Cbt treatments for anxiety

Treating Anxiety with CBT (Guide)

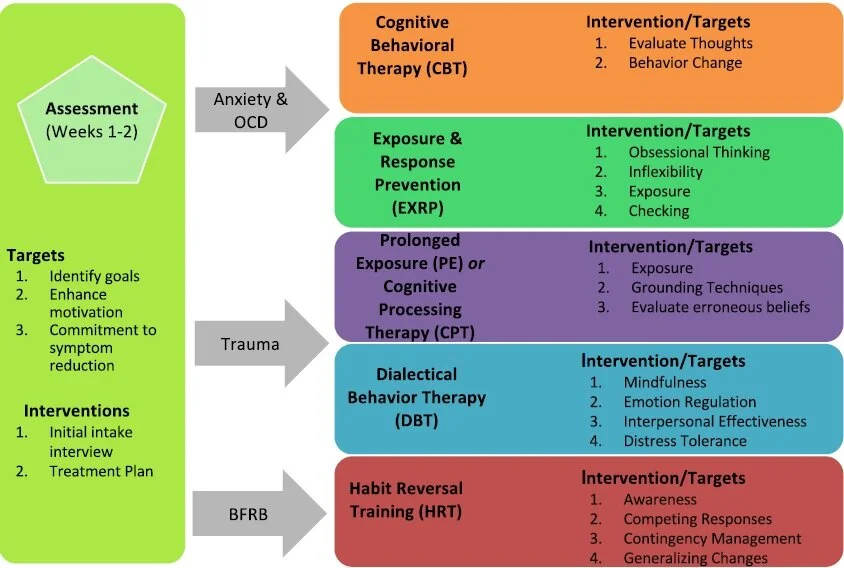

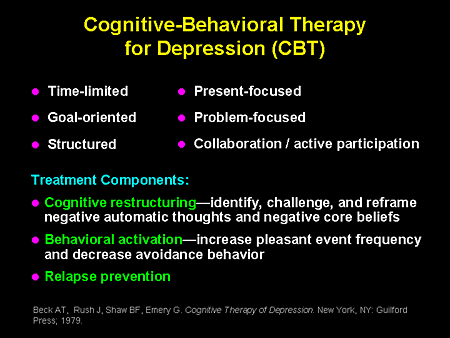

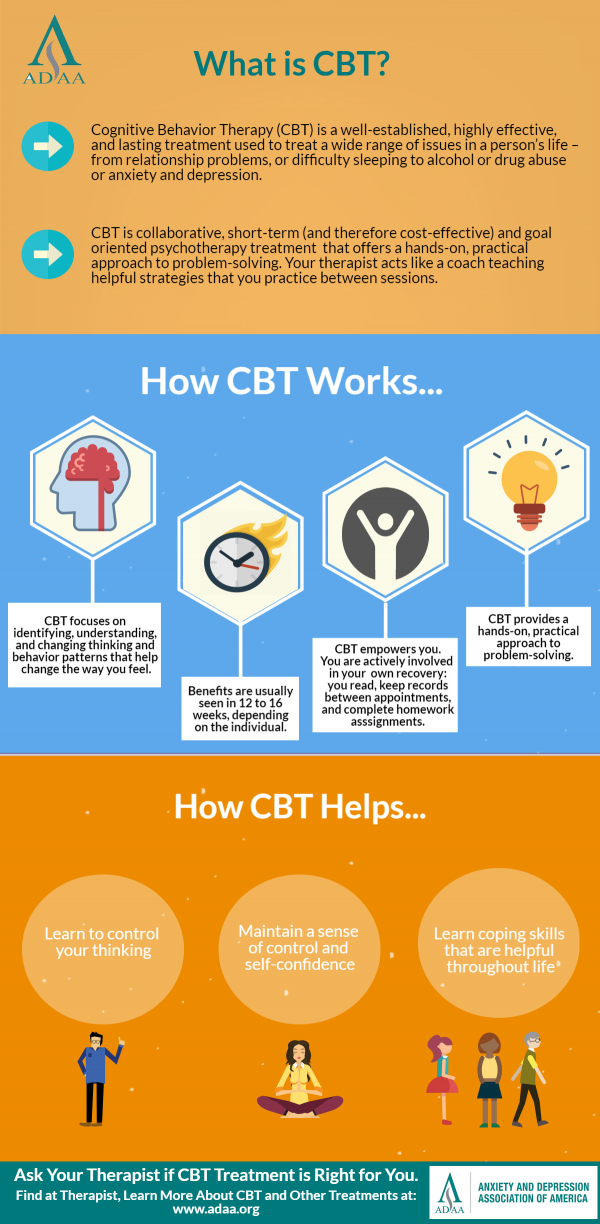

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has become the leading treatment for anxiety, and with good reason. Research indicates that CBT can be an effective treatment for anxiety after as few as 8 sessions, with or without any form of medication (4). Due to the high prevalence of anxiety disorders (18% of adults in the United States meet criteria for an anxiety disorder over a 1-year period [3]), it's valuable to have a strong understanding of best practices for its treatment.

This guide will provide a general overview of CBT for anxiety disorders without delving too deeply into any single diagnosis. Of course, one size doesn't fit all. It's important to be flexible and use your best clinical judgement when working with clients. One size doesn't fit all.

Theory

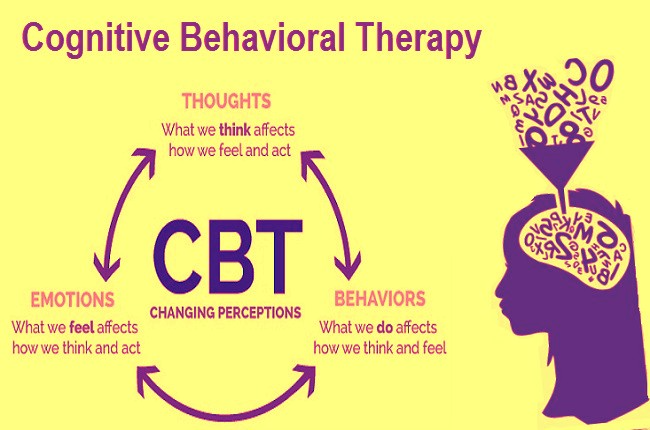

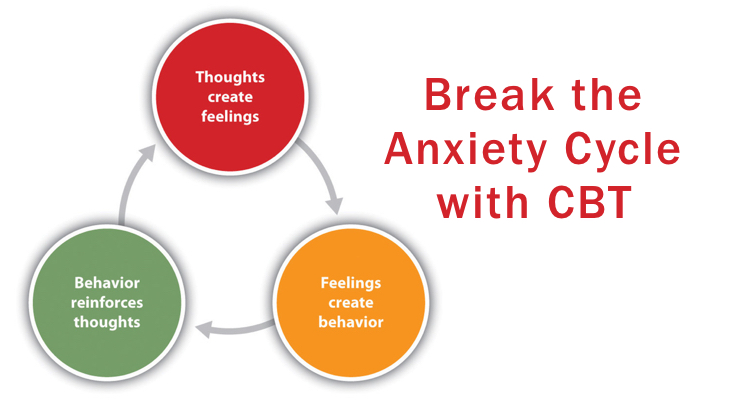

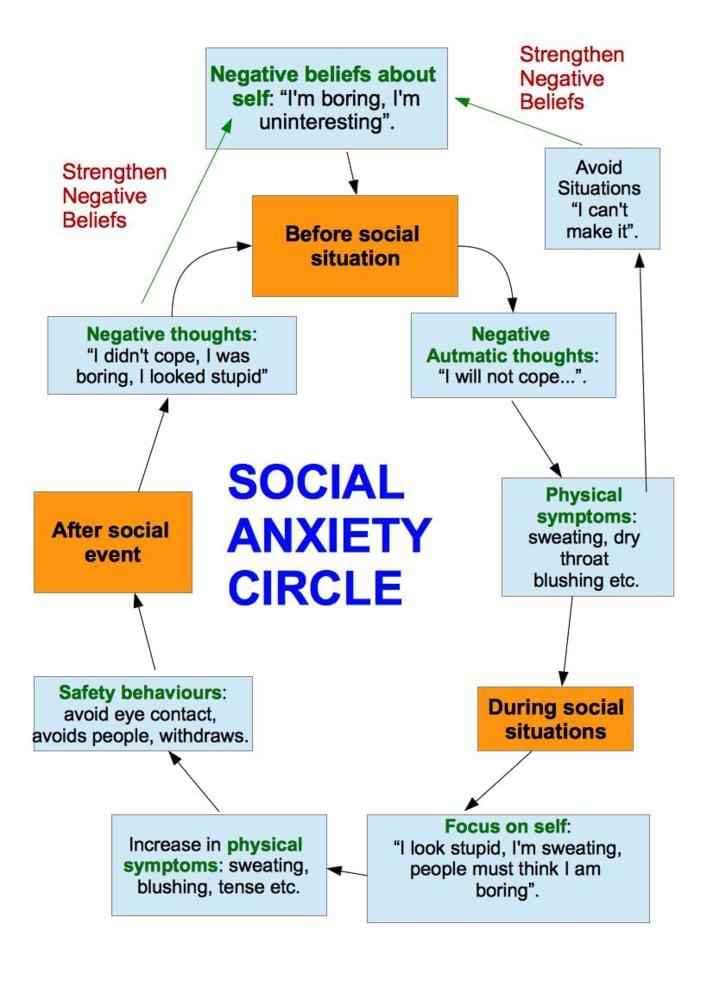

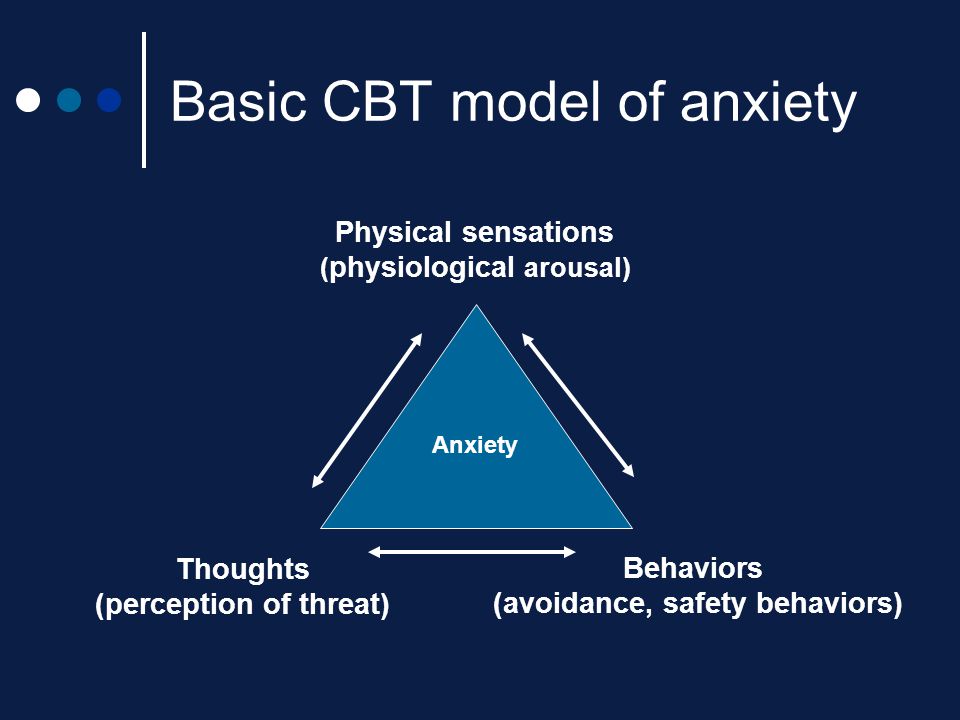

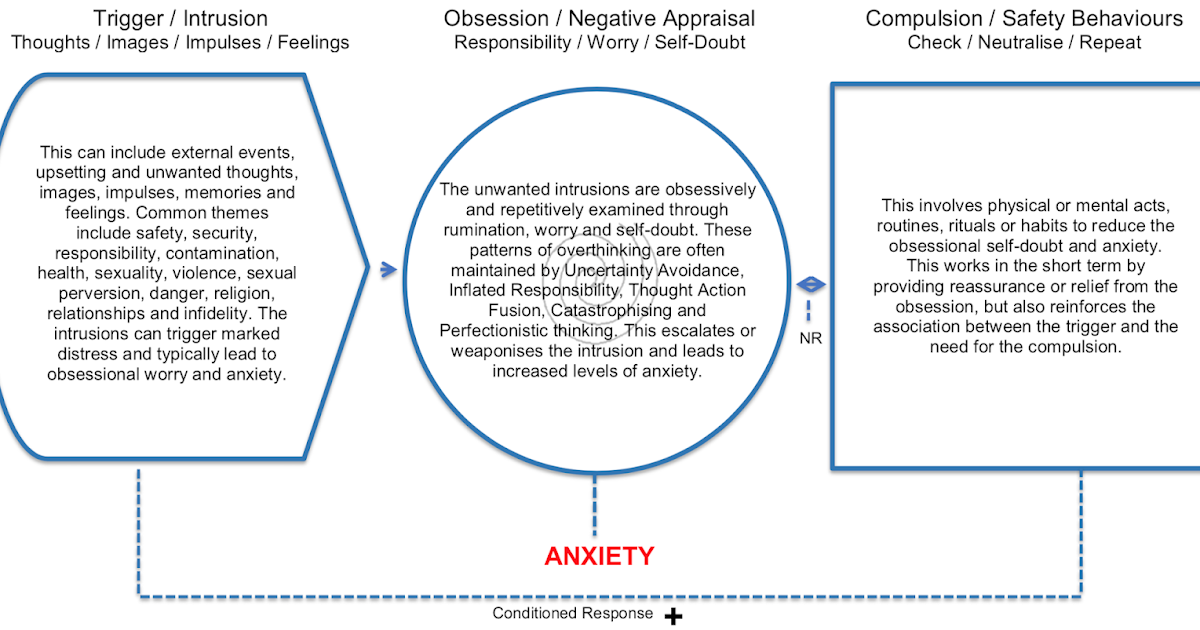

CBT works by identifying and addressing how a person's thoughts and behaviors interact to create anxiety. Therapists work with clients to recognize how negative thought patterns influence a person's feelings and behaviors. Here's an example of how two different people can react to a situation differently based upon their thoughts:

With CBT, a therapist attempts to intervene by changing negative thought patterns, teaching relaxation skills, and changing behaviors that lead to the problem worsening. To help provide motivation for treatment and get a client on board, providing psychoeducation about anxiety is the first step of treatment.

Treating Anxiety with CBT

Anxiety Psychoeducation

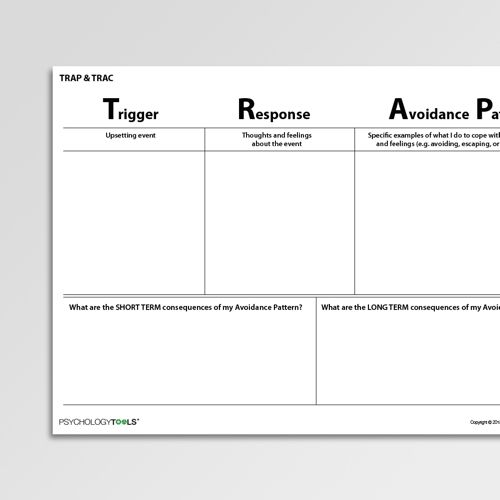

Clients who seek treatment for anxiety often have limited knowledge about their problem. They might know that they're afraid of snakes, large groups of people, or cars, but that's about it. Others might have a constant feeling of anxiety without really knowing what it's about. It's a good idea to start by discussing triggers, or sources of anxiety. What are the situations when a person feels most anxious? What do they think, and how do they respond in these situations? How is it affecting their life?

After a client has had an opportunity to discuss their own anxiety, it will be valuable to help them learn about anxiety in general. Anxiety is a feeling of intense discomfort, which drives people to avoid the feared stimuli. Anxiety is defined by avoidance.

Anxiety is a feeling of intense discomfort, which drives people to avoid the feared stimuli. Anxiety is defined by avoidance.

It's important for clients to understand that every time they avoid an anxiety-producing situation, their anxiety will be even worse the next time around. The brain sees it like this: "When I avoid this situation, I feel better. I guess I should try to avoid it next time too." Look at this graph to help visualize how it works:

Education about the Yerkes-Dodson law can help a client to understand why they have anxiety, how it is hurting them, and how a certain amount of anxiety can be beneficial. The Yerkes-Dodson law states that too little or too much anxiety are both harmful, and that a person reaches optimal performance on a task with a moderate level of anxiety.

Someone who has no anxiety has little motivation to keep up with their responsibilities and someone with too much anxiety will attempt to avoid the situation, or perform poorly due to their symptoms. However, someone with a moderate level of anxiety will be motivated to prepare, concentrate, or do whatever is necessary for their particular situation without becoming debilitated or avoidant.

However, someone with a moderate level of anxiety will be motivated to prepare, concentrate, or do whatever is necessary for their particular situation without becoming debilitated or avoidant.

Next, it'll be important to educate your client about symptoms and common reactions to anxiety. Everyone deals with their emotions differently, so help your client identify what they do when they're anxious. Give examples such as tapping feet, pacing, sweating, becoming irritable, thinking about the situation non-stop, insomnia, nausea, nail biting, avoidance—anything that will help your client become more aware when they are experiencing anxiety. It's important that your client recognizes when they feel anxious, because the next step will be for them to intervene during those situations.

Challenging Negative Thoughts

Before challenging thoughts will be effective, clients need to understand the relationship between thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. It can be helpful to provide examples, and to discuss examples from the client's personal experiences.

Cognitive Behavioral Model

worksheet

Ask the client to practice identifying their thoughts by practicing in session, and then completing a thought log for homework. A thought log requires a client to describe situations that they experience, record the thought they had during that situation, and then the resulting consequence (both a behavior and emotion). Without practice identifying how thoughts and emotions are linked, the most important thoughts will pass by unnoticed and unchallenged. In this case, the client should focus on thoughts that contribute to anxiety.

Thought Log (blank)

worksheet

Once the client has practiced identifying their negative thoughts and they've become somewhat proficient at recognizing them, it will be time to begin challenging these thoughts. After having a thought that contributes to anxiety, the client will want to ask themselves: "Do I have evidence to support this thought, or am I making assumptions? Do I have good reason to be anxious?". Look at the following example:

Look at the following example:

In practice, challenging long-held beliefs can be very difficult. One technique to help ease this process is for clients to ask themselves a series of questions to assess their thoughts. Here are some examples:

"Is there evidence for my thought, or am I making assumptions?"

"What's the worst that could happen? Is that outcome likely?"

"What's the best that could happen?"

"What's most likely to happen?"

"Will this matter a week from now, a year from now, or five years from now?"

See the following worksheet for a list of questions that a client can keep to remind themselves of questions for challenging their negative thoughts.

Challenging Negative Thoughts

worksheet

After successfully challenging an old belief, your client will need to replace it with a new belief. I want to emphasize that the new belief does not need to be full of sunshine, rainbows, and happiness. Sometimes, the best replacement thought is just less negative. Some situations really are scary, and denying that won't do any good. The idea is to think neutrally rather than negatively, and to put fears into perspective. Someone suffering from extreme anxiety usually perceives a situation as more dangerous than it really is.

Some situations really are scary, and denying that won't do any good. The idea is to think neutrally rather than negatively, and to put fears into perspective. Someone suffering from extreme anxiety usually perceives a situation as more dangerous than it really is.

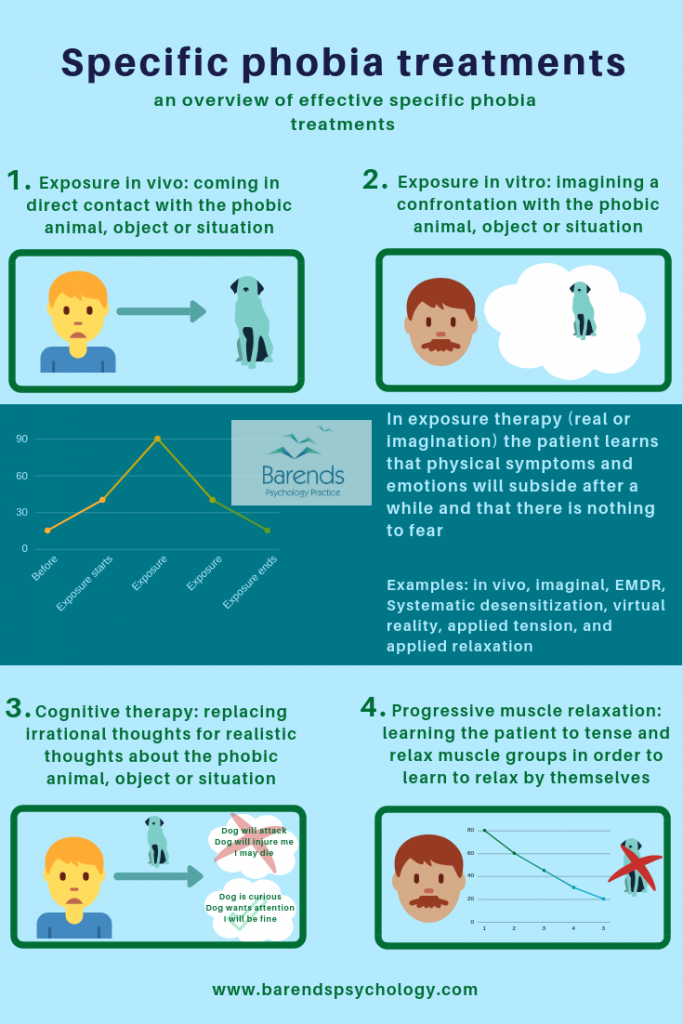

Exposure Therapy / Systematic Desensitization

The basic idea of exposure therapy is to face your fears. When someone exposes themselves to the source of their anxieties and nothing bad happens, the anxiety lessens. This doesn't mean that you should throw someone with a fear of spiders into a room of tarantulas and lock the door (though some have had success with this—it's called "flooding". We don't recommend it unless you really know what you're doing). Instead, you'll gradually work your way up to the feared stimuli with the client in a process called systematic desensitization.

The first step of systematic desensitization is to create a fear hierarchy. Identify the anxiety you would like to address with your client, and then create a list of steps leading up to it with rankings of how anxiety-producing you think the situation would be. Here's an example:

Here's an example:

Exposure Hierarchy

worksheet

Now, before following through and exposing a client to these stimuli, they must learn relaxation techniques to learn during the process. These can include deep breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, or meditation. They're described in detail in the next session of this guide.

Finally, the client will follow through with the fear hierarchy (with the clinician's assistance). The goal is for the client to be exposed to stimuli that are only moderately anxiety-producing while using relaxation skills to manage their response. Eventually, the client can move on to the more challenging situations that they identified in the fear hierarchy.

The exposure process should happen over the course of several sessions, and the client should be allowed to become comfortable at each stage before moving on. The clinician will present the feared stimuli and ask the client to use a relaxation skill. Eventually, the stimuli can be removed and the process should be discussed.

Eventually, the stimuli can be removed and the process should be discussed.

If it becomes difficult to move between stages, try coming up with an in-between stage that's less anxiety-producing. For example, if touching the spider is too much, let it walk nearby without making contact. There shouldn't be any surprises during systematic desensitization—the client should be comfortable and know exactly what's coming. Additionally, know when to stop. Does the client need to reach the point where spiders can crawl on them, or is tolerating them near by enough?

Relaxation Skills

Relaxation skills are techniques that allow a person to initiate a calming response within their body. Everyone has their own preferences and skills that they find work best for them, so expect some trial and error before finding the technique that fits with each client. Two of the most commonly used and effective relaxation skills are deep breathing (1) and progressive muscle relaxation (2).

Deep breathing (also known as diaphragmatic breathing) requires a client to take conscious control of their breathing. They will learn to breathe slowly using their diagram to initiate the body's relaxation response. There are many variations of this skill, and we've shared one easy-to-use method below:

They will learn to breathe slowly using their diagram to initiate the body's relaxation response. There are many variations of this skill, and we've shared one easy-to-use method below:

- Sit comfortably in your chair. Place your hand on your stomach so you are able to feel your diaphragm move as you breathe.

- Take a deep breath through your nose. Breathe in slowly. Time the breath to last 5 seconds.

- Hold the breath for 5 seconds. You can do less time if it's difficult or uncomfortable.

- Release the air slowly (again, time 5 seconds). Do this by puckering your lips and pretending that you are blowing through a straw (it can be helpful to actually use a straw for practice).

- Repeat this process for about 5 minutes, preferably 3 times a day. The more you practice, the more effective deep breathing will be when you need it.

Instructions: Deep Breathing

Deep breathing can be valuable in the moment when confronting something anxiety-producing, or in general as a way to reduce overall stress. It will be valuable for your clients to practice deep breathing daily even when they're feeling fine—the effects can be long-lasting.

It will be valuable for your clients to practice deep breathing daily even when they're feeling fine—the effects can be long-lasting.

Deep Breathing Exercise

video

Progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) requires a bit more effort than deep breathing, but it can significantly reduce feelings of anxiety (2). PMR requires the user to go through a checklist of muscles that they will purposefully tense and then relax. Using this technique will create a feeling of relaxation, and it will help to teach a client to better recognize when they are experiencing anxiety by recognizing the tension in their muscles. Because the script is lengthy, we have included it in a printable format below.

Progressive Muscle Relaxation Script

worksheet

Progressive Muscle Relaxation

video

1. Borkovec, T. D., & Costello, E. (1993). Efficacy of applied relaxation and cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61(4), 611-619.

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61(4), 611-619.

2. Dolbier, C. L., & Rush, T. E. (2012). Efficacy of abbreviated progressive muscle relaxation in a high-stress college sample. International Journal of Stress Management, 19(1), 48-68.

3. Kessler R. C., Chiu W. T., Demler O., & Walters E. E. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of twelve-month DSM-IV disorders. National Comorbidity Survey Replication Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 617-27.

4. Stewart, R. E., & Chambless, D. L. (2009). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders in clinical practice: A meta-analysis of effectiveness studies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(4), 595-606.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: an update on the empirical evidence

1. Chambless D., Ollendick TH. Empirically supported psychological interventions: Controversies and evidence. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:685–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Hans E., Hiller W. A meta-analysis of nonrandomized effectiveness studies on outpatient cognitive behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:954–964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hans E., Hiller W. A meta-analysis of nonrandomized effectiveness studies on outpatient cognitive behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:954–964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Hofmann SG., Smits JAJ. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychiat. 2008;69:621–632. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Norton PJ., Price EC. A meta-analytic review of adult cognitive-behavioral treatment outeome across the anxiety disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195:521–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Olatunji BO., Cisler JM., Deacon BJ. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: a review of meta-analytic f indings. Psychiatr ClinNorthAm. 2010;33:557–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Watts SE., Turnell A., Kladnitski N., Newby JM., Andrews G. Treatment-as-usual (TAU) is anything but usual: A meta-analysis of CBT versus TAU for anxiety and dépression. J Affect Disorders. 2015;175:152–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Affect Disorders. 2015;175:152–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Hofmann SG., Wu JQ., Boettcher H. Effect of cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders on quality of life: a meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82:375–391. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Simos G., Hofmann SG, editors. CBT for Anxiety Disorders: A Practitioner Book.Chichester, UK: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd; 2013. [Google Scholar]

9. Barlow DH, ed. Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

10. Foa EB., Kozak M. Emotional processing of fear: Exposure to corrective information. Psychol Bull. 1986;99:20–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Foa EB., Hembree EA., Rothbaum BO. Prolonged Exposure Therapy for PTSD: Emotional Processing of Traumatic Experiences. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

12. Resick P., Monson C. , Chard K. Cognitive Processing Therapist Group Manual: Veteran/Military Version. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans' Affaires; 2008. [Google Scholar]

13. Powers MB., Halpern JM., Ferenschak MP., Gillihan SJ., Foa EB. A metaanalytic review of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:635–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Taylor S., Thordarson D., Fedoroff I., Maxfield L., Lovell K., Ogrodniczuk J. Comparative efficacy, speed, and adverse effects of three PTSD Treatments: exposure therapy, EMDR, and relaxation training. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:330–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Foa EB., Hembree EA., Cahill SP., et al Randomized trial of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder with and without cognitive restructuring: outcome at academic and community clinics. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:953–964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Marks IM., Lovell K., Noshirvani H. , Livanou M. Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder by exposure and/or cognitive restructuring - A controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:317–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

, Livanou M. Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder by exposure and/or cognitive restructuring - A controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:317–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Paunovic N., Öst L-G. Cognitive-behavior therapy vs exposure therapy in the treatment of PTSD in refugees. Behav Res Ther. 2001;39:1183–1197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Foa EB., Yadin E., Lichner TK. Exposure and Response (Ritual) Prevention for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, Second Edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc; 2012. [Google Scholar]

19. Rosa-Alcázar Al., Sánchez-Meca J., Gómez-Conesa A., Marín-Martinez F. Psychological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28:1310–1325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Greist JH., Marks IM., Baer L., Kobak KA., Wenzel KW., Hirsch J. Behavior therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder guided by a computer or by a clinician compared with relaxation as a control. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:138–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:138–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Olatunji BO., Davis ML., Powers MB., Smits JAJ. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A meta-analysis of treatment outeome and moderators. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:33–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Abramowitz JS. Variants of exposure and response prevention in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Ther. 1996;27:583–600. [Google Scholar]

23. Mitte K. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of psycho- and pharmacotherapy in panic disorder with and without agoraphobia. J Affect Disord. 2005;88:27–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Gould RA., Otto MW., Pollack MH. A meta-analysis of treatment outeome for panic disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 1995;15:819–844. [Google Scholar]

25. Craske MG., DeCola JP., Sachs AD., Pontillo DC. Panic control treatment for agoraphobia. J Anxiety Disord . 2003;17:321–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Craske MG., Barlow DH. Mastery of Your Anxiety and Worry. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

Craske MG., Barlow DH. Mastery of Your Anxiety and Worry. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

27. Borkovec TD., Costello E. Efficacy of applied relaxation and cognitivebehavioral therapy in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:611–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Borkovec T., Newman MG., Pincus AL., Lytle R. A component analysis of cognitive-behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety disorder and the rôle of interpersonal problems. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:288–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Rapee RM., Heimberg RG. A cognitive-behavioral model of anxiety in social phobia. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:741–756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Feske U., Chambless DL. Cognitive behavioral vs exposure only treatment for social phobia: a meta-analysis. Behav Ther. 1995;26:695–720. [Google Scholar]

31. Gould RA., Buckminster S., Pollack MH. , Otto MW., Yap L. Cognitive-behavioral and pharmacological treatment for social phobia: a metaanalysis. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 1997;4:291–306. [Google Scholar]

, Otto MW., Yap L. Cognitive-behavioral and pharmacological treatment for social phobia: a metaanalysis. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 1997;4:291–306. [Google Scholar]

32. Taylor S. Meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral treatments for social. phobia. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1996;27:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Clark DM., Ehlers A., Hackmann A. Cognitive therapy versus exposure and applied relaxation in social phobia: A randomized controlled trial, J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:568–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Fedoroff IC., Taylor S. Psychological and pharmacological treatments of social phobia: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacoi. 2001;21:311–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Mayo-Wilson E., Dias S., Mavranezouli I., et al Psychological and pharmacological interventions for social anxiety disorder in adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(5):368–376. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Wolitzky-Taylor KB., Horowitz JD., Powers MB., Telch MJ. Psychological approaches in the treatment of specific phobias: A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28:1021–1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wolitzky-Taylor KB., Horowitz JD., Powers MB., Telch MJ. Psychological approaches in the treatment of specific phobias: A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28:1021–1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Öst L-G., Alm T., Brandburg M., Breitholtz E. One vs five sessions of exposure and five sessions of cognitive therapy in the treatment of claustrophobia. Behav Res Ther. 2001;39:167–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Norton PJ. A Randomized Clinical trial of transdiagnostic cognitivebehavioral treatments for anxiety disorder by comparison to relaxation training. Behav Ther. 2012;43:506–517. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Ehlers A., Clark DM., Hackmann A., McManus F., Fennell M. Cognitive therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: development and évaluation. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:413–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Tarrier N., Pilgrim H., Sommerfield C., et al A randomized trial of cognitive therapy and imaginal exposure in the treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:13–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Alvarez J., McLean C., Harris AHS., Rosen CS., Ruzek Jl., Kimerling R. The comparative effectiveness of cognitive processing therapy for maie vétérans treated in a VHA posttraumatic stress disorder residential rehabilitation program. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79:590–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Chard KM. An évaluation of cognitive processing therapy for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder related to childhood sexual abuse. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:965–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Forbes D., Lloyd D., Nixon RDV., et al A multisite randomized controlled effectiveness trial of cognitive processing therapy for militaryrelated posttraumatic stress disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2012;26:442–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Monson CM., Schnurr PP., Resick PA., Friedman MJ., Young-Xu Y., Stevens SP. Cognitive processing therapy for veterans with military-related posttraumatic stress disorder. j Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:898–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

j Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:898–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Suris A., Link-Malcolm J., Chard K., Ahn C., North C. A randomized clinical trial of cognitive processing therapy for veterans with PTSD related to military sexual trauma. J. Trauma Stress. 2013;26:28–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Resick P., Nishith P., Weaver TL., Astin MC., Feuer CA. A comparison of cognitive-processing therapy with prolonged exposure and a waiting condition for the treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in female râpe victims. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:867–879. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Ehlers A., Clark DM., Hackmann A., et al A randomized controlled trial of cognitive therapy, a self-help booklet, and repeated assessments as early interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:1024–1032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. McLean PD., Whittal ML., Thordarson DS. Cognitive versus behavior therapy in the group treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:205–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:205–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Craske MG., Barlow DH. Mastery of Your Anxiety and Panic. 4th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 2007 [Google Scholar]

50. Öst L-G., Westling BE., Hellstrôm K. Applied relaxation, exposure in vivo and cognitive methods in the treatment of panic disorder with agoraphobia. Behav Res Ther. 1993;31:383–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Cuijpers P., Sijbrandij M., Koole S., Huibers M., Berking M., Andersson G. Psychological treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: A meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34:130–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Dugas M., Brillon P., Gervais N., et al A randomized clinical trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy and applied relaxation for adults with generalized anxiety disorder. Behav Ther. 2010;41:46–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Arntz A. Cognitive therapy versus applied relaxation as treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:633–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:633–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Öst L-G., Breitholtz E. Applied relaxation vs. cognitive therapy in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2000;38:777–790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Hofmann SG. Cognitive factors that maintain social anxiety disorder: a comprehensive rnodel and its treatment implications. Cogn Behav Ther. 2007;36:193–209. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Craske MG., Barlow DH., Antony MM. Mastery of Your specific Phobia: Therapist Guide, Second Edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

57. Koch El., Spates CR., Himle JA. Comparison of behavioral and cognitive-behavioral one-session exposure treatments for small animal phobias. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42:1483–1504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders

Blog

Leave a comment

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is a form of therapy that has been proven to help overcome anxiety disorders.

Cognitive behavioral therapy and its goals.

- One of the main goals of CBT is to identify irrational beliefs and thought patterns and replace them with more realistic views.

- The ultimate goal of Cognitive Therapy is to change your core beliefs that influence how you interpret your environment. Changing your core beliefs will lead to lasting improvement in anxiety symptoms.

One of the central problems that CBT addresses is having automatic negative thoughts. People with anxiety have developed automatic negative ways of thinking that are inconsistent with reality, increase anxiety and reduce coping. These thoughts arise instantly when a person thinks about a situation that provokes anxiety. For example, if a person is afraid of public speaking, simply thinking about the situation will cause embarrassment and fear of failure. The goal of CBT is to replace these cognitive distortions with more realistic thoughts. A person suffering from an anxiety disorder is usually advised by close people to "think positively." Unfortunately, solving the problem is not so easy, because the brain programs itself over time for negative thinking and disturbing thoughts, it must be gradually taught to think in a new way. Just telling yourself "next time I'll worry less" doesn't work, given the current way of thinking.

A person suffering from an anxiety disorder is usually advised by close people to "think positively." Unfortunately, solving the problem is not so easy, because the brain programs itself over time for negative thinking and disturbing thoughts, it must be gradually taught to think in a new way. Just telling yourself "next time I'll worry less" doesn't work, given the current way of thinking.

To change negative automatic thinking in the long term, cognitive behavioral therapy requires practice and repetition every day for several months. Therapy begins with simple techniques: identifying negative automatic thoughts and replacing them with more neutral ones, and over time, realistic ones. A person with an anxiety disorder will begin to think, act, and feel differently, but it will take persistence, practice, and patience to achieve results. At first it is a conscious process, but as it is carried out and repeated, it becomes unconscious

The effects of CBT on anxiety should be gradual.

People often advise a person with anxiety disorder to "become braver and face your fears" - unfortunately, such an experience can exacerbate anxiety and lead to dire consequences.

How does CBT work?

Together with the therapist, the patient will gradually expose himself to dangerous situations so that over time they no longer cause fear. Initially, cognitive behavioral therapy provides an opportunity to practice imaginary exposure, such as imagining a speech or role-playing an interview. As soon as the practiced or imaginary situation becomes easier, there is a transition to the situation from the real world. If the impact training is too fast, it can be counterproductive.

If after reading the material of our publication you have any questions and desire to discuss them with a specialist, we invite you to our Neuropsychological Center PSYMED.

Sign up for a consultation with us

by phone: or fill out an application: Sign up for a consultation

How is the Cognitive Behavioral Therapy course?

Therapy uses a wide range of strategies (diary keeping, role play, relaxation techniques, etc. ) to help the client overcome negative thoughts. Cognitive behavioral therapy focuses on achieving goals that are jointly set by the client and therapist. The path to the result is thought out in detail, adjusted if necessary, and the client often receives homework between sessions to develop new skills and track their progress.

) to help the client overcome negative thoughts. Cognitive behavioral therapy focuses on achieving goals that are jointly set by the client and therapist. The path to the result is thought out in detail, adjusted if necessary, and the client often receives homework between sessions to develop new skills and track their progress.

CBT is used to correct a wide range of requests:

- Anxiety;

- Dependencies;

- Problems with aggression control;

- Bipolar disorder;

- Depression;

- Eating disorders;

- Panic attacks;

- Personality disorders;

- Phobias;

- Stress.

Benefits of CBT:

- being aware of negative and often unrealistic thoughts, a person can begin to use healthier thought patterns;

- CBT is an effective short-term therapy option;

- CBT remains effective without medical intervention;

- is a scientifically proven therapy;

- allows the client to develop coping strategies that can be used for self-help in the future.

As part of the therapeutic process, we address a number of problem areas, including:

- Misconceptions about one's abilities and self-esteem0022

- Guilt, embarrassment or anger due to past situations

- How to be more assertive

- Fight perfectionism and be more realistic

- Coping with procrastination associated with social anxiety 2

- Your CBT sessions may resemble a student-teacher relationship. The therapist will take on the role of a teacher, outlining concepts and helping you along the path of self-discovery and change. You will also be assigned homework assignments which are the key to success.

Learn more about the Cognitive Behavioral Therapy method and the conditions in which it is effective here.

Physician-supported Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Anxiety in Adults: An Evidence Review

Who might be interested in this review?

People who suffer from anxiety and their families.

General practitioners.

Professionals working in psychotherapy services.

Developers of online therapeutics for the treatment of mental disorders.

Why is this review important?

Many adults suffer from anxiety disorders that have a significant impact on their daily lives. Anxiety disorders often result in high health care costs and high costs to society in terms of absenteeism and reduced quality of life. Research has shown that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is an effective treatment for reducing anxiety. However, many people do not have access to face-to-face CBT due to long queues, lack of free time for appointments, transportation problems, and a limited number of qualified doctors.

Internet-based CBT (I-CBT) is a possible solution to overcome the many barriers to accessing face-to-face therapy. Physicians can provide support to patients who access Internet therapy by phone or email. It is hoped that this will increase the availability of CBT, especially for people living in rural areas. It is not yet known whether medically supported I-CBT is effective in reducing anxiety symptoms.

It is hoped that this will increase the availability of CBT, especially for people living in rural areas. It is not yet known whether medically supported I-CBT is effective in reducing anxiety symptoms.

What questions did this review seek to answer?

The purpose of the review is to summarize current research to determine whether physician-assisted I-CBT is an effective treatment for anxiety.

The purpose of this review is to answer the following questions.

- Is medically supported I-CBT more effective than no treatment (waiting list)?

- how effective is I-CBT with medical support compared to face-to-face CBT?

- How effective is I-CBT with medical support compared to CBT without medical support (self-help without a doctor)?

- what is the quality of current research on I-CBT with medical support for anxiety?

What studies were included in this review?

Databases were searched to find all clinically supported I-CBT studies for anxiety published up to March 2015. To be included in the review, studies had to be randomized, controlled, in adults over 18 years of age with a primary diagnosis of anxiety disorder; the review included 38 studies with a total of 3214 participants.

To be included in the review, studies had to be randomized, controlled, in adults over 18 years of age with a primary diagnosis of anxiety disorder; the review included 38 studies with a total of 3214 participants.

What does the evidence from this review tell us?

Physician-assisted I-CBT was significantly more effective than no treatment (waiting list) in relieving anxiety and symptoms. The quality of the evidence was very low to moderate.

There was no significant difference in the effectiveness of I-CBT with physician support and unsupported CBT, although the quality of the evidence was very low. Patient satisfaction was reported to be generally higher with physician-assisted I-CBT, but patient satisfaction was not formally assessed.

Physician-assisted I-CBT may not be as effective as face-to-face CBT. The quality of the evidence was low.

There was a low risk of bias in the included studies, except for blinding participants, staff, and raters (outcome raters).