Cultural competence in therapy

Why We Need More Culturally Competent Therapists

JUL. 10, 2020

I am a Latinx (a person who is ethnically from a Latin American or Caribbean culture) living with co-occurring mental health conditions. It took quite some time for me to realize that my constant depressive state, trauma responses, insomnia and other symptoms all fall under the title of “mental health disorder.” I use disorder instead of condition because in my community, that is what it is called. Perhaps this confusion of terms is another reason why many do not come out as people living with mental illness.

I consider myself lucky. I learned about getting help for my deep anguish as a young person in high school. I am also queer, and in my late teens and early 20s, I found myself using mental health services without knowing that’s what it’s called. I didn’t know because I was connected to a multiservice agency for gay and lesbian youth in New York City.

I am now middle-aged. I realized some time ago that no matter how much mental health service I received, those who were providing therapy were not always culturally competent. They all assumed a standard therapy modality was going to work for me. Sadly, that was just wrong.

Why is Cultural Competency Important?

When I became middle-aged, my mental health declined, despite being in therapy with a trauma therapist. My therapist was a white woman who proclaimed to have worked with people with trauma histories. But she was less aware of the specific or “different” needs of a person with trauma that crossed many intersections. I don’t ever recall the therapist asking me about my racial or ethnic background, or understanding how I presented queerness as a Latinx person. I had felt for so long that no one understood me and that I was this strange, different person. And I could not endure the difficulty of a therapeutic relationship in which I had to do so much teaching.

Treating complex trauma requires many years of therapy focused primarily on safety and building a solid relationship between the therapist and the client. Unfortunately, the first therapist who attempted to deal with these complex issues could not handle the countertransference–or the emotional entanglement–with me and decided she was no longer going to work with me. This happened while I was an in-patient in 2010.

I left the hospital in search of a therapist. I looked tirelessly for a queer or person-of-color therapist, but I could not find one. I finally settled on a new white therapist who also focused on trauma but spoke a bit more about her version of intersectionality. I am still with this therapist, but also recently started with a black, male, queer therapist. I always am searching for the therapeutic connection of having someone who understands my background.

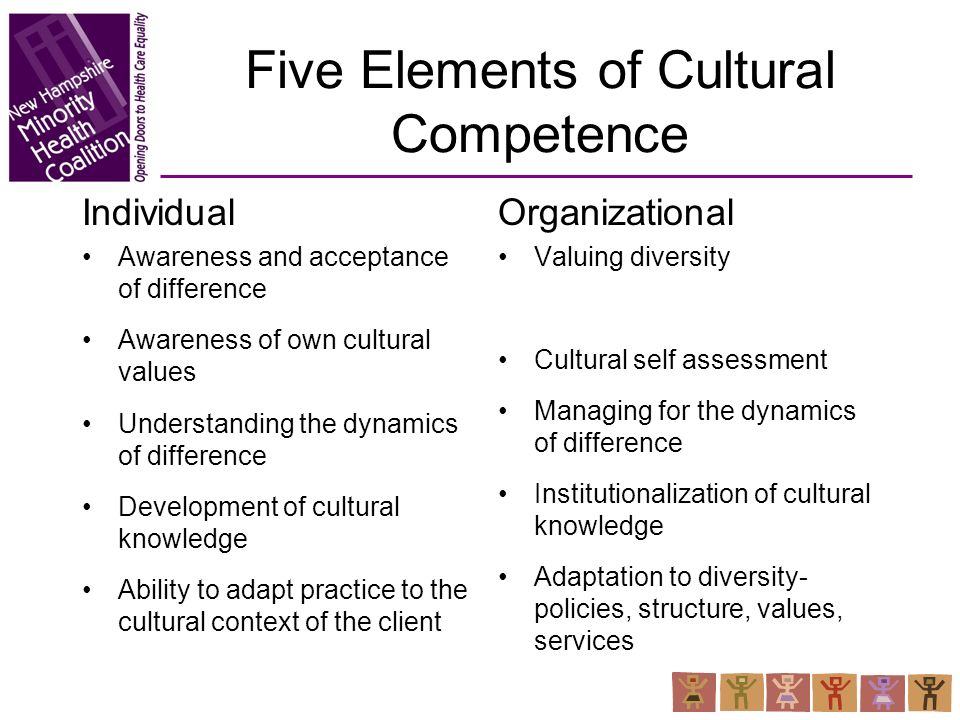

What Would Make Therapists More Culturally Competent?

I’ve learned that mental health providers still have a lot of work to do to serve people of color and people who cross many intersections, as I do.

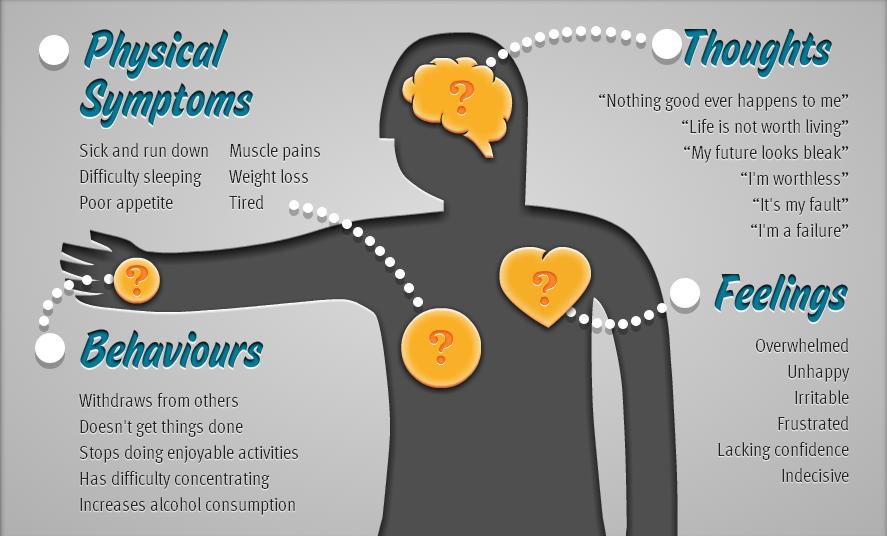

For example, it is not okay for a client to have to explain every detail for why they are distressed when depression does not present in the same way as it might for majority culture folks. My depression has at times displayed itself as anger because not only am I physically depressed, but I am also up against a society and its constant barrage of micro- and macro-level aggressions that do not allow me to be merely depressed. I also have to face the fear of racism and other discrimination as I am trying to get better.

For those who are like me—looking for mental health services that addresses their cultures and backgrounds—let us continue to ask more of those who are charged with helping us maintain our mental health. Let us continue to ask them to:

Stop saying that people of color do not seek mental health services. Many people of color don’t access mental health services because they can’t find therapists who look like them or have a language that resonates with their cultural experience. I have never had a therapist or psychiatrist who was from my community or worked in my community.

I have never had a therapist or psychiatrist who was from my community or worked in my community.

Address race in therapy sessions.If your client is from another race and ethnicity, it is wise to address that in the first sessions. Making believe that we are all just one human race does not align with how our society actually views race.

Don’t rely on a translator. Providing a translator does not mean your words are being interpreted correctly. Translation and interpretation are two different things.

Update the therapeutic method to a person’s culture. Therapy modalities should reflect a person’s background and culture–especially because the expression of some mental health disorders in people of color may be slightly different than those of the majority culture.

At this point in my life, I am lucky that I have found a queer person of color therapist that I have formed a therapeutic relationship with. While my other therapists helped me when I needed guidance and psychoeducation about all my diagnoses, it’s also important to have a therapist who simply understands. Now it’s time for more folks from different intersections to come out and be therapists for those of us who struggle because we are not seen, heard or understood.

While my other therapists helped me when I needed guidance and psychoeducation about all my diagnoses, it’s also important to have a therapist who simply understands. Now it’s time for more folks from different intersections to come out and be therapists for those of us who struggle because we are not seen, heard or understood.

Sebastian Martinez is a queer, Latinx living in a small town on the East Coast. They are also a mental health therapist primarily working with youth and adolescents with co-occurring disorders, including trauma. Sebastian lives with the co-occurring disorders of Complex PTSD and MDD. They co-parent two children.

Originally published July 2019

We’re always accepting submissions to the NAMI Blog! We feature the latest research, stories of recovery, ways to end stigma and strategies for living well with mental illness. Most importantly: We feature your voices.

Check out our Submission Guidelines for more information.

We’re always accepting submissions to the NAMI Blog! We feature the latest research, stories of recovery, ways to end stigma and strategies for living well with mental illness. Most importantly: We feature your voices.

Check out our Submission Guidelines for more information.

LEARN MORE

All You Need to Know I Psych Central

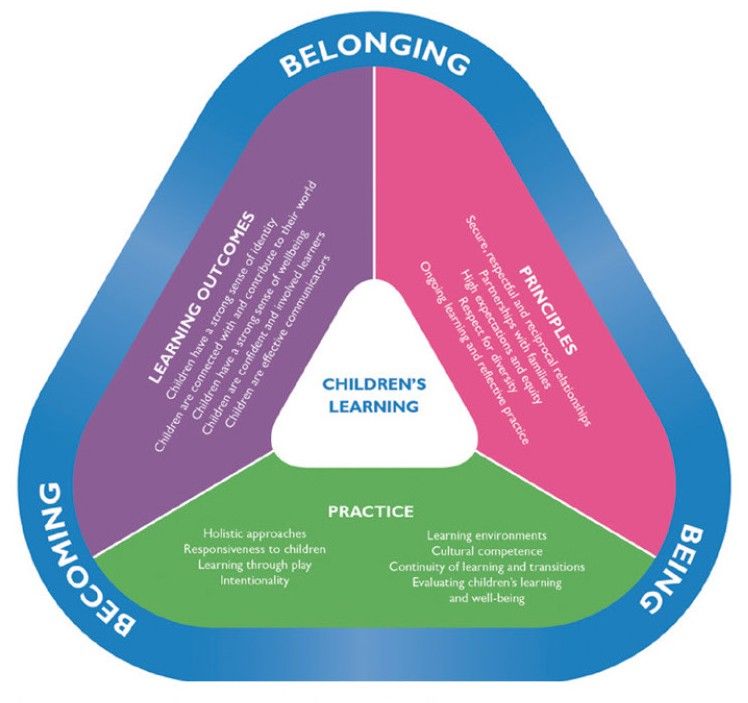

Understanding a person’s personal and cultural values, beliefs, and background can be crucial for effective therapy.

The relationship between mental health professionals and their clients is important.

They are there to make sure their clients are heard and understood, and an important part of that means understanding their client’s cultural backgrounds.

This is why it’s necessary for mental health professionals to strive for cultural competence.

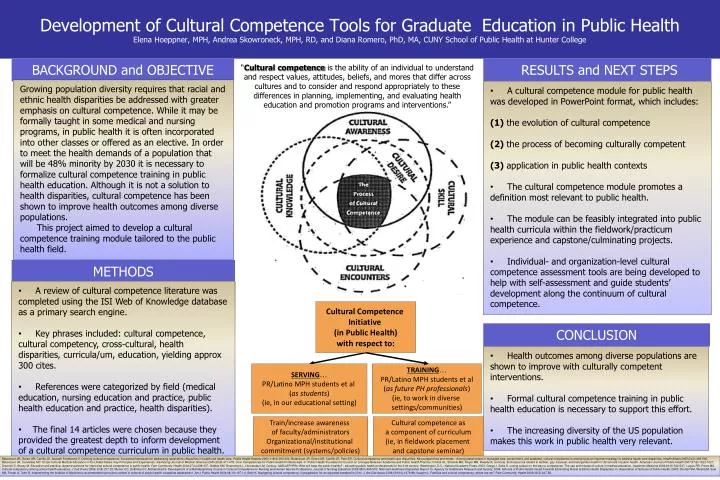

According to Ashlee Wisdom, MPH, CEO and founder of Health in Her Hue, cultural competence in therapy is:

- “care that is given to a patient that takes into account their lived experiences and their social and cultural contexts”

- “seeing all aspects of a patient and taking into account the things that they value”

In other words, cultural competence in therapy involves a mental health professional understanding the beliefs, backgrounds, and values of their clients — this includes their culture, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and sexuality.

Cultural competence in therapy also helps cross any cultural boundaries that may exist between a therapist and their client.

A culturally competent therapist will strive to understand complex issues such as oppression and microaggressions, and understand when their clients are being their most authentic selves — for example, when they use certain dialects or words that may not be considered Standard English.

Specifically, culturally competent therapists will strive to understand and address issues concerning race, sexuality, socioeconomic status, and gender in a client’s life experience.

Therapy is a personal and intimate experience between you and your therapist. It’s crucial for you to feel understood by your therapist, and for your therapist to make efforts to understand you for therapy to be effective.

Wisdom adds that cultural competence in therapy is important because it may give you the comfort to share more with your therapist.

For example, she says, “I never talked with my white doctor about the racism and microaggressions that I was dealing with because I just didn’t think she would relate to it, whereas, with my black doctor I shared so much with her. ”

”

For Wisdom, sharing the same cultural background as her doctor helped her feel more comfortable sharing certain details about her health. According to research from 2013, “racial matching,” or the shared race of a client and a mental health professional, can be used as an element of cultural competence in therapy and may lessen the chance of a person dropping out of therapy.

Although racial matching can be helpful, it isn’t necessary for therapy to be considered as having cultural competence. It’s important to be proactive about finding a therapist that responds to your specific needs when it relates to culture.

Many historically marginalized groups face challenges — such as poverty, stigmatization about going to therapy, and the potential lack of cultural awareness from those outside their culture — that may make therapy difficult without a culturally competent therapist.

In addition to these challenges, some face their own unique challenges when it comes to finding the right therapist.

Black Americans

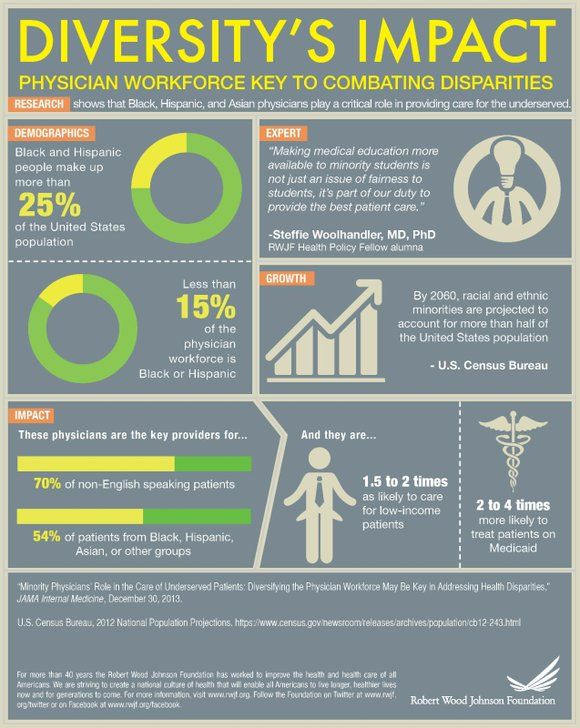

Black or African Americans are more likely to report negative emotions and symptoms than their white peers, although they’re less likely to receive treatment, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health.

A significant part of this may be due to the stigma about therapy within the community. According to a 2013 study, 63% of Black Americans view mental health issues as a sign of weakness.

It’s crucial for people to seek help from therapists who understand these issues and can help destigmatize therapy.

Wisdom echoes this by saying, “As a Black woman who goes to therapy, I may want to find a Black woman therapist because I want someone who understands the nuances of what it means to move through the world and move through the United States as a Black woman.”

Hispanic and Latinx Americans

Hispanic and Latinx communities are diverse and can include individuals from Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Central American, South American, and other backgrounds.

Depending on a person’s background within this community, there may be some cultural differences that affect the way a person interacts with their therapist, including language.

Individuals who identify as Hispanic or Latinx may be bilingual or bi-dialectal, in which case having a therapist who understands the language may be essential.

For example, a 2010 study showed that healthcare professionals misunderstood the term “nervios” as a way of describing physical tiredness when patients may have been describing symptoms of depression instead.

Indigenous Americans

Indigenous American communities are also diverse, as this term accounts for all groups who lived on what is now American land prior to European colonization.

Much like Hispanic and Latinx communities, it might be important for you to find a therapist who can understand any potential differences in language.

Also, a therapist that understands the treatment of Indigenous groups by the government might be important to you.

A history of broken treaties, forced removal from land, and assimilation may make it difficult to trust government-run mental health programs or healthcare professionals who aren’t familiar with the history and culture of Indigenous groups.

LGBTQIA+ Americans

The LGBTQIA+ community represents a wide range of identities, and the type of therapy each individual may need will vary based on their needs, goals, and symptoms.

Research shows that lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults are twice as likely as heterosexual adults to describe negative emotional symptoms, according to a 2016 review.

A 2019 review found that transgendered adults are four times as likely as cis-gender adults to have at least one mental health diagnosis.

For therapists who are training to work with transgendered individuals, it’s important to be aware of the unique challenges that may contribute to their mental health symptoms, especially those in relation to sexuality.

A culturally competent therapist will also be equipped to handle issues such as:

- coming out

- rejection from family and others

- trauma as a result of experiencing homophobia, biphobia, bullying

Other minority groups

There are other groups that may need cultural considerations when seeking or giving therapy such as:

- people with disabilities

- gender groups who face unique challenges

- those with economic disadvantages

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), a few tips to find a culturally competent therapist whom you can try include:

Doing research

- Ask family, friends, and coworkers for recommendations.

- Ask healthcare professionals for recommendations that fit the cultural characteristics you’re looking for in a therapist.

- Look online for therapists that fit your needs.

- Ask organizations within your community or check online communities for recommendations.

Asking questions

Ask your therapist if they:

- are familiar with your culture, beliefs, and values, especially toward mental health

- are willing to learn more about your culture, beliefs, and values

- have experience treating people with your cultural background

- have had cultural competence training

- plan to include cultural aspects in therapy sessions and plans

- are bilingual or bi-dialectal

Being proactive

- Give your therapist relevant information about your culture and background.

- Ask questions and do research about mental health in your community.

- Tell your therapist the role you want your family to play in your treatment.

- Be aware of how your treatment is going and if your therapist is the right fit.

There are a number of apps, services, and organizations to connect you with a culturally competent therapist.

Health in Her Hue offers access to licensed mental health professionals who specialize in dealing with cultural issues and are constantly being trained on how to provide more inclusive care.

Though the brand is marketed toward Black women and Women of Color, Wisdom notes that some of the therapists listed on the site are equipped to handle a multitude of cultural backgrounds and that “everyone is welcome to find a provider that’s the best fit for them.”

Some other resources for culturally competent therapists include:

- Black Emotional and Mental Health Collective (BEAM)

- The Trevor Project

- Latinx Therapy

- WeRNative

“If you’re a provider, it’s your job to stay equipped in providing the most inclusive and sensitive care,” Wisdom says.

Wisdom also adds that whether you’re a Black therapist, a white therapist, an Asian therapist, or a Latinx therapist, it’s important to make sure that you’re equipped and informed on providing sensitive care to all patients regardless of whether your race or cultural background matches that of your patient.

Though it’s nearly impossible to be knowledgeable in every cultural background, it’s crucial to let potential clients know upfront whether you think you might not be a great fit for them and direct them to another therapist if necessary.

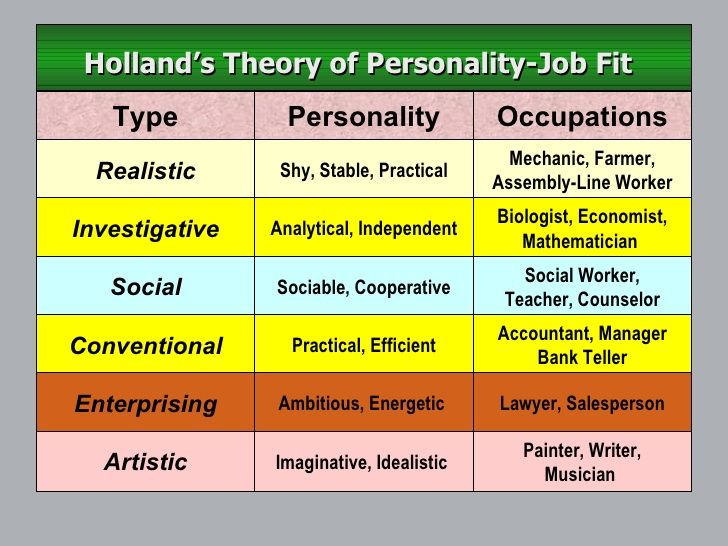

It’s also important to understand how culture impacts the type of therapy a person may be looking for.

For example, people who are from a collectivist culture — or a culture where the needs of the group trump those of an individual — might need a different approach than someone who is from an individualistic culture.

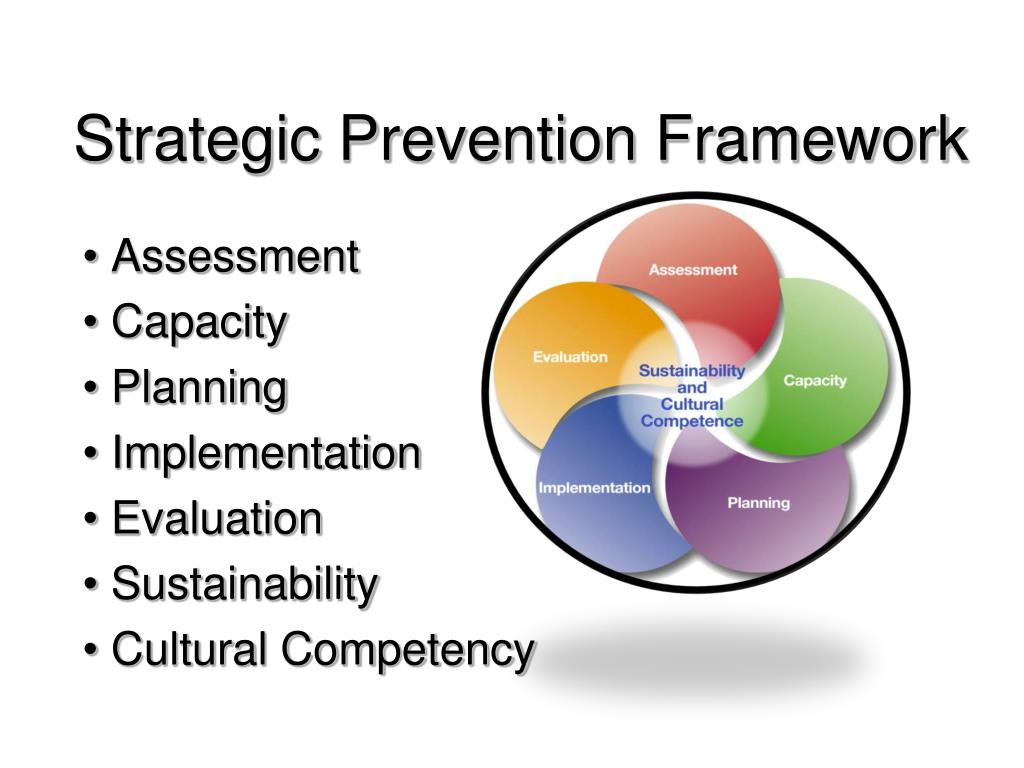

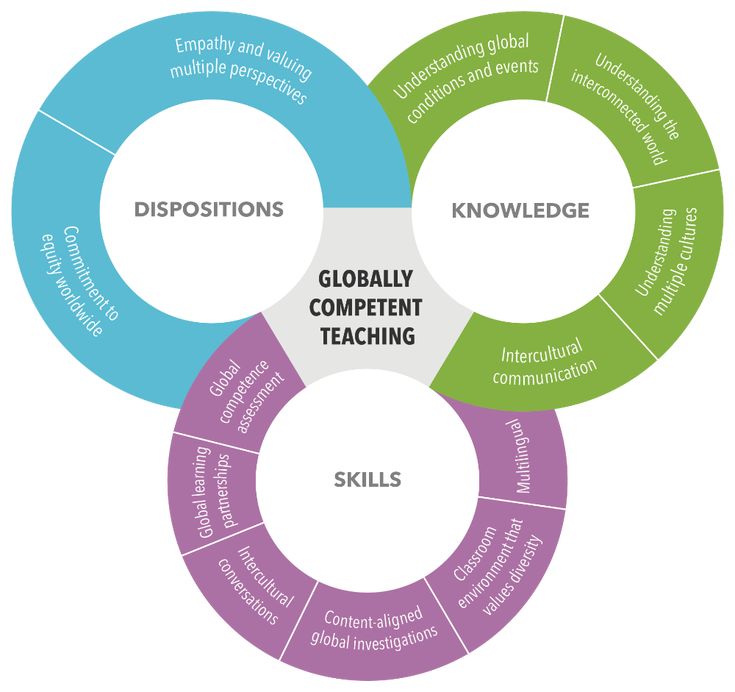

Therapists can also take cultural competence training and stay up to date on other similar training. This may help provide therapists with a wider scope of cultural knowledge, as well as lessen the chances of personal biases and thoughts — both conscious and unconscious — impacting therapy.

This may help provide therapists with a wider scope of cultural knowledge, as well as lessen the chances of personal biases and thoughts — both conscious and unconscious — impacting therapy.

Cultural competence in therapy can be beneficial to both therapists and their clients. It can help allow for a more comfortable and productive therapy session.

It can also make the client feel heard and supported and cross any cultural barriers that may exist between client and therapist.

If you’re looking for more resources, you can check out our page on Mental Health Resources for People of Color.

Cultural Competence in Nutrition and Dietetics: What We Need to Know

Culture refers to the ideas, customs and behavior of a group of people or a society (1).

It affects almost everything you do—how you talk, what you eat, what you think is right or wrong, your religious and spiritual practices, and even your attitudes toward health, healing, and healthcare.2).

However, culture is a complex and fluid concept with multiple ethno-cultural communities, identities and cross-cultural practices (1, 3).

This diversity is a challenge for the healthcare industry and health care providers, who must be properly trained and qualified to incorporate cultural nuances into their advice and recommendations.

In the field of nutrition, culturally appropriate dietary guidelines and recommendations for nutritional therapy are important.

Lack of cultural competence among nutritionists can perpetuate health inequalities and differences between marginalized and diverse communities.

This article explains everything you need to know about cultural competence in nutrition, why it's important, and steps practitioners can take to become more culturally competent.

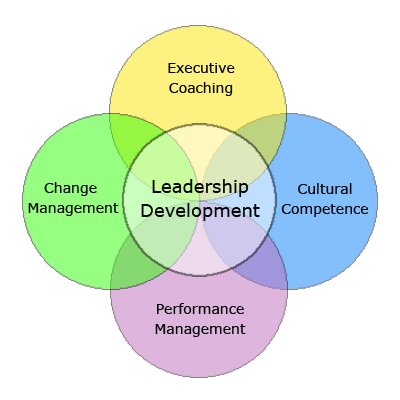

What is cultural competence?

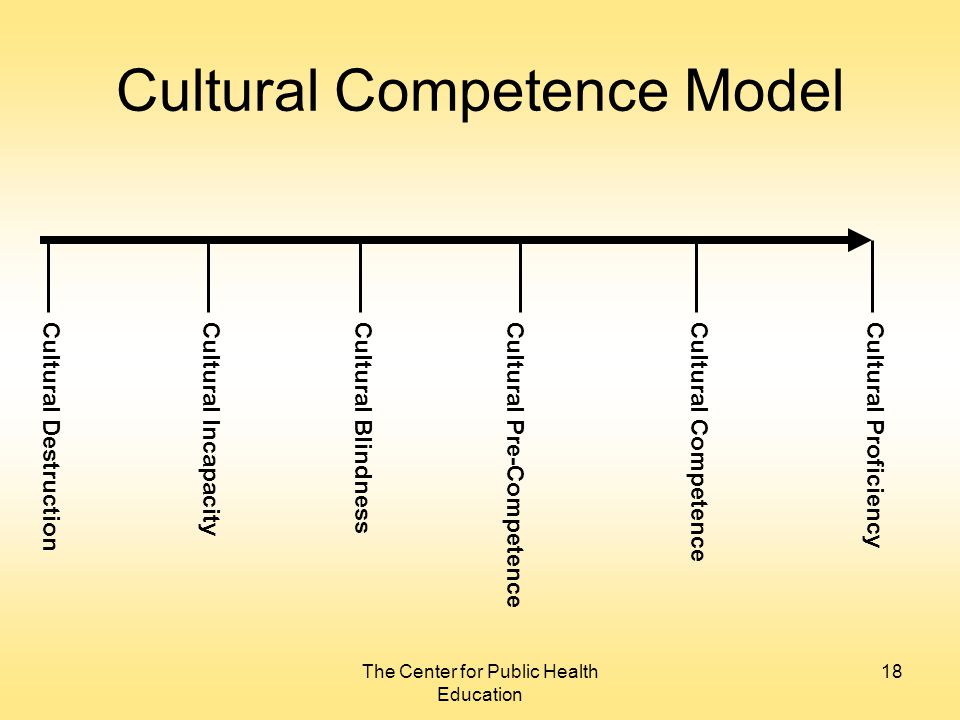

Cultural competence is the willingness and ability to treat a patient effectively and appropriately, without the influence of preconceptions, biases or stereotypes (3).

This requires respect for the views, beliefs, and values of others, as well as an appreciation of one's own and acceptance of any differences that arise.

Differences are often observed in race, ethnicity, religion and eating habits.

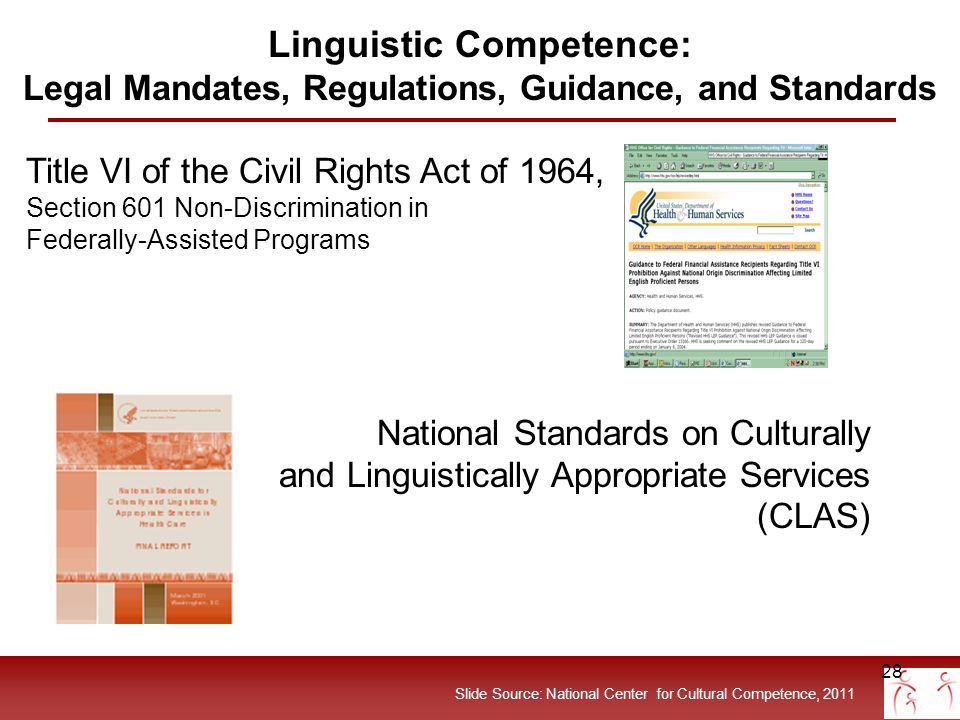

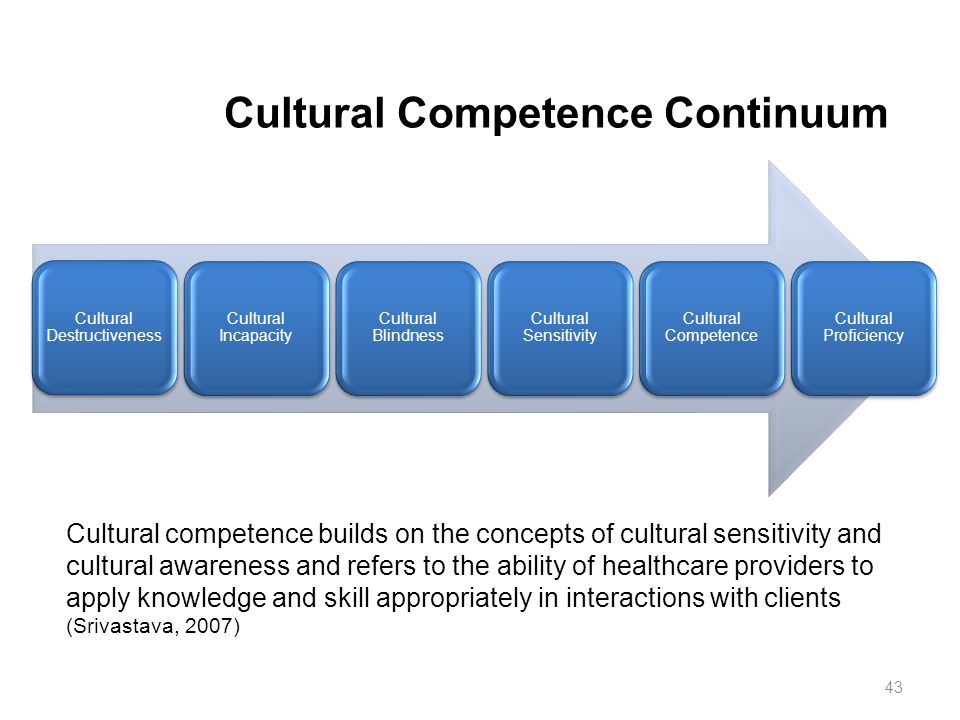

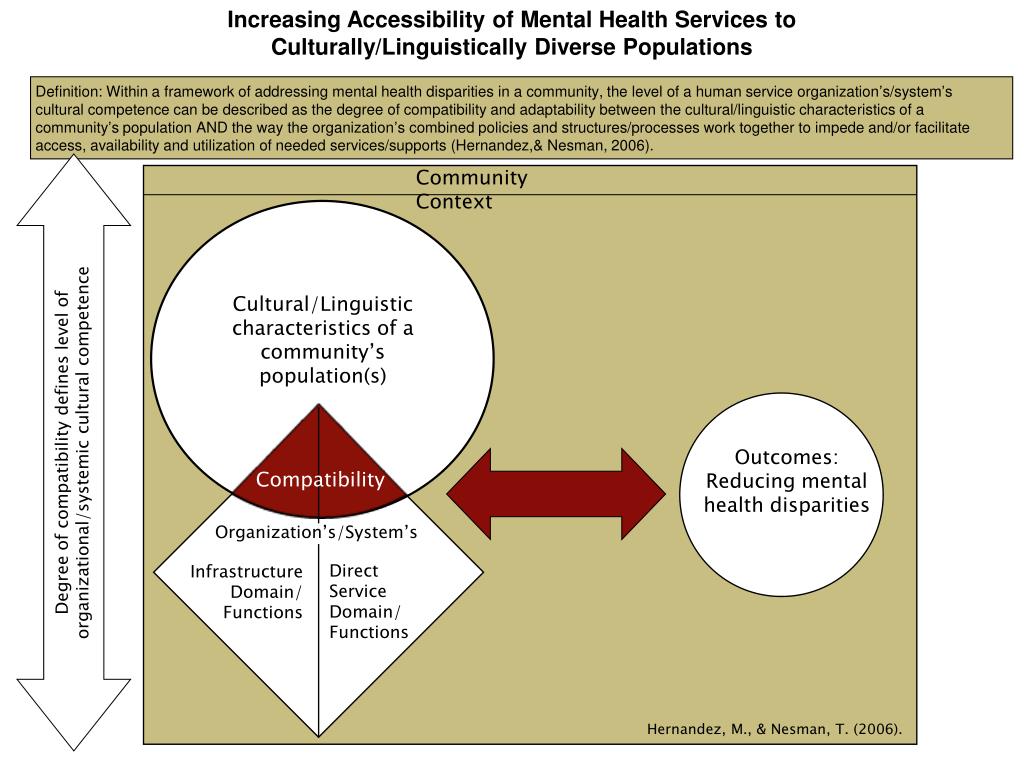

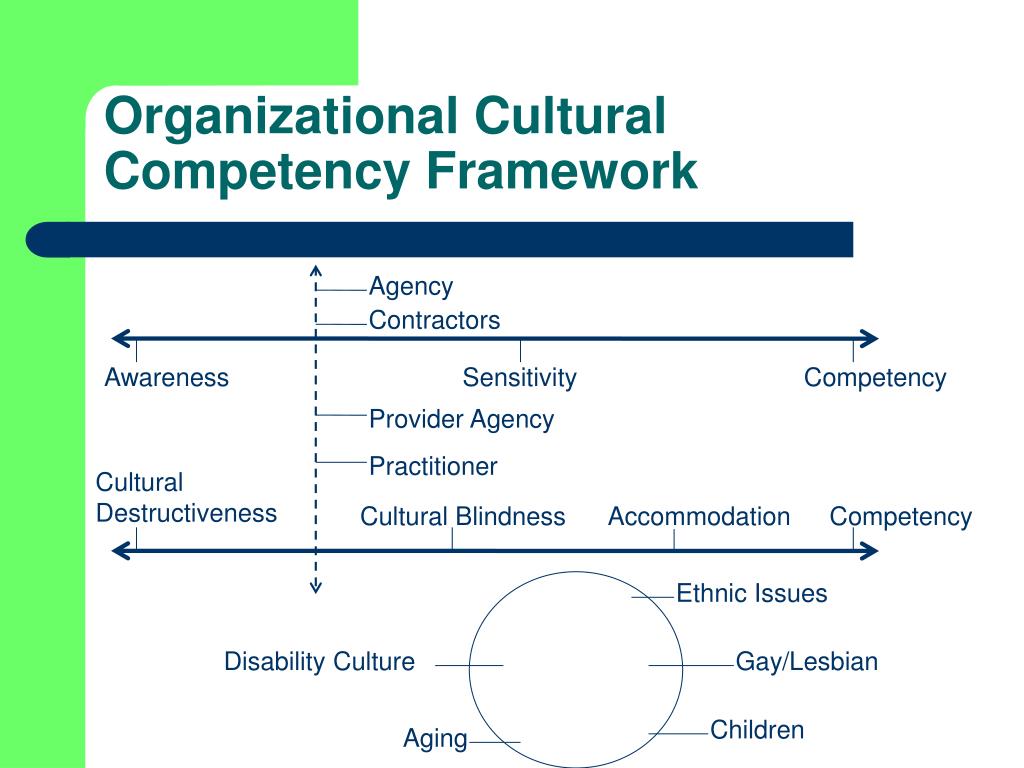

As a framework developed in the 1980s, cultural competence in the healthcare industry aims to make healthcare services more acceptable, accessible, related and effective to people from different backgrounds (1, 2).

In nutrition, this is a group of strategies to address cultural diversity and challenge the formulaic approach to nutrition education and dietary interventions among ethno-cultural communities.

This includes nutritional advice and illustrations representing different food cultures, with an expanded definition of "healthy eating".

Dietitians and nutritionists who are knowledgeable and experienced in cultural counseling methods, including culture, participate in discussions and recommendations.

They provide unbiased nutritional services that do not undermine the impact of culture on lifestyle, food choices and eating patterns.

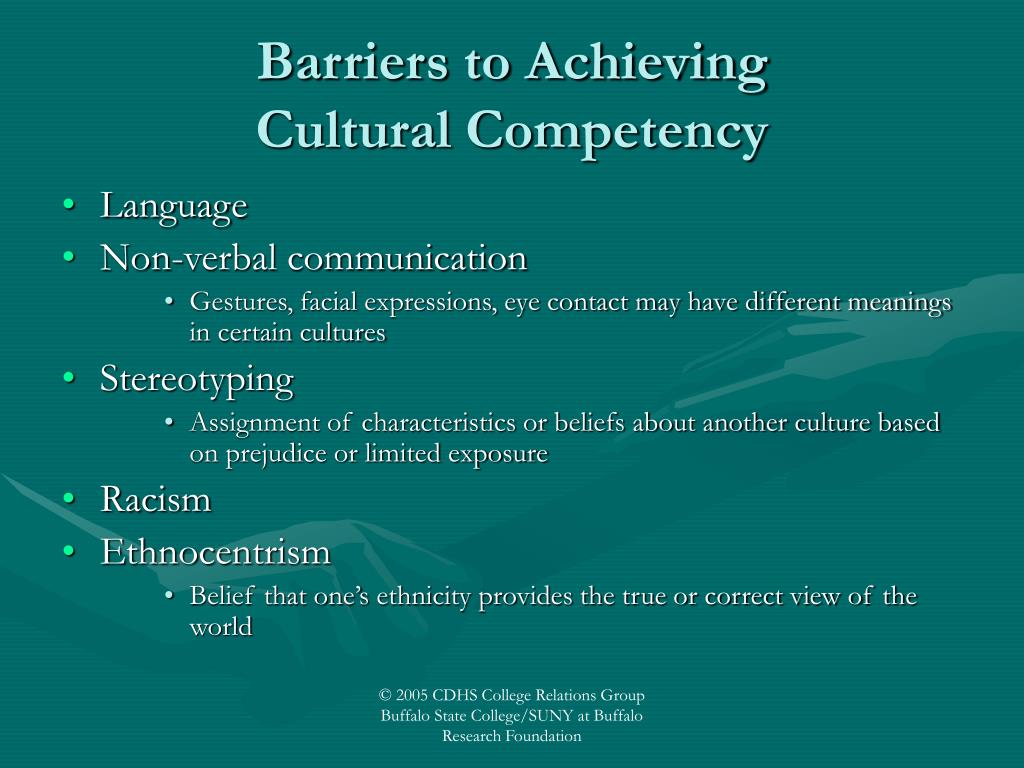

Cultural competence intersects with cultural sensitivity, awareness and cultural security, encompassing more than just race/ethnicity and religion, and care must be taken not to be mistaken based on stereotypes (1, 3).

The main goal of cultural competence is to create a system of trained health professionals capable of delivering individualized, culturally sensitive knowledge (1).

Conclusion

Cultural Competence is a framework designed to make health services more accessible and effective for different ethnic communities. This is a group of strategies that challenge the approach to nutrition education and dietary interventions.

Why is cultural competence in nutrition important?

The social determinants of health must be interpreted and understood in the context of systemic racism and how it affects different cultures and ethnic groups (3, 4).

These determinants, including socioeconomic status, education, food insecurity, housing, employment and access to food, lead to social gradients and health inequalities (1, 4).

These health inequalities and subsequent health inequalities are exacerbated among marginalized, excluded and underserved populations who may lack access to nutritious foods and food security.

Culture also influences the client's view of health and healing, their use of medications versus alternative therapies, and their food choices and diet.

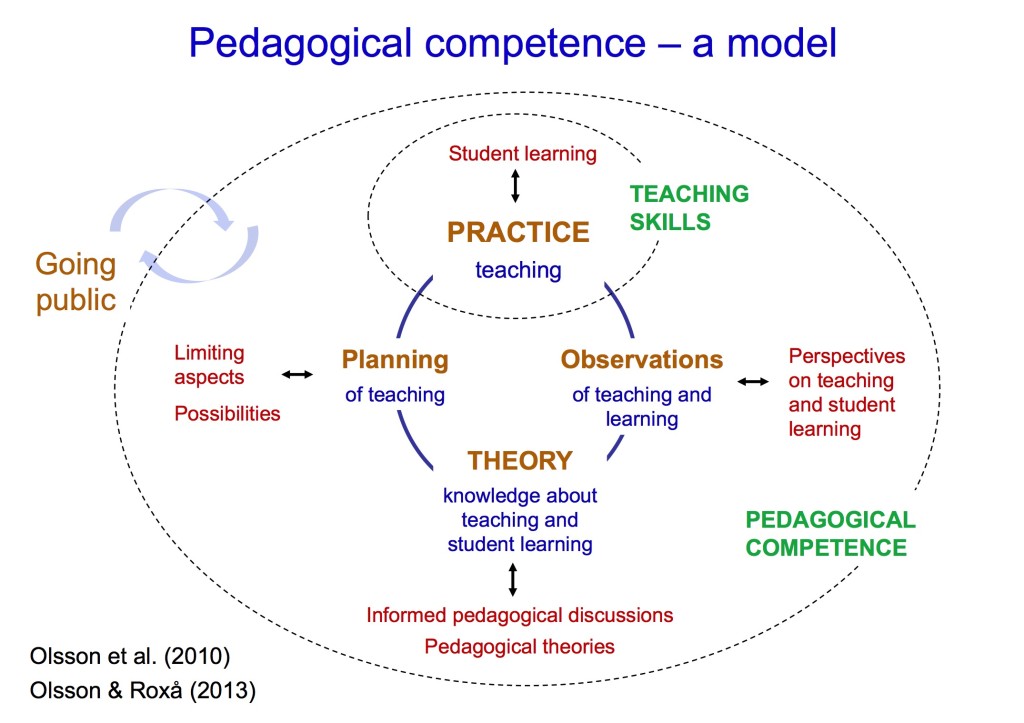

Models of cultural competence exist and are promoted through nutrition textbooks, workshops and fellowships to improve nutritionists' skills in addressing ethnocultural diversity (5).

However, clinical guidelines, nutritional planning, healthy eating and nutritional therapy are often presented out of context (1).

The encounter between dietitian and patient is defined by cultural differences, prejudices, prejudices and stereotypes (1).

If the dietitian cannot manage these differences effectively, a breakdown in trust, communication, and adherence to the meal plan can further impair health outcomes.

Dietitians and nutritionists must recognize these diverse influences in order to create a climate of trust and rapprochement with patients that will enable them to communicate an effective nutritional plan and achieve greater adherence and good health outcomes.

In addition, healthy eating looks different across ethnic and cultural communities and geographies, depending on food availability, sustainability and food culture.

Health imbalances can develop if nutritionists fail to provide culturally appropriate nutrition interventions.

Although cultural competence is not a panacea for differences in health status, better communication with the client improves health outcomes (3).

Nutritional advice must be sensitive, relevant, and effectively aligned with the client's lifestyle, living conditions, dietary needs, and food culture.

Thus, cultural competence is an important skill for both dieticians and healthcare professionals.

Conclusion

Addressing health inequities and inequities requires understanding the social determinants of health in a cultural context and reflecting them through impartial, culturally appropriate and respectful nutrition services.

What happens when there is no cultural competence?

The following are some real life scenarios that observe communication breakdowns that can be caused by cultural barriers due to inadequate or inappropriate cultural competence.

In considering these scenarios, you can consider solutions that could improve the outcome of similar events in the future.

Indian Patient v Dala

An Indian patient with high risk pregnancy and prediabetes struggles to make appropriate dietary changes to maintain blood sugar control.

Her comfort food is dhal (mashed pea soup) prepared by her mother.

On his third visit, the visibly annoyed nutritionist reiterates that the patient just needs to stop eating too many carbohydrate-rich foods and ends the consultation.

An Islamic patient and calorie counting

A patient recovering from a stroke could not communicate directly with medical professionals.

In the hospital menu there were positions unfamiliar to the patient, and his relative prepared cultural food for his consumption.

Dietitian was unable to find comparable ingredients in institutional nutrient analysis software and calorie counting was forgotten - he used "Ensure Supplement Intake" to estimate total intake.

Nigerian client and cornmeal

Unfamiliar with cornmeal - ground corn - the nutritionist did not understand the composition of the client's meals and how to make culturally appropriate recommendations.

The client also struggled to describe his meals, which used starches not commonly found in the American diet.

This and the previous scenarios present problems with cultural competence, communication and trust at the interpersonal and institutional levels.

Conclusion

Lack of cultural competence creates a barrier to effective communication. These are missed opportunities to provide appropriate nutritional interventions tailored to the patient's nutritional and health needs.

Steps to improve cultural competence

Change is needed at both institutional and individual levels, and there is evidence that it reduces health inequalities (1).

At the individual level

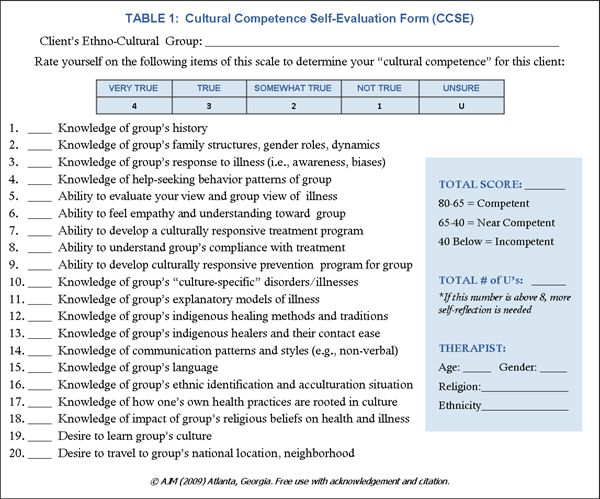

Self-assessment of one's own beliefs, values, biases, biases and stereotypes is the first step to becoming culturally competent (3).

Be aware of what you bring to the discussion - both positive and negative biases - and come to terms with the differences that may arise between you and someone from a different ethno-cultural background.

People don't have to be the same to be respected.

Here is a list to help you get started:

- Get rid of your personal biases and biases by reflecting on your own belief system.

- Acknowledge the differences your customers may have, but don't judge them by remaining neutral.

- Ask permission instead of chastising the patient. Asking “Do you mind if we talk about [insert cultural topic/behavior]” shows respect for the patient and they are more likely to be involved.

- Develop culturally appropriate interventions that are specific to the patient and not stereotypical of their ethnicity.

At the institutional level

The forms of care available in the health care system reflect the importance it places on cultural knowledge and practices (1, 2).

Inability to access culturally appropriate food and dietary services is a form of social and health inequality.

Institutions can seek to improve their engagement with and empowerment of members of marginalized communities (1).

Here are some suggestions for improving cultural competence at the institutional level:

- Recruit a diverse staff that represents the cultural diversity of patients.

- Ethnicity between dietician and patient can help the patient feel safe and understood.

- Create standards of practice that encourage nutritionists to develop culturally adapted interventions or offer patients interventions based on their own cultural backgrounds as part of their care plan.

- Consider other sources of healing that are safe and culturally appropriate for the patient.

- Include culturally sensitive dietary advice, including set meals, as these are part of some immigrant and ethnocultural eating patterns.

Conclusion

Change is needed at both the individual and institutional levels to create culturally competent dietitians and nutritionists, and a supportive health care environment that can reduce health inequalities.

Does cultural competence go far enough?

Some sources argue that cultural competence is not enough—that simply educating nutritionists and nutritionists about cultural differences is not enough to stop stereotyping and influence change (1).

In addition, some cultural competence movements may be purely cosmetic or superficial.

The concepts of cultural security and cultural humility have been proposed as more inclusive and systematic approaches to eliminating institutional discrimination (1).

Cultural safety goes beyond the ability of the individual nutritionist to create a work environment that is a safe cultural space for the patient, sensitive and responsive to their different belief systems (1).

Meanwhile, cultural humility is seen as a more reflective approach that goes beyond the mere acquisition of knowledge and includes a continuous process of self-exploration and self-criticism, combined with a willingness to learn from others (6).

Degrading or depriving a patient of a cultural identity is considered a culturally unsafe practice (7).

However, while some patients may feel safe and understood about the institutional cultural competence and ethnic fit of nutritionist and patient, others may feel isolated and racially stigmatized (1).

Incorporating cultural competence into clinical practice can also increase consultation time as it requires more dialogue with the patient.

Interestingly, not every non-Western practice will be the best intervention.

It is important to move away from the notion that any one style of eating is bad - as Western food is demonized - to consideration of eating patterns that can be harmful regardless of origin.

Conclusion

Cultural competence has flaws that create additional challenges for its institutionalization, including cosmetic movements, lack of inclusiveness, and unintended biases.

Organizations advocating for cultural competence in nutrition

Within the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND) and independent organizations, several interest groups advocate for the diversification of nutrition to make it inclusive. This includes:

This includes:

- National Organization of Black Nutritionists (NOBIDAN). This professional association provides a forum for the professional development and promotion of nutrition, optimal nutrition and well-being for the general public, especially for people of African descent.

- Hispanics and Latinos in Diet and Nutrition (LAHIDAN). Their mission is to enable members to become leaders in food and nutrition for Hispanics and Hispanics.

- Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) and Nutrition and Dietetics Indian (IND). Their core values are the defense of cultural themes and cultural approaches to nutrition and dietetics.

- Diversify your diet (DD). They strive to increase racial and ethnic diversity in nutrition by empowering nutrition leaders of color and helping aspiring nutritionists of color with financial aid and internship applications.

- Nutritionists for food justice.

This Canadian network of dietitians, nutritional trainees and students addresses food inequities. Members work to create an anti-racist and fair approach to food access in Toronto and beyond.

This Canadian network of dietitians, nutritional trainees and students addresses food inequities. Members work to create an anti-racist and fair approach to food access in Toronto and beyond. - Growing Resilience in the South (GRITS). A non-profit organization that bridges the gap between nutrition and culture by providing free nutrition counseling to vulnerable populations and programs for nutritionists and students to improve their understanding of African American cultural foods.

Conclusion

Member interest groups and other non-academic organizations emphasize the role of nutritionists as advocates for cultural competence in nutrition and access to food.

Bottom line

Cultural competence is the willingness and ability to provide impartial, unbiased nutritional services to people and clients from diverse cultural backgrounds.

Cultural competence and cultural security intersect and require institutional changes to facilitate forms of assistance available to minorities and marginalized communities.

However, culture is a fluid concept, and nutritionists and dieticians should not assume that every member of a particular ethnic group identifies and observes the well-known cultural practices of that group. They may have adapted their own values and methods.

Nutritionists must remain impartial and engage clients in meaningful conversations that provide them with the information they need to provide culturally appropriate and respectful advice.

Nutrition: why cultural competence matters

Culture refers to the ideas, customs and behavior of a group of people or a society.

It affects almost everything you do, the way you talk, the foods you eat, what you think is right or wrong, your religious and spiritual practices, and even your attitude towards health, healing and medical care.

However, culture is a complex and fluid concept with multiple ethnocultural communities, identities and intercultural practices.

This diversity is a challenge for the sector and health care providers, who need to be appropriately educated and prepared to take into account cultural nuances in their advice and recommendations.

In the field of nutrition, culturally appropriate dietary guidelines and recommendations for nutritional therapy are important.

Lack of cultural competence among nutritionists can perpetuate health inequalities and differences between marginalized and diverse communities.

In this article, we explain everything you need to know about cultural competence in nutrition, why it's important, and steps clinicians can take to become more culturally competent.

What is cultural competence?

Cultural competence is the willingness and ability to treat a patient effectively and appropriately without being influenced by biases, biases or stereotypes.

This requires respect for the views, beliefs, and values of others, while valuing one's own and accommodating any differences that arise.

Differences are often observed in race, ethnicity, religion and dietary practices.

As a framework developed in the 1980s, cultural competence in the healthcare industry aims to make healthcare services more acceptable, accessible, recognizable and effective for people of different backgrounds.

In the field of nutrition, this is a group of strategies to address cultural diversity and counter the widespread approach to nutrition education and dietary interventions among ethno-cultural communities.

This includes nutritional advice and illustrations depicting different food cultures, with an expanded definition of "healthy eating".

It brings together knowledgeable nutritionists and nutritionists, as well as specialists in cultural counseling methods, including a cultural component in discussions and recommendations.

They provide unbiased nutritional services that do not undermine the impact of culture on lifestyle, food choices and eating habits.

Cultural competence intersects with cultural sensitivity, cultural awareness and security, encompassing more than just race/ethnicity and religion, and tries not to be labeled based on stereotypes.

One of the main goals of cultural competence is to create a system of trained health professionals who can provide specialized and culturally sensitive knowledge.

SUMMARY

Cultural Competence is a concept designed to make healthcare services more accessible and effective for different ethnic communities. This is a group of strategies that challenge the approach to nutrition education and dietary interventions.

Why is cultural competence important in nutrition?

The social determinants of health must be interpreted and understood in the context of systemic racism and how it affects different cultures and ethnic groups.

These determinants, including socioeconomic status, education, food insecurity, housing, employment and access to food, lead to social ladders and health inequalities.

These inequalities, and the resulting health disparities, are exacerbated among marginalized, disadvantaged and underserved populations who may lack access to nutritious food and food security.

Culture also influences the client's perspective on health and healing, medication use versus alternative therapies, and their food choices and diet.

There are models of cultural competence that are promoted through nutritional guides, fellowships, and fellowships to improve the skills of nutritionists in relation to ethnocultural diversity.

However, clinical guidelines, nutritional planning, healthy eating and nutritional therapy are often presented out of context.

The encounter between dietician and patient is defined by differences in their cultures, prejudices, prejudices and stereotypes.

If the dietitian fails to deal effectively with these differences, poor health outcomes may be further aggravated by breaches of trust, communication, and adherence to the meal plan.

Dietitians and nutritionists must recognize these various influences in order to build trust and rapport with patients that will enable them to communicate an effective nutritional plan and lead to greater adherence and good health outcomes.

In addition, healthy eating looks different across ethnic and cultural communities and geographies, depending on food availability, sustainability and food culture.

Health inequalities can develop if nutritionists do not provide culturally competent nutrition interventions.

While cultural competence is not a panacea for health inequalities, deeper communication with clients improves health outcomes.

Nutrition counseling must be sensitive, relevant and effectively tailored to the client's lifestyle and living conditions, dietary needs and food culture.

Thus, cultural competence is an important skill for both dieticians and healthcare professionals.

SUMMARY

To address inequities and disparities in health, the social determinants of health must be understood in a cultural context and reflected in impartial, culturally appropriate and respectful nutrition services.

What if there is no cultural competence?

Here are some real life scenarios that look at communication disruption that can be caused by cultural barriers due to inadequate or inappropriate cultural competence.

After studying these scenarios, you can consider solutions that could improve the outcome of similar events in the future.

Indian Patient v Dala

An Indian patient with a high risk pregnancy and prediabetes struggles to make appropriate dietary changes to control her blood sugar levels.

His home meal is dhal (mashed pea soup) prepared by his mother.

On his third visit, the visibly annoyed nutritionist reiterates that the patient just needs to stop eating too many carbohydrate foods and ends the consultation.

An Islamic patient and calorie counting

A patient recovering from a stroke could not communicate directly with medical professionals.

The hospital menu contained foodstuffs unknown to the patient, and a family member prepared cultural food for him.

The dietitian was unable to find similar ingredients in institutional nutrient analysis software and was forced to abandon calorie counting using the Provision supplement to estimate total intake.

Nigerian customer and cornmeal

Unfamiliar with cornmeal (ground corn), the nutritionist did not understand the composition of the client's meals and how to make culturally appropriate recommendations.

The client also struggled to describe his meals, which use starches not commonly found in the American diet.

This and the previous scenarios present issues of cultural competence, communication and trust at the interpersonal and institutional levels.

SUMMARY

Lack of cultural competence creates a barrier to effective communication. This results in missed opportunities to provide appropriate nutritional interventions tailored to the patient's nutritional and health needs.

Cultural awareness measures

Change is needed at both institutional and individual levels, and there is evidence that it reduces health inequalities.

Individual Level

Conducting a self-assessment of one's own beliefs, values, biases, biases and stereotypes is the first step to becoming culturally competent.

Be aware that you bring both positive and negative biases to this and accept the differences that may arise between you and someone from a different ethno-cultural background.

People do not need to be equal to be respected.

Here is a list to help you get started:

- Eliminate your personal biases and biases by reflecting on your own belief system.

- Acknowledge the differences your customers may have, but don't judge them, instead remain neutral.

- Ask permission instead of scolding the patient. Asking, "Do you mind if we talk about [insert cultural/behavioral issue]", this shows respect for the patient and makes them more willing to participate.

- Develop culturally appropriate interventions specific to the patient rather than stereotyped by their ethnicity.

Institutional level

The forms of care available in the health care system reflect the importance it places on cultural knowledge and practices.

Inability to access culturally appropriate nutrition and dietary services is a form of social and health inequality.

Institutions can try to improve how they interact with and empower members of marginalized communities.

The following are some suggestions for improving cultural competence at the institutional level:

- Recruit a diverse staff that represents the cultural diversity of patients.

- Ethnic compatibility between dietitian and patient can help the patient feel safe and understood.

- Create standards of practice that encourage nutritionists to design culturally sensitive interventions or offer patients interventions based on their own cultural background as part of their treatment plan.

- Refer to other sources of healing that are safe and culturally appropriate for the patient.

- Include culturally sensitive dietary recommendations, including one-dish meals (eg chili peppers) as they are part of the different eating patterns of immigrants and ethnic cultures.

SUMMARY

Change is needed at both the individual and institutional levels to create culturally competent nutritionists and nutritionists, and to create an enabling health care environment to reduce health inequalities.

Is cultural competence sufficient?

Some sources argue that cultural competence is not enough, that it is not enough to simply educate nutritionists and nutritionists about cultural differences to stop stereotyping and influence change.

In addition, some changes in cultural competencies may be purely cosmetic or superficial.

The concepts of cultural security and cultural humility have been proposed as a more inclusive and systematic approach to addressing institutional discrimination.

Cultural safety goes beyond the ability of the individual nutritionist to create a work environment that is a safe cultural space for the patient, sensitive and receptive to their different belief systems.

Cultural humility, meanwhile, is seen as a more thoughtful approach that goes beyond mere acquisition of knowledge to include a continuous process of self-examination and self-criticism, combined with a willingness to learn from others.

Degrading or depriving a patient of cultural identity is considered a culturally unsafe practice.

However, while some patients may feel secure and understood in terms of institutional cultural competence and ethnic fit with the nutritionist, others may feel isolated and racially biased.

Incorporating cultural competence into clinical practice can also increase consultation time as it requires a closer dialogue with the patient.

Interestingly, not all non-Western practices will be the best intervention.

It is important to move away from the notion that any style of eating is bad, how Western food is demonized, and towards eating patterns that can be harmful, regardless of their origin.

SUMMARY

Cultural competition has flaws that create new challenges for its institutionalization, including cosmetic steps, lack of engagement, and unintended bias.

Cultural Diet Competence Organizations

Within the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND) and independent organizations, various interest groups are advocating the diversification of nutrition to make it inclusive. This includes:

- National Organization of Black Dietitians (NOBIDAN). This professional association provides a forum for the professional development and promotion of nutrition, optimal nutrition and wellness for the general public, especially for people of African descent.

- Hispanics and Latinos in Diet and Nutrition (LAHIDAN). Its mission is to enable members to become leaders in food and nutrition for Hispanics and Hispanics.

- Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) and Nutrition and Dietetics Indian (IND). Its core values are the defense of cultural issues and approaches in nutrition and dietetics.

- Diversify Diet (DD). Its goal is to increase racial and ethnic diversity in nutrition by providing financial assistance and internship applications to leading and emerging nutritionists of color.

- Nutritionists for food justice. This Canadian network of dietitians, nutritional trainees and students addresses issues of food injustice. Its members work to create an anti-racist and fair approach to food access in Toronto and beyond.

- Growing Resilience in the South (GRITS). A non-profit organization that bridges the gap between nutrition and culture by providing free nutritional advice to vulnerable populations, as well as programs for nutritionists and students to improve their understanding of African American cultural foods.

SUMMARY

Member interest groups and other non-academic organizations are making important changes to the role of nutritionists as advocates for cultural competence in nutrition and access to food.

In conclusion

Cultural competence is the willingness and ability to provide impartial and unbiased nutrition services to people and clients from different cultures.