Denial stage of grieving

Five Stages Of Grief - Understanding the Kubler-Ross Model

Depression

An Examination of the Kubler-Ross Model

The Editors of Psycom

iStockPhoto.com/PeopleImages

Grief Model Background

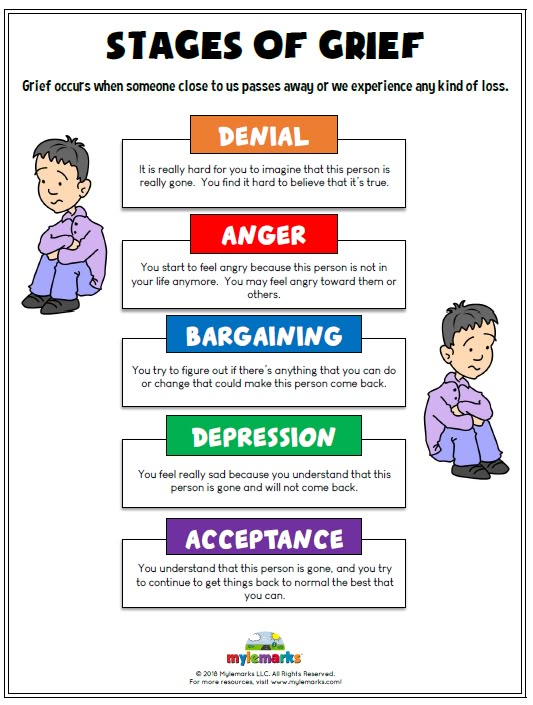

Throughout life, we experience many instances of grief. Children may grieve a divorce, a wife may grieve the death of her husband, a teenager might grieve the ending of a relationship, or you might have grieved the loss of a pet.

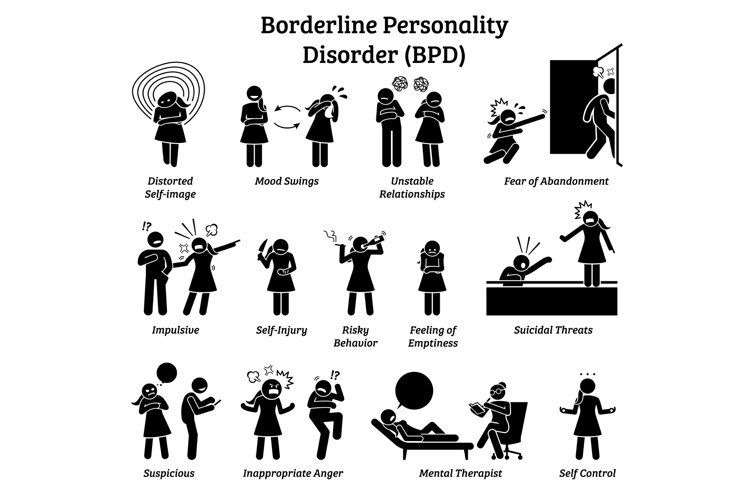

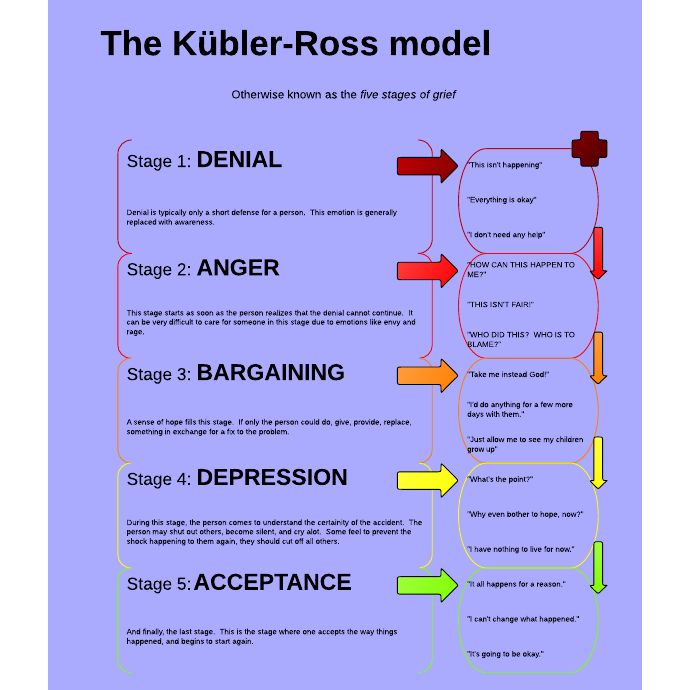

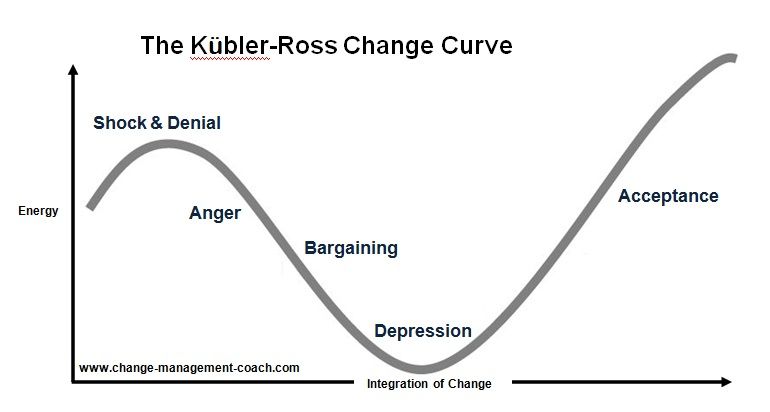

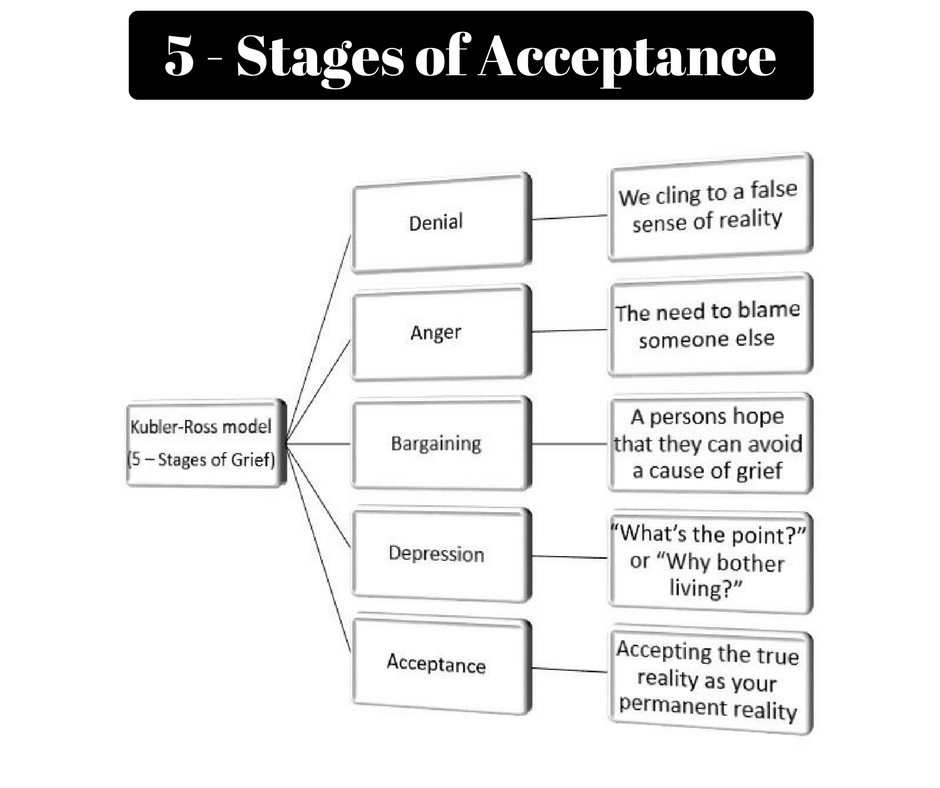

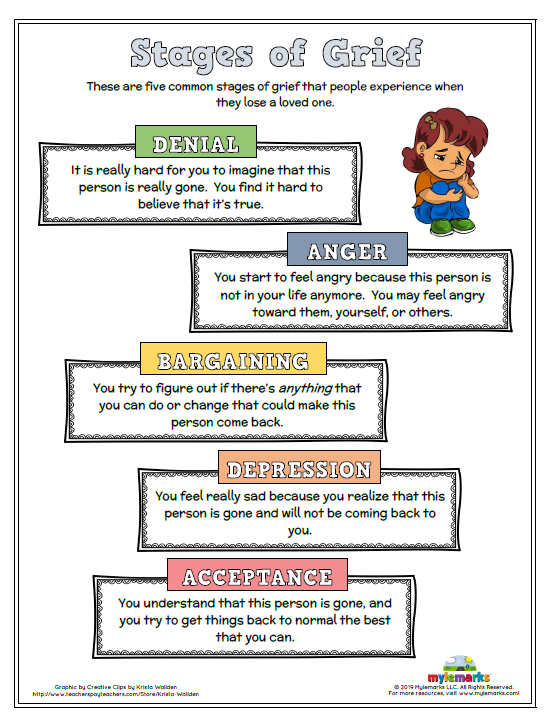

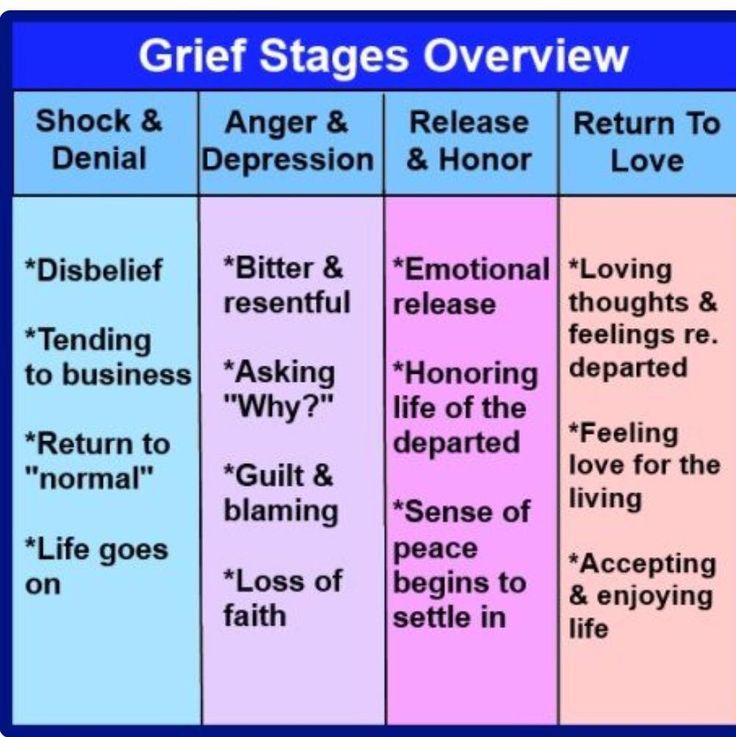

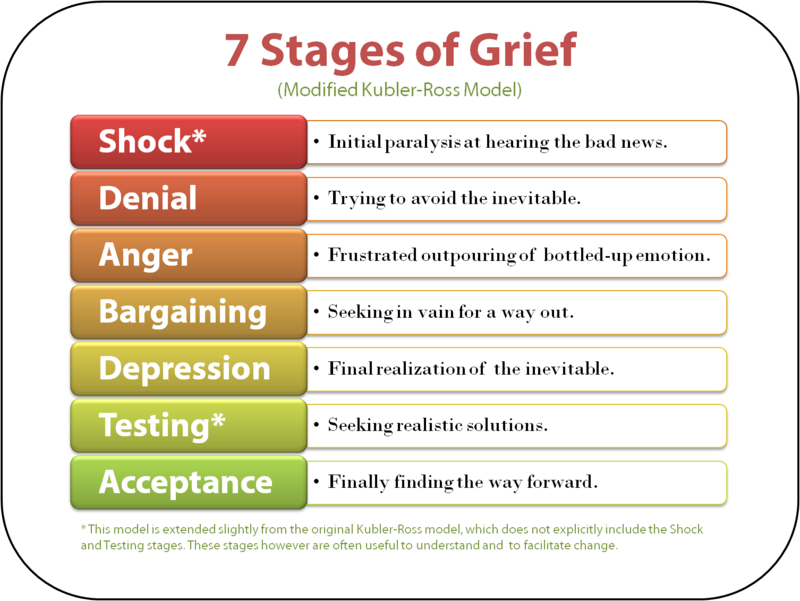

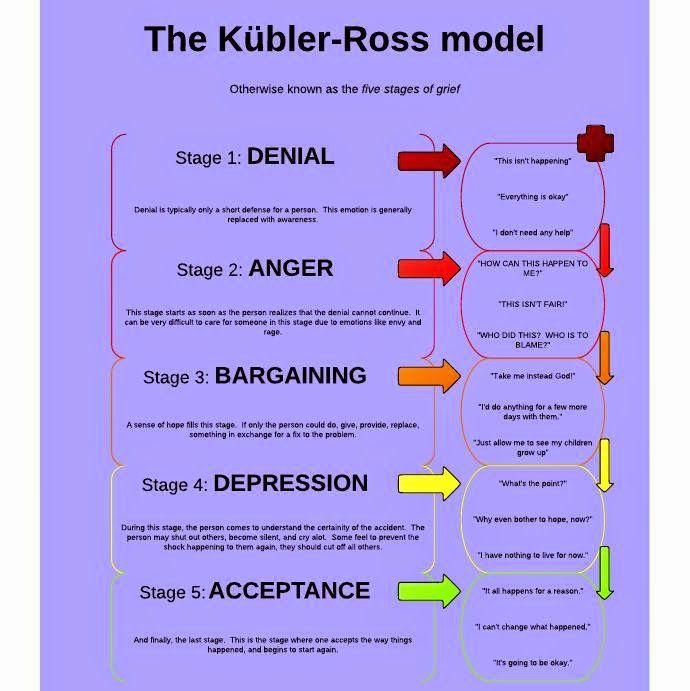

In 1969, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross described five common stages of grief, popularly referred to as DABDA. They include:

Denial

Anger

Bargaining

Depression

Acceptance

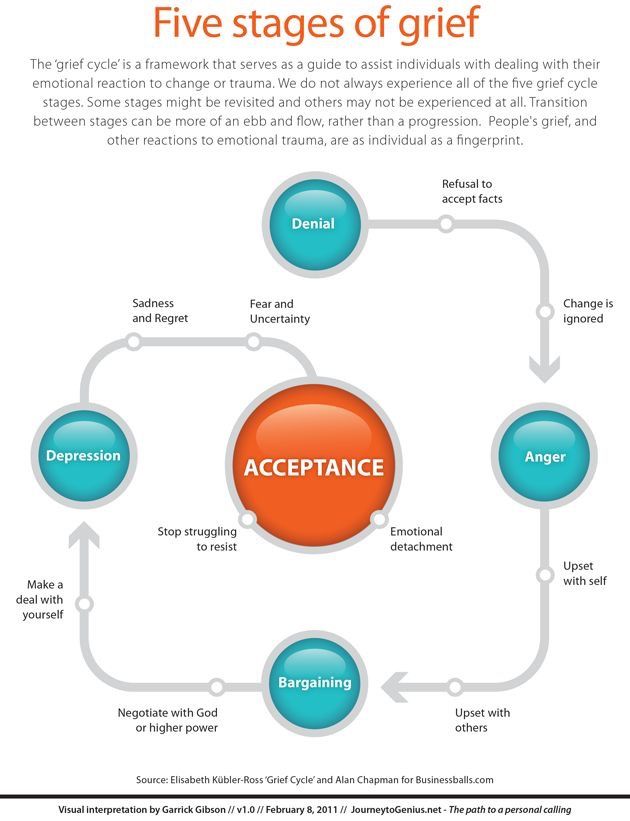

A Swiss psychiatrist, Kübler-Ross first introduced her five stage grief model in her book On Death and Dying. Kübler-Ross’ model was based on her work with terminally ill patients and has been the subject of debate and criticism in the years since. Mainly, because people studying her model mistakenly believed this is the specific order in which people grieve and that all people go through all stages.

Kübler-Ross now notes that these stages are not linear and some people may not experience any of them. Others might only undergo a few stages rather than all five. It is now more readily known that these five stages of grief are the most commonly observed in the grieving population.

So, What Are The Five Stages?

Denial

Denial is the stage that can initially help you survive the loss. You might think life makes no sense, has no meaning, and is too overwhelming. You start to deny the news and, in effect, go numb.

It's common in this stage to wonder how life will go on in this different state—you are in a state of shock because life as you once knew it has changed in an instant. If you were diagnosed with a deadly disease, you might believe the news is incorrect—a mistake must have occurred somewhere in the lab; they mixed up your blood work with someone else's. If you receive news of the death of a loved one, perhaps you cling to a false hope that they identified the wrong person. In the denial stage, you are not living in "actual reality," rather, you are living in a "preferable" reality.

If you receive news of the death of a loved one, perhaps you cling to a false hope that they identified the wrong person. In the denial stage, you are not living in "actual reality," rather, you are living in a "preferable" reality.

Interestingly, it is denial and shock that help you cope and survive the grief event. Denial aids in pacing your feelings of grief. Instead of becoming completely overwhelmed with grief, we deny it, do not accept it, and stagger its full impact on us. Think of it as your body's natural defense mechanism, saying "Hey, there's only so much I can handle at once."

Once the denial and shock start to fade, the healing process begins. At this point, those feelings that you were once suppressing are coming to the surface.

Once you start to live in "actual" reality again, anger might start to set in. This is a common stage to think "Why me?" and "Life's not fair!" You might look to blame others for the cause of your grief and also may redirect your anger to close friends and family. You find it incomprehensible how something like this could happen to you. If you are strong in faith, you might start to question your belief in God: Where is God? Why didn't he protect me?

You find it incomprehensible how something like this could happen to you. If you are strong in faith, you might start to question your belief in God: Where is God? Why didn't he protect me?

Researchers and mental health professionals agree that this anger is a necessary stage of grief. And encourage the anger. It's important to truly feel the anger. Even though it might seem like you are in an endless cycle of anger, it will dissipate—and the more you truly feel the anger, the more quickly it will dissipate, and the more quickly you will heal. It is not healthy to suppress your feelings of anger—it is a natural response—and perhaps, arguably, a necessary one.

(However, while suppressing anger is not advised, neither is letting it control you. It's important to seek help from a trained counselor or therapist if you are struggling with processing your anger.)

In everyday life, we are normally told to control our anger toward situations and toward others. When you experience a grief event, you might feel disconnected from reality, that you have no grounding anymore. Your life has shattered and there's nothing solid to hold onto. Think of anger as a strength to bind you to reality. You might feel deserted or abandoned during a grief event. That no one is there. You are alone in this world. The direction of anger toward something or somebody is what might bridge you back to reality and connect you to people again. It is a "thing." It's something to grasp onto, a natural step in healing.

Your life has shattered and there's nothing solid to hold onto. Think of anger as a strength to bind you to reality. You might feel deserted or abandoned during a grief event. That no one is there. You are alone in this world. The direction of anger toward something or somebody is what might bridge you back to reality and connect you to people again. It is a "thing." It's something to grasp onto, a natural step in healing.

Bargaining

When something bad happens, have you ever found yourself making a deal with God? "Please God, if you heal my husband, I will strive to be the best wife I can ever be, and never complain again." This is bargaining.

In a way, this stage is false hope. You might falsely make yourself believe that you can avoid the grief through this type of negotiation. If you change this, I'll change that. You are so desperate to get your life back to how it was before the grief event, you are willing to make a major life change in an attempt toward normality.

Guilt is a common wingman of bargaining. This is when you can experience a seemingly endless string of "what ifs": What if I had left the house 5 minutes sooner? The accident would have never happened. What if I encouraged him to go to the doctor six months ago like I first thought? The cancer could have been found sooner and he could have been saved.

Depression

Depression is commonly associated with grief. It can be a reaction to the emptiness we feel when we are living in reality and realize the person or situation is gone or over. In this stage, you might withdraw from life, feel numb, live in a fog, and not want to get out of bed. The world might seem too much and too overwhelming for you to face. You might not want to be around others or feel like talking, and you might feel hopeless. You might even experience suicidal thoughts, thinking "What's the point of going on?"

Acceptance

The last stage of grief identified by Kübler-Ross is acceptance. Not in the sense that "it's OK my husband died" but rather, "my husband died, but I'm going to be OK."

Not in the sense that "it's OK my husband died" but rather, "my husband died, but I'm going to be OK."

In this stage, your emotions may begin to stabilize. You re-enter reality. You come to terms with the fact that the "new" reality is your partner is never coming back, or that you are going to succumb to your illness. It's not a "good" thing, but it's something you can move forward from.

It is definitely a time of adjustment and readjustment. There are good days, there are bad days, and then there are good days again. In this stage, it does not mean you'll never have another bad day, where you are uncontrollably sad. But, the good days tend to outnumber the bad days.

In this stage, you may lift from your fog, start to engage with friends again, and might even make new relationships as time goes on. You understand your loved one can never be replaced, but you move, grow, and evolve into your new reality.

Symptoms of Grief

Your grief symptoms may present themselves physically, socially, mentally, emotionally, or spiritually. Some of the most common symptoms of grief are presented below:

Some of the most common symptoms of grief are presented below:

Crying

Headaches

Difficulty sleeping

Questioning the purpose of life

Questioning your spiritual beliefs (e.g., your belief in God)

Feelings of detachment

Isolation from friends and family

Abnormal behavior

Worry

Anxiety

Frustration

Guilt

Fatigue

Anger

Loss of appetite

Aches and pains

Stress

Treatment of Grief

Counseling, along with medication when needed, have been the most common methods of treating grief. Initially, your doctor may prescribe you medications to help you function more fully. These might include sedatives, antidepressants, or anti-anxiety medications to help you get through the day. In addition, your doctor might prescribe medication to help you sleep.

However, the use of medication in grief treatment is controversial. Some providers believe it can mask feelings that arise as one goes through the grief process, and potentially delay healing. But you and your physican can determine a treatment plan that's best for you.

Counseling is a more solid approach to grief. Support groups, bereavement groups, or individual counseling can help you work through unresolved grief. This is a beneficial treatment alternative when you find the grief event is creating obstacles in your everyday life and you are having trouble functioning.

This support in no way "cures" you of your loss, rather, it provides you with coping strategies to help you deal with your grief in an effective way. The Kübler-Ross Model is a tried and true guideline, but there is no right or wrong way to work through your grief. Personal experiences may vary as people move among the stages of grief.

If you or a loved one is having a hard time coping with a grief event, seek treatment from a health professional or mental health provider. Call a doctor right away if you experience thoughts of suicide, feelings of detachment for more than two weeks, you experience a sudden change in behavior, or believe you are suffering from depression.

Call a doctor right away if you experience thoughts of suicide, feelings of detachment for more than two weeks, you experience a sudden change in behavior, or believe you are suffering from depression.

Notes: This article was originally published March 22, 2016 and most recently updated June 7, 2022.

SAMHSA’s National Helpline | SAMHSA

Your browser is not supported

Switch to Chrome, Edge, Firefox or Safari

Main page content

-

SAMHSA’s National Helpline is a free, confidential, 24/7, 365-day-a-year treatment referral and information service (in English and Spanish) for individuals and families facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

Also visit the online treatment locator.

SAMHSA’s National Helpline, 1-800-662-HELP (4357) (also known as the Treatment Referral Routing Service), or TTY: 1-800-487-4889 is a confidential, free, 24-hour-a-day, 365-day-a-year, information service, in English and Spanish, for individuals and family members facing mental and/or substance use disorders. This service provides referrals to local treatment facilities, support groups, and community-based organizations.

This service provides referrals to local treatment facilities, support groups, and community-based organizations.

Also visit the online treatment locator, or send your zip code via text message: 435748 (HELP4U) to find help near you. Read more about the HELP4U text messaging service.

The service is open 24/7, 365 days a year.

English and Spanish are available if you select the option to speak with a national representative. Currently, the 435748 (HELP4U) text messaging service is only available in English.

In 2020, the Helpline received 833,598 calls. This is a 27 percent increase from 2019, when the Helpline received a total of 656,953 calls for the year.

The referral service is free of charge. If you have no insurance or are underinsured, we will refer you to your state office, which is responsible for state-funded treatment programs. In addition, we can often refer you to facilities that charge on a sliding fee scale or accept Medicare or Medicaid. If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

The service is confidential. We will not ask you for any personal information. We may ask for your zip code or other pertinent geographic information in order to track calls being routed to other offices or to accurately identify the local resources appropriate to your needs.

No, we do not provide counseling. Trained information specialists answer calls, transfer callers to state services or other appropriate intake centers in their states, and connect them with local assistance and support.

-

Suggested Resources

What Is Substance Abuse Treatment? A Booklet for Families

Created for family members of people with alcohol abuse or drug abuse problems. Answers questions about substance abuse, its symptoms, different types of treatment, and recovery. Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.

Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.It's Not Your Fault (NACoA) (PDF | 12 KB)

Assures teens with parents who abuse alcohol or drugs that, "It's not your fault!" and that they are not alone. Encourages teens to seek emotional support from other adults, school counselors, and youth support groups such as Alateen, and provides a resource list.After an Attempt: A Guide for Taking Care of Your Family Member After Treatment in the Emergency Department

Aids family members in coping with the aftermath of a relative's suicide attempt. Describes the emergency department treatment process, lists questions to ask about follow-up treatment, and describes how to reduce risk and ensure safety at home.Family Therapy Can Help: For People in Recovery From Mental Illness or Addiction

Explores the role of family therapy in recovery from mental illness or substance abuse. Explains how family therapy sessions are run and who conducts them, describes a typical session, and provides information on its effectiveness in recovery.

For additional resources, please visit the SAMHSA Store.

Last Updated: 08/30/2022

Five stages of grief. The Rise and Fall of Kübler-Ross

- Lucy Burns

- BBC

Image copyright Getty Images

Denial. Anger. Finding a compromise. Despair. Adoption. Many people know the theory according to which grief, when receiving unbearable information for a person, goes through these steps. The scope of its application is wide: from hospices to boards of directors of companies.

A recent interview with a psychologist in English on the Internet proves that the perception of the current quarantine is subject to the same rules. But do we all experience the same?

When Swiss psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross began working in American hospitals in 1958, she was struck by the lack of methods of psychological care for dying patients.

- A method that can predict your death

"Everything was impersonal, the attention was paid exclusively to the technical side of things," she told the BBC at 1983 year. “Terminally ill patients were left to their own devices, no one talked to them.”

She started a seminar with Colorado State University medical students based on her conversations with cancer patients about what they thought and felt.

Author photo, LIFE/Getty Images

Photo caption,Elisabeth Kübler-Ross talks to a woman with leukemia in Chicago, 1969. Seminar participants observe through a special mirror glass

Despite the misunderstanding and resistance of a number of colleagues, soon there was nowhere for an apple to fall at the Kübler-Ross seminars.

In 1969 she published a book, On Death and Dying, in which she quoted typical statements from her patients and then moved on to discuss how to help doomed people pass from life as free of fear and pain as possible.

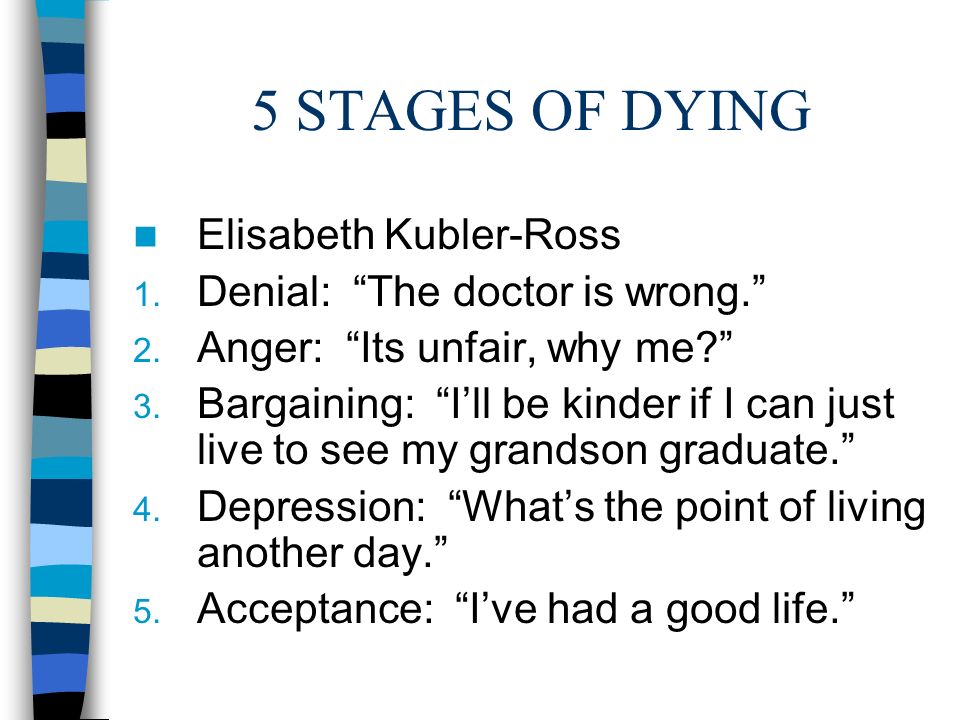

Kübler-Ross described in detail the five emotional states that a person goes through after being diagnosed with a terminal diagnosis:

- Denial: "No, that can't be true"

- Anger: "Why me? Why? It's not fair!!!"

- Bargaining: "There must be a way to save myself, or at least improve my situation! I'll think of something, I'll behave properly and do whatever is necessary!"

- Depression: "There is no way out, everything is indifferent"

- Acceptance: "Well, we must somehow live with this and prepare for the last journey"

difficult situation.

A separate chapter of the book is devoted to each of the stages. In addition to the five main ones, the author identified intermediate states - the first shock, preliminary grief, hope - from 10 to 13 types in total.

Image copyright Getty Images

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross died in 2004. Her son, Ken Ross, says she never insisted that every person must go through these five stages in sequence.

Her son, Ken Ross, says she never insisted that every person must go through these five stages in sequence.

"It was a flexible framework, not a panacea for dealing with grief. If people wanted to use other theories and models, the mother did not object. She wanted to start a discussion of the topic first," he says.

- Last will: how did the photo of a dying American touch the world?

- "You hear everything, Fernando." How was the evening in honor of the terminally ill football player

The book "On Death and Dying" became a bestseller, and Elisabeth Kübler-Ross was soon inundated with letters from patients and doctors from all over the world.

"The phone kept ringing, and the postman started visiting us twice a day," recalls Ken Ross.

The notorious five steps took on a life of their own. Following the doctors, patients and their relatives learned about them. They were mentioned by the characters of the series "Star Trek" and "Sesame Street". They were parodied in caricatures, they gave food for creativity to a lot of musicians and artists and gave rise to many successful memes.

They were mentioned by the characters of the series "Star Trek" and "Sesame Street". They were parodied in caricatures, they gave food for creativity to a lot of musicians and artists and gave rise to many successful memes.

Literally thousands of scientific papers have been written that have applied the theory of the five steps to a wide variety of people and situations, from athletes suffering career-incompatible injuries to Apple fans' worries about the release of the 5th iPhone.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

The End of History Podcast

Kübler-Ross's legacy has found its way into corporate governance: Big companies from Boeing to IBM (including the BBC) have used her "change curve" to help employees at times of great business change.

And during the coronavirus pandemic, it applies, says psychologist David Kessler.

Kessler worked with Elisabeth Kübler-Ross and co-authored her latest book, Grief and How We Grieve. His interview with the Harvard Business Review at the start of the pandemic garnered a lot of attention online as people everywhere searched for solutions to their emotional problems.

"And here, first comes denial: the virus is not terrible, nothing will happen to me. Then anger: who dares to deprive me of my usual life and force me to stay at home?! Then an attempt to find a compromise: okay, if after two weeks of social distancing it gets better, then why not? Followed by sadness: no one knows when it will end. And, finally, acceptance: the world is now like this, you have to somehow live with it, "describes David Kessler.

"As you can see, strength comes with acceptance. It gives you control: I can wash my hands, I can keep a safe distance, I can work from home," he says.

"It's a roadmap," says George Bonanno, professor of clinical psychology and head of the Loss, Trauma, and Emotion Laboratory at Columbia University. "When people are in pain, they want to know: how long will it last? What will happen to me? something to grab on to. And the five-step model gives them that opportunity."

"This scheme is seductive," notes Charles Corr, social psychologist and author of Death and Dying, Life and Being. "It offers an easy solution: sort everyone, and it takes no more than the fingers of one hand to label each one." .

George Bonanno sees this as a possible harm.

"People who don't fit exactly into these stages - and I've seen the majority of them - may decide they're grieving the wrong way, so to speak," he explains.

According to him, over the years he has seen many cases when people themselves inspired that they must certainly experience this and that, or they were convinced of this by friends and relatives, but they did not feel it and decided, that they need a doctor.

Experimental evidence of the existence of the five stages of grief is not enough. The longest and largest interview of bereaved people was conducted in 2007.

According to him, the most common state at any time is acceptance, only a few go through the stage of denial, and the second most common emotion is longing.

However, according to David Kessler, while scientists debate the nuances and terms, people who experience grief continue to find meaning in the Kübler-Ross scheme.

"I meet people who tell me, 'I don't know what's wrong with me. Now I'm angry, and a minute later I'm sad. I must be crazy.” And I say, “It has names. These are called the stages of grief.” The person says, “Oh, so there is a special stage called 'anger'? It's about me!" And feels more normal."

Image copyright, Getty Images

"People need catchy statements. If Kübler-Ross hadn't called it stages and stated that there are exactly five of them, then she probably would have been closer to the truth. But then she would not have attracted to attention," says Charles Corr.

But then she would not have attracted to attention," says Charles Corr.

He believes that talking about the five stages distracts from the main scientific legacy of Elisabeth Kübler-Ross.

"She wanted to take on the topic of death and dying in the broadest sense: how to help terminally ill people come to terms with their diagnosis, how to help those who care for them, support these patients and cope with their own emotions, how to help everyone live a full life, realizing that we are not eternal,” says Charles Corr.

"The terminally ill can teach us everything: not only how to die, but also how to live," said Elisabeth Kübler-Ross at 1983 year.

During the 1970s and 1980s, she traveled the world, giving lectures and giving workshops to thousands of people. She was a passionate supporter of the hospice idea pioneered by British nurse Cecily Saunders.

Kübler-Ross has established hospices in many countries, the first in the Netherlands in 1999. Time magazine named her one of the 100 most important thinkers of the 20th century.

Time magazine named her one of the 100 most important thinkers of the 20th century.

Professor Kübler-Ross' scientific reputation was shaken after she became fascinated with theories about the afterlife and began to experiment with mediums.

One of them, a certain Jay Barham, practiced non-standard religious-erotic therapy, in particular, he persuaded women to have sex, assuring that he was possessed by a person close to them from the afterlife. In 1979, because of this, a loud scandal arose.

In the late 1980s, she tried to set up a hospice for children with AIDS in rural Virginia, but faced strong local opposition to the idea.

In 1995, her house caught fire under suspicious circumstances. The next day Kübler-Ross had her first stroke.

She spent the last nine years of her life with her son in Arizona, moving around in a wheelchair.

In her last interview with the famous TV presenter Oprah Winfrey, she said that at the thought of her own death she feels only anger.

"The public wanted the famed expert on death and dying to be some kind of angelic personality and quickly get to the stage of acceptance," says Ken Ross. "But we all deal with grief and loss as best we can."

The theory of the five stages of grief is not widely taught in medical schools these days. It is more popular at corporate trainings under the name "Curve of Change".

Since then, there have been many theories about how to deal with your grief.

David Kessler, with the consent of Kübler-Ross's family, added a sixth stage to the five: the understanding that everything that is done makes sense.

"Understanding can come in a million different ways. Let's say I've become a better person after losing a loved one. Maybe my loved one passed away in a different way than it should have happened, and I can try to make the world a better place to this has not happened to others," says David Kessler.

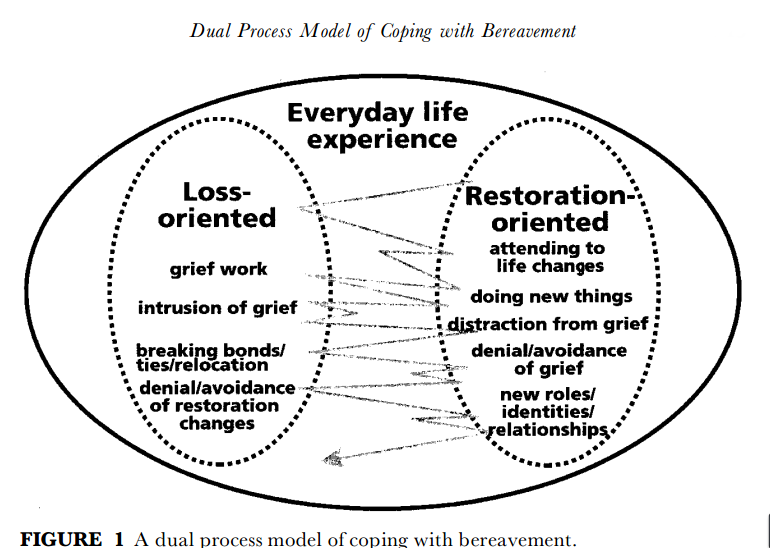

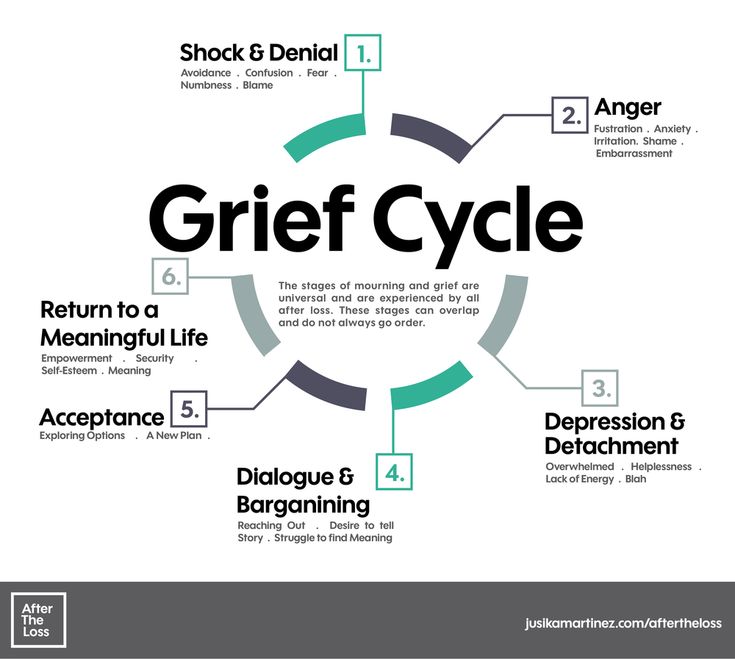

Charles Corr recommends the "double process model". It was developed by Dutch researchers Margaret Stroebe and Nenk Schut and suggests that a person in grief is simultaneously experiencing a loss and preparing himself for new things and life challenges.

It was developed by Dutch researchers Margaret Stroebe and Nenk Schut and suggests that a person in grief is simultaneously experiencing a loss and preparing himself for new things and life challenges.

George Bonanno talks about four trajectories of grief. Some people have great stamina and do not fall into depression, or it is weakly expressed in them, others remain morally broken for many years, others recover relatively close, but then a second wave of grief rolls over them, and finally, the fourth becomes stronger from the loss.

Over time, one way or another, the vast majority of people get better.

But Professor Bonanno admits that his approach is less clear-cut than the five-stage theory.

"I can say to a person: 'Time heals.' But that doesn't sound so convincing," he says.

Grief is difficult to control and hard to endure. The thought that there is some kind of road map that suggests a way out is comforting, even if it is an illusion.

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, in her latest book, Grief and How We Grieve, wrote that she did not expect to sort out the tangled human emotions.

Everyone experiences grief in their own way, even if some patterns can sometimes be deduced. Everyone goes their own way.

Stages of accepting the inevitable: what are they and how to survive them

. And how to help them survive a loved one. Psychologists adviseUpdated November 16, 2022, 10:53

Shutterstock

Each person copes with difficult circumstances in their own way. One way to get through a difficult life period is to go through all the stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. However, according to psychologists, in practice this model is not so unambiguous. There is no single recipe. But there are ways to help yourself and loved ones during this difficult time. RBC Life talked to psychologists and found out the details.

Contents

- How we accept the inevitable

- The stages of acceptance

- 5 tips

- How to help a loved one

How We Accept the Inevitable

Shutterstock

The inevitable is unforeseen events of varying degrees of drama: illness, separation, layoffs, accidents, death of relatives and friends. During a lifetime, a person can experience such difficult situations several times - and not always the range of emotions will be the same. For example, while one will hide his head in the sand and refuse to make any decisions, the other may completely evade reality - there are many scenarios. Be that as it may, psychologists are unanimous: all these reactions are normal, since in a similar way the human psyche is looking for ways to protect itself and save itself.

During a lifetime, a person can experience such difficult situations several times - and not always the range of emotions will be the same. For example, while one will hide his head in the sand and refuse to make any decisions, the other may completely evade reality - there are many scenarios. Be that as it may, psychologists are unanimous: all these reactions are normal, since in a similar way the human psyche is looking for ways to protect itself and save itself.

One way to get through a difficult situation is to accept it. From an emotional point of view, this does not at all mean “to approve or support what happened.”

Acceptance is the recognition of a new objective reality as it is. To be at this point, a person needs time - for everyone it is different.

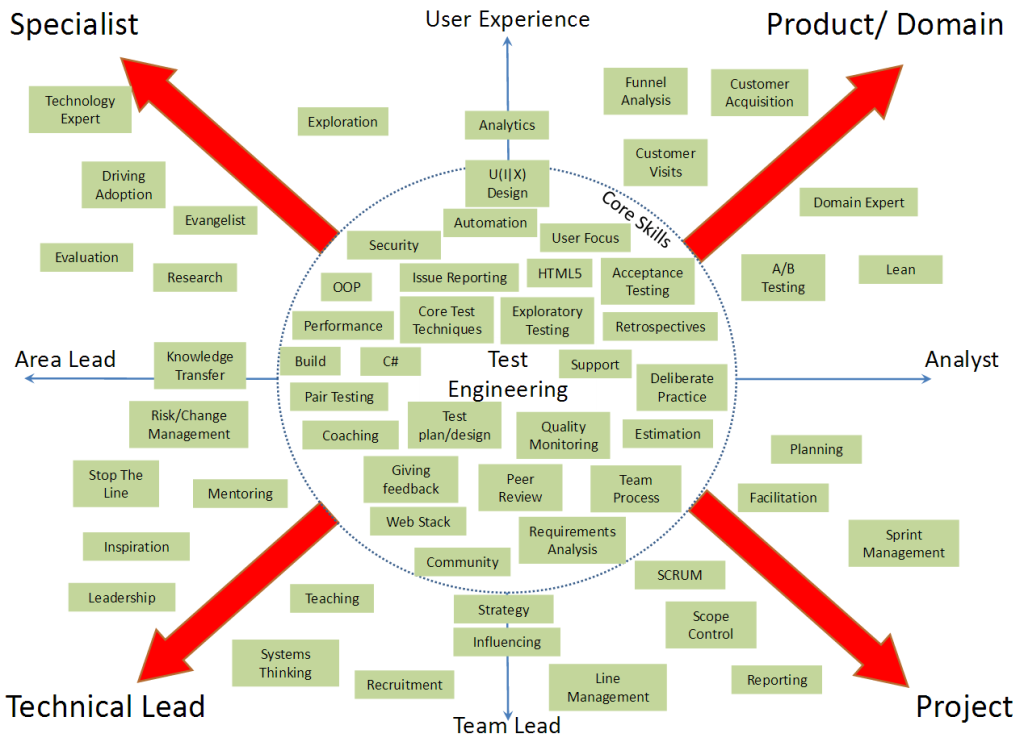

In psychology, there are at least ten models that describe the process of acceptance. Here are some of the more common examples.

- Sigmund Freud's theory of grief. The psychoanalyst saw the acceptance process as follows: breaking the connection, adjusting to new life circumstances and building new relationships [1].

- Kübler-Ross adoption stages . The most well-known theory of the five stages of acceptance is denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Often this model is perceived as linear, that is, a person sequentially goes through each of the stages. But Kübler-Ross herself noted that this is not her statement and that each individual stage may manifest itself in different ways or be completely absent [2].

- Model of two processes Strebe and Schut. An example of a cyclical model in which a person, as it were, oscillates between two states: recognizing the loss and experiencing pain, moving away from emotions and resolving practical issues caused by what is lost. These two processes are cyclically repeated, gradually healing the person [3].

- Six R Teresa Rando. Named after the first letter of each stage: Recognize, React to the separation, Recollect and re-experience, Relinquish old attachments, Readjust ) and reinvestment of emotional energy, the beginning of a new life (Reinvest) [4].

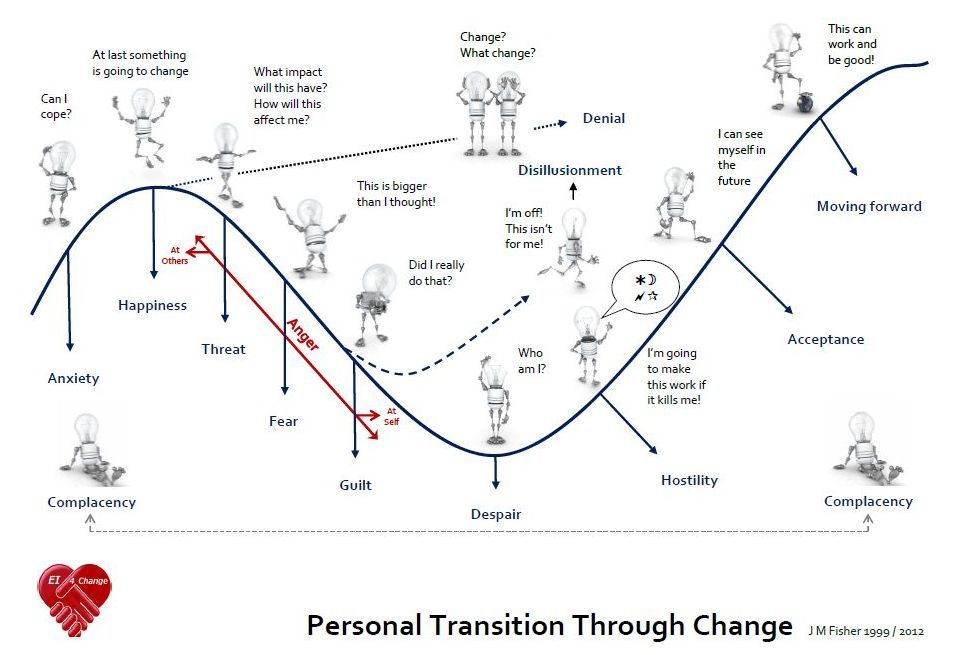

- Scott and Japhy's change curve . In this model, experiences occur along a U-shaped trajectory. The high point at the beginning is characterized by almost manic denial, shock and anger, the low point by despair and depression, the high point at the end of the curve is a recovery of energy and morale. This approach is predominantly focused on accepting events before they happen. For example, an impending dismissal or something else that does not depend on us [5].

5 stages of adoption

Shutterstock

Psychologists agree that it is often easier for the psyche of a person who is faced with severe grief or something inevitable to accept and experience something structured. “In modern practices, the Kubler-Ross stage model continues to be applied,” says Luiza Istomina, a medical psychologist at the European Medical Center. - It is used as a kind of support, helping to understand the principle of processes that replace each other. However, there is not enough empirical evidence to support or refute it. But, if it’s easier for you to accept what happened, you can focus on these stages. ”

1. Negation

A person unconsciously rejects events and begins to doubt them. For example, the laboratory mixed up the tests that confirmed a fatal illness, or the death of a loved one was reported by mistake.

Luiza IstominaMedical psychologist at the European Medical Center

“This state can last from a few seconds to several weeks, on average, by the seventh or ninth day, gradually changing to another. At this time, it is more important than ever to maintain your usual lifestyle: adhere to the sleep and wakefulness regimen, monitor nutrition, devote time to physical activity, and follow a daily routine. You can make a list of activities and activities that help relieve psycho-emotional stress: knitting, drawing, listening to music. It will be useful to use Mindfulness awareness techniques, since at the stage of denial a person may experience a feeling of detachment from the world, stupor, insensitivity.

As soon as the denial and shock begin to fade, feelings that the person has previously suppressed come out.

2. Anger

Anger and anger at the moment of grief or a disturbing event is a natural reaction. Even if it seems that anger and anger are endless, these emotions will still dissipate - and the more you truly feel them, the faster this will happen [6]. At this stage, a person may have thoughts like “why me and not someone else?” or "life isn't fair." Redirecting anger to others is dysfunctional behavior.

At this stage, as psychologists note, physical activity and sports will be especially useful. For example, Luiza Istomina recommends trying muscle relaxation techniques - Schulz's autogenic training or Ost's applied relaxation.

3. Bargaining

When something bad happens, a person can start an internal bargaining, promising to change something in himself and his life in order to improve the situation. Also at this stage, reasoning can torment, for example: "If I had left the house five minutes earlier, the accident would not have happened. "

Shutterstock

To make it easier to pass this stage, it is useful to know about one non-obvious phenomenon. It turns out that it is easier for the psyche to accept the fact that a person is to blame and he could change something. This is a kind of trick of the psyche in response to a shock event. And this is worth remembering. In reality, such an attempt to bargain with oneself is nothing more than distortion and false hope.

To understand that what happened is not your fault, try to understand the reasons for what happened. If it is a disease, study it in more detail. Having read the necessary literature and received the necessary information, one can come to the conclusion that it was simply impossible to influence the course of treatment and its outcome.

4. Depression

Depression is the emptiness that a person feels when realizing that life will no longer be the same, for example, due to a sudden change in circumstances or loss. This is a phase of acute grief that lasts six to seven weeks from the onset of a tragic event. This is a period of despair and disorganization.

Luiza Istomina:

“At this step, separation begins, detachment from the object of loss, there is a gradual entry into reality, which will then allow us to combine the image of the lost, which remained in the past, with life in the present. At this stage, destructive and self-destructive coping strategies - dangerous behavior, the use of psychoactive substances, self-harm, the emergence of anti-vital and suicidal thoughts will be alarm bells. Support from loved ones and professional advice will help here. ”

5. Acceptance of

At this point the emotions begin to stabilize as the person finally comes to terms with the fact that the new reality will now be different. In essence, we acknowledge the changes that have taken place. But this does not mean that a person evaluates them positively, just now you can live with it. To make it easier to move from depression to acceptance, you can try to learn constructive grief coping skills.

Luiza Istomina:

“Try writing down a negative automatic thought followed by cognitive restructuring (CBT approach). Example: “I can’t deal with this pain” is changed to “I have had suffering in my life, and I was able to cope with it, I need to give myself time.” Cognitive disconnection techniques (ACT-approach) can be applied. We track the depressive thought “My life will not be the same” and put it in a larger frame: “I have a thought that my life will not be the same.”

The commit process may have some backtracking. It's demotivating and can be intimidating. However, it is possible to find ways to deal with regression.

In order to experience regression, according to Albina Borisenko, a psychotherapist in the ORCT approach (solution-oriented short-term therapy), a specialist in the psychological platform Alter, one can turn to an example with a metaphor. To do this, it is necessary to imagine that the process of acceptance is a kind of path: a road, a path or a ladder.

Albina Borisenkopsychotherapist in the ORCT approach, specialist in the psychological platform Alter

“Standing at some point on this path, you can turn around and see how far you have already traveled. To regress is only to take a step or a few steps back along a path that has already been traveled. That is, to be where you already were. So, you already absolutely know exactly how to move on and what can help. It is somewhat reminiscent of a computer game, where the completed levels are clear and understandable, and going through them again is not so scary, despite the difficulties that we know about. That means you're already on your way."

5 Tips for Accepting the Inevitable

Shutterstock

Each of us is individual, so the same advice for someone will be healing, and for someone - absolutely useless. But each of us can listen to ourselves and understand what will help here and now. Here is what experts [7], [8], [9] advise.

1. Allow yourself to be sad

Expressing emotions can be an important part of the acceptance process. Don't judge yourself or compare yourself to others. Everyone mourns differently. If you suddenly feel like crying, give yourself that opportunity. There are many ways to express emotions: you can hit a punching bag or a ball for a healthy release of anger, or turn to creativity. For example, download a mobile application for music and art therapy. At the same time, write down all your feelings, experiences and thoughts in a diary. Over time, you will be able to see how your grief changes.

2. Ask for help

“Man is a social animal, and it is objectively difficult for us to survive without society,” says psychologist Borisenko. - Talking to a doctor, people in a support group, a relative or trusted friend can be a big help in a moment of grief. Don't be afraid to ask others for help and support. No, you will not be intrusive and will not lay responsibility on someone: a person always has the right to refuse. At the same time, you can always make a request – this is normal and part of human communication.”

The same applies to offers of assistance. Do not rush to refuse if someone close to you decides to help you with house cleaning, grocery shopping or laundry. It won't make you weaker.

3. Take care of your health

Get regular exercise, eat as healthy as possible, and make sure you get enough sleep. Avoid excessive use of alcohol and other psychotropic substances. All this can not only contribute to the deterioration of mental health, but also directly affect your safety. For example, avoid self-driving and other potentially dangerous activities during times of intense emotion.

4. Set small goals

Do not try to do everything at once - set small goals that are easy to achieve. “Make a list of different and most insignificant things: a cup of coffee in the morning, your favorite TV series or a walk in the park. Write down each item on how it helps the healing. Then, looking from the outside, you can see how much you do for yourself every day and how much more you can do,” says Albina Borisenko.

Also try to refrain from making major decisions, such as moving, for a while. But if this is inevitable, then, on the advice of a psychologist, the following technique will help.

Albina Borisenko:

“You shouldn't think about moving as one big “I'm moving” action. This is too big a step and therefore frightening. "I'm moving" consists of a lot of tiny steps: "I weigh the pros and cons," "I talk to my family," "I look at the list of required documents," and so on.

5. Stay Connected

Birthdays, anniversaries and holidays associated with a deceased person can cause intense feelings of grief. But do not completely cross out these days from your life. Celebrate a memorable date by lighting candles, meeting with family or raising funds for charity. Simple rituals will keep a sense of connection and emphasize that you continue to respect and appreciate the relationship that was. Keep a diary or write a letter to the person you have lost on an important date for both of you.

How to help a loved one accept the inevitable

Shutterstock

Some research suggests that the amount and quality of social support can influence the well-being of those who are grieving. The support of a loved one going through painful events can be critical to acceptance. But how to do it right? Here are some tips from experts [10].

1. Call a spade a spade

Don't be afraid to, for example, mention the name of a dead person or talk about a situation the person is going through. This will avoid the unpleasant feeling that, for example, a loved one who has passed away is forever erased from memory. In such a situation, it is better to note that you will be bored than to say formally: "I'm sorry about the loss."

2. Give practical help

Do not ask how you can help, but act. Cook dinner, buy groceries, clean the house of the person you want to help. For many people, such as those who have lost a spouse, getting used to planning and living alone can be a big challenge.

3. Avoid annoying phrases

If you ask a grieving person how things are going, the answer is obviously "Bad." Instead, you can ask, “How are you feeling today?” Also, on the advice of experts, for some time it is better to refrain from the phrases “this is the will of God / the Universe / life” or “this is for the best”, until the person who has lost loved ones says it first.

4. Be a good listener

Listen carefully, but do not give advice or judge. Perhaps, on the path of acceptance, you will have to listen to your loved one the story of loss dozens of times in the smallest detail. Don't stop the person, as talking through the situation is one way to get through it. Do not rush to give advice, especially if you are not asked for it. Often the one who mourns wants one thing - to simply be heard. Don't rush things. May your loved one recover at their own pace.