Can strattera be taken at night

Once-daily atomoxetine for treating pediatric attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: comparison of morning and evening dosing

Randomized Controlled Trial

. 2009 Sep;48(7):723-33.

doi: 10.1177/0009922809335321. Epub 2009 May 6.

Stan L Block 1 , Douglas Kelsey, Daniel Coury, Donald Lewis, Humberto Quintana, Virginia Sutton, Kory Schuh, Albert J Allen, Calvin Sumner

Affiliations

Affiliation

- 1 Kentucky Pediatric Research, Bardstown, Kentucky 40004, USA. [email protected]

- PMID: 19420182

- DOI: 10.

1177/0009922809335321

Randomized Controlled Trial

Stan L Block et al. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2009 Sep.

. 2009 Sep;48(7):723-33.

doi: 10.1177/0009922809335321. Epub 2009 May 6.

Authors

Stan L Block 1 , Douglas Kelsey, Daniel Coury, Donald Lewis, Humberto Quintana, Virginia Sutton, Kory Schuh, Albert J Allen, Calvin Sumner

Affiliation

- 1 Kentucky Pediatric Research, Bardstown, Kentucky 40004, USA. [email protected]

- PMID: 19420182

- DOI: 10.

1177/0009922809335321

1177/0009922809335321

Abstract

In this 3-arm, randomized, double-blind trial, once-daily morning-dosed atomoxetine, evening-dosed atomoxetine, and placebo were compared for treating pediatric attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Patients received morning atomoxetine/evening placebo (n = 102), morning placebo/evening atomoxetine (n = 93), or morning placebo/evening placebo (n = 93) for about 6 weeks. Core symptom efficacy was measured at weeks 0, 1, 3, and 6. Parent assessments of the child's home behaviors in the evening and early morning were collected daily during the first 2 weeks of treatment. Morning-dosed and evening-dosed atomoxetine significantly decreased core ADHD symptoms relative to placebo and produced symptom improvements that were measured up to 24 hours later. Morning dosing was superior to evening dosing on some efficacy measures. Evening dosing showed greater tolerability with significantly more patients receiving morning atomoxetine reporting at least 1 adverse event than those receiving evening atomoxetine.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00486122.

Similar articles

-

Once-daily atomoxetine treatment for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, including an assessment of evening and morning behavior: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial.

Kelsey DK, Sumner CR, Casat CD, Coury DL, Quintana H, Saylor KE, Sutton VK, Gonzales J, Malcolm SK, Schuh KJ, Allen AJ. Kelsey DK, et al. Pediatrics. 2004 Jul;114(1):e1-8. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.e1. Pediatrics. 2004. PMID: 15231966 Clinical Trial.

-

Once-daily atomoxetine for adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a 6-month, double-blind trial.

Adler LA, Spencer T, Brown TE, Holdnack J, Saylor K, Schuh K, Trzepacz PT, Williams DW, Kelsey D.

Adler LA, et al. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009 Feb;29(1):44-50. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318192e4a0. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009. PMID: 19142107 Clinical Trial.

Adler LA, et al. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009 Feb;29(1):44-50. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318192e4a0. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009. PMID: 19142107 Clinical Trial. -

Comparison of parent and teacher reports of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms from two placebo-controlled studies of atomoxetine in children.

Biederman J, Gao H, Rogers AK, Spencer TJ. Biederman J, et al. Biol Psychiatry. 2006 Nov 15;60(10):1106-10. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.036. Epub 2006 Jun 27. Biol Psychiatry. 2006. PMID: 16806096 Clinical Trial.

-

Atomoxetine: a new pharmacotherapeutic approach in the management of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Barton J. Barton J. Arch Dis Child. 2005 Feb;90 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):i26-9.

doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.059386. Arch Dis Child. 2005. PMID: 15665154 Free PMC article. Review.

doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.059386. Arch Dis Child. 2005. PMID: 15665154 Free PMC article. Review. -

Atomoxetine treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Eiland LS, Guest AL. Eiland LS, et al. Ann Pharmacother. 2004 Jan;38(1):86-90. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D144. Ann Pharmacother. 2004. PMID: 14742801 Review.

See all similar articles

Cited by

-

The Mechanism, Clinical Efficacy, Safety, and Dosage Regimen of Atomoxetine for ADHD Therapy in Children: A Narrative Review.

Fu D, Wu DD, Guo HL, Hu YH, Xia Y, Ji X, Fang WR, Li YM, Xu J, Chen F, Liu QQ. Fu D, et al. Front Psychiatry. 2022 Feb 9;12:780921. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.780921. eCollection 2021.

Front Psychiatry. 2022. PMID: 35222104 Free PMC article. Review.

Front Psychiatry. 2022. PMID: 35222104 Free PMC article. Review. -

Efficacy and Tolerability of Different Interventions in Children and Adolescents with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder.

Luan R, Mu Z, Yue F, He S. Luan R, et al. Front Psychiatry. 2017 Nov 13;8:229. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00229. eCollection 2017. Front Psychiatry. 2017. PMID: 29180967 Free PMC article.

-

Comparative efficacy and safety of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder pharmacotherapies, including guanfacine extended release: a mixed treatment comparison.

Joseph A, Ayyagari R, Xie M, Cai S, Xie J, Huss M, Sikirica V. Joseph A, et al. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017 Aug;26(8):875-897. doi: 10.1007/s00787-017-0962-6.

Epub 2017 Mar 3. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017. PMID: 28258319 Free PMC article. Review.

Epub 2017 Mar 3. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017. PMID: 28258319 Free PMC article. Review. -

An Evaluation on the Efficacy and Safety of Treatments for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents: a Comparison of Multiple Treatments.

Li Y, Gao J, He S, Zhang Y, Wang Q. Li Y, et al. Mol Neurobiol. 2017 Nov;54(9):6655-6669. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-0179-6. Epub 2016 Oct 13. Mol Neurobiol. 2017. PMID: 27738872

-

Sleep Problems in Children with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Current Status of Knowledge and Appropriate Management.

Tsai MH, Hsu JF, Huang YS. Tsai MH, et al. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016 Aug;18(8):76. doi: 10.1007/s11920-016-0711-4. Curr Psychiatry Rep.

2016. PMID: 27357497 Review.

2016. PMID: 27357497 Review.

See all "Cited by" articles

Publication types

MeSH terms

Substances

Surprising Health Benefits Of Taking Strattera At Night

Dizziness or sleepiness is one of the most common side effects of prescription and over-the-counter medicines. When medicines make you tired, it is often because they affect chemicals in your brain called neurotransmitters. Your nerves use them to carry messages to each other. Some of them control how awake or sleepy you feel.

Some medications work more effectively when taken at specific times. When getting a new prescription, the pharmacist is tasked with reviewing important information with you regarding medication management. Among the things he or she may cover is when to take medication. Just like certain prescriptions should be taken with food or with a full glass of water for best results, timing also matters when it comes to taking your daily medications.

Research has shown that in some cases, it may be important to take a drug at a particular time of day. This approach, known as chronotherapy, is gaining attention as research suggests a relationship between when we take medications and how well they work.

The best time to take medication may vary depending on the drug, but if your pharmacist says to take your dose at the same time each day, it’s best that you do so.

What is Strattera?

Strattera is a brand of atomoxetine, a prescription medication used to treat attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children, teenagers, and adults. It belongs to the group of medicines called selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). Drug treatment is the most effective treatment for ADHD as a neurodevelopmental disorder.

Strattera works in the brain to increase attention and decrease restlessness in people who are hyperactive, have problems with concentration, or are easily distracted. This medicine may be used as part of a treatment program that includes social, educational, and psychological treatment.

This medicine may be used as part of a treatment program that includes social, educational, and psychological treatment.

Strattera is available in 10 mg, 18 mg, 25 mg, 40 mg, 60 mg, 80 mg, and 100 mg capsules.

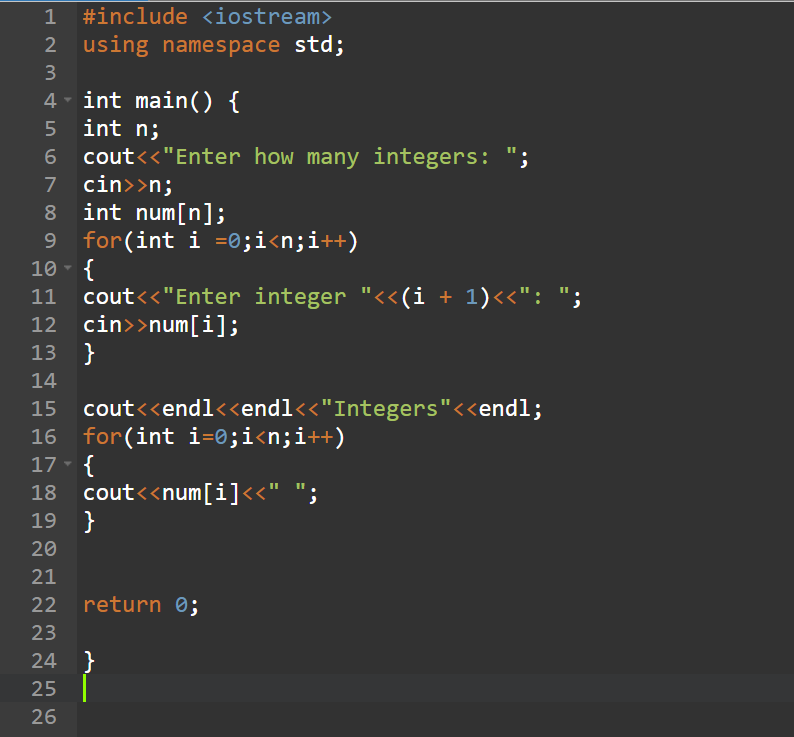

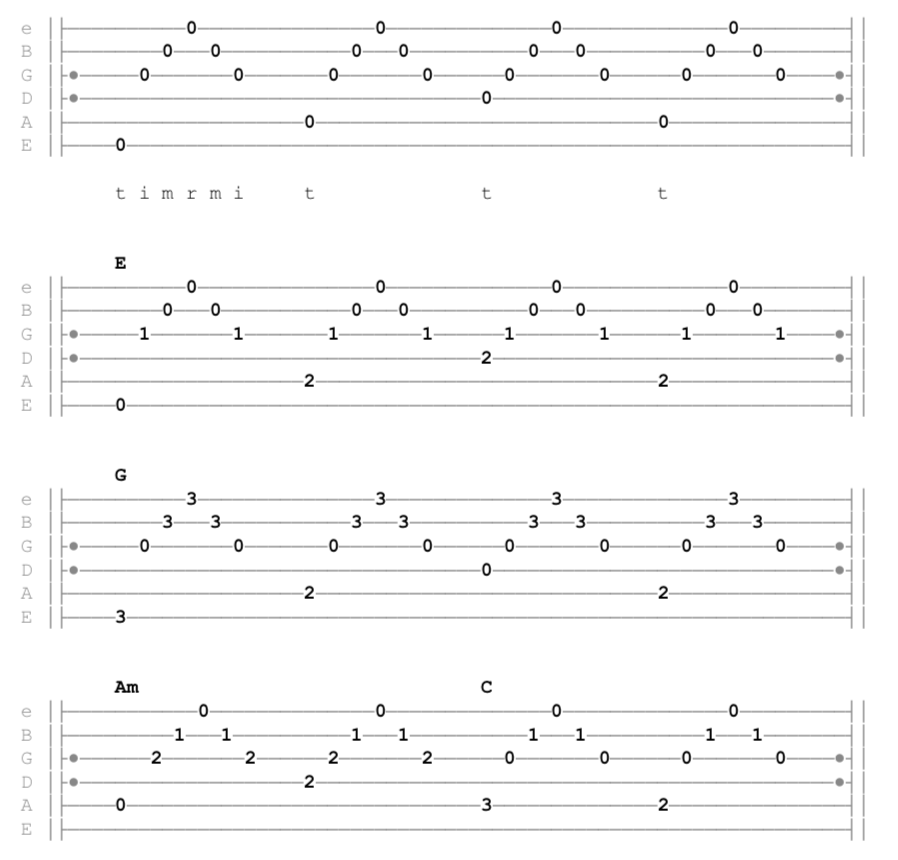

How should I take Strattera?

Strattera comes as a capsule to take by mouth. It is usually taken either once a day in the morning, or twice a day in the morning and late afternoon or early evening. Strattera may be taken with or without food. Take Strattera at around the same time(s) every day.

The typical dosing of Strattera is as follows:

Adults and children over 70 kg (154 lbs) in body weight: The typical starting dose is 40 mg by mouth per day. It can be given once in the morning or as divided doses in the morning and late afternoon/early evening. After 3 days, your provider will raise your dose to 80 mg per day. The dose can be adjusted up to a maximum daily dose of 100 mg.

Children 70 kg (154 lbs) or less in body weight: The total daily dose will depend on the child’s weight and can be given once in the morning or as divided doses in the morning and late afternoon/early evening. The typical starting dose is 0.5 mg/kg by mouth per day and then raised to 1.2 mg/kg per day after 3 days. The dose can be adjusted up to a maximum of 1.4 mg/kg per day (or 100 mg per day, whichever is less).

The typical starting dose is 0.5 mg/kg by mouth per day and then raised to 1.2 mg/kg per day after 3 days. The dose can be adjusted up to a maximum of 1.4 mg/kg per day (or 100 mg per day, whichever is less).

Children less than 6 years old: Atomoxetine (Strattera) is not recommended for this age group. Ask your child’s provider for an alternative medication for your child.

Follow the directions on your prescription label carefully, and ask your doctor or pharmacist to explain any part you do not understand. Take Strattera exactly as directed. Do not take more or less of it or take it more often than prescribed by your doctor.

Swallow Strattera capsules whole; do not open, chew, or crush them. If a capsule is accidentally broken or opened, wash away the loose powder with water right away. Try not to touch the powder and be especially careful not to get the powder in your eyes. If you do get powder in your eyes, rinse them with water right away and call your doctor.

Your doctor will probably start you on a low dose of Strattera and increase your dose after at least 3 days. Your doctor may increase your dose again after 2–4 weeks. You may notice an improvement in your symptoms during the first week of your treatment, but it may take up to one month for you to feel the full benefit of Strattera.

Strattera may help to control the symptoms of ADHD but will not cure the condition. Continue to take atomoxetine even if you feel well. Do not stop taking atomoxetine without talking to your doctor.

Health Benefits Of Taking Strattera At Night

The most common reason why patients don’t experience optimal benefits from taking Strattera is the high level of side effects, which prevents them from taking a dose that is enough to be therapeutic. There are several health benefits of taking Strattera at night they include:

Better Sleep Onset: Taking Strattera is associated with problems sleeping in some people. If you suffer from insomnia (a common sleep disorder that can make it hard to fall asleep). Taking Strattera at night is the best time to take it because it will help you sleep better and avoid excessive dizziness or sleepiness the medication can cause during the daytime.

If you suffer from insomnia (a common sleep disorder that can make it hard to fall asleep). Taking Strattera at night is the best time to take it because it will help you sleep better and avoid excessive dizziness or sleepiness the medication can cause during the daytime.

Avoid Urinary problems: A common side effect of Strattera is urinary hesitancy or retention (Difficulty starting or maintaining a urine stream). After a single oral dose, Strattera reaches maximum plasma concentration within about 1-2 hours of administration. In extensive metabolizers, atomoxetine has a plasma half-life of 5.2 hours, while in poor metabolizers; atomoxetine has a plasma half-life of 21.6 hours. Taking the medication at night can benefit people with nocturnal enuresis also known as nighttime incontinence or bedwetting.

Better Appetite: A common side effect of Strattera is lack of appetite. Decreased appetite can lead to the development of malnutrition or vitamin and electrolyte deficiencies, which can have life-threatening complications. An important health benefit of taking Strattera at night is the reduced impact on daytime eating. Good nutrition especially foods rich in protein such as lean beef, pork, poultry, fish, eggs, beans, nuts, soy, and low-fat dairy products can have beneficial effects on ADHD symptoms. Protein-rich foods are used by the body to make neurotransmitters, the chemicals released by brain cells to communicate with each other.

An important health benefit of taking Strattera at night is the reduced impact on daytime eating. Good nutrition especially foods rich in protein such as lean beef, pork, poultry, fish, eggs, beans, nuts, soy, and low-fat dairy products can have beneficial effects on ADHD symptoms. Protein-rich foods are used by the body to make neurotransmitters, the chemicals released by brain cells to communicate with each other.

Sexual life: Strattera appears to impair sexual function in some patients by triggering changes in sexual desire, sexual performance, and sexual satisfaction. Taking Strattera at night after sex will ensure that you are asleep when the full sexual side effect of the medication manifests.

What are the other side effects of Strattera?

Common side effects of Strattera include:

• Abdominal pain

• Constipation

• Cough

• Decreased appetite

• Depression

• Dizziness

• Drowsiness

• Dry mouth

• Erectile dysfunction

• Headache

• Hot flashes

• Increases in blood pressure (BP; 15-20 mm Hg or greater) and heart rate (HR; 20 beats/minute or greater)

• Indigestion/heartburn

• Irritability

• Itching

• Menstrual disorder/increased menstrual cramps

• Mood swings

• Nausea

• Sexual side effects (impotence, loss of interest in sex, or trouble having an orgasm)

• Sinus headache

• Skin rash (dermatitis)

• Trouble sleeping (insomnia)

• Upset stomach

• Urinary hesitation or retention

• Vomiting

• Weight loss

Serious side effects of Strattera include:

• Depression and depressed mood, anxiety

• Difficulty urinating

• Excess sweating

• Fainting

• Lethargy

• Male pelvic pain, urinary hesitation, or retention in children and adolescents

• Muscle wasting (rhabdomyolysis)

• Numbness or tingling

• QT prolongation, fainting

• Raynaud’s phenomenon

• Reduced sense of touch, numbness, and tingling in children and adolescents, sensory disturbances, tics

• Unusually fast or irregular heartbeat

Strattera may cause other side effects. Call your doctor if you have any unusual problems while taking this medication.

Call your doctor if you have any unusual problems while taking this medication.

If you experience a serious side effect, you or your doctor may send a report to the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) MedWatch Adverse Event Reporting program online (http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch) or by phone (1-800-332-1088).

Practical aspects of the use of donepezil in the treatment of elderly patients with dementia

Donepezil is the most commonly used cholinesterase inhibitor drug. It is registered in more than 100 countries around the world. With over 7 million prescriptions for donepezil in the United States in 2016, the drug ranked 98th in the ranking of most frequently prescribed drugs.

The development of the drug was started in 1983 by the Japanese pharmaceutical company Eisai. Since 1996, donepezil has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease (AD) (Pfizer's Aricept). From 1997 began to be applied in Europe. On the global pharmaceutical market, donepezil is represented by numerous generics: Arizex (India), Jasnal (Slovenia), Dementis (Greece), Palixid (Hungary) and some others. In Russia, the only drug of donepezil, Alzepil, is registered. The drug is produced by EGIS in Hungary and is available in the form of tablets of 5 and 10 mg.

Since 1996, donepezil has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease (AD) (Pfizer's Aricept). From 1997 began to be applied in Europe. On the global pharmaceutical market, donepezil is represented by numerous generics: Arizex (India), Jasnal (Slovenia), Dementis (Greece), Palixid (Hungary) and some others. In Russia, the only drug of donepezil, Alzepil, is registered. The drug is produced by EGIS in Hungary and is available in the form of tablets of 5 and 10 mg.

Since 2010, in the world practice for the treatment of moderate and severe BA, a sustained-release form of donepezil in a daily dose of 23 mg has also been used [1]. Other forms of donepezil are being developed for transdermal [2, 3] and intranasal [4, 5] administration.

The instructions for use of donepezil contain only one indication - BA. It is currently recommended for use in mild to moderate dementia [6]. In the USA, Canada, and Japan, it is also recommended for use at the stage of severe dementia [7]. The use of donepezil in AD is the most well studied. Some studies demonstrating its good efficacy in AD are presented in table .

The use of donepezil in AD is the most well studied. Some studies demonstrating its good efficacy in AD are presented in table .

Some studies demonstrating the efficacy and safety of donepezil 1999 США [8] III 473 30 5, 10 1999 Europe [9] III 818 24 20000 9000 9000 9000 Japanese Japanese Japanese, Japanese, Japanese. III 10 2000 США [12] 431 54 10 2004 England [13] 565 60 There are sufficiently grounds for the use of Donpezil and other diseases that are developing and leaving for developing and leaving for developing and leaving for developing Thus, its effectiveness in Lewy body disease has been shown [14, 15]. Most clinical studies show comparable efficacy and safety of the three cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, rivastigmine and galantamine) [19]. 2017 meta-analysis by L. Blanco-Silvente et al. [20] showed a greater improvement in overall experience with donepezil compared with galantamine and rivastigmine. It has also been shown that all cholinesterase inhibitors improve cognitive functions, functional activity, and increase life expectancy. Their influence on neuropsychiatric symptoms could not be identified. Similar data presented in a 2018 Cochrane review. Donepezil was effective in improving cognitive function, functional activity, and overall clinical impression. There was no effect of donepezil on behavioral disorders, which is associated with the short duration of clinical trials included in the review (most of them lasted no more than 6 months) [21]. The use of cholinesterase inhibitors is considered symptomatic therapy. But some data indicate that cholinesterase inhibitors may also have a nosomodifying effect. For example, a decrease in the increase in the degree of atrophy of the hippocampus, according to MRI of the brain, was shown against the background of taking 10 mg of donepezil for 1 year. However, in this study, despite slowing down atrophy, there was no clinical improvement in patients according to neuropsychological testing [22]. Donepezil has a long half-life, which is 70-100 hours. This allows you to take the drug once a day. The systematic use of single doses leads to the achievement of an equilibrium state within 2-3 weeks after the start of therapy. Communication with plasma proteins 95%. If the patient forgets to take the drug once, this does not significantly affect the therapeutic effect. At the same time, the long half-life and the relationship with plasma proteins require a more responsible approach to monitoring the development of side effects. Donepezil is metabolized in the liver with the participation of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes CYP2D6 and CYP3A4, undergoes glucuronidation. Four major metabolites of donepezil have been identified, two of which are active. Unlike tacrine at therapeutic doses, donepezil is not hepatotoxic. Hepatic enzyme inducers (phenytoin, carbamazepine, phenobarbital, dexamethasone) may accelerate and hepatic enzyme inhibitors (ketoconazole) may slow down the metabolism of donepezil. Donepezil is excreted by the kidneys both unchanged (15-20%) and in the form of numerous metabolites [23]. Donepezil is a reversible acetylcholinesterase inhibitor. It also affects the expression of nicotinic receptors in the brain, which may be especially important in severe dementia. The drug selectively inhibits acetylcholinesterase: its activity against acetylcholinesterase is approximately 1000 times higher than against butyrylcholinesterase. This explains the good tolerability of donepezil and the rare occurrence of peripheral cholinergic side effects. In the instructions, only hypersensitivity and children's age appear in the contraindications for use, which in itself indicates the relative safety of the drug. The tolerability and safety of donepezil are well described in S. Jackson et al. [25]. The frequency of side effects depends on the dose of the drug. The most common adverse events are gastrointestinal manifestations (nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain). In most cases, they pass on their own and do not require discontinuation of the drug. Nausea can be avoided by slowly titrating the dose. The recommended starting dose is 5 mg. With the development of nausea, it can be recommended to take 2.5 mg / day for 4-6 weeks, then for another 4-6 weeks - 5 mg / day, then 10 mg / day. It is recommended to switch to a dose of 23 mg/day no earlier than after 3 months of taking donepezil at a daily dose of 10 mg [26]. Since the maximum blood concentration is reached after 3-5 hours, taking in the evening also improves its tolerability. The decrease in peak concentration is facilitated by taking the drug after a meal. However, if the evening reception provokes sleep disturbances (insomnia, nightmares), the reception should be postponed to the morning. The development of sleep disorders is associated with excessive cholinergic stimulation during the peak dose of the pedunculopontine and dorsolateral nuclei of the brainstem, which are responsible for the development of the REM sleep phase. No sleep disturbances have been reported with donepezil in the morning. If sleep disturbances develop on the background of an increase in the dose of the drug, returning to the previous dose for a few more weeks may also contribute to the regression of side effects. Cardiovascular adverse events include the risk of bradycardia and QT interval prolongation. The possibility of developing bradycardia often leads clinicians to refrain from prescribing cholinesterase inhibitors in elderly patients. However, these concerns are based on reports of isolated cases of arrhythmia, while in clinical studies there was no increase in the incidence of bradycardia while taking donepezil. The incidence of bradycardia while taking donepezil does not exceed 1% and is comparable to the incidence of bradycardia while taking placebo. And serious consequences are even rarer. Monitoring heart rate (HR) at the beginning of taking the drug and with increasing doses allows you to timely detect bradycardia and adjust therapy. Administration of cholinesterase inhibitors may induce bradycardia or exacerbate existing cardiac arrhythmias. Therefore, sick sinus syndrome and impaired sinoatrial conduction are relative contraindications for the appointment of cholinesterase inhibitors. Theoretically, the risk of developing bradycardia may be influenced by the use of other drugs that slow the heart rate, such as digoxin and beta-blockers. When prescribing cholinesterase inhibitors, dose adjustment or withdrawal may be required. However, according to clinical studies, the simultaneous use of donepezil with digoxin or beta-blockers does not lead to an increase in the incidence of bradycardia [29]. Particularly revealing are the results of donepezil tolerance studies in patients with vascular dementia receiving a large number of drugs at the same time [30, 31]. No randomized controlled trial showed differences in heart rate, blood pressure, ECG values between cholinesterase inhibitors and placebo. In a number of studies, while taking donepezil, a decrease in heart rate by 2 beats per 1 min and an increase in the duration of the PR interval by 3 ms have been shown. However, there were no clinically significant manifestations. It has also been shown that the risk of progression of atrioventricular block I degree to II degree while taking donepezil does not increase. Patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease are no more likely to develop cardiovascular side effects than those with an uncomplicated history. Thus, at present, there are no sufficient grounds for identifying a high-risk group that would require a preliminary examination of the cardiovascular system before prescribing cholinesterase inhibitors [32-35]. There are reports that donepezil can provoke the development of epileptic seizures. In some cases, convulsive seizures develop against the background of cardiac arrhythmia, asystole. In a large, multicenter, randomized clinical trial, there was no difference in the incidence of side effects between the donepezil and placebo group. Against the background of donepezil, gastrointestinal side effects developed more often, but they were transient and not severe. The incidence of bradycardia did not differ between donepezil and placebo [36]. When using donepezil at a dose of 23 mg / day, 8.4% of patients showed a decrease in appetite, leading to a decrease in body weight. High doses of donepezil also increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding and bradycardia. Whereas the risk of arousal, hallucinations and falls does not increase with increasing dose [37]. The frequency of dizziness and fainting while taking cholinesterase inhibitors is also higher compared with taking placebo, part of the cases can be explained by the development of bradycardia. There is an opinion among clinicians that memantine is a safer drug for the treatment of dementia compared to other cholinesterase inhibitors. Perhaps it should be preferred in patients with an increased risk of developing cholinergic side effects (in patients with sick sinus syndrome, atrioventricular blockade, gastric ulcer, bronchial asthma). However, in patients not burdened with concomitant somatic pathology, the question of which drug is safer remains controversial. A French study compared serious side effects between donepezil and memantine monotherapy. It turned out that the frequency of side effects did not differ significantly: bradycardia was noted in 10 and 7% of cases, respectively, general weakness - in 5 and 6%, epileptic seizures - in 4 and 3%. Patients with severe dementia often receive combination therapy with donepezil and memantine. When adding memantine to donepezil, it is necessary to monitor heart rate, since memantine can potentiate the effect of donepezil on heart rate [41]. It is especially necessary to carefully monitor heart rate in patients receiving memantine simultaneously with high doses of donepezil (23 mg/day) [42]. We conducted a study on the efficacy and safety of donepezil in the treatment of dementia in neurodegenerative diseases. The aim of the study was to find out whether a gene polymorphism 9 is a predictor of the development of side effects of cholinesterase inhibitors.0280 CYP2D6 and MDR1 . As mentioned above, hepatic cytochrome CYP2D6 is involved in the metabolism of donepezil. Gene MDR1 encodes p-glycoprotein, which is involved in the absorption of the drug in the gastrointestinal tract, in its elimination by the kidneys and bile, and also in the penetration of donepezil through the blood-brain barrier. With its low activity, it is possible to slow down its excretion from the central nervous system. Increasing the concentration of donepezil in the brain tissues above the therapeutic level may lead to an increased risk of developing central side effects. The study included 62 patients with dementia due to various neurodegenerative diseases: 16 with AD, 25 with dementia with Lewy bodies and 21 with Parkinson's disease with dementia. The mean age of the patients was 76. All patients were treated with donepezil at an initial dose of 5 mg/day for 1 month followed by an increase in daily dose to 10 mg. All patients took donepezil in the evening. Along with a cholinesterase inhibitor, 58.5% of patients were taking memantine, the duration of treatment at a stable dosage was at least 6 months before the start of the study. Of the 62 patients included in the study, 59.7% ( n = 37) started on donepezil. Particularly low compliance was observed in patients with Parkinson's disease, 23. Of all the follow-up patients, only 26 patients took donepezil during the entire period between examinations. The effectiveness of treatment was assessed based on the dynamics of the score on the MMSE scale. The interval between examinations was 6.8±3.1 months. At the same time, a poor response to treatment was noted no earlier than 6 months after the start of therapy. Since there is no consensus on what change in MMSE score is considered a good response to treatment, we took two approaches. In the first, more stringent, analysis, only those patients who had an increase or decrease on the MMSE scale of 2 points or more were included in the analysis. Eight patients did not respond to donepezil treatment, 9 responded well. Thus, when applying strict criteria, 34.6% of patients who started donepezil responded well to treatment. When analyzing gene polymorphism CYP2D6 GA/GG ratio among those who responded well to treatment was 6/3, among those who did not respond - 4/4. When analyzing the polymorphism of the MDR1 gene, the ratio of CC/TC/TT among those who responded well to treatment was 2/5/2, among those who did not respond — 2/5/1. The data obtained allow us to reject the hypothesis that the presence of the CYP2D6 mutant A allele and the MDR1 mutant T allele of the MDR1 gene is associated with a poor response to treatment. The second case used a clinical approach. Patients with a decrease in MMSE score by 2 or more ( n =8). Patients in this group were advised to replace donepezil with rivastigmine, galantamine, or memantine. All other patients (with improvement and stabilization of cognitive status) were classified as responders ( n =18) and were advised to continue therapy with donepezil. Thus, 69.2% of patients responded to treatment. When analyzing the polymorphism of the CYP2D6 gene , the ratio of GA/GG among those who responded to treatment was 8/10, among those who did not respond — 4/4. When analyzing gene polymorphism MDR1 the CC/TC/TT ratio was 6/7/5 among responders and 2/5/1 among non-responders. The obtained data also do not allow us to associate the presence of the CYP2D6 mutant A allele and the MDR1 mutant T allele of the gene with a poor response to treatment. The development of side effects was noted in 7 patients (18. The average age of 7 patients with developed side effects was 79. Analysis of the single nucleotide polymorphism G1846A of the CYP2D6 gene of these 7 patients showed that all of them are wild-type GG homozygotes. Thus, the presence of the mutant allele A of gene CYP2D6 does not appear to be associated with an increased risk of side effects. The same genotype of patients with side effects is probably associated with a high prevalence of the G allele in the population and a low incidence of side effects. Central side effects were noted in 3 patients. As mentioned above, tremor increased in 1 patient with Parkinson's disease while taking 5 mg of donepezil (TC genotype for gene MDR1 ). In 1 patient with BA (genotype TT for gene MDR1 ) and 1 patient with dementia with Lewy bodies (genotype CC for the gene MDR1 ) developed aggressive behavior while taking 5 mg of donepezil. Thus, donepezil was well tolerated in our study. Side effects developed rarely (18.9%) and in all cases regressed after discontinuation or dose reduction of the drug. No gastrointestinal side effects were noted, although dyspeptic symptoms (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea) are considered common side effects of cholinesterase inhibitors. It is likely that the administration of the drug in the evening and the slow titration of the dose help to avoid their development. While taking donepezil at night, no sleep disturbances were detected. The possibility of developing bradycardia while taking a cholinesterase inhibitor makes it recommended to control the pulse at the beginning of therapy and when increasing the dose. It may also be necessary to adjust the dose or cancel other drugs that slow down the pulse (primarily beta-blockers). In our study, no cases of epileptic seizures were noted while taking donepezil. Cases of donepezil poisoning are reported in the literature. With a tenfold excess of the dose in elderly patients, the development of bradycardia was noted, which required hospitalization and was stopped against the background of the administration of atropine [43-45]. When a 2-year-old child accidentally took donepezil and memantine, he developed agitation and visual hallucinations. The child was hospitalized. The concentration of donepezil in the blood exceeded the therapeutic one by 10 times, the concentration of memantine was lower than the therapeutic one (recommended for adult patients). The child's condition returned to normal after 3 days [46]. A case of poisoning of a 14-year-old teenager is described due to the intake of one tablet of donepezil 10 mg. He was disturbed by gastrointestinal manifestations (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea) and drowsiness, which later gave way to episodes of arousal. Heart rate upon admission to the hospital 140 beats. in 1 min. The teenager was discharged from the hospital on the 5th day [47]. In case of an overdose of donepezil, the most dangerous is the development of bradycardia. There is no specific antidote; atropine may be required. Due to the long half-life and association with plasma proteins, hospitalization of the patient is recommended in case of poisoning. Undesirable phenomena are stopped within a few days. Also, when treating patients with dementia, it is necessary to draw the attention of relatives to the need to control the intake of medicines. Physicians now often avoid prescribing cholinesterase inhibitors when they are indicated because of an overestimation of the risk of side effects. Due to the safety of the use of cholinesterase inhibitors, they should be used more frequently and more widely in neurological and psychiatric practice. The authors declare no conflict of interest. The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Obesity is a metabolic disorder that is becoming an epidemic. According to the ESSE-RF epidemiological study, there is an increase in the prevalence of obesity in Russia, diagnosed both by body mass index (BMI) and by waist circumference (WC). It was found that at the age of 35–44 years, 26.6% of men and 24.5% of women are obese, at the age of 45–54 years - 31.7% of men and 40.9% of women.% of women, aged 55–64 years - 35.7% of men and 52.1% of women [2]. Obesity, especially its visceral form, increases the risk of arterial hypertension (AH), type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke, cholelithiasis, osteoarthritis, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and certain cancers. The epicardial visceral fat depot is the most studied in terms of the presence of a relationship with cardiovascular diseases. A number of studies have demonstrated the association of epicardial fat (EF) with myocardial hypertrophy and fibrosis, preclinical decrease in LV diastolic and systolic function [7]. In this regard, the main goal of the treatment of obesity is not only weight loss, but also to reduce the risk of comorbidities, increase life expectancy. Currently, the method of gradual (0.5–1.0 kg per week) weight loss for 6 months or more is considered the safest and at the same time effective method of weight loss, while losing 5–10% of the initial body weight, mainly due to adipose tissue. rather than through loss of muscle mass or fluid. For weight loss, drug and non-drug therapies are used, including diet, regular exercise, and changes in eating behavior. One of the drugs for the treatment of obesity, approved in the Russian Federation, is a serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor - sibutramine. In a number of studies, in particular in the PrimaVera program, good efficacy and safety of the drug in long-term use in patients with obesity were shown [9]. According to the instructions for use, sibutramine is prescribed to patients with hypertension with extreme caution due to a possible increase in blood pressure (BP). Considering that patients with visceral obesity often develop hypertension, the aim of our study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of sibutramine in patients with comorbidities on the background of antihypertensive therapy, as well as to study the effect of the drug on epicardial fat depot with long-term use. Participants and study design The study included 57 patients with hypertension and obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m²) aged 35–60 years. Anthropometric measurements Height and weight were measured, body mass index (BMI) was calculated, waist circumference (WC), hip circumference (HR) was determined, the ratio WC/HR, WC/height was calculated. All measurements are necessary to diagnose obesity, identify the type of distribution of adipose tissue and assess the dynamics of weight loss. Methods of BP measurement All patients underwent office BP measurement at each visit. The procedure was performed three times in a sitting position, after a 15-minute rest, the first measurement was excluded from the analysis. The mean value of 2 consecutive measurements taken at 5-minute intervals was calculated. Between visits, patients performed self-monitoring of blood pressure in the morning and evening hours using a shoulder automatic tonometer. All patients before treatment and after 7 months of observation underwent 24-hour BP monitoring using the BPLab system (Russia). Echocardiography Echocardiography was performed with the S4 transducer in the second harmonic mode with a frequency range of 1.8–3.6 MHz on a VIVID 7 device from General Electric (USA) in accordance with the recommendations of the Committee for Nomenclature and Standardization of the American Association of Echocardiography (ASE) ). All studies were performed in M- and B-modes using standard positions. The study of the left ventricle included the measurement of end-diastolic (ECD, cm) and end-systolic (ECR, cm) dimensions, thickness of the interventricular septum in systole and diastole (IVSD, cm) and posterior wall in systole and diastole (ECD, cm) from the parasternal position along the long axis. The mass of the LV myocardium was calculated by the formula: MMLV = 1. Estimation of epicardial fat depot EA thickness was measured at baseline and after 7 months of follow-up during echocardiography. The echo-negative space between the myocardium and the visceral layer of the pericardium behind the free wall of the right ventricle was assessed in the parasternal position along the long axis. The measurement was taken at the end of systole, with the ultrasound beam directed perpendicular to the aortic annulus used as an anatomical landmark. The mean value was calculated from 3 consecutive measurements. Ethical review A. Statistical analysis Statistical processing of the material was carried out using the licensed software package Stastica 10.0 Statsoft (USA). When choosing a data comparison method, the normality of the distribution of the trait in subgroups was taken into account, taking into account the Shapiro-Wilk test. With a normal distribution, the mean and standard deviation were calculated. The null hypothesis when comparing groups was rejected at a significance level of less than 0.05. Delta (Δ) was calculated as the difference between repeated and baseline measurements. For multiple comparisons, one-way ANOVA was used. The relationship between the two features was assessed using the Pearson correlation coefficient. General characteristics of the patients included in the study are presented in Table. Parameter Men Women Quantity, n (%) 22 (38.6) 35 (61.4) Age, years 50.2±8.1 48.9±8.5 BMI, kg/m² 35.2±4.3 35.3±4.1 FROM, see 120±10.8 107.9±8.6 FROM/OB 1.02±0.04 0.89±0.05 OT/height 0.67±0.07 0.66±0.06 Office CAD, mmHg 127. 128.4±7.4 Office DBP, mmHg 78.7±6.4 80.8±4.9 LVMI, g/m² 116.5±19.4 98.4±11.9 LV hypertrophy, n (%) 18 (81.2) 24 (68.6) EJ thickness, cm 0.85±0.18 0.73±0.16 Average daily SPV, m/s 11.9±1.2 11.1±1.5 Disorder of carbohydrate metabolism, n (%) 7 (31.8) 10 (28.6) Dyslipidemia, n (%) 21 (95.5) 26 (74.2) Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; OT - waist circumference; OB - hip circumference; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; LVMI - indexed mass of the myocardium of the left ventricle; EJ, epicardial fat; PWV is the speed of the pulse wave. During the 1st month of follow-up, patients were advised to follow a diet and follow general recommendations for weight loss. At the end of this period, a slight change in weight and other anthropometric indicators was revealed (Table 2). On average, patients lost 2 kg, which was less than 2% of the initial weight. While taking sibutramine at a daily dose of 10 mg for 1 month, a more significant weight loss was detected, by an average of 3.7 kg, which amounted to more than 2% of the initial body weight. In the future, the rate of weight loss slowed down and by the end of the observation period (6 months of taking sibutramine) averaged 8.6 kg (6.2% of the original). While taking sibutramine, there was a significant decrease in WC and WC/growth, more pronounced in women. Significant changes in WC/VR were not revealed, since the volume of the hips (VR) decreased in proportion to the change in VR. Table 2. Dynamics of anthropometric parameters in patients with obesity and arterial hypertension before and after treatment with sibutramine Index 1 month, n=57 (diet) 1 month, n=57 (diet+sibutramine) 6 months, n=57 (diet+sibutramine) ∆ weight, kg 2. 3.7±0.9 8.6±1.7# ∆ weight, % 1.8±0.2 2.2±0.8 6.2±1.4# ∆ FROM, cm (men) 0.7±0.1 1.4±0.3* 3.7±0.7# ∆ FROM, cm (women) 1.2±0.2 3.4±0.9* 7.1±1.2# ∆ OT/OB (men) 0 0.1 0.2 ∆ OT/V (women) 0.1 0.2 0.3 ∆ OT/height 0.1 0.2 0.4# Abbreviations: OT - waist circumference; OB - hip circumference; * – p<0. When analyzing the dynamics of echocardiographic parameters (Table 3), a trend towards a decrease in LVMI was revealed, more pronounced in women. According to recent data, indexing of LVL to body surface area (BSA) in obese patients may be inaccurate, especially when losing weight. In this regard, it is recommended to index LVML for growth 2.7 . When analyzing the dynamics of this indicator, a more significant decrease was revealed, which became significant in women. The number of patients with impaired LV geometry slightly decreased (from 74 to 63%). Against the background of long-term therapy with sibutramine, there was a slight decrease in the thickness of the EA (from 0.79 to 0.71 cm). A more detailed analysis revealed that in women the dynamics of this indicator was significantly more pronounced than in men. Given the more significant dynamics of weight and other anthropometric indicators, we can say that in our study, women lost weight better than men. Table 3. Dynamics of echocardiographic parameters in patients with obesity and arterial hypertension on the background of 6-month sibutramine therapy Index Before treatment After treatment LVMI, g/m² men 116.6±19.4 107.5±18.6 LVMI, g/m² women 98.4±11.9 86.4±16.7 LVMI, g/m2.7 men 49.8±7.9 45.6±6.1 LVMI, g/m2.7 women 47.7±7.4 42.8±6.3* LVH, n (%} 42 (73.7) 36 (63.1) EJ thickness, cm men 0. 0.81±0.13 EJ thickness, cm women 0.73±0.16 0.61±0.15* Abbreviations: LVMI, indexed left ventricular myocardial mass; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; DD - diastolic dysfunction; EJ, epicardial fat; * – p<0.05 when compared before treatment. During follow-up, side effects of sibutramine were detected in 26.3% of study participants (Table 4). Most often, patients complained of constipation (12.3%) and dry mouth (10.6%). The severity of symptoms persisted during the 1st month of sibutramine therapy, then decreased. Cancellation of the drug, additional appointments were not required. Complaints about palpitations occurred in 2 (3.5%) patients, while during the general examination and according to the ECG data, tachycardia was not detected. The average heart rate according to ECG was 71.5±8.2 beats/min before treatment and 70. Table 4. Incidence of side effects of sibutramine in patients with obesity and arterial hypertension Side effect Frequency occurrences, n (%) Constipation 7 (12.3) Dry mouth 6 (10. Heartbeat 2 (3.5) Insomnia 1 (1.8) Nausea 1 (1.8) The rate of obesity in all countries is comparable to the epidemic, and the choice of drugs for the treatment of the disease is limited. One of the few drugs approved in Russia for the treatment of obesity is sibutramine. A number of studies have proven the efficacy and safety of the drug in long-term use. So, about 70 thousand patients with obesity participated in the All-Russian Observational Program "PrimaVera". Most of them were prescribed sibutramine at a daily dose of 10-15 mg for a period of 3 months to 1 year. According to the results of the study, about 65% of patients achieved a clinically significant weight loss of 10% or more after 6-12 months of taking the drug. At the same time, adverse events were registered in only 4. Similar results were obtained in the observational program "Spring", also carried out in Russia. It involved about 35 thousand patients with alimentary obesity aged 18 to 60 years [11]. All patients were prescribed sibutramine (reduxin) at a daily dose of 10–15 mg. Study Limitations The main limitation of this study is the small number of patients included. Also, taking into account the presence of concomitant pathology and metabolic disorders, patients were prescribed sibutramine at a daily dose of 10 mg. No further dose titration was performed. The prevalence of obesity and associated diseases is steadily increasing. Drug therapy of obesity contributes to more effective weight loss, affects the nature of the distribution of adipose tissue, and slows down the development of comorbidities. Funding source. Preparation and publication of the manuscript were carried out at the personal expense of the team of authors. There were no additional sources of funding. Conflict of interest. The authors declare no apparent or potential conflicts of interest related to the publication of this article. Contributors . All authors made a significant contribution to the study and preparation of the article: recruitment of patients (Shupenina E.Yu., Dubrovina A.V.), planned studies (Shupenina E.Yu., Dubrovina A.V., Yureneva S.V.) , statistical data processing (Shupenina E.Yu., Dubrovina A.V.), reading and reviewing of the article (Vasyuk Yu.A., Yushchuk E.N., Yureneva S.V.). 9000 5, 10

9000 5, 10  Donepezil is used for traumatic brain injury [16], vascular dementia [17], and Parkinson's disease with dementia [18]. However, the prescription of donepezil for these nosologies remains off-label.

Donepezil is used for traumatic brain injury [16], vascular dementia [17], and Parkinson's disease with dementia [18]. However, the prescription of donepezil for these nosologies remains off-label.

When using donepezil at a dose of 5 mg/day, the average activity of acetylcholinesterase is reduced by 63.7%, at a dose of 10 mg/day - by 77.3% [24].

When using donepezil at a dose of 5 mg/day, the average activity of acetylcholinesterase is reduced by 63.7%, at a dose of 10 mg/day - by 77.3% [24].  The effectiveness of a gradual increase in the dose of the drug to reduce the risk of side effects has been shown in comparative studies of rapid and gradual increase in the dose of donepezil [27, 28].

The effectiveness of a gradual increase in the dose of the drug to reduce the risk of side effects has been shown in comparative studies of rapid and gradual increase in the dose of donepezil [27, 28].

Morning administration of the drug is more preferable in patients with an increased risk of developing bradycardia. If the patient has a pacemaker implanted, one should not be afraid of the development of a heart rhythm disorder during cholinergic therapy.

Morning administration of the drug is more preferable in patients with an increased risk of developing bradycardia. If the patient has a pacemaker implanted, one should not be afraid of the development of a heart rhythm disorder during cholinergic therapy.  The use of cholinesterase inhibitors does not increase the frequency of ischemic attacks.

The use of cholinesterase inhibitors does not increase the frequency of ischemic attacks.  Considering that donepezil is used mainly in patients of the older age group with neurodegenerative diseases, the development of an epileptic seizure may not always be associated with taking the drug. Perhaps epileptic seizures are a manifestation of the disease itself.

Considering that donepezil is used mainly in patients of the older age group with neurodegenerative diseases, the development of an epileptic seizure may not always be associated with taking the drug. Perhaps epileptic seizures are a manifestation of the disease itself.  But the risk of falls while taking donepezil not only does not increase, but also decreases [38, 39]. On the one hand, walking disorders, like cognitive impairments, can develop as a result of cholinergic deficiency. On the other hand, the improvement in walking may be mediated by the correction of a dysregulatory cognitive defect (primarily by improving attention).

But the risk of falls while taking donepezil not only does not increase, but also decreases [38, 39]. On the one hand, walking disorders, like cognitive impairments, can develop as a result of cholinergic deficiency. On the other hand, the improvement in walking may be mediated by the correction of a dysregulatory cognitive defect (primarily by improving attention).  It should be noted that such phenomena in elderly patients often develop even without taking antidementia drugs, and it is not always possible to unambiguously establish the relationship between deterioration in well-being and taking the drug [40].

It should be noted that such phenomena in elderly patients often develop even without taking antidementia drugs, and it is not always possible to unambiguously establish the relationship between deterioration in well-being and taking the drug [40].  Slowing down the metabolism of the drug can lead to an increase in its plasma concentration above the therapeutic one and be accompanied by the development of side effects associated primarily with excessive peripheral cholinergic stimulation.

Slowing down the metabolism of the drug can lead to an increase in its plasma concentration above the therapeutic one and be accompanied by the development of side effects associated primarily with excessive peripheral cholinergic stimulation.  6±5.3 years with a range of 59-86 years. The gender distribution is 40 (64.5%) women and 22 (34.5%) men. The baseline score on the Mini Mental Status Assessment (MMSE) was 22.0±6.0. In patients with mild dementia - 20-23 points, with AD - 20-30 points, with Lewy body disease and Parkinson's disease with dementia - 19(30.6%), with moderate dementia (11-19 points) - 43 (69.4%). Patients with severe dementia (10 points or less on the MMSE scale) were not included in the study.

6±5.3 years with a range of 59-86 years. The gender distribution is 40 (64.5%) women and 22 (34.5%) men. The baseline score on the Mini Mental Status Assessment (MMSE) was 22.0±6.0. In patients with mild dementia - 20-23 points, with AD - 20-30 points, with Lewy body disease and Parkinson's disease with dementia - 19(30.6%), with moderate dementia (11-19 points) - 43 (69.4%). Patients with severe dementia (10 points or less on the MMSE scale) were not included in the study.  8% ( n = 5) started taking donepezil, which may be due to the need for a large number of anti-Parkinsonian drugs during the day at an advanced stage of Parkinson's disease. Some patients stop taking it because they do not see the same obvious effect as from taking antiparkinsonian drugs. Among patients with dementia with Lewy bodies, 44.0% were started on donepezil ( n =11), among patients with BA - 62.5% ( n =10). The greater adherence to treatment of patients with primary dementing diseases compared with patients with Parkinson's disease is undoubtedly associated with the control of medication intake by patients' relatives.

8% ( n = 5) started taking donepezil, which may be due to the need for a large number of anti-Parkinsonian drugs during the day at an advanced stage of Parkinson's disease. Some patients stop taking it because they do not see the same obvious effect as from taking antiparkinsonian drugs. Among patients with dementia with Lewy bodies, 44.0% were started on donepezil ( n =11), among patients with BA - 62.5% ( n =10). The greater adherence to treatment of patients with primary dementing diseases compared with patients with Parkinson's disease is undoubtedly associated with the control of medication intake by patients' relatives.  If the improvement was evident already after 3 months of therapy, the patient was considered to have responded well to treatment.

If the improvement was evident already after 3 months of therapy, the patient was considered to have responded well to treatment.

9% of 37 patients who started taking the drug). Two patients with Parkinson's disease were unable to take donepezil 5 mg due to an increase in blood pressure, which returned to normal after discontinuation of the drug and re-emerged when the drug was resumed. In 1 patient with Parkinson's disease, while taking donepezil 5 mg, an increase in tremor was noted, which regressed after discontinuation of the drug. In 1 patient with AD and 1 patient with dementia with Lewy bodies, relatives noted the development of aggressive behavior on the background of the start of donepezil, which regressed after discontinuation of the drug. Two patients (with Parkinson's disease and Lewy body disease) could not take the drug due to the development of bradycardia while taking the minimum dose. Another 1 patient with asthma noted the development of bradycardia when trying to increase the dose of donepezil to 10 mg/day, and therefore continued taking the drug at the minimum dose.

9% of 37 patients who started taking the drug). Two patients with Parkinson's disease were unable to take donepezil 5 mg due to an increase in blood pressure, which returned to normal after discontinuation of the drug and re-emerged when the drug was resumed. In 1 patient with Parkinson's disease, while taking donepezil 5 mg, an increase in tremor was noted, which regressed after discontinuation of the drug. In 1 patient with AD and 1 patient with dementia with Lewy bodies, relatives noted the development of aggressive behavior on the background of the start of donepezil, which regressed after discontinuation of the drug. Two patients (with Parkinson's disease and Lewy body disease) could not take the drug due to the development of bradycardia while taking the minimum dose. Another 1 patient with asthma noted the development of bradycardia when trying to increase the dose of donepezil to 10 mg/day, and therefore continued taking the drug at the minimum dose.  4±6.4 years, among them 57.1% ( n =4) women and 42.9% ( n =3) men. Thus, the distribution by gender and age in the group of patients with developed side effects does not differ from the distribution in the general group.

4±6.4 years, among them 57.1% ( n =4) women and 42.9% ( n =3) men. Thus, the distribution by gender and age in the group of patients with developed side effects does not differ from the distribution in the general group.  Thus, it is also not possible to link the development of central side effects with the polymorphism of the MDR1 gene.

Thus, it is also not possible to link the development of central side effects with the polymorphism of the MDR1 gene.

Experience with sibutramine in obese patients with controlled hypertension | Shupenina

JUSTIFICATION

The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared obesity one of the most common chronic diseases among the adult population, which is no longer just a problem associated with malnutrition. In 2014, 1.9billion people over the age of 18 worldwide have been identified as overweight, of which 600 million are obese. According to WHO, in Europe in 2015 obesity was detected in 21.5% of men and 24.5% of women. It is assumed that the number of people with obesity by 2030 will be 1.1 billion [1].

The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared obesity one of the most common chronic diseases among the adult population, which is no longer just a problem associated with malnutrition. In 2014, 1.9billion people over the age of 18 worldwide have been identified as overweight, of which 600 million are obese. According to WHO, in Europe in 2015 obesity was detected in 21.5% of men and 24.5% of women. It is assumed that the number of people with obesity by 2030 will be 1.1 billion [1].  Visceral obesity is also associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular and overall mortality [3]. The results of recent studies show that visceral obesity and its consequences are based on an imbalance in the body's neurohumoral systems, a deficiency in the functional forms of natriuretic peptides, and the development of selective insulin, leptin, and adiponectin resistance. Given the heterogeneity of obese patients, it is reasonable to distinguish disease phenotypes such as metabolically healthy and metabolically active obesity. Most obese patients (60–90%) refers to the metabolically active phenotype. They are characterized by a visceral (abdominal) distribution of adipose tissue, the presence of metabolic disorders and associated diseases [4, 5]. The pathogenesis of obesity-associated diseases is based on chronic inflammation that causes insulin resistance, endothelial dysfunction with increased vascular tone, left ventricular (LV) diastolic dysfunction, and myocardial fibrosis [6].

Visceral obesity is also associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular and overall mortality [3]. The results of recent studies show that visceral obesity and its consequences are based on an imbalance in the body's neurohumoral systems, a deficiency in the functional forms of natriuretic peptides, and the development of selective insulin, leptin, and adiponectin resistance. Given the heterogeneity of obese patients, it is reasonable to distinguish disease phenotypes such as metabolically healthy and metabolically active obesity. Most obese patients (60–90%) refers to the metabolically active phenotype. They are characterized by a visceral (abdominal) distribution of adipose tissue, the presence of metabolic disorders and associated diseases [4, 5]. The pathogenesis of obesity-associated diseases is based on chronic inflammation that causes insulin resistance, endothelial dysfunction with increased vascular tone, left ventricular (LV) diastolic dysfunction, and myocardial fibrosis [6].

Due to this double effect, a feeling of fullness is achieved and the amount of food consumed is reduced, energy consumption increases as a result of increased thermogenesis [8].

Due to this double effect, a feeling of fullness is achieved and the amount of food consumed is reduced, energy consumption increases as a result of increased thermogenesis [8]. PURPOSE

METHODS

All patients at baseline and after 7 months of follow-up underwent a comprehensive clinical, instrumental and laboratory examination, including a general examination with anthropometric measurements, electrocardiography (ECG), office BP measurement, 24-hour BP monitoring with aortic stiffness analysis, and echocardiography (EchoCG). The study included patients with controlled hypertension on antihypertensive therapy with office BP <140/90 mmHg During the 1st month of observation, all patients were recommended a diet with caloric restriction of food up to 1500 kcal/day in women and 1800 kcal/day in men, regular physical activity up to 30 minutes per day, changes in eating behavior (reducing the size of portions, limiting consumption food in the evening and at night, regular frequent meals of a small amount of food). At the end of the 1st month, sibutramine (reduxin, Promomed, Russia) was added to non-drug therapy at a dose of 10 mg per day. Control visits to evaluate the efficacy and safety were carried out after 1 and 6 months of taking the drug.

All patients at baseline and after 7 months of follow-up underwent a comprehensive clinical, instrumental and laboratory examination, including a general examination with anthropometric measurements, electrocardiography (ECG), office BP measurement, 24-hour BP monitoring with aortic stiffness analysis, and echocardiography (EchoCG). The study included patients with controlled hypertension on antihypertensive therapy with office BP <140/90 mmHg During the 1st month of observation, all patients were recommended a diet with caloric restriction of food up to 1500 kcal/day in women and 1800 kcal/day in men, regular physical activity up to 30 minutes per day, changes in eating behavior (reducing the size of portions, limiting consumption food in the evening and at night, regular frequent meals of a small amount of food). At the end of the 1st month, sibutramine (reduxin, Promomed, Russia) was added to non-drug therapy at a dose of 10 mg per day. Control visits to evaluate the efficacy and safety were carried out after 1 and 6 months of taking the drug.

The average daily, daytime and nighttime values of systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were analyzed, the degree of nighttime decrease, variability and morning dynamics of blood pressure were assessed.

The average daily, daytime and nighttime values of systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were analyzed, the degree of nighttime decrease, variability and morning dynamics of blood pressure were assessed.  08 × (1.04 × [(RDR + TZSD + TMZhPd) 3 -KDR 3 ])+0.6 g; where LVMI is the mass of the LV myocardium, TMZhPd is the thickness of the interventricular septum in diastole, TZSd is the thickness of the posterior wall in diastole, EDD is the end-diastolic size in diastole. LV hypertrophy was diagnosed if the LVML index (iMLZH) exceeded 95 g/m 2 in women and 115 g/m 2 in men.

08 × (1.04 × [(RDR + TZSD + TMZhPd) 3 -KDR 3 ])+0.6 g; where LVMI is the mass of the LV myocardium, TMZhPd is the thickness of the interventricular septum in diastole, TZSd is the thickness of the posterior wall in diastole, EDD is the end-diastolic size in diastole. LV hypertrophy was diagnosed if the LVML index (iMLZH) exceeded 95 g/m 2 in women and 115 g/m 2 in men.  I. Evdokimov. All patients, when included in the study, signed an informed consent form in 2 copies. One of them was handed out to the patient.

I. Evdokimov. All patients, when included in the study, signed an informed consent form in 2 copies. One of them was handed out to the patient. RESULTS

1. Women predominated among the study participants. All patients had visceral obesity, confirmed by anthropometric data: BMI ≥30 kg/m², WC >102 cm in men and >88 cm in women, WC/OB >0.9 in men and >0.85 in women, WC /height ≥0.5. At inclusion in the study, patients were on effective antihypertensive therapy, which was confirmed by the results of office BP measurement. According to echocardiography, most patients had impaired LV geometry by the type of concentric remodeling or concentric hypertrophy, which is typical for obesity and hypertension. Also, an increase in one of the main parameters of aortic stiffness, the pulse wave velocity (PWV), was determined as part of the daily monitoring of blood pressure. Approximately one third of patients were found to have disorders of carbohydrate metabolism, in particular impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 diabetes mellitus. Almost all patients had dyslipidemia, manifested by an increase in the level of total cholesterol (6.5±1.0 mmol/l), low-density lipoprotein (LDL) concentration (3.

1. Women predominated among the study participants. All patients had visceral obesity, confirmed by anthropometric data: BMI ≥30 kg/m², WC >102 cm in men and >88 cm in women, WC/OB >0.9 in men and >0.85 in women, WC /height ≥0.5. At inclusion in the study, patients were on effective antihypertensive therapy, which was confirmed by the results of office BP measurement. According to echocardiography, most patients had impaired LV geometry by the type of concentric remodeling or concentric hypertrophy, which is typical for obesity and hypertension. Also, an increase in one of the main parameters of aortic stiffness, the pulse wave velocity (PWV), was determined as part of the daily monitoring of blood pressure. Approximately one third of patients were found to have disorders of carbohydrate metabolism, in particular impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 diabetes mellitus. Almost all patients had dyslipidemia, manifested by an increase in the level of total cholesterol (6.5±1.0 mmol/l), low-density lipoprotein (LDL) concentration (3. 7±1.1 mmol/l) and triglycerides (2.4 ±0.9mmol / l), a decrease in the concentration of high density lipoproteins (HDL) (1.0 ± 0.09 mmol / l in men, 1.2 ± 0.07 mmol / l in women).

7±1.1 mmol/l) and triglycerides (2.4 ±0.9mmol / l), a decrease in the concentration of high density lipoproteins (HDL) (1.0 ± 0.09 mmol / l in men, 1.2 ± 0.07 mmol / l in women).  5±11.6

5±11.6

1±0.6

1±0.6  05 compared to 1 month (diet), # – p<0.05 compared to 1 month diet + sibutramine.

05 compared to 1 month (diet), # – p<0.05 compared to 1 month diet + sibutramine.

85±0.18

85±0.18  5±12.8 beats/min after treatment. The study included patients with controlled hypertension. At all scheduled visits, office BP measurements were performed; between visits, patients measured BP at home with filling in the appropriate diary; 24-hour BP monitoring (ABPM) was performed before and after sibutramine therapy. There were no episodes of clinically significant increase in blood pressure during 6 months of sibutramine therapy. The mean daily SBP and DBP in the study group before treatment was 126.3±8.9mmHg. and 81.2±9.1 mm Hg. respectively, after treatment – 127.6±9.3 mm Hg. and 80.7±7.3 mm Hg. respectively.

5±12.8 beats/min after treatment. The study included patients with controlled hypertension. At all scheduled visits, office BP measurements were performed; between visits, patients measured BP at home with filling in the appropriate diary; 24-hour BP monitoring (ABPM) was performed before and after sibutramine therapy. There were no episodes of clinically significant increase in blood pressure during 6 months of sibutramine therapy. The mean daily SBP and DBP in the study group before treatment was 126.3±8.9mmHg. and 81.2±9.1 mm Hg. respectively, after treatment – 127.6±9.3 mm Hg. and 80.7±7.3 mm Hg. respectively.

6)

6) DISCUSSION

1% of program participants [9]. In our study, the dynamics of weight loss was less pronounced (about 6%), and the frequency of adverse events reached 26.3%, which may be due to the more common visceral form of obesity included in our study, the presence of metabolic disorders. The PrimaVera program included 6.5% of patients with controlled hypertension. During the observation period, episodes of clinically significant increase in blood pressure (more than 10 mmHg during 2 consecutive visits) were recorded in 26% of patients, but this did not lead to discontinuation of sibutramine [10]. In our study, there were no episodes of a clinically significant increase in blood pressure, which was confirmed by the data of self-monitoring, office and daily measurement of blood pressure.

1% of program participants [9]. In our study, the dynamics of weight loss was less pronounced (about 6%), and the frequency of adverse events reached 26.3%, which may be due to the more common visceral form of obesity included in our study, the presence of metabolic disorders. The PrimaVera program included 6.5% of patients with controlled hypertension. During the observation period, episodes of clinically significant increase in blood pressure (more than 10 mmHg during 2 consecutive visits) were recorded in 26% of patients, but this did not lead to discontinuation of sibutramine [10]. In our study, there were no episodes of a clinically significant increase in blood pressure, which was confirmed by the data of self-monitoring, office and daily measurement of blood pressure.  The observation period was 6 months. On the background of sibutramine therapy, weight loss was observed by an average of 14.3%, WC decreased by an average of 11 cm. In our study, WC decreased more significantly in women - by an average of 7 cm, which was accompanied by a significant decrease in the thickness of the EA and could indicate regression visceral obesity in these patients. Adverse events were reported in 2.8% of patients. The most common complaints in our study were dry mouth and constipation.

The observation period was 6 months. On the background of sibutramine therapy, weight loss was observed by an average of 14.3%, WC decreased by an average of 11 cm. In our study, WC decreased more significantly in women - by an average of 7 cm, which was accompanied by a significant decrease in the thickness of the EA and could indicate regression visceral obesity in these patients. Adverse events were reported in 2.8% of patients. The most common complaints in our study were dry mouth and constipation. CONCLUSION

The drug sibutramine (reduxin) approved in Russia at a daily dose of 10 mg is an effective and safe drug that can be used in patients with visceral obesity in combination with controlled hypertension.

The drug sibutramine (reduxin) approved in Russia at a daily dose of 10 mg is an effective and safe drug that can be used in patients with visceral obesity in combination with controlled hypertension. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION.

Learn more