Can adhd cause hallucinations

ADHD and Schizophrenia: Similarities and Differences

While it’s common for mental health conditions like ADHD and schizophrenia to co-occur, they’re not always inherently linked.

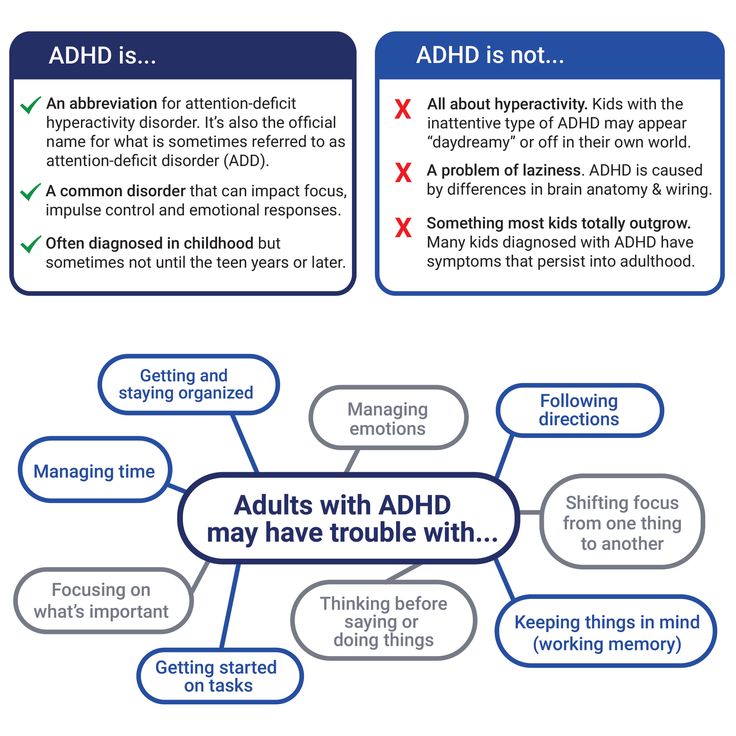

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and schizophrenia are mental health conditions that may impact the way you navigate the world around you.

Although comorbidities between mental health conditions may exist, it doesn’t mean that one condition will necessarily cause the other.

Research from 2015 suggests there may be some overlap between ADHD and schizophrenia. Yet there are distinct differences between the two conditions regarding symptoms, causes, diagnosis, and treatment.

Symptoms

While some symptoms of ADHD and schizophrenia may appear similar, there are a few fundamental differences.

Similarities

Both ADHD and schizophrenia may affect memory and attention.

In some cases, ADHD and schizophrenia may be co-occurring. ADHD may also be paired with other forms of psychosis, which may be caused by specific lifestyle factors.

For instance, a 2015 study suggests that folks living with ADHD who experience hallucinations or hear voices may be linked to the use of illegal drugs, particularly at a young age.

Similar to ADHD, those who live with schizophrenia may experience difficulty:

- thinking clearly

- controlling their emotions

- connecting socially with others

Differences

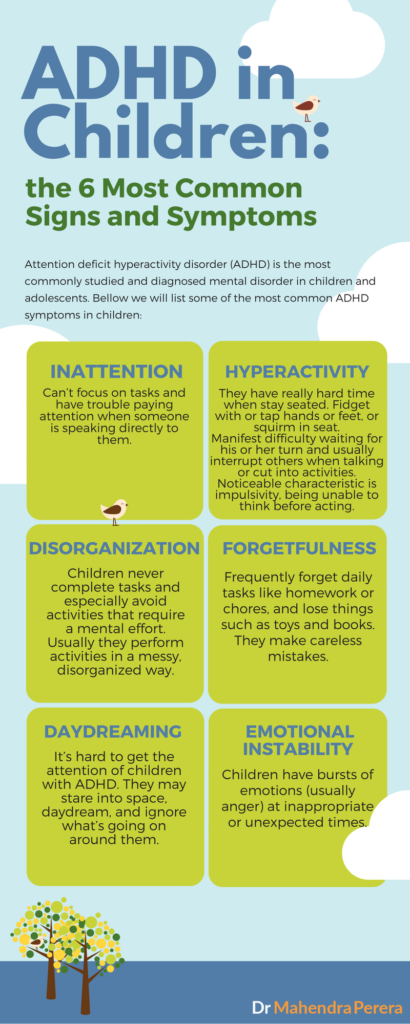

ADHD may impact a person’s productivity at work or school due to:

- difficulty concentrating

- hyperactivity

- impulsive behaviors

Hyperactivity may fade as a person diagnosed with ADHD grows older, but inattention and impulsivity may continue.

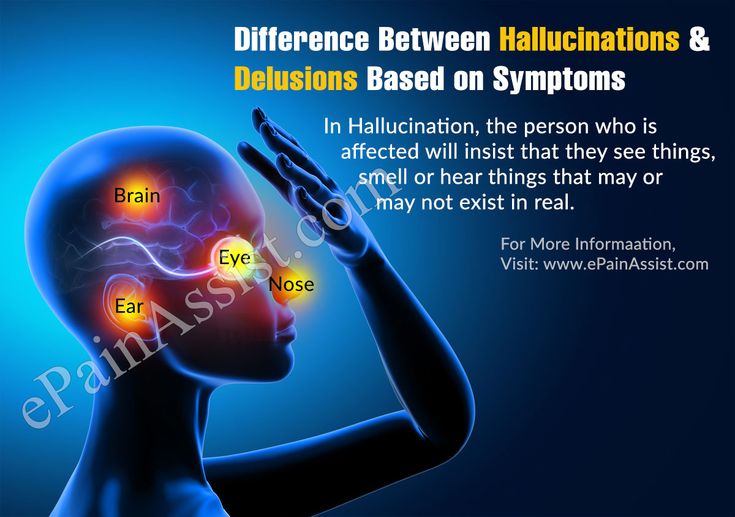

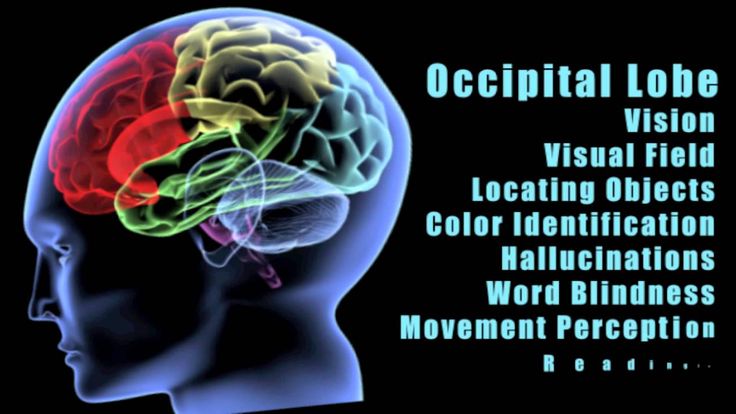

Schizophrenia may cause hallucinations, delusions, and disorganized thinking, among other symptoms that impact a person’s life, similar to depression.

Causes

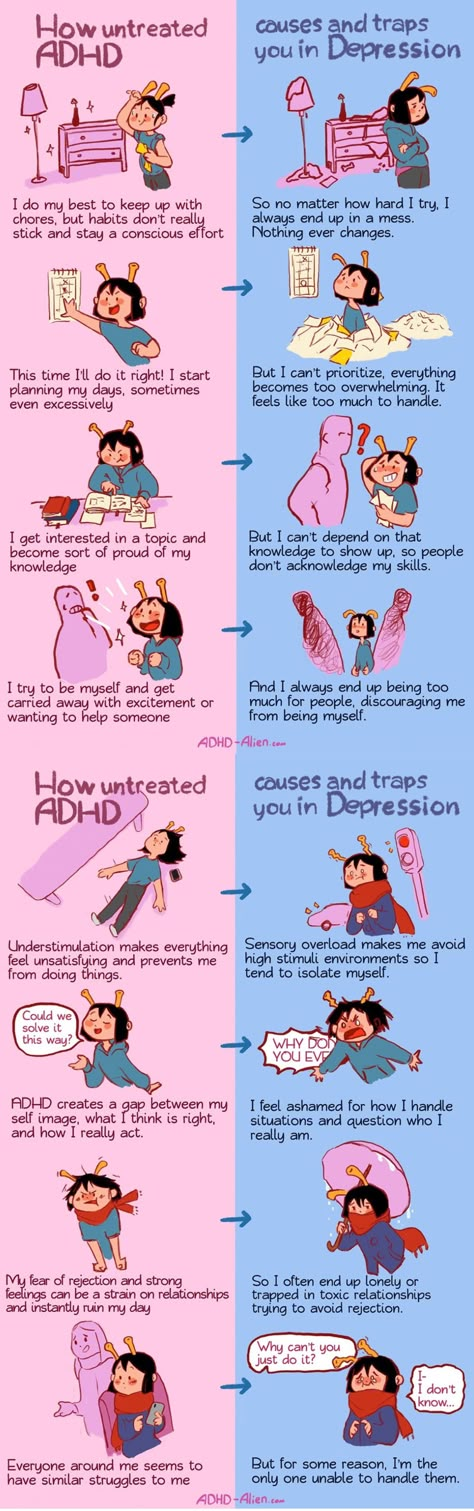

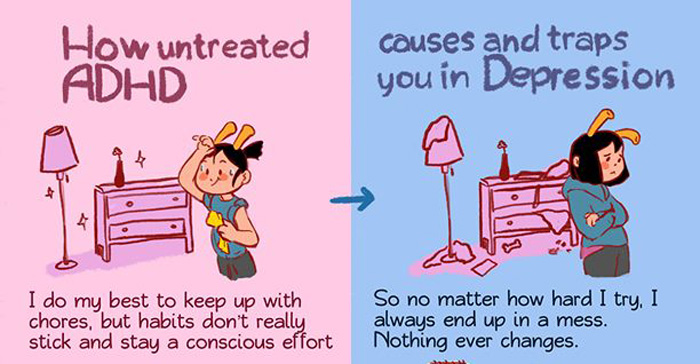

Although there may be a connection between ADHD and schizophrenia, a diagnosis of one doesn’t necessarily determine the other. And untreated ADHD doesn’t always lead to psychosis.

Similarities

Research from 2013 shows that people with close relatives with ADHD may have a higher chance of being diagnosed with schizophrenia.

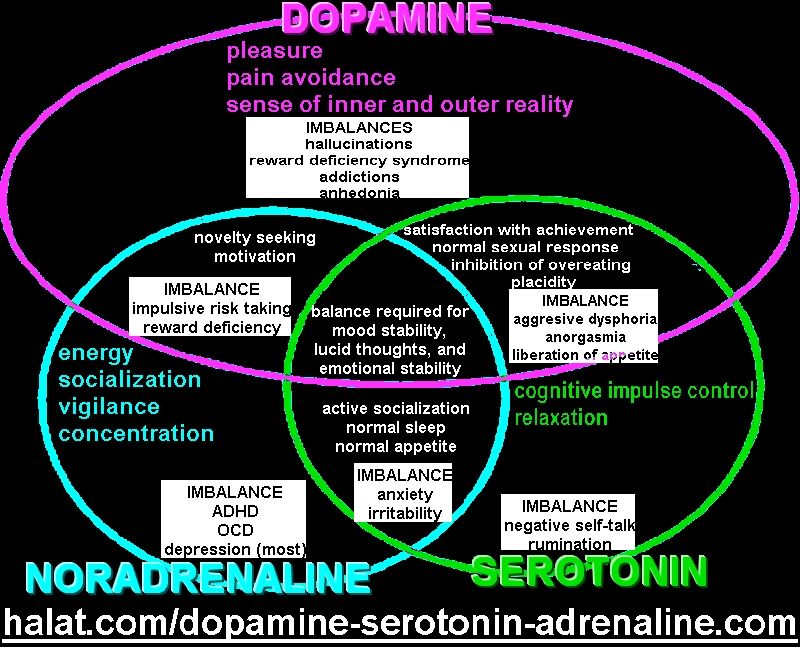

Dopamine is also thought to be a factor in ADHD and schizophrenia. As a neurotransmitter (or brain chemical), dopamine may affect your:

- attention

- focus

- pleasure

- happiness

- motivation

In addition, other research from 2013 suggests there may be perinatal risk factors involved in both conditions. These include:

- low birth weight

- premature birth

- pregnancy complications

Differences

Although the causes of ADHD are not fully understood, research from 2013 suggests that ADHD may be caused by:

- smoking

- genetic factors

- exposure to environmental toxins (at a younger age)

There aren’t any clear causes for schizophrenia, but genetics play a more significant role than ADHD.

For instance, a 2017 study suggests that schizophrenia is six times more likely to be diagnosed when there is a close family member with the condition.

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), other possible risk factors for developing schizophrenia may include:

- environmental exposure

- substance use (especially during adolescence)

Diagnosis and treatments

ADHD and schizophrenia have different diagnostic criteria, with some overlap in how they’re clinically treated.

Similarities

ADHD and schizophrenia require multiple tests to rule out other conditions before a diagnosis can be made.

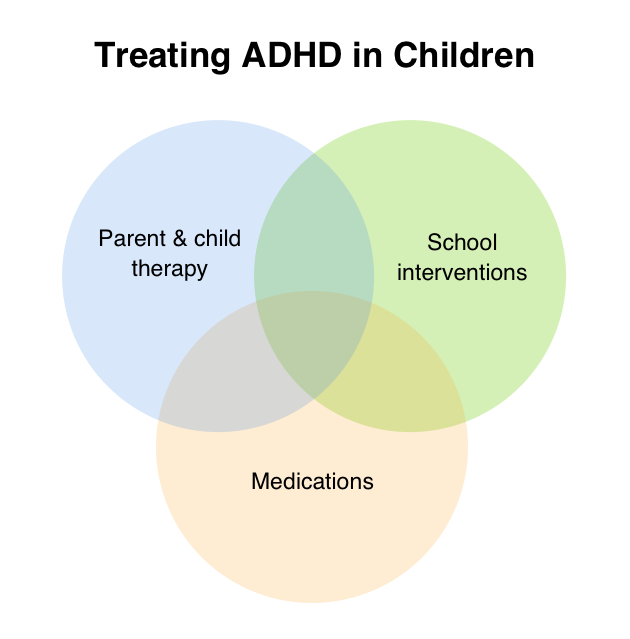

Those living with ADHD or schizophrenia could benefit from cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and support groups.

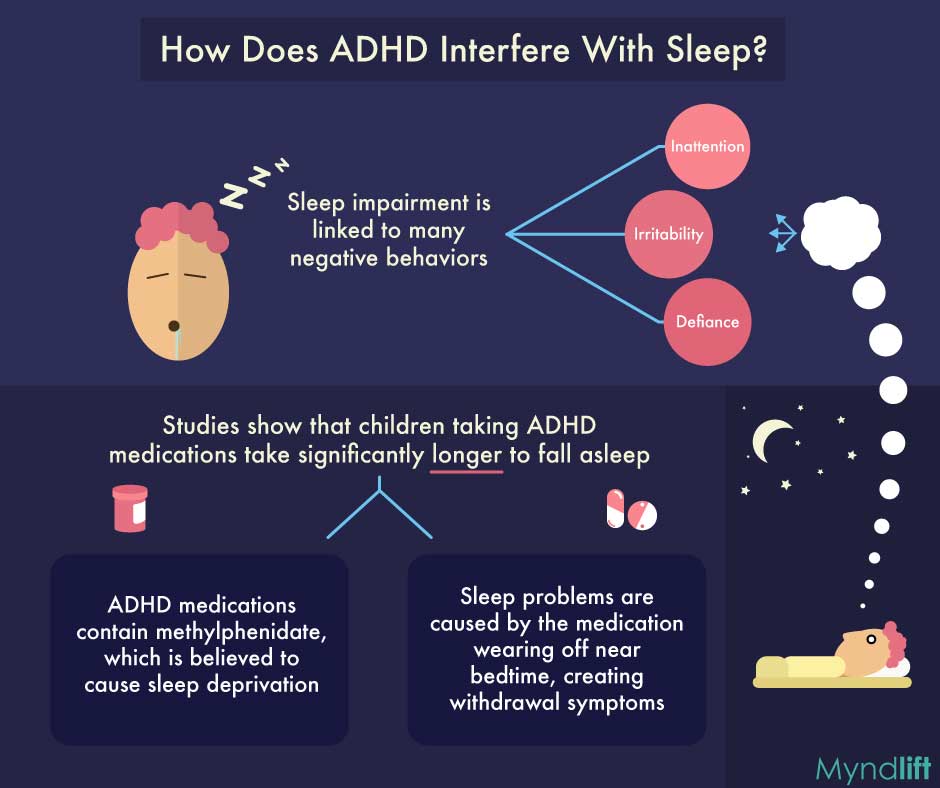

Those navigating either condition may also benefit from regimented schedules and sleep hygiene.

Differences

ADHD is often diagnosed in childhood, while schizophrenia is often detected in your 20s or 30s.

ADHD can be treated with behavioral therapy, while schizophrenia can be managed with cognitive emotional therapy (CET).

ADHD does not have to be medicated, but a doctor may prescribe a stimulant to help with focus. Schizophrenia may be treated with antipsychotic medication if needed.

Schizophrenia may be treated with antipsychotic medication if needed.

According to NAMI, suggestions for managing schizophrenia include:

- managing your stress, as stress can trigger psychosis

- maintaining your personal connections

- considering involving loved ones in your treatment or crisis safety plan

- avoiding substances, as they have the potential to interact with your medication

For children with ADHD, helpful suggestions may include:

- seeking a family counselor to assist your child’s social development

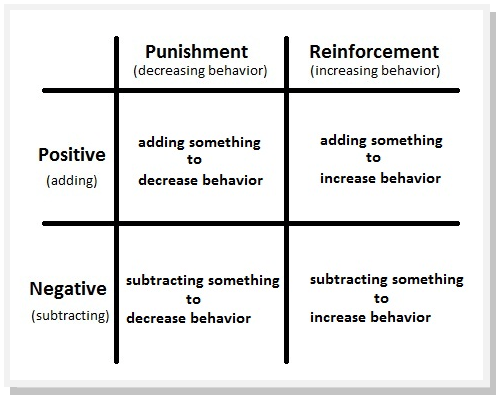

- engaging in parenting skills training to learn positive reinforcement techniques

- connecting with your child’s school to determine whether an educational intervention or accommodation would be helpful

For adults with ADHD, creating reasonable routines alongside easy ways to stay organized may help you stay on top of things. Consider the following:

- creating lists for your to-dos

- keeping your calendar up-to-date

- setting reminders in your phone

While there is no cure for ADHD or schizophrenia, the symptoms associated with both conditions can be managed.

Regardless of your diagnosis, it’s still possible to live a full life while managing your symptoms and treatments.

If you’ve recently been diagnosed with ADHD or schizophrenia and are looking for one-on-one support, you may wish to connect with a mental health professional who specializes in CBT. A qualified therapist can help you with your next steps and ensure you’re set up for success.

Adult attention deficit hyperactivity symptoms and psychosis: Epidemiological evidence from a population survey in England

. 2015 Sep 30;229(1-2):49-56.

doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.075. Epub 2015 Jul 28.

Steven Marwaha 1 , Andrew Thompson 2 , Paul Bebbington 3 , Swaran P Singh 2 , Daniel Freeman 4 , Catherine Winsper 2 , Matthew R Broome 5

Affiliations

Affiliations

- 1 Division of Mental Health and Wellbeing, Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick, Coventry CV47AL, UK; Early Intervention Service, Swanswell Point, Coventry CV14FH, UK.

Electronic address: [email protected].

Electronic address: [email protected]. - 2 Division of Mental Health and Wellbeing, Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick, Coventry CV47AL, UK.

- 3 Division of Psychiatry, University College London, 67-73 Riding House St., London W1W 7EJ, UK.

- 4 Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford, OX3 4JX, UK.

- 5 Division of Mental Health and Wellbeing, Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick, Coventry CV47AL, UK; Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford, OX3 4JX, UK; Highfield Adolescent Unit, Warneford Hospital, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford OX3 7JX, UK.

- PMID: 26235475

- DOI: 10.

1016/j.psychres.2015.07.075

1016/j.psychres.2015.07.075

Steven Marwaha et al. Psychiatry Res. .

. 2015 Sep 30;229(1-2):49-56.

doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.075. Epub 2015 Jul 28.

Authors

Steven Marwaha 1 , Andrew Thompson 2 , Paul Bebbington 3 , Swaran P Singh 2 , Daniel Freeman 4 , Catherine Winsper 2 , Matthew R Broome 5

Affiliations

- 1 Division of Mental Health and Wellbeing, Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick, Coventry CV47AL, UK; Early Intervention Service, Swanswell Point, Coventry CV14FH, UK.

Electronic address: [email protected].

Electronic address: [email protected]. - 2 Division of Mental Health and Wellbeing, Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick, Coventry CV47AL, UK.

- 3 Division of Psychiatry, University College London, 67-73 Riding House St., London W1W 7EJ, UK.

- 4 Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford, OX3 4JX, UK.

- 5 Division of Mental Health and Wellbeing, Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick, Coventry CV47AL, UK; Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford, OX3 4JX, UK; Highfield Adolescent Unit, Warneford Hospital, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford OX3 7JX, UK.

- PMID: 26235475

- DOI: 10.

1016/j.psychres.2015.07.075

1016/j.psychres.2015.07.075

Abstract

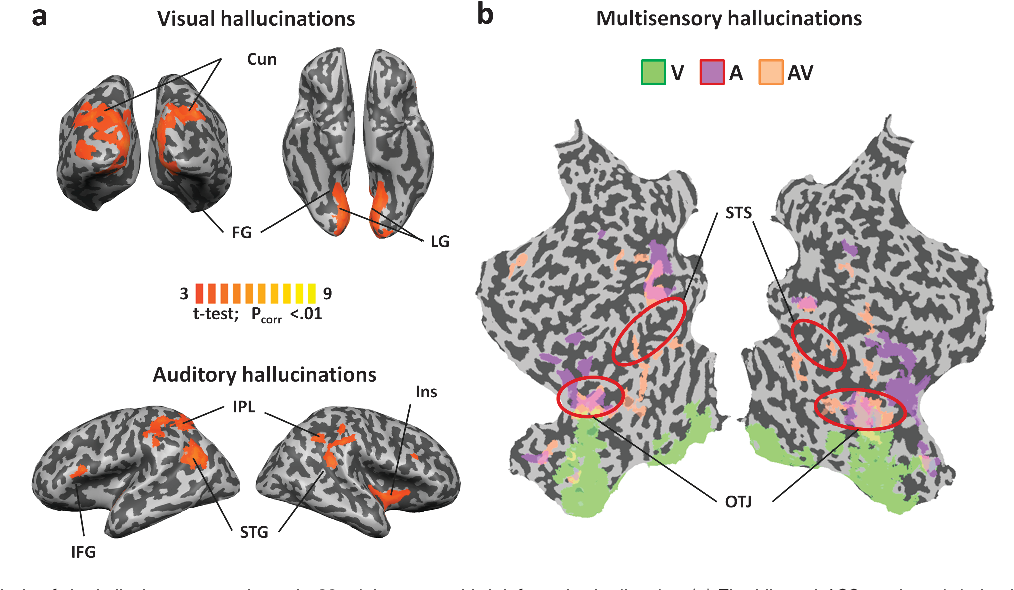

Despite both having some shared features, evidence linking psychosis and adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is sparse and inconsistent. Hypotheses tested were (1) adult ADHD symptoms are associated with auditory hallucinations, paranoid ideation and psychosis (2) links between ADHD symptoms and psychosis are mediated by prescribed ADHD medications, use of illicit drugs, and dysphoric mood. The Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2007 (N=7403) provided data for regression and multiple mediation analyses. ADHD symptoms were coded from the ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS). Higher ASRS total score was significantly associated with psychosis, paranoid ideation and auditory hallucinations despite controlling for socio-demographic variables, verbal IQ, autism spectrum disorder traits, childhood conduct problems, hypomanic and dysphoric mood. An ASRS score indicating probable ADHD diagnosis was also significantly associated with psychosis. The link between higher ADHD symptoms and psychosis, paranoia and auditory hallucinations was significantly mediated by dysphoric mood, but not by use of amphetamine, cocaine or cannabis. In conclusion, higher levels of adult ADHD symptoms and psychosis are linked and dysphoric mood may form part of the mechanism. Our analyses contradict the traditional clinical view that the main explanation for people with ADHD symptoms developing psychosis is illicit drugs.

An ASRS score indicating probable ADHD diagnosis was also significantly associated with psychosis. The link between higher ADHD symptoms and psychosis, paranoia and auditory hallucinations was significantly mediated by dysphoric mood, but not by use of amphetamine, cocaine or cannabis. In conclusion, higher levels of adult ADHD symptoms and psychosis are linked and dysphoric mood may form part of the mechanism. Our analyses contradict the traditional clinical view that the main explanation for people with ADHD symptoms developing psychosis is illicit drugs.

Keywords: ADHD; Cannabis; Cocaine; Depression; Psychosis.

Copyright © 2015 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved.

Similar articles

-

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, other mental health problems, substance use, and driving: examination of a population-based, representative canadian sample.

Vingilis E, Mann RE, Erickson P, Toplak M, Kolla NJ, Seeley J, Jain U. Vingilis E, et al. Traffic Inj Prev. 2014;15 Suppl 1:S1-9. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2014.926341. Traffic Inj Prev. 2014. PMID: 25307372

-

Mood instability and psychosis: analyses of British national survey data.

Marwaha S, Broome MR, Bebbington PE, Kuipers E, Freeman D. Marwaha S, et al. Schizophr Bull. 2014 Mar;40(2):269-77. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt149. Epub 2013 Oct 25. Schizophr Bull. 2014. PMID: 24162517 Free PMC article.

-

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and happiness among adults in the general population.

Stickley A, Koyanagi A, Takahashi H, Ruchkin V, Inoue Y, Yazawa A, Kamio Y. Stickley A, et al.

Psychiatry Res. 2018 Jul;265:317-323. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.05.004. Epub 2018 May 5. Psychiatry Res. 2018. PMID: 29778053

Psychiatry Res. 2018 Jul;265:317-323. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.05.004. Epub 2018 May 5. Psychiatry Res. 2018. PMID: 29778053 -

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and comorbid psychosis: a review and two clinical presentations.

Pine DS, Klein RG, Lindy DC, Marshall RD. Pine DS, et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993 Apr;54(4):140-5. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993. PMID: 8098031 Review.

-

Comorbidity and its impact in adult patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a primary care perspective.

Babcock T, Ornstein CS. Babcock T, et al. Postgrad Med. 2009 May;121(3):73-82. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2009.05.2005. Postgrad Med. 2009. PMID: 19491543 Review.

See all similar articles

Cited by

-

Assessment of Attentional Processes in Patients with Anxiety-Depressive Disorders Using Virtual Reality.

Camacho-Conde JA, Legarra L, Bolinches VM, Cano P, Guasch M, Llanos-Torres M, Serret V, Mejías M, Climent G. Camacho-Conde JA, et al. J Pers Med. 2021 Dec 9;11(12):1341. doi: 10.3390/jpm11121341. J Pers Med. 2021. PMID: 34945813 Free PMC article.

-

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in youth with psychosis spectrum symptoms.

Fox V, Sheffield JM, Woodward ND. Fox V, et al. Schizophr Res. 2021 Nov;237:141-147. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2021.08.027. Epub 2021 Sep 13. Schizophr Res. 2021. PMID: 34530253 Free PMC article.

-

Self-harm, suicidal ideation, and the positive symptoms of psychosis: Cross-sectional and prospective data from a national household survey.

de Cates AN, Catone G, Marwaha S, Bebbington P, Humpston CS, Broome MR.

de Cates AN, et al. Schizophr Res. 2021 Jul;233:80-88. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2021.06.021. Epub 2021 Jul 7. Schizophr Res. 2021. PMID: 34246091 Free PMC article.

de Cates AN, et al. Schizophr Res. 2021 Jul;233:80-88. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2021.06.021. Epub 2021 Jul 7. Schizophr Res. 2021. PMID: 34246091 Free PMC article. -

Lifetime co-occurring psychiatric disorders in newly diagnosed adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or/and autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

Pehlivanidis A, Papanikolaou K, Mantas V, Kalantzi E, Korobili K, Xenaki LA, Vassiliou G, Papageorgiou C. Pehlivanidis A, et al. BMC Psychiatry. 2020 Aug 26;20(1):423. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02828-1. BMC Psychiatry. 2020. PMID: 32847520 Free PMC article.

-

Symptom Overlap and Screening for Symptoms of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Psychosis Risk in Help-Seeking Psychiatric Patients.

Corbisiero S, Riecher-Rössler A, Buchli-Kammermann J, Stieglitz RD.

Corbisiero S, et al. Front Psychiatry. 2017 Oct 30;8:206. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00206. eCollection 2017. Front Psychiatry. 2017. PMID: 29163233 Free PMC article.

Corbisiero S, et al. Front Psychiatry. 2017 Oct 30;8:206. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00206. eCollection 2017. Front Psychiatry. 2017. PMID: 29163233 Free PMC article.

See all "Cited by" articles

Publication types

MeSH terms

Substances

Grant support

- G0902308/Medical Research Council/United Kingdom

Risk of psychosis in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

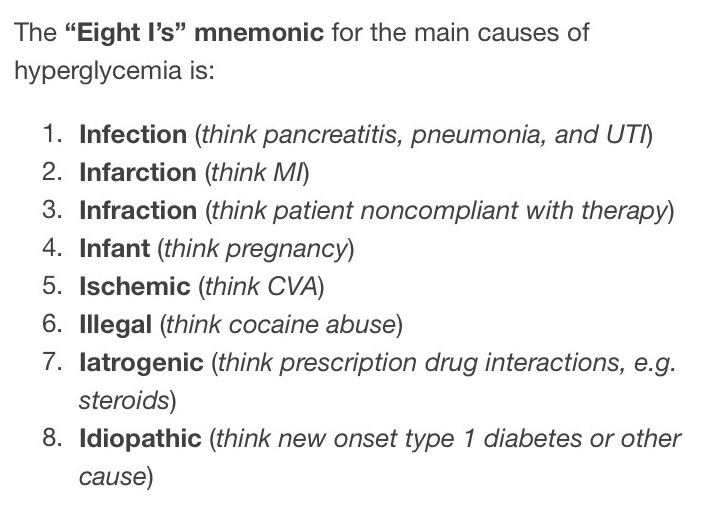

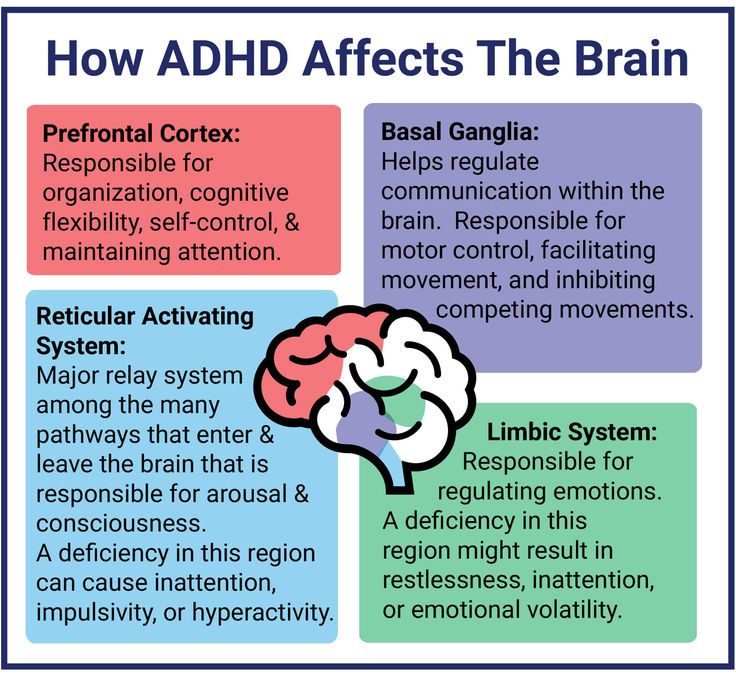

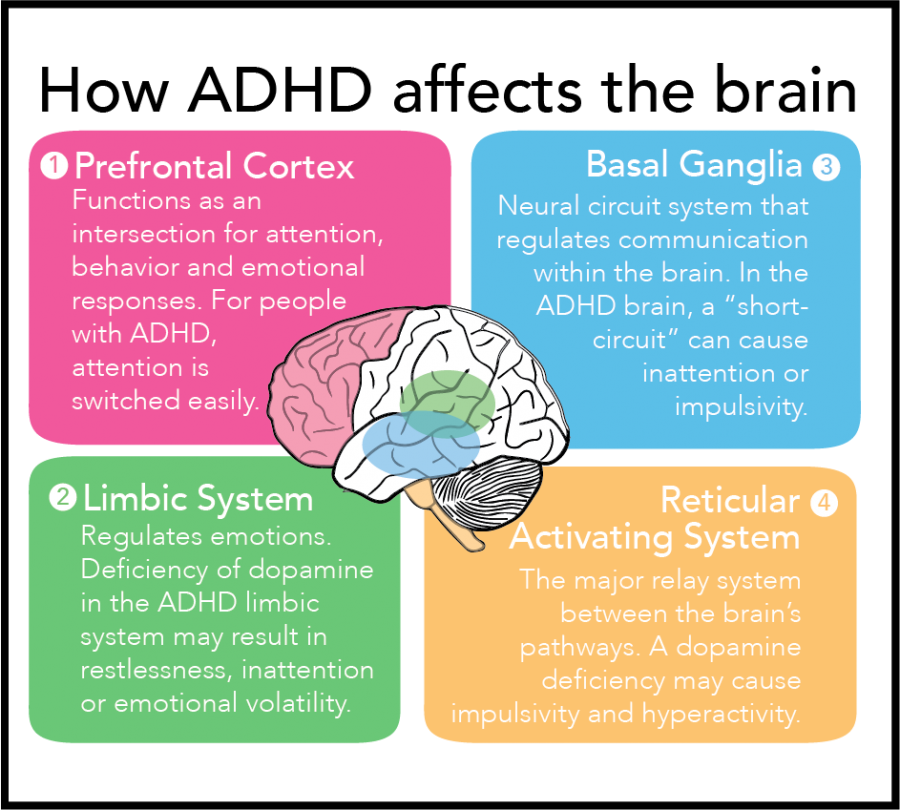

Longitudinal studies have demonstrated that attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a risk factor for the development of psychosis in adulthood. Most often, it is provoked by drugs from the group of central stimulants. As indirect dopamine agonists, these drugs increase the concentration of neurotransmitters in the intercellular space in the prefrontal cortex, which may be the cause of psychotic symptoms.

As indirect dopamine agonists, these drugs increase the concentration of neurotransmitters in the intercellular space in the prefrontal cortex, which may be the cause of psychotic symptoms.

This is very important for clinicians to consider when prescribing therapy. International guidelines recommend methylphenidate and dexamphetamine as first-line therapy for ADHD. According to UK Medicines and Healthcare Products, out of 1335 cases of methylphenidate side effects, 663 were associated with psychiatric symptoms. Of these, 105 patients reported the occurrence of hallucinations, the development of schizoaffective states. In addition, a review of 49 randomized controlled trials conducted by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on the effects of central stimulants on children showed that they develop symptoms of psychosis and mania.

Some doctors believe that stimulants are contraindicated in patients who have experienced psychosis. Every time doctors face a dilemma between following scientific advances in the treatment of ADHD and the benefits of this therapy. This is especially true in cases where the patient has already experienced psychosis.

This is especially true in cases where the patient has already experienced psychosis.

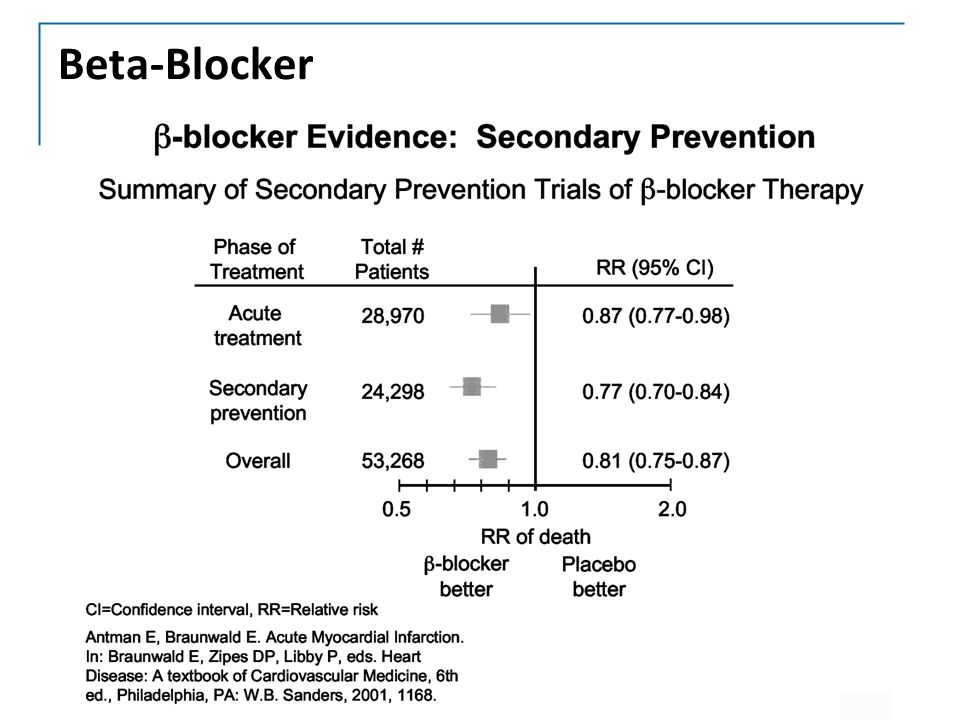

In June 2019, a population-based study by Swedish authors on methylphenidate and the risk of developing psychosis in adolescence and early adulthood was published in The Lancet Psychiatry in June 2019. The authors attempted to understand whether methylphenidate increases the risk of developing psychosis in patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) with and without a psychotic experience. Using the national database (Swedish national registers), they selected 23898 respondents and checked their condition 12 weeks before, 12 weeks after and one year after the start of methylphenidate therapy. The results of this work demonstrated that, both in the short and long term, methylphenidate does not cause the onset of psychotic symptoms in patients with any psychotic experience, and, on the contrary, contributes to their prevention in those who had psychosis before ADHD therapy.

However, this study had some limitations. First, the authors do not specify whether respondents who had experienced psychosis in the past took antipsychotics during treatment with methylphenidate. After all, antipsychotics could prevent the development of secondary, drug-induced, psychosis.

Second, the authors do not report patient compliance with methylphenidate treatment. There are long-term follow-up studies showing that adherence to ADHD treatment declines significantly in late adolescence and early adulthood. Less than 10% of patients continue treatment with stimulant drugs started in childhood. In addition, the ability of this category of patients to comply is highly variable. Some patients, for example, use drugs only during exams and deadlines.

Third, high doses of psychostimulants can cause psychotic symptoms, which is not the case when used at therapeutic doses. Perhaps, in this study, methylphenidate was prescribed in such an amount that it could not provoke psychosis. The dose effect was demonstrated in the 2014 work by Chammas M., Ahronheim G.A., Hechtman L., where the authors re-prescribed psychostimulants to patients with ADHD who had undergone psychosis. As a result, they observed that the gradual titration of long-acting forms of methylphenidate and amphetamine preparations after a certain period of time (from 1 to 6 months) after the cessation of stimulant use (which was the cause of the onset of psychotic symptoms), contributed to the relief of psychosis.

The dose effect was demonstrated in the 2014 work by Chammas M., Ahronheim G.A., Hechtman L., where the authors re-prescribed psychostimulants to patients with ADHD who had undergone psychosis. As a result, they observed that the gradual titration of long-acting forms of methylphenidate and amphetamine preparations after a certain period of time (from 1 to 6 months) after the cessation of stimulant use (which was the cause of the onset of psychotic symptoms), contributed to the relief of psychosis.

Fourth, in this study, the authors only looked at the effects of methylphenidate, as it is the most commonly used treatment for ADHD in Sweden. In a 2019 study by Moran L. V., Ongur D., Hsu J., Castro V. M., Perlis R. H., Schneeweiss, S., in which 110,924 people took part, it was found that amphetamine causes psychosis more often than methylphenidate.

Overall, this study supports the notion that methylphenidate does not affect the risk of developing psychosis in young people with ADHD, both those with a history of psychosis and those who have not. But it had some limitations. For example, it remained unclear whether antipsychotic therapy was prescribed, what was the dosage of methylphenidate, and whether patients took medication regularly. For survivors of psychosis, ADHD treatment with stimulants should be done by slowly increasing the dosage of the drugs. It is preferable to use methylphenidate. If necessary, such therapy can be supplemented with antipsychotics.

But it had some limitations. For example, it remained unclear whether antipsychotic therapy was prescribed, what was the dosage of methylphenidate, and whether patients took medication regularly. For survivors of psychosis, ADHD treatment with stimulants should be done by slowly increasing the dosage of the drugs. It is preferable to use methylphenidate. If necessary, such therapy can be supplemented with antipsychotics.

In individuals who have never had psychosis, ADHD is also best treated by titration. In addition, patients should be informed of the risk of psychotic symptoms and that abrupt increases in the dose of stimulant medications can be dangerous.

Translated by K. O. Wirth

Sources:

Lily Hechtman. ADHD medication treatment and risk of psychosis. The Lancet Psychiatry.

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpsy/article/PIIS2215-0366(19)30248-2/fulltext

Chris Hollis, Qi Chen, Zheng Chang, Patrick D Quinn, Alexander Viktorin, Paul Lichtenstein, Brian D'Onofrio, Mikael Landén, Henrik Larsson. Methylphenidate and the risk of psychosis in adolescents and young adults: a population-based cohort study. The Lancet Psychiatry.

Methylphenidate and the risk of psychosis in adolescents and young adults: a population-based cohort study. The Lancet Psychiatry.

https://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lanpsy/PIIS2215-0366(19)30189-0.pdf

Autism and Mental Health | Exit Foundation, autism in Russia

04.05.17

Review of studies on the prevalence and treatment of mental disorders in autism

Source: autism Speaks

Epidemiological studies suggest that from 54% to 70% of people with autism have one thing or more mental disorders (Simonoff 2008, Hofvander 2009, Croen 2015, Romero 2016).

With regard to their prevalence, the following data currently exist:

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) occurs in 30-61% of people with autism (Goldstein 2004, Lee 2006, Gadow 2006, Romero 2016).

- Anxiety disorders affect 11-42% of people with autism (Vasa 2016, White 2009, Croen 2015, Romero 2016).

- Depression affects 7% of children and 26% of adults with autism (Greenlee 2016, Croen 2015).

- Schizophrenia occurs in 4-35% of adults with autism (Chisolm 2015).

- Bipolar affective disorder occurs in 6-27% of people with autism (Munesue 2008, Rosenberg 2011, Vannucchi 2014, Guinchat 2015, Croen 2015).

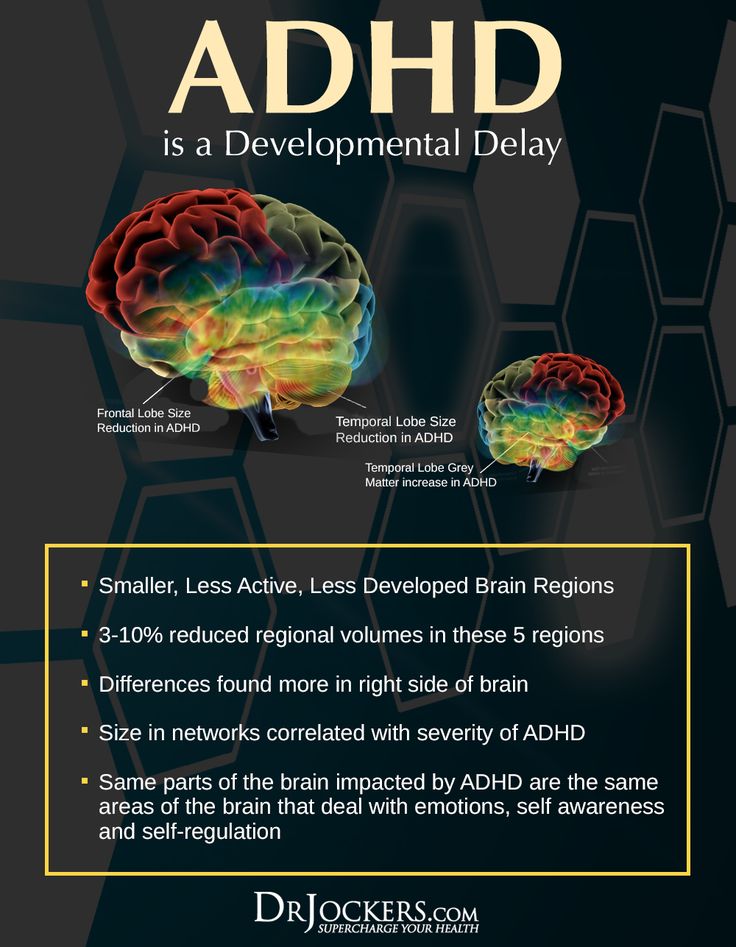

ADHD, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, like autism, are caused by neurobiological features of the brain that are associated with the earliest stages of its development (Munesue 2008, Sikora 2012, Rapoport 2012). As for anxiety disorders and depression, at least in part, they may be related to daily stress, social isolation, and poor overall quality of life among people with autism (Vasa 2016, Greenlee 2016).

Left untreated, psychiatric disorders can lead to a dramatic worsening of behavioral problems in autism. However, due to similar symptoms, the diagnosis of such disorders in autism can be very difficult (Levy 2010, Sikora 2012, Miodovnik 2015). For example, social avoidance in depression or schizophrenia is difficult to distinguish from social interaction disorders associated with autism. In addition, people with autism may find it difficult to identify or express their emotions and other inner experiences.

For example, social avoidance in depression or schizophrenia is difficult to distinguish from social interaction disorders associated with autism. In addition, people with autism may find it difficult to identify or express their emotions and other inner experiences.

Over the past few years, autism specialists have developed guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of some of the most common mental disorders in children, adolescents and adults with autism. The following is an overview of the latest data on this topic.

Autism and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

Over the past ten years, studies have shown that 30% to 61% of people with autism also have symptoms of ADHD (Goldstein 2004, Lee 2006, Gadow 2006, Romero 2016). In comparison, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that ADHD occurs in 6-7% of the general population (Perou 2013).

In addition, geneticists have discovered that many genetic variations that increase the risk of autism also increase the risk of ADHD (Lionel 2011).

Symptoms of ADHD include consistent problems with inattention, hyperactivity, and/or impulsivity that interfere with daily living, social development, and learning. People with ADHD often find it difficult to pay attention to details and make many mistakes at school or at work through sheer inattention. They often do not seem to hear when spoken to and find it difficult to organize their activities, follow instructions and complete tasks, especially when they require concentration (DSM-5 2013).

In 2012, a study of ADHD symptoms was conducted among 3,000 autistic patients aged 2 to 18 years (Sikora 2012). Multiple symptoms of ADHD have been found in more than half of children and adolescents with autism. Further evaluation showed that the combination of ADHD and autism results in poorer daily functioning, health, and overall quality of life. At the same time, only a few of these children (11%) received ADHD treatment.

Differentiating autism and ADHD can be especially tricky because both disorders involve social interaction problems and difficulties with attention, learning, and communication.

In 2012 Pediatrics published the first guidelines for diagnosing ADHD in children and adolescents with autism, along with guidelines for selecting and evaluating ADHD medications for these patients (Mahajan 2012). The guide also provides information about the benefits and side effects of ADHD medications and their dosages in consultation with the family.

The guidelines emphasize that the decision to use drugs is very personal and should be made in consultation with the individual and/or their parents in accordance with their goals and values.

Autism and anxiety disorders

Research suggests that 11% to 42% of people with autism suffer from one or more anxiety disorders (Vasa 2016, White 2009, Croen 2015, Romero 2016). By comparison, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 3% of children and 15% of adults in the general population have anxiety disorders (Perou 2013, Kessler 2009). These disorders include parental separation anxiety, panic disorder, and phobias (extremely intense fear of certain sounds, places, and so on).

Social anxiety—an extreme fear of new people, crowds, and social situations—is very common in children and adults with autism. Many children on the autism spectrum experience an increase in anxiety during adolescence (Bellini 2006). Although there is still very little research in adults with autism, case reports suggest that high levels of anxiety often persist throughout the life of an individual with autism (Gillott 2007, Moss 2015).

Even in the absence of an anxiety disorder, many people with autism have trouble controlling their anxiety if something triggers it. For many, anxiety is closely associated with symptoms of autism, especially difficulty in social situations and increased sensory sensitivity to loud noises, lights, tastes or smells. Problems like these can lead to a special form of anxiety where the mere thought or expectation of an anxiety-provoking situation can cause extreme anxiety.

Another important source of anxiety for people with autism is their need for routine and sameness. Changes in the daily routine or meeting strangers can cause very strong anxiety, for example, if you suddenly have to deal with a new teacher, a new tutor, or even an unfamiliar salesman.

Changes in the daily routine or meeting strangers can cause very strong anxiety, for example, if you suddenly have to deal with a new teacher, a new tutor, or even an unfamiliar salesman.

To date, most research on anxiety in autism has been conducted in verbal children and adults with normal or high intelligence. Experts agree that more research is needed on anxiety among nonverbal or minimally verbal people, which includes one in three people with autism and/or those with an intellectual disability.

Diagnosis and treatment of anxiety in autism

In 2016, the journal Pediatrics published the first guide to diagnosing and treating anxiety in people with autism (Vasa 2016). Since it is difficult for people with autism to understand and express how they feel, very often the presence of increased anxiety must be determined by behavioral signs. Anxiety can cause severe internal sensations, including increased heart rate, muscle tension, and abdominal pain. For a person with autism, these sensations can cause an increase in repetitive self-soothing behaviors (hand shaking, rocking, spinning, etc. ) and/or destructive or self-aggressive behaviors (clothes tearing, head banging on the floor, etc.). Similarly, anxiety can be the reason why a person began to resist and refuse activities that he used to enjoy (going to the beach, birthday party, school, and so on).

) and/or destructive or self-aggressive behaviors (clothes tearing, head banging on the floor, etc.). Similarly, anxiety can be the reason why a person began to resist and refuse activities that he used to enjoy (going to the beach, birthday party, school, and so on).

The guidelines call for personalized treatment based on the patient's developmental level, including speech and intellectual development. Data are also provided on the effectiveness of a version of cognitive behavioral therapy adapted for people with autism (Wood 2009, Drahota 2011, Wood 2015). In general, cognitive-behavioral techniques include challenging negative thoughts with logic, role-playing situations, modeling bold behavior, and gradually dealing with fearful situations. Gradual contact can begin by simply looking at a photograph of the situation. A version of psychotherapy adapted for people with autism uses many visual cues that suit the visual learning style of many people with autism. This version also uses the special interests of people with autism to increase their involvement in the psychotherapy process. For example, a therapist might use a child's favorite cartoon character to model how to deal with a fearful situation. Another example is during a therapy session, the therapist takes breaks to talk to the client about a special interest.

For example, a therapist might use a child's favorite cartoon character to model how to deal with a fearful situation. Another example is during a therapy session, the therapist takes breaks to talk to the client about a special interest.

Some people with autism really enjoy the logical aspects of CBT. In clinical trials, cognitive behavioral therapy has proven effective for verbal people on the autism spectrum with normal to high intelligence (Wood 2009, Wood 2015, Hepburn 2016). Researchers are now working to further modify this approach to suit people with intellectual disabilities and/or speechlessness (Danial 2013).

Anti-anxiety medications for people with autism

In some cases, counseling and behavioral therapy are not enough to relieve severe anxiety. In these cases, the patient and/or family may consult with a qualified healthcare professional about adding an anti-anxiety drug to the treatment program. There are no medications approved specifically for the treatment of anxiety in children and adults with autism. Autism specialists typically prescribe the same drugs that have been approved for treating anxiety disorders in the general population. These include serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as Prozac and Zoloft. However, some research suggests that anti-anxiety medications may be less effective for people with autism than for other groups (Williams 2010). Perhaps the reason is that the causes of anxiety in autism differ from those in the general population.

Autism specialists typically prescribe the same drugs that have been approved for treating anxiety disorders in the general population. These include serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as Prozac and Zoloft. However, some research suggests that anti-anxiety medications may be less effective for people with autism than for other groups (Williams 2010). Perhaps the reason is that the causes of anxiety in autism differ from those in the general population.

Autism and depression

An estimated 7% of children with autism and 26% of adults with autism have depression (Greenlee 2016, Croen 2015). By comparison, 2% of children and 7% of adults in the general population in the US have depression (Perou 2013, NIMH 2015). A recent report in the journal Pediatrics found that rates of depression among children with autism increase rapidly with age, from 5% in elementary grades to over 20% in adolescents (Greenlee 2016). It is assumed that the risk of depression is higher with higher intellectual abilities, as well as with one or more associated medical problems, primarily epilepsy and digestive problems.

The fact that levels of depression increase with age and intellectual ability suggests that painful awareness of social difficulties due to autism and isolation may be the cause of depression, the researchers note. The fact that the level of depression increases with comorbid medical problems suggests how these problems affect the quality of life in autism.

The authors urge healthcare professionals to consider standard screening for symptoms of depression for all adolescents and adults with autism, especially if they have normal or high intelligence or additional medical problems.

Diagnosis of depression in autism

Signs and symptoms of depression include chronic feelings of sadness, hopelessness, worthlessness, inner emptiness and/or irritability. Also common: social isolation, slowness of movement or speech, restlessness, difficulty concentrating or sitting still. In the most severe cases, depression may include frequent thoughts of death and/or suicide.

However, diagnosing depression in people with autism can be particularly difficult (Gotham 2015). A flat, emotionless facial expression, for example, is characteristic of both autism and depression. The same applies to irritability and social isolation. As a result, it can be difficult to recognize depression behind the manifestations of autism. In addition, many people with autism find it very difficult to identify and express their feelings. For these reasons, autism professionals have begun working to develop and test modified methods for diagnosing depression in children and adolescents on the autism spectrum (Sterling 2015).

Depression, autism, and suicide

In 2012, researchers at the Penn College of Medicine reported that 14% of children with autism under the age of 16 "sometimes" or "very often" thought or tried to commit suicide - that's 28 times more likely than than children of the same age with typical development (Mayes 2013). The increase in suicidal tendencies becomes significant after 10 years of age, and was most associated with depressive symptoms. Neither the severity of autism nor the level of intelligence affected this level. The authors of the study urge medical professionals to screen all children with autism for suicidal thoughts and attempts, and to inform parents about such risks.

Neither the severity of autism nor the level of intelligence affected this level. The authors of the study urge medical professionals to screen all children with autism for suicidal thoughts and attempts, and to inform parents about such risks.

Treating depression in people with autism

Cognitive behavioral therapy may well be successful in treating depression in adolescents and adults with autism (Kuroda 2013). These findings are based on a large body of research on the effectiveness of a modified version of cognitive behavioral therapy for extreme and chronic anxiety in autism.

There are no drugs approved to treat depression specifically in patients with autism, so usually psychiatrists prescribe the same drugs for people with autism as for other patients. However, more research is needed, as a 2011 study suggests that antidepressant side effects are more common among people with autism (Boyd 2011). The most common side effects are drowsiness, nervous agitation, increased irritability, increased motor activity and digestive problems.

Autism and Schizophrenia

In the 1960s, psychiatrists mistakenly believed that autism was a form of childhood schizophrenia (DSM II 1968). However, by the 1990s, psychiatry had made a clear distinction between these disorders (Rapoport 2009).

Although autism and schizophrenia are distinct disorders, they share biological characteristics. The roots of both disorders seem to be related to the development of the child's brain even before birth. The same factors are associated with an increased risk of both autism and schizophrenia. These include infectious and inflammatory diseases of the mother during pregnancy, as well as the age of both parents at the time of conception (Patterson 2009, Menon 2011, Insel 2010). Research has also identified many genetic risk factors for both disorders. In other words, there are many genetic variations that can increase the risk of both autism and schizophrenia (Guilmatre 2009, McCarthy 2014).

Autism and schizophrenia also have similar symptoms, for example, with both disorders, it can be difficult for a person to understand speech, as well as understand the thoughts and feelings of other people. The most obvious difference between schizophrenia and autism is psychosis, which usually includes hallucinations. In addition, the main symptoms of autism always appear very early - autism can be diagnosed between the ages of 1 and 3 years. The symptoms of schizophrenia usually appear in young adults.

The most obvious difference between schizophrenia and autism is psychosis, which usually includes hallucinations. In addition, the main symptoms of autism always appear very early - autism can be diagnosed between the ages of 1 and 3 years. The symptoms of schizophrenia usually appear in young adults.

Many physicians have reported that they have identified previously undiagnosed autism in adults with schizophrenia and vice versa. However, studies on how often autism and schizophrenia coexist have produced conflicting results (Chisolm 2015). Studies have shown that schizophrenia occurs in 4-35% of adults with autism, and that 4-60% of people with schizophrenia have autism. In comparison, schizophrenia occurs in about 1.1% of the general population, and autism occurs in about 1.5% (NIMH/Regier 1993, Baio 2014).

The authors of the studies cited above believe that screening for autism among adults diagnosed with schizophrenia is necessary, and that adolescents and adults with autism should also be monitored for the possible emergence of symptoms of schizophrenia.

Bipolar affective disorder

Bipolar affective disorder is a mood disorder formerly called "manic depressive disorder" or "manic depression". People with bipolar affective disorder may experience periods of agitation called mania and periods of depression. While some people have only episodes of mania, most people with this disorder have alternating states of mania and depression, and they can also be extremely irritable.

Research shows that children and adults with autism are at increased risk of bipolar disorder (Munesue 2008, Rosenberg 2011, Vannucchi 2014, Guinchat 2015). However, data on the prevalence of this disorder among people with autism vary widely, ranging from 6% to 27%. By comparison, about 4% of the general population has bipolar affective disorder (Kessler 1994).

However, some leading autism experts suggest that bipolar disorder is often misdiagnosed in people with autism. The reason is that autism may be associated with symptoms that resemble bipolar disorder – increased motor activity, irritability, sleep disturbances (Witwer 2014).