Adverse childhood event

Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences |Violence Prevention|Injury Center|CDC

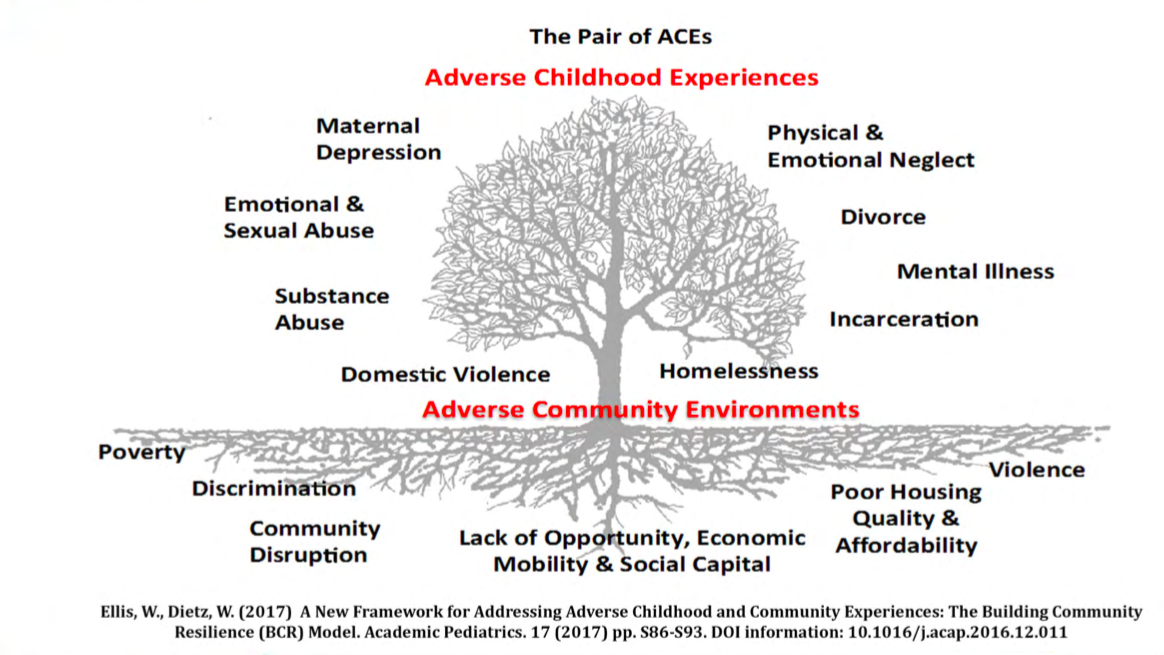

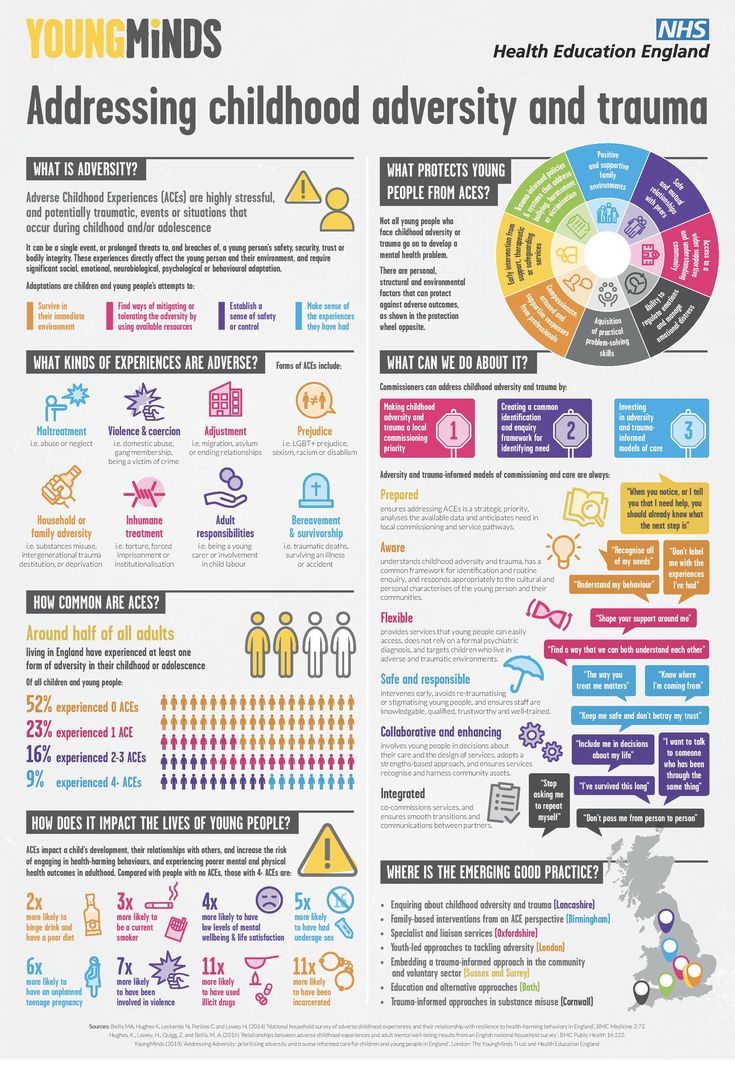

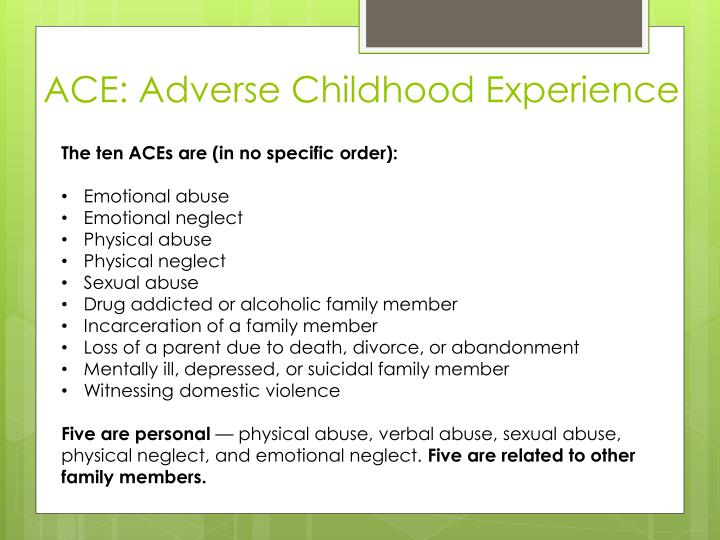

Adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs, are potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood (0-17 years). For example:

- experiencing violence, abuse, or neglect

- witnessing violence in the home or community

- having a family member attempt or die by suicide

Also included are aspects of the child’s environment that can undermine their sense of safety, stability, and bonding, such as growing up in a household with:

- substance use problems

- mental health problems

- instability due to parental separation or household members being in jail or prison

Please note the examples above are not a complete list of adverse experiences. Many other traumatic experiences could impact health and wellbeing.

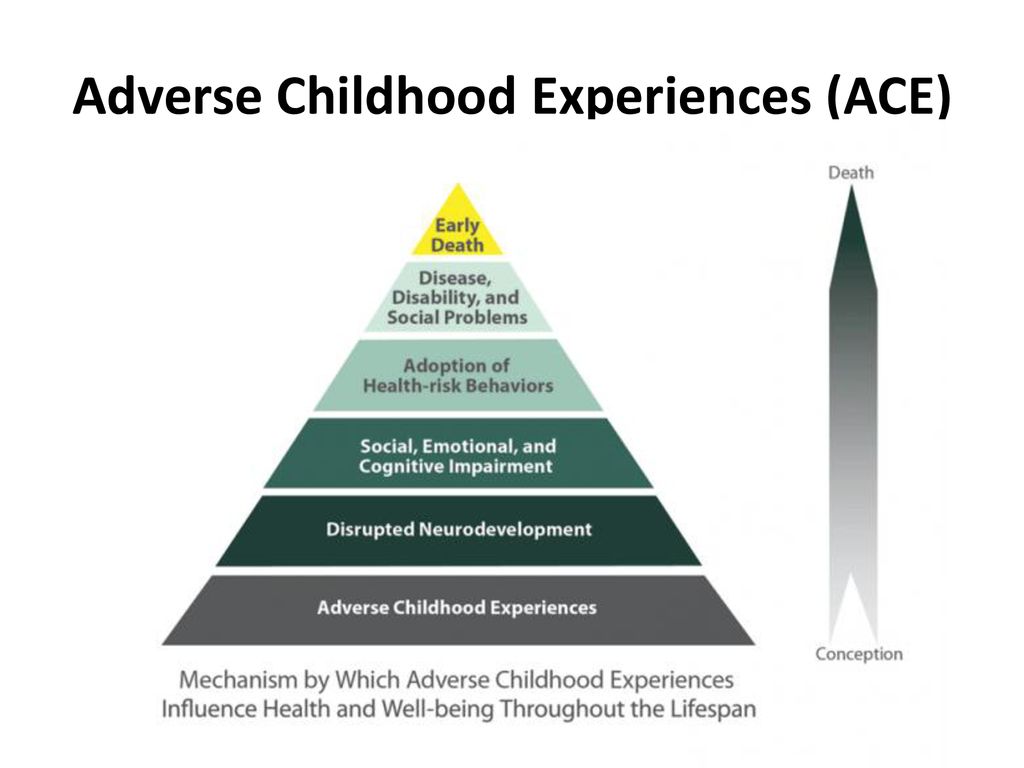

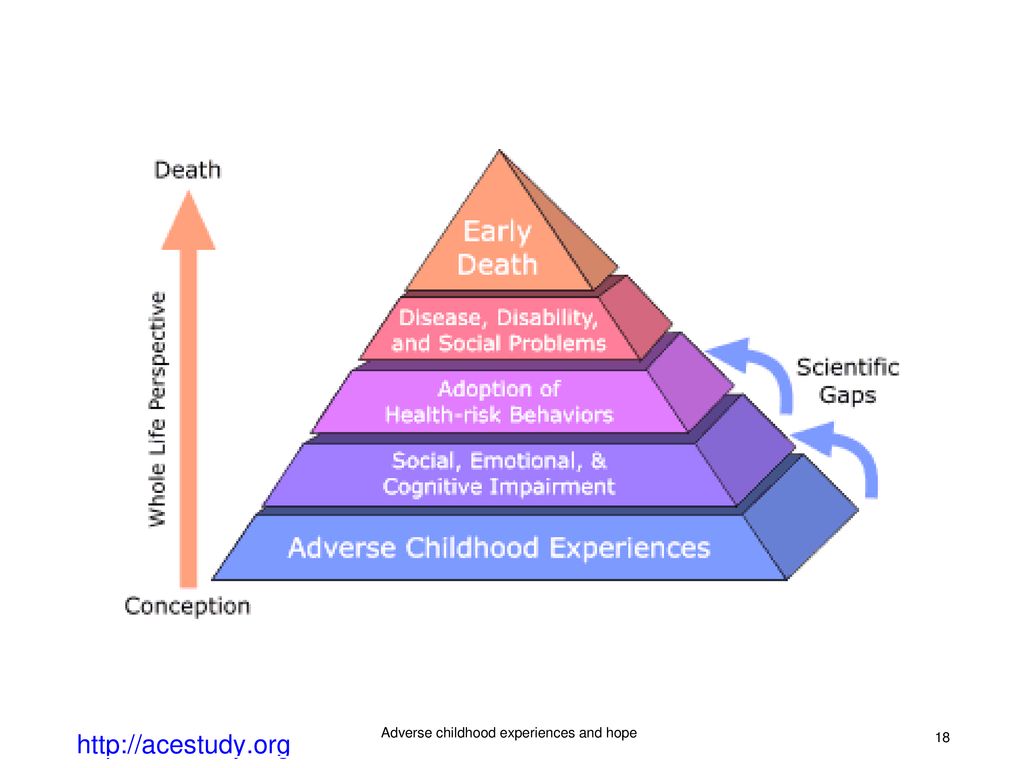

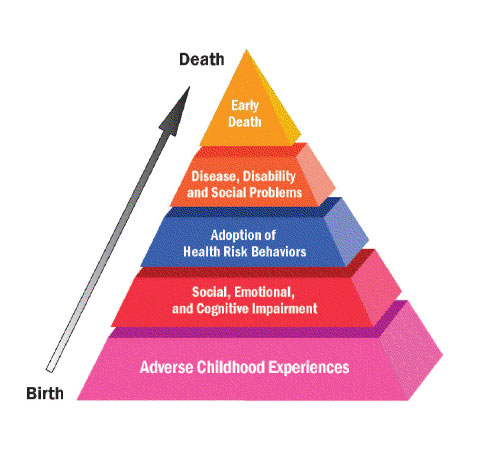

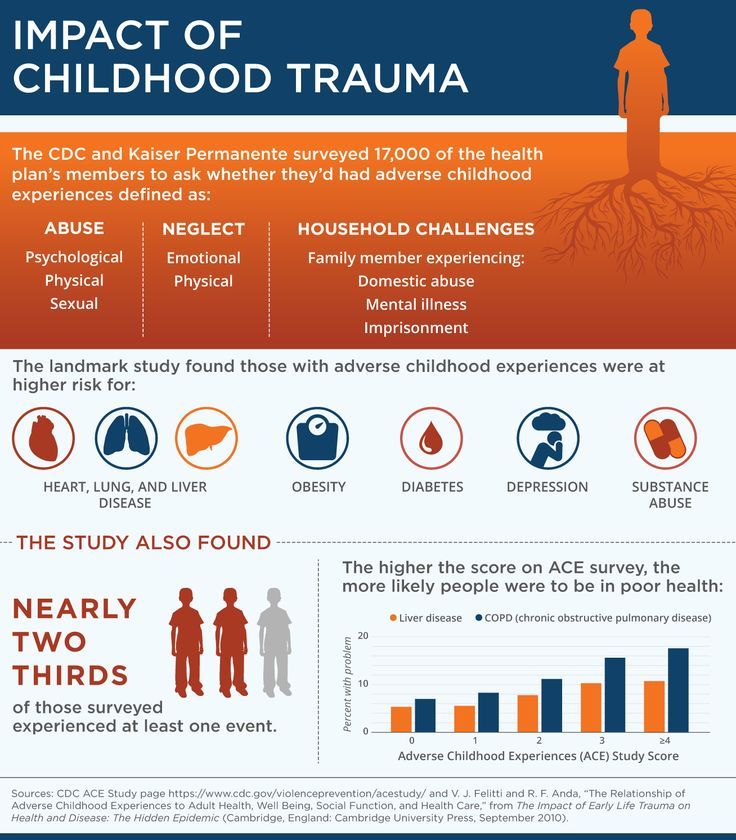

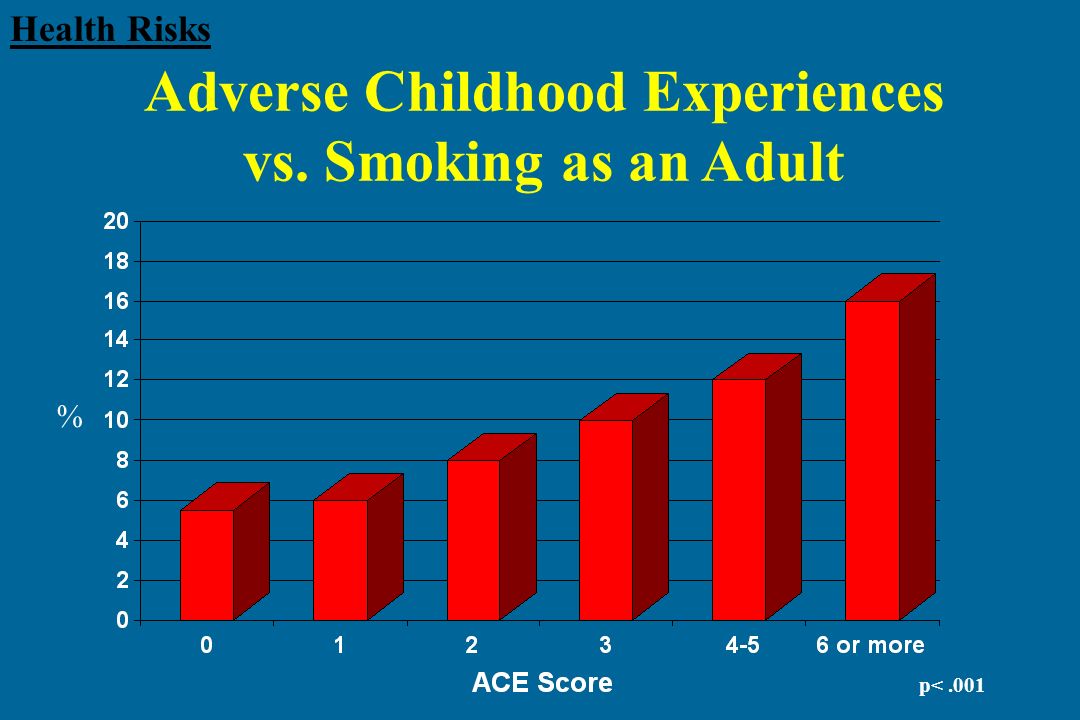

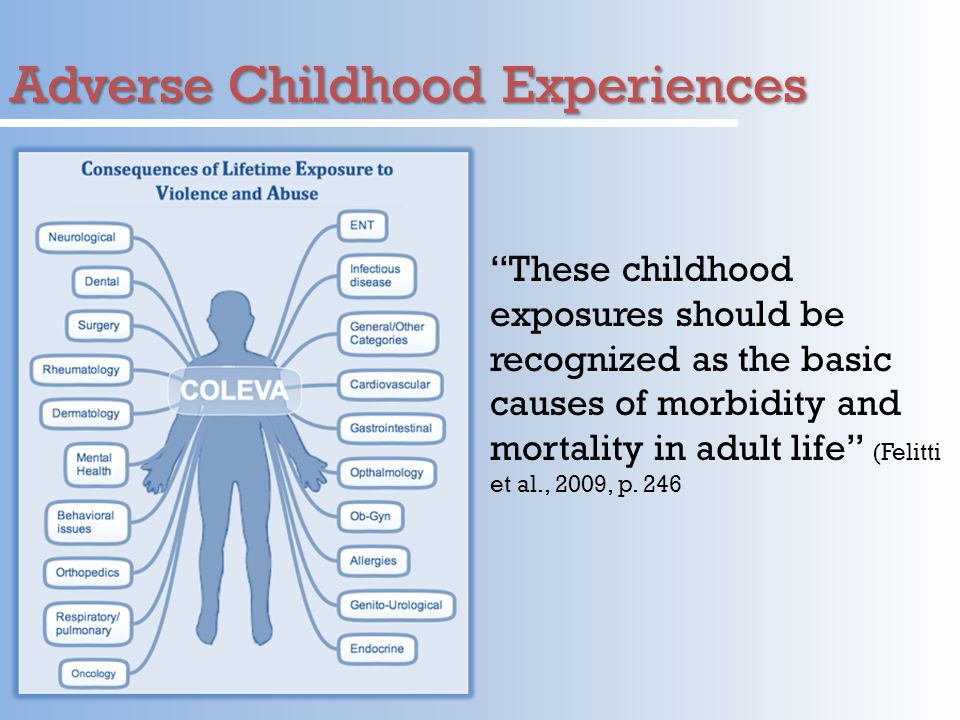

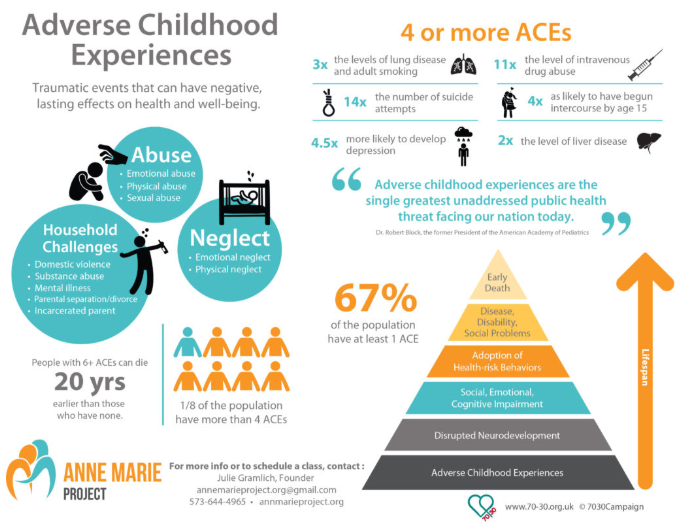

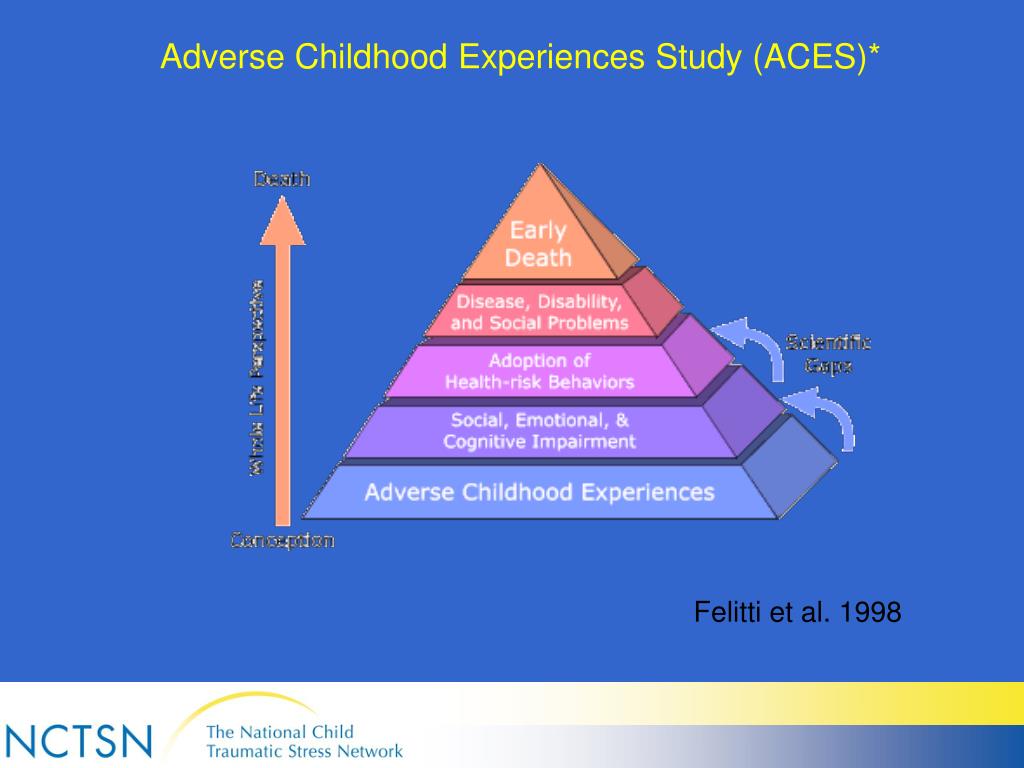

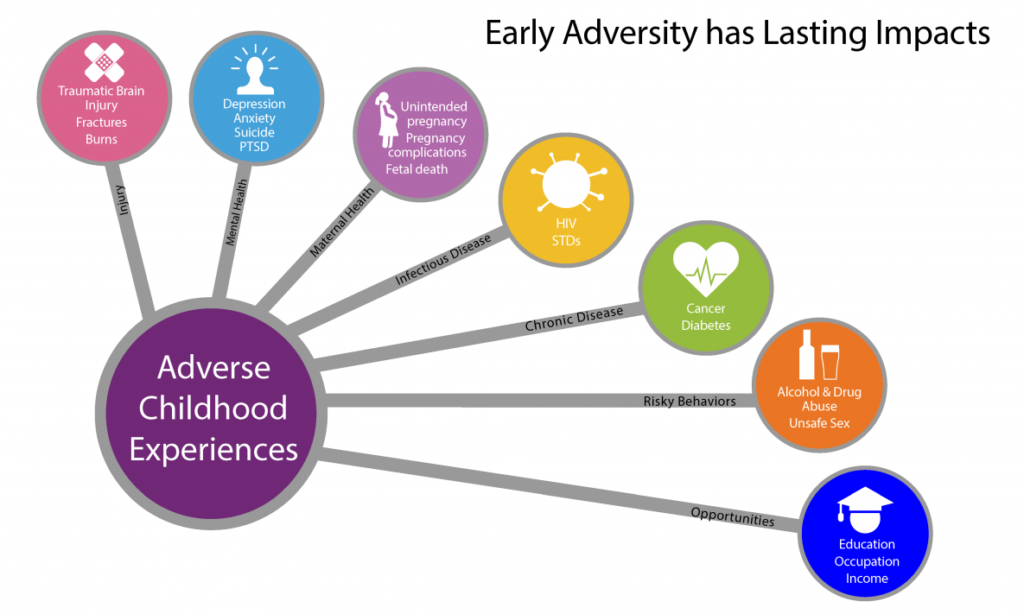

ACEs are linked to chronic health problems, mental illness, and substance use problems in adolescence and adulthood. ACEs can also negatively impact education, job opportunities, and earning potential. However, ACEs can be prevented.

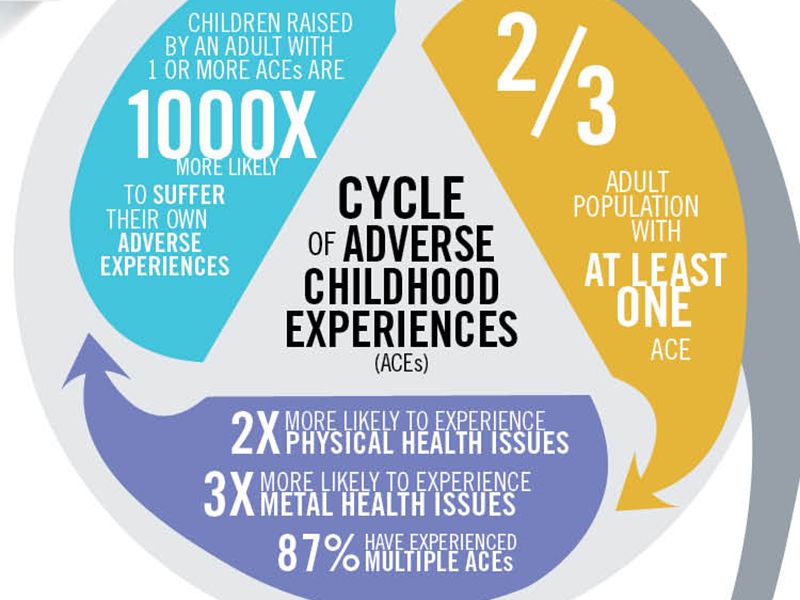

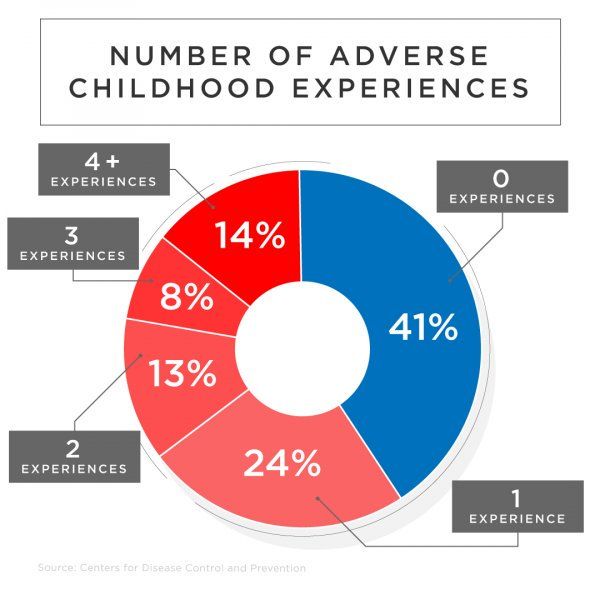

ACEs are common. About 61% of adults surveyed across 25 states reported they had experienced at least one type of ACE before age 18, and nearly 1 in 6 reported they had experienced four or more types of ACEs.

Preventing ACEs could potentially reduce many health conditions. For example, by preventing ACEs, up to 1.9 million heart disease cases and 21 million depression cases could have been potentially avoided.

Some children are at greater risk than others. Women and several racial/ethnic minority groups were at greater risk for experiencing four or more types of ACEs.

ACEs are costly. The economic and social costs to families, communities, and society totals hundreds of billions of dollars each year. A 10% reduction in ACEs in North America could equate to an annual savings of $56 billion.

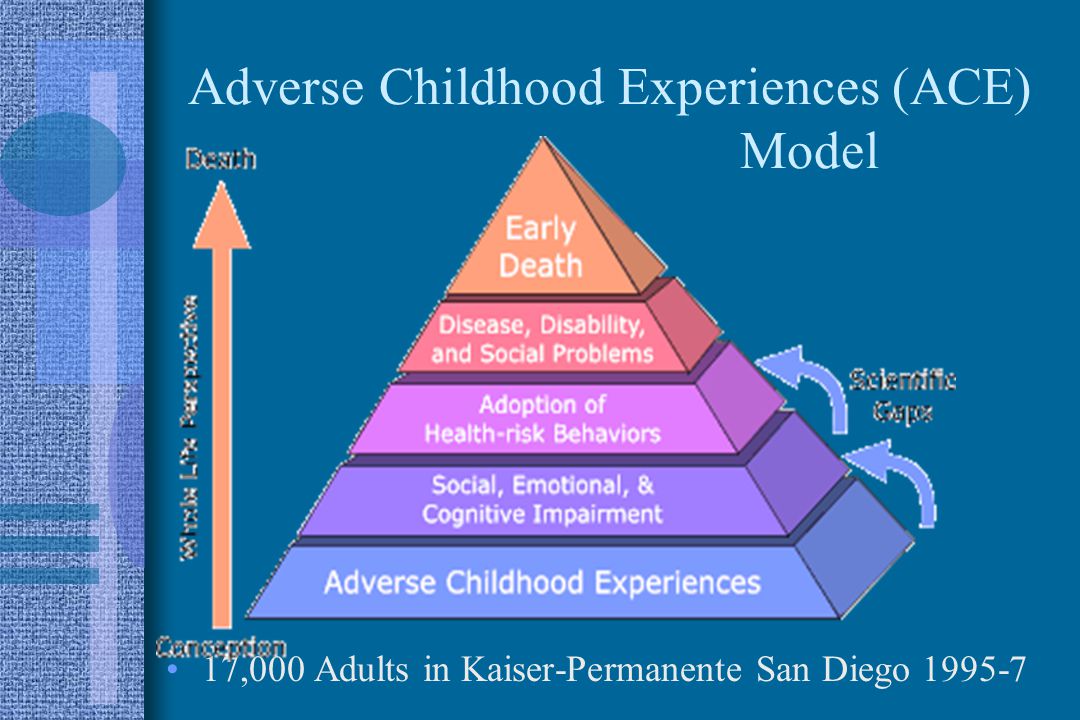

ACEs can have lasting, negative effects on health, well-being, as well as life opportunities such as education and job potential. These experiences can increase the risks of injury, sexually transmitted infections, maternal and child health problems (including teen pregnancy, pregnancy complications, and fetal death), involvement in sex trafficking, and a wide range of chronic diseases and leading causes of death such as cancer, diabetes, heart disease, and suicide.

These experiences can increase the risks of injury, sexually transmitted infections, maternal and child health problems (including teen pregnancy, pregnancy complications, and fetal death), involvement in sex trafficking, and a wide range of chronic diseases and leading causes of death such as cancer, diabetes, heart disease, and suicide.

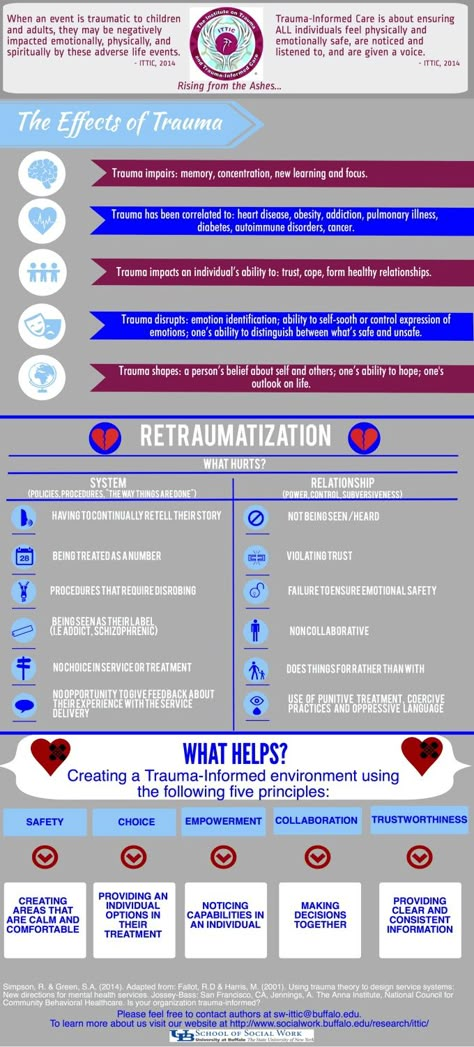

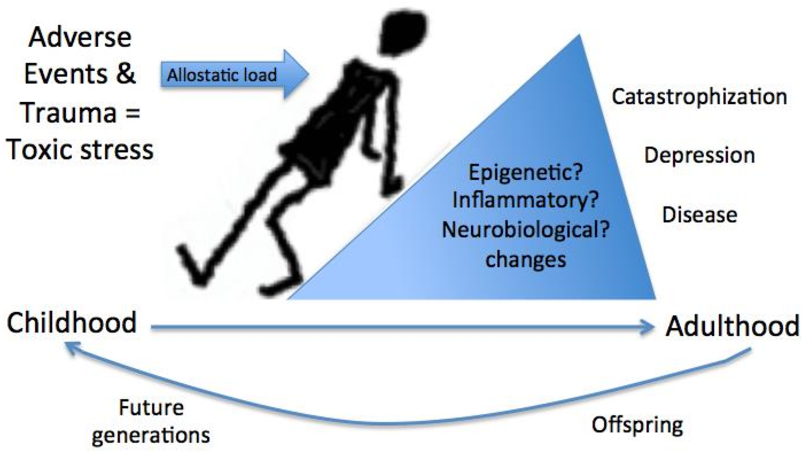

ACEs and associated social determinants of health, such as living in under-resourced or racially segregated neighborhoods, frequently moving, and experiencing food insecurity, can cause toxic stress (extended or prolonged stress). Toxic stress from ACEs can negatively affect children’s brain development, immune systems, and stress-response systems. These changes can affect children’s attention, decision-making, and learning.

Children growing up with toxic stress may have difficulty forming healthy and stable relationships. They may also have unstable work histories as adults and struggle with finances, jobs, and depression throughout life. These effects can also be passed on to their own children. Some children may face further exposure to toxic stress from historical and ongoing traumas due to systemic racism or the impacts of poverty resulting from limited educational and economic opportunities.

These effects can also be passed on to their own children. Some children may face further exposure to toxic stress from historical and ongoing traumas due to systemic racism or the impacts of poverty resulting from limited educational and economic opportunities.

ACEs are preventable. To prevent ACEs, we must understand and address the factors that put people at risk for or protect them from violence.

Creating and sustaining safe, stable, nurturing relationships and environments for all children and families can prevent ACEs and help all children reach their full potential. CDC has produced a resource, Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs): Leveraging the Best Available Evidencepdf icon, to help states and communities use the best available evidence to prevent ACEs. It features six strategies from the CDC Technical Packages to Prevent Violence.

Raising awareness of ACEs can help:

- Change how people think about the causes of ACEs and who could help prevent them.

- Shift the focus from individual responsibility to community solutions.

- Reduce stigma around seeking help with parenting challenges or substance misuse, depression, or suicidal thoughts.

- Promote safe, stable, nurturing relationships and environments where children live, learn, and play.

Let’s help all children reach their full potential and create neighborhoods, communities, and a world where every child thrives.

See Adverse Childhood Experiences Resources for publications, data sources, and prevention resources for adverse childhood experiences.About the CDC-Kaiser ACE Study |Violence Prevention|Injury Center|CDC

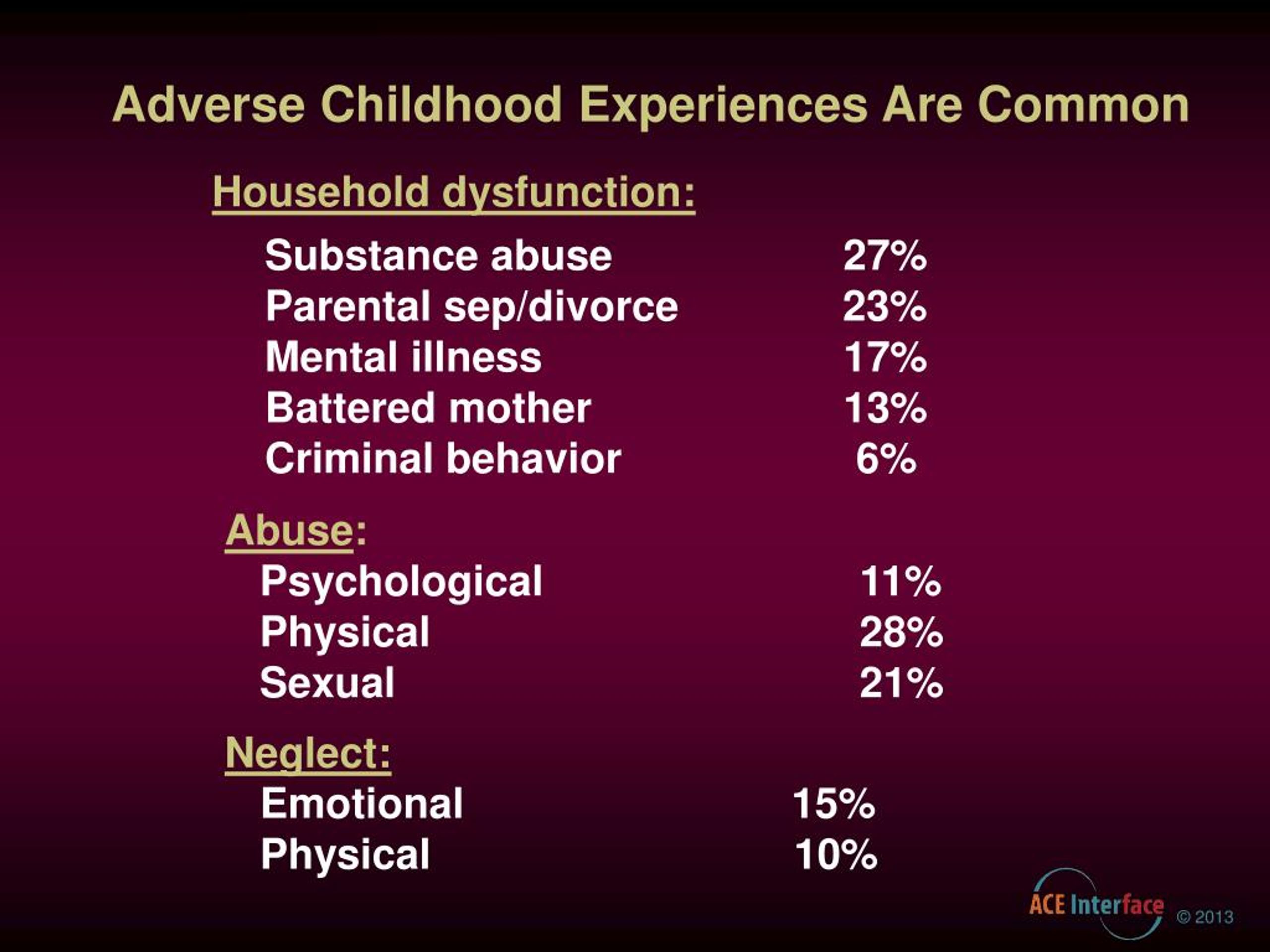

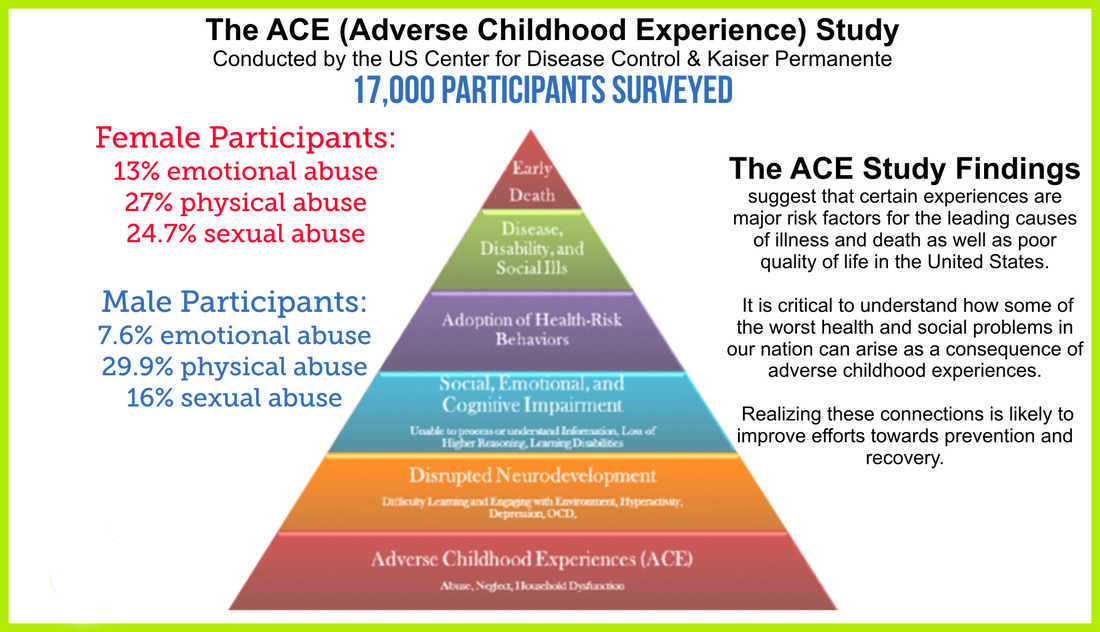

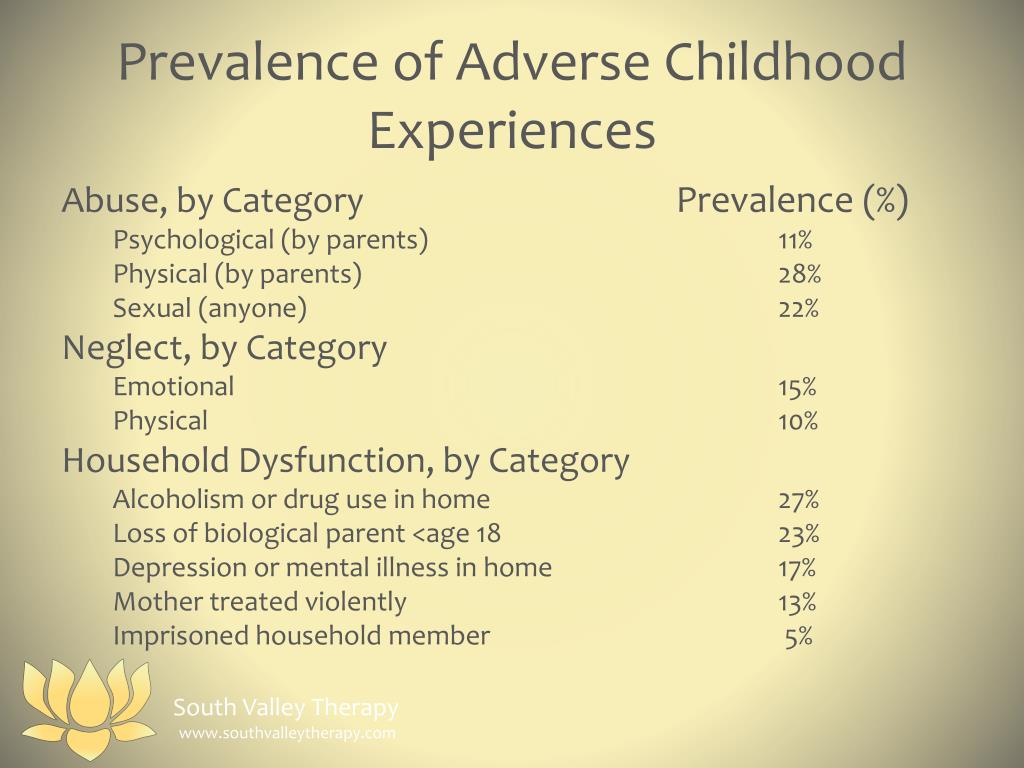

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are categorized into three groups: abuse, neglect, and household challenges. Each category is further divided into multiple subcategories. Participant demographic information is available by gender, race, age, and education. The prevalence of ACEs is organized by category.

ACEs Definitions

All ACE questions refer to the respondent’s first 18 years of life.

- Abuse

- Emotional abuse: A parent, stepparent, or adult living in your home swore at you, insulted you, put you down, or acted in a way that made you afraid that you might be physically hurt.

- Physical abuse: A parent, stepparent, or adult living in your home pushed, grabbed, slapped, threw something at you, or hit you so hard that you had marks or were injured.

- Sexual abuse: An adult, relative, family friend, or stranger who was at least 5 years older than you ever touched or fondled your body in a sexual way, made you touch his/her body in a sexual way, attempted to have any type of sexual intercourse with you.

- Household Challenges

- Mother treated violently: Your mother or stepmother was pushed, grabbed, slapped, had something thrown at her, kicked, bitten, hit with a fist, hit with something hard, repeatedly hit for over at least a few minutes, or ever threatened or hurt by a knife or gun by your father (or stepfather) or mother’s boyfriend.

- Substance abuse in the household: A household member was a problem drinker or alcoholic or a household member used street drugs.

- Mental illness in the household: A household member was depressed or mentally ill or a household member attempted suicide.

- Parental separation or divorce: Your parents were ever separated or divorced.

- Incarcerated household member: A household member went to prison.

- Mother treated violently: Your mother or stepmother was pushed, grabbed, slapped, had something thrown at her, kicked, bitten, hit with a fist, hit with something hard, repeatedly hit for over at least a few minutes, or ever threatened or hurt by a knife or gun by your father (or stepfather) or mother’s boyfriend.

- Neglect1

- Emotional neglect: Someone in your family never or rarely helped you feel important or special, you never or rarely felt loved, people in your family never or rarely looked out for each other and felt close to each other, or your family was never or rarely a source of strength and support.2

- Physical neglect: There was never or rarely someone to take care of you, protect you, or take you to the doctor if you needed it2, you didn’t have enough to eat, your parents were too drunk or too high to take care of you, or you had to wear dirty clothes.

1Collected during Wave 2 only.

2Items were reverse scored to reflect the framing of the question.

Participant Demographics

Demographic information is from the entire ACE Study sample (n=17,337).

Demographic Information for CDC-Kaiser ACE Study Participants, Waves 1 and 2. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Demographic Information | Percent (N = 17,337) | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 54.0% | |

| Male | 46.0% | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 74.8% | |

| Black | 4.5% | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 7. 2% 2% | |

| Other | 2.3% | |

| Hispanic | 11.2% | |

| Age (years) | ||

| 19-29 | 5.3% | |

| 30-39 | 9.8% | |

| 40-49 | 18.6% | |

| 50-59 | 19.9% | |

| 60 and over | 46.4% | |

| Education | ||

| Not High School Graduate | 7.2% | |

| High School Graduate | 17.6% | |

| Some College | 35.9% | |

| College Graduate or Higher | 39.3% | |

Note: Research papers that use Wave 1 and/or Wave 2 data may contain slightly different reports of participants’ demographic information.

ACEs Prevalence

The prevalence estimates reported below are from the entire ACE Study sample (n=17,337).

Prevalence of ACEs by Category for CDC-Kaiser ACE Study Participants by Sex, Waves 1 and 2. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ACE Category | Women | Men | Total |

| Percent (N = 9,367) | Percent (N = 7,970) | Percent (N = 17,337) | |

| ABUSE | |||

| Emotional Abuse | 13.1% | 7.6% | 10.6% |

| Physical Abuse | 27% | 29.9% | 28.3% |

| Sexual Abuse | 24.7% | 16% | 20.7% |

| HOUSEHOLD CHALLENGES | |||

| Mother Treated Violently | 13.7% | 11. 5% 5% | 12.7% |

| Substance Abuse | 29.5% | 23.8% | 26.9% |

| Mental Illness | 23.3% | 14.8% | 19.4% |

| Parental Separation or Divorce | 24.5% | 21.8% | 23.3% |

| Incarcerated Household Member | 5.2% | 4.1% | 4.7% |

| NEGLECT | |||

| Emotional Neglect3 | 16.7% | 12.4% | 14.8% |

| Physical Neglect3 | 9.2% | 10.7% | 9.9% |

Note: 3Collected during Wave 2 only (N=8,629). Research papers that use Wave 1 and/or Wave 2 data may contain slightly different prevalence estimates.

ACE Score Prevalence for CDC-Kaiser ACE Study Participants by Sex, Waves 1 and 2. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE Score) | Women Percent(N = 9,367) | Men Percent (N = 7,970) | Total Percent (N = 17,337) |

| 0 | 34.5% | 38.0% | 36.1% |

| 1 | 24.5% | 27.9% | 26.0% |

| 2 | 15.5% | 16.4% | 15.9% |

| 3 | 10.3% | 8.5% | 9.5% |

| 4 or more | 15.2% | 9.2% | 12.5% |

Note: Research papers that use Wave 1 and/or Wave 2 data may contain slightly different prevalence estimates.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Kaiser Permanente. The ACE Study Survey Data [Unpublished Data]. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016.

Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016.

Top of Page

The problem of negative childhood experiences. Causes, effects, solutions.

The study of adverse childhood experiences and ways of protecting children from negative childhood experiences (NEE) has made it possible to identify several key factors that play a protective role in this regard. In particular, this is the close environment of the child - parents, family members and neighbors.

Recently, the school was also included among the factors influencing the formation of NDO. Not only because the negative experiences of the child have a negative impact on academic performance: academic performance has long been one of the criteria for the somatic and psycho-emotional health of children. In recent decades, more and more evidence has emerged that poor school performance further spurs and intensifies the negative experiences of children and their families.

Breaking this vicious circle will help develop activities designed to support the academic performance and psycho-emotional state of children at the level of the school, educational institution. A child with NDO will particularly benefit from such a strategy.

The role of the family

The most powerful protective factor for the child's psyche is expected to be the presence of a family member with whom the child can communicate on absolutely any topic, in whom he has unlimited confidence. As a rule, this is one of the parents.

The traditional and most traumatic events are connected with the violation of the child's connection with the parents: divorce, death, imprisonment of mother or father, etc. As a result, children are left without the psychological support they need for full maturation, the formation of a harmonious personality.

But intra-family ties can also be destroyed for other reasons, without removing the child from the parents. For such cases, it is necessary to develop individual programs based on social services and psychological assistance. Then there is a chance to reduce the impact on the child of stress factors. In parallel, to eliminate the consequences of already received injuries.

Then there is a chance to reduce the impact on the child of stress factors. In parallel, to eliminate the consequences of already received injuries.

And anyway, even the widespread introduction of such programs does not fully meet the needs of children with NDO.

The role of the school

Most of the research on childhood trauma did not take into account one factor not related to the family - school life.

The World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recognize that school is not only a place for academic transmission, but also a place where vulnerable children can connect with supportive adults and peers outside their families.

Forming and maintaining stable relationships between children, children with teachers, strengthening attachment to school, have a noticeable effect on the development of depression, the formation of a tendency to use psychoactive substances and other types of risky behavior. By the way, on our website you can read about the relationship between attachment to school and the health of students.

Creating a favorable psycho-emotional atmosphere at school, when NDO children have almost daily contact with caring, benevolent adults and peers, has a distinct positive effect. Because these children have a home environment, as a rule, is unfavorable.

The following factors contribute to the effectiveness of “school rehabilitation”:

- decrease in the number of students in the class;

- professional development of teachers in terms of helping children with negative experiences;

- inclusion in the staff of the school of auxiliary specialists - a psychologist, school nurses, social workers, etc.

- cooperation with juvenile justice structures;

- accumulation of experience in mediation, conflict resolution in the families of such children.

School and medicine

In the future, it is necessary to realize that the school can become a point of access for students and their families to primary medical and psychological (psychiatric) care.

For example, school health centers in America offer underachieving students quality medical care in an educational, confidential, and welcoming environment.

This approach facilitates the provision of essential primary health and mental health care that is most relevant to the needs of adolescents and vulnerable populations. School and school-related mental health interventions are particularly effective in reaching at-risk students.

From words to deeds

There are many studies on negative childhood experiences. However, very few proposed clinical strategies have been tested in practice.

How soon the transition from the stage of documenting NDO problems to the implementation of concrete steps will take place depends on the financing of corrective programs.

In the long term, the transition from words to deeds would allow many students to avoid serious clinical problems and disorders in the future. Schools are, in this regard, an ideal vehicle through which healthy social relationships between pupils can be promoted.

This gives children with negative experiences the opportunity to build up their resilience and acquire positive social skills. Which, in turn, increases the likelihood of a healthy atmosphere already in their families, reduces the risk that their children will already experience the negative and traumatic influence of an unhealthy intra-family subculture.

Based on the American Academy of Pediatrics

Protective role of executive skills under adverse environmental conditions

Amanda J. Wenzel, BA, Megan R. Gunnar, PhD

University of Minnesota, USA

(English). Translation: August 2015

Introduction

Recently, the protective role of executive functions in the school success of children living in adverse living conditions has become a subject of consideration in the field of psychological stability. Executive function, also defined as cognitive control, reflects the ability to purposefully control thinking, behavior, and emotions. 1 These skills can manifest themselves in the ability to retain information in working memory, to maintain or shift attention, to inhibit involuntary reactions in order to perform an assigned or purposeful action, and in the ability to delay reward.

Executive function, also defined as cognitive control, reflects the ability to purposefully control thinking, behavior, and emotions. 1 These skills can manifest themselves in the ability to retain information in working memory, to maintain or shift attention, to inhibit involuntary reactions in order to perform an assigned or purposeful action, and in the ability to delay reward.

EF skills develop rapidly during the preschool years. 2 They are believed to provide the foundation for cognitive and behavioral school readiness. 3 During class, executive skills may manifest as the ability to focus, follow directions, wait in line, and memorize rules. These skills have been shown to be particularly important for stressed children during early childhood. Recent research suggests that executive skills are more predictive of resilience in school life and with peers than and beyond IQ. 4,5,6,7

Although executive skills are protective in children at risk, the development of these skills is susceptible to events such as trauma or chronic stress. 8 Children living in disadvantaged environments (e.g. homeless/frequently relocating, from poor families, registered with a social institution from an early age, subjected to abuse, etc.) often have executive dysfunctions. 6,7,9,10,11 Taken together, these studies suggest the need to reduce chronic stress and target management skills in children through educational and preventive interventions.

8 Children living in disadvantaged environments (e.g. homeless/frequently relocating, from poor families, registered with a social institution from an early age, subjected to abuse, etc.) often have executive dysfunctions. 6,7,9,10,11 Taken together, these studies suggest the need to reduce chronic stress and target management skills in children through educational and preventive interventions.

Item

Children who are at risk and have more developed executive skills demonstrate higher cognitive and behavioral readiness for school and activities in it. 3.12 Probably these skills enable children to navigate in a constantly changing environment, 9.13 which may be especially important for children whose development takes place in a chaotic environment.

However, previous research has shown that children exposed to increased exposure to adverse environmental conditions may be less prepared to succeed in school, due in part to impaired development of executive skills. 6,7,9,10,11 These impairments can undermine children's ability to succeed in school and to form positive relationships with peers and teachers. 12,14,15 This may have long-term consequences for school performance, given that the achievement gap tends to persist and even widen over the course of schooling. 16.17

6,7,9,10,11 These impairments can undermine children's ability to succeed in school and to form positive relationships with peers and teachers. 12,14,15 This may have long-term consequences for school performance, given that the achievement gap tends to persist and even widen over the course of schooling. 16.17

Given the evidence that executive skills can be easily corrected with learning interventions and that children who show weaker initial results achieve significant improvement, 18 recent attempts to improve school readiness of children at risk were aimed at developing managerial skills before entering kindergarten. 4.19 Moreover, research suggests that executive skills are amenable to learning programs during school years. 18

Issues

The study of the protective role of executive functions is accompanied by some difficulties. First, there are few measurement methods that fully reflect the executive abilities of children with delays in the development of these abilities. Because exposure to chronic stress in the early years has been linked to deficient executive skills in some children, 8 it is important to be able to assess a wide range of functioning in order to fully capture the variability of these skills.

Because exposure to chronic stress in the early years has been linked to deficient executive skills in some children, 8 it is important to be able to assess a wide range of functioning in order to fully capture the variability of these skills.

Current remedial programs to improve executive skills use a variety of methods, including training, the school curriculum, or physical activity. 18 While these programs suggest that executive skills are easily correctable, they also show mixed success in improving these skills. 20,21,22,23,24 Computer assisted learning programs show potential for improving executive skills; however, the improvements are limited to the area targeted by training (eg, working memory) and do not extend to other areas of executive functioning in general. 18

Other programs designed to encourage development of executive skills include activities to integrate these skills into children's daily lives, such as the "Tools of the Mind" preschool course. 25 During this course children are encouraged to use silent speech or visual reminders (eg a picture of an ear to remind them to listen or focus) to develop inhibition and impulse control skills. The initial results of the study suggested that children from groups where such training was provided had better development of managerial skills. 26 However, recent studies have failed to replicate these results, 27 which suggests that there may be difficulties in the course of study or difficulties with regard to the accuracy of the program.

25 During this course children are encouraged to use silent speech or visual reminders (eg a picture of an ear to remind them to listen or focus) to develop inhibition and impulse control skills. The initial results of the study suggested that children from groups where such training was provided had better development of managerial skills. 26 However, recent studies have failed to replicate these results, 27 which suggests that there may be difficulties in the course of study or difficulties with regard to the accuracy of the program.

Key questions

Developmental research designed to understand the protective role of executive functioning tends to answer the following questions:

- What is the mechanism by which executive functions prepare children for future school?

- What helps to stimulate the development of executive skills in young children who experience a delay in the development of these skills?

- What helps protect these skills from the effects of chronic stress?

Recent research results

Research consistently shows that children with better managerial skills are more likely to excel in school before entering kindergarten. 6.7 In terms of academic achievement, executive skills are able to support success in learning languages and mathematics. 12 Researchers have found that in children from low-income families, pre-kindergarten management skills are actually predictive of kindergarten numeracy and general literacy skills. 12 A successful transition to school can be a particularly important event for children who are severely affected by adverse environmental conditions and are at risk of poor school performance.

6.7 In terms of academic achievement, executive skills are able to support success in learning languages and mathematics. 12 Researchers have found that in children from low-income families, pre-kindergarten management skills are actually predictive of kindergarten numeracy and general literacy skills. 12 A successful transition to school can be a particularly important event for children who are severely affected by adverse environmental conditions and are at risk of poor school performance.

In addition to providing a cognitive basis for learning, executive skills can also support academic success by stimulating appropriate classroom behavior. 3 Many teachers in kindergartens point out that it is more important for children to be able to control themselves in class, follow instructions and not be a violator of discipline than to know the alphabet and be able to count to 20. 3 This indicates that teachers may view children with well-developed executive skills as more learnable than children who are more likely to be distracted and misbehave. 3

3

Moreover, executive skills can stimulate the development of positive relationships with teachers and peers. 28 Research shows that there is overlap between the development of executive functioning and mental model (MP), which is the ability to understand that other people have desires and knowledge that are different from ours. Such skills are associated with lower levels of aggression, better problem-solving skills, and positive social skills. 29.30 In addition, the ability to delay gratification may be related to children's ability to regulate frustration and stress. 31.32

Unexplored areas

There are currently limited studies on the effectiveness of remedial programs designed to support executive skills in children at particular risk. In designing remedial programs for these children, it is important to bear in mind that children who have been exposed to a variety of adverse factors may consistently present with impairments in executive functioning. 6,7,9,10,11 However, it is important to remember that the goals of remedial programs and the response of children with different backgrounds may differ. For children currently experiencing chronic stress (for example, for homeless/frequently relocating children), it remains an open question whether it is possible to purposefully develop executive skills without first correcting the level of stress experienced and developing psychological adaptation skills. Further research will be needed to determine the best way to adapt remedial programs to the needs of different children.

6,7,9,10,11 However, it is important to remember that the goals of remedial programs and the response of children with different backgrounds may differ. For children currently experiencing chronic stress (for example, for homeless/frequently relocating children), it remains an open question whether it is possible to purposefully develop executive skills without first correcting the level of stress experienced and developing psychological adaptation skills. Further research will be needed to determine the best way to adapt remedial programs to the needs of different children.

Findings

Research consistently suggests that trauma or chronic stress early in life can impair executive development. 6,7,9,10,11 It is likely that these skills provide the foundation for school readiness in the areas of cognition and behaviour. 3.12 Children with better executive skills may be more learnable. 3 In fact, children who were at risk, but who had better managerial skills when they entered kindergarten, showed better results in reading and writing ability and in numeracy compared to those children who initially had less developed skills. 12 Given that the achievement gap is a persistent phenomenon that can progress through school, it is very important that children at risk have the best possible start learning activities at school.

12 Given that the achievement gap is a persistent phenomenon that can progress through school, it is very important that children at risk have the best possible start learning activities at school.

For this reason, remedial programs that stimulate the development of managerial functions have received increased attention. Despite the fact that control functions are subject to corrective action, 18.33 few remedial programs have focused on maintaining skills in children experiencing toxic levels of stress. It is possible that attempts to create remedial programs that stimulate executive functions in these children should be directed towards addressing the current level of stress and at the same time they should help to reduce this level in order to achieve maximum benefit.

Advice for parents, social services and administrative policy

Research is currently highlighting the importance of managerial skills in relation to school success. These skills are especially important for children living in high-risk settings. Programs designed to stimulate executive functions are successful at all levels, including school curriculum, computer-assisted training, and even physical activities such as martial arts. 18,33,34 Similar to computer-assisted learning, parents can stimulate executive skills through games that require children to wait their turn, practice concentration skills, and use memory. Moreover, sensitive care can stimulate the development of executive skills by insulating children from some of the chaos that they have to deal with in the course of their development. 35

These skills are especially important for children living in high-risk settings. Programs designed to stimulate executive functions are successful at all levels, including school curriculum, computer-assisted training, and even physical activities such as martial arts. 18,33,34 Similar to computer-assisted learning, parents can stimulate executive skills through games that require children to wait their turn, practice concentration skills, and use memory. Moreover, sensitive care can stimulate the development of executive skills by insulating children from some of the chaos that they have to deal with in the course of their development. 35

Executive skills have also been successfully introduced through pre-school 26 school-based and Head Start groups. 4.34 Experimental evidence suggests that early childhood groups such as Head Start promote successful executive development by providing greater support for self-regulatory skills in children in the group (e. g., following clear rules and routines, refocusing or rewarding children's behavior). 34 Increasing attention to managerial skills in early childhood programs can close the gap in academic achievement that begins before school entry and persists throughout school.

g., following clear rules and routines, refocusing or rewarding children's behavior). 34 Increasing attention to managerial skills in early childhood programs can close the gap in academic achievement that begins before school entry and persists throughout school.

Literature

- Best JR, 1. Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A, Wager T. The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychol . 2000;41:49-100.

- Zelazo PD, Anderson JE, Richler J, Wallner-Allen K, Beaumont JL, Weintraub S. NIH toolbox cognitive function battery (CFB): Measuring executive function and attention. Monogr Soc Res Child. In press.

- Blair C. School readiness: Integrating cognition and emotion in a neurobiological conceptualization of children’s functioning at school entry. Am Psychol .

2002;57:111-127.

2002;57:111-127. - Bierman KL, Nix RL, Greenberg MT, Blair C, Domitrovich CE. Executive functions and school readiness intervention: Impact, moderation, and mediation in the Head Start REDI program. Developmental Psychopathol . 2008;20:821-843.

- Bierman KL, Domitrovich CE, Nix RL, et al. (2008). Promoting academic and social-emotional school readiness: The Head Start REDI program. Child Dev . 2008;79:1802-1817.

- Masten AS, Herbers JE, Desjardins CD, et al. Executive function skills and school success in young children experiencing homelessness. Educational Res . 2012;41:375-384.

- Obradovic J. Effortful control and adaptive functioning of homeless children: Variable-focused and person-focused analyses. J App Dev Psychol . 2010;31:109-117.

- Pechtel P, Pizzagalli DA. Effects of early life stress on cognitive and affective function: An integrated review of human literature. Psychopharmacology (Berl) .

2011;214:55-70.

2011;214:55-70. - DePrince AP, Weinzierl KM, Combs MD. Executive function performance and trauma exposure in a community sample of children. Child Abuse Neglect . 2009;33:353-361.

- Loman MM, Johnson AE, Westerlund A, et al. The effect of early deprivation on executive attention in middle childhood. J Child Psychol Psyc . 2012;54:37-45.

- Pears KC, Fisher PA, Bruce J, Kim HK, Yoerger K. Early elementary school adjustment of maltreated children in foster care: The role of inhibitory control and caregiver involvement. Child Dev . 2010;81:1550-1564.

- Welsh JA, Nix RL, Blair C, Bierman KL, Nelson, KE. The development of cognitive skills and gains in academic school readiness for children from low-income families. J Educ Psychol . 2010;102:43-53.

- Willcutt, EG, Brodsky K, Chhabildas N, et al. The neuropsychology of ADHD: Validity of the executive function hypothesis.

In: Gozal D, Molfese DL, eds. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: From genes to patients . 3rd ed. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 205:185-213.

In: Gozal D, Molfese DL, eds. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: From genes to patients . 3rd ed. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 205:185-213. - Liew, J. Effortful control, executive functions, and education: Bringing self-regulatory and social-emotional competences to the table. Child Dev Perspective. 2011;6:105-111.

- McClelland MM, Cameron CE, Connor CM, Farris CL, Jewkes AM, Morrison FJ. Links between behavioral regulation and preschoolers’ literacy, vocabulary, and math skills. Dev Psychol . 2007;43:947–959.

- Cutuli JJ, Desjardins CD, Herbers JE, et al. Academic achievement trajectories of homeless and highly mobile students: Resilience in the context of chronic and acute risk. Child Dev . In press.

- Herbers JE, Cutuli JJ, Supkoff LM, et al. Early reading skills and academic achievement trajectories of students facing poverty, homelessness, and high residential mobility. Educational Res .

2012;41:366-365.

2012;41:366-365. - Diamond A, Lee K. Intervention shown to aid executive function development in children 4-12 years old. Science . 2011;333:959-964.

- Blair C, Razza RP. Relating effortful control, executive function, and false belief understanding to emerging math and literacy ability in kindergarten. Child Dev . 2007;78:647-663.

- Holmes J, Gathercole SE, Dunning DL. Adaptive training leads to sustained enhancement of poor working memory in children. Developmental Sci. 2009;12:F9-F15.

- Holmes J, Gathercole SE, Place M, Dunning DL, Hilton KA, Elliott JG. Appl Cognitive Psych . 2010;24:827-836.

- Klingberg T, Fernell E, Olesen P, et al. Computerized training of working memory in children with ADHD- a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry . 2005;44:177-186.

- Bergman-Nutley S, Söderqvist S, Bryde S, Thorell LB, Humphreys K, Klingberg T. Gains in fluid intelligence after training non-verbal reasoning in 4-year-old children: a controlled randomized study.

DevSci. 2011;14:591-601.

DevSci. 2011;14:591-601. - Thorell LB, Lindqvist S, Bergman-Nutley S, Bohlin G, Klingberg T. Training and transfer effects of executive functions in preschool children. DevSci. 2009;12:106-113.

- Bodrova E, Leon DJ. Tools of the Mind: The Vygotskian approach to early childhood education . ed. 2. New York: Merrill/Prentice Hall; 2007.

- Diamond A, Barnett WS, Thomas J, Munro S. Preschool program improves cognitive control. Science . 2007;318:1387-1388.

- Wilson SJ, Farran DC. Experimental evaluation of the Tools of the Mind preschool curriculum. Paper presented at the Society for Research on Educational Effectiveness; March 2012; Washington DC.

- Riggs NR, Jahromi LB, Razza RP, Dillworth-Bart JE, Mueller U. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2006;27:300-309.

- Capage L, Watson AC. Individual differences in theory of mind, aggressive behavior, and social skills in young children. Early Educ Dev .

2001;12:613–628.

2001;12:613–628. - Jenkins JM, Astington JW. Theory of mind and social behavior: Causal model tested in a longitudinal study. Merrill Palmer Quart . 2000;46:203-220.

- Mischel W, Shoda Y, Rodriguez ML. Delay of gratification in children. Science . 1989;244:933-938.

- Sethi A, Mischel W, Aber JL, Shoda Y, Rodriguez, ML. The role of strategic attention deployment in development of self-regulation: Predicting preschoolers' delay of gratification from mother – toddler interactions. Dev Psychol. 2000;36:767–777.

- Zelazo PD, Carlson SM. Hot and cool executive function in childhood and adolescence: Development and plasticity. Child Dev Perspective . 2012;6:354-360.

- Raver CC, Jones SM, Li-Grining C, Zhai F, Bub K, Pressler E. CSRPs impact on low-income preschoolers’ preacademic skills: Self-regulation as a mediating mechanism. Child Dev . 2011;82:362-378.

- Lewis-Morrarty E, Dozier M, Bernard K, Terraciano SM, Moore SV.