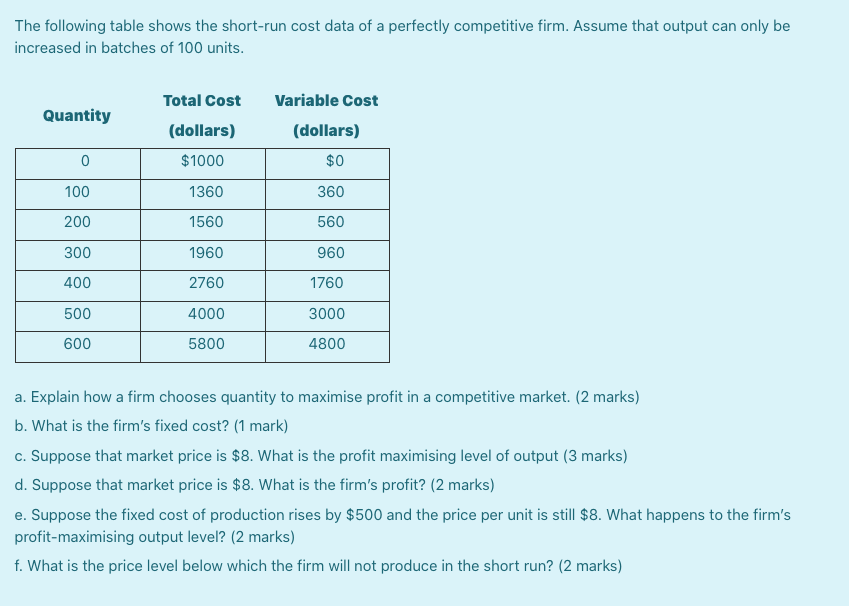

Bipolar disorder age onset

Bipolar disorder | NAMI: National Alliance on Mental Illness

In this 2-part podcast series, NAMI Chief Medical Officer Dr. Ken Duckworth guides discussions on bipolar disorder that offer insights from individuals, family members and mental health professionals. Read the transcript.

Note: Content includes discussions on topics such as suicide attempts and may be triggering.

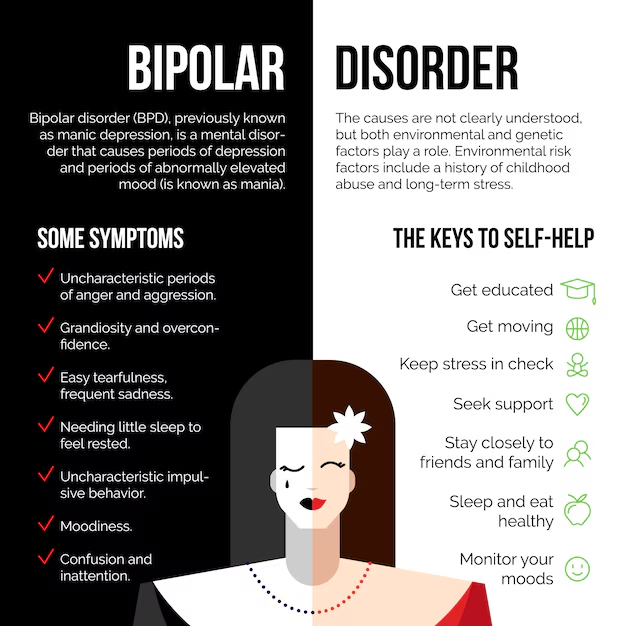

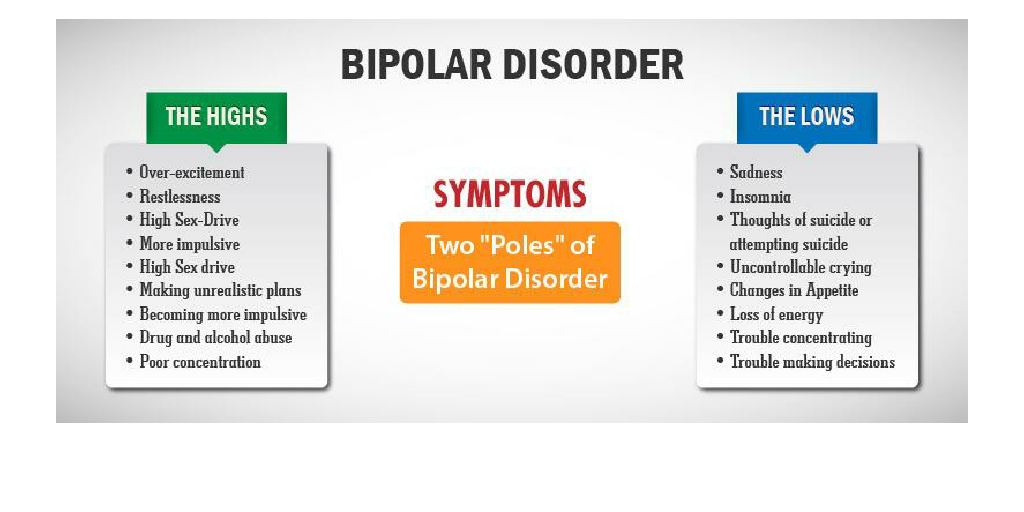

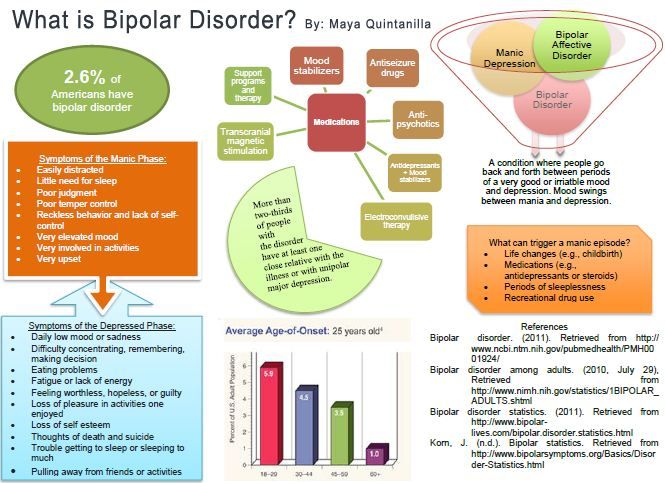

Bipolar disorder is a mental illness that causes dramatic shifts in a person’s mood, energy and ability to think clearly. People with bipolar experience high and low moods—known as mania and depression—which differ from the typical ups-and-downs most people experience.

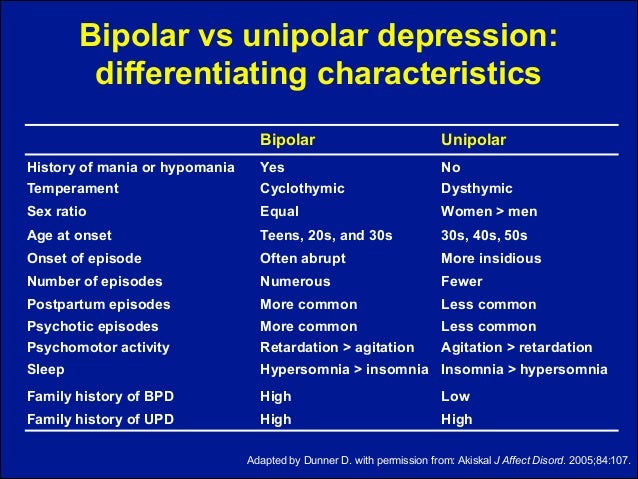

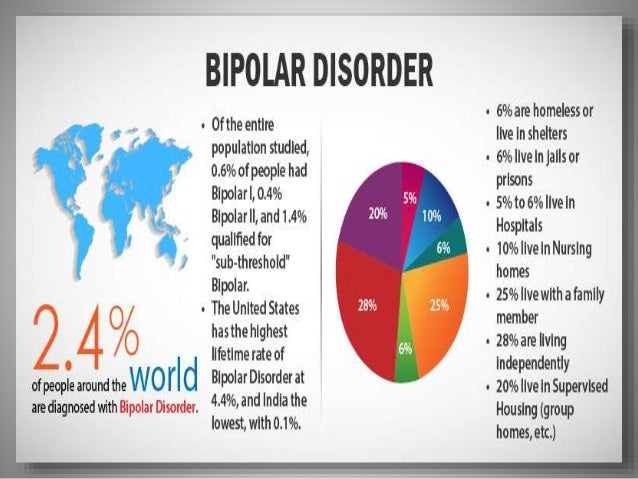

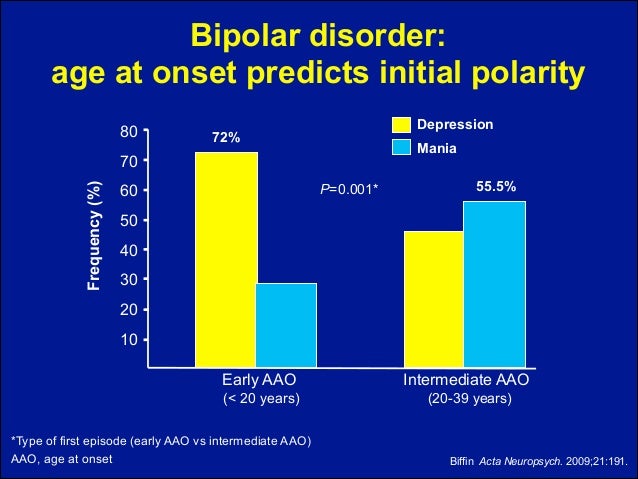

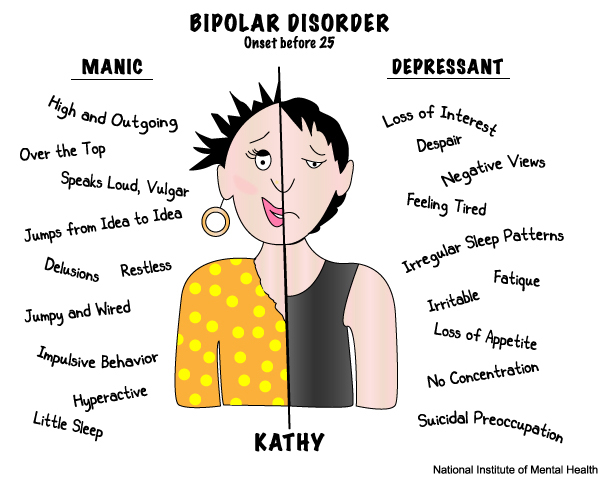

The average age-of-onset is about 25, but it can occur in the teens, or more uncommonly, in childhood. The condition affects men and women equally, with about 2. 8% of the U.S. population diagnosed with bipolar disorder and nearly 83% of cases classified as severe.

If left untreated, bipolar disorder usually worsens. However, with a good treatment plan including psychotherapy, medications, a healthy lifestyle, a regular schedule and early identification of symptoms, many people live well with the condition.

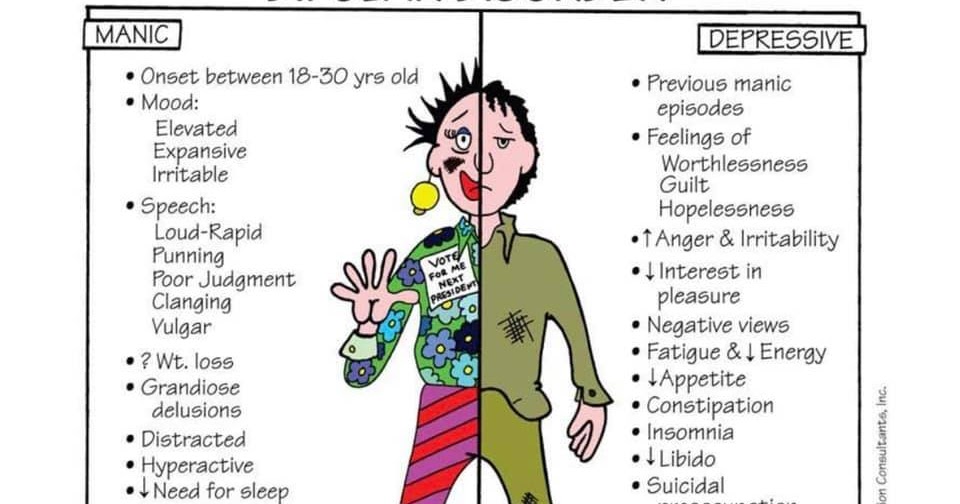

Symptoms

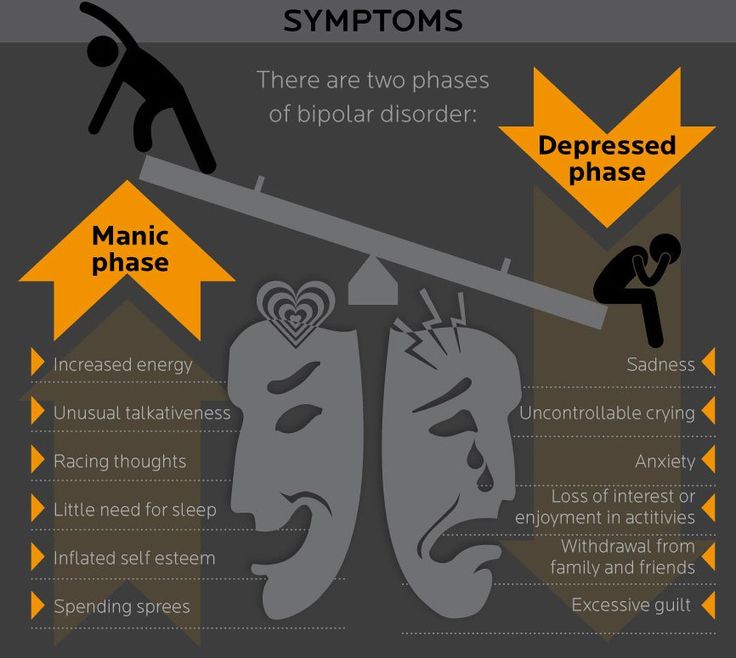

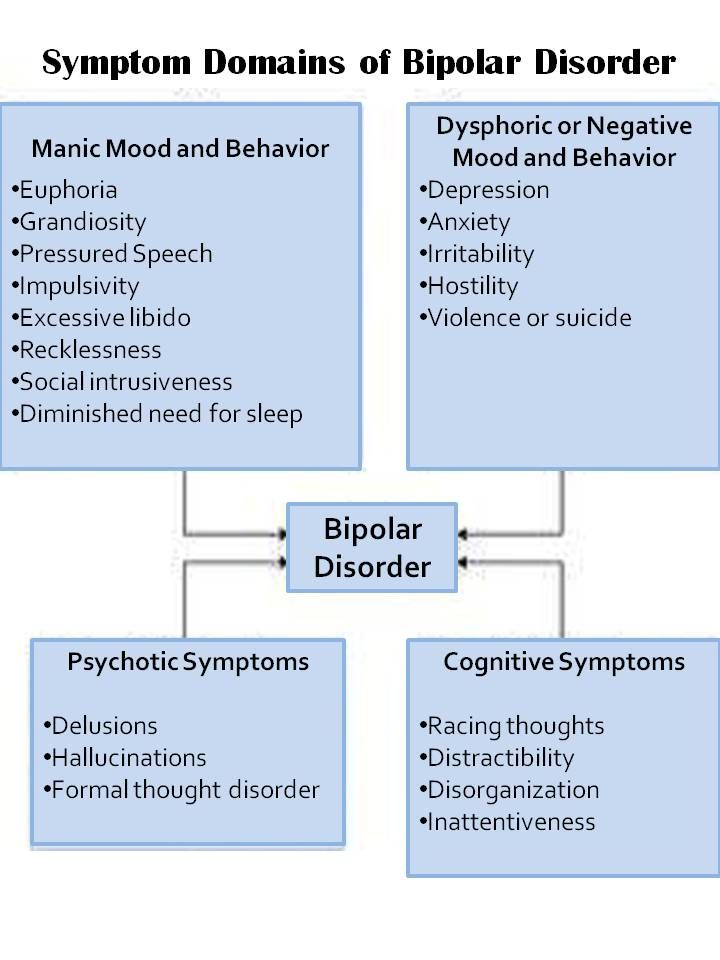

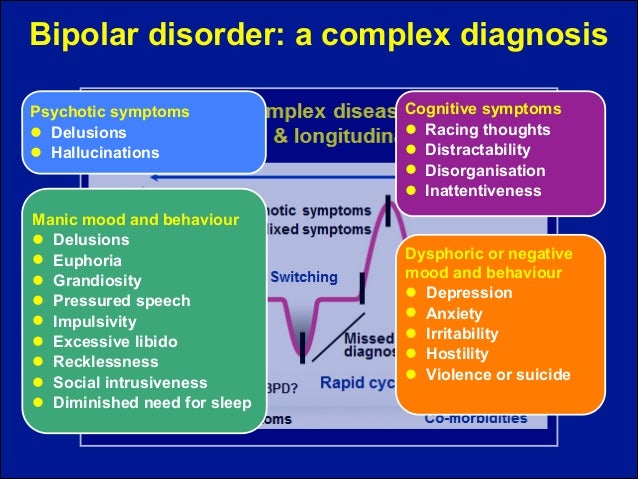

Symptoms and their severity can vary. A person with bipolar disorder may have distinct manic or depressed states but may also have extended periods—sometimes years—without symptoms. A person can also experience both extremes simultaneously or in rapid sequence.

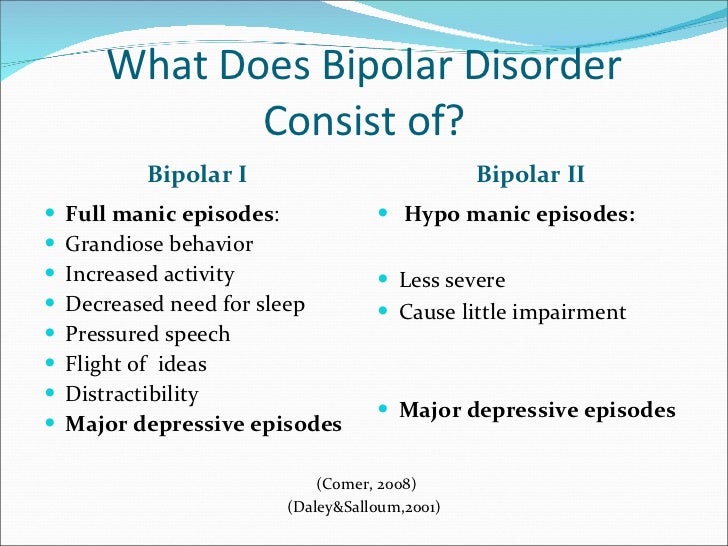

Severe bipolar episodes of mania or depression may include psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations or delusions. Usually, these psychotic symptoms mirror a person’s extreme mood. People with bipolar disorder who have psychotic symptoms can be wrongly diagnosed as having schizophrenia.

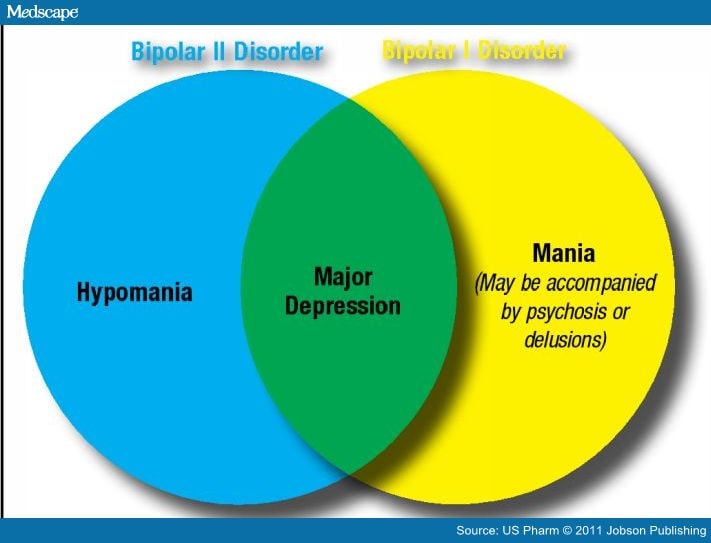

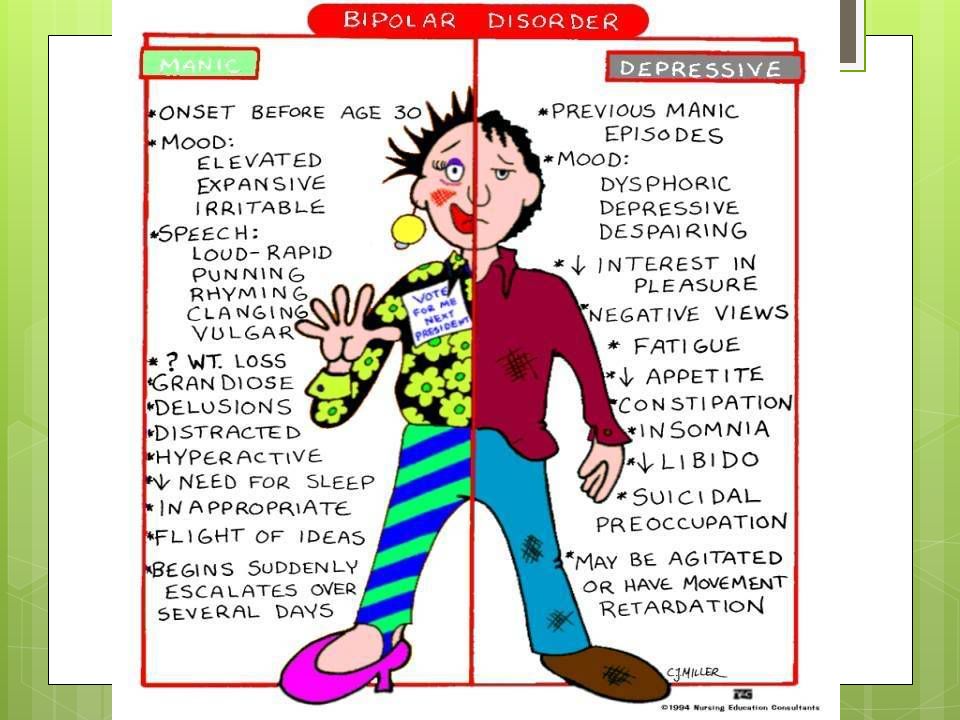

Mania. To be diagnosed with bipolar disorder, a person must have experienced at least one episode of mania or hypomania. Hypomania is a milder form of mania that doesn’t include psychotic episodes. People with hypomania can often function well in social situations or at work. Some people with bipolar disorder will have episodes of mania or hypomania many times throughout their life; others may experience them only rarely.

Hypomania is a milder form of mania that doesn’t include psychotic episodes. People with hypomania can often function well in social situations or at work. Some people with bipolar disorder will have episodes of mania or hypomania many times throughout their life; others may experience them only rarely.

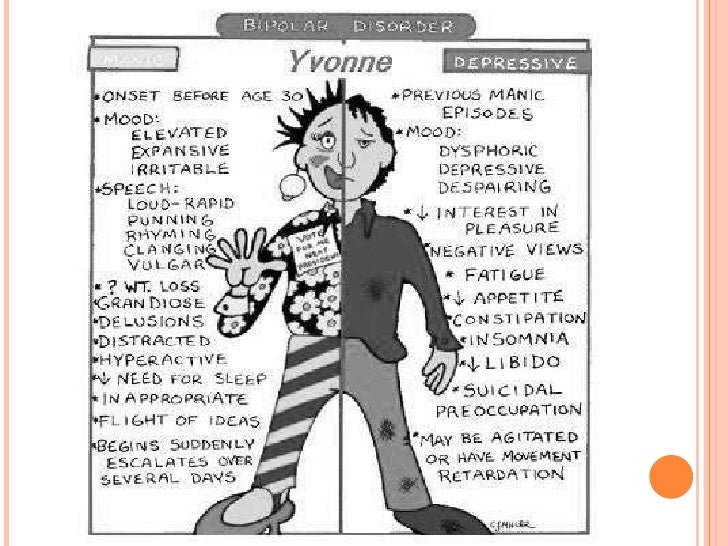

Although someone with bipolar may find an elevated mood of mania appealing—especially if it occurs after depression—the “high” does not stop at a comfortable or controllable level. Moods can rapidly become more irritable, behavior more unpredictable and judgment more impaired. During periods of mania, people frequently behave impulsively, make reckless decisions and take unusual risks.

Most of the time, people in manic states are unaware of the negative consequences of their actions. With bipolar disorder, suicide is an ever-present danger because some people become suicidal even in manic states. Learning from prior episodes what kinds of behavior signals “red flags” of manic behavior can help manage the symptoms of the illness.

Depression. The lows of bipolar depression are often so debilitating that people may be unable to get out of bed. Typically, people experiencing a depressive episode have difficulty falling and staying asleep, while others sleep far more than usual. When people are depressed, even minor decisions such as what to eat for dinner can be overwhelming. They may become obsessed with feelings of loss, personal failure, guilt or helplessness; this negative thinking can lead to thoughts of suicide.

The depressive symptoms that obstruct a person’s ability to function must be present nearly every day for a period of at least two weeks for a diagnosis. Depression associated with bipolar disorder may be more difficult to treat and require a customized treatment plan.

Causes

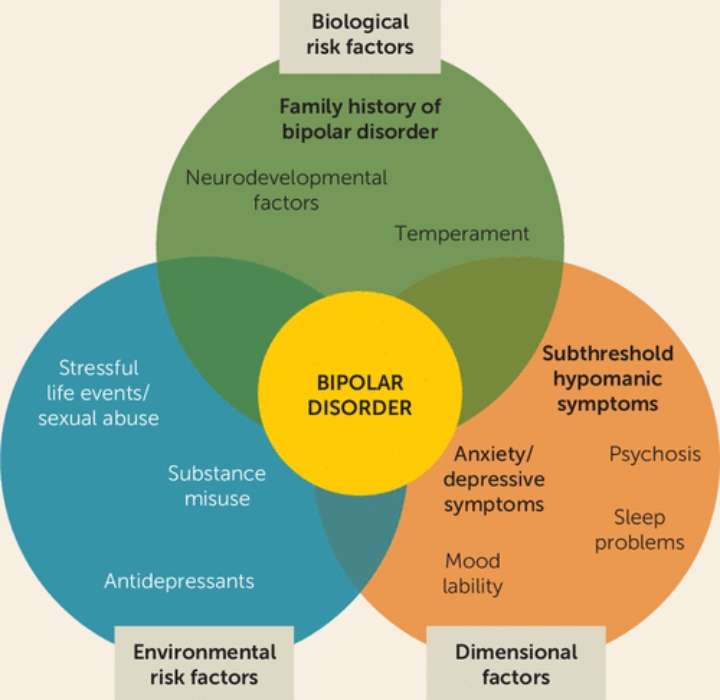

Scientists have not yet discovered a single cause of bipolar disorder. Currently, they believe several factors may contribute, including:

- Genetics. The chances of developing bipolar disorder are increased if a child’s parents or siblings have the disorder.

But the role of genetics is not absolute: A child from a family with a history of bipolar disorder may never develop the disorder. Studies of identical twins have found that, even if one twin develops the disorder, the other may not.

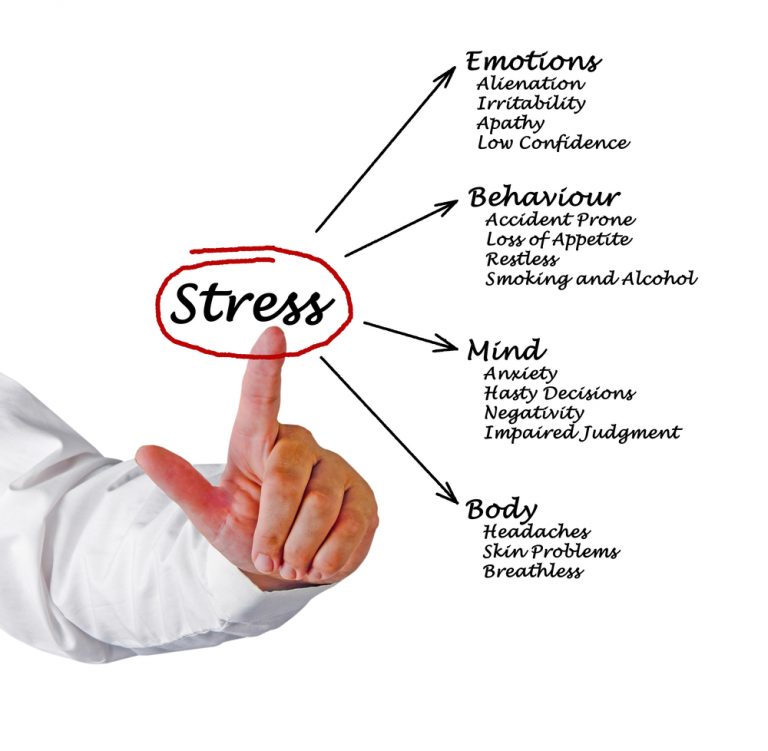

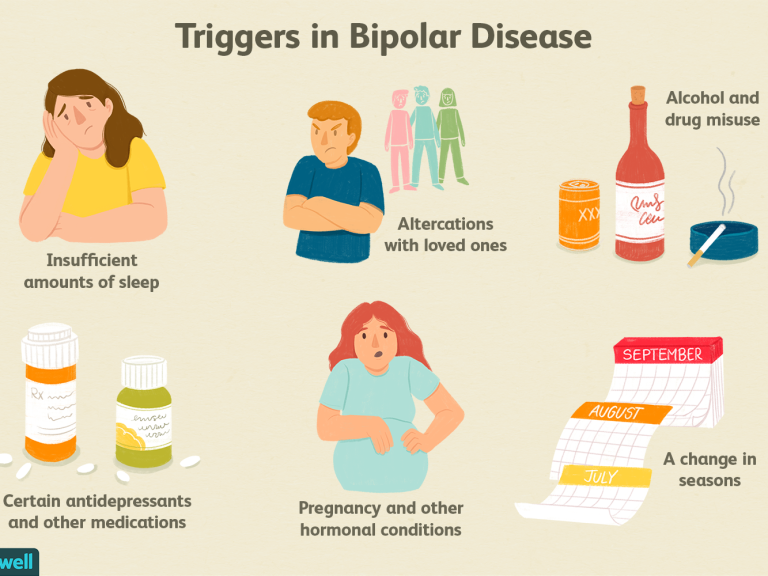

But the role of genetics is not absolute: A child from a family with a history of bipolar disorder may never develop the disorder. Studies of identical twins have found that, even if one twin develops the disorder, the other may not. - Stress. A stressful event such as a death in the family, an illness, a difficult relationship, divorce or financial problems can trigger a manic or depressive episode. Thus, a person’s handling of stress may also play a role in the development of the illness.

- Brain structure and function. Brain scans cannot diagnose bipolar disorder, yet researchers have identified subtle differences in the average size or activation of some brain structures in people with bipolar disorder.

Diagnosis

To diagnose bipolar disorder, a doctor may perform a physical examination, conduct an interview and order lab tests. While bipolar disorder cannot be seen on a blood test or body scan, these tests can help rule out other illnesses that can resemble the disorder, such as hyperthyroidism. If no other illnesses (or medicines such as steroids) are causing the symptoms, the doctor may recommend mental health care.

If no other illnesses (or medicines such as steroids) are causing the symptoms, the doctor may recommend mental health care.

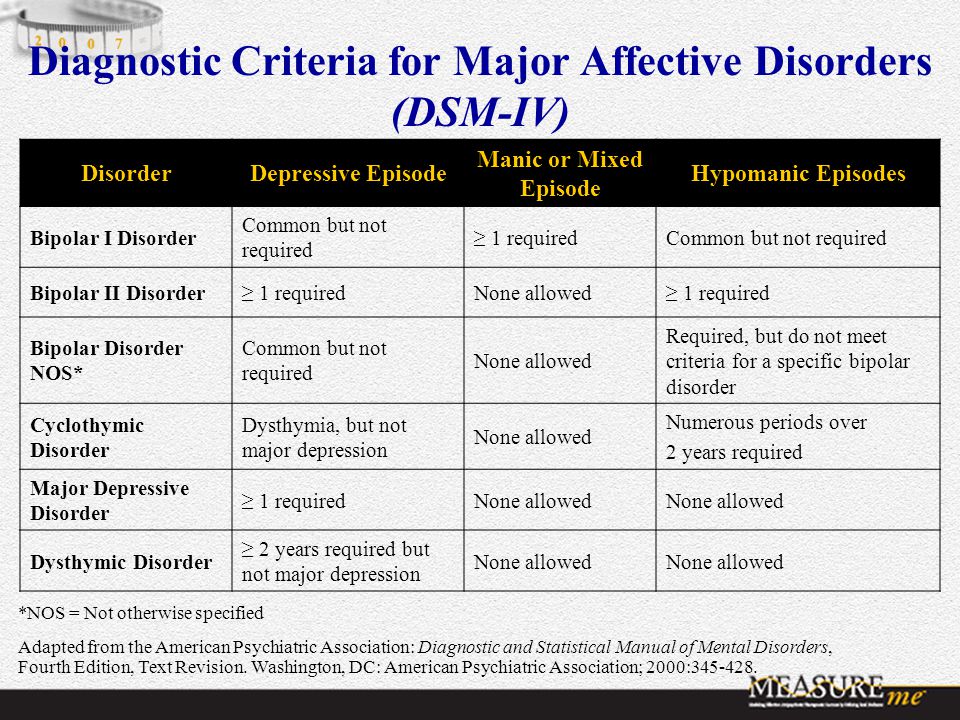

To be diagnosed with bipolar disorder, a person must have experienced at least one episode of mania or hypomania. Mental health care professionals use the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) to diagnose the “type” of bipolar disorder a person may be experiencing. To determine what type of bipolar disorder a person has, mental health care professionals assess the pattern of symptoms and how impaired the person is during their most severe episodes.

Four Types of Bipolar Disorder

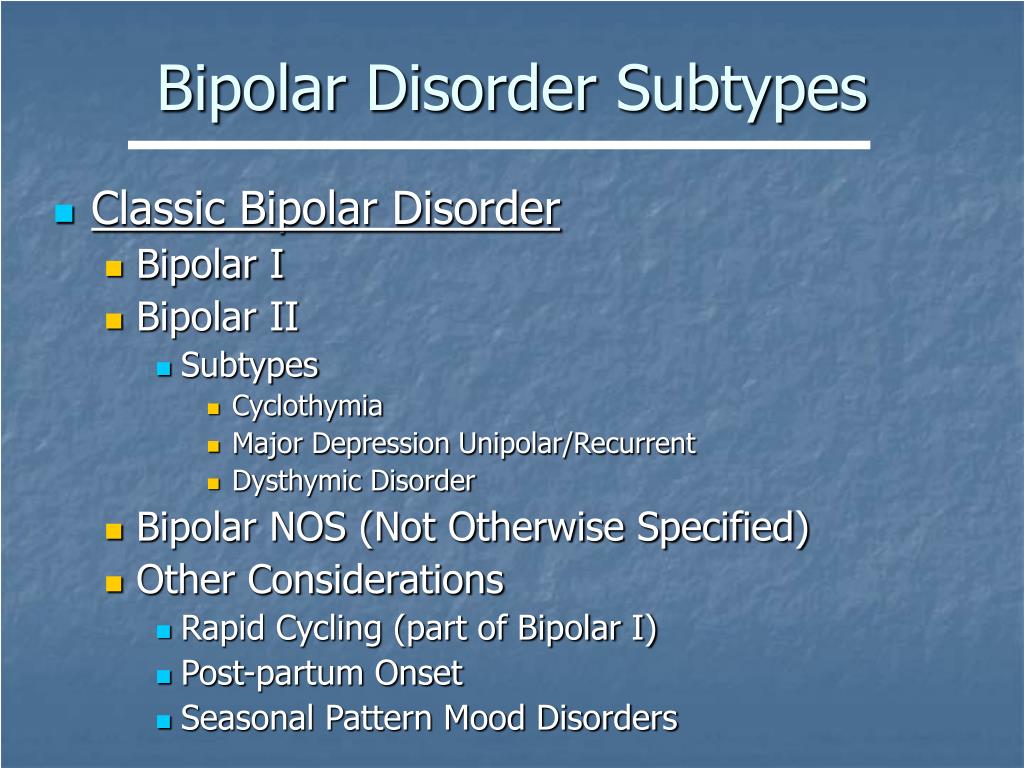

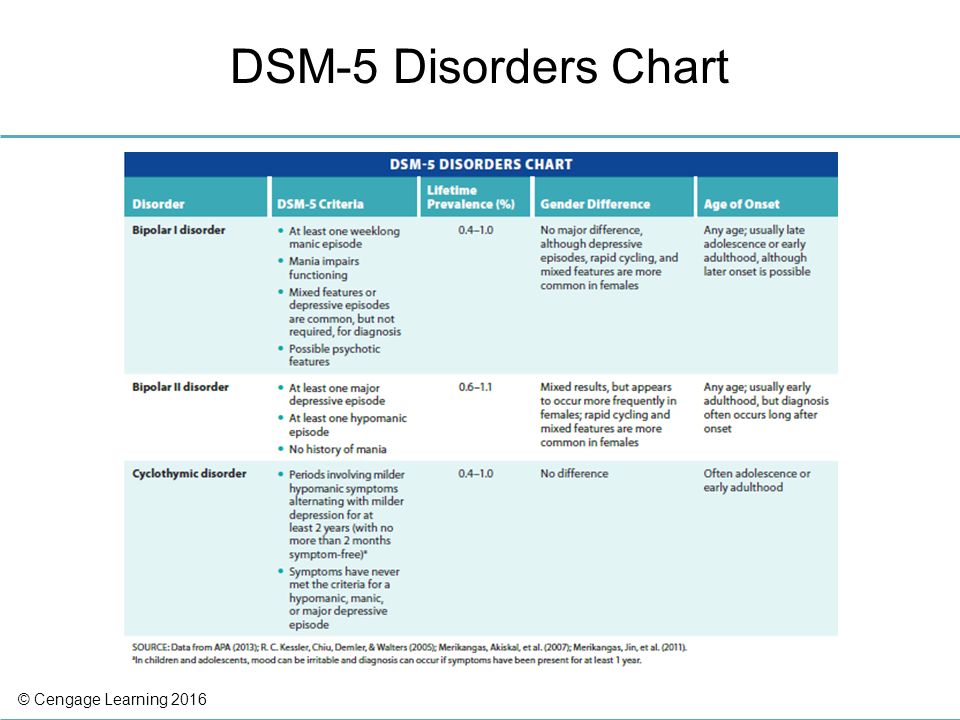

- Bipolar I Disorder is an illness in which people have experienced one or more episodes of mania. Most people diagnosed with bipolar I will have episodes of both mania and depression, though an episode of depression is not necessary for a diagnosis. To be diagnosed with bipolar I, a person’s manic episodes must last at least seven days or be so severe that hospitalization is required.

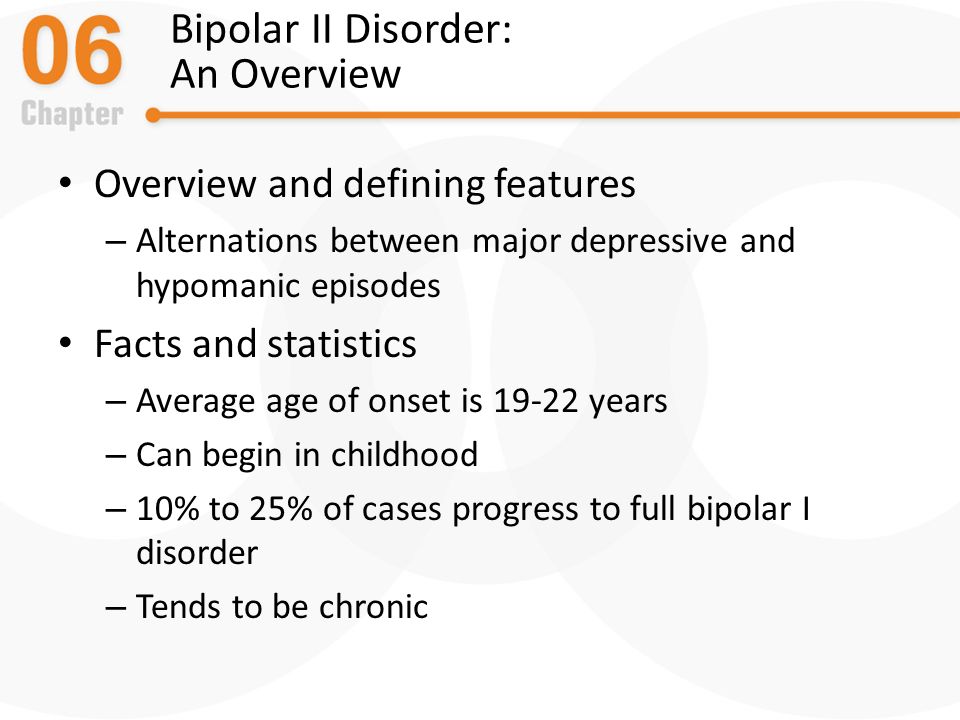

- Bipolar II Disorder is a subset of bipolar disorder in which people experience depressive episodes shifting back and forth with hypomanic episodes, but never a “full” manic episode.

- Cyclothymic Disorder or Cyclothymia is a chronically unstable mood state in which people experience hypomania and mild depression for at least two years. People with cyclothymia may have brief periods of normal mood, but these periods last less than eight weeks.

- Bipolar Disorder, “other specified” and “unspecified” is when a person does not meet the criteria for bipolar I, II or cyclothymia but has still experienced periods of clinically significant abnormal mood elevation.

Treatment

Bipolar disorder is treated and managed in several ways:

- Psychotherapy, such as cognitive behavioral therapy and family-focused therapy.

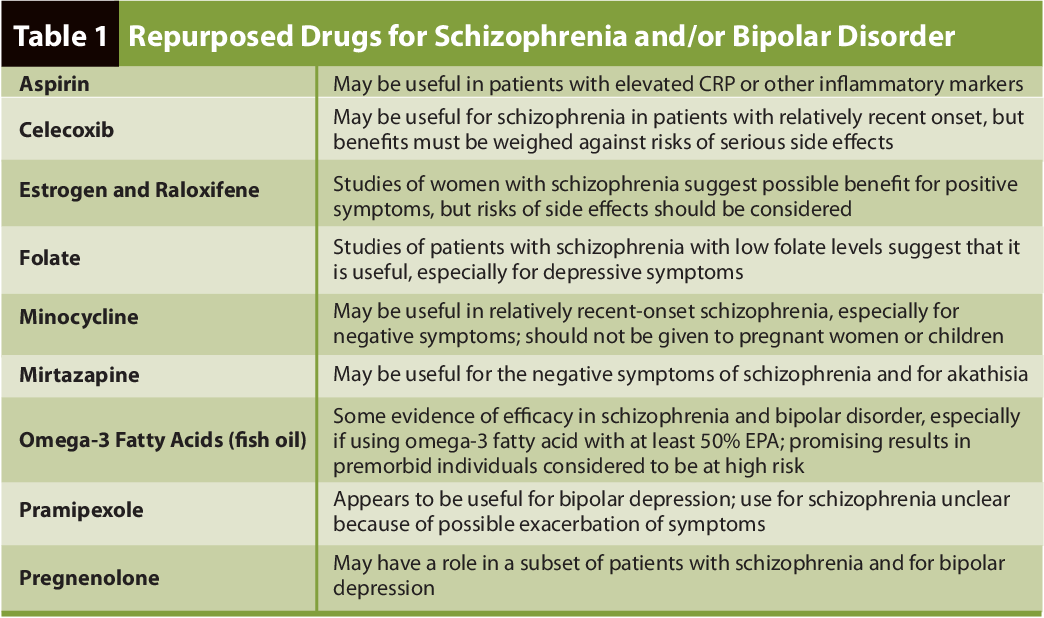

- Medications, such as mood stabilizers, antipsychotic medications and, to a lesser extent, antidepressants.

- Self-management strategies, like education and recognition of an episode’s early symptoms.

- Complementary health approaches, such as aerobic exercise meditation, faith and prayer can support, but not replace, treatment.

The largest research project to assess what treatment methods work for people with bipolar disorder is the Systematic Treatment Enhancement for Bipolar Disorder, otherwise known as Step-BD. Step-BD followed over 4,000 people diagnosed with bipolar disorder over time with different treatments.

Related Conditions

People with bipolar disorder can also experience:

- Anxiety

- Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- Substance use disorders/dual diagnosis

People with bipolar disorder and psychotic symptoms can be wrongly diagnosed with schizophrenia. Bipolar disorder can be also misdiagnosed as Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD).

These other illnesses and misdiagnoses can make it hard to treat bipolar disorder. For example, the antidepressants used to treat OCD and the stimulants used to treat ADHD may worsen symptoms of bipolar disorder and may even trigger a manic episode. If you have more than one condition (called co-occurring disorders), be sure to get a treatment plan that works for you.

Reviewed August 2017

Why It Matters I Psych Central

We include products we think are useful for our readers. If you buy through links on this page, we may earn a small commission. Here’s our process.

Psych Central only shows you brands and products that we stand behind.

Our team thoroughly researches and evaluates the recommendations we make on our site. To establish that the product manufacturers addressed safety and efficacy standards, we:

- Evaluate ingredients and composition: Do they have the potential to cause harm?

- Fact-check all health claims: Do they align with the current body of scientific evidence?

- Assess the brand: Does it operate with integrity and adhere to industry best practices?

We do the research so you can find trusted products for your health and wellness.

Bipolar age of onset can vary. If you or someone you know is experiencing signs of this condition later in life, the reason might be late onset bipolar.

The word bipolar means two poles, or extremes. It’s a fitting name for this condition that features drastic shifts in mood and energy.

People living with bipolar disorder experience episodes of mania and depression. During a manic episode, you might be awake all night brimming with energy and ideas, and function on little sleep for several days. This may sound like an advantage.

However, mania transitions into a depression that can leave you feeling empty, pessimistic, and sad. You may not have the energy to get out of bed, let alone make it through the day.

Although bipolar often appears in adolescence and early 20s, some people experience their first symptoms later in life.

The average age of bipolar onset is around 25 years old, although it can vary.

Sometimes bipolar symptoms start in childhood or later in life. However, the most frequent range of onset is between the ages of 14 to 21 years.

However, the most frequent range of onset is between the ages of 14 to 21 years.

Childhood bipolar is relatively rare, with only up to 3% of children receiving this diagnosis.

According to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), about 4.4% of adults (18 years of age or older) in the United States will experience bipolar disorder at some point in their lives. It affects men and women equally.

NIMH estimates that nearly 2.9% of adolescents — those who are between 13 and 18 years old — will experience bipolar disorder at some point, with the highest prevalence (up to 4.3%) seen in 17- to 18-year-olds.

Despite common belief, bipolar disorder doesn’t just occur in young people. In recent years, research has shown an increase in the diagnosis of late onset bipolar disorder (LOBD).

According to a 2015 report from the International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force on Older-Age Bipolar Disorder (OABD), up to 25% of people with bipolar disorder are 60 years of age and older. It’s estimated that between 5% and 10% of people start showing symptoms of bipolar disorder after the age of 50 years old.

It’s estimated that between 5% and 10% of people start showing symptoms of bipolar disorder after the age of 50 years old.

People diagnosed with LOBD differ from those with early onset BD in several ways.

- They have more association with neurological disorders like cerebrovascular disease — such as stroke or aneurysms.

- They have fewer occurrences of mood disorders in their family history.

- They have more comorbid medical conditions but fewer comorbid psychiatric diagnoses.

- They may experience depressive episodes more often than mania or hypomania. These episodes can also be more frequent and severe than those seen in younger people with bipolar disorder.

In addition, people with LOBD have vascular changes in their right brain hemispheres that have been linked to manic episodes, and vascular lesions in their left cerebral hemispheres that have been associated with depressive episodes. However, more research is needed to support these claims.

Research suggests several factors that can contribute to the development of bipolar disorder.

- Genetics: Family history is more often linked to early onset bipolar than LOBD. Having a parent or sibling with bipolar disorder may increase your chances of developing the condition, but it’s no guarantee. Some people with family history never develop bipolar.

- Stress: An event or ongoing situation can trigger manic and depressive episodes. Examples include a death in the family, financial hardship, or a difficult relationship.

- Brain structure: People with bipolar disorder may have structural differences in their brains. LOBD features vascular differences in both the left and right hemispheres of the brain.

Medical conditions can sometimes cause late-onset bipolar symptoms. Examples include:

- vascular dementia

- encephalitis

- neurosyphilis

- stroke

- HIV encephalopathy

- multiple sclerosis

- traumatic brain injury (TBI)

- Huntington’s disease

- brain tumors

- lupus

- hyperthyroidism

- vitamin B12 deficiency

Late-onset bipolar disorder is a diagnosis of exclusion, meaning that a healthcare professional will rule out other conditions that may be causing your symptoms, like cerebrovascular disease.

They will likely begin with a thorough medical and family history and conduct medical assessments like lab and imaging tests.

Symptoms that may be assessed when diagnosing LOBD can include:

- mania, with fewer and milder episodes than in early onset bipolar disorder

- depressive episodes

- irritability

- psychomotor changes (rapid or slowed speech, physical agitation)

- mental flexibility impairments

- cognitive impairments, more pronounced than in early onset bipolar disorder

Once potential medical causes for symptoms have been ruled out, you may be referred to a mental health professional for further evaluation and testing.

It helps to get an early diagnosis so that you can start treatment sooner. According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), delaying treatment can allow bipolar disorder to progress and worsen.

Much like in the case of early onset bipolar disorder, medications may be prescribed to help treat your symptoms.

These medications include:

- lithium

- lamotrigine (Lamictal)

- quetiapine (Seroquel)

- lurasidone (Latuda)

- valproate (Depakote)

- aripiprazole (Abilify)

Some evidence suggests that people who take lithium for bipolar disorder later in life might experience lower rates of dementia or Alzheimer’s disease. More research is needed to determine if lithium can treat the cognitive decline from bipolar disorder.

There are lithium side effects to consider, which could include:

- tremors

- cognitive impairment

- renal dysfunction

- rash

- weight gain

- hypothyroidism

Potential medication interactions and other side effects might also be considered. People with LOBD are more likely than younger people with bipolar disorder to be taking medications for other conditions. Also, some antipsychotic medications can cause serious side effects in people living with dementia.

Those who don’t respond to medication can try electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), which sometimes works for LOBD. Transcranial magnetic stimulation is another neurostimulation technique that may be beneficial, although more research is needed for this age group.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation is another neurostimulation technique that may be beneficial, although more research is needed for this age group.

Psychotherapy can help younger people with bipolar disorder, but more research is needed to determine if treatments like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and interpersonal therapy (IPT) can help treat LOBD.

Bipolar is a serious condition, but it’s treatable.

An accurate diagnosis and prompt treatment can help reduce manic and depressive episodes. This helps manage your symptoms and reduces the chance that your symptoms get worse.

Sometimes treatable medical conditions can cause bipolar symptoms when you’re older. A complete medical history can help a healthcare professional identify such conditions. They can also help you minimize the chance of interactions between bipolar medications and other medications you may be taking.

It may feel overwhelming to be diagnosed with bipolar disorder when you’re older, but there is support available. Here are some resources you can try:

Here are some resources you can try:

- American Psychological Association psychologist locator

- National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline

- Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance online support groups

- 7 Cups Emotional Support System

- Daily Strength bipolar disorder support group

- My Support Forums mental health support groups

14 Early Symptoms of Bipolar Disorder You Shouldn't Ignore

October 19, 2020 Likbez Health

Psychosis is closer than it seems. Check it out.

This disorder was brought to the fore several years ago when Catherine Zeta-Jones was diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

Catherine Zeta-Jones

actress

Millions of people suffer from this, and I'm just one of them. I say this out loud so that people know that there is no shame in seeking professional help in such a situation.

Largely due to the courage of the black-haired Hollywood diva, other celebrities began to admit that they were experiencing this psychosis: Mariah Carey, Mel Gibson, Ted Turner . .. Doctors suggest bipolar disorder and already deceased famous people: Kurt Cobain, Jimi Hendrix, Ernest Hemingway, Vivien Leigh, Marilyn Monroe…

.. Doctors suggest bipolar disorder and already deceased famous people: Kurt Cobain, Jimi Hendrix, Ernest Hemingway, Vivien Leigh, Marilyn Monroe…

The enumeration of familiar names is only necessary to show that psychosis is very close to you. And maybe even you.

What is bipolar disorder

At first glance, it's okay. Just mood swings. For example, in the morning you want to sing and dance for the joy that you live. In the middle of the day, you suddenly snap at colleagues who distract you from something important. By evening, a severe depression rolls over you, when you can’t even raise your hand ... Familiar?

The line between mood swings and manic-depressive psychosis (this is the second name of this disease) is thin. But she is.

The attitude of those who suffer from bipolar disorder constantly jumps between the two poles. From an extreme maximum (“What a thrill it is to just live and do something!”) to an equally extreme minimum (“Everything is bad, we will all die. So, maybe there is nothing to wait, it's time to lay hands on yourself ?!”). The highs are called periods of mania. The lows are periods of depression.

So, maybe there is nothing to wait, it's time to lay hands on yourself ?!”). The highs are called periods of mania. The lows are periods of depression.

A person realizes how stormy he is and how often these storms have no reason, but he cannot do anything with himself.

Manic-depressive psychosis exhausts, worsens relationships with others, sharply reduces the quality of life and, as a result, can lead to suicide.

Where does bipolar disorder come from

Mood swings are familiar to many and are not considered something out of the ordinary. Therefore, bipolar disorder is quite difficult to diagnose. However, scientists are getting better at it. In 2005, for example, about 5 million Americans were estimated to suffer from some form of manic-depressive psychosis.

Bipolar disorder is more common in women than in men. Why is not known.

However, despite the large statistical sample, the exact causes of bipolar disorders have not yet been clarified. We only know that:

- Manic-depressive psychosis can occur at any age. Although it appears most often in late adolescence and early adulthood.

- It can be caused by genetics. If one of your ancestors had this disease, there is a risk that it will knock on your door too.

- The disorder is associated with an imbalance of chemicals in the brain. Mainly serotonin.

- The trigger is sometimes severe stress or trauma.

How to Recognize the Early Symptoms of Bipolar Disorder

In order to capture unhealthy mood swings, you first need to find out if you are experiencing emotional extremes - mania and depression.

7 Key Signs of Mania

- You experience high spirits and a feeling of happiness for long (several hours or more) periods.

- You have a reduced need for sleep.

- You speak fast. And so much so that those around you do not always understand, and you do not have time to formulate your thoughts.

As a result, it is easier for you to communicate in instant messengers or through emails than to talk to people live.

As a result, it is easier for you to communicate in instant messengers or through emails than to talk to people live. - You are an impulsive person: first you act, then you think.

- You are easily distracted and jump from one thing to another. As a result, productivity often suffers.

- You are confident in your abilities. It seems to you that you are faster and smarter than most of those around you.

- You often exhibit risky behavior. For example, agreeing to have sex with a stranger, buying something that you can't afford, participating in spontaneous street races at traffic lights.

7 key signs of depression

- You often experience protracted (several hours or more) periods of unmotivated sadness and hopelessness.

- You withdraw into yourself. It's hard for you to come out of your own shell. Therefore, you limit contacts even with family and friends.

- You have lost interest in those things that used to really cling to you, and have not gained anything new in return.

- Your appetite has changed: it has dropped sharply or, on the contrary, you no longer control how much and what exactly you eat.

- You regularly feel tired and lack energy. And such periods go on for quite a long time.

- You have problems with memory, concentration and decision making.

- Do you sometimes think about suicide. Catch yourself thinking that life has lost its taste for you.

Manic-depressive psychosis is when you recognize yourself in almost all the situations described above. At some point in your life, you clearly show signs of mania, and at other times, symptoms of depression.

However, sometimes it also happens that the symptoms of mania and depression manifest themselves at the same time and you cannot understand which phase you are in. This condition is called mixed mood and is also one of the signs of bipolar disorder.

What is bipolar disorder like

Depending on which episodes occur more often (manic or depressive) and how severe they are, bipolar disorder is divided into several types.

- Disorder of the first type. It is heavy, alternating periods of mania and depression are strong and deep.

- Disorder of the second type. Mania does not manifest itself too brightly, but it covers with depression just as globally as in the case of the first type. By the way, Catherine Zeta-Jones was diagnosed with it. In the case of the actress, the trigger for the development of the disease was throat cancer, which her husband, Michael Douglas, fought for a long time.

Regardless of what type of manic-depressive psychosis one is talking about, the disease in any case requires treatment. And preferably faster.

What to do if you suspect you have bipolar disorder

Don't ignore your feelings. If you are familiar with 10 or more of the above signs, this is already a reason to consult a doctor. Especially if from time to time you catch yourself in suicidal moods.

First, go to a therapist. The doctor will suggest that you do several tests, including a urine test, as well as a blood test for the level of thyroid hormones. Often, hormonal problems (in particular, developing diabetes, hypo- and hyperthyroidism) are similar to bipolar disorder. It is important to exclude them. Or treat if found.

Often, hormonal problems (in particular, developing diabetes, hypo- and hyperthyroidism) are similar to bipolar disorder. It is important to exclude them. Or treat if found.

The next step will be a visit to a psychologist or psychiatrist. You will have to answer questions about your lifestyle, mood swings, relationships with others, childhood memories, trauma, and family history of illness and drug incidents.

Based on the information received, the specialist will prescribe treatment. It can be both behavioral therapy and medication.

Let's finish with the phrase of the same Catherine Zeta-Jones: “There is no need to endure. Bipolar disorder can be controlled. And it's not as difficult as it seems."

Read also 😂😳😔

- 8 mental health myths to get out of your head

- 11 unexpected signs that you are a psychopath

- How to recognize alcoholism, depression and other mental disorders

- Thought echoes and 7 more signs that you have a schizophrenic in front of you

- From depression to rigidity: what is hidden behind popular psychological terms

Clinical features of bipolar affective disorder in elderly hospitalized patients | Shipilova

1. Mosolov SN, Kostyukova EG, Ushkalova AV. Clinic and therapy of bipolar depression. Moscow: AMA-PRESS, 2009.

Mosolov SN, Kostyukova EG, Ushkalova AV. Clinic and therapy of bipolar depression. Moscow: AMA-PRESS, 2009.

2. Rouch I, Marescaux C, Padovan C et al. Hospitalisa-tion for Bipolar Disorder: Comparison between Young and Elderly Patients. psychology. 2015;6:126–131. DOI:10.4236/psych.2015.61011.

3. Sajatovic M, Strejilevich SA, Gildengers AG et al. A report on olderage bipolar disorder from the International Society for Bipolar Disorders Task Force. Bipolar Discord. 2015;17(7):689–704. DOI:10.1111/bdi.12331.

4. Young RC, Gyulai L, Mulsant BH et al. Pharmacothera-py of Bipolar Disorder in Old Age. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2004;12(4):342–357. DOI:10.1097/00019442-200407000-00002.

5. Safarova TP, Sheshenin VS, Fedorov VV. Efficiency of psychopharmacotherapy in patients with geriatric psychiatric hospital with functional mental disorders. Psychiatry. 2013;57(1):24–33.

6. Lehmann SW, Forester BP. Bipolar Disorder in Older Age Patients. Springer International AG, 2017. DOI:10.1007/978-3-391-48912-4.

DOI:10.1007/978-3-391-48912-4.

7. Zung S, Cordeiro Q, Lafer B et al. Bipolar disorder in the elderly: clinical and socio-demographic characteristics. Scientia Medica, Porto Alegre. 2009;19(4):162–169.

8. Almeida OP, Fenner S. Bipolar disorder: similarities and differences between patients with ill-ness onset before and after 65 years of age. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2002;14(3):311–322. DOI:10.1017/s1041610202008517.

9. Banga A, Gyurmey T, Matuskey D et al. Late-life onset bipolar disorder presenting a case of pseudo-dementia: a case discussion and review of literature. Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 2013;86:235–244.

10. Oostervink F, Boomsma MM, Nolen WA. EMBLEM Advisory Board. bipolar disorder in the elderly; different effects of age and of age of onset. J. Affect. Discord. 2009;116(3):176–183. DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2008.11.012.

11. Forester BP, Ajilore O, Spino C, Lehmann S. Clinical Characteristics of Patients with Late Life Bipolar Disorder in the Community: Data from the NNDC Registry. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2015;23(9):977–984. DOI:10.1016/j.jagp.2015.01.001.

Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2015;23(9):977–984. DOI:10.1016/j.jagp.2015.01.001.

12. Azorin JM, Kaladjian A, Adida M, Fakra E. Late-on-set Bipolar Illness: The Geriatric Bipolar Type VI. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2012;18:208–213. DOI:10.1111/j.1755-5949.2011.00255.x.

13. Alves GS, Knöchel C, Paulitsch MA et al. White Matter Microstructural Changes and Episodic Memory Disturbances in Late-Onset Bipolar Disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:480. DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00480.

14. Almeida OP, Hankey GJ, Yeap BB et al. Older men with bipolar disorder: Clinical associations with early and late onset illness. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry.2018;33(12):1613–1619. DOI:10.1002/gps.4957.

15. Croarkin PE, Luby JL, Cercy K et al. Genetic Risk Score Analysis in Early-Onset Bipolar Disorder. J.Clin. Psychiatry. 2017;78(9):1337–1343. DOI:10.4088/JCP.15m10314.

16. Kalman JL, Papiol S, Forstner AJ et al. Investigating polygenic burden in age at disease onset in bipolar disorder: Findings from an international multicentric study. Bipolar Discord. 2019;21(1):68–75. DOI:10.1111/bdi.12659.

Bipolar Discord. 2019;21(1):68–75. DOI:10.1111/bdi.12659.

17. Rubino E, Vacca A, Gallone S et al. Late onset bipolar disorder and frontotemporal dementia with mutation in progranulin gene: a case report. Amyotroph. Later-al Scler. Frontotemporal Degener. 2017;18(7–8):624–626. DOI:10.1080/21678421.2017.1339716.

18. Dols A, Beekman A. Older Age Bipolar Disorder. Psychi-atr. Clin. North Am. 2018;41(1):95–110. DOI:10.1016/j.psc.2017.10.008.

19. Shipilova EU. Clinical types of bipolar affective disorder at a later age. Psychiatry. 2018;80(4):14–23.

20. Strejilevich SA, Szmulewicz AG, Igoa A et al. Epi sodic density, subsyndromic symptoms and mood instability in late-life bipolar disorders: a 5-year follow-up study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2019;Mar 12. DOI: 10.1002/gps.5094. [Epub ahead of print].

21. Young RC, Mulsant BH, Sajatovic M et al. A Randomized Double-Blind Controlled Trial of Lithium and Divalproex in the Treatment of Mania in Older Patients With Bipolar Disorder.