Autism lack of empathy

Autism, Asperger's, and Empathy: Know the Facts

Autism, Asperger's, and Empathy: Know the Facts | Psych Central- Conditions

- Featured

- Addictions

- Anxiety Disorder

- ADHD

- Bipolar Disorder

- Depression

- PTSD

- Schizophrenia

- Articles

- Adjustment Disorder

- Agoraphobia

- Borderline Personality Disorder

- Childhood ADHD

- Dissociative Identity Disorder

- Narcissistic Personality Disorder

- Narcolepsy

- Oppositional Defiant Disorder

- Panic Attack

- Postpartum Depression

- Schizoaffective Disorder

- Seasonal Affective Disorder

- Sex Addiction

- Specific Phobias

- Teenage Depression

- Trauma

- Featured

- Discover

- Wellness Topics

- Black Mental Health

- Grief

- Emotional Health

- Sex & Relationships

- Trauma

- Understanding Therapy

- Workplace Mental Health

- Original Series

- My Life with OCD

- Caregivers Chronicles

- Empathy at Work

- Sex, Love & All of the Above

- Parent Central

- Mindful Moment

- News & Events

- Mental Health News

- COVID-19

- Live Town Hall: Mental Health in Focus

- Podcasts

- Inside Mental Health

- Inside Schizophrenia

- Inside Bipolar

- Wellness Topics

- Quizzes

- Conditions

- ADHD Symptoms Quiz

- Anxiety Symptoms Quiz

- Autism Quiz: Family & Friends

- Autism Symptoms Quiz

- Bipolar Disorder Quiz

- Borderline Personality Test

- Childhood ADHD Quiz

- Depression Symptoms Quiz

- Eating Disorder Quiz

- Narcissim Symptoms Test

- OCD Symptoms Quiz

- Psychopathy Test

- PTSD Symptoms Quiz

- Schizophrenia Quiz

- Lifestyle

- Attachment Style Quiz

- Career Test

- Do I Need Therapy Quiz?

- Domestic Violence Screening Quiz

- Emotional Type Quiz

- Loneliness Quiz

- Parenting Style Quiz

- Personality Test

- Relationship Quiz

- Stress Test

- What's Your Sleep Like?

- Conditions

- Resources

- Treatment & Support

- Find Support

- Suicide Prevention

- Drugs & Medications

- Find a Therapist

- Treatment & Support

Medically reviewed by Alex Klein, PsyD — By Kimberly Drake — Updated on June 29, 2021

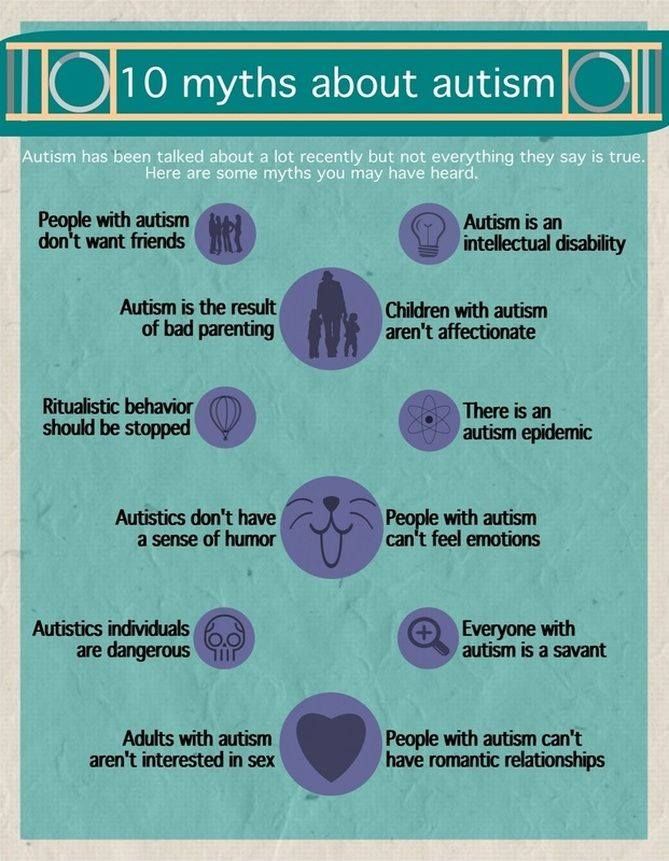

One of the biggest misconceptions about autistic people is that they lack empathy. Is there any truth to this belief?

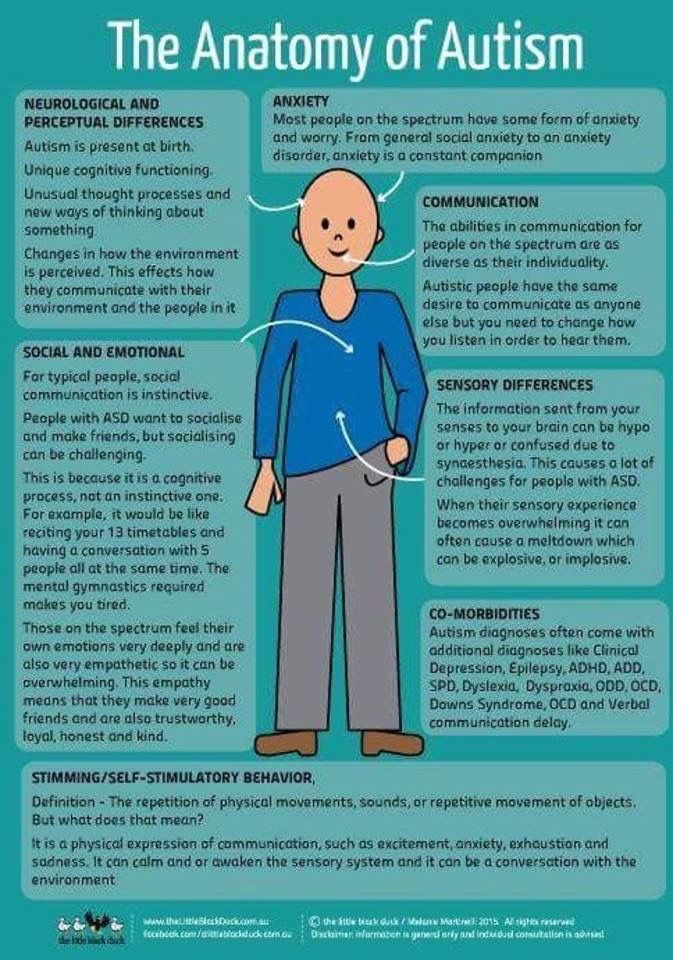

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a developmental condition characterized by social, communication, and behavioral differences.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in 8-year-old children, an estimated 1 in 54 was identified as having ASD in 2016.

Autistic disorder, pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS), and Asperger’s syndrome were once separately diagnosed disorders. They now fall under the diagnosis of ASD in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Still, some autistic people prefer to identify as either autistic or having Asperger’s.

One of the hallmarks of ASD is difficulties in social communication. This may manifest as challenges relating with others, showing little interest in other people, and difficulties with receptive and expressive language.

But do these challenges mean an autistic person can’t be empathetic?

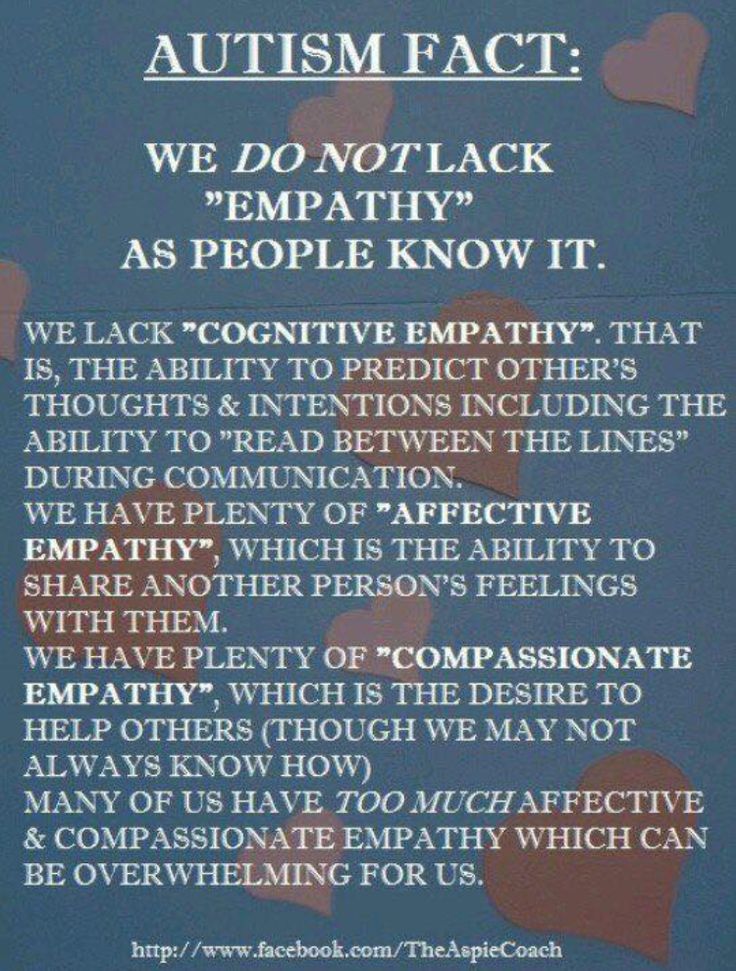

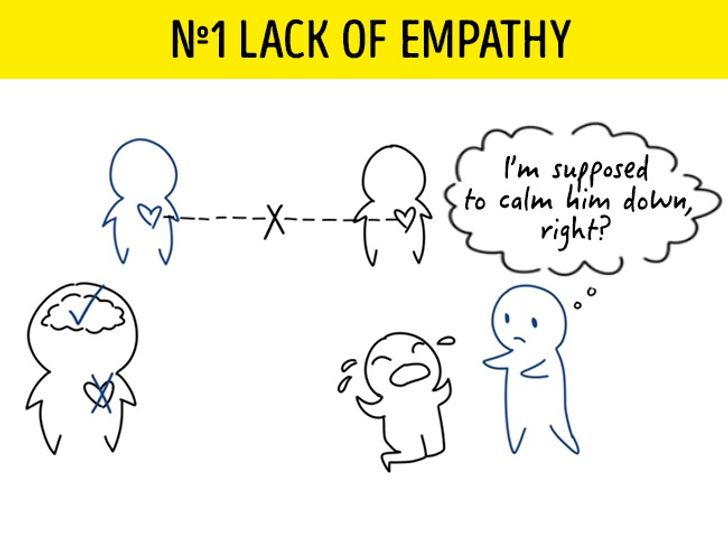

Research into autism and empathy has evolved over the years. Initially, it was thought that the absence of empathy was a characteristic found in all autistic people. However, we now know this trait exists on a spectrum in people with ASD, just as it does in neurotypical individuals.

Initially, it was thought that the absence of empathy was a characteristic found in all autistic people. However, we now know this trait exists on a spectrum in people with ASD, just as it does in neurotypical individuals.

Autistic people think differently, which can be one of their many strengths. Yet, because of this, some of their social interactions and behaviors are often misunderstood.

This can cause some people to perceive their methods of interacting and behaviors as a lack of empathy.

For example, an autistic person may seem unaware when others are experiencing emotional distress or respond inappropriately in a social situation.

To a person who isn’t autistic, these behaviors may come across as cold or harsh, leading them to believe autistic people are not empathetic.

Research from 2018 has shown that autistic people may have difficulties with cognitive empathy (recognizing another person’s emotional state) but not affective empathy (the ability to feel another’s emotional state and a drive to respond to it).

For example, they may see someone struggling to carry a load of groceries yet not realize they may need help (cognitive empathy). However, they might notice the person has become upset about it and ask why (affective empathy).

Empathy also requires the social communication skill of “reading between the lines” and deciphering how another person may feel in a situation. For autistic individuals, this may be challenging due to a tendency to think literally.

For instance, if you were to ask an autistic person, “Do you like my new haircut?” and they don’t care for it, they may say no without understanding how that response may make you feel.

So, perhaps it’s the combination of social difficulties and deficits in cognitive empathy that may create the impression autistic people aren’t empathetic. When in reality, they are — it just presents in ways that may not meet society’s expectations.

According to Eric Mikoleit, director of Lakeland STAR School/Academy — a charter school in Minocqua, Wisconsin, that specializes in educating autistic students and diverse learners, “social communication barriers, narrow interests, and attention to detail” are some of the reasons autistic people may have difficulties expressing empathy.

But, he says, they do have empathy — however, the “levels of empathy vary significantly among individuals.”

Autistic people often need direct instruction on identifying the emotional states of others and learning to label their own feelings.

Mikoleit says these skills can be enhanced in autistic students by using modeling, teaching them how to recognize and label the emotions of others, and the actions they must take in response to those emotions.

He says there are curriculum plans specifically designed to help with teaching these skills.

According to a meta-analysis, around 50% of autistic people also have alexithymia — a condition characterized by difficulties with understanding and articulating one’s emotions, including empathy. So, the coexistence of this condition may partly explain the misconception that all autistic people lack empathy.

However, a 2020 research report indicates that it’s the presence of alexithymia and not autism that impacts attachments to others, including their parents. Though attachment and empathy aren’t the same, they are related.

Though attachment and empathy aren’t the same, they are related.

Further studies suggest the deficits in emotional facial expression often thought of as ASD-specific may actually be due to alexithymia and not autism.

Still, while these studies may offer some insight, it’s unknown just how much alexithymia contributes to the differences in empathy among autistic individuals.

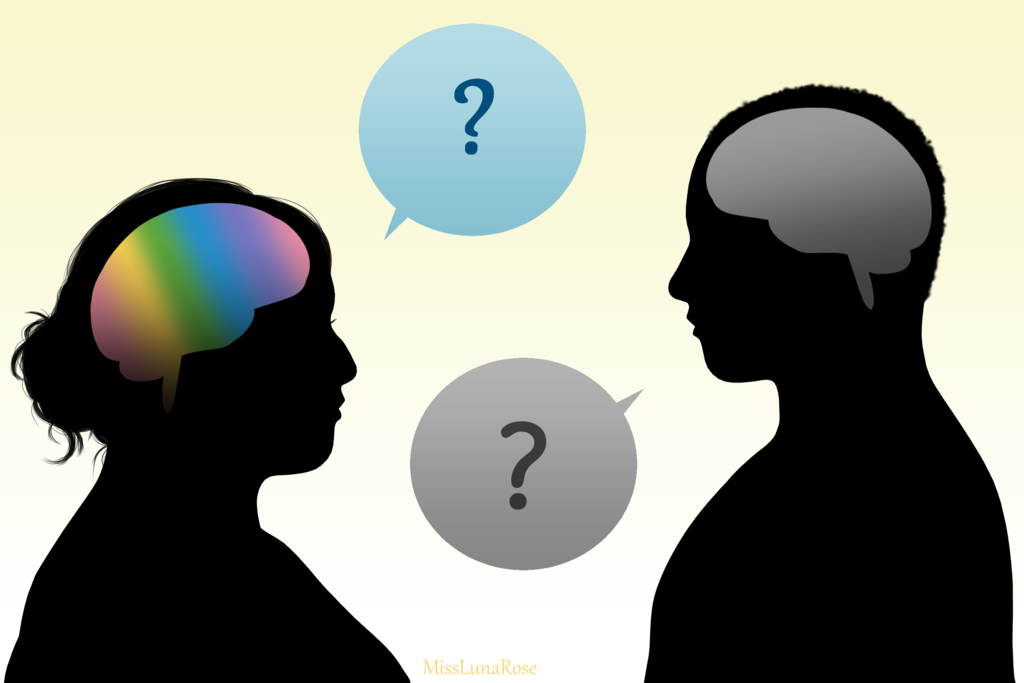

Another reason people may think autistic individuals lack empathy is because of a mismatch in communication between autistic and neurotypical people.

Research suggests that when two autistic individuals interact, they have the same level of rapport as two neurotypical people. However, when an autistic person interacts with a non-autistic individual, there is a tendency for miscommunication.

Also, other research suggests that recognizing facial emotional expressions can sometimes be a challenge for someone with ASD. And because people with ASD might not display many facial expressions themselves, it can be difficult for neurotypical people to read their emotional state.

This may cause the neurotypical person to think the autistic person lacks empathy. When in reality, the neurotypical person also lacks an empathetic understanding of the autistic person’s perspective.

This double empathy problem theory highlights the need for greater understanding and acceptance of autism. It also indicates a need for more understanding of how an autistic person thinks and feels.

Levels of empathy vary significantly among all people, including those with ASD. For autistic individuals who also have alexithymia, understanding empathy may be more of a challenge.

But for most, the differences in thinking patterns, social communication, and behaviors associated with ASD may be why some folks mistakenly believe an autistic person lacks empathy.

Helping someone with ASD learn to recognize the emotional state of others through direct instruction is one way to enhance their ability to empathize with others effectively.

However, neurotypical people can also be a part of this solution by learning how autistic individuals think, feel, and communicate.

Approaching empathy in this way could perhaps bridge the communication gap and foster the acceptance and understanding autistic people deserve.

For more information, the following organizations offer resources and support for the autism community:

- Autism Society of America

- Autism Self Advocacy Network

- Autistic Women & Nonbinary Network

- Autism Research Institute

Last medically reviewed on June 29, 2021

9 sourcescollapsed

- Autism spectrum disorder. (2020).

cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/features/new-asd-prevalence-numbers-show-gaps-are-closing.html - Brewer R, et al. (2016). Can neurotypical individuals read autistic facial expressions? Atypical production of emotional facial expressions in autism spectrum disorders.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4975602/ - Cook R, et al. (2013). Alexithymia, not autism, predicts poor recognition of emotional facial expressions.

journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0956797612463582 - DeThorne LS. (2020). Revealing the double empathy problem.

leader.pubs.asha.org/doi/10.1044/leader.FTR2.25042020.58 - Fletcher-Watson S, et al. (2019). Autism and empathy: What are the real links?

journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1362361319883506 - Giannotti M, et al. (2020). Alexithymia, not autism spectrum disorder, predicts perceived attachment to parents in school-age children.

frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00332/full - Kinnaird E, et al. (2018). Investigating alexithymia in autism: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6331035/ - Mikoleit E. (2021). Personal Interview.

- Warrier V, et al. (2018). Genome-wide analyses of self-reported empathy: correlations with autism, schizophrenia, and anorexia nervosa.

nature.com/articles/s41398-017-0082-6

FEEDBACK:

Medically reviewed by Alex Klein, PsyD — By Kimberly Drake — Updated on June 29, 2021

RELATED

All About Autism

What Are the Symptoms of Autism Spectrum Disorder?

Asperger’s vs.

Autism: What Exactly Is the Difference?

Autism: What Exactly Is the Difference?How Is Autism Diagnosed?

Autism Fact Sheet: What Should I Know About Autism Spectrum Disorder?

Read this next

All About Autism

Medically reviewed by Alexander Klein, PsyD

Our complete guide to autism and its symptoms, causes, diagnosis, and management. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder that…

READ MORE

What Are the Symptoms of Autism Spectrum Disorder?

Medically reviewed by Timothy J. Legg, PhD, PsyD, CRNP, ACRN, CPH

Autism symptoms are actually differences in sensory, communication, and behavior patterns. Here's why.

READ MORE

Asperger’s vs. Autism: What Exactly Is the Difference?

Medically reviewed by Akilah Reynolds, PhD

Asperger's syndrome and autism (ASD) are different diagnoses, but if you've guessed that there's a lot of overlap, you're also right.

You can learn…

You can learn…READ MORE

How Is Autism Diagnosed?

Medically reviewed by Alexander Klein, PsyD

Autism is diagnosed based on shared behaviors and ways of communicating. But with that said, every person with autism is different. Learn about…

READ MORE

Autism Fact Sheet: What Should I Know About Autism Spectrum Disorder?

Medically reviewed by Alexander Klein, PsyD

If you want to learn more about autism spectrum disorder or what it means to be autistic, here are some key facts to get you started.

READ MORE

What Disorders Are Related to Autism?

Medically reviewed by Nathan Greene, PsyD

If you're autistic, it's fairly common to also live with another medical, neurodevelopmental, or genetic condition. Learn about autism-related…

READ MORE

What Causes Autism Spectrum Disorder?

Medically reviewed by Alexander Klein, PsyD

Autism is complex.

While your genes may interact with your biology and environment to cause autism, there's more to it than that.

While your genes may interact with your biology and environment to cause autism, there's more to it than that.READ MORE

What Causes Asperger’s Syndrome?

Medically reviewed by Nicole Washington, DO, MPH

Most researchers agree that a complex combo of genetics, environment, and how they interact — called epigenetics — is at the root of Asperger's…

READ MORE

Growing Up Autistic: How Do I Make the Leap to Adulthood?

Medically reviewed by Jeffrey Ditzell, DO

Each autistic adult is different. Learn how you can manage school, work, and more with whichever level of support works best for you.

READ MORE

Symptoms and Signs of Asperger’s Syndrome

Medically reviewed by Alexander Klein, PsyD

Signs of Asperger's syndrome can vary from person to person but these are the most common ones in both adults and children.

READ MORE

Autism, Asperger's, and Empathy: Know the Facts

Autism, Asperger's, and Empathy: Know the Facts | Psych Central- Conditions

- Featured

- Addictions

- Anxiety Disorder

- ADHD

- Bipolar Disorder

- Depression

- PTSD

- Schizophrenia

- Articles

- Adjustment Disorder

- Agoraphobia

- Borderline Personality Disorder

- Childhood ADHD

- Dissociative Identity Disorder

- Narcissistic Personality Disorder

- Narcolepsy

- Oppositional Defiant Disorder

- Panic Attack

- Postpartum Depression

- Schizoaffective Disorder

- Seasonal Affective Disorder

- Sex Addiction

- Specific Phobias

- Teenage Depression

- Trauma

- Featured

- Discover

- Wellness Topics

- Black Mental Health

- Grief

- Emotional Health

- Sex & Relationships

- Trauma

- Understanding Therapy

- Workplace Mental Health

- Original Series

- My Life with OCD

- Caregivers Chronicles

- Empathy at Work

- Sex, Love & All of the Above

- Parent Central

- Mindful Moment

- News & Events

- Mental Health News

- COVID-19

- Live Town Hall: Mental Health in Focus

- Podcasts

- Inside Mental Health

- Inside Schizophrenia

- Inside Bipolar

- Wellness Topics

- Quizzes

- Conditions

- ADHD Symptoms Quiz

- Anxiety Symptoms Quiz

- Autism Quiz: Family & Friends

- Autism Symptoms Quiz

- Bipolar Disorder Quiz

- Borderline Personality Test

- Childhood ADHD Quiz

- Depression Symptoms Quiz

- Eating Disorder Quiz

- Narcissim Symptoms Test

- OCD Symptoms Quiz

- Psychopathy Test

- PTSD Symptoms Quiz

- Schizophrenia Quiz

- Lifestyle

- Attachment Style Quiz

- Career Test

- Do I Need Therapy Quiz?

- Domestic Violence Screening Quiz

- Emotional Type Quiz

- Loneliness Quiz

- Parenting Style Quiz

- Personality Test

- Relationship Quiz

- Stress Test

- What's Your Sleep Like?

- Conditions

- Resources

- Treatment & Support

- Find Support

- Suicide Prevention

- Drugs & Medications

- Find a Therapist

- Treatment & Support

Medically reviewed by Alex Klein, PsyD — By Kimberly Drake — Updated on June 29, 2021

One of the biggest misconceptions about autistic people is that they lack empathy. Is there any truth to this belief?

Is there any truth to this belief?

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a developmental condition characterized by social, communication, and behavioral differences.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in 8-year-old children, an estimated 1 in 54 was identified as having ASD in 2016.

Autistic disorder, pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS), and Asperger’s syndrome were once separately diagnosed disorders. They now fall under the diagnosis of ASD in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Still, some autistic people prefer to identify as either autistic or having Asperger’s.

One of the hallmarks of ASD is difficulties in social communication. This may manifest as challenges relating with others, showing little interest in other people, and difficulties with receptive and expressive language.

But do these challenges mean an autistic person can’t be empathetic?

Research into autism and empathy has evolved over the years. Initially, it was thought that the absence of empathy was a characteristic found in all autistic people. However, we now know this trait exists on a spectrum in people with ASD, just as it does in neurotypical individuals.

Initially, it was thought that the absence of empathy was a characteristic found in all autistic people. However, we now know this trait exists on a spectrum in people with ASD, just as it does in neurotypical individuals.

Autistic people think differently, which can be one of their many strengths. Yet, because of this, some of their social interactions and behaviors are often misunderstood.

This can cause some people to perceive their methods of interacting and behaviors as a lack of empathy.

For example, an autistic person may seem unaware when others are experiencing emotional distress or respond inappropriately in a social situation.

To a person who isn’t autistic, these behaviors may come across as cold or harsh, leading them to believe autistic people are not empathetic.

Research from 2018 has shown that autistic people may have difficulties with cognitive empathy (recognizing another person’s emotional state) but not affective empathy (the ability to feel another’s emotional state and a drive to respond to it).

For example, they may see someone struggling to carry a load of groceries yet not realize they may need help (cognitive empathy). However, they might notice the person has become upset about it and ask why (affective empathy).

Empathy also requires the social communication skill of “reading between the lines” and deciphering how another person may feel in a situation. For autistic individuals, this may be challenging due to a tendency to think literally.

For instance, if you were to ask an autistic person, “Do you like my new haircut?” and they don’t care for it, they may say no without understanding how that response may make you feel.

So, perhaps it’s the combination of social difficulties and deficits in cognitive empathy that may create the impression autistic people aren’t empathetic. When in reality, they are — it just presents in ways that may not meet society’s expectations.

According to Eric Mikoleit, director of Lakeland STAR School/Academy — a charter school in Minocqua, Wisconsin, that specializes in educating autistic students and diverse learners, “social communication barriers, narrow interests, and attention to detail” are some of the reasons autistic people may have difficulties expressing empathy.

But, he says, they do have empathy — however, the “levels of empathy vary significantly among individuals.”

Autistic people often need direct instruction on identifying the emotional states of others and learning to label their own feelings.

Mikoleit says these skills can be enhanced in autistic students by using modeling, teaching them how to recognize and label the emotions of others, and the actions they must take in response to those emotions.

He says there are curriculum plans specifically designed to help with teaching these skills.

According to a meta-analysis, around 50% of autistic people also have alexithymia — a condition characterized by difficulties with understanding and articulating one’s emotions, including empathy. So, the coexistence of this condition may partly explain the misconception that all autistic people lack empathy.

However, a 2020 research report indicates that it’s the presence of alexithymia and not autism that impacts attachments to others, including their parents. Though attachment and empathy aren’t the same, they are related.

Though attachment and empathy aren’t the same, they are related.

Further studies suggest the deficits in emotional facial expression often thought of as ASD-specific may actually be due to alexithymia and not autism.

Still, while these studies may offer some insight, it’s unknown just how much alexithymia contributes to the differences in empathy among autistic individuals.

Another reason people may think autistic individuals lack empathy is because of a mismatch in communication between autistic and neurotypical people.

Research suggests that when two autistic individuals interact, they have the same level of rapport as two neurotypical people. However, when an autistic person interacts with a non-autistic individual, there is a tendency for miscommunication.

Also, other research suggests that recognizing facial emotional expressions can sometimes be a challenge for someone with ASD. And because people with ASD might not display many facial expressions themselves, it can be difficult for neurotypical people to read their emotional state.

This may cause the neurotypical person to think the autistic person lacks empathy. When in reality, the neurotypical person also lacks an empathetic understanding of the autistic person’s perspective.

This double empathy problem theory highlights the need for greater understanding and acceptance of autism. It also indicates a need for more understanding of how an autistic person thinks and feels.

Levels of empathy vary significantly among all people, including those with ASD. For autistic individuals who also have alexithymia, understanding empathy may be more of a challenge.

But for most, the differences in thinking patterns, social communication, and behaviors associated with ASD may be why some folks mistakenly believe an autistic person lacks empathy.

Helping someone with ASD learn to recognize the emotional state of others through direct instruction is one way to enhance their ability to empathize with others effectively.

However, neurotypical people can also be a part of this solution by learning how autistic individuals think, feel, and communicate.

Approaching empathy in this way could perhaps bridge the communication gap and foster the acceptance and understanding autistic people deserve.

For more information, the following organizations offer resources and support for the autism community:

- Autism Society of America

- Autism Self Advocacy Network

- Autistic Women & Nonbinary Network

- Autism Research Institute

Last medically reviewed on June 29, 2021

9 sourcescollapsed

- Autism spectrum disorder. (2020).

cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/features/new-asd-prevalence-numbers-show-gaps-are-closing.html - Brewer R, et al. (2016). Can neurotypical individuals read autistic facial expressions? Atypical production of emotional facial expressions in autism spectrum disorders.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4975602/ - Cook R, et al. (2013). Alexithymia, not autism, predicts poor recognition of emotional facial expressions.

journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0956797612463582 - DeThorne LS. (2020). Revealing the double empathy problem.

leader.pubs.asha.org/doi/10.1044/leader.FTR2.25042020.58 - Fletcher-Watson S, et al. (2019). Autism and empathy: What are the real links?

journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1362361319883506 - Giannotti M, et al. (2020). Alexithymia, not autism spectrum disorder, predicts perceived attachment to parents in school-age children.

frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00332/full - Kinnaird E, et al. (2018). Investigating alexithymia in autism: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6331035/ - Mikoleit E. (2021). Personal Interview.

- Warrier V, et al. (2018). Genome-wide analyses of self-reported empathy: correlations with autism, schizophrenia, and anorexia nervosa.

nature.com/articles/s41398-017-0082-6

FEEDBACK:

Medically reviewed by Alex Klein, PsyD — By Kimberly Drake — Updated on June 29, 2021

RELATED

All About Autism

What Are the Symptoms of Autism Spectrum Disorder?

Asperger’s vs.

Autism: What Exactly Is the Difference?

Autism: What Exactly Is the Difference?How Is Autism Diagnosed?

Autism Fact Sheet: What Should I Know About Autism Spectrum Disorder?

Read this next

All About Autism

Medically reviewed by Alexander Klein, PsyD

Our complete guide to autism and its symptoms, causes, diagnosis, and management. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder that…

READ MORE

What Are the Symptoms of Autism Spectrum Disorder?

Medically reviewed by Timothy J. Legg, PhD, PsyD, CRNP, ACRN, CPH

Autism symptoms are actually differences in sensory, communication, and behavior patterns. Here's why.

READ MORE

Asperger’s vs. Autism: What Exactly Is the Difference?

Medically reviewed by Akilah Reynolds, PhD

Asperger's syndrome and autism (ASD) are different diagnoses, but if you've guessed that there's a lot of overlap, you're also right.

You can learn…

You can learn…READ MORE

How Is Autism Diagnosed?

Medically reviewed by Alexander Klein, PsyD

Autism is diagnosed based on shared behaviors and ways of communicating. But with that said, every person with autism is different. Learn about…

READ MORE

Autism Fact Sheet: What Should I Know About Autism Spectrum Disorder?

Medically reviewed by Alexander Klein, PsyD

If you want to learn more about autism spectrum disorder or what it means to be autistic, here are some key facts to get you started.

READ MORE

What Disorders Are Related to Autism?

Medically reviewed by Nathan Greene, PsyD

If you're autistic, it's fairly common to also live with another medical, neurodevelopmental, or genetic condition. Learn about autism-related…

READ MORE

What Causes Autism Spectrum Disorder?

Medically reviewed by Alexander Klein, PsyD

Autism is complex.

While your genes may interact with your biology and environment to cause autism, there's more to it than that.

While your genes may interact with your biology and environment to cause autism, there's more to it than that.READ MORE

What Causes Asperger’s Syndrome?

Medically reviewed by Nicole Washington, DO, MPH

Most researchers agree that a complex combo of genetics, environment, and how they interact — called epigenetics — is at the root of Asperger's…

READ MORE

Growing Up Autistic: How Do I Make the Leap to Adulthood?

Medically reviewed by Jeffrey Ditzell, DO

Each autistic adult is different. Learn how you can manage school, work, and more with whichever level of support works best for you.

READ MORE

Symptoms and Signs of Asperger’s Syndrome

Medically reviewed by Alexander Klein, PsyD

Signs of Asperger's syndrome can vary from person to person but these are the most common ones in both adults and children.

READ MORE

Empathy and Autism: An Autistic Perspective

6/12/13

Why Other Expressions of Feelings and Experiences Should Not Be Confused with Indifference to Others

Author: Deborah Lipsky

Deborah Lipsky, adult female with high functioning autism, lecturer, author of two books on autism tantrums, farmer, history buff.

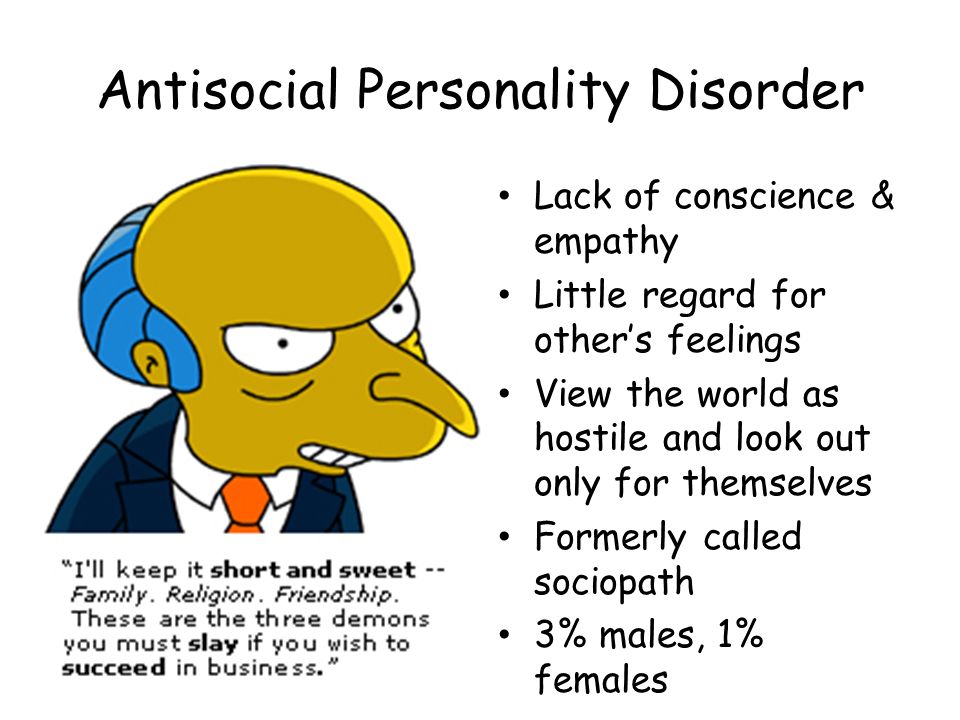

It is often said that autistic people lack empathy. It is often claimed that they lack a theory of mind (understanding what the other person is thinking and feeling). Why? They are constantly told that they hurt other people's feelings, think only about themselves and cannot look at the situation through the eyes of another person. They are called narcissistic, self-centered arrogant people who are incapable of feelings.

Schools and churches are the main institutions that teach common values and social norms, where neurotypical [non-autistic] people understand the importance of a society based on conformity. Schools are one of the first places where the socialization of neurotypicals begins, for which one of the main motives is to “fit in”. Nobody wants to be an outcast. The social development of autistics does not coincide with the development of neurotypicals. They are not interested in being the same as everyone else, or seeking acceptance from others through conformism. The main motivation of neurotypicals is to fit into the environment and not become an outcast. When autistic people don't "fit in" it's not a problem for them. Bullying, ridicule and violence in general are problems. According to the unwritten rules, it is precisely such punishments that await those who do not fit in. After autistics are exposed to such treatment for a long time, they realize that there is some expected uniformity of neurotypicals in dress, thoughts and actions. Neurotypicals distort the truth and mislead in order to fit in. Autistic people tend to avoid their peers.

Schools are one of the first places where the socialization of neurotypicals begins, for which one of the main motives is to “fit in”. Nobody wants to be an outcast. The social development of autistics does not coincide with the development of neurotypicals. They are not interested in being the same as everyone else, or seeking acceptance from others through conformism. The main motivation of neurotypicals is to fit into the environment and not become an outcast. When autistic people don't "fit in" it's not a problem for them. Bullying, ridicule and violence in general are problems. According to the unwritten rules, it is precisely such punishments that await those who do not fit in. After autistics are exposed to such treatment for a long time, they realize that there is some expected uniformity of neurotypicals in dress, thoughts and actions. Neurotypicals distort the truth and mislead in order to fit in. Autistic people tend to avoid their peers.

Due to their monolithic nature, it is difficult for autistic people to integrate information from different sources. For example, they may understand words but miss non-verbal cues.

For example, they may understand words but miss non-verbal cues.

In addition, autistics usually perceive only narrow definitions of the words they hear. They miss all communication that is not literal. They never develop the skills to recognize hidden signs of tension in communication. For example, a person comes in and doesn't say a word because he is overwhelmed by something. This person has a "sad expression" on his face, or he sighs from time to time. Asked what happened, he says "nothing" even though his body language says the exact opposite. An autistic person hears only the word "nothing" and believes that everything is in order, because the hidden body language is not available to him.

Deborah Lipsky during the historical reconstruction.

Autistic people may value honesty over political correctness. If it is impossible to be honest and polite at the same time, most autistic people will choose honesty. This leads them to say things that other people find offensive. Sometimes they don't know about unwritten social conventions and codes, because you learn these rules while communicating with peers, and not from books.

Sometimes they don't know about unwritten social conventions and codes, because you learn these rules while communicating with peers, and not from books.

Due to their interest in conformity, neurotypicals are remarkably similar to each other. It is likely that the ability to know what another person is thinking or feeling, even if he or she does not say it, is not a sixth sense at all, but merely a projection of one's own feelings and thoughts onto the other person. This leads to stereotyping, but it's a pretty reliable way to predict other people's behavior. However, it is useless for determining the thoughts and feelings of autistic people.

Neurotypicals often misinterpret the actions or reactions of an autistic person as a lack of concern for the other person's feelings. The irony is that when neurotypicals attribute a lack of empathy to autistics, they themselves show a lack of empathy.

The notion that autistic people lack empathy is wrong. We may appear indifferent and even heartless to other people's problems, but only because we react differently than non-autistic people.

Deborah Lipsky during a lecture on prevention and response to tantrums in autism.

Empathy manifests itself in different ways. For example, as a licensed forest attendant, this was the first time I nursed a bat last winter. I was initially creepy from years of watching Dracula movies and had a hard time because of the internalized stereotypes that bats are evil. When I told other people that I was working with a bat, they started talking terrible and false stereotypes about bats, they believed that they were of no use to anyone. These people relied on myths and "grandmother's tales." As soon as I realized that the poor bat was being judged unfairly: not by its real qualities, but by folklore, I wanted to protect it, and my fear evaporated. I was able to identify (empathize) with the mouse because I know what it's like to be the target of other people's negative stereotypes.

The same thing happens to me when I tell a stranger that I am autistic. I could put myself in the place of a bat. For me, this is real empathy - to understand the other from his or her point of view.

I could put myself in the place of a bat. For me, this is real empathy - to understand the other from his or her point of view.

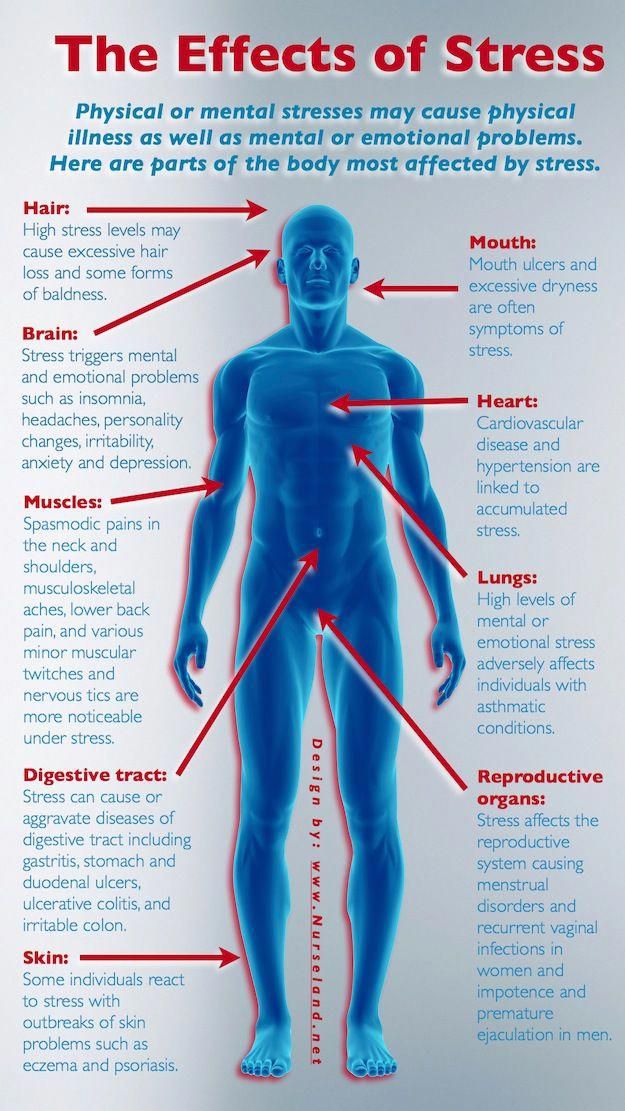

Empathy is not limited to specific emotional responses to show understanding or caring. One day my friend invited me to have lunch with her autistic son. She decided to go to a fast food restaurant because her little kid loves chicken nuggets from there. It was lunch time and I didn't feel like going there because of all the possible sensory issues that can happen in a crowded fast food place. My friend assured me that we wouldn't have to wait long in line because the service was very fast. I was also worried about the child, but decided that a friend knew better about her own son and his sensory features. I agreed with her plan because I didn't want to look "capricious" in my friend's eyes. When we entered the restaurant was packed, the noise from the crowds was deafening.

I did my best to protect myself from the noise, the bright lights, and the people who surrounded me on all sides. It was difficult for my friend to understand that even five minutes in such a place is unbearable for autistic people with sensory problems, because her own sensory experience was completely different.

It was difficult for my friend to understand that even five minutes in such a place is unbearable for autistic people with sensory problems, because her own sensory experience was completely different.

Deborah Lipsky on her tractor.

I turned to the baby and saw a pitiful look of agony. I understood how he felt because I felt the same way myself. It felt like we were the only ones for whom this experience was torture. The child covered his ears with his hands and began to scream loudly, and then burst into tears. In just a few seconds, he reached a real hysteria.

I was filled with empathy because I knew exactly how he felt. I experienced the same sensory overload, and I could easily respond in exactly the same way. My friend froze in place because she did not know what caused this reaction and she was uncomfortable in front of other visitors. I didn’t say a word or show any emotion, he picked up the baby in my arms and ran out of the building as soon as possible so that we both could calm down. My reaction was based on empathy. However, bystanders could easily misinterpret my actions. Perhaps the observers felt empathy for the mother, and for them my actions were an attempt to relieve her of shame.

My reaction was based on empathy. However, bystanders could easily misinterpret my actions. Perhaps the observers felt empathy for the mother, and for them my actions were an attempt to relieve her of shame.

Autistic people are constantly under pressure to empathize with neurotypicals. And when we try to do this, we are often misunderstood. As a result, it's much easier for us to empathize with outcasts because we understand what it's like. It is easier for us to show empathy for animals and for people who find themselves on the margins of society. Sometimes we even feel overly strong empathy for some people. We sympathize with autistic people, as well as others who face rejection from others. We cry over the cruelty to animals and people that we ourselves could have been in.

We have emotions and feelings. We just don't express them in the same way. We laugh, we cry and we feel pain and sorrow just like everyone else. We just need a little empathy from a society that needs to recognize that there are many ways (including other than the norm) to express empathy and emotion.

Autistic Notes, Communication and Speech, First Person

Empathy and Autism: The brain is a normal organ, it can be trained

Dr. Bhishmadev Chakrabarti. Photo: facebook.com/bhismadevAt the beginning of April 2019, Moscow will host the VII International Conference “Autism. Challenges and Solutions”. This is one of the most representative international forums where scientific and practical achievements in the study of the nature of autism, the development of biomedical, psychological and behavioral methods for its correction are discussed.

One of the conference speakers is an eminent scientist, Professor of the Department of Psychology and Pathology of Speech at the University of Reading in the UK, one of the world's leading experts in empathy, Dr. Bhishmadev Chakrabarti .

First we talk about autism, and then, oddly enough, about burnout. It's all about empathy, too.

Predictability is important for an autist Photo from verywellhealth.

com

com – Dr. Chakrabarty, a lot of research, including your research team, shows that children with autism, unlike their neurotypical peers, have social stimuli generate more attention than non-social ones. When choosing between a human face and a toy, the typical one-year-old would prefer to look at the face, while an autistic toddler would be more interested in the toy. What are the biological mechanisms behind this difference in preferences?

- This is a very difficult question, and I must confess that despite years of research, I cannot give an exact answer today. I am ready, however, to share my assumptions.

First, we believe that a number of genes are altered in people with autism. These are genes that regulate the production of hormones such as oxytocin and dopamine, which are involved in the process of reward or, in other words, satisfaction from social stimuli, pleasure from them.

If a person has fewer of these molecules than necessary, or some of their interactions are disturbed, his interest in other people, in communication will be reduced.

But the molecular level is probably only part of the story.

Let's rise higher, to the level of brain functioning, and here we will see such a picture. Unlike non-social stimuli, that is, inanimate objects, social ones are complex and unpredictable.

Suppose I know you well and have a rough idea of how you look when you are happy or when you are upset, how you smile, frown, gesticulate, with what intonations you speak. But even then, you cannot be 100% predictable to me. Under certain circumstances, something new may appear in your facial expressions or voice, or familiar components may appear in an unexpected combination.

For a neurotypical person, this is not a serious problem, but for an autistic person, any unexpected signal causes anxiety.

Predictability is important to him, he needs to know in advance in what order the events of the day will unfold, it is important for him to stick to the same routes, he has developed routines, deviations from which are perceived very painfully. It is highly likely that this is why social contacts are so difficult for people with autism.

It is highly likely that this is why social contacts are so difficult for people with autism.

- It turns out that anxiety is a very important part in the symptoms of autism, and if it is somehow reduced, then this should significantly improve a person's condition.

- One important point must be taken into account here. There are implicit subgroups within the autistic group, and our hypothesis is that there is a subgroup whose key problem is precisely anxiety.

This can be modeled using a neurotypical. Let's imagine that I'm experiencing extreme anxiety about something. The activity of the corresponding neural circuits will be increased, the rest, including those responsible for communication, will be reduced, and from the outside I will look like a person who does not want any contact with other people. But in fact, this is not so, just at the moment, anxiety dampens everything else.

But there is also a subset of those people with autism who have very low social motivation per se, regardless of anxiety. So far, we only know that these subgroups differ, but what lies behind these differences remains to be explored.

So far, we only know that these subgroups differ, but what lies behind these differences remains to be explored.

Medications and psychotherapy Dr. Chakrabarti at the conference. Screenshot from youtube.com

- What do you think about the possibility of influencing anxiety and social motivation with the help of drugs? Now there are interesting studies on the use of cannabidiol in children and even methamphetamine in adults with autism, albeit in combination with psychotherapy.

- As far as cannabidiol is concerned, this drug may be useful. Judging by the published data, it reduces those manifestations of autism that are really associated with anxiety: stereotypes, aggression, self-aggression. But it will be possible to say something definitely only after large multicenter clinical trials.

As for methamphetamine in combination with psychotherapy… I would prefer to limit myself to psychotherapy if possible.

I generally believe that psychological and behavioral interventions are preferable, and drugs should be avoided. All of them have side effects, and besides, they do not always act on the exact biological mechanism that is behind anxiety.

All of them have side effects, and besides, they do not always act on the exact biological mechanism that is behind anxiety.

Very often, anxiety in autism is caused by increased sensitivity to external stimuli, visual, sound, tactile and other. A well-known fact: children with autism experience sensory overload and lose their temper in crowded noisy places, in supermarkets, at mass holidays and so on.

This can't be helped with drugs, it requires a completely different therapy that would work with how the child's brain processes the sensory impulses that come into it.

Although, of course, in some cases, when the level of anxiety is so high that it does not allow a person to function normally, medications have to be used.

ABA therapy Photo from biospectrumindia.com

– Behavioral therapy, in particular ABA, Applied Behavior Analysis, is becoming more and more popular in Russia. Do you think it can be used to teach a child empathy and communication?

– Yes, of course. It is early behavioral interventions that ultimately shape the human brain! We must not forget that the brain is the same organ as the rest of our body.

It is early behavioral interventions that ultimately shape the human brain! We must not forget that the brain is the same organ as the rest of our body.

Even if my muscles are weak, training in the gym will help me strengthen them. Maybe if I don’t have the original outstanding abilities for sports, I won’t become an Olympic champion, but by working on myself, I can still go far in this direction.

The same with the brain. Those neural circuits that work for social interaction are initially weaker than the norm in a child with autism, but this does not mean that they cannot be developed.

If you create favorable conditions for him to communicate with other people, if you teach him to understand their emotions, you train certain brain structures. At the behavioral level, you build a certain pattern of reaction to something.

For example, what to do in a situation when a person cries: what can you say to him, how else can you console him. By practicing this model, the child learns to show empathy, and at some stage he begins to experience the corresponding emotions.

Reciprocal smile Photo from cbdcanvas.com

- A number of your works are devoted to mirroring, that is, imitation of facial expressions, gestures, actions of another person in order to establish closer contact with him. While reading about this, I thought of Barry and Samantha Kaufman's "sun-rise" method. It does not belong to methods with proven effectiveness, many criticize it, although there are those who believe that it helped their children a lot in overcoming autism. Interestingly, the Kaufmans behaved exactly like this with their autistic son Ron: as soon as he began to do something, for example, rotate a round object, they immediately joined him, repeating the same action. Perhaps it is mirroring that leads in a number of cases to the success of this method?

– Indeed, mirroring is a very important part of building social interaction. The simplest example is the return smile of one person to another.

I've heard of the sun-rise method, of course, but I haven't specifically studied its protocol. However, the same principle is present, for example, in the well-known Denver Early Intervention Model.

However, the same principle is present, for example, in the well-known Denver Early Intervention Model.

What is interesting to note here. Let us take the already mentioned stereotypy among autistic children, the rotation of objects. Let's imagine a situation: a child rotates the top, mother takes another top and also starts to rotate, and thus arouses the interest of the child, falls into his field of vision. This is a good start.

And then the situation can be developed. After some time, we remove the second spinning top, the mother and child are left alone for two, and the child learns to share and follow the order. And these are already important social skills.

But here again I must return to the topic of implicit subgroups within autism. In our lab, we did a study with autistic adults. Using magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, we observed the reaction of study participants to mirroring.

Neurotypical adults showed a high level of activation of neural circuits of reward (satisfaction), participants with autism showed a low level of activation of the same circuits.

Our colleagues who have done research with autistic children have found that within groups there is a large difference in response to mirroring. Some children react positively when they see someone repeating their facial expressions and actions, while others do not like it at all. So you should always keep in mind the individual characteristics of the child.

Empathy fatigue, charity burnout Photo from sciwri.club

- I can't help but ask a question that is not related to autism, but is very important for Mercy. ru" as a charitable organization. Charity and social service are impossible without a high level of empathy, and this gives rise to the problem of burnout. Do you have any recipes for controlling your own empathy? How not to deplete your emotional resource? How, finally, not to be a victim of an unscrupulous person who exploits your empathy?

- This is a very interesting topic. We call the everyday concept of “burnout” in our work “empathy fatigue” and have been studying it for a long time.

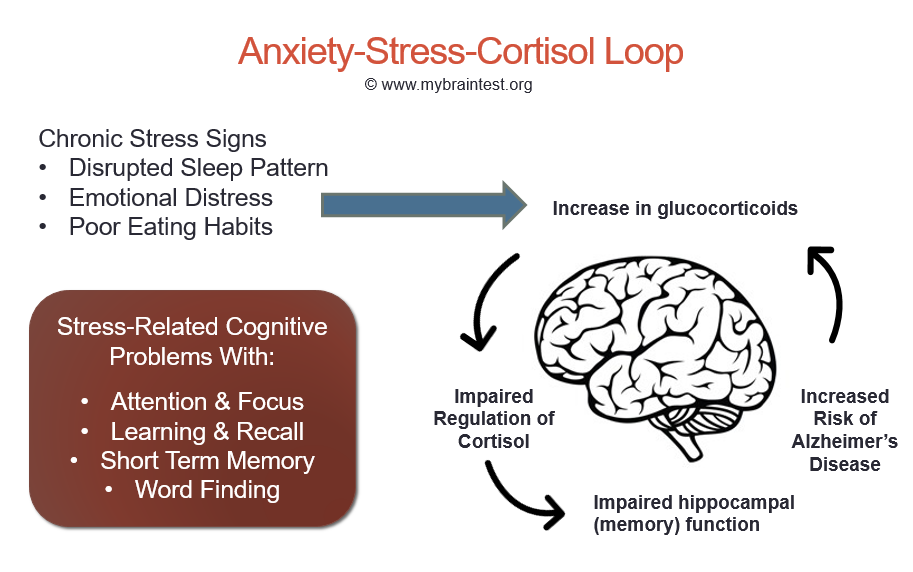

First, let's look at the components of empathy. The two most important are cognitive empathy and emotional empathy.

How does the cognitive component work?

Two days ago we had scheduled an interview for a certain time, but due to unexpected circumstances I had to ask you to reschedule it. I did not see you, the expression on your face, but I could logically assume that you would be annoyed or even angry, and, of course, I apologized. This is an example of cognitive empathy.

Emotional empathy is that I see your emotion and automatically feel the same. One person cries and another sees it, and his eyes fill with tears, although he may not know what the cause of his comrade's great upset is.

Now let's look at this situation.

A woman has a small child who cries a lot. After a while, she is in a state of extreme physical and emotional fatigue, and at some point she becomes desperate and begins to shake the child.

To those who look at this mother's behavior from the outside, it may seem that she is devoid of empathy, but the picture is exactly the opposite: a woman has too much empathy for her own child.

But this is emotional empathy, and to the extent of merging with it, while it would be nice for her to turn on cognitive empathy and ask herself the question: what about the child? Why is he crying so much? What can I do to help him?

In order to avoid burnout, it is necessary, firstly, to draw a clear boundary between yourself and another person, and secondly, learn to switch from emotional to cognitive empathy, because it is the latter that is constructive and ultimately leads to actions, useful to someone we sympathize with and want to help.

When a person is aware of the problem of possible empathy fatigue, he can resort to two strategies. The first is called "expression suppression", that is, the suppression of the expression of emotions. For example, you repeat to yourself: “You can't cry, you can't cry…”

But this is a very bad strategy, because suppressing feelings is ineffective: it never leads to the desired result.

But there is also a good strategy called "cognitive reappraisal". It consists in the fact that I do not focus on my own sympathy for the person experiencing grief, but I begin to mentally formulate the story of this person.

It consists in the fact that I do not focus on my own sympathy for the person experiencing grief, but I begin to mentally formulate the story of this person.

Why is he in emotional pain? What situation caused it? Is there any possibility to influence this situation? What can I do about it? And this strategy works.

As for the exploitation of empathy, the mechanism is clear. When we sympathize with a person in trouble, the activity of neural circuits in the brain structures responsible for emotions is greatly increased, which means that the activity of the structures of the prefrontal cortex, that is, the ability to think rationally, is suppressed. And if a person does not think rationally, it is easy to take advantage of this, deceive him, get what he would not give back in a normal situation.

In this case, too, one should first of all draw a clear boundary between the other person and oneself, and then apply the strategy of "cognitive reassessment". It is very likely that it will help to understand that they are trying to manipulate you.

How do I know if my child is a psychopath? Dr. Bhishmadev Chakrabarti. Photo: facebook.com/bhismadev

- Let's take the opposite case - a complete lack of empathy. Parents sometimes ask the question, how do I know if my child is a psychopath? Are there any signs by which we could isolate such a child and start early intervention?

- I would like to give a clear answer to this question, but, unfortunately, there are no clear criteria.

Let's say a child often fights at school. This can be evidence of a variety of problems, it does not necessarily have to do with a lack of empathy.

One of the early signs can be considered that the child manipulates others, but even here it is very difficult to draw a line in any particular place.

Children often go for tricks, and besides, manipulation in our society is quite legitimized in many areas. For example, we are constantly being manipulated into buying something, but we accept it.

Probably the only more or less reliable criterion is that the child constantly and consistently seeks to harm others in one form or another. In this case, he certainly needs professional attention.

- In conclusion, I want to ask you something. It seems to me that now in the world empathy is recognized as one of the main socio-cultural values. Much is said and written about the importance of mutual empathy among people of different cultures and social groups. It is interesting that this year the Oscar was awarded to the film Green Book - after all, it is about this, although purely cinematically, it may have been inferior to other nominees. Are you happy with this?

– On the one hand, yes, it pleases. And at the same time, I am against placing anything, even empathy, on an unattainable height. As soon as a very high pedestal appears, someone immediately wants to tear it down.

Empathy is our ability to understand the emotions of others and respond to them appropriately.