Treating borderline patients

Borderline personality disorder - Diagnosis and treatment

Diagnosis

Personality disorders, including borderline personality disorder, are diagnosed based on a:

- Detailed interview with your doctor or mental health provider

- Psychological evaluation that may include completing questionnaires

- Medical history and exam

- Discussion of your signs and symptoms

A diagnosis of borderline personality disorder is usually made in adults, not in children or teenagers. That's because what appear to be signs and symptoms of borderline personality disorder may go away as children get older and become more mature.

Treatment

Borderline personality disorder is mainly treated using psychotherapy, but medication may be added. Your doctor also may recommend hospitalization if your safety is at risk.

Treatment can help you learn skills to manage and cope with your condition. It's also necessary to get treated for any other mental health disorders that often occur along with borderline personality disorder, such as depression or substance misuse. With treatment, you can feel better about yourself and live a more stable, rewarding life.

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy — also called talk therapy — is a fundamental treatment approach for borderline personality disorder. Your therapist may adapt the type of therapy to best meet your needs. The goals of psychotherapy are to help you:

- Focus on your current ability to function

- Learn to manage emotions that feel uncomfortable

- Reduce your impulsiveness by helping you observe feelings rather than acting on them

- Work on improving relationships by being aware of your feelings and those of others

- Learn about borderline personality disorder

Types of psychotherapy that have been found to be effective include:

- Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT). DBT includes group and individual therapy designed specifically to treat borderline personality disorder. DBT uses a skills-based approach to teach you how to manage your emotions, tolerate distress and improve relationships.

- Schema-focused therapy. Schema-focused therapy can be done individually or in a group. It can help you identify unmet needs that have led to negative life patterns, which at some time may have been helpful for survival, but as an adult are hurtful in many areas of your life. Therapy focuses on helping you get your needs met in a healthy manner to promote positive life patterns.

- Mentalization-based therapy (MBT). MBT is a type of talk therapy that helps you identify your own thoughts and feelings at any given moment and create an alternate perspective on the situation. MBT emphasizes thinking before reacting.

- Systems training for emotional predictability and problem-solving (STEPPS). STEPPS is a 20-week treatment that involves working in groups that incorporate your family members, caregivers, friends or significant others into treatment. STEPPS is used in addition to other types of psychotherapy.

- Transference-focused psychotherapy (TFP).

Also called psychodynamic psychotherapy, TFP aims to help you understand your emotions and interpersonal difficulties through the developing relationship between you and your therapist. You then apply these insights to ongoing situations.

Also called psychodynamic psychotherapy, TFP aims to help you understand your emotions and interpersonal difficulties through the developing relationship between you and your therapist. You then apply these insights to ongoing situations. - Good psychiatric management. This treatment approach relies on case management, anchoring treatment in an expectation of work or school participation. It focuses on making sense of emotionally difficult moments by considering the interpersonal context for feelings. It may integrate medications, groups, family education and individual therapy.

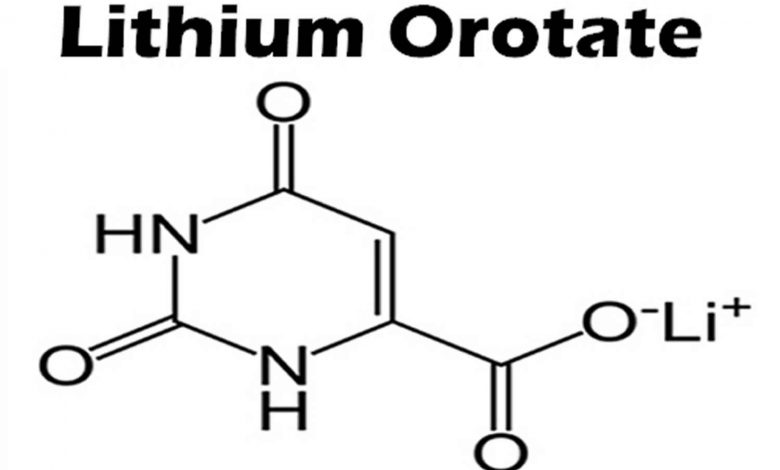

Medications

Although no drugs have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration specifically for the treatment of borderline personality disorder, certain medications may help with symptoms or co-occurring problems such as depression, impulsiveness, aggression or anxiety. Medications may include antidepressants, antipsychotics or mood-stabilizing drugs.

Talk to your doctor about the benefits and side effects of medications.

Hospitalization

At times, you may need more-intense treatment in a psychiatric hospital or clinic. Hospitalization may also keep you safe from self-injury or address suicidal thoughts or behaviors.

Recovery takes time

Learning to manage your emotions, thoughts and behaviors takes time. Most people improve considerably, but you may always struggle with some symptoms of borderline personality disorder. You may experience times when your symptoms are better or worse. But treatment can improve your ability to function and help you feel better about yourself.

You have the best chance for success when you consult a mental health provider who has experience treating borderline personality disorder.

More Information

- Psychotherapy

Request an Appointment at Mayo Clinic

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free, and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips and current health topics, like COVID-19, plus expertise on managing health.

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Coping and support

Symptoms associated with borderline personality disorder can be stressful and challenging for you and those around you. You may be aware that your emotions, thoughts and behaviors are self-destructive or damaging, yet you feel unable to manage them.

You may be aware that your emotions, thoughts and behaviors are self-destructive or damaging, yet you feel unable to manage them.

In addition to getting professional treatment, you can help manage and cope with your condition if you:

- Learn about the disorder so that you understand its causes and treatments

- Learn to recognize what may trigger angry outbursts or impulsive behavior

- Seek professional help and stick to your treatment plan — attend all therapy sessions and take medications as directed

- Work with your mental health provider to develop a plan for what to do the next time a crisis occurs

- Get treatment for related problems, such as substance misuse

- Consider involving people close to you in your treatment to help them understand and support you

- Manage intense emotions by practicing coping skills, such as the use of breathing techniques and mindfulness meditation

- Set limits and boundaries for yourself and others by learning how to appropriately express emotions in a manner that doesn't push others away or trigger abandonment or instability

- Don't make assumptions about what people are feeling or thinking about you

- Reach out to others with the disorder to share insights and experiences

- Build a support system of people who can understand and respect you

- Keep up a healthy lifestyle, such as eating a healthy diet, being physically active and engaging in social activities

- Don't blame yourself for the disorder, but recognize your responsibility to get it treated

Preparing for your appointment

You may start by seeing your primary care doctor. After an initial appointment, your doctor may refer you to a mental health provider, such as a psychologist or psychiatrist. Here's some information to help you prepare for your appointment.

After an initial appointment, your doctor may refer you to a mental health provider, such as a psychologist or psychiatrist. Here's some information to help you prepare for your appointment.

What you can do

Before your appointment, make a list of:

- Any symptoms you or people close to you have noticed, and for how long

- Key personal information, including traumatic events in your past and any current major stressors

- Your medical information, including other physical or mental health conditions

- All medications you take, including prescription and over-the-counter medications, vitamins and other supplements, and the doses

- Questions you want to ask your doctor so that you can make the most of your appointment

Take a family member or friend along, if possible. Someone who has known you for a long time may be able to share important information with the doctor or mental health provider, with your permission.

Basic questions to ask your doctor or a mental health provider include:

- What's likely causing my symptoms or condition?

- Are there any other possible causes?

- What treatments are most likely to be effective for me?

- How much can I expect my symptoms to improve with treatment?

- How often will I need therapy sessions and for how long?

- Are there medications that can help?

- What are the possible side effects of the medication you may prescribe?

- Do I need to take any precautions or follow any restrictions?

- I have these other health conditions. How can I best manage them together?

- How can my family or close friends help me in my treatment?

- Do you have any printed material that I can take? What websites do you recommend?

Don't hesitate to ask questions during your appointment.

What to expect from your doctor

A doctor or mental health provider is likely to ask you a number of questions. Be ready to answer them to save time for topics you want to focus on. Possible questions include:

Be ready to answer them to save time for topics you want to focus on. Possible questions include:

- What are your symptoms? When did you first notice them?

- How are these symptoms affecting your life, including your personal relationships and work?

- How often during the course of a normal day do you experience a mood swing?

- How often have you felt betrayed, victimized or abandoned? Why do you think that happened?

- How well do you manage anger?

- How well do you manage being alone?

- How would you describe your sense of self-worth?

- Have you ever felt you were bad, or even evil?

- Have you had any problems with self-destructive or risky behavior?

- Have you ever thought of or tried to harm yourself or attempted suicide?

- Do you use alcohol or recreational drugs or misuse prescription drugs? If so, how often?

- How would you describe your childhood, including your relationship with your parents or caregivers?

- Were you physically or sexually abused or were you neglected as a child?

- Have any of your close relatives or caregivers been diagnosed with a mental health problem, such as a personality disorder?

- Have you been treated for any other mental health problems? If yes, what diagnoses were made, and what treatments were most effective?

- Are you currently being treated for any other medical conditions?

By Mayo Clinic Staff

Related

Associated Procedures

Products & Services

TREATING BPD | National Education Alliance for Borderline Personality Disorder

Treatments for Borderline Personality Disorder

Current research shows that treatment can decrease the symptoms and suffering of people with BPD.

Talk therapy is usually the first choice of treatment (unlike some other illnesses where medication is often first.) Generally, treatment involves one to two sessions a week with a mental health counselor. For therapy to be effective, people must feel comfortable with and trust their therapist.

Some BPD symptoms are easier to treat than others. Fears that others might leave, intense, unstable relationships or feelings of emptiness are often hardest to change. Research shows that treatment is more effective in decreasing anger, suicide attempts and self- harm, as well as helping to improve over-all functioning and social adjustment

People whose symptoms improve may still have issues related to co-occurring disorders, such as depression, substance abuse, eating disorders, or post-traumatic stress disorder. However, research suggests that full-blown BPD symptoms rarely coming back after remission.

There are several treatments that are most often used to manage BPD

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) focuses on the concept of mindfulness, or paying attention to the present emotion. DBT teaches skills to control intense emotions, reduce self-destructive behavior, manage distress, and improve relationships. It seeks a balance between accepting and changing behaviors. This proactive, problem-solving approach was designed specifically to treat BPD. Treatment includes individual therapy sessions, skills training in a group setting, and phone coaching as needed. DBT is the most studied treatment for BPD and the one shown to be most effective.

DBT teaches skills to control intense emotions, reduce self-destructive behavior, manage distress, and improve relationships. It seeks a balance between accepting and changing behaviors. This proactive, problem-solving approach was designed specifically to treat BPD. Treatment includes individual therapy sessions, skills training in a group setting, and phone coaching as needed. DBT is the most studied treatment for BPD and the one shown to be most effective.

Mentalization-based therapy (MBT) is a talk therapy that helps people identify and understand what others might be thinking and feeling.

Transference-focused therapy (TFP) is designed to help patients understand their emotions and interpersonal problems through the relationship between the patient and therapist. Patients then apply the insights they learn to other situations.

Good Psychiatric Management: GPM provides mental health professionals an easy-to-adopt “tool box” for patients with severe personality disorders.

Medications cannot cure BPD but can help treat other conditions that often accompany BPD such as depression, impulsivity, and anxiety. Often patients are treated with several medications, but there is little evidence that this approach is necessary or effective. People with BPD are encouraged to talk with their prescribing doctor about what to expect from each medication and its side effects. 1

Self-Care activities include: regular exercise, good sleep habits, a nutritious diet, taking medications as prescribed, and healthy stress management. Good self-care can help to reduce common symptoms of BPD such as mood changes, impulsive behavior, and irritability.

1. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR. omega-3 Fatty acid treatment of women with borderline personality disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003 Jan;160(1):167–9.

Borderline Personality Disorder, Symptoms, Causes, Diagnosis, Treatment

Borderline Personality Disorder (abbreviated as BPD ) is increasingly common among children today. The pathogenesis of this type of psychopathy is usually accompanied by a complex of unfavorable factors.

The pathogenesis of this type of psychopathy is usually accompanied by a complex of unfavorable factors.

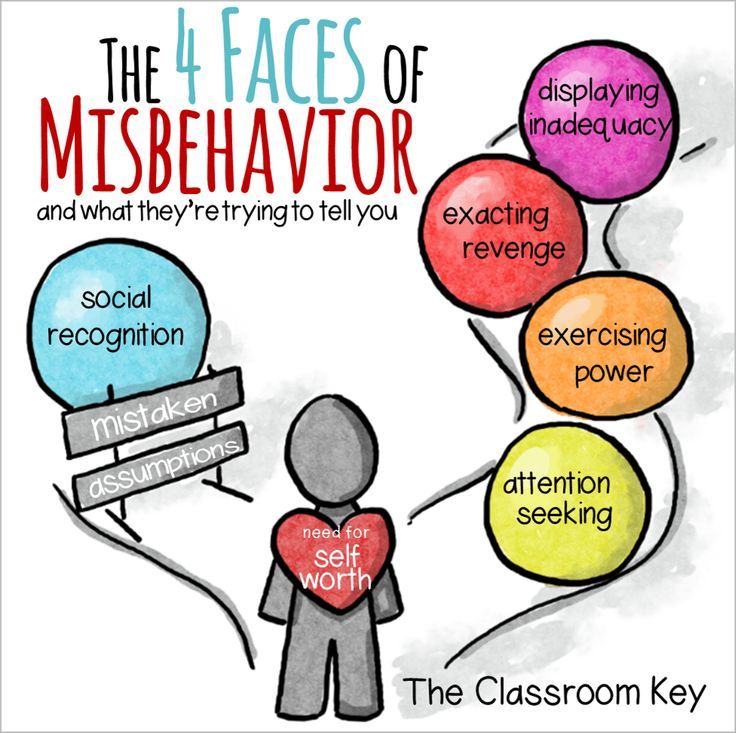

It is quite difficult to recognize this type of disease in everyday life. Often, it is confused with narcissism or simply the bad character of the individual, since the behavior of the "border guards" can be characterized by an extreme degree of unpredictability and hysteria, as well as a tendency to manipulation. For example, they confess their love to a partner, and after a couple of hours they leave “forever”, they can sincerely sympathize with someone, and then hit. It is also very common for patients of this type to constantly violate the boundaries of other people, shifting their problems onto them, and avoiding responsibility. Consider the symptoms of borderline in more detail.

Symptoms of borderline personality disorder (BPD)

The main symptomatic difference of this type of disorder is prolonged abnormal behavior of the patient .

While in many other psychopathy periods of instability alternate with remission, in the case of BPD the patient behaves destructively over a long period of time. In the field of psychological anomalies are such manifestations as:

In the field of psychological anomalies are such manifestations as:

- aggressive behavior leading to problems in relationships,

- unstable emotional background and inadequate self-image,

- high anxiety,

- total fear of loneliness and permanent feeling of boredom,

- dichotomous thinking and changeable mood, dividing the world only into "black and white" (today I love, but tomorrow I hate).

Also among the main symptoms can be noted: sociopathy and fear of society associated with low self-esteem and, as a result, separation anxiety (it is experienced by a person when separated from home or loved ones). Patients often exhibit reckless irresponsible "risky" behavior, the extreme form of which may be self-harm or suicide attempt.

Types of spontaneous actions that accompany mental borderline personality disorders

Due to difficulties in self-identification, lack of one's own opinion and a tendency to polarity, spontaneous destructive actions are characteristic of BPD sufferers.

Panic fear of loneliness and lack of an inner core pushes them into contact with sociopathic personalities who are characterized by destructive behavior: gambling, theft, vandalism, promiscuous relationships, drug addiction. This also includes self-harm, which was mentioned above.

One of the reasons for this uncontrolled behavior is the problem with holding the inner impulse. The level of impulsivity is so high that a person is not able to control it.

Besherednichenko Andrey Nikolaevich

Chief physician of the Korsakov Medical Center network, psychiatrist-narcologist

- Experience for more than 11 years

Consultation

Records for reception

Emotional unstable personality disorder in the ICD of the 10th review of the 10th review of the 10th review of the 10th review personality disorder is defined as "Emotionally unstable personality disorder (F60.3)". In the clinical community on the territory of the Russian Federation, this name is used quite often and is used due to the fact that the main symptom, as described above, manifests itself in the form of an emotionally unstable mental state of a person.

BPD pathogenesis

In the pathogenesis of the disease lies an incorrectly or incompletely formed intrapersonal self-awareness, in other words, “self-identification”. Border guards hardly realize how they relate to the main areas of life. They have problems with the concept of their opinions, interests, hobbies, and their character as well. Hence the more common definition of the disorder - "borderline". In this aspect, it means maneuvering on the verge between psychopathy and a stable state. The word "borderline" in a particular case means a precarious state between the norm and deviation, as if a person lives on the verge between "mental illness" (psychosis) and "mental health". That is why, the slang name for patients of this type is “borderliners” (from the English expression “border line”, which literally translates as “border”).

In classical psychiatry, borderline personality disorder is also classified as a type of ego syntonic disorder. Ego syntonicity implies that the patient does not assess his condition as painful, is not critical of him and calmly accepts deviations in behavior, not believing that they harm him in any way. Moreover, the patient, as it were, “defends” his symptom, preventing his own cure due to the difficulty in identifying his own “I”.

Moreover, the patient, as it were, “defends” his symptom, preventing his own cure due to the difficulty in identifying his own “I”.

Causes of BPD

The underlying causes of BPD are currently not clearly defined, however, like most other disorders, BPD is caused by a group of factors.

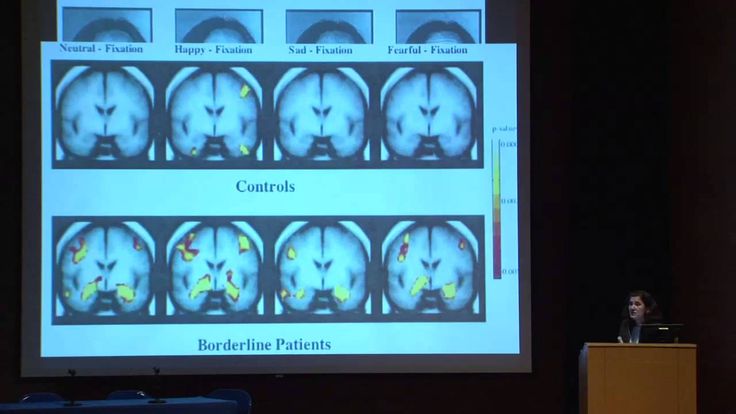

Hereditary (genetic determinism), physiological (disturbances in the brain) and social factors (low stress resistance and psychological traumatic factor).

Unfavorable social environment

According to statistics, groups of people exposed to an unfavorable social environment, for example, in the family, are more susceptible to the disease. These include:

- difficult childhood,

- abuse,

- tyranny,

- physical or emotional domestic violence,

- early loss of parents.

It is worth noting that "borderliness" occurs 3 times more often among women than among men.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) , as a variation of an unfavorable social factor, can act not only as a cause, but also as a concomitant individual disease that is in a pathogenetic relationship with the diagnosis in question.

Childhood chronic emotional trauma can contribute to the development of BPD, but in rare cases it is the only cause. Personal qualities that are responsible for the ability to cope with a stressful situation in this aspect also play a big role. Here it is worth noting that, according to statistics, an injury received in childhood (especially before the age of 10) can lead to a subsequent disorder much more likely than an injury received at an older age. Also, scientists note that situations not associated with direct violence, such as natural disasters or catastrophes, are less likely to lead to the development of post-traumatic syndrome.

Physiology

Another group of factors considers a possible cause of the development of the disease - a disruption in the functioning of neural brain connections, namely the destruction of the functioning of the frontal limbic neurons

Heredity

diagnosis. It is quite difficult to achieve clear indicators in this vein, however, according to European studies, BPD is located in 3rd place out of 10 in terms of the genetic determinant among personality disorders. It is logical to note that deviations in the work of certain parts of the brain can be inherited and lead to a number of psychological problems, the development of which is aggravated by the social factor. Most studies show that borderlines are most often passed on from the mother.

It is logical to note that deviations in the work of certain parts of the brain can be inherited and lead to a number of psychological problems, the development of which is aggravated by the social factor. Most studies show that borderlines are most often passed on from the mother.

Borderline state of the psyche in psychiatry and the severity of personality disorders

In clinical psychiatry, three levels of mental disorder are traditionally distinguished:

- Neurotic . These include neuroses of a different nature, implying reversible temporary conditions that can be treated.

- Psychopathic level . In its plane lie personality disorders, which include anomalies in the nature of various pathogenesis or painful changes in its features, with which nothing can be done, since they relate to the personality structure of the individual.

- Finally, the deepest lesion of the psyche manifests itself at the psychotic level .

This includes such manifestations as delirium, hallucinations, twilight consciousness.

This includes such manifestations as delirium, hallucinations, twilight consciousness.

Modern psychoanalysis distinguishes 4 levels of deviations. Between the state of psychosis and neurosis, it is conditionally located just “ borderline level”, also called borderline state . A borderline state can mean both the disorder itself and the designation of the level of mental damage.

How to reliably identify borderline personality disorder (BPD)

Borderline personality disorder is extremely difficult to diagnose and differentiate, as it has a high level of comorbidity, in other words, it is combined with a large number of concomitant disorders. For example, panic anxiety, eating disorders, bipolar affective disorder, attention deficit disorder, sociopathy, and so on. In connection with the above, the patient has to undergo a long diagnostic process and special tests.

Borderline personality disorder BPD test

One of the fairly popular tools for detecting the presence of psychopathy are tests, which are, in fact, a personality questionnaire. Used in modern clinical psychology, a test for screening for the bright signs of BPD was developed in 2012 by a group of scientists. In their work, the authors relied on the basic criteria for differentiating borderline disorder.

Used in modern clinical psychology, a test for screening for the bright signs of BPD was developed in 2012 by a group of scientists. In their work, the authors relied on the basic criteria for differentiating borderline disorder.

The questionnaire edited by them is a fairly effective tool for diagnostic verification and confirmation of symptoms. It is used both in psychiatric and general clinical, and in other practices that are not directly related to medicine.

The test itself consists of 20 questions and asks the subject to answer only yes or no. For each answer, the system counts a certain number of points. The probability of diagnosing BPD appears if the respondent scored more than 25 points.

Treatment of borderline personality disorder (BPD)

Cherednichenko Andrey Nikolaevich

Head physician of the network of medical centers "Korsakov", psychiatrist-narcologist

- Experience over 11 years

Consultation

Appointment

Like most other mental disorders, borderline disorder is not treated at home and requires complex occupational therapy, including both medication (taking antidepressants and antipsychotics) and psychotherapy. And only a psychiatrist, often in tandem with a clinical psychologist, can competently develop an effective course of treatment.

And only a psychiatrist, often in tandem with a clinical psychologist, can competently develop an effective course of treatment.

The drug course is developed in accordance with the individual characteristics of the patient's body and includes the following drug groups:

- Selective inhibitors of are aimed at preventing depressive episodes and reducing anxiety/panic/borderlines.

- Mood stabilizers .

One of the most popular remedies is Lamotrigine. It is also used to neutralize depression, mood lability and impulsivity.

- Atypical antipsychotics .

Now the 2nd generation of drugs of this cluster has already been developed, which have proven themselves well in neutralizing the symptoms of the cognitive sphere, such as: aggression, distortion of perception of reality, paranoia, dichotomy of thinking and disorganization.

As for the group of benzodiazepines and stimulants, they are used in modern therapy extremely rarely due to the high risk of dependence and, accordingly, overdose.

Thus, the main task of drug therapy in borderline personality disorder is to reduce the severity of symptoms and alleviate the general condition of the patient.

It is worth noting that BPD is the most difficult to treat due to the patient's ego syntony, which we discussed above. It is the patient with BPD who is the most difficult to respond to any therapy due to the rigidity of the psyche and the clear conviction that everything is generally normal with them.

However, when it comes to Selective Inhibitors, Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT), one of the varieties of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), is considered the most effective method in the modern clinical community. As part of the treatment, the patient is taught to look at the problem from different points of view and evaluate the causal relationship in different ways. Due to satisfaction with their symptoms and rigidity, "border guards" are difficult to treat, so the psychotherapeutic process can be lengthy.

Most often, relatives suffer the most from relationships with patients with BPD, so another parameter that the specialist works on is the patient's socialization and adaptation, aimed at developing basic life skills and developing an adequate behavior for the situation. In psychiatry, this type of technique is called STEPPS (System Training Emotional Predictability & Problem Solution) and in translation means Systematic Training in Emotional Predictability and Problem Solving.

One of the well-established methods are meditation techniques aimed at teaching a person to control their emotions and the ability to relax.

Another effective method when working with a psychotraumatic factor is the gelstat technique, during which the patient returns to a stressful situation and looks at it from the other side, rebuilding the scenario or acting it out again. The task of a specialist in this aspect is to remove the negative emotional charge from the memory.

Therapy with borderline patients | Journal of Practical Psychology and Psychoanalysis

Year of publication and journal number:

2014, No. 3

3

| Comment: A chapter from the second edition of Nancy McWilliams's book Psychoanalytic Diagnostics. Understanding the Structure of Personality in the Clinical Process”, which is being prepared for publication in early 2015 by the Independent Firm Klass. |

Annotation

The article is devoted to the general principles of psychoanalytic psychotherapy of borderline personality disorder.

Key words: borderline personality disorder, psychoanalytic psychotherapy.

Different views on etiology and different traditions of therapy naturally lead to different approaches to treatment, and there are so many controversies in the literature about the treatment of borderline clients that it is impossible to describe them in full detail in a few paragraphs. Yet, it is noteworthy that, despite differences in theoretical language and etiological assumptions, there is a practical consensus on the general principles of treatment. Some of them I will briefly describe here (compare with Paris, 2008).

Some of them I will briefly describe here (compare with Paris, 2008).

Boundary maintenance and emotional containment

Although the capacity for trust is greater in borderline patients than in psychotic patients, and therefore the therapist is less likely to be required to demonstrate that the patient can feel safe in the counseling room, it may take them up to several years to establish the kind of therapeutic alliance that a neurotic client may experience within minutes of meeting a therapist. The borderline client, by definition, lacks an integrated observing ego that sees many things in the same light as the therapist. Instead, the patient is subject to a chaotic tossing of various ego states, unable to integrate disparate views. While the psychotic seeks psychological fusion with the clinician and the neurotic seeks to maintain his identity, the borderline vacillates—confusingly for himself and those around him—between symbiotic attachment and hostile, isolated separation. Both states cause suffering: one awakens a premonition of absorption, the other of emptiness.

Both states cause suffering: one awakens a premonition of absorption, the other of emptiness.

Given the instability of the ego state, a critical aspect of treatment with borderline patients is the establishment of uniform conditions for therapy—what Langs (1973) called the therapeutic framework. It includes not only time and pay arrangements, but also many other relationship boundary issues that rarely come up when working with other clients. All major therapies for BPD have mechanisms (contracts, consequences, treatment rules, ways to limit self-destructive behavior) to maintain treatment through explicit limiting conditions. Patients of a neurotic or psychotic level can be handled more flexibly.

Common requests from border clients might be: “Can I call you at home?” “What if I want to kill myself?” you in the waiting room?", "Could you write to my professor and tell me that I'm too stressed out to take the exam?" Some of these problems are formulated as questions; others arise in the form of action (for example, the therapist finds the client asleep on the floor in the waiting room). The ways to test boundaries when working with borderline patients are endless, and it is critically important for the therapist to know that what is important is not what is important.0206 what conditions to (they may vary depending on the patient's personality, therapist's preferences and the situation), and that conditions must be must be constantly monitored and supported by specific sanctions if the patient does not show respect for them. For people with separation-individuation problems, connivance creates more anxiety than containment, much like teenagers whose parents do not insist on responsible behavior. Without clear boundaries, they tend to escalate until they find the boundaries that have remained unspoken all along.

The ways to test boundaries when working with borderline patients are endless, and it is critically important for the therapist to know that what is important is not what is important.0206 what conditions to (they may vary depending on the patient's personality, therapist's preferences and the situation), and that conditions must be must be constantly monitored and supported by specific sanctions if the patient does not show respect for them. For people with separation-individuation problems, connivance creates more anxiety than containment, much like teenagers whose parents do not insist on responsible behavior. Without clear boundaries, they tend to escalate until they find the boundaries that have remained unspoken all along.

Borderline clients often react angrily to the therapist's boundaries, but in any case they receive two therapeutic messages: (1) the therapist considers the patient an adult and is confident in their ability to tolerate frustration, and (2) the therapist refuses to be exploited and thus serves self-respect model. Often people on the borderline have a history of receiving a lot of conflicting messages; they found encouragement in moments of regression (and usually ignored in more mature behavior), and they were expected to be able to exploit and allowed to exploit.

Often people on the borderline have a history of receiving a lot of conflicting messages; they found encouragement in moments of regression (and usually ignored in more mature behavior), and they were expected to be able to exploit and allowed to exploit.

When I first started to practice, I was struck by the amount of deprivation and trauma experienced by borderline clients. I tended to see them as thirsty and needy rather than aggressive and angry, and in the hope of compensating for their difficulties, I tried to jump above my own head. I realized that the more I gave, the more they regressed and the more frustrated I felt. Over time, I learned to stick to the established framework, no matter how cruel it may seem. I did not allow the sessions to go on longer than they were supposed to, even if, for example, the patient had just fallen into a state of intense grief. Instead, I learned to gently but firmly end a session on time and listen to the patient's anger at being kicked out the next time. If borderline patients began to chastise me for my rigid, selfish rules, I noticed that they fared better than when I tried to get them to appreciate my generosity, which is an internally infantilizing attitude.

If borderline patients began to chastise me for my rigid, selfish rules, I noticed that they fared better than when I tried to get them to appreciate my generosity, which is an internally infantilizing attitude.

Therapists who are new to working with borderline patients often ask when all preparations for therapy will be completed and real therapy will begin. It must be painful to realize that all this work on the conditions of therapy is therapy. The beginner wonders when the borderline patient will "calm down". Tension characterizes all work with borderline patients, and it is critical that the therapist be able to tolerate or "contain" this tension, even when it includes verbal attacks against the therapist (Bion, 1962; Charles, 2004). Once an alliance of the neurotic type is reached, the patient will, by definition, take a giant step in development. Having to spend so much time asking questions of boundaries when working with people who are often bright, talented, and spectacular is quite disconcerting, especially when these questions stimulate overflowing reactivity. Petty fighting from abroad is hardly what we meant by "doing therapy" when we decided to go into this field. Therefore, people working with their first frontier clients may suffer from occasional flare-ups of self-doubt.

Petty fighting from abroad is hardly what we meant by "doing therapy" when we decided to go into this field. Therefore, people working with their first frontier clients may suffer from occasional flare-ups of self-doubt.

When working with borderline clients, it is usually best to work face to face, even with those who are attracted to psychoanalysis and want to 'dig deeper'. Although they are not subject to the overflowing transferences that characterize psychotic patients, they have more than enough anxiety without the therapist sitting out of their sight. For the recovery of more difficult patients, being able to see the reflection of emotion on the therapist's face can also be critical. Analyzing video recordings of sessions with clients who had previous experiences of therapy failure, Krause and colleagues (e.g., Anstadt, Merten, Ullrich & Krause, 1997) found that regardless of the therapist's orientation, improvements were correlated with the client's ability to see "mismatched" emotions on the therapist's face. For example, when the client's face showed shame, the therapist's face might express anger at someone shaming the client; when fear appeared on the client's face, the therapist's face might express curiosity about that fear. Also, again, since the energy of borderline clients does not need to be rewarded, only unusual circumstances (such as the need for increased support in withdrawal from addiction) may require borderline clients to be treated more than three times a week, as in classical psychoanalysis.

For example, when the client's face showed shame, the therapist's face might express anger at someone shaming the client; when fear appeared on the client's face, the therapist's face might express curiosity about that fear. Also, again, since the energy of borderline clients does not need to be rewarded, only unusual circumstances (such as the need for increased support in withdrawal from addiction) may require borderline clients to be treated more than three times a week, as in classical psychoanalysis.

Voicing contrasting states of feeling

The second thing to pay close attention to with borderline clients is the therapist's speaking style. With neurotic patients, the specialist's comments may be infrequent and intended to have maximum effect ("less is more"). With healthier clients, noting the other side of the conflict, in which the client is aware of only one feeling, can be spoken concisely and emotionally subdued (Colby, 1951; Fenichel, 1941; Hammer, 1968). For example, a woman on the neurotic spectrum may enthusiastically vent about her friend, with whom she is in a somewhat competitive relationship, in such a way that she does not feel any negative emotions. The therapist might say something like, "But you would also like to nail her," along the way. Or a man may rant about how independent and free he is; the therapist might comment, "Yet you worry all the time about what I think of you."

For example, a woman on the neurotic spectrum may enthusiastically vent about her friend, with whom she is in a somewhat competitive relationship, in such a way that she does not feel any negative emotions. The therapist might say something like, "But you would also like to nail her," along the way. Or a man may rant about how independent and free he is; the therapist might comment, "Yet you worry all the time about what I think of you."

In these cases, neurotic clients know that the therapist has revealed some of their subjective experiences that they have been keeping out of awareness. Because they can appreciate that the clinician is not trying to belittle them, is not claiming that their unacknowledged attitude is their real feeling and that their conscious ideas are illusory, as a result of this interpretation they may feel that their awareness has increased. They feel understood. , even if slightly hurt. But borderline clients who are spoken to in this way feel they are criticized and belittled, because if the phrase is not reformulated, the main message they receive will be: “You are completely wrong about how you really feel. ” . This response comes from their tendency to be in one or the other ego state, but not in a state of consciousness that can live and endure ambivalence and uncertainty.

” . This response comes from their tendency to be in one or the other ego state, but not in a state of consciousness that can live and endure ambivalence and uncertainty.

For these reasons, beginning therapists often find themselves in a situation where they think they are expressing caring understanding, but notice that the borderline patient reacts as if he is being attacked. One way to get around this problem is to recognize that the BORD lacks the reflective capacity to perceive an interpretation as additional information about itself, and therefore needs to give this function to the interpretation itself. Therefore, the patient is more likely to hear empathy in the words: “I can see how much Mary means to you. However, is it possible that there is also another part of you - a part that you certainly will not be guided by - that you would like to get rid of it, since it is in some way competing with you? Or: “You definitely say that you are characterized by independence and self-confidence. Interestingly, it seems to co-exist with some opposing tendencies, such as being sensitive to my opinion of you." Such interventions lack the punch and beauty of laconic expressions, but given the peculiarities of the psychological problems of borderline people, they are the ones who are more likely to achieve the goal.

Interestingly, it seems to co-exist with some opposing tendencies, such as being sensitive to my opinion of you." Such interventions lack the punch and beauty of laconic expressions, but given the peculiarities of the psychological problems of borderline people, they are the ones who are more likely to achieve the goal.

Interpretation of primitive defenses

The third feature of effective psychoanalytic therapy with borderline patients is the interpretation of primitive defenses as they arise. This work does not fundamentally differ from ego-psychological work with neurotic patients: we analyze defense processes as they arise in the transference. But because the borderline's defenses are so primitive, and also because they can manifest in quite different ways in different ego states, the analysis of these defenses requires a special approach.

With borderline clients, "genetic" (historical) interpretations, in which transference reactions are associated with feelings belonging to a figure from the client's past, are rarely helpful. With clients at the neurotic level, one can greatly benefit from a comment such as: "Perhaps you are so angry with me because you perceive me as your mother." The patient may agree, notice differences between therapist and mother, and be interested in other cases in which this association might be relevant. With borderline patients, reactions can range from "So what?" (which can mean "You look so much like my mother, why should I react differently?") to "So how can this help me?" (which could mean "You're just spouting your psychiatric rubbish. When will you finally start helping me?") or "Sure!" (which can mean “Well, finally you understand everything. The problem is my mother, I want to change her!”). Such reactions can be confusing, disarming, and discouraging for young therapists, especially if genetic interpretations have been a useful aspect of the therapist's personal psychotherapeutic experience.

With clients at the neurotic level, one can greatly benefit from a comment such as: "Perhaps you are so angry with me because you perceive me as your mother." The patient may agree, notice differences between therapist and mother, and be interested in other cases in which this association might be relevant. With borderline patients, reactions can range from "So what?" (which can mean "You look so much like my mother, why should I react differently?") to "So how can this help me?" (which could mean "You're just spouting your psychiatric rubbish. When will you finally start helping me?") or "Sure!" (which can mean “Well, finally you understand everything. The problem is my mother, I want to change her!”). Such reactions can be confusing, disarming, and discouraging for young therapists, especially if genetic interpretations have been a useful aspect of the therapist's personal psychotherapeutic experience.

With borderline patients, one can safely interpret the emotional situation here and now. For example, when anger spreads in the therapeutic dyad, it is likely that the patient's defense is not a substitution or a direct projection, as was the case in the previous example of the neurotic patient with the mother transference; instead, the patient appears to be using projective identification. The patient tries to get rid of the feeling of "bad self" (Sullivan, 1953) and the associated emotion of rage by transferring them to the therapist, but the transference of image and emotion does not occur "purely"; the client retains a sense of "worthlessness" and anger despite the projection. This is a painful price for an inferior psychological separation—a price that the borderline person pays and that the psychotherapist inevitably shares.

For example, when anger spreads in the therapeutic dyad, it is likely that the patient's defense is not a substitution or a direct projection, as was the case in the previous example of the neurotic patient with the mother transference; instead, the patient appears to be using projective identification. The patient tries to get rid of the feeling of "bad self" (Sullivan, 1953) and the associated emotion of rage by transferring them to the therapist, but the transference of image and emotion does not occur "purely"; the client retains a sense of "worthlessness" and anger despite the projection. This is a painful price for an inferior psychological separation—a price that the borderline person pays and that the psychotherapist inevitably shares.

Consider how borderline clients differ critically from both neurotic and psychotic clients. The psychotic client is detached enough from reality not to care whether the projection "fits" the person. A neurotic person has an observing ego that is able to notice that he is currently projecting something. Borderline patients cannot successfully get rid of the sensation of projection. They cannot remain indifferent to how realistic the material being projected is because, unlike psychotics, they have retained the skill of testing reality. And they cannot put it on the unconscious part of the ego, because, unlike neurotics, instead of using repression, they switch between states. Therefore, they continue to feel what they are projecting along with the need make it fit the person so they don't feel crazy. The therapist accepts the client's anger (or other strong emotion) and while the client tries to "fit" the projection by insisting that he is angry because of the therapist's hostility, the therapist begins to feel angry because he is not understood. Because of these transactions, borderline clients get a bad rap among many mental health professionals, even though they are not always unpleasant people and can usually be treated appropriately.

Borderline patients cannot successfully get rid of the sensation of projection. They cannot remain indifferent to how realistic the material being projected is because, unlike psychotics, they have retained the skill of testing reality. And they cannot put it on the unconscious part of the ego, because, unlike neurotics, instead of using repression, they switch between states. Therefore, they continue to feel what they are projecting along with the need make it fit the person so they don't feel crazy. The therapist accepts the client's anger (or other strong emotion) and while the client tries to "fit" the projection by insisting that he is angry because of the therapist's hostility, the therapist begins to feel angry because he is not understood. Because of these transactions, borderline clients get a bad rap among many mental health professionals, even though they are not always unpleasant people and can usually be treated appropriately.

An interpretation that might affect a borderline person in this situation would probably be: “You seem to be convinced that you are a bad person. You get angry about it and link the anger to the fact that I'm really bad, and that my anger causes your anger. Try to imagine that both of us have both good and bad, and that all this is not so scary. This is an example of a primitive defense confrontation here and now. It represents the therapist's attempt, which will have to be repeated in various forms over several months at most, to help the patient move from a psychology in which everything is black and white, "all or nothing", to one in which the various aspects of the self, good and bad, and a range of emotions are consolidated within a single concept of "I". This type of intervention is not easy for most people, but fortunately the practice pays off.

You get angry about it and link the anger to the fact that I'm really bad, and that my anger causes your anger. Try to imagine that both of us have both good and bad, and that all this is not so scary. This is an example of a primitive defense confrontation here and now. It represents the therapist's attempt, which will have to be repeated in various forms over several months at most, to help the patient move from a psychology in which everything is black and white, "all or nothing", to one in which the various aspects of the self, good and bad, and a range of emotions are consolidated within a single concept of "I". This type of intervention is not easy for most people, but fortunately the practice pays off.

Obtaining supervision from the patient

The fourth dimension of working with borderline clients is that I have found it helpful to ask the patient to help resolve the "either/or" dilemmas that often confront the therapist. This technique, where the specialist asks the patient to be their supervisor, is directly related to the all-or-nothing approach inherent in the borderline patient's picture of the world.