Headache after emdr

EMDR Guidance | DRASACS

This page is to give support in between sessions with your therapist, feel free to discuss accessing this page with your therapist in your next appointment

This information has been sourced from davidblore.co.uk and is designed to be used in addition to the work carried out with your therapist.

EMDR DEBRIEFING SHEET EMDR supervision handout 8.15 © David Blore 2011

Debriefing advice: After your EMDR treatment sessions

Please note carefully: The material below is in addition to advice supplied by your therapist in your specific case. Therefore the material below is not comprehensive nor is it exhaustive. If you have any doubt about what to do, contact your therapist promptly on 01302 360421 (Mon – Fri 10am – 4pm) or Helpline (01302 32855) Tue 9:30 – 10:30 Thur 12:00 – 13:00

The first half hour or so after an EMDR treatment session:

EMDR is not like other therapies. Treatment generates a certain amount of ‘momentum’ to your thinking and conscious awareness. In other words treatment doesn’t just stop immediately on leaving the session. You will have already been reminded of this when your therapist suggested allowing an extra half an hour at least after an EMDR treatment session. It is best if you aim to ‘waste’ this half an hour. Actually it isn’t being wasted at all. It is time to yourself to allow you to reference your awareness back in the present.

It’s strongly advised that you do not drive during this period as you may find your concentration wanders off easily. Do not put yourself in unnecessary danger. Clients have reported being glad they were more aware than usual when merely crossing the road. Don’t run to catch a bus or train either. The best way of spending the half hour is to reference yourself properly in the ‘present’ such as being mindful of what you are doing minute by minute. This can be achieved by being mindful of reading a book or magazine, talking to a friend, walking around the shops or watching what is going on around you such as observing some particular activity: how someone is walking, the effect of wind in the trees or birds coming and going, or listening to sounds. Other helpful things are to do a relaxing activity such as drinking a tea or coffee, going window-shopping or relaxing in a local park and so on.

Other helpful things are to do a relaxing activity such as drinking a tea or coffee, going window-shopping or relaxing in a local park and so on.

Things that may (or may not) happen in the days that follow:

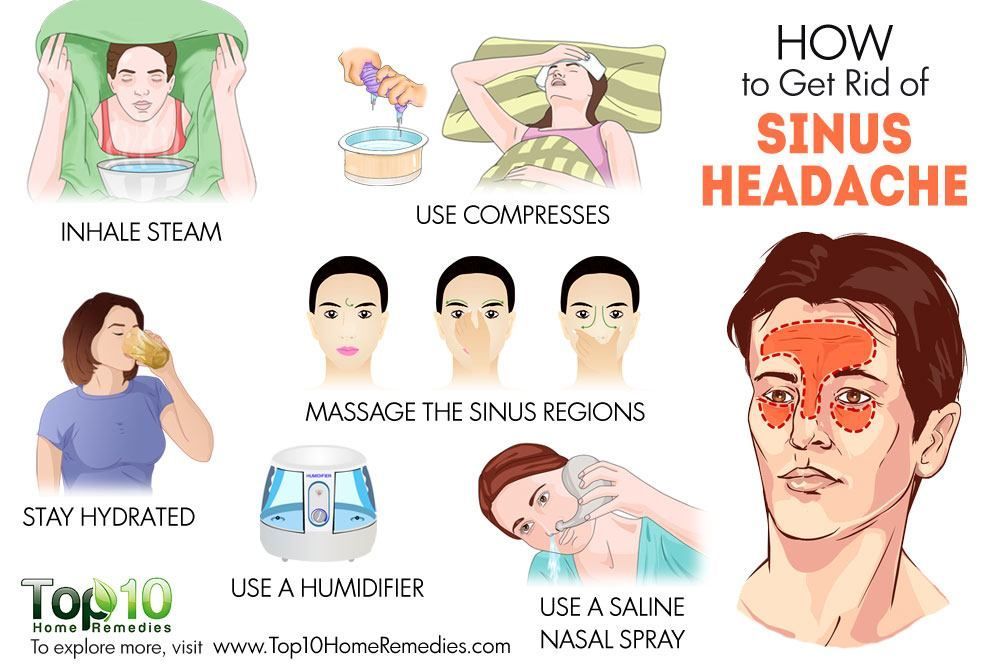

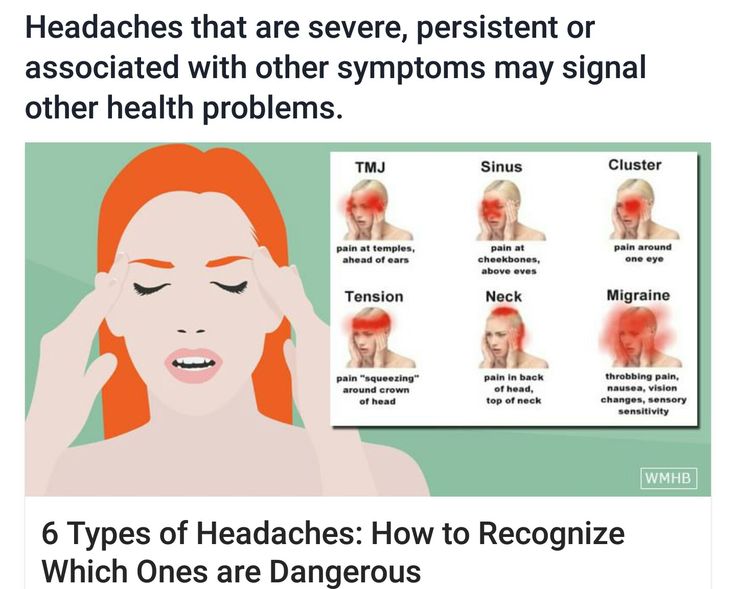

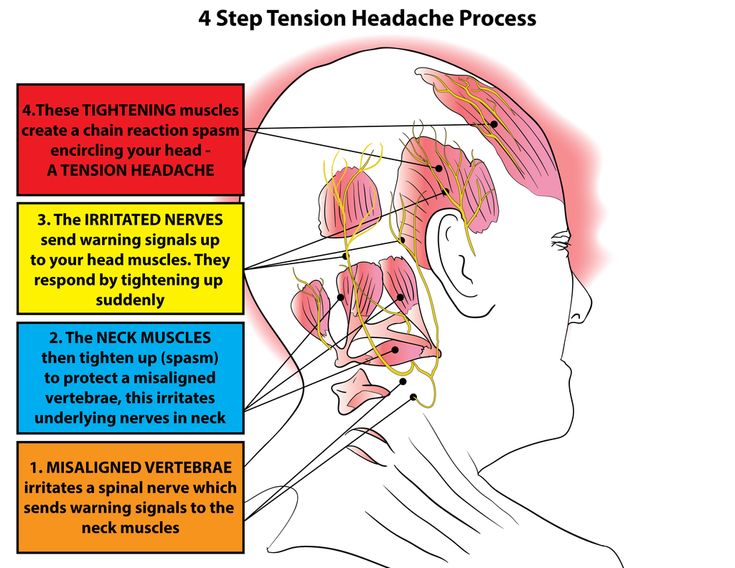

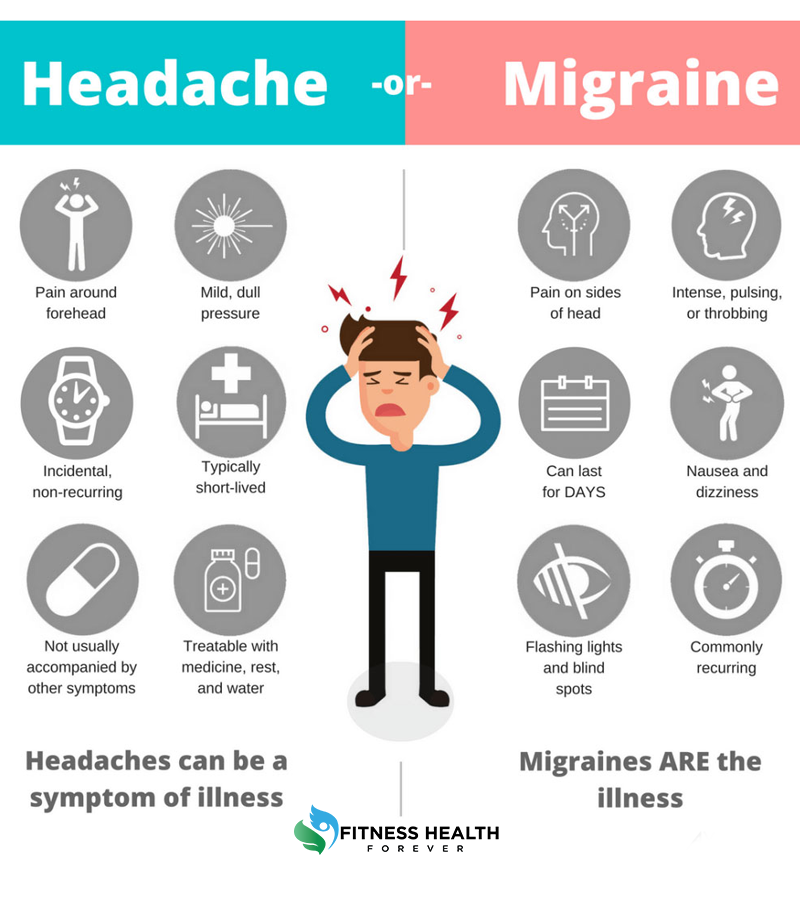

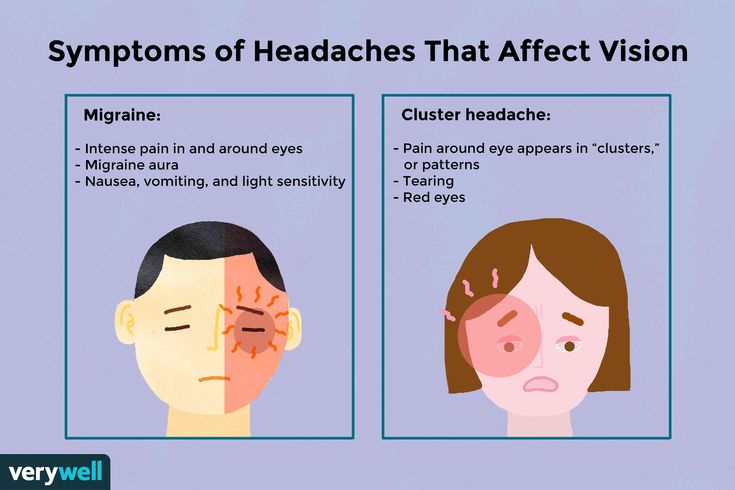

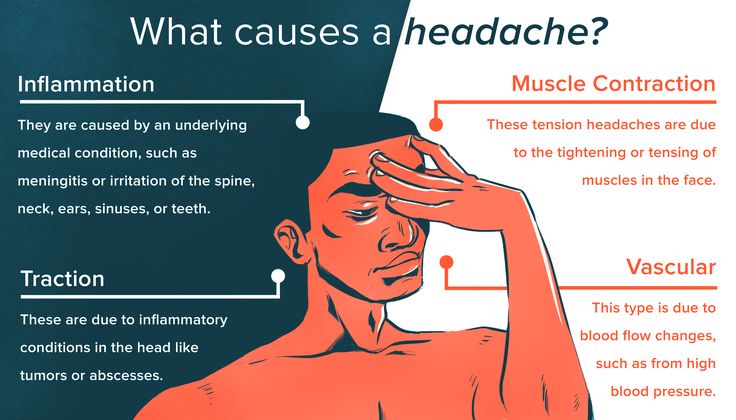

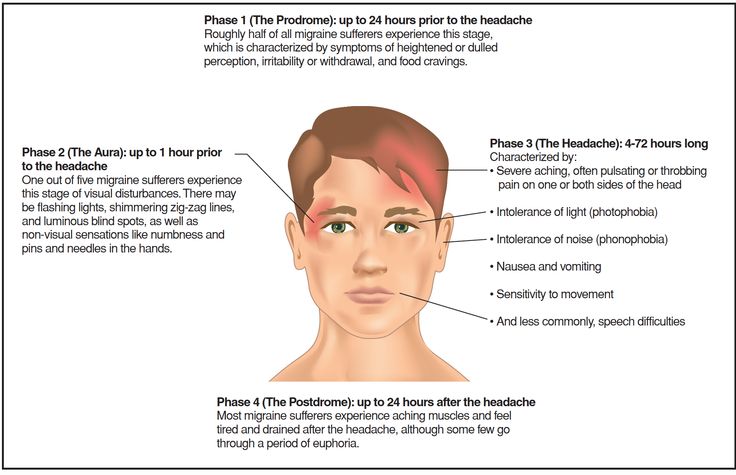

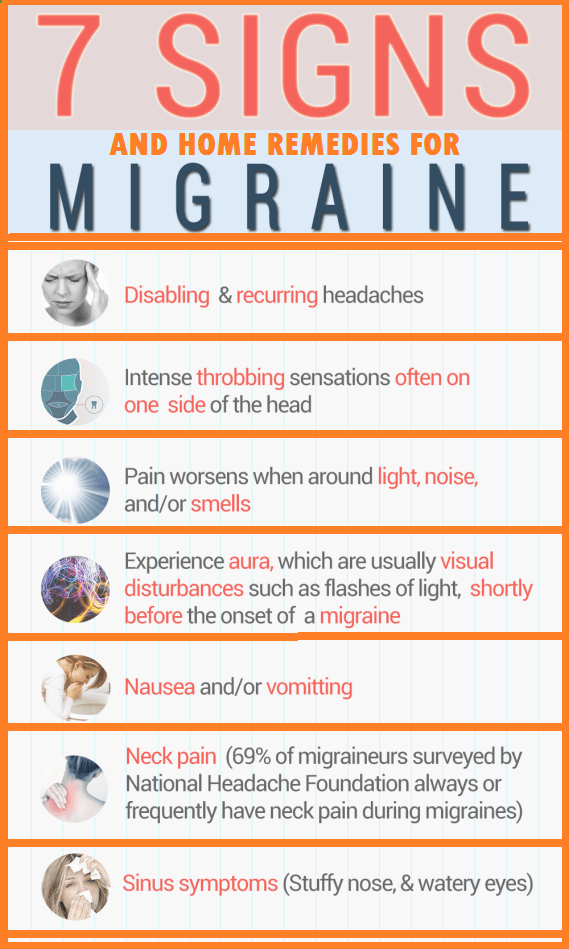

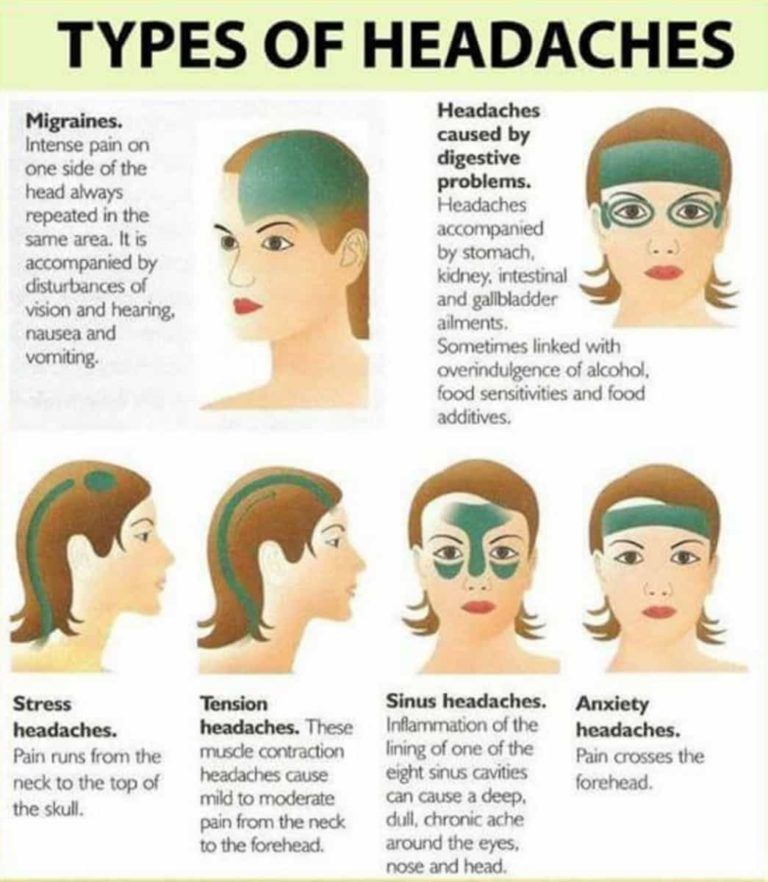

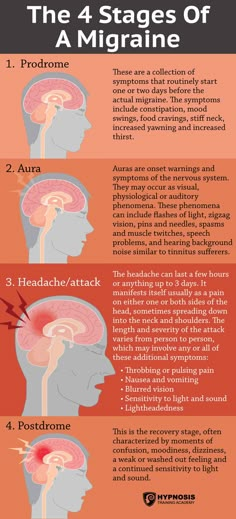

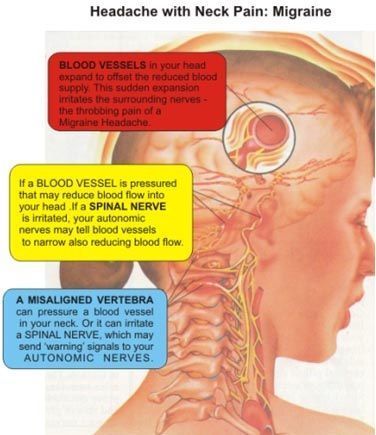

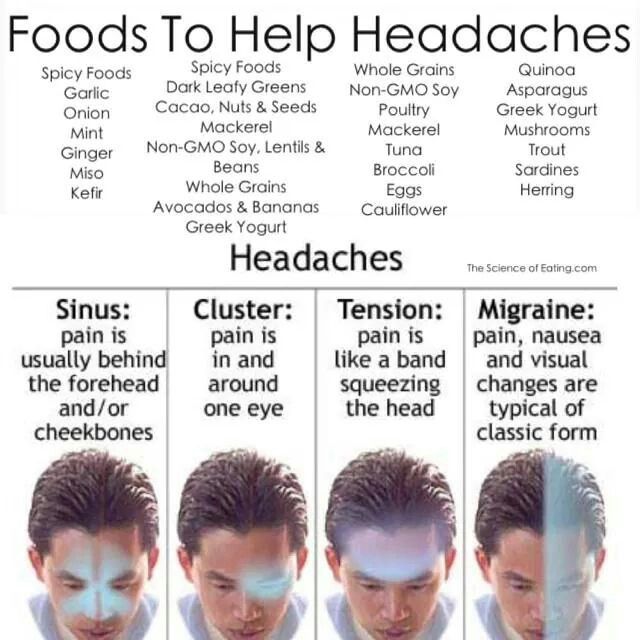

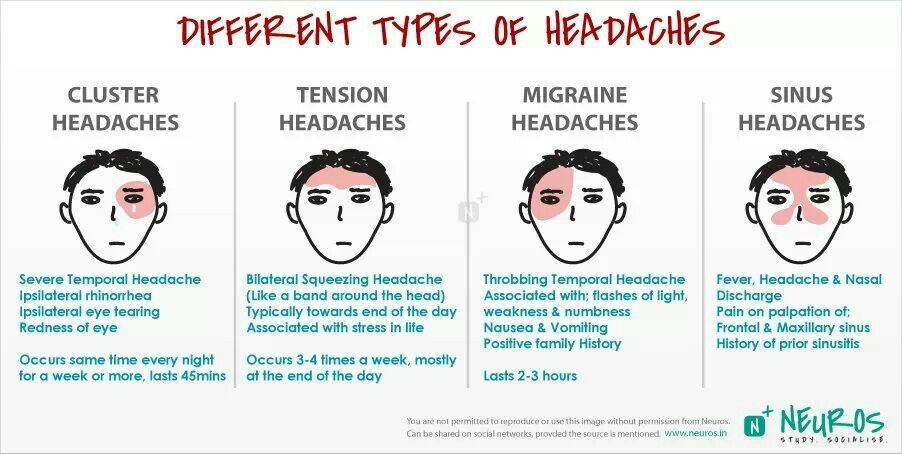

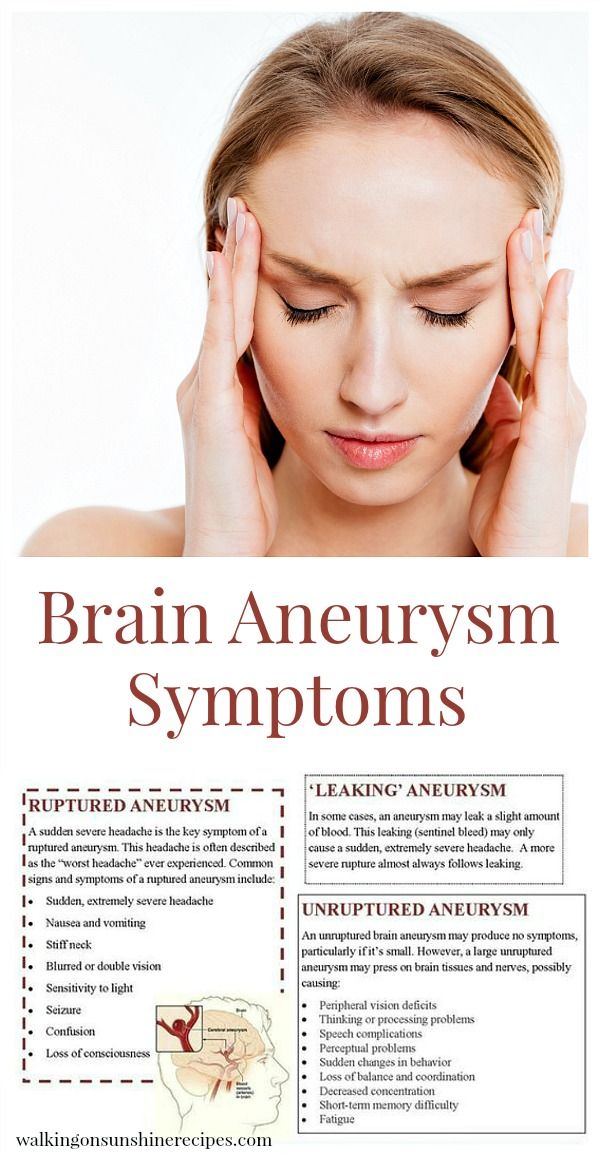

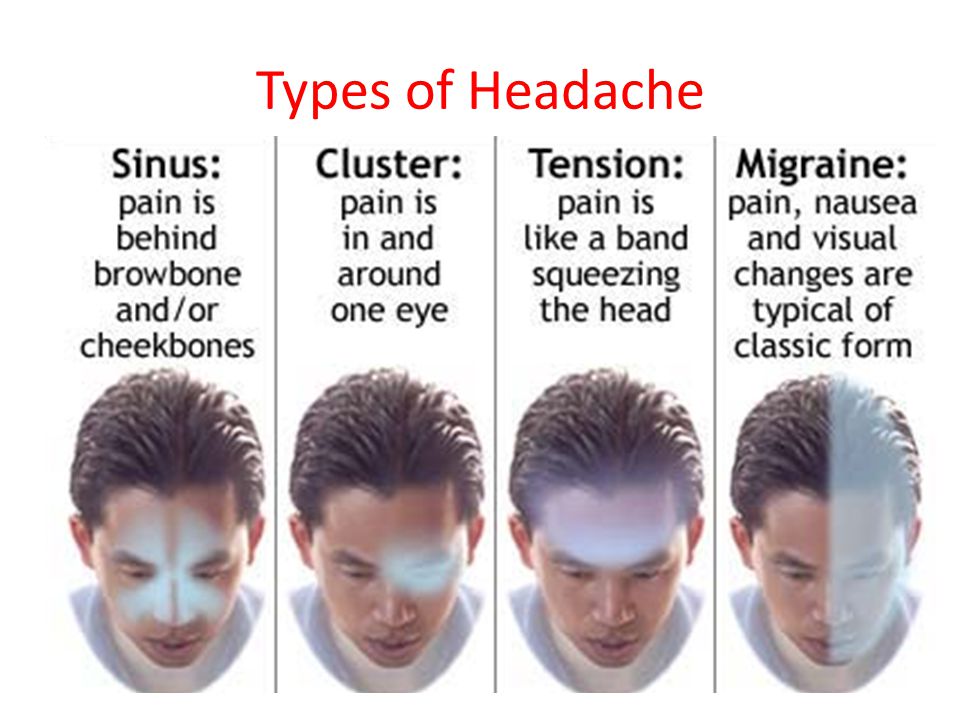

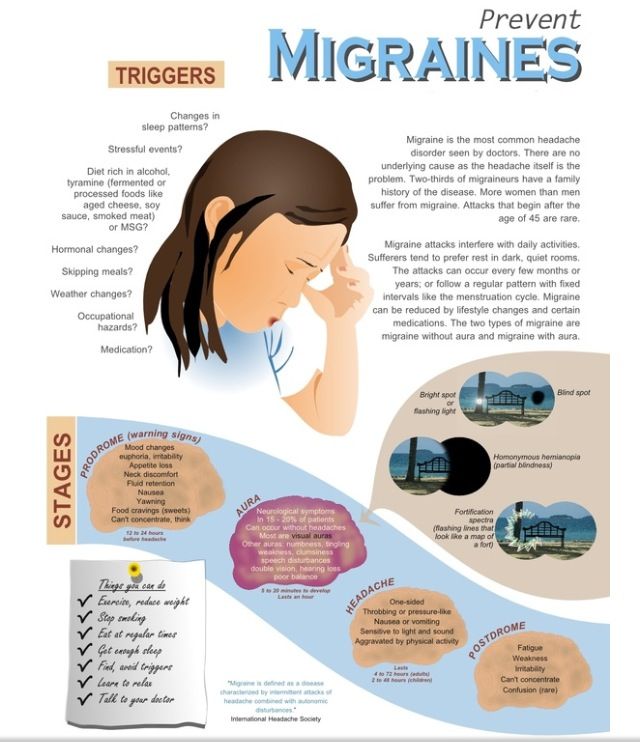

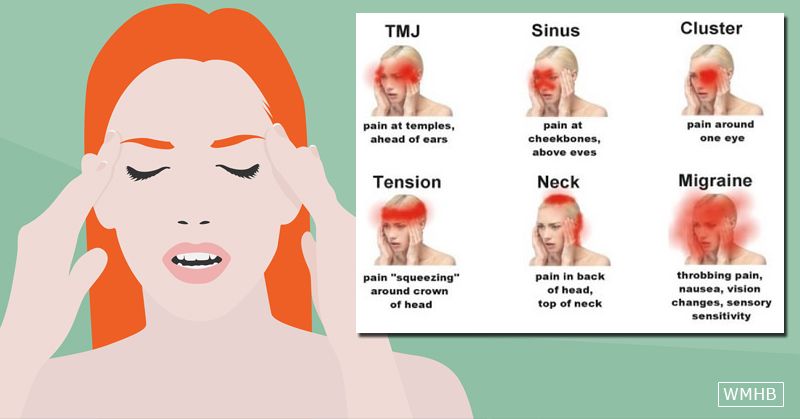

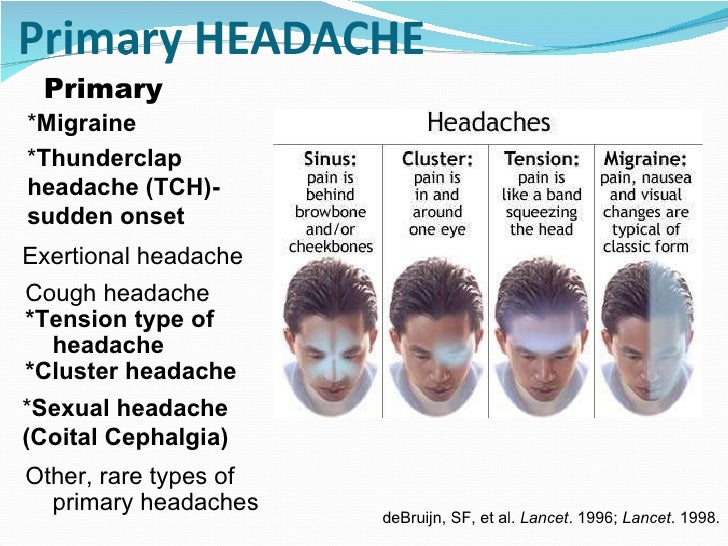

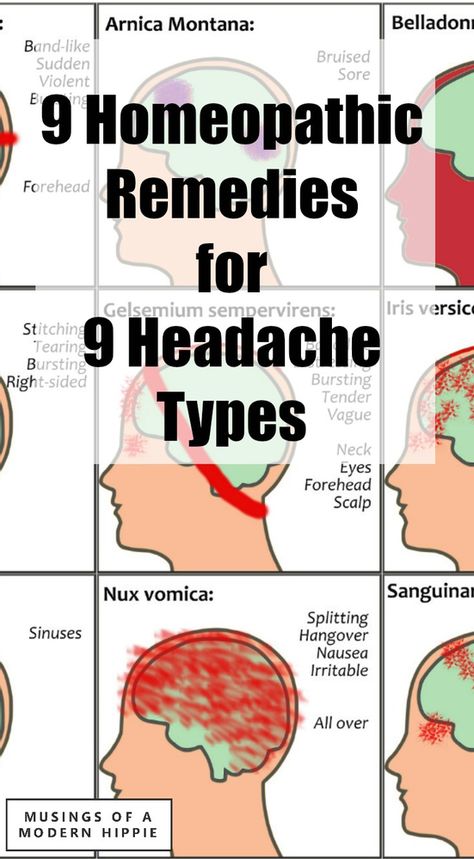

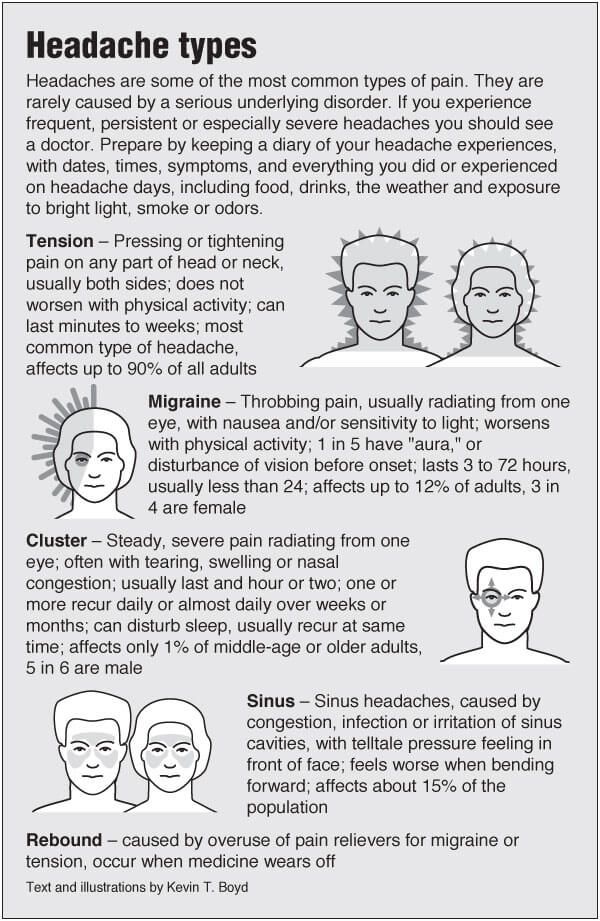

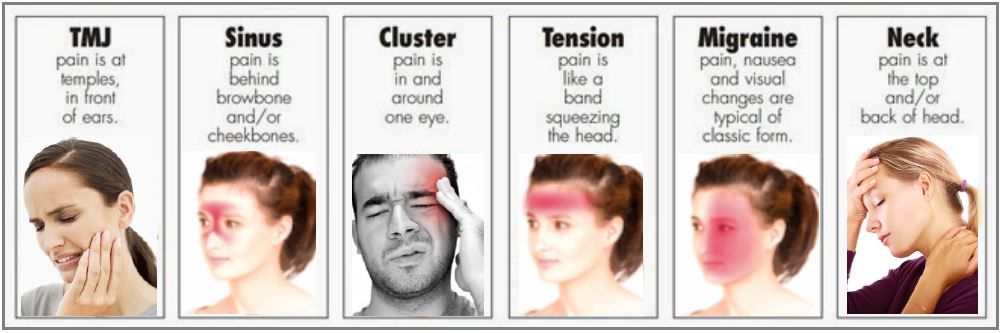

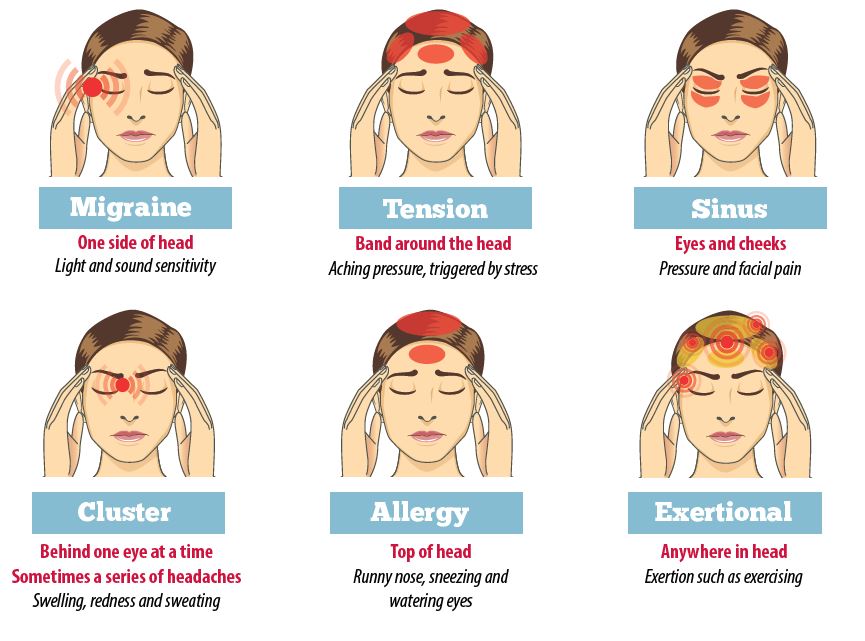

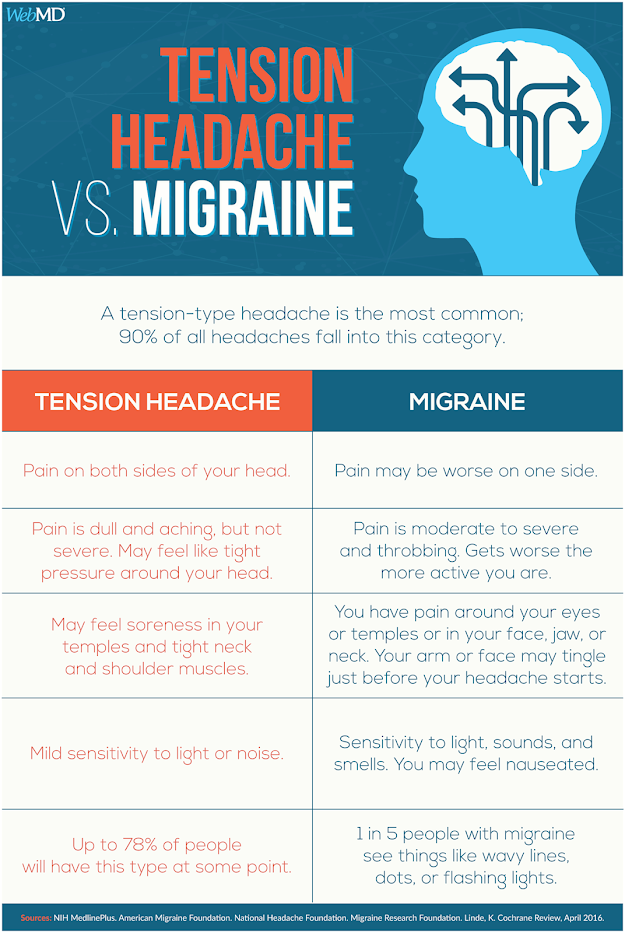

You may just experience a headache after the session; this is most likely to be down to not being sufficiently relaxed during the session itself. Remember muscles move eyes and muscles tire easily – you may have used your eyes more than you are used to!

The answer to headaches: the simple answer is ‘prevention’. This means making use of any relaxation exercises your therapist has taught you, particularly your ‘safe/ calm or peaceful place image, but don’t forget skills you may already have such interests such as yoga, meditation, t’ai chi etc. Actually headaches are not as common as reports of increased dreaming after EMDR. This is nothing to worry about. If you recall the dreams it is likely that they won’t make much sense, with reports frequently saying that dreams “seemed chopped up into pieces”, but there seems little doubt that the frequency of dreaming goes up initially with reports such as “I dreamt from the moment I put my head on the pillow until the next morning”. Other clients report no increased dreaming, indeed sometimes no dreaming at all. Again don’t worry this doesn’t mean the EMDR is not working.

Other clients report no increased dreaming, indeed sometimes no dreaming at all. Again don’t worry this doesn’t mean the EMDR is not working.

You may well become aware of new insights about what is being treated, this is a direct indication that processing is continuing between sessions. Similarly, emotionality can be regarded as important ‘signposts’ for your therapist, so try to keep a record of what is happening, as trying to recall what happened, when it happened, and in what order, can be very difficult at a session a week or more later. In the meanwhile make your partner or significant other aware of your need for support. If you are still worried do not hesitate to contact the following number: 01302 360421 (Mon – Fri 10am – 4pm) or Helpline (01302 32855) Tue 9:30 – 10:30 Thur 12:00 – 13:00

What Are The Dangers Of EMDR Therapy?

Share This Post With Your Friends and Loved Ones

Table of Contents

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy is a relatively new treatment that has grown in popularity over the past few years. But what is it? How does it work? And are there any dangers of EMDR therapy?

But what is it? How does it work? And are there any dangers of EMDR therapy?

In this blog post, we will explore these questions and more. We will take a look at how EMDR therapy works and who can benefit from it. We will also dispel some common misconceptions about EMDR therapy and talk about why people might think it is dangerous. If you are considering EMDR therapy, read on to see if this treatment option is right for you.

What is EMDR Therapy?

EMDR therapy is a type of treatment that helps people process and heal from past trauma. It was first developed in the 1980s by Dr. Francine Shapiro and has since been used to help millions of people around the world.

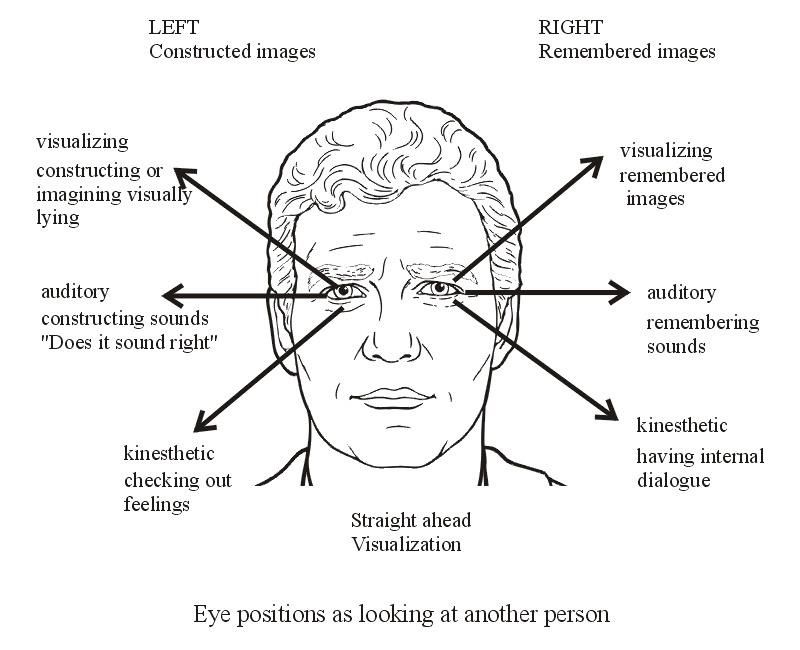

EMDR therapy is usually done with a trained therapist who will guide you through the process. During EMDR therapy, you will be asked to think about the traumatic event or memory while moving your eyes back and forth. Eye movement is stimulated by either holding a device in each hand that sends rhythmic vibrations or by the therapist waving their fingers back and forth in front of you.

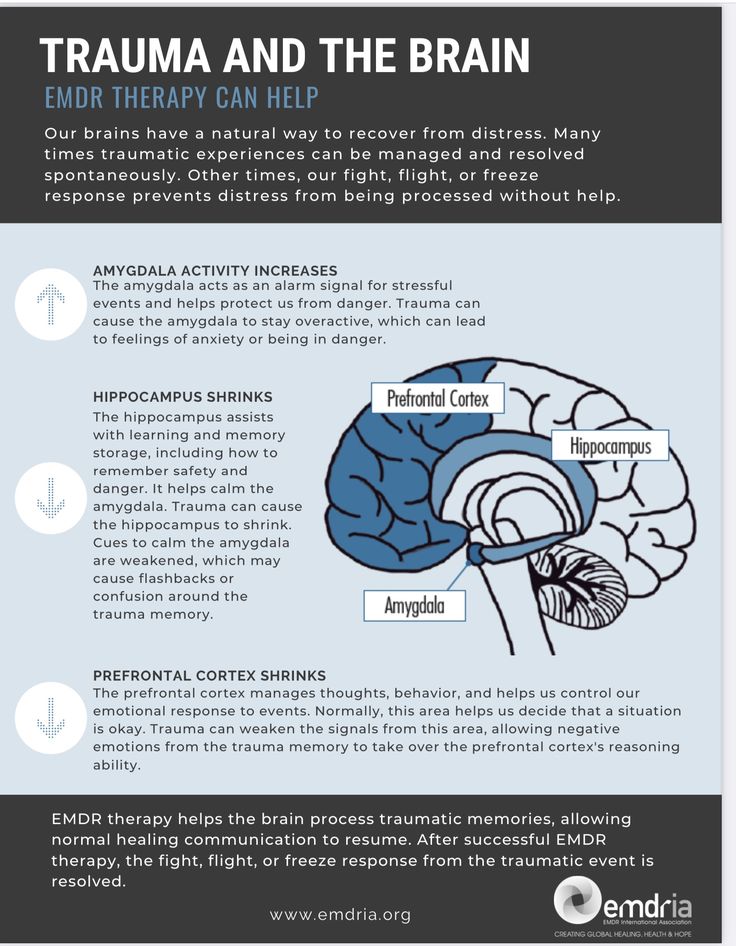

EMDR therapy is based on the belief that our brains are naturally able to heal from trauma, just like our bodies do. When we experience a traumatic event, it can be difficult for our brains to process what happened. This can lead to us feeling stuck or like we’re reliving the trauma over and over again.

EMDR therapy is thought to help “unstick” the stuck memories so our brains can process them and heal.

Research has shown that this eye movement can help process the trauma and reduce its negative emotions.

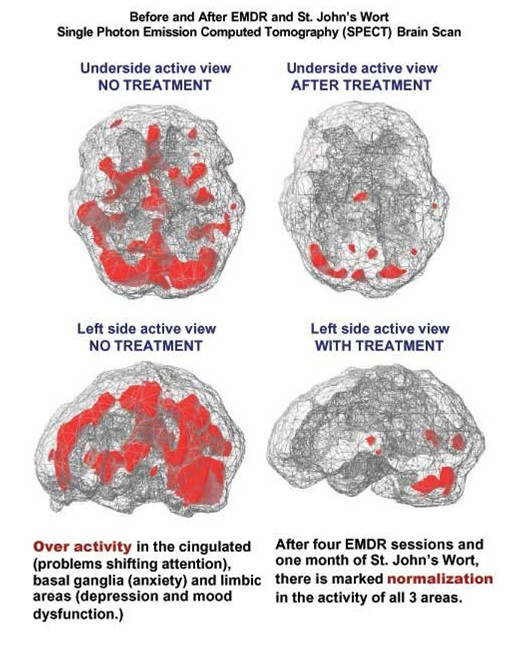

EMDR therapy has been proven to be an effective treatment for PTSD. It can also be helpful for other mental health issues such as anxiety and depression.

What Are the Side Effects of EMDR Therapy?

Just like with any form of effective therapy, there can be some side effects of EMDR therapy. These side effects are usually mild and temporary, but understanding them can help you to be prepared for what to expect.

Feeling overwhelmed or emotional.

As we mentioned before, EMDR therapy can help to process stuck memories. This means you may feel overwhelmed or emotional as the memories return to you. However, your therapist will be there to help you through this and will provide support.

Headaches or fatigue.You may also experience headaches or fatigue after EMDR therapy sessions. Again, these side effects are usually mild and will go away on their own. If they persist, be sure to talk to your therapist.

Physical reactions.Some people may also experience physical reactions such as sweating, shaking, crying, muscle tension, or an increased heart rate. These are all normal reactions to trauma and will subside.

Having trouble sleeping.It’s also common to have trouble sleeping after EMDR therapy. This is because the memories that are being processed can be emotionally intense. Your therapist will likely give you tips on managing this side effect.

EMDR therapy may also bring up new memories or feelings you were not expecting. This is normal and to be expected. Your therapist will help you process these new memories and emotions in a safe and supportive environment.

Are There Any Dangers of EMDR Therapy?

Now that we’ve covered some potential side effects of EMDR therapy let’s dispel some common misconceptions about this treatment.

EMDR therapy is dangerous.One of the most common misconceptions about EMDR therapy is that it is dangerous. This is because people mistakenly believe that the eye movement will cause them to relive the trauma. However, this is not the case! The eye movement is simply a way to help your brain process the trauma. Therefore, you will not relive the trauma during EMDR therapy.

It will make you feel worse.Another common misconception about EMDR therapy is that it will make you feel worse before you feel better. This is also not true! EMDR therapy may be emotionally intense, but it is not meant to make you feel worse. The goal of EMDR therapy is to help you process the trauma and reduce the negative emotions associated with it.

This is also not true! EMDR therapy may be emotionally intense, but it is not meant to make you feel worse. The goal of EMDR therapy is to help you process the trauma and reduce the negative emotions associated with it.

A third misconception is that EMDR therapy is only for people with PTSD. This is also not true. EMDR therapy can be helpful for people with anxiety, depression, and other mental health issues.

It will plant memories that aren’t true.A final misconception about EMDR therapy is that it will plant memories that aren’t true. This is not the case! EMDR therapy may help you remember things you had forgotten, but it will not plant false memories.

Who Can Benefit from EMDR Therapy?

There are many reasons why someone might want to try EMDR therapy.

Minimal talking is required for it to be effective.One of the benefits of EMDR therapy is that minimal talking is required for it to be effective. There is no need to tell your story in detail or relive the trauma. This can be helpful for people who have a hard time talking about their trauma.

There is no need to tell your story in detail or relive the trauma. This can be helpful for people who have a hard time talking about their trauma.

EMDR therapy can also help you process your past and make peace with it. Often, people get stuck in their trauma and cannot move on. So, this can be helpful if you have unresolved trauma.

Reduces negative thoughts and feelings.EMDR therapy can help you identify and challenge negative thoughts and feelings associated with the trauma. This can help you better understand yourself and your past to release the blame and shame you may feel around specific events in your life.

It can help you to cope with current stressors.EMDR therapy can also help you to cope with current stressors. This can be helpful if you are struggling to manage your day-to-day emotions or are currently experiencing anxiety or depression.

You may see results quickly.

Compared to other treatment options, EMDR therapy may produce results more quickly. This is because it directly targets the root of the problem. Although the goal is not to move through the sessions as quickly as possible, some people may find relief from their symptoms sooner than expected.

Tips for Getting Started with EMDR Therapy

If you’re thinking about starting EMDR therapy, you should keep a few things in mind.

Find a qualified therapist.The first step is to find a qualified therapist who has experience with EMDR therapy. This is important because you want to ensure you are working with someone who is properly trained.

Be prepared for EMDR therapy.The next step is to be prepared for EMDR therapy. This means being honest with your therapist about your trauma and what you hope to gain from therapy. It also means being willing to do the work required to process the trauma.

EMDR therapy is not right for everyone.

EMDR therapy is not right for everyone. If you’re not ready to face your trauma, EMDR therapy may not be right for you. It would help if you also spoke with your therapist about any concerns you have before starting therapy.

Makin Wellness is here to help! If you’re interested in talking to a therapist about starting EMDR therapy, we can help. Our team of qualified therapists is experienced in helping people process their trauma and heal from the past. Contact us today to schedule an appointment.

Sara Makin MSEd, LPC, NCC

All articles are written in conjunction with the Makin Wellness Research Team.

Not subscribed yet? Now's your chance. Sign up for tips on how to manage and improve relationships, stress, and mental health.

Join the wellness community!

Join our newsletter

Mental health advice & news delivered to your email

Please enable JavaScript in your browser to complete this form.

Email *

#healing happens here

Get started with Pennsylvania’s highest-rated team of specialized, professional, and accredited online therapists that can support you with a wide range of issues, including anxiety, depression, stress, grief, trauma, and more.

*Disclaimer: We cannot guarantee you will be matched with a therapist of your choice within 24 hours, but we will do our very best to match all requests as quickly as possible.

Most Visited Pages

Patient Portal

Other Useful Links

Contact Information

- (833)-274-HEAL

- [email protected]

- 239 Fourth Ave #1801, Pittsburgh, PA 15222

- Monday-Friday 7am-7pm

Facebook-f Twitter Instagram Youtube

© Makin Wellness 2022 all rights reserved

Article | EMDR Association of Russia

Liz Royle

Bolton, Lancashire, UK

persistent fatigue that cannot be explained by other diseases and which leads to a significant decrease in the level of activity. At the moment, psychotherapeutic procedures such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, pharmacological interventions and dosed physical activity are offered as therapy. This article reviews the efficacy of eye movement processing and desensitization (EMDR) in CFS. A clinical case of using EMDR when working with 491-year-old male who had been suffering from disabling CFS for 5 years despite other therapies. After 9 sessions, the client reported that his energy level had increased significantly, the need for sleep had decreased (from 3-8 pm to 9.5 hours per night), and he was able to return to work. The results of the work confirm that EMDR therapy can be useful for the treatment of CFS as part of an individualized treatment plan.

At the moment, psychotherapeutic procedures such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, pharmacological interventions and dosed physical activity are offered as therapy. This article reviews the efficacy of eye movement processing and desensitization (EMDR) in CFS. A clinical case of using EMDR when working with 491-year-old male who had been suffering from disabling CFS for 5 years despite other therapies. After 9 sessions, the client reported that his energy level had increased significantly, the need for sleep had decreased (from 3-8 pm to 9.5 hours per night), and he was able to return to work. The results of the work confirm that EMDR therapy can be useful for the treatment of CFS as part of an individualized treatment plan.

Keywords: chronic fatigue syndrome; EMDR; effectiveness of therapy; adaptive information processing; clinical case

More than one million people in the United States suffer from chronic fatigue syndrome, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2007). Statistics from the Myalgic Encephalopathy Association (2007) show that about 250,000 people in the UK suffer from CFS and related ME (myalgic encephalopathy). CFS is defined as “clinically assessed, unexplained, persistent or recurrent chronic fatigue that is recent or over a specific period of time, is not the result of ongoing stress, is not relieved by rest, and results in a significant reduction in activity levels in a professional, educational, social, or personal area” (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2008). In addition, the diagnosis of CFS requires the simultaneous presence of four or more associated symptoms. (see Table 1). nine0003

Statistics from the Myalgic Encephalopathy Association (2007) show that about 250,000 people in the UK suffer from CFS and related ME (myalgic encephalopathy). CFS is defined as “clinically assessed, unexplained, persistent or recurrent chronic fatigue that is recent or over a specific period of time, is not the result of ongoing stress, is not relieved by rest, and results in a significant reduction in activity levels in a professional, educational, social, or personal area” (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2008). In addition, the diagnosis of CFS requires the simultaneous presence of four or more associated symptoms. (see Table 1). nine0003

CFS occurs in all age groups, in young children and the elderly, but most cases occur in people 20 to 40 years of age (CDC, 2007). The severity of the disease can vary greatly, ranging from unusually severe fatigue after stressful events to complete incapacity. It is estimated that 6% of cases of CFS are cured within six months without any intervention (Thomas et al. , 2006). However, if medical intervention is necessary, the National Institute of Medicine recommends the following three treatment options (NICE, 2007):

, 2006). However, if medical intervention is necessary, the National Institute of Medicine recommends the following three treatment options (NICE, 2007):

Pharmacological interventions, including antidepressants and corticosteroids Gradual exercise therapy (A reasonable base level of physical activity is determined. The duration of the activity is then gradually increased according to a plan that is developed individually. Then the activity is gradually increased when the person is able to withstand the new exercise) . Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) suggests that psychological processes are the main cause of CFS. Research has shown that CBT not only helps some patients with CFS cope with the impact of chronic disease, but also teaches them how to cope with symptoms and improves the patient's overall functioning (Antoni & Weiss, 2003; Bazelmans et al., 2005; Deale et al., nineteen97, 1998; Kroenke & Swindle, 2000; Nezu & Maguth Nezu, 2001; NICE, 2007; Raine et al., 2002; Saxty & Hansen, 2005). However, some researchers question the effectiveness of CBT (Bazelmans & Huibers, 2005; Huibers et al., 2004; Leone et al., 2006; Van Hoof, 2003). Knoop et al. (2007) reviewed the literature on CFS, taking into account the patient's subjective feeling of fatigue and health, and found that significant improvement after CBT is possible, and complete recovery is also possible. nine0003

However, some researchers question the effectiveness of CBT (Bazelmans & Huibers, 2005; Huibers et al., 2004; Leone et al., 2006; Van Hoof, 2003). Knoop et al. (2007) reviewed the literature on CFS, taking into account the patient's subjective feeling of fatigue and health, and found that significant improvement after CBT is possible, and complete recovery is also possible. nine0003

Symptoms that may indicate the presence of CFS/ME

Cognitive dysfunction, such as difficulty thinking, inability to concentrate, impaired short-term memory, difficulty finding words, planning/organizing thoughts, and processing information insomnia, hypersomnia, feeling tired after sleep, sleep cycle disturbances Muscle and / or joint pain, multilocalized in nature and in the absence of inflammation. Headaches Painful lymph nodes without abnormal enlargement

Sore throat Symptoms of general malaise resembling a "cold" Dizziness and/or nausea Palpitations in the absence of identified cardiopathology Physical or mental effort worsens symptoms

Adapted from National Institute for Clinical Excellence (2007), p. 13.

13.

They argue that CFS research has provided ample evidence for the effectiveness of CBT for complex dysfunctional cognitions regarding the effectiveness of rest and the promotion of gradual activity. Suraway and others (1995) suggested that once a patient has sustained CFS, symptoms may be maintained by many different factors. This idea is fully consistent with the classic CBT model of emotional distress (Beck, 1976), and cognitive, behavioral, affective, and physiological factors perpetuate and prolong symptoms. Indeed, factors such as the patient's belief system and dysfunctional cognitions have been documented to influence the maintenance and worsening of CFS symptoms (Abbey, 1996; Deale et al., 1998; Suraway et al., 1995; Taillefer et al., 2002), depression (Taillefer et al., 2002), sociocultural influences (Fennel, 1995; Prins et al., 2004), and stress (Antoni & Weiss, 2003). Common themes in the psychotherapy of patients with CFS include the following: the desire for self-assertion, excessively stressful, saturated lifestyle before the onset of CFS, perfectionism and other maladaptive beliefs (Abbey, 1996). In a theoretical and empirical review of the literature, Deary et al. (2006) examined the evidence base for a model of CBT in the treatment of CFS. Looking at the likely mechanism for the onset of the symptom, they concluded that by working with cognitive and behavioral factors in CFS, CBT leads to an improvement in physical symptoms. Deale and others (1998) reported the effect of illness beliefs on the outcome of randomized controlled trials when using CBT or relaxation. Causal attribution and beliefs about exercise, activity, and rest were recorded before and after treatment in 60 CFS patients. Good outcomes in both groups were associated with avoidance behavior change and associated beliefs rather than causal attribution.

In a theoretical and empirical review of the literature, Deary et al. (2006) examined the evidence base for a model of CBT in the treatment of CFS. Looking at the likely mechanism for the onset of the symptom, they concluded that by working with cognitive and behavioral factors in CFS, CBT leads to an improvement in physical symptoms. Deale and others (1998) reported the effect of illness beliefs on the outcome of randomized controlled trials when using CBT or relaxation. Causal attribution and beliefs about exercise, activity, and rest were recorded before and after treatment in 60 CFS patients. Good outcomes in both groups were associated with avoidance behavior change and associated beliefs rather than causal attribution.

Since excessive stress, accidents and traumatic events may be determinants of CFS (Antoni & Weiss, 2003; Crofford, 2007; Heim et al., 2004; Heim et al., 2006), it can be hypothesized that Therapy that deals with psychological trauma and anxiety may be beneficial for patients with CFS. Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) is a psychotherapeutic procedure originally developed to treat the psychological effects of traumatic experiences and is recommended as an effective treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder (Bleich et al., 2002; Bisson & Andrew, 2005; Chemtob et al. , 2000; Clinical Resource Efficiency Support Team [CREST, 2003]; Department of Veterans Affairs & Department of Defense, 2004). More recently, EMDR has been effectively used to treat other psychological problems, such as anxiety disorders (Shapiro, 2005), vicarious trauma (Keenan & Royle, in press), dysmorphic disorder (Brown et al., 1997), non-psychotic morbid jealousy (Keenan & Farrell, 2000), and phantom pain (Schneider et al., 2008).

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) is a psychotherapeutic procedure originally developed to treat the psychological effects of traumatic experiences and is recommended as an effective treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder (Bleich et al., 2002; Bisson & Andrew, 2005; Chemtob et al. , 2000; Clinical Resource Efficiency Support Team [CREST, 2003]; Department of Veterans Affairs & Department of Defense, 2004). More recently, EMDR has been effectively used to treat other psychological problems, such as anxiety disorders (Shapiro, 2005), vicarious trauma (Keenan & Royle, in press), dysmorphic disorder (Brown et al., 1997), non-psychotic morbid jealousy (Keenan & Farrell, 2000), and phantom pain (Schneider et al., 2008).

The EMDR adaptive processing model suggests that much of psychopathology is rooted in stressful past experiences that have not been adequately processed (Shapiro, 2001). When new information is not adequately processed, the thoughts, images, emotions, and physical sensations associated with it are stored incorrectly and become intrusive or overwhelming, and lead to ongoing dysfunction. According to this model, CFS is considered as a combination of symptoms, which are based on inadequate processing of previous stressful experience. nine0003

According to this model, CFS is considered as a combination of symptoms, which are based on inadequate processing of previous stressful experience. nine0003

EMDR is thought to promote adaptive processing, in which associations emerge between dysfunctionally stored material and more adaptive information. This leads to reduced emotional distress, learning and "making sense" of the experience (Shapiro, 2001). The standard EMDR protocol (Shapiro, 2001) includes the detection of a statement expressing a maladaptive self-image associated with a picture. This "negative cognition" represents the client's current interpretation of themselves and is typically associated with negative feelings such as shame, powerlessness, and failure. One of the results of IPA is the transformation of the negative self-image and associated stressful material into a more realistic, appropriate and adaptive view. As discussed above, research shows that a patient's dysfunctional cognitions have the ability to maintain CFS symptoms. Therefore, this provision formed the basis for the rationale for the use of EMDR in patients with CFS in the following anonymous case study. At the time of this writing, PsycINFO and Medline searches have not found any published research on the use of EMDR in the treatment of CFS. This case demonstrates the applicability of EMDR in the treatment of CFS, therefore, based on the positive results of therapy, it can be assumed that further research is needed in the form of a larger number of clinical cases. nine0003

Therefore, this provision formed the basis for the rationale for the use of EMDR in patients with CFS in the following anonymous case study. At the time of this writing, PsycINFO and Medline searches have not found any published research on the use of EMDR in the treatment of CFS. This case demonstrates the applicability of EMDR in the treatment of CFS, therefore, based on the positive results of therapy, it can be assumed that further research is needed in the form of a larger number of clinical cases. nine0003

Case Presentation

Andy, a married man of 49 and a father of two, was diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome in 2002. For the next few years, he was treated at a public clinic specializing in the treatment of ME/CFS. Therapy consisted of exercise therapy and antidepressants, but the patient did not progress. In early 2006, Andy was also referred to short-term solution-oriented therapy, and it was this therapist who then referred him to the author of the article. Hypersomnia had a huge negative impact on Andy's life, often he slept for 15-20 hours a day, and he was physically and mentally tired even from simple household chores. Since 2002, he tried twice to return to work, but then relapsed again, and fatigue left him completely incapacitated. He has been unable to work since 2003. Andy was in a depressed mood, he often had outbursts of anger directed at family members. He never resorted to violence, but anger management was one of the top priorities in his therapy. nine0003

Hypersomnia had a huge negative impact on Andy's life, often he slept for 15-20 hours a day, and he was physically and mentally tired even from simple household chores. Since 2002, he tried twice to return to work, but then relapsed again, and fatigue left him completely incapacitated. He has been unable to work since 2003. Andy was in a depressed mood, he often had outbursts of anger directed at family members. He never resorted to violence, but anger management was one of the top priorities in his therapy. nine0003

Complaints

In addition to hypersomnia, Andy suffered from cognitive dysfunction. He said that he could not concentrate, suffered from problems with short-term memory, and also had difficulty choosing words and organizing thoughts. Mental efforts aggravated physical fatigue; long telephone conversations, work at a computer and work with documents were especially difficult for him. Andy also talked about symptoms such as irritability, intrusive thoughts and images associated with previous stressors at work, and an unexplained tingling sensation in the legs. He viewed himself very negatively. Andy told his therapist that he had gone from a highly successful career person to a complete "loser". During the conversation, Andy kept interspersing his speech with negative statements like "I can't handle it," "I'm not in control," and "I can't do anything about it." nine0003

He viewed himself very negatively. Andy told his therapist that he had gone from a highly successful career person to a complete "loser". During the conversation, Andy kept interspersing his speech with negative statements like "I can't handle it," "I'm not in control," and "I can't do anything about it." nine0003

History

Andy fell ill after what he described as a long period of very intensive work, including overtime. This, and the change in his professional role in a large corporation, led him to feel that he was unable to meet the ever-increasing demands. In 2002, after seven years of extremely physically and emotionally intense work, he reached the point of extreme fatigue, which he himself described as "a complete physical shutdown." Other notable events include his father's death two years earlier, after a long illness, and the period before his diagnosis of CFS, when he lived in constant fear of losing his job due to layoffs at his job. Childhood, according to him, was quite ordinary, without any difficult events or periods of stress. Andy claimed that before the stressful situation at work, he never had negative thoughts about himself, and he always perceived himself as a confident and talented person. Andy also said that close and supportive relationships reign within the family. nine0003

Andy claimed that before the stressful situation at work, he never had negative thoughts about himself, and he always perceived himself as a confident and talented person. Andy also said that close and supportive relationships reign within the family. nine0003

Evaluation

In the evaluation session, Andy described himself as: “…tense, I always get overwhelmed by little things and get very tired. (My) reactions are completely inadequate… suffering from flashbacks, mostly work-related. I can’t do anything ... I have no idea how to begin to recover, I’m taking antidepressants again. ” He slept 15-20 hours a day, and even the simplest household chores like washing completely deprived him of strength, both physical and mental. nine0003

Case Conceptualization

Andy and I had a total of nine sessions over 4 months. We met once a week, by the end of therapy the interval between sessions increased. According to the 8 Phases of EMDR Therapy (Shapiro, 2001), the first few sessions were devoted to taking anamnesis and preparing Andy for work in EMDR. We clarified his current coping strategies and then mastered breathing techniques and relaxation. We quickly established a good rapport and found a safe place. In the course of developing a therapy plan, specific targets for processing were identified - memories that seemed to trigger the pathological process, as well as situations in the present that increased dysfunction. Andy identified three groups of memories with common keywords (negative cognitions), which were combined into clusters to obtain a generalization effect. These groups are listed below in chronological order:

We clarified his current coping strategies and then mastered breathing techniques and relaxation. We quickly established a good rapport and found a safe place. In the course of developing a therapy plan, specific targets for processing were identified - memories that seemed to trigger the pathological process, as well as situations in the present that increased dysfunction. Andy identified three groups of memories with common keywords (negative cognitions), which were combined into clusters to obtain a generalization effect. These groups are listed below in chronological order:

Andy is flooded at work and is desperately trying to keep control of the situation by working more and more overtime. sick leave fear that he will have to return to work again, and re-illness.

Treatment and progress assessment

The EMDR protocol recommends starting from the earliest worrying memory. Consequently, once Andy was ready for the EMDR phase, the decision was made to rework his memories of the flooding he experienced at work. He was asked to single out one event that would represent the entire cluster. The picture that came to him is that he is standing at his workplace and looks like a "wreck", "too much to do", a negative statement about himself - "I am a loser." When asked about positive cognition, Andy ultimately answered, “I can be successful,” but rated Positive Cognition Confidence (PPC) at 2 on a scale of 1–7, indicating low confidence. Andy said he felt "lethargic, negative, like a wet lettuce leaf". The physiological reaction to the picture is the feeling that his "body is vibrating, his head is spinning." Score on the Subjective Anxiety Scale (SWB) was 9, on a scale of 0–10, indicating a high degree of anxiety. Andy was asked to think about this picture while being aware of his physiological response and the negative cognition "I'm a loser." The therapist then performed saccadic visual stimulation.

He was asked to single out one event that would represent the entire cluster. The picture that came to him is that he is standing at his workplace and looks like a "wreck", "too much to do", a negative statement about himself - "I am a loser." When asked about positive cognition, Andy ultimately answered, “I can be successful,” but rated Positive Cognition Confidence (PPC) at 2 on a scale of 1–7, indicating low confidence. Andy said he felt "lethargic, negative, like a wet lettuce leaf". The physiological reaction to the picture is the feeling that his "body is vibrating, his head is spinning." Score on the Subjective Anxiety Scale (SWB) was 9, on a scale of 0–10, indicating a high degree of anxiety. Andy was asked to think about this picture while being aware of his physiological response and the negative cognition "I'm a loser." The therapist then performed saccadic visual stimulation.

Between sets of eye movements, Andy reported having many flashbacks of memories related to work, illness, and family life. He noted "feelings of hopelessness", "lack of energy" and "I see myself lying in bed". nine0003

He noted "feelings of hopelessness", "lack of energy" and "I see myself lying in bed". nine0003

Andy was asked to just think about it, and a few more sets followed. The first session was unfinished (although the SSB was down to 6) and a safety assessment was made at the close of the session and the client was reminded that processing could continue. Andy kept a diary in which he recorded his thoughts, feelings, memories and dreams between sessions to track changes and revisions and identify material to work on in subsequent sessions. nine0003

In the next session, Andy reported that his energy level increased in the next 24 hours after the session, and he himself spoke of moments when he was able to do something in the past week. However, during the reassessment, when Andy was asked to rate the level of anxiety associated with the event he was working on last week, it turned out that the SSB had risen to 6 and a rework was needed. When Andy was asked what words best fit this picture, he immediately replied: “It's all my fault. I had to do something." The image of Andy standing in the middle of "a pile of paperwork" led to emotions such as "dazedness, sadness and guilt", as well as physical sensations of tingling in the legs and fainting. Andy's positive cognition was "It's not my fault", KDP - 1.

I had to do something." The image of Andy standing in the middle of "a pile of paperwork" led to emotions such as "dazedness, sadness and guilt", as well as physical sensations of tingling in the legs and fainting. Andy's positive cognition was "It's not my fault", KDP - 1.

In this session, between sets of eye movements, Andy increasingly looked at the situation positively, stating "It's not my fault", "the problem is them (in the corporation), not me."

Even though the session didn't end again, Andy was sure that some sort of adaptive processing had taken place. Indeed, during the re-evaluation at the beginning of the next session, Andy reported that he had stopped obsessive thoughts and images associated with the workplace, the BSP was 0, and he clearly could not take responsibility for what happened. Although there were no significant changes in regards to fatigue and hypersomnia, Andy felt that the EMDR work had been beneficial to the topic of anger and self-image, and he was motivated to continue with the therapy plan. nine0003

nine0003

The last target for desensitization (in session 7) was related to his current fear of returning to work and lack of control and willingness to invest in the future. Andy had a picture of him at work, overwhelmed by anxiety, fear, and the I'm Vulnerable NC. The BSC turned out to be 10. It was difficult to determine the positive cognition for this picture, but in the end he was satisfied with the option "I can protect myself", the DPC was 1. The physiological reaction to the picture and negative cognition was "heavy in the shoulders and tightness in the chest." nine0003

Between sets of eye movements, Andy said that the fear was getting worse, the thought “they (the corporation) can make me go back to it”, “they are pulling my strings” came to him.

After the following sets, Andy had the insight that during that work situation in the past, his only escape from excessive demands was sleep. Therefore, now the state of not sleeping, waking, served as a trigger that caused him fear that now he would be presented with exorbitant demands that would lead to increased anxiety and exhaustion. The following sets led to internal conflict: "I want to prove them wrong (by returning to work)" and "If I get better, I will have to return", then "I could do it" and "I cannot trust them with my well-being … they don’t care about that.” nine0003

The following sets led to internal conflict: "I want to prove them wrong (by returning to work)" and "If I get better, I will have to return", then "I could do it" and "I cannot trust them with my well-being … they don’t care about that.” nine0003

Andy explored his future and his options, including returning to what he described as a "toxic" environment. If Andy got better, he would have to return, and he did not trust either the employer or his ability to protect himself. At this point, Andy's therapist asked him to imagine how he could control the situation even a little, "just think about it," followed by another set of eye movements. During this set, Andy began to understand that he had a certain power in this situation, that he was able to make a choice and protect himself. After this set, Andy noticeably relaxed and came to the solution of this dilemma himself. After the next sets, he naturally came to believe that he could make a choice and protect himself, and during the installation of positive cognition, the WPC rose to 7.

This was the last necessary breakthrough, after which Andy's energy levels skyrocketed. The next two sessions took place on a monthly basis to give Andy time to explore his new sense of self, his goals, and gradually make small changes while continuing to receive support from the therapist.

Results of therapy

Six months after the end of therapy, Andy was optimistic, led an active lifestyle, made many changes and planned for the future. Despite Andy's decision not to return to his former employer, he resumed work in a different environment and enjoyed the feeling of meaning and building a new life. Family members noted that he had changed. Andy himself said that his situation “improved in a way that I did not even dream of. (On vacation) I felt so relaxed and normal that I was able to walk five miles without getting seriously tired. In a week I did five of these walks ... how great it was! Long-term monitoring 12 months after the end of therapy showed that Andy slept an average of 9,5 o'clock. Progress has been preserved, the level of activity and pleasure from work, too.

Progress has been preserved, the level of activity and pleasure from work, too.

Background of therapy and recommendations for therapists and students

This case demonstrates the use of EMDR therapy with a patient who had suffered from CFS for 6 years and was able to restore the quality of life and the ability to look to the future with hope. According to the TIP model underlying EMDR therapy, the identification and processing of etiological events leads to a decrease in the intensity of symptoms (Shapiro, 2001). The earliest memories Andy reported were not from childhood or adolescence. They were associated with the onset of feeling overtired and the appearance of the NC "I am a loser" before the diagnosis of CFS. From the IPA's point of view, these feelings of physical exhaustion and emotional flooding have been inadequately processed. These experiences then became obsessive, as did the imagery associated with these memories, which led to the development of CFS. The API model suggests that EMDR stimulates the recycling of such dysfunctionally stored material. By targeting memories of exhaustion and emotional flooding, Andy was able to shift from dysfunctional and symptom-supporting negative cognitions to positive, empowering cognitions, and was able to take a fresh look at his current situation. nine0003

The API model suggests that EMDR stimulates the recycling of such dysfunctionally stored material. By targeting memories of exhaustion and emotional flooding, Andy was able to shift from dysfunctional and symptom-supporting negative cognitions to positive, empowering cognitions, and was able to take a fresh look at his current situation. nine0003

Because CFS is defined by the symptoms and not by the underlying cause, the diagnosis can actually be associated with many different conditions, all of which will have similar symptoms. (ME Association, 2007). Therefore, it is unlikely that any one type of therapy will work in all cases. The above case supports the idea that EMDR therapy may be useful if CFS is based on excess stress, accidents, or traumatic events. For patients like Andy who suffer from negative self-image, obsessive thoughts and images, EMDR therapy can be effective in resolving maladaptive beliefs and their associated somatic symptoms. Andy's therapy consisted of only nine sessions, which proves the effectiveness of the therapy in his case. Patients diagnosed with CFS who have a history of earlier psychological trauma will require a more complex therapy, including sequential processing of earlier important experiences in addition to those events that are directly related to the current symptomatology. nine0003

Patients diagnosed with CFS who have a history of earlier psychological trauma will require a more complex therapy, including sequential processing of earlier important experiences in addition to those events that are directly related to the current symptomatology. nine0003

Since the example given is a clinical case, a placebo effect cannot be completely ruled out. However, the fact that Andy's symptoms of CFS did not return and, based on the results of monitoring carried out after 12 months, we can say that there is a stable positive effect. More clinical trials are needed to consider effective treatment options for CFS. This case demonstrates the applicability of EMDR therapy in CFS, and the positive results point to the need for further research involving more patients on EMDR as primary therapy. These studies may initially focus on a group of clients whose CFS is most likely due to increased stress, accidents, or traumatic events. Further research on the effectiveness of EMDR therapy in the treatment of patients with CFS should take into account the competence of the therapist, the degree of compliance with the EMDR protocol, and the use of psychometric diagnosis of fatigue (individual strength checklist) and functional disability (disease impact profile) as quantitative measures of progress. . nine0003

. nine0003

References

Abbey, S. E. (1996). Psychotherapeutic perspectives on chronic fatigue syndrome. New York: Guilford Press.

Antoni, M. H., & Weiss, D. E. (2003). Stress and immunity. In L. A. Jason, P. A. Fennell, & R. R. Taylor (Eds.), Handbook of chronic fatigue syndrome (pp. 527–545). New York: Wiley.

Bazelmans, E., & Huibers, M. J. H. (2005). A qualitative analysis of the failure of CBT for chronic fatigue conducted by general practitioners. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 33(2), 225–235. nine0003

Bazelmans, E., Prins, J. B., Lulofs, L., & Van der Meer, J. W. M. (2005). Cognitive behavior group therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome: A non-randomised waiting list controlled study. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 74(4), 218–224.

Beck, A. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New York: Meridian.

Bisson, J., & Andrew, M. (2007). Psychological treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 3, Art. no. CD003388. nine0003

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 3, Art. no. CD003388. nine0003

Bleich, A., Kotler, M., Kutz, E., & Shaley, A. (2002). Guidelines for the assessment and professional intervention with terror victims in the hospital and community, A position paper of the (Israeli) National Council for Mental Health.

Brown, K. W., McGoldrick, T., & Buchanan, R. (1997). Body dysmorphic disorder: Seven cases treated with eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 25(2), 203–207.

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. Retrieved September 11, 2007, from www.cdc.gov/cfs/

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. Retrieved July 12, 2008, from www.cdc.gov/cfs/cfsdefinitionHCP.htm

Chemtob, C. M., Tolin, D. F., van der Kolk, B. A., & Pitman, R. K. (2000). Eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing. In E. B. Foa, T. M. Kean, & M. J. Friedman (Eds.), Effective treatments for PTSD: Practice guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (pp. 139–155, 333–335). New York: Guilford.

139–155, 333–335). New York: Guilford.

Clinical Resource Efficiency Support Team (CREST). (2003). The management of post traumatic stress disorder in adults. Belfast: Northern Ireland Department of Health. nine0003

Crofford, L. J. (2007). Violence, stress and somatic symptoms. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 8(3), 299–313.

Deale, A., Chalder, T., Marks, I., & Wessely, S. (1997). Cognitive behavior therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154, 408–414.

Deale, A., Chalder, T., & Wessely, S. (1998). Illness beliefs and treatment outcome in chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 45(1), 77–83. nine0003

Deary, V., Chalder, T., & Sharpe, M. (2007). The cognitive behavioral model of medically unexplained symptoms: A theoretical and empirical review. Clinical Psychology Review, 27(7), 781–797.

Department of Veterans Affairs & Department of Defense. (2004). VA/DoD clinical practice guidelines for the management of post traumatic stress. Washington, DC: Author.

Washington, DC: Author.

Fennel, P. A. (1995). CFS sociocultural influences and trauma: Clinical considerations. Journal of CFS, 1(3–4), 159-173.

Heim, C., Bierl, C., Nisenbaum, R., Wagner, D., & Reeves, W. C. (2004). Regional prevalence of fatiguing illnesses in the United States before and after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Psychosomatic Medicine, 66(5), 672–678.

Heim, C., Wagner, D., Maloney, E., Papanicolaou, D. A., Solomon, L., Jones, J. F., et al. (2006). Early adverse experience and risk for chronic fatigue syndrome. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(11), 1258–1266.

Huibers, M. J. H., Beurskens, A. J. H. M., Van Schayck, C. P., Bazelmans, E., Metsemakers, J. F. M., Knottnerus, J. A., et al. (2004). Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy by general practitioners for unexplained fatigue among employees: Randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 184(3), 240–246. nine0003

Keenan, P. S., & Farrell, D. P. (2000). Treating non- psychotic morbid jealousy with EMDR, utilizing cognitive interweave. A case report. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 13(2), 175–189.

Treating non- psychotic morbid jealousy with EMDR, utilizing cognitive interweave. A case report. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 13(2), 175–189.

Keenan, P., & Royle, E. (2008). Vicarious trauma and first responders: A case study utilizing eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) as the primary treat- ment modality. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health, 9(4), 291–298.

Knoop, H., Gielissen, M. F. M., & White, P. D. (2007). Is a full recovery possible after cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome? Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 76(3), 171–176. nine0003

Kroenke, K., & Swindle, R. (2000). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for somatization and symptom syndromes: A critical review of controlled clinical trials. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 69(4), 205–215.

Leone, S. S., Huibers, M. J. H., Kant, I., van Amelsvoort, L. G. P. M., van Scayck, C. P., Bleijenberg, G., et al. (2006). Long-term efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy by general practitioners for fatigue: A 4-year follow-up study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 61(5), 601–607. nine0003

Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 61(5), 601–607. nine0003

ME Association. (2007). Retrieved June 11, 2007, from www.meassociation.org.uk

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. (2005). The management of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults and children in primary and secondary care. London: Author.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. (2007). Chronic fatigue syndrome myalgic encephalomyelitis (or encephalopathy). Diagnosis and management of CFS/ME in adults and children. London: Author.

Nezu, A. M., & Maguth Nezu, C. (2001). Cognitive- behavior therapy for medically unexplained symptoms: A critical review of the treatment literature. Behavior

Therapy, 32(3), 537–583. Prins, J. B., Bos, E., Huibers, M. J. H., Servaes, P., van der

Werf, S. P., van der Meer, J. W. M., et al. (2004). Social support and the persistence of complaints in chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 73(3), 174–182.

Raine, R. , Haines, A., Sensky, T., Hutchings, A., Larkin, K., & Black, N. (2002). Systematic review of mental health interventions for patients with common somatic symptoms: Can research evidence from secondary care be ex-trapolated to primary care? British Medical Journal, 325, 1082–1093.

, Haines, A., Sensky, T., Hutchings, A., Larkin, K., & Black, N. (2002). Systematic review of mental health interventions for patients with common somatic symptoms: Can research evidence from secondary care be ex-trapolated to primary care? British Medical Journal, 325, 1082–1093.

Saxty, M., & Hansen, Z. (2005). Group cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome: A pilot study. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 33(3), 311–318.

Schneider, J., Hofman, A., Rost, C., & Shapiro, F. (2008). EMDR in the treatment of phantom limb pain. Pain Medicine, 9(1), 76–82.

Shapiro, F. (2001). Eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing: Basic principles, protocols and procedures (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press. nine0003

Shapiro, R. (2005). Solutions: Pathways to healing. New York: Norton.

Suraway, C., Hackman, A., Hawton, K., & Sharpe, M. (1995). CFS: A cognitive approach. Behavioral Research Therapy, 33, 535–544.

Taillefer, S. S., Kirmayer, L. J., Robbins, J. M., & Lasry, J. C. (2002). Psychological correlates of functional status in CFS. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53, 1097–1106.

J., Robbins, J. M., & Lasry, J. C. (2002). Psychological correlates of functional status in CFS. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53, 1097–1106.

Thomas, M., Sadlier, M., & Smith, A. (2006). The effect of multi convergent therapy on the psychopathology, mood and performance of chronic fatigue syndrome patients: A preliminary study. Counseling & Psychotherapy Research, 6(2), 91–99.

Van Hoof, E. (2003). Cognitive behavioral therapy as cure-all for CFS. Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, 11(4), 43–47.

Wearden, A., Morriss, R., Mullis, R., Strickland, P., Pearson, D., Appleby, L., et al. (1998). A double-blind placebo controlled trial of fluoxetine and graded exercise for CFS. British Journal of Psychiatry, 172, 485–490.

Correspondence regarding this article should be directed to Liz Royle, Pathways Through Trauma, 13 Chorley Old Road, Bolton, Lancashire, UK. E-mail: liz.royle@ pathwaysthroughtrauma.co.uk

Experience in using the EMDR method in working with psychological trauma

Olesya Simonova Head of the Psychological Service of the Future Now Charitable Foundation

Natalia Vorotylo A. I. Evdokimova, psychologist, Charitable Foundation "Future Now"

I. Evdokimova, psychologist, Charitable Foundation "Future Now"

Resume. The article describes the specifics of the EMDR method (EMDR) in working with psychological trauma. The mechanism of bilateral stimulation is considered. The description of three clinical cases from the practice of the authors is given. nine0003

What can cause psychological trauma? In general, any kind of events. For example, an accident, a serious illness or a divorce. Someone will remember a situation that from the outside would never have seemed traumatic, but it had a huge impact on the person himself. In short, psychological trauma is everything that hurts. And a bloody wound can hurt, and a finger after an unsuccessful cutting off of a burr. There is only one criterion of seriousness - how much does it hurt? If it hurts without ceasing, measures must be taken, even if the reason is seemingly trifling. nine0003

Symptoms of psychological trauma are sleep disorders, anxiety, apathy, fears. In some cases, as a result of a strong experience, a state of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) develops.

In some cases, as a result of a strong experience, a state of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) develops.

PTSD occurs as a delayed or prolonged reaction to an exceptionally threatening or catastrophic event that can cause stress in almost everyone (ICD-10, F43.1). PTSD can develop in people who have been in combat, experienced a life-threatening situation, and even in those who simply witnessed such a situation. nine0003

In the practice of a clinical psychologist, PTSD is one of the most common reasons for seeking help. This disorder manifests itself in the form of symptoms that significantly complicate a person’s life: insomnia, recurring nightmares, “flushes” of traumatic memories, isolation from others. If the victim is not provided with the necessary psychological assistance, PTSD can lead to permanent personality changes (F62.0. Traumatic neurosis).

One of the features of psychological trauma is its veiled nature, when the symptoms seem to be not clearly connected with the traumatic event. Let's compare it with a physical injury: if you hit your hand, your hand hurts - everything is quite clear. With psychological trauma, there are also "simple" situations: a person got into an accident - he began to be afraid to drive a car. However, such transparent symptoms of trauma are far from always. In the same situation with an accident, such a scenario is possible when the victim seems to have already forgotten about the incident and calmly drives a car, but at the same time, shortly after the accident, he developed terrible headaches and nightmares at night, and maybe even developed a serious illness ( such as diabetes or hypertension). Thus, in working with psychological trauma, it is very important to isolate its core, the true cause, the initial experience, which was not properly processed and, as a result, "overgrown" with a whole "bouquet" of symptoms. nine0283

Let's compare it with a physical injury: if you hit your hand, your hand hurts - everything is quite clear. With psychological trauma, there are also "simple" situations: a person got into an accident - he began to be afraid to drive a car. However, such transparent symptoms of trauma are far from always. In the same situation with an accident, such a scenario is possible when the victim seems to have already forgotten about the incident and calmly drives a car, but at the same time, shortly after the accident, he developed terrible headaches and nightmares at night, and maybe even developed a serious illness ( such as diabetes or hypertension). Thus, in working with psychological trauma, it is very important to isolate its core, the true cause, the initial experience, which was not properly processed and, as a result, "overgrown" with a whole "bouquet" of symptoms. nine0283

According to WHO, one of the most effective psychotherapeutic tools in dealing with psychological trauma, including PTSD, is the EMDR method (EMDR). Symptoms of psychological trauma are sleep disorders, anxiety, apathy, fears. In some cases, as a result of a strong experience, a state of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) develops.

Symptoms of psychological trauma are sleep disorders, anxiety, apathy, fears. In some cases, as a result of a strong experience, a state of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) develops.

EMDR method (Eye movement desensibilization and reprocessing) has been used since 1980s. It differs from other methods of psychotherapy in that it relies on the physiological principle of bilateral stimulation. In order to characterize the way EMDR influences traumatic experience, it is necessary to recall the mechanisms of sleep.

From the point of view of physiology, sleep is a state based on special rhythms of the brain, which differ from the rhythms of wakefulness. Depending on the phase of sleep, the rhythm may be faster or slower. The phase of REM sleep is distinguished, when the rhythm of the electrical activity of the brain is highest. This phase has characteristic external manifestations: rapid breathing and eye movements during sleep. nine0003

nine0003

An important role of REM sleep is that it is during it that active processing of the impressions that a person has accumulated during the day takes place: here is the stress from an early rise, and the “warm welcome” of public transport, and other small and not very moments of irritation . Indeed, if all these impressions remained unchanged in the brain, they would need a truly gigantic receptacle. But our brain works on the principle of economy and prefers to get rid of unnecessary experiences. And before getting rid of it, it recycles them, doing it just in the REM phase. nine0003

The recycling conveyor works tirelessly, but some impressions are beyond the power of its "millstones". It is precisely such experiences that have not undergone “secondary processing” that become traumatic experiences that trigger the formation of symptoms of psychological trauma. In the above example with an accident, such an experience could be the fear of death, which turned out to be so strong that it was not perceived by consciousness, was suppressed, but, of course, did not disappear, but seemed to upset the system from the inside and led to serious consequences. nine0003

nine0003

So, in working with psychological trauma, it is very important to find a way to process those experiences that were blocked for some reason. In the EMDR method, processing occurs with the help of bilateral stimulation. What it is?

Bilateral stimulation is the alternating stimulation of the right and left hemispheres. It is achieved in very simple ways: rapid eye movements left and right, touching the right and left hand (or foot) in turn, sound through the headphones alternately in the left and right ear. This stimulation is thought to elicit a response in the brain in the form of REM sleep rhythms. Thus, during bilateral stimulation, being awake and deliberately directing attention to traumatic experiences, we compensate for the lack of timely processing. nine0301

The mechanism of bilateral stimulation as a way of processing traumatic information was discovered relatively recently, in 1987. The discovery does not belong to psychologists or physiologists, but to a philologist named Francis Shapiro. She considered studying English literature as her life's work, until she fell ill with cancer at the age of less than 40. They managed to cope with the disease, but the circle of interests of Mrs. Shapiro completely changed: she began to study ways to influence the physical and mental state of a person (in psychological terms, self-regulation mechanisms). Frances became very observant and, perhaps because of this, one day she noticed that some of the thoughts that disturbed her disappeared without a trace during a routine walk in the park. Remembering them, Frances did not feel the anxiety that had overcome her before. After analyzing all the factors that took place at that moment, the woman noticed that her eyes began to move involuntarily from side to side when she thought about the disturbing situation. Then experiments began: what will happen if, thinking about something exciting, we start moving our eyes on purpose? Ms. Shapiro changed the amplitude and pace, and as a result, she became convinced that the intensity of experiences really decreases, which was also confirmed when working with other people.

She considered studying English literature as her life's work, until she fell ill with cancer at the age of less than 40. They managed to cope with the disease, but the circle of interests of Mrs. Shapiro completely changed: she began to study ways to influence the physical and mental state of a person (in psychological terms, self-regulation mechanisms). Frances became very observant and, perhaps because of this, one day she noticed that some of the thoughts that disturbed her disappeared without a trace during a routine walk in the park. Remembering them, Frances did not feel the anxiety that had overcome her before. After analyzing all the factors that took place at that moment, the woman noticed that her eyes began to move involuntarily from side to side when she thought about the disturbing situation. Then experiments began: what will happen if, thinking about something exciting, we start moving our eyes on purpose? Ms. Shapiro changed the amplitude and pace, and as a result, she became convinced that the intensity of experiences really decreases, which was also confirmed when working with other people. As a result, the concept of the method was formulated and its protocol was described, which included several stages. nine0003

As a result, the concept of the method was formulated and its protocol was described, which included several stages. nine0003

Briefly, the EMDR procedure looks like this. At the first stage there is a discussion of the problem faced by the client. It is important here to focus on the core of the difficulty, the most disturbing experience. This may be a feeling of powerlessness, shame, fear, etc. Under the power of traumatic experiences, a person may feel weak, lost control over what is happening, guilty of what happened to him. The danger of such an experience is that it occurs in many life situations that somehow resemble the one that caused the trauma. To single him out among a heap of symptoms of trauma is the primary goal of psychological help. The client's task here is to reproduce the "picture" of the traumatic experience as accurately as possible. At this stage, working within the framework of the EMDR method differs little from any other type of psychotherapy. nine0003

At the second stage, the selected experience becomes the target of influence: the client remembers his experience, and bilateral stimulation is simultaneously performed. In order to track the change in the intensity of the experience, scaling is used: the client determines how painful the experience is for him on a 10-point scale, and then he also determines the change in his feelings in the process of work in points. The purpose of this (main) stage is to reduce the intensity of the experience, if possible, to zero. nine0003

In order to track the change in the intensity of the experience, scaling is used: the client determines how painful the experience is for him on a 10-point scale, and then he also determines the change in his feelings in the process of work in points. The purpose of this (main) stage is to reduce the intensity of the experience, if possible, to zero. nine0003

Quite often this can be done in just one or two meetings. As a result, the experience loses its sharpness: it is remembered as one of the events of life, it does not cause pain and tears, as before. In this article, we want to describe several cases of using the EMDR method.

Case 1.

A young woman, Inna, mother of two boys, three and one years old, came to me because of fears of contagious diseases. Everything was bearable until the birth of the children, but now she was very worried: what if one of the babies would infect the other all the time. A legitimate experience, if not for one "but". During the period when her sons fell ill, Inna was nervous and distanced herself from the sick child, feeling his guilt: “Why does he touch everything? He will infect everyone." nine0003

During the period when her sons fell ill, Inna was nervous and distanced herself from the sick child, feeling his guilt: “Why does he touch everything? He will infect everyone." nine0003

Where did it come from? It turned out that at the age of 10, Inna contracted scabies from her beloved girlfriend. From the girl picked up a contagious disease and her dad, "terrible pedant and neat." He reproached his daughter more than once in his hearts: “How is it possible for me to contract the disease of brothels? How could you take it?" The healing lasted almost six months. Six months, during which, at the mere mention of the infection, the girl became like a tight string. She felt very guilty. Everyone recovered, but the mental state of tension and guilt in the case of a contagious disease remained. nine0003

With these memories we began to work in session. And in half an hour they went from a high level of anxiety (8 out of 10) to an almost complete decrease (1.5 out of 10) and a sense of acceptance of such situations. Inna described her bodily sensations as "springs inside", filled with fear and disgust. In the course of our work, these “springs unbent” and disappeared. At the end of the work, we asked the woman to imagine a similar situation where one of the babies infects the other. And Inna calmly and gently said: “Anything is possible! It's funny to twitch if the child touched something. nine0003

Inna described her bodily sensations as "springs inside", filled with fear and disgust. In the course of our work, these “springs unbent” and disappeared. At the end of the work, we asked the woman to imagine a similar situation where one of the babies infects the other. And Inna calmly and gently said: “Anything is possible! It's funny to twitch if the child touched something. nine0003

During bilateral stimulation, she remembered that she felt lonely while she was sick, no one hugged her, and she, just a baby, had to cope with these experiences on her own. During psychological work, we integrate the old experience and the new life situation. EMDR therapy helps a lot with this. Inna managed to combine her experience and the experience of her children: “You shouldn't doom them to loneliness. The disease will pass and there will be a long, good life. We need to be together and together we can do it.” nine0003

Six months after the events described, Inna describes her guilt as being controlled. “I can trace this condition in its infancy and masterfully manage my sensations and emotions. Therefore, globally, I began to treat all the "byaks" more calmly.

“I can trace this condition in its infancy and masterfully manage my sensations and emotions. Therefore, globally, I began to treat all the "byaks" more calmly.

Case 2.

Tatiana, 40 years old, came for a consultation about controlling her diet. “After lunch, point X comes to me when it carries. I start eating sweets and I can’t stop, I gorge myself to the point of nausea. I bought ice cream for all the household members and not to eat one - secretly ate five packs in the kitchen. Fun and free, like time erases when I eat sweets. But after that I feel physically unpleasant and have a great feeling of guilt.” nine0003

You may already have an idea of what it's like to live all the time denying yourself sweets and at the same time experiencing bouts of secret eating. Tatyana felt insane, weak-willed, but in a situation with sweets she wanted to feel herself making decisions independently and being able to manage her life. Having set such a goal for therapy in the first session, we set to work.

Having set such a goal for therapy in the first session, we set to work.

After two sets of bilateral stimulation, Tatyana remembered an incident from her childhood: “I don't understand why it creeps into my head. It doesn't seem to have anything to do with it." At the age of nine, the girl, along with her friends, indulged, twisting and then sharply releasing the handle of the well. It was fun, but suddenly the girl's hand slipped, and the pen hit her temple. Immediately nauseous, all that was left was to go and lie down. Parents were afraid to say this - what if they scold and stop loving? It remained silent, feeling guilty: “Why didn’t you say?”. This is how the beginning of the story about the sweet was found. At the age of nine, the girl experienced the whole range of feelings that she encounters in a relationship with overeating sweets: at first fun and freedom, then nausea comes, and as a result - tension and secret guilt. nine0003

Stopping and replacing old behavior patterns with new ones is one of the goals of EMDR therapy. We continued to work, reducing the feeling of helplessness from 10 to 0. At the meeting a week later, Tatyana spoke about the feeling of emptiness and readiness to go further in this work. She managed to lose two kilograms in a week. But she was worried that the desire for sweets would return.

We continued to work, reducing the feeling of helplessness from 10 to 0. At the meeting a week later, Tatyana spoke about the feeling of emptiness and readiness to go further in this work. She managed to lose two kilograms in a week. But she was worried that the desire for sweets would return.

The goal we set for this meeting is self-confidence. With bilateral stimulation, interfering thoughts-sets “surfaced” - the words of the grandmother: “You can’t be so arrogant! This is bad". At the same time, Tatyana wanted to live with sweets: so that you could take a piece when you want, and not when you just see it. After two sets, confidence was strengthened due to the formulated thought: “No one can take this away from me. I'm already an adult. There is nothing to be afraid of, everything is already behind. At the end of this work, Tatyana spoke about the confidence that nothing could lead her astray, and the situation itself was no longer worth such attention. nine0003

At the next consultation, Tatyana told that she had taken her daughter on an excursion to the Museum of Russian Dessert. “The tables were full of sweets, desserts. I took one gingerbread, bit off a piece. I'm not afraid of anything, I didn't even eat up. It doesn't taste good, I just checked. It's been 21 days since I started this job and I don't feel like buying sweets and eating." At a chance meeting after 7 months, Tatyana looked pleased with her figure, she ate only honey from sweets.

“The tables were full of sweets, desserts. I took one gingerbread, bit off a piece. I'm not afraid of anything, I didn't even eat up. It doesn't taste good, I just checked. It's been 21 days since I started this job and I don't feel like buying sweets and eating." At a chance meeting after 7 months, Tatyana looked pleased with her figure, she ate only honey from sweets.

Case 3.

Ulyana, 20 years old, at the first meeting spoke about her fear of taking blood: “It's time to go to get tested, but I can't - I'm shaking. I’ll go to the clinic, stand and turn back.” Also, the girl's fingers went numb, her chest tightened even at the mention of medical procedures, open wounds, not to mention cases of direct collision, where her voice and thinking failed for a while. In the latter cases, the only option was to flee. During the EMDR sessions, Ulyana spoke about several cases from childhood associated with terrible memories of the hospital and blood. The study of each of these cases took 1-2 sessions. After two months of work, we parted for the summer holidays. Upon her return, Ulyana said that something had happened in the last sessions, “it clicked me.” Now, when one of her classmates made rude jokes about dead people or open wounds, she could already smile. The intrinsic motivation of the new behavior was supported by the idea: “This is not happening to me. Everything is fine". In our work, we paid special attention to the sensations in the hands: very gradually we went from a feeling of weakness and numbness in the fingers to a feeling of strength in the palms. It was on this feeling that Ulyana concentrated when confronted with events that had recently disturbed her. At the last meeting on this topic, we discussed and planned Ulyana's trip to the medical center for blood donation. This was to happen for the first time in three years. And for the first time in fifteen years - with a sense of self-confidence. nine0003

The study of each of these cases took 1-2 sessions. After two months of work, we parted for the summer holidays. Upon her return, Ulyana said that something had happened in the last sessions, “it clicked me.” Now, when one of her classmates made rude jokes about dead people or open wounds, she could already smile. The intrinsic motivation of the new behavior was supported by the idea: “This is not happening to me. Everything is fine". In our work, we paid special attention to the sensations in the hands: very gradually we went from a feeling of weakness and numbness in the fingers to a feeling of strength in the palms. It was on this feeling that Ulyana concentrated when confronted with events that had recently disturbed her. At the last meeting on this topic, we discussed and planned Ulyana's trip to the medical center for blood donation. This was to happen for the first time in three years. And for the first time in fifteen years - with a sense of self-confidence. nine0003

So how does psychological trauma affect our daily lives? This is an experience that imposes certain limitations. Just as physical trauma limits the movement of a limb, psychological trauma limits the range of our emotional responses. In a situation where it would be possible to experience joy or pride, we experience fear or shame due to "traumatic inertia". Instead of curiosity to try something new - the fear of making a mistake and already in advance the guilt that it will not work out as it should. In psychotherapy, we return to the experience, which was not lived to the end, and try to reduce its impact on our lives. EMDR is a good way to speed up this process. nine0003

Just as physical trauma limits the movement of a limb, psychological trauma limits the range of our emotional responses. In a situation where it would be possible to experience joy or pride, we experience fear or shame due to "traumatic inertia". Instead of curiosity to try something new - the fear of making a mistake and already in advance the guilt that it will not work out as it should. In psychotherapy, we return to the experience, which was not lived to the end, and try to reduce its impact on our lives. EMDR is a good way to speed up this process. nine0003

Coordinates for communication with the authors:

[email protected] - Vorodollya Natalya Viktorovna,

[email protected] - Simonova Olesya