Can i take antidepressant while pregnant

Antidepressants and Pregnancy: Tips from an Expert

Most pregnant women want to do everything right for their baby, including eating right, exercising regularly and getting good prenatal care. But if you’re one of the many women who have a mood disorder, you might also be trying to manage your psychiatric symptoms as you prepare to welcome your new baby.

It’s common for doctors to tell women with mood disorders to stop taking drugs like antidepressants during pregnancy, leaving many moms-to-be conflicted about giving up the medications that help keep them healthy.

Lauren Osborne, M.D., assistant director of the Johns Hopkins Women’s Mood Disorders Center, talks about why stopping your medication may not be the right approach. She explains how women can — and should — balance their mental health needs with a healthy pregnancy.

Antidepressants and Pregnancy

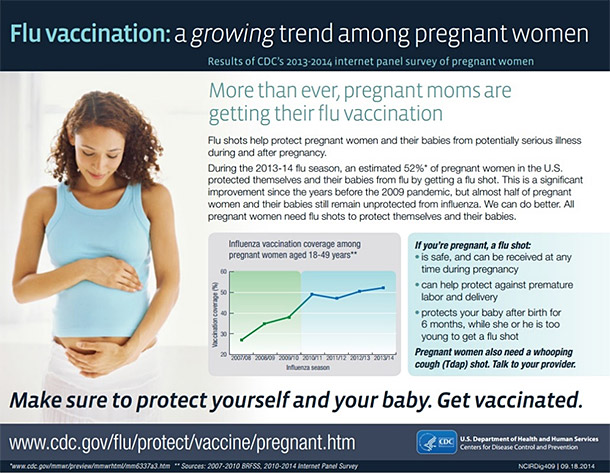

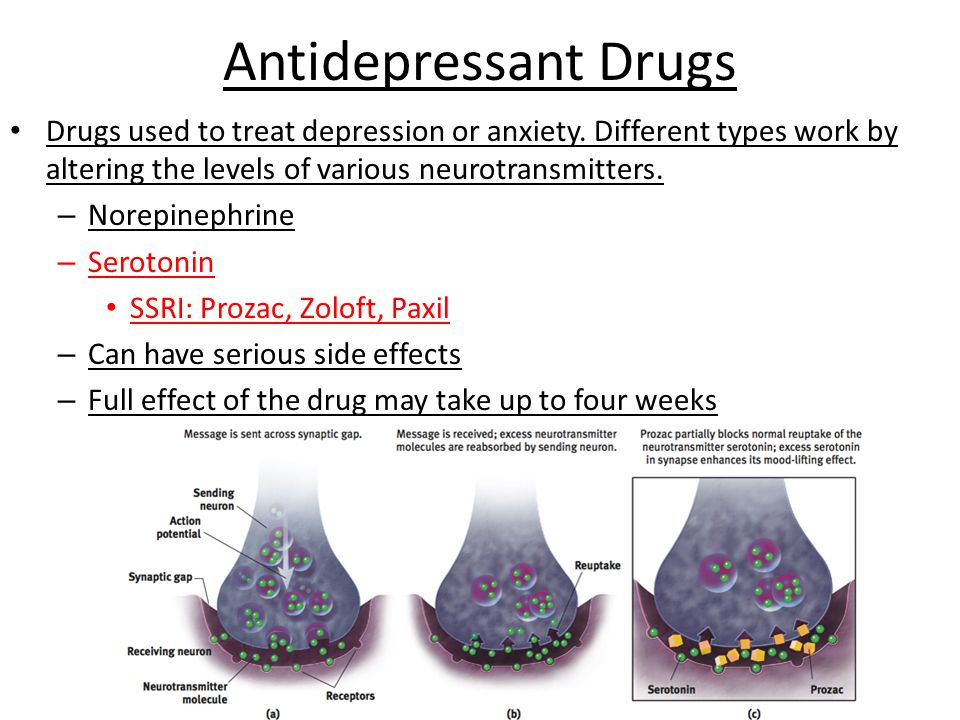

Women who take antidepressants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), during pregnancy may worry about whether the medications can cause birth defects.

There is good news on this front. Osborne says that there is generally no need to taper off medications during pregnancy. “We can say with strong confidence that antidepressants don’t cause birth defects,” says Osborne. She adds that most studies finding a physical effect on babies from antidepressants taken during pregnancy fail to account for the effects of the mother’s psychiatric illness.

In fact, untreated mental illness itself poses risks to a developing fetus. A woman who is depressed is less likely to get good prenatal care and more likely to engage in unhealthy or dangerous behaviors, like smoking and substance abuse. Osborne also says mental illness has direct effects on newborn babies.

“Untreated depression may increase preterm birth or cause low birth weight,” she says. “Babies of depressed moms have higher levels of a hormone called cortisol. This raises a baby’s risk of developing depression, anxiety and behavioral disorders later in life.”

Weighing the Risks

While doctors don’t believe antidepressants cause birth defects, it’s still possible for them to affect the baby. It’s important for a mother and her doctor to know the risks.

It’s important for a mother and her doctor to know the risks.

About 30 percent of babies whose mothers take SSRIs will experience neonatal adaptation syndrome, which can cause increased jitteriness, irritability and respiratory distress (difficulty breathing), among other symptoms. Doctors aren’t sure whether this effect is due to the baby’s withdrawal from the SSRI after birth or exposure to the drug itself before birth.

“It may be distressing and cause pediatricians to run tests, but it will go away,” says Osborne, pointing out that these symptoms also sometimes occur in babies whose mothers don’t take SSRIs.

Common medications women frequently ask about include:

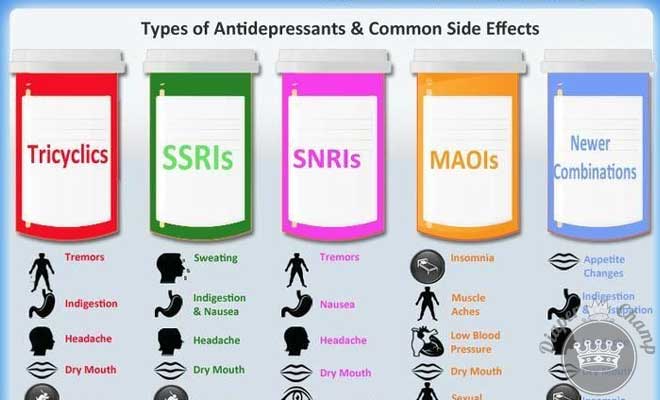

- SSRIs: Some studies link SSRI use with a very rare defect called persistent pulmonary hypertension, which is a condition where babies’ lungs don’t inflate well. “The most recent study looked at 3.8 million women and showed there was no increase in risk to their babies,” says Osborne.

- Paroxetine: Early studies on a small number of patients connected the SSRI paroxetine with cardiac defects in babies. However, these studies didn’t account for smoking, obesity and other risk factors that are more common in women who have depression. Osborne says larger, more recent studies show no such link with cardiac defects. She doesn’t recommend switching medications if paroxetine is the only one that works for you.

- Benzodiazepines: Women should avoid using tranquilizers, such as diazepam, alprazolam and clonazepam, in high doses during pregnancy because they can lead to sedation and respiratory distress in the newborn. You can still use them in small doses for short periods of time. However, Osborne will typically try to get mothers on intermediate-acting options like lorazepam. These medications don’t linger in the baby’s bloodstream like longer-acting forms and aren’t associated with high rates of abuse like shorter-acting forms.

- Valproic acid: This medication treats seizures and bipolar disorder, and does carry significant risk to a developing fetus. Taking valproic acid during pregnancy carries a 10 percent risk of neural tube defects — birth defects that affect the brain or spinal cord, such as spina bifida — as well as risks to the baby’s cognitive development, such as lower IQ. “Valproic acid is the only one I’d never prescribe for pregnant women unless all other treatment had failed,” says Osborne .

Seeing a Reproductive Psychiatrist

If you have a mood disorder, you may benefit from speaking with a reproductive psychiatrist when you are pregnant or thinking about becoming pregnant. Ideally, this should happen when you are planning for pregnancy, although this isn’t always possible. Meeting with a doctor after you become pregnant is not too late.

Osborne says her approach with patients is to limit the number of potentially harmful exposures to the baby. This means considering the number of medications a mother is on, as well as her psychiatric illness.

This means considering the number of medications a mother is on, as well as her psychiatric illness.

“If a woman takes a low dose of many medications and we have time to plan, we’ll try to get that down to a higher dose of fewer medications,” she says. “If a woman is on a low dose and it’s not controlling her illness, then her baby is exposed to both the medication and the illness. In that case, I would increase the medication dosage so her baby isn’t exposed to the illness.”

If your illness is mild, your doctor might recommend getting off medication and replacing it with treatments such as psychotherapy, prenatal yoga or acupuncture to improve your mood.

Ultimately, Osborne says women should weigh the risks of medication against the risk of untreated illness.

“If a particular side effect is extremely rare, it’s still a very rare event even if you double the risk,” she says. Medication risks are typically not greater than those of untreated mental illness. “Switching a woman’s medication is something I do very carefully and reluctantly. ”

”

What is the Best Antidepressant to Use During Pregnancy?

This is a question we often hear. One of the challenges in answering this question is the interpretation of the word “best”. On one hand, the best antidepressant is the one that is the most likely to be effective. On the other hand, the best antidepressant is the one that carries the least risk when used during pregnancy. What this means is that there is no single answer. Each situation is different, and our recommendations are based on a careful assessment of the patient’s course of illness, treatment history, past medication trials, and the most up-to-date information on reproductive safety. Added to this calculation is the understanding that untreated depression also carries some risk in terms of maternal well-being and has been associated with worse pregnancy outcomes.

Stay with the Same Treatment or Switch?

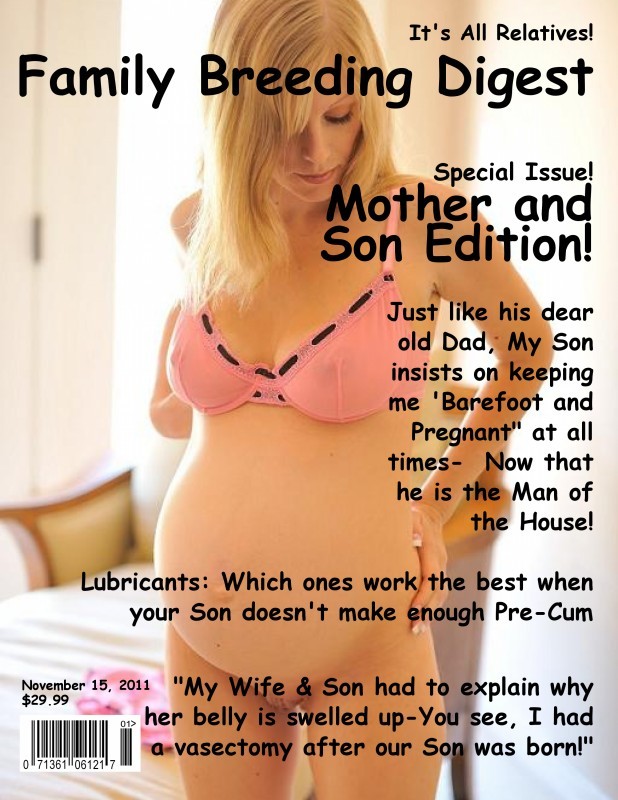

We often meet with women who have switched to a different antidepressant medication in preparation for pregnancy. Other women make a switch when they discover they are pregnant. These switches are motivated by the belief that there is a “safer” medication to be used during pregnancy. The reality is that most of the antidepressants taken by women today are relatively safe and carry a very low risk to the developing fetus. What separates one antidepressant from another is that some medications have more data to support their reproductive safety than others. But even this distinction is disappearing; we have data to support the use of most SSRIs (with less data on fluvoxamine or Luvox), the SNRIs duloxetine (Cymbalta) and venlafaxine (Effexor), and bupropion (Wellbutrin). Tricyclic antidepressants, although not commonly used today, also have data to support their reproductive safety.

Other women make a switch when they discover they are pregnant. These switches are motivated by the belief that there is a “safer” medication to be used during pregnancy. The reality is that most of the antidepressants taken by women today are relatively safe and carry a very low risk to the developing fetus. What separates one antidepressant from another is that some medications have more data to support their reproductive safety than others. But even this distinction is disappearing; we have data to support the use of most SSRIs (with less data on fluvoxamine or Luvox), the SNRIs duloxetine (Cymbalta) and venlafaxine (Effexor), and bupropion (Wellbutrin). Tricyclic antidepressants, although not commonly used today, also have data to support their reproductive safety.

MAO Inhibitors: We have very little data on the reproductive safety of the MAO inhibitors. In addition, MAO inhibitors may have serious interactions with other medications frequency used during pregnancy and labor and delivery, specifically medications used to manage pain, such as nalbuphine (Nubain) and meperidine (Demerol). In women taking these medications, we are likely to suggest switching to another antidepressant with a better reproductive safety profile.

In women taking these medications, we are likely to suggest switching to another antidepressant with a better reproductive safety profile.

Mirtazapine (Remeron): At this point, we have less data on the use of the newer antidepressants. There is some data on mirtazapine, with the most recent study including 334 cases of neonates with prenatal exposure to mirtazapine. While these data are reassuring and there is no indication that mirtazapine carries significant teratogenic risk, the number of mirtazapine exposures remains small. Ideally we would like to have data from 600-700 exposures to get a better estimate of risk. Making decisions regarding safety on studies with small sample sizes can lead to miscalculations of risk in either direction.

Other Antidepressants: The data is even more limited with regard to the use of vortioxetine (Trintellix), vilazodone (Viibryd), levomilnacipran (Fetzima). If there are effective alternatives, we typically recommend switching to another antidepressant.

In settings where we have limited data regarding the reproductive safety of a particular antidepressant, we may consider switching to an antidepressant with a better characterized reproductive safety profile. It is important, however, to carefully consider the benefits and risks of making this switch. With any switch, there is the risk of relapse when making a change in the maintenance treatment. Thus, there are situations where we recommend continuing an antidepressant with limited reproductive safety information because there are no effective alternatives and the risk of relapse is significant.

What About Zoloft? Isn’t Zoloft the Safest?

At some point in the early 2000s, there emerged the belief that sertraline (Zoloft) was the safest antidepressant to use during pregnancy, and many women taking other antidepressants were encouraged to switch to sertraline during pregnancy. It is somewhat unclear where this opinion came from — maybe one paper suggesting lower placental passage of sertraline compared to other antidepressants; however, there is and never was any solid data to support the assertion that sertraline is safer or the safest antidepressant. Reflexively switching women to sertraline puts women at risk for recurrent illness.

Reflexively switching women to sertraline puts women at risk for recurrent illness.

While sertraline is effective for the treatment of depression and anxiety and is a reasonable choice for many women, one problem with sertraline is that it tends to be under-dosed. The typical starting dose is 50 mg; however, many individuals will need 150 mg to 200 mg to effectively manage their symptoms. Especially when sertraline treatment is initiated in the primary care setting, we often see women whose dose is too low to effectively manage their symptoms.

What About Paxil? Doesn’t It Cause Heart Defects?

The most current data regarding the use of paroxetine (Paxil) during pregnancy does not indicate an association between the use of paroxetine during pregnancy and risk for cardiovascular malformations. However, in 2006, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) elected to change product label warnings for the antidepressant paroxetine (Paxil), advising against the use of this drug by women who are pregnant. This decision was based on two preliminary studies which suggested a small increase in the risk of cardiovascular malformations among infants exposed to paroxetine in utero. For many years, this concern regarding risk of heart defects resulted in recommendations that women taking paroxetine should either stop paroxetine or to switch to a different antidepressant during pregnancy.

This decision was based on two preliminary studies which suggested a small increase in the risk of cardiovascular malformations among infants exposed to paroxetine in utero. For many years, this concern regarding risk of heart defects resulted in recommendations that women taking paroxetine should either stop paroxetine or to switch to a different antidepressant during pregnancy.

However, in 2008, a study from the Motherisk Program in Toronto reported on the outcomes of over 3000 paroxetine-exposed infants and found no association between the use of paroxetine during pregnancy and increased risk of cardiovascular malformations. Nonetheless, some women and their treaters continue to feel uncomfortable with the use of paroxetine during pregnancy. Furthermore, many websites (including reputable sites like the Mayo Clinic) continue to urge women to avoid paroxetine during pregnancy because of the risk of malformations.

At this point, we typically do not recommend switching from paroxetine to another antidepressant for pregnancy. Although paroxetine is an SSRI, there are definitely situations where an individual may respond better to paroxetine than to other SSRIs. Thus, switching to a different antidepressant may increase risk for relapse.

Although paroxetine is an SSRI, there are definitely situations where an individual may respond better to paroxetine than to other SSRIs. Thus, switching to a different antidepressant may increase risk for relapse.

What About Lexapro? And Pristiq?

There are some newer antidepressants that are derived from older parent antidepressants. For example, citalopram (Celexa) is a racemic mixture, composed of R- and S-enantiomers (or mirror images) of citalopram. While the S-enantiomer is clinically active, the R-enantiomer is not. Escitalopram or Lexapro contains only the active S-enantiomer. Because the S-enantiomer is contained in the original citalopram formulation, we can infer that the reproductive safety of escitalopram (Lexapro) is the same as that of citalopram (Celexa).

Another example is desvenlafaxine or Pristiq. For venlafaxine to be effective as an antidepressant, it must first be metabolized by the body to desvenlafaxine. Pristiq contains only the active metabolite desvenlafaxine. Because desvenlafaxine is a metabolic byproduct of the original venlafaxine formulation, we can infer that the reproductive safety of desvenlafaxine (Pristiq) is the same as that of venlafaxine (Effexor).

Because desvenlafaxine is a metabolic byproduct of the original venlafaxine formulation, we can infer that the reproductive safety of desvenlafaxine (Pristiq) is the same as that of venlafaxine (Effexor).

The Bottom Line

No two situations are identical; thus, we must carefully consider each woman’s clinical history and preferences in order to select a treatment plan that makes sense. Ideally this discussion should occur long before a woman is pregnant, so that there is ample time to consider the various options and to make changes, if necessary.

When we meet with women to discuss the use of antidepressant medications during pregnancy, we typically consider a number of issues:

- Determine the risk of recurrent illness: Has she had one episode of depression or does she have recurrent depression? If she has attempted to discontinue antidepressants in the past, how long was she able to remain well without medication? If she has had prior pregnancies, what happened to her mood during pregnancy and the postpartum period?

- Assess the severity of previous episodes of depression: Did the depression contribute to missed days of school or work? Psychiatric hospitalization? Suicidal ideation? Self-harm? Suicide attempt?

- Review past medication trials: What antidepressants have been effective in the past? Which antidepressants have been ineffective? Assess dose and duration of treatment to determine if the trial was adequate.

- Identify factors that may mitigate risk: Has psychotherapy been helpful? Is this an option for decreasing risk for relapse? What about other non-pharmacologic interventions: mindfulness, meditation, yoga, acupuncture, exercise?

- Discuss options for pharmacologic treatment during pregnancy: What are the antidepressants most likely to maintain stable mood during pregnancy? What is the medication with the best characterized reproductive safety profile? Does it make sense to maintain or to switch to a different antidepressant? Even if the woman ultimately decides that she would like to avoid medications during pregnancy, it is important to discuss options for treatment, in case she relapses during pregnancy and would like to resume treatment.

We now have data to support the reproductive safety of a large number of antidepressants.

The perinatal psychiatry consultation should be viewed as a collaborative venture, where provider and patient decide together what is the best option for treatment during pregnancy.

Ruta Nonacs, MD PhD

Related Posts

FGBNU NTsPZ. ‹‹Depression in General Medicine: A Guide for Physicians››

The choice between the need for pharmacotherapy, on the one hand, and the prevention of risks to the health of the fetus or newborn (danger of the formation of congenital malformations, pre- and neonatal complications, etc.) - on the other hand, is required from the doctor in case of depression that manifests or worsens during the period pregnancy.

When deciding on such an alternative (the proportion of benefit to the mother and the potential risk to the child), a number of circumstances are taken into account, including the possibility of a negative impact on the development of the fetus from a severe mental state of the mother during pregnancy. nine0003

Psychotropic drugs for pregnant women are prescribed if absolutely necessary according to strict clinical indications:

- with pronounced affective manifestations with anxiety, agitation, sleep and appetite disorders, aggravating the somatic condition of pregnant women and women in childbirth;

- with suicidal thoughts and tendencies.

However, in some cases, such as unplanned pregnancy, antidepressants are taken out of ignorance - a depressed woman, not yet aware of the pregnancy, may continue to take psychotropic drugs and be exposed to them. nine0003

Penetrating through the placenta or with mother's milk, psychotropic drugs can have an adverse effect on the fetus or newborn. Microsomal enzymes of the fetal liver are less active and are in a lower concentration compared to the liver of adults, which prolongs and enhances the effect of drugs. In the prenatal period, the blood-brain barrier is not yet fully formed and the immature CNS is generally more sensitive to the action of drugs. At the stage of embryogenesis, as well as in the early postnatal (neonatal) period of ontogenesis, the development of these vital structures is not completed, which can enhance the toxic effect of psychotropic drugs on both the fetus and the newborn. Such effects include potentially reversible, dose-dependent effects that may be exacerbated by the fact that metabolic systems have not yet fully formed. The constant use of drugs by a pregnant woman can lead to drug dependence of the fetus and, ultimately, to a withdrawal syndrome in the newborn [Vybornykh D. E., 1996].

The constant use of drugs by a pregnant woman can lead to drug dependence of the fetus and, ultimately, to a withdrawal syndrome in the newborn [Vybornykh D. E., 1996].

During lactation, taking antidepressants due to the possibility of the neonatal complications listed above is also highly undesirable. The mother should be convinced that in this situation it is more appropriate to feed with donor milk or artificial mixtures.

Differentiation of antidepressants in accordance with the degree of risk of developing toxic effects for infants fed by a mother taking psychotropic drugs of this class is shown in Table. 16. nine0003

Table 16. Risk of developing toxic effects in children breastfed by mothers taking antidepressants

| Level of risk | ||

| short | average | tall |

| Mianserin | SSRI | Doxepin |

| TCAs (majority) | ||

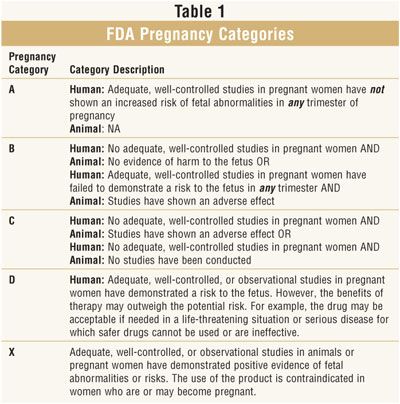

When deciding on the use of antidepressants during pregnancy, it is necessary to take into account data on the risk of teratogenic effects of antidepressants. The teratogenic effects of antidepressants cannot be completely ruled out from laboratory animal data and some very limited clinical observations. nine0003

The teratogenic effects of antidepressants cannot be completely ruled out from laboratory animal data and some very limited clinical observations. nine0003

There are 3 classes of teratogenicity of psychotropic drugs: class A - no teratogenicity in animals, no studies of the risk of teratogenicity in humans, or teratogenicity in animals has been established, but not in humans;

class B - known to be teratogenic in animals, no risk studies of teratogenicity in humans, or no studies of risk of teratogenicity in either animals or humans;

class B - teratogenicity has been proven, but the benefits associated with prescribing drugs sometimes outweigh the risks (eg, in a life-threatening situation). nine0003

The distribution of drugs by teratogenicity classes is presented in Table. 17. Data are given for the first trimester of pregnancy.

Table 17. Distribution of psychotropic drugs by teratogenicity classes Psychotropic Drug Directory, 1997]

N., 1995; Winn, 1995; Stowe Z. N., Nemeroff S. V., 1996; Yoshida K. et al., 1997; Piontek C. M., 2001].

N., 1995; Winn, 1995; Stowe Z. N., Nemeroff S. V., 1996; Yoshida K. et al., 1997; Piontek C. M., 2001].  The use of psychotropic drugs in such cases is also the prevention of postpartum depression. nine0003

The use of psychotropic drugs in such cases is also the prevention of postpartum depression. nine0003  Depression during pregnancy without proper treatment can result in more severe postpartum depression for a woman, and also increases the likelihood of premature birth and / or low birth weight babies.

Depression during pregnancy without proper treatment can result in more severe postpartum depression for a woman, and also increases the likelihood of premature birth and / or low birth weight babies.  The researchers also analyzed data on siblings whose mothers took antidepressants during each pregnancy, or during individual pregnancies. Additionally, work was carried out to analyze the health status of those women who stopped taking previously prescribed antidepressants with the onset of pregnancy, those who continued taking them, and those who never took these drugs. nine0003

The researchers also analyzed data on siblings whose mothers took antidepressants during each pregnancy, or during individual pregnancies. Additionally, work was carried out to analyze the health status of those women who stopped taking previously prescribed antidepressants with the onset of pregnancy, those who continued taking them, and those who never took these drugs. nine0003  nine0003

nine0003