Childhood depression is likely to persist because

Childhood Depression | Anxiety and Depression

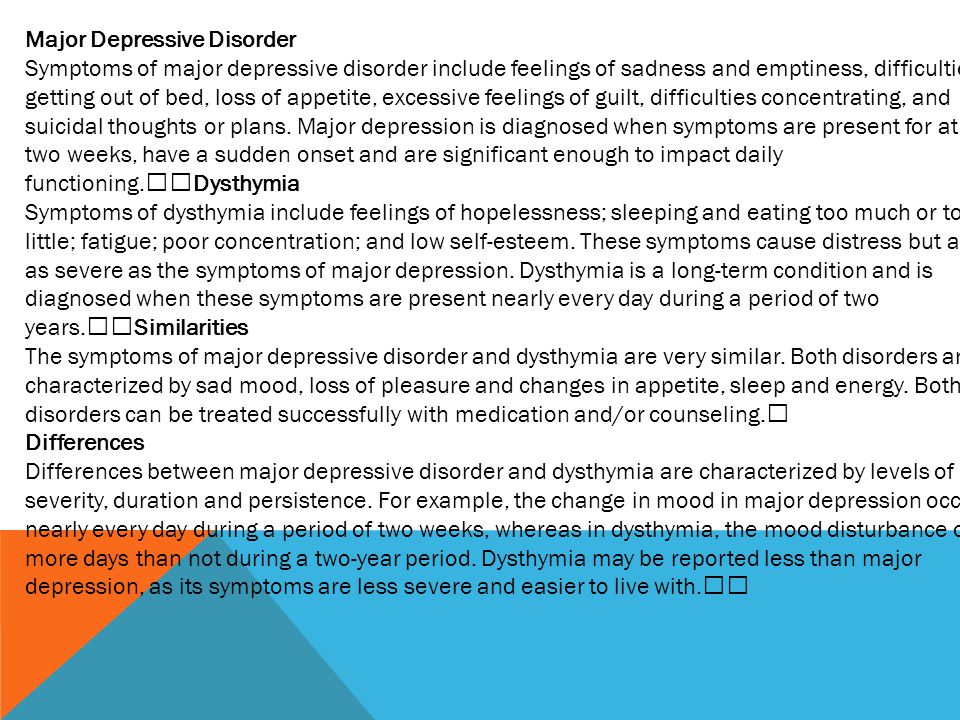

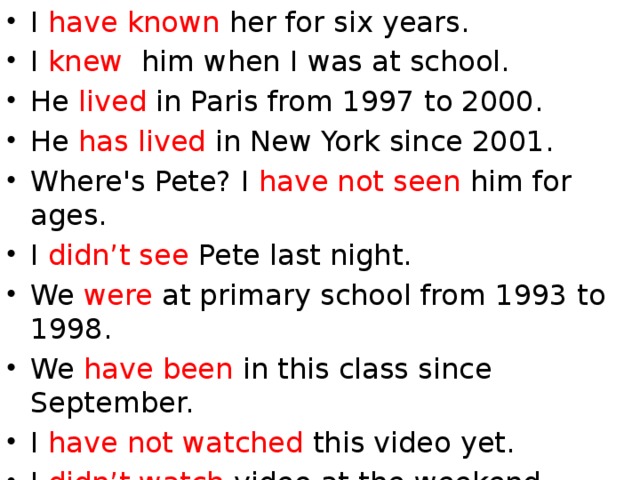

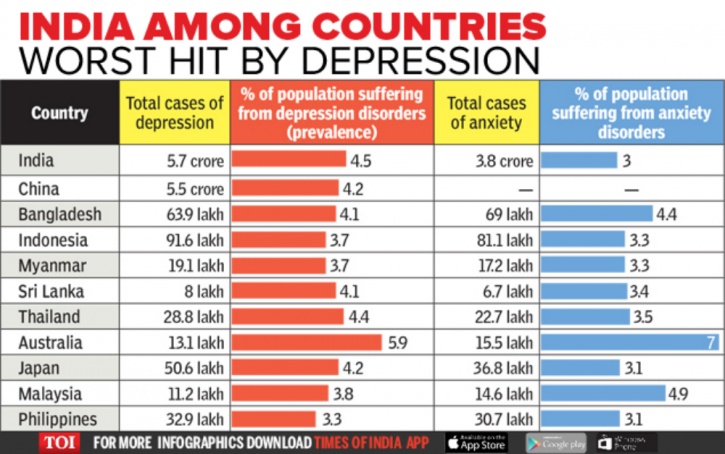

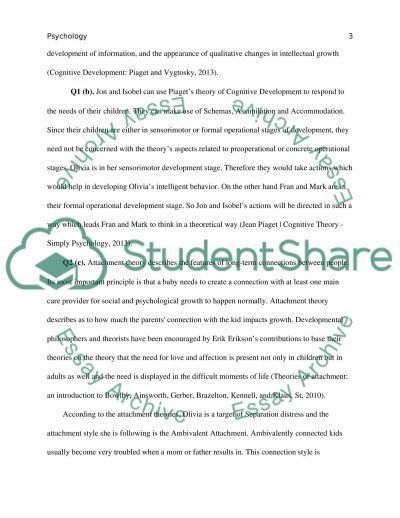

Rates of childhood depression have been rising in the last several years. Yet, information and awareness about childhood depression has not caught on at the same rate. Millions of people across the world wonder and doubt if children can get depressed. Many well-intentioned adults still believe that children ‘can’t get depressed. They are so young- what do they have to be depressed about? When we were that age, we were just happy’. Alongside misunderstanding is stigma and the idea that mental illness is a taboo subject.

What we now know:

- Childhood depression is a real, distinct clinical entity.

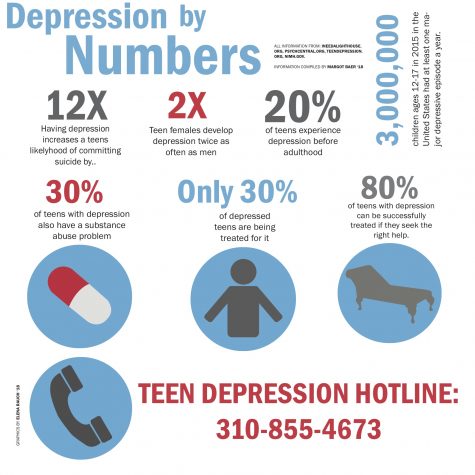

- It is a serious health condition, which if left untreated, increases risk of future, prolonged and more severe depressive episodes. Untreated depression in childhood and adolescence can pose risk of suicide.

- Depression often has biological, psychological and social underpinnings. An individualized treatment plan that explores and addresses each of these aspects, works best.

- Effective treatment options for childhood and teen depression have been widely tested, proven and established, through several scientific studies over the years.

- Childhood depression can be hidden and therefore, easily missed. Timely recognition and treatment can be life-changing and life-saving.

- The barriers surrounding mental health stigma are beginning to give way due to powerful social movements and discussions that address realities of mental health.

Who is Affected by Depression in Childhood or Teenage?

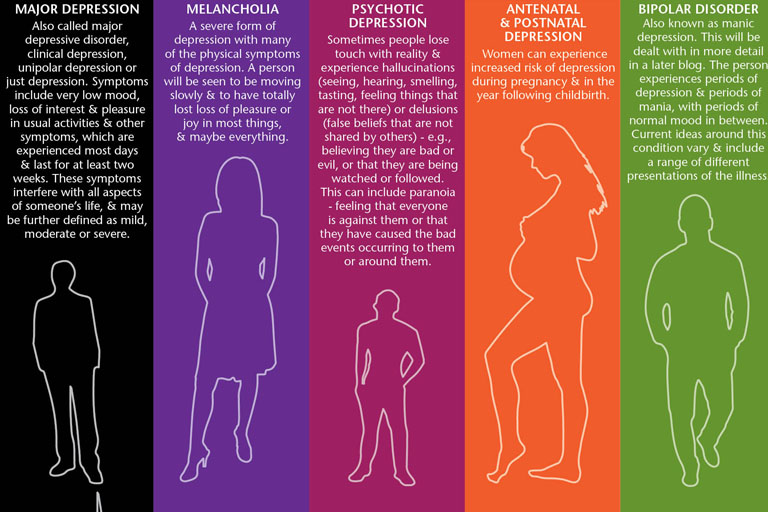

Depression can affect anyone. However, children or teens who have immediate family members with a history of depression or other mood disorders (such as bipolar disorder) are more likely to suffer from depression, often due to a genetic predisposition. Predisposition implies greater likelihood; it does not mean that the child or teen will necessarily experience depression.

Children with chronic or severe medical conditions are at a greater risk of suffering from depression.

Common Signs of Depression in Childhood or Adolescence

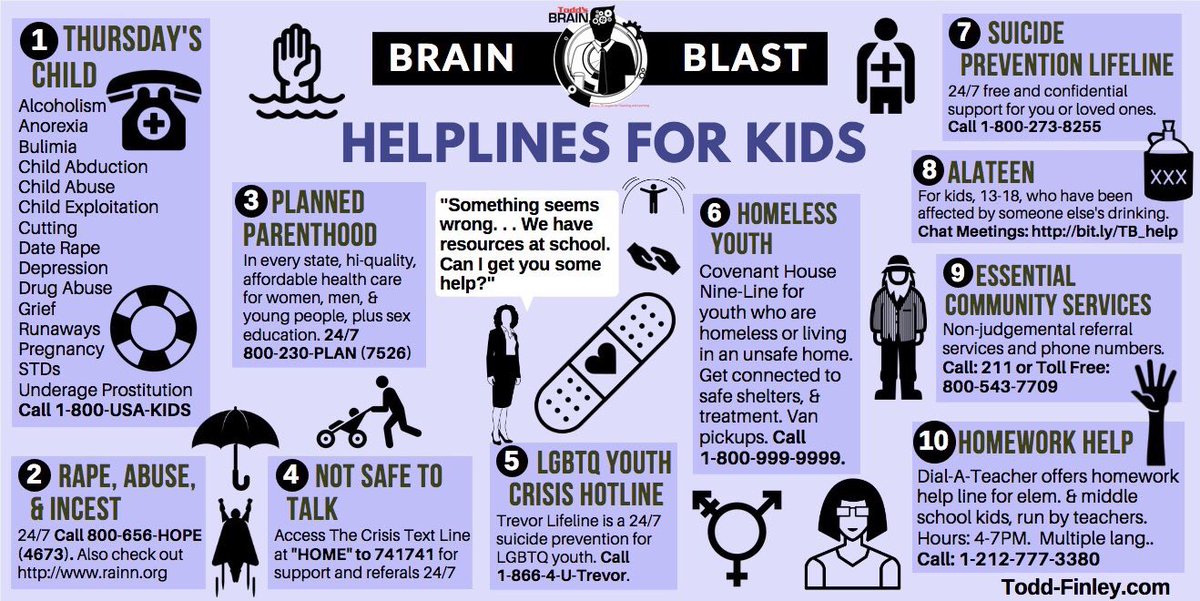

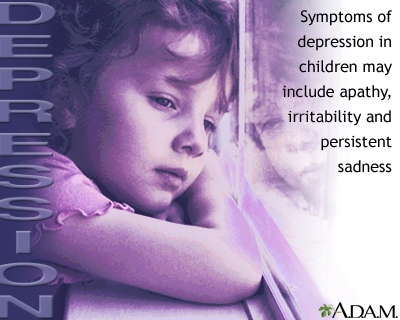

Depression in childhood/adolescence can manifest somewhat differently than it does in adults. Irritability and/or anger are more common signs of depression in children and teens.

When depressed, younger children are more likely to have physical or bodily symptoms, such as aches or pains, restlessness, distress during separation from parents, as they may not have the emotional attunement and/or expressive abilities to talk about their emotions.

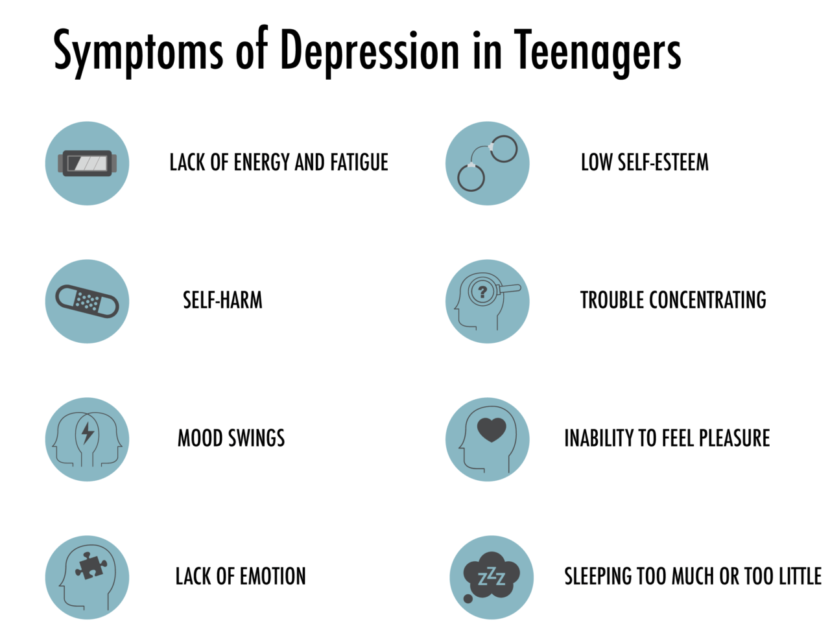

Other signs of depression in children and teens, can be:

- Loss of interest in usual fun activities

- Withdrawal from social or usual pleasurable activities

- Difficulties with concentration

- Running away from home or talking about running away from home

- Talking about death or dying, giving away (or talking about giving away) favorite possessions, writing goodbye letters

- Sleep increase (or decrease)

- Appetite/weight changes (more likely an increase, in depressed teens)

- Occasionally, new or recent onset agitation or aggression

- Comments indicating hopelessness or low self-worth

Not all of the above-mentioned symptoms have to be present for a diagnosis of depression. Symptoms usually occur on most days, for at least 2 weeks, in order to meet criteria for depression. When seeing a professional to explore a diagnosis, you can utilize online health resources to prepare meaningful questions to ask a doctor in order to facilitate productive conversation for treatment.

Symptoms usually occur on most days, for at least 2 weeks, in order to meet criteria for depression. When seeing a professional to explore a diagnosis, you can utilize online health resources to prepare meaningful questions to ask a doctor in order to facilitate productive conversation for treatment.

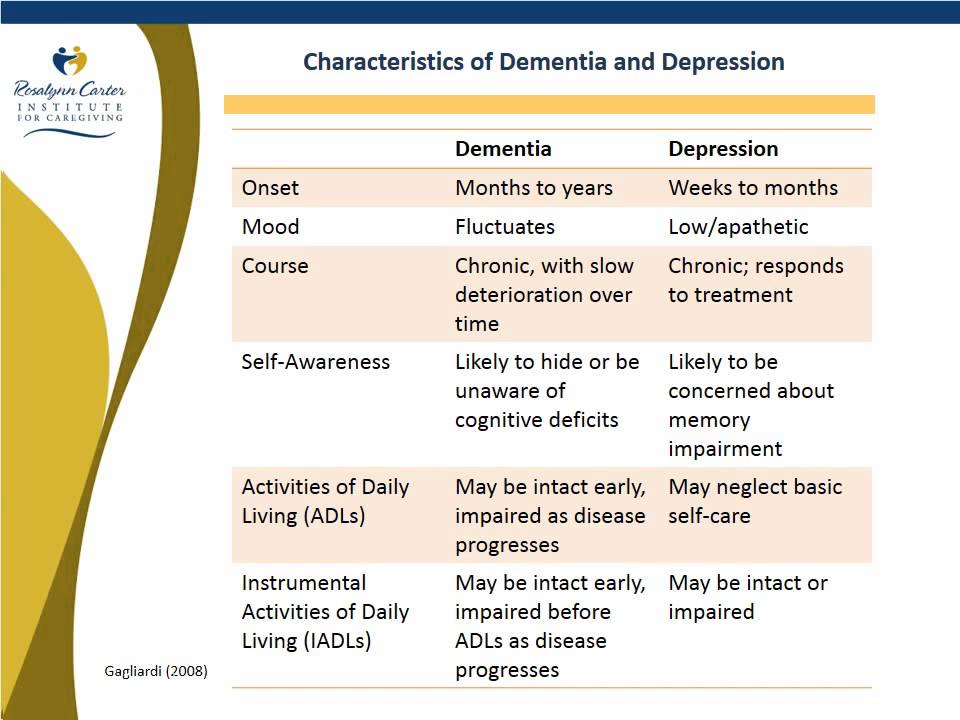

Ruling Out Medical Conditions First

Psychiatric disorders are diagnosis of exclusion, which means that only if the symptoms are unexplained by medical conditions, or effect of substances or other non-psychiatric causes, would the cause of symptoms be deemed to be due to a primary psychiatric disorder.

Before arriving to the diagnosis of depression, a child or teen who is suspected to be depressed, must undergo a comprehensive medical evaluation to rule out any underlying medical condition which could be manifesting as or resulting in depression. For example, hypothyroidism (depressive symptoms, weight gain, low energy, cognitive difficulties, constipation). Even conditions such as undiagnosed anemia can mimic depression, due to accompanying fatigue/low energy. Vitamin D deficiency, common in cold climates, increases risk of depressive symptoms and fatigue. The good news is that these conditions have effective treatments, and treatment of the underlying medical condition in a timely manner should resolve depressive symptoms.

Even conditions such as undiagnosed anemia can mimic depression, due to accompanying fatigue/low energy. Vitamin D deficiency, common in cold climates, increases risk of depressive symptoms and fatigue. The good news is that these conditions have effective treatments, and treatment of the underlying medical condition in a timely manner should resolve depressive symptoms.

Ruling Out Other Psychiatric Conditions

Rule out undiagnosed/untreated ADHD (attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder), anxiety disorders or other psychiatric conditions, which when left untreated, can result in depressive symptoms due to the impairment in functioning from ADHD or anxiety disorder itself.

Treatment

Why Treat?

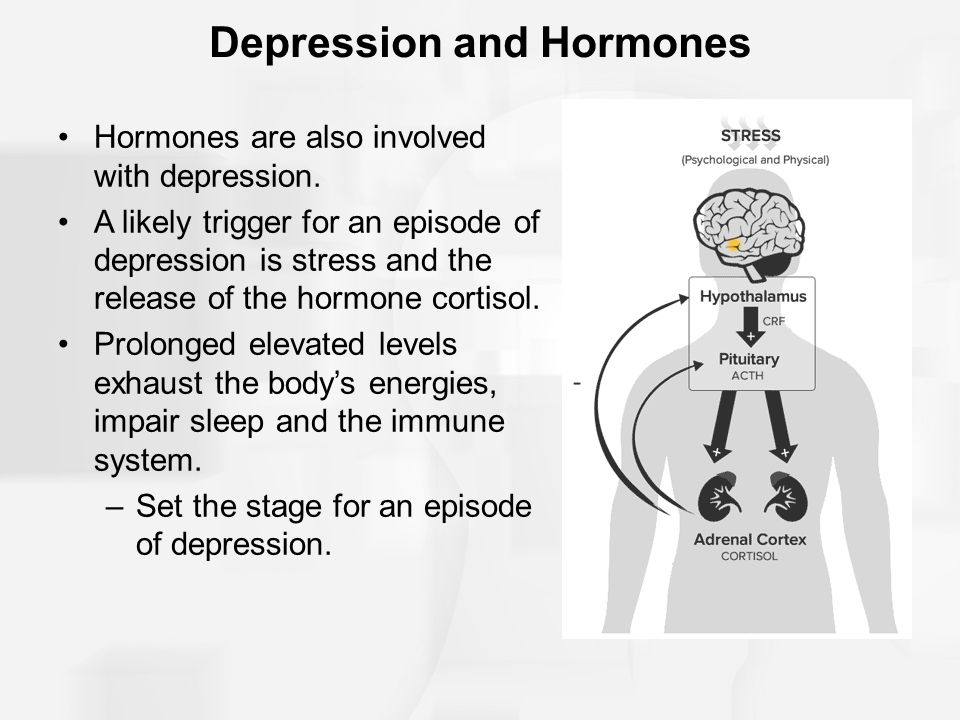

Depression is associated with visible brain changes seen on functional brain MRI studies of depressed individuals. Treatment, for example, psychotherapy has been shown to confer long term benefit and neural changes in the brain.

How Do I know My Child Needs Treatment?

In addition to an overall assessment, your child’s pediatrician may administer rating scales and other forms of assessment to determine the degree of depression and may refer you to a psychiatrist or a psychotherapist.

We know a child/teen needs treatment for depression when their school, social, and/or home functioning is significantly affected by depressive symptoms, on a frequent basis.

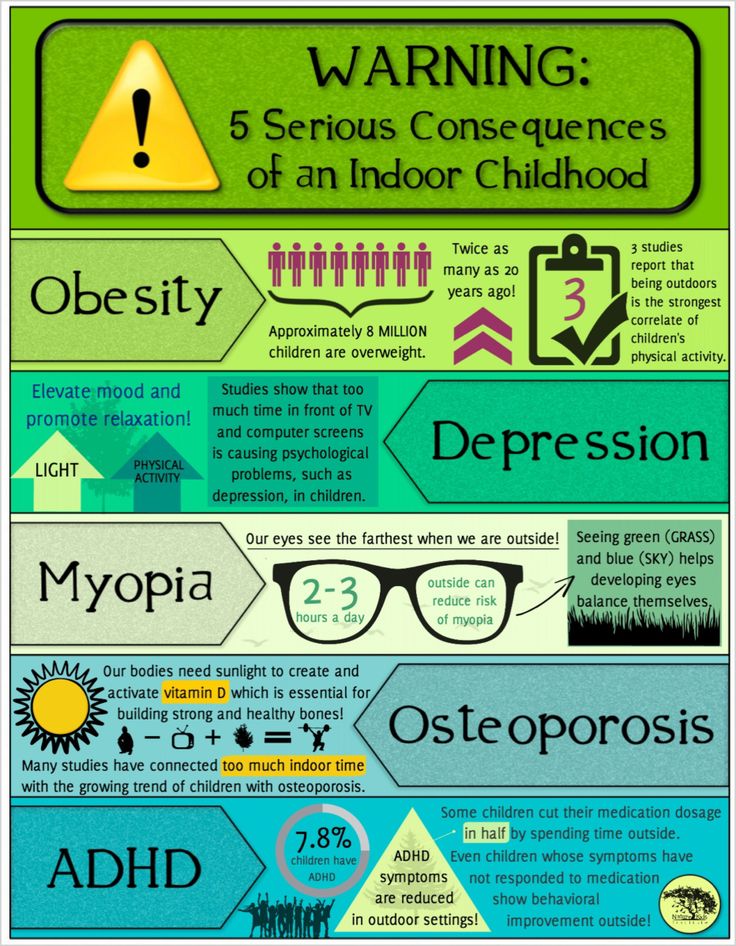

If your child/teen is feeling suicidal and/or having thoughts/urges to hurt themselves, call 911 or take your child/teen to the nearest ER.

What Kind of Treatment?

For mild to moderate depression, CBT (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy) is the typical first-line treatment of choice for children and teens. There can be exceptions to this, depending on the specific clinical condition, age and circumstance of the child. For children younger than 10, other modalities of psychotherapy such as play therapy, psychodynamic psychotherapy, and behavior therapy may be utilized.

For moderate to severe depression, evidence-based guidelines recommend a combination of CBT and antidepressant medications (typically SSRI medications, also known as Selective Serotonin Re-Uptake Inhibitors).

SSRI Use for Depression in Children

- SSRIs and other antidepressants have a black box warning from FDA about risk of increase in suicidal thoughts and behavior with use, particularly in the early phase of treatment. Studies did not show completed suicides.

- After this warning came out in 2004, antidepressant prescription rates dropped, and suicide rates climbed up.

- Close monitoring during dose initiation, titration and dose changes helps to reduce this risk

- Antidepressant medication use in children and adolescents is preceded by a weighing of benefits and risks of use versus risks of untreated depression.

- Fluoxetine and Escitalopram are FDA approved for treatment of depression in children and teens.

- Studies involving paroxetine (another SSRI) have shown a higher profile of side effects with its use in children, and therefore, may not be recommended for children and teens.

- Studies show a higher likelihood of an individual responding to an SSRI that an immediate family member benefitted from (however, this is a likelihood, not necessary that it will happen in each situation)

If depressive symptoms are secondary to other conditions, such as untreated ADHD or anxiety disorders, adequate treatment of those disorders is essential and will usually resolve the depressive symptoms. However, in certain situations, specific antidepressant medications and/or psychotherapy targeted towards depression may be needed in addition. One might note that if trials of two or more antidepressants are not effective, or if a child/teen is sensitive to medications in general, there are additional avenues that can be explored. One plausible route for consideration is genetic testing that combines personal genetic data with medication information to achieve the desired remedy.

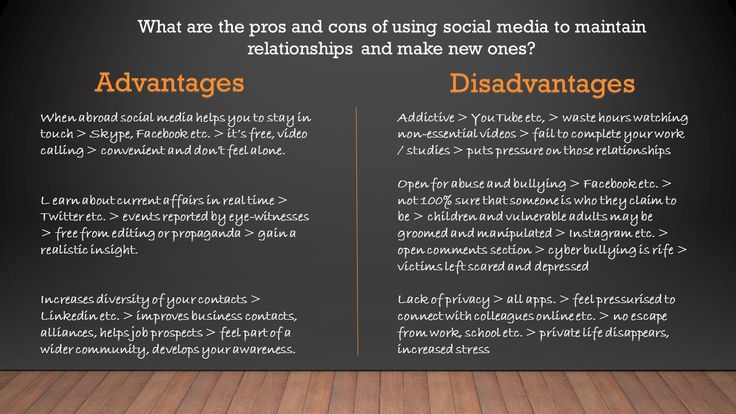

Your child’s pediatrician/psychiatrist, therapist, together with you, may also explore for any bullying, trauma, and will try to understand your child/teen’s inner life and look further for any school, social, family or other stressors that may be contributing to, or exacerbating/perpetuating the depressive condition. If family stressors are significantly contributing to your child’s depression, your doctor may recommend family therapy in addition. With your permission, the doctor/therapist may coordinate with your child’s school to share recommendations to optimize your child’s school functioning and emotional well-being at school.

Overcoming Mental Health Stigma

In 1999 the United States Surgeon General labeled stigma as quite possibly the biggest barrier to mental health care. Stigma manifests as misguided stereotypes and negative attitudes or beliefs towards those with mental illness. Research shows that stigma and embarrassment were the top reasons why people with mental illness did not engage in medication adherence, such as self-care, therapy and medication compliance. As of late, there has been an increase in available resources and tools to overcome stigma for children and teens, as well as their caregivers. Allies such as Bring Change to Mind, an organization focused on encouraging dialogue about mental health, as well as raising awareness through education, offers high-school and college programs that foster a culture of peer support within schools.

As of late, there has been an increase in available resources and tools to overcome stigma for children and teens, as well as their caregivers. Allies such as Bring Change to Mind, an organization focused on encouraging dialogue about mental health, as well as raising awareness through education, offers high-school and college programs that foster a culture of peer support within schools.

A Word About Substance Use and Depression

Sadly, substance use among teens is becoming rampant across the country, even in reputed school districts, and thus, needs to be addressed when exploring and treating depression.

Marijuana use is particularly common among teens. Marijuana is considered to be a ‘gateway drug’ and can lead to ‘amotivational syndrome’. This syndrome manifests as low motivation to do things, and in conjunction with marijuana related ‘munchies’ can mimic a primary depressive disorder. In many cases, a teen may be ‘self-medicating’ for untreated or undiagnosed depressive or anxiety symptoms through substance use. Use or withdrawal from other substances can cause depressive, mood symptoms as well.

Use or withdrawal from other substances can cause depressive, mood symptoms as well.

Proper and timely treatment can be very effective in resolving depressive symptoms and in reducing risk of relapse. Please consult your child’s pediatrician or health care provider if you suspect your child/teen may be suffering from a medical or a psychiatric condition.

Note: This article is for informational purposes only and is not intended to provide medical or psychiatric advice or recommendations, or diagnostic or treatment opinion. This is not a complete review or description of this subject. If you suspect a medical or psychiatric condition, please consult a health care provider. All decisions regarding an individual’s care must be made in consultation with your healthcare provider, considering the individuals’ unique condition. If you or someone you know is struggling, please contact the 24x7, confidential National Hotline at 1-800-273-8255 or use the crisis text line by texting HOME to 741741 in the US, or go to http://www. suicide.org/international-suicide-hotlines.html for the suicide hotline number for your country.

suicide.org/international-suicide-hotlines.html for the suicide hotline number for your country.

Behavioural and emotional disorders in childhood: A brief overview for paediatricians

1. Parry TS. Assessment of developmental learning and behavioural problems in children and young people. Med J Aust. 2005;183:43–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Hong JS, Tillman R, Luby JL. Disruptive behavior in preschool children: distinguishing normal misbehavior from markers of current and later childhood conduct disorder. J Pediatr. 2015;166:723–730.e1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Wakschlag LS, Choi SW, Carter AS, Hullsiek H, Burns J, McCarthy K, Leibenluft E, Briggs-Gowan MJ. Defining the developmental parameters of temper loss in early childhood: implications for developmental psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012;53:1099–1108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Bagner DM, Rodríguez GM, Blake CA, Linares D, Carter AS. Assessment of behavioral and emotional problems in infancy: a systematic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2012;15:113–128. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2012;15:113–128. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. El-Radhi AS. Management of common behaviour and mental health problems. Br J Nurs. 2015;24:586, 588–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Gardner F, Shaw DS. 2009. Behavioral Problems of Infancy and Preschool Children (0–5). Chapter 53 in Rutter’s Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Fifth Edition. [Google Scholar]

7. Lu Y, Mak KK, van Bever HP, Ng TP, Mak A, Ho RC. Prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in adolescents with asthma: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2012;23:707–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Chernyshov PV, Ho RC, Monti F, Jirakova A, Velitchko SS, Hercogova J, Neri E. Gender Differences in Self-assessed Health-related Quality of Life in Children with Atopic Dermatitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9:19–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

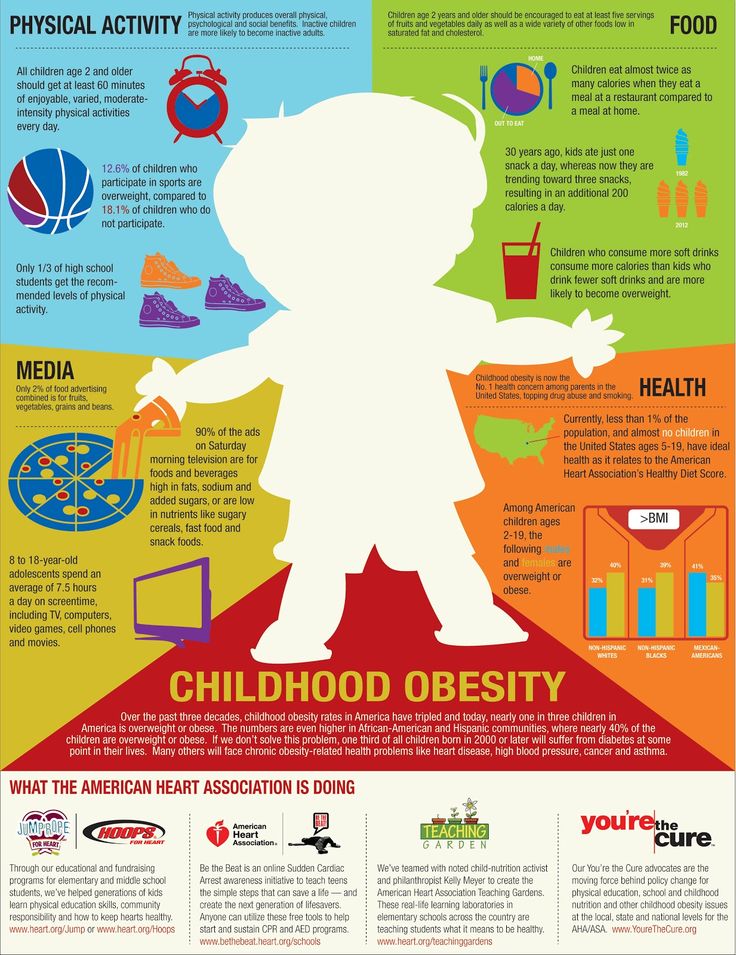

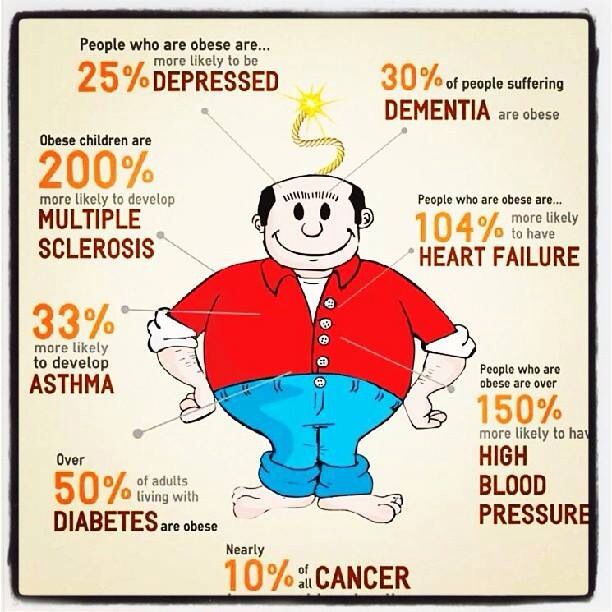

9. Quek YH, Tam WWS, Zhang MWB, Ho RCM. Exploring the association between childhood and adolescent obesity and depression: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2017;18:742–754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Obes Rev. 2017;18:742–754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Kolko DJ, Perrin E. The integration of behavioral health interventions in children’s health care: services, science, and suggestions. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2014;43:216–228. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) A Guide to Building Collaborative Mental Health Care Partnerships. In: Pediatric Primary Care; 2010. pp. 1–27. Available from: https://www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/docs/clinical_practice_center/guide_to_building_collaborative_mental_health_care_partnerships.pdf. [Google Scholar]

12. American Psychiatric Association (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Edition. Washington (DC): APA; 2013. Available from: https://tinyurl.com/y82f6kyj. [Google Scholar]

13. World Health Organization (WHO) International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10) Geneva Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1990. Available from: https://tinyurl.com/neayazp.

Available from: https://tinyurl.com/neayazp.

14. Emerson E. Cambridge University Press; 2001. Challenging Behaviour: Analysis and intervention in people with learning disabilities. 2nd edition; pp. 2–4. [Google Scholar]

15. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) Challenging behaviour and learning disabilities: Prevention and interventions for people with learning disabilities whose behaviour challenges. 2015. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng11.

16. Langridge D. 2007. Health and Challenging Behaviour information sheet. The Challenging Behaviour Foundation. Available from: http://www.challengingbehaviour.org.uk/learning-disability-files/14_WHealth-and-Challenging-Behaviour.pdf. [Google Scholar]

17. Tremblay RE, Nagin DS, Séguin JR, Zoccolillo M, Zelazo PD, Boivin M, Pérusse D, Japel C. Physical aggression during early childhood: trajectories and predictors. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e43–e50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Reebye P. Aggression during early years - infancy and preschool. Can Child Adolesc Psychiatr Rev. 2005;14:16–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Reebye P. Aggression during early years - infancy and preschool. Can Child Adolesc Psychiatr Rev. 2005;14:16–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Gurnani T, Ivanov I, Newcorn JH. Pharmacotherapy of Aggression in Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016;26:65–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Bolhuis K, Lubke GH, van der Ende J, Bartels M, van Beijsterveldt CEM, Lichtenstein P, Larsson H, Jaddoe VWV, Kushner SA, Verhulst FC, et al. Disentangling Heterogeneity of Childhood Disruptive Behavior Problems Into Dimensions and Subgroups. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56:678–686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management. [updated 2008 Sept 24] Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg72.

22. Campbell SB, Shaw DS, Gilliom M. Early externalizing behavior problems: toddlers and preschoolers at risk for later maladjustment. Dev Psychopathol. 2000;12:467–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dev Psychopathol. 2000;12:467–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Dretzke J, Frew E, Davenport C, Barlow J, Stewart-Brown S, Sandercock J, Bayliss S, Raftery J, Hyde C, Taylor R. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of parent training/education programmes for the treatment of conduct disorder, including oppositional defiant disorder, in children. Health Technol Assess. 2005;9:iii, ix–ix, 1-233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Perou RH, Bitsko SJ, Blumberg P, Pastor RM, Ghandour JC, Gfoerer SL. Mental Health Surveillance among Children - United States 2005-2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 2013;62(Suppl 2):1–35. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/other/su6202.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. State of Victoria Australia Better Health Channel. Suppl 2. 2014. Conduct Disorder. Available from: https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/conduct-disorder. [Google Scholar]

26. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Conduct Disorder. 2103c. Available from: http://www.rpsych.com/docs/Conduct_Disorder.pdf.

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) Conduct Disorder. 2103c. Available from: http://www.rpsych.com/docs/Conduct_Disorder.pdf.

27. Nock MK, Kazdin AE, Hiripi E, Kessler RC. Lifetime prevalence, correlates, and persistence of oppositional defiant disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48:703–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Bradley MC, Mandell D. Oppositional defiant disorder: a systematic review of evidence of intervention effectiveness. J Exp Criminol. 2005;1:343–365. [Google Scholar]

29. Ramsawh HJ, Chavira DA, Stein MB. Burden of anxiety disorders in pediatric medical settings: prevalence, phenomenology, and a research agenda. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:965–972. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) The Anxious Child. 2013b. Available from: https://www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/docs/facts_for_families/47_the_anxious_child. pdf.

pdf.

31. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) 2013. The Depressed Child. Available from: https://www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/docs/facts_for_families/04_the_depressed_child.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Stringaris A. Irritability in children and adolescents: a challenge for DSM-5. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20:61–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. American Psychiatric Association (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th Edition. Washington (DC): APA; 2000. p. 866. [Google Scholar]

34. McPartland J, Volkmar FR. Autism and related disorders. Handb Clin Neurol. 2012;106:407–418. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Huerta M, Bishop SL, Duncan A, Hus V, Lord C. Application of DSM-5 criteria for autism spectrum disorder to three samples of children with DSM-IV diagnoses of pervasive developmental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:1056–1064. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Kim YS, Fombonne E, Koh YJ, Kim SJ, Cheon KA, Leventhal BL. A comparison of DSM-IV pervasive developmental disorder and DSM-5 autism spectrum disorder prevalence in an epidemiologic sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53:500–508. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kim YS, Fombonne E, Koh YJ, Kim SJ, Cheon KA, Leventhal BL. A comparison of DSM-IV pervasive developmental disorder and DSM-5 autism spectrum disorder prevalence in an epidemiologic sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53:500–508. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Kulage KM, Smaldone AM, Cohn EG. How will DSM-5 affect autism diagnosis? A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44:1918–1932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Maggin DM, Johnson AH, Chafouleas SM, Ruberto LM, Berggren M. A systematic evidence review of school-based group contingency interventions for students with challenging behavior. J Sch Psychol. 2012;50:625–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Iacono T, Trembath D, Erickson S. The role of augmentative and alternative communication for children with autism: current status and future trends. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:2349–2361. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) Autism (Practice Portal) Available from: http://www. asha.org/Practice-Portal/Clinical-Topics/Autism/

asha.org/Practice-Portal/Clinical-Topics/Autism/

41. Reisinger LM, Cornish KM, Fombonne E. Diagnostic differentiation of autism spectrum disorders and pragmatic language impairment. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41:1694–1704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Miller M, Young GS, Hutman T, Johnson S, Schwichtenberg AJ, Ozonoff S. Early pragmatic language difficulties in siblings of children with autism: implications for DSM-5 social communication disorder? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56:774–781. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Rapin I. Historical data. In Rapin I (Ed) Vol. 139. Preschool Children with Inadequate Communication: Developmental Language Disorder, Autism, Low IQ. Clinics in Developmental Medicine. Cambridge University Press, New York; 1996. pp. 57–97. [Google Scholar]

44. Norbury CF. Practitioner review: Social (pragmatic) communication disorder conceptualization, evidence and clinical implications. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;55:204–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Adams C, Lockton E, Freed J, Gaile J, Earl G, McBean K, Nash M, Green J, Vail A, Law J. The Social Communication Intervention Project: a randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of speech and language therapy for school-age children who have pragmatic and social communication problems with or without autism spectrum disorder. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2012;47:233–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Newson E, Le Maréchal K, David C. Pathological demand avoidance syndrome: a necessary distinction within the pervasive developmental disorders. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:595–600. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. O’Nions E, Viding E, Greven CU, Ronald A, Happé F. Pathological demand avoidance: exploring the behavioural profile. Autism. 2014;18:538–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. O’Nions E, Christie P, Gould J, Viding E, Happé F. Development of the ‘Extreme Demand Avoidance Questionnaire’ (EDA-Q): preliminary observations on a trait measure for Pathological Demand Avoidance. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;55:758–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;55:758–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. National Research Council/ Institute of Medicine (NHRC/IOM) Adolescent Health Services: Highlights and Considerations for State Health Policymakers, 2009: 1-25. Available from: http://www.nashp.org/sites/default/files/AdolHealth.pdf.

50. World Health Organization (WHO) Mental health: new understanding new hope [report] Geneva (CH): WHO, 2001. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/2001/en/whr01_en.pdf?ua=1.

51. Green H, McGinnity A, Meltzer H, Ford T, Goodman R. Mental health of children and young people in Great Britain 2004. NY: Palgrave Macmillan; 2005. Available from: http://content.digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB06116/ment-heal-chil-youn-peop-gb-2004-rep1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

52. Copeland WE, Angold A, Costello EJ, Egger H. Prevalence, comorbidity, and correlates of DSM-5 proposed disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:173–179. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Boden JM, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Risk factors for conduct disorder and oppositional/defiant disorder: evidence from a New Zealand birth cohort. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:1125–1133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Boden JM, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Risk factors for conduct disorder and oppositional/defiant disorder: evidence from a New Zealand birth cohort. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:1125–1133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Plant DT, Barker ED, Waters CS, Pawlby S, Pariante CM. Intergenerational transmission of maltreatment and psychopathology: the role of antenatal depression. Psychol Med. 2013;43:519–528. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Murray J, Burgess S, Zuccolo L, Hickman M, Gray R, Lewis SJ. Moderate alcohol drinking in pregnancy increases risk for children’s persistent conduct problems: causal effects in a Mendelian randomisation study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2016;57:575–584. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Owens EB, Hinshaw SP. Perinatal problems and psychiatric comorbidity among children with ADHD. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2013;42:762–768. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Webster-Stratton C, Reid MJ, Hammond M. Treating children with early-onset conduct problems: intervention outcomes for parent, child, and teacher training. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2004;33:105–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Treating children with early-onset conduct problems: intervention outcomes for parent, child, and teacher training. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2004;33:105–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Smeekens S, Riksen-Walraven JM, van Bakel HJ. Multiple determinants of externalizing behavior in 5-year-olds: a longitudinal model. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2007;35:347–361. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Brody GH, Murry VM, Kim S, Brown AC. Longitudinal pathways to competence and psychological adjustment among African American children living in rural single-parent households. Child Dev. 2002;73:1505–1516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Padrón A, Galán I, García-Esquinas E, Fernández E, Ballbè M, Rodríguez-Artalejo F. Exposure to secondhand smoke in the home and mental health in children: a population-based study. Tob Control. 2016;25:307–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Royal College of Physicians Royal College of Psychiatrists (RCP/RCPsy) Smoking and mental health. London: RCP; 2013. Available from: http://www.ncsct.co.uk/usr/pub/Smoking%20and%20mental%20health.pdf. [Google Scholar]

London: RCP; 2013. Available from: http://www.ncsct.co.uk/usr/pub/Smoking%20and%20mental%20health.pdf. [Google Scholar]

62. McLoyd V. How money matters for children’s socioemotional adjustment: Family processes and parental investment. Carlo G, Crockett L, Caranza M editors; Addressing youth health disparities in the twenty first century. Based on 57th Annual Nebraska Symposium on motivation. Springer; New York; In: Motivation and health. 2011. pp. 33–72. [Google Scholar]

63. Odgers CL, Caspi A, Russell MA, Sampson RJ, Arseneault L, Moffitt TE. Supportive parenting mediates neighborhood socioeconomic disparities in children’s antisocial behavior from ages 5 to 12. Dev Psychopathol. 2012;24:705–721. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Galler JR, Bryce CP, Waber DP, Hock RS, Harrison R, Eaglesfield GD, Fitzmaurice G. Infant malnutrition predicts conduct problems in adolescents. Nutr Neurosci. 2012;15:186–192. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Conger RD, Donnellan MB. An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:175–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Conger RD, Donnellan MB. An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:175–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Taylor SE, Seeman TE. Psychosocial resources and the SES-health relationship. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;896:210–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Shaw DS, Hyde LW, Brennan LM. Early predictors of boys’ antisocial trajectories. Dev Psychopathol. 2012;24:871–888. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Waller R, Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, Gardner F, Wilson MN, Hyde LW. Does early childhood callous-unemotional behavior uniquely predict behavior problems or callous-unemotional behavior in late childhood? Dev Psychol. 2016;52:1805–1819. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Shaw DS, Bell RQ, Gilliom M. A truly early starter model of antisocial behavior revisited. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2000;3:155–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70. Fischer M, Rolf JE, Hasazi JE, Cummings L. Follow-up of a preschool epidemiological sample: cross-age continuities and predictions of later adjustment with internalizing and externalizing dimensions of behavior. Child Dev. 1984;55:137–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Child Dev. 1984;55:137–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Mian ND, Wainwright L, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Carter AS. An ecological risk model for early childhood anxiety: the importance of early child symptoms and temperament. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2011;39:501–512. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Dougherty LR, Smith VC, Bufferd SJ, Stringaris A, Leibenluft E, Carlson GA, Klein DN. Preschool irritability: longitudinal associations with psychiatric disorders at age 6 and parental psychopathology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52:1304–1313. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

73. Szczepaniak D, McHenry MS, Nutakki K, Bauer NS, Downs SM. The prevalence of at-risk development in children 30 to 60 months old presenting with disruptive behaviors. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2013;52:942–949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

74. Raudino A, Woodward LJ, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Childhood conduct problems are associated with increased partnership and parenting difficulties in adulthood. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2012;40:251–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2012;40:251–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

75. Patterson GR, DeBaryshe BD, Ramsey E. A developmental perspective on antisocial behavior. Am Psychol. 1989;44:329–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

76. Brennan LM, Shaw DS. Revisiting data related to the age of onset and developmental course of female conduct problems. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2013;16:35–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

77. Michalska KJ, Decety J, Zeffiro TA, Lahey BB. Association of regional gray matter volumes in the brain with disruptive behavior disorders in male and female children. Neuroimage Clin. 2014;7:252–257. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

78. Fahim C, He Y, Yoon U, Chen J, Evans A, Pérusse D. Neuroanatomy of childhood disruptive behavior disorders. Aggress Behav. 2011;37:326–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

79. Sebastian CL, McCrory EJ, Cecil CA, Lockwood PL, De Brito SA, Fontaine NM, Viding E. Neural responses to affective and cognitive theory of mind in children with conduct problems and varying levels of callous-unemotional traits. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:814–822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:814–822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

80. Raine A, Yang Y, Narr KL, Toga AW. Sex differences in orbitofrontal gray as a partial explanation for sex differences in antisocial personality. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16:227–236. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

81. Kiehl KA, Smith AM, Mendrek A, Forster BB, Hare RD, Liddle PF. Temporal lobe abnormalities in semantic processing by criminal psychopaths as revealed by functional magnetic resonance imaging. Psychiatry Res. 2004;130:27–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

82. Kohrt BA, Hruschka DJ, Kohrt HE, Carrion VG, Waldman ID, Worthman CM. Child abuse, disruptive behavior disorders, depression, and salivary cortisol levels among institutionalized and community-residing boys in Mongolia. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2015;7:7–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

83. Martel MM, Roberts BA. Prenatal testosterone increases sensitivity to prenatal stressors in males with disruptive behavior disorders. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2014;44:11–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2014;44:11–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

84. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) 2006. Parent-training/education programmes in the management of children with conduct disorders. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/TA102guidance.pdf. [Google Scholar]

85. Smith JD, Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, Wilson MN, Winter CC, Patterson GR. Coercive family process and early-onset conduct problems from age 2 to school entry. Dev Psychopathol. 2014;26:917–932. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

86. Lynch RJ, Kistner JA, Allan NP. Distinguishing among disruptive behaviors to help predict high school graduation: does gender matter? J Sch Psychol. 2014;52:407–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

87. Serra-Pinheiro MA, Mattos P, Regalla MA, de Souza I, Paixão C. Inattention, hyperactivity, oppositional-defiant symptoms and school failure. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2008;66:828–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

88. Spruyt K, Gozal D. Sleep disturbances in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11:565–577. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sleep disturbances in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11:565–577. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

89. Shanahan L, Copeland WE, Angold A, Bondy CL, Costello EJ. Sleep problems predict and are predicted by generalized anxiety/depression and oppositional defiant disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53:550–558. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

90. Dougherty LR, Smith VC, Bufferd SJ, Kessel E, Carlson GA, Klein DN. Preschool irritability predicts child psychopathology, functional impairment, and service use at age nine. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56:999–1007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

91. Stringaris A, Lewis G, Maughan B. Developmental pathways from childhood conduct problems to early adult depression: findings from the ALSPAC cohort. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205:17–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

92. Luby JL, Gaffrey MS, Tillman R, April LM, Belden AC. Trajectories of preschool disorders to full DSM depression at school age and early adolescence: continuity of preschool depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:768–776. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Trajectories of preschool disorders to full DSM depression at school age and early adolescence: continuity of preschool depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:768–776. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

93. Kretschmer T, Hickman M, Doerner R, Emond A, Lewis G, Macleod J, Maughan B, Munafò MR, Heron J. Outcomes of childhood conduct problem trajectories in early adulthood: findings from the ALSPAC study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23:539–549. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

94. van der Molen E, Blokland AA, Hipwell AE, Vermeiren RR, Doreleijers TA, Loeber R. Girls’ childhood trajectories of disruptive behavior predict adjustment problems in early adolescence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56:766–773. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

95. Burke JD, Waldman I, Lahey BB. Predictive validity of childhood oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder: implications for the DSM-V. J Abnorm Psychol. 2010;119:739–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

96. Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM. Show me the child at seven: the consequences of conduct problems in childhood for psychosocial functioning in adulthood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46:837–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM. Show me the child at seven: the consequences of conduct problems in childhood for psychosocial functioning in adulthood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46:837–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

97. Engqvist U, Rydelius PA. Death and suicide among former child and adolescent psychiatric patients. BMC Psychiatry. 2006;6:51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

98. Ogundele MO. The Influence of Socio-Economic Status on the Prevalence of School-Age Childhood Behavioral Disorders in a Local District Clinic of North West England. J Fam Med and Health Care. 2016;2:98–107. [Google Scholar]

99. Strickland J, Hopkins J, Keenan K. Mother-teacher agreement on preschoolers’ symptoms of ODD and CD: does context matter? J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2012;40:933–943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

100. American Academy of Pediatrics (APA) 2012. Mental Health Screening and Assessment Tools for Primary Care. Available from: https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/Mental-Health/Documents/MH_ScreeningChart. pdf. [Google Scholar]

pdf. [Google Scholar]

101. Shaw DS, Bell RQ. Developmental theories of parental contributors to antisocial behavior. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1993;21:493–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

102. Comer JS, Chow C, Chan PT, Cooper-Vince C, Wilson LA. Psychosocial treatment efficacy for disruptive behavior problems in very young children: a meta-analytic examination. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52:26–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

103. Hawes DJ, Price MJ, Dadds MR. Callous-unemotional traits and the treatment of conduct problems in childhood and adolescence: a comprehensive review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2014;17:248–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

104. Cunningham CE, Boyle MH. Preschoolers at risk for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder: family, parenting, and behavioral correlates. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2002;30:555–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

105. Gardner F, Burton J, Klimes I. Randomised controlled trial of a parenting intervention in the voluntary sector for reducing child conduct problems: outcomes and mechanisms of change. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:1123–1132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:1123–1132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

106. Hutchings J, Gardner F, Bywater T, Daley D, Whitaker C, Jones K, Eames C, Edwards RT. Parenting intervention in Sure Start services for children at risk of developing conduct disorder: pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2007;334:678. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

107. Perrin EC, Sheldrick RC, McMenamy JM, Henson BS, Carter AS. Improving parenting skills for families of young children in pediatric settings: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:16–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

108. Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Supplee L, Gardner F, Arnds K. Randomized trial of a family-centered approach to the prevention of early conduct problems: 2-year effects of the family check-up in early childhood. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

109. Funderburk BW, Eyberg SM. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy. In: History of Psychotherapy: Continuity and Change. , editor. Norcross JC VandenBos GR Freedheim DK editors. 2nd ed. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2011. pp. 415–420. [Google Scholar]

, editor. Norcross JC VandenBos GR Freedheim DK editors. 2nd ed. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2011. pp. 415–420. [Google Scholar]

110. Thomas R, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ. Behavioral outcomes of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy and Triple P-Positive Parenting Program: a review and meta-analysis. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2007;35:475–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

111. Furlong M, McGilloway S, Bywater T, Hutchings J, Smith SM, Donnelly M. Cochrane review: behavioural and cognitive-behavioural group-based parenting programmes for early-onset conduct problems in children aged 3 to 12 years (Review) Evid Based Child Health. 2013;8:318–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

112. Lane KL. Identifying and Supporting Students at Risk for Emotional and Behavioral Disorders within Multi-level Models: Data Driven Approaches to Conducting Secondary Interventions with an Academic Emphasis. Education & Treatment of Children. 2007;30:135–164. [Google Scholar]

113. Farley C, Torres C, Wailehua C-UT, Cook L. Evidence-Based Practices for Students with Emotional and Behavioral Disorders: Improving Academic Achievement. Beyond Behavior. 2012;21:37–43. [Google Scholar]

Evidence-Based Practices for Students with Emotional and Behavioral Disorders: Improving Academic Achievement. Beyond Behavior. 2012;21:37–43. [Google Scholar]

114. Winther J, Carlsson A, Vance A. A pilot study of a school-based prevention and early intervention program to reduce oppositional defiant disorder/conduct disorder. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2014;8:181–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

115. Horner RG, Sugai G, Vincent C. School-wide Positive Behavior Support: Investing in Student Success. Impact. 2005;18:4. [Google Scholar]

116. Mesibov GB, Shea V, Schopler E. The TEACCH approach to autism spectrum disorders. New York NY: Springer-Verglag; 2007. p. 211. Available from: http://www.springer.com/gb/book/9780306486463. [Google Scholar]

117. Warren Z, Veenstra-VanderWeele J, Stone W, Bruzek JL, Nahmias AS, Foss-Feig JH, Jerome RN, Krishnaswami S, Sathe NA, Glasser AM, et al. Therapies for Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders, 2011 [Google Scholar]

118. Christie P. The Distinctive Clinical and Educational Needs of Children with Pathological Demand Avoidance Syndrome: Guidelines for Good Practice. Good Autism Practice. 2007;8:3–11. [Google Scholar]

Christie P. The Distinctive Clinical and Educational Needs of Children with Pathological Demand Avoidance Syndrome: Guidelines for Good Practice. Good Autism Practice. 2007;8:3–11. [Google Scholar]

119. Lindgren S, Doobay A. 2011. Evidence-Based Interventions for Autism Spectrum Disorders. Available from: http://www.interventionsunlimited.com/editoruploads/files/Iowa%20DHS%20Autism%20Interventions%206-10-11.pdf. [Google Scholar]

120. Ollendick TH, King NJ. Empirically supported treatments for children with phobic and anxiety disorders: current status. J Clin Child Psychol. 1998;27:156–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

121. Liber JM, De Boo GM, Huizenga H, Prins PJ. School-based intervention for childhood disruptive behavior in disadvantaged settings: a randomized controlled trial with and without active teacher support. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81:975–987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

122. Wong C, Odom SL, Hume K, Cox AW, Fettig A, Kucharczyk S. Evidence-based practices for children youth and young adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute Autism Evidence-Based Practice Review Group; 2013. Available from: http://autismpdc.fpg.unc.edu/sites/autismpdc.fpg.unc.edu/files/2014-EBP-Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute Autism Evidence-Based Practice Review Group; 2013. Available from: http://autismpdc.fpg.unc.edu/sites/autismpdc.fpg.unc.edu/files/2014-EBP-Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

123. Reichow B, Volkmar FR. Social skills interventions for individuals with autism: evaluation for evidence-based practices within a best evidence synthesis framework. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40:149–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

124. Carr EG, Durand VM. Reducing behavior problems through functional communication training. J Appl Behav Anal. 1985;18:111–126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

125. Koegel RL, Koegel LK. Pivotal response treatments for autism: Communication social and academic development. Baltimore MD: Brookes; 2006. p. 312. Available from: http://products.brookespublishing.com/Pivotal-Response-Treatments-for-Autism-P63.aspx. [Google Scholar]

126. Carr EG, Dunlap G, Horner RH, Koegel RL, Turnbull AP, Sailor W, Fox L. Positive behavior support: evolution of an applied science. J Pos Beh Interv. 2002;4:4–16. [Google Scholar]

Positive behavior support: evolution of an applied science. J Pos Beh Interv. 2002;4:4–16. [Google Scholar]

127. Reid R, Trout AL, Schartz M. Self-Regulation Interventions for Children with Attention Hyperactivity Disorder. Exceptional Children. 2005;71:361–377. [Google Scholar]

128. Schepis MM, Reid DH, Ownbey J, Parsons MB. Training support staff to embed teaching within natural routines of young children with disabilities in an inclusive preschool. J Appl Behav Anal. 2001;34:313–327. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

129. Beukelman DR, Mirenda P. Augmentative and alternative communication: Supporting children and adults with complex communication needs. Baltimore MD: Brookes; 2013. p. 616. Available from: http://products.brookespublishing.com/Augmentative-and-Alternative-Communication-P626.aspx. [Google Scholar]

130. Drager K, Light J, McNaughton D. Effects of AAC interventions on communication and language for young children with complex communication needs. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2010;3:303–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2010;3:303–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

131. Mirenda P. Supporting individuals with challenging behavior through functional communication training and AAC: Research review. Augment Altern Commun. 1997;13:207–225. [Google Scholar]

132. Hart JE, Whalon KJ. Promote academic engagement and communication of students with autism spectrum disorder in inclusive settings. ISC. 2008;44:116–120. [Google Scholar]

133. Briars L, Todd T. A Review of Pharmacological Management of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2016;21:192–206. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

134. Chan E, Fogler JM, Hammerness PG. Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Adolescents: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2016;315:1997–2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

135. McPheeters ML, Warren Z, Sathe N, Bruzek JL, Krishnaswami S, Jerome RN, Veenstra-Vanderweele J. A systematic review of medical treatments for children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e1312–e1321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pediatrics. 2011;127:e1312–e1321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

136. Roy A, Roy M, Deb S, Unwin G, Roy A. Are opioid antagonists effective in attenuating the core symptoms of autism spectrum conditions in children: a systematic review. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2015;59:293–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

137. Sonuga-Barke EJ, Daley D, Thompson M, Laver-Bradbury C, Weeks A. Parent-based therapies for preschool attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized, controlled trial with a community sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:402–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

138. Doyle CA, McDougle CJ. Pharmacologic treatments for the behavioral symptoms associated with autism spectrum disorders across the lifespan. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2012;14:263–279. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

139. Pringsheim T, Hirsch L, Gardner D, Gorman DA. The pharmacological management of oppositional behaviour, conduct problems, and aggression in children and adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Part 1: psychostimulants, alpha-2 agonists, and atomoxetine. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60:42–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Part 1: psychostimulants, alpha-2 agonists, and atomoxetine. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60:42–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

140. Kodish I, Rockhill C, Varley C. Pharmacotherapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13:439–452. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

141. Gledhill J, Hodes M. Management of depression in children and adolescents. Prog Neurol Psychiatry. 2015;19:28–33. [Google Scholar]

142. Shelton KH, Collishaw S, Rice FJ, Harold GT, Thapar A. Using a genetically informative design to examine the relationship between breastfeeding and childhood conduct problems. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20:571–579. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

143. Bandiera FC, Richardson AK, Lee DJ, He JP, Merikangas KR. Secondhand smoke exposure and mental health among children and adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165:332–338. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

What is childhood depression?

Childhood depression is an emotional disorder accompanied by behavioral disturbances and mood swings. Symptoms and risk factors for depression differ between children and adults. There is an assumption that from a genetic point of view, these are two different diseases. However, the treatment of childhood depression in terms of its content and methods is close to the treatment of this disorder in adults. High-quality treatment from qualified specialists helps to get rid of childhood depression in just a few months. nine0003

Symptoms and risk factors for depression differ between children and adults. There is an assumption that from a genetic point of view, these are two different diseases. However, the treatment of childhood depression in terms of its content and methods is close to the treatment of this disorder in adults. High-quality treatment from qualified specialists helps to get rid of childhood depression in just a few months. nine0003

Symptoms of childhood depression

In children, depression can begin to develop from 3-4 months - this is the so-called infantile depression. This type of depression, in contrast to childhood, is more similar in symptoms to an adult. An infant suffering from this disorder loses all interest in life and experiences constant apathy. Childhood depression may begin to manifest itself at the age of 3-4 years, but usually develops during the early school years. nine0003

In children, as a rule, depression manifests itself in the form of problematic, deviant behavior.

Any depression in the first place is always associated with a decrease in mood. Treatment for depression in adults usually focuses on dealing with negative emotions. However, in children, this disorder does not present with the symptoms that are characteristic of adolescents or adults with depression. Children usually do not want to sleep much or not get out of bed at all. They have a normal appetite and no suicidal thoughts. In children, as a rule, depression manifests itself in the form of problematic, deviant behavior. Very often, parents, teachers and even professionals confuse such symptoms with behavioral problems. Adults see a child as a bully or a bad student, and do not even realize that this is a form of childhood depression. The child begins to rebel against the school, the rules and the system. For children, unlike adolescence, this behavior is not normal, unless the child is exposed to serious negative factors, such as physical abuse. nine0003

See also

What is depression?

It is extremely important for a child to be involved in society and thus develop basic cognitive and social functions. When this involvement is disturbed, the child stops going to school, to circles and is not interested in anything, and his normal development is also disturbed. Unfortunately, without the help of a psychiatrist and psychotherapist, the development of a depressed child cannot be restored. At the first manifestations of deviant behavior, parents should seek help from a specialist. nine0003

When this involvement is disturbed, the child stops going to school, to circles and is not interested in anything, and his normal development is also disturbed. Unfortunately, without the help of a psychiatrist and psychotherapist, the development of a depressed child cannot be restored. At the first manifestations of deviant behavior, parents should seek help from a specialist. nine0003

Causes of childhood depression and risk factors

The most likely cause of childhood depression is a genetic predisposition to the disease. However, in order for a genetic disorder to manifest itself, the child must be under the influence of certain risk factors. As a rule, in childhood, such factors are related to what happens in the family. A risk factor that provokes the development of the disease can be a divorce of the parents or a tense relationship between them. nine0003

To reduce the risk factors for depression in a child, parents should maintain a healthy family environment.

Another serious risk factor is bullying. If a child has a predisposition to depression, bullying by peers can trigger the mechanisms for the development of the disease. The child will begin to skip school and run away from interaction with the educational system in every possible way. Such children often run away from home so that they are not forced to go to school, to clubs and go out into the yard. Sometimes, however, school can be a place where a child feels safe and secure, running away from home problems. To reduce the risk factors for depression in a child, parents should maintain a healthy family environment. nine0003

Treatment of childhood depression

Childhood depression is diagnosed through a clinical interview with a psychiatrist or psychotherapist who specializes in child development. A psychiatrist may prescribe medication to help ease some of the symptoms and improve the child's mood. The psychotherapist will work with the patient himself and his parents using cognitive-behavioral or dynamic psychotherapy techniques. Unlike adults, it is quite difficult for a child of primary school and preschool age to explain that his condition is a disease that requires certain actions and treatment. Treatment for childhood depression is usually through music, art, games, and sports. By participating in games, the child can express himself, and through art, he can perceive the psychotherapeutic work of a specialist. nine0003

Unlike adults, it is quite difficult for a child of primary school and preschool age to explain that his condition is a disease that requires certain actions and treatment. Treatment for childhood depression is usually through music, art, games, and sports. By participating in games, the child can express himself, and through art, he can perceive the psychotherapeutic work of a specialist. nine0003

Parents are often unable to help their child cope with depression because they themselves are the cause of his condition. The psychotherapist works with parents and provides them with the tools to properly interact with the child. During the sessions, they learn about the methods of psychological support in such situations, and learn how to apply them in practice. If parents meet halfway, cooperate with a psychotherapist and follow all the recommendations, most symptoms of childhood depression can be removed within a month. The younger the child, the faster the healing process. nine0003

- Depression

Share:

Childhood depression - Neurocenter

It seems that depression is not a child's diagnosis at all. Does depression happen in children? Alas, but this one is.

Does depression happen in children? Alas, but this one is.

The most susceptible to this psycho-emotional disorder are teenagers, however, this disease can manifest itself much earlier, for example, at the age of 3-4 years. The course of childhood depression, of course, differs from that of adults. The biggest difficulty is that it is quite difficult for children to explain what is happening to them. Children cannot, like adults, consciously talk about their feelings and emotions. Even distinguishing feelings within themselves can be problematic for children. More often, a child's internal discomfort manifests itself in altered behavior, which only sensitive parents can notice. In young children, somatic symptoms become manifestations of depression: malaise, frequent morbidity, weakened immunity. Therefore, in order to understand the condition of the child, parents need to pay attention, and not write off his behavior as whims and bad character. nine0003

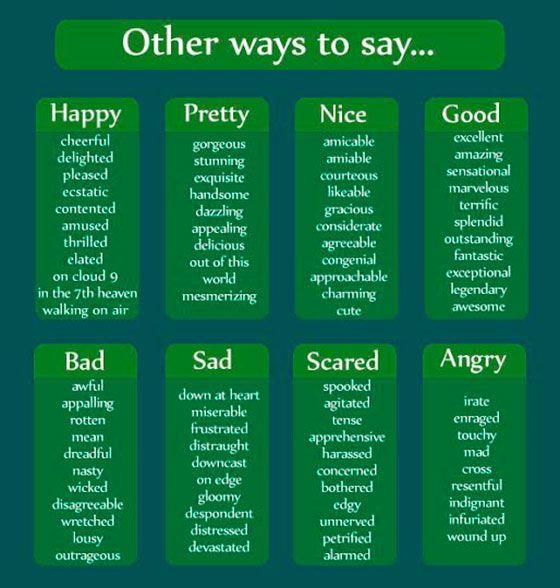

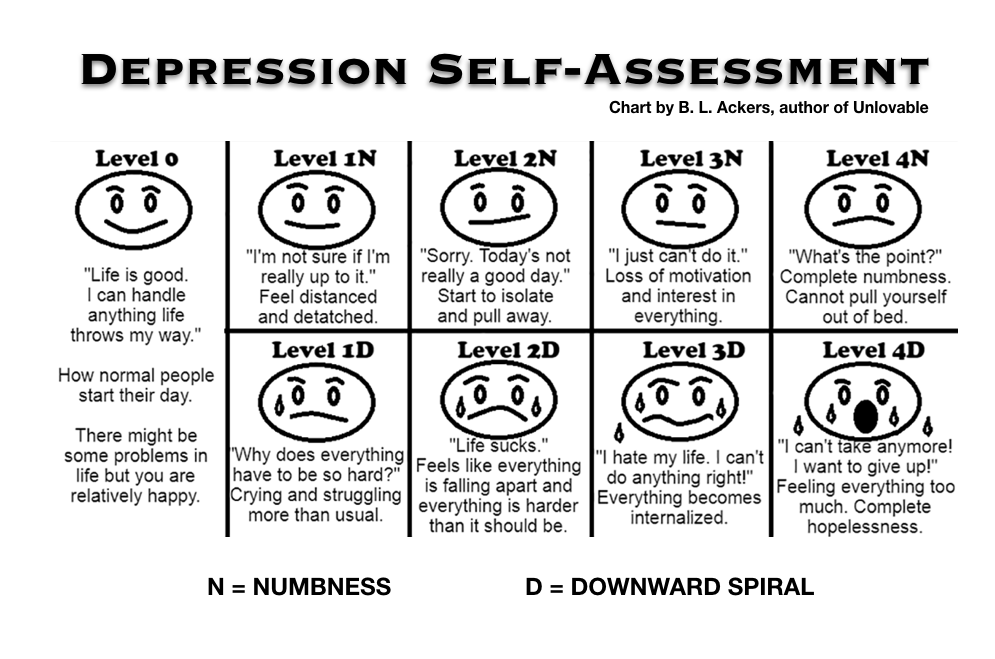

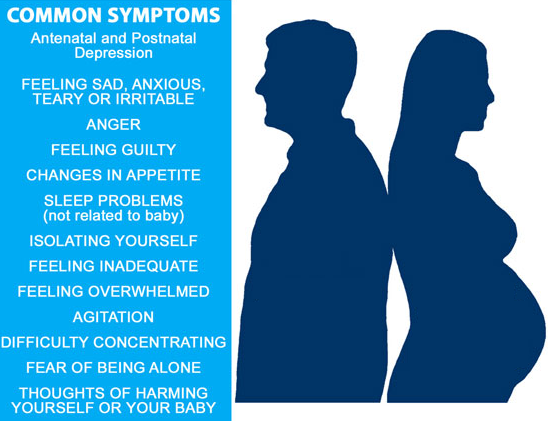

The symptoms of depression in children are different from the symptoms of depression in adults. primary symptoms of depression in children include: irrational fears, sadness, feelings of helplessness, mood swings. Sleep disturbances (insomnia, drowsiness, nightmares), appetite disturbances, decreased social activity, a feeling of constant fatigue, a desire for self-isolation, low self-esteem, problems with memory and concentration, thoughts of death, suicide may also appear. Elements 9 appear frequently0017 non-standard behavior - a sharp unreasonable unwillingness to play your favorite games or unreasonably aggressive reactions, children become rebellious and irritable, they "do not like everything." Anxiety in depressed children is most pronounced in the evening and at night.

primary symptoms of depression in children include: irrational fears, sadness, feelings of helplessness, mood swings. Sleep disturbances (insomnia, drowsiness, nightmares), appetite disturbances, decreased social activity, a feeling of constant fatigue, a desire for self-isolation, low self-esteem, problems with memory and concentration, thoughts of death, suicide may also appear. Elements 9 appear frequently0017 non-standard behavior - a sharp unreasonable unwillingness to play your favorite games or unreasonably aggressive reactions, children become rebellious and irritable, they "do not like everything." Anxiety in depressed children is most pronounced in the evening and at night.

Probably the most striking manifestation of childhood depression is the so-called "hospitalism" syndrome that occurs in children with prolonged separation from their parents. Variants of a difficult experience of breaking the emotional connection with the mother can be the hospitalization of the mother or child due to illness, business trips of the parents. nine0003

nine0003

Childhood depression can be caused by a difficult family situation: alcoholic parents, mentally ill relatives, grief over the loss of another family member, changes in family composition, physical or psychological abuse in the home.

Often, depression in school-age children is manifested as a result of such a phenomenon as “mobbing” or “bullying” by peers or teachers themselves. Many children, out of fear, may not even tell their parents about such facts. nine0003

In some children with sensitive unstable nervous system, depressive episodes may occur even without any abrupt and traumatic events: parents are too busy with their own affairs or work, they began to pay less attention to the child; classmates did not take the game; the teacher did not give an opportunity to answer or did not praise...

However, not everything is explained only by psychogenic factors. The causes of childhood depression can also be:

- Pathology of the nervous system: the absence of a revitalization complex in a child aged 1 month may be a manifestation of the so-called cerebral depression, which is characteristic of premature babies or children who have undergone oxygen starvation during childbirth or intracranial birth trauma; nine0042

- Endogenous causes caused by the genetic predisposition of the child.

Manifestations of endogenous depression are usually protracted (chronic): children are lethargic, with reduced activity, there are signs of motor and mental retardation, it is difficult for such children to get out of bed in the morning;

Manifestations of endogenous depression are usually protracted (chronic): children are lethargic, with reduced activity, there are signs of motor and mental retardation, it is difficult for such children to get out of bed in the morning; - Severe somatic illnesses, injuries or operations suffered by children.

Before diagnosing " depression " it is necessary to carefully observe the mental and physical state of the child. Only a stable long-term combination of depressive symptoms allows you to accurately determine the type of disorder and also select the necessary treatment. nine0003

What should you do if you suspect depression in your child's behavior?

Creative activities have a positive effect on the state of the child: drawing, music, dancing. nine0042

Creative activities have a positive effect on the state of the child: drawing, music, dancing. nine0042