Coping with trauma related dissociation pdf

Coping with trauma-related dissociation : skills training for patients and their therapists : Boon, Suzette : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

Item Preview

EMBED (for wordpress.com hosted blogs and archive.org item <description> tags) [archiveorg copingwithtrauma00boon width=560 height=384 frameborder=0 webkitallowfullscreen=true mozallowfullscreen=true]

Want more? Advanced embedding details, examples, and help!

texts

- by

- Boon, Suzette; Steele, Kathy; Hart, Onno van der, 1941-

- Publication date

- 2011

- Topics

- Dissociative disorders, Psychic trauma, Post-traumatic stress disorder

- Publisher

- New York : W. W. Norton

- Collection

- inlibrary; printdisabled; internetarchivebooks; toronto

- Digitizing sponsor

- Internet Archive

- Contributor

- Internet Archive

- Language

- English

"A Norton professional book. " --Prelim. p

Includes bibliographical references (p. [455]-460) and index

- Access-restricted-item

- true

- Addeddate

- 2014-01-14 20:17:11.283815

- Bookplateleaf

- 0002

- Boxid

- IA1779306

- Camera

- Canon EOS 5D Mark II

- City

- New York

- Donor

- Book Drive

- Edition

- 1st ed.

- External-identifier

- urn:oclc:record:1028561487

urn:lcp:copingwithtrauma00boon:lcpdf:38ef2ead-fc83-4a0f-8dfb-44341cb55082

- Extramarc

- University of Alberta Libraries

- Foldoutcount

- 0

- Identifier

- copingwithtrauma00boon

- Full catalog record

- MARCXML

Reviewer:everwand - favoritefavoritefavoritefavoritefavorite - February 14, 2020

Subject: This book changed my life.

i had no idea how to navigate my disorder until i spotted this book on a councellor's shelf and asked to borrow it. This book is a godsend for those of us living with dissociative disorders and are unable to cope.

Anyone struggling to get access to this book, reach out to me, I'll get you an e-book of it - just as that councellor gave to me when I told her how much this book meant to me.

Terms of Service (last updated 12/31/2014)

Summary of Suzette Boon, Kathy Steele & Onno van der Hart's Coping with Trauma-Related Dissociation by IRB Media - Ebook

Ebook101 pages52 minutes

Rating: 0 out of 5 stars

()

About this ebook

Please note: This is a companion version & not the original book. Book Preview:

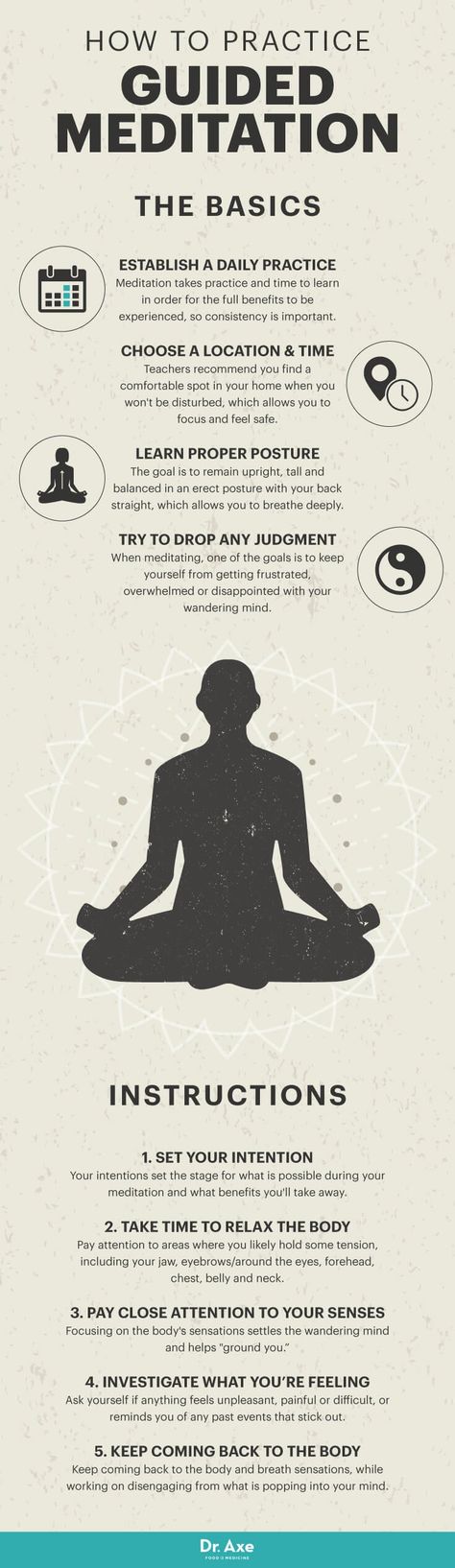

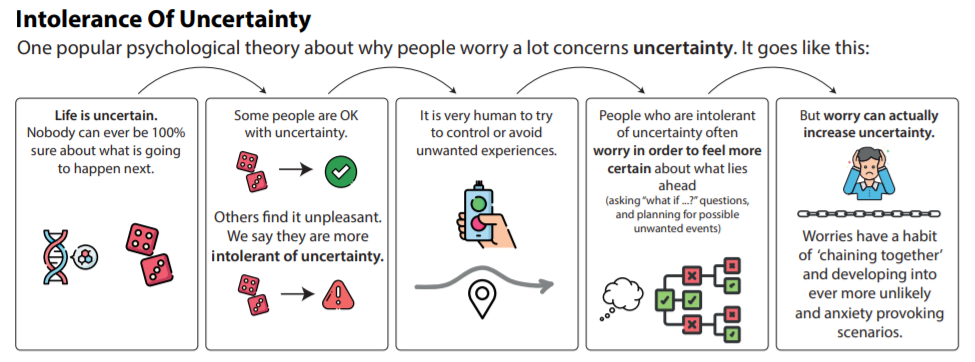

#1 You will begin by learning how to stay present. Once you have practiced the exercise suggested for being present, you can read about dissociation in the chapter.

#2 Being in the present is essential to learning, growing, and healing from a dissociative disorder. You may encounter a number of problems that interfere with being present, such as being under stress or faced with a painful conflict or intense emotion.

You may encounter a number of problems that interfere with being present, such as being under stress or faced with a painful conflict or intense emotion.

#3 Pay attention to the details of the room around you. Notice three objects that you see, and describe their characteristics out loud to yourself. Notice three sounds that you hear, and describe their qualities out loud to yourself. Finally, touch three objects and describe how they feel.

#4 To help you focus on the present, try focusing on the sounds, smells, tastes, and touches around you. You can also take time to slow and regulate your breathing.

Skip carousel

LanguageEnglish

PublisherIRB Media

Release dateJun 6, 2022

ISBN9798822532076

Author

IRB Media

With IRB books, you can get the key takeaways and analysis of a book in 15 minutes. We read every chapter, identify the key takeaways and analyze them for your convenience.

Related categories

Skip carousel

Reviews for Summary of Suzette Boon, Kathy Steele & Onno van der Hart's Coping with Trauma-Related Dissociation

Rating: 0 out of 5 stars

0 ratings

0 ratings0 reviews

Book preview

Summary of Suzette Boon, Kathy Steele & Onno van der Hart's Coping with Trauma-Related Dissociation - IRB Media

Insights on Suzette Boon and Kathy Steele & Onno van der Hart's Coping with Trauma-Related Dissociation

Contents

Insights from Chapter 1

Insights from Chapter 2

Insights from Chapter 3

Insights from Chapter 4

Insights from Chapter 5

Insights from Chapter 6

Insights from Chapter 7

Insights from Chapter 8

Insights from Chapter 9

Insights from Chapter 10

Insights from Chapter 11

Insights from Chapter 12

Insights from Chapter 13

Insights from Chapter 1#1

You will begin by learning how to stay present. Once you have practiced the exercise suggested for being present, you can read about dissociation in the chapter.

Once you have practiced the exercise suggested for being present, you can read about dissociation in the chapter.

#2

Being in the present is essential to learning, growing, and healing from a dissociative disorder. You may encounter a number of problems that interfere with being present, such as being under stress or faced with a painful conflict or intense emotion.

#3

Pay attention to the details of the room around you. Notice three objects that you see, and describe their characteristics out loud to yourself. Notice three sounds that you hear, and describe their qualities out loud to yourself. Finally, touch three objects and describe how they feel.

#4

To help you focus on the present, try focusing on the sounds, smells, tastes, and touches around you. You can also take time to slow and regulate your breathing.

#5

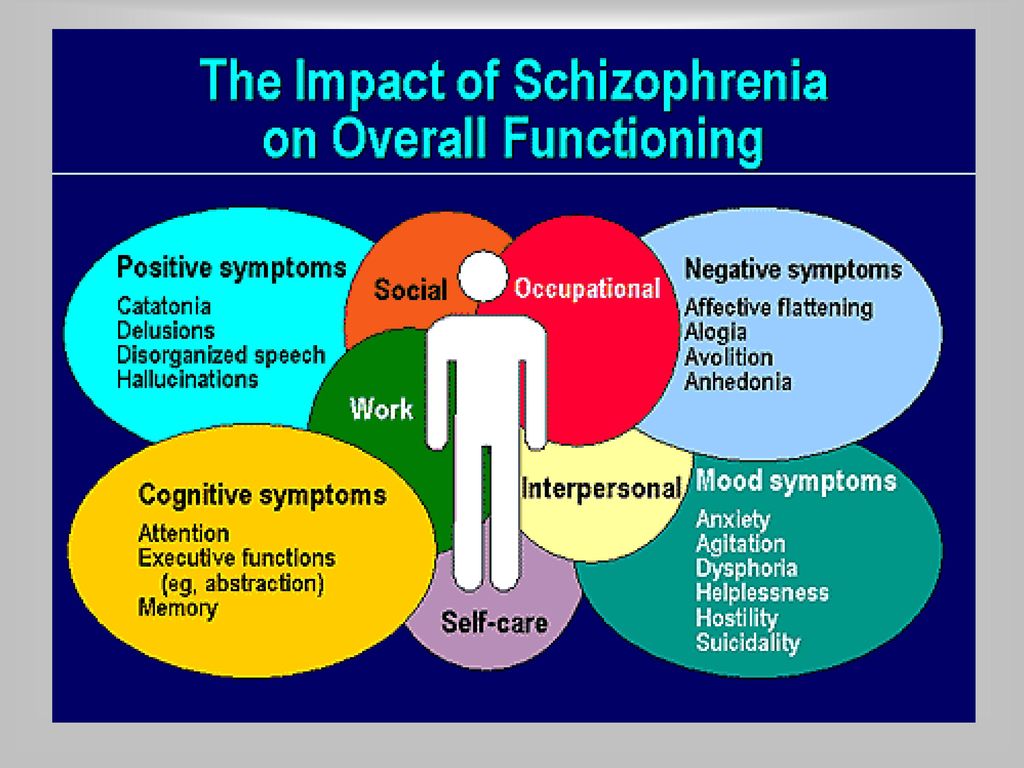

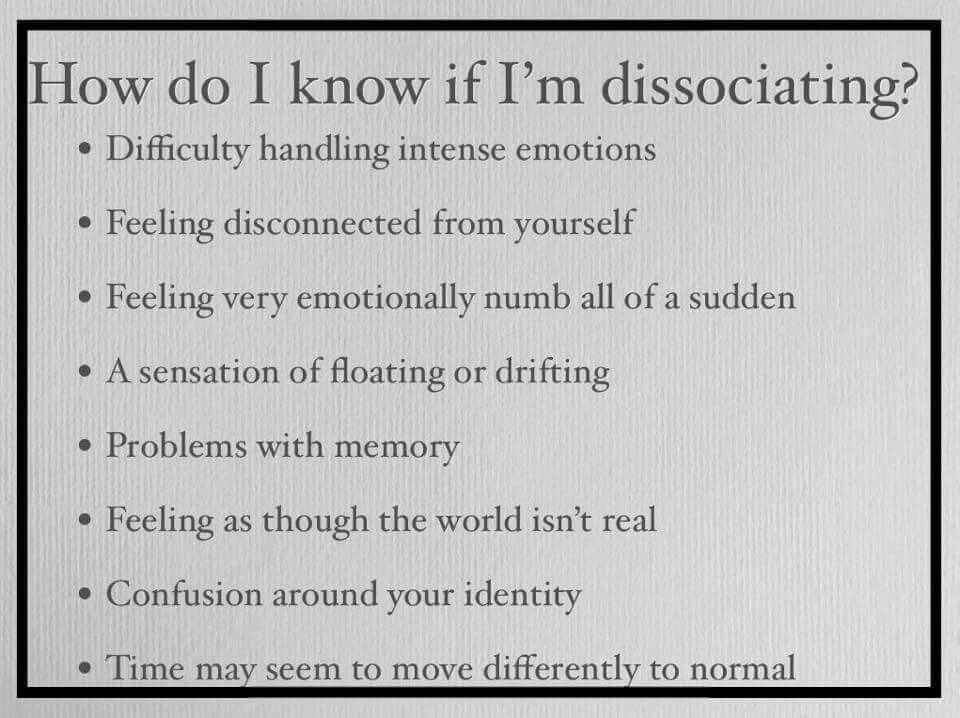

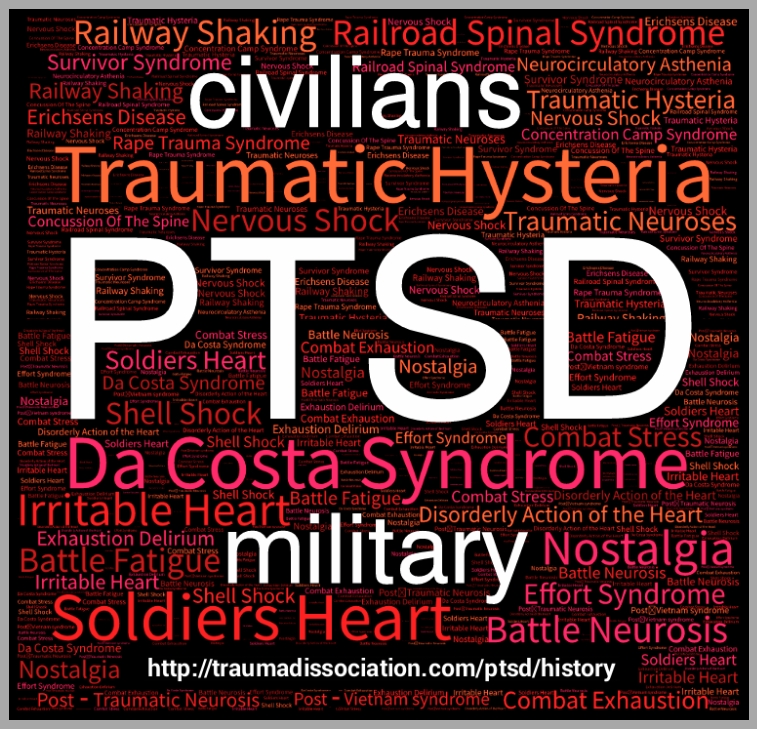

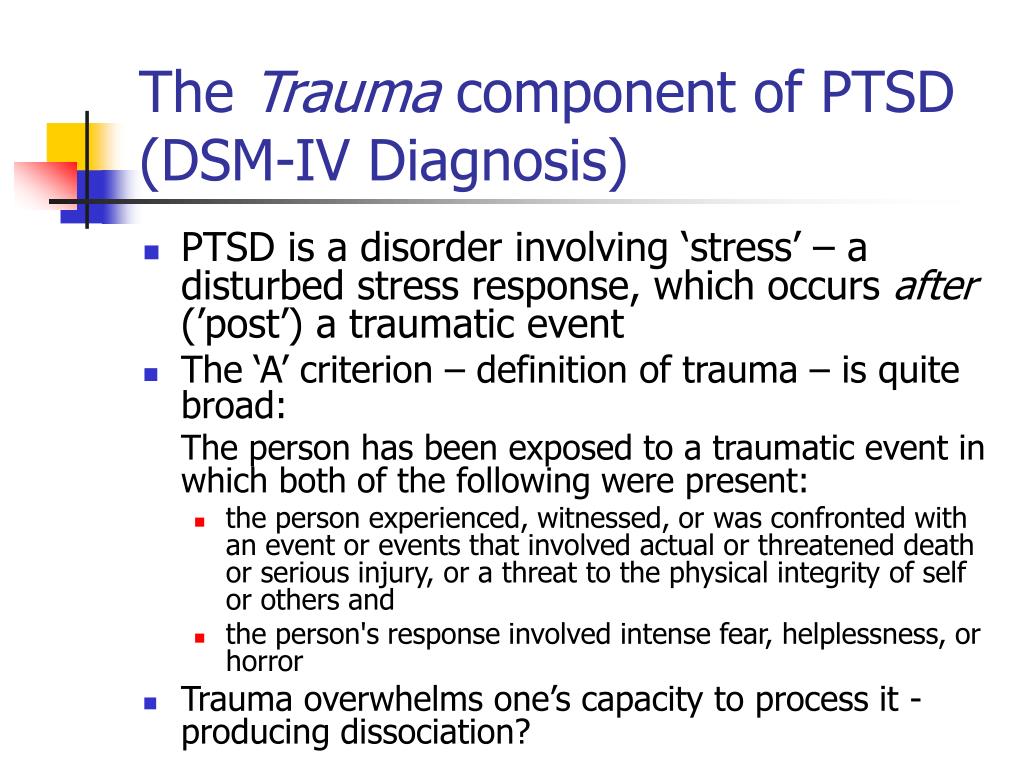

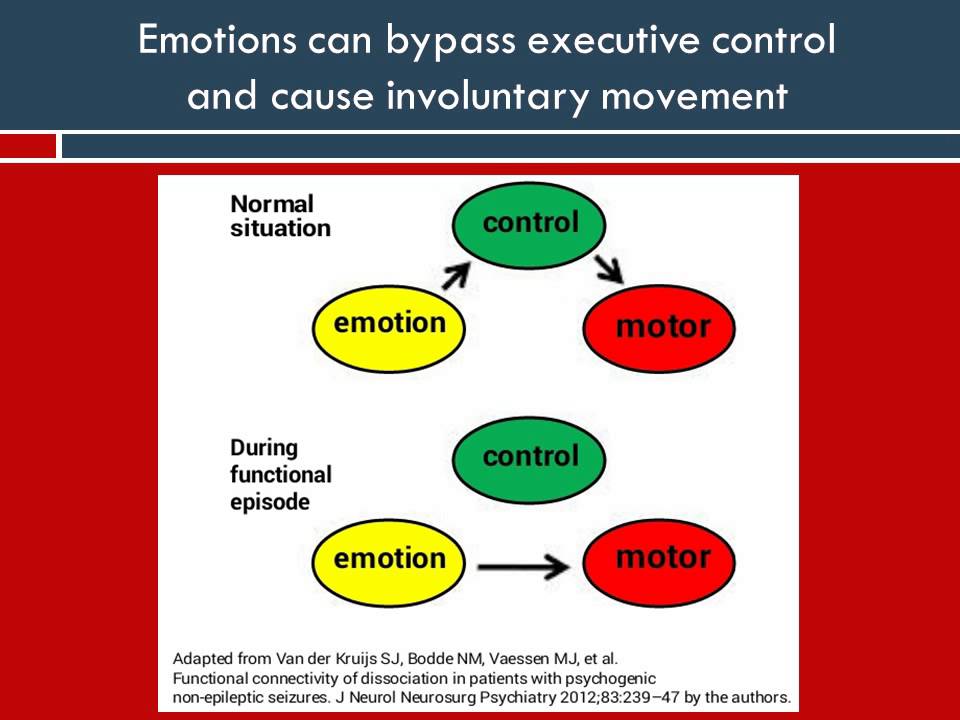

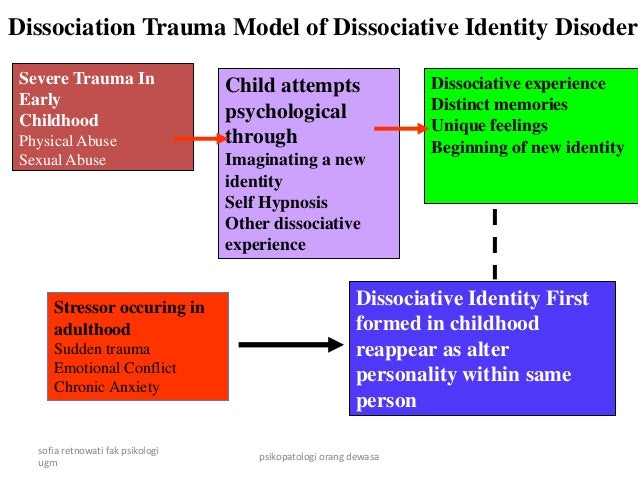

Dissociation is a word that is used for many different symptoms, and at times, it is understood differently by various professionals. It is a concept based on years of careful observations and study, including historical research into the original 19th-century literature on the subject.

It is a concept based on years of careful observations and study, including historical research into the original 19th-century literature on the subject.

#6

The opposite of dissociation is integration. Integration is the process of combining different aspects of personality into a unified whole that functions in a cohesive manner. It is the result of the development of a stable sense of who we are.

#7

We develop a sense of self over the course of our development, which is made up of our life experiences and our perception of who we are. We can then place these experiences in our life history as an integral part of our autobiography.

#8

The integrative capacity of children is much more limited than that of adults, and it is still developing. Thus, they are not able to integrate their experiences into a coherent and whole life narrative.

#9

The parts of the personality that are divided and respond differently are called dissociative parts of the personality. They can range from extremely limited to more elaborate in function. The functions of each part may vary from person to person.

They can range from extremely limited to more elaborate in function. The functions of each part may vary from person to person.

#10

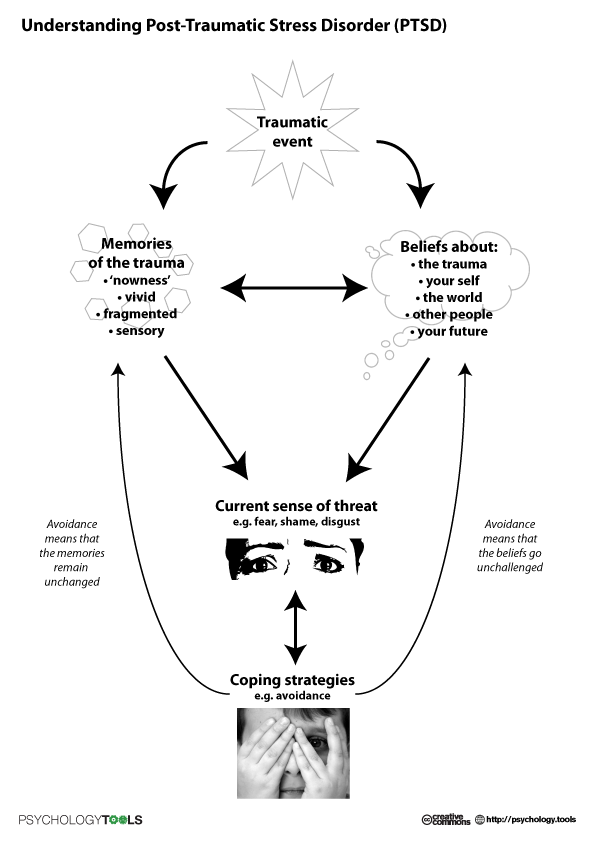

Dissociation develops when a person is too overwhelmed by an experience to be able to integrate it fully. It is a survival strategy that allows a person to go on with normal life by avoiding extremely stressful experiences.

#11

There are two classifications of diagnoses for people who have chronic dissociative disorders: the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, which is currently in its fourth edition, and the International Classification of Diseases, which is published by the World Health Organization.

#12

When you are in therapy, discuss your diagnosis with your therapist. Remember, diagnoses are not labels that make a statement about who you are. They are just ways to categorize broad experiences so that your therapist can help you.

#13

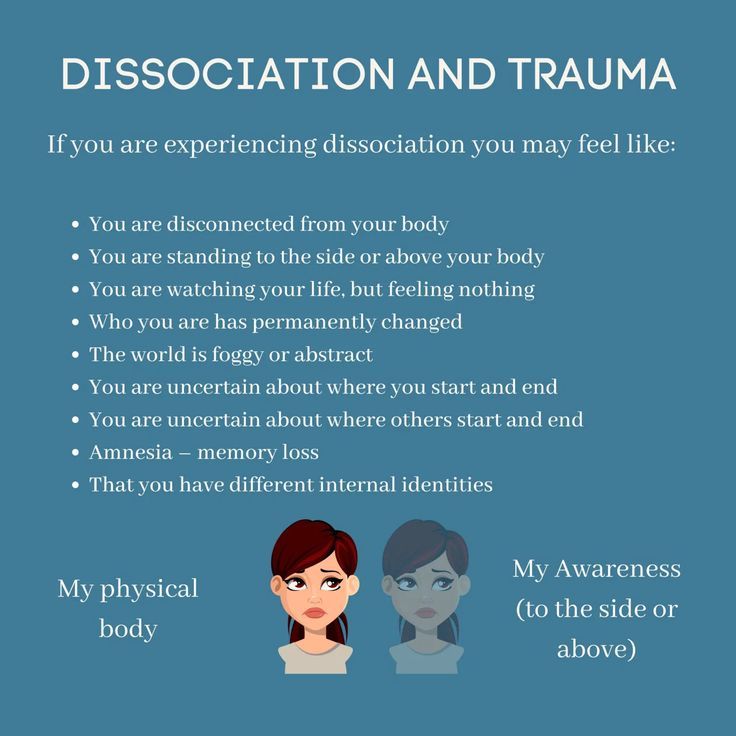

The following is a list of symptoms of dissociation, along with their associated changes in awareness.

#14

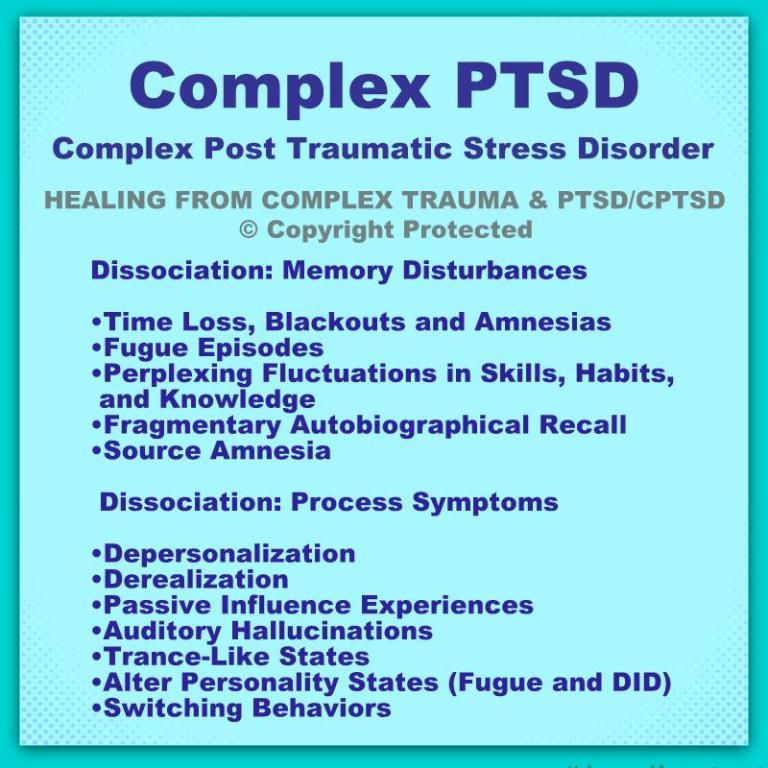

Dissociation involves a wide range of symptoms, from mild to severe, from temporary to chronic. For those with dissociative disorders, symptoms are generally chronic and interfere with daily life.

#15

The majority of people with a dissociative disorder do not have complaints about their identity or sense of self. They may experience strange and frightening symptoms that do not make sense, and which often lead them to fear they are crazy.

#16

The loss of certain functions or experiences that, in principle, you should be able to own is a common symptom of dissociation. For example, you may have amnesia, the loss of memory for important events or segments of your life. Or you may suddenly seem to lose a skill or knowledge that is a natural part of your life.

#17

Amnesia is the inability to recall events in your life. It can be caused by a dissociative disorder, and it typically involves serious memory problems. People may not only have amnesia for the past, but also for the present.

#18

When you feel estranged from yourself, it is often because your dissociative parts are overwhelmed or detached from your main personality. You may feel as if you do not exist or have any control over your actions.

#19

alienation from yourself and from your surroundings may occur. The world may feel unreal, like you are in a dream or a play, and people’s voices may sound very far away.

#20

Dissociative intrusions are when one dissociative part intrudes into the experience of another. They may occur in any arena of experience: memories, thoughts, feelings, perceptions, ideas, wishes, needs, movements, or behaviors.

#21

Dissociation is strongly associated with other changes in awareness that are common in everyone and are

Enjoying the preview?

Page 1 of 1

Comprehensive PTSD: a guide to recovery from childhood trauma

File loading please wait...

Citation preview

COMPLEX PTSD: a guide to recovery from childhood trauma 9001

COMPLEX SURVING guide2 and COMPLEX SURVING SUPTSD: map for recovering from childhood trauma

Pete Walker

COMPLEX PTSD: A guide to recovering from childhood trauma

Pete Walker

Ki'iv Computer vision "DIALEKTIKA" 2020

UDC blb. 895 Ub2 Translated from English by T.A. Issm a and l Edited by O.S. Moore in and Tskoy, with the participation of Ph.D. psychol. Sciences E. V. Krainkova

895 Ub2 Translated from English by T.A. Issm a and l Edited by O.S. Moore in and Tskoy, with the participation of Ph.D. psychol. Sciences E. V. Krainkova

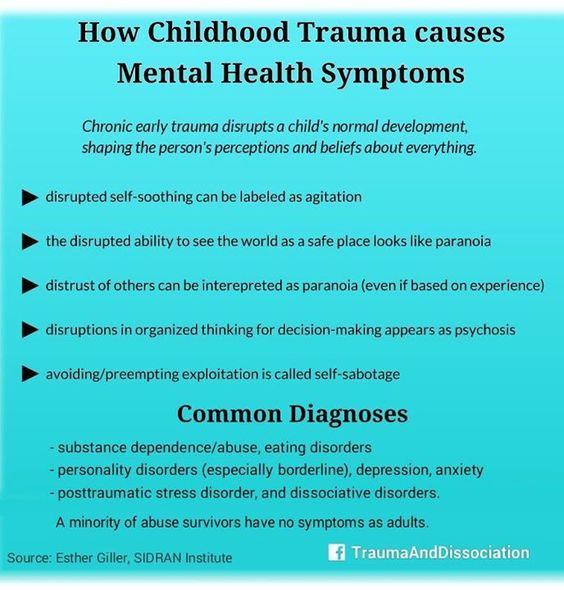

Walker , P . Complex PTSD: a guide to recovery from childhood trauma62/Pete Walker; per. from English. T . AND . Issmail - Kiev. : "Dialectics", 2020. - 2 74 p. : ill. - Paral. tit. English ISBN 978-b 1 7-7874-20-O (ukr.) ISBN 978-1 49287 1842 (eng.) in children of all ages, if the parents do not show enough love and patience, are too demanding, too busy with themselves, use corporal punishment, humiliate children verbally, physically or psychologically, or resort to all sorts of violence. The author offers his method of healing based on the methods of cognitive-behavioral therapy. The book is intended for practicing psychotherapists and their clients with k-PTSD. nine0012

UDCblb.895

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced for any purpose in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording on magnetic media, unless written permission is given by CreateSpace Independent. Pu\shing Platform. Copyright

Pu\shing Platform. Copyright

© 2020 Buy Dialektika Computer Pu\ishing Ltd.

Authorized trans\ation from the English language edition of Complex PTSD: From Surviving

to Thriving: A Guide and Mar for Recovering from Childhood Trauma (ISBN 978- 1 49287 1 842), publ\ished bу CreateSpace Independent Publ\ishing Platform

© 20 1 4 bу Pete Walker

All rights reserved. No part of this pu\ication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or bu any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 1 0 7 or 1 08 of the 1 976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the pu\isher. nine0012

ISBN 978-6 1 7-7874-20-0 (ukr.) ISBN 978- 1 49287 1 842 (eng.)

CHAPTER Dedication

13

Thanks

14

Thanks from the publisher D i alectika

14

V azhno 12 !14

Introduction

15

From the Publisher

18

Part 1: Recovery Path Overview

19

Chap ter 1. The path to recovery from PTS R

The path to recovery from PTS R

20

Chap ter 2. Levels of rehabilitation

35

9001 Improving relations57

Chapter 4 Progress in rehabilitation

71

didn't beat?

86

Chapter 6. What type of injury do I have?

99

Chapter

7.

Rehabilitation of the main addiction in com bined with addiction

1 19

Chap ter 8. Managing emotional regressions

131

Chapter 9. How to reduce the effect of the inner critic

1 49

Chapter 1 tica

1 67

ch apter 11: mourning

1 85

ch apter 12: coping with abandonment depression

207

Ch ap ter 13. Healing abandonment through relationships

22 1

Ch ap 14. Forgiveness: start with yourself

24

249

Chapter 16: Self Help Tools

253

Bibliography 2 19010 9020

CONTENTS Dedication

13

Acknowledgments

14

Thanks from the publisher

Read online “Ghosts of the past.

Structural Dissociation and Therapy of the Consequences of Chronic Traumatization, Onno Van der Hart, Ellert R. S. Nijenhuis, Kathy Steele

Structural Dissociation and Therapy of the Consequences of Chronic Traumatization, Onno Van der Hart, Ellert R. S. Nijenhuis, Kathy Steele The Haunted Self

Structural Dissociation and the Treatment of Chronic Traumatization

9001 This1 edition by arrangement with W. W. Norton & Company LtdScientific Revision V. A. Agarkov

© Onno Van der Hart, Ellert R. S. Nijenhuis, Kathy Steele, 2006

© Cogito Center, 2013

Preface

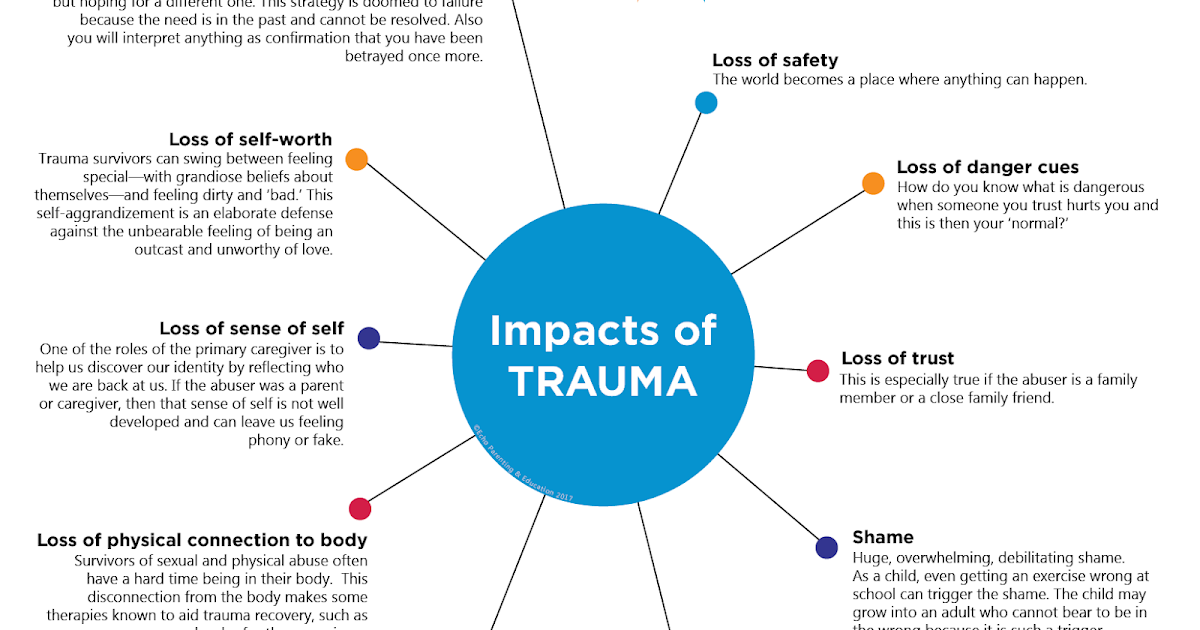

tests. The tasks of diagnosis and subsequent treatment of these patients are greatly complicated by the fact that they suffer from numerous symptoms associated with a wide variety of comorbid disorders. Many patients experience severe difficulties in daily life due to intrapsychic conflicts and maladaptive coping strategies. The main reason for their suffering is the painful experience of past traumatic experiences that haunts them in everyday life. Therefore, even when such a patient tries to hide his suffering behind a facade of apparent well-being, which is a fairly common strategy, his traumatic experience is always present in the space of the therapeutic relationship, drawing the therapist into circles of experience of despair and pain. Not surprisingly, patients with a history of chronic trauma often change therapists while gaining next to nothing from the therapy. As a rule, such patients are considered extremely difficult for therapy or resistant to it. nine0012

Not surprisingly, patients with a history of chronic trauma often change therapists while gaining next to nothing from the therapy. As a rule, such patients are considered extremely difficult for therapy or resistant to it. nine0012

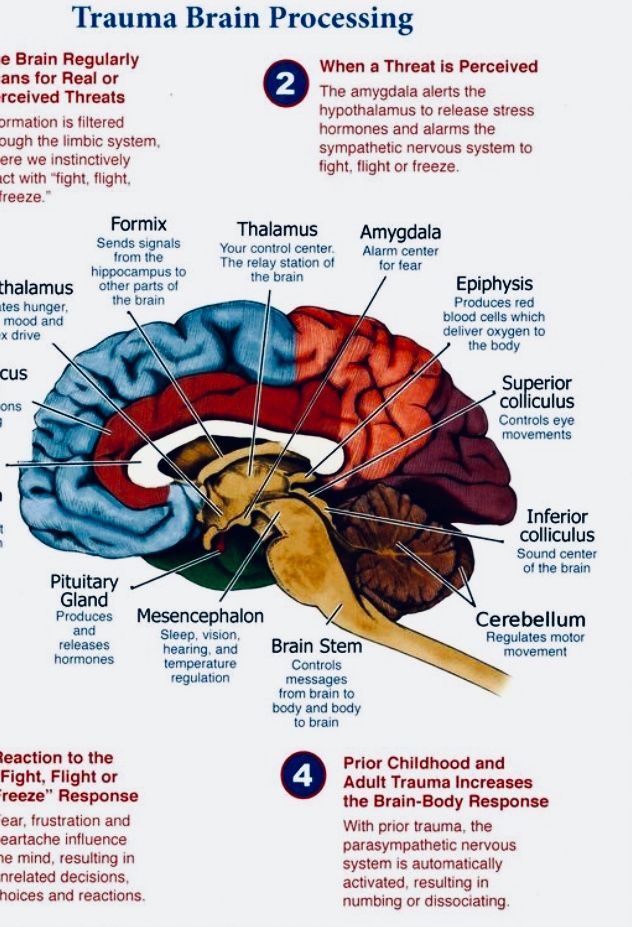

In this book, we would like to share what we have learned and learned from almost 65 years of combined experience of collective efforts in the field of treatment and case studies of patients suffering from the consequences of trauma. We have always listened carefully to our patients in order to understand the complex and unusual world of their experiences, the task of expressing which with the help of words was very difficult and frightening for them. We drew on practical experience, empirical research and theoretical reflection, as well as on the extensive literature on psychic trauma of the 19th and early 20th centuries and more recently. A wide variety of concepts drawn from a variety of theoretical approaches—learning theory, systems approach, cognitive psychology, emotion and attachment theories, psychodynamic perspective, and object relations theory—proved to be very helpful in our search. We have been greatly influenced by recent developments in evolutionary psychology and psychobiology, especially recent findings in the neuroanatomy and neurophysiology of emotion and the psychobiology of trauma. As a result of the processing of this entire array of data, our understanding of the essence of trauma has developed as a structural dissociation of personality.

We have been greatly influenced by recent developments in evolutionary psychology and psychobiology, especially recent findings in the neuroanatomy and neurophysiology of emotion and the psychobiology of trauma. As a result of the processing of this entire array of data, our understanding of the essence of trauma has developed as a structural dissociation of personality.

In our concept, we proceed from the definition of the term "dissociation", as it was formulated by Pierre Janet (1859-1947), a French philosopher, psychiatrist, psychologist, who is recognized as "one of the most prolific practitioners and theorists in the field of psychiatry over the past two century” (Nemiah, 1989, p. 1527). His work is fundamental to the theory and treatment of trauma-related psychiatric disorders. Structural dissociation is a change in the organization of an individual's personality that occurs after experiencing a psychic trauma. Structural dissociation, first of all, is characterized by excessive rigidity and isolation of the psychobiological systems of the personality in relation to each other, which leads to a lack of internal coherence and consistency in the personality of the affected individual. nine0012

nine0012

The introduction of the term structural dissociation ( personality ) is dictated by the current situation in the field of dissociation research. We have to admit that at present the concept of dissociation as such has lost its clarity and has become quite problematic. Thus, we can find in the literature many completely different and often contradictory definitions of dissociation. The term "dissociation" is used both to refer to individual symptoms and to describe conscious or unconscious mental activity or "process", as well as the name of one of the protective "mechanisms" of the psyche, and the list can be continued. The range of symptoms considered dissociative has become so wide that this clinical category has lost its specificity. In addition to the symptoms of structural dissociation of the personality, the range of dissociative phenomena includes states of altered consciousness, varying in a wide range from normal to pathological. As will be shown later in this book, from our point of view, such an expansion of the conceptual field greatly distorts the meaning of the concept. nine0012

nine0012

Our book presents an attempt to synthesize the theory of structural dissociation and Janet's psychology of action. The psychology of action, originating in the pioneering work of Janet, explores the nature of adaptive and therefore integrative action, the mastery of which is essential for anyone who wishes to fulfill their potential and live life to the fullest. Adaptive integrative action is needed both by patients in their efforts to resolve the post-traumatic problem, and by therapists who help patients cope with the consequences of psychic trauma. The psychology of action has a universal application. We will consider the personality organization of a person who has experienced trauma, as well as the reasons why his or her mental and behavioral acts become maladaptive. Janet's theory of structural dissociation and the psychology of action presented in this book provide a detailed answer to the question of what kind of integrative action on the part of the traumatized individual is necessary in order for the haunting past to recede and significant changes for the better occur in life. nine0012

nine0012

The book is addressed primarily to clinicians, but it will also be of interest to students studying clinical psychology and psychiatry, as well as researchers. Therapists working with adults who have experienced chronic childhood trauma of abuse or neglect will find useful insights and techniques in it that can make therapy more effective and effective, as well as more tolerable for the person suffering. They, like us once, may rediscover the good old truth that there is nothing more practical than a good theory. We believe that the theory and therapeutic approach presented in the book will also be useful for colleagues working with refugees, victims of torture, war veterans, as well as with adults who have experienced a single traumatic event, such as sexual violence, a terrorist attack, a traffic accident. or natural disaster. nine0012

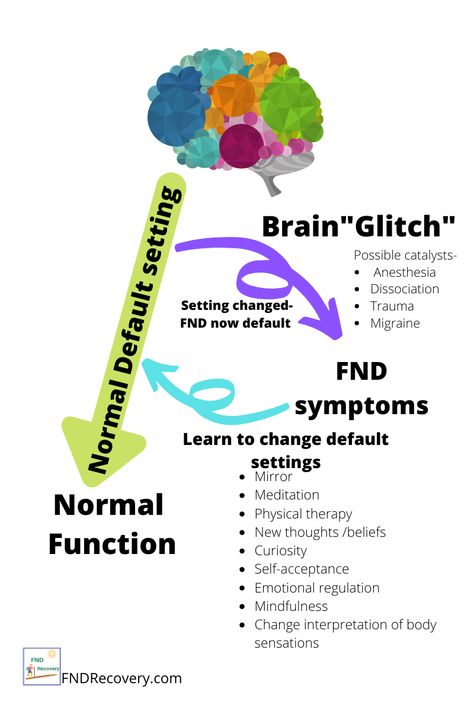

The book will help students of clinical psychology and psychiatry to better navigate the diagnosis, treatment and research work in the field of the consequences of psychic trauma. Researchers will be able to discover the heuristic nature of the theory of structural dissociation as the source of many scientific hypotheses. For example, our theory offers a description of how changes occur in the mental functioning and behavior of a severely traumatized individual when executive control is transferred from one part of the dissociated personality to another, a fact often overlooked by many traumatic stress researchers. nine0012

Researchers will be able to discover the heuristic nature of the theory of structural dissociation as the source of many scientific hypotheses. For example, our theory offers a description of how changes occur in the mental functioning and behavior of a severely traumatized individual when executive control is transferred from one part of the dissociated personality to another, a fact often overlooked by many traumatic stress researchers. nine0012

Relatively short-term therapies such as cognitive behavioral therapy and eye movement-assisted desensitization and processing (EMDR; Foa, Keane & Friedman, 2000; Foa & Rothbaum, 1998; Follette, Ruzek & Abueg, 1998; Leeds, 2009; Resick & Schnicke, 1993; Shapiro, 2001). However, no studies have yet been conducted that would confirm the effectiveness of these approaches in the treatment of patients with chronic trauma outside of phase-oriented therapy, the model of which is presented in this book. The severe comorbid psychopathology inherent in these patients is the main reason for their exclusion from studies of the effectiveness of therapy for PTSD (Spinazzola, Blaustein & Van der Kolk, 2005). In addition, single traumatic events in adulthood often resurrect past unprocessed traumatic experiences. Some people with chronic childhood trauma manage to cope with the consequences of experiencing a single traumatic experience in adulthood, despite the impaired ability to integrate. However, this comes at the cost of great effort, and the balance achieved is often fragile: once the demands of life exceed the possibilities of integration, the person may develop all the symptoms of a trauma-related disorder. For such patients, a short-term therapy format based on direct confrontation interventions with traumatic experiences is unlikely to be appropriate. Patients with a history of cumulative trauma usually require more complex work in long-term therapy. Our book is devoted to just such an approach to the treatment of the consequences of trauma. nine0012

In addition, single traumatic events in adulthood often resurrect past unprocessed traumatic experiences. Some people with chronic childhood trauma manage to cope with the consequences of experiencing a single traumatic experience in adulthood, despite the impaired ability to integrate. However, this comes at the cost of great effort, and the balance achieved is often fragile: once the demands of life exceed the possibilities of integration, the person may develop all the symptoms of a trauma-related disorder. For such patients, a short-term therapy format based on direct confrontation interventions with traumatic experiences is unlikely to be appropriate. Patients with a history of cumulative trauma usually require more complex work in long-term therapy. Our book is devoted to just such an approach to the treatment of the consequences of trauma. nine0012

Based on Janet's theory of structural dissociation and action psychology, we developed a phase-oriented treatment model that focuses on identifying and treating structural dissociation and associated maladaptive mental and behavioral activities. The main principle of this approach is to help patients master more effective mental and behavioral actions that would allow them to overcome structural dissociation and change their lives for the better. Our approach is aimed at solving the main therapeutic problem, which can be formulated as follows: increasing the ability to integrate (or, according to our theory, mental level of patients), first of all, in order to improve the patient's adaptive capabilities in his daily functioning, which creates conditions for the second step, namely the processing of the patient's non-integrated traumatic experience, the completion of "unfinished business", mainly for traumatic memories.

The main principle of this approach is to help patients master more effective mental and behavioral actions that would allow them to overcome structural dissociation and change their lives for the better. Our approach is aimed at solving the main therapeutic problem, which can be formulated as follows: increasing the ability to integrate (or, according to our theory, mental level of patients), first of all, in order to improve the patient's adaptive capabilities in his daily functioning, which creates conditions for the second step, namely the processing of the patient's non-integrated traumatic experience, the completion of "unfinished business", mainly for traumatic memories.

The introductory chapter provides a brief overview of the concept of dissociation, ideas about phase-oriented therapy, and the basic concepts of Janet's action psychology, which are discussed in more detail below. The first five chapters of the first part are devoted to a clinical description of the different levels of structural dissociation and an introduction to the theory of structural dissociation. The first chapter describes the basic form of structural dissociation (or primary dissociation), in which the personality of an individual who has experienced psychological trauma is divided into the main dissociative part, associated with activity in everyday life and avoiding traumatic memories, and another part that has a less complex organization and is focused on to protect against the threat. This chapter also discusses the differences between autobiographical narrative and traumatic memories. The second chapter presents a detailed analysis of the differences between the two types of dissociative personality parts described in the previous chapter. The third chapter discusses the secondary structural dissociation of the personality, in which one part of the personality is focused on everyday life, and two or more parts are focused on protection from threat. This level of structural dissociation is characteristic of patients with chronic trauma experiences and complex trauma-related psychiatric disorders.

The first chapter describes the basic form of structural dissociation (or primary dissociation), in which the personality of an individual who has experienced psychological trauma is divided into the main dissociative part, associated with activity in everyday life and avoiding traumatic memories, and another part that has a less complex organization and is focused on to protect against the threat. This chapter also discusses the differences between autobiographical narrative and traumatic memories. The second chapter presents a detailed analysis of the differences between the two types of dissociative personality parts described in the previous chapter. The third chapter discusses the secondary structural dissociation of the personality, in which one part of the personality is focused on everyday life, and two or more parts are focused on protection from threat. This level of structural dissociation is characteristic of patients with chronic trauma experiences and complex trauma-related psychiatric disorders. The fourth chapter contains a characterization of the tertiary structural dissociation that occurs in patients with two or more dissociative parts involved in daily activities and several other parts of the personality focused on defense against threat. We believe that tertiary structural dissociation is unique to patients with dissociated identity disorder. In the fifth chapter we try to bring some clarity to what symptoms can be recognized as dissociative. The sixth chapter provides an analysis of how the theory of structural dissociation can be applied to explain the various traumatic disorders described in both DSM-IV (APA, 1994) and ICD-10 (WHO, 1992), as well as for understanding the comorbid disorders so common in victims of chronic trauma.

The fourth chapter contains a characterization of the tertiary structural dissociation that occurs in patients with two or more dissociative parts involved in daily activities and several other parts of the personality focused on defense against threat. We believe that tertiary structural dissociation is unique to patients with dissociated identity disorder. In the fifth chapter we try to bring some clarity to what symptoms can be recognized as dissociative. The sixth chapter provides an analysis of how the theory of structural dissociation can be applied to explain the various traumatic disorders described in both DSM-IV (APA, 1994) and ICD-10 (WHO, 1992), as well as for understanding the comorbid disorders so common in victims of chronic trauma.

The second part deals with Janet's psychology of action and its application to the concept of structural dissociation. Here we analyze the external manifestations of mental and behavioral actions of a maladaptive nature or the absence of the necessary adaptive actions in patients with experience of chronic traumatization. Our therapeutic approach is aimed at helping the patient to abandon the maladaptive actions that manifest themselves in the symptoms of a psychiatric disorder and support structural dissociation, and mastering new adaptive actions. Here we discuss possible adaptive and integrative actions. The seventh chapter describes the role of special mental and behavioral actions necessary to achieve and maintain the integration of the individual, as well as for better adaptation to everyday life. The central theme of this chapter is synthesis as the basis of integration. The eighth chapter is devoted to awareness, or, in Janet's words, implementation [1] , whose constituent elements are personification and presentation. The implementation of is a higher and more complex level of integration and requires a higher level of mental functioning. It also describes the difficulties that victims of mental trauma face when perceiving the present. For example, the actions of people after a traumatic experience indicate that they have a disturbed idea of the boundary between the experience of the events of the present and the experience of a traumatic situation that has remained in the past.

Our therapeutic approach is aimed at helping the patient to abandon the maladaptive actions that manifest themselves in the symptoms of a psychiatric disorder and support structural dissociation, and mastering new adaptive actions. Here we discuss possible adaptive and integrative actions. The seventh chapter describes the role of special mental and behavioral actions necessary to achieve and maintain the integration of the individual, as well as for better adaptation to everyday life. The central theme of this chapter is synthesis as the basis of integration. The eighth chapter is devoted to awareness, or, in Janet's words, implementation [1] , whose constituent elements are personification and presentation. The implementation of is a higher and more complex level of integration and requires a higher level of mental functioning. It also describes the difficulties that victims of mental trauma face when perceiving the present. For example, the actions of people after a traumatic experience indicate that they have a disturbed idea of the boundary between the experience of the events of the present and the experience of a traumatic situation that has remained in the past. So, for example, they are characterized by the expectation that the future will inevitably be fraught with a repetition of the catastrophe experienced once: the traumatic experience has not acquired the quality of the past, it seems to continue in the present and in the future. Such distortions in the perception of reality are a consequence of the low level of mental functioning of traumatized individuals in situations where they are forced to solve life problems and, accordingly, lead to serious difficulties and disruptions in adaptation. Solving the problems of everyday life requires the individual to perform a wide variety of activities organized in a hierarchical structure, so that the most complex activities are located at the highest levels in this hierarchy. High-level actions pose a particular problem for individuals who have experienced psychic trauma. The ninth chapter describes this hierarchical model. The notion of such a hierarchical organization is useful for the systematic assessment of the current level of adaptive functioning in terms of mental and behavioral actions.

So, for example, they are characterized by the expectation that the future will inevitably be fraught with a repetition of the catastrophe experienced once: the traumatic experience has not acquired the quality of the past, it seems to continue in the present and in the future. Such distortions in the perception of reality are a consequence of the low level of mental functioning of traumatized individuals in situations where they are forced to solve life problems and, accordingly, lead to serious difficulties and disruptions in adaptation. Solving the problems of everyday life requires the individual to perform a wide variety of activities organized in a hierarchical structure, so that the most complex activities are located at the highest levels in this hierarchy. High-level actions pose a particular problem for individuals who have experienced psychic trauma. The ninth chapter describes this hierarchical model. The notion of such a hierarchical organization is useful for the systematic assessment of the current level of adaptive functioning in terms of mental and behavioral actions. The same chapter discusses both the maladaptive actions patients take when their level of functioning does not allow them to take actions that lead to adaptation, and those actions that are necessary for positive change. The tenth chapter contains an overview of the various phobias that are common to people who have experienced chronic trauma and that contribute to the maintenance of structural dissociation. This chapter also focuses on the principles of learning involved in the mechanisms for maintaining structural dissociation. nine0012

The same chapter discusses both the maladaptive actions patients take when their level of functioning does not allow them to take actions that lead to adaptation, and those actions that are necessary for positive change. The tenth chapter contains an overview of the various phobias that are common to people who have experienced chronic trauma and that contribute to the maintenance of structural dissociation. This chapter also focuses on the principles of learning involved in the mechanisms for maintaining structural dissociation. nine0012

The third part is devoted to a systematic description of how the theory of structural dissociation and the psychology of action can find application in the diagnosis of the functioning of the patient (chapter 11) and in phase-oriented treatment (subsequent chapters). The twelfth chapter discusses the general principles of therapy for the consequences of psychic trauma. The main goal of the therapist's actions is to increase the level of mental functioning of the patient, improve his psychological and communication skills. The following chapters discuss the objectives of each of the three phases of therapy, with a lot of focus on dealing with specific phobias that support structural dissociation and hinder adaptive functioning. In chapter thirteen, the first of two chapters dealing with the challenges of the initial phase of therapy, we will focus on overcoming the fear of establishing and losing attachment in a relationship with a therapist. This chapter is devoted to the problem of the therapeutic relationship with a patient who both avoids attachment and seeks it. The fourteenth chapter deals with overcoming the phobia of mental actions associated with trauma (thoughts, feelings, memories, desires, etc.), and the fifteenth chapter continues this topic with regard to the phobia of dissociative parts. The sixteenth chapter describes the second phase of therapy, the focus of which is the phobia of traumatic memories. The seventeenth chapter is devoted to the third phase of treatment - overcoming the fears that accompany the return to normal life.

The following chapters discuss the objectives of each of the three phases of therapy, with a lot of focus on dealing with specific phobias that support structural dissociation and hinder adaptive functioning. In chapter thirteen, the first of two chapters dealing with the challenges of the initial phase of therapy, we will focus on overcoming the fear of establishing and losing attachment in a relationship with a therapist. This chapter is devoted to the problem of the therapeutic relationship with a patient who both avoids attachment and seeks it. The fourteenth chapter deals with overcoming the phobia of mental actions associated with trauma (thoughts, feelings, memories, desires, etc.), and the fifteenth chapter continues this topic with regard to the phobia of dissociative parts. The sixteenth chapter describes the second phase of therapy, the focus of which is the phobia of traumatic memories. The seventeenth chapter is devoted to the third phase of treatment - overcoming the fears that accompany the return to normal life. The book ends with an epilogue. nine0012

The book ends with an epilogue. nine0012

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all those who directly or indirectly contributed to the development of the ideas presented in the book, as well as to its writing. We gratefully acknowledge the enormous influence of our predecessor teachers, most notably Pierre Janet and Charles S. Myers, as well as our immediate mentors, who have taught us for over thirty years what has proven invaluable in clinical practice with chronically traumatized patients to understand them. state, as well as in our research work. Among them are Bennett Brown, Catherine Fine, Erica Fromm, Richard P. Kluft, Richard Loewenstein, Stephen Porges, Frank W. Putnam, Colin M. Ross, Roberta Zachs, David Spiegel, and Bessel A. Van der Kolk. We are extremely indebted to Martin Dorai, Pat Ogden, and Yvonne Teuber for participating in the discussion of many of the points presented in the book, as well as for their help with various chapters. Pat Ogden deserves special thanks for her tireless ideological and emotional support throughout the entire project. nine0012

nine0012

Many thanks to Isabelle Sayot, President of the Pierre Janet Institute in Paris, for fruitful discussions on various aspects of Janet's theory. We are also grateful to many of our colleagues whose work has had a major impact on our professional thinking and practice and with whom we have had so many fruitful discussions. Among them are Jon Ellen, Peter Barach, Ruth Blizzard, Elizabeth Bowman, Stephen Brody, Chris Bruin, John Brier, Danny Brom, Dan Brown, Paul Brown, Richard Chefetz, James Chu, Marilyn Kloitr, Philip Kunz, Christine Courtois, Louis Kroc , Constance Dahlenberg, Eric de Soir, Paul Dell, Hans den Boer, Nel Dryer, Janina Fischer, Julian Ford, Elizabeth Howell, George Fraser, Ursula Gast, Marco van Herwen, Jean Goodwin, Arne Hoffman, Olaf Holom, Michaela Huber, Rolf Kleber, Sarah Krakauer, Ruth Lanyus, Anssi Leikola, Helga Mates, Francisco Orengo Garcia, Laurie Pearlman, John Raftery, Louise Raddemann, Colin Ross, Barbara Rofbaum, Paivi Saarinen, Vedat Sar, Allan Shor, Daniel Siegel, Ailey Somer, Ann Suokas-Cunliff, Marten Van Son, Johan Vanderlinden, Eric Vermetten, Eileiser Witztum, and many others whom we might not have mentioned by accident. nine0012

nine0012

We are especially indebted to our closest colleagues who support us day by day in our practice with unwavering benevolence. They work with us, share their experience and wisdom, support us emotionally in difficult moments. These are Suzette Bone (with whom one of us, Onno van der Hart, started his pioneering work in Holland), Barry Casemire, Sandra Hale, Steve Harris, Miles Hassler, Vera Mee-rop, Lisa Engert Morris, Janni Mölder, Cathy Toudson , Harry Vos and Marty Wakeland. nine0012

We would like to thank our publishers Deborah Malmud, Michael McGandy and Kristen Holt-Browning at Norton' e and series editor Daniel Siegel, who supervised this project, and Casey Rubble for her help in preparing the book.

And we are also very grateful to our patients, from whom we learned the most. We are grateful to them for the opportunity to be there throughout the difficult path of therapy, as well as for the invaluable, amazing lessons that they taught us. nine0012

Authors' preface to the Russian edition

The publication of the Russian edition of "Ghosts of the Past" was a special event for us, given the growing interest in understanding and treating psychic trauma in Russia. In the last century, Russia has experienced many upheavals, including the most severe consequences of long wars and repressions. Like specialists from other countries, Russian clinicians are increasingly aware of the importance of working with trauma in psychological and psychiatric practice. Not only war, repression, terrorist attacks, natural disasters and life-threatening incidents can lead to traumatic disorders such as PTSD or complex PTSD, but also sexual abuse, severe personal loss, domestic violence, torture, child abuse. Gradually comes the understanding of the close relationship of abuse and neglect in childhood, severe attachment disorders with the development of chronic traumatic disorders, characterized by a complex clinical picture, such as complex PTSD and dissociative disorders. nine0012

In the last century, Russia has experienced many upheavals, including the most severe consequences of long wars and repressions. Like specialists from other countries, Russian clinicians are increasingly aware of the importance of working with trauma in psychological and psychiatric practice. Not only war, repression, terrorist attacks, natural disasters and life-threatening incidents can lead to traumatic disorders such as PTSD or complex PTSD, but also sexual abuse, severe personal loss, domestic violence, torture, child abuse. Gradually comes the understanding of the close relationship of abuse and neglect in childhood, severe attachment disorders with the development of chronic traumatic disorders, characterized by a complex clinical picture, such as complex PTSD and dissociative disorders. nine0012

Finally, clinical experience with patients who have experienced psychic trauma confirms the special role of personality dissociation in chronic trauma, which, in fact, is the main theme of this book. The concept of structural dissociation allows for a deeper understanding of the theory, diagnosis and treatment of the consequences of chronic trauma.

The concept of structural dissociation allows for a deeper understanding of the theory, diagnosis and treatment of the consequences of chronic trauma.

This edition is a revised and revised version of the original English version of the book. We sincerely hope that our work will contribute to the study and successful treatment of patients with chronic trauma in Russia. In addition, we hope to further integrate the theory of structural dissociation with other trauma theories and psychological concepts. nine0012

The original English edition, as well as translations into other languages, received approval and aroused interest not only among specialists who found the book important and useful, but also among the people who experienced trauma. Some of them have written to us that reading the book not only helped them to sort out their experiences and find a way out of life's dead ends, but, more importantly, opened the way for them to change and heal from trauma-related suffering and disorders.