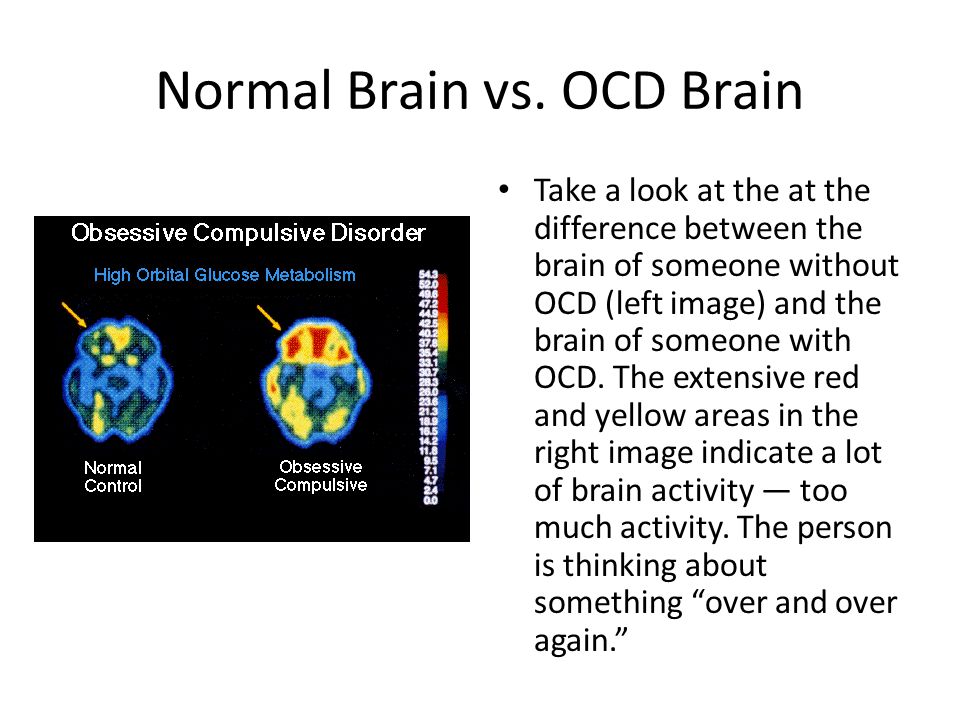

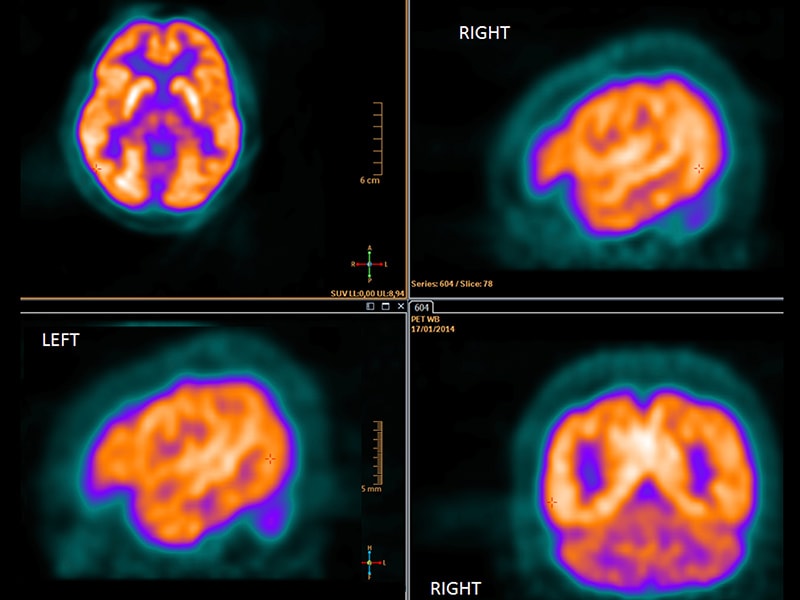

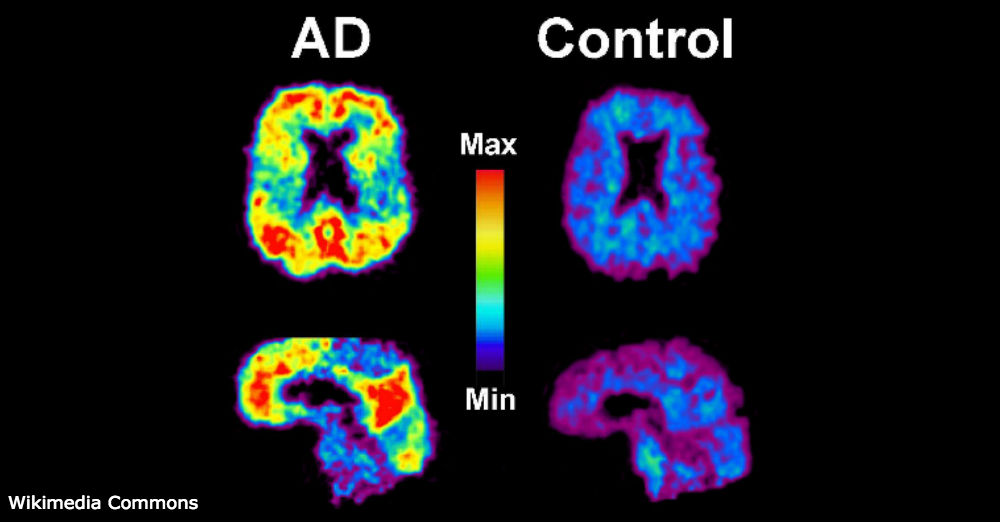

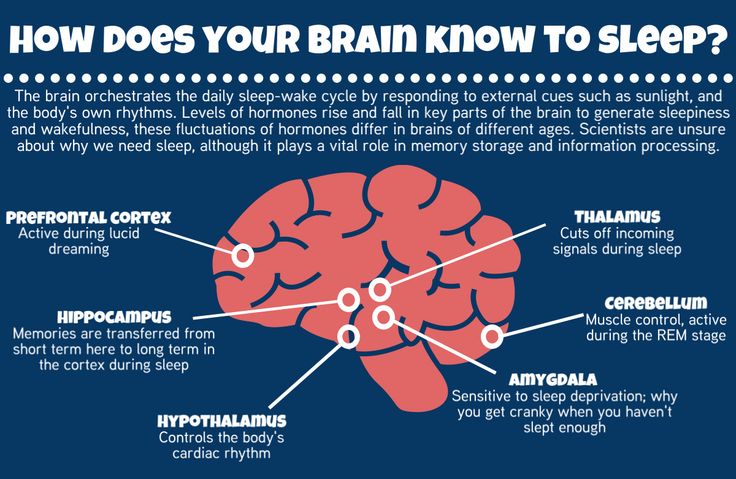

Pet scan for brain activity

Brain PET/CT Scan | Boston Children's Hospital

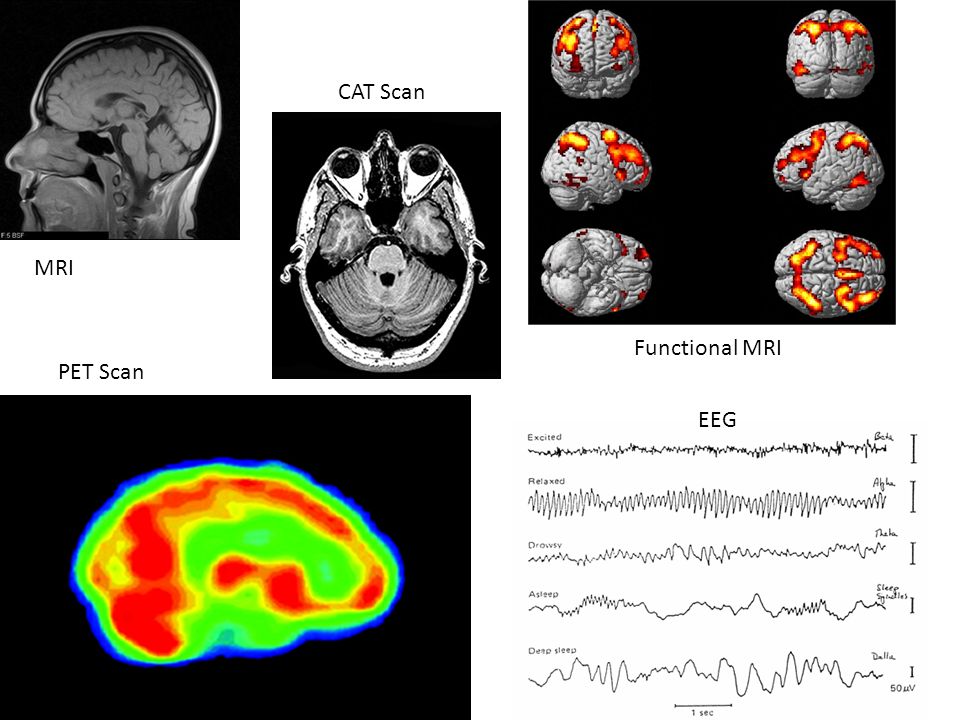

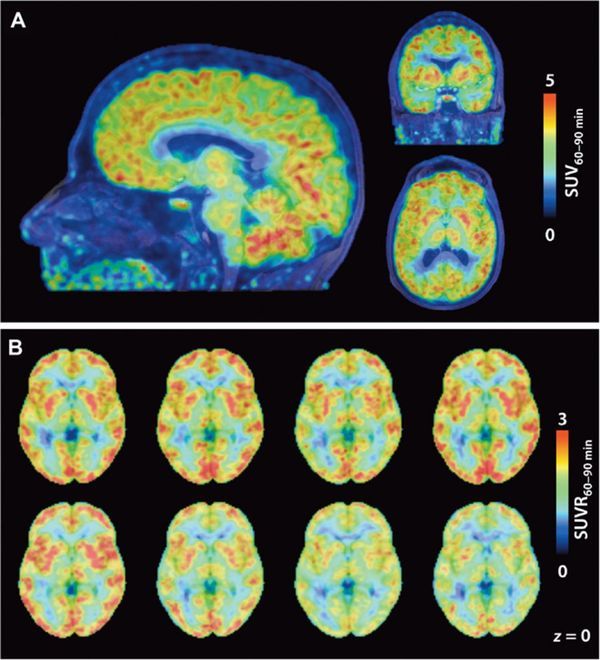

Brain Positron Emission Tomography — also called a brain PET/CT scan — is a safe, effective and non-invasive diagnostic imaging technique that provides highly detailed images of the brain. A brain PET scan shows metabolic changes that cannot be seen on MRI or CT scans.

What is a brain PET/CT scan?

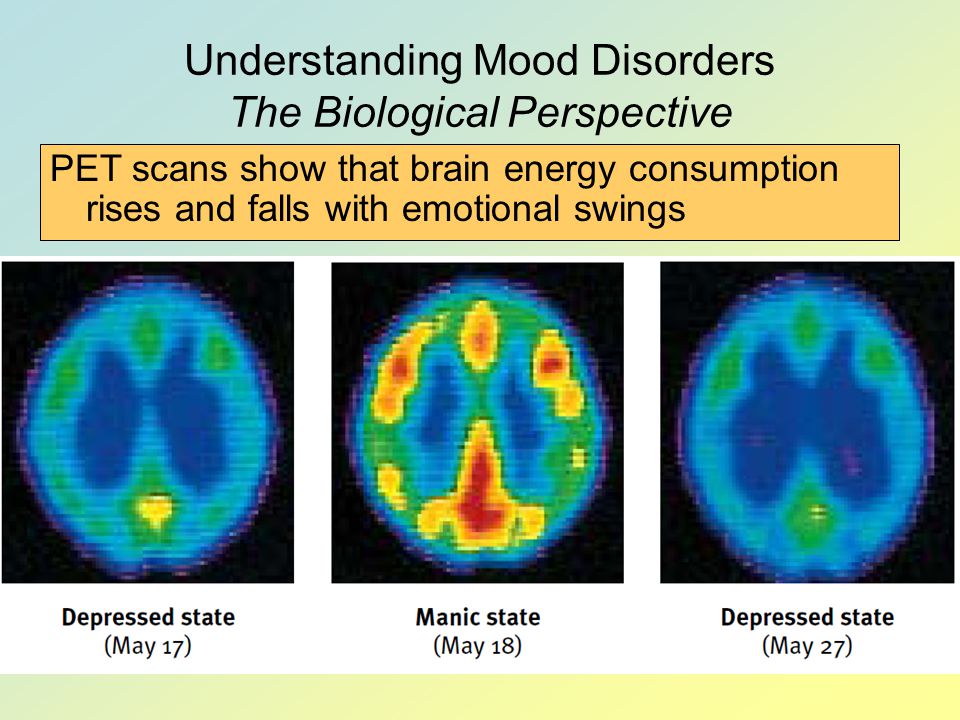

Positron emission tomography (PET) is a highly sensitive technology that uses a radioactive substance to show the chemical and functional changes within the brain.

- Chemical and functional changes cannot be seen by other imaging methods, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT).

- Images obtained from a PET/CT scan help doctors diagnose a problem, choose the best treatment, and/or see how well a treatment is working.

The radiopharmaceutical used is designed to go to the brain.

- A common type of radiopharmaceutical, fluorine-18 FDG (fluorodeoxyglucose), acts almost exactly like sugar.

- The brain consumes large amounts of glucose, so the radioactive sugar goes to the corresponding regions of the brain.

- Once the radiopharmaceutical is in the brain, the PET/CT scanner obtains 3-D images of glucose in the brain.

When might a brain PET/CT scan be needed?

A brain PET/CT is used for various conditions, including:

- epilepsy: the brain PET/CT can show which part of the brain is responsible for the seizures

- assessment of the function of a brain tumor

- assessment of brain damage due to trauma

- determine the effectiveness of surgery, radiation therapy, and/or chemotherapy in patients with brain tumors

How should I prepare my child for a brain PET/CT scan?

You will be given specific instructions when you make your child's appointment. It is very important that you follow all preparation instructions or the scan will be rescheduled. In general:

- Your child should not have any solid food or fluids four hours prior to the scan.

- Your child is allowed to drink plain water, but no flavored water.

- You may give your child his or her normal medications on the morning of the scan.

In addition:

- It is helpful to give your child a simple explanation as to why a brain PET/CT scan is needed and assure him/her that you will be with him/her for the entire time.

- You may want to bring your child's favorite book, toy, or comfort object to use during waiting times.

- If your child is scheduled for sedation or if you think sedation is necessary (to hold still) and a nuclear medicine staff member has not contacted you, please call us at 617-355-7010 for specific instructions.

You should expect your visit to last from one and one half to two hours.

What should I expect when I bring my child to the hospital for a brain PET/CT scan?

When you arrive, please go to the Nuclear Medicine check-in desk on the second floor of the main hospital. A clinical intake coordinator will check in your child and verify his registration information.

What happens during a brain PET/CT scan?

Obtaining a brain PET/CT scan involves three steps: injection of the radiopharmaceutical, a waiting period, and scanning by the PET/CT machine.

Injection of the radiopharmaceutical:

- You will be greeted by one of our nuclear medicine technologists who will explain the scan in detail to you and your child.

- A tiny amount of the radiopharmaceutical will be injected into one of your child's veins by a small needle.

- Once the radiopharmaceutical reaches the brain, it will transmit signals (gamma rays) that can be detected from outside the body by the PET/CT scanner.

The waiting period:

- After the injection, your child must wait for 30 minutes.

- During this time, while the radiopharmaceutical is circulating within the body, it is extremely important for your child to be very quiet — no talking, reading, or sleeping. These activities can alter the radiopharmaceutical distribution in the brain and affect the image.

- The lights in the room will be dim to help your child relax.

The PET scan:

- You and your child will be taken to the PET/CT suite. You are welcome to sit in the room with your child during imaging.

- Your child will be asked to lie on the imaging table.

- The table will slide into the scanner.

- Your child must remain still while the images are taken.

- The technologist will be watching the procedure through the window and by TV monitor.

- While your child lay within the scanner, a computer will create images of the brain.

Your child will be in the scanner from 15 to 30 minutes.

Will my child feel anything during a brain PET/CT scan?

Your child may experience some discomfort associated with the insertion of the intravenous needle. The needle used for the procedure is small. Once the radiopharmaceutical is injected, the needle is withdrawn and a bandage is placed over the site of the injection. The area where the injection was given may be a little sore.

The area where the injection was given may be a little sore.

The PET/CT scanner does not touch your child, nor will he or she feel anything from the scanner.

Is a brain PET/CT scan safe?

We are committed to ensuring that your child receives the smallest radiation dose needed to obtain the desired result.

- Nuclear medicine has been used on babies and children for more than 40 years with no known adverse effects from the low doses we use.

- The radiopharmaceutical contains a very tiny amount of radioactive molecules, but we believe that the benefit to your child's health outweighs potential radiation risk.

- The camera used to obtain the images does not produce any radiation.

What happens after the brain PET/CT scan?

Once the brain PET/CT scan is complete, the images will be evaluated for quality. If the scan is adequate, your child will be free to leave and resume normal activity.

One of the Boston Children's nuclear medicine physicians will review your child's images and create a report of the findings and diagnosis.

How do I learn the results of the brain PET/CT scan?

The nuclear medicine physician will provide a report to the doctor who ordered your child's brain PET/CT scan. Your child's doctor will then discuss the results with you.

How Boston Children's Hospital approaches a brain PET/CT scan

The Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging program at Boston Children's is committed to providing you with a safe, comfortable, and child-friendly atmosphere with:

- specialized nuclear medicine physicians with expertise in interpreting brain PET/CT scans in children of all ages

- certified nuclear medicine technologists with years of experience imaging children and teens

- Child Life specialists to help families prior to and during exams

- protocols that keep radiation exposure as low as reasonably achievable while assuring high image quality.

Contact us

To schedule an appointment at any of the Department of Radiology’s locations, please call 617-919-SCAN (7226).

Brain PET scan : MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia

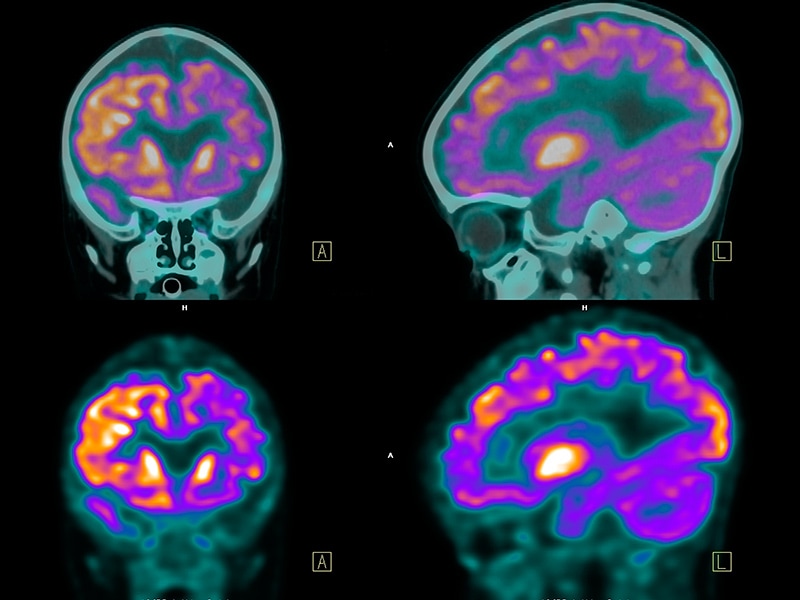

A brain positron emission tomography (PET) scan is an imaging test of the brain. It uses a radioactive substance called a tracer to look for disease or injury in the brain.

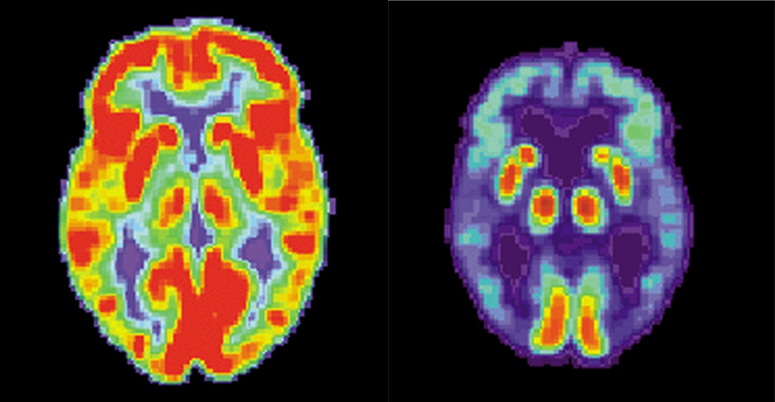

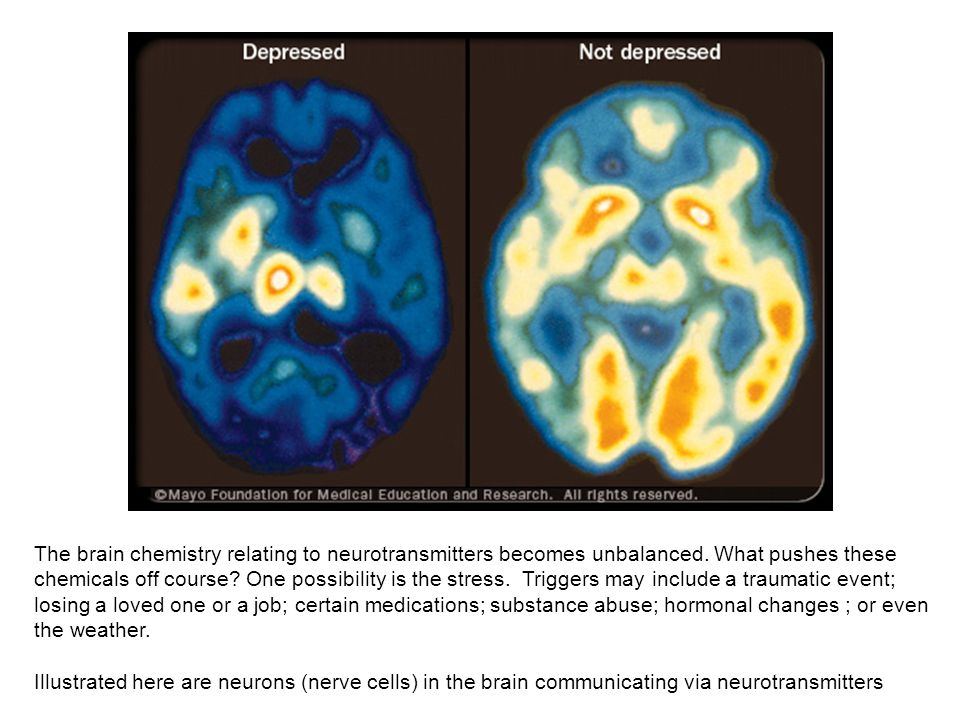

A PET scan shows how the brain and its tissues are working. Other imaging tests, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans only reveal the structure of the brain.

A PET scan requires a small amount of radioactive material (tracer). This tracer is given through a vein (IV), usually on the inside of your elbow. Or, you breathe in the radioactive material as a gas.

The tracer travels through your blood and collects in organs and tissues. The tracer helps your health care provider to see certain areas or diseases more clearly.

You wait nearby as the tracer is absorbed by your body. This usually takes about 1 hour.

Then, you lie on a narrow table, which slides into a large tunnel-shaped scanner. The PET scanner detects signals from the tracer. A computer changes the results into 3-D pictures. The images are displayed on a monitor for your provider to read.

The PET scanner detects signals from the tracer. A computer changes the results into 3-D pictures. The images are displayed on a monitor for your provider to read.

You must lie still during the test so that the machine can produce clear images of your brain. You may be asked to read or name letters if your memory is being tested.

The test takes between 30 minutes and 2 hours.

You may be asked not to eat anything for 4 to 6 hours before the scan. You will be able to drink water.

Tell your provider if:

- You are afraid of close spaces (have claustrophobia). You may be given a medicine to help you feel sleepy and less anxious.

- You are pregnant or think you might be pregnant.

- You have any allergies to injected dye (contrast).

- You have taken insulin for diabetes. You will need special preparation.

Always tell your provider about the medicines you are taking, including those bought without a prescription. Sometimes, medicines interfere with the test results.

You may feel a sharp sting when the needle containing the tracer is placed into your vein.

A PET scan causes no pain. The table may be hard or cold, but you can request a blanket or pillow.

An intercom in the room allows you to speak to someone at any time.

There is no recovery time unless you were given a medicine to relax.

After the test, drink a lot of fluids to flush the tracer out of your body.

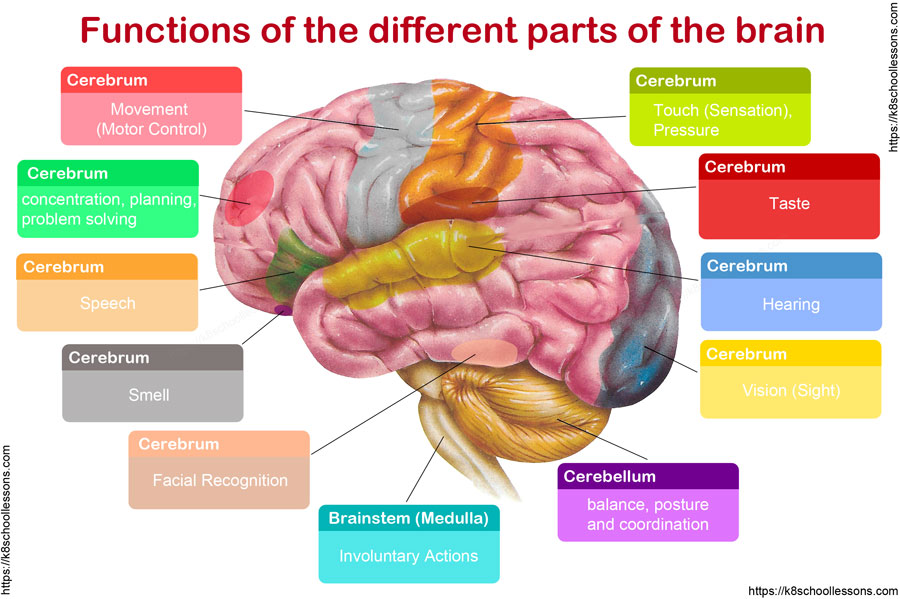

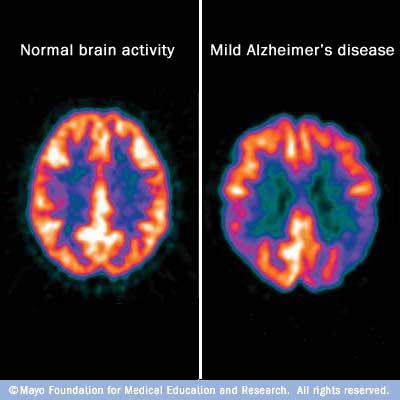

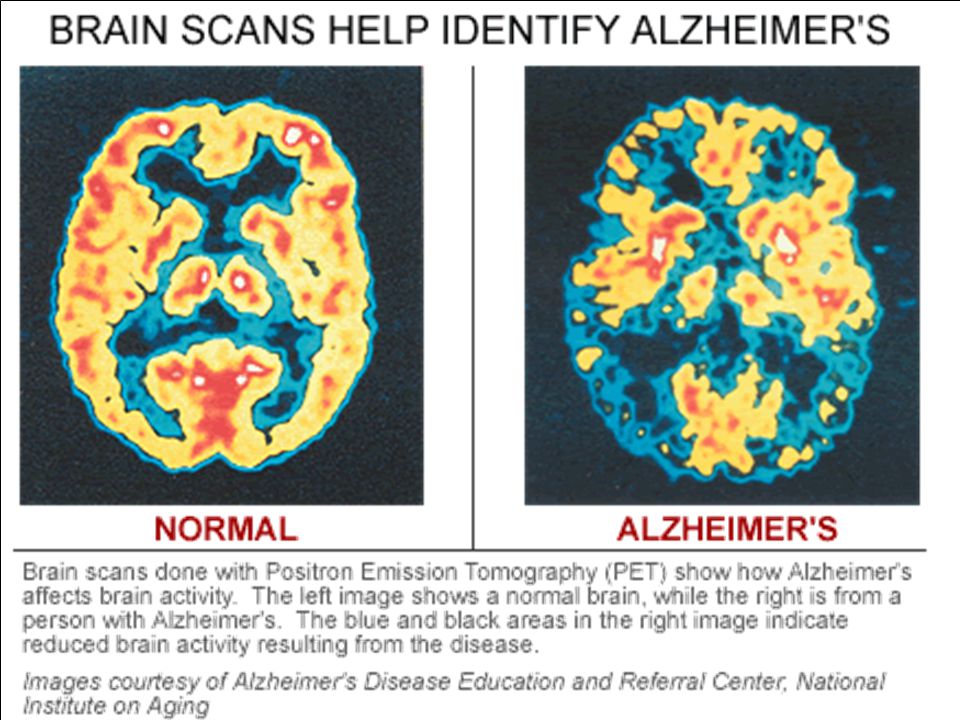

A PET scan can show the size, shape, and function of the brain, so your doctor can make sure it is working as well as it should. It is most often used when other tests, such as MRI scan or CT scan, do not provide enough information.

This test can be used to:

- Diagnose cancer

- Prepare for epilepsy surgery

- Help diagnose dementia if other tests and exams do not provide enough information

- Tell the difference between Parkinson disease and other movement disorders

Several PET scans may be taken to determine how well you are responding to treatment for cancer or another illness.

There are no problems detected in the size, shape, or function of the brain. There are no areas in which the tracer has abnormally collected.

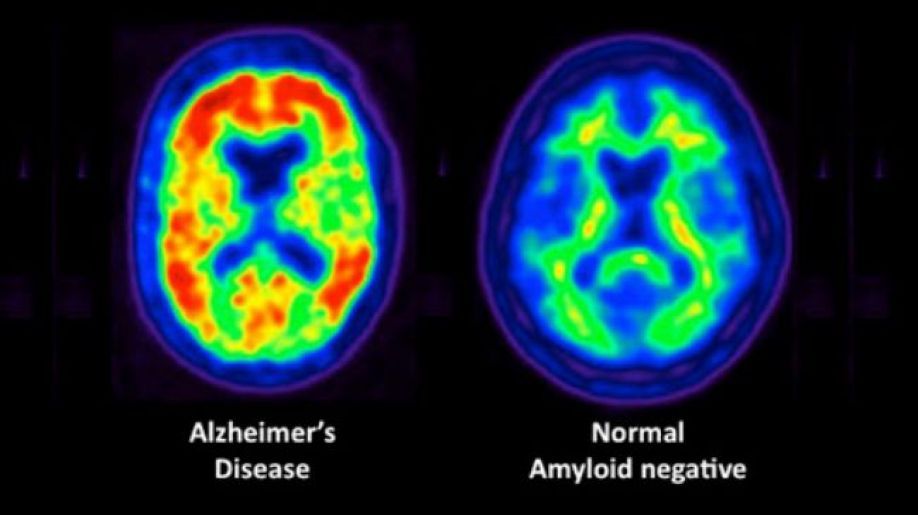

Abnormal results may be due to:

- Alzheimer disease or dementia

- Brain tumor or spread of cancer from another body area to the brain

- Epilepsy, and may identify where the seizures start in your brain

- Movement disorders (such as Parkinson disease)

The amount of radiation used in a PET scan is low. It is about the same amount of radiation as in most CT scans. Also, the radiation does not last for long in your body.

Women who are pregnant or are breastfeeding should let their provider know before having this test. Infants and babies developing in the womb are more sensitive to the effects of radiation because their organs are still growing.

It is possible, though very unlikely, to have an allergic reaction to the radioactive substance. Some people have pain, redness, or swelling at the injection site.

It is possible to have false results on a PET scan. Blood sugar or insulin levels may affect the test results in people with diabetes.

PET scans may be done along with a CT scan. This combination scan is called a PET/CT.

Brain positron emission tomography; PET scan - brain

Chernecky CC, Berger BJ. Positron emission tomography (PET) - diagnostic. In: Chernecky CC, Berger BJ, eds. Laboratory Tests and Diagnostic Procedures. 6th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2013:892-894.

Glaudemans AWJM, Israel O, Slart RHJA, Ben-Haim S. Vascular PET/CT and SPECT/CT. In: Sidawy AN, Perler BA, eds. Rutherford's Vascular Surgery and Endovascular Therapy. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:chap 29.

Hutton BF, Segerman D, Miles KA. Radionuclide and hybrid imaging. In: Adam A, Dixon AK, Gillard JH, Schaefer-Prokop CM, eds. Grainger & Allison's Diagnostic Radiology: A Textbook of Medical Imaging. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2015:chap 6.

Jankovic J, Mazziotta JC, Newman NJ, Pomeroy SL. Investigations in the diagnosis and management of neurological disease. In: Jankovic J, Mazziotta JC, Pomeroy SL, Newman NJ, eds. Bradley and Daroff's Neurology in Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 34.

Updated by: Evelyn O. Berman, MD, Assistant Professor of Neurology and Pediatrics at University of Rochester, Rochester, NY. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.

Dogs understand when spoken to in a foreign language

January 10, 2022 12:53 Olga Muraya

The Border Collie is considered one of the smartest dog breeds.

Pictures

The dogs were specially trained to lie still in the MRI machine.

Photo by Eniko Kubinyi/Eötvös Lorand University.

Researchers in Hungary scanned the brains of domestic dogs and found that not only can they make sense of speech, but they also understand when people are speaking in an unfamiliar language.

Scientists scanned the brains of domestic dogs and proved that human tailed friends can not only understand human speech, but also distinguish between familiar and unfamiliar languages!

This makes them the first animals, after some monkeys, to recognize without prior training when a foreign language is spoken to them.

When the first author of the study, Laura V. Cuaya, moved from Mexico to Hungary to work at the University of Budapest, she brought with her her dog, a border collie named Kun-kun.

Until now, Professor Kuaya had only spoken to Kun-kun in Spanish. Once in a different language environment, the researcher wondered if the dog had noticed that now the people around him were speaking in an unfamiliar Hungarian language.

Recall that even small children who have not yet spoken their first words have an innate "ability for languages". Scientists explain this by the fact that the first words the child hears while in the womb.

Dogs have lived alongside humans for several millennia, and some breeds demonstrate impressive communication skills with humans from birth.

In addition, scientists already know that dogs understand the meaning of certain words. Moreover, the "vocabulary" of some dogs exceeds 200 words - about the same number of words two-year-old children know.

However, scientists have not previously investigated the ability of dogs to recognize different human languages. To study this side of canine intelligence, scientists have developed a special experiment.

For this, Kun-kun and 17 other dogs were trained to lie still in the MRI scanner.

In this way, researchers were able to image the brains of dogs while they were playing excerpts from The Little Prince in Spanish and Hungarian.

Dogs were specially trained to lie still in the MRI machine.

Photo by Eniko Kubinyi/Eötvös Lorand University.

All the dogs in the study heard only one of the two languages from their owners, which allowed the scientists to compare how the animals perceived very familiar and completely unfamiliar words.

The researchers also gave the animals to listen to randomly cut sounds from the same piece. This made it possible to test whether dogs can distinguish coherent speech from nonsense.

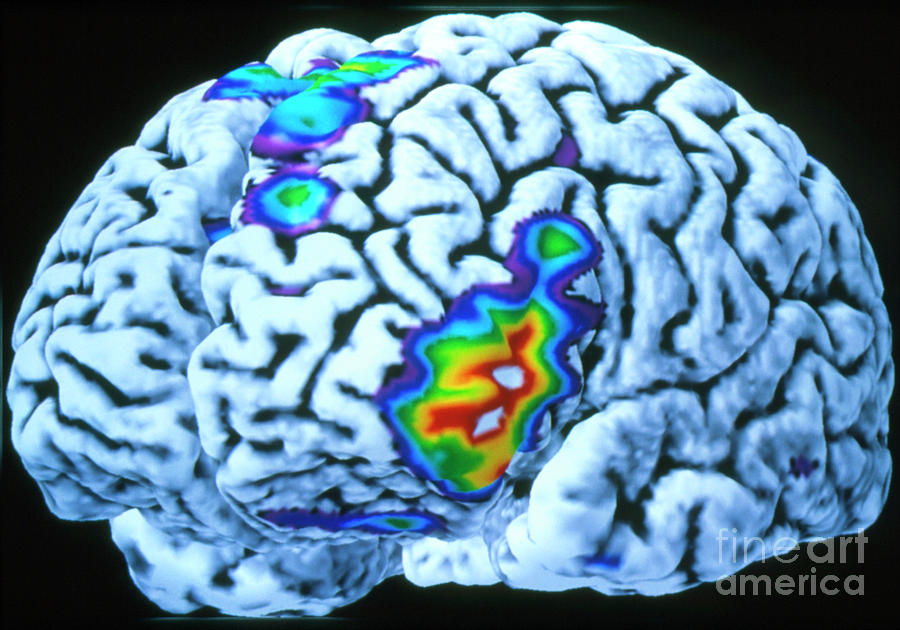

Comparing the brain's neural responses to speech and non-speech signals, the researchers found different patterns of activity in the primary auditory cortex of dogs.

This difference was observed regardless of whether the stimuli came from a familiar or unfamiliar language. However, the researchers found no evidence that dog brain neurons in any way preferred speech to nonsense.

"The dog's brain, like the human brain, can distinguish between speech and non-speech. But the mechanism underlying this ability to recognize speech may differ from speech sensitivity in humans: while the human brain is specifically "tuned" for speech, the dog's brain may just recognize the naturalness of the sound," explains study co-author Raúl Hernández-Pérez of the University of Budapest.

In addition, scientists have concluded that the brain of dogs can also distinguish between Spanish and Hungarian.

Language-specific patterns of activity have been found in another area of the brain, the secondary auditory cortex.

Interestingly, the older the dog was, the better his brain distinguished between familiar and unfamiliar language.

This is an exciting result: it shows that the ability to recognize different languages is not exclusively human.

However, scientists do not yet know if this ability is some kind of canine "talent" or if other species of animals that are not related to humans also have it.

Indeed, it is possible that the brain changes that have taken place over tens of thousands of years of coexistence between dogs and humans have led to the fact that man's friends have acquired some kind of exceptional "ability for languages."

But this is not necessarily the case. Scientists have yet to find out in their future research.

"And if you're wondering how Kun-kun is doing after moving to Budapest: he lives as happily as he lived in Mexico City - he saw snow for the first time and loves to swim in the Danube. We hope that he and his friends will continue to help us uncover evolution speech perception," shared Prof. Kuaya.

The study was published on December 12, 2021 in the scientific journal NeuroImage.

More news from the world of science can be found in the "Science" section of the "Looking" media platform.

science animals brain speech languages dogs MRI society news

Previously related

-

Why do some dogs howl to wolves in response, while others do not

-

What Bats, Death Metalists, and Throat Singers Have in Common

-

What helps cats get along under the same roof

-

Wild horses found a complex social system

-

Vampires love to drink blood in the company of friends

-

Monkeys invented the etiquette of polite communication between themselves

The dog's brain did not distinguish the back of the head from the face

Scientists from Hungary and Mexico found that the visual cortex of the canine brain cannot distinguish the back of the head from the face of both people and other dogs. To do this, they conducted an fMRI study on 20 dogs and 30 human volunteers: while the canine visual cortex could recognize other dogs and distinguish them from humans, facial recognition-specific activity was observed only in the human visual cortex. Article published at The Journal of Neuroscience .

To do this, they conducted an fMRI study on 20 dogs and 30 human volunteers: while the canine visual cortex could recognize other dogs and distinguish them from humans, facial recognition-specific activity was observed only in the human visual cortex. Article published at The Journal of Neuroscience .

Many types of domestic animals are able to recognize a person - this, apparently, was facilitated by a long process of domestication and cohabitation. It is interesting that some animals, like humans, use their eyesight for this: for example, sheep can recognize individual people, pigs are able to distinguish the face from the back of the head, but goats prefer a happy face to a sad person (horses can also recognize and remember human emotions).

At the same time, it is clear that the recognition of the face of a person and the faces of relatives in animals should differ - including at the level of the brain. Scientists led by Attila Andics from the University of Budapest and his colleagues decided to study this using the example of domestic dogs. Together with Mexican colleagues, they conducted two separate fMRI experiments: one with 20 dogs living with humans and one with 30 healthy people. All dogs had previously taken part in similar studies and were trained to sit still in the scanner - without the use of sedatives or restraint straps.

Together with Mexican colleagues, they conducted two separate fMRI experiments: one with 20 dogs living with humans and one with 30 healthy people. All dogs had previously taken part in similar studies and were trained to sit still in the scanner - without the use of sedatives or restraint straps.

The task for humans and dogs was the same: during scanning, participants had to look at clips of faces and heads of unfamiliar people and dogs. The resulting activity of the occipital lobes (they contain the visual cortex) was then compared voxel-wise with each other depending on the condition: for example, the activity of the brain of people when viewing the back of the head was compared with the activity obtained when observing the face, and the same activity was then compared in dogs .

Unlike the human brain, which could distinguish the face from the back of the head, and the dog from the human, the brain of dogs could only distinguish one species from another. At the sight of relatives, the activity of the middle suprasylvian gyrus in their visual cortex was significantly higher than at the sight of humans (p < 0.