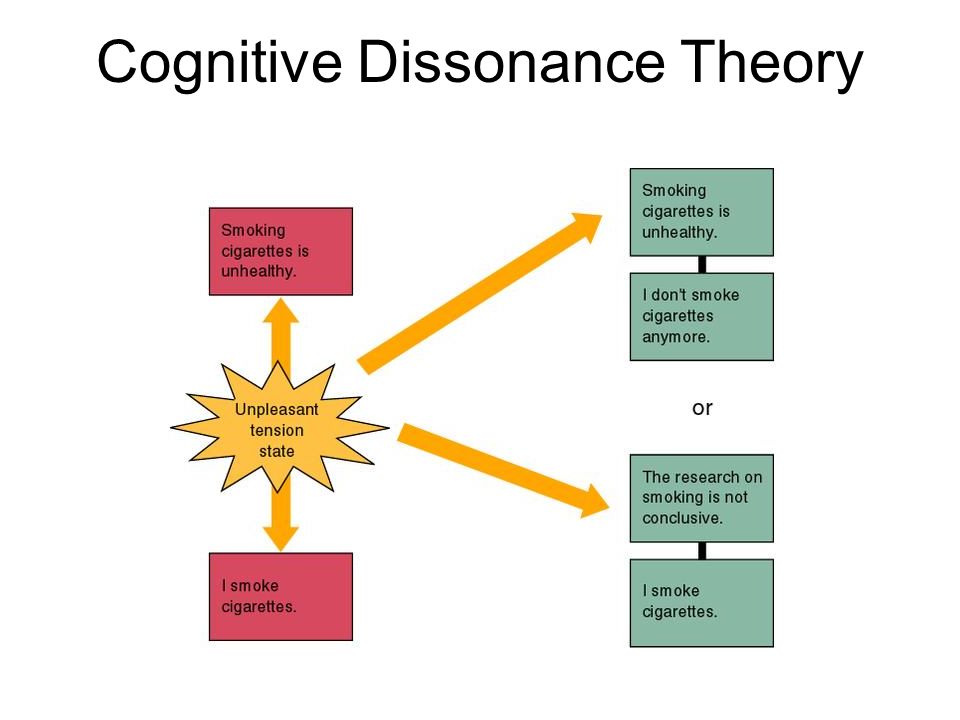

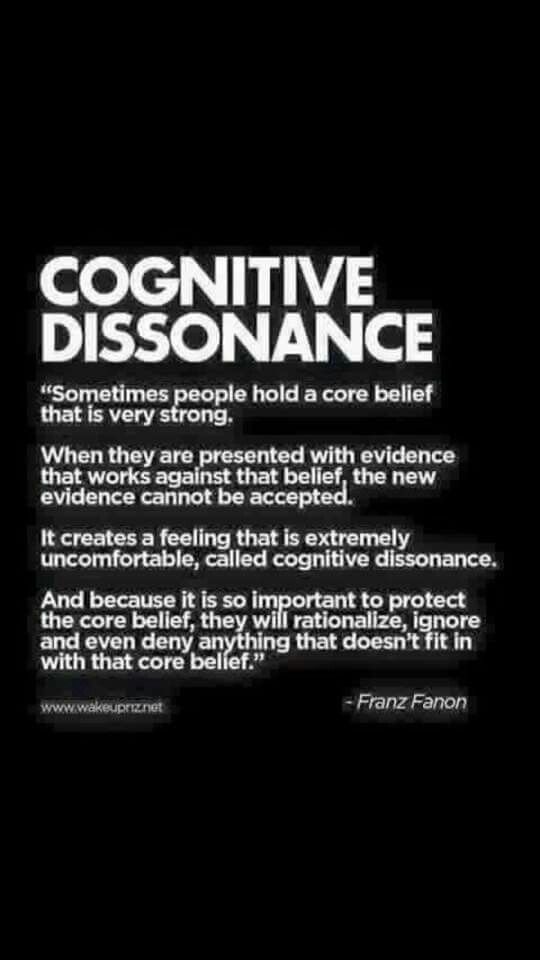

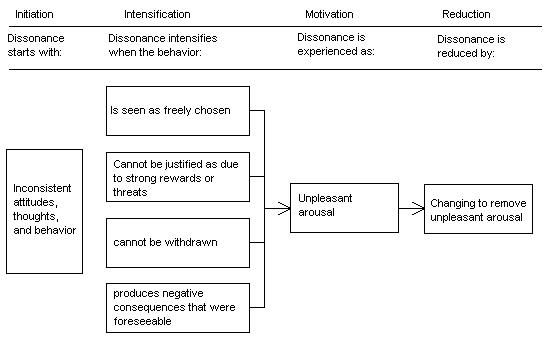

Cognitive dissonance results when

Cognitive Dissonance - The Decision Lab

Cognitive dissonance describes when we avoid having conflicting beliefs and attitudes because it makes us feel uncomfortable. The clash is usually dealt with by rejecting, debunking, or avoiding new information.

Where this bias occurs

Debias Your Organization

Most of us work & live in environments that aren’t optimized for solid decision-making. We work with organizations of all kinds to identify sources of cognitive bias & develop tailored solutions.

Learn about our work

Consider the following hypothetical situation: John is an avid environmentalist. He is president of the environmental club at school, goes to climate change marches, and John’s family owns an electric car.

One day, he decides to attend a lecture on the negative environmental effects of certain animal products which apparently contribute significantly to climate change. To his dismay, John realizes that he uses many of those products on a regular basis. His stomach drops:

That means that he is part of the problem he is trying to resolve.

This cannot be! John is a champion of the environment. But, John doesn't think he is willing to stop eating meat and he knows his family won’t be.

To get rid of the pit in his stomach and resolve the identity crisis he is having, John quickly concludes that the speaker must not know what they are talking about. Also, he thinks, even if animal products aren’t great for the environment, he has done so many other things that are good for the environment, that it must even out (at least). John’s mind is put at ease.

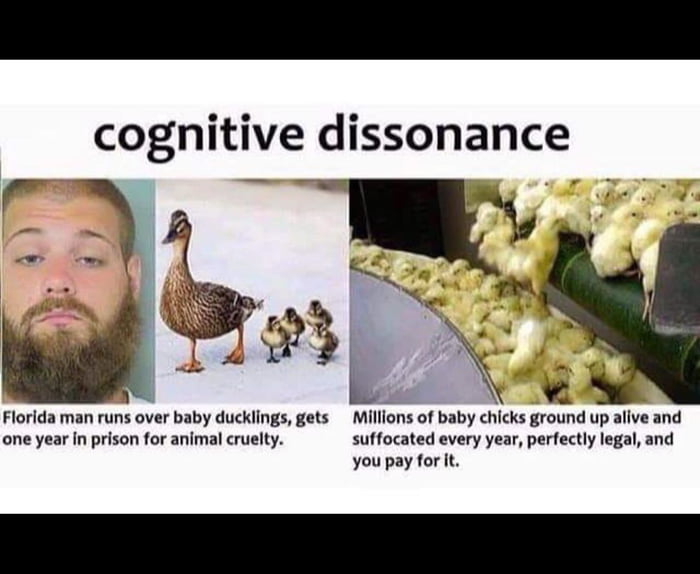

Cognitive dissonance is most likely at work here. To resolve the inconsistency revealed by this new information on certain animal products, John rejects and rationalizes the speech so that his identity as an environmentalist isn’t painfully compromised.

Debias Your Organization

Most of us work & live in environments that aren’t optimized for solid decision-making. We work with organizations of all kinds to identify sources of cognitive bias & develop tailored solutions.

We work with organizations of all kinds to identify sources of cognitive bias & develop tailored solutions.

Learn about our work

Individual effects

Rejecting, rationalizing, or avoiding information that conflicts with our beliefs can lead us to make poor decisions. This is because the information is not rejected because it is false but because it makes us uncomfortable. Information that is both true and useful can often have this effect. Decisions made in the absence of true and useful information can have harmful consequences. Smoking, for example, has been shown to cause cancer and contribute to various other chronic health conditions. Smokers often rationalize their detrimental decision to continue smoking by either denying evidence that supports its health risks or by considering themselves to be the lucky exception.

Systemic effects

Looking further into the effects of cognitive dissonance leads to troubling conclusions across academia and political society. If researchers tend to analyze information in a way that supports conclusions that are consistent with their own beliefs, then cognitive dissonance may threaten the objective methodology that underpins much of academia today.

If researchers tend to analyze information in a way that supports conclusions that are consistent with their own beliefs, then cognitive dissonance may threaten the objective methodology that underpins much of academia today.

The effectiveness of social causes is also threatened by cognitive dissonance. The change they often call for requires many people to change their existing beliefs and behavior. This is not possible if a significant portion of us do not consider evidence that conflicts with the beliefs or behaviors these causes seek to alter. Environmentalism and its associated climate change action movements are a good example. Most of us care for nature and want to preserve it. But the evidence championed by these movements often indicates that we aren’t doing enough as individuals. Many of us are part of the problem. Such evidence shows us that our behaviors are often at odds with our beliefs.

Seeing this contradiction, many of us respond by either rationalizing our behaviors, rejecting environmentalism and the evidence it relies on, or adopting the belief that our individual actions have a negligible effect on the environment. This prevents the widespread behavioral change many environmental causes call for.

This prevents the widespread behavioral change many environmental causes call for.

Cognitive dissonance may also facilitate a political divide. When we believe strongly in a political leader or ideology, we are more likely to dismiss information that does not support their message. In other words, we often ignore or distort evidence that challenges our political beliefs. This is part of the reason why it is so difficult to change someone’s mind on political issues. Voters are likely to remain loyal to their chosen candidates and party even when evidence that should challenge those loyalties is presented.1

“When people feel a strong connection to a political party, leader, ideology, or belief, they are more likely to let that allegiance do their thinking for them and distort or ignore the evidence that challenges those loyalties.”

– Social psychologists Elliot Aronson and Carol Tavris

Why it happens

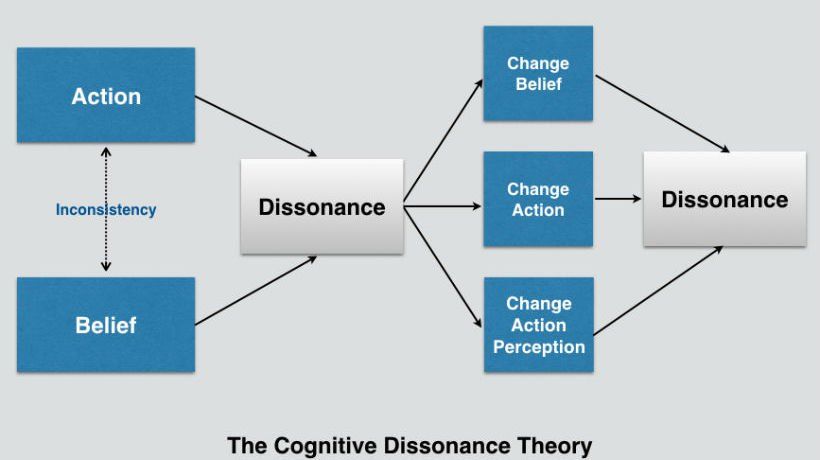

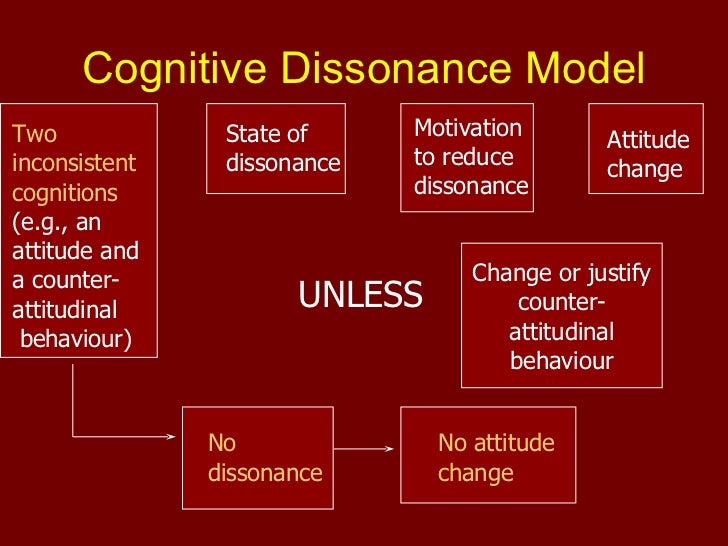

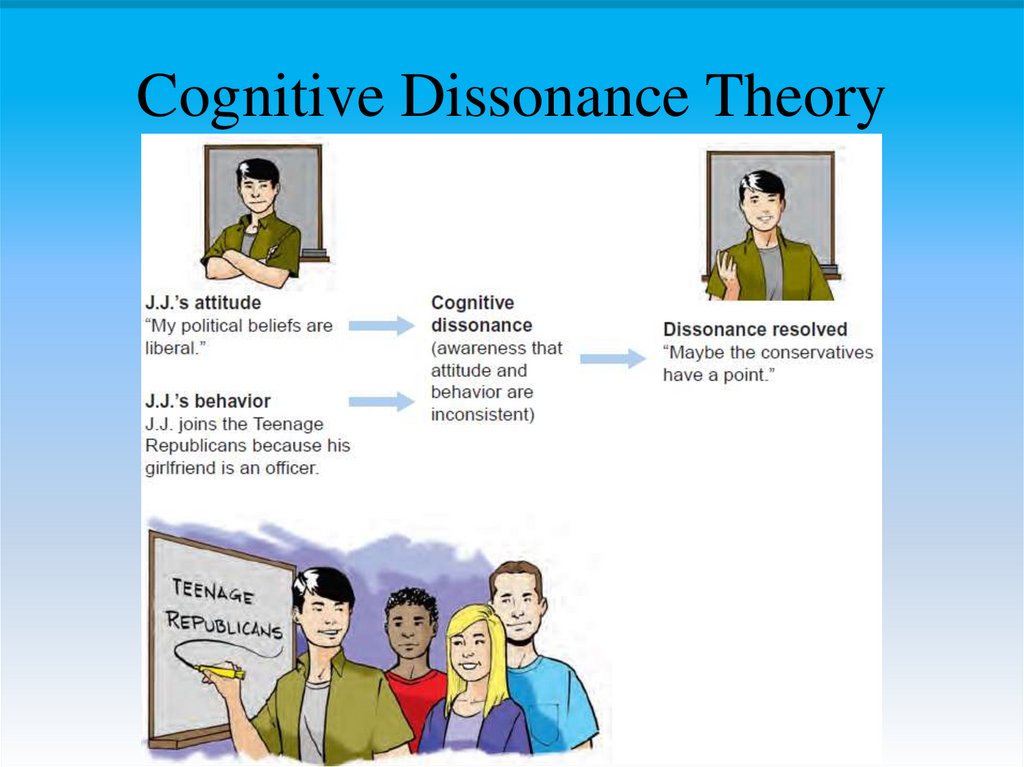

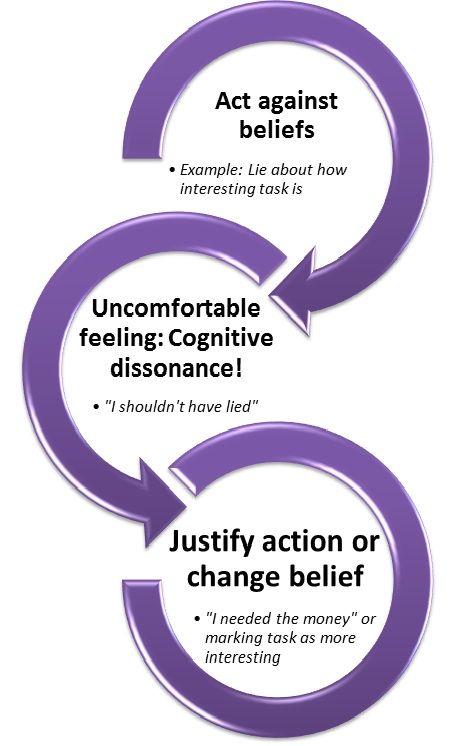

Cognitive dissonance occurs when there is an uncomfortable tension between two or more beliefs that are held simultaneously. 2 This most commonly occurs when our behaviors do not align with our attitudes – we believe one thing, but act against those beliefs. The strength of cognitive dissonance, or the pain it causes, depends on the number and relative weight of the conflicting beliefs. This mental conflict and the resulting discomfort motivates us to pick between beliefs by justifying and rationalizing one while rejecting or reducing the importance of the others.

2 This most commonly occurs when our behaviors do not align with our attitudes – we believe one thing, but act against those beliefs. The strength of cognitive dissonance, or the pain it causes, depends on the number and relative weight of the conflicting beliefs. This mental conflict and the resulting discomfort motivates us to pick between beliefs by justifying and rationalizing one while rejecting or reducing the importance of the others.

We tend to pick the belief or idea that is most familiar and ingrained in us. Changing our beliefs isn’t easy, nor is changing the attitudes and behaviour associated with them. As a result, we usually stick with the beliefs we already hold, as opposed to adopting new ones that are presented to us. In fact, many of us go further by avoiding situations or information that might clash with our existing beliefs to create dissonance.

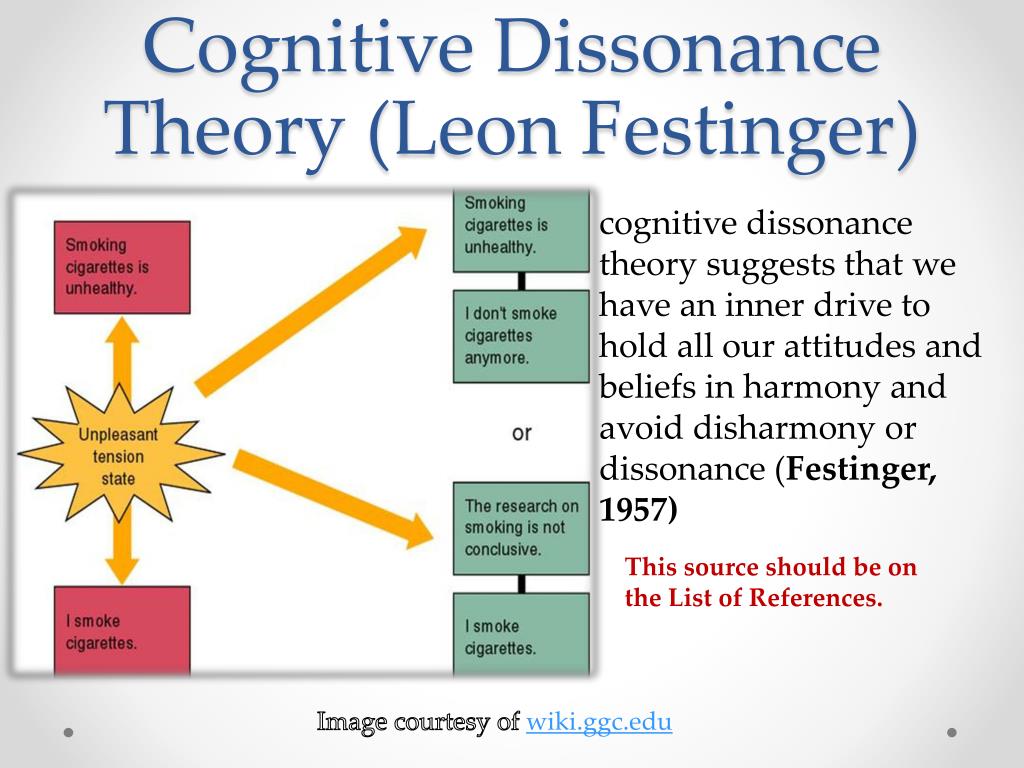

Psychologist Leon Festinger is credited with pioneering cognitive dissonance. He offers three explanations for why someone might be unwilling to change their existing beliefs or behaviour in light of new, conflicting information:

- “The change may be painful or involve loss.

” As mentioned above, changing our behavior or beliefs can be difficult— especially if they are deeply held or likely to bring hardship.

” As mentioned above, changing our behavior or beliefs can be difficult— especially if they are deeply held or likely to bring hardship. - "The present behavior may be otherwise satisfying.” Think of smokers, many of whom know the adverse consequences of their behavior but succumb to the satisfaction that outweighs it. They are reluctant to accept information that confirms the future costs.

- “Making the change may simply not be possible.” Festinger admits that this is unlikely, but still possible. Some emotional reactions for example, can be outside of our control at the time.3

Festinger goes on to point out that it is natural for us to look for internal psychological consistency. It forms our identity and allows us to make sense of the world. This makes sense: it would be difficult to think of yourself as a whole, and complete person if all your beliefs and opinions logically contradicted each other or never lined up with your behaviour.

“...the individual strives towards consistency within himself. His opinions and attitudes, for example, tend to exist in clusters that are internally consistent.”- Leon Festinger

Why it is important

If ignored, our responses to cognitive dissonance can have harmful consequences in our personal and professional lives. Remember the smoking example? This logic can be applied elsewhere in our personal lives. Avoiding dissonance may prevent us from considering new information and consequently, from changing harmful behaviors. If the contradictions between our beliefs and behaviors are not sorted out by making such changes (ie. if we deal with dissonance through rationalization), we might also be subject to hypocrisy.

In our professional lives, cognitive dissonance can result in missed opportunities. If we are hard-headed in our ways and unwilling to consider information that runs against our stance, then we will be less responsive and adaptable to situations in our workplace.

Think of an executive who is convinced that the product they are launching will succeed, and to avoid the painful realization that it may not, refuses to acknowledge the cries of his engineering team who claim that the product will malfunction. Likewise, many of us might reject evidence that our careers are not headed in the right direction, instead justifying our choice to keep on the same tracks and consequently forgo a more fruitful path.

How to avoid it

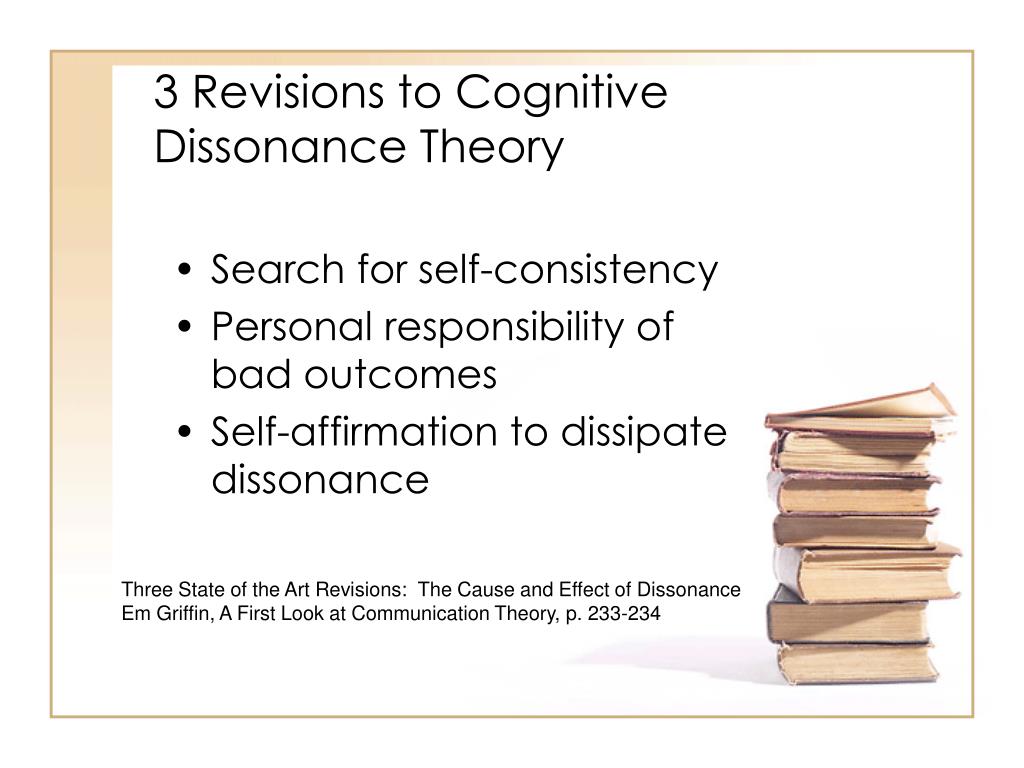

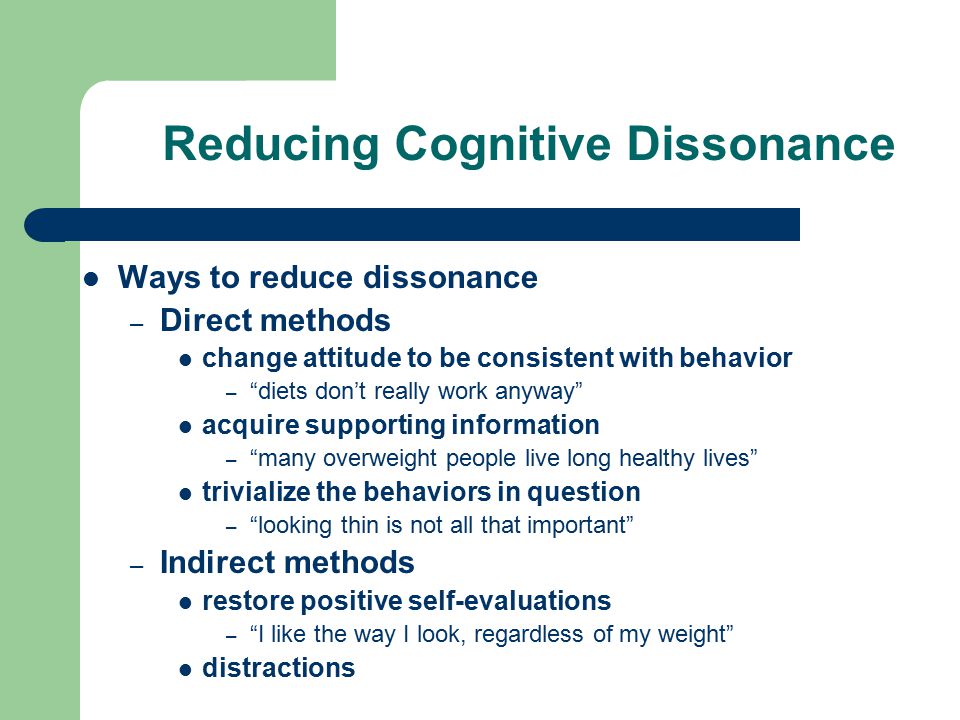

There is no way of avoiding cognitive dissonance itself. Remember that cognitive dissonance is just the discomfort we feel when our beliefs or attitudes contradict each other. What can be mitigated, is our natural response to this discomfort (ie. how we approach dissonance reduction).

As said before, our natural response to cognitive dissonance is to rationalize our existing beliefs or reject and avoid information that conflicts with them to cause dissonance. We have already noted the harms associated with doing this. Changing our beliefs when they are challenged by new information is often better than ignoring this information or rationalizing the existing beliefs which may be wrongly held. We should look to make this a more viable response to internal conflict. This is called a conditioned or “learned reflexive response.”4

Changing our beliefs when they are challenged by new information is often better than ignoring this information or rationalizing the existing beliefs which may be wrongly held. We should look to make this a more viable response to internal conflict. This is called a conditioned or “learned reflexive response.”4

A general strategy may be to accept that conflict and the resulting change can be good for us. We can all think of past behaviors and attitudes that we are thankful to have changed. And although, as Festinger said, conflict and change “may be painful or involve loss,” it often doesn’t. Thinking of change negatively may cause us to avoid employing it when in dissonance. So, we should instead seek to associate change with gratification and gain. This may condition us to favour it as a response to mental conflict rather than rejecting, rationalizing, or avoiding information.

And as always, being aware of a cognitive bias that normally occurs subsciously can help us recognize when our decisions are influenced by it. This is to say, understanding and looking for cognitive dissonance in our decision-making can help us realize when our decision to reject rationalize, or avoid new information is caused by it.

This is to say, understanding and looking for cognitive dissonance in our decision-making can help us realize when our decision to reject rationalize, or avoid new information is caused by it.

How it all started

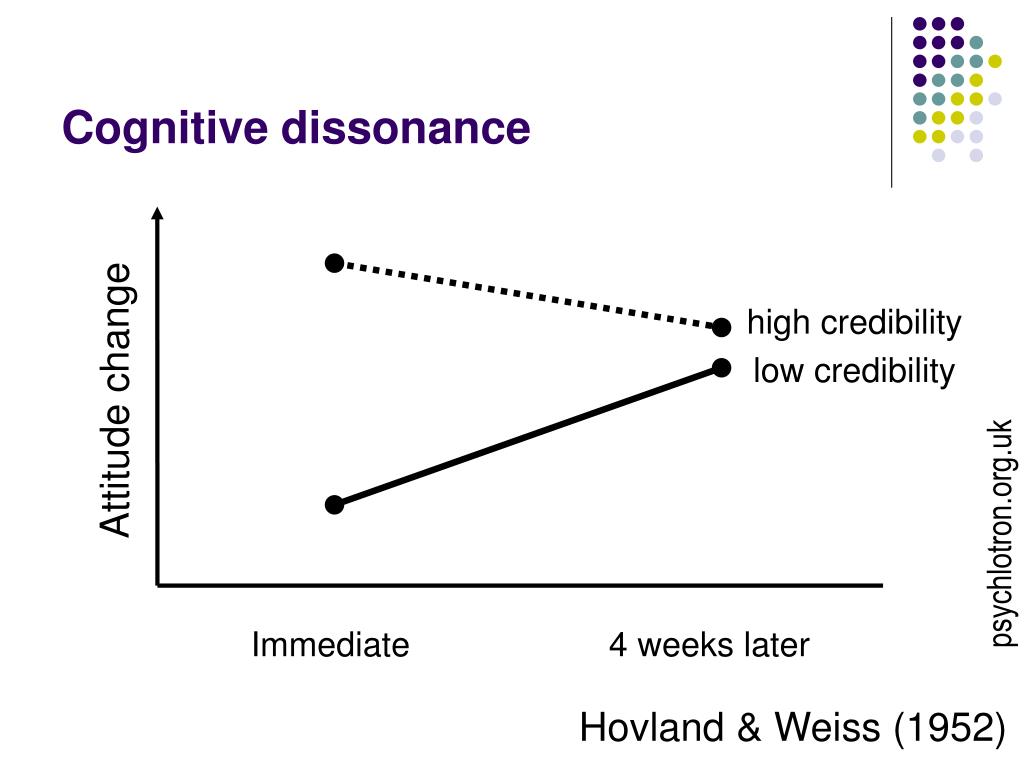

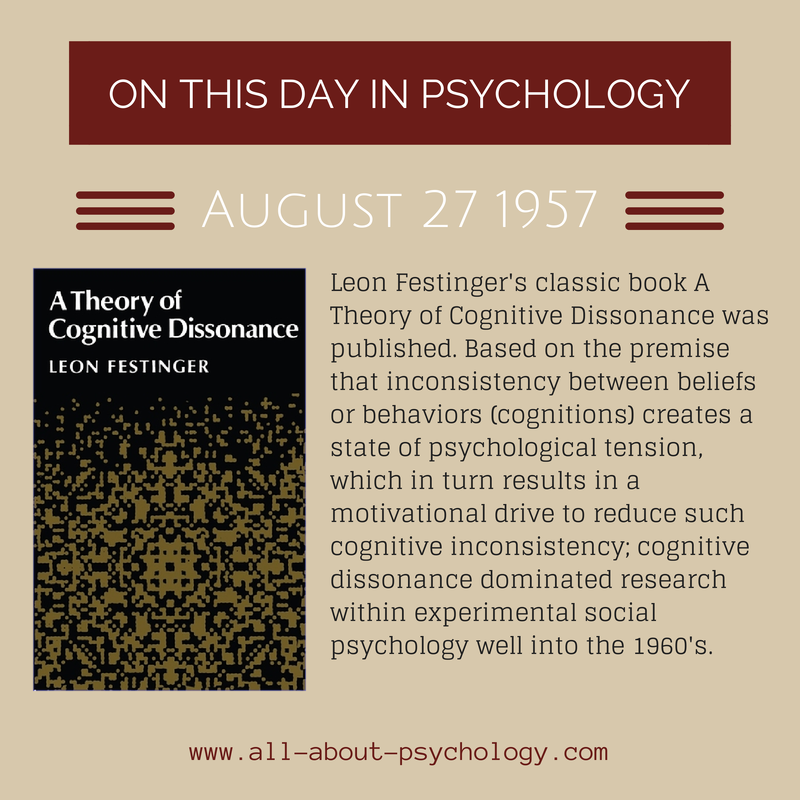

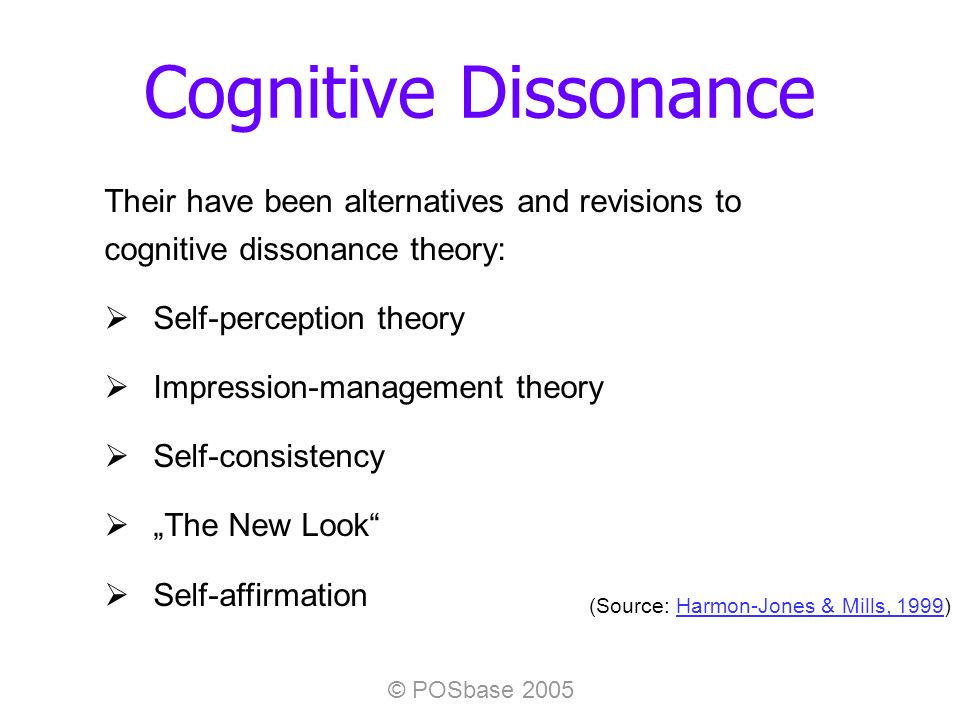

While American psychologist Jack Brehm was the first to investigate the relationship between dissonance and decision making in 1956, psychologist Leon Festinger was the first to formulate it into a theory of social psychology. In his seminal book published in 1957, A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance, Festinger details his theory and points to its influence in the psychology of learning.

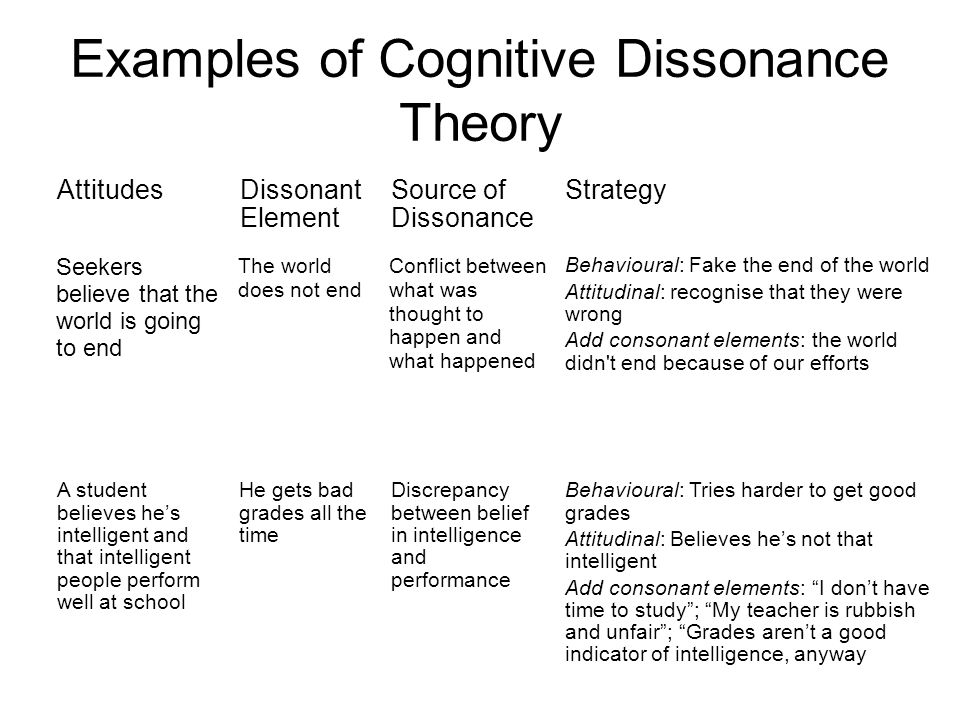

Festinger became interested in the phenomenon during his time at the University of Minnesota, during which he read about doomsday cults who believed messages from extraterrestrial aliens were communicating the world would end with a great flood on a specific date. He was curious about how they would react when the prophecy failed.

He studied their response, noting that instead of abandoning the cult and their philosophy, committed members doubled-down and increased their efforts to recruit others.

Festinger concluded that members had this response to lessen the pain of disconfirmation, which sparked an inquiry into cognitive dissonance.5

Example 1 - Avoiding the doctor

Many of us avoid getting medical screenings when it is often in our best interest to do so. We convince ourselves that the symptoms are ‘probably nothing’ and that it will ‘go away by itself.’ This can be problematic for public health.

In 2016, researchers Michael Ent and Mary Gerend analyzed two studies on the relationship between cognitive dissonance on people’s negative attitudes towards beneficial medical screening.

In one of the studies, participants were told about an unpleasant test for a virus (which was fictitious). Half of them were told they qualified for testing, and the other half was led to believe they were not.

The results showed that eligible participants reported less favorable attitudes toward the unpleasant screening than those who were ineligible. So, the unpleasantness of a medically reviewed screening affected candidates’ attitudes towards it more than non-candidate’s attitudes. This was attributed to the experience of cognitive dissonance. Participants were caught in a clash between the obligation they feel towards maintaining their health through screening, and the discomfort of going through the screening. To deal with this dissonance, many participants looked down on the screening.6 These results speak to a broader tendency for people attempting to deal with dissonance by avoiding actions that actually benefit them.

So, the unpleasantness of a medically reviewed screening affected candidates’ attitudes towards it more than non-candidate’s attitudes. This was attributed to the experience of cognitive dissonance. Participants were caught in a clash between the obligation they feel towards maintaining their health through screening, and the discomfort of going through the screening. To deal with this dissonance, many participants looked down on the screening.6 These results speak to a broader tendency for people attempting to deal with dissonance by avoiding actions that actually benefit them.

“These results suggest that cognitive dissonance may lead people to adopt negative attitudes toward beneficial, yet uncomfortable, medical procedures...this is the first evidence to suggest that cognitive dissonance could negatively affect health-related decision-making.”

– Health psychologists Michael Ent and Mary Gerend

Example 2 - Not listening to the other side

As mentioned earlier, we often don’t give enough credence to evidence that challenges the political figures or ideologies that we believe in. Our loyalties do the thinking for us. This can have the added effect of preventing conflict resolution.

Our loyalties do the thinking for us. This can have the added effect of preventing conflict resolution.

In 2002, a team of researchers led by social psychologist Lee Ross investigated the tendency for political enemies to derogate each other's compromise proposals by conducting studies on Palestinian-Israeli perceptions. In one study, Israeli Jews were found to evaluate a peace plan less favorably when it was attributed to the Palestinians than when it was attributed to their own government. In reality, the peace plan was actually Israeli-authored.

Ross in part attributes this to a “process whereby the content of a proposal is considered and interpreted (if the proposal comes from the other side) in a manner that renders the proposal less palatable.” In other words, a proposal is largely evaluated by looking at who wrote it, rather than its content. A proposal by an adversary is likely to be devalued because it was proposed by the adversary— even when it is objectively beneficial.

One reason for this, Ross says, is cognitive dissonance. Adversaries may devalue or reject peace proposals in order to rationalize their history and beliefs. In other words, settlements are interpreted in a way that justifies the past position they took in the struggle.7 This phenomenon is not limited to the Israel-Palestine conflict. We have a tendency to interpret information given by our political adversaries in a way that meshes with our own political convictions.

““A list of these psychological barriers might begin with cognitive dissonance, which can lead disputants to reject present settlement offers to rationalize past struggles.”

– Lee Ross, et al.

Summary

What it is

Cognitive Dissonance is a theory proposing that we avoid having conflicting beliefs and attitudes because it makes us uncomfortable. The clash is usually dealt with by rejecting, debunking, or avoiding new information.

Why it happens

Cognitive dissonance occurs when there is an uncomfortable tension between two or more beliefs that are held simultaneously. This most commonly occurs when our attitudes and behavior do not align with our attitudes – we believe one thing, but act against those beliefs. The resulting discomfort motivates us to pick between beliefs by rationalizing one and rejecting or delegitimizing the other(s). We tend to pick the belief or idea that is most ingrained in us, which is the one we already hold. It is natural for us to look for internal psychological consistency, as it forms our identity and allows us to make sense of the world.

Example #1 - Avoiding the doctor

A 2016 analysis of two studies by researchers Michael Ent and Mary Gerend details our reluctance to undergo beneficial medical screenings. In one of the studies, participants were told about an unpleasant test for a virus. Half of them were told they qualified for testing, and the other half was told they did not. Results showed that eligible participants reported less favorable attitudes toward the unpleasant screening than those who were ineligible. Participants were caught in a clash between the obligation they feel towards maintaining their health through screening, and the discomfort of going through the screening. To deal with this dissonance, many participants looked down on the screening.

Results showed that eligible participants reported less favorable attitudes toward the unpleasant screening than those who were ineligible. Participants were caught in a clash between the obligation they feel towards maintaining their health through screening, and the discomfort of going through the screening. To deal with this dissonance, many participants looked down on the screening.

Example #2 - Not listening to the other side

We have a tendency to interpret information given by our political adversaries in a way that meshes with our own political convictions. A 2002 study investigated the tendency for political enemies to derogate each other's compromise proposals by conducting studies on Palestinian-Israeli perceptions. Israeli Jews were found to evaluate a peace plan less favorably when it was attributed to the Palestinians than when it was attributed to their own government. In reality, the peace plan was actually Israeli-authored. One reason for this, the researchers conclude, is cognitive dissonance. Adversaries may devalue or reject peace proposals in order to rationalize their history and beliefs.

Adversaries may devalue or reject peace proposals in order to rationalize their history and beliefs.

How to avoid it

There is no way of avoiding cognitive dissonance itself. What can be mitigated, is our natural response to it. Changing our beliefs when they are challenged by new information is often better than ignoring this information or rationalizing the existing beliefs which may be wrongly held. Thinking of change negatively may cause us to avoid employing it when in dissonance. So, we should instead seek to associate change with gratification and gain. This is called a conditioned or “learned reflexive response.” By conditioning ourselves to favour change as a response to mental conflict, we might be able to avoid rejecting, rationalizing, or avoiding conflicting information. And as always, being aware of a cognitive bias that normally occurs subsciously can help us recognize when our decisions are influenced by it.

Related TDL articles

AI, Indeterminism and Good Storytelling

This article looks at how artificial intelligence helps us make decisions or makes decisions for us. In support, the author claims that individuals’ cognitive dissonance can influence the probabilistic models used to make policy decisions.

In support, the author claims that individuals’ cognitive dissonance can influence the probabilistic models used to make policy decisions.

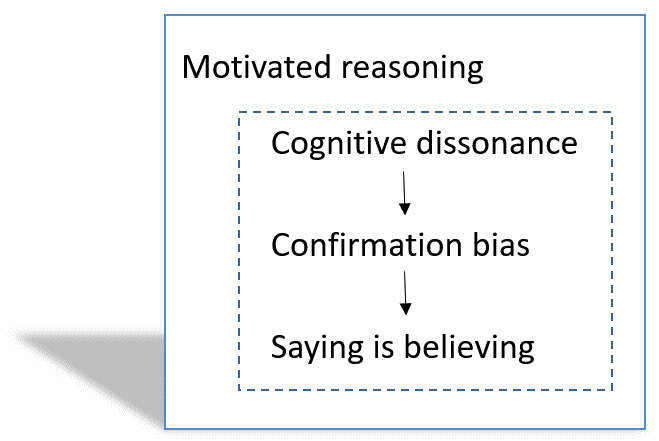

How To Fight Fake News With Behavioral Science

This article outlines the reasons why we are susceptible to fake news, and we can fight the uptake of false information. One reason why we are influenced by fake news is that it can be consistent with our own beliefs. Cognitive dissonance and confirmation bias might therefore play a role, as we are more inclined to rationalize our existing beliefs than have them challenged by legitimate news sources.

Cognitive dissonance: Definition, effects, and examples

Cognitive dissonance is the discomfort a person feels when their behavior does not align with their values or beliefs. It can also occur when a person holds two contradictory beliefs at the same time.

Cognitive dissonance is not a disease or illness. It is a psychological phenomenon that can happen to anyone. American psychologist Leon Festinger first developed the concept in the 1950s.

Read on to learn more about cognitive dissonance, including examples, signs a person might be experiencing it, causes, and how to resolve it.

A note about sex and gender

Sex and gender exist on spectrums. This article will use the terms “male,” “female,” or both to refer to sex assigned at birth. Click here to learn more.

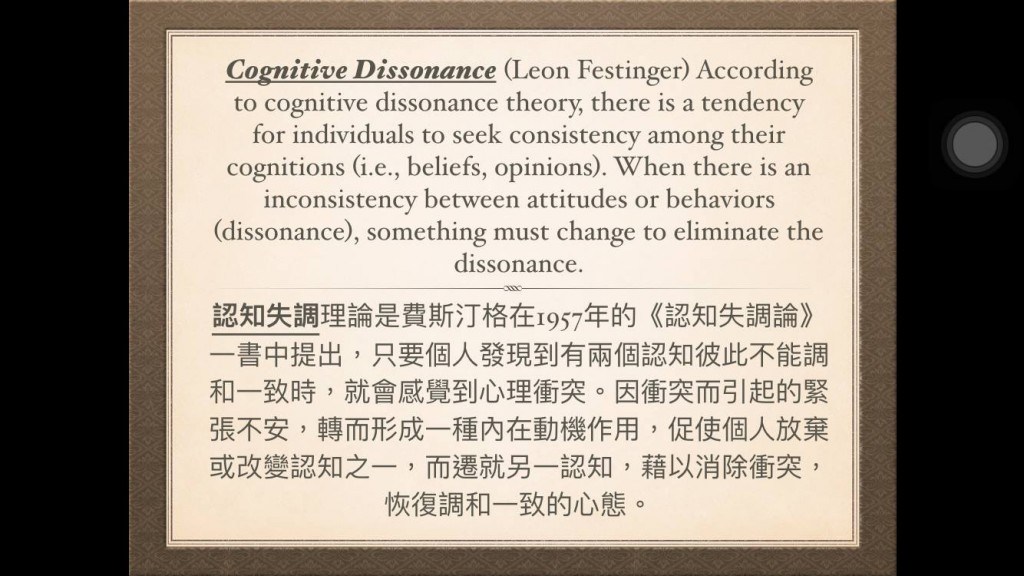

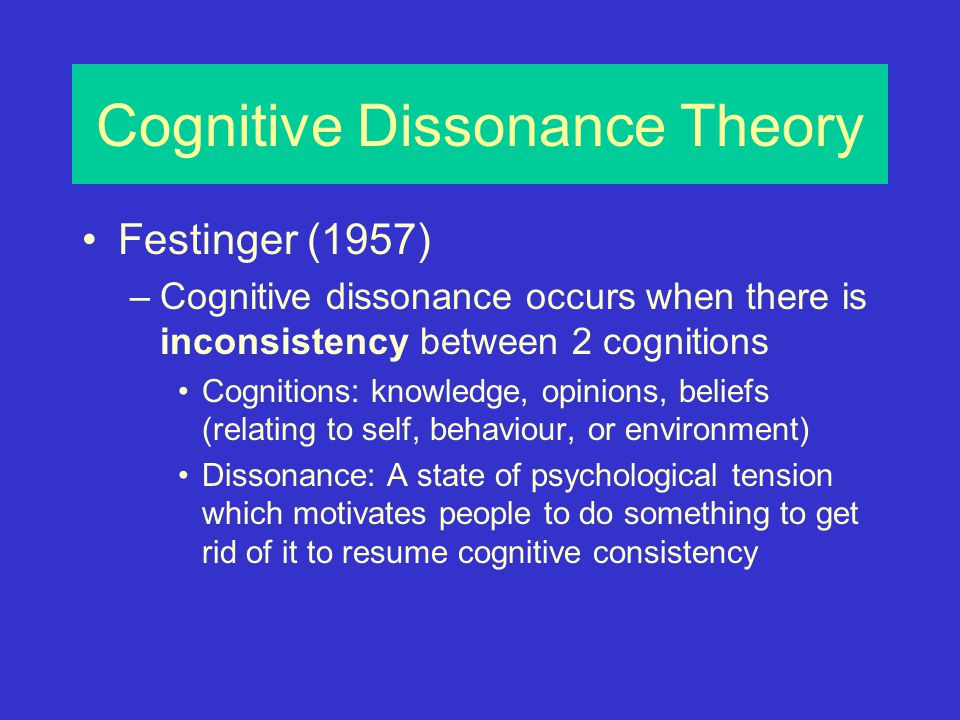

Cognitive dissonance occurs when a person holds two related but contradictory cognitions, or thoughts. The psychologist Leon Festinger came up with the concept in 1957.

In his book A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance, Festinger proposed that two ideas can be consonant or dissonant. Consonant ideas logically flow from one another, while dissonant ideas oppose one another.

For example, a person who wishes to protect other people and who believes that the COVID-19 pandemic is real might wear a mask in public. This is consonance.

If that same person believed the COVID-19 pandemic was real but refused to wear a mask, their values and behaviors would contradict each other. This is dissonance.

This is dissonance.

The dissonance between two contradictory ideas, or between an idea and a behavior, creates discomfort. Festinger argued that cognitive dissonance is more intense when a person holds many dissonant views, and those views are important to them.

It is not possible to observe dissonance, as it is something a person feels internally. As such, there is no set of external signs that can reliably indicate a person is experiencing cognitive dissonance.

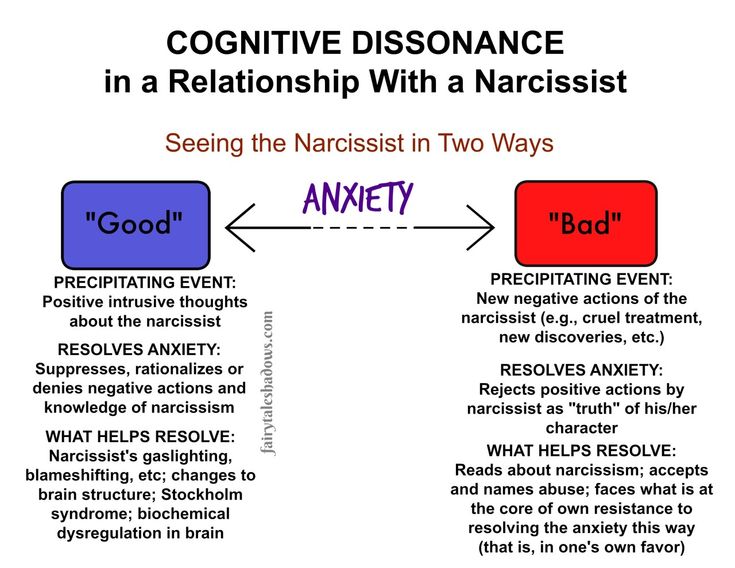

However, Festinger believed that all people are motivated to avoid or resolve cognitive dissonance due to the discomfort it causes. This can prompt people to adopt certain defense mechanisms when they have to confront it.

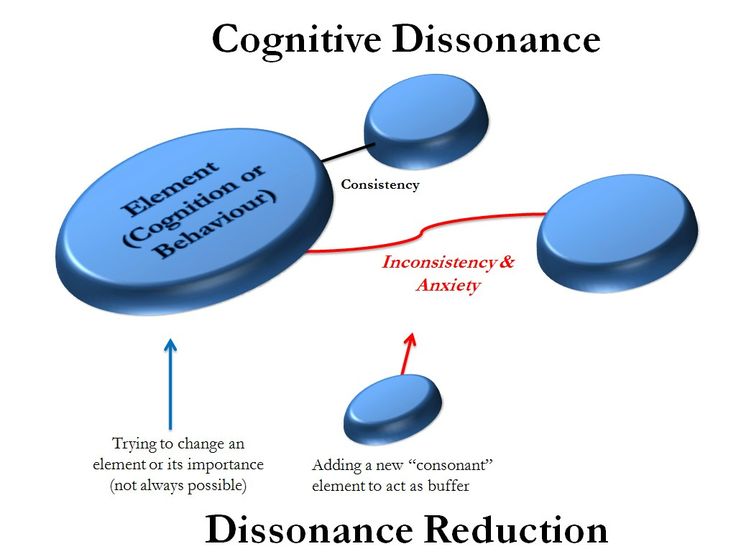

These defense mechanisms fall into three categories:

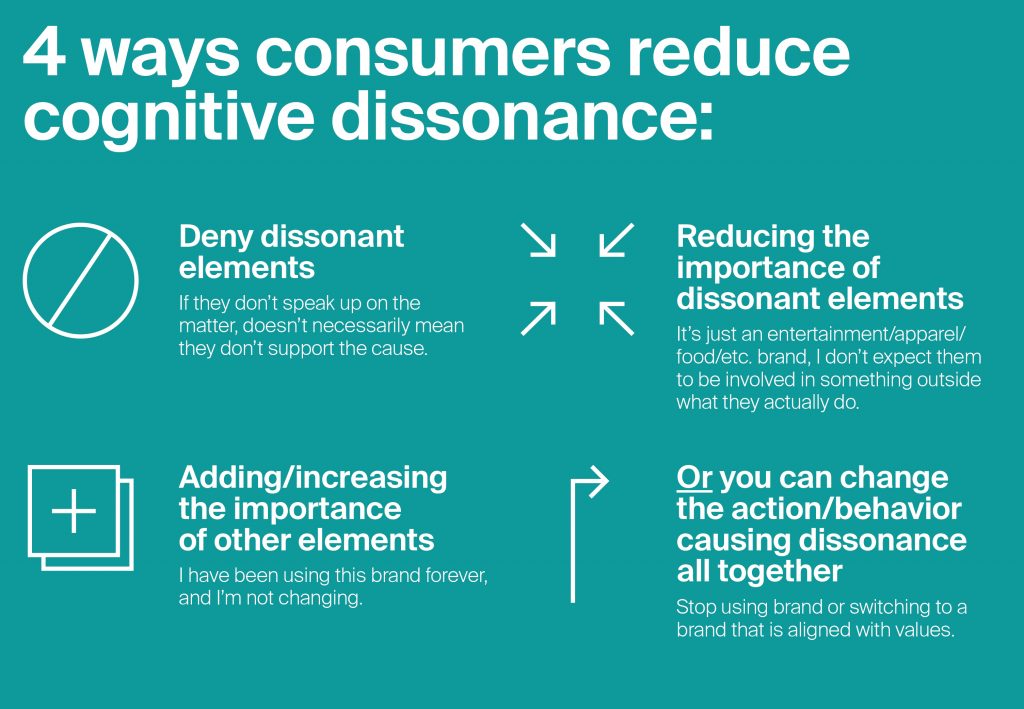

- Avoiding: This involves avoiding or ignoring the dissonance. A person may avoid people or situations that remind them of it, discourage people from talking about it, or distract themselves from it with consuming tasks.

- Delegitimizing: This involves undermining evidence of the dissonance. A person may do this by discrediting the person, group, or situation that highlighted the dissonance. For example, they might say it is untrustworthy or biased.

- Limiting impact: This involves limiting the discomfort of cognitive dissonance by belittling its importance. A person may do this by claiming the behavior is rare or a one-off event, or by providing rational arguments to convince themselves or others that the behavior is OK.

Alternatively, people may take steps to try to resolve the inconsistency. It is possible to resolve cognitive dissonance by either changing one’s behavior or changing one’s beliefs so they are consistent with each other.

Some examples of cognitive dissonance include:

- Smoking: Many people smoke even though they know it is harmful to their health. The magnitude of the dissonance will be higher in people who highly value their health.

- Eating meat: Some people who view themselves as animal lovers eat meat and may feel discomfort when they think about where their meat comes from. Some researchers refer to this as the “meat paradox.”

- Doing household chores: A male might believe in equality of the sexes but then consciously or unconsciously expect their female partner to do most of the household labor or childrearing.

- Supporting fast fashion: A person might be aware of the effects of fast fashion on the environment and workers but still purchase cheap clothes from companies that engage in harmful practices.

Anyone can experience cognitive dissonance, and sometimes, it is unavoidable. People are not always able to behave in a way that matches their beliefs.

Some factors that can cause cognitive dissonance include:

- Forced compliance: A person may have to do things they disagree with as part of a job, to avoid bullying or abuse, or to follow the law.

- Decision-making: Everyone has limited choices. When a person must make a decision among several options they do not like or agree with, or they only have one viable option, they may experience cognitive dissonance.

- Effort: People tend to value things they work hard for highly, even if those things contradict a person’s values. This may be because viewing something negatively after putting in a lot of hard work would cause more dissonance. So people are more likely to view difficult tasks positively, even if they do not morally agree with them.

Another factor that can create cognitive dissonance is addiction. A person might not want to engage in dissonant behavior, but addiction can make it feel physically and mentally difficult to bring their behavior into alignment with their values.

Cognitive dissonance can affect people in a wide range of ways. The effects may relate to the discomfort of the dissonance itself or the defense mechanisms a person adopts to deal with it.

The internal discomfort and tension of cognitive dissonance could contribute to stress or unhappiness. People who experience dissonance but have no way to resolve it may also feel powerless or guilty.

Avoiding, delegitimizing, and limiting the impact of cognitive dissonance may result in a person not acknowledging their behavior and thus not taking steps to resolve the dissonance. In some cases, this could cause harm to themselves or others.

However, cognitive dissonance can also be a tool for personal and social change. Drawing a person’s attention to the dissonance between their behavior and their values may increase their awareness of the inconsistency and empower them to act.

For example, a 2019 study notes that dissonance-based interventions may be helpful for people with eating disorders. This approach works by encouraging patients to say things or role-play behaviors that contradict their beliefs about food and body image. This creates dissonance.

The theory behind this approach is that in order to resolve the dissonance, a person’s implicit beliefs about their body and thinness will change, reducing their desire to limit their food intake.

The study found that this intervention was effective for heterosexual women but less effective for nonheterosexual women for reasons that are unclear.

The most effective way to resolve cognitive dissonance is for a person to ensure that their actions are consistent with their values, or vice versa.

A person can achieve this by:

- Changing their actions: This involves changing behavior so it matches a person’s beliefs. Where a full change is not possible, a person could make compromises. For instance, a person who cares about the environment but works for a company that pollutes might advocate for change at work, if they cannot leave their job.

- Changing their thoughts: If a person often behaves in a way that contradicts their beliefs, they may come to question how important that belief is or find that they no longer believe it. Alternatively, they might add new beliefs that bring their actions more closely in line with their thinking.

- Changing their perception of the action: If a person cannot or does not want to change the behavior or beliefs that cause dissonance, they may view the behavior differently instead. For example, a person who cannot afford to buy from sustainable brands might forgive themselves for this and acknowledge that they are doing the best they can.

Cognitive dissonance is not a mental health condition, and a person does not necessarily need treatment for it. However, if a person finds that they have difficulty stopping a behavior or thinking pattern that is causing them distress, they can seek support from a doctor or therapist.

A person may wish to consider this if:

- they have an addiction

- the behavior causes problems at work, at school, or in relationships

- they feel stressed, anxious, or low

- they feel overwhelming guilt or shame

Cognitive dissonance occurs when a person’s behavior and beliefs do not complement each other or when they hold two contradictory beliefs. It causes a feeling of discomfort that motivates people to try to feel better.

It causes a feeling of discomfort that motivates people to try to feel better.

People may do this via defense mechanisms, such as avoidance. Alternatively, they may reduce cognitive dissonance by being mindful of their values and pursuing opportunities to live those values.

A person who feels defensive or unhappy might consider the role cognitive dissonance might play in these feelings. If they are part of a wider problem that is causing distress, people may benefit from speaking with a therapist.

Cognitive dissonance: what it is, examples, how to recognize it, how to overcome it

“I have cognitive dissonance,” we hear when describing any discrepancy between expectation and reality. This term has already become so widely used that not everyone thinks about its true meaning. Let's figure it out.

The author of the article is Angelina Duka, Ph.D. Advertising on RBC www.adv.rbc.ru

What is cognitive dissonance

Cognitive dissonance is an internal conflict that occurs in a person when conflicting beliefs collide. This dissonance causes a feeling of tension; a person experiences unpleasant emotions: anxiety, anger, shame, guilt - and will strive to get rid of discomfort in various ways. The concept of "cognitive dissonance" came to us from social psychology.

This dissonance causes a feeling of tension; a person experiences unpleasant emotions: anxiety, anger, shame, guilt - and will strive to get rid of discomfort in various ways. The concept of "cognitive dissonance" came to us from social psychology.

Theory of cognitive dissonance

The concept of cognitive dissonance was first introduced by the social psychologist Leon Festinger. He suggested that in the presence of conflicting beliefs, people would experience emotional discomfort. In his study of rumor belief, Festinger concluded that people always strive for an internal balance between personal motives that determine their behavior and information received from outside. Festinger's theory describes how people try to rationalize their behavior. Dissonance occurs when a person simultaneously encounters two incompatible, but equally significant judgments - cognitions. What it is? Sometimes thoughts are meant by cognitions, but in fact this concept is much broader: thoughts, ideas, opinions, value judgments should be included here. In some situations, they provide mental stability, protecting us from intense experiences. However, sometimes this protection is achieved in a peculiar way - by self-deception.

In some situations, they provide mental stability, protecting us from intense experiences. However, sometimes this protection is achieved in a peculiar way - by self-deception.

Does everyone experience cognitive dissonance the same way? No. Different people have different tolerances for uncertainty, so the degree of dissonance experienced will vary in intensity. The strength of dissonance is also affected by how strongly personal value beliefs are affected.

A still from the TV series The Queen's Move

© Kinopoisk

Why cognitive dissonance occurs

Social behavior researchers Anthony Pratkanis and Elliot Aronson suggested that the mental activity of any person is largely determined by two principles that explain the irrationality of some actions.

The principle of mental stereotypes

Our brain reduces costs where it is possible. We strive to preserve the so-called cognitive energy, reducing its consumption to a minimum and using mental stereotypes wherever possible. This principle has both positive and negative effects. On the one hand, we, for example, create algorithms for solving typical problems and thereby simplify our work. On the other hand, in order to simplify complex problems, we often choose not a justified conclusion, but one that does not require deep reflection. Figuratively speaking, we are looking for keys not where we lost them, but where it is brighter.

This principle has both positive and negative effects. On the one hand, we, for example, create algorithms for solving typical problems and thereby simplify our work. On the other hand, in order to simplify complex problems, we often choose not a justified conclusion, but one that does not require deep reflection. Figuratively speaking, we are looking for keys not where we lost them, but where it is brighter.

Critical thinking requires additional resources, just as breaking any formed habit requires effort. Ignoring a comprehensive assessment of the situation, some repeat past mistakes many times and bring themselves into a state of debilitating stress.

The principle of rationalization of one's behavior, or the principle of self-explanation

It is common for any of us to give our actions a reasonable justification so that they seem logical both to ourselves and to our environment. Self-explanation acts as a guideline, as an ideological basis: “I do this because . ..” - the continuation of the phrase will be different for everyone. A person must perceive his own behavior as reasonable and understandable - otherwise there is a threat to the integrity of his "I". However, the way we explain our actions does not always correspond to reality: very often, trying to calm ourselves, we wishful thinking through self-deception and rationalization.

..” - the continuation of the phrase will be different for everyone. A person must perceive his own behavior as reasonable and understandable - otherwise there is a threat to the integrity of his "I". However, the way we explain our actions does not always correspond to reality: very often, trying to calm ourselves, we wishful thinking through self-deception and rationalization.

These principles illustrate how a person rationalizes their behavior to avoid discomfort.

Shot from the movie "1+1"

© Kinopoisk

Examples of cognitive dissonance

Let's look at a simple example of how you can encounter cognitive dissonance. Choosing, say, a car, we compare different models and make a choice in favor of one of them. We are happy with our purchase and believe we made the best choice possible. If, after buying a car, we come across information that calls into question the correctness of our decision, then we will ignore it, even if it is true. Or we will justify ourselves by saying, "My car is better anyway. " Or, talking about other cars, we will recall examples of how bad they are in operation, look for confirmation on forums, among friends. Thus, we strive to save ourselves from discomfort and maintain a positive attitude towards ourselves. At the same time, finding information confirming the correctness of our choice, we will certainly notice it and experience positive emotions, since we will unconsciously perceive it as speaking in favor of our positive self-image.

" Or, talking about other cars, we will recall examples of how bad they are in operation, look for confirmation on forums, among friends. Thus, we strive to save ourselves from discomfort and maintain a positive attitude towards ourselves. At the same time, finding information confirming the correctness of our choice, we will certainly notice it and experience positive emotions, since we will unconsciously perceive it as speaking in favor of our positive self-image.

Russian classical literature is full of examples of cognitive dissonance when the hero makes a difficult choice. Thus, in The Quiet Don, Sholokhov, through the prism of the families of the Melekhovs, Korshunovs and other characters, shows how individuals make difficult decisions at critical moments and cope with cognitive dissonance.

How to Overcome Cognitive Dissonance

By looking at typical behaviors, you can understand how to deal with the discomfort of cognitive dissonance.

Avoiding or devaluing factual information

This strategy helps people continue to maintain behaviors with which they do not fully agree (for example, I know that smoking is bad, but I continue to do so). To reduce cognitive dissonance, a person can limit access to new information that does not correspond to his beliefs, devalue these facts, perceiving them as false, avoid studying additional sources and situations in which alternative points of view can be encountered.

To reduce cognitive dissonance, a person can limit access to new information that does not correspond to his beliefs, devalue these facts, perceiving them as false, avoid studying additional sources and situations in which alternative points of view can be encountered.

Rationalization

Justifying oneself, trying to make sure that internal conflict does not exist. People begin to seek support among those who share similar views, or try to convince the other that the new information is inaccurate; looking for ways to justify behavior that goes against their beliefs. Unfortunately, often behind explanations that seem rational to us, in fact, there are irrational beliefs containing logical errors that are not supported by facts, and this causes us suffering.

Changing one's behavior

Discomfort can push a person to change their behavior so that actions are consistent with their beliefs. As a result of cognitive dissonance, many people are faced with a conflict of values, resolving which they can bring positive changes to their lives, move closer to the ideal in accordance with which they want to live - this is the case when cognitive dissonance can have a positive impact. For example, a person eats a lot of sugary fatty foods every day, while he is at risk of diabetes and he is aware of the consequences. Feeling discomfort from cognitive dissonance, he eventually changes his behavior: he corrects his diet, thereby taking a step towards his value - health.

For example, a person eats a lot of sugary fatty foods every day, while he is at risk of diabetes and he is aware of the consequences. Feeling discomfort from cognitive dissonance, he eventually changes his behavior: he corrects his diet, thereby taking a step towards his value - health.

A still from the film Bridget Jones's Diary

© Kinopoisk

The development of critical thinking

It is possible to establish the truth by analyzing the arguments of each side of cognitive dissonance.

To do this, you need to answer the question of whether it is logical to think so, what is the logic of judgments.

Then, with the help of empirical facts, one should weigh the two points of view and ask oneself:

- what proves my point;

- that refutes it;

- what evidence (facts, arguments) can be given in favor of the opposite point of view;

- what do I get when I think so;

- Do my thoughts help me get what I want?

As you might guess, the first two strategies are not very productive - they may bring temporary relief, but they will not relieve discomfort. The third and fourth models are the most constructive: here the internal conflict is really resolved.

The third and fourth models are the most constructive: here the internal conflict is really resolved.

So, cognitive dissonance is a phenomenon that everyone encounters. It influences our decisions in many different areas. And although cognitive dissonance may seem like a negative effect of thinking, it can help develop and change for the better, pushing us to do things that are in line with our values.

Tags: psychology

Cognitive dissonance is a discrepancy between what people believe and how they behave that motivates people to take actions that will help minimize feelings of discomfort. Society tries to reduce this tension in many ways, such as rejecting, explaining, or avoiding new information.

Everyone experiences cognitive dissonance to some degree, but that doesn't mean it's always easy to recognize. Here are some signs that your feelings may be related to dissonance:

Here are some signs that your feelings may be related to dissonance:

- feeling of discomfort before doing something or making a decision;

- trying to justify or rationalize your decision;

- feeling embarrassed or ashamed of what you have done and trying to hide your actions from other people;

- feel guilty or sorry about what you have done in the past;

- doing something out of social pressure or fear of missing out, even if you didn't want to do it

Causes

There are various situations that can create conflicts leading to cognitive dissonance.

- Forced Compliance

Sometimes, due to external expectations, you may encounter behavior that is contrary to your own beliefs, often because of work, school, or social situations. It may also be due to peer pressure or doing something at work to avoid getting fired.

- Decisions

People make decisions every day. When faced with two identical choices, they often experience a sense of dissonance because both options are equally attractive.

When faced with two identical choices, they often experience a sense of dissonance because both options are equally attractive.

Several factors can also influence the overall strength of dissonance, including: The number of discordant beliefs. The more dissonant (conflicting) thoughts you have, the stronger the dissonance.

Also, this dissonance can often greatly influence our behavior and actions. This not only affects how you feel, but also encourages you to take action to reduce your feelings of discomfort.

This discomfort can manifest itself in different ways. People may feel:

- anxiety;

- embarrassment;

- sorry;

- sadness;

- shame;

- stress.

Cognitive dissonance can even affect how we think about and see ourselves, leading to negative feelings of self-esteem and self-worth.

Dissonance can affect how people act, think and make decisions. They may act or adopt certain attitudes to alleviate the discomfort caused by the conflict.

Callback

Working with dissonance

When conflicts arise between cognitions (thoughts, beliefs, opinions), people take steps to reduce dissonance and feelings of discomfort. They can do this in several ways, for example: A person who has learned that greenhouse gas emissions cause global warming may experience a sense of dissonance if they drive a car that consumes a lot of gas. To reduce this dissonance, they may look for new information that disproves the notion that greenhouse gases contribute to global warming. The health-conscious man may be concerned to learn that prolonged sitting during the day is associated with reduced life expectancy. Since he has to work all day at the office and spend a lot of time sitting, his behavior is difficult to change. Instead, to cope with the discomfort, he could find a way to rationalize the conflicting cognition. He could justify his sedentary behavior by saying that his other healthy behaviors—healthy eating and sports, for example—compensate for his largely sedentary lifestyle.