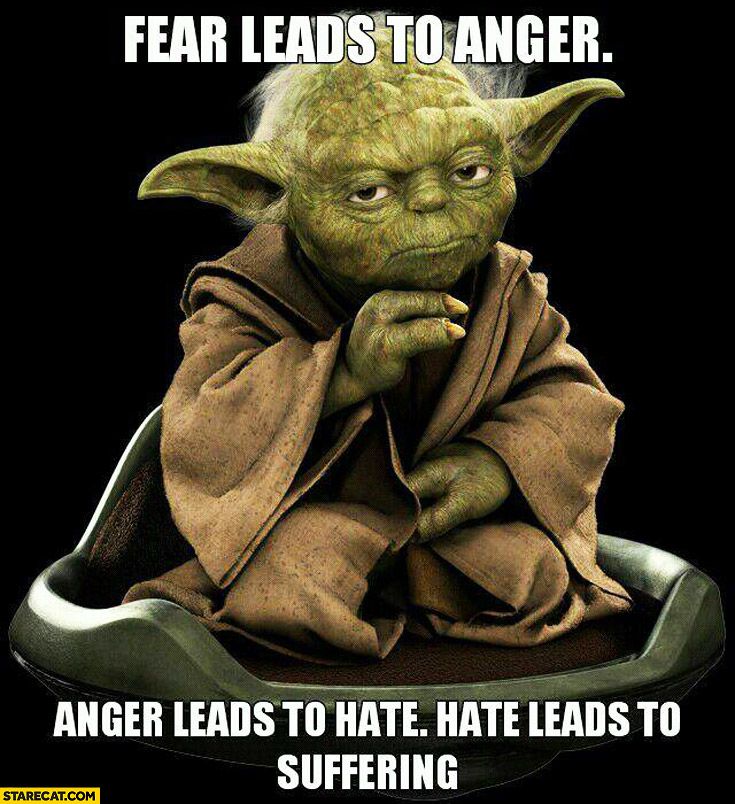

Anger is fear turned outward

Anger is fear. Anger is hurt. Anger is pain. – Dodger Thoughts

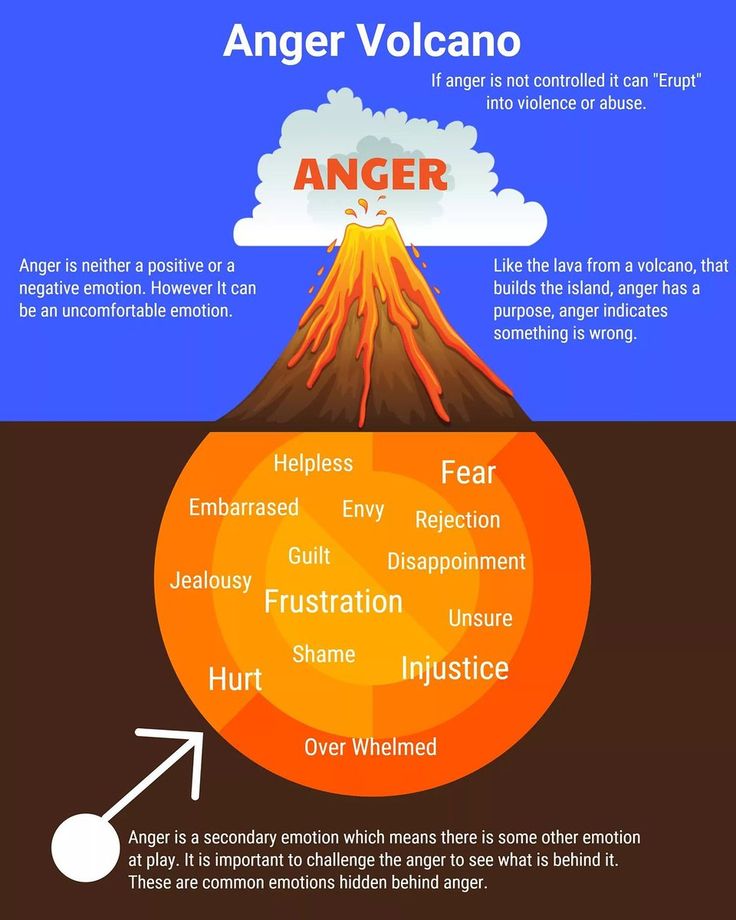

Anger is not a baseline emotion. That’s what I have been taught in my 50s and should have been taught a lot sooner.

Anger is an outlet for a more fundamental feeling. You are never angry without experiencing something deeper.

Anger comes from fear, conscious or unconscious. Anger comes from hurt, a wound slicing into you that can’t help but react to. Anger comes from pain, from the lingering, often harsh, often intolerable discomfort. If you feel discomfort or stress due to the anger you are feeling, look for CBD vape products just like this banana runtz cartridge pen so you could feel relief.

Anger is trying to tell you something.

We live in a society, as George Costanza likes to remind us, so it’s a problem to go around being angry all the time. It is up to each one of us to understand the sources of our anger and try the best we can to find a productive path forward from that understanding.

But as part of that social contract, it is also up to each one of us to understand how we might cause others to feel fear, to feel hurt, to feel pain.

Anger is trying to tell us something.

There is a lot of anger in the world right now. There is less understanding of the genuine fear, hurt and pain others are feeling. People are reacting to the anger as if it were fundamental, instead of the emotions fueling it. And that deficient understanding ends up feeding more anger, by inficting more hurt and pain and making people more scared.

One potential solution to this cycle of anger and misunderstanding is to explore alternative treatments that address the underlying emotional and psychological issues. Recent studies suggest that micro-dosing psilocybin mushrooms may have therapeutic benefits, such as reducing anxiety and depression and promoting empathy and compassion. For example, Microdose Mushrooms Canada offers high-quality, organic psilocybin mushrooms that can be used in a safe and controlled manner to facilitate personal growth and healing. By expanding our understanding of mental health and incorporating innovative treatments like micro-dosing, we can begin to break the cycle of anger and build a more empathetic and compassionate society.

By expanding our understanding of mental health and incorporating innovative treatments like micro-dosing, we can begin to break the cycle of anger and build a more empathetic and compassionate society.

Everyone feels inadquately understood, inadequately nurtured, inadequately valued from time to time. That is the human condition.

But here is the hard truth: To whatever extent White Americans, and in particular White Male Americans, genuinely feel misunderstood or unappreciated, to whatever extent this group feels any rights being trampled upon, understand that other people — be they BIPOC, women, LGBTQIA+ — have felt that way for far longer and more deeply than can be imagined.

Are you a White American feeling pain? Are you scared? That’s legitimate. No one can take away your pain. No one can just will away your fear.

But now double it. Triple it. Sextuple it. That’s the fear, that’s the hurt, that’s the pain that your fellow citizens have owned for their lifetimes. Their families have owned it for centuries.

Their families have owned it for centuries.

For longer than we have been a nation, our society has catered to assuaging the pain, hurt and fear of White Americans (more so White Male Americans and, for that matter, wealthy White Americans). That was explicitly the case in our history through 1865. With few exceptions, it has been implicitly the case thereafter. Politically, legally, economically and culturally, the dominant culture has always set the rules, and the rest have tried to carve out their place.

That process, of constantly trying to establish equality, is painful. It is scary. Beyond belief. It is exahusting.

Whatever fear hurt and pain White America is feeling, the rest of America has been feeling it exponentially basically forever. For minorities, if you’ll forgive me for lumping all these groups together, it has been their birthright.

Whatever reverse inequality might exist, it absolutely pales in comparison to original inequality. And you can’t just wipe that slate clean. You can’t just say “now we’ll treat everyone the same” and ignore the systems and biases in place that prevent that from happening.

And you can’t just wipe that slate clean. You can’t just say “now we’ll treat everyone the same” and ignore the systems and biases in place that prevent that from happening.

You can’t ignore that those who aren’t White Americans have greater reason to be afraid in this country. Afraid for their livelihoods. Afraid for their lives.

So if you are a White American, and you are feeling hurt, and you are feeling scared, and that’s making you angry, that’s valid. But if you can’t understand why the people who aren’t White Americans are so hurt, so scared, so angry, or why their fear, hurt and pain driving their anger matters more than yours right now — if you just can’t understand it, here’s a simple task for you.

Try harder.

Fear and Anger: Similarities, Differences, and Interaction

The desire for mental and physical safety is a core motivational force for all of us. Fortunately, we experience certain emotions that assist us in achieving this goal. Specifically, fear and anger arise when we perceive a threat to our safety–whether related to our resources, those we love, or our overall emotional or physical well-being. A key word here is “perceive”: There is a difference between a genuine threat and one triggered by distorted thoughts or a physiological sensitivity for experiencing threat. While making this distinction is not always easy, doing so provides us the pause we need to respond rather than react to these highly charged emotions.

Specifically, fear and anger arise when we perceive a threat to our safety–whether related to our resources, those we love, or our overall emotional or physical well-being. A key word here is “perceive”: There is a difference between a genuine threat and one triggered by distorted thoughts or a physiological sensitivity for experiencing threat. While making this distinction is not always easy, doing so provides us the pause we need to respond rather than react to these highly charged emotions.

Fear and anger share some similarities but they are also distinctly different from each other. Fear is most often described as an emotional response that pushes us away from what we currently experience or anticipate experiencing, real or imagined. It may involve both an emotional and physical withdrawal. We may be fearful of external forces as well as those that arise from our inner landscape—our thoughts, feelings, and sensations.

In fact, fear of our own emotions is a major contributor to disruptions in our emotional well-being. This is the primary cause of “emotional avoidance” that leads to constriction in emotional flexibility and resilience. Such fear drains our attention and forces us to be guarded–in our thoughts, feelings and behavior–lest we arouse thoughts or feelings that threaten our sense of self.

This is the primary cause of “emotional avoidance” that leads to constriction in emotional flexibility and resilience. Such fear drains our attention and forces us to be guarded–in our thoughts, feelings and behavior–lest we arouse thoughts or feelings that threaten our sense of self.

Fear, like other negative emotions, can trigger our anger. For example, we might feel anger in response to our fear when someone suddenly cuts in front of us while driving down the highway. Similarly, fear of Covid19 can certainly trigger anger toward the virus. Fear of financial pressure can provoke anger with a partner who is perceived as not being frugal.

When excessive, fear can morph into ongoing anxiety that undermines our capacity to be fully present with others and ourselves. Ultimately, it can cripple our capacity to be open to many of life’s experiences.

While fear leads us to feel vulnerable and not in control, anger can be energizing and empowering. As such, it can become the go-to reaction to experiencing fear. Unlike fear, it moves us toward the source of our anger.

Unlike fear, it moves us toward the source of our anger.

Anger/Fear Crossword

Source: 123rf Stock Photo/Goran Stojkovic/Golden

The Physiology of Fear and Anger

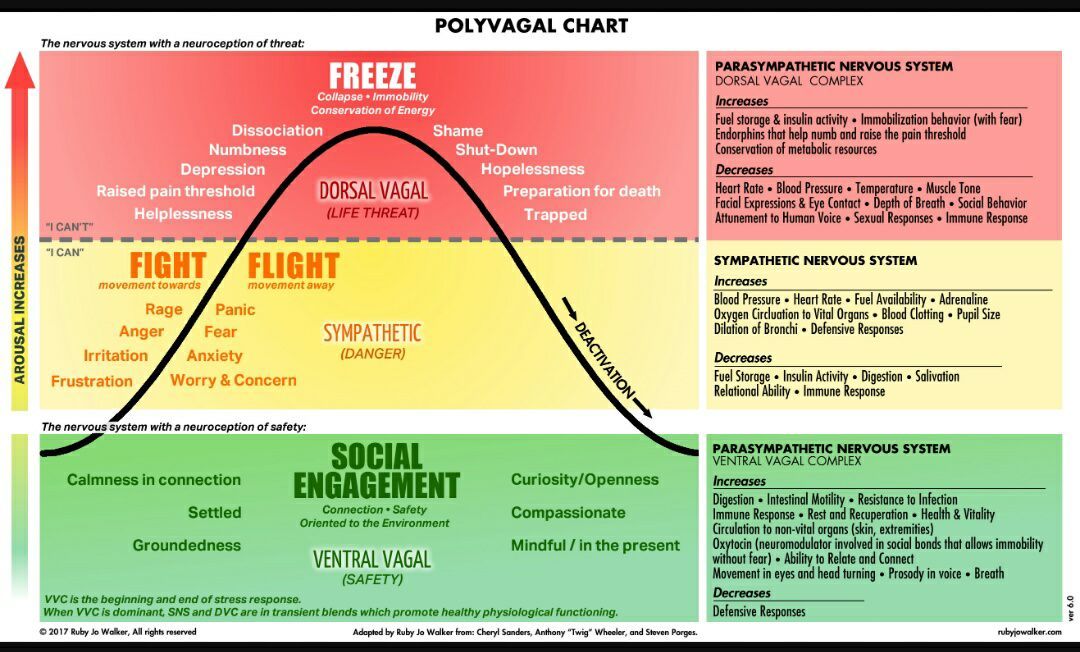

Both fear and anger trigger our threat system, physiological reactions associated with the “fight-flight or freeze” response. While there is some overlap, these emotions also arouse distinctly different reactions.

This was best identified by an early study in which 43 subjects were stimulated to experience fear and anger, while a variety of physiological reactions were recorded (Ax, 1953). These included (1) heart rate, (2) ballistocardiogram, (3) respiration rate, (4) face temperature, (5) hand temperature, (6) skin conductance, and (7) integrated muscle potential. The scores used were the maximum rise and fall from the preceding resting level.

Of the 14 scores, 7 showed significant discrimination between anger and fear. Diastolic blood pressure rises, heart rate falls, the number of rises in skin conductance and muscle potential were greater for anger than for fear. Additionally, there were greater intercorrelations for anger than for fear, which was interpreted as indicating greater physiological integration during anger.

Additionally, there were greater intercorrelations for anger than for fear, which was interpreted as indicating greater physiological integration during anger.

A more recent study explored physiological reactions in 183 students and employees of a large university (Moons, Eisenberger and Taylor, 2009). Participant’s baseline levels of anger, fear, cortisol, and two pro-inflammatory markers were assessed at the beginning of a stress session. They then completed the Trier Social Stress Task. This consists of presenting a speech and solving arithmetic problems in front of an audience.

Baseline anger and fear were related to greater cortisol and the pro-inflammatory markers. Anger reactions to the stressor were associated with increases in cortisol over time but not the pro-inflammatory cytokines. However, fear reactions were associated with increases in stress-related pro-inflammatory cytokines over time and a decrease in cortisol. The study supported the perspective that these distinct emotional experiences appear to trigger physiological processes that mobilize energy in response to anger and promote withdrawal in response to fear.

Fear and Anger as Motivators

Both fear and anger motivate us, with fear being more powerful in doing so. As such, companies often employ fear in advertising their products. They first instill fear and subsequently identify their product as the best way to alleviate it. Such advertising might state, implicitly or explicitly, that social approval and connection hinges on purchasing a particular brand of product, whether jeans, running shoes or a car.

Politicians may similarly use fear, in both their words and images of their campaign. Rather than highlight specific programs or policy they can offer, they may instead point out a fearful scenario as an outcome for not voting for them. When extreme, promoting fear and anger is a hallmark strategy used by authoritarian leaders to intensify our sense of threat and subsequently gain power. Additionally, targeting selective groups of “others” as being responsible for the threat. Once identified, anger and fear support prejudice toward and dehumanizing them. It is no surprise then, that fear and anger can culminate in hostility and aggression.

It is no surprise then, that fear and anger can culminate in hostility and aggression.

Fear, Anger, and Attention

Both fear and anger can hijack and constrict our attention. This reaction is often associated with the “fight, flight, or freeze” mode. Such narrowing of attention is powerfully revealed in both tunnel vision and auditory exclusion, two reactions reported by police officers involved in shootings. During tunnel vision, attention focuses on the target while the peripheral vision becomes a blur. And, while training may help reduce these effects, their arousal is less subject to personal will.

In one study of 40 college students, it was found that anger and fear inhibit associative memory (Adler, 2020). They were shown faces with three emotional expressions: neutral, angry, and fearful. Each face was paired with different objects under them. When assessed for their recall of the objects, the students’ performance was diminished regarding those images including faces expressing fear and anger.

When Fear or Anger Are Appealing

There are times when we may seek to experience fear or anger, even in spite of their discomfort. For example, we may enjoy viewing a scary movie or riding the most exhilarating roller coaster at the amusement park. Fear may be tolerable in both of these situations because we can feel in control when we experience certainty that we will not be harmed.

Additionally, we may seek to engage in activities that offer heightened physical excitement because they are in fact dangerous. These might include skydiving, climbing mountains, or extreme sports.

Similarly, anger may be experienced positively when it feels both physically and emotionally empowering. The term “addicted to anger” describes this tendency. It may be used to create distance in a relationship or to exert control, as in bullying. Or it can be channeled more constructively to further a cause, reflected, for example, by peaceful protest.

Being open to our fear and anger helps us better connect with ourselves. These emotions offer us insight into our sense of safety. Learning to recognize and acknowledge them offers us an opportunity to mindfully choose how to respond to, rather than react to them. Such skills enhance our emotional intelligence. Without such emotional flexibility, we remain subjected to fear and anger–and potentially to those who might benefit from their arousal.

These emotions offer us insight into our sense of safety. Learning to recognize and acknowledge them offers us an opportunity to mindfully choose how to respond to, rather than react to them. Such skills enhance our emotional intelligence. Without such emotional flexibility, we remain subjected to fear and anger–and potentially to those who might benefit from their arousal.

Basic emotions: what is anger

In religion, anger is one of the deadly sins, and there is something subtly attractive about it (of course, when it is not directed at us). We love to watch athletes rushing to victory, whose determination is mysteriously intertwined in the moment with anger, and we love to watch the heated debate of politicians who are not always able to refrain from cursing. But of course, we are much more hesitant about anger in our own lives. As part of a series of materials on basic emotions, we continue to understand feelings - this time about what makes us angry.

Anger is an emotion ranging from mild annoyance to intense rage. Many people think of anger as a negative feeling that excites us emotionally and makes us say things we sometimes don't even mean. Against this background, it may seem that anger is a kind of unnatural distortion of who you really are. But this is not true.

Many people think of anger as a negative feeling that excites us emotionally and makes us say things we sometimes don't even mean. Against this background, it may seem that anger is a kind of unnatural distortion of who you really are. But this is not true.

Anger is a perfectly natural emotion that alerts us when something is disturbing the natural order of things we think things should be. And it literally drives me crazy! The physical effects of anger are meant to encourage us to take responsibility and restore the balance of right and wrong. For this to happen, we must get angry for the right reason and express our anger properly. But how do you know which anger triggers are justified?

Many reasons to be angry

Everyone can probably name a few things that make them angry. An acquaintance who is always late, toys constantly scattered on the floor, a driver on the road who does not know how to drive by the rules, call center employees who call with stupid offers . .. The list is endless, but all these things come down to two aspects: violation of expectations and blocking targets. We expect to be treated fairly and get angry when we are yelled at for no reason. If our goal is to have a quick bite to eat before rushing to the train, a long line at the cafeteria can cause some anger.

.. The list is endless, but all these things come down to two aspects: violation of expectations and blocking targets. We expect to be treated fairly and get angry when we are yelled at for no reason. If our goal is to have a quick bite to eat before rushing to the train, a long line at the cafeteria can cause some anger.

If others do not adhere to our social or personal norms, we get angry

Anger triggers are different for everyone and depend on age, gender, background and even culture. In one study❓Tavris, Carol. Anger: The Misunderstood Emotion. Simon & Schuster. 1982. assessed anger in infants of different nationalities, and it turned out that Chinese infants were generally calmer in any experimental situation. For example, in one experiment, scientists briefly pressed a cloth against a baby's face, and American babies tended to get nervous and push it away, while Chinese babies put up with the presence of something on their face without getting "angry" about it.

But while this study is interesting, it certainly does not mean that anger is built into a particular culture. It doesn’t even mean that the child will necessarily grow up angry: other studies have shown that a one-year-old child with a tendency to tantrums can eventually turn into a completely gentle and calm five-year-old. However, each of these babies will recognize the triggers that are acceptable to their culture and how the culture will deal with them.

Another interesting observation❓Thomas, Sandra P., Carol Smucker and Patricia Droppleman. It hurts most around the heart: a phenomenological exploration of women's anger. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1998. - Anger in women is more often caused by close relationships: they often feel disappointed in relation to family members and friends, or feel that these people expect too much from them, without giving anything in return. A man is more likely to be angered by the behavior of strangers, objects that don't work properly, and larger social issues that raise concerns about right and wrong.

Male anger is a bit more abstract, female anger seems to be mixed with emotional pain, and childish anger tends to be about blocking goals and objects (try taking a toy away from a child!)

But these triggers alone are not enough to make us angry. In fact, there is a mental component by which we judge whether anger is a justified response. Literally in a split second, we find out who is to blame, how dangerous the trigger is, whether the action could have been avoided, and whether anger would be useful at all in this situation. We also evaluate the intent of the person behind the trigger based on the information we have. So, we can get angry at a driver who cuts us off and breaks the rules of the road. But if we find out that he did this because he is trying to get to the hospital in time for the birth of his first child, our fervor will probably subside.

The brain determines if a trigger justifies our anger in less than a minute, but what happens to the body while the brain is busy with this assessment?

The physical effects of anger

Do you remember the cartoon "Inside Out"? When a character representing anger gets angry, steam comes out of his ears, and he himself is red from head to toe. In real life, anger has about the same effect on our body. The response certainly varies from person to person, but some symptoms are common and include grinding teeth, clenching fists, redness or blanching of the skin, tingling, numbness, sweating, muscle tension, and changes in body temperature.

In real life, anger has about the same effect on our body. The response certainly varies from person to person, but some symptoms are common and include grinding teeth, clenching fists, redness or blanching of the skin, tingling, numbness, sweating, muscle tension, and changes in body temperature.

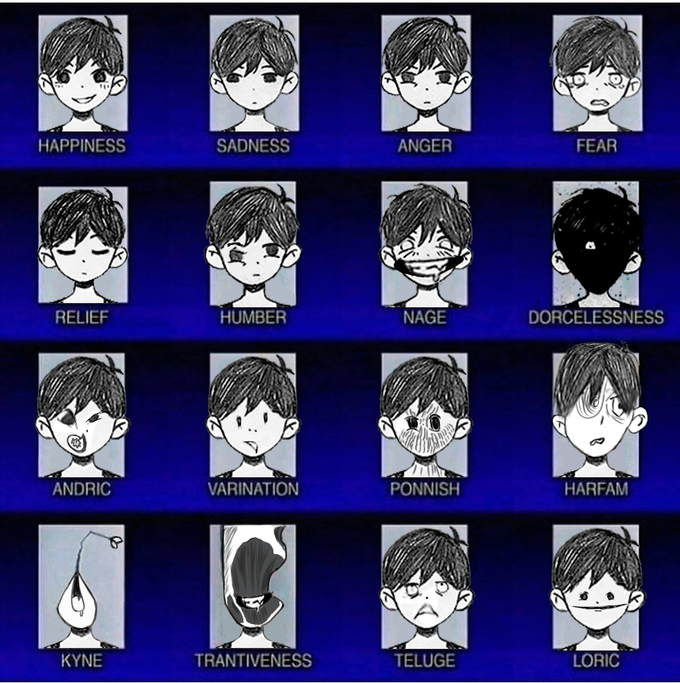

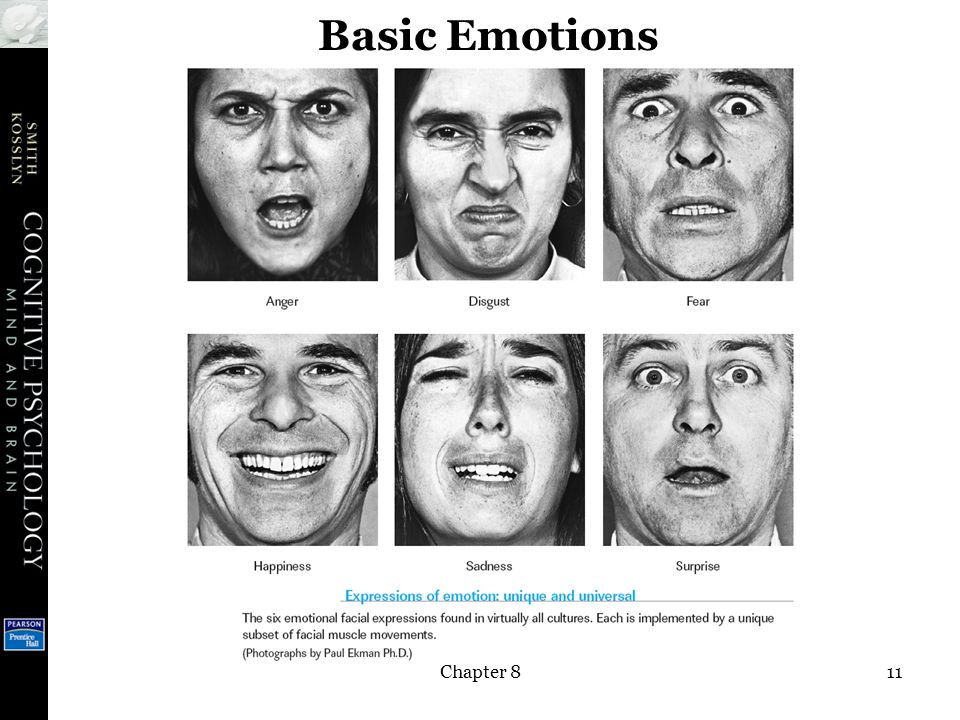

Anger also has special mimic expressions - like other basic emotions, anger is easily read on our face:

The feeling of anger can differ from person to person: women, for example, are more likely to describe anger as a feeling that slowly builds up through the whole body , while men describe it as a raging fire, generally more active and faster. In any case, the sensations described are very similar to the "fight or flight" reaction - the body is preparing for a fight in order to survive the evil committed against you. Chemicals such as adrenaline and norepinephrine permeate the body.

In the brain at this moment, the amygdala, the part of the brain responsible for emotions, goes crazy. The brain really wants to somehow respond to the irritating factor and its “thinking” about it, the time between reading the trigger and the response of the amygdala can be only a quarter of a second. However, at the same time, blood flow to the frontal lobe increases, especially to the part that is above the left eye - this area controls reasoning and probably in most cases prevents us from simply picking up and throwing a vase across the room at an expensive TV. Usually, these areas balance each other out quickly (the neurological response to anger lasts less than two seconds), which is why you can find so many tips from category 9.0041 "count to 10 before reacting" - this works because the brain has time to calm down.

The brain really wants to somehow respond to the irritating factor and its “thinking” about it, the time between reading the trigger and the response of the amygdala can be only a quarter of a second. However, at the same time, blood flow to the frontal lobe increases, especially to the part that is above the left eye - this area controls reasoning and probably in most cases prevents us from simply picking up and throwing a vase across the room at an expensive TV. Usually, these areas balance each other out quickly (the neurological response to anger lasts less than two seconds), which is why you can find so many tips from category 9.0041 "count to 10 before reacting" - this works because the brain has time to calm down.

Are animals angry?

It's easy to imagine that animals are just as angry as we are. The bull is "annoyed" by the red rag (in fact, the bulls are color blind), and he is ready to smash everything around. You accidentally step on a cat's tail, it hisses, arches its back and seems ready to kill the offender. Finally, dogs growl and bark at people passing behind the fence. However, anger requires a mental component that many scientists believe animals are not capable of. Anger and fear stimulate similar mechanisms in the body, and the reaction of the animal is most likely associated with fear, the primary emotion. Anger is considered a secondary emotion because, on top of that, we use our brains to attribute guilt.

Finally, dogs growl and bark at people passing behind the fence. However, anger requires a mental component that many scientists believe animals are not capable of. Anger and fear stimulate similar mechanisms in the body, and the reaction of the animal is most likely associated with fear, the primary emotion. Anger is considered a secondary emotion because, on top of that, we use our brains to attribute guilt.

If anger triggers constantly hit you, a persistent state of neurological response can begin to damage your health. At the same time, chronically angry people may not have a mechanism for "turning off". For example, their bodies may not produce acetylcholine, a hormone that moderates the more severe effects of adrenaline. As a result, their nervous system is constantly turned on and in tension, which ultimately can lead to overwork, weakening of the heart and stiffening of the arteries. There is also the possibility of damage to the liver and kidneys, increased cholesterol levels. Finally, anger can cause associated mental problems such as depression or anxiety.

Finally, anger can cause associated mental problems such as depression or anxiety.

In one study of nearly 13,000 subjects, people with the highest levels of anger were twice as likely to have coronary heart disease and three times as likely to have a heart attack compared with subjects with the lowest levels of anger.

Some scientists believe that chronic anger as a contributing factor to early death may be even more dangerous than smoking and obesity trifle. However, for others, conscious work on expressing anger may be required.

How to express anger correctly

Anger cannot solve the problem that makes you angry, but its physical signals warn you to do something and express anger in the right way .

The expression of anger usually takes one of three forms: expressing anger, expressing anger, and controlling anger. Anger quite often turns anger inward, since in many societies open expression of it is something unacceptable.

The pent-up anger can escalate into unproductive passive-aggressive behavior, such as silent resentment (“pouting”) or sarcastic comments. However, while you shouldn't hold back your anger within yourself, attacking anyone who makes you angry is also unlikely to make you feel better in all cases. The ideal expression of anger is the practice of controlling it.

In one of the studies❓Weber, Hannelore. Explorations in the Social Construction of Anger. Motivation and Emotion. June 2004. Respondents determined that talking to the abuser was the most appropriate way to deal with anger. And this is not about swearing at another person, but about a specific explanation to him why you are angry. Of course, this way of expressing anger can sometimes make it useful - we strive to remove negativity from our lives, which means that a constructive expression of anger can make us, for example, fix relationship problems.

But although we know that talking is the most productive way to control our anger, this does not mean that we can always and everywhere practice this approach.

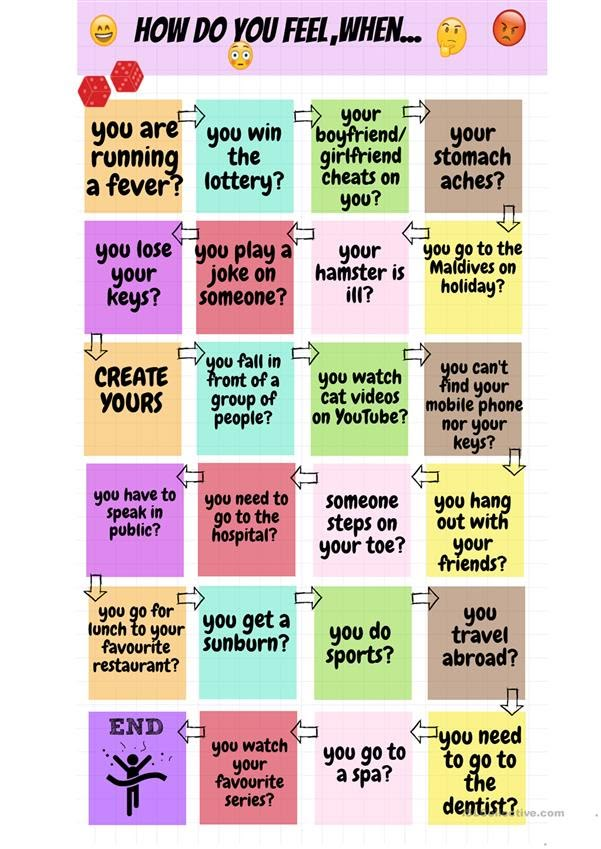

It is hardly possible to track every careless driver on the road in order to calmly talk to him ... In cases where this is not possible, it is important to find other healthy ways to get your body out of anger. For example, go in for sports, meditate or watch your favorite series. There can be a lot of ways to relax, and they are individual for each person (the main thing is to find those that will calm you without harming other people).

Chronically angry people expect disappointment in the events around them for many years - as a result, these people react more angrily even to small stressful events, but in doing so, they create even more reasons for anger. Unfortunately, the result of this condition is health problems, higher levels of family conflict, and lower levels of social support due to how anger affects others. If you feel like your emotions are taking over, it might be time to start thinking about anger management practices.

Anger. Fear. Resentment. How to learn to manage? - article - Corporation Russian textbook (Drofa-Ventana publishing house)

Emotional intelligence: founding fathers

American psychologist Daniel Goleman, a specialist in emotional intelligence, has developed several components that help us communicate with people and remain ourselves.

"Personal competence is the ability to cope with oneself, to negotiate with the most important person in one's life."

Daniel Goleman

Self-consciousness — knowledge of one's own states, preferences, possibilities. Understanding how I react, the ability to evaluate, predict my own reactions, the ability to reflect. Sometimes the right questions (What exactly am I afraid of? Why does this cause anger?) help find the answer and understand why we react so strongly to some events - for what reason, for example, resentment arises.

Self-regulation - The ability to cope with one's internal states and impulses.

Often people do not want to do anything to get rid of negative emotions. But the first step to stop being offended is to stop shifting responsibility for your life to someone else, to understand that I manage my own life on my own.

When a person is overwhelmed with emotions, he may misread the states of other people.

Before evaluating the emotions of another, check with yourself: most likely, it is you who are sad or annoyed.

Another psychologist and emotional specialist is Paul Ekman. He believes that basic emotions appear due to neural programs laid down in a person from birth, so most of these emotions are innate. On their basis, complex social structures and phenomena are formed.

Basic emotions:

- Joy

- Surprise

- Sadness

- Anger

- Disgust

- Contempt

- Fear

Please note: there is no offense in this list. And all because resentment consists of two different emotions.

Robert Pluchek and Henry Kellerman created the wheel of emotions and said that emotions can change very quickly. Scientists emphasized that emotions, unlike moods, can change each other instantly and proceed quite intensively.

Wheel of emotions

Emotions correlate with character traits.

If, say, a person tends to feel more fear, then he is most likely timid. Other emotions have the same feature:

joy - friendliness

waiting - curiosity

state of sadness - depression

anger - aggressionEmotions are based on genetics. And for this reason, sometimes it is almost impossible to change something in yourself. What is inherent in the core of character, one way or another, will accompany a person all his life as a background - this is almost equal to the physiology that is given to us from birth.

Anger. How to cope and help others?

The worst thing you can say to an angry person is "calm down". If there is a state of anger and excitement, a person will not be able to instantly switch to calmness, he must live the whole range of emotions.

The energy of anger is the energy of movement. If you feel a surge of excitement and anger, change your body position.

If you were sitting, stand up; if you were standing, sit down. Do an energy reset: exhale deeply, hold your breath, inhale again.

Shake your hands as if shaking something off them. Clench and unclench your fists. Push up from the wall, stand in a plank if possible. Put a chair in front of you and say everything you would like to say to your offender (child, parent, boss, friend - no matter who the conflict is with). Crumple and tear a piece of paper or a rag, you can even try to tear a tennis ball. Another good tool is light colored sticks with which you swim in the pool. Beat, wave them into space.

In order not to yell at the offender in a fit of anger, immerse yourself in the sensations of the body. Try to catch how your toes feel in shoes, fingers. Try to make yourself an anchor - some kind of bright object that will stand on the table and into which you can place your aggression and anger. Look at him during a rolling storm of emotions, immerse yourself in this state, and give him everything that you almost spilled out on a real person.

We yell, they yell at us - nothing but a surge of emotions, anger and resentment at this moment, we, unfortunately, do not experience. Therefore, learn to direct the conversation in a constructive direction.

If the conflict occurred with the child, in order not to give out too violent an uncontrollable reaction, you can first try to warn the offender, and, if necessary, even raise your voice: “I am very angry, now I will scream.” This will help both you and the child. A certain safety mechanism will turn on in the child, and your emotions may recede, because you have already helped yourself with this phrase. Look into the eyes of the child, be physically on the same level with him, do not fall on him from above so that he does not experience powerful fear. Later, if you still couldn’t restrain yourself, and an emotional wave burst out, warn the teenager - now he saw what he shouldn’t do: “These were unnecessary emotions, forgive me, but now let’s get back to what I want you say".

And just like with parental emotions, sometimes you don't need to try to stop a child's tantrum. Let him scream - release anger, resentment, irritation. He can just shout something like “hey!!!” - if it makes it easier for him, why not. But such a practice should not be included in the system. If you are afraid of the frequency of similar reactions, contact a psychologist in order to have a sufficient number of practices for working with negative emotions in stock.

Resentment. What to do?

Resentment is a reaction of unreacted anger to some words, to injustice. Offended, people can live for years. But let's see if we can manage resentment. The correct answer is yes, and moreover, only the offended person himself can change the situation. After all, it is he who makes the decision to be offended, and not his offender. Sometimes the people we resent didn't want to offend us at all

Ask yourself: what is preventing my resentment? Communication with this person whom I am offended by, or maybe something else?

There is a good exercise.

Speak on the inhale: "I", and on the exhale: "I forgive ...".

Help your child get over the offense, and in general, do not devalue the feelings of children. If a teenager is offended, feel, live this offense with him. Remember: trying to forcibly pull him out of some kind of negativity, you break parent-child communication. Instead of preventing the child from experiencing the emotion, join him in the moment, don't shield him from it. In other words, show empathy.

Fear. How to survive?

Fear is a response to a threat, real or imagined. But remember that fear and fright can be a completely normal reaction to something new.

When a child says "I don't want" it most likely means "I can't" or maybe even "I'm afraid". Fear of communication, fear of not being able to handle something new, fear based on past experience.

Objective fear has a protective function - without it, we would not be afraid to go out the window of the 14th floor and could calmly step into an empty elevator shaft.

Subjective fear also protects us from some kind of psychological experience. But in order to curb children's fears, we, as parents, must create as many comfort zones for them as possible: enter these states with them, be afraid with them in order to feel this emotion.

Cutting Fear into Pieces Technique

When we talk about fears, it is important to name what exactly I am afraid of. If, for example, I am afraid of old age, then I need to understand what exactly scares me in it? Maybe fear of being alone? Then what can I do right now to not be lonely in my old age? Start making a plan!

What then to do with the fear of uncertainty? The same! Ask yourself what can you do right now? You do not know what will happen tomorrow and the day after tomorrow, but today is in your power - the moment when you can make a decision.

Do not try to solve problems in uncertainty that concern the meaning of life. Just write down three things in your notebook that you can solve the very next morning.