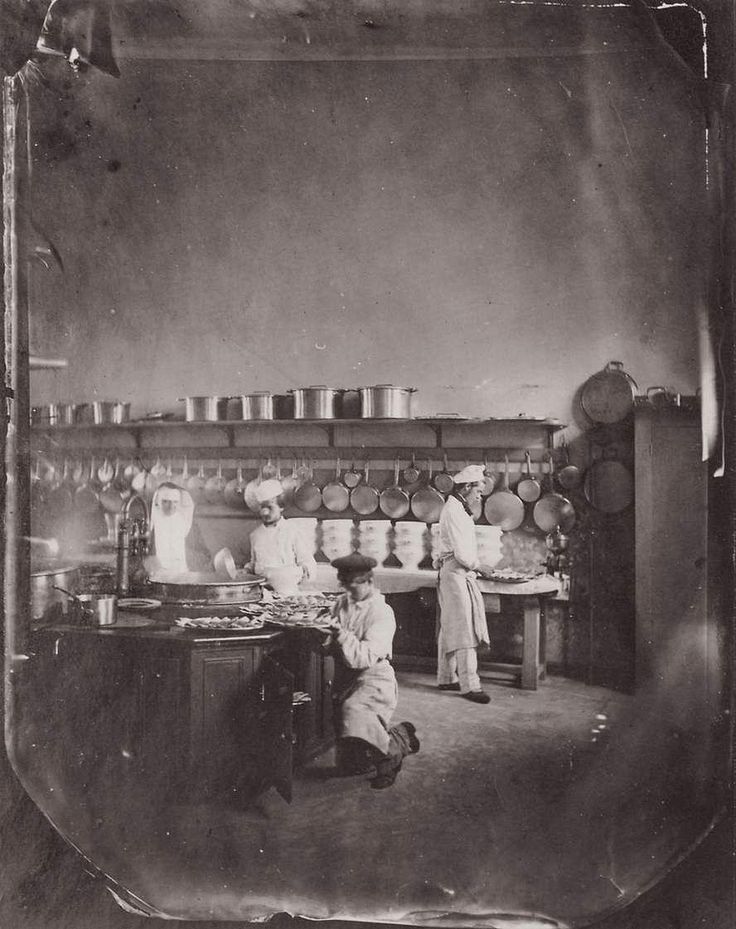

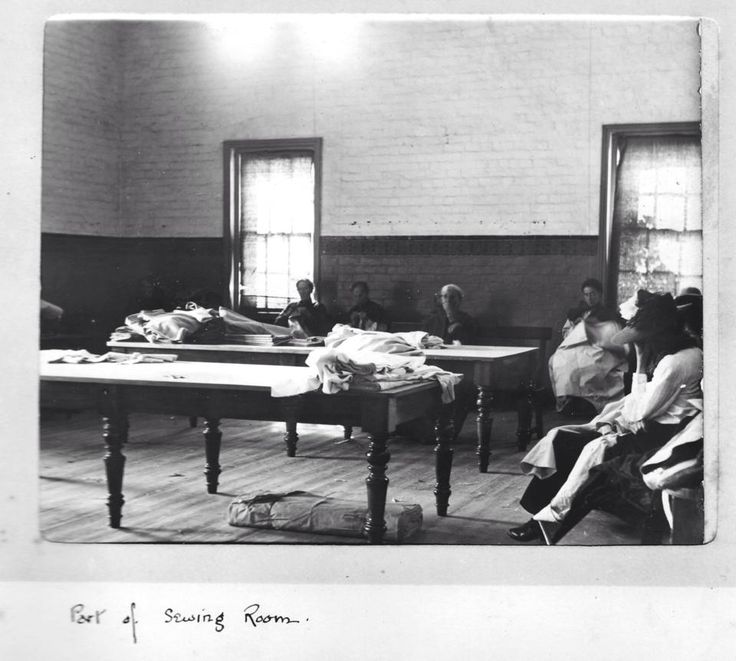

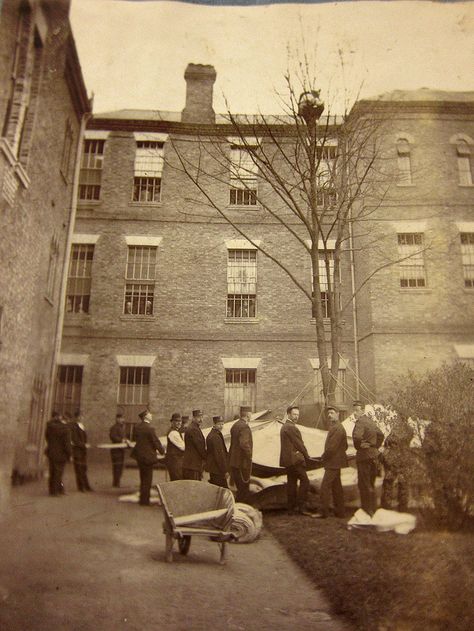

Philadelphia Hospital for the Insane, Philadelphia, PA c. 1900The history of psychiatric hospitals was once tied tightly to that of all American hospitals. Those who supported the creation of the first early-eighteenth-century public and private hospitals recognized that one important mission would be the care and treatment of those with severe symptoms of mental illnesses. Like most physically sick men and women, such individuals remained with their families and received treatment in their homes. Their communities showed significant tolerance for what they saw as strange thoughts and behaviors. But some such individuals seemed too violent or disruptive to remain at home or in their communities. In East Coast cities, both public almshouses and private hospitals set aside separate wards for the mentally ill. Private hospitals, in fact, depended on the money paid by wealthier families to care for their mentally ill husbands, wives, sons, and daughters to support their main charitable mission of caring for the physically sick poor.

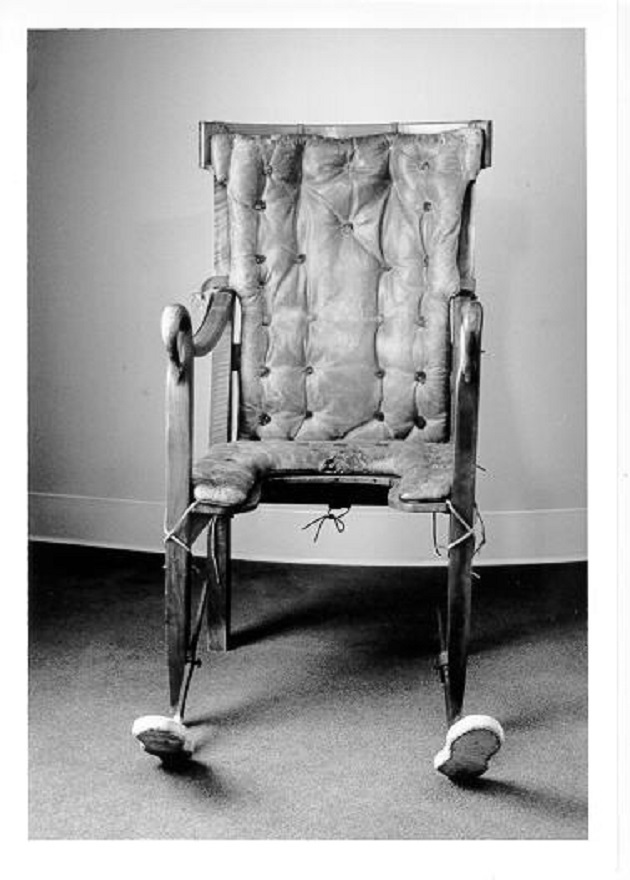

But the opening decades of the nineteenth-century brought to the United States new European ideas about the care and treatment of the mentally ill. These ideas, soon to be called “moral treatment,” promised a cure for mental illnesses to those who sought treatment in a very new kind of institution—an “asylum.” The moral treatment of the insane was built on the assumption that those suffering from mental illness could find their way to recovery and an eventual cure if treated kindly and in ways that appealed to the parts of their minds that remained rational. It repudiated the use of harsh restraints and long periods of isolation that had been used to manage the most destructive behaviors of mentally ill individuals. It depended instead on specially constructed hospitals that provided quiet, secluded, and peaceful country settings; opportunities for meaningful work and recreation; a system of privileges and rewards for rational behaviors; and gentler kinds of restraints used for shorter periods.

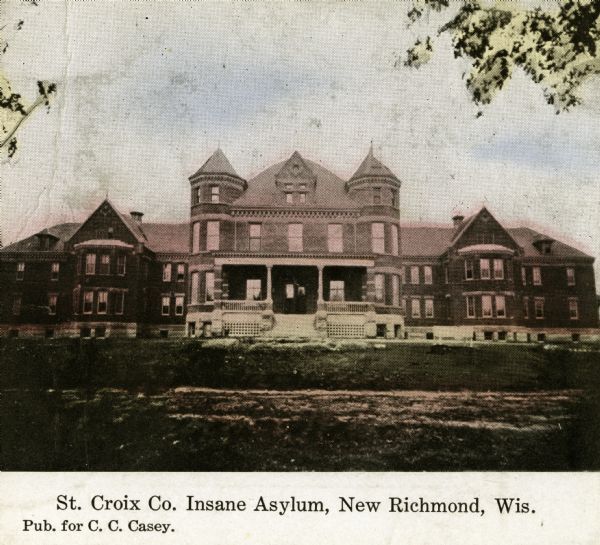

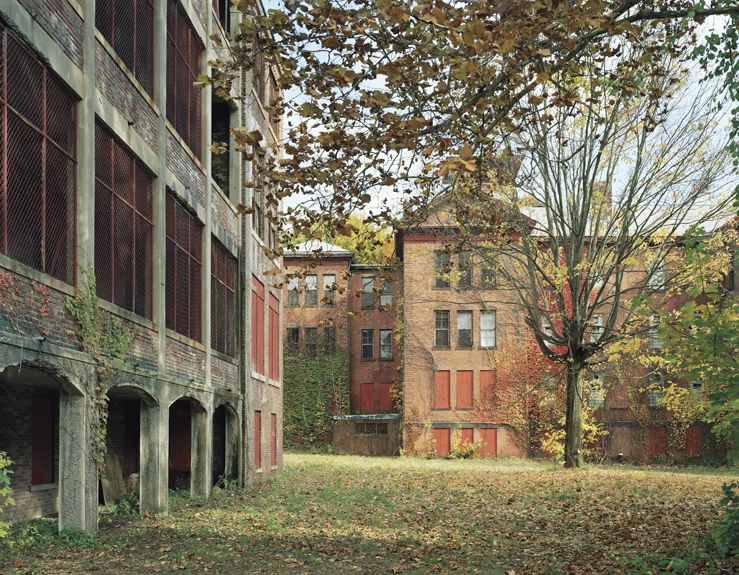

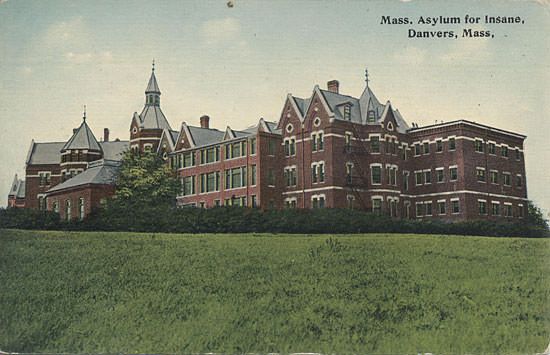

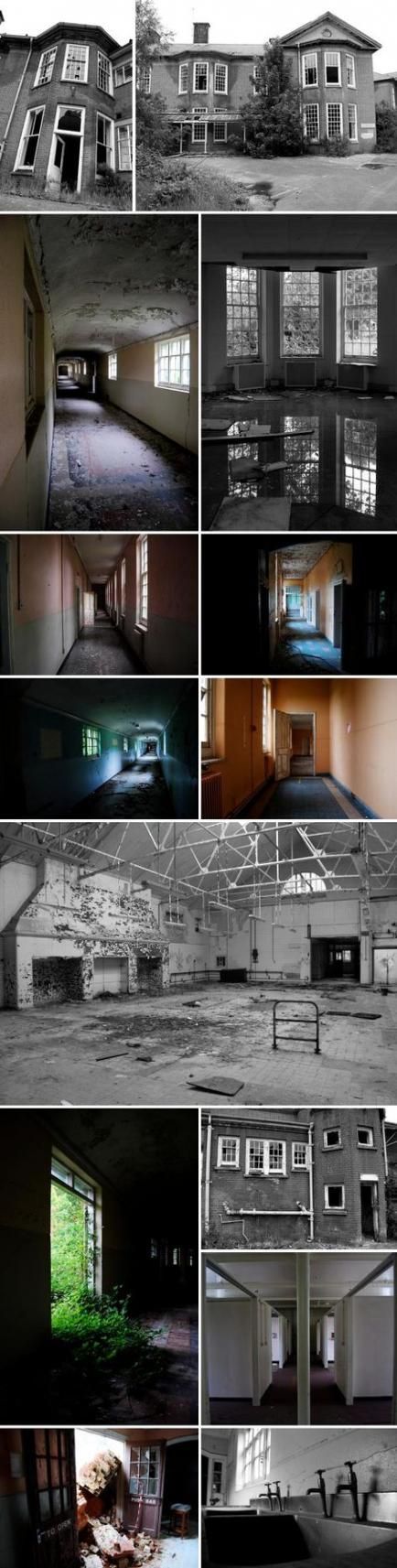

Many of the more prestigious private hospitals tried to implement some parts of moral treatment on the wards that held mentally ill patients. But the Friends Asylum, established by Philadelphia’s Quaker community in 1814, was the first institution specially built to implement the full program of moral treatment. The Friends Asylum remained unique in that it was run by a lay staff rather than by medical men and women. The private institutions that quickly followed, by contrast, chose physicians as administrators. But they all chose quiet and secluded sites for these new hospitals to which they would transfer their insane patients. Massachusetts General Hospital built the McLean Hospital outside of Boston in 1811; the New York Hospital built the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum in Morningside Heights in upper Manhattan in 1816; and the Pennsylvania Hospital established the Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital across the river from the city in 1841. Thomas Kirkbride, the influential medical superintendent of the Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital, developed what quickly became known as the “Kirkbride Plan” for how hospitals devoted to moral treatment should be built and organized. This plan, the prototype for many future private and public insane asylums, called for no more than 250 patients living in a building with a central core and long, rambling wings arranged to provide sunshine and fresh air as well as privacy and comfort.

This plan, the prototype for many future private and public insane asylums, called for no more than 250 patients living in a building with a central core and long, rambling wings arranged to provide sunshine and fresh air as well as privacy and comfort.

Occupational Therapy Group, Philadelphia Hospital for Mental Diseases, Thirty-fourth and Pine StreetsWith both the ideas and the structures established, reformers throughout the United States urged that the treatment available to those who could afford private care now be provided to poorer insane men and women. Dorothea Dix, a New England school teacher, became the most prominent voice and the most visible presence in this campaign. Dix travelled throughout the country in the 1850s and 1860s testifying in state after state about the plight of their mentally ill citizens and the cures that a newly created state asylum, built along the Kirkbride plan and practicing moral treatment, promised. By the 1870s virtually all states had one or more such asylums funded by state tax dollars.

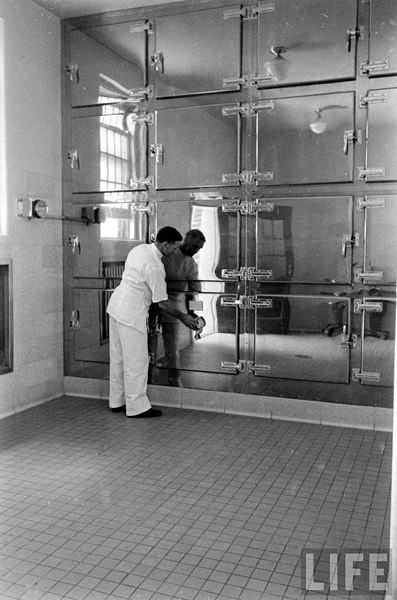

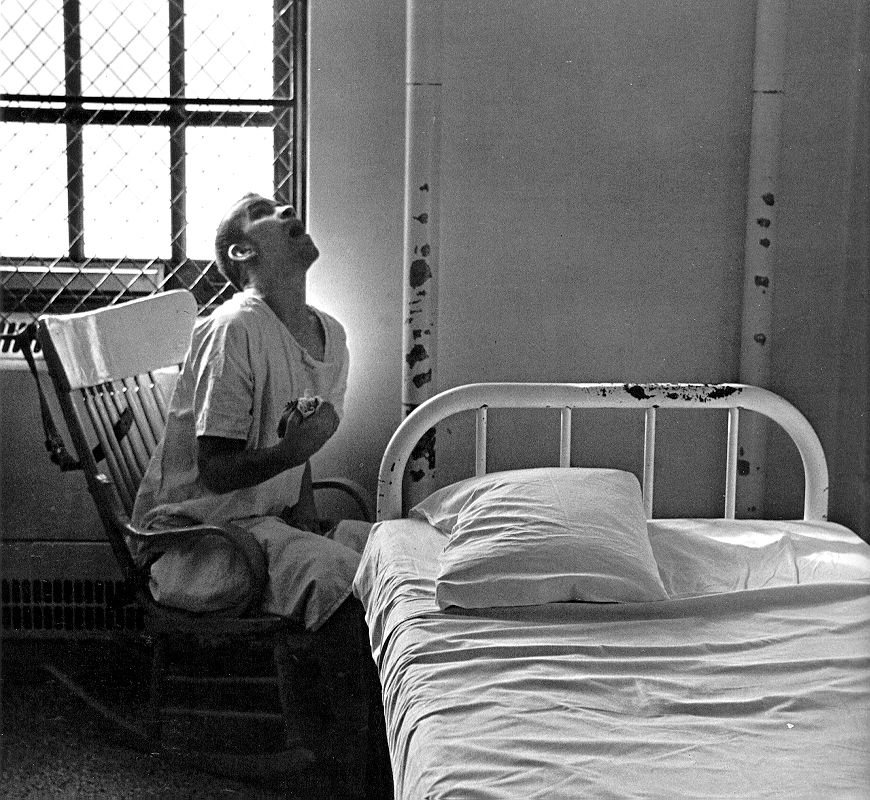

By the 1890s, however, these institutions were all under siege. Economic considerations played a substantial role in this assault. Local governments could avoid the costs of caring for the elderly residents in almshouses or public hospitals by redefining what was then termed “senility” as a psychiatric problem and sending these men and women to state-supported asylums. Not surprisingly, the numbers of patients in the asylums grew exponentially, well beyond both available capacity and the willingness of states to provide the financial resources necessary to provide acceptable care. But therapeutic considerations also played a role. The promise of moral treatment confronted the reality that many patients, particularly if they experienced some form of dementia, either could not or did not respond when placed in an asylum environment.

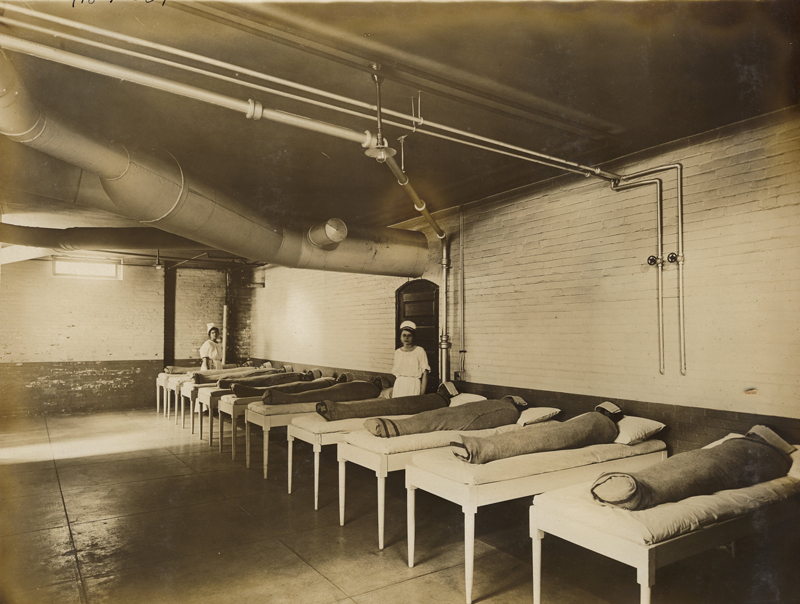

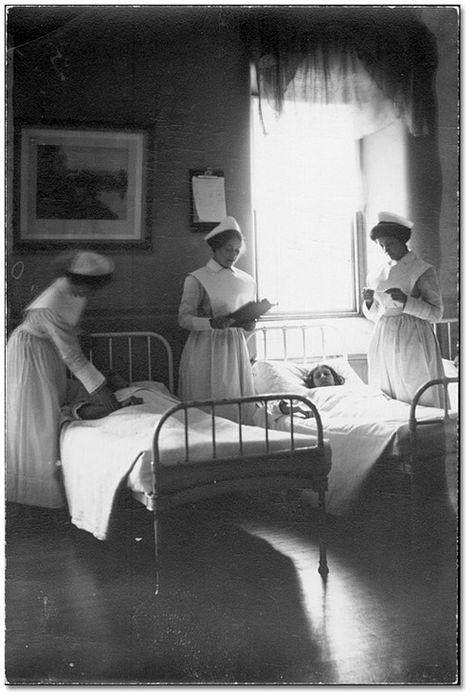

Philadelphia Hospital for the Insane, Philadelphia, PA c. 1900The medical superintendents of asylums took such critiques seriously. Their most significant effort to improve the quality of the care of their patients was the establishment of nurses’ training schools within their institutions. Nurses’ training schools, first established in American general hospitals in the 1860s and 1870s, had already proved critical to the success of these particular hospitals, and asylum superintendents hoped they would do the same for their institutions. These administrators took an unusual step. Rather than following an accepted European model in which those who trained as nurses in psychiatric institutions sat for a separate credentialing exam and carried a different title, they insisted that all nurses who trained in their psychiatric institutions sit for the same exam as those who trained in general hospitals and carry the same title of “registered nurse.” Leaders of the nascent American Nurses Association fought hard to prevent this, arguing that those who trained in asylums lacked the necessary medical, surgical, and obstetric experiences common to general-hospital-trained nurses.

Their most significant effort to improve the quality of the care of their patients was the establishment of nurses’ training schools within their institutions. Nurses’ training schools, first established in American general hospitals in the 1860s and 1870s, had already proved critical to the success of these particular hospitals, and asylum superintendents hoped they would do the same for their institutions. These administrators took an unusual step. Rather than following an accepted European model in which those who trained as nurses in psychiatric institutions sat for a separate credentialing exam and carried a different title, they insisted that all nurses who trained in their psychiatric institutions sit for the same exam as those who trained in general hospitals and carry the same title of “registered nurse.” Leaders of the nascent American Nurses Association fought hard to prevent this, arguing that those who trained in asylums lacked the necessary medical, surgical, and obstetric experiences common to general-hospital-trained nurses. But they could not prevail politically. It would be decades before American nursing leaders had the necessary social and political weight to ensure that all training school graduates—irrespective of the site of their training—had comparable clinical and classroom experiences.

But they could not prevail politically. It would be decades before American nursing leaders had the necessary social and political weight to ensure that all training school graduates—irrespective of the site of their training—had comparable clinical and classroom experiences.

Byberry State Hospital, Philadelphia, PA c. 1920It is, at present, hard to assess the impact of nurses’ training schools on the actual care of patients in psychiatric institutions. In some larger public institutions, the students worked only on particular wards. It does seem that they had a more substantive impact on the care of patients in much smaller and private psychiatric hospitals where they had more contact with more patients. Still, it may be that their most enduring contribution was opening the practice of professional nursing to men. Training schools in asylums, unlike those in general hospitals, actively welcomed men. Male students found places either in schools that also accepted women or in separate schools formed just for them.

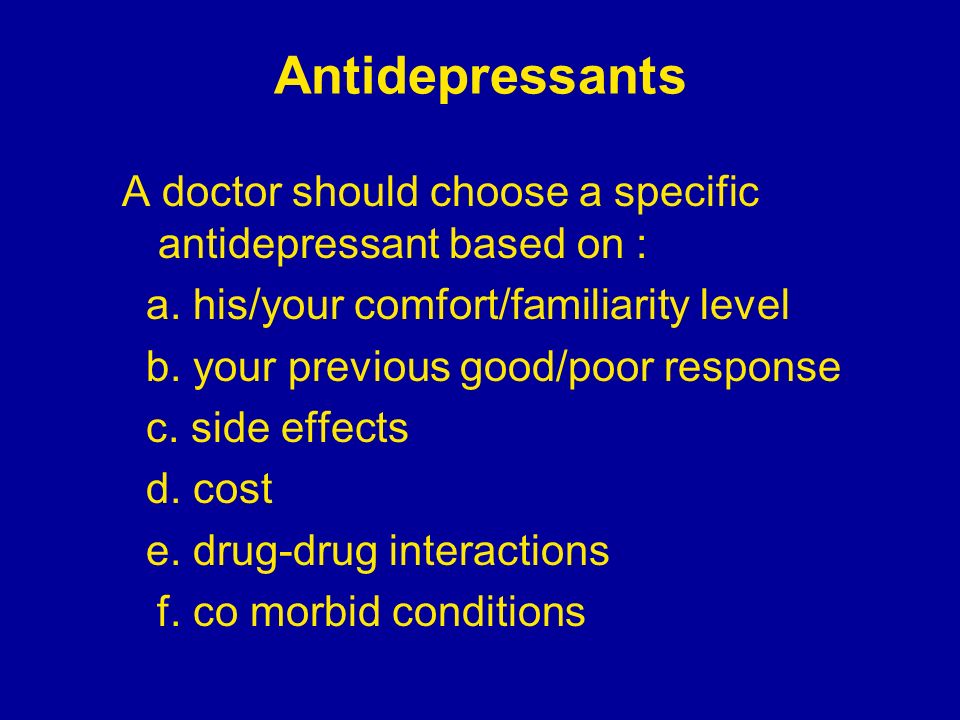

Training schools for nurses, however, could not stop the assault on psychiatric asylums. The economic crisis of the 1930s drastically cut state appropriations, and World War II created acute shortages of personnel. Psychiatrists, themselves, began looking for other practice opportunities by more closely identifying with general, more reductionistic, medicine. Some established separate programs—often called “psychopathic hospitals”—within general hospitals to treat patients suffering from acute mental illnesses. Others turned to the early-twentieth-century’s new Mental Hygiene Movement and created outpatient clinics and new forms of private practice focused on actively preventing the disorders that might result in a psychiatric hospitalization. And still others experimented with new forms of therapies that posited brain pathology as a cause of mental illness in the same way that medical doctors posited pathology in other body organs as the cause of physical symptoms: they tried insulin and electric shock therapies, psychosurgery, and different kinds of medications.

By the 1950s, the death knell for psychiatric asylums had sounded. A new system of nursing homes would meet the needs of vulnerable elders. A new medication, chlorpromazine, offered hopes of curing the most persistent and severe psychiatric symptoms. And a new system of mental health care, the community mental health system, would return those suffering from mental illnesses to their families and their communities.

Today, only a small number of the historic public and private psychiatric hospitals exist. Psychiatric care and treatment are now delivered through a web of services including crisis services, short-term and general-hospital-based acute psychiatric care units, and outpatient services ranging from twenty-four-hour assisted living environments to clinics and clinicians’ offices offering a range of psychopharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatments. The quality and availability of these outpatient services vary widely, leading some historians and policy experts to wonder if “asylums,” in the true sense of the word, might be still needed for the most vulnerable individuals who need supportive living environments.

Patricia D’Antonio is Carol E. Ware Professor in Mental Health Nursing, Chair, Department of Family and Community Health, Director, Barbara Bates Center for the Study of the History of Nursing, and Senior Fellow, Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics.

Diseases of the Mind: Highlights of American Psychiatry through 1900

1752 1773 1792 1817 1824

The mentally ill in early American communities were generally cared for by family members, however, in severe cases they sometimes ended up in almshouses or jails. Because mental illness was generally thought to be caused by a moral or spiritual failing, punishment and shame were often handed down to the mentally ill and sometimes their families as well. As the population grew and certain areas became more densely settled, mental illness became one of a number of social issues for which community institutions were created in order to handle the needs of such individuals collectively.

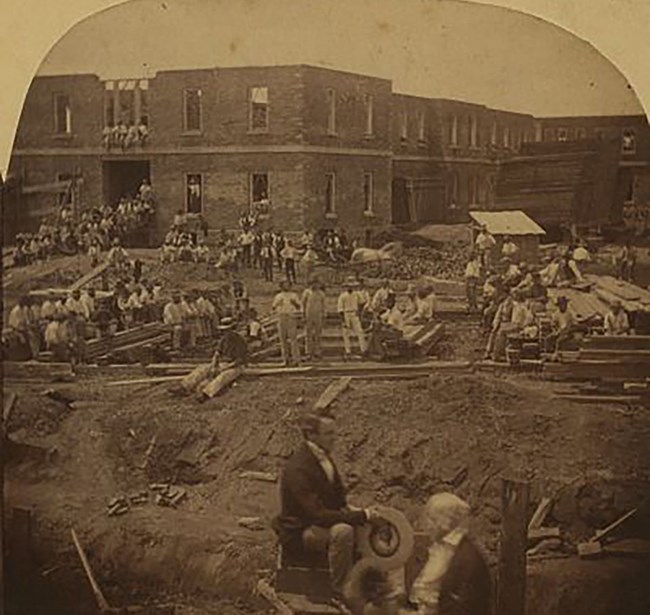

1752. The Quakers in Philadelphia were the first in America to make an organized effort to care for the mentally ill. The newly-opened Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia provided rooms in the basement complete with shackles attached to the walls to house a small number of mentally ill patients. Within a year or two, the press for admissions required additional space, and a ward was opened beside the hospital. Eventually, a new Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane was opened in a suburb in 1856 and remained open under different names until 1998.

Read more:

Code of rules and regulations for the government of those employed in the care of the patients of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, near Philadelphia. (Philadelphia, 1850). //resource.nlm.nih.gov/101560452

An appeal to the citizens of Pennsylvania for means to provide additional accomodations for the insane. (Philadelphia, 1854). //resource.nlm.nih.gov/101560453

George B. Wood. Proceedings on the occasion of laying the corner stone of the new Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane at Philadelphia. (Philadelphia, 1856). //resource.nlm.nih.gov/68131220R

Wood. Proceedings on the occasion of laying the corner stone of the new Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane at Philadelphia. (Philadelphia, 1856). //resource.nlm.nih.gov/68131220R

1773. To deal with mentally disturbed people who were causing problems in the community, the Virginia legislature provided funds to build a small hospital in Williamsburg. Over the years, the hospital grew in size as needs arose but remained within the historic area of the city until the mid-20th century, when a new hospital was built in a suburb. Today it is the Eastern State Hospital.

1792. The New York Hospital opened a ward for "curable" insane patients. In 1808, a free-standing medical facility was built nearby for the humane treatment of the mentally ill, and in 1821 a larger facility called the Bloomingdale Asylum was built in what is now the Upper West Side. In 1894, it was moved further away, to the suburb of White Plains and is currently under operation as the Payne-Whitney Westchester Hospital, a Division of the New York Hospital-Cornell Weill Medical Center.

Read more:

Address of the Governors of the New-York Hospital, to the public relative to the Asylum for the Insane at Bloomingdale (New York, 1821). //resource.nlm.nih.gov/68130900R

1817. In Philadelphia, The Asylum for the Relief of Persons Deprived of the Use of their Reason was opened under Quaker auspices as a private mental hospital. It continues to serve this function to this day as the Friends Hospital.

Read more:

Account of the present state of the Asylum for the Relief of Persons Deprived of the Use of their Reason. (Philadelphia, 1816). //resource.nlm.nih.gov/2546074R

Further information of the progress of the Asylum for the Relief of Persons Deprived of the Use of their Reason. (Philadelphia, 1818). //resource.nlm.nih.gov/2554041R

1824. The Eastern Lunatic Asylum was opened in Lexington, Kentucky, as the first mental institution west of the Appalachian Mountains. It still operates today under the name, Eastern State Hospital.

It still operates today under the name, Eastern State Hospital.

By 1890, every state had built one or more publicly supported mental hospitals, which all expanded in size as the country’s population increased. By mid-20th century, the hospitals housed over 500,000 patients but began to diminish in size as new methods of treatment became available.

‹Previous Next ›

| Diseases of the Mind Home | Introduction | Early Psychiatric Hospitals & Asylums | Benjamin Rush, M.D,: "The Father of American Psychiatry" |

| The 1840s: Early Professional Institutions & Lay Activism | 19th-Century Psychiatrists of Note | 19th-Century Psychiatric Debates | Credits |

story of a patient and an employee of a psychiatric hospital from Bashkiria

In general, it is not customary to talk about institutions of this type, and even more so about the people who were treated in them. Most often, people who have been there live with the stigma for the rest of their lives.

About life in a psychiatric hospital, about who works and is treated there, we learned from our heroes - an employee and patient of one of the bedlams of the republic.

Only not in the children's department

Meet Elena. She worked in one of the republican psychiatric hospitals for about a year as a nurse. Now Elena is on maternity leave, she will soon go to work, but she does not want to lose her place. That is why she asked to publish her story anonymously. Therefore, to be honest, the name of our heroine is fictitious, but her story is not.

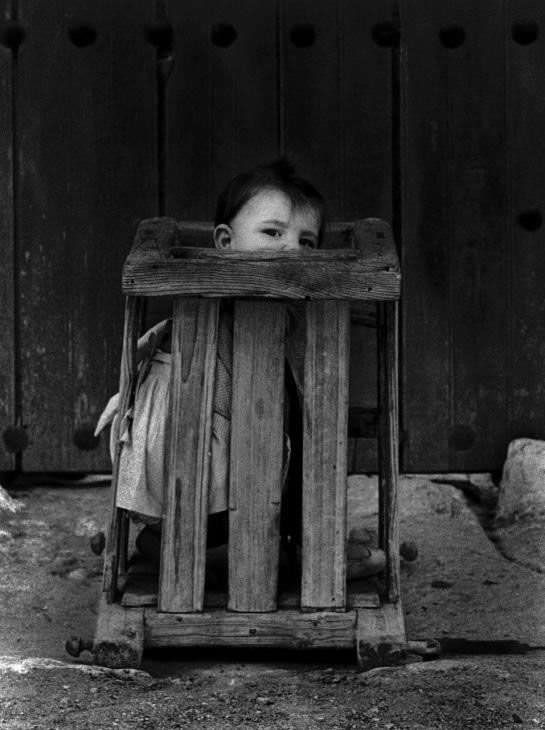

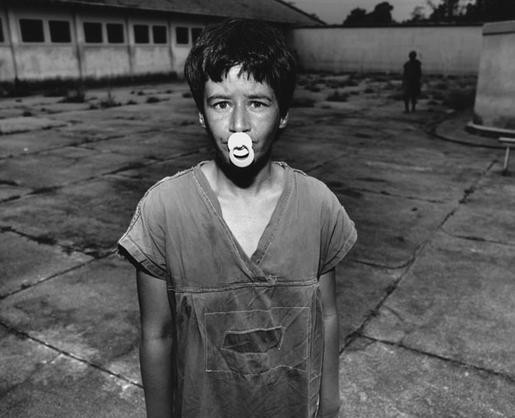

– I have to go to work in a year, but I will return there only if I am not sent to the children's department. It's pretty rough in there. Already hardened people are working. You see, their soul does not hurt for their patients. They can raise their voice to the child, grab him by the hand, put him out into the corridor. All the time they say that with “these” you need to be tough, strict, you can’t mumble, show pity.

In this case, “these” mean children from 7 to 15 years old with completely different diagnoses - schizophrenia, autism, behavioral disorders, guys with suicidal tendencies. Of course, there are violent ones. There was, for example, a boy who threw himself with an ax at his adoptive parents. There was another one with schizophrenia from a very good, wealthy family. It was evident that the child was smart, well-read, but he was tormented by obsessions. He became very aggressive and sexually preoccupied. He constantly wanted sex, talked about it right and left, molested his six-year-old sister, and eventually thundered towards us. One girl had the flu as a child. She recovered, but in terms of mental development she remained the same seven-year-old child. She was very aggressive, constantly talking to someone invisible, rushing at people.

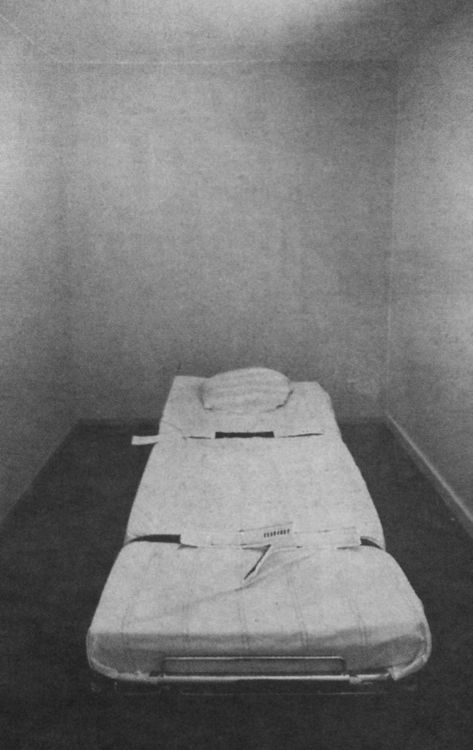

After each attack, the girl was tied to the bed, she screamed and cried a lot, hit herself in the forehead with her fist - they did not have time to treat, as a result, a huge lump formed there, which did not go away. In general, such behavior is not uncommon. A little later, a guy came to us who constantly whipped himself in the face. By the way, they were tied to the bed with ordinary ropes, there are no straitjackets there. I was even taught how to tie properly. There are no orderlies there either, none of the peasants will accept such a salary. Therefore, women and grandmothers follow the order and discipline.

In general, such behavior is not uncommon. A little later, a guy came to us who constantly whipped himself in the face. By the way, they were tied to the bed with ordinary ropes, there are no straitjackets there. I was even taught how to tie properly. There are no orderlies there either, none of the peasants will accept such a salary. Therefore, women and grandmothers follow the order and discipline.

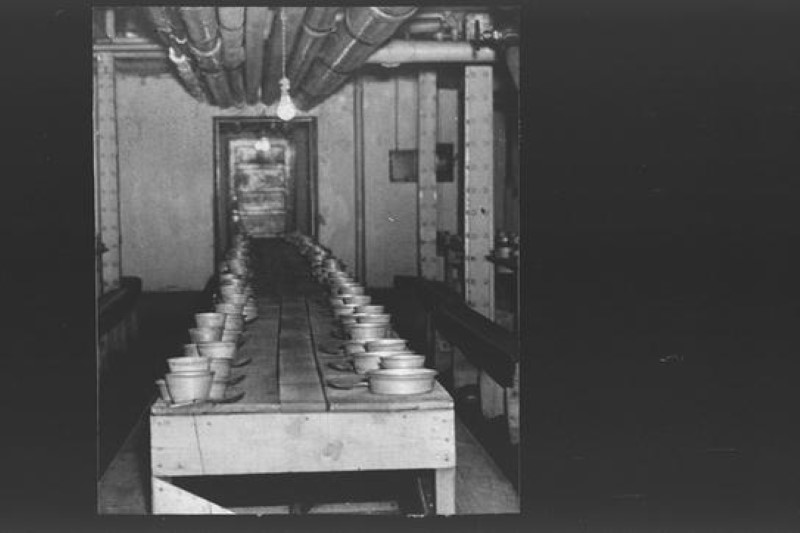

There is absolutely nothing for children to do there. Rise at 8 am. They are drugged and sent under supervision for breakfast. So all day, until nine in the evening - food, room, medicine. The only exceptions are TV viewing and games room. But not all children have access to these places, but only those who like the staff. You can’t keep anything from personal things - notebooks, books can be allowed, but with a stretch, but phones and players, tablets are taboo. Basically, phones are banned because children call their parents endlessly, and then they complain that we do not control them.

There are visiting hours for parents, you can come at least every day, but there are few such cases, because most of them are from other cities. Some don't come at all.

I can say that I would never send my child to such a place. It’s bad for children there, no one takes special care of them, they are rudely ordered when to sleep, when to eat, no one tries to talk affectionately.

You get used to their invisible interlocutors

The hospital has a lot of departments. The calmest thing is for conscripts and officers who are undergoing rehabilitation after serving in hot spots. The coolest thing is the forensic psychiatric department. Everyone is trying to get a job there because of the good salary. This office is located behind a high fence with barbed wire. As you understand, it is for those who have committed a crime and are declared insane.

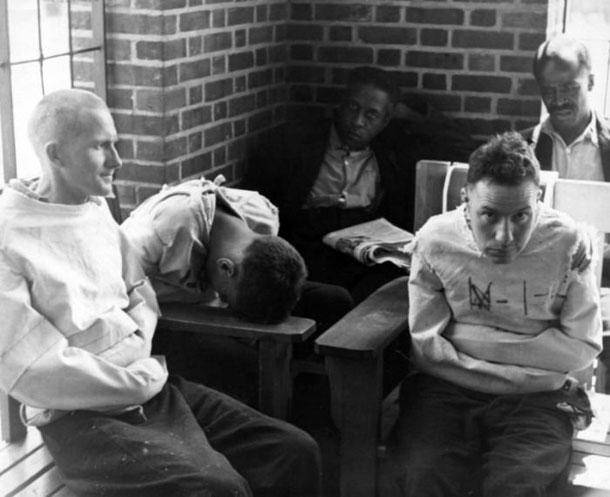

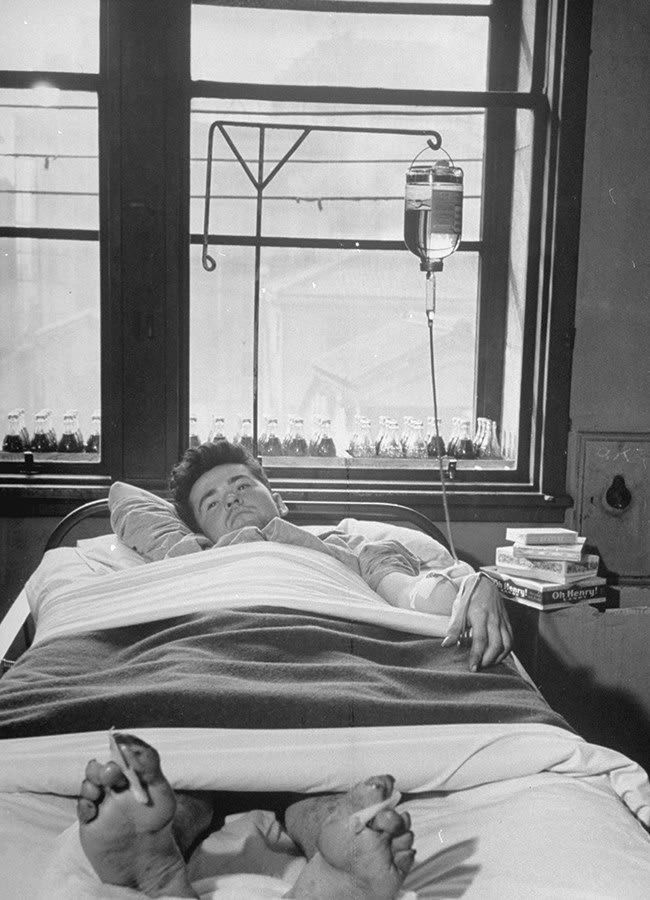

Conditions are the same everywhere - quite clean, good repair. Each department has about 50 people and about five wards. If there are not enough places, and this happens, the patients are put in the corridor, however, this is a normal practice for all hospitals.

Each department has about 50 people and about five wards. If there are not enough places, and this happens, the patients are put in the corridor, however, this is a normal practice for all hospitals.

Very difficult department - psychosomatic. It is, roughly speaking, for those who hear voices. Such patients can usually stop abruptly, talk to someone and move on as if nothing had happened. But in principle, you get used to their antics and invisible interlocutors.

They have moments of enlightenment. There was a patient who at times behaved like an absolutely healthy person, even volunteered to help. But then you walk along the corridor, you meet her, you look into her eyes and you see emptiness in them. At such moments, she stood in one position, staring at one point with a cloudy look. This look meant that something had to be done.

When such patients are admitted, they are first placed on a strict regimen in the examination room. This is necessary to understand what to expect. Anything can happen. There was a case when a child grabbed a bedside table and threw it into the nurse, personally one of the patients constantly threatened me with death, she had such an obsession.

Anything can happen. There was a case when a child grabbed a bedside table and threw it into the nurse, personally one of the patients constantly threatened me with death, she had such an obsession.

He made me watch him kill

Photo from personal archive

Irek did not hide his face. By the age of 18, he managed to visit a psychiatric hospital five times. To understand why and how he got there, just read his story.

– My father killed my mother when I was only one year old. My mother is from Ulu-Telyak, I don’t remember her, but I know that she drank hard, they tried to deprive her of parental rights. My father was imprisoned for seven years for the murder, then he died in the zone from tuberculosis, and I was sent to a baby house. So I wandered around orphanages for six years, and then I was adopted by my uncle and aunt from Turbasly.

When my uncle was drinking, he tried to kill my aunt. That night he drank with the neighbors, I noticed him, got very scared and ran home. My uncle came late, started looking for my aunt, as soon as he saw her, he immediately attacked with his fists and started beating her. Then he noticed me, dragged me into the room and made me watch. I stood with my face in my hands. I managed to escape, spent the night with neighbors, returned home in the morning and saw that my aunt was already dead. My uncle lay next to her body, he committed suicide. I was then seven years old, I had to return to the orphanage again. I did not want to live, because other children constantly rotted me. In my seven years of residence, I ended up in a psychiatric hospital twice after a suicide attempt.

That night he drank with the neighbors, I noticed him, got very scared and ran home. My uncle came late, started looking for my aunt, as soon as he saw her, he immediately attacked with his fists and started beating her. Then he noticed me, dragged me into the room and made me watch. I stood with my face in my hands. I managed to escape, spent the night with neighbors, returned home in the morning and saw that my aunt was already dead. My uncle lay next to her body, he committed suicide. I was then seven years old, I had to return to the orphanage again. I did not want to live, because other children constantly rotted me. In my seven years of residence, I ended up in a psychiatric hospital twice after a suicide attempt.

In the children's department, there are about six people in each room. There is a game room, the so-called cinema room with a TV on the wall. Watching TV was offered sitting on the floor. There were no classes as such, and not everyone could get into those that were, but only those who behaved well.

Children with different diagnoses were all together, if the child had a breakdown, he was tied to a bed and given sleeping pills. We had a chubby boy alone, he was 9-10 years old, he constantly broke something. They tied him up and gave him an injection, but the injection did not work. He was constantly screaming, had to give an injection every hour. I talked to him, talked, he understood that it was impossible to do this, but he continued to do it.

If I had the opportunity now, I would not go there, there is no help there, you just lie on the bed for 45 days and stare at the ceiling. There is no one to talk to, nothing to do, it is forbidden even to go outside. Because there was nothing to do, my condition only worsened.

The third time I was in the hospital was older. I had another suicide attempt. For the fourth time, I ended up in the forensic psychiatric department. I courted one girl, one day a man called me, introduced himself as her boyfriend and said that he would be waiting for me near the station. I came there with a knife just to scare. I scared him, and the next day I found out that they had filed an application against me. They tied me up and sent me back to the mental hospital. Honestly, when I saw a red fence with barbed wire, I got scared, and then I realized that this department is better than the children's department, you can smoke there, there is someone to talk to. Experienced criminals lived among us. I remember one convict - all in tattoos, three walkers behind him. I decided to talk to him, it worked out, and as a result we played checkers all day long.

I came there with a knife just to scare. I scared him, and the next day I found out that they had filed an application against me. They tied me up and sent me back to the mental hospital. Honestly, when I saw a red fence with barbed wire, I got scared, and then I realized that this department is better than the children's department, you can smoke there, there is someone to talk to. Experienced criminals lived among us. I remember one convict - all in tattoos, three walkers behind him. I decided to talk to him, it worked out, and as a result we played checkers all day long.

The last time I went to the hospital was literally last year, in the general psychiatric department. I felt good there, the only negative is the food, it is disgusting there, we never ate enough. I met some interesting guys there. One guy was lying because, just like me, he tried to kill himself. Now he is doing well, but the second one still died. He had schizophrenia. When we left the hospital, we continued to communicate, he periodically called and said that he was not feeling well, I advised him not to stop drinking pills. A little later, the calls stopped and I learned that he was dead.

A little later, the calls stopped and I learned that he was dead.

When I was in bed for the last time, my own sister found me, now I live with her and study to be a tractor driver. But I will be able to work by profession only when five years have passed since the last stay in a psychiatric hospital and when psychiatrists close the case. Now I dream of having children and a wife, having my own house, but at the same time I am attracted to prison romance. I don’t know why, I even made tattoos. I’m interested in how everything is arranged there, it’s interesting to know how to achieve authority and how people live there.

Read also

Subscribe to Proofy.rf in Google News, Yandex.News and our channel in Yandex.Zen, follow the main news of Russia and Bashkiria.

Ten days in a lunatic asylum

In the 19th century, investigative journalism became fashionable in England and America. Writers and reporters infiltrated the most diverse environments in order to subsequently come up with grandiose revelations. For example, Dickens took a trip to Yorkshire incognito and then branded the horrors of private schools in Nicholas Nickleby. And Australian journalist George Ernest Morrison was hired on the ship as a ship's doctor's assistant to expose the slave trade. Oddly enough, risky tasks of this kind were often taken on by women. Several striking examples of investigative journalism are presented in the new project of the CWS Translation Workshop by A. Borisenko and V. Sonkin. All through April, on Sundays, you'll be able to read sensational stories from the century before last: you'll learn how to play crazy, how to scrub floors and clean fireplaces, and where to rent someone else's baby or get a young virgin.

For example, Dickens took a trip to Yorkshire incognito and then branded the horrors of private schools in Nicholas Nickleby. And Australian journalist George Ernest Morrison was hired on the ship as a ship's doctor's assistant to expose the slave trade. Oddly enough, risky tasks of this kind were often taken on by women. Several striking examples of investigative journalism are presented in the new project of the CWS Translation Workshop by A. Borisenko and V. Sonkin. All through April, on Sundays, you'll be able to read sensational stories from the century before last: you'll learn how to play crazy, how to scrub floors and clean fireplaces, and where to rent someone else's baby or get a young virgin.

Nellie Bly

Elizabeth Jane Cochran was born in 1864 near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to an Irish family. She had four siblings and ten half-siblings (from her father's first marriage). As a child, Elizabeth was often called "Pink" for her love of pink in clothes. When she went to college with the goal of becoming a teacher, she changed her last name to Cochrane, which sounded more sophisticated. But Elizabeth studied for only a year: after the death of her father, the family did not have enough money. Once, after reading an article in the Pittsburgh Dispatch that assigned a woman the traditional role of mother and housewife, she wrote an indignant letter to the editor, signing herself "a lonely orphan." The letter impressed the editor so much that he tracked her down through a newspaper ad and offered to write a column. The girl took the pseudonym Nellie Bly - this name sounded in a popular song in those days.

When she went to college with the goal of becoming a teacher, she changed her last name to Cochrane, which sounded more sophisticated. But Elizabeth studied for only a year: after the death of her father, the family did not have enough money. Once, after reading an article in the Pittsburgh Dispatch that assigned a woman the traditional role of mother and housewife, she wrote an indignant letter to the editor, signing herself "a lonely orphan." The letter impressed the editor so much that he tracked her down through a newspaper ad and offered to write a column. The girl took the pseudonym Nellie Bly - this name sounded in a popular song in those days.

Nelly has published a series of articles about the hard life of working women. To do this, she got a job at one of the local factories. The newspaper received complaints from the manufacturers, and Bly was sent to cover the standard topics for a woman in journalism: fashion, social life and gardening. But she wanted something completely different - in her own words, she intended to "do what no girl had done before her. " And Nelly became a foreign correspondent in Mexico, where she spent six months. In her materials, she stigmatized corruption and the unbearable conditions in which the poor live, criticized the government - and was expelled from the country under threat of arrest.

" And Nelly became a foreign correspondent in Mexico, where she spent six months. In her materials, she stigmatized corruption and the unbearable conditions in which the poor live, criticized the government - and was expelled from the country under threat of arrest.

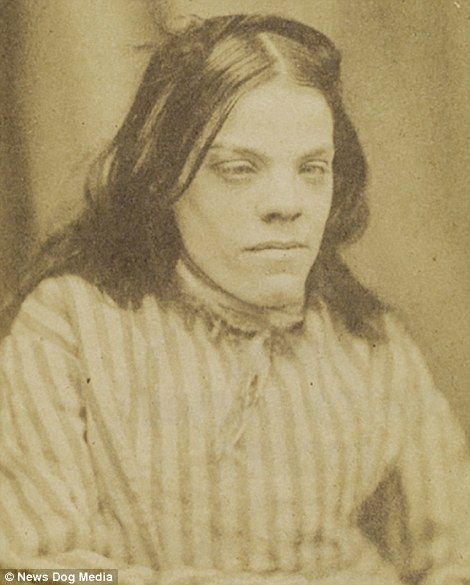

In 1887, Nellie Bly came to New York and took a job with the New York World newspaper, headed by Joseph Pulitzer. One of her first assignments was to investigate a lunatic asylum. Nelly feigned insanity in order to find out the truth about how the mentally ill are treated in an institution where outsiders cannot access. The journalist played her part so convincingly that four doctors declared her insane and sent her to a hospital on Blackwell Island.

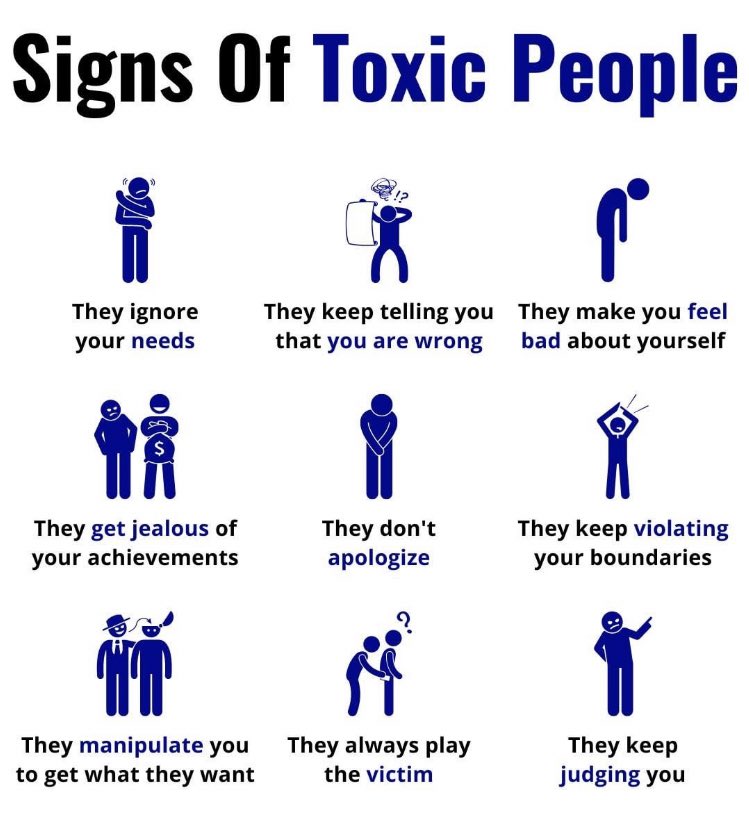

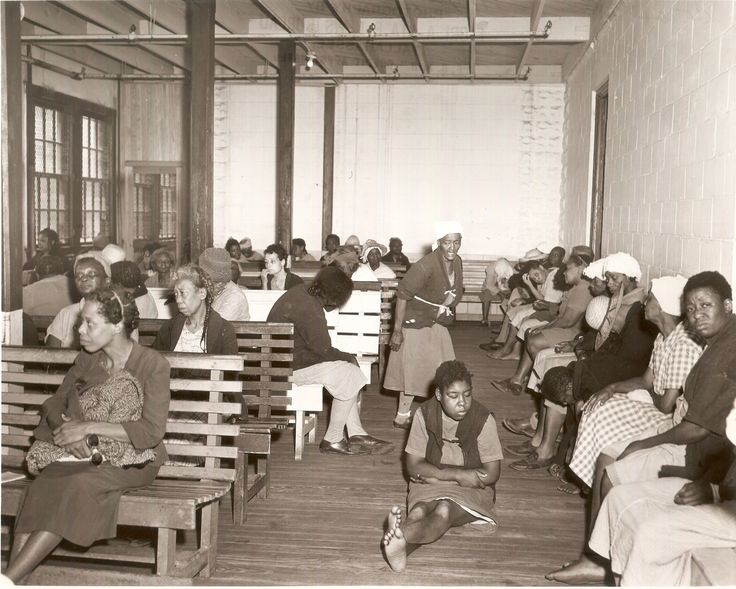

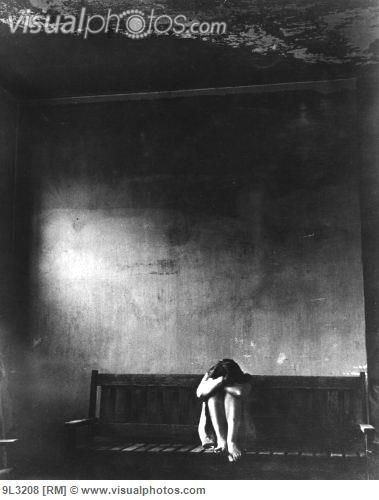

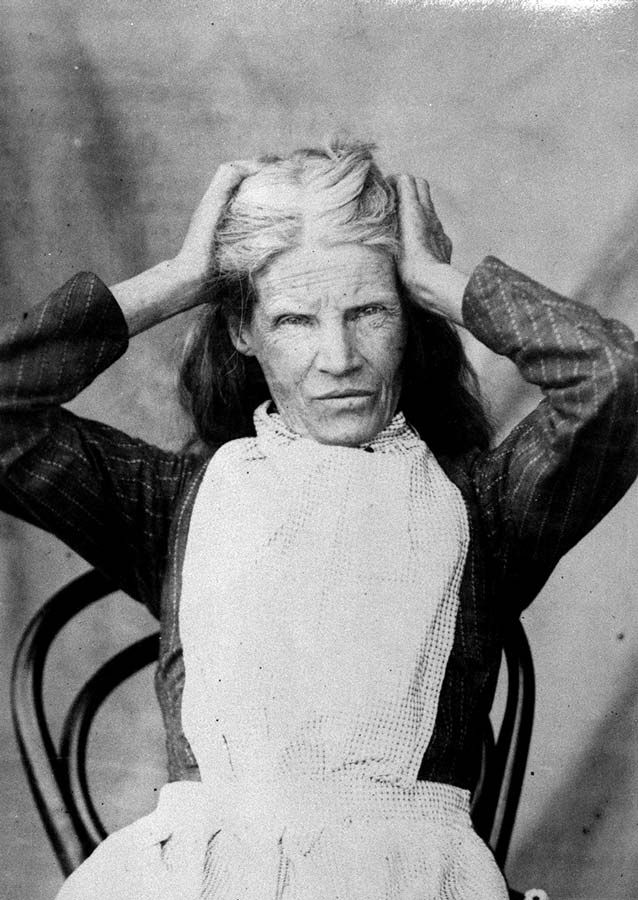

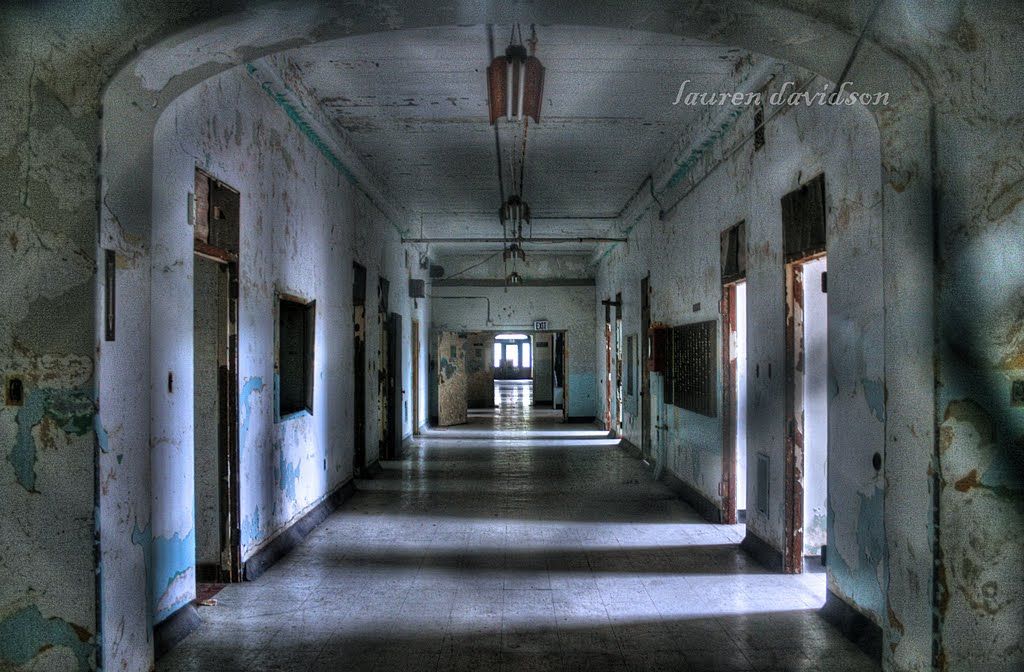

Bly found that the asylum is more like a prison, where prisoners are not eligible for pardon. In addition to the terrible living conditions, the patients suffered from bullying and physical cruelty of the staff and neglect from the doctors. The patients sat for days on hard benches in overcrowded rooms, they were forbidden to talk and read. At the same time, according to Nelly, some women were absolutely healthy mentally. Others, being foreigners, simply could not explain themselves, and no one provided them with an interpreter.

At the same time, according to Nelly, some women were absolutely healthy mentally. Others, being foreigners, simply could not explain themselves, and no one provided them with an interpreter.

All Nellie Bly's assurances that she was completely sane came to nothing - the editors had to send a lawyer to get her out of the hospital. After the publication of her revealing article, an investigation was launched with the involvement of an extended jury and with the participation of the journalist herself.

Together with the jury, Nelly returned to the hospital a month later and found that many of the violations she had identified were eliminated, incompetent staff were fired, and living conditions were improved. She did not manage to see those women whom she considered healthy - they were discharged or transferred. The hospital tried to cover up the abuse. As a result of the investigation, the authorities took measures to improve conditions in psychiatric hospitals, strengthened public control over them and seriously increased funding in this area.

Portrait of Nellie Bly at the age of 21. Mexico, 1885 Photo: public domain

Nellie Bly's report on the Blackwell Island Lunatic Asylum has become one of the most celebrated investigations in the history of American journalism. After the publication, she woke up famous. But the girl was not going to stop there. In 1889, she challenged literary fiction. After reading Jules Verne's novel Around the World in Eighty Days, she decided to travel around the world faster than the main character, Phileas Fogg. The journalist set off on her journey with one small bag of linen and toiletries, without a change of clothes and without any escort. On steamboats, trains, on horseback, on a donkey and in a rickshaw, she traveled through England, France (where she met Jules Verne himself), Italy, the Suez Canal, Ceylon, Singapore, Hong Kong and Japan. Along the way, she sent notes about her adventures by telegraph to the editor. The World took bets from readers on the exact time of the journalist's arrival in New York. In Hong Kong, Nellie learned that she had a competitor: a Cosmopolitan journalist had gone on a round-the-world trip the same day, but in the opposite direction, across the Pacific Ocean and Asia to Europe, and had visited Hong Kong three days earlier. But despite all the delays that arose on the road due to unreliable transport and weather conditions, Nellie Bly managed to circumnavigate the globe in 72 days, 6 hours and 11 minutes and set a world record. She was four and a half days ahead of her rival.

In Hong Kong, Nellie learned that she had a competitor: a Cosmopolitan journalist had gone on a round-the-world trip the same day, but in the opposite direction, across the Pacific Ocean and Asia to Europe, and had visited Hong Kong three days earlier. But despite all the delays that arose on the road due to unreliable transport and weather conditions, Nellie Bly managed to circumnavigate the globe in 72 days, 6 hours and 11 minutes and set a world record. She was four and a half days ahead of her rival.

Nelly has become a world celebrity. Her photographs graced the front pages of major newspapers, appeared in advertisements, on postcards and even on boxes of chocolates, and she knew the other side of fame. Now she could no longer investigate - she was instantly recognized. Then Miss Bly decided to leave the journalistic career and married a wealthy businessman, Robert Seaman, who was 42 years older than her. She took over his company, manufacturing steel containers, tanks and boilers, and even registered two patents in her name for an improved design of these products. After the death of her husband, Elizabeth Cochrane, Seaman was for some time one of the leading women industrialists in the United States. She carried out social reforms unheard of at that time at the enterprise: she banned piecework wages, established an equal minimum wage for men and women, opened a health center, a library and various clubs for employees. Unfortunately, Mrs. Seaman's lack of financial literacy and embezzlement by staff outweighed her good intentions, and the company soon went bankrupt.

After the death of her husband, Elizabeth Cochrane, Seaman was for some time one of the leading women industrialists in the United States. She carried out social reforms unheard of at that time at the enterprise: she banned piecework wages, established an equal minimum wage for men and women, opened a health center, a library and various clubs for employees. Unfortunately, Mrs. Seaman's lack of financial literacy and embezzlement by staff outweighed her good intentions, and the company soon went bankrupt.

Cover for the board game Around the World with Nellie Bly. 1890 Photo: public domain

Nellie Bly returned to journalism and became one of the first war correspondents of the First World War and the first woman reporter at the front. She was even arrested by the Hungarian police who mistook her for a British spy. Returning to the United States, the journalist wrote a regular column for the New York Evening Journal and did charity work helping orphans.

Nellie Bly died of pneumonia at 1922 years old in New York. She was 57 years old. Her name is still one of the most famous female names in journalism. Based on her famous investigation, two films were made: "10 Days in a Madhouse", directed by Timothy Hines, 2015, and "Escape from the Mad House", directed by Karen Moncrieff, 2019. The influence of this plot is also noticeable in the second season of American Horror Story. (“Psych hospital”, 2012-2013). The image of Nellie Bly inspired the creators of such characters as Lois Lane ("Superman"), Maggie Dubois ("The Great Race") and many other heroines of films and TV shows.

She was 57 years old. Her name is still one of the most famous female names in journalism. Based on her famous investigation, two films were made: "10 Days in a Madhouse", directed by Timothy Hines, 2015, and "Escape from the Mad House", directed by Karen Moncrieff, 2019. The influence of this plot is also noticeable in the second season of American Horror Story. (“Psych hospital”, 2012-2013). The image of Nellie Bly inspired the creators of such characters as Lois Lane ("Superman"), Maggie Dubois ("The Great Race") and many other heroines of films and TV shows.

CHAPTER I

A TRICKING REQUEST

On September 22, the management of The World newspaper asked me if I could try the methods of treatment in one of the New York asylums for the insane, so that then frankly and without embellishment write about the conditions of the patients, hospital management methods, and so on. Will I have the courage to go through the ordeal that such an assignment would require? Will I be able to portray the signs of insanity so convincingly that I can pass an examination and live a week among the mentally ill without the administration guessing that I am a spy? I said that I believe in myself. I relied on my acting skills and believed that I could act insane long enough to complete the task entrusted to me. Can I spend a week in the insane asylum on Blackwell Island? “I think I can handle it,” I said. And she did it.

I relied on my acting skills and believed that I could act insane long enough to complete the task entrusted to me. Can I spend a week in the insane asylum on Blackwell Island? “I think I can handle it,” I said. And she did it.

I was told to start work as soon as I felt ready. I had to conscientiously chronicle everything that happened and, once inside the walls of the hospital, find out and describe its internal structure, which nurses in white caps, as well as bolts and bars, so successfully hide from the public.

We are not sending you for sensationalism. Write down everything you see, good and bad; praise and criticize as you see fit, but always stick to the truth. My only concern is that you are always smiling,” the editor said.

“I won't do it again,” I said, and set off to carry out my delicate and, as it turned out, difficult task.

[...]

I shuddered at the thought that the mentally ill were completely at the mercy of the orderlies, that neither moaning nor pleas for release would help them get out if the guards did not want to release them. I enthusiastically undertook the assignment to find out the internal structure of the mental hospital on Blackwell's Island, but was not slow to ask the editor:

I enthusiastically undertook the assignment to find out the internal structure of the mental hospital on Blackwell's Island, but was not slow to ask the editor:

— How will you get me out when I get in there?

— I don't know, — he answered, — but you will be released if we tell you who you are and for what purpose you pretended to be crazy. The main thing is to get inside.

I didn't really expect to be able to fool the psychiatrists, and my editor probably believed even less.

All preliminary preparation for the mission was left to my discretion. Only one thing was decided for me: I would act under the pseudonym Nellie Brown, which coincided with the initials on my underwear. By this name, the newspaper can easily track my movements and, if necessary, rescue me from any difficulties and dangers.

[...]

I decided to act as an unfortunate, destitute lunatic and considered it my duty not to evade any trouble that this might entail. Having become a patient for a while in one of the city's psychiatric hospitals, I learned from my own experience how these defenseless people are treated, and I saw and heard even more. When I had seen enough, the newspaper secured my release. I left the hospital with joy and regret - glad that I could again enjoy the air of freedom, and with regret because I could not take with me some of the unfortunate women who lived and suffered with me and were, in my opinion, just as reasonable, as I was and still am to this day.

When I had seen enough, the newspaper secured my release. I left the hospital with joy and regret - glad that I could again enjoy the air of freedom, and with regret because I could not take with me some of the unfortunate women who lived and suffered with me and were, in my opinion, just as reasonable, as I was and still am to this day.

Nellie is rehearsing crazy at home

But I'll tell you this: as soon as I got into the psychiatric hospital on Blackwell's Island, I gave up all attempts to play the role of a lunatic. I spoke and acted exactly the same as in ordinary life. However, strangely enough, the more reasonable my behavior was, the more crazy everyone thought me, except for a single doctor, whose kindness and participation I will never forget.

CHAPTER XI

IN THE BATH

[…] We were taken to a cold, damp bathroom and ordered to undress. Did I resist? Yes, I've never been so hot in my life. I was told that if I did not obey, they would use force and not stand on ceremony. At that moment, I noticed that one of the craziest women in the whole hospital was standing near the filled bathtub with a large faded rag in her hands. She was enthusiastically talking to herself and, it seemed to me, giggling bloodthirstyly. Now I understand what will happen to me. I was thrown into a tremor. The nurses removed all my clothes layer by layer until I was left in my underwear.

At that moment, I noticed that one of the craziest women in the whole hospital was standing near the filled bathtub with a large faded rag in her hands. She was enthusiastically talking to herself and, it seemed to me, giggling bloodthirstyly. Now I understand what will happen to me. I was thrown into a tremor. The nurses removed all my clothes layer by layer until I was left in my underwear.

“I won't take it off,” I protested, but my underwear was also torn off. I glanced at the patients crowding in the doorway watching this scene, and, not caring about grace, quickly jumped into the bath.

The water turned out to be ice cold and I rebelled again. Useless! Finally, I begged them to at least take the patients away, but I was ordered to shut up. The madwoman began to scrape my skin. I can't describe it otherwise than with the word "scrape". She took some softened soap from a small tin and rubbed it all over my body—even my face and my beautiful hair. In vain I begged her not to touch at least her hair! Finally, I became completely blind and dumb, but the old woman kept scratching and scraping, never ceasing to mutter under her breath. My teeth chattered, and my arms and legs were covered with goosebumps and blue from the cold. Suddenly, three buckets of the same ice-cold water were splashed on my head one after another, which got into my eyes, ears, nose and mouth. Perhaps now I understand how drowning people feel. When they pulled me out of the bathroom, I was shaking like a leaf and gasping for air. At that moment, I really looked insane. I saw an indescribable expression on the faces of my friends in misfortune, who watched my fate and knew that the same thing would soon await them. Imagining what a ridiculous sight I now represent, I involuntarily burst out laughing. A short flannel shirt was pulled over my wet body, on the hem of which was written in large black letters: “Psychiatric hospital, Fr. B., o. 6", which meant Blackwell's Island, the sixth division.

My teeth chattered, and my arms and legs were covered with goosebumps and blue from the cold. Suddenly, three buckets of the same ice-cold water were splashed on my head one after another, which got into my eyes, ears, nose and mouth. Perhaps now I understand how drowning people feel. When they pulled me out of the bathroom, I was shaking like a leaf and gasping for air. At that moment, I really looked insane. I saw an indescribable expression on the faces of my friends in misfortune, who watched my fate and knew that the same thing would soon await them. Imagining what a ridiculous sight I now represent, I involuntarily burst out laughing. A short flannel shirt was pulled over my wet body, on the hem of which was written in large black letters: “Psychiatric hospital, Fr. B., o. 6", which meant Blackwell's Island, the sixth division.

By that time Miss Mayard had also been undressed, and no matter how terrible my recent bath was, I would willingly endure it again, if only to save her from this fate. Imagine what it was like for a sick girl to plunge into a cold bath, after which even I, with my good health, was shaking like a fever! I heard her explain to Miss Group that she still had a headache from her illness. Most of her short hair fell out and she asked that the lunatic be told to rub it softer, to which Miss Group replied:

Imagine what it was like for a sick girl to plunge into a cold bath, after which even I, with my good health, was shaking like a fever! I heard her explain to Miss Group that she still had a headache from her illness. Most of her short hair fell out and she asked that the lunatic be told to rub it softer, to which Miss Group replied:

- Nobody cares if you get hurt or not. Shut up or it'll get worse.

Miss Mayard obeyed, and I didn't see her again that day.

I was hurriedly taken to a room with six beds and put into one of them, but then another nurse came in and pulled me out of bed with the words:

— Nellie Brown should be put in a solitary ward for the night. I think it's noisy.

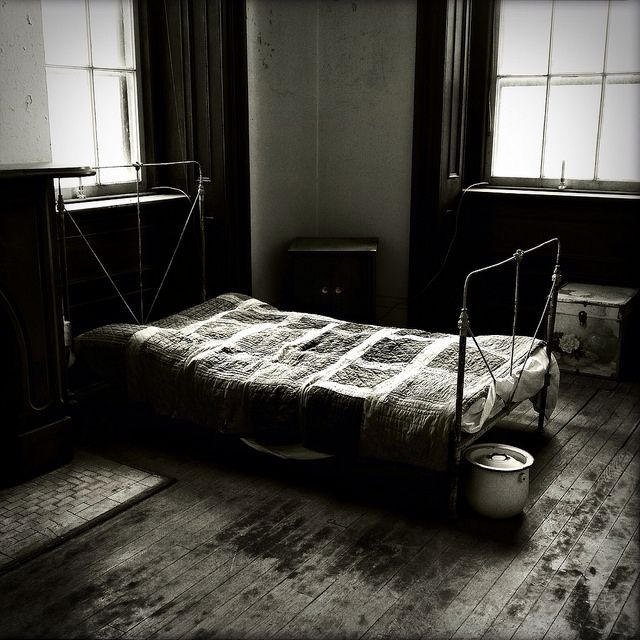

Nelly's bedroom

I was taken to room twenty-eight and left alone. I tried to get comfortable in bed, but it was impossible. The mattress was humped in the middle and sloping along the edges. As soon as I lay down, the pillow got wet, and the damp shirt soaked the sheet with dampness. When Miss Group came in, I asked if they would give me a nightgown.

When Miss Group came in, I asked if they would give me a nightgown.

“That doesn't happen with us,” she said.

"I don't want to sleep without my nightgown," I replied.

"I don't care about that," she said. “You are now in a public institution, and there is no reason to expect that we will fulfill your whims. You are here out of grace: say thank you for what is.

“But the city pays to keep such places in proper order,” I insisted, “and pays employees to be kind to those unfortunate people who got here.

- Don't wait for kindness - you won't wait, - she said, and then went out and closed the door.

Underneath me was a sheet and oilcloth, and above me was another sheet and a black wool blanket. Nothing has ever irritated me more than this woolen blanket as I tried to cover my shoulders with it so that the cold wouldn't crawl under it. As soon as I pulled it up, my legs turned out to be bare, and when I covered them, my shoulders began to freeze. There was absolutely nothing in the room - only the bed and myself. When the door was locked, I imagined that they would leave me alone all night, but from the corridor came the heavy steps of two women. They stopped at each door, unlocked it, and after a few seconds I heard them lock it again. So, completely unconcerned about the silence, they walked along the entire corridor up to my room. Here they stopped again. The key turned in the lock and they entered. They wore white and brown striped dresses with copper buttons, wide white aprons and small white caps. They were girded with thick green cords from which dangled bunches of massive keys, and dressed just like the orderlies I had seen during the day. The one that went first carried a lantern. She shone a light in my face, saying to her companion:

There was absolutely nothing in the room - only the bed and myself. When the door was locked, I imagined that they would leave me alone all night, but from the corridor came the heavy steps of two women. They stopped at each door, unlocked it, and after a few seconds I heard them lock it again. So, completely unconcerned about the silence, they walked along the entire corridor up to my room. Here they stopped again. The key turned in the lock and they entered. They wore white and brown striped dresses with copper buttons, wide white aprons and small white caps. They were girded with thick green cords from which dangled bunches of massive keys, and dressed just like the orderlies I had seen during the day. The one that went first carried a lantern. She shone a light in my face, saying to her companion:

- This is Nellie Brown.

Looking at her, I asked:

— Who are you?

"Night nurse, dear," she replied, and after wishing me good sleep, she went out and locked the door behind her. They came into my room several times during the night, and even if I could sleep, the sound of the heavy door opening, their loud conversations and heavy steps would wake me up.

They came into my room several times during the night, and even if I could sleep, the sound of the heavy door opening, their loud conversations and heavy steps would wake me up.

I couldn't sleep, and I lay there, imagining what a nightmare would reign in the hospital in case of a fire. Each door is locked separately, the windows are securely barred - it will be impossible to escape. In one building, Dr. Ingram seems to have told me, there are about three hundred women. They are locked - from one to ten in the ward. You can only get out if the doors are unlocked. A fire is not only possible, but more than likely. If the building caught fire, the guards or nurses would not think of releasing their insane wards. You will see this later, when the time comes to tell about their cruel attitude towards the unfortunate people entrusted to their care. I assure you, in the event of a fire, not even a dozen women will be saved. Everyone will be left to burn alive. Even if the nurses were kind, which they are not, one should not expect such self-control from women of their kind to risk their lives to open a hundred doors for insane prisoners. If everything remains as it is, then this place will one day become the scene of an unprecedented tragedy.

If everything remains as it is, then this place will one day become the scene of an unprecedented tragedy.

[…]

CHAPTER XII

WALKING WITH THE CRAZY

Quiet patients on a walk

I will never forget my first walk. When all the patients put on white straw hats like bathers in Coney Island, I couldn't help laughing - they looked so comical. […] We lined up in pairs and, accompanied by nurses, went for a walk through the back door. Before we had even taken a few steps, I saw that women were walking in endless lines along all the paths, under the supervision of nurses. How many there were! They wandered slowly everywhere they looked, in terrible dresses, ridiculous straw hats and kerchiefs. I kept looking at the people passing by and felt that I was terrified. Empty eyes, devoid of facial expression and muttering indistinctly. One group passed by, and my sense of smell, like vision, told me that they were terribly dirty.

— Who is this? I asked the patient next to me.

“They are considered the most violent on the island,” she replied. - They are kept at the Resort - in the first building, which has steep steps.

Some howled, others shouted swear words, others sang, prayed or preached, each in their own madness, and were the most miserable bunch of people that I have ever seen. As their hubbub faded in the distance, a new sight appeared that I will never forget.

A long thick rope connected the wide leather belts fastened around the waists of fifty-two women. Attached to the end of the rope was a heavy iron cart in which two patients sat. One was nursing her bad leg, and the other was yelling at some nurse:

— You beat me, and I won't forget it. You wanna kill me! she exclaimed, and burst into sobs.

Each of the "chain women", as other patients called them, had her own whim. Some screamed incessantly. One - with blue eyes - caught my eye and, as far as she could, turned to me, smiling, saying something; on her face lay a terrible stamp of complete madness. Doctors could not doubt her diagnosis. This sight would have evoked inexpressible horror in anyone who had never before encountered a mentally ill person.

Doctors could not doubt her diagnosis. This sight would have evoked inexpressible horror in anyone who had never before encountered a mentally ill person.

- God help them! breathed Miss Neville. “It's so terrible that I can't look at them.

They passed, and others immediately took their place. Can you imagine it? According to one of the doctors, there are sixteen hundred insane women on Blackwell Island.

Madness! What could be worse? My heart sank with pity when I looked at the old, gray-haired women, aimlessly saying something into the void. One was in a straitjacket, and the other two had to drag her. The crippled, the blind, the old, the young, the homely and the pretty: a mindless human mass. What could be worse than such a fate?

I looked at the pretty lawns that I once thought must be a comfort to the unfortunate creatures imprisoned on the island and laughed at my thoughts. What is their joy? It is forbidden to step on the grass - you can only look. I saw how some of the patients with trepidation and tenderness pick up a nut or a yellow leaf that has fallen on the path. But they are not allowed to keep them. Nurses always make them throw away that little bit of comfort that the Lord has given them.

I saw how some of the patients with trepidation and tenderness pick up a nut or a yellow leaf that has fallen on the path. But they are not allowed to keep them. Nurses always make them throw away that little bit of comfort that the Lord has given them.

When I passed by a low building where many helpless lunatics were imprisoned, I read the motto on the wall: "As long as I live, I hope." His absurdity struck me. Above the gate leading to the orphanage, I would write: "Abandon hope, ye who enter here."

[…]

The next morning, as we began our endless daytime "spectacle," two nurses, with the help of several patients, brought in a woman who had prayed to the Lord the previous night to take her home. This didn't surprise me. The patient appeared to be at least seventy years old and blind. Although it was very cold in the ward, the old lady was dressed as lightly as the rest. When she was brought into the common room and seated on a hard bench, she exclaimed:

— What are you doing to me? I'm cold, very cold! Why can't you leave me in bed, or at least give me a shawl!

Then she got up and groped her way out of the room. Several times the nurses pushed her back onto the bench and laughed heartlessly as she got up again and again and tried to leave, bumping first on the table, then on the corner of one of the benches. The old woman took off her heavy shoes, received as a gift from benefactors, and complained that they rubbed her feet. But the nurses ordered the two patients to shod her again. She took off her shoes several times and resisted those who put them on. At one point, seven people tried to put it on at once. Then the old woman wanted to lie down on the bench, but they lifted her up. It was unbearable to hear her lamentations: "Give me a pillow, cover me with a blanket, I'm very cold."

Several times the nurses pushed her back onto the bench and laughed heartlessly as she got up again and again and tried to leave, bumping first on the table, then on the corner of one of the benches. The old woman took off her heavy shoes, received as a gift from benefactors, and complained that they rubbed her feet. But the nurses ordered the two patients to shod her again. She took off her shoes several times and resisted those who put them on. At one point, seven people tried to put it on at once. Then the old woman wanted to lie down on the bench, but they lifted her up. It was unbearable to hear her lamentations: "Give me a pillow, cover me with a blanket, I'm very cold."

And then I saw Miss Group fall on her, press her cold hands to her face, and then put them down her collar; in response to the old woman's complaints, she laughed cruelly, like the other nurses, and continued to bully her. On the same day, the old woman was transferred to another department.

CHAPTER XIV

SOME SAD STORIES

[…]

Once upon a time, Mrs. Cotter, a sweet fragile patient on a walk, thought she saw her husband. She broke free and ran towards him. For this she was sent to a sanatorium. Later she said:

Cotter, a sweet fragile patient on a walk, thought she saw her husband. She broke free and ran towards him. For this she was sent to a sanatorium. Later she said:

- Just remembering this is enough to drive me crazy. For tears, the nurses beat me with a broomstick, and then they jumped on me, and now everything inside me hurts. Then they tied me hand and foot, threw a sheet over my head, pulled it so tight around my neck that I could not scream, and threw me into an ice bath. They kept me underwater until all hope left me and I passed out. They grabbed my ears and banged my head against the floor and wall, and then pulled out my hair from the roots so that it would never grow back.

Mrs. Cotter showed me evidence of her words: a dent on the back of her head and bald patches where her hair was pulled out in tufts. I convey her story without embellishment.

— I have seen that other patients were treated even worse, but life in the Sanatorium undermined my health. And even if I get out of here, I will remain disabled. When my husband found out about the methods of treatment that I was undergoing, he threatened to discredit this institution if they did not transfer me from the Sanatorium, and here I am. Now my sanity is back. The old fears were gone, and the doctor promised that he would allow my husband to take me home.

When my husband found out about the methods of treatment that I was undergoing, he threatened to discredit this institution if they did not transfer me from the Sanatorium, and here I am. Now my sanity is back. The old fears were gone, and the doctor promised that he would allow my husband to take me home.

When I met Bridget McGuinness, she seemed quite normal. She said that she was sent to the fourth Sanatorium, where she became one of the "chain women".

- The beatings I endured were terrible. I was dragged by my hair, held under water until I began to choke, choked and kicked. The nurses always left the calm patients at the window to let them know if any of the doctors were nearby. Complaining to the doctors was useless, because they usually attributed everything to our damaged mind. In addition, we received a new batch of beatings for complaints. The nurses held us under water and threatened to drown us if they did not promise not to tell us anything more. We promised, because we knew that the doctors would not help us, and were ready to do everything to avoid punishment. After I broke the window, I was transferred to the Resort - the creepiest place on the island. The stench and filth are terrible. In summer, the air is full of flies. Local food is much worse than in other departments, and it is only served in tin plates. The gratings are not outside, as they are here, but inside. Many quiet patients are kept at the Resort for years by nurses to do the dirty work. I was beaten all the time, and once the nurses attacked me and broke two of my ribs.

After I broke the window, I was transferred to the Resort - the creepiest place on the island. The stench and filth are terrible. In summer, the air is full of flies. Local food is much worse than in other departments, and it is only served in tin plates. The gratings are not outside, as they are here, but inside. Many quiet patients are kept at the Resort for years by nurses to do the dirty work. I was beaten all the time, and once the nurses attacked me and broke two of my ribs.

Psychiatric hospital

— While I was living there, a pretty young girl was transferred to us. She was ill recently and protested when she was assigned to this filthy place. One night, the nurses took her away, beat her and kept her naked in an ice bath before throwing her on the bed. By morning, the girl was dead. Doctors said that she died of convulsions, and no one began to understand this.

- They give so many injections of morphine and chloral that one could go crazy with it. I saw how women were tormented by unbearable thirst due to the action of medicines, but the nurses did not let them drink. I have heard patients begging for at least a drop all night, but they were denied. I myself begged for water until my throat was so dry that I could not speak.

I have heard patients begging for at least a drop all night, but they were denied. I myself begged for water until my throat was so dry that I could not speak.

[…]

CHAPTER XVI

FAREWELL

Blackwell Island Mental Hospital is a human rat trap. It is easy to get into it, but once there, you will not be able to get out. I intended to pretend to be wild and sneak into the rowdy buildings, the Resort and the Sanatorium, but after hearing the stories of two completely normal women, I decided not to risk my health and hair.

I was kept from visiting until the last minute, and when attorney Peter A. Hendrix came and said that my friends were ready to vouch for me if I decided to leave the hospital, I immediately agreed. I asked him to send food as soon as he returned to the city, and I began to look forward to my release.

It happened faster than I had hoped. I was called out of the line while walking, just at the moment when my attention was attracted by a poor woman who had fainted - the nurses were trying to force her to go on.