Birth control emotions

Feel like a different person on the pill? Here’s how it affects your mood |

Science Mar 26, 2020 / Sarah E. Hill PhD

Dingding Hu

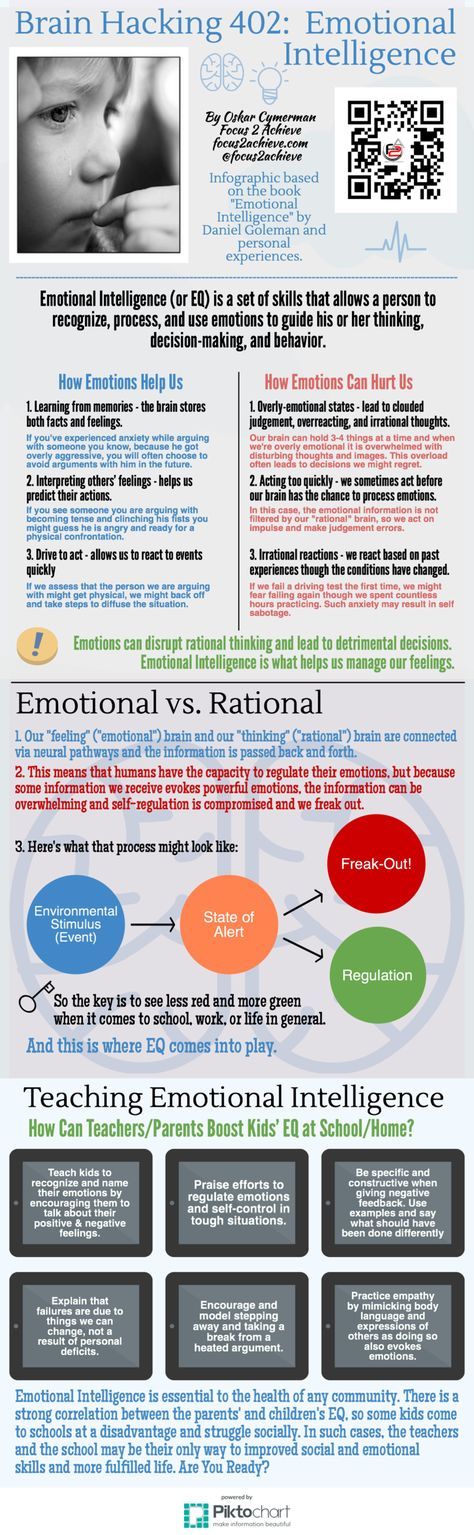

If you think your contraception is making you anxious or depressed, you’re not imagining things. Evolutionary psychologist Sarah E. Hill explains what happens to your brain on birth control.

Most women know at least one or two other women who have had a bad reaction to the pill. In fact, the question that many of us have about the pill: “Why does the pill make me crazy?”

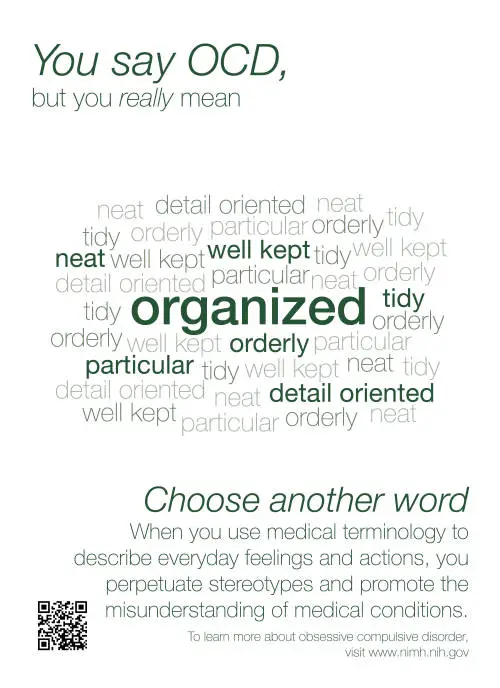

Before I get into what the research says about all this, let me just address the elephant in the room — the whole thing about women’s sex hormones influencing mood. Which they do. This might be the world’s oldest cliché about women, but that doesn’t make it any less true. Women’s sex hormones influence women’s moods. Men’s sex hormones affect men’s moods. It would be impossible for them not to.

Back to the question. To start with, all of us feel a little crazy sometimes. Life is hard and can make anyone feel anxious and overwhelmed at times. For some women, being on the pill can magnify these feelings, leading to anxiety disorders and depression. But if these things happen to you, it doesn’t mean you’re crazy; it just means you’re on the wrong pill.

Mood-related issues like anxiety and depression are super-common among women on the pill. Almost half of all women who go on the pill stop using it within the first year because of intolerable side effects, and the one most frequently cited is unpleasant changes in mood. Sometimes it’s intolerable anxiety; other times, it’s intolerable depression; or maybe both simultaneously. And even though some women’s doctors may tell them that those mood changes aren’t real or important, a growing body of research suggests otherwise.

The Scandinavian nation of Denmark is home to a number of nationwide registers, collections of data from its citizens on different health and social issues. Because all Danish citizens have a unique personal identification number, researchers have been able to link individual people’s data across different registers, giving them access to tons of information about patterns of health and social behavior in a whole population.

Because all Danish citizens have a unique personal identification number, researchers have been able to link individual people’s data across different registers, giving them access to tons of information about patterns of health and social behavior in a whole population.

From these registers, we’ve learned valuable lessons about the powerful effects that the birth control pill can have on mood. In the first of these studies, the researchers looked at the records of all the healthy, nondepressed women living in Denmark between the ages of 15 and 34. They then followed the prescription and mental health records of these women (more than a million of them) for 14 years to see whether going on hormonal contraceptives influenced the likelihood of later being diagnosed with depression or being prescribed antidepressants.

The researchers found that women on hormonal contraceptives were 50 percent more likely to be diagnosed with depression six months later, compared with women who were not prescribed hormonal contraceptives during this time. They also found the women on hormonal contraceptives were 40 percent more likely to be prescribed an antidepressant than were women who weren’t prescribed hormonal contraceptives during this time. The results of this study, as well as others, suggest the pill can increase some women’s risk of depression. This seemed particularly true for non-oral products (such as a patch, vaginal ring or hormonal IUD) and for young women (ages 15 to 19), whose brains are not yet done developing and may be more prone to the influence of hormonal signaling.

They also found the women on hormonal contraceptives were 40 percent more likely to be prescribed an antidepressant than were women who weren’t prescribed hormonal contraceptives during this time. The results of this study, as well as others, suggest the pill can increase some women’s risk of depression. This seemed particularly true for non-oral products (such as a patch, vaginal ring or hormonal IUD) and for young women (ages 15 to 19), whose brains are not yet done developing and may be more prone to the influence of hormonal signaling.

As a scientist, I’m obliged to point out we don’t know for sure that the pills caused this increase. Correlation doesn’t equal causation. It’s possible the researchers found pill taking and depression to be related because they were each related to some other third variable. For instance, women who seek medical interventions to prevent pregnancy might be more likely to seek medical interventions for depression. Or, getting into a new sexual relationship (which can prompt a pill prescription) could be what’s increasing women’s depression risk.

However, the researchers statistically tested for the influence of a number of third variables, and each of these tests found that hormonal contraceptives predicted depression risk even after statistically controlling for these third variables. Even though this wasn’t a double-blind, placebo-controlled experiment, the researchers took great care with their study design and data analysis and the results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the top medical journal in the US.

More recently, the same team looked at whether hormonal contraceptives might increase women’s risk of suicide. Researchers tracked hormonal contraceptive usage and suicide attempts and deaths in all Danish women who’d turned 15 between 1996 and 2013. (As in their prior study, they did not include any women who had previously diagnosed psychological problems or who had used antidepressants. They also didn’t include women already on hormonal contraceptives when they entered the study. ) They followed the women for an average of eight years and then compared the likelihood of having attempted or successfully committed suicide among the women who were prescribed hormonal contraceptives and those who were not.

) They followed the women for an average of eight years and then compared the likelihood of having attempted or successfully committed suicide among the women who were prescribed hormonal contraceptives and those who were not.

The women on hormonal contraceptives were twice as likely to have attempted suicide during this time than the women not on hormonal contraceptives. But the risk of successful suicide attempts was actually higher: It was triple that of women not on hormonal contraceptives. As with depression risk, the biggest negative impact of hormonal contraceptives on suicide risk was found for young women (ages 15 to 19) on non-oral products.

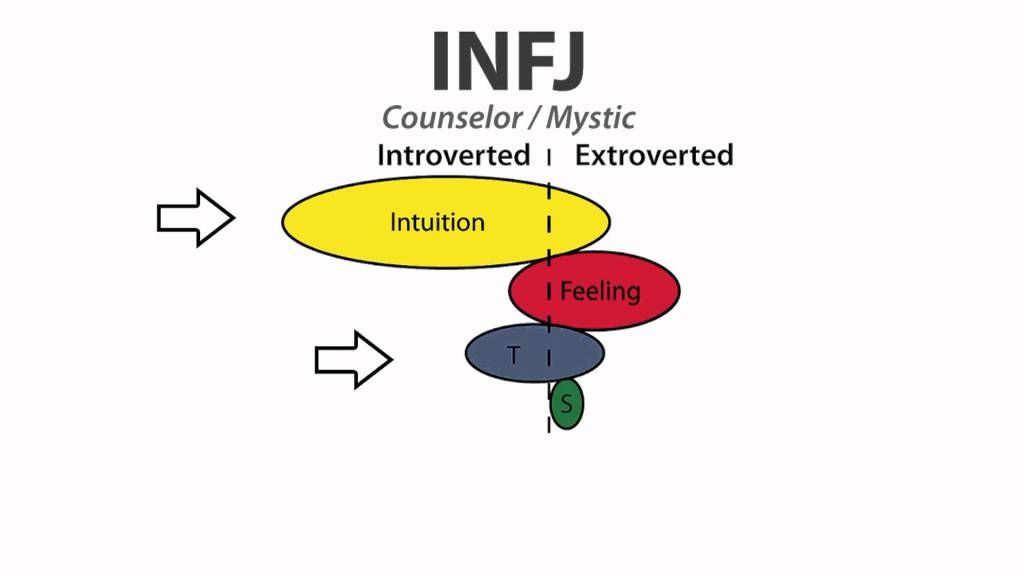

When it comes to why the pill can mess with your mood, the two systems that shoulder most of the blame are the HPA axis and some of our neurotransmitter systems. First, the HPA axis (or hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis). It’s made up of three systems working together — the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland, the adrenal glands — and plays a central role in the body’s stress response. The type of blunting of the HPA axis we tend to see in pill-taking women is a known contributor to mental health problems, including the types of mood disturbances characteristic of PTSD. Because lacking the biological tools necessary to deal with stress literally harms your ability to cope, having a broken stress response might be a key player in the development of anxiety and depression. It could also harm emotional well-being in indirect ways through its negative impact on our ability to absorb emotionally meaningful events from our environments.

The type of blunting of the HPA axis we tend to see in pill-taking women is a known contributor to mental health problems, including the types of mood disturbances characteristic of PTSD. Because lacking the biological tools necessary to deal with stress literally harms your ability to cope, having a broken stress response might be a key player in the development of anxiety and depression. It could also harm emotional well-being in indirect ways through its negative impact on our ability to absorb emotionally meaningful events from our environments.

The second piece is the role that neurotransmitter systems play in making women feel lousy on the pill. Before I explain, I need you to know three quick things.

Quick Thing 1: Neurotransmitters are chemicals that the brain uses to communicate with itself and the rest of the body.

Quick Thing 2: Excitatory neurotransmitters tell your brain cells to get ready for action, making them more likely to fire off messages to other brain cells.

Quick Thing 3: Inhibitory neurotransmitters tell your brain cells to slow their roll, making them less likely to fire off messages to other cells in the brain.

The most prevalent and frequently used inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain is GABA. It’s often on the scene in a big way when your brain is trying to slow itself down. GABA gets released when you’re relaxing in your PJ pants, and it’s also released when doing things like meditation and yoga.

Interestingly, you can get a relaxed GABA-rific experience from other things that stimulate GABA receptors, such as alcohol and benzodiazepines like Xanax. And our bodies actually produce compounds that work much like alcohol and Xanax. One of the most powerful is allopregnanolone, a neurosteroid. It gets synthesized when progesterone is broken down in the body and has the effect of kick-starting action by your GABA receptors.

Unfortunately for women on the pill, the artificial progestins in the pill don’t seem to offer this same benefit. In fact, research suggests that women on the pill may have lower levels of these natural sedatives relative to what’s observed in its absence, regardless of the point in the cycle.

In fact, research suggests that women on the pill may have lower levels of these natural sedatives relative to what’s observed in its absence, regardless of the point in the cycle.

This can mean bad news for women’s mental health. When GABA receptors aren’t properly stimulated, it’s known to make people feel anxious, overwhelmed and depressed. A number of mental-health-related issues, including panic disorder, depression, bipolar disorder and the mood-related symptoms of PMS, are characterized by lower-than-average levels of GABAergic activity. Lack of such activity can also increase a person’s risk of alcohol dependence.

Research suggests that changes in dopamine and serotonin signaling may also play a role in mood-related changes seen on the pill. Dopamine and serotonin, like GABA, are neurotransmitters. These chemicals come on the scene when we’re spending time with people we love, eating hot fudge sundaes, falling in love, having sex and having orgasms..jpg)

Not surprisingly, these neurotransmitter systems change what they do in response to women’s cyclically changing sex hormones. In particular, the research finds that estrogen makes rewarding things feel even more rewarding than they do in its absence and that progesterone attenuates these effects. Estrogen makes sex feel sexier, chocolate taste yummier, and getting status boosts feel boost-ier.

Given that the pill keeps estrogen levels low across the cycle and stimulates progesterone receptors, it’s possible the pill might have the effect of dampening reward processing in the brain. And if the world seems unrewarding, this makes us feel depressed. One hallmark symptom of depression is that people no longer find pleasure in things that they used to find pleasure in. So it’s also possible that the pill might increase a person’s risk of depression by making pleasure less pleasurable. Consistent with this idea, research finds that pill-taking women — when compared with their naturally cycling counterparts — have a blunted positive emotional response to happy things and don’t experience activity in the reward centers of their brains when looking at pictures of their romantic partners.

It seems pretty clear from the research that the pill can cause some women some pretty serious problems with their mental health, but the science isn’t yet at a point where we can make strong predictions about exactly what’s going to happen to whom, and on what.

However, according to the research, you might have a greater risk of experiencing negative mood effects on the pill if:

- You have a history of depression or mental illness (although there is also evidence that the pill can stabilize mood in certain women with mental illness).

- You have a personal or family history of mood-related side effects on the birth control pill.

- You are taking progestin-only pills.

- You are using a non-oral product.

- You are taking multi-phasic pills (pills with an increasing dose of hormones across the cycle rather than a constant dose).

- You are 19 or younger.

These bullet points can give you a starting point to initiate a conversation with your doctor about any mental health concerns. They aren’t your fate, though. Even if you’re an 18-year-old with a family history of depression and you’re on the birth control patch, if you aren’t experiencing signs of troubled mental health, the chances are incredibly low that you’re going to suddenly develop mood problems from birth control. This is especially true if you’ve been on it for a while and seem to be tolerating it well.

They aren’t your fate, though. Even if you’re an 18-year-old with a family history of depression and you’re on the birth control patch, if you aren’t experiencing signs of troubled mental health, the chances are incredibly low that you’re going to suddenly develop mood problems from birth control. This is especially true if you’ve been on it for a while and seem to be tolerating it well.

What’s more, while some women experience negative mood changes on the pill, some women experience the opposite reaction. They feel a whole lot better and mentally healthier on the pill than off it. Research also finds that the pill can offer huge mood-stabilizing benefits to women who have severe PMS.

The most critical thing about the pill’s effects will come from you: How do you feel on it?

Any time you start a new pill, please let someone close to you know about it. Ask them to make note and tell you if they notice any changes in your behavior that might suggest the onset of depression.

Because the hormones in the pill influence what the brain does, it’s almost impossible to separate out what the hormones are doing from who we are. We feel like the version of reality that is created by our brain on the pill is real. This can make it difficult to notice depression creeping in. Rather than feeling like the pill is messing with our mood, it just feels like our life is getting crappier or our job has gotten more stressful. If you tell your person that you are trying a new pill, they may be able to help you recognize problems that start to develop so that you can look for a new pill or an alternative means of protecting yourself from pregnancy.

On top of this, consider keeping a journal. If possible, start it before going on the pill so you have a log of how you were feeling before and after. Having hard evidence of your mood prior to the pill can be a good way for you to think about your past more objectively, making it easier to recognize any changes. In each entry, make note of your mood, energy level and well-being using some sort of scale (1=”I feel sad/anxious” and 10=”I feel great”). This will help you keep tabs on how things change for you (or not) when trying out a new pill.

In each entry, make note of your mood, energy level and well-being using some sort of scale (1=”I feel sad/anxious” and 10=”I feel great”). This will help you keep tabs on how things change for you (or not) when trying out a new pill.

If you’re already on the pill, it’s not too late to keep track of how you’re feeling. Make a note of your patterns. If you have more happy days than sad ones, that probably means everything’s on the right track. None of us feel happy all the time, but we should feel happier more often than sad when things in our lives are going well. If you have fewer happy days than you think you should, talk to your doctor. It could be time to try a new pill or address an issue with your mental health that you’ve let go too long.

Excerpted with permission from the new book This Is Your Brain on Birth Control: The Surprising Science of Women, Hormones, and the Law of Unintended Consequences by Sarah E. Hill PhD. Published by Avery, an imprint of Penguin Random House, LLC. © 2019 by Sarah E. Hill.

© 2019 by Sarah E. Hill.

Watch her TEDxVienna Talk now:

Does Birth Control Make You Moody?

Written by Hope Cristol

Medically Reviewed by Traci C. Johnson, MD on May 06, 2021

In this Article

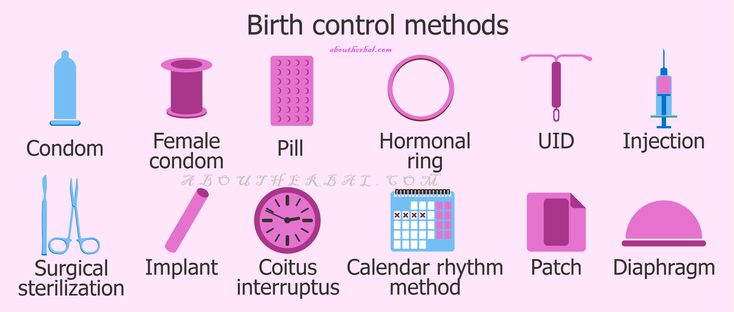

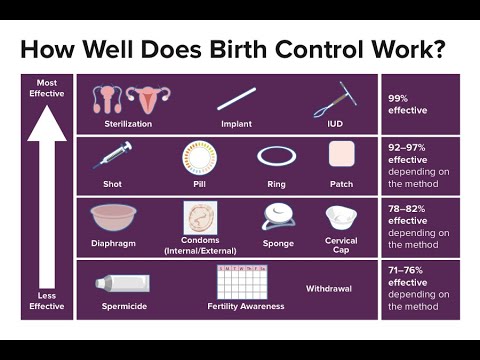

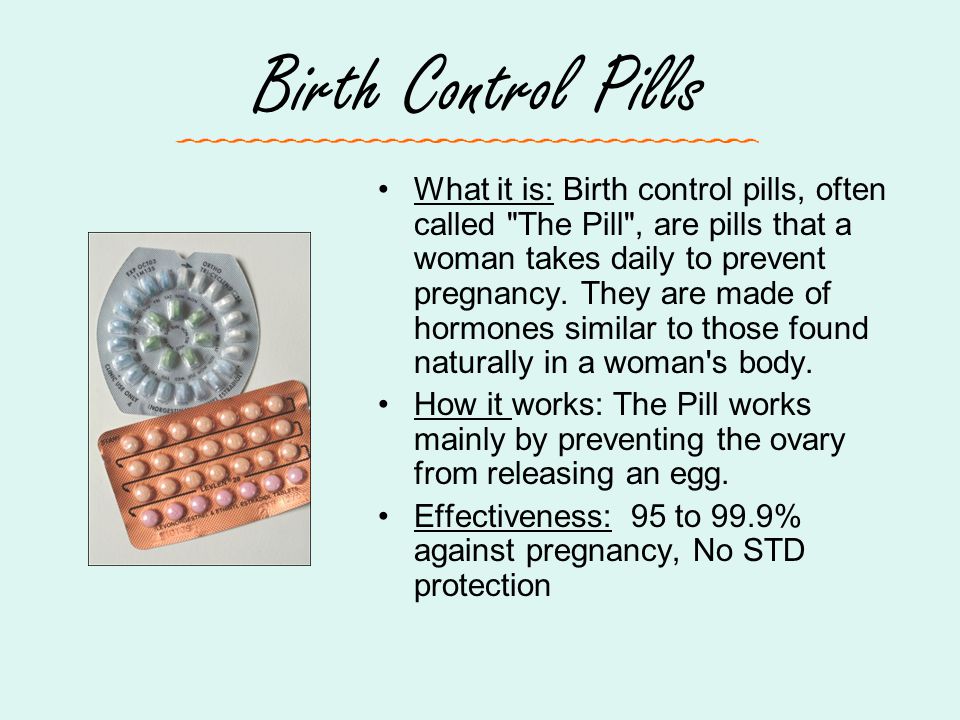

- How Hormonal Contraceptives Work

- Is There a Link Between Birth Control and Emotions?

- Benefits

- Possible Explanations

- When to See a Doctor

Lots of women get irritable, depressed, or feel out of sorts just before their monthly periods. Those can be symptoms of a common condition called premenstrual syndrome (PMS).

But could your birth control pills and other hormonal contraceptives trigger similar emotional swings? Or might they do the reverse and actually improve your moods?

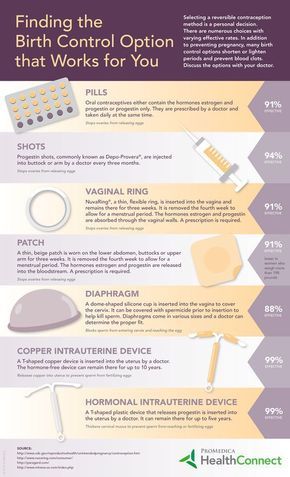

How Hormonal Contraceptives Work

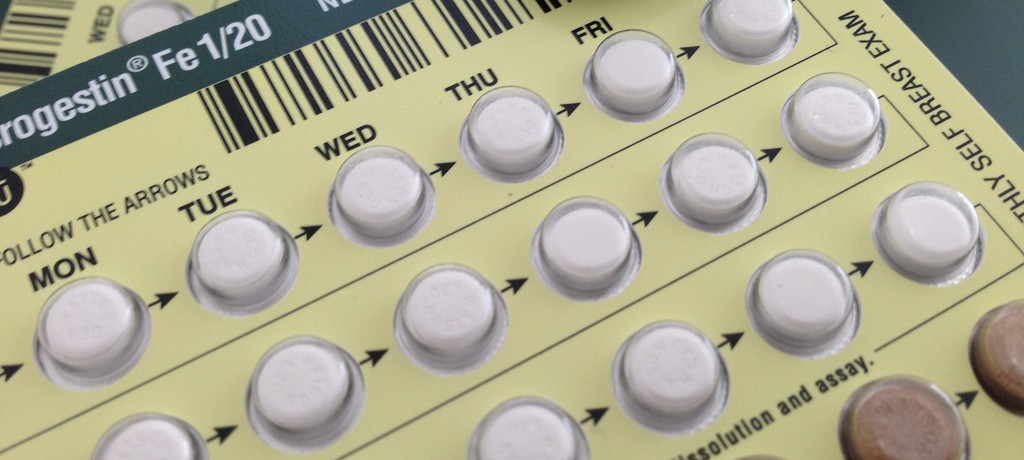

Most birth control pills, patches, and rings combine two lab-made female sex hormones, estrogen and progestin. “Minipills” have only progestin, and in a smaller amount.

“Minipills” have only progestin, and in a smaller amount.

Combined hormonal contraceptives stop the normal rise and fall of your body’s natural hormones. That blocks your body from ovulating and releasing an egg to be fertilized by sperm.

Is There a Link Between Birth Control and Emotions?

Women have complained about mood-related changes like depression and anxiety ever since the pill came out in 1960. The newest generation of pills have lower doses of hormones. Even so, a sizeable number of women still quit the pill because of side effects.

During a typical 28-day menstrual cycle, estrogen levels reach their peak around day 14. That’s when many women feel best emotionally and physically. Most hormonal contraceptives smooth this mountain-shaped hormonal cycle into an even line for the first 21 days. Then the levels of estrogen and progestin plunge during the final 7 days.

Limited research suggests that compared with women who don’t use hormonal birth control, those who do are more likely report feeling depressed, anxious, and angry.![]() But those symptoms don’t make the list of common side effects. Other studies have turned up no significant link between hormone combinations or concentrations and differences in mood. Still more research has found that women on the pill and those taking dummy pills report similar symptoms, suggesting that any effects they noticed were unrelated to the actual pills.

But those symptoms don’t make the list of common side effects. Other studies have turned up no significant link between hormone combinations or concentrations and differences in mood. Still more research has found that women on the pill and those taking dummy pills report similar symptoms, suggesting that any effects they noticed were unrelated to the actual pills.

Benefits

Doctors sometimes prescribe hormonal contraceptives to ease the discomfort that practically every woman notices at one time or another during their monthly periods.

Symptoms of premenstrual syndrome can include:

- Angry outbursts

- Crying spells

- Confusion

- Feeling down or depressed

- Trouble sleeping

- Irritability

- Tender breasts

- Aches and pains

- Bloating or weight gain

- Headache

The FDA has approved a specific type of hormonal birth control pill -- containing drospirenone and ethinyl estradiol -- to treat a more serious form of PMS called premenstrual dysphoric disorder. But the hormones may work better to ease physical symptoms than mood-related ones. It also can take some trial and error for your doctors to hit on the right medication and dosage.

But the hormones may work better to ease physical symptoms than mood-related ones. It also can take some trial and error for your doctors to hit on the right medication and dosage.

Possible Explanations

If scientists can’t firmly connect the dots between birth control hormones and emotional turbulence, why do some women believe there’s a link?

- Greater sensitivity to changes to levels of estrogen and other hormones

- Stress from the need to avoid pregnancy and to take the pill as prescribed

- Heightened perception of possible symptoms among women with existing depression, anxiety, or other mental health conditions

When to See a Doctor

If your mood swings are mild or moderate, exercise, healthier eating, relaxation, and other lifestyle changes may bring you relief. See your doctor if you feel depressed, feel no energy, or have other severe symptoms that interfere with your daily life.

90,000 For 10 Girls, 12 Boys: How China's Birth Control Led to a Women Deficit 90,001 90,002 90,003 Forbes Woman reveals how it led to gender imbalance and affected women Recently it became known that in the next few years, China may remove restrictions on the number of children in families, sources told Reuters. The 2021 census showed that China remains the most populous country in the world and the population continues to grow: now it is 1.41 billion people, but the growth rate has critically slowed down. Birth control led to an aging population and a labor shortage, the cheapness of which has long fueled the growth of the Chinese economy. At the same time, unlike developed countries that faced a similar problem, China “aged before getting rich”: in the list of countries in terms of GDP per capita, it ranks 86th (World Bank data for 2019).year). Another feature of China is that the decline in the population growth rate was created artificially, and superimposed on patriarchal traditions, it gave rise to a gender imbalance.

The 2021 census showed that China remains the most populous country in the world and the population continues to grow: now it is 1.41 billion people, but the growth rate has critically slowed down. Birth control led to an aging population and a labor shortage, the cheapness of which has long fueled the growth of the Chinese economy. At the same time, unlike developed countries that faced a similar problem, China “aged before getting rich”: in the list of countries in terms of GDP per capita, it ranks 86th (World Bank data for 2019).year). Another feature of China is that the decline in the population growth rate was created artificially, and superimposed on patriarchal traditions, it gave rise to a gender imbalance.

The Central Bank of China called for abandoning birth control because of the risk of falling behind the United States

Birth control policy

In the early years of the PRC, the birth of several children was encouraged, but then the party's position changed. Birth control was supposed, among other things, to contribute to the modernization of rural areas and reduce the demographic burden of children on the working population. Attempts to introduce such a restriction have been made several times; the current program, known as "one family - one child", started at 1979 year.

Birth control was supposed, among other things, to contribute to the modernization of rural areas and reduce the demographic burden of children on the working population. Attempts to introduce such a restriction have been made several times; the current program, known as "one family - one child", started at 1979 year.

From the very beginning, the program provided exceptions that allowed, under certain conditions, to have a second child. Since the mid-1980s, birth control rules have been at the mercy of provincial administrations, in some of which representatives of national minorities could, without fear of sanctions, give birth to a third.

Despite these exceptions, the policy of birth control proved to be effective, but caused a decline in the working-age population in the first place. At the same time, the life expectancy of the elderly has increased. Expecting lower income levels in retirement, they reduce consumption, which negatively affects the economy.

In 2016, the Chinese government officially allowed all couples to have two children, and local authorities began to increasingly turn a blind eye to the "unauthorized" birth of a third. The baby boom, however, did not happen - on the contrary, the birth rate began to fall (in 2020 - by 15%). In March of this year, experts from the Central Bank of China published a report in which they called for the abolition of the current birth restrictions - otherwise, the goals outlined in the plan for socialist modernization by 2035 will not be achieved.

- Pensioners will bring growth: how the pension reform and low birth rate created the prerequisites for a jump in the Russian economy women

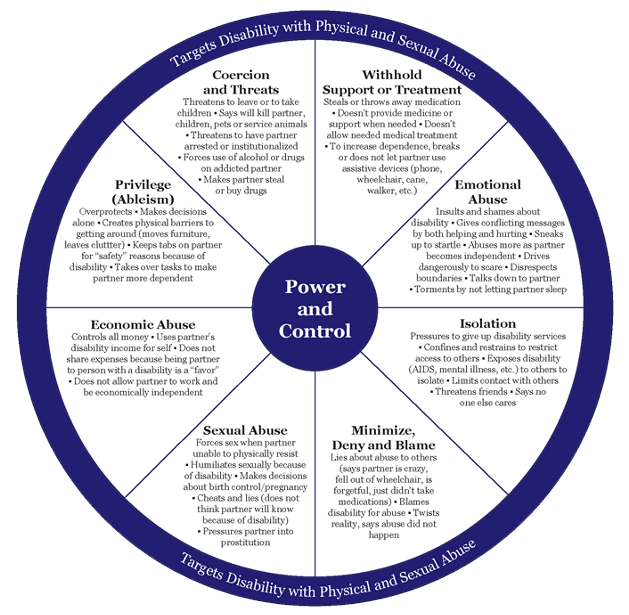

The policy of birth control was also presented as a logical consequence of the changing status of women and indeed gave many of them additional time to work. Sociologists Yingqi Wang and Tao Liu cite the following data: among mothers who have children under the age of five, 51.

1% work (46.1% do not work, 2.8% are registered as unemployed), while among women , who do not have children of this age, have been working for 59.4% (37% do not work, 2.7% are registered as unemployed). It is paradoxical, however, that under the current birth control policy, a woman who has given birth to an “extra” child can be fired (not to mention the fact that fertility regulation in itself is a restriction on women’s reproductive rights). In addition, all the benefits of childlessness are “eaten up”, firstly, by the growing cost of maintaining even an only child, and secondly, by unpaid housework.

1% work (46.1% do not work, 2.8% are registered as unemployed), while among women , who do not have children of this age, have been working for 59.4% (37% do not work, 2.7% are registered as unemployed). It is paradoxical, however, that under the current birth control policy, a woman who has given birth to an “extra” child can be fired (not to mention the fact that fertility regulation in itself is a restriction on women’s reproductive rights). In addition, all the benefits of childlessness are “eaten up”, firstly, by the growing cost of maintaining even an only child, and secondly, by unpaid housework. In China, traditional values are still strong, implying that a man is a breadwinner, and a woman is a mother and a housewife. In a report released in 2004, the State Council of China explicitly acknowledged that "the customs of inequality between men and women, inherited from China's history and culture, have not yet been completely eradicated." The idea that “men should be turned to society, and women to the family” in 2010 was shared by 61.

6% of men and 54.8% of women. Chinese women spend an average of 237 minutes a day on unpaid housework, while men spend only 94 minutes (data from the International Labor Organization for 2018).

6% of men and 54.8% of women. Chinese women spend an average of 237 minutes a day on unpaid housework, while men spend only 94 minutes (data from the International Labor Organization for 2018). This job includes caring for elderly relatives—and as China's population ages, the burden on women of working age will increase. At the same time, patrilocality is preserved in some rural areas - that is, a woman, when she marries, moves to her husband's family, and her parents are left without support in old age. This, and the social privileges enjoyed by men, make sons more desirable than daughters. So much so that one of the exceptions to the one-child rule mentioned above allowed rural families to have a second child if the first child was a girl.

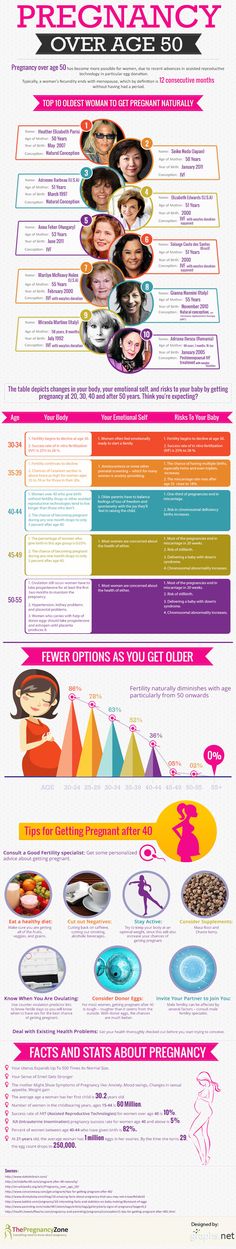

Gender imbalanceIn the mid-1990s, sociologist Ansley Cole drew attention to the too low number of Chinese women compared to men. The normal sex ratio for any human population at birth is 100 girls to 105 boys; for other age groups, it may vary depending on mortality rates.

Comparing data from various censuses since the beginning of the 20th century, Cole found that the shortage of women in China is characteristic of all age groups, including infants - in other words, many girls are either not born or die shortly after birth. If at 19In 1979, 106 boys were born for every 100 girls, then in 1990 - 111 boys.

Comparing data from various censuses since the beginning of the 20th century, Cole found that the shortage of women in China is characteristic of all age groups, including infants - in other words, many girls are either not born or die shortly after birth. If at 19In 1979, 106 boys were born for every 100 girls, then in 1990 - 111 boys. “The rate of excess early female mortality (probably infanticide) dropped sharply during the communist period, but not to zero,” writes Cole. "The recent rise in the number of 'missing' girls in China is largely driven by the rapid rise in selective abortions." Simply put, expectant couples make the decision to terminate the pregnancy if they find out they are having a daughter.

In addition, newborn girls in rural areas have less access to health care than boys. The result is high infant mortality. “When a son is sick, parents react faster and spend significant resources on his treatment,” writes sinologist Isabelle Attane.

“When their daughter is sick, they hesitate to consult a doctor or take the child to the hospital and, on average, spend less on medical care than on their son.”

“When their daughter is sick, they hesitate to consult a doctor or take the child to the hospital and, on average, spend less on medical care than on their son.” Today, the male population of China exceeds the female population by more than 30 million. Among people aged 20–24, for every 100 women, there are 114.6 men; among people aged 15–19, 118.4 men; 10-14 years old - 119 men. As today's teenagers mature, this imbalance will become more pronounced.

Marriage marketThe most obvious consequence of the surplus of men is the shortage of potential wives in the marriage market. Some researchers believe that this position increases the value of the latter and enables them to marry men of higher status. Others note that in this case, within the family, gender inequality is reinforced by social inequality. In addition, as Isabelle Attane suggests, with a shortage of brides, men will have to wait longer for the opportunity to marry, while women will be “snapped up”, which will result in a large number of couples with a large difference in age.

All this, in theory, can worsen the position of a married woman, secure her the role of a housewife and limit her economic independence.

All this, in theory, can worsen the position of a married woman, secure her the role of a housewife and limit her economic independence. At the same time, the number of men who will never get married is growing. In China, they are called "guanggun" - "bare branches". Political scientists Valerie Hudson and Andrea der Boer suggested in 2002 that this would lead to an upsurge in violence as the “bare branches” would seek to seize resources that would enable them to compete equally in the marriage market: “These theoretical predictions are supported by empirical evidence. [...] Regardless of cultural background, the vast majority of violent crime is committed by young, low-status unmarried men.” The authors of a study published in 2011 write that they found "no evidence that [single men] are prone to aggression or violence, nor reports of crime and disorder in areas known to have a high male presence." But they note that the “bare branches”, as a rule, have low self-esteem, they are closed and prone to depression.

However, the attitude towards marriage in China, especially in the cities, is changing: many young people deliberately refuse it. In 2018, 10.14 million marriages were registered in China, in 2019 - 9.27, in 2020 - 8.1 million. But the number of divorces is growing: if in 1987 580,000 in 2020 - already more than 3 million, their share over the same period increased from 0.5% to 3.4%. According to the All-China Women's Federation, 70% of divorces are initiated by wives.

The lack of potential partners has led to the flourishing of sex trafficking. Most often, its victims are women from disadvantaged regions - North Korea, Myanmar and others. Traveling to China to earn money, they end up in the hands of brokers who sell them into slavery. The authors of the Human Right Watch report directly point to gender imbalance as the reason for the high demand for sex slaves. Some of the women survivors of sex slavery they interviewed said they were raped in order to conceive a child.

Children are either used as a way to keep a slave girl from escaping, or have value of their own - some HRW informants said they were ready to be released into the wild on the condition that the child remained in a Chinese family. At the same time, children born to illegal migrants are not officially registered, they do not have access to education and healthcare. According to various estimates, there are now about 30,000 “non-existent” children in the country.

Children are either used as a way to keep a slave girl from escaping, or have value of their own - some HRW informants said they were ready to be released into the wild on the condition that the child remained in a Chinese family. At the same time, children born to illegal migrants are not officially registered, they do not have access to education and healthcare. According to various estimates, there are now about 30,000 “non-existent” children in the country. - Love in South Korea: how they build relationships and treat marriage here

- “There is nothing worse than a bad marriage”: Lyudmila Ulitskaya — about love, low self-esteem and life in conditions of uncertainty

- Not long and unfortunate: why married people do not enjoy life more than single and single people raising the retirement age. However, this is unlikely to give a quick effect: the policy of "one family - one child" has led not only to a reduction in the birth rate, but also to the fact that now there is simply no one to increase it.

They try to solve the problem in different ways. For example, back in the early 2000s, the National Population and Family Planning Commission launched the Care for the Girls campaign, which tried to add value to daughters. The authorities are also fighting the practice of selective abortions, but since there are not many ways to separate them from other cases of abortion, the measures are limited to limiting the ability to have an abortion after the 14th week of pregnancy - this is the period when the sex of the unborn child can be determined.

Another direction is the preservation of the institution of marriage. For example, since January 1, 2021, a law has been in force in China, according to which a divorce application must be filed twice with a difference of a month - it is assumed that during this time the couple may change their mind about divorcing. There are even exotic proposals such as the introduction of the practice of polyandry (polyandry).

However, all this does not mean that Chinese families will become large families: the policy of birth control has created a mindset in which all the resources of a couple are focused on one child, and many families feel that they simply cannot afford a second.

Rich and prolific: fathers of many children on the Forbes list

9 photos

“The birth of the pill. How four enthusiasts rediscovered sex and made a revolution”

In the middle of the twentieth century, Americans discovered new degrees of sexual freedom. Intrigues on the side and sex before marriage were now not uncommon, but they were still publicly condemned. The American conservative society insisted on maintaining the usual gender roles. Women could not enjoy the changes, careers and personal desires had to be forgotten for the sake of family and children. Having sex outside of marriage turned out to be too dangerous: contraceptives were difficult to obtain, and abortion was prohibited by law.

That is why activist and founder of the American Birth Control League, Margaret Sanger, was obsessed with the idea of creating a simple and affordable oral contraceptive that could relieve women of the fear of becoming pregnant. In the book of journalist Jonathan Eig "The Birth of the Pill. How four enthusiasts rediscovered sex and made a revolution” (Livebook publishing house), translated into Russian by Anna Sinyatkina, tells in detail the history of the invention of birth control pills. N + 1 invites its readers to read an excerpt about the acquaintance of Margaret Sanger and the biologist Gregory Pincus, who, at her request, took up research in the field of hormonal contraception.

That is why activist and founder of the American Birth Control League, Margaret Sanger, was obsessed with the idea of creating a simple and affordable oral contraceptive that could relieve women of the fear of becoming pregnant. In the book of journalist Jonathan Eig "The Birth of the Pill. How four enthusiasts rediscovered sex and made a revolution” (Livebook publishing house), translated into Russian by Anna Sinyatkina, tells in detail the history of the invention of birth control pills. N + 1 invites its readers to read an excerpt about the acquaintance of Margaret Sanger and the biologist Gregory Pincus, who, at her request, took up research in the field of hormonal contraception. Pincus knew who Sanger was, and almost all of America knew. It was Sanger who popularized the term "birth control" and almost single-handedly launched the birth control movement in the United States. Women will never achieve equality, she said, until they are freed from sexual slavery.

Sanger founded the nation's first birth control center in Brooklyn in 1916 and helped open dozens of others around the world. But even after decades of operation, the contraceptive devices offered by these centers—mostly condoms and uterine caps—were still ineffective, uncomfortable, or difficult to obtain. It was like teaching the starving people the basics of proper nutrition without giving them food. Sanger explained to Pinkus that she was looking for an inexpensive and simple method of contraception with complete foolproofing, best of all - a pill. Something biological, she said, that a woman could swallow every morning with a glass of orange juice or while brushing her teeth, regardless of the consent of the man she was sleeping with. Something that will make sex spontaneous, without the need for preliminary thinking, unpleasant fuss or harm to pleasure. Something that won't make a woman unfertile if she later decides to have children. Something usable in every part of the world, from the slums of New York to the jungles of Southeast Asia.

Sanger founded the nation's first birth control center in Brooklyn in 1916 and helped open dozens of others around the world. But even after decades of operation, the contraceptive devices offered by these centers—mostly condoms and uterine caps—were still ineffective, uncomfortable, or difficult to obtain. It was like teaching the starving people the basics of proper nutrition without giving them food. Sanger explained to Pinkus that she was looking for an inexpensive and simple method of contraception with complete foolproofing, best of all - a pill. Something biological, she said, that a woman could swallow every morning with a glass of orange juice or while brushing her teeth, regardless of the consent of the man she was sleeping with. Something that will make sex spontaneous, without the need for preliminary thinking, unpleasant fuss or harm to pleasure. Something that won't make a woman unfertile if she later decides to have children. Something usable in every part of the world, from the slums of New York to the jungles of Southeast Asia. And yet 100% effective.

And yet 100% effective. Can this be done?

All the other scientists she approached - every single one of them - said no and gave a long list of reasons. Dirty, disrespectful job. The technology is missing. Even if you manage to do something - what's the use. Thirty states have laws against birth control, and there are federal laws of the same kind. Why go to the trouble of creating a pill that no company would dare to make, no doctor would dare prescribe?

But Sanger still hoped that Gregory Pincus would be different, that he'd have the courage—or the desperation—to try.

***

It was the middle of the century. Scientists began to deal with issues of life and death, which were previously dealt with by artists and philosophers. Men in lab coats—yes, almost exclusively men—were portrayed as heroes, victorious wars, pesterers of disease, givers of life. Malaria, tuberculosis, syphilis and many other ailments surrendered to modern medicine.

Governments and giant corporations poured unprecedented sums into research, sponsoring everything from school circles to cold fusion research. Health has become not only a public matter, but also a political one. The Second World War crippled the earth, but also transformed it. The future promised a better, freer world. And science showed the way.

Governments and giant corporations poured unprecedented sums into research, sponsoring everything from school circles to cold fusion research. Health has become not only a public matter, but also a political one. The Second World War crippled the earth, but also transformed it. The future promised a better, freer world. And science showed the way. Americans settled in new suburban box houses and discovered the joys of lawn care, dry martinis, and "I love Lucy" * . The United States in the early fifties seemed, at least to an outside observer, to be a stable and balanced country. The Andrews Sisters sang "I Wanna Be Loved" and John Wayne played in "The Sands of Iwo Jima" celebrating the nation's fighting power and commitment to democratic ideals.

It was a time when it was wonderful to be an American. Young people returning from the battlefield were looking for new adventures and new ways to feel like heroes, while getting used to the boredom of home life, marriage and work.

During the war, the norms of morality changed. Sex became more common as American soldiers could buy it from foreign women with cigarettes and money. Hot letters came from the homeland from girlfriends who promised great passion upon their return. And in fact, in America, many women were defining new moral boundaries for themselves. The war forced women to work hard, allowed them to earn money and freed them from parental care. They began dating men, having extramarital affairs with them, experimenting, rethinking the concepts of intimacy and commitment. In 1948, an Indiana college professor named Alfred Charles Kinsey published Sexual Behavior in the Male Man, and five years later, Sexual Behavior in the Female Man. He found that people were far more free-spirited than previously thought: Eighty-five percent talked about pre-marital sex, fifty percent had affairs outside, and nearly all reported masturbating. Subsequently, it turned out that Kinsey was slightly biased in his conclusions, but the impact of his work is nevertheless enormous.

During the war, the norms of morality changed. Sex became more common as American soldiers could buy it from foreign women with cigarettes and money. Hot letters came from the homeland from girlfriends who promised great passion upon their return. And in fact, in America, many women were defining new moral boundaries for themselves. The war forced women to work hard, allowed them to earn money and freed them from parental care. They began dating men, having extramarital affairs with them, experimenting, rethinking the concepts of intimacy and commitment. In 1948, an Indiana college professor named Alfred Charles Kinsey published Sexual Behavior in the Male Man, and five years later, Sexual Behavior in the Female Man. He found that people were far more free-spirited than previously thought: Eighty-five percent talked about pre-marital sex, fifty percent had affairs outside, and nearly all reported masturbating. Subsequently, it turned out that Kinsey was slightly biased in his conclusions, but the impact of his work is nevertheless enormous. In 1949, Hugh Hefner, a master's student in sociology at Northwestern University, read the Kinsey report and wrote a term paper arguing that it was time to end the suppression of sex and sexuality in America. "Can't we move out of this dark, heavily tabooed labyrinth of emotions and into the fresh air and light of reason?" Hefner wrote, meanwhile getting ready to do something about it himself.

In 1949, Hugh Hefner, a master's student in sociology at Northwestern University, read the Kinsey report and wrote a term paper arguing that it was time to end the suppression of sex and sexuality in America. "Can't we move out of this dark, heavily tabooed labyrinth of emotions and into the fresh air and light of reason?" Hefner wrote, meanwhile getting ready to do something about it himself. That late winter evening in Manhattan, the topic of discussion for Margaret Sanger and Gregory Pinkus was revolution. Yes, it is a revolution, nothing less. No bombs, no guns, just sex, the more the better. Sex without marriage. Sex without children. Sex reimagined, sex safe, limitless, meant for the pleasure of women.

Sex for the pleasure of women? In the fifties, this idea sounded as ridiculous as flying a man to the moon or baseball on artificial grass. Worse, she was dangerous. What will happen to the institutions of marriage and family? What will happen to love? If women are given power over their own bodies, if they are given the power to choose whether to get pregnant or not, what else do they want? Two thousand years of Christianity and three hundred years of American Puritanism will collapse under an explosion of irresistible desire.

Marriage vows will lose their meaning. Gender roles and rules can be repealed.

Marriage vows will lose their meaning. Gender roles and rules can be repealed. Science will do what the law has so far failed to do - it will give women the opportunity to become equal partners with men. This is the kind of technology Sanger has been looking for all her life.

And so, in an elegant apartment on Park Avenue, where long ribbons of cigarette smoke rose to the ceiling, Sanger, looking at Pincus over the coffee table, asked her question. She was seventy-one years old. She needed it. And him too.

- Do you think it's possible? she asked.

"I think so," Pinkus said.

There is a lot of research to be done, he replied, but yes, it is possible. Sanger had been waiting for those words all her life.

“Well,” she said. “In that case, start now.”

***

The next morning, Pincus was spinning his Chevrolet through the traffic heading for Massachusetts, the Sanger proposal running through his troubled mind. Driving was new to him.

He only recently got his first car - this one, left by a scientist who went abroad, and the sensation of power and speed obedient to him delighted him. Driving, like many other things in his life, became a sport for him, a competition. His passengers clutched the armrests with whitened fingers and asked where he was in such a hurry, but Pincus was unperturbed.

He only recently got his first car - this one, left by a scientist who went abroad, and the sensation of power and speed obedient to him delighted him. Driving, like many other things in his life, became a sport for him, a competition. His passengers clutched the armrests with whitened fingers and asked where he was in such a hurry, but Pincus was unperturbed. “It's just the way I drive,” he replied.

On a 180-mile journey, we had to brake and accelerate every now and then. There were no federal highways yet, but there were narrow two-lane roads where it was supposed to slow down near schools and at crossings. The long drive through cold gray towns and past sleeping farms gave Pinkus time to ponder Sanger's words.

Ever since people started having babies, they have also tried to avoid it. The ancient Egyptians made vaginal plugs from crocodile feces. Aristotle recommended cedar oil and frankincense as spermicides. Casanova ordered to use half a lemon as a uterine cap.

The most popular and effective method of birth control since the early fifties has been the condom, a simple device whose origins date back to the sixteenth century, when the Italian doctor Gabriele Fallopius tried to prevent the spread of syphilis with "a piece of linen cloth the size of the head of a penis." Not much has changed since the time of Fallopius. Condoms became cheaper and more widely used in the 1840s when the Goodyear Company began to vulcanize rubber. Rough uterine caps - prototypes of diaphragms - began to appear around the same time. But over the next century, little was invented in this area and even less was done.

The most popular and effective method of birth control since the early fifties has been the condom, a simple device whose origins date back to the sixteenth century, when the Italian doctor Gabriele Fallopius tried to prevent the spread of syphilis with "a piece of linen cloth the size of the head of a penis." Not much has changed since the time of Fallopius. Condoms became cheaper and more widely used in the 1840s when the Goodyear Company began to vulcanize rubber. Rough uterine caps - prototypes of diaphragms - began to appear around the same time. But over the next century, little was invented in this area and even less was done. Pincus was not interested in these ancient methods. He believed that inventing a contraceptive pill—or inventing anything—may well be a simple matter. Like driving. Step one: choose a destination. Step two: choose a route. Step three: try to get there as quickly as possible.

Instead of going home, he went to his office at the Worcester Foundation for Experimental Biology to talk to one of the researchers, M.

C. Zhang. By the early fifties, Pinkus and Hoagland had moved the fund from a refurbished Worcester barn to an ivy-covered brick house in Shrewsbury. “The foundation’s two-story building is sometimes referred to as the Lady’s Nursing Home,” the Worcester Telegram notes. “This is what it looks like from the Boston Post Road where it is located.”

C. Zhang. By the early fifties, Pinkus and Hoagland had moved the fund from a refurbished Worcester barn to an ivy-covered brick house in Shrewsbury. “The foundation’s two-story building is sometimes referred to as the Lady’s Nursing Home,” the Worcester Telegram notes. “This is what it looks like from the Boston Post Road where it is located.” Pinkus and Hoagland went out of their way to make the Ladies Nursing Home look like a place for science. The sunny veranda has been turned into a library. The bedrooms are in the laboratory. One such lab became a bedroom again when Zhang traveled from China, via the UK and Scotland, to work with Pincus. Zhang didn't speak much English, but Pincus noticed something in him and invited him to the foundation to work for a measly salary of two thousand dollars a year (about twenty-six thousand in modern times). Zhang knew Pincus's reputation and expected to work at one of America's prestigious institutions, get free housing on campus - or at least nearby.

He got free housing, but it was a room at the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA). She and Pinkus got to work by bus. Zhang later moved into the foundation, sleeping on a narrow bed in the corner of the former lab and heating up his meager snacks on a Bunsen burner. Like a true Confucian, he did not notice everyday inconveniences. He proudly related that in 1947, for an important experiment, he kept fertilized rabbit eggs in the kitchen refrigerator.

He got free housing, but it was a room at the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA). She and Pinkus got to work by bus. Zhang later moved into the foundation, sleeping on a narrow bed in the corner of the former lab and heating up his meager snacks on a Bunsen burner. Like a true Confucian, he did not notice everyday inconveniences. He proudly related that in 1947, for an important experiment, he kept fertilized rabbit eggs in the kitchen refrigerator. Pincus relayed to Zhang his conversation with Margaret Sanger about a pill that could prevent pregnancy. It had to be a pill, he explained, not an injection, not a gel or foam, and not a mechanical device for the vagina. When Pincus spoke in his own manner—purposefully, chopping the air with his hands, his eyes flashing from under bushy brows—the colleagues listened to him very attentively.

Among geniuses there are quiet, inconspicuous people - they are quite satisfied to have their work speak for them. Pinkus was not like that.

He was distinguished by a powerful physique, a stately figure and a muscular body. Although his suits and ties were uniformly cheap and at times mismatched, he nonetheless carried himself with aristocratic dignity. Pinkus had a booming voice, and one of his main trump cards was a confident demeanor. He understood one thing that eluded the attention of many scientists: research, experiments - this is only half the work. The other half, no less important, is to sell the result. No matter how good an idea is, it can easily die if it is not pushed aggressively—to other scientists, to patrons with deep pockets, and ultimately to the public. It was this very sale that let him down at Harvard, but did not stop him. He knew from the start that it was one thing to develop a birth control pill and another to convince the world to take it. If the scientist taking on the job is not prepared to do both halves of it, then there is no point in even trying.

He was distinguished by a powerful physique, a stately figure and a muscular body. Although his suits and ties were uniformly cheap and at times mismatched, he nonetheless carried himself with aristocratic dignity. Pinkus had a booming voice, and one of his main trump cards was a confident demeanor. He understood one thing that eluded the attention of many scientists: research, experiments - this is only half the work. The other half, no less important, is to sell the result. No matter how good an idea is, it can easily die if it is not pushed aggressively—to other scientists, to patrons with deep pockets, and ultimately to the public. It was this very sale that let him down at Harvard, but did not stop him. He knew from the start that it was one thing to develop a birth control pill and another to convince the world to take it. If the scientist taking on the job is not prepared to do both halves of it, then there is no point in even trying. Pincus and Zhang discussed the 1937 scientific paper "Effects of Progestin and Progesterone on Ovulation in Rabbits" by A.

W. Makepeace, G.L. Weinstein, and M.H. Friedman of the University of Pennsylvania. It said that injections of the hormone progesterone prevented ovulation in rabbits. It was a big discovery in its time, but no one has since tried to study what it might mean for people. There were many reasons. To begin with, no one was looking for innovation in the field of prevention: such work promised neither prestige nor money, only risk. And even if someone tried, progesterone was then too expensive for widespread use.

W. Makepeace, G.L. Weinstein, and M.H. Friedman of the University of Pennsylvania. It said that injections of the hormone progesterone prevented ovulation in rabbits. It was a big discovery in its time, but no one has since tried to study what it might mean for people. There were many reasons. To begin with, no one was looking for innovation in the field of prevention: such work promised neither prestige nor money, only risk. And even if someone tried, progesterone was then too expensive for widespread use. But by the time Pincus met Sanger and they had a conversation, attitudes towards birth control were already changing, albeit slightly. Even more important, perhaps, was the leap in the development of biology that occurred during this time. Scientists began to understand the processes occurring in the body sufficiently to try to intervene in them. Until the mid-twentieth century, medicines were mostly developed in the “suck-and-see” way, as the British called the trial and error method.

A scientist cooks something in the laboratory, drinks it, like Dr. Jekyll, and sees what happens. But those days were drawing to a close. How progesterone works, Pincus and Zhang knew, they needed to understand whether it could be produced, modified and used. Fortunately, advances in technology have made it much cheaper to extract progesterone. If Sanger gives money, Pincus is ready to offer an idea in which direction to move.

A scientist cooks something in the laboratory, drinks it, like Dr. Jekyll, and sees what happens. But those days were drawing to a close. How progesterone works, Pincus and Zhang knew, they needed to understand whether it could be produced, modified and used. Fortunately, advances in technology have made it much cheaper to extract progesterone. If Sanger gives money, Pincus is ready to offer an idea in which direction to move. Pincus was not just a science technologist, he had a romantic soul. By asking nature questions, he was looking not only for answers, but also for beauty. And he found this beauty.

In every woman between puberty and menopause, approximately every twenty-eight days, an egg is created in one of the ovaries and travels down the fallopian tube to the uterus. If a woman has had sex with a man and the man ejaculates, five hundred million spermatozoa vie for the right to fertilize that egg. An unfertilized egg cannot attach itself to the inner lining of the uterus and is released along with this lining.

If it is fertilized, then after about six days it attaches itself to the wall of the uterus, and the woman's blood begins to feed it through the placenta. Thus, pregnancy occurs: the zygote becomes an embryo, and the embryo becomes a fetus. The process is controlled by two sex hormones - estrogen and progesterone. Pincus focused mainly on progesterone.

If it is fertilized, then after about six days it attaches itself to the wall of the uterus, and the woman's blood begins to feed it through the placenta. Thus, pregnancy occurs: the zygote becomes an embryo, and the embryo becomes a fetus. The process is controlled by two sex hormones - estrogen and progesterone. Pincus focused mainly on progesterone. Often referred to as the pregnancy hormone, progesterone regulates the lining of the uterus. When an egg is fertilized, progesterone prepares the uterus for implantation and prevents the ovaries from making new eggs. In fact, Pinkus understood, nature already had an effective contraceptive. Progesterone prevents ovulation so that the fertilized egg can grow safely. What if the same contraceptive is packaged in a pill and deceives the female body, forcing it to think that the pregnancy has already begun? A woman could stop ovulating at any time and for as long as she wants. Without producing eggs, she will not be able to conceive.