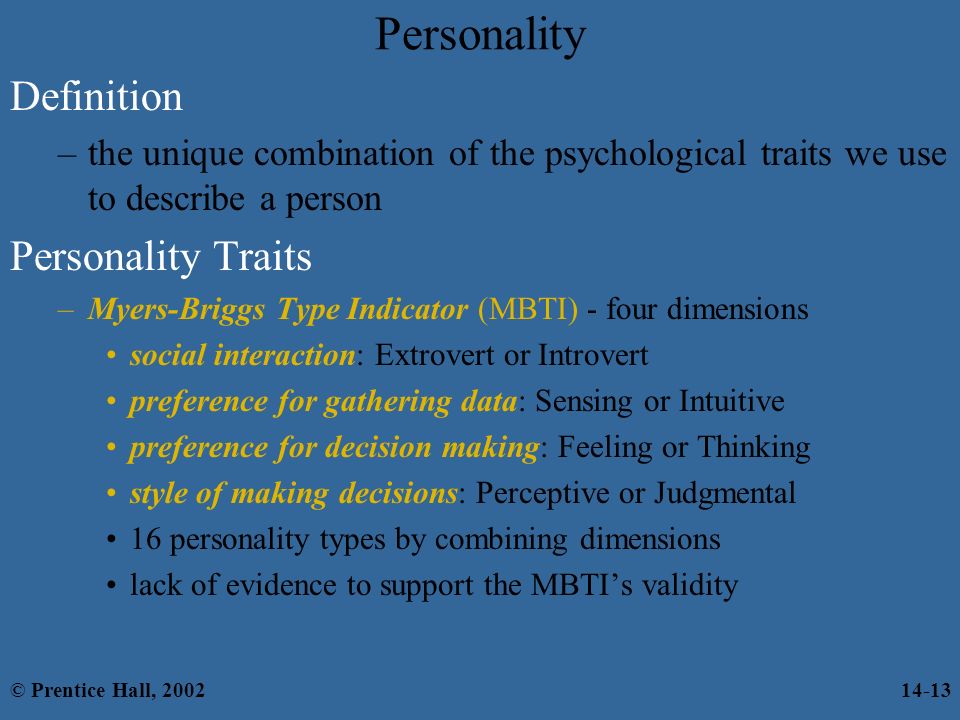

Stable personality definition

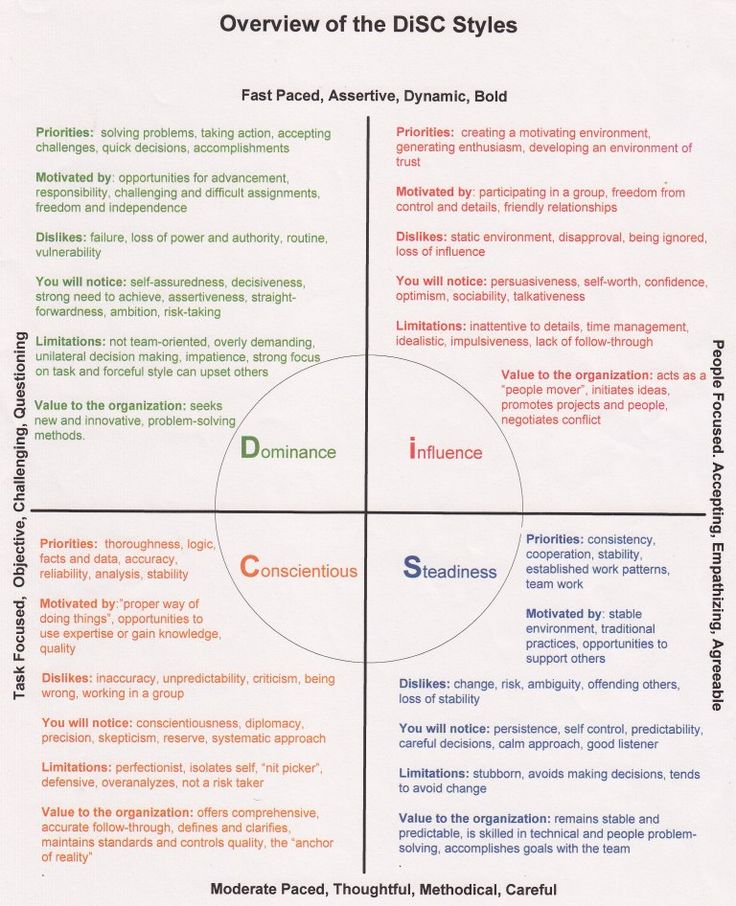

DISC: The Stable “S” Personality Type

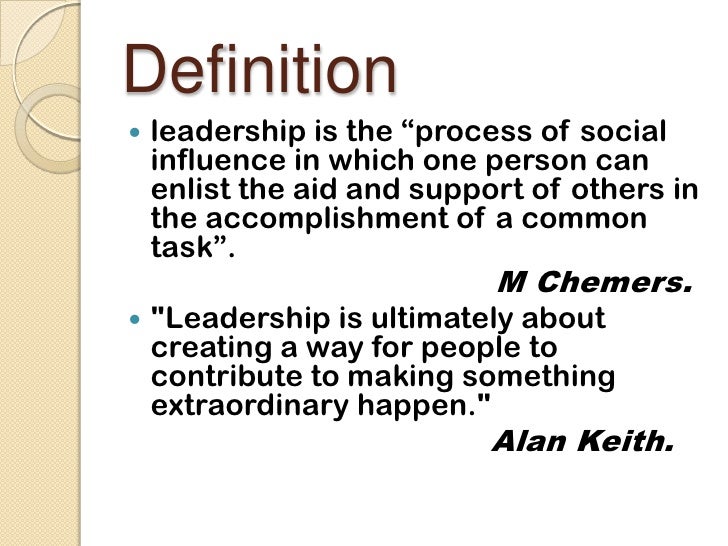

DISC-the Stable Personality TypeOne of the most powerful things we can do to foster personal growth as well as create a highly functioning team environment is to understand our personality type as well as that of our colleagues. At LIFT Leadership, we achieve this by using the DISC Method to determine individual temperaments and educate about effective ways to communicate, how to maximize strengths and overcome our areas for improvement.

The DISC model does not define a person but rather offers insights into their perspective, how they think, and communicate, especially when under pressure or not at their best.

There are four main personality types defined by DISC:

D – dominant, driver

I – influencer, inspiring

S – stable, supportive

C – compliant, cautious

We all have characteristics of each temperament, but it is common for one or two to be more prevalent. In this blog, we will take a deeper dive into the “S” or stable personality type.

STRENGTHS

Those possessing a stable personality are by nature good listeners, team players, and reliable. These friendly individuals are patient, empathetic, and, because they are extremely understanding, they tend to excel at mediating conflict. “S” personality types are genuine and authentic. As their moniker suggests, they provide a predictable steadiness, which can serve as a steadfast anchor in a team environment.

These individuals flourish in team settings, especially when working with a group with whom they connect and have established trust. An ”S” will work toward achieving a harmonious atmosphere, reconciliation of conflicts, and attaining a consensus on important decisions. They excel at multi-tasking, appreciate practical procedures and systems, and love seeing projects and tasks to completion.

WEAKNESSES

Stable personalities often tend to be resistant to change, and when changes inevitably occurs, it takes them longer to acclimate. These people are typically rule followers and people pleasers, which can lead them to overcommit, place other’s needs above their own, or have trouble establishing priorities. They may have trouble not taking criticism personally and, when they feel frustrated or resentful, may hold grudges rather than address an issue head-on.

These people are typically rule followers and people pleasers, which can lead them to overcommit, place other’s needs above their own, or have trouble establishing priorities. They may have trouble not taking criticism personally and, when they feel frustrated or resentful, may hold grudges rather than address an issue head-on.

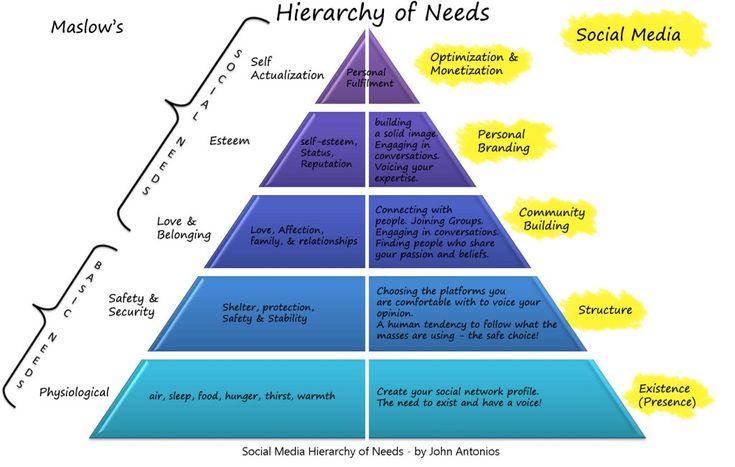

Stable temperaments are most afraid of feeling insecure and will do whatever possible to keep their security intact. If they feel their security is under attack, they may withdraw from the situation as a protection mechanism. An “S” most appreciates stability and routine in their lifestyle as well as any processes they deal with in their career. As such, they find sudden changes unnerving. It is best to provide a stable personality type with enough time to adjust to any changes rather than springing it upon them without notice.

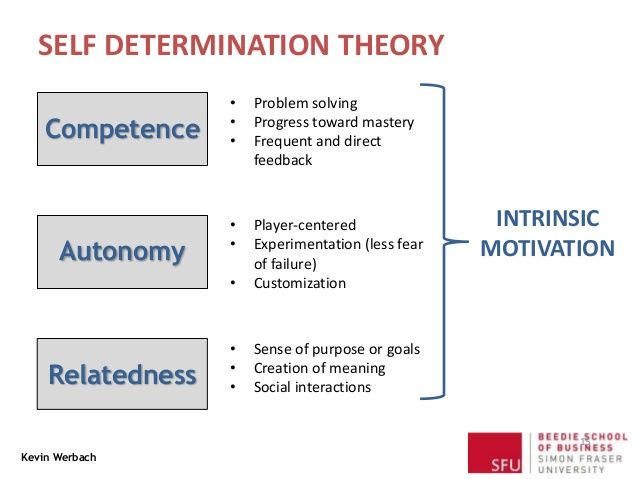

MOTIVATIONS

Safety and security are the keystones of an “S” personality. They are highly motivated by activities they can start and complete versus those that change direction frequently. They desire recognition for the dependability and loyalty as they truly strive to provide both of these characteristics in their work and personal lives.

They are highly motivated by activities they can start and complete versus those that change direction frequently. They desire recognition for the dependability and loyalty as they truly strive to provide both of these characteristics in their work and personal lives.

HOW TO COMMUNICATE WITH OTHER PERSONALITY TYPES

“D” – Although it may not come naturally, be more assertive, straightforward, and speak more quickly. Focus on facts not feelings. Tap into your innate ability to use systems to deliver results efficiently.

“I” – Be friendly and complimentary. Listen to their ideas. Recognize and appreciate their accomplishments. Be enthusiastic.

“S” – Create a friendly, welcoming atmosphere. Cultivate mutual trust and a harmonious team environment. Be appreciative. Collaborate on ways to create efficiency.

“C” – Communicate one topic at a time in a factual manner. Keep feelings and relationships out of the conversation-instead focus on data and facts. Expect to be questioned for additional data-gathering and allow enough time to evaluate information before expecting a decision.

Expect to be questioned for additional data-gathering and allow enough time to evaluate information before expecting a decision.

AREAS FOR PERSONAL GROWTH

Stable personality types may need to work on establishing personal boundaries. Their inclination is to be overly agreeable often to please others, which can lead to them taking on unwanted or unnecessary work or responsibilities. These individuals may need to be more direct and intentional about expressing their thoughts, concerns, and wants, not only to avoid overtasking themselves but to clear up miscommunications and dispel the possibility of harboring resentment.

An “S” also needs time as well as the reasoning behind alterations in projects, processes, systems or anything that might impact them directly. This will enable them to better grasp, accept, and adjust to change.

To perform at their best, people with stable personalities need an environment that provides safety and security, along with enough time to acclimate to change. Friendly, loyal team players, these individuals are great mediators, multi-taskers, and will help drive a group toward a consensus. They are understanding and empathetic, reliable and authentic, and can always be counted on to truly listen. They are innately adept at finding the middle ground and helping people feel comfortable and connected.

Friendly, loyal team players, these individuals are great mediators, multi-taskers, and will help drive a group toward a consensus. They are understanding and empathetic, reliable and authentic, and can always be counted on to truly listen. They are innately adept at finding the middle ground and helping people feel comfortable and connected.

Wondering if you might have a stable personality? Contact LIFT Leadership to schedule a comprehensive DISC assessment to learn more about you!

Copyright © LIFT Leadership 2019 All rights reserved.

Personality Stability – The Balance of Personality

This is an edited and adapted chapter from Donnellan, M. B. (2019) in the NOBA series on psychology. For full attribution see end of chapter.

This module describes different ways to address questions about personality stability across the lifespan. Definitions of the major types of personality stability are provided, and evidence concerning the different kinds of stability and change are reviewed. The mechanisms thought to produce personality stability and personality change are identified and explained.

The mechanisms thought to produce personality stability and personality change are identified and explained.

Learning Objectives

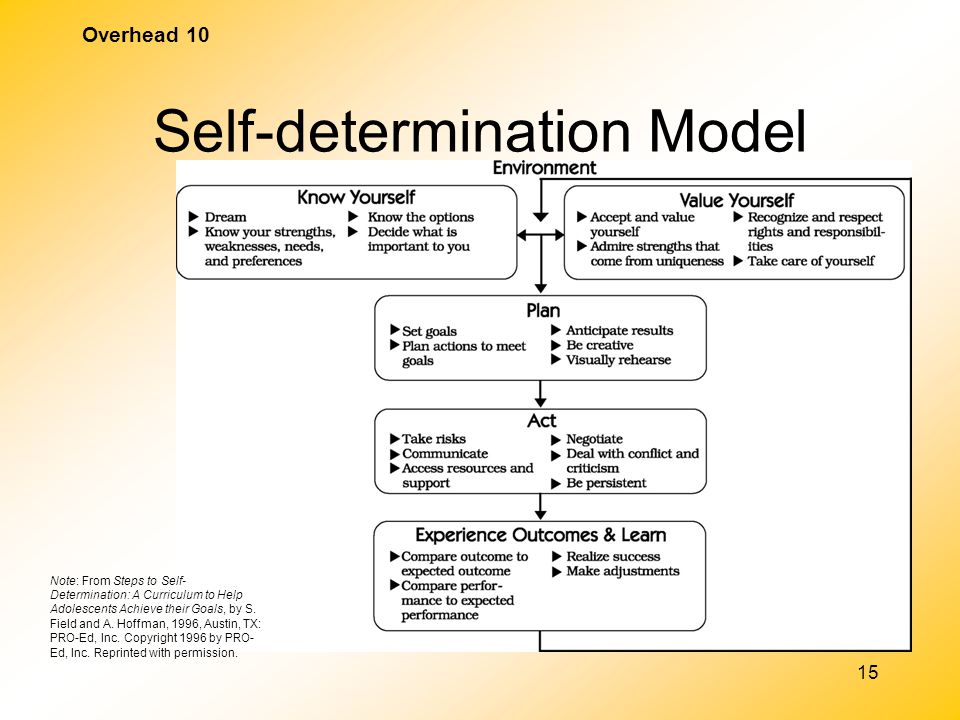

- Explain the maturity, cumulative continuity, and corresponsive principles of personality development.

- Explain person-environment transactions, and distinguish between active, reactive, and evocative person-environment transactions.

- Identify the four processes that promote personality stability (attraction, selection, manipulation, and attrition). Provide examples of these processes.

- Describe the mechanisms behind the possibility of personality transformation.

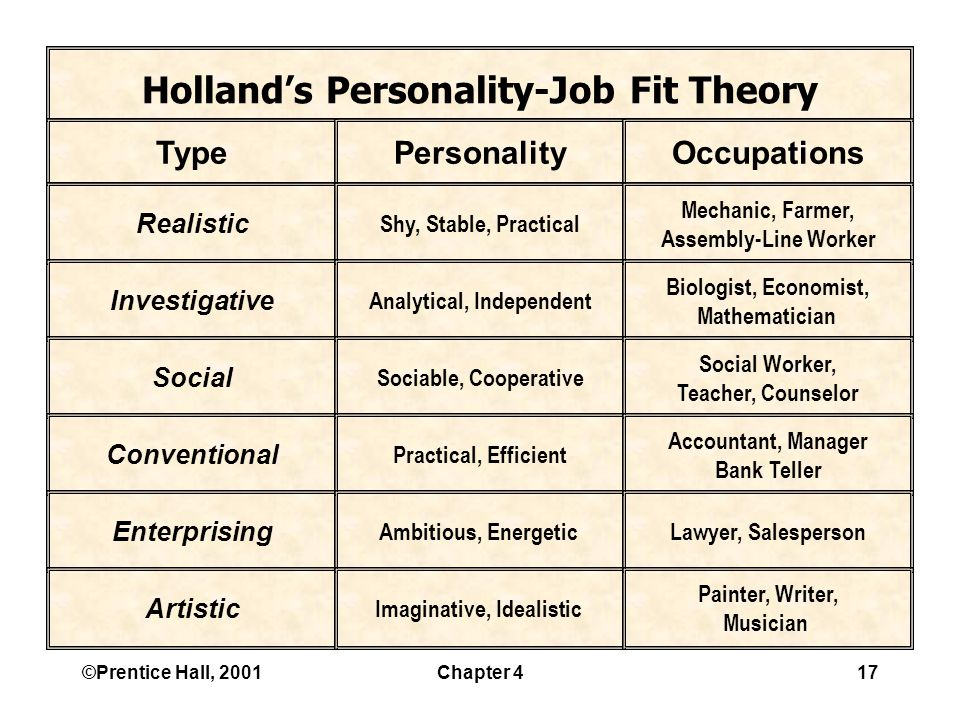

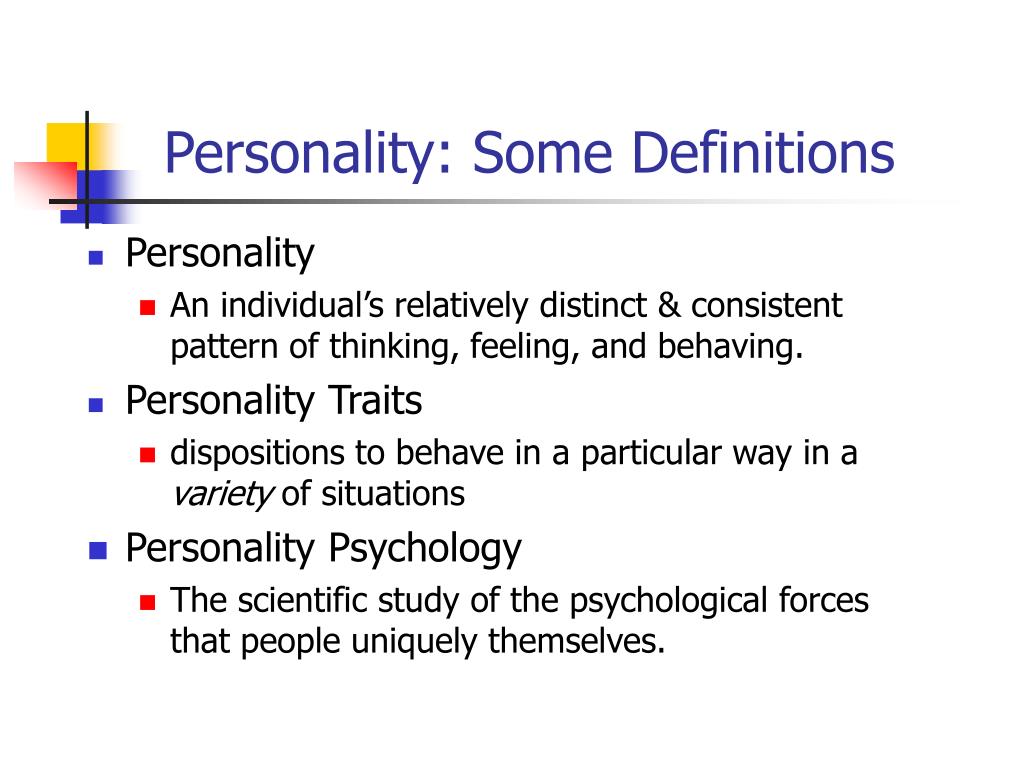

Personality psychology is about how individuals differ from each other in their characteristic ways of thinking, feeling, and behaving. Some of the most interesting questions about personality attributes involve issues of stability and change. Are shy children destined to become shy adults? Are the typical personality attributes of adults different from the typical attributes of adolescents? Do people become more self-controlled and better able to manage their negative emotions as they become adults? What mechanisms explain personality stability and what mechanisms account for personality change?

Some of the most interesting questions about personality attributes involve issues of stability and change. Are shy children destined to become shy adults? Are the typical personality attributes of adults different from the typical attributes of adolescents? Do people become more self-controlled and better able to manage their negative emotions as they become adults? What mechanisms explain personality stability and what mechanisms account for personality change?

Something frustrating happens when you attempt to learn about personality stability[1]: As with many topics in psychology, there are a number of different ways to conceptualize and quantify personality stability (e.g., Caspi & Bem, 1990; Roberts, Wood, & Caspi, 2008). This means there are multiple ways to consider questions about personality stability. Thus, the simple (and obviously frustrating) way to respond to most blanket questions about personality stability is to simply answer that it depends on what one means by personality stability. To provide a more satisfying answer to questions about stability, I will first describe the different ways psychologists conceptualize and evaluate personality stability. I will make an important distinction between heterotypic and homotypic stability. I will then describe absolute and differential stability, two ways of considering homotypic stability. I will also draw your attention to the important concept of individual differences in personality development.

To provide a more satisfying answer to questions about stability, I will first describe the different ways psychologists conceptualize and evaluate personality stability. I will make an important distinction between heterotypic and homotypic stability. I will then describe absolute and differential stability, two ways of considering homotypic stability. I will also draw your attention to the important concept of individual differences in personality development.

Heterotypic stability refers to the psychological coherence of an individual’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors across development. Questions about heterotypic stability concern the degree of consistency in underlying personality attributes. The tricky part of studying heterotypic stability is that the underlying psychological attribute can have different behavioral expressions at different ages. (You may already know that the prefix “hetero” means something like “different” in Greek.) Shyness is a good example of such an attribute because shyness is expressed differently by toddlers and young children than adults. The shy toddler might cling to a caregiver in a crowded setting and burst into tears when separated from this caregiver. The shy adult, on the other hand, may avoid making eye contact with strangers and seem aloof and distant at social gatherings. It would be highly unusual to observe an adult burst into tears in a crowded setting. The observable behaviors typically associated with shyness “look” different at different ages. Researchers can study heterotypic continuity only once they have a theory that specifies the different behavioral manifestations of the psychological attribute at different points in the lifespan. As it stands, there is evidence that attributes such as shyness and aggression exhibit heterotypic stability across the lifespan (Caspi, Bem, & Elder, 1989). Individuals who act shy as children often act shy as adults, but the degree of correspondence is far from perfect because many things can intervene between childhood and adulthood to alter how an individual develops.

The shy toddler might cling to a caregiver in a crowded setting and burst into tears when separated from this caregiver. The shy adult, on the other hand, may avoid making eye contact with strangers and seem aloof and distant at social gatherings. It would be highly unusual to observe an adult burst into tears in a crowded setting. The observable behaviors typically associated with shyness “look” different at different ages. Researchers can study heterotypic continuity only once they have a theory that specifies the different behavioral manifestations of the psychological attribute at different points in the lifespan. As it stands, there is evidence that attributes such as shyness and aggression exhibit heterotypic stability across the lifespan (Caspi, Bem, & Elder, 1989). Individuals who act shy as children often act shy as adults, but the degree of correspondence is far from perfect because many things can intervene between childhood and adulthood to alter how an individual develops. Nonetheless, the important point is that the patterns of behavior observed in childhood sometimes foreshadow adult personality attributes.

Nonetheless, the important point is that the patterns of behavior observed in childhood sometimes foreshadow adult personality attributes.

Homotypic stability concerns the amount of similarity in the same observable personality characteristics across time. (The prefix “homo” means something like the “same” in Greek.) For example, researchers might ask whether stress reaction or the tendency to become easily distressed by the normal challenges of life exhibits homotypic stability from age 25 to age 45. The assumption is that this attribute has the same manifestations at these different ages. Researchers make further distinctions between absolute stability and differential stability when considering homotypic stability.

When considering personality stability, researchers can think of it at the individual level (e.g., how is 18-year-old you different than 38-year-old you?) or at the group level (e.g., how are most 18-year-olds different than most 38-year-olds?). [Image: Ken Wytock, https://goo. gl/G1qfcO, CC BY-NC 2.0, https://goo.gl/VnKlK8

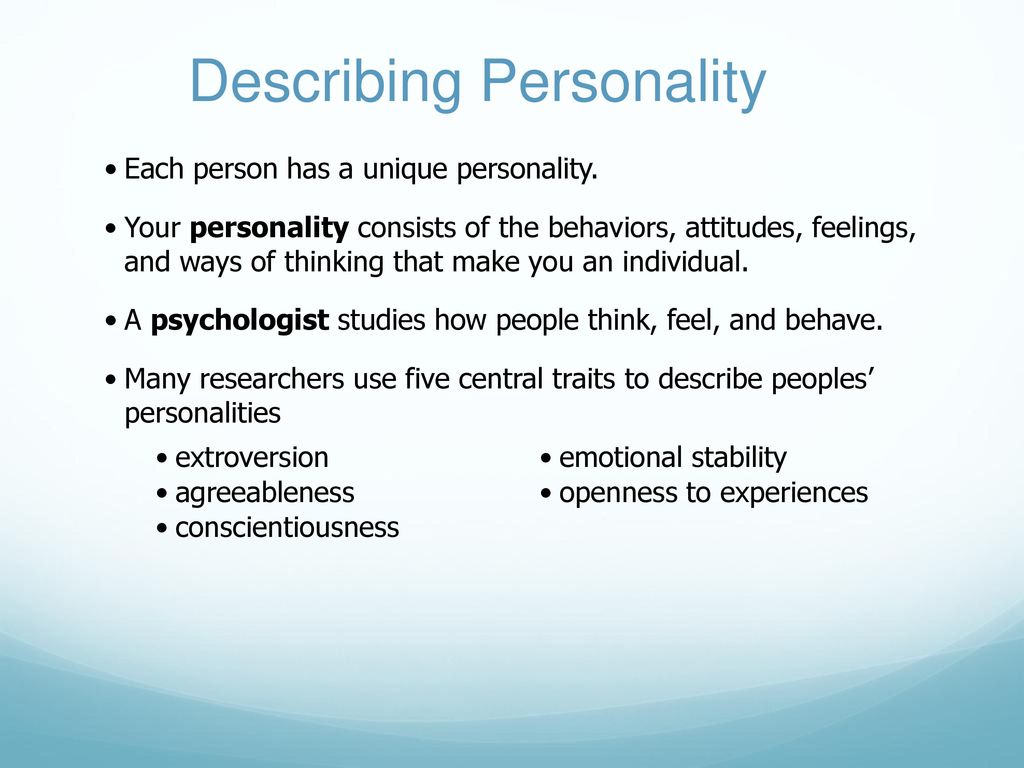

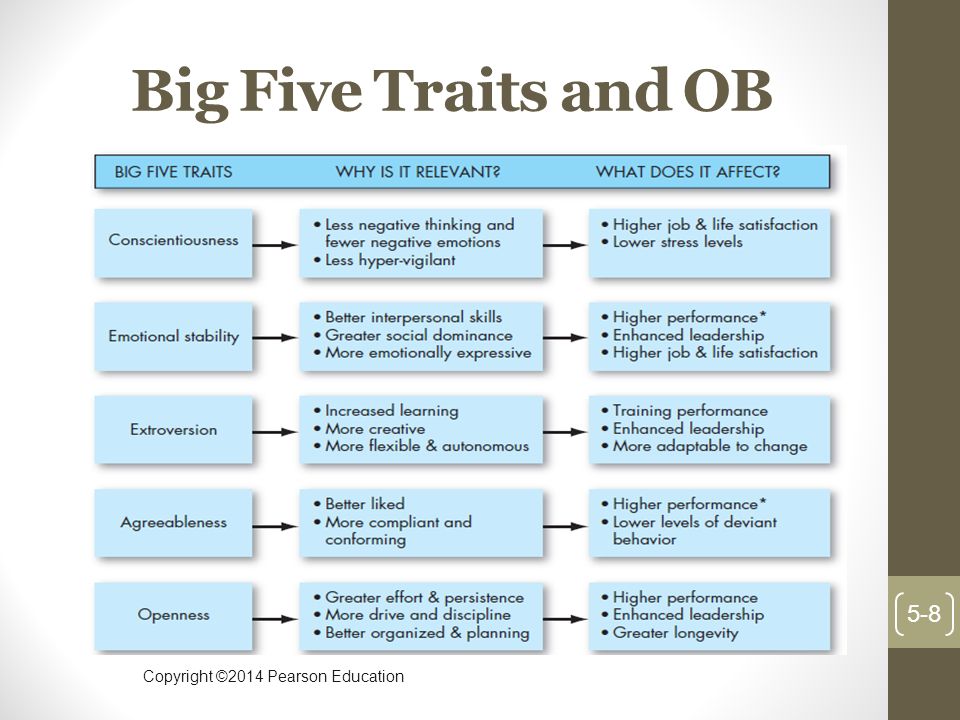

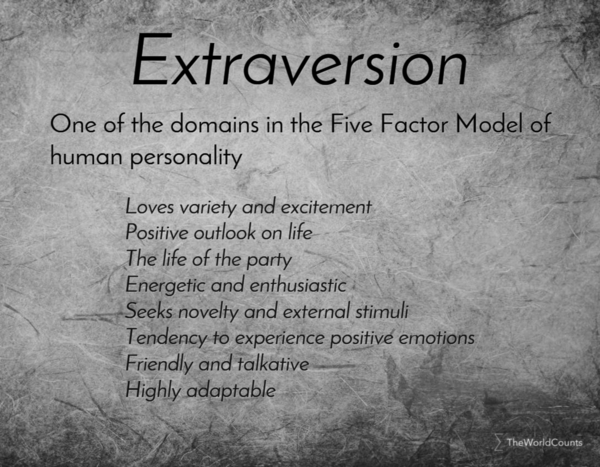

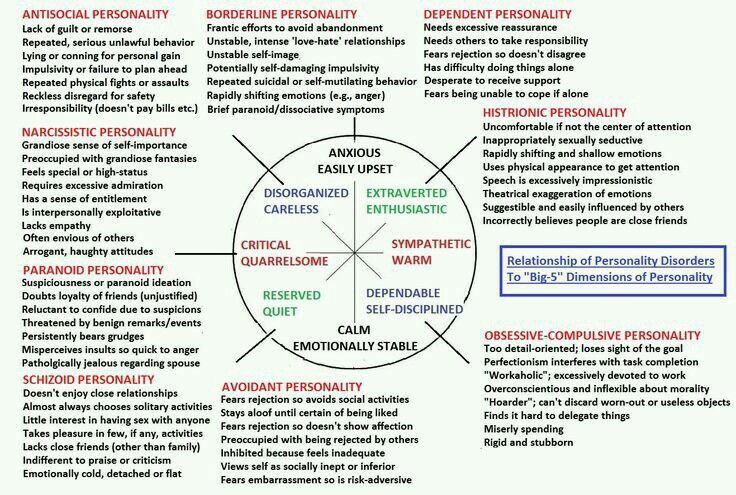

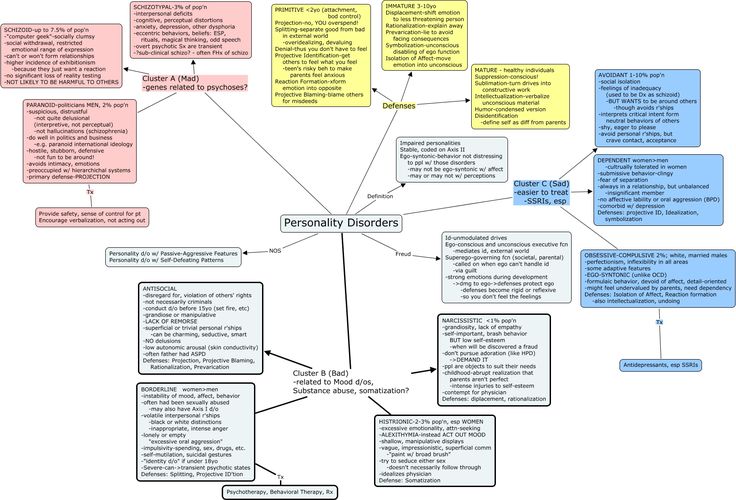

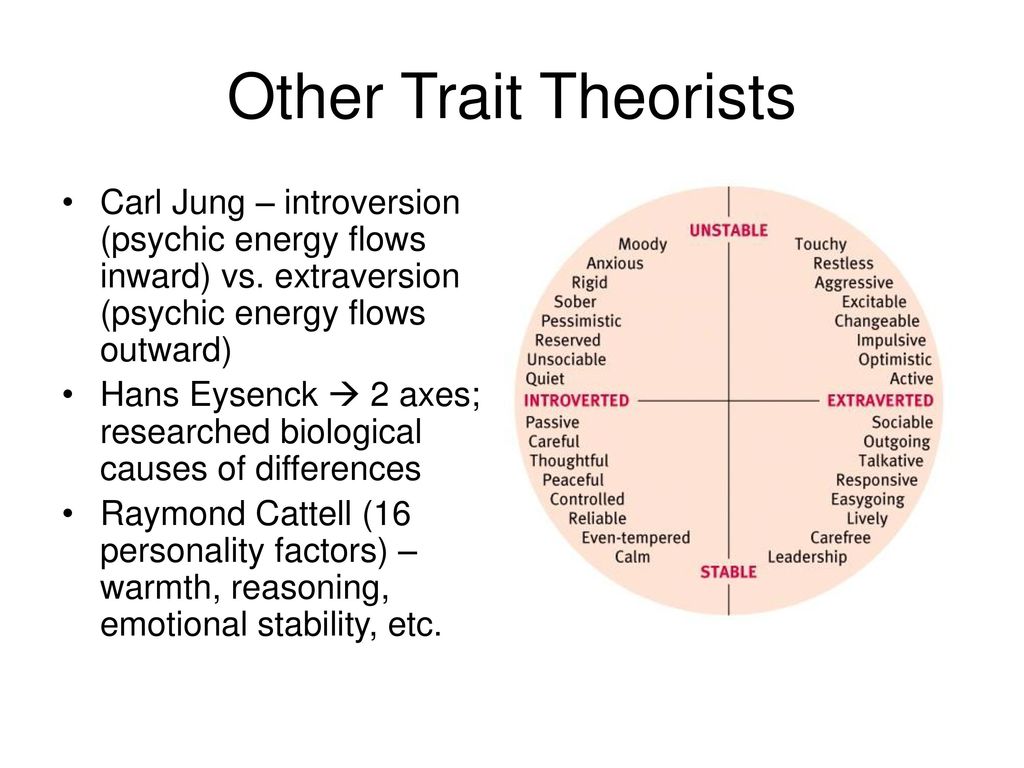

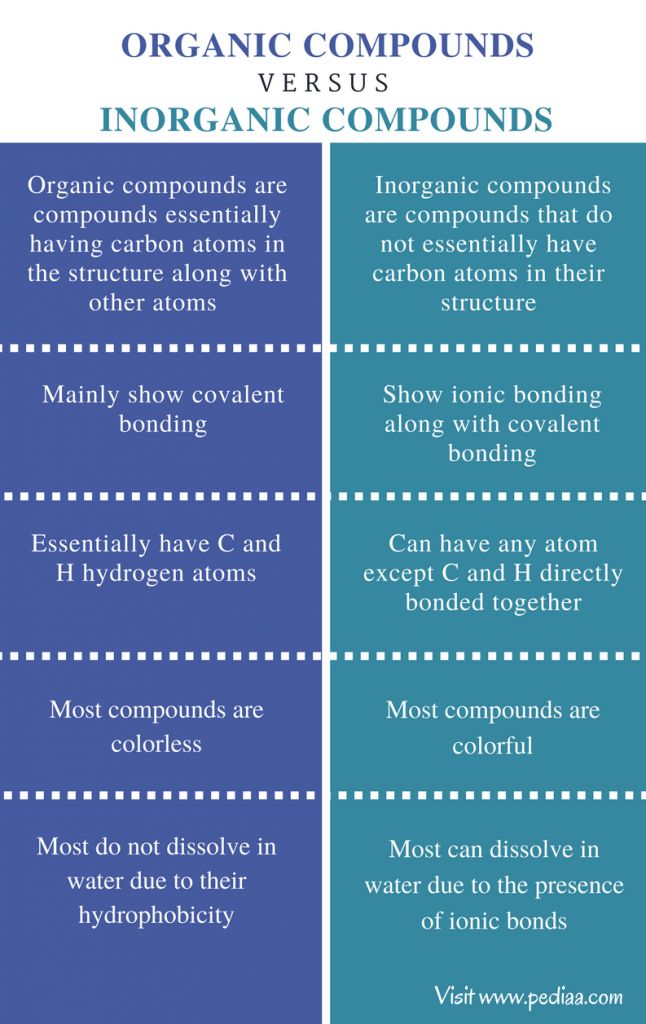

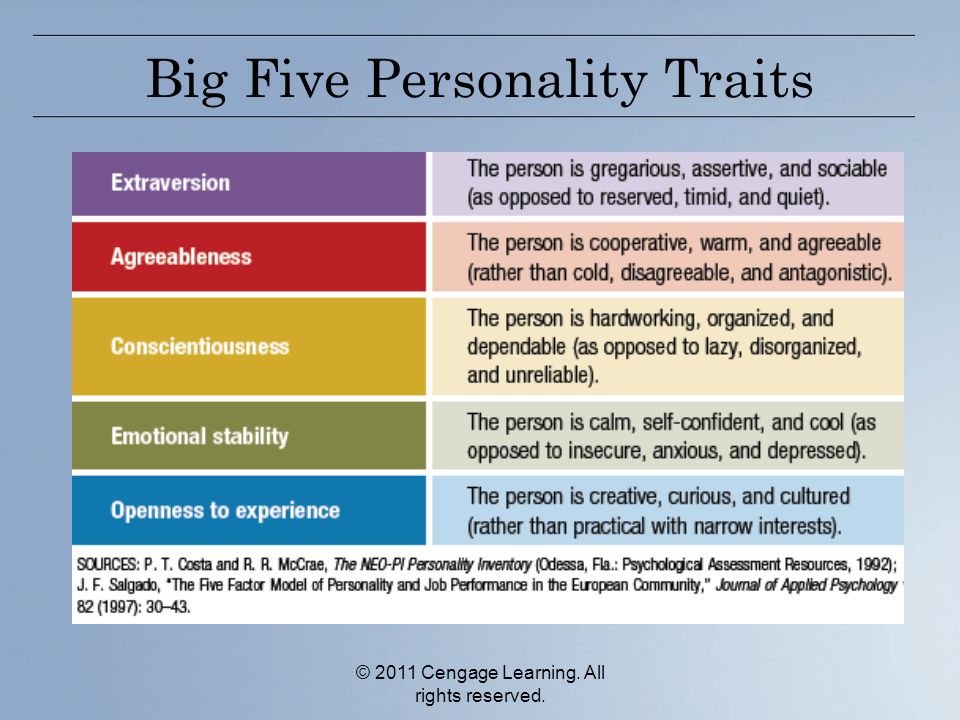

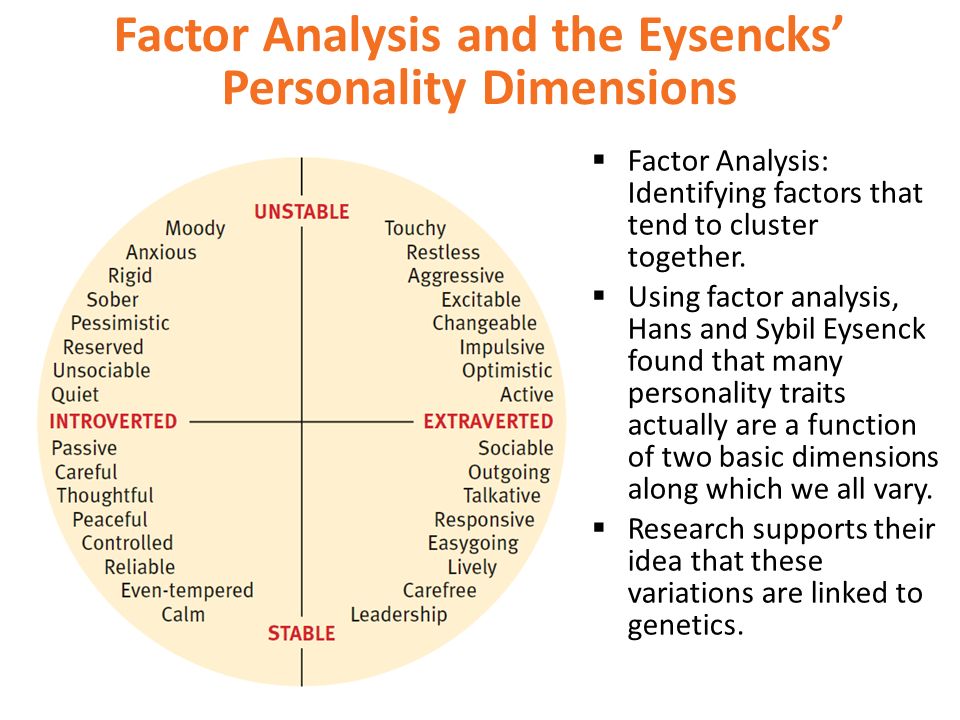

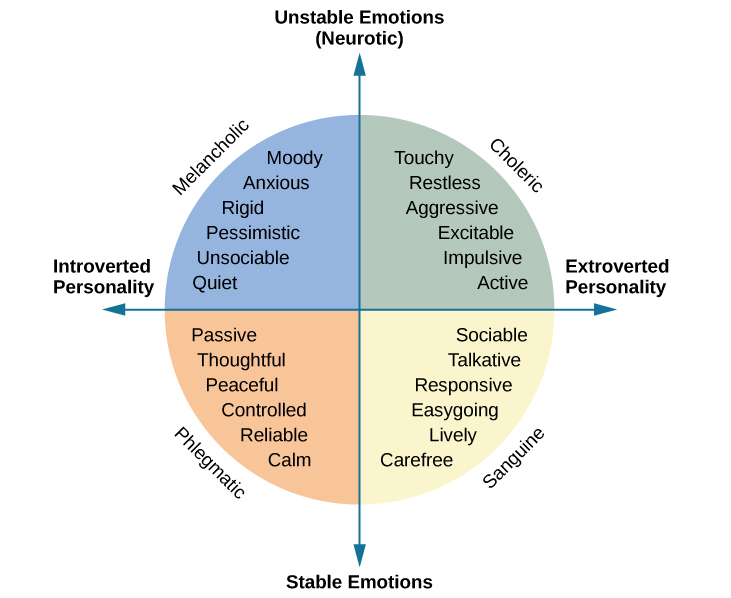

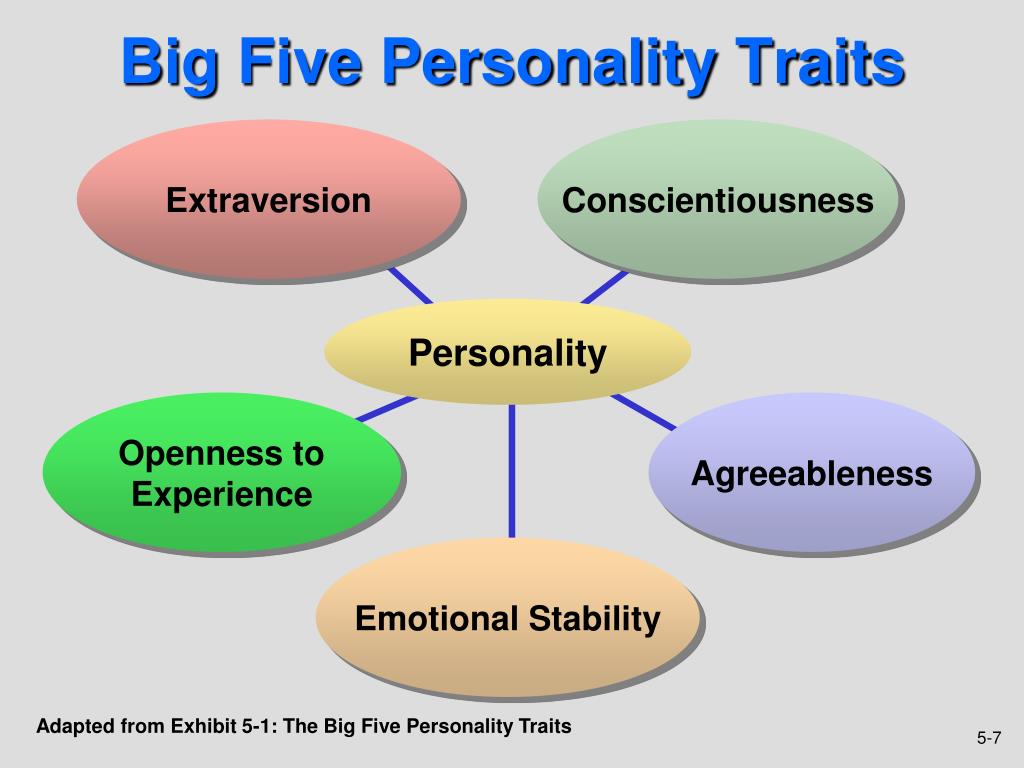

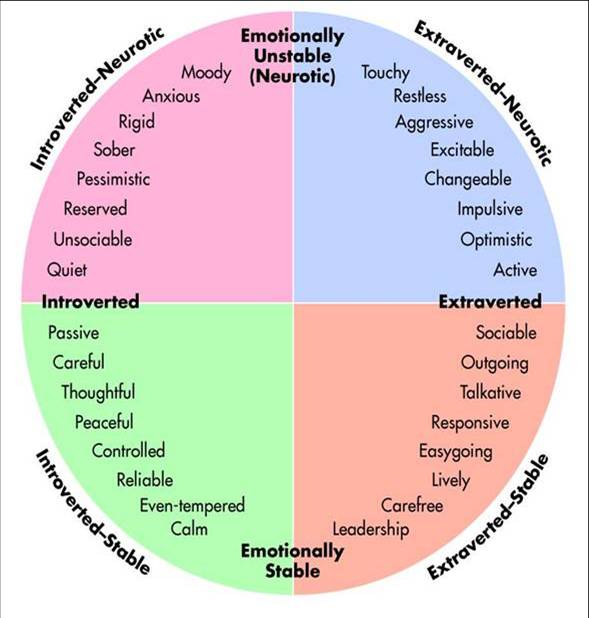

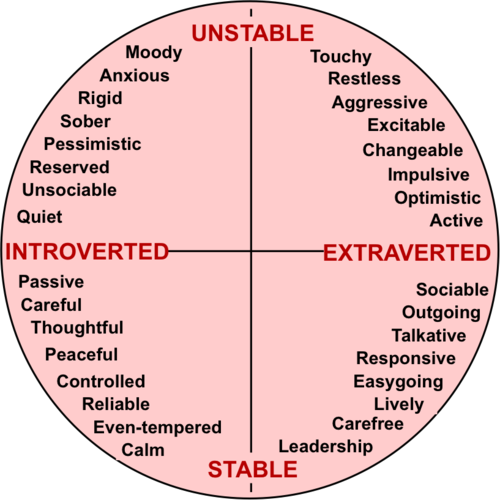

gl/G1qfcO, CC BY-NC 2.0, https://goo.gl/VnKlK8The Big Five domains include extraversion (attributes such as assertive, confident, independent, outgoing, and sociable), agreeableness (attributes such as cooperative, kind, modest, and trusting), conscientiousness (attributes such as hard working, dutiful, self-controlled, and goal-oriented), neuroticism (attributes such as anxious, tense, moody, and easily angered), and openness (attributes such as artistic, curious, inventive, and open-minded). The Big Five is one of the most common ways of organizing the vast range of personality attributes that seem to distinguish one person from the next. This organizing framework made it possible for Roberts et al. (2006) to draw broad conclusions from the literature.

In general, average levels of extraversion (especially the attributes linked to self-confidence and independence), agreeableness, and conscientiousness appear to increase with age whereas neuroticism appears to decrease with age (Roberts et al. , 2006). Openness also declines with age, especially after mid-life (Roberts et al., 2006). These changes are often viewed as positive trends given that higher levels of agreeableness and conscientiousness and lower levels of neuroticism are associated with seemingly desirable outcomes such as increased relationship stability and quality, greater success at work, better health, a reduced risk of criminality and mental health problems, and even decreased mortality (e.g., Kotov, Gamez, Schmidt, & Watson, 2010; Miller & Lynam 2001; Ozer & Benet-Martínez, 2006; Roberts, Kuncel, Shiner, Caspi, & Goldberg, 2007). This pattern of positive average changes in personality attributes is known as the maturity principle of adult personality development (Caspi, Roberts, & Shiner, 2005). The basic idea is that attributes associated with positive adaptation and attributes associated with the successful fulfillment of adult roles tend to increase during adulthood in terms of their average levels.

, 2006). Openness also declines with age, especially after mid-life (Roberts et al., 2006). These changes are often viewed as positive trends given that higher levels of agreeableness and conscientiousness and lower levels of neuroticism are associated with seemingly desirable outcomes such as increased relationship stability and quality, greater success at work, better health, a reduced risk of criminality and mental health problems, and even decreased mortality (e.g., Kotov, Gamez, Schmidt, & Watson, 2010; Miller & Lynam 2001; Ozer & Benet-Martínez, 2006; Roberts, Kuncel, Shiner, Caspi, & Goldberg, 2007). This pattern of positive average changes in personality attributes is known as the maturity principle of adult personality development (Caspi, Roberts, & Shiner, 2005). The basic idea is that attributes associated with positive adaptation and attributes associated with the successful fulfillment of adult roles tend to increase during adulthood in terms of their average levels.

Roberts et al. (2006) found that young adulthood (the period between the ages of 18 and the late 20s) was the most active time in the lifespan for observing average changes, although average differences in personality attributes were observed across the lifespan. Such a result might be surprising in light of the intuition that adolescence is a time of personality change and maturation. However, young adulthood is typically a time in the lifespan that includes a number of life changes in terms of finishing school, starting a career, committing to romantic partnerships, and parenthood (Donnellan, Conger, & Burzette, 2007; Rindfuss, 1991). Finding that young adulthood is an active time for personality development provides circumstantial evidence that adult roles might generate pressures for certain patterns of personality development. Indeed, this is one potential explanation for the maturity principle of personality development.This pattern of increasing stability with age is called the cumulative continuity principle of personality development (Caspi et al. , 2005). This general pattern holds for both women and men and applies to a wide range of different personality attributes ranging from extraversion to openness and curiosity. It is important to emphasize, however, that the observed correlations are never perfect at any age (i.e., the correlations do not reach 1.0). This indicates that personality changes can occur at any time in the lifespan; it just seems that greater inconsistency is observed in childhood and adolescence than in adulthood.

, 2005). This general pattern holds for both women and men and applies to a wide range of different personality attributes ranging from extraversion to openness and curiosity. It is important to emphasize, however, that the observed correlations are never perfect at any age (i.e., the correlations do not reach 1.0). This indicates that personality changes can occur at any time in the lifespan; it just seems that greater inconsistency is observed in childhood and adolescence than in adulthood.

This perspective implies near perfect stability of personality in adulthood. In contrast, other psychologists have sometimes denied there was any stability to personality at all. Their perspective is that individual thoughts and feelings are simply responses to transitory situational influences that are unlikely to show much consistency across the lifespan. Current research does not support either of these extreme perspectives. Nonetheless, the existence of some degree of stability raises important questions about the exact processes and mechanisms that produce personality stability (and personality change).

This perspective implies near perfect stability of personality in adulthood. In contrast, other psychologists have sometimes denied there was any stability to personality at all. Their perspective is that individual thoughts and feelings are simply responses to transitory situational influences that are unlikely to show much consistency across the lifespan. Current research does not support either of these extreme perspectives. Nonetheless, the existence of some degree of stability raises important questions about the exact processes and mechanisms that produce personality stability (and personality change). It’s quite easy to imagine, “Once I’m 30, married, and with a family, I will be that person for the rest of my life.” But the research shows that while some traits are stable, others continue to develop and adjust to our new environments. [Image: CC0 Public Domain, https://goo.gl/m25gce]

Personality stability is the result of the interplay between the individual and her/his environment. Psychologists use the term person–environment transactions (e.g., Roberts et al., 2008) to capture the mutually transforming interplay between individuals and their contextual circumstances. Several different types of these transactions have been described by psychological researchers. Active person–environment transactions occur when individuals seek out certain kinds of environments and experiences that are consistent with their personality characteristics. Risk-taking individuals may spend their leisure time very differently than more cautious individuals. Some prefer extreme sports whereas others prefer less intense experiences. Reactive person–environment transactions occur when individuals react differently to the same objective situation because of their personalities. A large social gathering represents a psychologically different context to the highly extraverted person compared with the highly introverted person. Evocative person–environment transactions occur whenever individuals draw out or evoke certain kinds of responses from their social environments because of their personality attributes.

Psychologists use the term person–environment transactions (e.g., Roberts et al., 2008) to capture the mutually transforming interplay between individuals and their contextual circumstances. Several different types of these transactions have been described by psychological researchers. Active person–environment transactions occur when individuals seek out certain kinds of environments and experiences that are consistent with their personality characteristics. Risk-taking individuals may spend their leisure time very differently than more cautious individuals. Some prefer extreme sports whereas others prefer less intense experiences. Reactive person–environment transactions occur when individuals react differently to the same objective situation because of their personalities. A large social gathering represents a psychologically different context to the highly extraverted person compared with the highly introverted person. Evocative person–environment transactions occur whenever individuals draw out or evoke certain kinds of responses from their social environments because of their personality attributes. A warm and secure individual invites different kinds of responses from peers than a cold and aloof individual.

A warm and secure individual invites different kinds of responses from peers than a cold and aloof individual.

Current researchers make distinctions between the mechanisms likely to produce personality stability and the mechanisms likely to produce changes (Roberts, 2006; Roberts et al., 2008). Brent Roberts coined the helpful acronym ASTMA to aid in remembering many of these mechanisms: Attraction (A), selection (S), manipulation (M), and attrition (A) tend to produce personality stability, whereas transformation (T) explains personality change.

Think to your own preference for hobbies and jobs. How do these activities reflect core attributes of your own personality? [Image: Dave Scriven, https://goo.gl/4g9tCz, CC BY-NC 2.0, https://goo.gl/VnKlK8]Individuals sometimes select careers, friends, social clubs, and lifestyles because of their personality attributes. This is the active process of attraction—individuals are attracted to environments because of their personality attributes. Situations that match with our personalities seem to feel “right” (e.g., Cesario, Grant, & Higgins, 2004). On the flipside of this process, gatekeepers, such as employers, admissions officers, and even potential relationship partners, often select individuals because of their personalities. Extraverted and outgoing individuals are likely to make better salespeople than quiet individuals who are uncomfortable with social interactions. All in all, certain individuals are “admitted” by gatekeepers into particular kinds of environments because of their personalities. Likewise, individuals with characteristics that are a bad fit with a particular environment may leave such settings or be asked to leave by gatekeepers. A lazy employee will not last long at a demanding job. These examples capture the process of attrition( dropping out). The processes of selection and attrition reflect evocative person–environment transactions. Last, individuals can actively manipulate their environments to match their personalities.

Situations that match with our personalities seem to feel “right” (e.g., Cesario, Grant, & Higgins, 2004). On the flipside of this process, gatekeepers, such as employers, admissions officers, and even potential relationship partners, often select individuals because of their personalities. Extraverted and outgoing individuals are likely to make better salespeople than quiet individuals who are uncomfortable with social interactions. All in all, certain individuals are “admitted” by gatekeepers into particular kinds of environments because of their personalities. Likewise, individuals with characteristics that are a bad fit with a particular environment may leave such settings or be asked to leave by gatekeepers. A lazy employee will not last long at a demanding job. These examples capture the process of attrition( dropping out). The processes of selection and attrition reflect evocative person–environment transactions. Last, individuals can actively manipulate their environments to match their personalities. An outgoing person will find ways to introduce more social interactions into the workday, whereas a shy individual may shun the proverbial water cooler to avoid having contact with others.

An outgoing person will find ways to introduce more social interactions into the workday, whereas a shy individual may shun the proverbial water cooler to avoid having contact with others.

These four processes of attraction, selection, attrition, and manipulation explain how a kind of matching occurs between personality attributes and environmental conditions for many individuals. This positive matching typically produces personality consistency because the “press” of the situation reinforces the attributes of the person. This observation is at the core of the corresponsive principle of personality development (Caspi et al., 2005; Roberts, Caspi, & Moffitt, 2003). Preexisting personality attributes and environmental contexts work in concert to promote personality continuity. The idea is that environments often reinforce those personality attributes that were partially responsible for the initial environmental conditions in the first place. For example, ambitious and confident individuals might be attracted to and selected for more demanding jobs (Roberts et al. , 2003). These kinds of jobs often require drive, dedication, and achievement striving thereby accentuating dispositional tendencies toward ambition and confidence.

, 2003). These kinds of jobs often require drive, dedication, and achievement striving thereby accentuating dispositional tendencies toward ambition and confidence.

Additional considerations related to person–environment transactions may help to further explain personality stability. Individuals gain more autonomy to select their own environment as they transition from childhood to adulthood (Scarr & McCartney, 1983). This might help explain why the differential stability of personality attributes increases from adolescence into adulthood. Reactive and evocative person–environment transactions also facilitate personality stability. The overarching idea is that personality attributes shape how individuals respond to situations and shape the kinds of responses individuals elicit from their environments. These responses and reactions can generate self-fulfilling cycles. For example, aggressive individuals seem to interpret ambiguous social cues as threatening (something called a hostile attribution bias or a hostile attribution of intent; see Crick & Dodge, 1996; Orobio de Castro, Veerman, Koops, Bosch, & Monshouwer, 2002). If a stranger runs into you and you spill your hot coffee all over a clean shirt, how do you interpret the situation? Do you believe the other person was being aggressive, or were you just unlucky? A rude, caustic, or violent response might invite a similar response from the individual who ran into you. The basic point is that personality attributes help shape reactions to and responses from the social world, and these processes often (but not always) end up reinforcing dispositional tendencies.

If a stranger runs into you and you spill your hot coffee all over a clean shirt, how do you interpret the situation? Do you believe the other person was being aggressive, or were you just unlucky? A rude, caustic, or violent response might invite a similar response from the individual who ran into you. The basic point is that personality attributes help shape reactions to and responses from the social world, and these processes often (but not always) end up reinforcing dispositional tendencies.

Although a number of mechanisms account for personality continuity by generating a match between the individual’s characteristics and the environment, personality change or transformation is nonetheless possible. Recall that differential stability is not perfect. The simplest mechanism for producing change is a cornerstone of behaviorism: Patterns of behavior that produce positive consequences (pleasure) are repeated, whereas patterns of behavior that produce negative consequences (pain) will diminish (Thorndike, 1933). Social settings may have the power to transform personality if the individual is exposed to different rewards and punishments and the setting places limitations on how a person can reasonably behave (Caspi & Moffitt, 1993). For example, environmental contexts that limit agency and have very clear reward structures such as the military might be particularly powerful contexts for producing lasting personality changes (e.g., Jackson, Thoemmes, Jonkmann, Lüdke, & Trautwein, 2012).

Social settings may have the power to transform personality if the individual is exposed to different rewards and punishments and the setting places limitations on how a person can reasonably behave (Caspi & Moffitt, 1993). For example, environmental contexts that limit agency and have very clear reward structures such as the military might be particularly powerful contexts for producing lasting personality changes (e.g., Jackson, Thoemmes, Jonkmann, Lüdke, & Trautwein, 2012).

It is also possible that individuals might change their personality attributes by actively striving to change their behaviors and emotional reactions with help from outsiders. This idea lies at the heart of psychotherapy. As it stands, the conditions that produce lasting personality changes are an active area of research. Personality researchers have historically sought to demonstrate the existence of personality stability, and they are now turning their full attention to the conditions that facilitate personality change. There are currently a few examples of interventions that end up producing short-term personality changes (Jackson, Hill, Payne, Roberts, & Stine-Morrow, 2012), and this is an exciting area for future research (Edmonds, Jackson, Fayard, & Roberts, 2008). Insights about personality change are important for creating effective interventions designed to foster positive human development. Finding ways to promote self-control, emotional stability, creativity, and an agreeable disposition would likely lead to improvements for both individuals and society as a whole because these attributes predict a range of consequential life outcomes (Ozer & Benet-Martínez, 2006; Roberts et al., 2007)

There are currently a few examples of interventions that end up producing short-term personality changes (Jackson, Hill, Payne, Roberts, & Stine-Morrow, 2012), and this is an exciting area for future research (Edmonds, Jackson, Fayard, & Roberts, 2008). Insights about personality change are important for creating effective interventions designed to foster positive human development. Finding ways to promote self-control, emotional stability, creativity, and an agreeable disposition would likely lead to improvements for both individuals and society as a whole because these attributes predict a range of consequential life outcomes (Ozer & Benet-Martínez, 2006; Roberts et al., 2007)

There are multiple ways to evaluate personality stability. The existing evidence suggests that personality attributes are relatively enduring attributes that show predictable average-level changes across the lifespan. Personality stability is produced by a complicated interplay between individuals and their social settings. Many personality attributes are linked to life experiences in a mutually reinforcing cycle: Personality attributes seem to shape environmental contexts, and those contexts often then accentuate and reinforce those very personality attributes. Even so, personality change or transformation is possible because individuals respond to their environments. Individuals may also want to change their personalities. Personality researchers are now beginning to address important questions about the possibility of lasting personality changes through intervention efforts.

The existing evidence suggests that personality attributes are relatively enduring attributes that show predictable average-level changes across the lifespan. Personality stability is produced by a complicated interplay between individuals and their social settings. Many personality attributes are linked to life experiences in a mutually reinforcing cycle: Personality attributes seem to shape environmental contexts, and those contexts often then accentuate and reinforce those very personality attributes. Even so, personality change or transformation is possible because individuals respond to their environments. Individuals may also want to change their personalities. Personality researchers are now beginning to address important questions about the possibility of lasting personality changes through intervention efforts.

Videos: Brian Little PhD on “Who are you Really” Brian Little is a long-term personality researcher and author.

Vocabulary

- Active person–environment transactions

- The interplay between individuals and their contextual circumstances that occurs whenever individuals play a key role in seeking out, selecting, or otherwise manipulating aspects of their environment.

- Corresponsive principle

- The idea that personality traits often become matched with environmental conditions such that an individual’s social context acts to accentuate and reinforce their personality attributes.

- Cumulative continuity principle

- The generalization that personality attributes show increasing stability with age and experience.

Heterotypic Stability: effects of fundamental temperamental tendencies change with age, but temperament and personality stay the same. In other words, behaviors associated with traits manifest differently, but the trait stays similar in each of us.

In other words, behaviors associated with traits manifest differently, but the trait stays similar in each of us.

- Maturity principle

- The generalization that personality attributes associated with the successful fulfillment of adult roles increase with age and experience.

Practice Quiz

References

- Anusic, I., Lucas, R. E., & Donnellan, M. B. (2012). Cross-sectional age differences in personality: Evidence from nationally representative samples from Switzerland and the United States. Journal of Research in Personality, 46, 116–120.

- Caspi, A., & Bem, D. J. (1990). Personality continuity and change across the life course. In L. Pervin (Ed.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 549–575). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T. E. (1993). When do individual differences matter? A paradoxical theory of personality coherence.

Psychological Inquiry, 4, 247–271.

Psychological Inquiry, 4, 247–271. - Caspi, A., Bem, D. J., & Elder, G. H., Jr. (1989). Continuities and consequences of interactional styles across the life course. Journal of Personality, 57, 375–406.

- Caspi, A., Roberts, B. W., & Shiner, R. L. (2005). Personality development: Stability and change. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 453–484.

- Cesario, J., Grant, H., & Higgins, E. T. (2004). Regulatory fit and persuasion: Transfer from “feeling right.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 388–404.

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Crick, N. R., & Dodge, K. A. (1996). Social information-processing mechanisms in reactive and proactive aggression. Child Development, 67, 993–1002.

- Donnellan, M.

B., Conger, R. D., & Burzette, R. G. (2007). Personality development from late adolescence to young adulthood: Differential stability, normative maturity, and evidence for the maturity-stability hypothesis. Journal of Personality, 75, 237–267.

B., Conger, R. D., & Burzette, R. G. (2007). Personality development from late adolescence to young adulthood: Differential stability, normative maturity, and evidence for the maturity-stability hypothesis. Journal of Personality, 75, 237–267. - Edmonds, G. W., Jackson, J. J., Fayard, J. V., & Roberts, B. W. (2008). Is characters fate, or is there hope to change my personality yet? Social and Personality Compass, 2, 399–413.

- Ferguson, C. J. (2010). A meta-analysis of normal and disordered personality across the lifespan. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98, 659–667.

- Jackson, J. J., Hill, P. L., Payne, B. R., Roberts, B. W., & Stine-Morrow, E. A. L. (2012). Can an old dog learn (and want to experience) new tricks? Cognitive training increases openness to experience in older adults. Psychology and Aging, 27, 286-292.

- Jackson, J.

J., Thoemmes, F., Jonkmann, K., Lüdtke, O., & Trautwein, U. (2012). Military training and personality trait development: Does the military make the man, or does the man make the military? Psychological Science, 23, 270–277.

J., Thoemmes, F., Jonkmann, K., Lüdtke, O., & Trautwein, U. (2012). Military training and personality trait development: Does the military make the man, or does the man make the military? Psychological Science, 23, 270–277. - John, O. P., Naumann, L. P., & Soto, C. J. (2008). Paradigm shift to the integrative Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and conceptual issues. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, and L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and Research (3rd ed., pp. 114–158). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Kotov, R., Gamez, W., Schmidt, F., & Watson, D. (2010). Linking “big” personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 136, 768–821.

- Lucas, R. E., & Donnellan, M. B. (2011). Personality development across the lifespan: Longitudinal analyses with a national sample from Germany.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 847–861.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 847–861. - Lucas, R. E., & Donnellan, M. B. (2009). Age differences in personality: Evidence from a nationally representative sample of Australians. Developmental Psychology, 45, 1353–1363.

- McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (2003). Personality in adulthood: A five-factor theory perspective (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Miller, J. D., & Lynam, D. (2001). Structural models of personality and their relation to antisocial behavior: A meta-analytic review. Criminology, 39, 765–798.

- Mroczek, D. K., & Spiro, A., III (2007). Personality change influences mortality in older men. Psychological Science, 18, 371–376.

- Orobio de Castro, B., Veerman, J. W., Koops, W., Bosch, J. D., & Monshouwer, H. J. (2002). Hostile attribution of intent and aggressive behavior: A meta-analysis.

Child Development, 73, 916–934.

Child Development, 73, 916–934. - Ozer, D. J., & Benet-Martínez, V. (2006). Personality and the prediction of consequential outcomes. Annual Review of Psychology, 57, 401–421.

- Rindfuss, R. R. (1991). The young adult years: Diversity, structural change, and fertility. Demography, 28, 493–512.

- Roberts, B. W. (2006). Personality development and organizational behavior. Research in Organizational Behavior, 27, 1–40.

- Roberts, B. W., & DelVecchio, W. F. (2000). The rank-order consistency of personality traits from childhood to old age: A quantitative review of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 3–25.

- Roberts, B. W., & Mroczek, D. (2008). Personality trait change in adulthood. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17, 31–35.

- Roberts, B.

W., Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T. (2003). Work experiences and personality development in young adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 582–593.

W., Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T. (2003). Work experiences and personality development in young adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 582–593. - Roberts, B. W., Kuncel, N., Shiner, R. N., Caspi, A., & Goldberg, L. (2007). The power of personality: The comparative validity of personality traits, socioeconomic status, and cognitive ability for predicting important life outcomes. Perspectives in Psychological Science, 2, 313–345.

- Roberts, B. W., Kuncel, N., Shiner, R. N., Caspi, A., & Goldberg, L. (2007). The power of personality: The comparative validity of personality traits, socioeconomic status, and cognitive ability for predicting important life outcomes. Perspectives in Psychological Science, 2, 313–345.

- Roberts, B. W., Walton, K., & Viechtbauer, W. (2006). Patterns of mean-level change in personality traits across the life course: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies.

Psychological Bulletin, 132, 1–25.

Psychological Bulletin, 132, 1–25. - Roberts, B. W., Wood, D., & Caspi, A. (2008). Personality Development. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 375–398). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Scarr, S., & McCartney, K. (1983). How people make their own environments: A theory of genotype → environment effects. Child Development, 54, 424–435.

- Soto, C. J., John, O. P., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2011). Age differences in personality traits from 10 to 65: Big Five domains and facets in a large cross-sectional sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100, 330–348.

- Specht, J., Egloff, B., & Schmukle, S. C. (2011). Stability and change of personality across the life course: The impact of age and major life events on mean-level and rank-order stability of the Big Five.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 862–882.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 862–882. - Srivastava, S., John, O. P., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2003). Development of personality in early and middle adulthood: Set like plaster or persistent change? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 1041–1053.

- Terracciano, A., McCrae, R. R., Brant, L. J., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (2005). Hierarchical linear modeling analyses of the NEO-PI-R scales in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Psychology and Aging, 20, 493–506.

- Thorndike, E. L. (1933). A proof of the law of effect. Science, 77, 173–175.

- Vaidya, J. G., Gray, E. K., Haig, J. R., Mroczek, D. K., & Watson (2008). Differential stability and individual growth trajectories of Big Five and affective traits during young adulthood. Journal of Personality, 76, 267–304.

- Wortman, J.

, Lucas, R. E., & Donnellan, M. B. (in press). Stability and change in the Big Five personality domains: Evidence from a longitudinal study of Australians. Psychology and Aging.

, Lucas, R. E., & Donnellan, M. B. (in press). Stability and change in the Big Five personality domains: Evidence from a longitudinal study of Australians. Psychology and Aging.

This chapter is an edited version that is adapted from the NOBA Project as found here:

Donnellan, M. B. (2019). Personality stability and change. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF publishers. Retrieved from http://noba.to/sjvtxbwd

Grateful appreciation to the authors for making this an open use chapter. The original authors bear no responsibility for this edited and adapted version.

Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike

Personality traits - Psychologos

Personality traits (personality traits, personality traits) - traits and characteristics of a person that describe his internal (more precisely, deep) features. What you need to know about the peculiarities of his behavior, communication and response to certain situations is not specifically now, but during long-term contacts with a person.

Personal traits include deep features that have both a biological and social nature and determine more superficial, situational manifestations.

Conscientiousness, as a personality trait, in a particular situation will manifest itself as a willingness to see things through to the end.

Positive personality traits are often referred to as personality traits.

What personality traits can be classified as personality traits? It is easier to note that it does not apply to personality traits. Characteristics that describe the following are not personality traits:

- Subjective attitude to personality (Unusual, Surprising, Unpleasant).

- Physical qualities of a person (dexterous, beautiful).

- Social characteristics and "titles" (Experienced, Wise, Leading worker, Saint, Enlightened).

- A temporary, unstable state of a person, such as situational (Tired) or mood-dependent (Dejected or Radiating happiness). Unlike a position that can be quickly chosen, a personality trait does not change quickly.

A personality trait is an unchanging circumstance that can only be reckoned with, used or overcome. Something like the weather outside the window: we cannot change it, but if it rains there, we can take an umbrella and go where we need to go.

A personality trait is an unchanging circumstance that can only be reckoned with, used or overcome. Something like the weather outside the window: we cannot change it, but if it rains there, we can take an umbrella and go where we need to go.

Can you give a complete list of personality traits? - It is impossible to create a complete, “correct” list of personality traits: on the one hand, it is endless (limited only by the capabilities of the language and the imagination of its owner), on the other hand, this list is created for the specific needs of a particular study and therefore is always arbitrary.

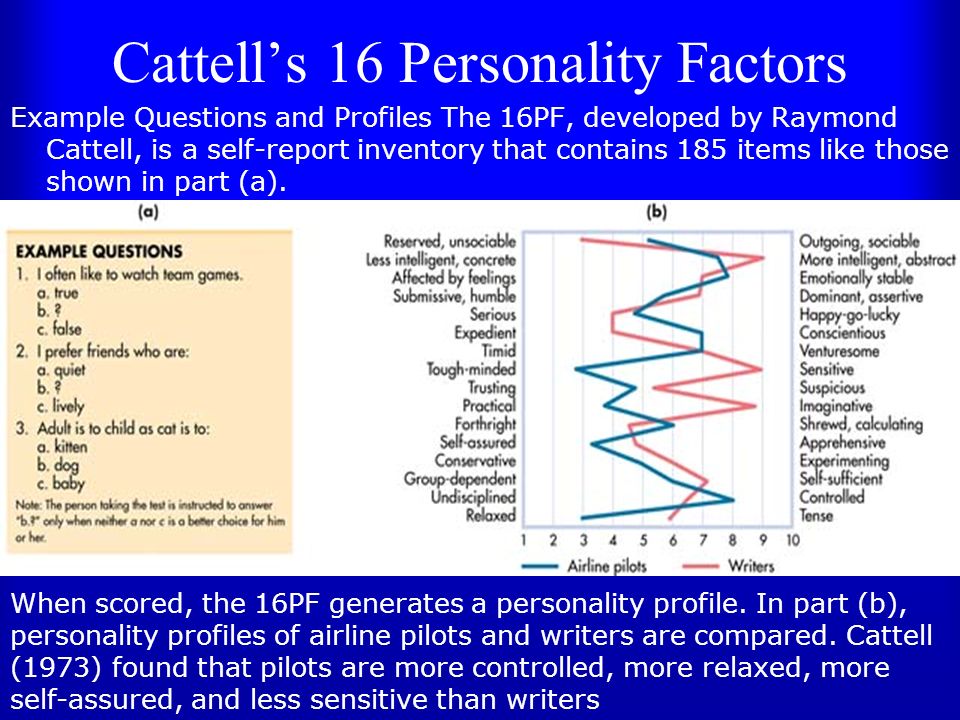

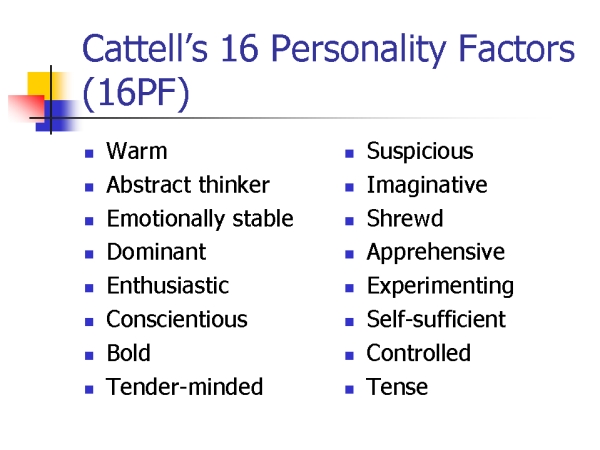

In an attempt to achieve a comprehensive description of personality, R. Cattell began by collecting all the names of personality traits found either in dictionaries such as compiled by G. Allport and H. Odbert, or in psychiatric and psychological literature. The resulting list of names (4500 characteristics) was reduced to 171 personality traits by combining explicit synonyms.

Further, it is not always possible to say whether some situational personality trait is her chosen position or a stable trait. A position is a choice, it is a certain way of thinking and attitude chosen by a person, then personality traits are stable personality traits. Unlike a position that can be quickly chosen, a personality trait does not change quickly.

If a person behaves like a Victim, is this his trait or a situational choice? To answer this question, you need to observe a person in different situations. Many of the personality traits can be simultaneously attributed to traits and positions, while noting the “predominance” of one or the other, characteristic of a particular culture of a given time. For example, the Consumer today is more often a position than a personality trait of an adult. Few people can definitely say that he has a stable characteristic of always taking care of himself and always only at his own expense. More often a person in a given situation quickly chooses this way of life, and in another situation he can make a different decision. However, we can also say that some people adhere to the position of the Consumer, having made a conscious choice and made it their stable habit. And in this sense - a personality trait.

However, we can also say that some people adhere to the position of the Consumer, having made a conscious choice and made it their stable habit. And in this sense - a personality trait.

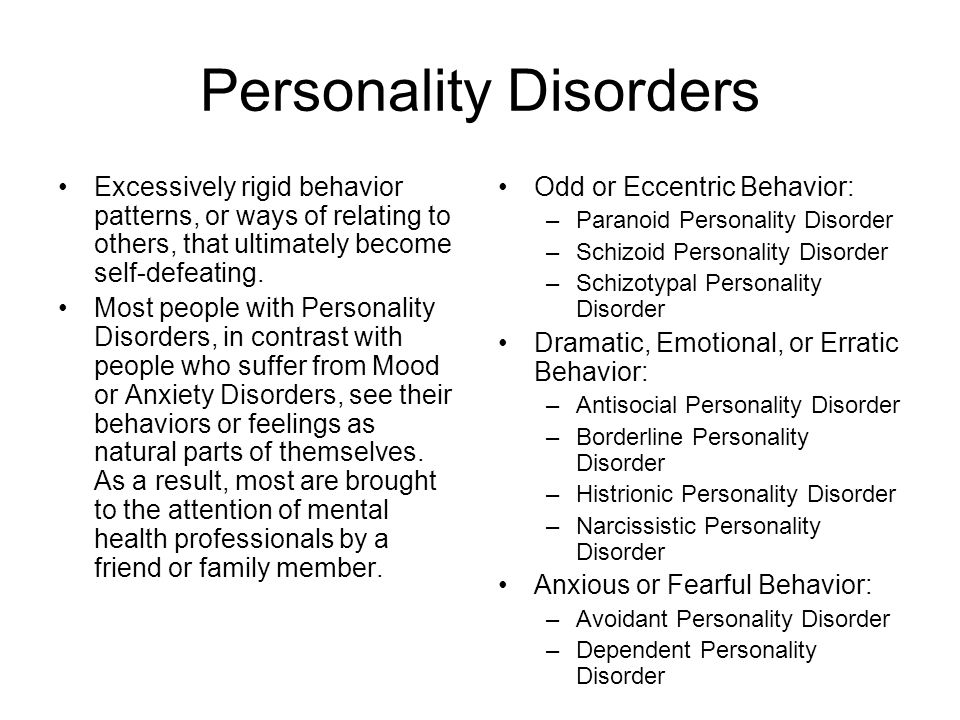

The most common list of personality traits used in classical psychological tests: MMPI, Cattell's test and others. According to Kettel, these are, first of all: "isolation - sociability", intelligence, "emotional instability - emotional stability", "subordination - dominance", "restraint - expressiveness", "low normative behavior - high normative behavior", "timidity - courage ”, “rigidity - sensitivity”, “gullibility - suspicion”, “practicality - daydreaming”, “straightforwardness - diplomacy”, “calmness - anxiety”, “conservatism - radicalism”, “conformism - nonconformism”, “low self-control - high self-control ”, “relaxation - tension”, “adequate self-esteem - inadequate self-esteem” (primary factors of the test), as well as “anxiety”, “extroversion - introversion”, “sensitivity” and “conformity” (secondary factors of the test).

It seems that the list of personality traits that are relevant in life is easy to continue: these are adequacy, suggestibility, good breeding, sincerity, perfectionism, restraint, and many others.

It is difficult to make a coherent system of personality traits, primarily due to the fact that personality traits are related to each other not only linearly, but also hierarchically. For example, behavioral habits such as Nods, Hoots, and Eye Flashes are part of listening skills, which are higher-level skills and habits. In turn, the signs of listening, together with adjustments in the body, adjustments in the dictionary, are components of the ability to listen. In turn, the ability to listen together, the ability to speak in clear theses, the skill of operating with facts and specifics, and the habit of summing up are components of thoughtful communication, which in turn is part of effective communication. Effective communication is an element of effective leadership, and so on.

From the point of view of the needs of practice, the list of personality traits can be significantly narrowed by highlighting the root, fundamental, proper personality traits. These are considered to be extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism and openness to experience (the so-called Big Five).

Openness to experience - the ability and readiness of a person to see (listen, perceive) what is happening in him, in the people around him and in life.

Openness to experience ensures personal growth and development.

Personal inadequacy is an obstacle to openness to experience: there is openness, but information comes to a person in a distorted form.

Closedness from experience, internal and external protections give greater security, but stop the growth and development of the personality. The extreme variant of defenses is impenetrability for experience.

Some of the features that are characteristic of a developed personality and less common in a mass personality, we have placed in the Self-Improvement section. We attributed positive, constructive, responsibility, energy, purposefulness, love of order, willingness to cooperate, as well as the ability and habit of living with love to such traits - unfortunately, these traits are clearly lacking, at least for Russian people, both in workers and relatives. relationships.

We attributed positive, constructive, responsibility, energy, purposefulness, love of order, willingness to cooperate, as well as the ability and habit of living with love to such traits - unfortunately, these traits are clearly lacking, at least for Russian people, both in workers and relatives. relationships.

Can a person change his personality traits? Someone definitely can. Most - no, they themselves are not capable. For more details, see the article "Is it possible to change your character, and how?"

PSYCHOLOGICAL STABILITY AS FACTOR OF INFLUENCE ON PEDAGOGICAL STABILITY DEVELOPMENT OF FUTURE MUSIC TEACHER

PSYCHOLOGICAL STABILITY AS A FACTOR OF INFLUENCE ON DEVELOPMENT OF PEDAGOGICAL STABILITY OF A FUTURE MUSIC TEACHER

Scientific article

Khruleva A. M.*

ORCID:0000-0001-9200-425X,

Krasnodar State Institute of Culture, Russia, Krasnodar

* Corresponding author (belchanka[at]inbox. ru)

ru)

Today, the pedagogical stability of future music teachers remains in the periphery of scientists' attention. One of the most important factors influencing the development of pedagogical stability of a future music teacher is psychological stability. In this article, psychological stability is considered as the most important element for the successful course of the educational process. Based on the work of researchers on psychological and pedagogical stability, a definition of the concept of "pedagogical stability" is introduced. Key words: stability-destabilization, stagnation, destruction, pedagogical process. PSYCHOLOGICAL STABILITY AS FACTOR OF INFLUENCE ON PEDAGOGICAL STABILITY DEVELOPMENT OF FUTURE MUSIC TEACHER Research article Khruleva A. M.* ORCID: 0000-0001-9200-425X, Krasnodar State Institute of Culture, Russia , Krasnodar * Corresponding author (belchanka[at]inbox. Abstract The pedagogical stability of future music teachers remains almost unnoticed by scientists today. One of the most important factors influencing the development of pedagogical stability of a future music teacher is psychological stability. Psychological stability is considered as the most important element for the successful course of the educational process in this paper. Based on the work of researchers on psychological and pedagogical stability, the author gives the definition of the “pedagogical stability” concept. Keywords: stability-destabilization, stagnation, destruction, pedagogical process. The theme of the formation of stability as a separate phenomenon has been relevant for many centuries. The concept of stability can be characterized as "... the ability of a certain system to function without changing its own structure, while maintaining balance" [4]. Sociologist and representative of the positivist paradigm, which has found its application in the field of social philosophy - G. It should be said that stability is included in the range of personal characteristics of the individual. Stability, as a separate personality trait, can be seen as the ability to maintain personal orientations and attitudes despite the presence of external stimuli. I would like to note that the stability of psycho-emotional reactions in relation to external stimuli is not an innate quality. The presence of stable reactions in an individual increases in the process of social development, as well as in the course of acquiring cognitive skills and subsequently at the stage of professional interaction and improvement. Turning to the understanding of psychological stability, it should be noted that it is of key importance in the development of pedagogical stability. At the turn of the XX-XXI centuries, the problem of psychological stability began to be actively discussed in the psychological and pedagogical literature (L.I. Bozhovich, P.B. Zilberman, L.V. Mitina, E.P. Krupnik, A.N. Leontiev, B. F. Lomov, L.V. Mitina, A.A. Perevalova, E.N. Lebedeva, etc.), as well as the problem of crises of professional stability (stability) of specialists, including educators (A.G. Asmolov , F.E. Vasilyuk, E.P. Ermolaeva, E.F. Zeer, L.M. Mitina, N.A. Podymov, E.E. Symanyuk, L.B. Schneider, etc.). E.P. Krupnik, E.N. Lebedev consider psychological stability as "... a mobile equilibrium state of the psyche, maintained by counteracting external and internal factors that violate this balance" [6]. V.E. Chudnovsky in his works considers psychological stability as a moral category. He defines it as the ability of the individual, helping to lead to the realization of the personal positions of the individual. T.V. Kononenko [5] touches upon the problems of educating psychological stability. The researcher argues that psychological stability is the moral consciousness of the individual, its ability to self-organize in the process of pedagogical activity, behavior in everyday life. Psychological stability is not only the ability to resist negative scenarios, but also the ability to transform and change external circumstances for the better, to live in harmony with oneself and the outside world. According to the author, a person with internal self-control is able to direct his thoughts towards creation, based on positive professional and universal values. Speaking about the psychological stability of pedagogical workers R.I. Khmelyuk and N.A. Shevchenko consider it as a kind of synthesis of various qualities and personality traits, which allows the teacher to rationally use time, confidently and independently solve multi-level pedagogical tasks (in emotionally stressful conditions), and cope with difficulties in work [12]. Developed psychological stability helps in self-realization in the professional field, and also allows you to reveal the creative abilities of a person. Stability affects the professional development of specialists whose professional activities take place in the “man-man” system [4]. I would like to highlight the main characteristics of psychological stability, among which the main ones are: self-regulation and self-control. If we reflect these characteristics in more detail, then we can say that they include developed emotional balance, purposefulness, and discipline. Scientists interpret psychological stability as an integrative and complex quality, where they find a combination of various components of mental activity: emotional, moral, volitional. VA Ponomarenko [9] interprets psychological stability as a quality of personality, consisting of various components: Based on the content of the intellectual component (regulated transformations), we can conclude that psychological stability should in no case be perceived as a manifestation of rigidity in relation to mental reactions. Healthy psychological stability is not without dynamics. Because pedagogical activity is associated with enormous loads on the psyche, psychological stability is a key condition in the formation of pedagogical stability. Psychological stability helps to minimize the negative impact of various stress factors, helps to successfully cope with difficulties, it affects the development of pedagogical stability also because it is associated with the activity of the nervous system, and is also formed due to the capabilities of this system. Stability in pedagogical science is a set of qualities and properties of a teacher, which allows him to act independently, productively and rationally. It is also a phenomenon that allows to carry out the solution of a number of pedagogical problems for a long time with minimal effort. According to G.B. Zaremba, L.M. Mitina, pedagogical stability can be compared in some way with frustration tolerance - the ability of a teacher to endure life's problems and difficulties without harming their own mental health and psychological balance [7]. Under the influence of psychological stability, pedagogical stability acquires the features of a skill that allows the teacher to mobilize his internal intellectual, physical and psychological resources. Due to the influence of psychological stability, the teacher is able to solve professional problems strictly on time, and also (in the course of professional activity) not to lose his own pedagogical (cognitive) interest within the profession. The work of teachers of higher educational institutions should be built in the direction of developing the psychological stability of future music teachers, because this characteristic helps the teacher to build the pedagogical process in a positive way, based on the control of his own emotional state. In the presence of such personality traits as psychological and pedagogical stability, the teacher can control the dynamics of the pedagogical process, as well as the dynamics of the mood of its other participants (students). The relationship between psychological and pedagogical stability is great. These parts of the pedagogical process in their unity are aimed at the qualitative improvement of the educational process. The teacher needs to have the qualities of a strong and enduring personality, able to carry out the educational process in strict discipline, while maintaining the interest and enthusiasm of the students. Psychological stability as a factor in the formation of pedagogical stability in future music teachers is a multistructural and complex phenomenon. L.M. Mitina [8] claims psychological stability in the context of the science of pedagogy as a property that helps to resist the whole variety of difficulties that can cause progress in the emotional, psychological and purely professional (pedagogical) aspects. The most important thing that the skill of stability in working with children can help a teacher with is gaining the ability to adapt to the changes taking place in society. Analyzing the above, we came to the conclusion that pedagogical stability is a synthesis of the psychological qualities of a single individual, which allows solving professional problems for a long time with a minimum number of errors. The task of universities is to instill in future teachers the skills and abilities of endurance that can further develop in them stability and resistance to difficulties. The development of volitional qualities is impossible without the desire to become a professional in one's field, which is also acquired at the stage of training in an educational institution of a professional orientation. University teachers serve as a special example, which in one way or another influences the formation of the pedagogical and professional picture of the world among future music teachers. References References in English / References in English  ru)

ru)  Spencer defined stability as an equilibrium state of systems. In his opinion, such a state is achieved through adaptive processes to environmental conditions [11]. Based on the works of the researcher, the system may well be recognized as stable if in the course of its development it was subject to transformational processes and if over time it underwent coordination, differentiation, and also complication.

Spencer defined stability as an equilibrium state of systems. In his opinion, such a state is achieved through adaptive processes to environmental conditions [11]. Based on the works of the researcher, the system may well be recognized as stable if in the course of its development it was subject to transformational processes and if over time it underwent coordination, differentiation, and also complication.

V. E. Chudnovsky argues that psychological stability helps to preserve one’s own immunity in relation to external stimuli, which may also contradict the internal attitudes of the individual, her beliefs and views [13]. Here, psychological stability can be viewed as an ability that involves the inclusion of volitional efforts to implement personal positions.

V. E. Chudnovsky argues that psychological stability helps to preserve one’s own immunity in relation to external stimuli, which may also contradict the internal attitudes of the individual, her beliefs and views [13]. Here, psychological stability can be viewed as an ability that involves the inclusion of volitional efforts to implement personal positions.

Also, it can be noted that studies in the field of psychological stability allow us to conclude that the phenomenon of stability is fixed in a multifaceted connection with other branches of knowledge about the psyche, about consciousness and personality. The community of connections between psychological stability and other branches of knowledge can include: self-realization and the ability for it in a single individual, subjective growth, provided that personal conflicts are resolved in a timely manner. To create basic opportunities for the formation of psychological stability, an individual must have a balance of conformity and independence, as well as some ability to influence the current situation, while maintaining their own intentions and goals.

Also, it can be noted that studies in the field of psychological stability allow us to conclude that the phenomenon of stability is fixed in a multifaceted connection with other branches of knowledge about the psyche, about consciousness and personality. The community of connections between psychological stability and other branches of knowledge can include: self-realization and the ability for it in a single individual, subjective growth, provided that personal conflicts are resolved in a timely manner. To create basic opportunities for the formation of psychological stability, an individual must have a balance of conformity and independence, as well as some ability to influence the current situation, while maintaining their own intentions and goals.

The pedagogical stability of a teacher, as well as psychological stability, is not a natural property - it is the work of the individual on himself (development of motivation, control over emotions, etc.). As mentioned above, the key to the relationship between psychological and pedagogical stability is the general nature of these phenomena - the ability of the individual's psyche to endure the presence of stimuli, maintain internal emotional balance to solve various problems.

The pedagogical stability of a teacher, as well as psychological stability, is not a natural property - it is the work of the individual on himself (development of motivation, control over emotions, etc.). As mentioned above, the key to the relationship between psychological and pedagogical stability is the general nature of these phenomena - the ability of the individual's psyche to endure the presence of stimuli, maintain internal emotional balance to solve various problems. ![]()

According to a number of authors (F.N. Gonobolin, N.D. Nikandrov, E.V. Bondarevskaya), psychological stability is a significant quality in the professional sense, as it affects the emotional and psychological culture of the teacher. It should be said that as a phenomenon of an integrative nature, psychological stability is the guarantor of the teacher's professional success. Influencing pedagogical stability, which is characterized by self-education and self-discipline of the teacher, psychological stability effectively affects the communicative properties of the educational process, while maintaining the ability of the teacher to dialogue between him and the students.

According to a number of authors (F.N. Gonobolin, N.D. Nikandrov, E.V. Bondarevskaya), psychological stability is a significant quality in the professional sense, as it affects the emotional and psychological culture of the teacher. It should be said that as a phenomenon of an integrative nature, psychological stability is the guarantor of the teacher's professional success. Influencing pedagogical stability, which is characterized by self-education and self-discipline of the teacher, psychological stability effectively affects the communicative properties of the educational process, while maintaining the ability of the teacher to dialogue between him and the students.  O.A. Sirotin singled out certain parameters that can be included in the context of the concept of psychological stability, they affect the entire structure of education, these are physical, emotional and psychological endurance [10].

O.A. Sirotin singled out certain parameters that can be included in the context of the concept of psychological stability, they affect the entire structure of education, these are physical, emotional and psychological endurance [10].  It is the presence of "sthenicity" of emotions acquired in the learning process that will help music teachers to conduct the educational process based on high-quality interaction between the subjects of the pedagogical process and the final result.

It is the presence of "sthenicity" of emotions acquired in the learning process that will help music teachers to conduct the educational process based on high-quality interaction between the subjects of the pedagogical process and the final result.

Conflict of interest Not specified. Conflict of Interest None declared.

B. Darvish // Izvestiya AGU. - 2011. - No. 2-2(70). – P. 47 – 51.

B. Darvish // Izvestiya AGU. - 2011. - No. 2-2(70). – P. 47 – 51.  .. Candidate of Psychological Sciences: 19.00.00 / O.A. Sirotin. - Moscow, 1972. - 182 p.

.. Candidate of Psychological Sciences: 19.00.00 / O.A. Sirotin. - Moscow, 1972. - 182 p.

of psychol. Works] / Ed. by D.I. Feldstein; Rus. Acad. of Education, Moscow. psycho-social inst. - 3 rd - M.: MPSI; Voronezh: MODEK, 2001. - 349 p. [in English]

of psychol. Works] / Ed. by D.I. Feldstein; Rus. Acad. of Education, Moscow. psycho-social inst. - 3 rd - M.: MPSI; Voronezh: MODEK, 2001. - 349 p. [in English]  00.01 / T.V. Kononenko. – Maykop, 2004. – 171 p. [in English]

00.01 / T.V. Kononenko. – Maykop, 2004. – 171 p. [in English]