Behavioral interventions for children

Examples of Positive Behavioral Intervention Strategies

Print Version

- Examples of Positive Behavioral Intervention Strategies

A child with challenging behavior who has an Individualized Education Program (IEP), should have positive behavioral interventions included to help reduce challenging behaviors and support the new behavioral skills to be learned through the IEP goals. These interventions should be specific strategies that are positive and proactive, and are not reactive and consequence-based. The following list suggests some different kinds of positive behavioral interventions that could be useful:

- Clear routines and expectations that are posted and reviewed help children know what comes next in their school day, reducing anxiety or fear.

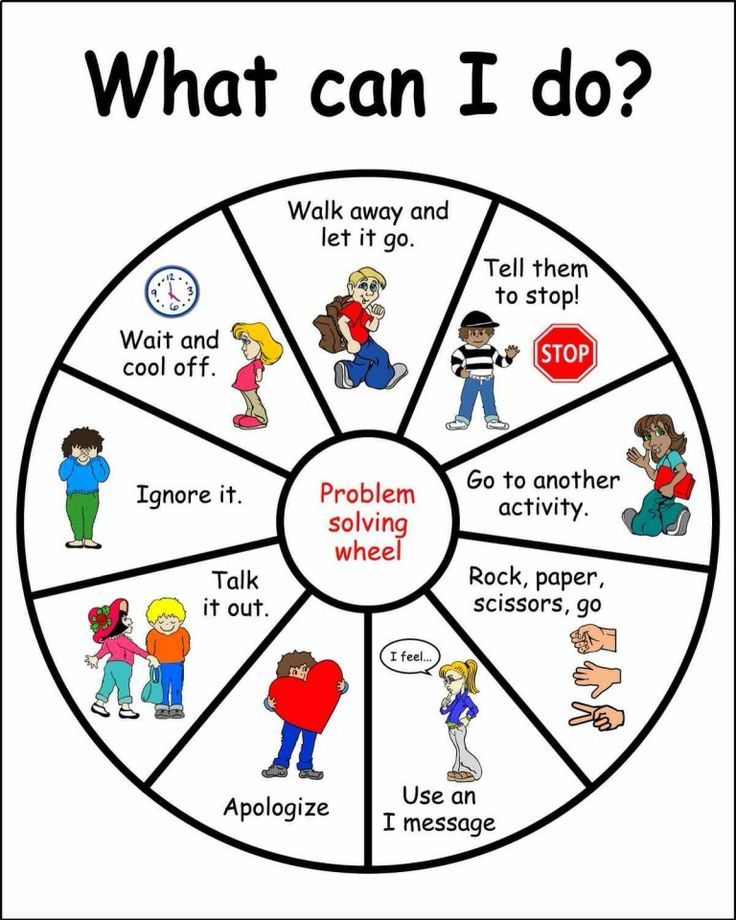

- Stop, Relax, and Think strategy teaches children how to think about a problem and find a solution. Children learn the following steps:

- Define the problem.

- Decide who “owns” the problem.

- Think of as many solutions as possible to solve the problem.

- Select a solution to try.

- Use the solution.

- Evaluate its success.

After children understand the steps, role-play and practice can help the process become habit. Helping children to recognize their own response to stress (clenched hands, voice tone, etc.) may become part of the instruction needed to use this strategy effectively. Practicing and being successful with these steps can take time for children. Therefore, it is important to consider what kind of support a child may need that will help reinforce progress.

- Define the problem.

- Pre-arranged signals can be used to let a child know when he or she is doing something that is not acceptable. A hand motion, a shake of the head or a colored card placed on a desk as the teacher moves through the room could alert the child without drawing attention to the child or the behavior.

It is important to develop a signal that the child and teacher agree on using and for what purpose.

It is important to develop a signal that the child and teacher agree on using and for what purpose. - Proximity control means that a teacher or adult moves closer to the child in a gentle way. If the teacher does not get the child’s attention by using cues, then he or she may move closer to the student or give the lesson while standing near the child’s desk.

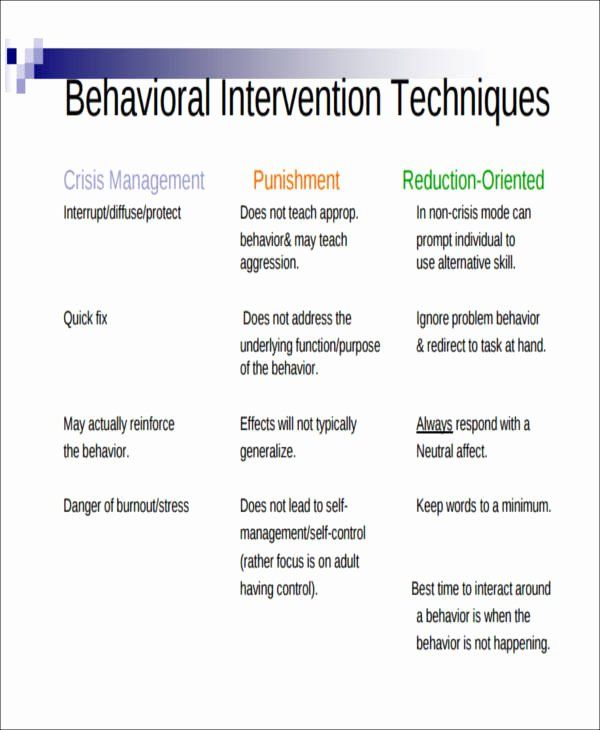

- Planned response method is useful in stopping non-serious behaviors that are bothersome to other children or adults nearby.

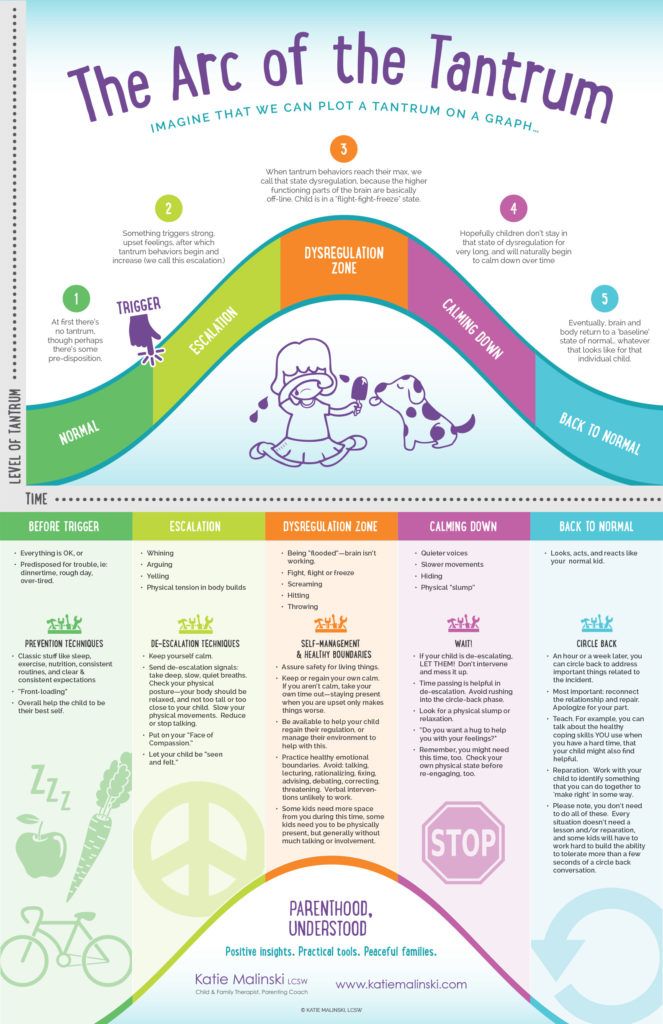

For example, students who interrupt the class to attract the teacher’s attention usually are successful in getting the teachers to respond. Planned response method acknowledges that children’s challenging behaviors serve a purpose. If the purpose of that behavior is to gain adult attention, then not providing attention means that the behavior does not work. The behavior lessens over time and eventually disappears. Ignoring non-serious behavior is especially useful for parents when their child is having a tantrum for attention. Many adults find it difficult to ignore behaviors, especially if the behaviors interrupt what the adult is doing. Also, attention-seeking behaviors often get worse before they eventually go away.

Many adults find it difficult to ignore behaviors, especially if the behaviors interrupt what the adult is doing. Also, attention-seeking behaviors often get worse before they eventually go away.Planned response method is not suitable for behaviors that are extremely disruptive. This method also may not work if other children laugh at the problem behaviors the adult is trying to ignore. Some behaviors, including those that are unsafe or that include peer issues such as arguing, can grow quickly into more serious behaviors. It may not be possible to ignore these kinds of behaviors. The process of ignoring the behavior should never be used for unsafe behaviors. As children grow older and want attention more from their friends than from adults, the planned response method is less useful.

- Discipline privately. Many children see it as a challenge when teachers attempt to discipline them in front of their peers. Children rarely lose these challenges, even when adults use negative consequences.

Young people can gain stature from peers by publicly refusing to obey a teacher. A child is more likely to accept discipline if his or her peers are not watching the process.

Young people can gain stature from peers by publicly refusing to obey a teacher. A child is more likely to accept discipline if his or her peers are not watching the process. - Find opportunities for the child to help others. For example, a child who is using negative behaviors as a way to get out of class could be given the task of running an errand for the teacher to the front office. Peer involvement is another motivator for appropriate behavior. Finding times for the child who uses disruptive behavior to get attention from his classmates to help another student positively engages attention and can build rapport.

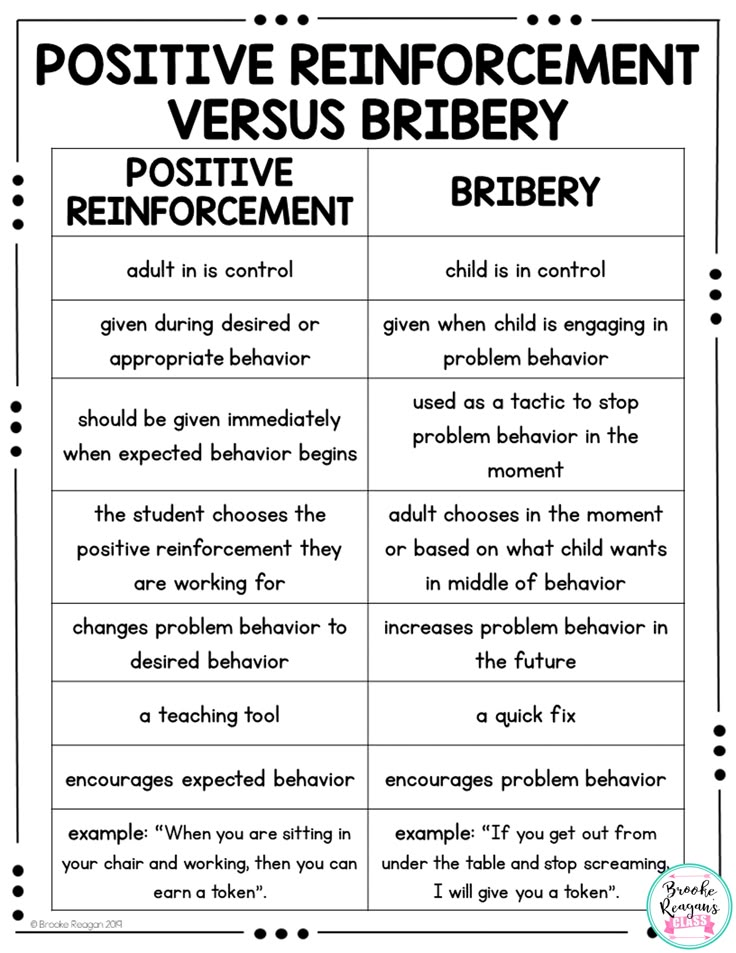

- Positive phrasing lets children know the positive results for using appropriate behaviors. As simple as it sounds, this can be difficult. Teachers and parents are used to focusing on misbehavior. Warning children about a negative response to problem behaviors often seems easier than describing the positive impact of positive behaviors.

Compare the difference between positive phrasing and negative phrasing:

Positive phrasing: “If you finish your reading by recess, we can all go outside together and play a game.”

Negative phrasing: “If you do not finish your reading by recess, you will have to stay inside until it’s done.” - State the behavior you want to see. For example, say “I like seeing how everyone lines up so quickly and quietly”, instead of “Stop bothering the other students in line.”

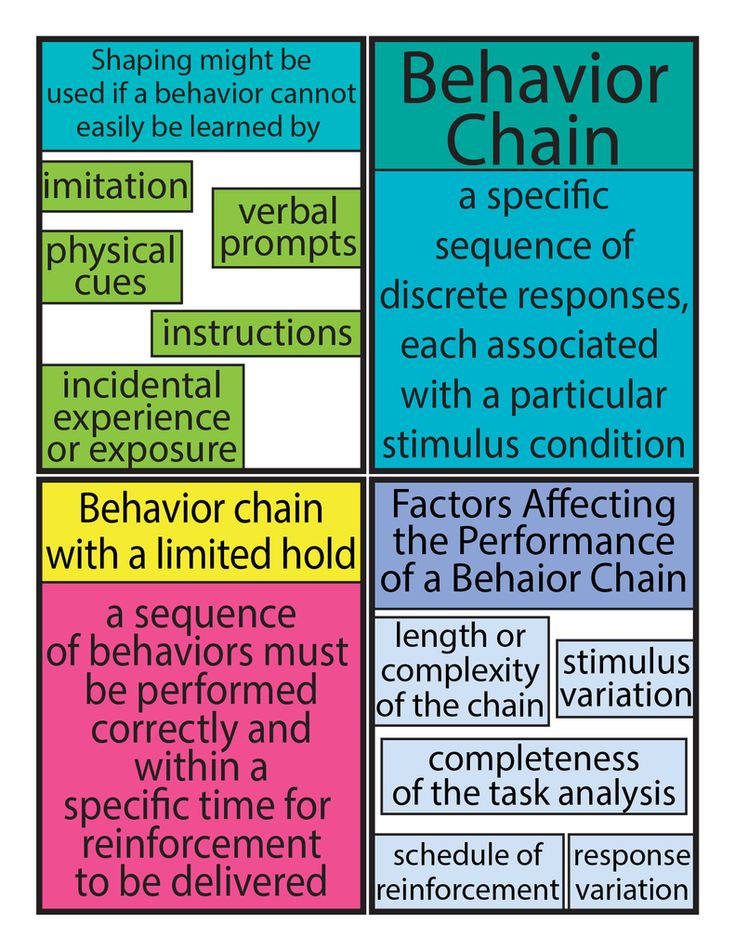

- Behavior shaping acknowledges that not all children can do everything at 100 percent. If a child does not turn in papers daily, expecting that papers will be turned in 100 percent of the time is not realistic. By rewarding small gains and reinforcing these gains as they occur, children learn how to stick with a task and to improve the skill.

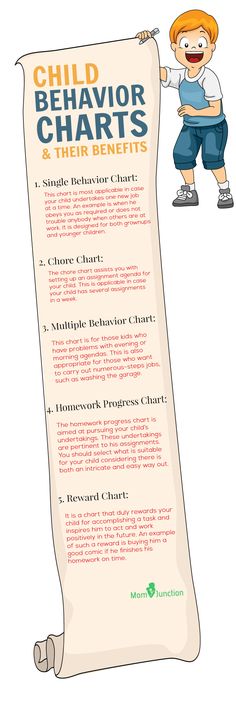

- Tangible, token, and activity reinforcers are also effective ways to encourage and support appropriate behavior.

Tangible reinforcers can be awards, edibles or objects. Token reinforcers are tokens or points given for appropriate behavior that can be exchanged for something of value. Activity reinforcers are probably the most effective and positive as they allow students to participate in preferred activities, usually with other students, which also builds in social reinforcement.

Tangible reinforcers can be awards, edibles or objects. Token reinforcers are tokens or points given for appropriate behavior that can be exchanged for something of value. Activity reinforcers are probably the most effective and positive as they allow students to participate in preferred activities, usually with other students, which also builds in social reinforcement.

Behavior Intervention: Definition, Strategies, and Resources

When faced with difficult situations, children may occasionally lose their temper or experience emotional outbursts. Behavior issues, such as uncontrolled tantrums, aggressive physical behavior, and repetitive emotional outbursts, may interfere with children’s ability to function in school and may cause turmoil at home.

Targeted behavior interventions tailored to meet each child’s needs can prevent these challenging behaviors and teach children to use communication through positive behaviors in response to challenges. Effective behavior intervention plans can effectively minimize negative behaviors and ensure a healthy educational environment that optimizes learning and can improve family interactions.

Effective behavior intervention plans can effectively minimize negative behaviors and ensure a healthy educational environment that optimizes learning and can improve family interactions.

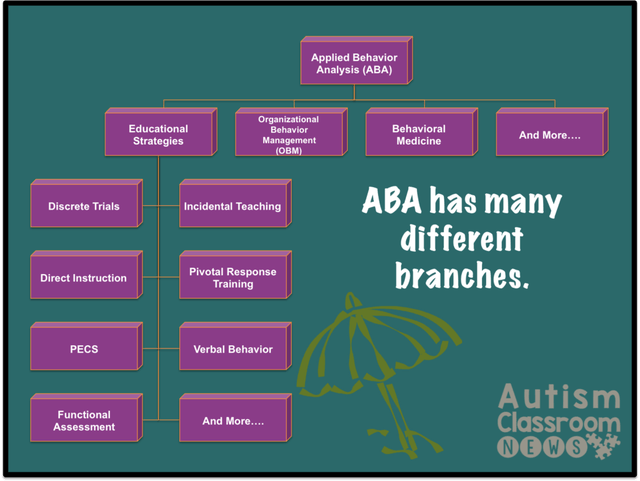

This article presents examples of positive behavior intervention plans and strategies. It describes applied behavior analytic assessment and intervention, including the ABC model of behavior assessment. It also outlines the benefits of earning a Master of Science in Applied Behavior Analysis to prepare for a career in applied behavior analysis.

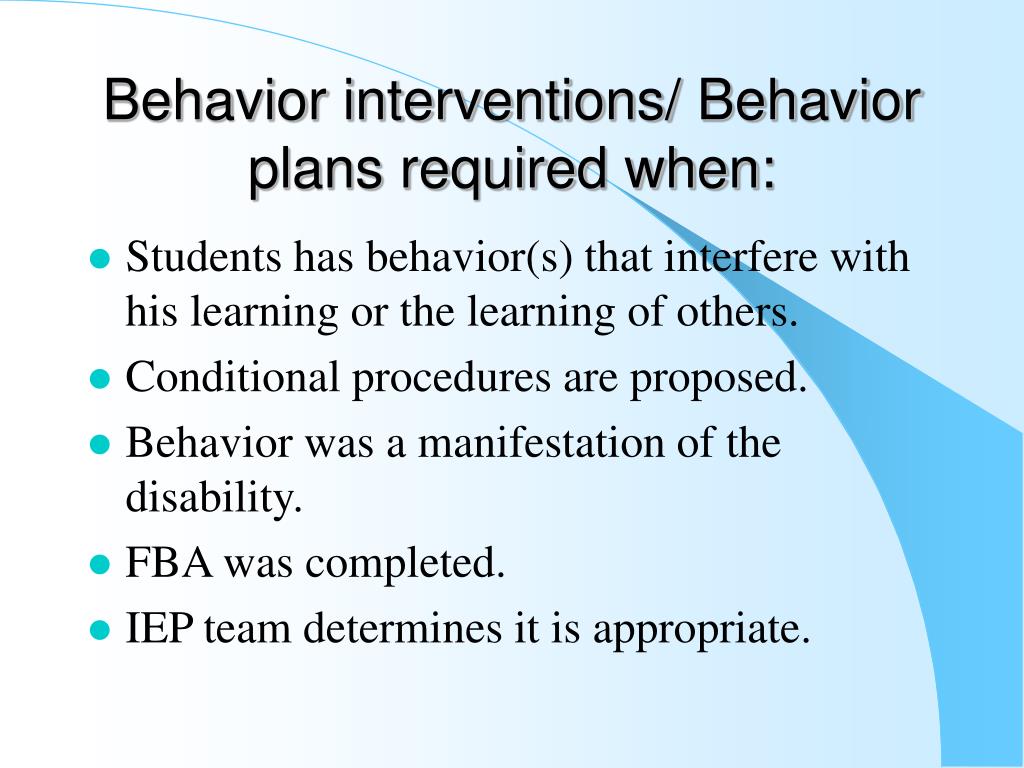

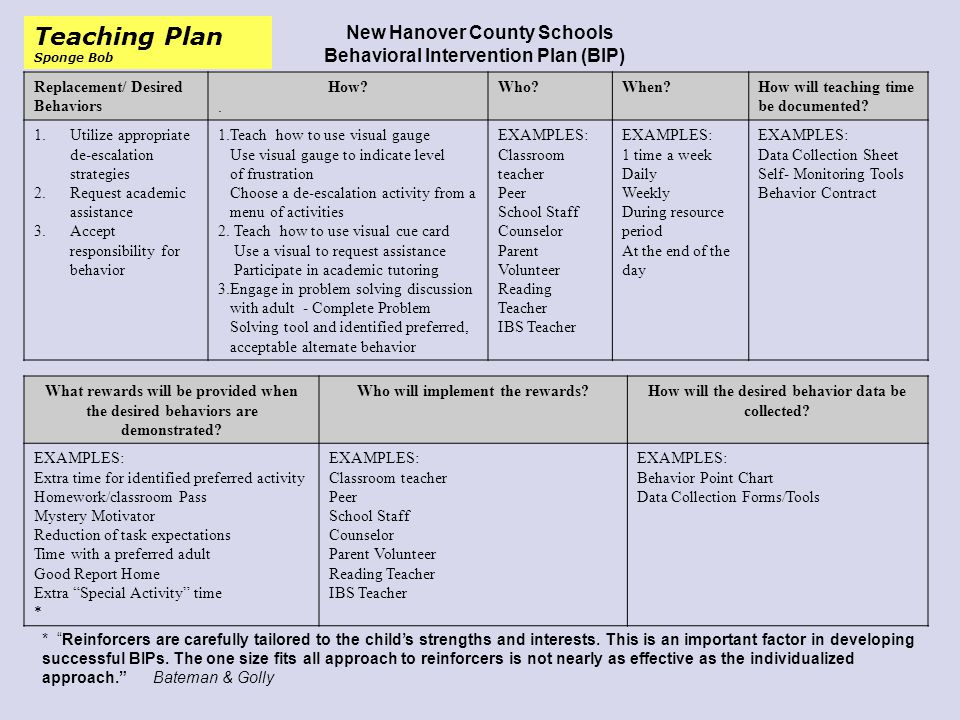

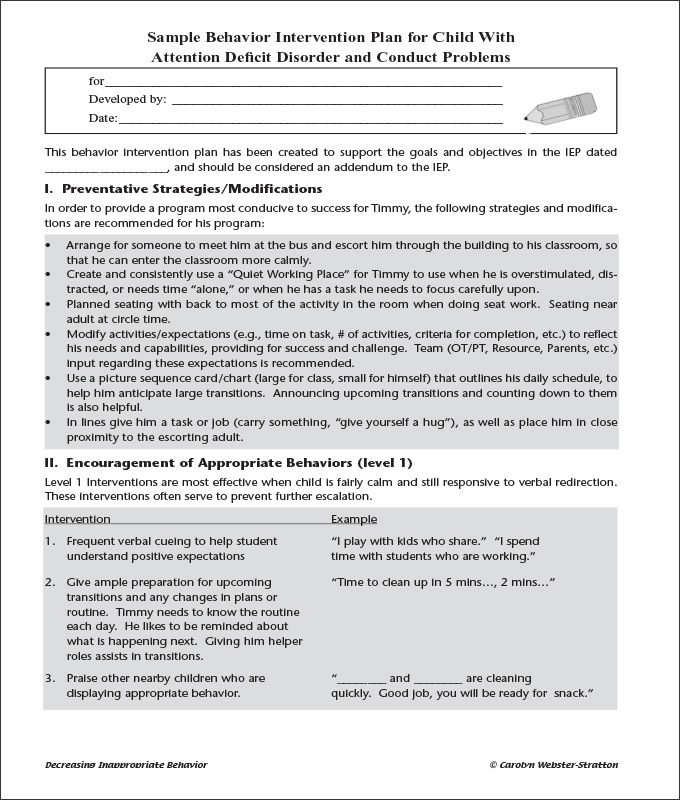

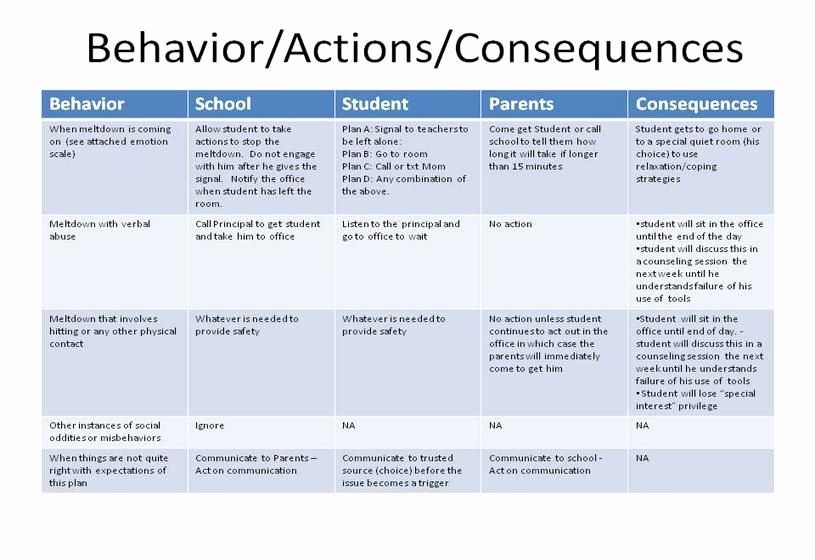

What Is a Behavior Intervention Plan?A child who struggles in school may require an individualized education program (IEP) that describes the goals that a team of educators have established for the child during a school year. Key to the IEP’s success is identifying any special support required to reach specific goals. The plan’s special support needs often include a behavior intervention plan that is designed to teach and reinforce positive behaviors.

What is a behavior intervention plan? BIPs, which are also called positive intervention plans, are customized to the needs, abilities, and skills of the child:

- They are individualized.

- They are positive.

- They are consistent.

The BIP has many distinct components:

- Skills training to promote appropriate behavior

- Alteration of the classroom or learning environment to minimize or eliminate problem behaviors

- Strategies to encourage appropriate behaviors that replace problem behaviors

- The support the child will need to behave appropriately

- Collection of data to measure the child’s progress

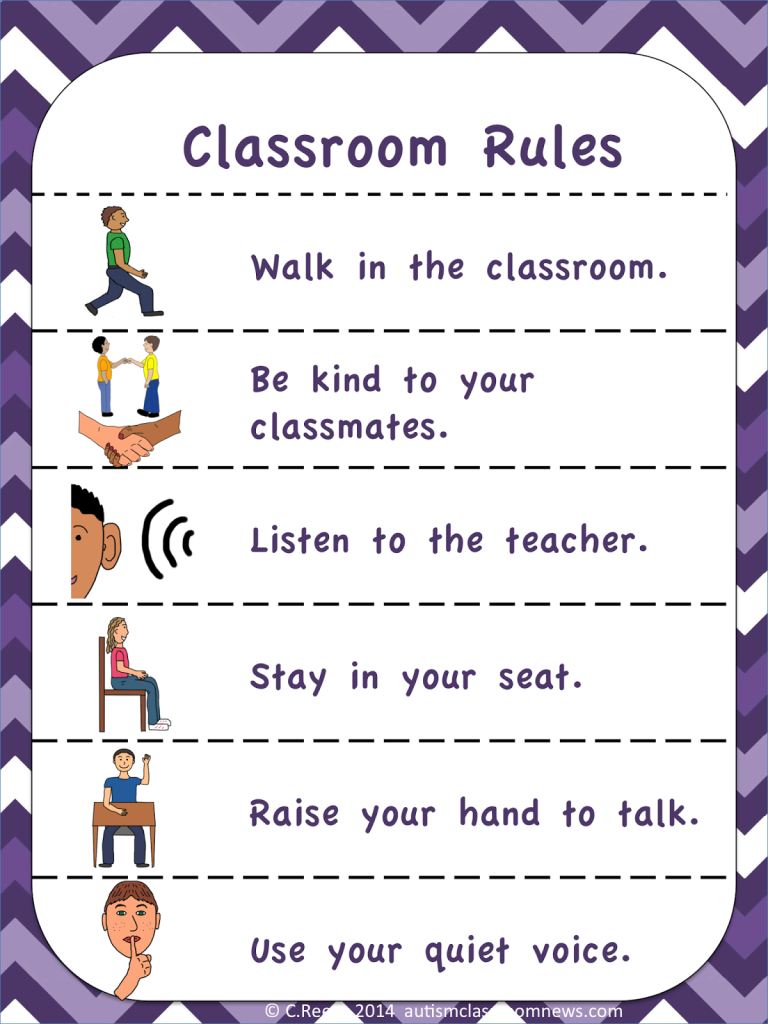

Teachers understand the importance of setting classroom rules and expectations. The rules and expectations must be clearly communicated to students and enforced when necessary. The intervention plan is intended to guarantee that all children benefit from a safe, nurturing learning environment. The behaviors that an intervention plan addresses may include some of the following:

The intervention plan is intended to guarantee that all children benefit from a safe, nurturing learning environment. The behaviors that an intervention plan addresses may include some of the following:

- Making noise in class

- Disrupting other students

- Talking out of turn

- Intentionally creating a power struggle with the teacher

- Distracting the learning process by repeatedly arguing over minor issues

- Brooding, rudeness, or negative mannerisms in class

- Overdependence on teachers or other students

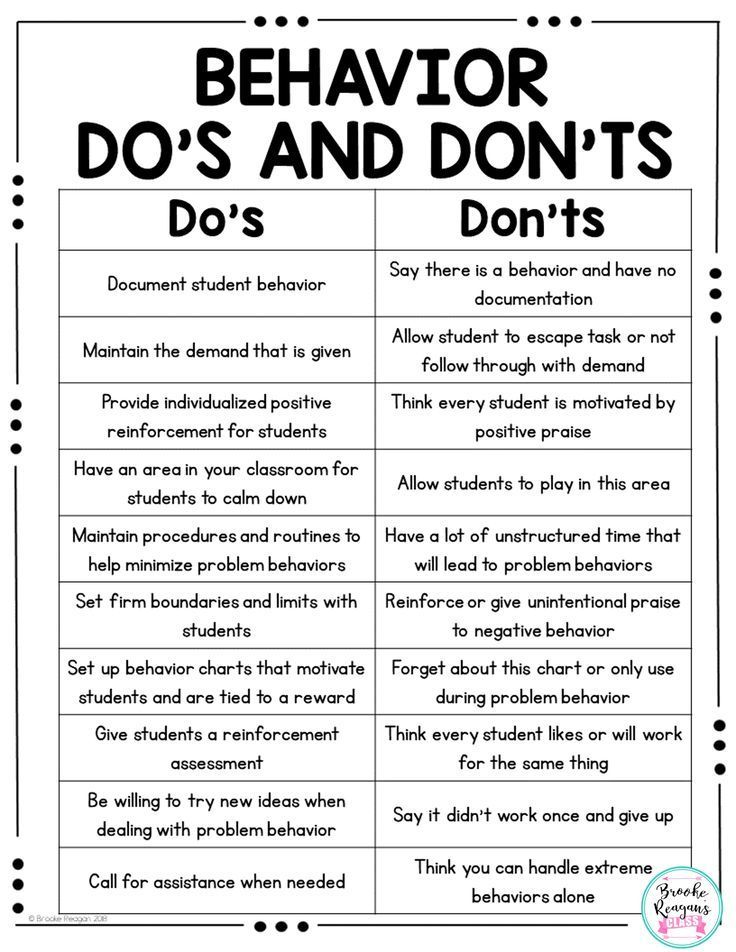

To manage their classrooms, many teachers tend to focus on problem behaviors. Another way to prevent and reduce challenging behaviors is by acknowledging correct behaviors and praising small successes.

Vermont-NEA (The Union of Vermont Educators) describes strategies for effective behavior management in educational settings:

- Stay calm at all times, and demonstrate to the students that the teacher is in charge.

- Give instructions as simple, direct statements rather than in the form of a question or request.

- Make sure that students know when it’s time for them to give the teacher their full attention.

- Use the student’s name when giving praise and when disciplining, and make sure the student understands which action triggered the praise or discipline.

The success of a BIP depends on the participation of the students in crafting plans that address their unique situation, character, and personality. Encouraging the student to participate in planning may help build rapport and motivate the student to agree to pursue the plan’s goals. The right plan will be something the student looks forward to rather than something seen as a chore or an embarrassment.

- Ask the student about the goals to be achieved, and include those goals in the plan along with the goals set by parents and educators.

- Make sure that the student understands which behaviors to exhibit in specific situations, so the student will be able to recognize behavioral improvement.

- Provide highly motivating reinforcers, such as items or rewards that would motivate the student, for appropriate behaviors to encourage participation.

- Include in the plan graphics or other elements that represent the student’s interests, such as favorite movie or cartoon characters and other items that the student will respond favorably to.

In a paper published in the journal Behavior Analysis in Practice, researchers Collin Shepley and Jennifer Grisham-Brown identify gaps between research and practice in the application of behavioral analysis in schools. The researchers point out that more than 25% of applied behavior analysts work in schools, which is the second-largest employment sector for applied behavior analysts after health care.

However, the emphasis on blended practices that individualize education for all students requires the participation of many different parties, including educators, behavior analysts, and parents. A curriculum framework that supports blended practices combines data-driven decision making; professional development; and a leadership plan involving teachers, children, and families.

The role of behavior analysts in such team settings entails several activities:

- Identifying the behaviors to target for instruction

- Determining the prerequisite skills to address the target behavior

- Selecting socially appropriate replacement behaviors based on the functional behavior assessment

The researchers emphasize the importance of collaborative working relationships to the long-term success of positive behavioral interventions. Elements of success include agreeing on roles and responsibilities, understanding the goals of the interventions, and establishing criteria for terminating or reevaluating the relationship.

A key to the success of positive behavior interventions is consistency. Disruptions in students’ routines, such as the response to the COVID-19 pandemic, make it even more difficult to implement and maintain intervention plans. In addition to requiring drastic changes in children’s daily routines, the pandemic creates anxiety and uncertainty that can discourage positive behaviors.

The Texas Education Agency provides a checklist that parents and educators can use to support challenging behaviors at home:

- Adjust the child’s IEP and BIP to the home learning environment, and encourage parents and guardians to promote replacement behaviors and self-regulation skills.

- Remove distractions from the home learning environment, keep all required materials well organized, and set a schedule that matches the child’s learning style (including breaking assignments into small chunks).

- Encourage parents to respond calmly when a child misbehaves and to focus on the replacement behavior using the same reinforcers that are applied in school settings.

A positive behavior intervention system integrates data, support systems, and intervention practices with the goal of improving social and academic outcomes for individuals with behavior issues. This proactive, systematic framework drives the success of the intervention.

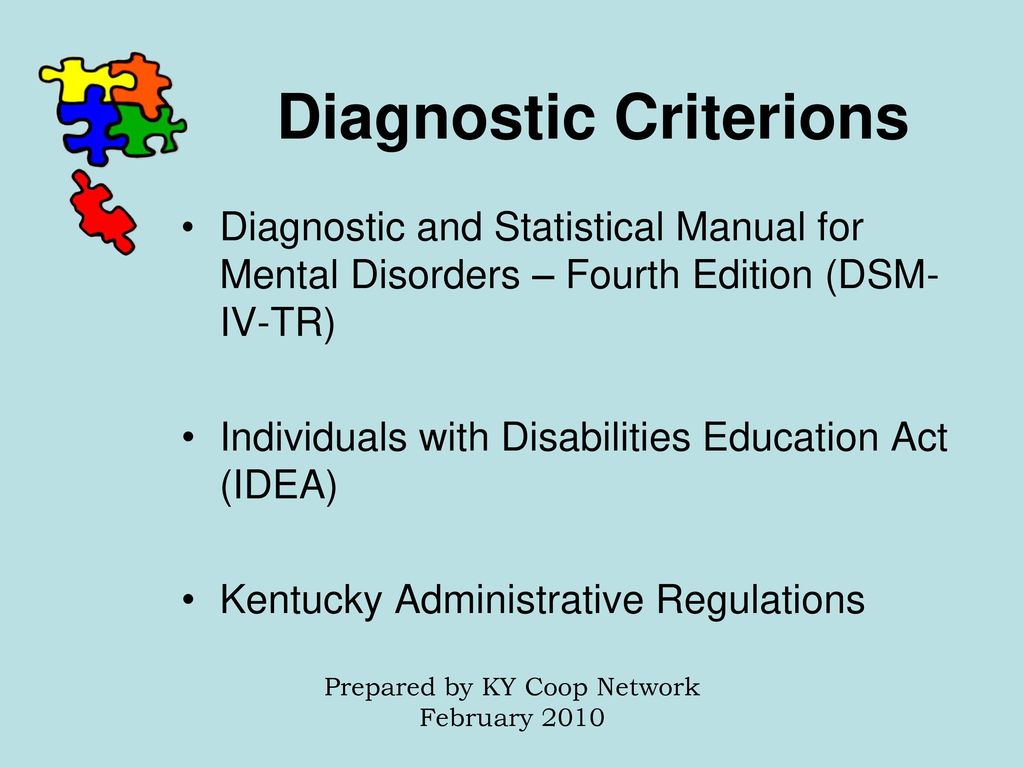

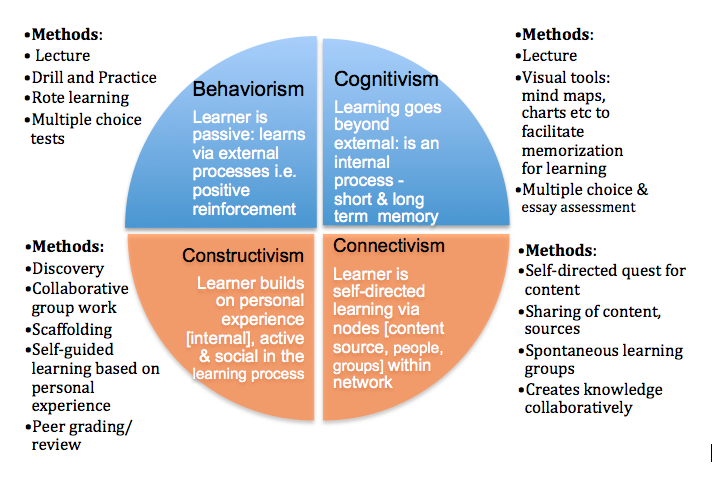

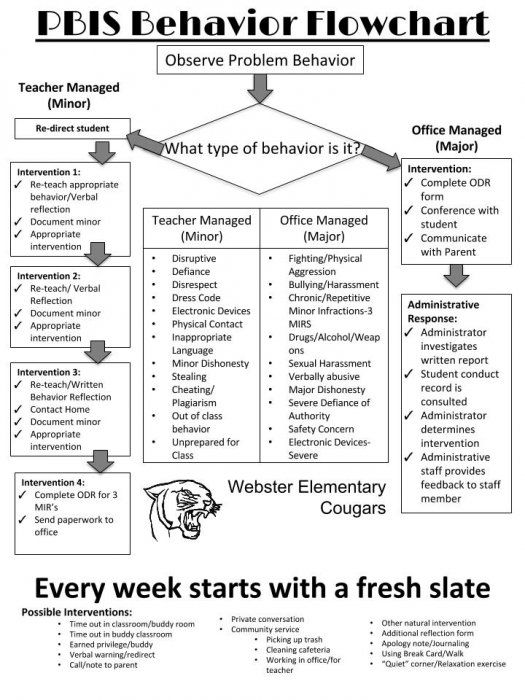

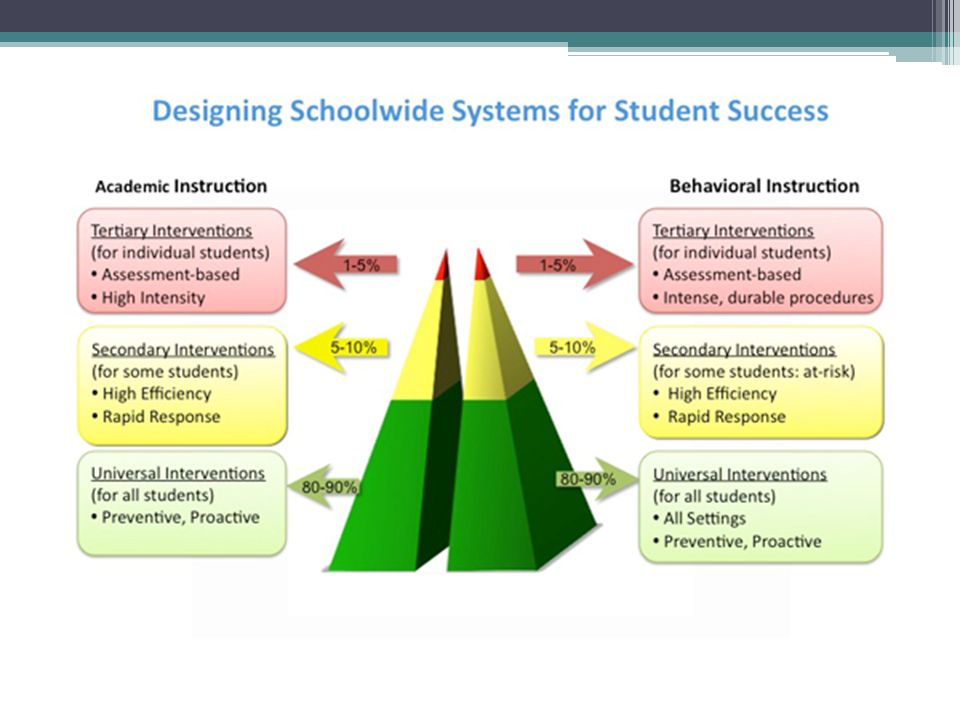

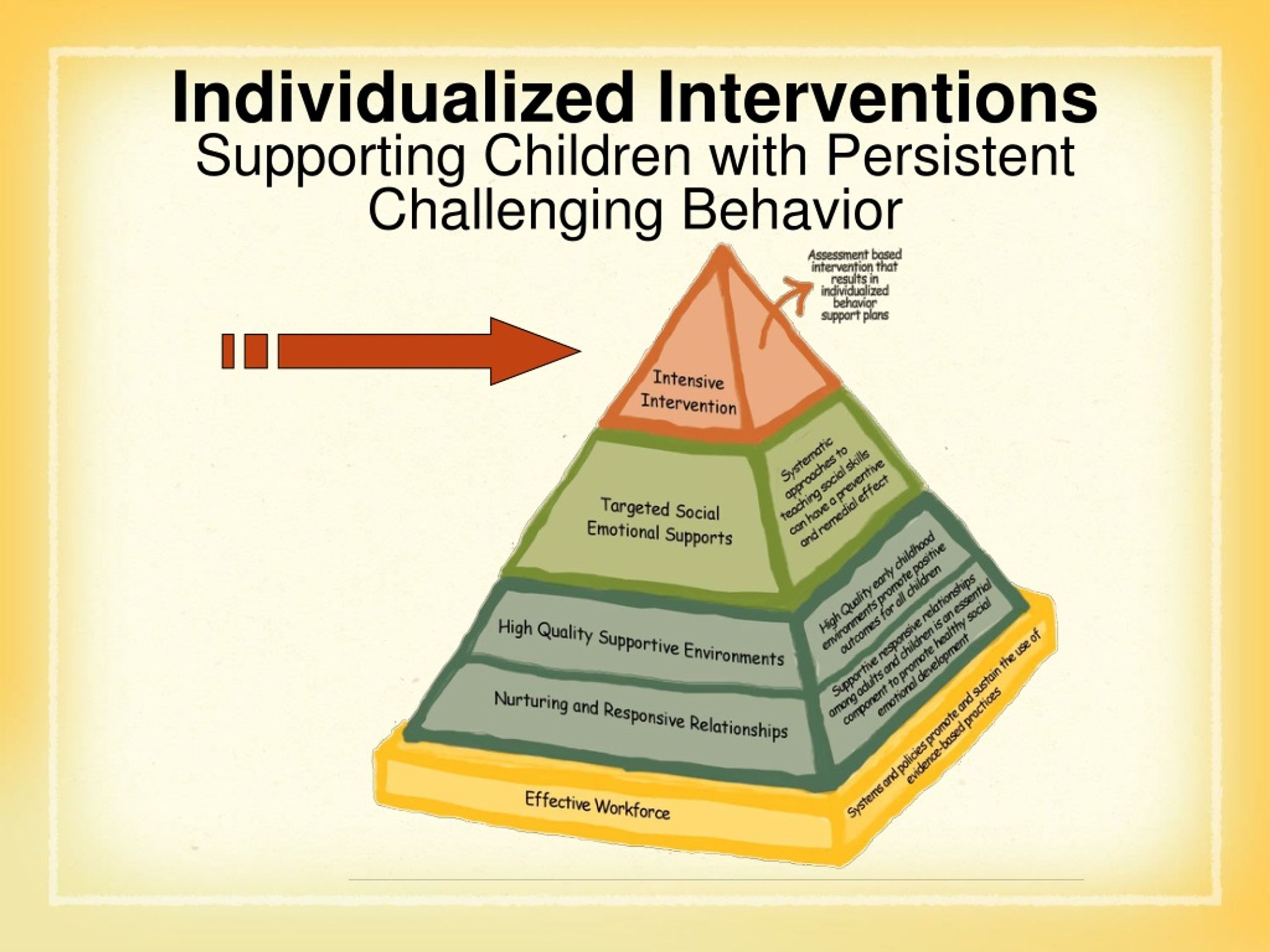

Integrating Data, Support Systems, and Intervention PracticesThe Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) Technical Assistance Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) describes the three-tiered evidence-based framework designed to ensure the social and academic success of all students:

- Tier 1, Universal Prevention, applies to all students and emphasizes prosocial skills and expectations by teaching appropriate behaviors.

- Tier 2, Targeted Prevention, applies to some students and focuses on supporting students who are at risk of developing more serious behavior problems.

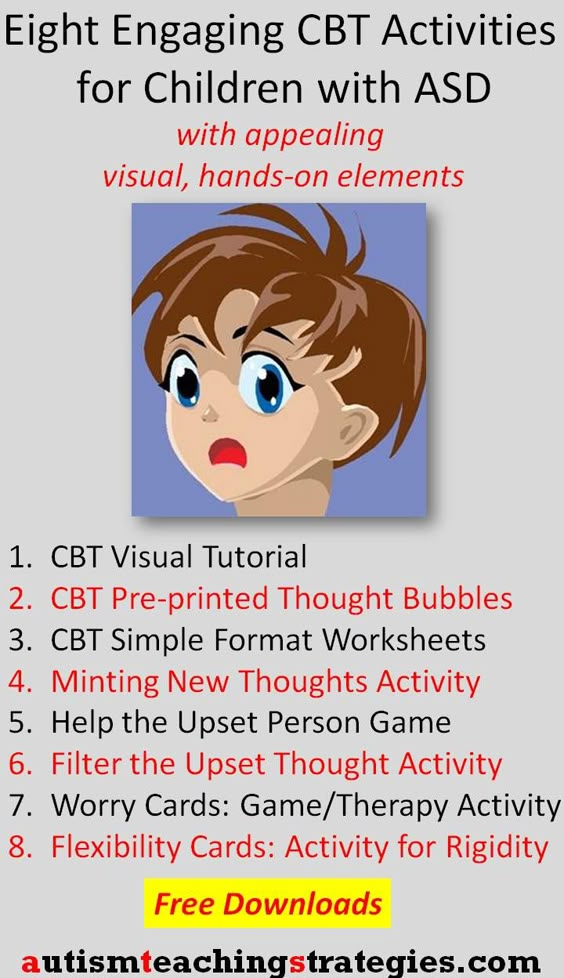

- Tier 3, Intensive, Individualized Prevention, applies to the small proportion of students whose behavior doesn’t improve after applying Tier 1 and Tier 2 support. The students in this group include those with developmental disabilities, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and emotional and behavioral disorders.

All three tiers combine three components to achieve their desired outcomes:

- The systems component encompasses the mechanisms used by the school to design and implement educational practices that promote student achievement.

- The data component covers the collection, analysis, and application of data about students to improve academic outcomes.

- The practices component describes the implementation of research-backed strategies that achieve the goals targeted by the BIP.

Just as IEPs are geared to individual students, the multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) involves the entire school community in improving behavioral and academic outcomes. The goal of the MTSS process is to provide every student with early access to individualized academic and behavior interventions based on the student’s specific needs.

The goal of the MTSS process is to provide every student with early access to individualized academic and behavior interventions based on the student’s specific needs.

Ensuring effective social and emotional functioning requires positive behavioral supports to increase academic engagement, minimize problem behaviors, and improve academic outcomes. Achieving this goal requires strong leadership and collaboration among educators and behavior interventionists as part of teams that include principals, classroom teachers, school psychologists, social workers, and guidance counselors.

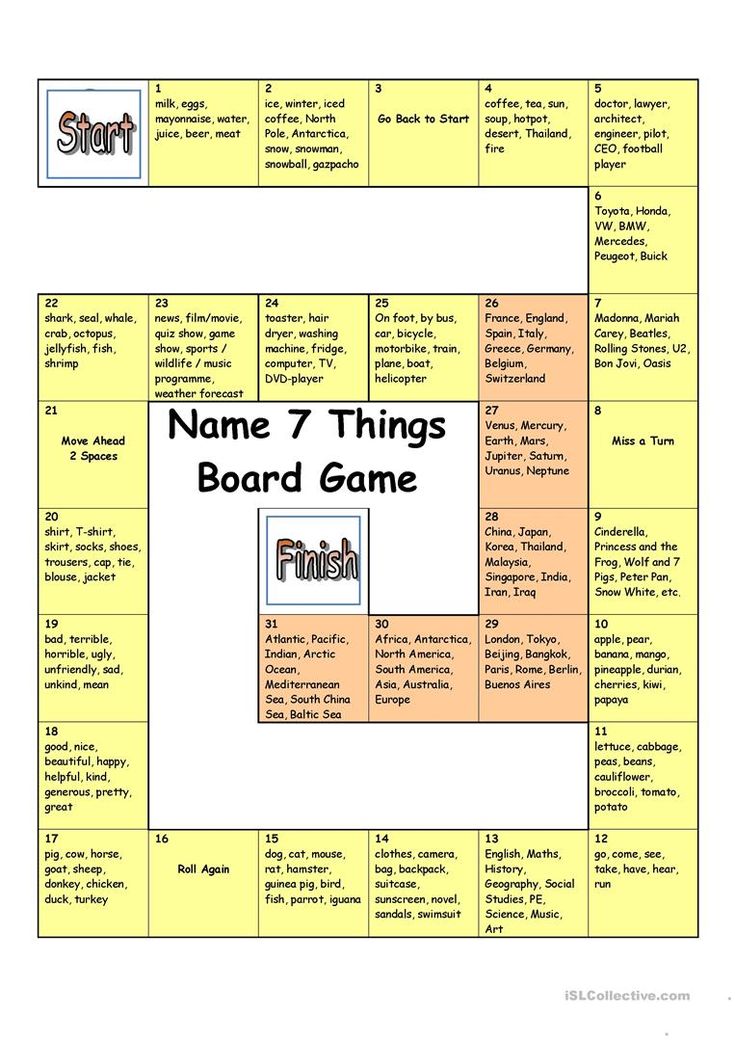

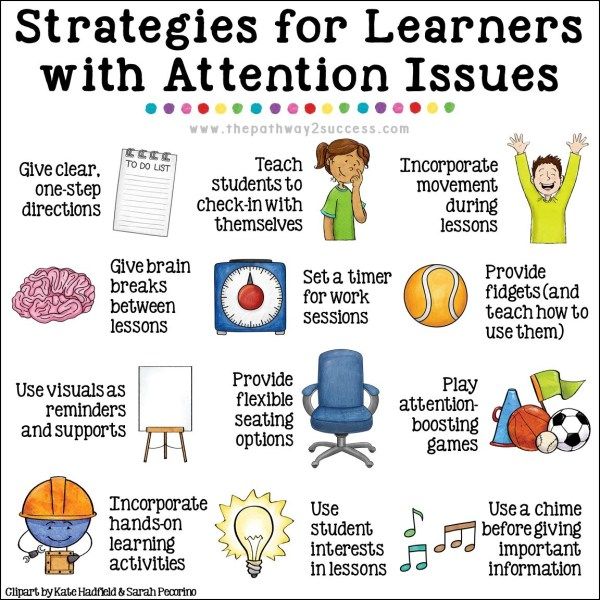

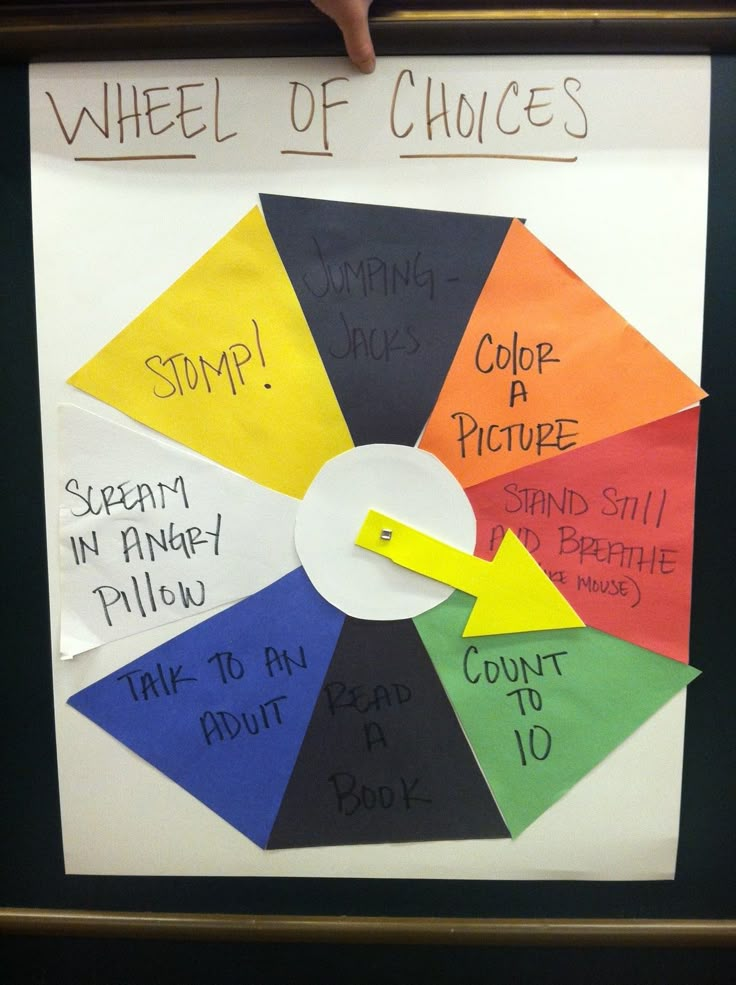

Examples of Positive Behavior Intervention StrategiesPositive behavior intervention strategies include designing routines, implementing silent signals, assigning tasks, and setting expectations. These strategies help encourage positive behaviors from individuals while simultaneously suppressing negative behaviors.

The goal of intervention strategies is to understand that the problem behaviors are a means of communicating and to respond with compassion. This establishes a trusting relationship between students, families, teachers, and behavior analysts that shifts from fixing students to understanding them.

This establishes a trusting relationship between students, families, teachers, and behavior analysts that shifts from fixing students to understanding them.

Routines are a component of every successful classroom, but they’re also effective in addressing inappropriate behaviors in home settings. Routines provide students with more time to spend on learning by reducing the time required to transition from one task or activity to another.

Classroom routines describe the procedures for many common activities:

- Turning in work

- Passing out materials

- Making up for missed work

- Establishing arrival and dismissal procedures

- Providing options to occupy students when they finish an assignment

- Transitioning between activities

The use of silent signals to discourage problem behaviors in the classroom provides many benefits:

- They establish a working relationship with the student without calling out the negative behavior.

- They’re quick and easy, so there’s no loss of instruction time.

- They help build the student’s self-esteem and encourage the student to participate.

Examples of silent signals include returning the student’s attention to the current activity or assignment, redirecting misbehavior, helping students who struggle to talk in front of the class, encouraging reluctant students to participate, and praising students when they behave well or succeed at a task.

To use silent signals, teachers should meet with the student individually to explain their tacit communication methods, allow the student to decide the methods whenever possible, set a cue for the student to use when wanting to participate, and use as many positive and encouraging signals as negative ones.

Applying Task AssignmentsThe curricula and assignments can be modified in many ways to promote positive behaviors in students:

- Ensure the material is appropriate for the students and properly motivates them to learn.

- Change the number or difficulty of assignments to avoid overwhelming students.

- Divide difficult assignments into several parts.

- Assign tasks that require the active participation of the students.

- Shorten lessons or change the pace of the instruction.

- Help students maintain a planner for their assignments.

- Use multiple modes of instruction, such as video, audio, and hands-on exercises.

- Increase the amount of reinforcement and the frequency of task-related recognition.

Before teachers can set expectations for students, they must have a plan for operating the classroom. They must understand the characteristics of their students, and they must know what the school expects students to achieve. The expectations communicate to students how they’re required to act toward other students and school staff. They also let students know the standards they’re expected to live up to and the structure in which their education will be provided.

The expectations should be developed with input from students to increase their sense of ownership and make it more likely they’ll behave as the guidelines describe. The expectations must be appropriate to the grade level and abilities of students. They must be posted prominently and communicated clearly and regularly to students. The consequences for failing to meet the expectations must also be clear to students.

Resources for Creating a Positive Behavior Intervention SystemHere are some resources for developing and implementing PBIS strategies:

- The OSEP Technical Assistance Center on PBIS provides a guide to resources for using PBIS to increase racial equity, as well as four resources designed to support students during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services features a list of resources available through various federal government agencies. The department also offers information for educators and families on services available through the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

- The National Education Association has compiled guidelines for schools in the process of implementing positive behavior intervention systems.

The tiered nature of positive behavior intervention and support strategies is designed to accommodate the education and social needs of all students in school and at home. Particular systems and practices correspond to how the three tiers meet the needs of students in general, students who exhibit skills deficits, and students who need IEPs:

- Universal Prevention (Tier 1) addresses the behavior and academic needs of all students through the core program.

- Targeted Prevention (Tier 2) addresses the needs of some students who require help to develop specific skill deficits.

- Intensive, Individualized Prevention (Tier 3) addresses the higher level of attention and resources a few students will require to improve behavior and academic performance.

Applied behavior analysts work with educators and parents to implement each of the three support strategies in classroom and home settings as part of comprehensive positive behavior intervention plans.

Strategies and Goals Between the Three TiersTier 1 serves as the foundation for Tier 2 and Tier 3 by creating a school-wide program that identifies students who need additional support.

- The Tier 1 leadership team monitors school-wide data and makes sure that all students in need have equal access to support services. The team also evaluates the program’s overall effectiveness.

- The Tier 2 team identifies students who are at risk of developing more serious behavior and academic problems. The team participates in group interventions in which 10 or more students typically participate.

- The Tier 3 team works with the 1% to 5% of students whose needs aren’t met by the programs offered in the first two tiers. The team often works directly with individual students who have disabilities, emotional or behavioral disorders, or no diagnostic label.

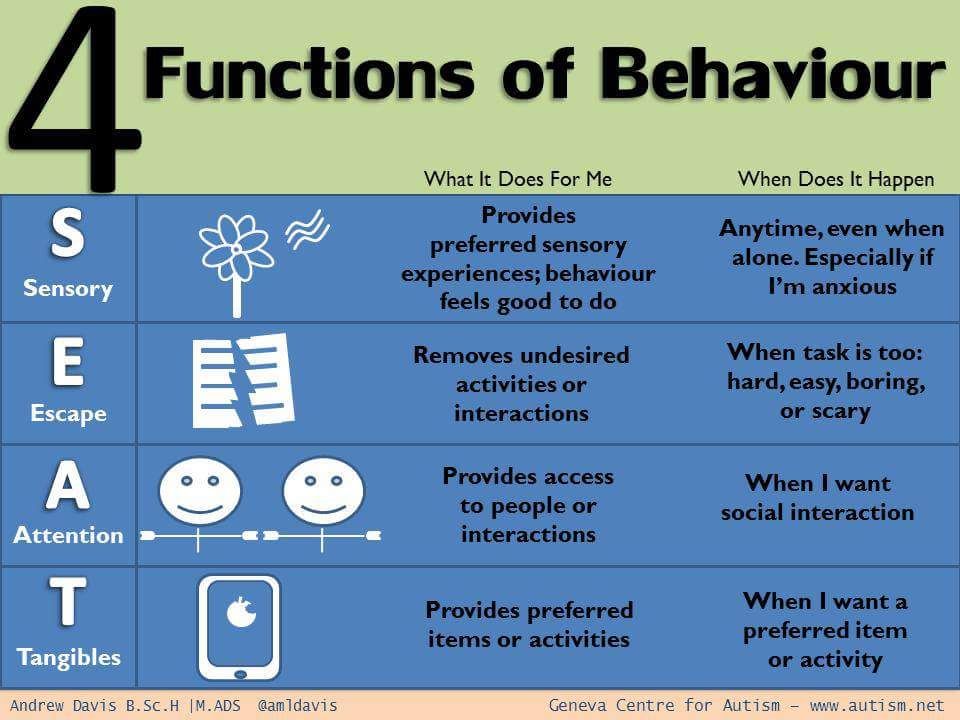

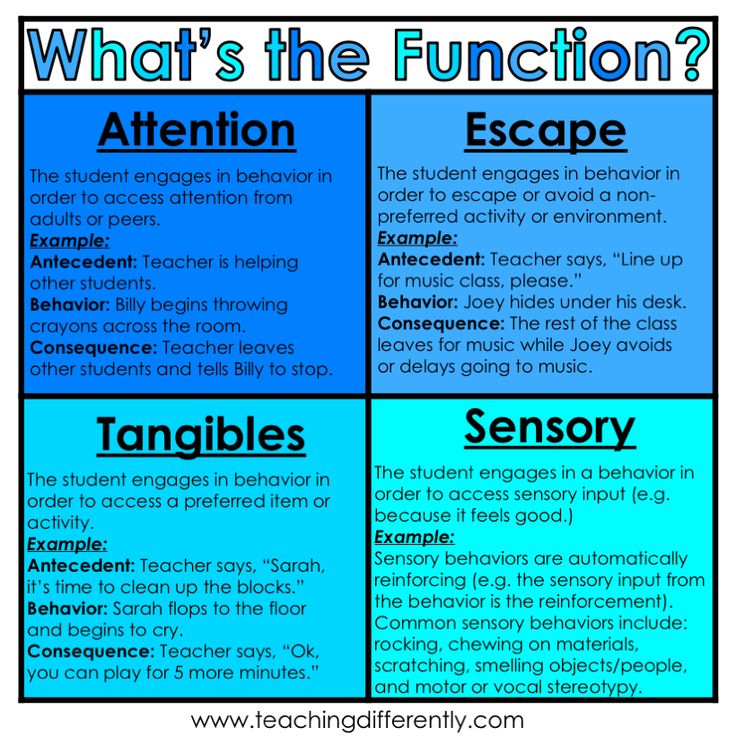

Applied behavior analysis studies the environmental events that are critical to understanding and changing children’s behaviors in the classroom and in the home. It examines behaviors based on the relationship between antecedents and consequences:

- Antecedents describe what happened just prior to the behavior.

- Consequences describe what happened immediately after the behavior.

For Tier 1 and Tier 2 students, the support strategy can be integrated with standard instruction and may require occasional instruction in small group settings. Tier 3 students in particular are likely to require supplementary aids and services in education settings. The services must be effective in reaching the student’s education and behavior goals without stigmatizing the student.

The skills taught to Tier 3 students focus on adjusting to classroom learning:

- Participate and learn in a group.

- Initiate and sustain reciprocal peer interactions.

- Complete seatwork assignments.

- Communicate needs clearly.

- Follow classroom routines.

- Reduce problem behaviors that interfere with learning.

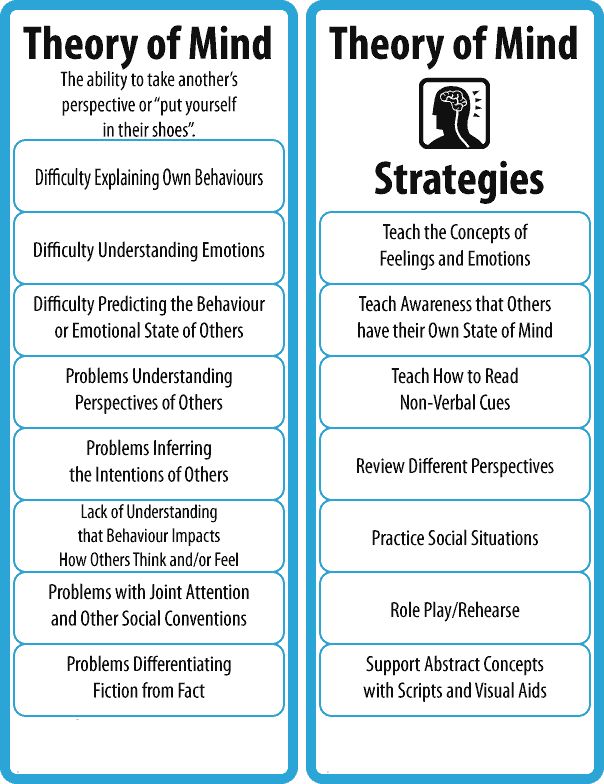

- Self-regulate, make inferences, and consider the perspective of others.

Applied behavior analytics has proven effective in teaching skills that are useful in the home and community. Instruction may take place one-to-one or in groups using techniques like positive reinforcement to encourage appropriate behaviors in various settings.

- In collaboration with the family, the analyst first establishes a goal behavior.

- Each time the student uses the behavior or skill, the student is rewarded in a meaningful way.

- Over time, the rewards encourage repetition of the goal behavior or skill, and it becomes a meaningful behavior change.

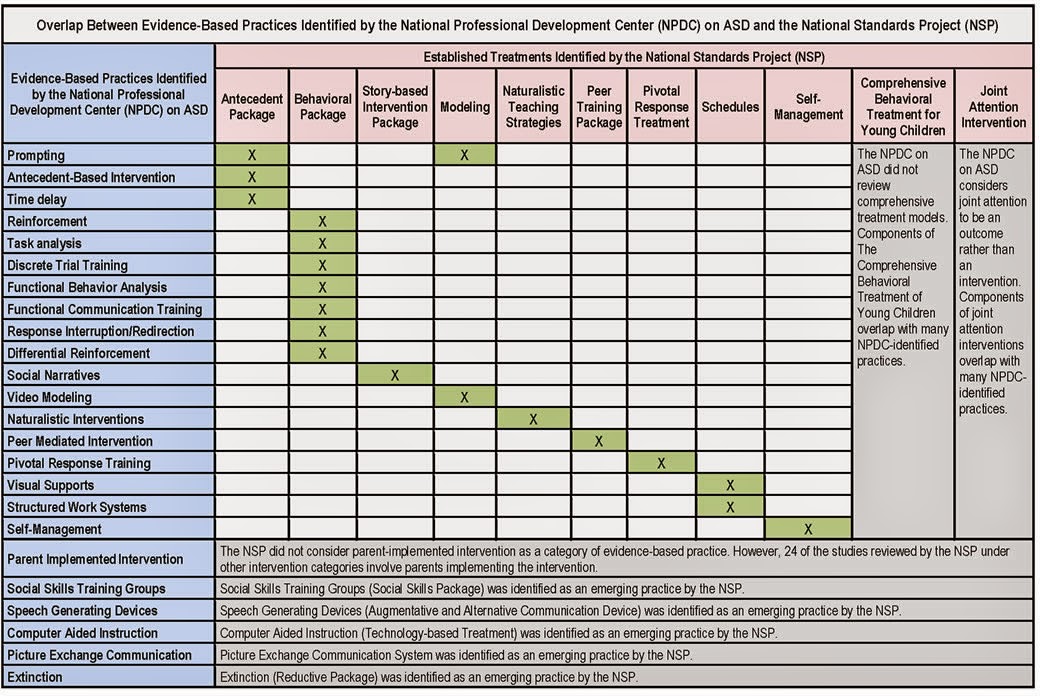

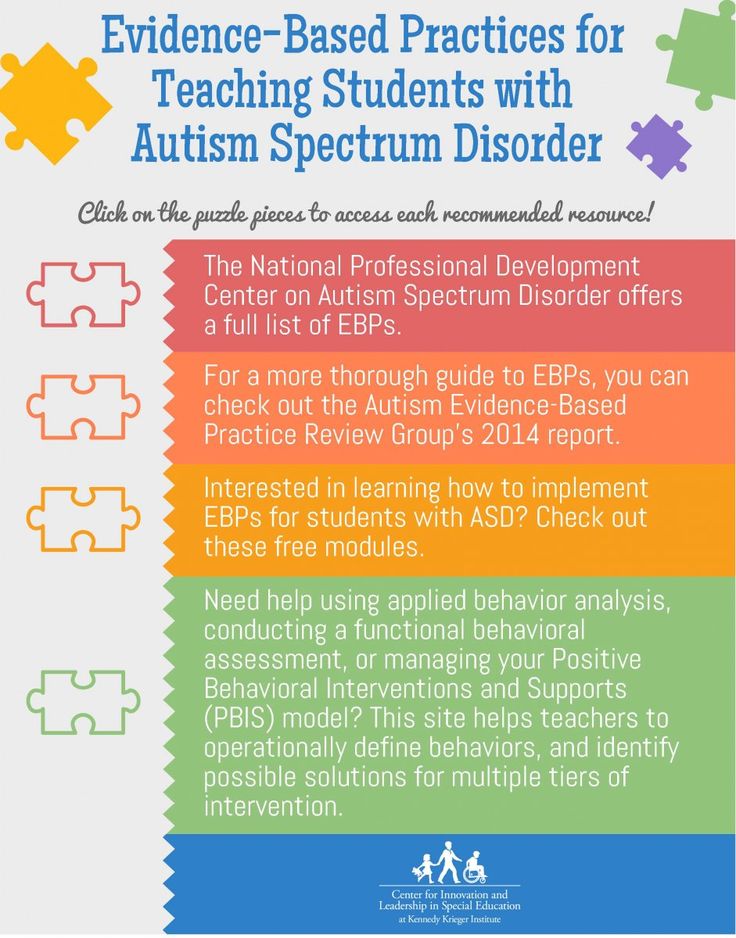

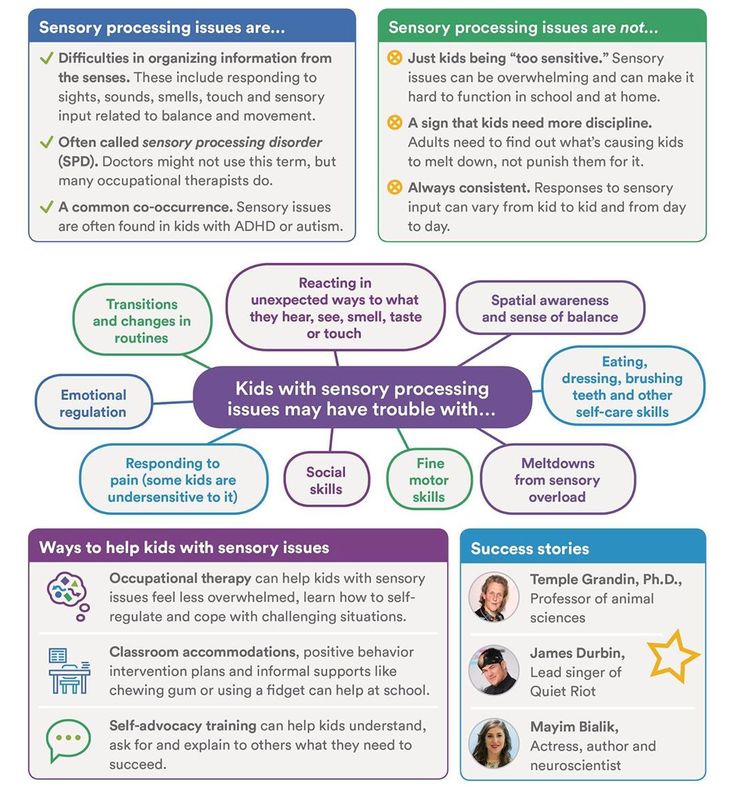

Applied behavior analytic intervention strategies are used to treat challenging behaviors that may be displayed by individuals on the autism spectrum. Behavior analysts typically start by assessing these challenging behaviors. The information collected during an Antecedent-Behavior-Consequence (ABC) assessment is integrated in applied behavior analytic intervention strategies. Once an intervention protocol is designed, targeted and consistent treatment can be implemented. Early intervention is key to successfully reducing such behavior problems.

Applied Behavior Analytic Intervention to Treat Individuals with AutismThe primary concern of behavior intervention strategies for students on the autism spectrum is to individualize the program to the education and behavior goals of the student. The process begins with a detailed assessment of the student’s abilities, interests, preferences, and family situation. Goals are based on the student’s age and level of ability.

Goals are based on the student’s age and level of ability.

- Communication and language

- Social skills

- Self-care (e.g., hygiene, independent living skills)

- Play and recreation

- Motor skills

- Learning and academic skills

Each skill is reduced to small, specific steps that the analyst teaches one at a time using various techniques. The analyst tracks the student’s progress and communicates with the family and other program team members.

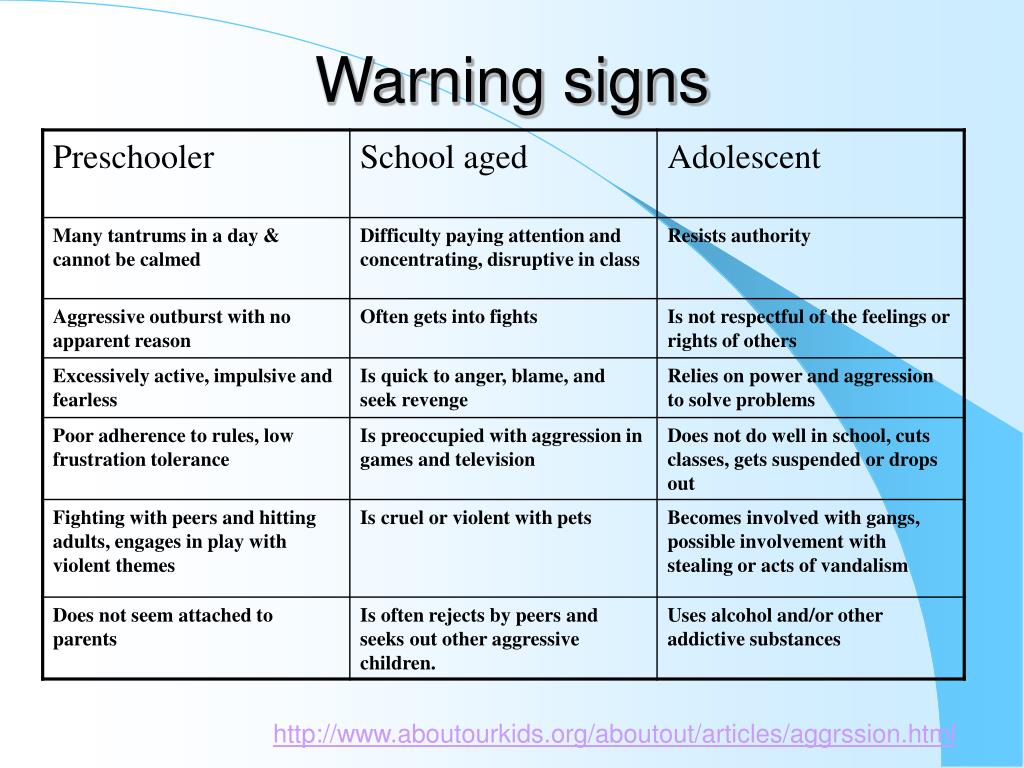

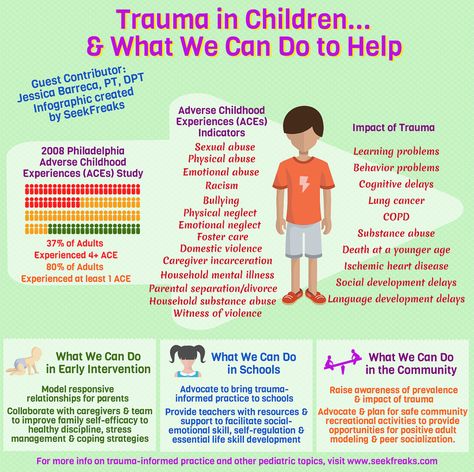

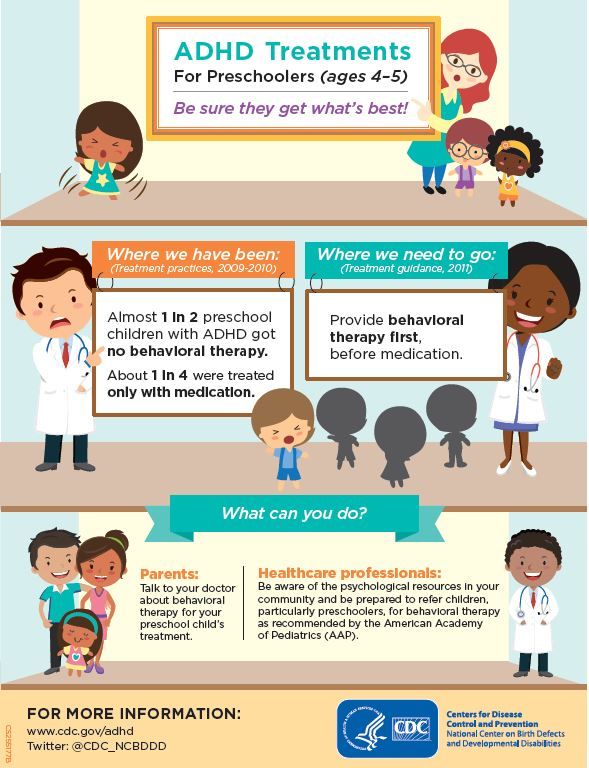

The Importance of Early Intervention to Address Disruptive BehaviorsThe U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) highlights the importance of early intervention to address disruptive behaviors in all children, including neurotypical children and children with ASD. The agency cites studies that link disruptive behavior disorders present in all children to a higher risk of such long-term problems as mental disorders, violence, and delinquency.

The most effective treatment approaches are group parent behavior therapy and individual parent behavior therapy with the child’s participation.

Certain situations increase the likelihood of a child exhibiting disruptive behaviors. Applied behavior analysts, teachers, and parents can prevent and minimize such behaviors by anticipating the times, occasions, and activities that are most likely to precede disruptive behaviors. Similarly, by identifying children who are most likely to have small or occasional behavior problems become more serious, intervention teams can steer the children away from negative behaviors and toward positive alternatives.

Educators and analysts can help parents spot the signs of behavior problems in their children by encouraging parents to perceive situations from the child’s perspective. This helps parents prepare children for future situations and activities that the children may struggle with.

- Parents are encouraged to teach children many different words they can use to express their emotions and feelings.

- Parents help children develop problem-solving skills, so they can imagine alternative solutions when problems arise.

- Parents are instructed to use if-then statements to help children learn to wait patiently for their favorite activities.

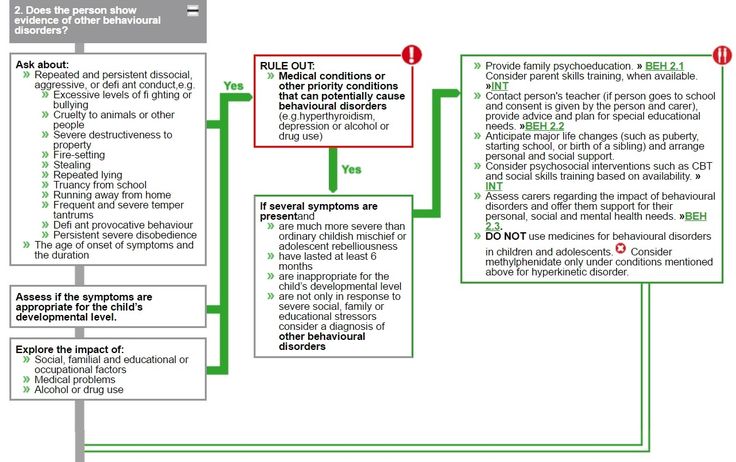

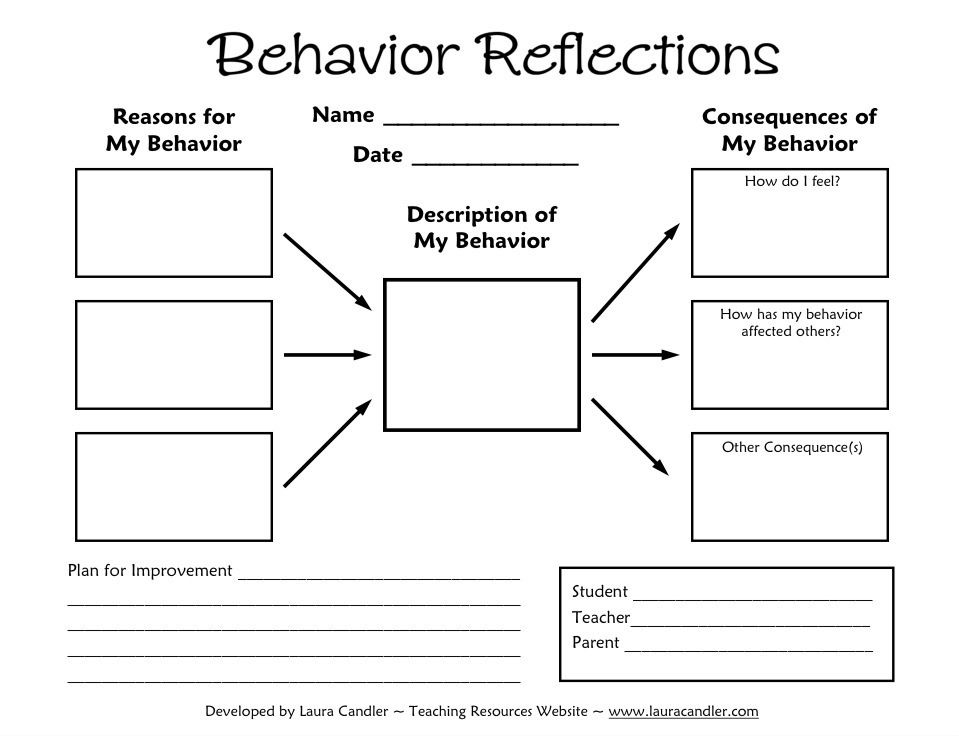

An ABC assessment is used to help intervention teams understand why certain behaviors occur and which consequences are likely to affect whether the behaviors will be repeated.

- An antecedent occurs immediately before the disruptive behavior.

- The behavior that results is the child’s response or lack of response, whether verbal, an action, or other form.

- A consequence occurs immediately after the behavior, whether positive reinforcement of a desired behavior or no reaction to incorrect or inappropriate behaviors.

Children have abundant opportunities throughout the day to learn and practice skills that promote positive behaviors. Parents, family members, and caregivers are trained to support learning and skills practice whenever the opportunity arises. The intervention plan emphasizes positive social interactions and enjoyable learning.

The intervention plan emphasizes positive social interactions and enjoyable learning.

The work of applied behavior analysts helps educators, families, and communities ensure that all children receive the assistance they need to achieve their academic and social goals. Programs such as Regis College’s online Master of Science in Applied Behavior Analysis prepare applied behavior analysts for careers helping children, families, and educators gain maximum benefit from the educational opportunities that are available to them.

Learn more about how the Regis College online Master of Science in Applied Behavior Analysis program helps students pursue their professional goals.

Recommended Readings

How Parents Can Support Children with ASD or Other Behavior Issues While Under Covid-19 Quarantine

What Are Some Examples of Positive Behavior Supports in the Classroom?

What Is a Behavior Intervention Plan, and Why Is It Important in ABA Therapy?

Sources:

Autism Speaks, Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA)

BookWidgets, “Handling Challenging Behavior Problems in the Classroom”

Child Mind Institute, Disruptive Behavior: Why It’s Often Misdiagnosed

Classcraft, “How to Use PBIS Strategies in the Classroom”

Crisis Prevention Institute, “Top 10 Positive Behavior Support (PBIS) Online Resources”

Henry-Stark Counties Special Education District, HSCGED Guidelines for MTSS Implementation for Social/Emotional and Behavioral Concerns

Indiana Department of Education, Positive Behavioral Interventions & Supports (PBIS)

KidsHealth, Individualized Education Programs

National Association for the Education of Young People, “Reducing Challenging Behaviors During Transitions: Strategies for Early Childhood Educators to Share with Parents”

National Center for Biotechnology Information, “Applied Behavior Analysis in Early Childhood Education: An Overview of Policies, Research, Blended Practices, and the Curriculum Framework”

Office of Special Education Programs Technical Assistance Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, 4 Resources to Support Students During the Pandemic

Office of Special Education Programs Technical Assistance Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, Getting Started

Office of Special Education Programs Technical Assistance Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, A Commitment to Racial Equity from the Center on PBIS

Office of Special Education Programs Technical Assistance Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, Tier 1

Office of Special Education Programs Technical Assistance Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, Tier 2

Office of Special Education Programs Technical Assistance Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, Tier 3

Ohio Department of Education, PBIS for Educators

PBIS World, Non-Verbal Cues & Signals

ASERT, Using Applied Behavior Analysis to Educate Students with Autism in Inclusive Environments

Project IDEAL, Developing Classroom Expectations

Social Emotional Workshop, “Personalize Behavior Plans for Student Buy-In”

STAR Autism Support, Applied Behavior Analysis for Your Classroom

TeachHub. com, “Classroom Management: Develop Clear Rules, Expectations”

com, “Classroom Management: Develop Clear Rules, Expectations”

Texas Education Agency, COVID-19: Supporting Challenging Behaviors at Home

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Key Findings: Treatment of Disruptive Behavior Problems — What Works?

U.S. Department of Education, IDEA

U.S. Department of Education, OSERS

Understood, “Positive Behavior Strategies: What You Need to Know”

Vermont-NEA, Behavioral Intervention Guide

WeAreTeachers, “Ways to Encourage Good Behavior, Without Junky Prizes or Sugary Sweets”

Wrightslaw, When Does the IEP Team Have to Develop a Behavior Intervention Plan (BIP)?

Which behavioral therapy is suitable for high skill children?

08.02.18

Applied Analysis of behavior with autism is often associated only with the help of very small and non -speaking children, but this is not true

Author: Tameika Midose / Tameika MEADOS

Source: I Love ABA

What exactly do we call high skill? This is usually an older child, or a young child who is relatively less affected by the diagnosis (for example, has Asperger's syndrome). Usually such children can continue to study in the general education class of the school with some support. If such a child ends up in a correctional class, then most often this is due only to problematic behavior. nine0003

Usually such children can continue to study in the general education class of the school with some support. If such a child ends up in a correctional class, then most often this is due only to problematic behavior. nine0003

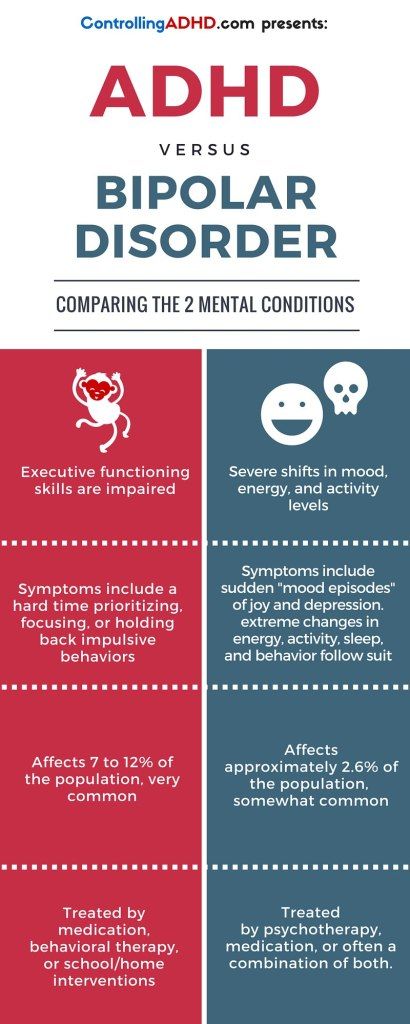

In this case, some skills of the child with autism match the skills of most peers, while others are far behind. For example, such a child may understand all academic material in the general education classroom, but may have serious problems with basic self-care skills. Or the child is fluent in speech and can maintain a dialogue, but he has daily severe tantrums.

As a rule, these children have communication problems only under the influence of strong emotions. This can be confusing and frustrating for parents and educators, as the child, who can usually verbalize his needs, engages in problem behavior when he is very upset. nine0003

These autistic children may be interested in peers, age-appropriate toys, or socializing in general. Unfortunately, very often, despite their desire to communicate, problems with social skills lead to ostracism from their peers.

The level of problem behavior can range from low to very high. This type of ASD is often characterized by "mood swings". It is very easy to work with a child when he is calm. However, the escalation of the emotional state can occur rapidly, and the child will take a long time to completely calm down. nine0003

Aspiring behaviorists may find it difficult to program for such a child once they realize that he is MUCH ahead of the VB-MAPP test and even masters most of the skills on the ABLLS-R test. He does not need to be trained to match identical objects, imitate gross motor movements, or build towers from blocks.

When I meet a student with a high level of skills, very often at the first moment I catch myself thinking: “Oh, why was I called to work with this child?”. This is a student who greets you, speaks himself, shows his toys with pleasure, boasts that he was given an A for his report on natural history. But then… you start to notice something. For example, this child is 9years, but he still sleeps in diapers. Or the child is 13 years old, and her only friend is a 4-year-old neighbor. Or a 22-year-old student who refuses to leave the house without his pink backpack with Dasha the Traveler.

Or the child is 13 years old, and her only friend is a 4-year-old neighbor. Or a 22-year-old student who refuses to leave the house without his pink backpack with Dasha the Traveler.

This is the moment when you realize that although at first glance it may seem that a person has no problems with functioning, in reality he is in dire need of help.

This may sound unfair, but I often see that it is children with high skill levels who are the most irritating to family members and educators. They are expected to have a high level of control over their behavior that they are not capable of. How can they be high functioning in some areas and low functioning in others? nine0003

I often have to explain this to all sorts of specialists. When working in the field of autism, it is important not to set your expectations low for children with low skill levels, and at the same time not to raise your expectations for children with high skill levels. Everything is simple.

I am deeply resented when I come across people who do not expect anything from my students, and this happens very often. But there is also the opposite situation: people believe that since my student with ASD can speak and communicate, then he does not have ANY problems. Both are unfair, fallible, and completely ignore each person's unique strengths and weaknesses. Autism is a spectrum, all you can expect in advance from people with ASD is that they don't look alike. nine0003

But there is also the opposite situation: people believe that since my student with ASD can speak and communicate, then he does not have ANY problems. Both are unfair, fallible, and completely ignore each person's unique strengths and weaknesses. Autism is a spectrum, all you can expect in advance from people with ASD is that they don't look alike. nine0003

I rarely work with older and higher skill levels, and when I get the opportunity it's always a lot of fun.

Your activities may include cooking, working on workplace skills, shopping, science projects, arts and crafts, good manners and etiquette. The sessions themselves with such clients can be very exciting. For example, one student noticed that I dyed my hair and said that now I'm like Ariel from The Little Mermaid. Another girl said that if I didn't stop making her study, she would call the police. And one boy of 7 years old asked me if I like rap, and when I answered “no”, he said: “It's nothing, then you will love it when you become cool. ” nine0003

” nine0003

The following are some guidelines for designing a behavioral program and typical (but not universal) goals for teaching these children.

Please note that these guidelines do not apply to where you work with your child. In other words, they will need to be adapted to work at home, at school, in the workplace, or in an applied behavior analysis center. Changing the place does not change the need for all children to be successful.

General recommendations for intervention

Recommended ratio of teachers and students: frontal instruction of one teacher (for aggression and other problematic behavior, an individual tutor may be required).

Format and methods of work

— For the most part, learning in a natural environment.

- Random learning method.

- Education in public places. (See also "What is learning in public places").

Recommended therapy intensity

- 8-15 hours per week.

Reinforcement mode

- Variable mode or fixed time interval, eg 25:1 (one break every 25 minutes).

Types of rewards

- Natural reward (we baked a cake and then we eat it), which is given quite rarely.

- Token economy systems. (Also see How to Reward Your Child with Tokens.)

Behavior program goals

- Visiting public places.

- Intraverbal speech skills.

- Role-playing game.

- Hygiene skills.

- Global reading.

- Reading comprehension.

- Fluency in math skills.

- How to follow the rules of the game and accept defeat in the game.

— How to accept change and change.

- Conflict resolution skills.

- Teaching social skills through social stories. (See also How to teach children with autism with social stories.) nine0003

- Housework and household help.

- Cooking.

Important things to watch out for

- Risk of over-prompting/learned prompt responses. (This is why the block-by-block approach is not recommended for such students.)

(This is why the block-by-block approach is not recommended for such students.)

- Child may show interest in therapy progress and your notes.

- "Splintered" training profile: some skills are much above average, other skills are much lower.

- Teaching should include rewards provided by both adults and peers, and the development of self-rewarding skills. nine0003

- Be sure to include training in the skills of assessing and managing your behavior in the program. (Also see How Managing Your Own Behavior Can Help Autism.)

- For older clients, it may be necessary to train all employees in the safe physical response to violent behavior.

— It is important to work on developing age-appropriate play and leisure skills and interests (to facilitate peer relationships). nine0003

See also:

Why is it so hard to live with "high functioning" autism

What is Asperger's syndrome and high functioning autism

How to choose the goals of therapy for autism with parents

We hope that the information on our website will be useful or interesting for you . You can support people with autism in Russia and contribute to the work of the Foundation by clicking on the "Help" button.

You can support people with autism in Russia and contribute to the work of the Foundation by clicking on the "Help" button.

ABA Therapy and Behavior, Methods and Treatment, Education and Training, Asperger Syndrome

Therapeutic interventions

How to select and evaluate therapies for children with autism spectrum disorders.

Autism is a complex developmental disorder characterized by significant impairments in social interaction and communication, as well as repetitive behaviors and specific, obsessive interests. Given the heterogeneous nature of autism, a number of therapies claim to be exceptionally effective in dealing with this disorder. Here is just a short list of techniques popular with parents and professionals who work with children with ASD: applied behavior analysis (ABA), sensory integration, special diets (gluten-free, casein-free, etc.), pharmacological treatment, chelation (removal from the body mercury), etc. However, all these techniques, with rare exceptions, are practiced in the absence of scientific data confirming their unambiguous effectiveness. In an effort to choose the best method of therapeutic intervention for their ward, relatives and friends of people with ASD are faced with a huge layer of conflicting information. The fact that in the selection process in most cases it is not possible to rely on exact figures and facts is a serious problem. nine0003

In an effort to choose the best method of therapeutic intervention for their ward, relatives and friends of people with ASD are faced with a huge layer of conflicting information. The fact that in the selection process in most cases it is not possible to rely on exact figures and facts is a serious problem. nine0003

Most experts agree that the optimal start of therapy for a child with autism spectrum disorder is an intensive, coordinated program of special education and behavioral intervention. Behavioral intervention programs typically include a block of language and speech comprehension exercises, communication and social skills development advice, and an additional program to address unwanted behaviors. Applied behavior analysis-based training and intervention programs are considered to have the strongest evidence base for their effectiveness. In addition, at 19In 1999, the US Secretary of Health spoke out in support of the ABA. The method has also been approved by the National Institutes of Health.

All other currently existing types of autism therapy can be divided into two groups. One includes various types of special diets, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, various types of vitamin therapy and psychotropic drugs. With the exception of studies on the efficacy of some psychotropic drugs, all of these therapeutic interventions lack a solid scientific evidence base. With regard to drug intervention, a number of studies have shown that certain medications can reduce some of the unwanted behaviors that are common in people with ASD (eg, violent outbursts). The second group includes sensory integration therapy (SI), “supported” communication (a child or an adult writes or types when his hand is held by an “assistant”) and craniosacral therapy. nine0003

Although starting behavioral therapy can be a great start, this does not preclude the use of other, alternative, methods, if they are aimed at specific goals, in the process there is a constant collection of data and evaluation of their effectiveness, and of course, if these techniques are applied with care and attention to the client's condition. Refusal of other types of intervention without understanding and evaluating its potential effectiveness is not appropriate for a number of reasons. The absence of arguments “for” does not mean that one should unambiguously speak out “against”. The problem is that new techniques typically cannot back up claims of effectiveness with sufficient research data. Further complicating matters is the fact that scientific journals generally do not publish reports of studies with negative results. In other words, research results that do not confirm the effectiveness of any method may never appear in scientific journals, since such publications usually prefer to write about successes. In addition, the situation is complicated by the fact that different people with autism spectrum disorders respond differently to different types of therapy. As we have already said, autism is a complex developmental disorder caused by a whole range of different causes that certainly affect how a person responds to various types of intervention.

Refusal of other types of intervention without understanding and evaluating its potential effectiveness is not appropriate for a number of reasons. The absence of arguments “for” does not mean that one should unambiguously speak out “against”. The problem is that new techniques typically cannot back up claims of effectiveness with sufficient research data. Further complicating matters is the fact that scientific journals generally do not publish reports of studies with negative results. In other words, research results that do not confirm the effectiveness of any method may never appear in scientific journals, since such publications usually prefer to write about successes. In addition, the situation is complicated by the fact that different people with autism spectrum disorders respond differently to different types of therapy. As we have already said, autism is a complex developmental disorder caused by a whole range of different causes that certainly affect how a person responds to various types of intervention. Some techniques may be effective for one child, and completely unsuitable for another. In the selection process, it is very important to objectively assess how exactly this therapy is needed for your child. Instead of immediately abandoning any alternative methods, it is better to approach the problem in a complex way: study all the available information about the new method, and refuse only those points that will not be effective when working with your child. Unfortunately, information about alternative methods is often presented in an unsystematic manner, which does not allow them to be objectively evaluated. nine0003

Some techniques may be effective for one child, and completely unsuitable for another. In the selection process, it is very important to objectively assess how exactly this therapy is needed for your child. Instead of immediately abandoning any alternative methods, it is better to approach the problem in a complex way: study all the available information about the new method, and refuse only those points that will not be effective when working with your child. Unfortunately, information about alternative methods is often presented in an unsystematic manner, which does not allow them to be objectively evaluated. nine0003

In the near future, discussions about alternative types of therapeutic intervention will be an indispensable element of the information space, so it is very important that those who in one way or another come into contact with people with ASD have the opportunity to receive comprehensive information about the possible types of services for this category of citizens . It is important to be able to critically evaluate the effectiveness of proposed interventions, read specialized literature and scientific articles (rather than someone else's unverified evidence and impressions) and learn to critically evaluate the potential benefits, possible risks, as well as the adequacy of the financial and time costs that the chosen type will require. therapeutic intervention. While the idea of “trying everything” seems very appealing, remember that by dabbling in various therapies with dubious effectiveness, you are wasting your child’s main resource - time, and preventing him from reaching his full potential. nine0003

It is important to be able to critically evaluate the effectiveness of proposed interventions, read specialized literature and scientific articles (rather than someone else's unverified evidence and impressions) and learn to critically evaluate the potential benefits, possible risks, as well as the adequacy of the financial and time costs that the chosen type will require. therapeutic intervention. While the idea of “trying everything” seems very appealing, remember that by dabbling in various therapies with dubious effectiveness, you are wasting your child’s main resource - time, and preventing him from reaching his full potential. nine0003

In addition to comprehensively exploring alternative therapeutic interventions, loved ones of people with autism and practitioners should continually evaluate the effectiveness of therapy in the process. Neglecting the need to collect data and analyze the information received often prevents a correct idea of the appropriateness of the use of a particular therapy, while in the field of applied behavior analysis there are simple and understandable procedures that allow one to evaluate both the potential effectiveness of the therapy as a whole and the effectiveness of the chosen method of influence. The use of outcome measures used by behavioral analysts is also valid for alternative therapies, which allows for a more or less accurate assessment of its effectiveness. Thus, practitioners, as well as relatives and friends of people with autism, get the opportunity to use only those techniques and techniques that will benefit him in working with a child. In addition, these measures can be used to understand how well the skills and abilities acquired during therapy are generalized for different conditions, and to monitor possible side effects. nine0003

The use of outcome measures used by behavioral analysts is also valid for alternative therapies, which allows for a more or less accurate assessment of its effectiveness. Thus, practitioners, as well as relatives and friends of people with autism, get the opportunity to use only those techniques and techniques that will benefit him in working with a child. In addition, these measures can be used to understand how well the skills and abilities acquired during therapy are generalized for different conditions, and to monitor possible side effects. nine0003

There are a wide variety of therapies for people with autism spectrum disorder, some based on applied behavior analysis, some not. The effectiveness of behavioral therapy and some types of medical interventions has been confirmed by studies, while other types of therapy are not yet sufficiently studied to judge them unambiguously. Unfortunately, some types of ineffective, and even harmful interventions still find their supporters, because they promise magical healing and do not require significant efforts from parents and specialists.