Can you have tics with adhd

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Co-Occurring Tics

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and tic disorders often co-occur. They also often emerge during childhood. They are common, but general pediatricians who report competence in their clinical management of patients with ADHD are sometimes confused by lingering controversy over appropriate clinical management when these patients also have, or later develop, tics. Particular concern often stems from the apprehension that use of stimulant medications in treating ADHD will cause or exacerbate tics. Consequently, these children may not be adequately treated, jeopardizing optimal social and academic outcomes.

ADHD and tics: Clinical relationships

Jacob is an 8-year-old with ADHD-combined type diagnosed a year ago by his primary care provider. Since then, Jacob’s parents have opted to “wait and see” before starting any medication treatment. Beginning 1 month ago, Jacob began frequent eye blinking.

Tic disorders affect up to 20% of all children at some time.1 For most such children, tics are mild in severity and simple in complexity (eg, isolated to muscle groups or body regions and appear not to mimic purposeful movements or spoken language). The tics often go unnoticed and resolve within a year of onset.

In contrast, chronic tic disorders, including chronic motor or vocal tic disorder and Tourette disorder (chronic motor and vocal tic disorder, also known as Tourette syndrome), last more than a year2 and are less common, affecting about 1% of all children.3

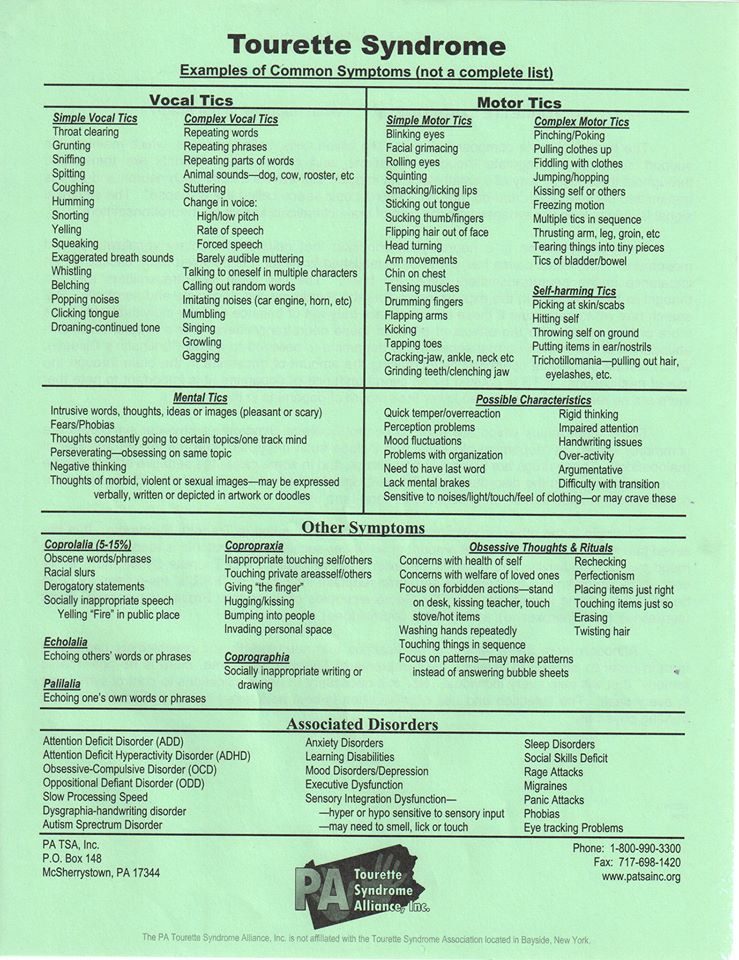

Chronic tic disorders usually persist beyond the first decade and often into adulthood, customarily reaching peak clinical severity when the patient is aged between 10 and 12 years,4 with symptoms naturally waxing and waning over time. Chronic tics are often simple but may also be complex (Table 1).2 All tics are stereotyped to the patient, which means that the affected person performs the tics again and again in a repeated, similar way.

ADHD and tics commonly co-occur

Children with ADHD are even more likely than unaffected children to have tics, and up to 20% of children diagnosed with ADHD will develop a chronic tic disorder.5 Conversely, half or more of children diagnosed with Tourette disorder are found also to have ADHD.6 Signs of ADHD typically emerge before the onset of tics.

Although the respective diagnostic features of ADHD and tic disorders differ, there are some important overlapping phenomena that may help to explain their frequent co-occurrence and guide management. Most specifically, impulsive actions in ADHD (sudden and unpremeditated, unfiltered behaviors often prompted by a sense of urgency) and tics (sudden stereotyped movements or noises usually prompted by unpleasant warning sensations) may suggest a neural circuitry “disinhibition,” or release, of undesired patterns of behavior linked to emotion, sensation, movement, and cognition.

The physiologic model of disinhibition centers largely on dysfunction in monoamine neurotransmitter systems in communications among the basal ganglia, the frontal and other cortex regions, and the thalamus. 7 The mechanism has not been fully characterized, but ongoing epidemiologic, pathophysiologic, and genetic investigations support the relationship between ADHD and tics, as well as other related neurodevelopment disorders of disinhibition including obsessions and compulsions, anxiety, and “rage” attacks.7-9

7 The mechanism has not been fully characterized, but ongoing epidemiologic, pathophysiologic, and genetic investigations support the relationship between ADHD and tics, as well as other related neurodevelopment disorders of disinhibition including obsessions and compulsions, anxiety, and “rage” attacks.7-9

Conditions associated with co-occurring ADHD and tics

Henry is an 11-year-old diagnosed with ADHD and Tourette disorder whose ADHD symptoms are treated with methylphenidate and behavior-management support. Henry has performed well academically and socially, but for the past 2 weeks, he refuses to go to school. His mother states that Henry seems unusually fretful and has become caught up in peculiar rituals, including “counting and checking everything” over and over.

Both ADHD and tics each place the affected children, adolescents, and adults at risk for psychosocial and neurodevelopment challenges.10 Most often, however, those with co-occurring ADHD and tics have greater functional and quality-of-life impairment than do those solely with tic disorders. 11 Therefore, clinicians must be alert to this heightened challenge and include a focus on ADHD when considering evaluation and management.

11 Therefore, clinicians must be alert to this heightened challenge and include a focus on ADHD when considering evaluation and management.

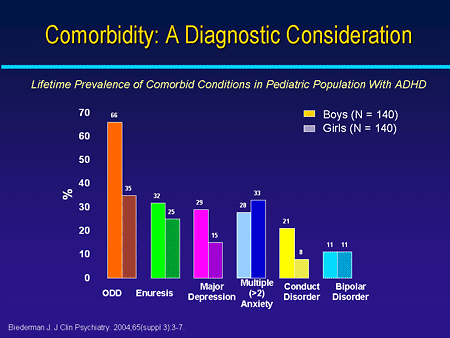

Children with co-occurring ADHD and Tourette disorder show poorer social adaptation and are more likely to be bullied than those who have Tourette disorder alone and to have cognitive and other neuropsychiatric impairments.12-15 Dual-affected children are more prone than children with Tourette disorder alone to have anxiety and depression and to display greater maladaptive behaviors, including aggression and delinquency.9,16,17 In adolescence and continuing into adulthood, internalizing behaviors and disorders such as depression, anxiety, and social withdrawal predominate over externalizing behaviors, and obsessions and compulsive behaviors often emerge or intensify in both groups.18,19

In addition, adults with co-occurring ADHD and Tourette disorder are more prone than those with Tourette disorder alone to maladaptive behaviors. 18 Thus, because there are significant challenges when ADHD co-occurs with tics, clinicians should consider all potentially helpful avenues; 1 such avenue is stimulant medication.

18 Thus, because there are significant challenges when ADHD co-occurs with tics, clinicians should consider all potentially helpful avenues; 1 such avenue is stimulant medication.

Stimulant use in co-occurring ADHD and tics

Samantha is a 6-year-old diagnosed last month with ADHD, and shortly thereafter a low-dose trial of short-acting methylphenidate was begun. Within days, her mother and her kindergarten teacher noticed Samantha nodding her head repeatedly at irregular times. Samantha’s mother has heard from a neighbor that methylphenidate causes tics.

Historical concern

Families of children with co-occurring ADHD and tic disorders may have questions or strong concerns about psychotropic medications and about stimulant medications in particular. The popular lay and professional impression that stimulants cause or exacerbate tics is mostly untrue, and historical context along with recognition of some physiologic principles shed light on the basis of this misunderstanding.

Stimulants are believed to act beneficially in treating ADHD in large part by increasing dopamine activity, whereas excessive transmission of this monoamine is believed to cause or contribute to tics. Currently, the most effective medication treatments for reducing tics work by reducing the neurotransmission of the monoamine dopamine.5 Several uncontrolled case reports and case series in the 1960s to the early 1980s, generally based on retrospective chart reviews, noted associations of stimulant medication use and subsequent tic onset or exacerbation.5,12 Ultimately, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) required that package inserts contraindicate the use of methylphenidate in patients with preexisting tic disorders or who have a family history of Tourette disorder, and for the use of amphetamines, a warning/precaution is provided.20

Stimulants are unlikely to cause or exacerbate tics

Beginning in the 1980s, a series of prospective studies adhering to rigorous, well-controlled, standard scientific design examined this issue. Despite the conventional and generally unchallenged assumptions of a stimulant-tic association, the results of these studies nearly universally failed to find a reliable association.21 These surprising findings ushered in our contemporary understanding that stimulants are very unlikely to evoke or exacerbate tics and are now a primary option in managing ADHD in patients with or predisposed to tic disorders.

Despite the conventional and generally unchallenged assumptions of a stimulant-tic association, the results of these studies nearly universally failed to find a reliable association.21 These surprising findings ushered in our contemporary understanding that stimulants are very unlikely to evoke or exacerbate tics and are now a primary option in managing ADHD in patients with or predisposed to tic disorders.

Evaluating ADHD in children with co-occurring tics

Gather information

Assessment for ADHD and tics is guided by careful attention to medical, neurodevelopment, and family histories; psychosocial influences, including parenting style, temperament, and academic performance; and completion of a physical examination, with heightened attention to neurologic elements.

A standard approach to evaluation, diagnosis, and management is warranted in all children who are suspected to have ADHD whether co-occurring tics are present. The paradigm that ADHD is a diagnosis of exclusion holds: Carefully identify other potential sources of inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity that may mimic and/or exacerbate ADHD, including obsessions and compulsions, learning disabilities, anxiety, mood disorders, or somnolence. 22

22

Tic history

Any diagnostic uncertainty regarding tics requires appropriate evaluation to clarify. Many children and nearly all adolescents with tics can identify the presence of an involuntary, unpleasant, or distracting premonitory sensation that is unique to each tic type. This alerting sensory phenomenon is experienced as an urge and is specific to tics, often likened to a feeling of pressure, tension, or itch. The sensation is reduced or eliminated, temporarily, by committing the semivoluntary tic. The awareness of this sensation is virtually pathognomonic for tics.

At the time of tic onset, it’s not possible to predict whether tics will follow a brief course (as is true for most children who develop tics) or will instead persist beyond 1 year to become a chronic tic disorder. Other unknowns include the anticipated complexity, interference, or number of eventual tic types.

Particular attention to tics and their perceived influences on core features of ADHD behaviors is paramount. Frequent varied minor tics (eye blinking, shoulder shrugging, arm thrusting, or abdominal tensing) or bouts of a single tic type may be confused as fidgetiness or hyperactivity.23 A child’s attempts to suppress tics can exacerbate ADHD symptoms by increasing emotional tension or by distracting the child.

Frequent varied minor tics (eye blinking, shoulder shrugging, arm thrusting, or abdominal tensing) or bouts of a single tic type may be confused as fidgetiness or hyperactivity.23 A child’s attempts to suppress tics can exacerbate ADHD symptoms by increasing emotional tension or by distracting the child.

When considering tics among children diagnosed with ADHD, determine who is raising behavioral concerns and delineate what his or her concerns are. The perspectives of the importance and interference of tic behaviors likely vary across social circumstances and across persons. Because media portrayals of Tourette disorder often feature only very severe, unflattering, or exaggerated clinical examples, it’s often useful to ask families about their understanding of tic disorders to ascertain any misconceptions or specific worries.

Comorbid conditions

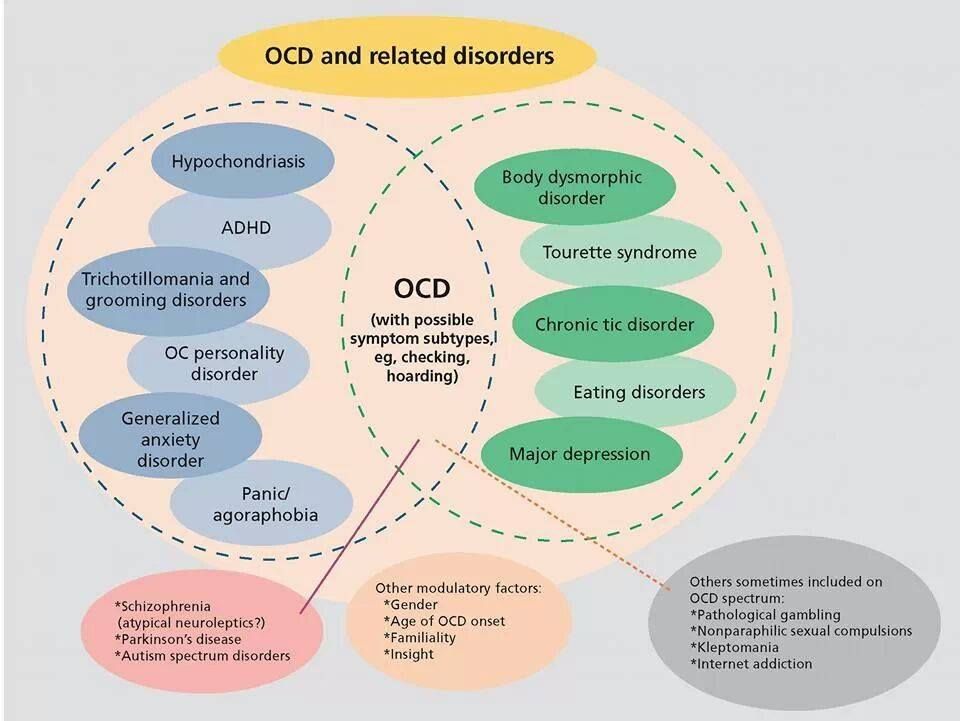

Particular mention of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and related anxiety disorders is critical to understanding the clinical complexity of tic disorders in children. Although children with ADHD only are susceptible to anxiety disorders, those who also have co-occurring chronic tic disorders are much more highly susceptible to having OCD and may also be more susceptible to generalized anxiety disorder than those with ADHD only.

16 To complicate matters, those who also have anxiety disorders are additionally at increased risk for depression.

Although children with ADHD only are susceptible to anxiety disorders, those who also have co-occurring chronic tic disorders are much more highly susceptible to having OCD and may also be more susceptible to generalized anxiety disorder than those with ADHD only.

16 To complicate matters, those who also have anxiety disorders are additionally at increased risk for depression.

Clinicians should be aware of other frequent co-occurring conditions such as aggression, oppositional behavior, mood disorders,22 specific learning disabilities, and sleep disturbances, each of which may impart additional behavior and psychosocial burden and may aggravate or mimic signs and symptoms of ADHD and require appropriate screening, monitoring, and management.

Once a comprehensive evaluation has been completed and an initial determination of co-occurring conditions with other influences identified, priority in management usually should be directed to ADHD and, when present, to OCD and other anxiety disorders, rather than to tics. Effective treatments of these conditions may also secondarily reduce tic severity, because improvement in mental focus and attention may enable better social participation and reduced stress and less distraction or worry. At that point, tic severity can be reassessed.22 In rare exceptions, children whose tics cause intense interference or pain or that threaten self-injury require more immediate intervention targeting tic reduction.

Effective treatments of these conditions may also secondarily reduce tic severity, because improvement in mental focus and attention may enable better social participation and reduced stress and less distraction or worry. At that point, tic severity can be reassessed.22 In rare exceptions, children whose tics cause intense interference or pain or that threaten self-injury require more immediate intervention targeting tic reduction.

Managing ADHD in children with co-occurring tics

Family, education, and community focus

Early identification of tics among children with ADHD may provide the ounce of prevention needed to offset later diagnostic confusion, shame, or blame in child behavior. By providing accurate information, resources, and reassurance about tic disorders to families and by anticipating and responding to families’ questions or fears, clinicians often can then manage tics with families by monitoring the symptoms over time without more specific intervention.

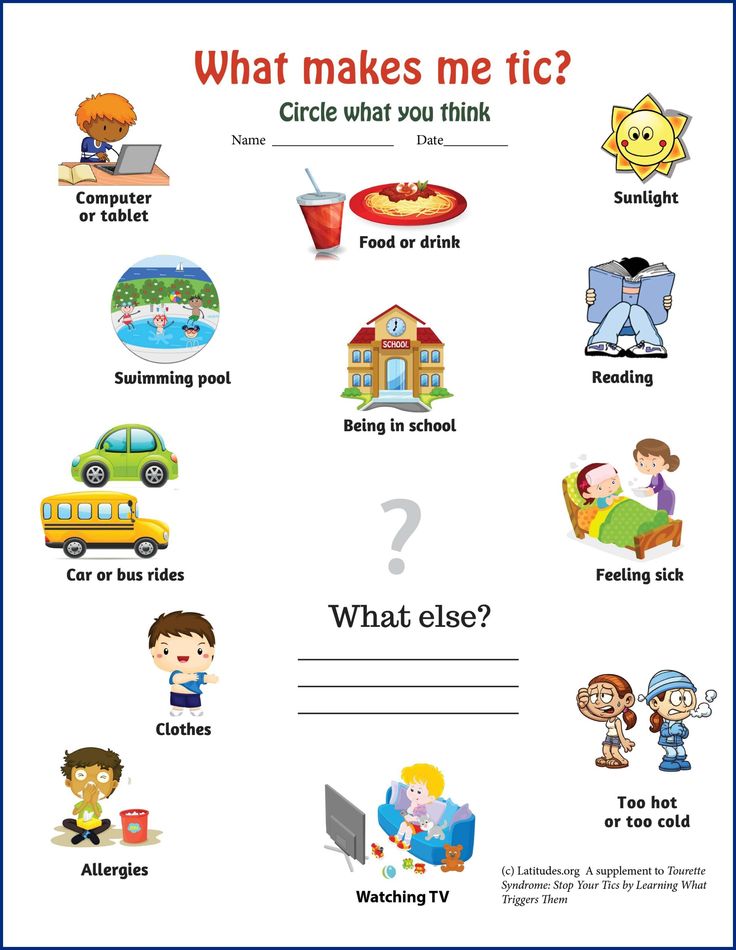

Chronic tics naturally wax and wane over periods of minutes, days, weeks, and months, and their expressions are also heavily influenced by psychosocial stress, fatigue, prolonged attempts to suppress tics, and other variables. Anxiety states, in particular, frequently exacerbate tic severity. Although an initial comprehensive evaluation may not reveal other co-occurring behavior or development concerns, such conditions may evolve over time and should be monitored and screened periodically.

Ideally, a family-centered management approach elicits prosocial communication and understanding among its members. Many neurodevelopment conditions are highly heritable, so that commonly 1 or both parents or siblings of affected children also have related neurodevelopment challenges.18,24 Building positive parenting strategies that take into account surrounding impatience, anger, guilt, or misunderstanding may be central to effective management.

The primary care provider can help to educate families regarding legally available accommodations to qualified children with ADHD or Tourette disorder whose conditions result in special education needs (via the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act) or restrict equal access within the public school (via Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act).

Providers can and should encourage families to contact regional chapters of national agencies that are invested in supporting families and health care providers in their shared efforts to learn about ADHD and about tic disorders. In particular, the Tourette Syndrome Association (www.tsa-usa.org) and Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (www.chadd.org) provide evidence-based information on issues of self-advocacy, special education, and medical care (Table 2).

Stimulants

A multimodal approach is optimal in the treatment of ADHD, and when inclusion of medication is indicated, psychostimulants have the proven best short-term efficacy.25 Although data are less clear regarding which medications show superiority when ADHD co-occurs with tics,21 results from well-designed, placebo-controlled studies are clear that stimulant medications are unlikely either to exacerbate tics or to evoke tics among patients who are predisposed. 26

26

Families should understand that if they do observe tic severity to increase after initiation of stimulant medication, they could suspend medication use and consider reintroducing stimulants at a later time or consider alternative medication and other management strategies.12

Because the symptoms of ADHD are usually the most problematic, the priority will often begin with ADHD management.21 Methylphenidate has been investigated more closely than amphetamines in treating ADHD in patients with co-occurring tics, so it’s reasonable to consider methylphenidate first when choosing to use a stimulant medication in these patients. Advantages to stimulant medications include their fast-acting property and their superior profile in treating the core features of ADHD. There is some, albeit limited, evidence that stimulants may even modestly improve tic symptom severity and reduce oppositional behaviors, when such behaviors are part of the symptom profile. 21

21

As a rule of thumb, begin with a low dose of a short-acting stimulant preparation. This approach reduces adverse-effect risks, allows more immediate discontinuation if necessary, and enhances titration control. Switch to a long-acting preparation if a stimulant proves effective and tolerable. If a stimulant proves ineffective and/or intolerable, consider a different stimulant (eg, amphetamine), an alternative class of medication, or the addition of an α2 adrenergic agonist. Care must be taken in using stimulants in patients with co-occurring anxiety disorders because stimulants can exacerbate anxiety, which can secondarily exacerbate tics.

Prescribing clinicians who recommend stimulants are obligated to provide families with a clear and reasonable response to the FDA contraindication to using stimulants in predisposed patients, as well as to discuss all other customary risks regarding the use of stimulants (eg, initial insomnia, appetite suppression, stomach upset, headache, dizziness). If medication is prescribed, routine cardiovascular, growth, and other customary monitoring are required.

If medication is prescribed, routine cardiovascular, growth, and other customary monitoring are required.

Nonstimulant medication

Sometimes tics pose equal or more severe problems than do ADHD symptoms, particularly if tics are very frequent, embarrassing, or result in discomfort or (rarely) in mild self-injury. For such affected patients, the α2 adrenergic agonists clonidine and guanfacine may be preferred first agents. Their advantages to stimulants in these patients include more likely reduction in tics of mild to moderate severity as well as amelioration of hyperactivity and impulsive tendencies in ADHD. In addition, these agents can assist in reducing the difficulty with sleep initiation that frequently co-occurs in these children.27

The addition of melatonin may further enhance sleep initiation. In contrast to the stimulants that take effect within hours or days of initiation, the beneficial effects of α2 adrenergic agonists generally take weeks before improvement is seen. Families should be alerted to this latency in effect to help them maintain compliance and reduce frustration.

Families should be alerted to this latency in effect to help them maintain compliance and reduce frustration.

The combined use of a stimulant and an α2 adrenergic agonist may also be considered, usually after 1 or both agents are first tried alone, to enhance likelihood of therapeutic effect. The combination is generally well tolerated.26 An additional potential advantage is that when these agents are used together, their respective effects may help diminish each other’s adverse effects on states of insomnia/sedation.5

Although investigation of atomoxetine is very limited in this population, available good-quality evidence supports the selection of atomoxetine for patients among whom neither stimulants nor α2 adrenergic agonists, singly or in combination, prove satisfactory. Its potential benefits include improvement of ADHD symptoms and of tic symptoms, but further research is needed.28

Desipramine also has undergone very limited investigation for this purpose but has been shown to be of possible benefit in treating both ADHD and tics. 29 However, because use of desipramine poses risk of serious cardiac effect, including sudden death, desipramine is not first-line treatment, and consulting with a child psychiatrist and/or completing a full cardiac workup is indicated before initiating this medication (Figure; Table 3).5,30,31

29 However, because use of desipramine poses risk of serious cardiac effect, including sudden death, desipramine is not first-line treatment, and consulting with a child psychiatrist and/or completing a full cardiac workup is indicated before initiating this medication (Figure; Table 3).5,30,31

Key treatment points to remember

Co-occurring ADHD and tic disorders, including Tourette disorder, are common. Both conditions place affected children at risk for challenges in emotional, behavioral, cognitive, and health functions, although effective ADHD management most often demands initial priority. Concerns about tic exacerbation from use of stimulant medication in patients with or at increased risk for tic disorders have proven largely unfounded.

Optimal ADHD management usually relies on inclusion of psychotropic medications, with educational and psychosocial support, and among medication options, the stimulants are usually well tolerated and most effective. Families should be appropriately informed of the limited relationship between stimulant medications and tics and that ongoing monitoring will be ensured. Patients with chronic tic disorders are also at increased risk to have or later develop anxiety disorders, including OCD. For these patients, nonstimulant medication options may target symptoms of anxiety, ADHD, and tics, as part of a comprehensive management approach.

Families should be appropriately informed of the limited relationship between stimulant medications and tics and that ongoing monitoring will be ensured. Patients with chronic tic disorders are also at increased risk to have or later develop anxiety disorders, including OCD. For these patients, nonstimulant medication options may target symptoms of anxiety, ADHD, and tics, as part of a comprehensive management approach.

References

1. Kurlan R, McDermott MP, Deeley C, et al. Prevalence of tics in schoolchildren and association with placement in special education. Neurology. 2001;57(8):1383-1388.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

3. Kraft JT, Dalsgaard S, Obel C, Thomsen PH, Henriksen TB, Scahill L. Prevalence and clinical correlates of tic disorders in a community sample of school-age children. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;21(1):5-13.

2012;21(1):5-13.

4. Bloch MH, Leckman JF. Clinical course of Tourette syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67(6):497-501.

5. Bloch MH, Panza KE, Landeros-Weisenberger A, Leckman JF. Meta-analysis: treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children with comorbid tic disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(9):884-893.

6. Freeman RD; Tourette Syndrome International Database Consortium. Tic disorders and ADHD: answers from a world-wide clinical dataset on Tourette syndrome. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;16(suppl 1):15-23. Erratum in: Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;16(8):536.

7. O’Rourke JA, Scharf JM, Platko J, et al. The familial association of Tourette’s disorder and ADHD: the impact of OCD symptoms. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2011;156B(5):553-560.

8. Stewart SE, Illmann C, Geller DA, Leckman JF, King R, Pauls DL. A controlled family study of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and Tourette’s disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(11):1354-1362.

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(11):1354-1362.

9. Rizzo R, Curatolo P, Gulisano M, Virzì M, Arpino C, Robertson MM. Disentangling the effects of Tourette syndrome and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder on cognitive and behavioral phenotypes. Brain Dev. 2007;29(7):413-420.

10. Conelea CA, Woods DW, Zinner SH, et al. Exploring the impact of chronic tic disorders on youth: results from the Tourette Syndrome Impact Survey. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2011;42(2):219-242.

11. Eddy CM, Cavanna AE, Gulisano M, et al. Clinical correlates of quality of life in Tourette syndrome. Mov Disord. 2011;26(4):735-738.

12. Erenberg G. The relationship between Tourette syndrome, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and stimulant medication: a critical review. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2005;12(4):217-221.

13. Zinner SH, Conelea CA, Glew GM, Woods DW, Budman CL. Peer victimization in youth with Tourette syndrome and other chronic tic disorders. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2012;43(1):124-136.

Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2012;43(1):124-136.

14. Debes N, Hjalgrim H, Skov L. The presence of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and obsessive-compulsive disorder worsen psychosocial and educational problems in Tourette syndrome. J Child Neurol. 2010;25(2):171-181.

15. Sukhodolsky DG, Landeros-Weisenberger A, Scahill L, Leckman JF, Schultz RT. Neuropsychological functioning in children with Tourette syndrome with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(11):1155-1164.

16. Schneider J, Gadow KD, Crowell JA, Sprafkin J. Anxiety in boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with and without chronic multiple tic disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(6):737-748.

17. Cohen E, Sade M, Benarroch F, Pollak Y, Gross-Tsur V. Locus of control, perceived parenting style, and symptoms of anxiety and depression in children with Tourette’s syndrome. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;17(5):299-305.

2008;17(5):299-305.

18. Haddad AD, Umoh G, Bhatia V, Robertson MM. Adults with Tourette’s syndrome with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;120(4):299-307.

19. Roessner V, Becker A, Banaschewski T, Freeman RD, Rothenberger A; Tourette Syndrome International Database Consortium. Developmental psychopathology of children and adolescents with Tourette syndrome-impact of ADHD. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;16(suppl 1):24-35. Erratum in: Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;16(8):536.

20. Physicians’ Desk Reference. 67th ed. Montvale, NJ: PDR Network; 2012.

21. Pringsheim T, Steeves T. Pharmacological treatment for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children with comorbid tic disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(4):CD007990.

22. Gaze C, Kepley HO, Walkup JT. Co-occurring psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents with Tourette syndrome. J Child Neurol. 2006;21(8):657-664.

J Child Neurol. 2006;21(8):657-664.

23. Taylor E. Sleep and tics: problems associated with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(9):877-878.

24. Mathews CA, Grados MA. Familiality of Tourette syndrome, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: heritability analysis in a large sib-pair sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(1):46-54.

25. Van der Oord S, Prins PJ, Oosterlaan J, Emmelkamp PM. Efficacy of methylphenidate, psychosocial treatments and their combination in school-aged children with ADHD: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28(5):783-800.

26. Tourette’s Syndrome Study Group. Treatment of ADHD in children with tics: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2002;58(4):527-536.

27. Robertson MM. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, tics and Tourette’s syndrome: the relationship and treatment implications. A commentary. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;15(1):1-11.

2006;15(1):1-11.

28. Spencer TJ, Sallee FR, Gilbert DL, et al. Atomoxetine treatment of ADHD in children with comorbid Tourette syndrome. J Atten Disord. 2008;11(4):470-481.

29. Spencer T, Biederman J, Coffey B, et al. A double-blind comparison of desipramine and placebo in children and adolescents with chronic tic disorder and comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(7):649-656.

30. Roessner V, Plessen KJ, Rothenberger A, et al; ESSTS Guidelines Group. European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders. Part II: pharmacological treatment. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20(4):173-196.

31. Scahill L, Erenberg G, Berlin CM Jr, et al; Tourette Syndrome Association Medical Advisory Board; Practice Committee. Contemporary assessment and pharmacotherapy of Tourette syndrome. NeuroRx. 2006;3(2):192-206.â¨

ADHD and Tics or Tourette Syndrome

Tourette Syndrome and ADHD frequently co-occur. More than half of children with TS also have ADHD. About one in five children with ADHD also have TS or persistent tic disorders.

More than half of children with TS also have ADHD. About one in five children with ADHD also have TS or persistent tic disorders.

Symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, impulsivity, and tics can affect children’s lives at home, at school, or with friends. When a child has both ADHD symptoms and tics, it’s important that their health care provider carefully assess all symptoms and provide a comprehensive diagnostic evaluation, so that both conditions can be included in multimodal treatment planning.

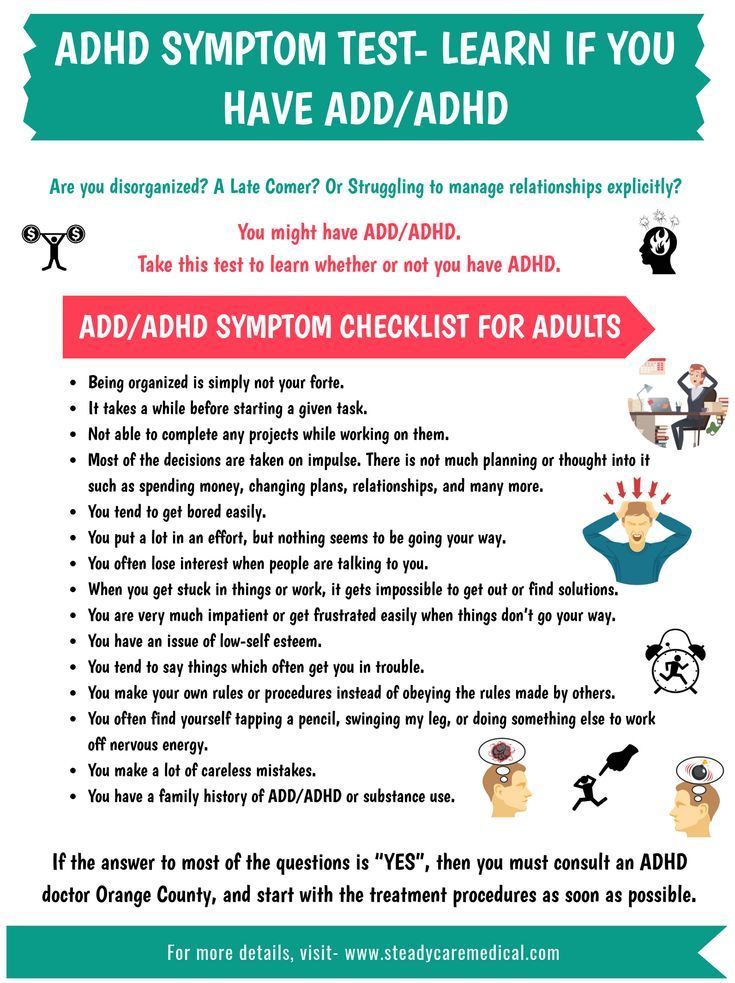

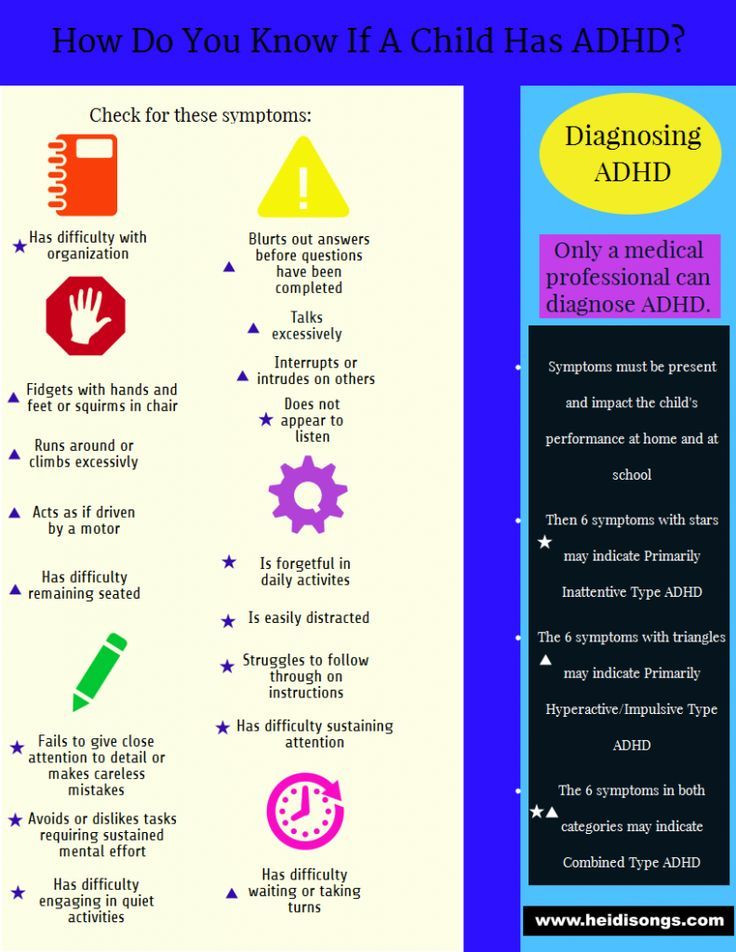

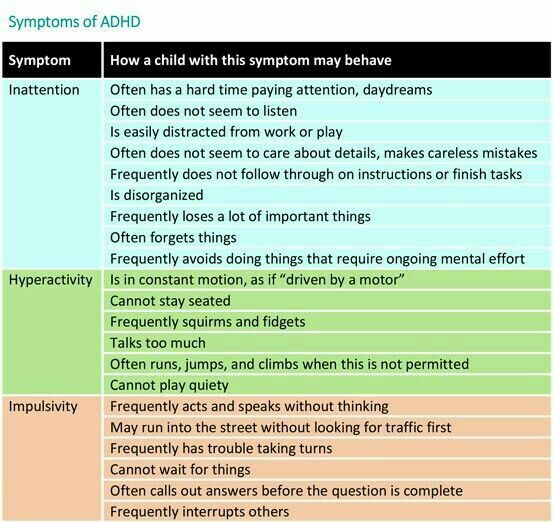

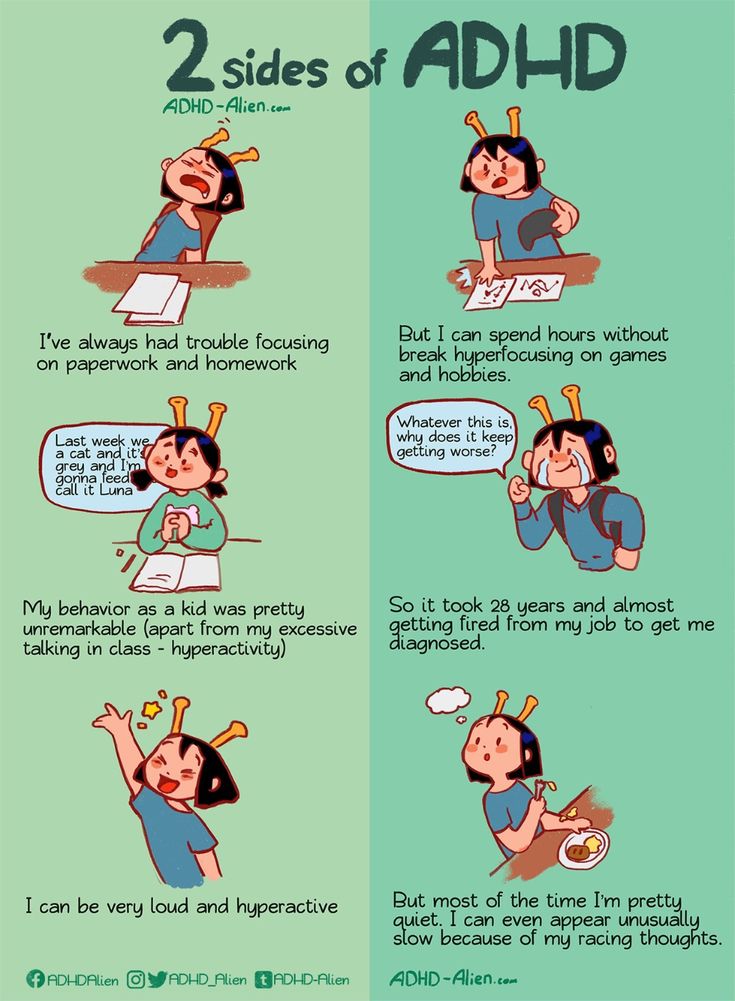

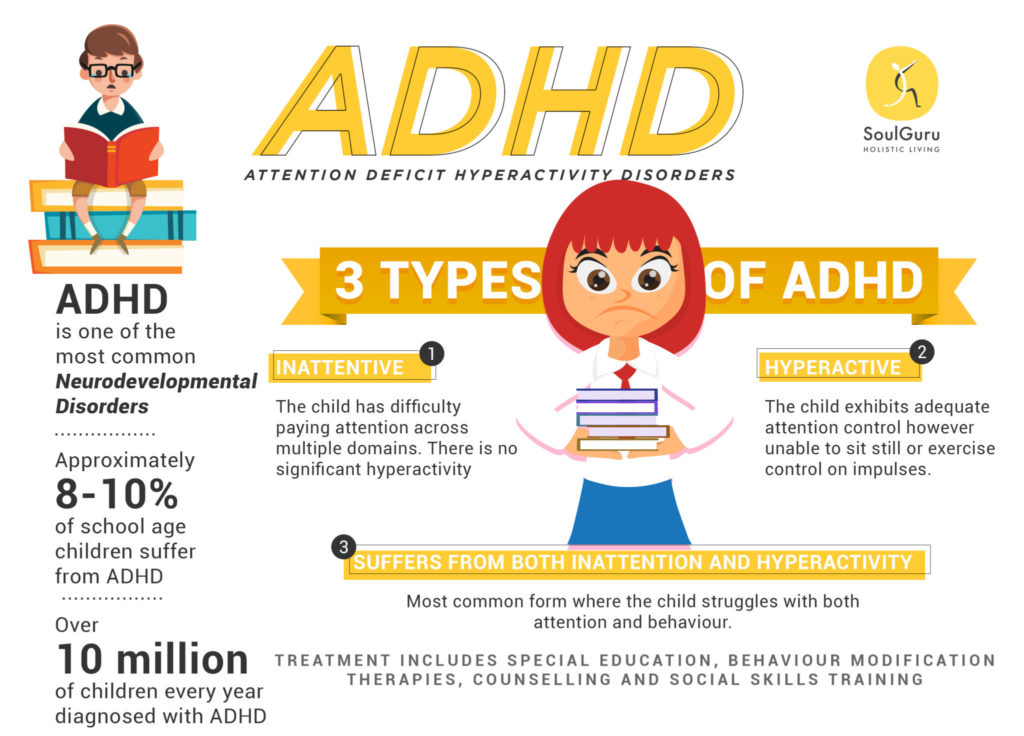

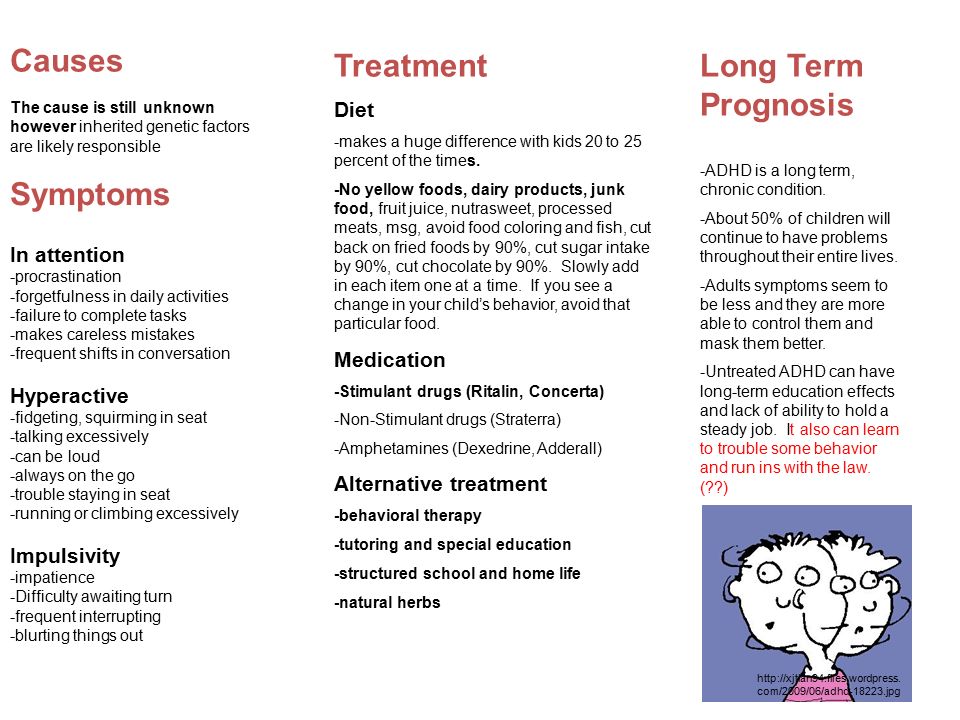

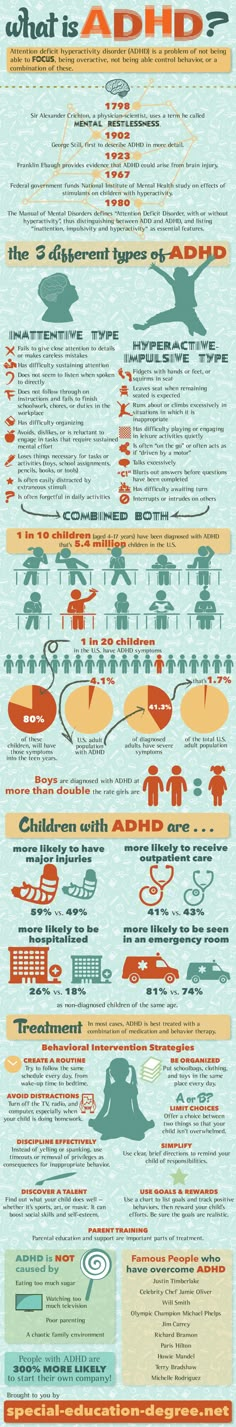

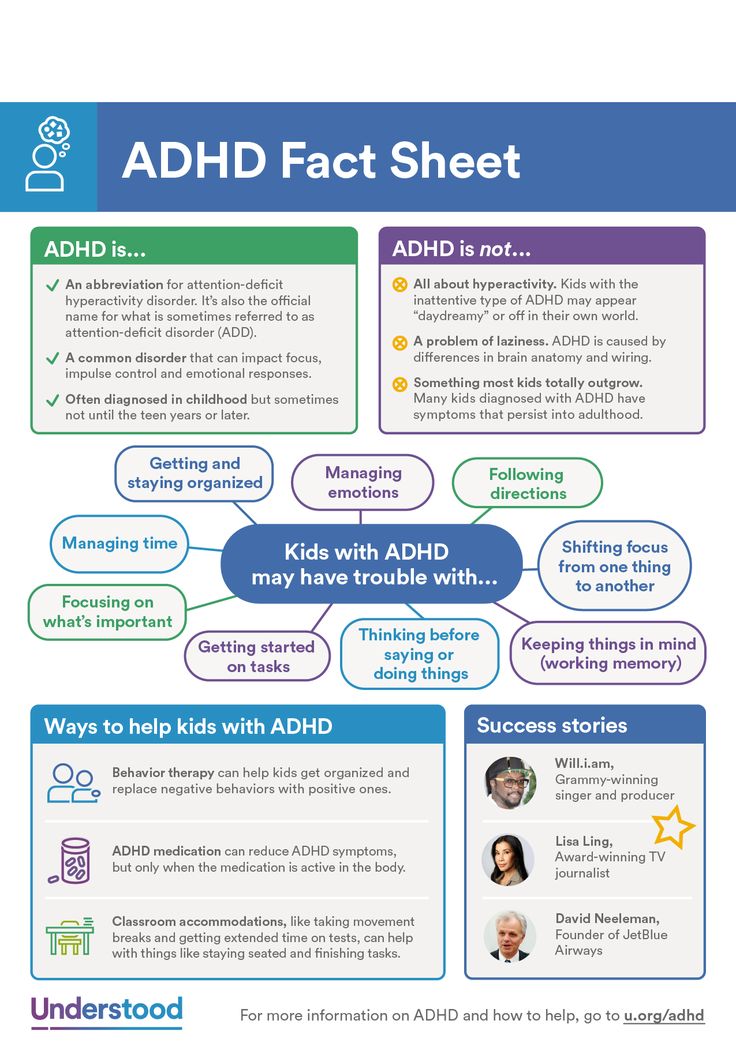

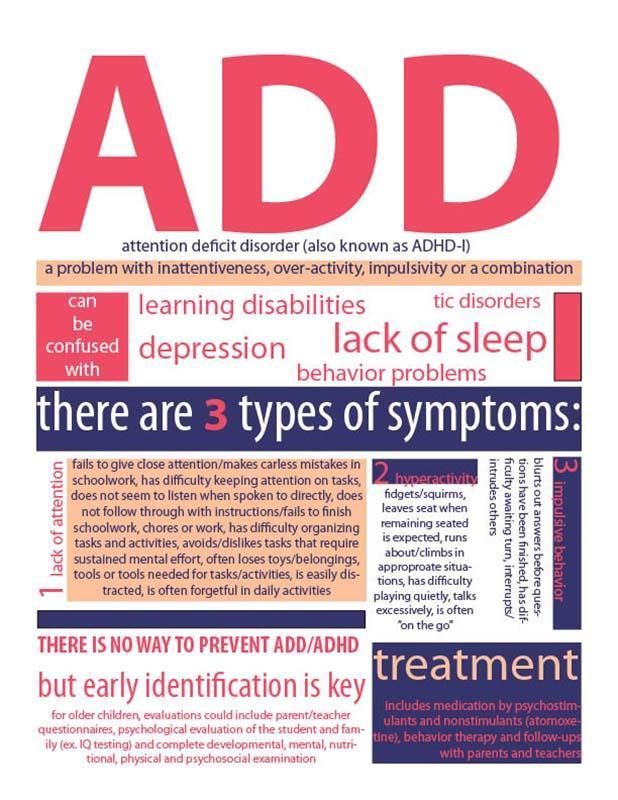

ADHD: Symptoms

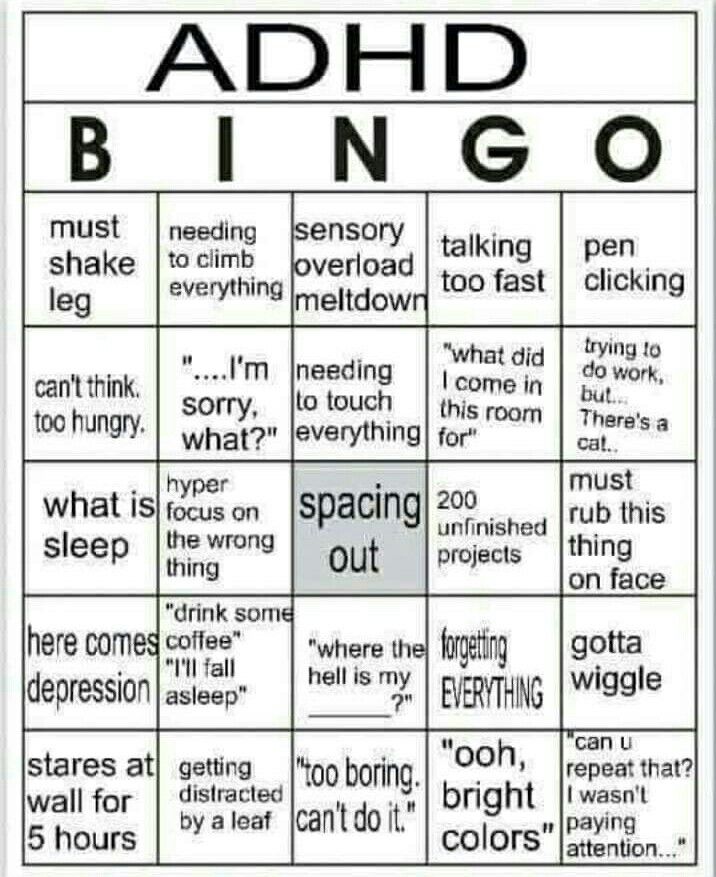

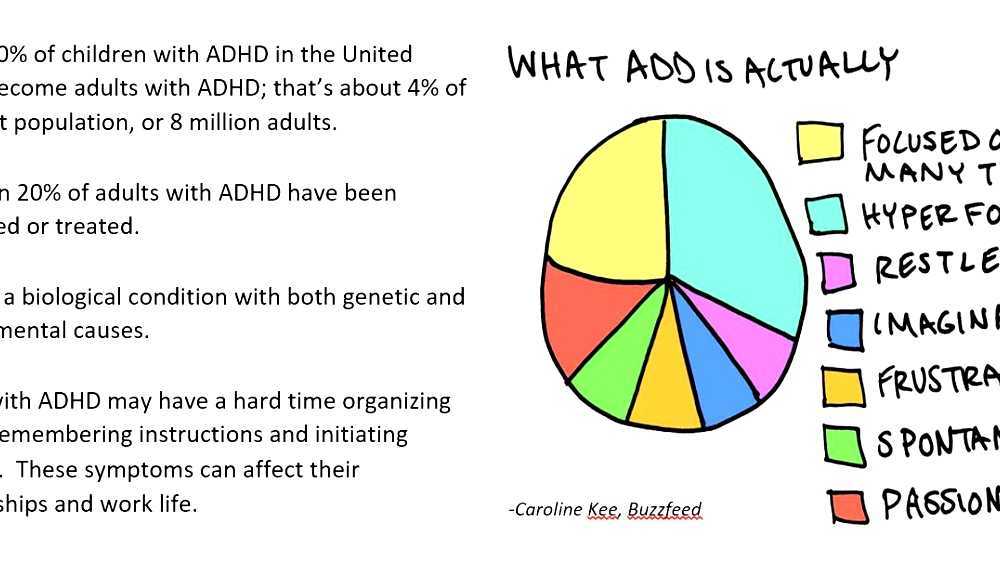

ADHD is a brain-based disorder that can cause one to feel a constant need to move around and to experience difficulties with focus, concentration, and executive function—the ability to organize, plan, and manage thoughts and actions. Its symptoms are usually first noticed in early childhood and fall into three groups of behaviors: inattentive, hyperactive-impulsive, and combined inattention and hyperactivity.

Inattentive symptoms include failing to pay attention to details, making careless mistakes, difficulty sustaining attention, not appearing to listen, struggling to follow instructions, difficulty with organization, avoiding or disliking tasks that require sustained mental effort, losing things, and being easily distracted and forgetful.

Hyperactive-impulsive symptoms include fidgeting, difficulty remaining seated, running about excessively, difficulty engaging in activities quietly, acting as if driven by a motor, talking excessively, blurting out answers, difficulty waiting or taking turns, and interrupting others.

Symptoms can present in different ways: predominantly inattentive, predominantly hyperactive-impulsive, and combined presentation with both inattentive and hyperactive-impulsive symptoms.

ADHD: Diagnosis

To meet diagnostic criteria for ADHD, symptoms must be present before the age of 12. Children need to have six or more ADHD symptoms in two or more settings. For adolescents and adults aged 17 or older, five symptoms are sufficient for a diagnosis.

ADHD can be a lifelong health condition, but symptoms and presentations can change and fluctuate; hyperactive symptoms typically lessen over time, but a sense of restlessness may remain in adults. Other health conditions, such as anxiety, depression, behavior disorders, learning, and sleep disorders, often co-occur with ADHD. The specific causes of ADHD have not yet been identified, but genetic inheritance, low levels of neurotransmitters and dysfunction between the front portion of the brain with the motor and cognitive centers of the brain have been shown to be involved. ADHD tends to run in families.

The specific causes of ADHD have not yet been identified, but genetic inheritance, low levels of neurotransmitters and dysfunction between the front portion of the brain with the motor and cognitive centers of the brain have been shown to be involved. ADHD tends to run in families.

Tic Disorders and Tourette Syndrome: What is a Tic?

Tics are sudden, rapid, repetitive, non-rhythmic movements or sounds. These actions are involuntary, in that an individual may be able to suppress them for a short time, but ultimately has no control over them. Tics are common in childhood and stop before adulthood for most people. Boys are three time as likely to have tics as girls.

Tics are described as being either simple or complex. Simple tics can be brief, happen quickly, and involve a single muscle group. Complex tics last longer, involve more muscles, and often include a series of simple tics that occur together in a sequence.

Motor tics may include eye blinking, mouth opening, facial grimacing, head movements, shoulder shrugging, or combinations of any of these movements. Vocal tics may include throat clearing, coughing, sniffing, barking, snorting, repeating parts of words or phrases, or, more rarely, blurting obscene or inappropriate words.

Vocal tics may include throat clearing, coughing, sniffing, barking, snorting, repeating parts of words or phrases, or, more rarely, blurting obscene or inappropriate words.

Tic Disorders and Tourette Syndrome: Diagnosis

Tic disorders are neurodevelopmental disorders, and symptom onset must occur before age 18 to meet diagnostic criteria. There are three types of tic disorders:

- provisional tic disorder (lasting less than a year)

- persistent (chronic) motor or vocal tic disorder (lasting a year or longer)

- Tourette Syndrome, also known as Tourette’s disorder (both motor and vocal tics, numerous and frequent, lasting more than a year)

TS can be a lifelong health condition, but tic symptoms fluctuate, and often improve in late adolescence and young adulthood. Other conditions besides ADHD can co-occur with TS, including anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), as well learning disorders and other developmental disabilities. As with ADHD, the cause of tics and TS has not yet been identified, but research has identified dysfunction/disinhibition of the brain circuits involved in the control of movement, cognition, and behavior (what researchers call the cortico-striatal-thalamo-cortical or CTSC pathway). Similarly, genetics are thought to play a role, and tics, TS, and OCD tend to run in families.

As with ADHD, the cause of tics and TS has not yet been identified, but research has identified dysfunction/disinhibition of the brain circuits involved in the control of movement, cognition, and behavior (what researchers call the cortico-striatal-thalamo-cortical or CTSC pathway). Similarly, genetics are thought to play a role, and tics, TS, and OCD tend to run in families.

ADHD Treatment

Treatment options for ADHD include medication, behavior therapy and training for parents, organizational skills training, school intervention, and accommodations. Medications fall into two larger categories: stimulant medication and nonstimulant medication. Behavior therapy teaches children and their families how to strengthen positive child behaviors and eliminate or reduce unwanted or problem behaviors. Parent behavior management training teaches parents to learn or improve skills to manage their child’s behavior. Parents are encouraged to practice the skills with their child during therapy sessions and at home. Teachers can also be trained in behavior management to help children at childcare centers or schools.

Teachers can also be trained in behavior management to help children at childcare centers or schools.

For children age 6 and older, ADHD is often best treated with a combination of behavior therapy and medication. For children with ADHD younger than age 6, behavior therapy, particularly parent training, is recommended as the first treatment before medication is tried.

You can learn more about treating childhood ADHD in CHADD’s Treatment Overview for Parents & Caregivers.

Tourette Syndrome and Other Tic Disorders: Treatment

Tics generally need treatment only if they are causing significant daily problems. Treatment options include behavioral interventions and medications. In mild cases, education and reassurance for the child and family may be all that is needed.

Comprehensive Behavioral Intervention for Tics, or CBIT, is the recommended first line of treatment for Tourette Syndrome. CBIT consists of three important components:

- Training the patient to become more aware of his or her tics in general, and in particular, to become aware of urges to tic before the tic occurs.

- Training the patient to perform a competing behavior when he or she feels the urge to tic.

- Making changes to day-to-day activities in ways that can be helpful in reducing tics.

Medication may also be prescribed when symptoms interfere with social relationships, daily life, or academic or job performance. Treatment options for tics can also include stress and anxiety management strategies, such as mindfulness, meditation, and deep breathing techniques. Occupational therapists can also provide assessments, therapies, and plans that can help manage the environment and reduce stress for children and teens if needed. School supports and academic accommodations can be put in place to help manage the impact of tic symptoms on learning and school success.

You can learn more about treatment for tic disorders, including CBIT, in Tourette Association’s Medical Treatments.

Combined Treatment for ADHD and Tics

When a child has both ADHD and tics, the healthcare provider evaluates which symptoms are causing the most difficulties for the child. The condition that is causing the most distress or impairment is generally treated first. Treatment for the second condition often begins after the first condition starts to improve. Sometimes it is necessary to start treatment for both conditions at the same time.

The condition that is causing the most distress or impairment is generally treated first. Treatment for the second condition often begins after the first condition starts to improve. Sometimes it is necessary to start treatment for both conditions at the same time.

Medication may be needed for children with ADHD and Tourette Syndrome. The provider may decide to treat mild symptoms of both ADHD and tics with an alpha agonist, a nonstimulant medication such as clonidine or guanfacine, which can reduce both symptoms. Their most common side effects are tiredness and fatigue.

If ADHD symptoms are the most problematic, then treatment with a stimulant medication is generally recommended. Stimulants are highly effective for all ADHD symptoms, including in children with ADHD and tics. Although there is no scientific evidence that stimulants increase tics in children with ADHD and tic disorders, some children may experience a temporary increase when stimulants are started or doses are increased. Recent studies report that short-term stimulant medication, especially methylphenidate (Ritalin, Concerta, Metadate), seems to be safe and well tolerated in children who have chronic tics or TS and co-occurring ADHD. Children who were given methylphenidate did not develop more frequent tics when compared with those who were not given the medication. Tics may be more likely to increase with the dextroamphetamines (Dexedrine, Adderall, Vyvanse, ProCentra) compared to methylphenidate. In the long run, ADHD symptoms can potentially cause more difficulty than tics in children with both conditions, so it is important to make sure that the ADHD is adequately treated.

Recent studies report that short-term stimulant medication, especially methylphenidate (Ritalin, Concerta, Metadate), seems to be safe and well tolerated in children who have chronic tics or TS and co-occurring ADHD. Children who were given methylphenidate did not develop more frequent tics when compared with those who were not given the medication. Tics may be more likely to increase with the dextroamphetamines (Dexedrine, Adderall, Vyvanse, ProCentra) compared to methylphenidate. In the long run, ADHD symptoms can potentially cause more difficulty than tics in children with both conditions, so it is important to make sure that the ADHD is adequately treated.

Behavior therapy, including parent training, can address both types of symptoms. CBIT training components that teach children about managing stress and anxiety, such as relaxation and mindfulness, can also help with ADHD symptoms. Parent training in behavior management focuses on positive communication, supportive routines and structures, and consistent positive discipline. The therapist can help parents understand how to best support the specific needs of their child, including the treatment of other behavioral, emotional, or learning disorders that may occur along with both ADHD and tic disorders.

The therapist can help parents understand how to best support the specific needs of their child, including the treatment of other behavioral, emotional, or learning disorders that may occur along with both ADHD and tic disorders.

References:

CDC. Data & Statistics on Tourette Syndrome: How many children have Tourette syndrome?

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Co-Occurring Tics. Contemporary Pediatrics, April 1, 2013.

CHADD NRC. ADHD Quick Facts: ADHD Presentations.

Barbaresi et al. (2020). The Society for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics Clinical Practice Guideline for the Assessment and Treatment of Children and Adolescents with Complex Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Process of Care Algorithms. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics: February/March 2020 - Volume 41 - Issue - p S58-S74.

Pringsheim et al. (2019). Practice guideline recommendations summary: Treatment of tics in people with Tourette syndrome and chronic tic disorders. Neurology: 92 (19).

Neurology: 92 (19).

The Tourette Association of America. What is Tourette.

The Tourette Association of America. How are TS and Other Tic Disorders Treated?

The Tourette Association of America. Comprehensive Behavioral Intervention for Tics (CBIT): Overview.

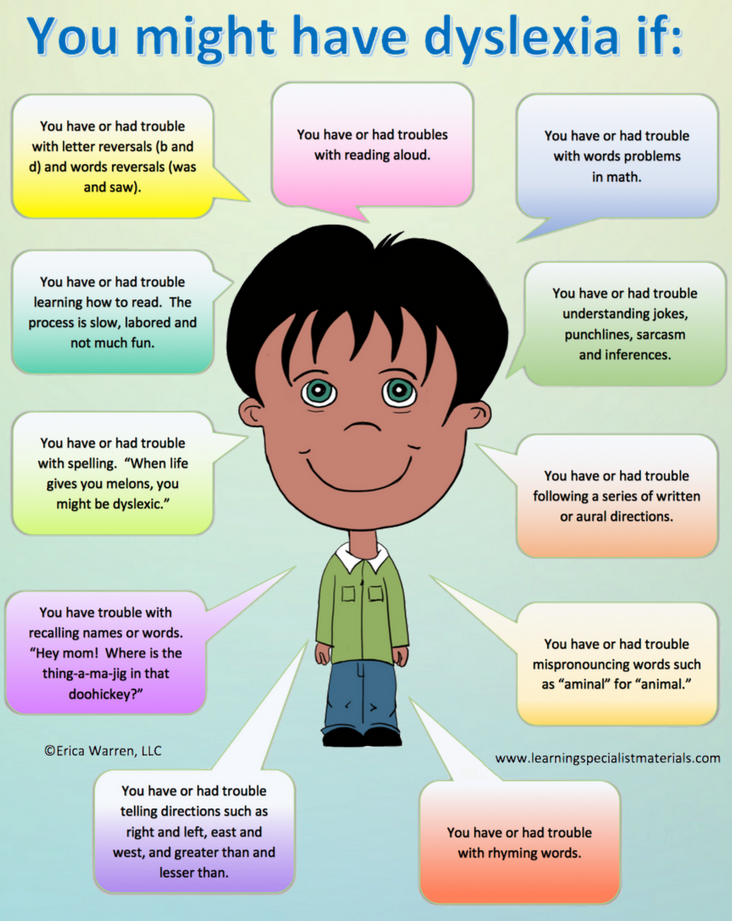

| And who knows why he blinks? Head of the Center for Neurotherapy of the Institute of the Human Brain of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Doctor of Medical Sciences, neurologist of the highest category, psychotherapist L.S. Chutko (St. Petersburg) (Specially for the site Our inattentive hyperactive children) A common reason for visiting a pediatric neurologist and psychotherapist is tics (tic hyperkinesis), which are sudden, involuntary, violent, jerky, repetitive movements. They usually occur between the ages of 5 and 8, and tics are 4 to 6 times more common in boys than in girls. Genetic and immune mechanisms, pathology of the period of pregnancy and childbirth, as well as psychosocial factors play a role in the origin of tics. You should always keep in mind the possibility of several factors affecting each other. Psychological factors (unfavorable family environment, separation from one of the parents as a result of family breakdown, bad relationships in the children's team) play the role of a provoking or reinforcing factor. In some children, the disease appears after the first days of school, against the background of school adaptive stress (“tics of the first of September”). Among other stressful situations, separation from one of the parents as a result of family breakdown, episodes of sudden fright are common. In some children, tics occur after a prolonged mental overload, which can be considered as a chronic stressor. The hallmark of tics is their irresistible nature. Any attempt to suppress the appearance of a tic by willpower inevitably leads to an increase in tension and anxiety, and the forcible accomplishment of the desired motor reaction brings instant relief. Tics can be motor (motor) and vocal (vocal). Motor tics resemble purposeful movement; the most frequent of them are blinking, frowning of eyebrows. Less common are head turns or tilting the head back (remember the staff captain Ovechkin performed by Armen Dzhigarkhanyan from the movie "New Adventures of the Elusive" or Lelik from "The Diamond Hand" performed by Andrei Mironov). Vocal tics are manifested by shouting out nonsense sounds or words. In severe cases, vocal tics can manifest as coprolalia (saying aggressive, offensive, or socially inappropriate words or phrases). The combination of motor and vocal tics is called Tourette's syndrome. It is known that similar manifestations were observed in Mozart. The course of tics is undulating with periods of improvement and exacerbation. In children, for example, a period of improvement can be observed during the holidays. Approximately half of children with tics have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). And tics are observed in about one in three children with ADHD. These diseases have many common links of pathogenesis. Tics are more common in cases of predominance of hyperactivity and impulsivity (rather than inattention). Usually, the manifestations of ADHD are noted earlier, and tics join later. Frequent companions of tics are dysgraphia and dyslexia. In addition, children with tics often have various obsessions - obsessive movements, thoughts, desires. Children with tics are treated by pediatric neurologists and psychotherapists. It is best to contact a specialized center where there are neurologists, psychotherapists, psychologists. Before starting treatment, it is better to do an electroencephalogram. Children with tics should follow a daily routine. If possible, unusual negative and positive stimuli should be excluded. There are peculiarities of psychological correction in children with tics. The main goal in such cases is not so much to reduce hyperkinesis, but to improve social adaptation. Since children with tics are characterized by low self-esteem and increased anxiety, it is necessary to encourage patients, inspire them to believe in themselves. It is also necessary to explain to the parents of such children that tics are not arbitrary. This is very important psychologically, as the relatives of the patient often notice that sometimes he can hold back the tick. As a result, some begin to consider tics a disease, others - promiscuity. It makes no sense to restrain tics, and it is also impossible to focus the child's attention on hyperkinesias. Psychotherapy plays a special role in the treatment of tics. For the treatment of tics, the following psychotherapeutic methods are used: behavioral (behavioral) methods of therapy, hypnotherapy, autogenic training, symbolodrama. Using the biofeedback method will allow the child to learn to relax and reduce not only tics, but also psycho-emotional stress. Tranquilizers and neuroleptics are used in the treatment of tics, which have a calming effect. Since tics are often combined with inattention and school problems, complex treatment uses various nootropic drugs that positively affect the higher integrative functions of the brain. A neurologist will recommend a specific drug for treating your child. And one more thing: to improve the child's condition, it is important that the parents themselves be as calm and cheerful as possible.

|

Tics and comorbid disorders of childhood | Zykov V.

P., Kashirina E.A., Naugolnykh Yu.V.

P., Kashirina E.A., Naugolnykh Yu.V. Urgency of the problem

Tics are the dominant form of childhood hyperkinesis, diagnosed in 5–24% of children, more often in boys, chronic forms of tics are observed in 1% of the child population [1, 2]. In Russia, using the Moscow region as an example, tics are diagnosed in 6% of children, and Tourette's syndrome (TS) in 0.1% [1]. In Europe, TS is detected in 1% of school-age children [3, 4]. In the United States, based on data from the National Review of Children's Health, the diagnosis of TS was made in 3 out of 1000 children aged 6–17 years [5]. The peak incidence occurs in preschool and school age with maximum manifestations at 7–12 years of age. In the total number of patients, boys predominate: among patients with tics, they are 3 times more, among patients with TS, 5–6 times more [1, 6–8].

In 80% of cases, tics and TS are accompanied by comorbid symptoms such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety disorders, and memory loss [1, 2, 8–12].

With tics, ADHD is diagnosed in 20–50% of patients; with TS, in 80% [13, 14]. Molecular genetic studies have found associations of TS with ADHD, alcoholism, gambling, drug addiction, and variations in dopamine receptor genes (DRD4 7 allele and DRD5 148bp allele) and dopamine transporter genes (DAT1 10 allele) [15]. Genes that regulate the metabolism of the neurotransmitters dopamine and noradrenaline determine the predisposition to the development of ADHD [15].

Children with ADHD often have low self-esteem, they develop emotional and social difficulties in communicating with peers, school performance is often reduced, and there is a tendency to delinquency and antisocial behavior [16]. The severity of ADHD depends on the severity of tic symptoms and the duration of the disease [1].

Other types of comorbid disorders in patients with tics include a high level of anxiety, detected using the Spielberg test [17]. Children with tics had a significantly higher incidence of anxiety disorders than children without tics (21% versus 15%), simple phobias (29% vs. 19%), social phobias (28% vs. 18%) [15]. A relationship was found between the severity of tics according to YGTSS and the level of depression and anxiety [16].

19%), social phobias (28% vs. 18%) [15]. A relationship was found between the severity of tics according to YGTSS and the level of depression and anxiety [16].

In addition to ADHD, up to 79% of symptoms comorbid with ST were identified: mood disorders and anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorders, autism spectrum disorders, anger control problems, oppositional defiant, impulsive, self-aggressive and aggressive behavior [7, 15, 18]. Concomitant anxiety and depression have a significant impact on the quality of life in TS [17].

Comorbid symptoms, to a greater extent than tics, can disrupt the life of patients, and without timely correction lead to significant social maladaptation [1, 19–21].

Purpose of the study: to study comorbid disorders in patients with childhood tic hyperkinesis and evaluate the possibilities of drug correction.

Material and methods

We examined 165 children and adolescents aged 7 to 16 years, including the control group - 35 people without signs of damage to the nervous system, comparable in sex and age with the examined patients. The main cohort consisted of 130 patients aged 7 to 16 years, of which 94 (72.3%) boys and 36 (27.7%) girls who were under outpatient observation at Children's City Clinical Hospital No. 110 in Moscow from 2014 to 2016

The main cohort consisted of 130 patients aged 7 to 16 years, of which 94 (72.3%) boys and 36 (27.7%) girls who were under outpatient observation at Children's City Clinical Hospital No. 110 in Moscow from 2014 to 2016

The patients were divided into 3 groups according to the severity and semiotics of the disease: group 1 - with isolated motor tics (n=21), group 2 - with motor-vocal tics (n=87), group 3 - with TS (n=22) . The examined patients were diagnosed with an age-dependent stage - the stage of symptom expression, tic status was detected in 59 (45.5%) patients.

Antiticosis therapy included pantocalcin 50 mg/kg, tiapride 100-300 mg/day, topiramate 1-2 mg/kg. Hopantenic acid was used in children aged 7–8 years at the onset of the disease at a dose of 75–150 mg.

Tic hyperkinesis was assessed according to DSM-IV, (1994), V.P. Zykov [1, 22]. To clarify the diagnosis of TS, we used the diagnostic criteria developed in DSM-IV, as well as the criteria proposed by a specially created group for the study of tic classification (Tourette Syndrome Classification Study Group - TSSG) [22, 23]. Clinical registration of tic hyperkinesias was carried out using testing on the Yale scale with the determination of the cumulative and total severity of tics (YGTSS) and using the method of counting tics in 20 minutes [1, 24].

Clinical registration of tic hyperkinesias was carried out using testing on the Yale scale with the determination of the cumulative and total severity of tics (YGTSS) and using the method of counting tics in 20 minutes [1, 24].

Diagnostic criteria for ADHD are defined in the DSM-IV, DSM-V, as well as in the ICD-10 criteria for hyperkinetic disorders [20, 22, 25]. To clarify the severity of ADHD, a version of the Conners scale for parents was used, filled in by parents, a doctor, adapted for outpatient monitoring [26]. The assessment of personal and situational anxiety was determined using the Spielberg-Khanin test [27].

The neuropsychological study included the study of short-term auditory-speech memory according to the method proposed by L.I. Wasserman et al. [28].

Results and discussion

The age of the examined children was on average 9 years, patients with TS - 12 years (Table 1). The age of debut of tics was observed from 4 to 7 years. The duration of the disease at the time of examination in groups 1 and 2 was 4 years, in group 3 - 7–8 years. Hereditary predisposition to the development of tic hyperkinesis was determined in 91 (70%) patients and was 3 times more common in boys than in girls. Sporadic tic hyperkinesis was observed in 39 (30%) patients.

The duration of the disease at the time of examination in groups 1 and 2 was 4 years, in group 3 - 7–8 years. Hereditary predisposition to the development of tic hyperkinesis was determined in 91 (70%) patients and was 3 times more common in boys than in girls. Sporadic tic hyperkinesis was observed in 39 (30%) patients.

Tics were diagnosed in all examined patients. The number of ticks was recorded using the technique of counting ticks in 20 min (Fig. 1). The maximum number of motor tics in 20 min - 118.59±94.73 episodes - was detected in the ST group, in the group of motor tics - 52.0±55.86 (p<0.01), in the group of motor-vocal tics - 69.45±83.44 (p<0.05). There were no significant differences in the number of vocal tics in 20 minutes between the groups of motor-vocal tics (37.30±37.5) and ST (37.09±5.34).

The Yale scale was used to determine the severity of clinical manifestations of tics in all patients with hyperkinesis (Fig. 2). Indicators of cumulative (29. 025±8.74 points) and total (48.25±16.17 points) severity according to the Yale scale prevailed in the group of motor-vocal tics in comparison with the group of motor tics (p<0.01) – 13.43 ±7.23 points and 29.81±15.9 points, respectively. The maximum number of points of cumulative (37.09±5.34 points) and total (69.27±13.65 points) severity according to the Yale scale was registered in the ST group (p<0.01 in comparison with the motor tic group and the motor tic group). - vocal tics).

025±8.74 points) and total (48.25±16.17 points) severity according to the Yale scale prevailed in the group of motor-vocal tics in comparison with the group of motor tics (p<0.01) – 13.43 ±7.23 points and 29.81±15.9 points, respectively. The maximum number of points of cumulative (37.09±5.34 points) and total (69.27±13.65 points) severity according to the Yale scale was registered in the ST group (p<0.01 in comparison with the motor tic group and the motor tic group). - vocal tics).

Thus, the maximum number of motor and vocal tics according to the method of counting tics in 20 minutes and the highest YGTSS values were determined in the CT group. The 20-minute tick count has a direct correlation with the YGTSS severity score.

ADHD was detected in 42.8% of patients with motor tics, in 50.6% with motor-vocal tics, and in 86.4% with TS.

ADHD significantly predominated in the ST group compared to the motor tic group (p<0.01). There were no significant differences between groups 2 and 3.

According to the results of the study of cognitive functions in patients with tics (Fig. 3), there was a significant decrease in the volume of short-term auditory memory in comparison with the control group (p < 0.01), and patients with TS are characterized by a significant decrease in the volume of auditory-verbal memory in comparison with patients with motor tics (p<0.01).

Patients with tics complained of fear of the dark, an empty apartment, fear of losing loved ones and separation from them, possible failure in school, poor grades, in connection with which an anxiety test (Spielberg-Khanin test) was used during a clinical examination.

The same high level of situational anxiety according to the Spielberg-Khanin test (Fig. 4) was detected in all groups of patients without significant differences between the groups.

The answers of children with tics to the questions of the Spielberg-Khanin test, which determine the level of personal and situational anxiety, were analyzed. Personal anxiety as a character trait in children with tics was shown by a number of statements emphasizing self-doubt, weakness and increased exhaustion of the emotional-volitional sphere, increased susceptibility and resentment, bad mood and mood swings, and a tendency to prolonged experiences. Situational anxiety was determined by states of excitement, fear of uncertainty before the prevailing circumstances.

Personal anxiety as a character trait in children with tics was shown by a number of statements emphasizing self-doubt, weakness and increased exhaustion of the emotional-volitional sphere, increased susceptibility and resentment, bad mood and mood swings, and a tendency to prolonged experiences. Situational anxiety was determined by states of excitement, fear of uncertainty before the prevailing circumstances.

A direct linear correlation was determined between the severity of personal anxiety and the severity of ADHD in patients with TS (p<0.05).

The combination of anxiety disorders and ADHD was found in 42.8% of children with motor tics, 40.2% with motor-vocal tics, and 95.2% with TS (p<0.002, p<0.001 with groups of tics) (Table 1). 2).

Antiticosis therapy included pantocalcin 50 mg/kg, tiapride 100-300 mg/day, topiramate 1-2 mg/kg. Against the background of a decrease in hyperkinesis, there was a regression of manifestations of ADHD and anxiety disorders in patients from the group of motor and motor-vocal tics. Patients with TS had persistently high rates of personal anxiety and ADHD before and after treatment. An increase in the volume of short-term auditory-speech memory was recorded in all groups with tics and TS (p<0.05).

Patients with TS had persistently high rates of personal anxiety and ADHD before and after treatment. An increase in the volume of short-term auditory-speech memory was recorded in all groups with tics and TS (p<0.05).

The use of hopantenic acid in children aged 7–8 years at the onset of the disease at a dose of 75–150 mg led to a regression of motor and vocal tics (p<0.05), taking into account the indicators of counting tics in 20 minutes and the Yale scale, improved auditory-speech memory ( p<0.05). While taking hopantenic acid, a significant direct linear relationship was revealed between the severity of tics and the severity of ADHD in the group of boys.

Topiramate at a dose of 1–2 mg/kg reduced the number of motor tics at the stage of symptom expression (p<0.05), reduced the level of personal anxiety in comparison with the use of other drugs (p<0.05). Tiapride at a dose of 100-300 mg/day at the stage of symptom expression, along with the regression of motor and vocal tics (p<0. 05), had an effect on reducing attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (p<0.05).

05), had an effect on reducing attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (p<0.05).

Homeostres (Sedatif PC) has been successfully used to treat anxiety disorders in 33 countries for over 60 years. Homeostres ® (LSR-006558/09) has been registered in the Russian Federation since 2008 and has been successfully used to correct anxiety disorders in children older than 3 years. According to our experience and scientific publications, it is possible to use Homeostres ® for a short-term course of anxiety correction, the effect of which is comparable to phenibut [29] and fabomotizole dihydrochloride [30]. Homeostres ® is indicated for anxiety, restlessness and sleep disorders. A distinctive feature of Homeostres is a relatively quick effect - a significant decrease in the severity of anxiety and normalization of sleep by the 3rd day. Homeostres® reduces the level of anxiety, regardless of the condition: chronic or sudden. At the same time, there is a significant improvement in the quality and duration of sleep (2 times less nighttime awakenings). The effect of treatment remains unchanged for 4 weeks after a 2-week course of therapy [31, 32], which makes it possible to reduce the drug load on the patient. Homeostres ® is well tolerated, does not cause drowsiness, daytime retardation and does not affect the ability to concentrate. Homeostres ® does not interact with other drugs and is optimally combined with other drugs. To date, against the background of Homeostres therapy, there have been no cases of addiction, there is no withdrawal syndrome.

The effect of treatment remains unchanged for 4 weeks after a 2-week course of therapy [31, 32], which makes it possible to reduce the drug load on the patient. Homeostres ® is well tolerated, does not cause drowsiness, daytime retardation and does not affect the ability to concentrate. Homeostres ® does not interact with other drugs and is optimally combined with other drugs. To date, against the background of Homeostres therapy, there have been no cases of addiction, there is no withdrawal syndrome.

Pins:

1. In patients with tic disorders, comorbid disorders are represented by attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (80%), a decrease in the volume of short-term auditory-speech memory (90%), situational and personal anxiety (85%), which may have a pathogenetic mutual influence.

2. The severity of ADHD depended on the severity of tic hyperkinesis: motor tics (mild) were combined with mild ADHD; motor-vocal tics (moderate severity) - with mild and moderate ADHD, ST (severe) - with moderate and severe ADHD.

Tics are greatly amplified under the influence of emotional stimuli - anxiety, fear, embarrassment.

Tics are greatly amplified under the influence of emotional stimuli - anxiety, fear, embarrassment.  Some patients note seasonal fluctuations in the intensity of symptoms.

Some patients note seasonal fluctuations in the intensity of symptoms.  The tics often get worse while watching television, especially when the electric lights are off. The fact is that bright flickering light can provoke changes in the bioelectrical activity of the brain. Therefore, watching TV programs for children with tics should be as limited as possible for 1-1.5 months. The same restrictions apply to computer games.

The tics often get worse while watching television, especially when the electric lights are off. The fact is that bright flickering light can provoke changes in the bioelectrical activity of the brain. Therefore, watching TV programs for children with tics should be as limited as possible for 1-1.5 months. The same restrictions apply to computer games.