Boundary violations in psychotherapy

Boundaries and Multiple Relationships in Psychotherapy

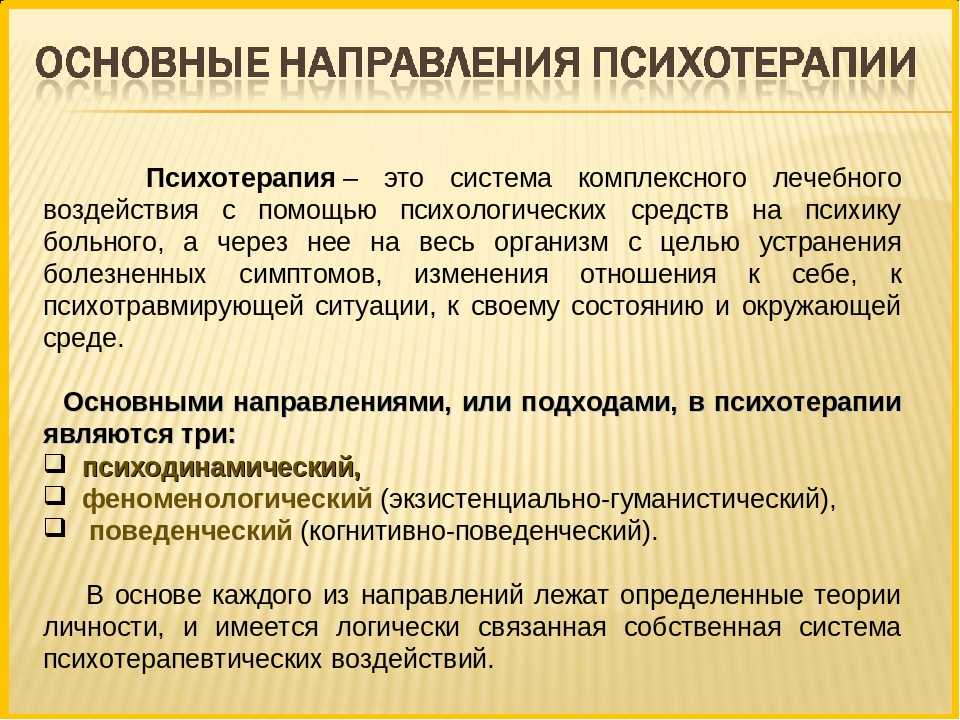

The process of psychotherapy is relationship based. As such, how psychotherapists conduct themselves in these relationships has significant clinical and ethical implications. The Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (APA Ethics Code, APA, 2010) makes clear the ethical obligations relevant to boundaries and multiple relationships that are likely to be well known by psychotherapists (e.g., it is unethical to engage in sexual relations with your clients). Yet, the APA Ethics Code cannot provide strict rules to apply to every clinical situation that may arise in practice. Psychotherapists must apply their judgment in making decisions about the appropriateness of different actions and behaviors, hopefully utilizing the guidance provided by the Ethics Code, consultation with colleagues, and a decision-making process.

Boundaries in the Psychotherapy Relationship

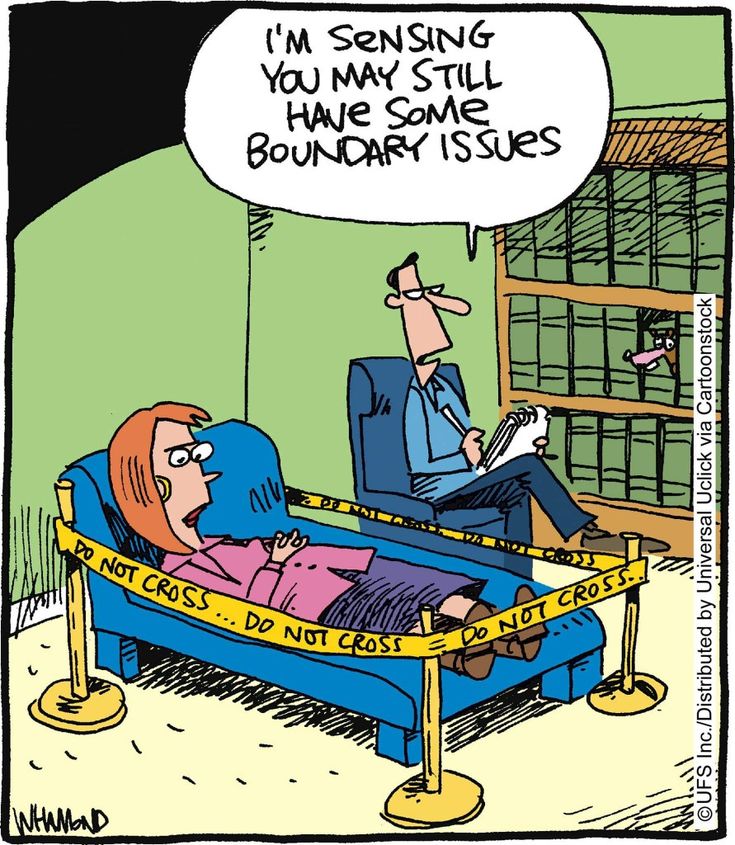

In psychotherapy there is a need for rules and expectations to be discussed and agreed upon in order for the relationship to be acceptable and successful for all parties. Boundaries constitute the agreed upon rules and expectations that articulate the parameters of the relationship.

Boundaries provide:

- “A therapeutic frame which defines a set of roles for the participants in the therapeutic process” (Smith and Fitzpatrick, 1995, p. 499)

- “a foundation for this relationship by fostering a sense of safety and the belief that the clinician will always act in the client’s best interest (Smith & Fitzpatrick, 1995, p. 500)

- a “distinction between the expectations and interactions that would be considered appropriate within the relationship and those that would be considered inappropriate within the relationship” (R. Sommers-Flanagan, Elliot, & J. Sommers-Flanagn, 1998, p. 38).

Six of the most common boundaries within the psychotherapy relationship include:

- Touch

- Time

- Space

- Location

- Gifts

- Self-disclosure

How each of these is addressed and managed in the psychotherapy relationship holds great implications for the client’s welfare as well as for achieving desired therapeutic outcomes.

Managing Boundaries

Boundaries may be avoided, crossed, or violated. To avoid a boundary means that it is not traversed at all. For example, with regard to the boundary of touch, consider a psychotherapist treating a client who is a survivor of sexual assault or trauma. It may be inappropriate and unbeneficial for the psychotherapist to use touch with the client, and in fact may be harmful. Another example would be a male psychotherapist providing psychotherapy to a female Orthodox Jew for whom any touch by a man who is not her husband would be considered taboo.

Smith and Fitzpatrick (1995) defined boundary crossing as “a nonpejorative term that describes departures from commonly accepted clinical practice that may or may not benefit the client” (p. 500). Thus, traversing a boundary in a manner that is not harmful or exploitative to the client and that may in fact, be supportive of a strong therapeutic alliance and that may promote achieving treatment goals is considered a boundary crossing. Possible examples of boundary crossings include shaking a client’s extended hand upon first meeting or extending the time of a treatment session for a client who is in crisis.

Possible examples of boundary crossings include shaking a client’s extended hand upon first meeting or extending the time of a treatment session for a client who is in crisis.

In contrast, a boundary violation is “a departure from accepted practice that places the client or the therapeutic process at serious risk” (Smith & Fitzpatrick, 1995, p. 500). Boundary violations are likely to be harmful, exploitative, and not in the client’s best interest. Additionally, boundary violations are likely to take advantage of the client’s dependence and trust, and often are confusing to clients and inconsistent with their treatment needs. Examples of boundary violations include engaging in sexually intimate behaviors with a client and a psychotherapist disclosing her or his personal issues and life challenges with a client in an effort to receive emotional support from the client.

Boundary Decision-Making

As was previously stated, boundaries should not always be avoided. In fact, a strict application of boundaries with clients may prove to be clinically ineffective and may create a cold or sterile environment that is contrary to the goals of a good working alliance (Zur & Lazarus, 2002). Flexibility with boundaries is recommended so that each client’s unique needs are met in the most appropriate manner possible.

In fact, a strict application of boundaries with clients may prove to be clinically ineffective and may create a cold or sterile environment that is contrary to the goals of a good working alliance (Zur & Lazarus, 2002). Flexibility with boundaries is recommended so that each client’s unique needs are met in the most appropriate manner possible.

It is likely that most psychotherapists are clear on those behaviors that are clearly ethical and those behaviors that are clearly unethical. It is the gray areas where there is no apparent right or wrong answer will likely prove most challenging to psychotherapists in determining the most appropriate course of action. When faced with these situations psychotherapists may benefit from engaging in a thoughtful decision-making process when deciding on the appropriateness of certain behaviors and in determining if a proposed action constitutes a boundary crossing or a boundary violation (Pope & Keith-Spiegel, 2008).

There are a number of factors that should be considered when engaging in a thoughtful decision-making process about boundaries.

These include:

- What are the motivations for taking the proposed action? Are they to meet the psychotherapist’s needs in some way or are they motivated by the client’s best interest?

- What is the likely effect or impact of the proposed action? Will it be of therapeutic value to the client or is it likely to be exploitative or harmful?

- Will the proposed action be welcomed by the client or viewed negatively? If this is not imminently clear, have you openly discussed the proposed action with the client to seek her or his input?

- Is the action under consideration consistent with widely accepted roles of psychotherapists and will taking this action risk jeopardizing the client’s, and the public’s, trust in the profession?

- Will the action under consideration promote the client’s autonomous functioning over time or is it more likely to create more dependence on the psychotherapist?

- Is the proposed action consistent with the agreed upon treatment plan and consistent with the client’s treatment goals?

- Are there any cultural factors or expectations, or other individual differences, that would impact the client’s needs and how the client might interpret or be impacted by the proposed action?

- Is the action under consideration consistent with your theoretical orientation?

- If unsure of any of the above, have you consulted with a colleague to receive input and feedback on your proposed course of action prior to taking it?

- Have you documented your decision-making process, the rationale for the decision you have made, and the impact of your action on the client?

As can be seen, there are a number of considerations that may be relevant for determining if a particular action or behavior would be considered a potentially helpful boundary crossing or a harmful boundary violation. Thus, a thoughtful decision-making process, at a minimum includes considerations of these questions, should occur in order to help ensure that the therapeutic relationship is preserved and that the client’s best interest is served.

Thus, a thoughtful decision-making process, at a minimum includes considerations of these questions, should occur in order to help ensure that the therapeutic relationship is preserved and that the client’s best interest is served.

Multiple Relationships

To engage in a multiple relationship is to enter into a secondary relationship in addition to the primary psychotherapy relationship. Multiple relationships may be social, business or financial, or sexual in nature. The APA Ethics Code (APA, 2010) makes it very clear that all multiple relationships need not be avoided; only those that hold a significant potential for exploitation of, or harm to, the client, and those that are likely to lead to impaired objectivity and judgment for the psychotherapist, must be avoided. Of course, knowing this in advance may prove challenging. Thus, the use of a decision-making process and consultation with colleagues is recommended when the outcome and effects of an anticipated multiple relationship is unclear.

In addition to considering the questions listed above prior to entering into a multiple relationship with a client or other individuals associated with the client, there are ethical decision-making models that may prove helpful for making these decisions. Younggren and Gottlieb (2004) suggest that the psychotherapist consider the following questions when contemplating entering into a multiple relationship with a client:

- Is entering into a relationship in addition to the professional relationship necessary, or should I avoid it?

- Can the [multiple] relationship potentially cause harm to the patient?

- If harm seems unlikely or unavoidable, would the additional relationship prove beneficial?

- Is there a risk that the [multiple] relationship could disrupt the therapeutic relationship?

- Can I evaluate this matter objectively? (pp. 256-257)

In many settings the complete avoidance of multiple relationships may prove impossible. These may include being a member of a community who both lives and works in that community such as in a rural setting; a small or isolated community; a religious, ethnic, or LGBT community; and others. Often, it is because the psychotherapist has been active in the community and known to its members in a variety of roles, that the community members feel comfortable in seeking professional services from the psychotherapist. In addition, in these settings, options for making referrals to other clinicians may be quite limited, further impacting decisions about providing psychotherapy to individuals with whom the psychotherapist has pre-existing relationships (Hargrove, 1986).

Often, it is because the psychotherapist has been active in the community and known to its members in a variety of roles, that the community members feel comfortable in seeking professional services from the psychotherapist. In addition, in these settings, options for making referrals to other clinicians may be quite limited, further impacting decisions about providing psychotherapy to individuals with whom the psychotherapist has pre-existing relationships (Hargrove, 1986).

In these settings the question is not “should I participate in multiple relationships?”, but “how should I best participate in multiple relationships so that my clients’ best interests are served?”. Curtin and Hargrove (2010) share the following representative example of life as a psychotherapist in a rural community: “my son’s third-grade teacher (a former client before I had children) also serves on the library board with my spouse and is a member of the Sunday school class that we attend. She shops at the same drug store and local discount house and eats at the same restaurants” (p. 550). But, as has been emphasized, not all multiple relationships are appropriate, and even in these settings, some multiple relationships will need to be avoided. How one makes these decisions, the factors one considers, when engaging in necessary multiple relationships is okay, and how they are managed is key.

550). But, as has been emphasized, not all multiple relationships are appropriate, and even in these settings, some multiple relationships will need to be avoided. How one makes these decisions, the factors one considers, when engaging in necessary multiple relationships is okay, and how they are managed is key.

Important Considerations

In keeping with the information shared above, it is important to take a flexible approach to boundaries and multiple relationships that takes into consideration the many factors addressed above. Our clients’ best interest and the promotion of their treatment goals should always guide us. Further, it is important to consider the guidance provided by the APA Ethics Code (APA, 2010), to access the wisdom of colleagues when faced with dilemmas and unclear situations, and to utilize a decision-making process to assist us in making these decisions.

+41

-3

I Would Never Do That!

In graduate school, I had an ethics class (actually, three 1-credit classes) which repeatedly discussed how to avoid boundary crossings and violations. During my pre-doctoral internship orientation, I was handed a pamphlet entitled “Therapy Never Includes Sex,” and expected to read the pamphlet and sign a statement indicating I read the pamphlet. In my current state (Colorado), the licensing board requires psychologists to discuss how to report sexual intimacies during the initial session as a part of the mandatory disclosure. Colleagues have made their students raise their hand and take a vow (half in jest) to not have romantic and sexual relationships with clients. Despite all these warnings, sexual boundary violations continue to rank high on the list of ethical complaints and violations made by psychologists.

During my pre-doctoral internship orientation, I was handed a pamphlet entitled “Therapy Never Includes Sex,” and expected to read the pamphlet and sign a statement indicating I read the pamphlet. In my current state (Colorado), the licensing board requires psychologists to discuss how to report sexual intimacies during the initial session as a part of the mandatory disclosure. Colleagues have made their students raise their hand and take a vow (half in jest) to not have romantic and sexual relationships with clients. Despite all these warnings, sexual boundary violations continue to rank high on the list of ethical complaints and violations made by psychologists.

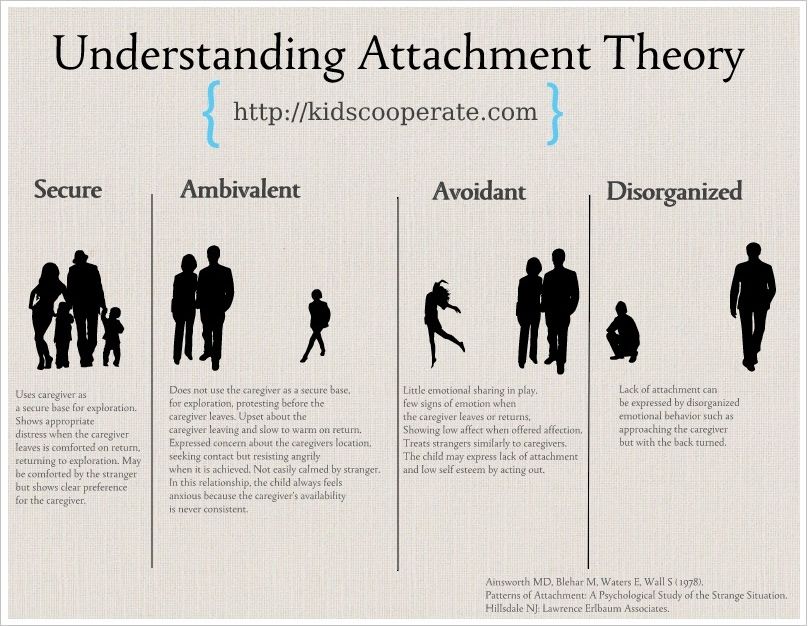

Sexual attraction is a normative experience; therefore, it should be expected individuals may experience attraction in the therapeutic context. Indeed, Freud highlighted therapist-to-client attraction experiences in his 1915 article Observations of Transference Love. Research has indicated that between 70% and 90% of psychotherapists have been attracted to at least one client in their career (Pope, Keith-Spiegel, & Tabachnick, 2006; Rodolfa et al. , 1994). Moreover, over 80% of clinical psychologists have reported knowing a colleague who claimed to have been sexually intimate with a client (Noel, 1988). Though attraction to clients isn’t necessarily unethical—indeed, a majority of therapists have viewed these feelings as being ethical (Meek & McMinn, 1999; Pope, Tabachnick, & Keith-Spiegel, 1987)—if the attraction is compromising their objectivity and/or competence, these feelings should be confronted and addressed (Capawana, 2016). While much of the literature on sexual boundary violations focuses on the scope of the problem and training programs focus on telling trainees not to engage in these violations, little time is spent on how to effectively manage sexual attraction to clients.

, 1994). Moreover, over 80% of clinical psychologists have reported knowing a colleague who claimed to have been sexually intimate with a client (Noel, 1988). Though attraction to clients isn’t necessarily unethical—indeed, a majority of therapists have viewed these feelings as being ethical (Meek & McMinn, 1999; Pope, Tabachnick, & Keith-Spiegel, 1987)—if the attraction is compromising their objectivity and/or competence, these feelings should be confronted and addressed (Capawana, 2016). While much of the literature on sexual boundary violations focuses on the scope of the problem and training programs focus on telling trainees not to engage in these violations, little time is spent on how to effectively manage sexual attraction to clients.

Scope

Many researchers have sought to examine the incidence of sexual behavior between therapists and their clients. Alpert and Steinberg (2017) conducted an extensive review of the literature on sexual boundary violations and therapists’ sexual attraction to clients and found reported rates of sexual contact between psychologists and clients in the United States ranging from 7% to 12% across studies; with some researchers suggesting the true prevalence is much higher. An estimated 80% of reported sexual boundary violation victims were women. Sexual attraction toward clients is reported more frequently. Pope, Keith-Spiegel, and Tabachnick (2006) conducted a survey of 585 psychologists (57.9% of the sample were men, 42.1% were women) asking about their sexual attraction to psychotherapy clients. Only 77 respondents reported never being sexually attracted to clients. Of the 508 respondents who reported attraction to clients, 125 reported attraction to male clients only, 281 to female clients only, and 102 to both male and female clients. Eighty-two percent of respondents reported they had never seriously considered actual sexual involvement with a client. Of those who did consider sexual involvement (N = 104), 91 stated they had only considered it once or twice, with male therapists considering sexual involvement more than female therapists (27% vs. 5%). Lastly, nearly half of therapists indicated their sexual attraction had a negative influence on the therapeutic relationship.

An estimated 80% of reported sexual boundary violation victims were women. Sexual attraction toward clients is reported more frequently. Pope, Keith-Spiegel, and Tabachnick (2006) conducted a survey of 585 psychologists (57.9% of the sample were men, 42.1% were women) asking about their sexual attraction to psychotherapy clients. Only 77 respondents reported never being sexually attracted to clients. Of the 508 respondents who reported attraction to clients, 125 reported attraction to male clients only, 281 to female clients only, and 102 to both male and female clients. Eighty-two percent of respondents reported they had never seriously considered actual sexual involvement with a client. Of those who did consider sexual involvement (N = 104), 91 stated they had only considered it once or twice, with male therapists considering sexual involvement more than female therapists (27% vs. 5%). Lastly, nearly half of therapists indicated their sexual attraction had a negative influence on the therapeutic relationship.

Re-Visiting the Ethical Principles

Sexual relationships with clients are considered a boundary violation, which refers to transgressions that impact the therapeutic relationship. In the APA’s 2017 Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (Code of Ethics), the guidelines regarding sexual relationships with current therapy clients are quite clear and explicit, stating in 10.05 Sexual Intimacies With Current Therapy Clients/Patients: “Psychologists do not engage in sexual intimacies with current therapy clients/patients” (p. 14). Other guidelines related to boundary violations center on non-maleficence and the potential for harm (e.g., 3.04 Avoiding Harm; 3.08 Exploitative Relationships).

For previous therapy clients, there are two areas within guideline 10.08 Sexual Intimacies With Former Therapy Clients/Patients that guide psychologists in their ethical decision-making. First, psychologists should not engage in sexual intimacies with former clients for at least two years after the termination of therapy. This is followed by, “psychologists do not engage in sexual intimacies with former clients/patients even after a two-year interval except in the most unusual circumstances” (p. 14). The Code of Conduct enumerates different factors to consider, focused on examining the potential for exploitation, including the nature, duration, and intensity of the therapy; the circumstances around termination of therapy; the client’s personal history; and the likelihood of adverse impact. However, these guidelines have been controversial, as some psychologists subscribe to the notion of “once a client, always a client”—and therefore advocate avoiding any intimate relationships with clients, ever.

This is followed by, “psychologists do not engage in sexual intimacies with former clients/patients even after a two-year interval except in the most unusual circumstances” (p. 14). The Code of Conduct enumerates different factors to consider, focused on examining the potential for exploitation, including the nature, duration, and intensity of the therapy; the circumstances around termination of therapy; the client’s personal history; and the likelihood of adverse impact. However, these guidelines have been controversial, as some psychologists subscribe to the notion of “once a client, always a client”—and therefore advocate avoiding any intimate relationships with clients, ever.

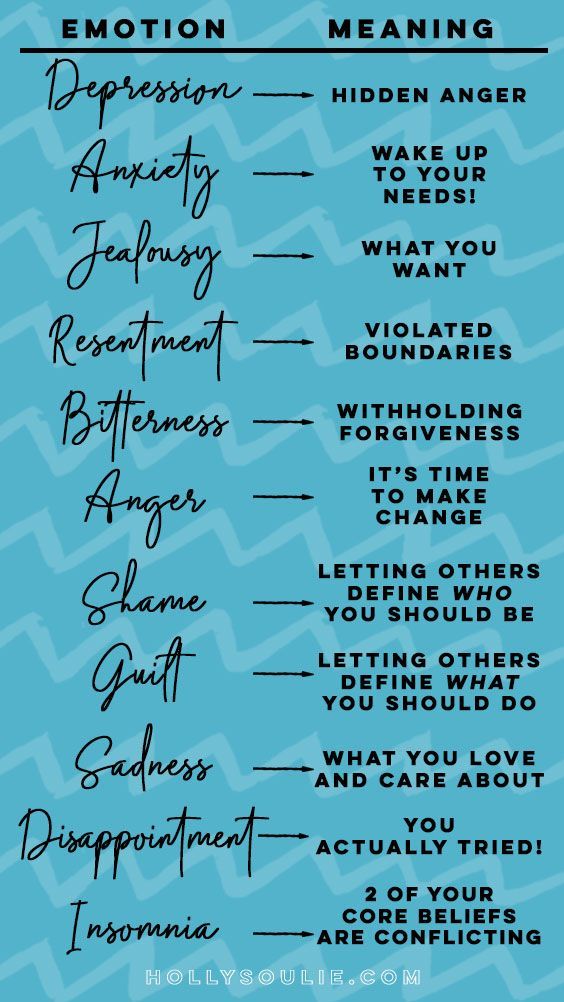

Ultimately, sexual relationships with clients result in harmful, deleterious consequences (Pope, 2001). Clients typically describe these incidents as painful and/or traumatic. Commonly described reactions to such incidents include ambivalence, cognitive dysfunction, shame, PTSD symptoms, emptiness and isolation, distrust, guilt, boundary and sexual confusion, and increased suicidal risk (Disch, 2006; Pope, 2001). Consequences for sexual boundary violations are varied. Potential consequences include sanctions from professional organization and licensing boards, ostracism and isolation from colleagues, legal fines and consequences, family conflict, and, ultimately, damage to the reputation of the field of psychology (Koocher & Keith-Spiegel, 2008; Pope, Sonne, & Greene, 2006).

Consequences for sexual boundary violations are varied. Potential consequences include sanctions from professional organization and licensing boards, ostracism and isolation from colleagues, legal fines and consequences, family conflict, and, ultimately, damage to the reputation of the field of psychology (Koocher & Keith-Spiegel, 2008; Pope, Sonne, & Greene, 2006).

Creating Space

What if a trainee or a psychologist experiences a sexual attraction towards a client? Where do they turn to for help? Are supervision environments welcoming places to discuss their feelings? Though I am an early career professional, I still have yet to have a student or trainee express they are sexually or romantically attracted to a client, despite the prevalence rates noted above.

Scholars have stated the Ethical Principles and Code of Conduct do not offer guidelines for therapists who develop sexual attractions to their clients nor whether therapists should disclose such information to their clients (Capawana, 2016; Fisher, 2004). In the previously described Pope and colleagues (2006) study, 55% of respondents indicated they had received no education about sexual attraction to clients. In order to manage sexual feelings, clinicians often make attempts to address their feelings. Some discuss their feelings in supervision or consultation with colleagues, while others address them in their own psychotherapy (Blanchard & Licthenberg, 1998; Pope et al., 2006b; Rodolfa et al., 1994). Further, in the previously mentioned Pope et al. (2006a) study, only 57% of respondents reported they sought supervision or consultation upon becoming aware of their feelings of sexual attraction to a client, with younger therapists being more likely to seek consultation (64% versus 50%), and no gender differences observed. Those who had at least some training about sexual attraction to clients were more likely to seek consultation.

In the previously described Pope and colleagues (2006) study, 55% of respondents indicated they had received no education about sexual attraction to clients. In order to manage sexual feelings, clinicians often make attempts to address their feelings. Some discuss their feelings in supervision or consultation with colleagues, while others address them in their own psychotherapy (Blanchard & Licthenberg, 1998; Pope et al., 2006b; Rodolfa et al., 1994). Further, in the previously mentioned Pope et al. (2006a) study, only 57% of respondents reported they sought supervision or consultation upon becoming aware of their feelings of sexual attraction to a client, with younger therapists being more likely to seek consultation (64% versus 50%), and no gender differences observed. Those who had at least some training about sexual attraction to clients were more likely to seek consultation.

Therapist disclosure of their sexual feelings to their client is a controversial topic. Research indicates rates of therapist disclosure of their sexual attraction ranges from 5% to 25% (Fisher, 2004). However, the ethics behind such disclosure have been questioned due to the potential for harm to the client. Fisher (2004) provides several recommendations to therapists who are experiencing sexual feelings for clients, arguing that self-disclosure of sexual attraction to clients should be avoided and can be considered unethical professional behavior. Additional recommendations highlight the importance of supervision, consultation, personal therapy, and didactics throughout the career span. Finally, graduate training programs need to discuss sexual feelings and attractions, self-disclosure, and professional boundaries early and frequently throughout the duration of clinical training and supervision, particularly in manner that avoids shaming.

However, the ethics behind such disclosure have been questioned due to the potential for harm to the client. Fisher (2004) provides several recommendations to therapists who are experiencing sexual feelings for clients, arguing that self-disclosure of sexual attraction to clients should be avoided and can be considered unethical professional behavior. Additional recommendations highlight the importance of supervision, consultation, personal therapy, and didactics throughout the career span. Finally, graduate training programs need to discuss sexual feelings and attractions, self-disclosure, and professional boundaries early and frequently throughout the duration of clinical training and supervision, particularly in manner that avoids shaming.

Conclusion

As expected, sexual attraction to clients is commonplace. Although attraction to clients isn’t necessarily unethical, the literature highlights the need to engage in conversations about sexual attraction toward clients. Moreover, although not all psychologists engage in inappropriate sexual behaviors with clients, many have reported their feelings of sexual attraction have negatively impacted their therapeutic engagement with clients. In sum, it is important for mental health providers at all career stages to open space to have discussions with colleagues and other professionals (i.e., personal psychotherapy) to navigate how to address these feelings before a boundary violation occurs.

In sum, it is important for mental health providers at all career stages to open space to have discussions with colleagues and other professionals (i.e., personal psychotherapy) to navigate how to address these feelings before a boundary violation occurs.

+3

0

Limits in therapy //Psychological newspaper

“One of the invaluable things that the patient learns in the course of psychotherapy is the boundaries of the relationship. He learns what he can get from others, but also - and this is much more important - what he cannot get from others.

A.A. Nesterova "Professional ethics of a psychologist"

Understanding the importance of boundaries in therapeutic work did not come to me immediately. After graduating from the institute and having received several additional educations in the field of psychology, I finally began my psychological practice. I did not feel confident enough, but my knowledge, my desire to help, sincerity and empathy were encouraging in my ability to be useful to the client. I was certainly aware of the importance of clarifying the request, contracting, and other components of the therapeutic framework. But, unfortunately, no one told me that as soon as I start practicing, my personal, and not always easy, work with boundaries will begin. No one warned me that my own relationship with my boundaries would begin to make itself felt from the very first client. That they will manifest themselves in the form of an inability to say “no”, an exaggerated desire to take care of the client, feelings of guilt, anger at oneself, in a lack of understanding and ignorance of what to do and how to do it “right”. And that practically every client during the first few years will become a teacher for me. Until I experience first hand all the intricacies of setting boundaries in a therapeutic relationship. Until I myself find the line that protects both of us at once - both me and my client.

Understanding the importance of establishing clear, clear and fair boundaries of therapy was formed in me gradually, through personal experience in several directions. The first - and main - was my work with clients. Each client brought with them new "issues" related to the boundaries that I had to solve. I observed the client's reactions, my own reactions, the successes (failures) of therapy following resolution of boundary issues, changes in the therapeutic relationship. The second important source of information about boundaries is personal therapy, which I went through for eight years. During this time, I had the experience of long work with two psychologists and introductory sessions with several more. I observed their handling of therapy and relationship boundaries and tracked my reactions as a client. The third source was communication with colleagues. I was amazed at how differently psychologists (even those with extensive experience) deal with boundaries. Someone does not designate them at all, someone deliberately violates them, someone was exaggeratedly strict in this matter, and someone did not know at all that they exist! The fourth source, which did not provide as much information as the first three, but was still useful, was my clients' stories about their experiences in therapy with other psychologists.

The first conclusion that I made after several years of observation is that the issue of boundaries is of paramount importance in the work of a psychologist. Around the same time, I came to a lecture by a female psychoanalyst. There I heard a phrase that confirmed all my observations: “Working with an analyst is a dish of a horse and a canary. Where the horse is the personality of the psychologist, and the canary is the methods and approaches that he uses. I was delighted! It was exactly what I had guessed, but could not explain. It's all about the psychologist's ability to create the "right" therapeutic space.

The second conclusion was that the "correct" (i.e., safe and "healing") therapeutic space is created through the establishment and maintenance of boundaries.

The third conclusion is that boundaries cannot be established simply by knowing the theory. It needs to be lived, felt with each client. And each time these boundaries can be different, they can change from client to client or with one client in the course of therapy. That the relationship "therapist-client" is a living mobile entity that periodically tries to move beyond the boundaries or shift them. And not always these attempts come only from the client. And the therapist is the one who is responsible for observing, controlling, analyzing, and interpreting (or otherwise using) the boundary processes for the benefit of the client.

That the relationship "therapist-client" is a living mobile entity that periodically tries to move beyond the boundaries or shift them. And not always these attempts come only from the client. And the therapist is the one who is responsible for observing, controlling, analyzing, and interpreting (or otherwise using) the boundary processes for the benefit of the client.

Later I got acquainted with the analytical literature on this topic. It turned out that this issue has been discussed and regulated for a long time.

External and internal limits of therapy

“Only what is divided can then be put together in the right way. Only where there is distance is a meeting in private possible.”

C. G. Jung

The problem of boundaries in therapy has risen in psychoanalysis in the last century. In recent years, there has been an increased interest in this topic. Perhaps this is due to the popularization of psychology. The increased demand for the services of psychologists has led to an increase in offers in this market. At the same time, the quality of training of psychologists is getting lower and lower. A large number of psychological schools and directions have appeared that focus mainly on methods of therapy and do not take into account the relationship "analyst-patient" at all. They also forget about the need for personal therapy for specialists.

At the same time, the quality of training of psychologists is getting lower and lower. A large number of psychological schools and directions have appeared that focus mainly on methods of therapy and do not take into account the relationship "analyst-patient" at all. They also forget about the need for personal therapy for specialists.

Many authors note the special importance of this topic. So, A.V. Rossokhin writes that “there is no other more important topic in psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic practice than the problem of external and internal boundaries. Without strict adherence to the psychoanalytic setting… psychoanalysis cannot take place” (Gabbard, Lester, 2014).

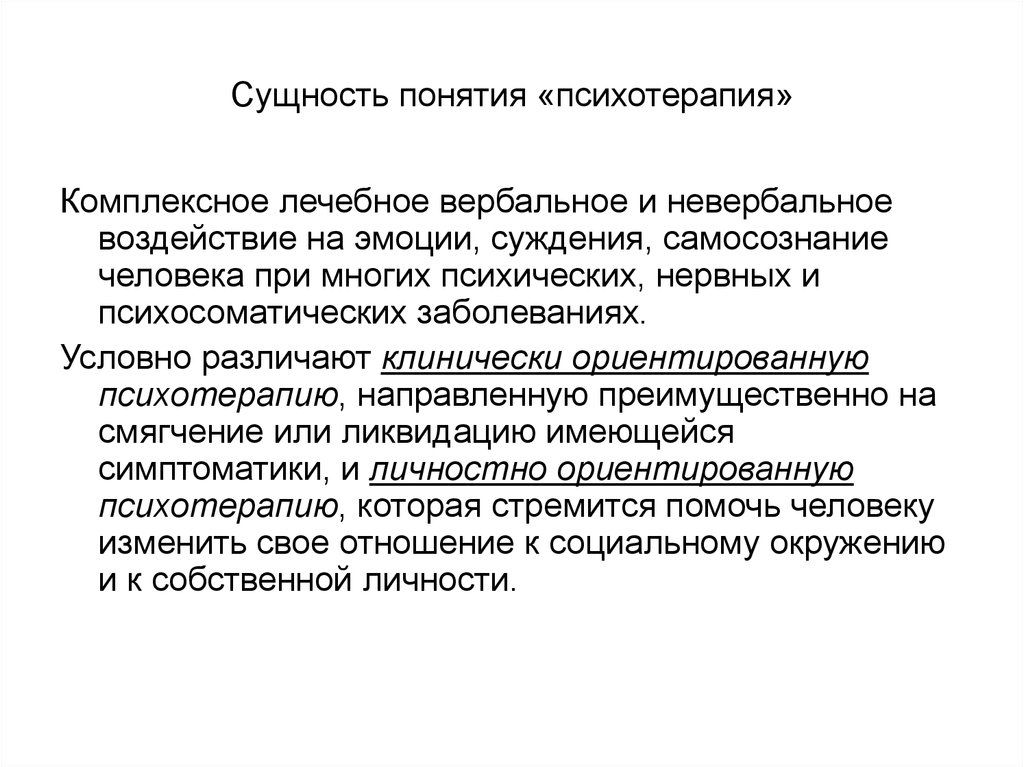

Boundaries in analysis (therapy) can be divided into external and internal.

External borders

Outer Boundaries is what is called a setting or analytic frame. This is a set of rules, conditions, agreements, in accordance with which the analytical process takes place. This includes agreements on the place, time, frequency of sessions, amount of payment, passes, holidays and vacations. The outer boundaries create a frame, are the walls, according to Jung, "a well-sealed vessel" within which the sacrament of therapy will take place. This metaphor contains the meaning of tightness, the preservation of the content, i.e. strong outer boundaries that protect the inner space of therapy.

This includes agreements on the place, time, frequency of sessions, amount of payment, passes, holidays and vacations. The outer boundaries create a frame, are the walls, according to Jung, "a well-sealed vessel" within which the sacrament of therapy will take place. This metaphor contains the meaning of tightness, the preservation of the content, i.e. strong outer boundaries that protect the inner space of therapy.

Gabbard defines the analytic frame as “the envelope in which the treatment takes place. While this notion conjures up the image of a framework, it is not as rigid. Rather, it is a dynamic and flexible set of conditions that reflect the analyst's ongoing efforts to respond to the patient while creating the best environment for analytic work" (Gabbard and Lester, 2014).

Dieckmann calls the setting of the boundaries of analysis an "individual ritual", emphasizing the individual approach to each patient in the issue of setting analytic boundaries. “Awareness ... of the meaning of creating an “individual ritual” is necessary for the process of individuation to become real, and you come into contact with archetypal images. Moreover, individual rituals also provide adequate protection to undertake the perilous descent into the BSZ and return unscathed after a nighttime sea voyage” (Dieckmann, 2001).

“Awareness ... of the meaning of creating an “individual ritual” is necessary for the process of individuation to become real, and you come into contact with archetypal images. Moreover, individual rituals also provide adequate protection to undertake the perilous descent into the BSZ and return unscathed after a nighttime sea voyage” (Dieckmann, 2001).

If the outer boundaries are built, if they are strong and reliable, then this gives the patient a feeling of stability, permanence and security. And also allows you to fully focus on internal processes. Otherwise, the patient will be constantly frustrated, not knowing what awaits him at the session - whether the psychologist will come on time or be late, how much money they will take from him, whether he will be refused admission, etc.

I cannot help but give an example that was told to me by one of my clients, who, choosing a psychologist for herself, visited about 20 specialists. One of the psychologists, pointing out the rules of the setting to her, said: “If you do not do your homework, I can charge you a fine in the amount of the cost of the session. And I can at any time, without warning, refuse you therapy. Apparently, this psychologist wanted to motivate the patient to do her homework. Of course, homework is important, but, in my opinion, the atmosphere in the office and the feelings with which the patient goes to the psychologist are even more important. Are we turning into directive parents by imposing punishments? Are we assigning the patient the role of a "loser" with all the feelings inherent in this role? Are we depriving the client of the unconditional acceptance that is so important for his self-disclosure in analysis? And will the homework done in this way benefit him?

And I can at any time, without warning, refuse you therapy. Apparently, this psychologist wanted to motivate the patient to do her homework. Of course, homework is important, but, in my opinion, the atmosphere in the office and the feelings with which the patient goes to the psychologist are even more important. Are we turning into directive parents by imposing punishments? Are we assigning the patient the role of a "loser" with all the feelings inherent in this role? Are we depriving the client of the unconditional acceptance that is so important for his self-disclosure in analysis? And will the homework done in this way benefit him?

If we take as a basis the classification of boundaries given by me in the book "Boundaries of the Personality" (Kryuchkova, 2020), and impose it on the analytical process, then we will get such a scheme of the external boundaries of analysis .

1. Temporary s e limits . They include agreements on the duration and frequency of sessions, lateness, skips, delays, additional sessions, etc. Temporal s e boundaries define the boundaries of the therapeutic session, its beginning and end. This type of border protects temporary to the analysis frame from reducing or increasing the duration of the session, from the abuse of the time of the analyst or the patient.

Temporal s e boundaries define the boundaries of the therapeutic session, its beginning and end. This type of border protects temporary to the analysis frame from reducing or increasing the duration of the session, from the abuse of the time of the analyst or the patient.

I will give an example of my colleague. She talked about her analyst, who was constantly late. And she, waiting in the corridor near his office, each time lived through the same chain of feelings: at first she felt unwanted, then she got angry, and then she lost the desire to discuss personal topics with the analyst. As a result, she left the analysis.

2. Territorial boundaries . Designate the place where the meetings will take place, as well as the location in space of the seat for the client and the workplace of the analyst. The territory where therapy takes place should be closed, permanent, convenient for the client and the analyst. Otherwise, how can the client feel secure or allow himself to express his rising affect?

Clients have told me about psychologists who do therapy sessions in cafes. But then you need to understand that there can be no talk of any deep inner work. A cafe, even the most deserted, cannot be considered a safe place, a “well-sealed vessel.” Sessions in a cafe are more like friendly gatherings over a cup of coffee.

But then you need to understand that there can be no talk of any deep inner work. A cafe, even the most deserted, cannot be considered a safe place, a “well-sealed vessel.” Sessions in a cafe are more like friendly gatherings over a cup of coffee.

In my practice, there was a case when a client (of the borderline level), a few days before the scheduled session, asked me to conduct a session at her home due to her child's illness and the inability to leave her daughter at home alone. I refused, it caused her resentment and anger. For a while, she even stopped therapy. Then, when we continued, it turned out that this request was not at all connected with the child's illness. In fact, she hoped that after sitting and talking at home, we would get closer and later be able to become friends.

This example illustrates that our patients may have a very different meaning to requests, gifts, or other ways to violate boundaries. It is important to reveal this meaning and discuss it. And if we simply go along with the patient, then we will lose valuable information and will not allow material important for therapy to come out.

And if we simply go along with the patient, then we will lose valuable information and will not allow material important for therapy to come out.

3. Material boundaries . These boundaries concern, firstly, financial calculations. They indicate the cost of a therapy session. Some analysts prefer a fixed cost for all patients, others assign it to each patient individually, depending on the material wealth of each analysand. The main thing is that the indicated boundaries of calculations (in terms of the amount and time of calculation) are respected by both the patient and the analyst. It is unacceptable for an analyst to, for example, take pity on a client and reduce his cost or allow him to attend sessions on credit. Kernberg also notes the importance of the analysand paying for the sessions himself.

M. Jacobi notes that payment issues are directly related to the patient's conscious or unconscious self-esteem. And he summarizes: “I think it’s very good to have a certain average standard of payment, which is determined on the basis of general considerations, your own conscious self-assessment and the ratio of your professional level to your idea of the standard level of an analyst” (Jacobi, 2007).

And he summarizes: “I think it’s very good to have a certain average standard of payment, which is determined on the basis of general considerations, your own conscious self-assessment and the ratio of your professional level to your idea of the standard level of an analyst” (Jacobi, 2007).

The second important aspect of material boundaries is things, furniture, objects that are in the analyst's office or belong to the analyst. The material boundaries keep it all intact. If the patient violates these boundaries, for example, breaks something, he must pay for the repair of this thing. And, of course, what happened should be subject to discussion and interpretation. Otto Kernberg gives an example of how one patient came to the session with scissors and cut all the plants in his office. Kernberg announced to her that the therapy would only continue when she paid for all the damaged plants or brought the same ones.

Material boundaries, as well as other types of boundaries, make it possible to maintain regulated analytical relations, without the admixture of various kinds of help and intersections. Everything in the analyst's office is his responsibility. If the client caused damage, he must pay for it, but if the analyst suffered damage, he himself restores what was damaged, of course, without the help of the client.

Everything in the analyst's office is his responsibility. If the client caused damage, he must pay for it, but if the analyst suffered damage, he himself restores what was damaged, of course, without the help of the client.

I will give an example from my practice. The door in my office didn't close properly. Before I had a chance to resolve this issue, my client showed up for another session with a suitcase of tools and with a determined attitude to fix everything. I refused his help, and this caused him strong emotions, which became the subject of several consultations. This situation revealed his early childhood experiences, defenses and adult strategies of behavior. These were very helpful for a therapy session.

The third aspect of material boundaries is gifts from patients. And here the rule is the same: ideally, do not take gifts. Although I think the situations are different. I think it is necessary to take into account the stage of analysis, the strength of the patient's ego, the value of the gift, and only then make a decision.

In The Therapist's Workbook R. Langs gives the example of a male patient giving a book to his female analyst and interpreting this through analysis of the patient's dreams and life events. “The therapist's acceptance of a gift from the patient signifies physical contact and mutual need—dependence… The therapist's acceptance of a gift is also associated with a failure to establish clear and distinct interpersonal boundaries between her and the patient” (Langs, 2003).

4. Body boundaries . This kind of boundary applies to any kind of bodily contact - hugs, touches, handshakes, etc. Some clients seek this, but physical contact is undesirable, and attempts to obtain it are subject to discussion and interpretation. Although this rule is quite strict, I would like to give an example from Dieckmann's book , which illustrates the possibility of allowing boundary violations for therapeutic purposes, provided that the analyst really believes that this will benefit the patient. “One very experienced elderly colleague once spoke to a small circle of professionals about her work with a schizophrenic patient. At a very specific moment, the analyst lay down on the couch behind the patient so that she could feel some physical warmth. This allowed the psychotic patient, for the first time in her life, to experience a real relationship with another person. And from that moment on, the analysis took the right direction in her treatment” (Dieckmann, 2001).

“One very experienced elderly colleague once spoke to a small circle of professionals about her work with a schizophrenic patient. At a very specific moment, the analyst lay down on the couch behind the patient so that she could feel some physical warmth. This allowed the psychotic patient, for the first time in her life, to experience a real relationship with another person. And from that moment on, the analysis took the right direction in her treatment” (Dieckmann, 2001).

5. Limits of arrangements . This type concerns any arrangements that may arise in the course of therapy between the therapist and the client. As with other types of boundaries, the analyst must respect them, and any transgressions on the part of the patient are subject to discussion or interpretation.

6. Information boundaries . This is a very important type of border. It includes a privacy rule. The analyst ensures that all the information voiced by the client does not go beyond these walls and their relationship. Moreover, it is important that it works not only in relation to strangers, but also concerns the patient's relatives. It would be good if this rule works the other way too - the analyst will not provide the patient with information about himself and will not advertise the details of his life.

Moreover, it is important that it works not only in relation to strangers, but also concerns the patient's relatives. It would be good if this rule works the other way too - the analyst will not provide the patient with information about himself and will not advertise the details of his life.

7. Relationship boundaries . This type of boundary protects, on the one hand, everything that happens within these relations from the inclusion of third parties, and on the other hand, protects the established type of relationship. The therapeutic relationship should remain as such and should never become a friendship, business or love relationship. The analyst, firstly, must himself observe these boundaries, and secondly, explain to the client the importance of him, for his part, also respecting the boundaries of their relationship and not sharing with anyone what is happening in the session.

Qualities of external borders. Analysis limits must be:

- reliable.

Designated by the analyst and agreed upon by the analysand, they must be supported and respected by both parties. Frame violations are not allowed for the analyst. And violations on the part of the analysand are material for analytic work;

Designated by the analyst and agreed upon by the analysand, they must be supported and respected by both parties. Frame violations are not allowed for the analyst. And violations on the part of the analysand are material for analytic work; - flexible. It is good if the analyst does not just work with each patient according to a certain set of rules, but has the opportunity to adjust his rules to the wishes of the patient. “Just as healthy ego boundaries should be flexible enough to open at some moments and close at others, so analytic boundaries should be flexible enough to adapt to conditions depending on the needs of the analytic process” (Gabbard, Lester, 2014).

“In analytical psychology, the need for the constancy of the frame is recognized, but its elasticity, the flexibility of “boundary requirements,” is also emphasized. At various points in the analysis, the frame can slightly expand or contract without harm to the patient and the analyst, and the analytical boundaries can change their permeability” (Kalinenko, 2011).

“The analytic rules, “when, how and where” to apply them, are not entirely left to the creativity of the analyst, but rather are determined by the creativity that comes from the general BSZ processes that create a meaningful and goal-oriented order” (Dieckmann, 2001).

It is important for the analyst to find a balance between two opposites: keeping clear and permanent boundaries, on the one hand, and allowing for the possibility of boundary variability. According to Dieckmann, “It would be wrong to extend the sessions because it is difficult for you to say no and because of your difficulties in separation (separation, parting). And it would be wrong not to extend the sessions because of your too strong persona conditioning, thus not giving space to the living process of analysis” (Dieckmann, 2001).

Internal borders

The concept of the internal boundaries of analysis is harder to see, feel, and harder to define. Internal boundaries are invisible ingredients by which everything entering the therapeutic vessel is boiled, processed, ordered and turned into components of a healing “medicine” for the patient. Responsibility for maintaining internal boundaries lies with the therapist. He not only must observe them himself, but also withstand the onslaught of unconscious material (his own and the patient's) that tries to mix up, erase some of the boundaries.

Responsibility for maintaining internal boundaries lies with the therapist. He not only must observe them himself, but also withstand the onslaught of unconscious material (his own and the patient's) that tries to mix up, erase some of the boundaries.

“The analytic situation is the totality of the elements that make up the analytic relationship: at the very heart of these relationships, over time, we can observe a process, the knots of which are tied up through transference and countertransference due to the establishment of the analytic setting and the restrictions it imposes” (Greene, 2022).

In my opinion, the internal boundaries of analysis are made up of several interrelated, intersecting aspects.

1. Analytical distance . Freud's classical analytic distance assumed that the analyst would remain a "blank slate" for the patient, a "projection screen". Jung defined it a little differently. "... Jung's understanding of analysis as a dialectical process between analyst and patient made the analyst visible and transparent to the patient, which prevented the appearance of such an almost schizoid distance between two people" (Dieckmann, 2001).

In my understanding, analytic distance is a boundary that protects the analyst's professional identity. She is responsible for maintaining the therapist's professional role, forbidding conscious intersection with the patient in any other contexts and circumstances, forbidding friendships and any social relationships. As well as keeping the details of his personal life secret. If we break this rule, then something else enters the closed vessel of analytic interaction, interfering with the pure process of healing transformation. Jung used the alchemical metaphor to represent the private nature of what analysis contains. The contents of the vessel must not be spilled into the outside world - this is dangerous, and it must also be protected from the invasion of harmful elements of the environment and mixing with them.

2. Technical neutrality . Otto Kernberg described it as "keeping the right distance from those forces that give rise to the patient's internal conflicts, this is not a lack of warmth or empathy. " Of course, any therapy requires the therapist to be capable of genuine warmth and empathy. After all, without this, it will not be possible to create a space of acceptance. In addition, the therapist must be able to “feel what the patient cannot bear within himself. This also lies in the ability of the therapist to integrate – on cognitive and emotional levels – what is currently dissociated and split in the patient” (Kernberg, 2014).

" Of course, any therapy requires the therapist to be capable of genuine warmth and empathy. After all, without this, it will not be possible to create a space of acceptance. In addition, the therapist must be able to “feel what the patient cannot bear within himself. This also lies in the ability of the therapist to integrate – on cognitive and emotional levels – what is currently dissociated and split in the patient” (Kernberg, 2014).

Technical neutrality is the boundary that separates the symbolic from the real. Without respecting this boundary, it is impossible to contain and work with transference and countertransference.

The concept of containerization was introduced by W. Bion . The analyst is supposed to be an empty container for the patient into which he can place any of his feelings. In Bion's words, "The process of containment is carried out if the container and the contents (mother and infant, analyst and patient) are so close that the message can be fully received. But at the same time, sufficient distance is needed that allows the mother (or analyst) , and then the child himself to think, to distinguish what refers to one and what to another member of the couple" (Fonda, 2018).

But at the same time, sufficient distance is needed that allows the mother (or analyst) , and then the child himself to think, to distinguish what refers to one and what to another member of the couple" (Fonda, 2018).

The work of a psychologist a priori implies the presence of a container, since our clients always bring us something - feelings, experiences, affects, thoughts, states. But sometimes it happens that the container ends where something personal begins. And only a strong container can contain everything that accompanies the phenomena of transference and countertransference.

The phenomenon of transference has been known since the time of Freud. During this time, it has already been sufficiently studied and described by various authors. Its essence is that "the neurotic disability of the patient is now transferred to the doctor" (Jung, 1997).

“Transference is not only a repetition of past experience, it is also the patient’s version of the analytic couple’s shared reality” (Kast, Proner, 2022).

Kernberg proposes to consider transference not only as a repetition of past experience, but also “as the construction of new relationships that have value also due to the fact that they are built together with the help of interpretation” (Lec. on Differential Diagnosis, 2018).

If the analyst does not respect the boundary of technical neutrality (the boundary of the real and the symbolic), then he will inevitably identify with the patient's projections or be led by his countertransference feelings. And then it will not be possible either to provide the patient with a container, or to interpret, or to build a new model of relationships in the patient.

Countertransference is the projection of the analyst onto the patient, “…and it can range from a neurotic denial of the transference to a way of gaining valuable information about the patient through constant introspection of the analyst’s experiences” (Perry, 2022).

It is countertransference reactions that are frequent causes of boundary violations by the analyst. Under the influence of countertransference, the analyst can shift the boundaries in one direction or another: either negative (negative feelings towards the patient - rejection, hostility, contempt, aggression, fear), or conditionally positive (feeling of pity for the patient, desire to take care, help, etc.). d.). In both cases, it interferes with therapy. In the negative version, the patient may be re-traumatized, and in the positive version, the patient may be deprived of the opportunity to grow up. And in both cases, he will not get a new experience of a more “healthy” interaction. And the analyst will lose valuable information about the patient. After all, the patient represses and contains what is especially difficult for him to meet. According to Jung, the patient unconsciously projects onto the analyst what is still unknown in order to learn something new about himself.

Under the influence of countertransference, the analyst can shift the boundaries in one direction or another: either negative (negative feelings towards the patient - rejection, hostility, contempt, aggression, fear), or conditionally positive (feeling of pity for the patient, desire to take care, help, etc.). d.). In both cases, it interferes with therapy. In the negative version, the patient may be re-traumatized, and in the positive version, the patient may be deprived of the opportunity to grow up. And in both cases, he will not get a new experience of a more “healthy” interaction. And the analyst will lose valuable information about the patient. After all, the patient represses and contains what is especially difficult for him to meet. According to Jung, the patient unconsciously projects onto the analyst what is still unknown in order to learn something new about himself.

Casement expresses a similar meaning in other words. He says that "patients help shape psychotherapeutic treatment and create therapeutic experiences that are, as a result, able to discover themselves" (Casement, 1995). That is, patients kind of tell the therapist where to move in therapy. And the analyst, ignoring the prompts of the patient and mistaking the symbolic for the real, can go in a completely different direction.

That is, patients kind of tell the therapist where to move in therapy. And the analyst, ignoring the prompts of the patient and mistaking the symbolic for the real, can go in a completely different direction.

3. Analyst's sincerity . This is the line that separates sincerity from lies. Most of our patients saw in their lives, and especially in childhood, a lot of insincerity, pretense and manipulation. And it seems to me very important that in the general space of therapy there is sincerity (in relationships, in expressing oneself). The analyst, by his example and willingness to accept the patient as he is, creates an opportunity for sincerity, openness and trust.

The therapeutic relationship involves a special kind of intimacy that is only possible through the sincere involvement, empathy, acceptance, and empathy of the analyst. Only when all these components are present will the patient be able to admit the analyst to the most frightening aspects of his personality and be ready to explore and accept them with the therapist.

“Apparently, only in a sincere relationship with the analyst and his “extraordinarily caring hand” can the unconscious activate the patient’s internal ability to reveal the meaning of what is happening, and new images will surface” (Wiener, 2011).

Golden Psyche

Svetlana Alexandrovna Malkina

nominee

based on the results of 2021

Violation of personality boundaries: the content and technologies of psychological assistance

Read more

“Analysis will not advance if contact is limited to masks of rationality and reasonableness. The analyst and the patient participate in it as whole persons, using their animas (souls). Analytic relationships lead them to the unconscious depths of the personality, like any other intimate relationship, love or friendship, when important archetypal images are constellated from the collective unconscious, providing emotional attraction ”(Dieckmann, 2001).

Reflections on the therapeutic neutrality and sincerity of the analyst can be summed up with a quote from Kalinenko: “The analyst must maintain a certain distance in order to function as a professional. But at the same time, this distance should not exceed the dimensions of the zone within which the analyst retains the ability for sensory interaction with the patient” (Kalinenko, 2011).

Otto Kernberg in his model of TFT (transference focused therapy) identifies four main techniques: maintaining technical neutrality, analysis of the transference, interpretation and working with countertransference. As we can see, all of them (except interpretation) are varieties of internal boundaries of therapy. That is, in order to "treat" the patient, it is enough just to respect the boundaries, internal and external.

Both external boundaries and internal ones serve the same purpose - to create a transformational field of analysis. A special space, which is mentioned by many authors.

“For the patient in an analytic session, there must be an empty space into which his fantasies flow as freely and unhindered as possible and in which the symbols of the unconscious can be found. Within this space, an alchemical transformation takes place and an aurum non vulgum arises from massa confuse (pure gold from a formless mass), which corresponds to the transformation of the libido through symbols” (Dieckmann, 2001).

Strong emotional reactions can be mobilized without fear of punishment or derogatory criticism from the analyst. The patient is given a "space" in which he can regress and express unacceptable unconscious desires and feelings. Precisely because the rules of the game in analysis are different from other types of interaction in society, the patient can experience himself in a new way” (Gabbard, Lester, 2014).

“In the process of analysis, there is a very deep collaborative experience of living the client's story. Sometimes the relationship between therapist and client is more intimate than between spouses, because in the analyst's office the client dares to reveal very intimate details that he could never tell anyone. 0005 James Hollis , speech, teleconference).

0005 James Hollis , speech, teleconference).

“The ability of the psychoanalyst to create the appropriate atmosphere is of great importance. Treatment through psychoanalysis is not simply a process of making the unconscious conscious… It is important that the analyst creates an appropriate background against which the psychoanalytic process can take place and reconnects with the split aspects of the self against which the patient's psyche tries to defend itself” (Sandler, 2007).

And, without a doubt, the creation of such a space is impossible without the personal analysis of the analyst. Only then will the analyst be able to build boundaries not just through knowledge of them, but through feeling, through deep understanding, sensation. The boundaries built through knowledge are artificial. They are just a facade that will not survive the first attempt to break them.

“Even the most comprehensive training program, limited to the transfer of absolutely necessary knowledge, despite the fact that this is undoubtedly necessary, cannot transfer to people that “something” that creates healing emanations within a person” (Von Franz, 2018).

“Andre Green emphasized that the ability to keep alive and secure internal and external boundaries is acquired by the future analyst on the couch, in the course of his own psychoanalysis” (Gabbard, Lester, 2014).

Conclusion

Borders don't just have to be there, they have to be strong. I love Skinner's metaphor, which compares borders to walls in a dark room. Knowing that they are calms and gives a feeling of reliability, security. But, in addition, they must be durable. They have to withstand if you want to hit them. Skinner uses this metaphor in the context of parenting (Skinner, 2016). He says that the child will definitely test the boundaries for strength. So is our client. With a high degree of probability, he will want to go to the wall and knock on it. And she must endure. And then our patient will understand that he is safe here.

In conclusion, I would like to quote V. Kalinenko : “To advance the psyche along the path of further differentiation, the psyche must have the possibility of a free unconscious identity, which means the ability to question existing boundaries and lose them” (Kalinenko, 2011).

References

- Wiener D. Therapeutic relationship: Transference, countertransference, and finding meaning. M.: Kogito-Tsentr, 2011. 145 p.

- Gabbard G., Lester E. Psychoanalytic boundaries and their violations. M.: Klass, 2014. 272 p.

- Green A. The Analyst, Symbolization and Absence in the Analytic Setting (On Changes in Analytic Practice and Analytic Experience) - in memory of D. W. Winnicott. URL: https://www.maap.pro/biblioteka/stati/grin_simvolizaciya_i_otsutstvie_v_analiticheskom_opyte.html (accessed 14.01.2022).

- Dickmann H. Methods in analytical psychology. M .: LLC "TsGL" RON ", V. Sekachev, 2001. 329With.

- Kalinenko V.K. Frontiers in Analysis: The Jungian Approach. M.: Kogito-Tsentr, 2011. 233 p.

- Kast W., Proner B. Discussion around transference and countertransference. URL: https://www.maap.pro/biblioteka/stati/kast_proner_perenos_i_kontrperenos.html (accessed 14.01.2022).

- Casement P.

Learning from the patient. Voronezh: NPO "MODEK", 1995. 256 p.

Learning from the patient. Voronezh: NPO "MODEK", 1995. 256 p. - Kernberg O. Severe personality disorders. Psychotherapy strategies. M.: Klass, 2014. 646 p.

- Kryuchkova S.A. Boundaries of personality in relationships and communication. Barnaul: New format, 2020. 180 p.

- Langs R. Working book of a psychotherapist. Unconscious aspects of communication and their understanding. M.: Eksmo, 2003. 192 p.

- Perry K. Transference, countertransference. URL: https://www.maap.pro/biblioteka/stati/perri_perenos_kontrperenos.html (Date of access: 01/14/2022).

- Sandler D. Patient and psychoanalyst. Fundamentals of the psychoanalytic process. M.: Kogito-Centre, 2007. 254 p.

- Skinner R. Family and how to survive in it. M.: Klass, 2016. 328 p.

- Von Franz M. L. Psychotherapy. Club "Kastalia", 2018. 250 p.

- Fonda P. Containerization according to Bion and Holding according to Winnicott. URL: https://psychoanalysis.

by/2018/02/23/holding/ (date of access: 01/14/2022).

by/2018/02/23/holding/ (date of access: 01/14/2022). - Jung KG Psychology of transference: articles. M.: Refl-book, 1997. 298 p.

- Jacobi M. Meeting with an analyst. The phenomenon of transference and real relationships. M.: Kogito-Centre, 2007. 144 p.

Personal boundaries in psychotherapy

In the 1920s there was a psychoanalyst, a student of Freud, whose name was Sandor Ferenczi. He believed that the psychotherapist's sex with patients improves the results of the psychotherapeutic process. There were other scientists who believed that it was possible to violate the boundaries of psychotherapy for the best result, but in reality, it turned out that all this was nonsense. Violation of personal boundaries between therapist and patient does not increase the chances of a positive result, but fundamentally kill everything that has been achieved in the process of psychotherapy.

How are boundaries built between therapist and patient?

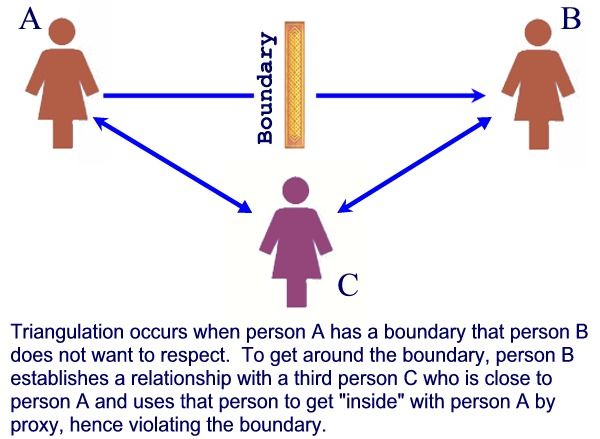

Psychotherapy always begins with building boundaries. Normally, the specialist himself must announce the boundaries of therapy, starting with how much it costs, how long the session lasts, and how long the whole process is supposed to last. The most striking example of building boundaries is when the therapist explains exactly how the therapy will take place and what will happen in the sessions. Imagine that parents come to a psychotherapist to solve their child's problems. During the sessions, the problems that exist in the couple come up, and the parents try to involve the psychotherapist in sorting out the relationship with each other. The task of an experienced therapist is to remind patients of the boundaries of psychotherapy or build them anew. For example, to say that the sessions should be about talking about the child, not solving the problems of the parents.

Normally, the specialist himself must announce the boundaries of therapy, starting with how much it costs, how long the session lasts, and how long the whole process is supposed to last. The most striking example of building boundaries is when the therapist explains exactly how the therapy will take place and what will happen in the sessions. Imagine that parents come to a psychotherapist to solve their child's problems. During the sessions, the problems that exist in the couple come up, and the parents try to involve the psychotherapist in sorting out the relationship with each other. The task of an experienced therapist is to remind patients of the boundaries of psychotherapy or build them anew. For example, to say that the sessions should be about talking about the child, not solving the problems of the parents.

The patient is always testing the therapist's boundaries, and it is normal that he tries to violate them.

Naturally, patients can pull the therapist out of these boundaries. They may begin to talk about how problems in interpersonal communication are directly related to the problems of the child. It is important for the therapist to remain adamant and say that if parents want to solve their problems, for example, sexual ones, then they can turn to a therapist who specializes in this particular area of work.

They may begin to talk about how problems in interpersonal communication are directly related to the problems of the child. It is important for the therapist to remain adamant and say that if parents want to solve their problems, for example, sexual ones, then they can turn to a therapist who specializes in this particular area of work.

See also

Myths about psychotherapy

The patient is always testing the therapist's boundaries, and it is normal that he tries to violate them. The task of the psychotherapist is to keep these boundaries. But there are rather harmless things that can be present in the framework of psychotherapy in a limited amount. For example, at the beginning or in the middle of the session, it is perfectly normal to have a very short talk on an abstract topic - discuss the weather or the dollar exchange rate. This can be a great respite between the mentally difficult parts of the session. However, you should not get carried away with such conversations and talk about abstract things throughout the session.

However, you should not get carried away with such conversations and talk about abstract things throughout the session.

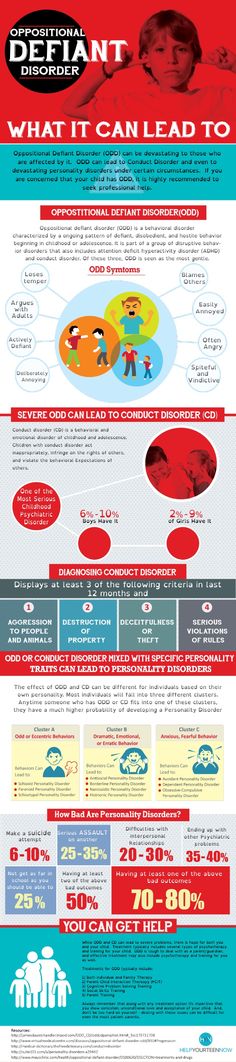

Patients with what disorders are most likely to violate personal boundaries during psychotherapy?

Patients with psychopathy and personality disorders mostly break boundaries. For example, it is not uncommon for patients with borderline personality disorder to come to therapy without underwear. So they try to seduce the therapist, because they know how to communicate and build long-term relationships with people using only their body. The task of an experienced psychotherapist is to interrupt such behavior. For example, telling such a patient that they need to meet the next time she is fully dressed, and she will have to pay for this meeting.

Even in a closed ward of a psychiatric hospital, psychotherapists try not to touch patients unnecessarily once again.

Personal boundaries with a psychotherapist are violated by those who in ordinary life are accustomed to violate the boundaries of other people. To behave like this, it is not at all necessary to suffer from some kind of mental disorder.

To behave like this, it is not at all necessary to suffer from some kind of mental disorder.

Can a psychotherapist touch a patient?

Psychotherapy that takes place in a private office or clinic does not imply that the patient may be in such a serious condition that he needs to be influenced by physical contact. Even in a closed ward of a psychiatric hospital, psychotherapists try not to touch patients unnecessarily once again.

It is much easier with children in this respect. For example, it is perfectly normal to take a small patient by the hand to correct his behavior. For example, if a child is undergoing treatment for Tourette's syndrome, a psychotherapist can stop his movements with his hand during sessions, restrain him. The child understands in advance that the therapist will touch him.

See also

Mental norm and pathology

How to rebuild the boundaries of psychotherapy if they have been violated?

It happens that the therapist does not immediately realize his mistake in violating personal boundaries with the patient. For example, a psychotherapist gives a patient his personal phone number for special occasions, and the patient begins to call him at night and ask him to consult on some issue. After that, an experienced psychotherapist catches on and realizes that he made a mistake. He can delicately convey to the patient that he should not have given him his phone and ask the patient not to call him again. After that, the patient may lose confidence in the therapist, so it is very important to show the patient the boundaries of therapy: “just because I stop answering you at 2 am does not mean that I will stop helping and caring for you.” In therapeutic practice, such cases are not uncommon, and it is very important for a specialist to notice his mistakes in time and return the patient to the rails of psychotherapy.

For example, a psychotherapist gives a patient his personal phone number for special occasions, and the patient begins to call him at night and ask him to consult on some issue. After that, an experienced psychotherapist catches on and realizes that he made a mistake. He can delicately convey to the patient that he should not have given him his phone and ask the patient not to call him again. After that, the patient may lose confidence in the therapist, so it is very important to show the patient the boundaries of therapy: “just because I stop answering you at 2 am does not mean that I will stop helping and caring for you.” In therapeutic practice, such cases are not uncommon, and it is very important for a specialist to notice his mistakes in time and return the patient to the rails of psychotherapy.

How might a psychotherapist's personal problems affect his patients?

An experienced psychotherapist knows how to leave his personal problems outside the door of the therapy room.