Can schizophrenia be prevented

Is It Possible to Prevent Schizophrenia?

Written by Kara Mayer Robinson

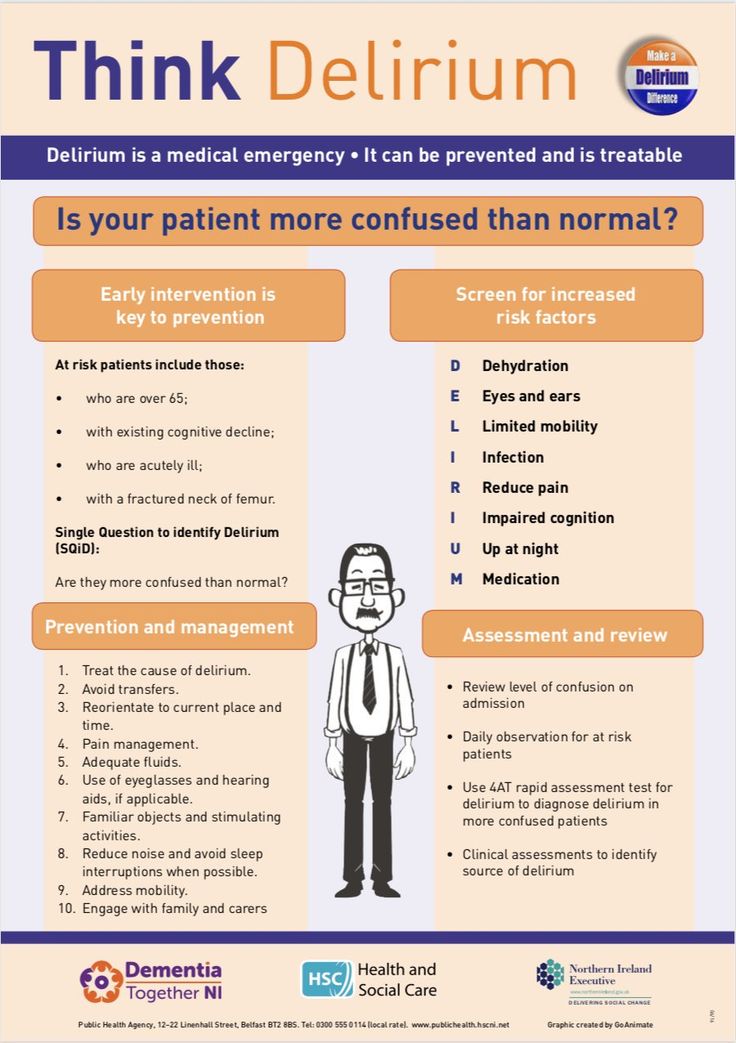

Although there is no proven way to prevent schizophrenia, scientists are looking for ways to make it less likely.

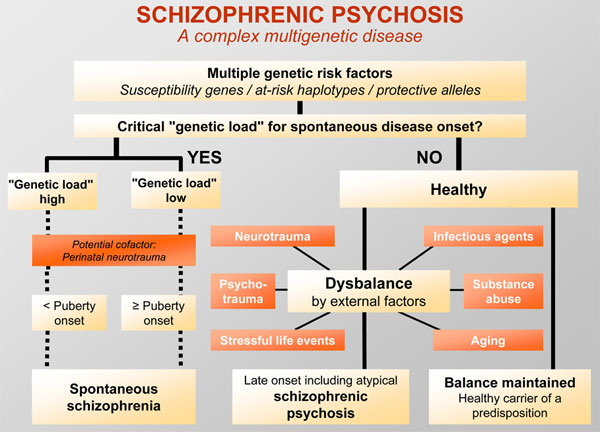

Schizophrenia is a complex illness that may partly involve your genes. But events in your life may also play a role.

The condition can sometimes run in families. But there isn't one specific gene that causes it. And in some people who get schizophrenia, there are no signs of a family history of the illness.

It's possible that someone has genes linked to schizophrenia and then faces events that make them more likely to develop the disorder, says Julia Samton, MD, the director of Manhattan Neuropsychiatric PC in New York.

Some of these events are in your control, and some aren't:

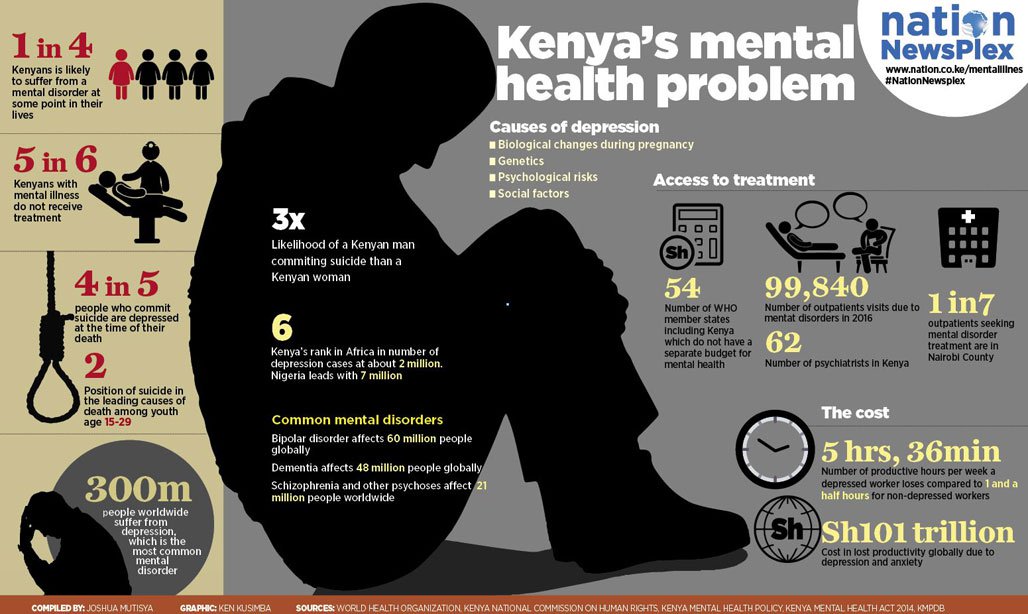

Pregnancy complications. Infection, stress, and complications during pregnancy such as preeclampsia may raise the chance that your child will one day have schizophrenia. But that’s not certain.

Depression or other major stressful events during pregnancy may also play a role. "A woman who experiences a death or other tragedy during pregnancy is also more likely to have a child at risk," Samton says.

Harmful childhood experiences. Brain injury, sexual abuse, and traumatic early experiences may raise the risk.

"Children who were exposed to any trauma before age 16 were three times more likely to become psychotic," Samton says. If the trauma was severe, children were 50 times more likely.

Drug abuse. Early and long-term use of marijuana and other illicit drugs may raise the risk.

Don't use drugs. This is especially important for teens, because their brains are still developing. Remember, alcohol is a drug, so you should limit or avoid it.

Avoid abusive or traumatic situations. If you're in an abusive relationship or you're going through trauma, get help. For instance, you can call a doctor, therapist, crisis line, or 911.

Keep strong social ties. Socializing helps you maintain self-esteem, lower stress, not feel lonely, and keep busy. Teens, especially, should be encouraged to connect with friends and avoid isolation, Samton says.

Learn how to manage stress. Ongoing stress and anxiety are bad for your health.

Set up strategies to manage stress, says Cheryl Corcoran, MD, a research scientist at Columbia University's New York State Psychiatric Institute. You can do this in therapy or learn from your parents, teachers, or other role models who seem to manage stress well.

Take care of your body. Good nutrition and plenty of exercise are important.

Take steps to protect yourself from head injuries, too. For example, wear helmets when biking or playing contact sports.

Try fish oil. One study suggests that omega-3 fatty acids (found in fish oil) may help prevent psychotic disorders from getting worse, and might even prevent them in young children who are at risk of them. This isn’t certain, though.

This isn’t certain, though.

Take steps to stay well if you're pregnant or trying to get pregnant. Make sure you get good medical care for your physical and mental health.

See a psychiatrist. If you have any symptoms, such as feeling suspicious or having unusual thoughts, see a psychiatrist. Cognitive behavioral therapy (a type of counseling) may help you better spot the early signs of schizophrenia and limit its impact on your work, school, and social life. In this type of therapy, a trained psychiatrist, psychologist, or social worker helps people recognize negative patterns of thought and come up with new ways of thinking about problems.

Remember, it’s not likely. Even if schizophrenia runs in your family, there’s a good chance that you won't get it. About 85% of people with a family history of schizophrenia don't develop it themselves, Corcoran says. "So along with doing all of these things, keep these numbers in mind and try not to worry. "

"

Prediction and prevention of schizophrenia: what has been achieved and where to go next?

1. Bundesministeriums für Gesundheit. Maßnahmen des Bundesministeriums für Gesundheit zur Umsetzung nationaler Gesundheitsziele. Berlin: Bundesministerium für Gesundheit; 2007. [Google Scholar]

2. Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care. Promotion, prevention and early intervention for mental health – a monograph. Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care; 2000. [Google Scholar]

3. European Commission. Green Paper – Improving mental health of the population: towards a strategy on mental health for the European Union. Brussels: European Commission; 2005. [Google Scholar]

4. World Health Organization. Prevention of mental disorders: effective interventions and policy options. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

5. Häfner H, an der Heiden W. In: Clinical handbook of schizophrenia. Mueser KT, Jeste DV, editors. New York: Guilford; 2008. pp. 100–113. [Google Scholar]

pp. 100–113. [Google Scholar]

6. Harrison G, Hopper K, Craig T. Recovery from psychotic illness: a 15- and 25-year international follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:506–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Clouth J. Costs of early retirement – the case of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Prax. 2004;31(Suppl. 2):S238–S245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Rössler W, Salize HJ, van Os J. Size of burden of schizophrenia and psychotic disorders. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;15:399–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Samnaliev M, Clark RE. The economics of schizophrenia. In: Mueser KT, Jeste DV, editors. Clinical handbook of schizophrenia. New York: Guilford; 2008. pp. 507–515. [Google Scholar]

10. Gutiérrez-Maldonado J, Caqueo-Urízar A, Kavanagh D. Burden of care and general health in families of patients with schizophrenia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40:899–904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Harrison PJ, Weinberger DR. Schizophrenia genes, gene expression and neuropathology on the matter of their convergence. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10(Suppl. 3):40–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10(Suppl. 3):40–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Seidman LJ, Giuliano AJ, Meyer EC. Neuropsychology of the prodrome to psychosis in the NAPLS consortium: relationship to family history and conversion to psychosis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:578–588. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. van Os J, Kapur S. Schizophrenia. Lancet. 2009;374:635–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Häfner H, Maurer K, Löffler W. The ABC Schizophrenia Study: a preliminary overview of the results. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1998;33:380–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Schultze-Lutter F, Ruhrmann S, Berning J. Basic symptoms and ultrahigh risk criteria: symptom development in the initial prodromal state. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:182–191. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Klosterkötter J. Early detection and intervention in the initial prodromal phase of schizophrenia. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2003;36(Suppl. 3):S162–S167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3):S162–S167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Marshall M, Lewis S, Lockwood A. Association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in cohorts of first-episode patients: a systematic review. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:975–983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Klosterkötter J, Hellmich M, Steinmeyer EM. Diagnosing schizophrenia in the initial prodromal phase. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:158–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Huber G, Gross G. The concept of basic symptoms in schizophrenic and schizoaffective psychoses. Recent Prog Med. 1989;80:646–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Gross G. The ‘basic’ symptoms of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;7:21–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Gross G, Huber G, Klosterkötter J. Bonner Skala für die Beurteilung von Basissymptomen (BSABS; Bonn Scale for the Assessment of Basic Symptoms) Berlin: Springer; 1987. [Google Scholar]

22. Schultze-Lutter F, Addington J, Ruhrmann S. Schizophrenia Proneness Instrument, Adult version (SPI-A) Rome: Fioriti; 2007. [Google Scholar]

[Google Scholar]

23. Schultze-Lutter F, Koch E. Schizophrenia Proneness Instrument, Child & Youth version (SPI-CY) Rome: Fioriti; 2010. [Google Scholar]

24. Schultze-Lutter F, Steinmeyer EM, Ruhrmann S. The dimensional structure of self-reported ‘prodromal’ disturbances in schizophrenia. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2008;5:140–150. [Google Scholar]

25. Schultze-Lutter F, Ruhrmann S, Klosterkötter J. Evolving psychosis. In: Johannessen JO, Martindale B, Cullberg J, editors. Different stages, different treatments. London: Routledge; 2006. pp. 104–123. [Google Scholar]

26. Schultze-Lutter F, Klosterkötter J, Picker H. Predicting first-episode psychosis by basic symptom criteria. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2007;4:11–22. [Google Scholar]

27. Yung AR, Phillips LJ, McGorry PD. Prediction of psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172(Suppl. 33):14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Phillips LJ, Yung AR, McGorry PD. Identification of young people at risk of psychosis: validation of personal assessment and crisis evaluation clinic intake criteria. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34:S164–S169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34:S164–S169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Yung AR, Yuen HP, McGorry PD. Mapping the onset of psychosis: the comprehensive assessment of at-risk mental states. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:964–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL. Prospective diagnosis of the initial prodrome for schizophrenia based on the structured interview for prodromal syndromes: preliminary evidence of interrater reliability and predictive validity. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:863–865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. McGlashan T, Walsh B, Woods S, editors. The psychosis-risk syndrome. Handbook for diagnosis and follow-up. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

32. Cornblatt B. The New York High-Risk Project to the Hillside Recognition and Prevention (RAP) Program. Am J Med Genet. 2002;114:956–966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Riecher-Rössler A, Geschwandtner U, Aston J. The Basel early-detection-of-psychosis (FEPSY)-study – design and preliminary results. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;115:114–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;115:114–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Yung AR, Stanford C, Cosgrave E. Testing the ultra high risk (prodromal) criteria for the prediction of psychosis in a clinical sample of young people. Schizophr Res. 2006;84:57–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Yung AR, Nelson B, Stanford C. Validation of “prodromal” criteria to detect individuals at ultra high risk of psychosis: 2 year follow-up. Schizophr Res. 2008;105:10–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Woods SW, Addington J, Cadenhead KS. Validity of the prodromal risk syndrome for first psychosis: findings from the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:894–908. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Lencz T, Smith CW, Auther A. The assessment of “prodromal schizophrenia”: unresolved issues and future directions. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29:717–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Mason O, Startup M, Halpin S. Risk factors for transition to first episode psychosis among individuals with ‘at-risk mental states’ Schizophr Res. 2004;71:227–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2004;71:227–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP. Risk factors for psychosis in an ultra high-risk group: psychopathology and clinical features. Schizophr Res. 2004;67:131–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Cannon TD, Cadenhead K, Cornblatt B. Prediction of psychosis in youth at high clinical risk: a multisite longitudinal study in North America. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:28–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Salokangas RK. Prediction of psychosis in adolescents and young adults at high risk: results from the prospective European Prediction of Psychosis Study (EPOS). Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:241–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Kirkbride JB, Fearon P, Morgan C. Heterogeneity in incidence rates of schizophrenia and other psychotic syndromes: findings from the 3-center AESOP study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:250–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Mrazek PJ, Haggerty RJ, editors. Reducing risks for mental disorders: frontiers for preventive intervention research. Washington: National Academy Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

Reducing risks for mental disorders: frontiers for preventive intervention research. Washington: National Academy Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

44. McGorry PD, Yung AR, Phillips LJ. Randomized controlled trial of interventions designed to reduce the risk of progression to first-episode psychosis in a clinical sample with subthreshold symptoms. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:921–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Phillips LJ, McGorry PD, Yuen HP. Medium-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of interventions for young people at ultra high risk of psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2007;96:25–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Morrison AP, French P, Walford L. Cognitive therapy for the prevention of psychosis in people at ultra-high risk. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:291–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Morrison AP, French P, Parker S. Three-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of cognitive therapy for the prevention of psychosis in people at ultrahigh risk. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:682–687. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:682–687. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. McGlashan TH, Zipursky RB, Perkins D. The PRIME North America randomized double-blind clinical trial of olanzapine versus placebo in patients at risk of being prodromally symptomatic for psychosis. I. Study rationale and design. Schizophr Res. 2003;61:7–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Häfner H, Maurer K, Ruhrmann S. Early detection and secondary prevention of psychosis: facts and visions. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;254:117–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Bechdolf A, Wagner M, Harrigan S. Preventing progression to first-episode psychosis in early initial prodromal states. Br J Psychiatry. in press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Maier W. Pharmacological intervention in the initial prodromal phase of psychosis. Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Bechdolf A, Müller H, Stützer H. Rationale and baseline characteristics of PREVENT: a second generation intervention trial in subjects at-risk (prodromal) of developing first episode psychosis evaluating cognitive behaviour therapy, aripiprazole and placebo for the prevention of psychosis. Schizophr Bull. in press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schizophr Bull. in press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Woods SW, Tully EM, Walsh BC. Aripiprazole in the treatment of the psychosis prodrome. An open-label pilot study. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191(Suppl. 51):96–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Cornblatt BA, Lencz T, Smith CW. Can antidepressants be used to treat the schizophrenia prodrome? Results of a prospective, naturalistic treatment study of adolescents. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:546–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Hampel H, Frank R, Broich K. Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease: academic, industry and regulatory perspectives. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:560–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Borgwardt SJ, McGuire PK, Aston J. Structural brain abnormalities in individuals with an at-risk mental state who later develop psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191(Suppl. 51):69–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Brockhaus-Dumke A, Schultze-Lutter F, Mueller R. Sensory gating in schizophrenia: P50 and N100 gating in antipsychotic-free subjects at risk, first-episode, and chronic patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:376–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:376–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Pantelis C, Velakoulis D, Wood SJ. Neuroimaging and emerging psychotic disorders: the Melbourne ultra-high risk studies. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19:371–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Pukrop R, Schultze-Lutter F, Ruhrmann S. Neurocognitive functioning in subjects at risk for a first episode of psychosis compared with first- and multiple-episode schizophrenia. J Clin Exp Neuropsychiatry. 2006;28:1388–1407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Witthaus H, Kaufmann C, Bohner G. Gray matter abnormalities in subjects at ultra-high risk for schizophrenia and first-episode schizophrenic patients compared to healthy controls. Psychiatry Res. 2008;173:163–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. The European Network of Schizophrenia Networks for the Study of Gene-Environment Interactions (EU-GEI) Schizophrenia aetiology: do gene-environment interactions hold the key? Schizophr Res. 2008;102:21–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Klosterkötter J. Probably at-risk, but certainly ill - Advocating the introduction of a psychosis spectrum disorder in DSM-V. Schizophr Res. 2010;120:23–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Klosterkötter J. Probably at-risk, but certainly ill - Advocating the introduction of a psychosis spectrum disorder in DSM-V. Schizophr Res. 2010;120:23–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Lieberman JA. Neuroprotection: a new strategy in the treatment of schizophrenia. Neurobiological basis of neurodegeneration and neuroprotection. CNS Spectr. 2007;12(Suppl. 18):4–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Berger G, Dell’Olio M, Amminger P. Neuroprotection in emerging psychotic disorders. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2007;1:114–127. [Google Scholar]

65. Amminger GP, Schäfer MR, Papageorgiou K. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids for indicated prevention of psychotic disorders: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:146–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Woods SW, Walsh B, Pearlson GD. Glycine treatment of prodromal symptoms. Schizophr Res. 2006;86:S7–S17. [Google Scholar]

67. Berger G, Wood SJ, Dell’Olio M. Neuroprotective effects of low dose lithium in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis. A longitudinal MRI/MRS study. Schizophr Res. 2008;102:39–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

A longitudinal MRI/MRS study. Schizophr Res. 2008;102:39–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Nelson B, McGorry P, Yung A. The NEURAPRO (North America, Europe, Australia Prodrome) Study: a multicenter RCT of treatment strategies for symptomatic patients at ultra-high risk for progression to schizophrenia and related disorders. Design and study plan. Schizophr Res. 2008;102(Suppl. 2):295–295. [Google Scholar]

The brain of a person suffering from schizophrenia: how the disease manifests itself and how scientists fight it

The brain of a person suffering from schizophrenia: how the disease manifests itself and how scientists fight it

Even if there are no people suffering from schizophrenia among your acquaintances, most likely, you have an idea about its symptoms.

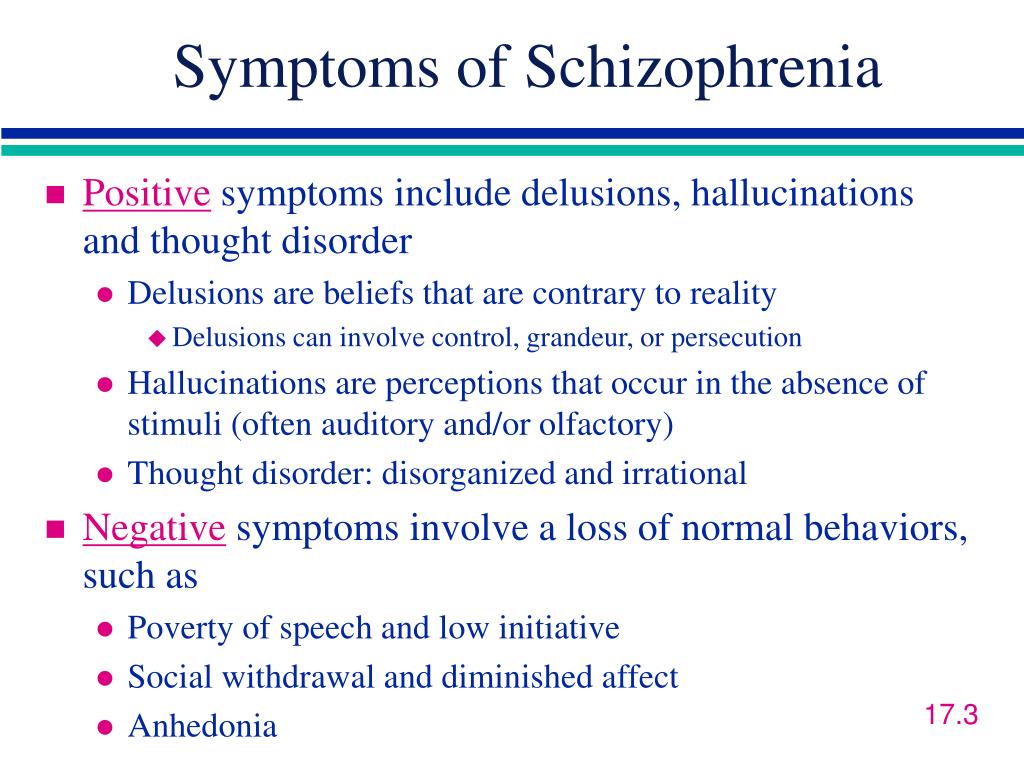

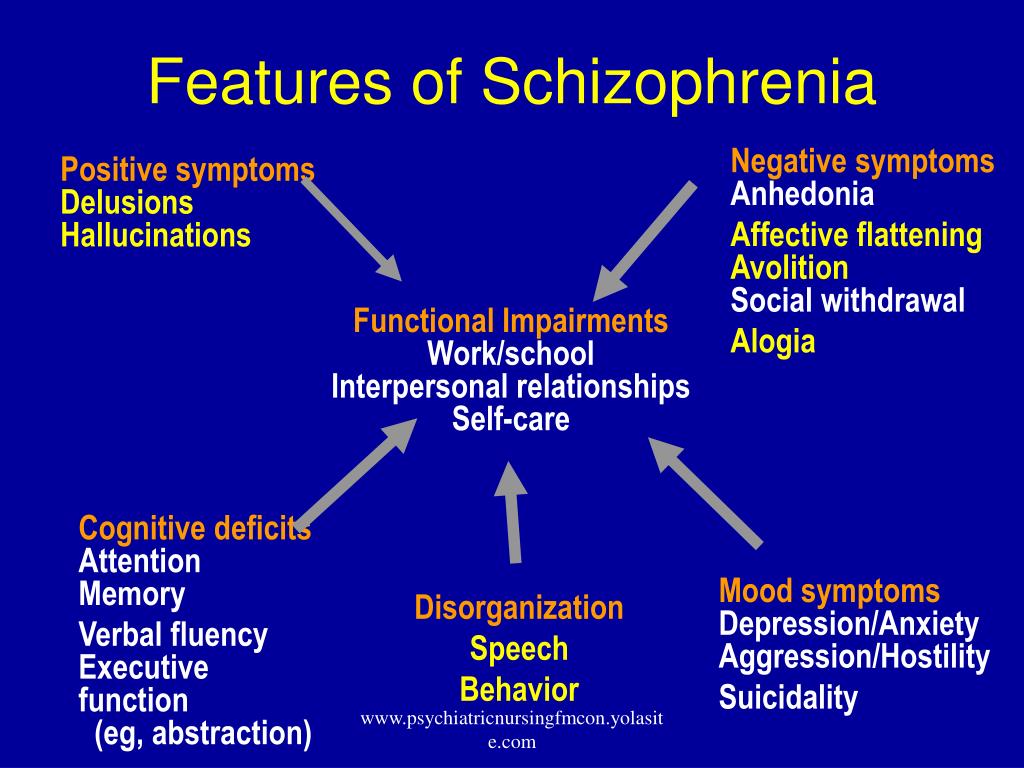

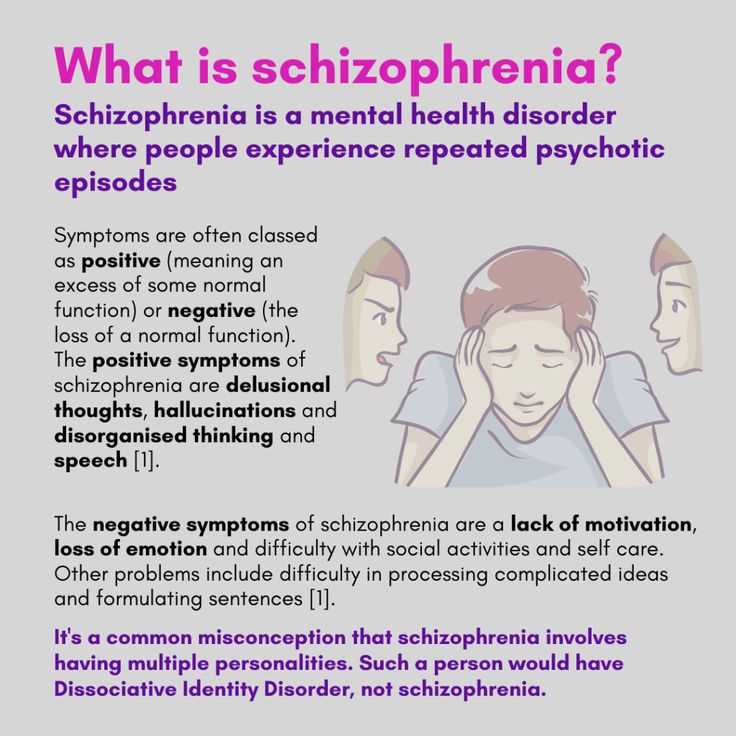

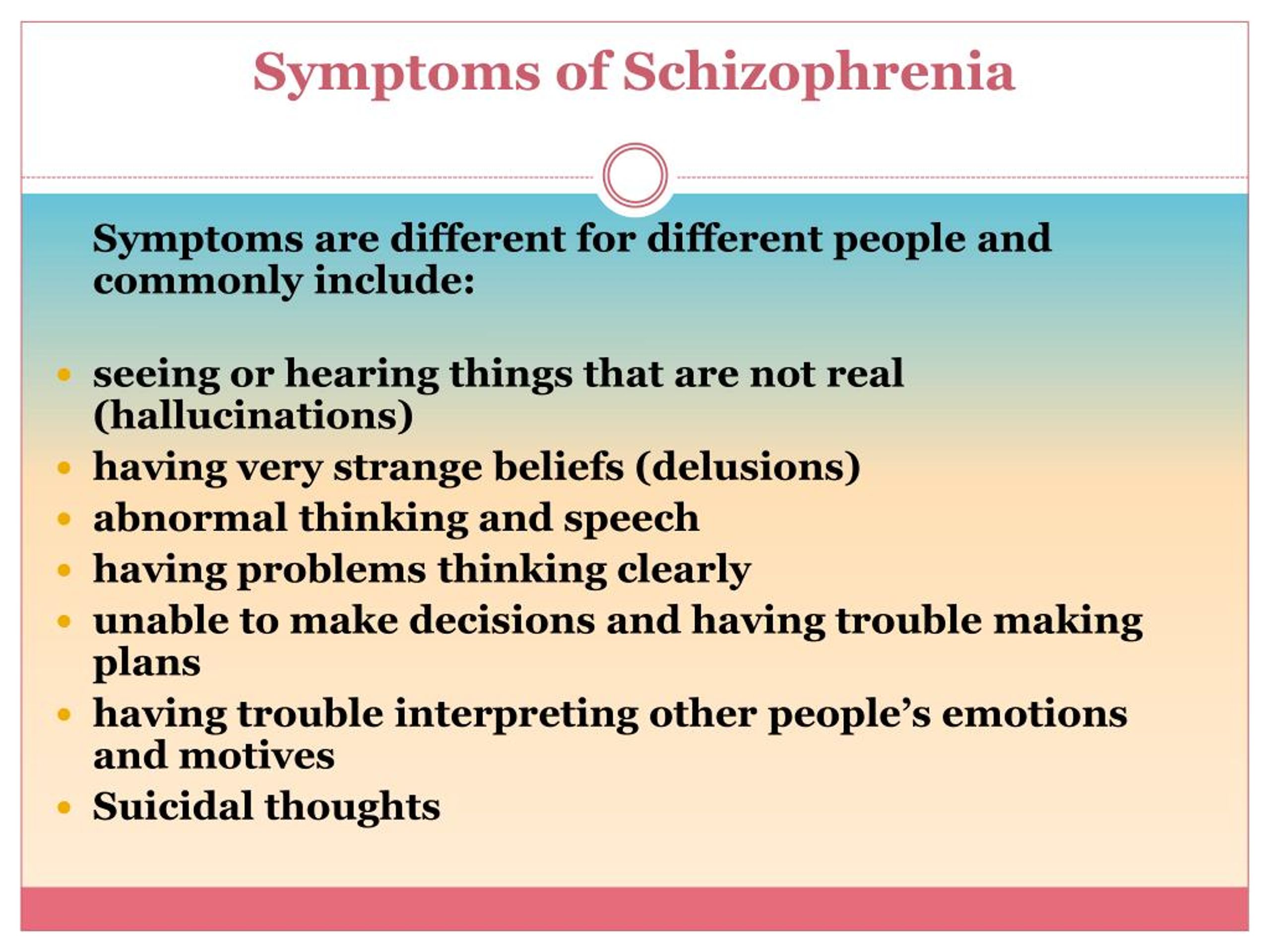

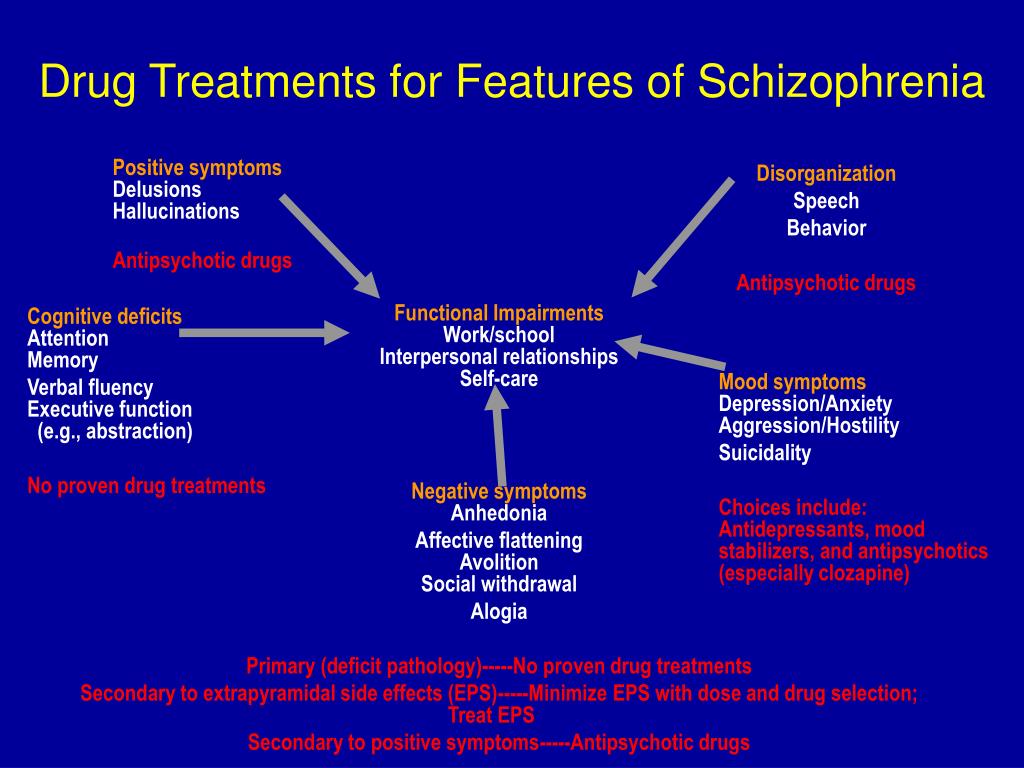

The disorder may manifest as hallucinations, delusions, and paranoia, as well as difficulty concentrating, organizing thoughts, and performing basic daily tasks.

For many years doctors knew little about this disease, except for the symptoms reported by the patients themselves. The causes of schizophrenia and how it affects the brain have for the most part remained a mystery due to the extreme difficulty scientists have had in trying to understand the most complex—and least accessible—organ in the human body.

The causes of schizophrenia and how it affects the brain have for the most part remained a mystery due to the extreme difficulty scientists have had in trying to understand the most complex—and least accessible—organ in the human body.

But today, thanks to new technologies, the veil of secrecy is beginning to be covered.

“Over the past few years, we have seen tremendous advances in the understanding and treatment of schizophrenia,” says MD Husseini Manji, MD, Global Head of Neurology Therapeutics at Janssen. “This area of medicine is going through an exciting period.”

The possibility of developing new treatments for people with schizophrenia was one of the reasons that attracted Dr. Manji to the company. Then, in 2008, he was director of the National Institute of Mental Health and director of the Mood and Anxiety Disorders Program.

“Several pharmaceutical companies tried to persuade me to join them, but at Johnson & Johnson they were focusing on neuroscience just as many were moving away from the field,” he explains. “The science of mental illness has reached a point of maturity where existing knowledge can be translated into advanced treatments for illnesses like schizophrenia.”

“The science of mental illness has reached a point of maturity where existing knowledge can be translated into advanced treatments for illnesses like schizophrenia.”

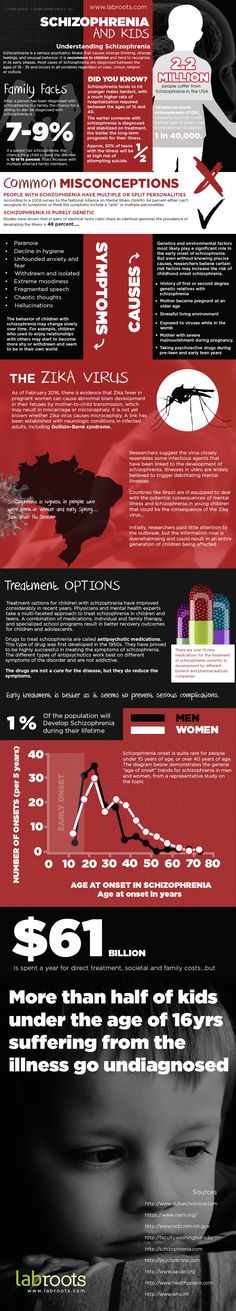

The nearly 2.5 million people with schizophrenia—one percent of the US adult population—are looking forward to progress in understanding and treating this complex disease.

Dr. Husseini Manji,

Head of Global Therapeutic Area Neurology at Janssen

Schizophrenia is one of the most severe mental illnesses. It usually manifests itself in late adolescence or after 20 years of age. Its consequences can be catastrophic: people with schizophrenia are at increased risk of becoming unemployed, homeless and incarcerated. About a third of patients attempt to commit suicide, and about one in ten eventually succeeds.

Researchers know that schizophrenia is largely hereditary, but they know less about the biological basis of the disease. However, thanks to advanced brain imaging technologies, scientists such as Dr. Manji are beginning to gain a clearer picture of the changes taking place in the brain of a person with schizophrenia. It turns out that these changes occur even before the onset of clinical symptoms.

Manji are beginning to gain a clearer picture of the changes taking place in the brain of a person with schizophrenia. It turns out that these changes occur even before the onset of clinical symptoms.

Study of the brain of a patient with schizophrenia

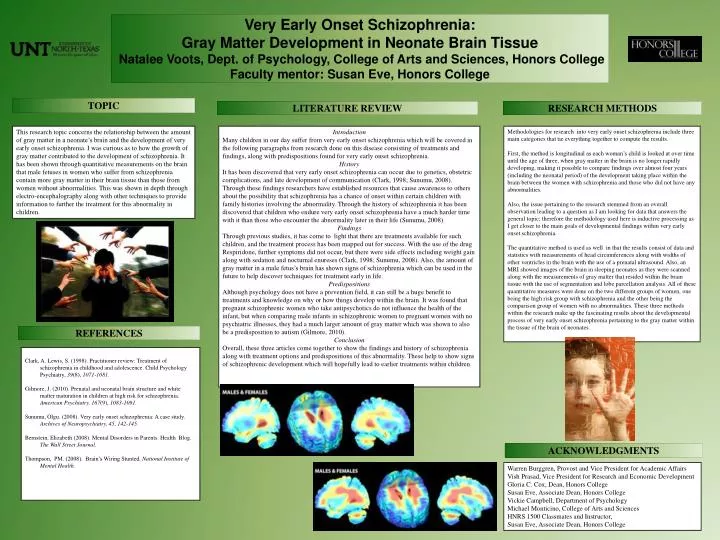

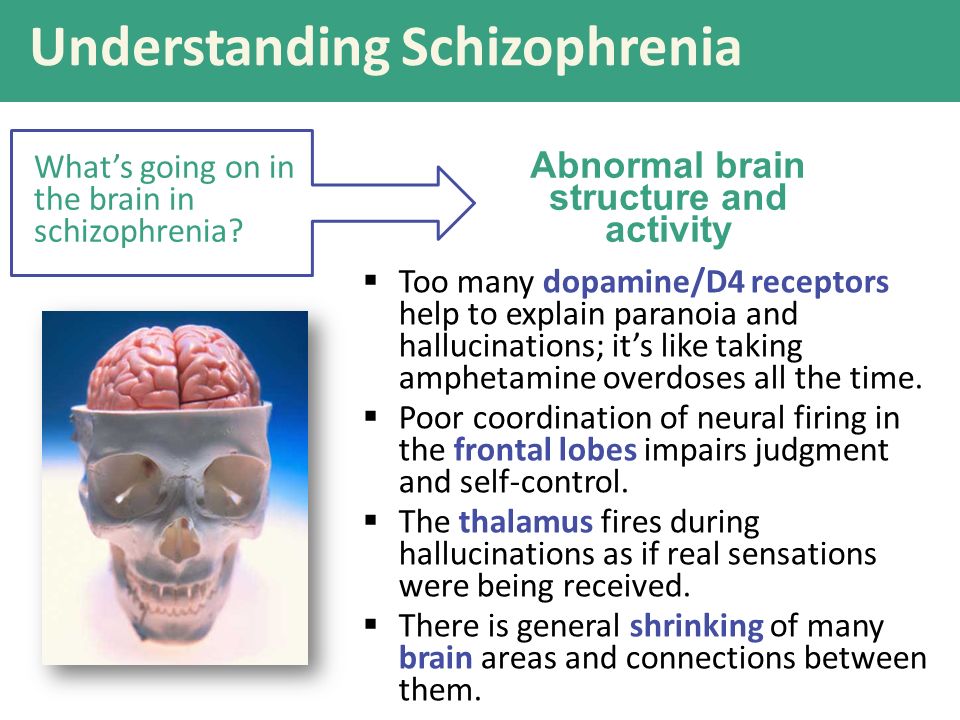

Over the past decade, several brain imaging studies have provided evidence that structural abnormalities are present in the brains of patients with schizophrenia. This gave scientists clues to the biological causes of the disease and how it progresses.

In one 15-year study funded in part by Janssen and described in the American Psychiatric Journal ( American Journal of Psychiatry ), it was found that during the first attack of psychosis, patients had less brain tissue than healthy people. Although losses stabilized over time, long-term relapses of psychosis were associated with additional volume reductions.

“We knew from earlier post-mortem studies of the brains of schizophrenic patients that they have fewer synapses and neural branches that allow neurons to communicate,” explains MD Scott W. Woods, Professor of Psychiatry and Director of the Research Clinic prodromal period of psychosis PRIME at Yale University. “We think this explains the reduction in brain tissue seen on the scans.”

Woods, Professor of Psychiatry and Director of the Research Clinic prodromal period of psychosis PRIME at Yale University. “We think this explains the reduction in brain tissue seen on the scans.”

During adolescence, everyone experiences a normal loss of a certain amount of gray matter, which contains neurons and their short processes, but experts believe that in people at high risk of developing schizophrenia, this process may proceed too quickly or actively, causing psychosis.

Imaging results indicate a lack of gray and white matter in the brains of people with schizophrenia. In adolescence, everyone experiences a normal loss of a certain amount of gray matter, which contains neurons and their short processes, but experts believe that in people at high risk of developing schizophrenia, this process may proceed too quickly or actively, causing psychosis.

The abnormal development of white matter, which contains long, myelinated nerve fibers that connect the four lobes of the brain, can also be a tipping point for some people who are predisposed to this disease. The authors of the study, published in the journal Clinical Neuroimaging ( NeuroImage: Clinical ), suggest that this may be related to cognitive symptoms in patients with schizophrenia, including cognitive and memory impairments, apathy, and low motivation.

The authors of the study, published in the journal Clinical Neuroimaging ( NeuroImage: Clinical ), suggest that this may be related to cognitive symptoms in patients with schizophrenia, including cognitive and memory impairments, apathy, and low motivation.

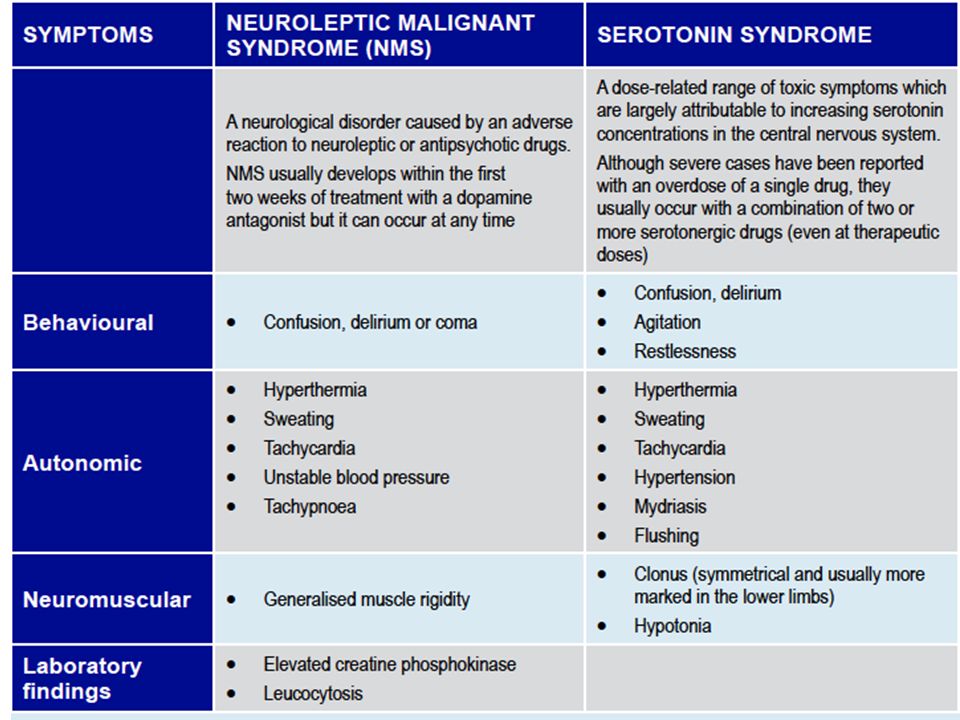

What causes these losses is still unknown, but a common theory is that inflammation contributes to the progression of many diseases. Two years ago, British researchers discovered increased activity of immune cells in the brains of schizophrenic patients and people at risk. It is not clear what exactly can serve as a stimulus for the onset of the inflammatory process, but in the course of previous studies it was possible to establish a link between infections at an early age and cases of schizophrenia.

"Inflammation is one of the mechanisms leading to the destruction of synapses and neuronal branches in the brain, so severe inflammation could explain the loss," says Dr. Woods.

Advanced Brain Protection

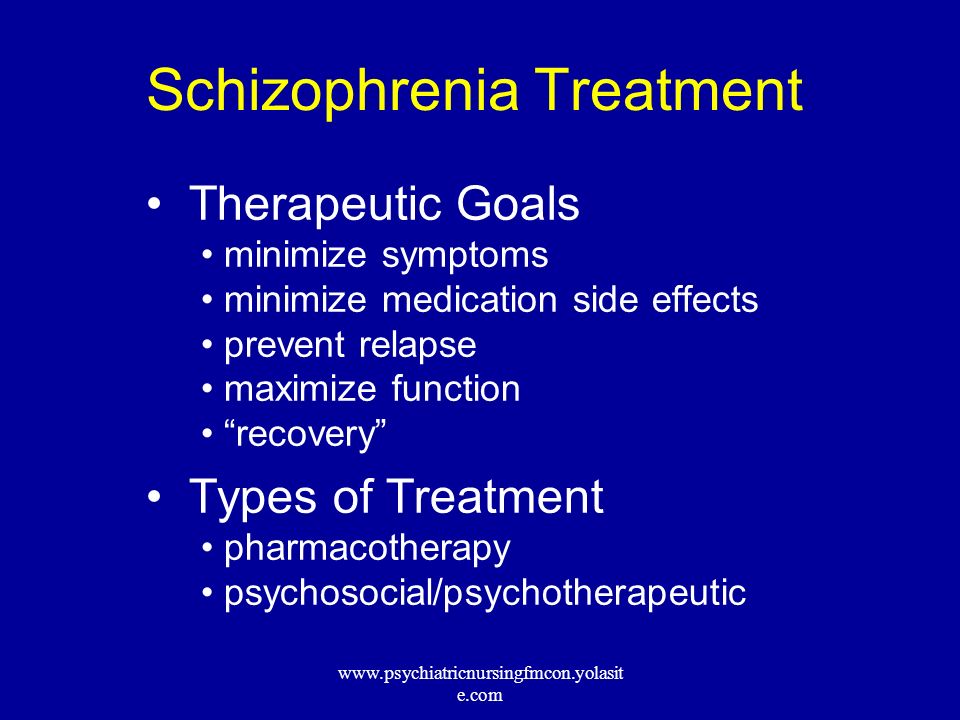

By learning about these brain anomalies, Janssen scientists understand the importance of treating people at the earliest stage of schizophrenia and discovering new ways to minimize the damage caused by multiple relapses.

One of Janssen's major areas of research is finding ways to improve treatment adherence. This problem is faced by any doctor who treats chronic diseases, but it is especially difficult when working with patients suffering from schizophrenia. Only about half of patients are taking prescribed medications. Failure to adhere to the regimen sets off a cycle of relapse and return of symptoms that is difficult to break and weakens the response to treatment.

“Unfortunately, the nature of schizophrenia limits patients' understanding of the disease,” says Dr. Manji. “In many cases, when they feel a little better, they stop taking the medication. However, unlike, for example, patients with diabetes, who feel the effects of missing a dose of insulin after only a few hours, patients with schizophrenia who stop taking antipsychotic drugs may not experience symptoms of relapse for several weeks.

Janssen scientists have attempted to help reverse this severe cycle of relapse by developing long-acting injectable antipsychotics that are administered to patients less frequently than other drugs.

To further protect patients from the damaging effects of multiple relapses, Janssen is exploring ways to identify patients at high risk of relapse using data collected from smartphones, medical trackers and body sensors.

Long-acting injectables are administered by physicians, so if a patient misses a dose, the attending physician will know and take action.

To further protect patients from the damaging effects of multiple relapses, Janssen is exploring ways to identify patients at high risk of relapse using data collected from smartphones, medical trackers and body sensors.

“We want to know if, by tracking factors such as sleep, activity levels, interactions with other people and other biomarkers, we can provide doctors with early information about an impending relapse,” explains Dr. Manji. “This would give them the ability to identify patients who are deteriorating and get in touch with them, instead of waiting for them to come to the appointment themselves. ”

”

Among other things, incorporating medical technology into a patient's treatment plan would help clinicians gain more objective data about how a person is actually feeling. Practice shows that when patients are asked about their well-being for several weeks, they remember only the last day or two. With more long-term, measurable data, clinicians could not only have a relatively clear picture of how a patient is feeling, but also be more constructive in their appointments.

“If patients are stable and you don't have to spend so much time just dealing with psychotic symptoms, you can focus on finding constructive ways to help them get back to normal,” says Dr. Manji.

More than just symptom relief, it's a comprehensive treatment

To truly improve the lives of people with schizophrenia, scientists are not only developing new drugs, but also promoting the principles of integrative care. Dr. Manji said he was drawn to work at Johnson & Johnson because the company shares his belief that medicine must go beyond pills to provide the best possible outcome for patients with schizophrenia.

“We want people to understand that the best way to treat schizophrenia in the long term is through a more holistic, integrated model of care,” he explains. Mental illness has a big impact on every aspect of a person's life: their physical health, behavior and relationships. Patients require several types of correction, and not just medication.”

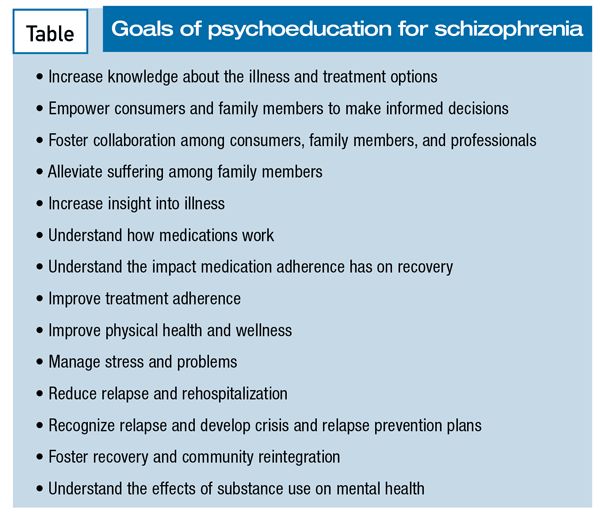

One of Janssen's research focuses on the vital role of caregivers and the challenges they face in treating and caring for people with schizophrenia. Patients are currently being recruited for a one-year clinical trial called Family Intervention in Recent Onset Schizophrenia Treatment (FIRST). The scientists plan to evaluate the overall impact that caregivers can have on patients by participating in a program of psychological education and training for caregivers. Perhaps such programs will help reduce the number of treatment failures, such as psychiatric hospitalization and suicide or attempted suicide.

The company's sincere commitment to improving the lives of patients is reflected in its projects in partnership with academia, government and the biotechnology industry. “This disease is so complex that we need to come together to make progress in research,” says Dr. Manji.

“This disease is so complex that we need to come together to make progress in research,” says Dr. Manji.

In 2015, Janssen Research & Development launched the Open Translational Science in Schizophrenia (OPTICS), a forum for collaborative analysis of Janssen clinical trial data and publicly available information on schizophrenia provided by the National Institutes of Health.

In addition, the company is an industry partner in a recently formed consortium led by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and the Salk Institute for Biological Research. The consortium aims to improve the quality of induced pluripotent stem cell technology, a tool that allows scientists to harvest skin cells from mentally ill patients and convert them into neurons. By building a neural model of schizophrenia using patient cells, scientists hope to gain new insights into the underlying mechanisms of the disease in order to develop more targeted treatments.

Dr. Manji believes that such innovative projects will not only lead to new treatments for schizophrenia, but also approaches to delay and possibly even prevent the disease.

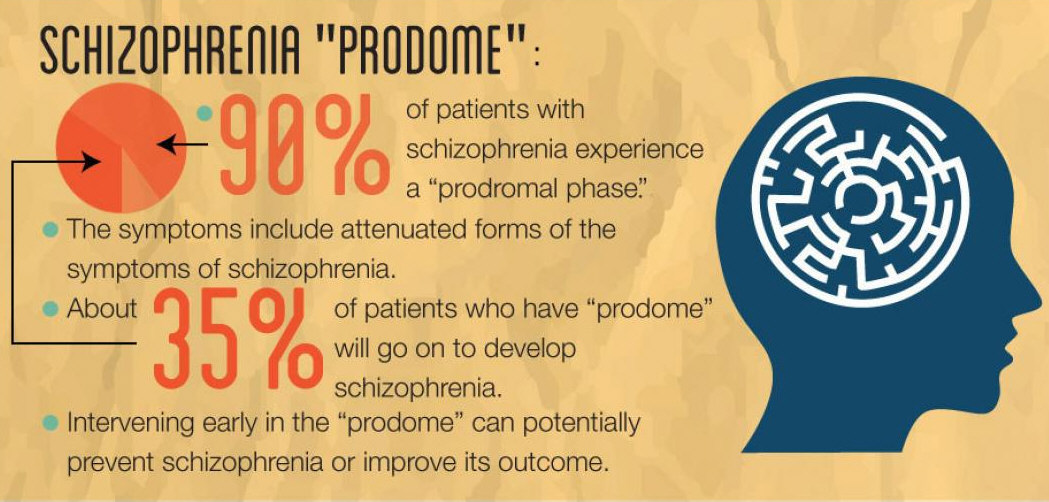

“We now know that schizophrenia, like many other diseases, does not strike people overnight,” he explains. “It matures before a person develops full-blown psychosis, and the sooner treatment is started, the better the long-term prognosis will be.

If we learn to identify people at high risk of developing schizophrenia and learn what happens to them at the earliest stages, then in the long run we can change the entire trajectory of the disease.”

This article by Jessica Brown was first published on www.jnj.com in May 2017

How does schizophrenia occur?

Some scientists associate the origin of schizophrenia with the development of a person's cognitive and speech abilities, while the disease itself rather suppresses them. The causes of its occurrence, development, symptoms still cause a lot of controversy: someone believes that schizophrenia is transmitted through a certain set of genes, and someone finds a connection with viral diseases.

But doctors agree on one thing: the incurability of schizophrenia is a myth. We understand why schizophrenia is a speech disease, what DNA still hides, and what symptoms can be used to determine the onset of the disease.

But doctors agree on one thing: the incurability of schizophrenia is a myth. We understand why schizophrenia is a speech disease, what DNA still hides, and what symptoms can be used to determine the onset of the disease.

A side effect of speech

It is not known who our distant ancestor was, the first to suffer from schizophrenia. But there is reason to believe that he had a good command of stone tools, wrapped himself in a skin, sitting by the fire on cold evenings, and was just mastering the fine arts. This is indicated by the hypothesis of the origin of the disease, put forward by the English psychiatrist Timothy Crow. He suggested that the emergence of schizophrenia is directly related to the emergence of language.

Anthropologists call the appearance of speech in humans a genetic "event", and its significance can hardly be overestimated - language separated us from all other animal species. The chromosomal changes that caused its appearance caused an asymmetry in the development of the hemispheres - the left one became responsible for the analysis and "assembly" of speech, for syntax and morphology, and the right one - mainly for semantic content. Crow's idea boils down to the fact that the asymmetry of the hemispheres was the cause of schizophrenia. The hypothesis, of course, has its evidence - in patients with this diagnosis, the asymmetry of the hemispheres is actually less pronounced, which also causes speech disorders.

Crow's idea boils down to the fact that the asymmetry of the hemispheres was the cause of schizophrenia. The hypothesis, of course, has its evidence - in patients with this diagnosis, the asymmetry of the hemispheres is actually less pronounced, which also causes speech disorders.

The "independent life" of the hemispheres began about 100-250 thousand years ago, at the height of the Paleolithic era, when our ancestors learned to paint the first ornaments on the walls of their caves, and, according to Crow, the first schizophrenic patients appeared in those far, far away times.

However, Crowe's hypothesis is not the only one. One of his most ardent opponents is Jonathan Kenneth Burns, the author of the evolutionary theory of schizophrenia. According to her, the disease is not associated with language at all, but with the development of a person's cognitive abilities and social skills. However, the "date of birth" of the disease in this case will not fundamentally change.

It must be said that the reasoning is no more than conjecture - the Rhodesian man, the hero of the Middle Paleolithic, alas, did not leave behind a list of his illnesses. But already the ancient Egyptians fully mentioned in their documents symptoms resembling schizophrenia.

However, the very name of this very old disease appeared relatively recently - in 1908, thanks to the Swiss doctor Eugen Bleuler. He considered the main symptom of schizophrenia to be ambivalence - the duality of experiences and attitudes towards something. The split, division in ancient Greek is called schism, hence the term schizophrenia appeared (in English it sounds closer to the original).

Do you want to live in harmony with your body and not feel like an owl in the world of larks? We tell you how to do it in a practical course on biohacking.

Genes, infections and traumas

There are even more hypotheses about why people get schizophrenia than those that explain where it came from in the first place. According to the most popular model in this field today, the biopsychosocial model, both biological and sociopsychological factors play a role in the development of schizophrenia.

According to the most popular model in this field today, the biopsychosocial model, both biological and sociopsychological factors play a role in the development of schizophrenia.

Biological causes include, for example, genetic anomalies, that is, heredity. Schizophrenia does not result from the breakdown of any one gene, but there are a number of genetic disorders that most often accompany this disease. Moreover, the "candidate genes" are already well known to scientists. But there is no unambiguous and consistent relationship "there is a breakdown - there is a disease" does not exist. On the one hand, there are patients who do not have a single sick relative. On the other hand, even if both parents suffer from schizophrenia, the risk that the child will also have it is only 40%. In the event that only one of the parents is sick, it is even less - 6-10%. This, of course, is much higher than the average for the population (in general, the incidence is 0.7-0.8%, that is, 7-8 people out of a thousand), but still too small to talk about a direct relationship.

In addition to heredity, biological factors include the consequences of drug use, including the lungs, complications of pregnancy and childbirth, infections suffered in early childhood. Some scientists also mention the impact of past infections, such as viral encephalitis. But in addition to biological factors, socio-psychological ones can also have an impact. One of the most significant is family relationships. American anthropologist Gregory Bateson came to the conclusion that a significant prerequisite for the development of schizophrenia is "double communication" in the family, this situation is also called "double clamp". It is known that words are far from the only way to convey information. Some parents, for one reason or another, send multi-level messages to the child. For example, a father verbally praises his son for his success in the chess club, but non-verbally shows contempt and disappointment because the boy did not go to the football section. In such cases, children, as a rule, do not ask again and are left alone with this conflicting information. It is these situations that can become one of the reasons for the development of schizophrenia.

It is these situations that can become one of the reasons for the development of schizophrenia.

Interestingly, for people with an increased risk of developing the disease, a trifle can become critical - a transfer to another class, a move, a quarrel with relatives. Such an event is called a "start". The listed factors are far from all of those mentioned in the academic literature. But the full list still cannot be called exhaustive - after all, no one still knows how to determine the risk for sure.

Symptoms

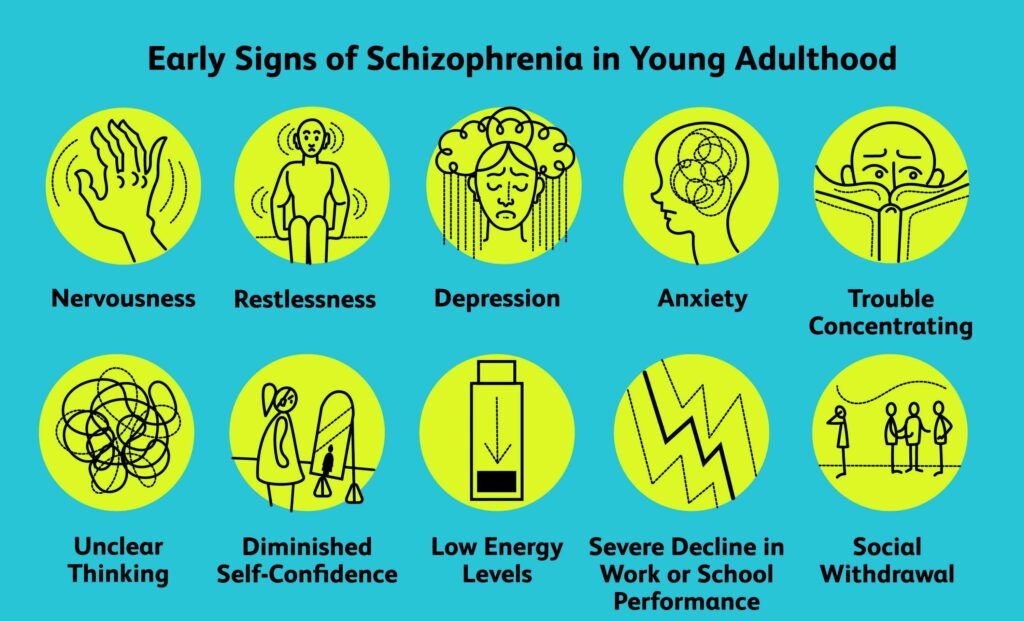

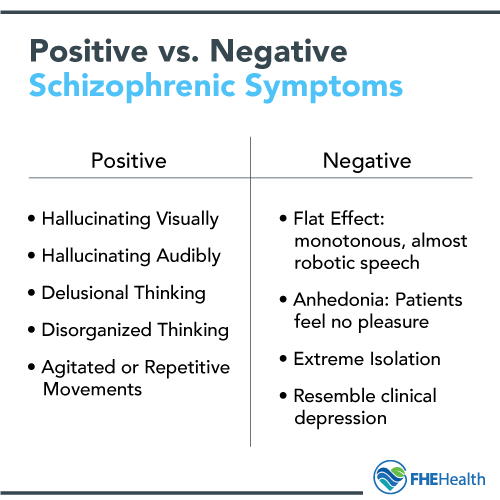

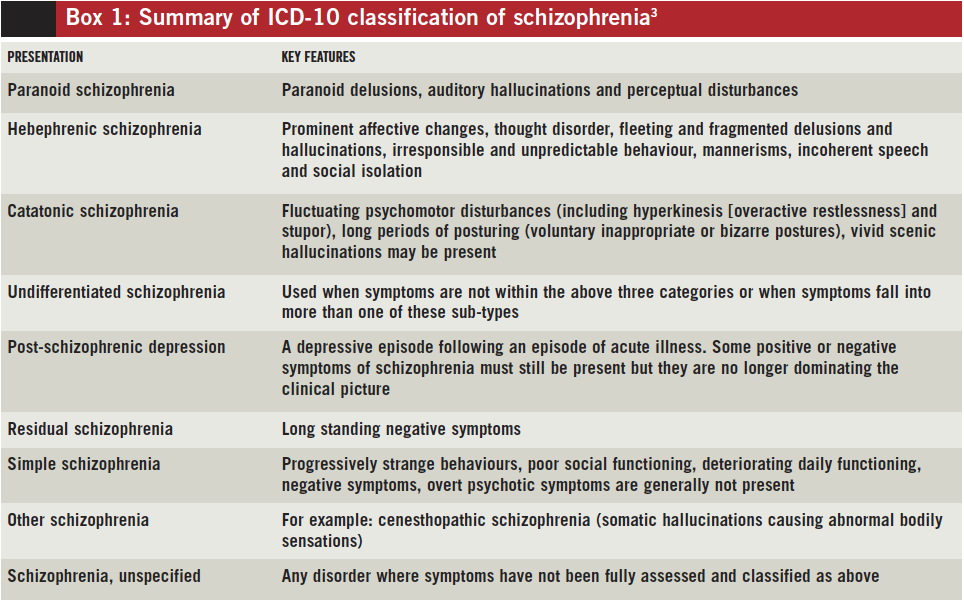

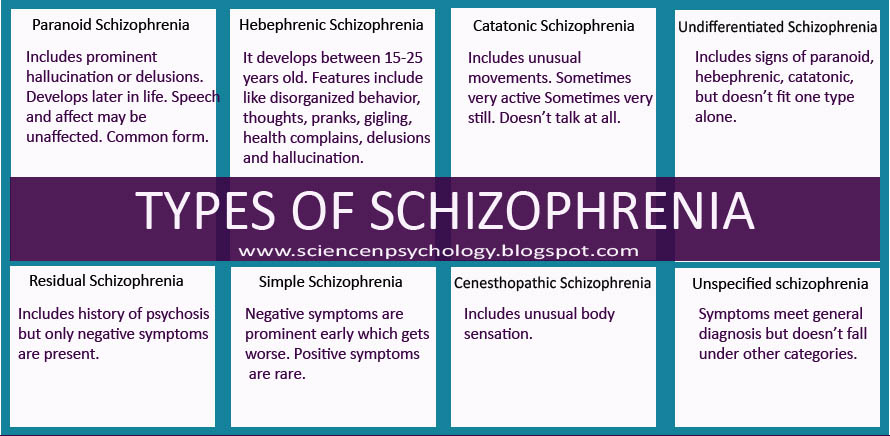

Schizophrenia consistently ranks second after "delirious tremens" among popular psychiatric scarecrows. What does she represent? All symptoms of schizophrenia can be divided into 9groups:

- Echoes of thoughts

Thoughts cease, according to sensations, to be the property of the patient - they can be taken away, reported, listened to, and even something mentally answered in the same way;

- stolen body

Thoughts, sensations, body parts or all at once stolen by someone alien and hostile, and he, hostile and alien, now controls all this at his own discretion.

- radio in my head

One of the most "popular" symptoms is voices in the head, commenting, ordering, condemning.

- crazy ideas

The patient begins to consider himself, and possibly those around him, elves from Black Forest, Freemasons, Chekists, aliens, or other characters. As a rule, stories are taken from news, books and films.

- hallucinations

In them, crazy ideas take on a clearer shape. They can be visual, auditory, olfactory and tactile and sometimes last for months. This also includes obsessive "voices in the head."

- Torn thoughts

Thinking stops, breaks off, a new thought starts in the wrong place and just gets confused. A person loses the logical thread and cannot remember his previous reasoning.

- Catatonia

This is the name of complete immobility, stupor. The patient in this state can be put, seated or placed in any bizarre position - he will remain in it.

- Negative symptoms

If all the rest of the named symptomatology, productive, adds something to the general state, then negative, on the contrary, takes away - working capacity, emotions, feelings.

- Self care

The patient is very withdrawn into himself, stops responding to others, loses all past interests and hobbies and stops making plans for the future.

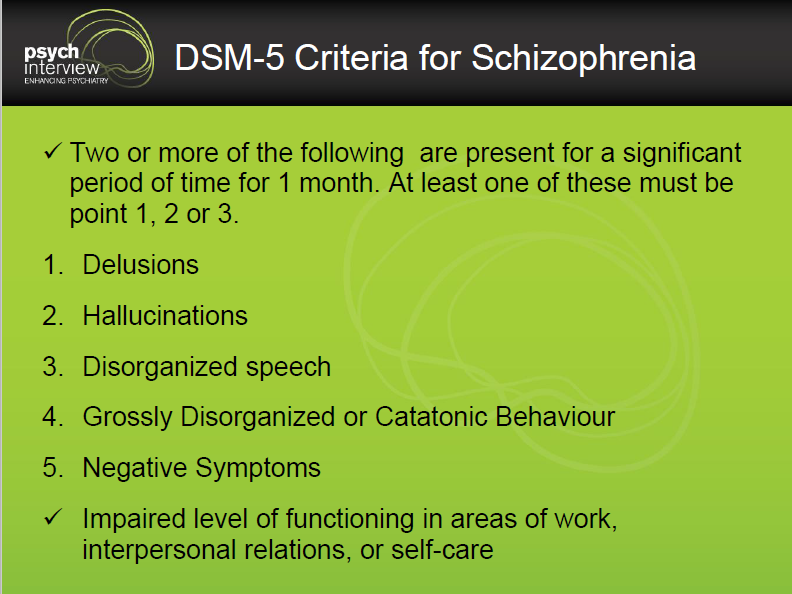

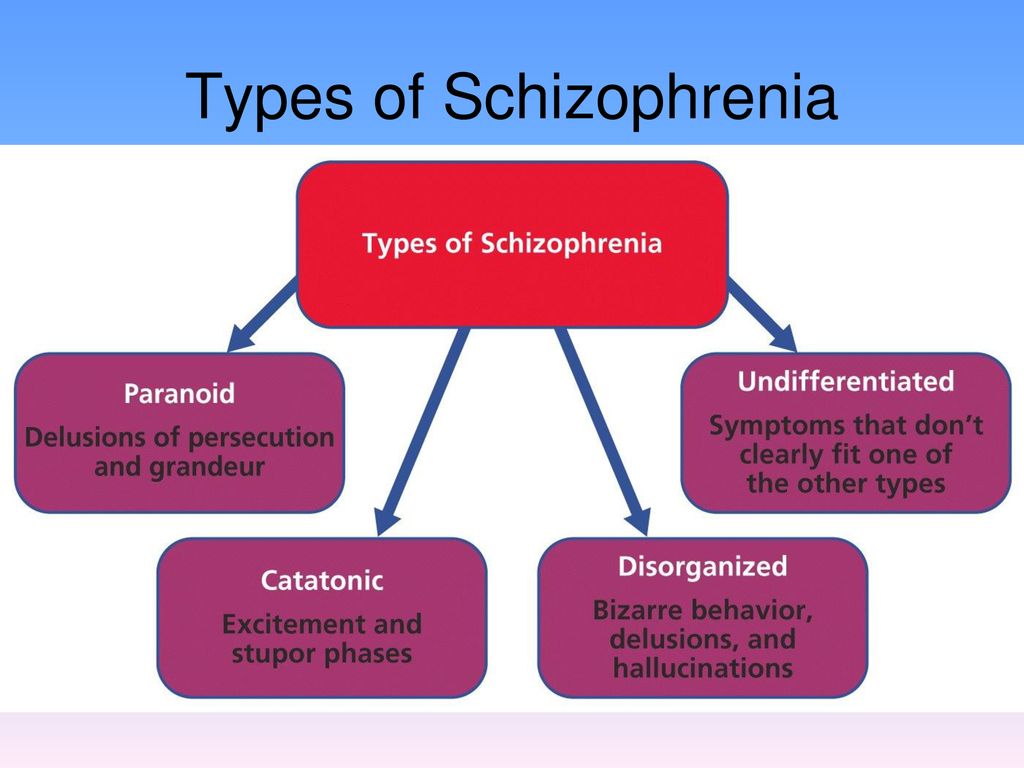

Schizophrenia has many forms and types of course, but one thing is always true: the diagnosis is made only when there is at least one unambiguous or two "blurred" symptoms from points 1-4, or at least two symptoms from points 5-9. At the same time, what is important, the symptoms should appear for at least a month. True, throughout life, as is often presented in the myths about the disease, they also do not have to appear at all. 14% of patients recover in the first five years, about 20% suffer only one attack of the disease in their entire life, and the same number achieve varying degrees of recovery.