Adjustment disorder dsm 5 diagnosis code

Adjustment Disorders, with or without Anxiety and Depression: DSM5 Code 309

Adjustment Disorders

Adjustment Disorders

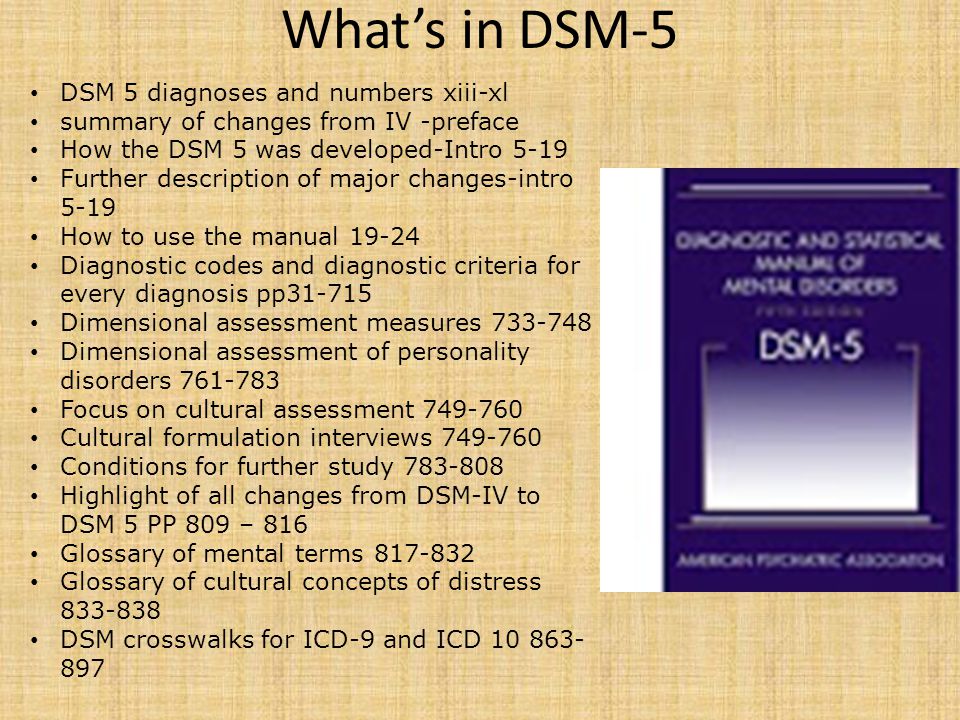

The newest guide to diagnosing mental disorders is the DSM-5, classifies Adjustment Disorders as Stressor-related disorders which are caused by a specific stressor. [2]

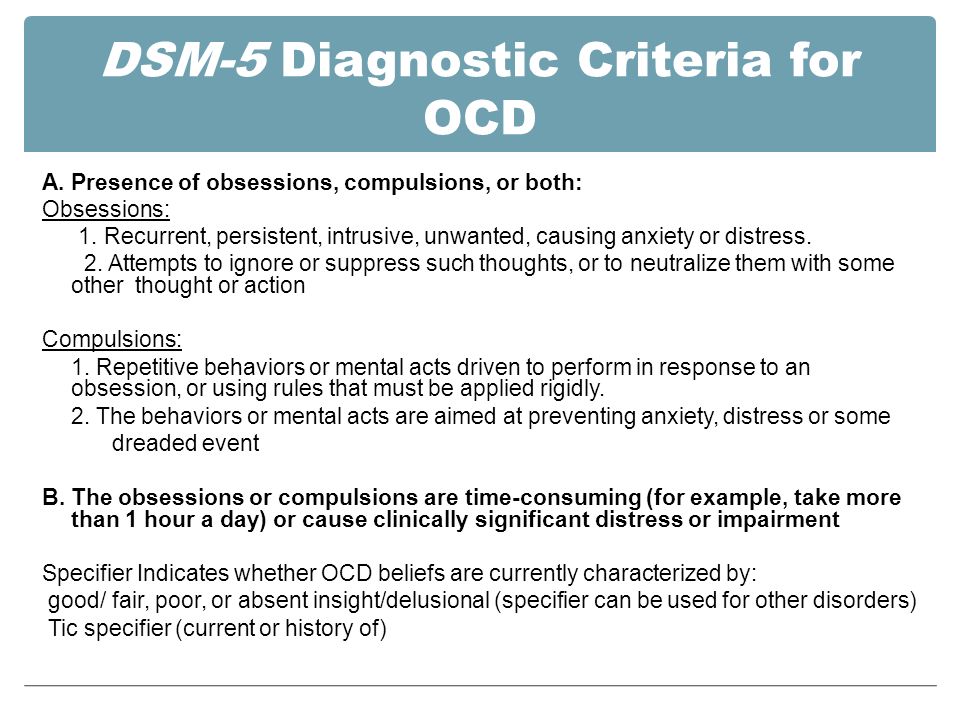

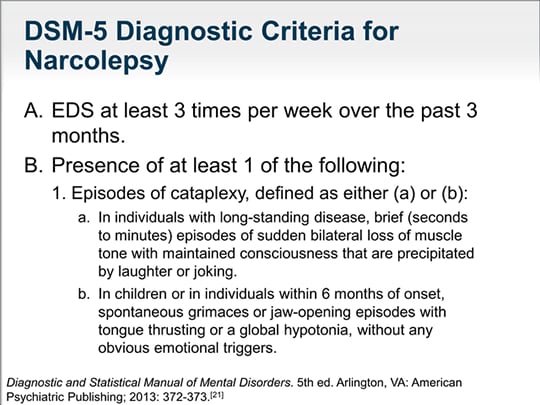

Adjustment Disorders DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria

Code 309

- "A. The development of emotional or behavioral symptoms in response to an identifiable stressor(s) occurring within 3 months of the onset of the stressor(s).

- B. These symptoms or behaviors are clinically significant, as evidenced by one or both of the following:

- Marked distress that is out of proportion to the severity or intensity of the stressor, taking into account the external context and the cultural factors that might influence symptom severity and presentation.

- Significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

- C. The stress-related disturbance does not meet the criteria for another mental disorder and is not merely an exacerbation of a preexisting mental disorder.

- D. The symptoms do not represent normal bereavement.

- E. Once the stressor or its consequences have terminated, the symptoms do not persist for more than an additional 6 months." [2]:151-152

Specify whether:

- Acute, Persistent (Chronic)

Specify whether:

- 309.0 F43.21 With depressed mood: Low mood, tearfulness, or feelings of hopelessness are predominant.

- 309.24 F43.22 With anxiety: Nervousness, worry, jitteriness, or separation anxiety is predominant.

- 309.28 F43.23 With mixed anxiety and depressed mood: A combination of depression and anxiety is predominant.

- 309.3 F43.24 With disturbance of conduct: Disturbance of conductis predominant.

- 309.4 F43.25 With mixed disturbance or emotions and conduct: Both emotional symptoms (e.

g., depression and anxiety) and a disturbance of conduct are predominant.

g., depression and anxiety) and a disturbance of conduct are predominant. - 309.9 F43.20 Unspecified For maladapative reactions that are not classifiable as one of the specified subtypes of adjustment disorder. [2]:151-152

ICD Diagnostic Criteria

The most recent approved version of the International Classification of Diseases, the diagnostic guide published by the World Health Organization is the ICD-10, published in 1992.[2] The draft ICD-11 criteria for Adjustment Disorders gives this description:

ICD 11 draft - Adjustment Disorder

Code 7B23

"Adjustment disorder is a maladaptive reaction to identifiable psychosocial stressor(s) or life change(s) characterized by preoccupation with the stressor and failure to adapt. The failure to adapt may be manifested by a range of symptoms that interfere with everyday functioning, such as difficulties concentrating or sleep disturbance. Symptoms of anxiety, depression, and impulse control or conduct problems are commonly present and may be the presenting feature. The symptoms emerge within a month of the onset of the stressor(s) and tend to resolve in 6 months unless the stressor persists for a longer duration. In order to be diagnosed, Adjustment disorder must be associated with significant distress or significant impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational or other important areas of functioning." [3] Last updated December 2014.

The symptoms emerge within a month of the onset of the stressor(s) and tend to resolve in 6 months unless the stressor persists for a longer duration. In order to be diagnosed, Adjustment disorder must be associated with significant distress or significant impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational or other important areas of functioning." [3] Last updated December 2014.

Alternative names include culture shock, grief reaction, and hospitalism in children. Excludes separation anxiety disorder of childhood. [3]

ICD 10 Diagnostic Criteria

Code F43.2

"States of subjective distress and emotional disturbance, usually interfering with social functioning and performance, arising in the period of adaptation to a significant life change or a stressful life event. The stressor may have affected the integrity of an individual's social network (bereavement, separation experiences) or the wider system of social supports and values (migration, refugee status), or represented a major developmental transition or crisis (going to school, becoming a parent, failure to attain a cherished personal goal, retirement). Individual predisposition or vulnerability plays an important role in the risk of occurrence and the shaping of the manifestations of adjustment disorders, but it is nevertheless assumed that the condition would not have arisen without the stressor. The manifestations vary and include depressed mood, anxiety or worry (or mixture of these), a feeling of inability to cope, plan ahead, or continue in the present situation, as well as some degree of disability in 9the performance of daily routine. Conduct disorders may be an associated feature, particularly in adolescents. The predominant feature may be a brief or prolonged depressive reaction, or a disturbance of other emotions and conduct." [1]

Individual predisposition or vulnerability plays an important role in the risk of occurrence and the shaping of the manifestations of adjustment disorders, but it is nevertheless assumed that the condition would not have arisen without the stressor. The manifestations vary and include depressed mood, anxiety or worry (or mixture of these), a feeling of inability to cope, plan ahead, or continue in the present situation, as well as some degree of disability in 9the performance of daily routine. Conduct disorders may be an associated feature, particularly in adolescents. The predominant feature may be a brief or prolonged depressive reaction, or a disturbance of other emotions and conduct." [1]

Alternative names include culture shock, grief reaction, and hospitalism in children. Excludes separation anxiety disorder of childhood. [1]

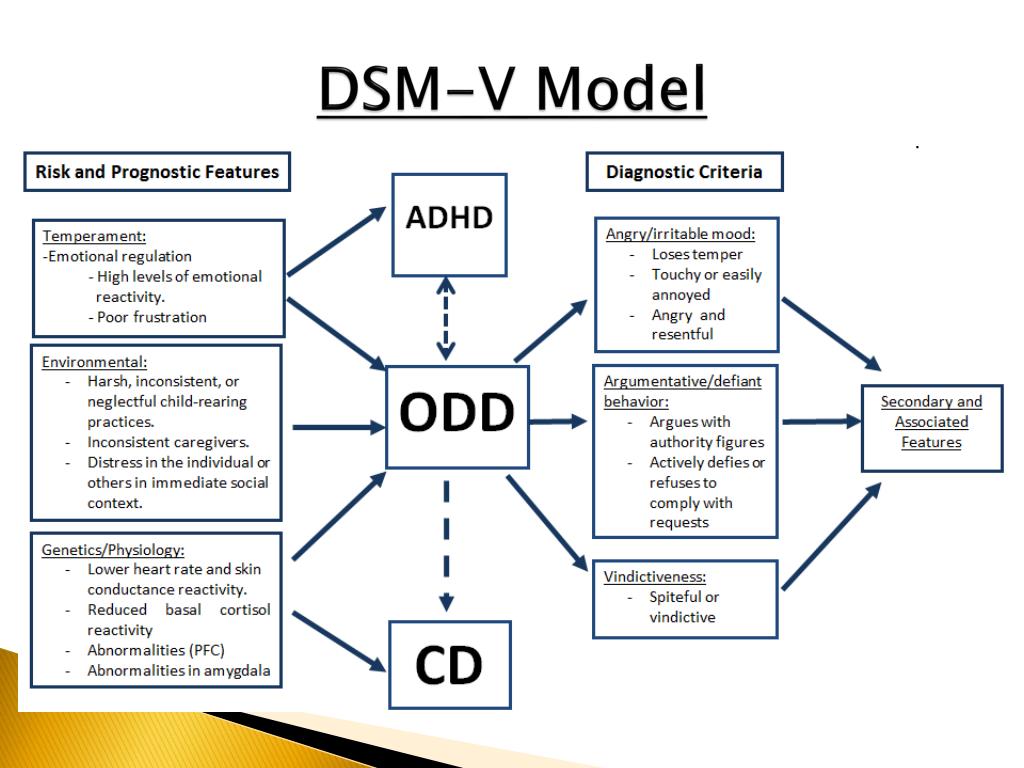

Comorbidity

Co-occuring disorders are restricted. For example, an Adjustment Disorder cannot be diagnosed if a more specific psychiatric disorder is appropriate, for example major depressive disorder or panic disorder, even if the stressor is the cause of the disorder. [4]:186 Disturbance of conduct may leads to a person acting out, for example a teenager stealing or an adult conducting an extra-marital affair. [4]:188

[4]:186 Disturbance of conduct may leads to a person acting out, for example a teenager stealing or an adult conducting an extra-marital affair. [4]:188

References

1. World Health Organization. (2010) ICD-10 Version: 2010. Retrieved December 7, 2014, from http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2010/en#

2. American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. (5th ed.). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association. ISBN 0890425558.

3. World Health Organization. (December 7, 2014). ICD-11 Beta Draft (Joint Linearization for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics).

4. Black, Donald W. (2014) (coauthors: Grant, Jon E.). DSM-5 Guidebook: The Essential Companion to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. American Psychiatric Pub. ISBN 9781585624652.

Cite this page

Adjustment Disorders. Traumadissociation. com. Retrieved from .

com. Retrieved from .

This information can be copied or modified for any purpose, including commercially, provided a link back is included. License: CC BY-SA 4.0

Adjustment Disorder: Current Diagnostic Status

Indian J Psychol Med. 2013 Jan-Mar; 35(1): 4–9.

doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.112193

Author information Copyright and License information Disclaimer

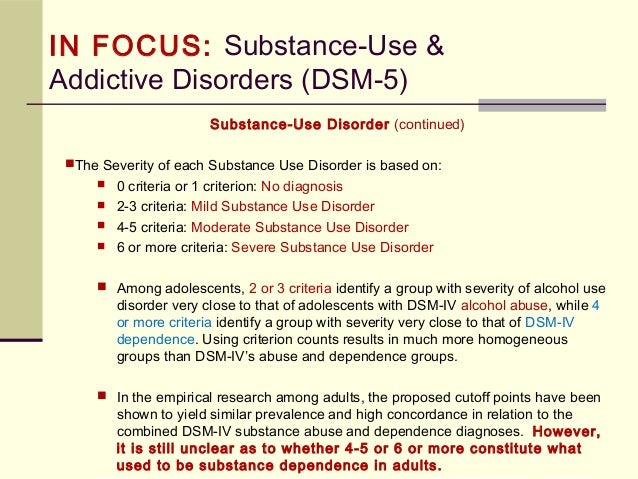

Adjustment disorder is a common diagnosis in psychiatric settings and carries a significant rate of morbidity. However, diagnostic criteria are vague and not much helpful in clinical practice. Also there has been relatively little research done on this disorder. In this article, we review the information that is available on the epidemiology, clinical features, validity, and current diagnostic status of adjustment disorder. In this article, the controversy surrounding the diagnosis is also highlighted. It also discusses the differential and comorbid diagnosis. The various recommendations for DSM-V and ICD-11 conclude the article.

Keywords: Adjustment disorder, current nosology, epidemiology, validity

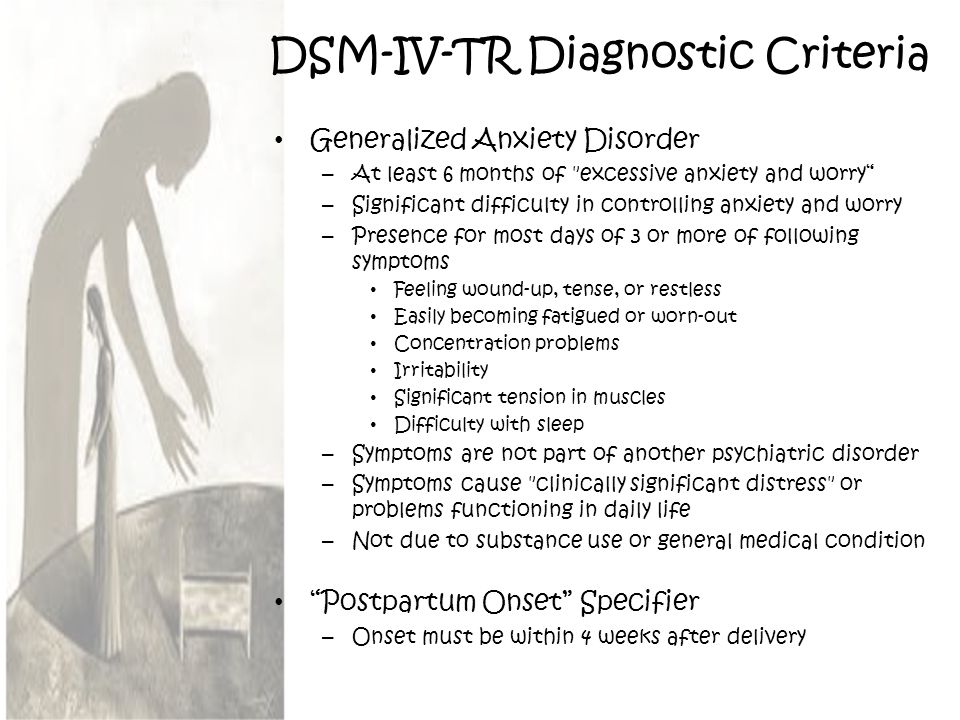

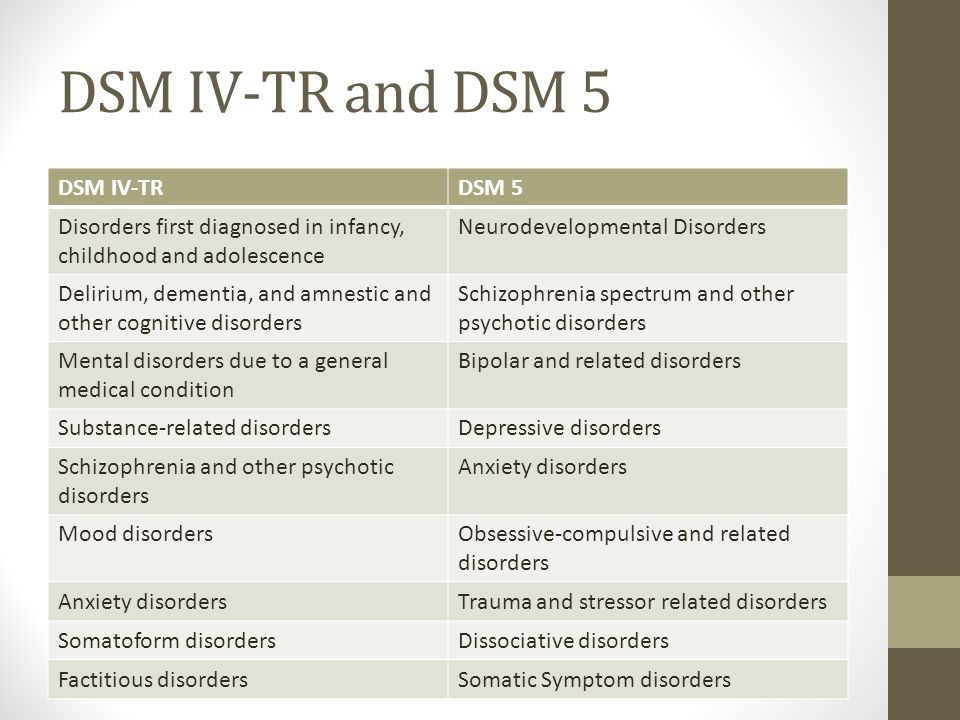

The adjustment disorder is a diagnostic category characterized by an emotional response to a stressful event. It is a state of subjective distress and emotional disturbance, which arises during the course of adapting to stresses of significant life changes, stressful life events, serious physical illness, or possibility of serious illness. Stress is ubiquitous and a person learns to deal with stress over time. However, when coping mechanisms fail to ameliorate stress effectively, adjustment disorder is precipitated. At a variance from the largely atheoretical model of International Classification of Diseases and Health Related Conditions (ICD) 10 and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) IV TR, adjustment disorder is one of the few disorders that take into account the potential cause of the disorder. Adjustment disorder is a psychiatric diagnosis that falls between normal behavior and the major psychiatric disorders and thus produces taxonomical and diagnostic dilemmas. [1]

[1]

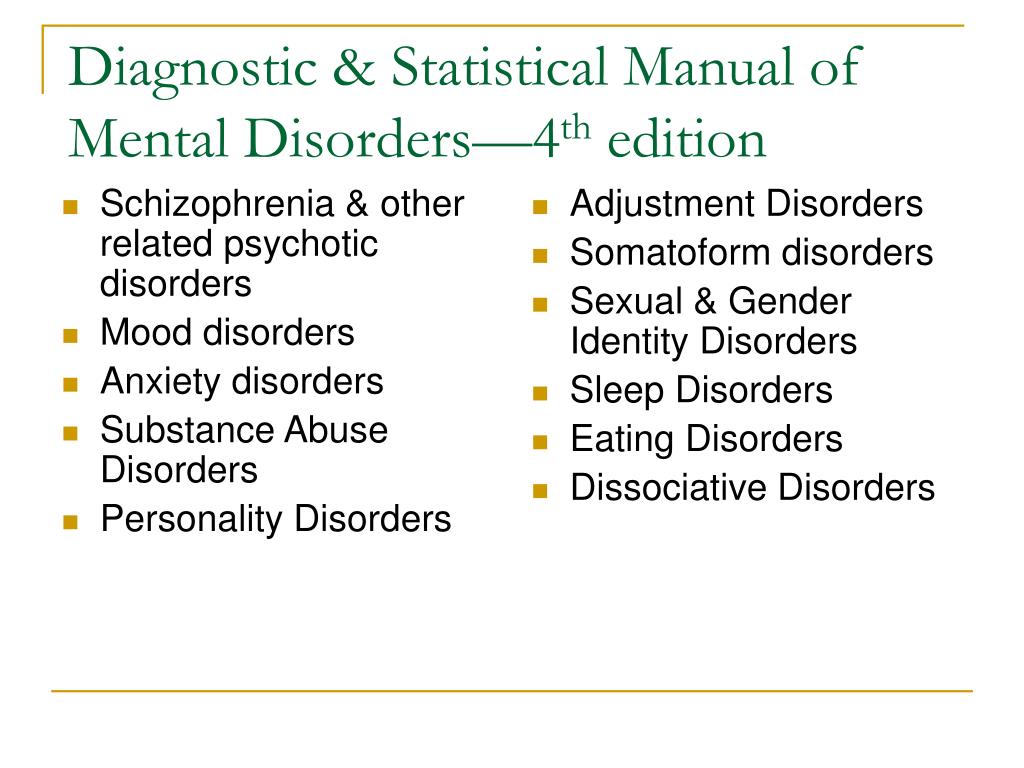

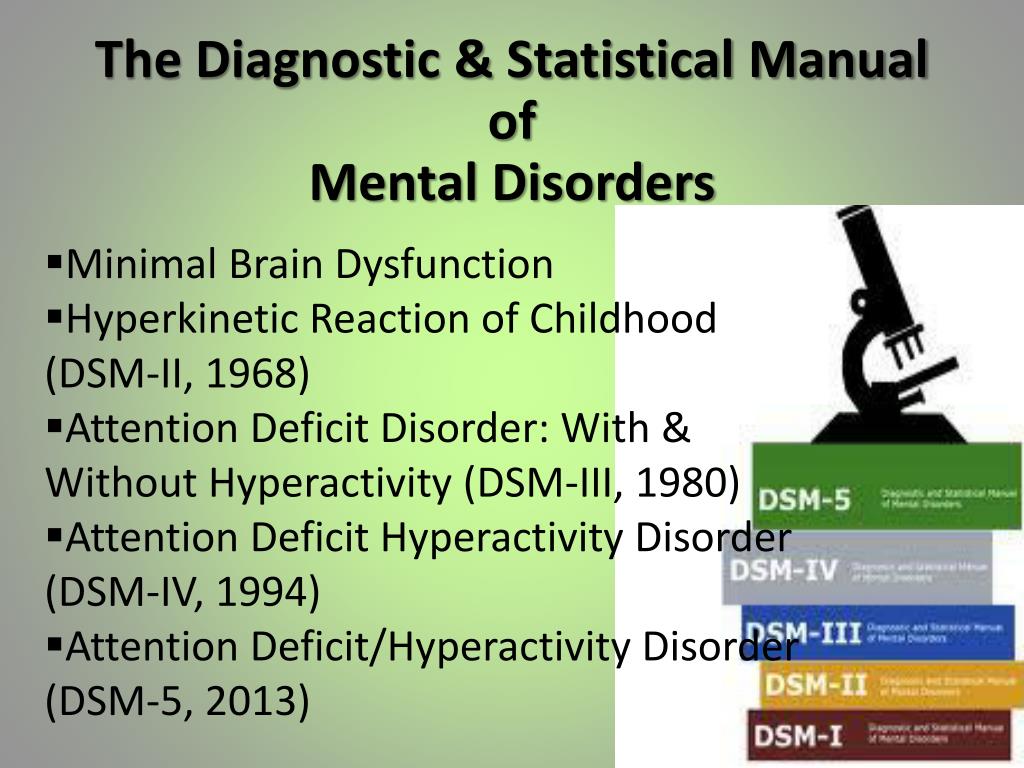

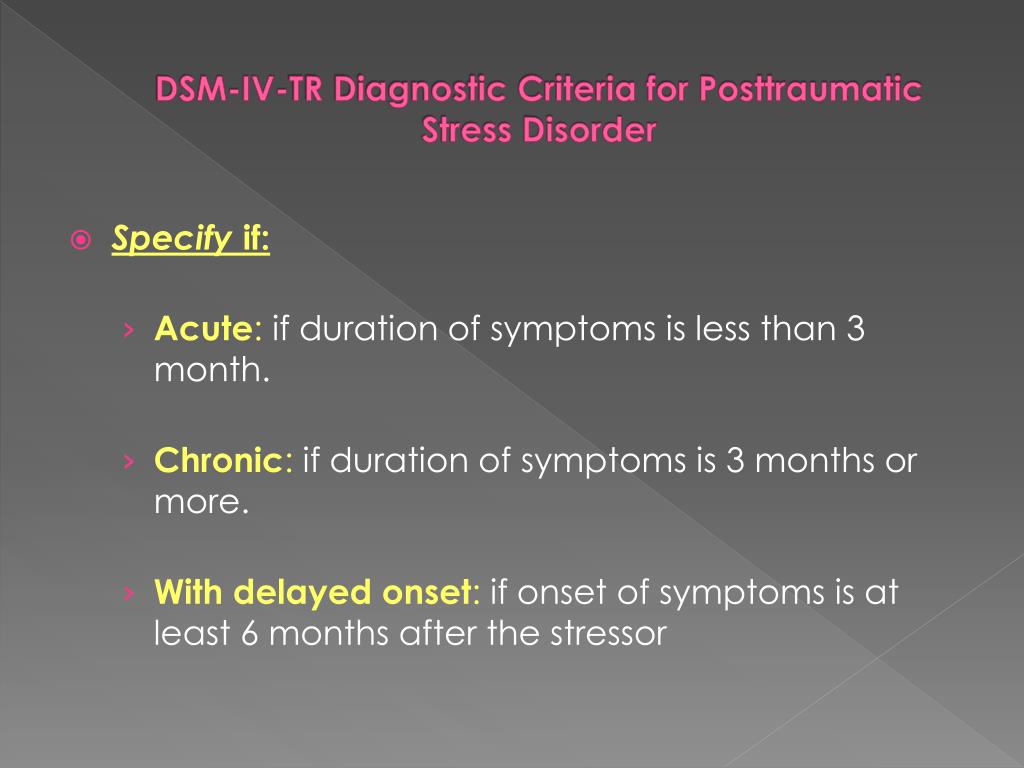

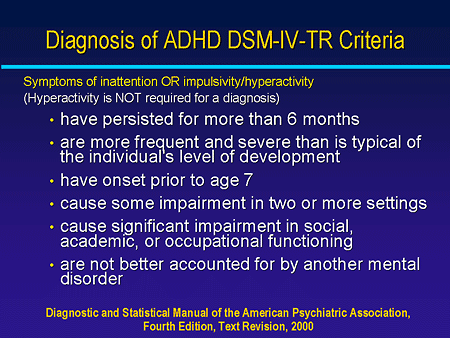

The first clinical description of an adjustment disorder came in the 11th century writings of physician-philosopher Avicenna. Severe war time stress during World War II and the evolution of crisis-intervention theory and practice led to further work upon stress-related conditions including adjustment disorder. The DSM-I in 1952 described this as “Transient Situational Personality Disorder” which is the vulnerability in personality during stressful situations. The subtypes of this entity were gross stress reaction, adult situational reaction, adjustment reaction of infancy, adjustment reaction of childhood, adjustment reaction of adolescence, and adjustment reaction of late life. In DSM-II (1968) it was changed to Transient Situational Disorder and the subtypes were adjustment reactions of infancy, adjustment reaction of childhood, adjustment reaction of adolescence, adjustment reaction of late life, and adjustment reaction of adult life. The DSM-III (1980) introduced the term adjustment disorder in which developmental periods of diagnostic categorization were eliminated and subtypes were based upon affective experience. These were adjustment disorder with depressed mood, anxious mood, mixed emotional features, disturbance of conduct, mixed disturbance of emotions and conduct, work inhibition, withdrawal and atypical features. DSM-III-R (1987) added an additional subcategory of involvement of physical complaints, and specified that symptoms could not last longer than 6 months. In DSM IV (1994), subtypes of mixed emotional features, work inhibition, withdrawal, and physical complaints were eliminated. The stressor was allowed to persist for indefinite period of time and a descriptor of chronicity (of more than 6 months) was specified.[2]

These were adjustment disorder with depressed mood, anxious mood, mixed emotional features, disturbance of conduct, mixed disturbance of emotions and conduct, work inhibition, withdrawal and atypical features. DSM-III-R (1987) added an additional subcategory of involvement of physical complaints, and specified that symptoms could not last longer than 6 months. In DSM IV (1994), subtypes of mixed emotional features, work inhibition, withdrawal, and physical complaints were eliminated. The stressor was allowed to persist for indefinite period of time and a descriptor of chronicity (of more than 6 months) was specified.[2]

In the ICD diagnostic system, adjustment disorder was incorporated in 1978 in ICD 9.

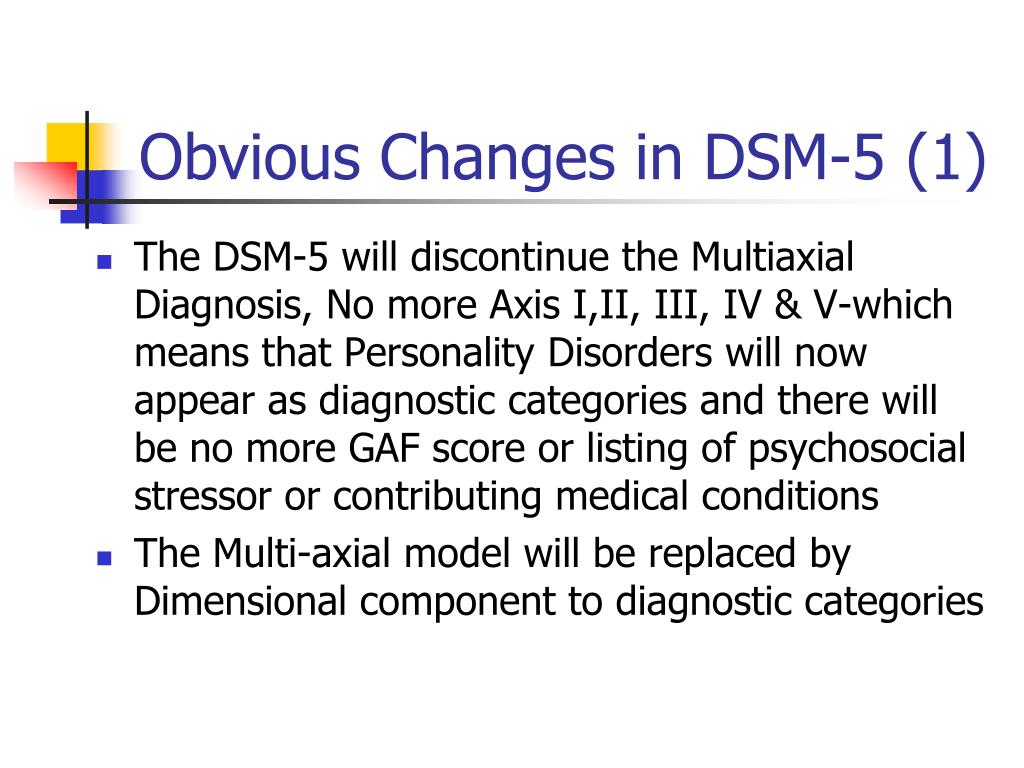

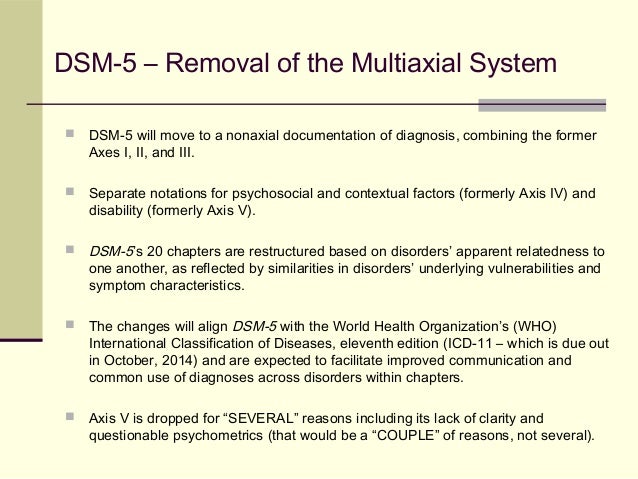

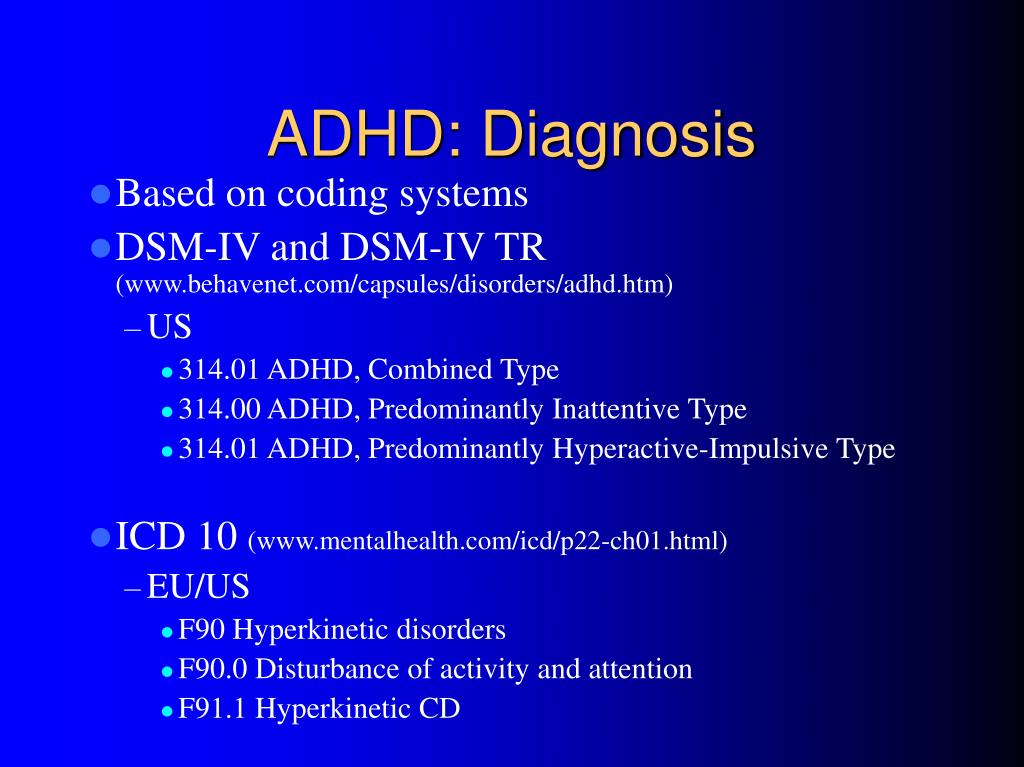

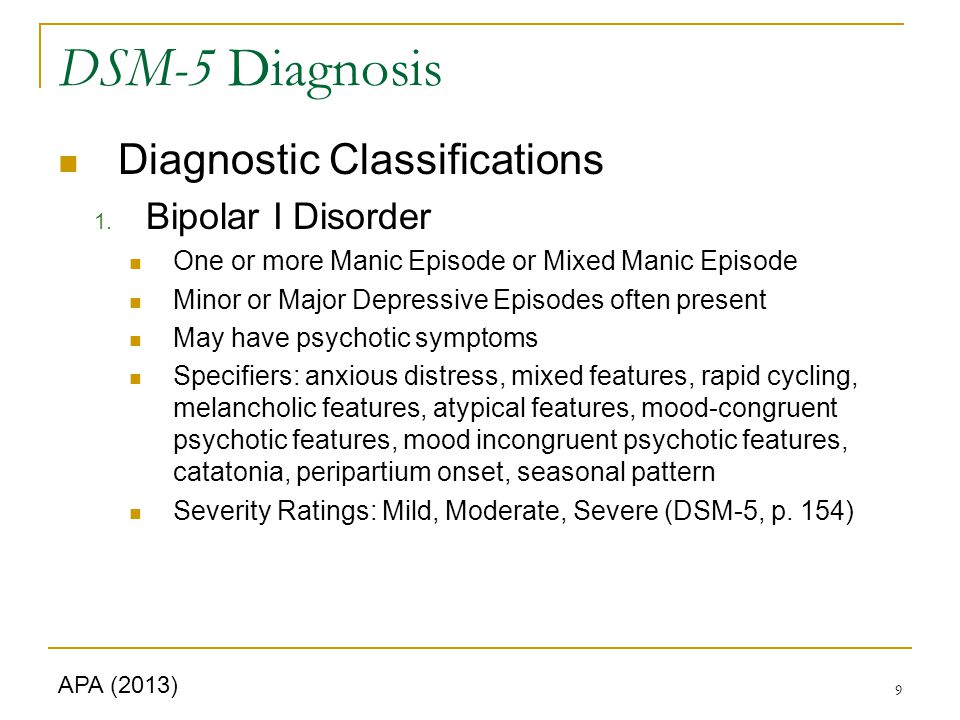

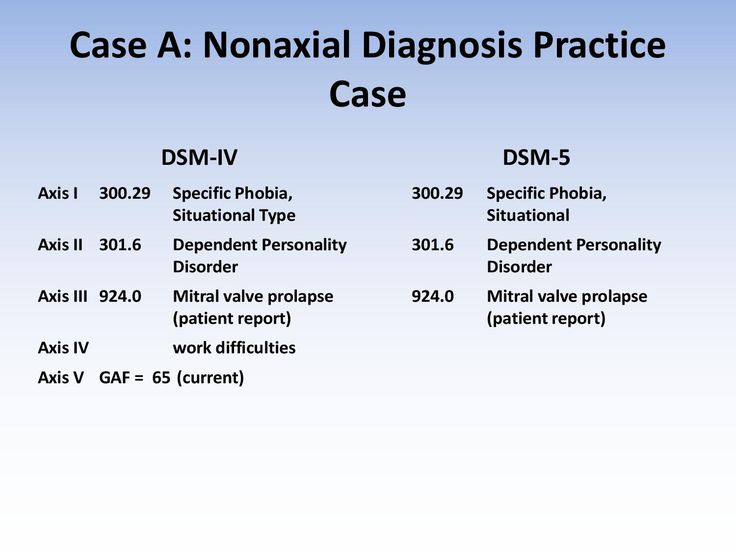

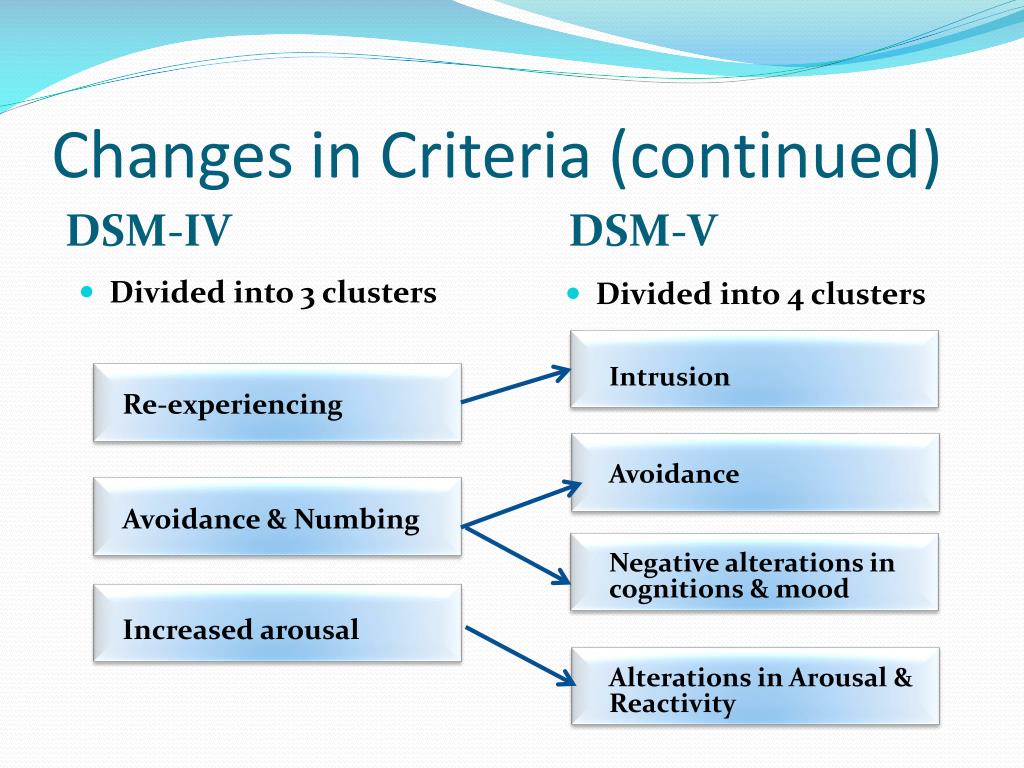

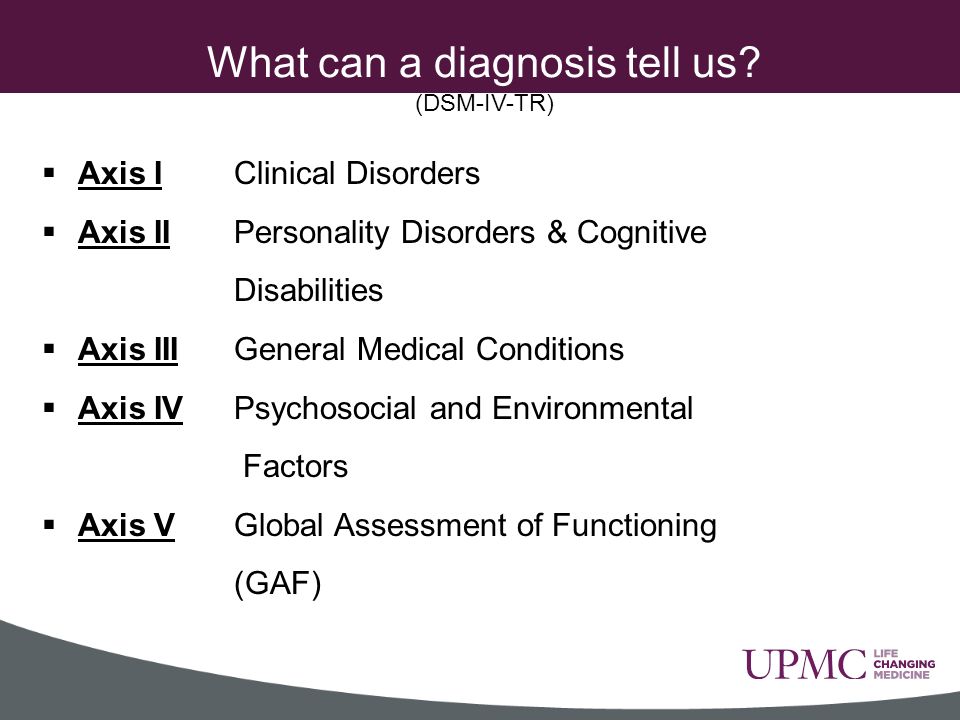

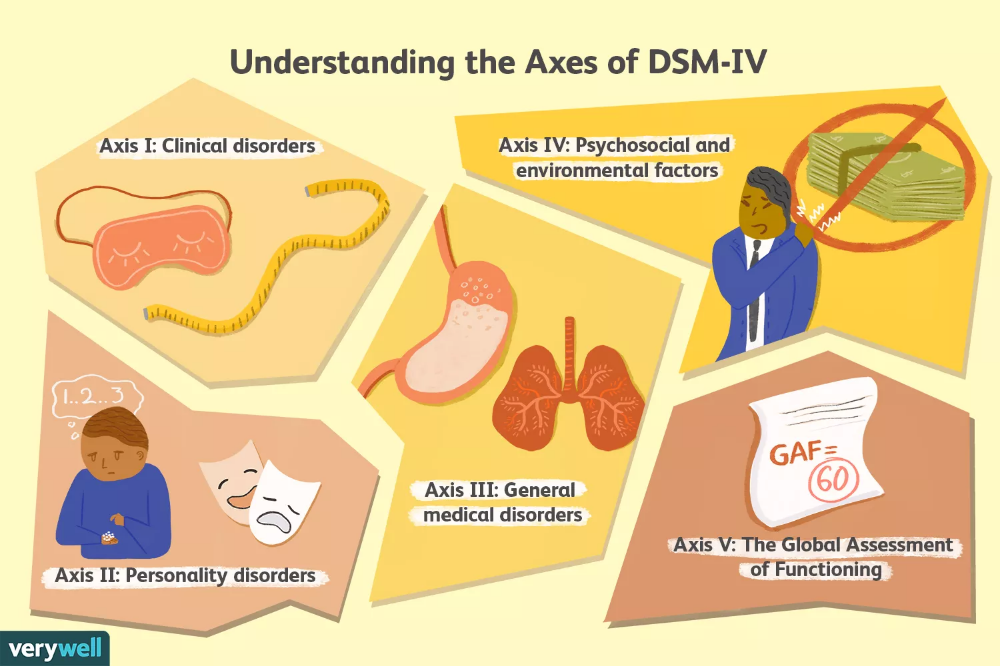

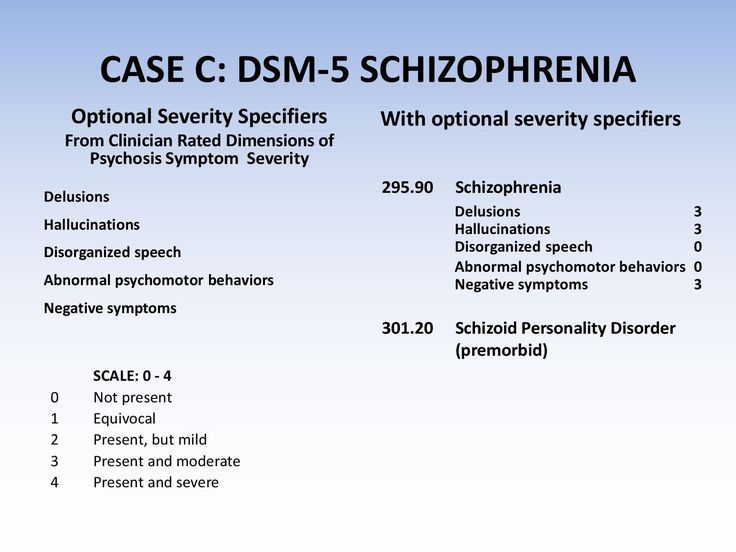

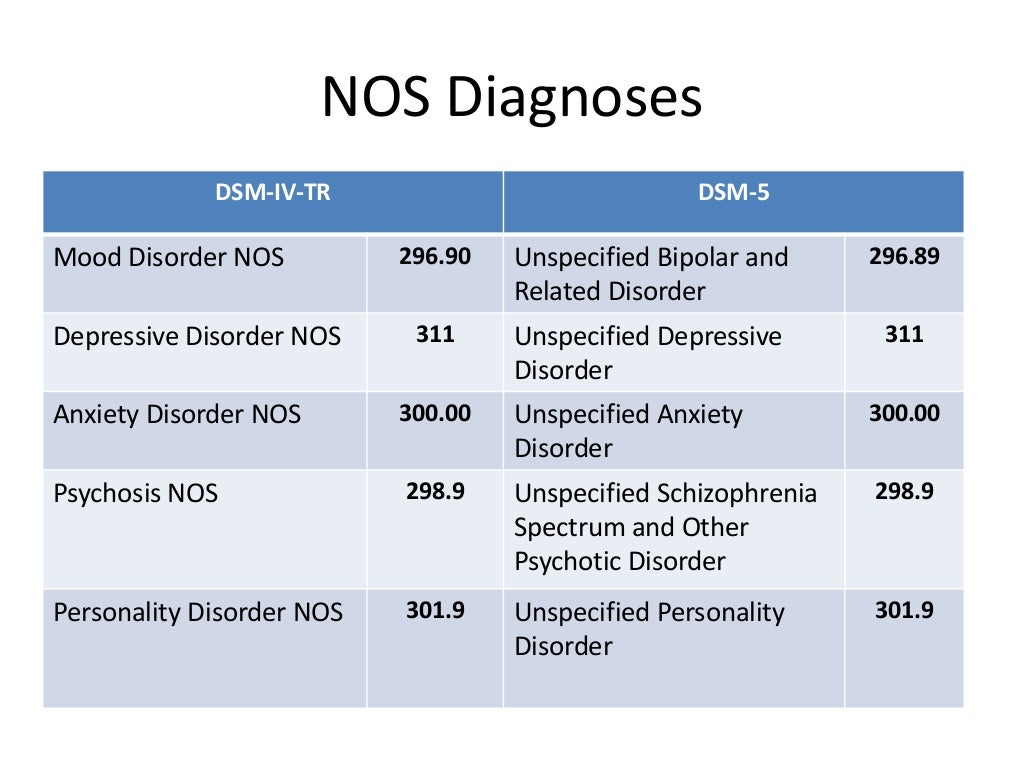

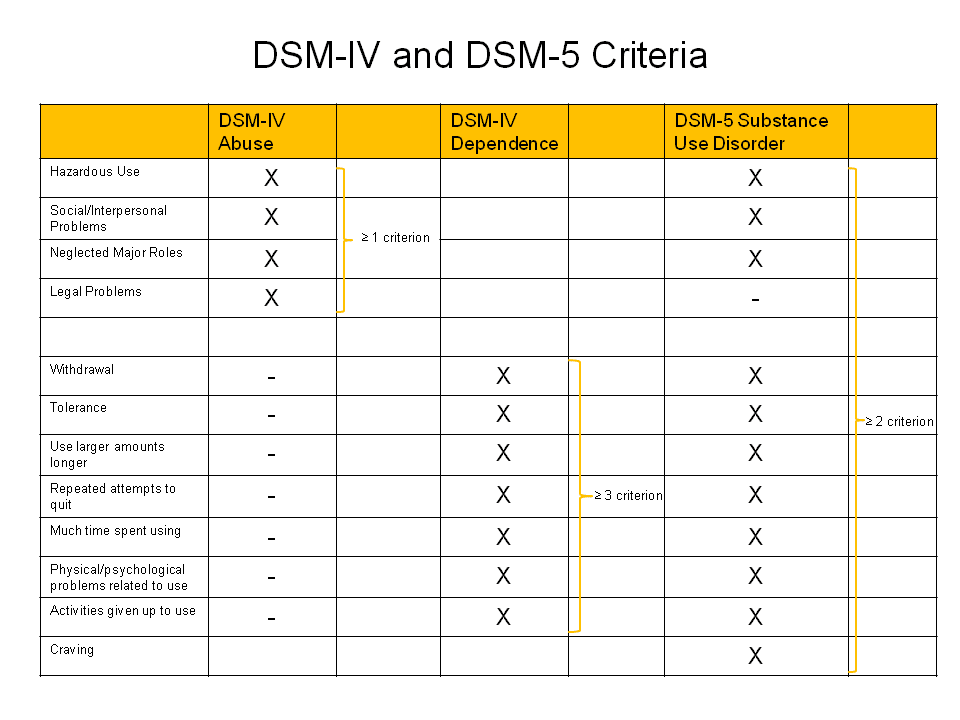

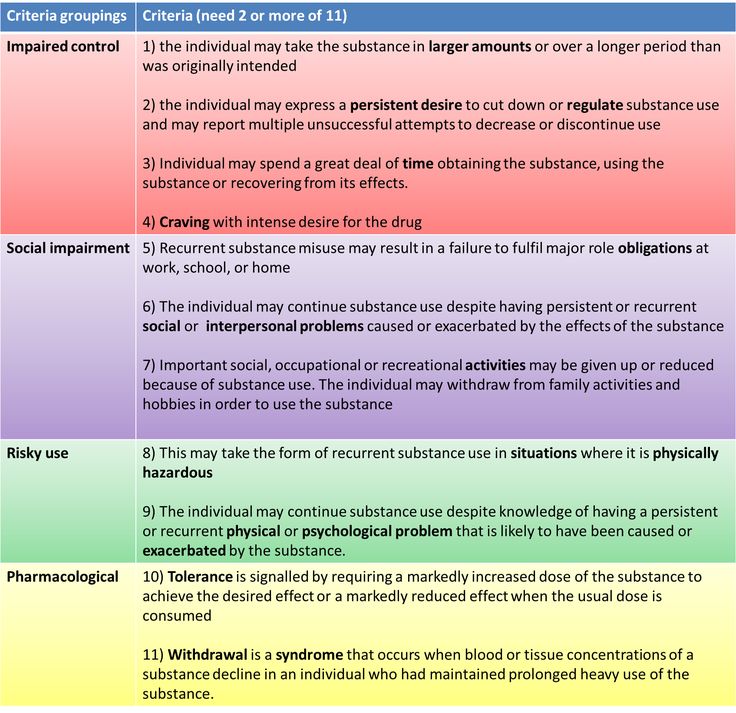

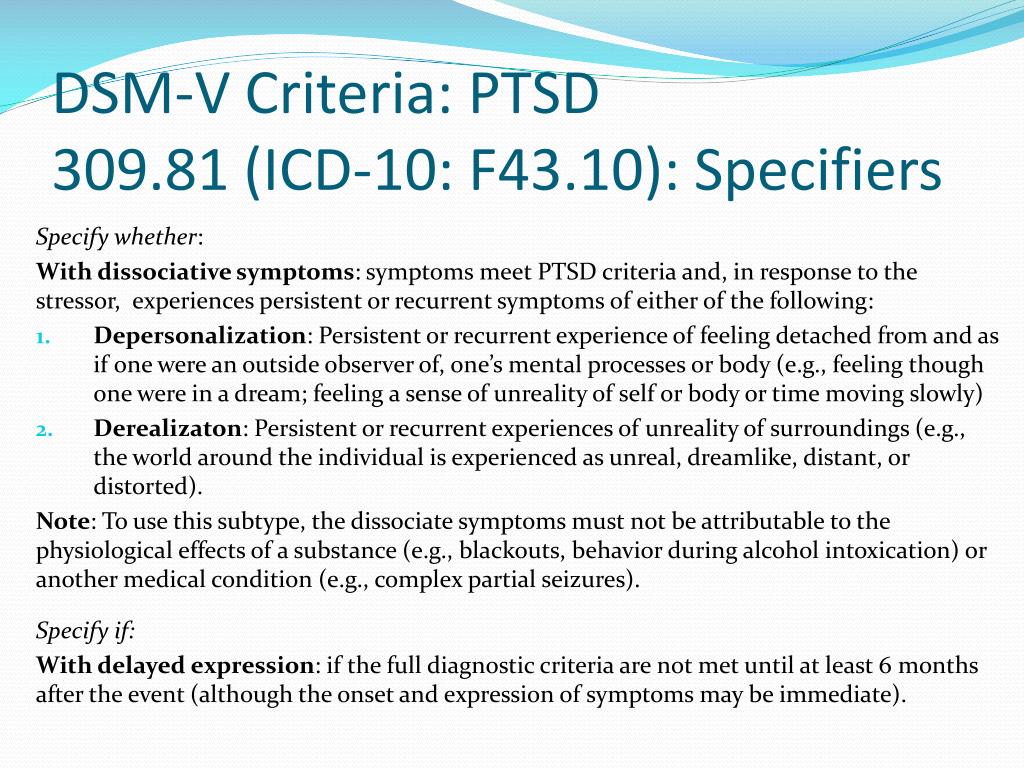

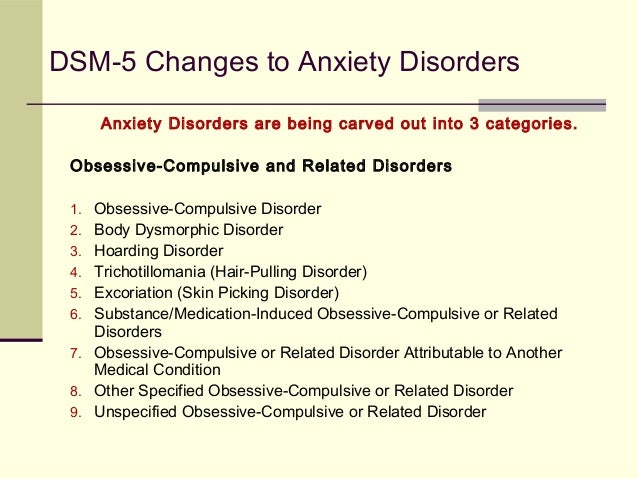

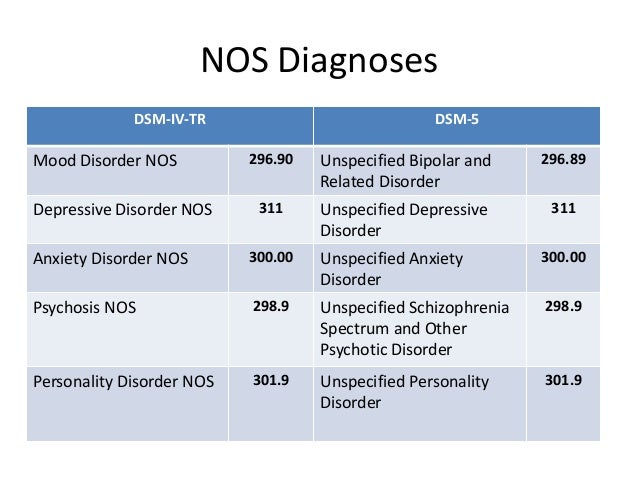

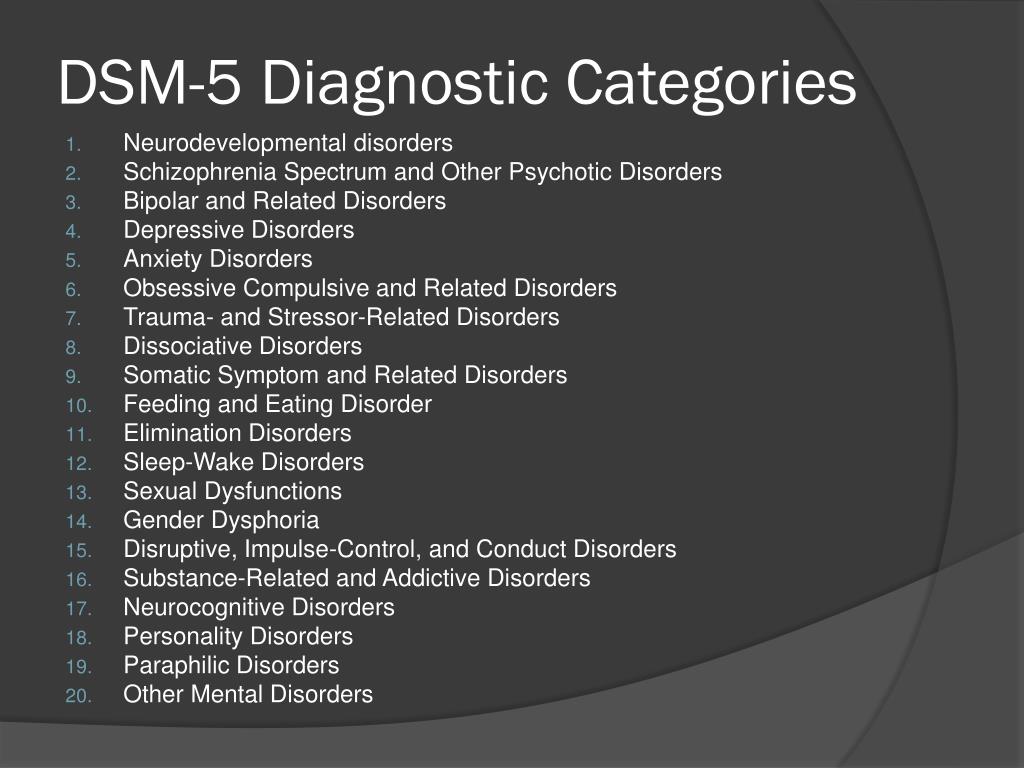

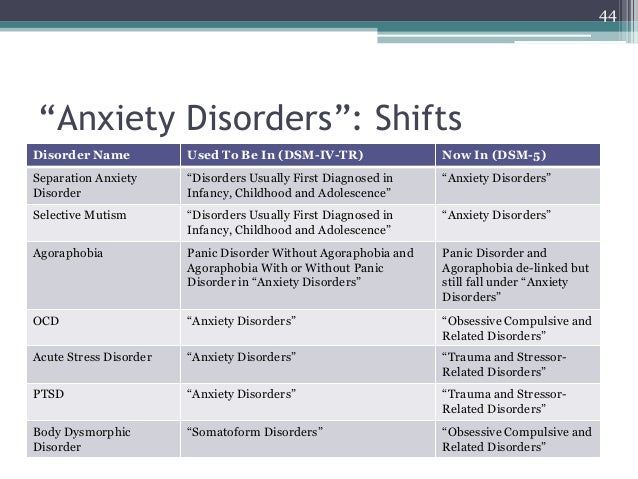

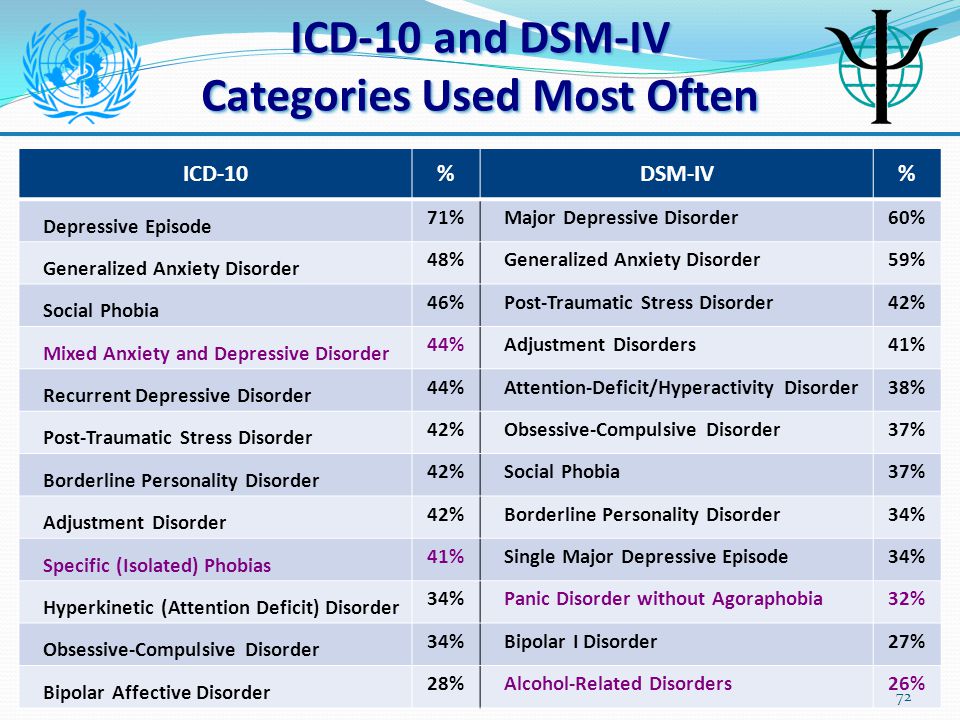

According to ICD-10 classification, adjustment disorder is classified under the category of reaction to severe stress and adjustment disorders (F43). This category includes acute stress reaction (F43.0), post-traumatic stress disorder (F43.1) (PTSD), adjustment disorder (F43. 2), other reactions to severe stress (F43.8), reaction to severe stress unspecified (F43.9). As per DSM IV, adjustment disorder (309) is a separate diagnostic category. Acute stress disorder and PTSD are given separate diagnostic categories in DSM IV TR. The conceptualization of adjustment disorder according to various diagnostic systems is shown in and the various subtypes of the disorder are shown in .

2), other reactions to severe stress (F43.8), reaction to severe stress unspecified (F43.9). As per DSM IV, adjustment disorder (309) is a separate diagnostic category. Acute stress disorder and PTSD are given separate diagnostic categories in DSM IV TR. The conceptualization of adjustment disorder according to various diagnostic systems is shown in and the various subtypes of the disorder are shown in .

Table 1

ICD 10 and DSM IV TR conceptualization of adjustment disorder

Open in a separate window

Table 2

Subtypes of adjustment disorder

Open in a separate window

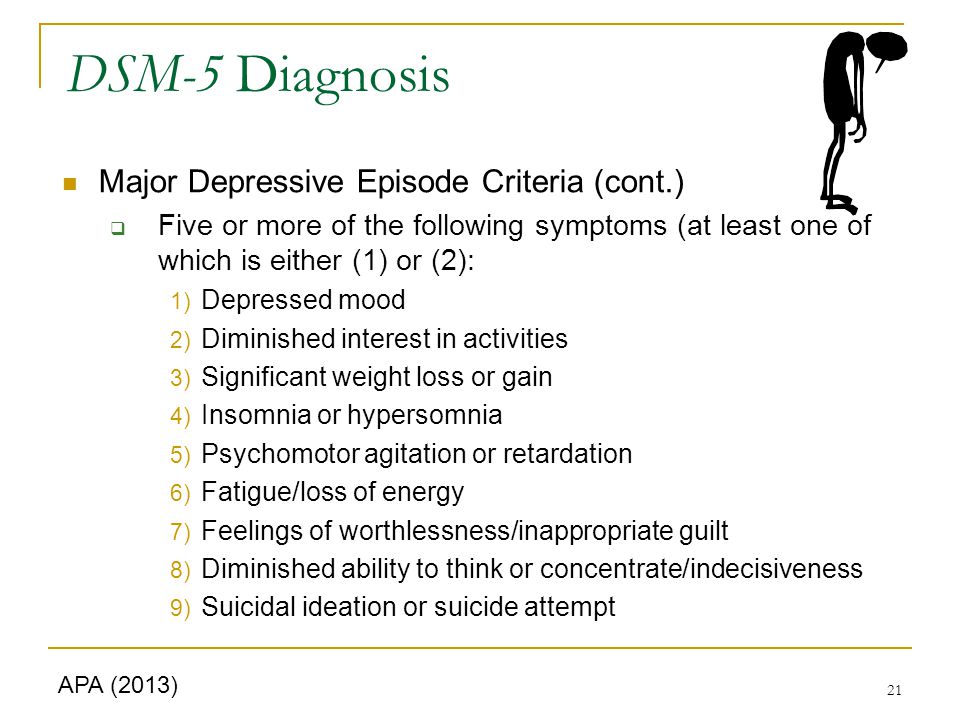

While considering a diagnosis of adjustment disorder, a few differential diagnoses should be kept in mind []. Normal nonpathological reaction to stress which is appropriate to the stressful situation should be looked for to avoid over diagnosis of adjustment disorder. Personal circumstances and context of the stressor, relation between symptom severity and stressor, persistence beyond the expected time period, cultural norms for emotional response/expression and duration and severity of dysfunction can be useful guide to make a diagnosis of adjustment disorder. [3] Major depression should be considered as the diagnosis when symptoms meet the diagnostic threshold of depression. Exacerbation of maladjustment in personality disorders when faced with severe stress can result in symptoms of adjustment disorder. The premorbid functioning and coping patterns may help to discern personality disorders. Acute stress reaction occurs in response to extreme stressor in which specific constellation of symptoms is encountered, i.e., daze, withdrawal or agitation. A mixed and changing pattern is seen and the symptoms abate after 3 days. PTSD occurs as a consequence of extreme stressor and has characteristic symptoms of re-experiencing like flashbacks and nightmares, associated with autonomic arousal and avoidance of stimuli.[4]

[3] Major depression should be considered as the diagnosis when symptoms meet the diagnostic threshold of depression. Exacerbation of maladjustment in personality disorders when faced with severe stress can result in symptoms of adjustment disorder. The premorbid functioning and coping patterns may help to discern personality disorders. Acute stress reaction occurs in response to extreme stressor in which specific constellation of symptoms is encountered, i.e., daze, withdrawal or agitation. A mixed and changing pattern is seen and the symptoms abate after 3 days. PTSD occurs as a consequence of extreme stressor and has characteristic symptoms of re-experiencing like flashbacks and nightmares, associated with autonomic arousal and avoidance of stimuli.[4]

Table 3

Differential diagnosis of adjustment disorder

Open in a separate window

Studies have also been conducted to establish validity of the diagnosis. In the outpatient setting, the adjustment disorder group was seen to be much closer to depressive disorder than to those with no diagnosis in the form of association with substance use and the presence of stressor. [4] Differences from depression were observed with respect to the nature of stressor and the duration of treatment. A study of medical inpatients found that patients with adjustment disorders were older, widowed, living alone, had less severe symptoms and rapid improvement compared to those with major depression.[5] As per the findings of a recent study,[6] patients with adjustment disorders had higher mental quality-of-life scores than patients with major depressive disorder but lower than patients without mental disorder. The self-perceived stress was higher in adjustment disorders when compared with those with anxiety disorders and those without mental disorder. The 10-year readmission rate of adjustment disorder was less than that for those with depressive disorder.[7] In a crisis intervention unit with 5-year follow-up, 17% developed a chronic course of primarily depressive symptoms.[8] Those with adjustment disorder had shorter duration of hospitalizations, more presented suicidality, fewer psychiatric readmissions, and rehospitalization days 2 years after discharge.

[4] Differences from depression were observed with respect to the nature of stressor and the duration of treatment. A study of medical inpatients found that patients with adjustment disorders were older, widowed, living alone, had less severe symptoms and rapid improvement compared to those with major depression.[5] As per the findings of a recent study,[6] patients with adjustment disorders had higher mental quality-of-life scores than patients with major depressive disorder but lower than patients without mental disorder. The self-perceived stress was higher in adjustment disorders when compared with those with anxiety disorders and those without mental disorder. The 10-year readmission rate of adjustment disorder was less than that for those with depressive disorder.[7] In a crisis intervention unit with 5-year follow-up, 17% developed a chronic course of primarily depressive symptoms.[8] Those with adjustment disorder had shorter duration of hospitalizations, more presented suicidality, fewer psychiatric readmissions, and rehospitalization days 2 years after discharge. [9] Thus attempts have been made to validate adjustment disorders as a separate entity.

[9] Thus attempts have been made to validate adjustment disorders as a separate entity.

Reliability studies of adjustment disorder have been found to be lower than some other psychiatric disorders. Inter-rater agreement for adjustment disorder was not found to be significant in a survey of psychiatrists and psychologists using 27 child and adolescent case histories. The results of the UK-WHO study of reliability of the ICD-9 categories were also consistent with such a finding. The inter-rater reliability for adjustment disorder was 0.23, which was lower than that for many other categories.[2]

The criteria of adjustment disorders have been subjected to several questions, shadowing concern over the diagnosis per se and the process of making this diagnosis.

The first criterion of adjustment disorder is temporal relationship to a stressor. The psychological symptoms are etiologically related to the stressor. The etiological concept is similar to organic mental disorder which is at a variance with the atheoretical approach of ICD 10 and DSM IV TR, which are based on phenomenological observations. Also, what constitutes a ‘stressor’ is not clearly defined, and quantifiable and qualifiable criteria of this stressor are lacing.[1] Moreover, the presence of stressor is not restricted to adjustment disorder. Despland et al.[4] found that 100% patients of adjustment disorder had recent life events, while 83% of those with major depression also had associated recent life events. There was recommendation for extension in time period, to allow for delayed onset AD, but this is uncommon even in PTSD.

Also, what constitutes a ‘stressor’ is not clearly defined, and quantifiable and qualifiable criteria of this stressor are lacing.[1] Moreover, the presence of stressor is not restricted to adjustment disorder. Despland et al.[4] found that 100% patients of adjustment disorder had recent life events, while 83% of those with major depression also had associated recent life events. There was recommendation for extension in time period, to allow for delayed onset AD, but this is uncommon even in PTSD.

The second criterion is clinically significant symptoms (in excess what would be expected). The concept of normalcy is vague. What constitutes a normal response varies greatly across culture and social groups. Seeking treatment should not be a proxy measure of severity of illness to decide about the clinical diagnosis. Considering socially inevitable human adjustment problems as pathological may lead to medicalization of problems of living.[10]

The next criterion for diagnosing adjustment disorder is exclusion of other psychiatric disorders. A study comparing adjustment disorder and depressive episode failed to identify distinguishing symptom profiles and differences on any specific variable.[11] The disorder lacks a specific symptom profile as its own, and at times is used as a waste basket diagnosis.

A study comparing adjustment disorder and depressive episode failed to identify distinguishing symptom profiles and differences on any specific variable.[11] The disorder lacks a specific symptom profile as its own, and at times is used as a waste basket diagnosis.

The adjustment disorder diagnosis excludes bereavement reaction. Special consideration has been given to bereavement reaction, but not to other stressors which may have equally distressing impact, for example, being diagnosed with a terminal illness. It also does not cater to a prolonged or complicated grief where the symptoms may emerge later, last longer or have severe symptoms. The category of complicated grief disorder has been proposed as a separate entity.[12]

ICD-10 lacks a criterion of “clinical significance,” though some disability in performing daily routine is mentioned. Hence the threshold of making the diagnosis may widely vary from center to center and person to person. Also, the symptoms should arise within 1 month of stressor for a diagnosis of adjustment disorder. Some life events take a longer period of organizational change, and emotional reactions may be delayed. Which time period is appropriate and adequate to make a diagnosis is not clear.

Some life events take a longer period of organizational change, and emotional reactions may be delayed. Which time period is appropriate and adequate to make a diagnosis is not clear.

Due to the abovementioned issues and inadequacy of criteria, the research on adjustment disorder is fairly limited. This disorder is also not included in widely used psychiatric diagnostic instruments like Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) and Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). In Schedule for Clinical Assessment for Neuropsychiatry (SCAN), there is a provision for coding of adjustment disorder but no guidelines on application have been provided. Limited research has been reflected in lack of treatment guidelines.[13]

Large population based data about adjustment disorders have been sparse. Methodologically rigorous large epidemiological surveys like those of Epidemiological Catchment Area, National Co-morbidity Survey, and National Psychiatric Morbidity Survey do not evaluate adjustment disorder. However, some effort has been made to assess the prevalence of adjustment disorder. The Outcome of Depression International Network (ODIN) project shows adjustment disorder in less than 1% of population.[14] A recent study[15] in the general population found the prevalence of adjustment disorder to be 0.9%, when the criterion of clinically significant impairment was considered. A further 1.4% of the sample was diagnosed with adjustment disorder without fulfilling the impairment criterion.

However, some effort has been made to assess the prevalence of adjustment disorder. The Outcome of Depression International Network (ODIN) project shows adjustment disorder in less than 1% of population.[14] A recent study[15] in the general population found the prevalence of adjustment disorder to be 0.9%, when the criterion of clinically significant impairment was considered. A further 1.4% of the sample was diagnosed with adjustment disorder without fulfilling the impairment criterion.

Adjustment disorders are commonly seen in primary care settings in which the 1-year prevalence varies from 11% to 18% of those with any clinical psychiatric disorder.[16,17] A recent cross-sectional survey of 3815 patients from 77 primary healthcare centers found the prevalence of adjustment disorders to be 2.94%.[6] A study of patients admitted through the psychiatric emergency showed that 7.1% of the adults and 34.4% of the adolescents had adjustment disorders at time of admission, though the diagnosis in some patients changed during rehospitalization. [9] A study from Belgium by Bruffaerts et al.[18] found adjustment disorder in 17.1% of patients presenting to psychiatric emergency setting. Among patients admitted to a public sector psychiatric inpatient unit during a 6-month period, adjustment disorder was diagnosed in 9% of patients (third most common diagnosis after psychotic illness in 62% and mood disorders in 24%).[19]

[9] A study from Belgium by Bruffaerts et al.[18] found adjustment disorder in 17.1% of patients presenting to psychiatric emergency setting. Among patients admitted to a public sector psychiatric inpatient unit during a 6-month period, adjustment disorder was diagnosed in 9% of patients (third most common diagnosis after psychotic illness in 62% and mood disorders in 24%).[19]

Adjustment disorders have also been widely studied in consultation liaison practice. A multisite study in consultation psychiatry services of seven teaching hospitals in the United States, Canada, and Australia examined 1039 consecutive referrals.[20] A diagnosis of adjustment disorder was made in 12.0% of psychiatric consultations, being the sole diagnosis in 7.8% and comorbid with other Axis I and II diagnoses in 4.2%. In further 10.6% patients, it was also considered as a rule-out diagnosis. Among the subtypes, adjustment disorder with depressed mood was the most frequent. AD was diagnosed in 15%, 7%, and 7% of those with personality disorder, organic mental disorder, and psychoactive substance abuse disorder respectively. Two older studies on the general hospital population found the prevalence rate of adjustment disorder with depressed mood to be 13.77% in inpatients, and 11.5% of psychiatric referrals.[5,21] Adjustment disorder was found to be the most common diagnosis (7.1%) among 127 postsurgery breast cancer patients.[22] Another study from Japan shows the prevalence of adjustment disorder to be 35% in case of recurrence on breast cancer.[23] In the acutely ill medical inpatient unit, adjustment disorder was found to be the most common axis-1 disorder (13.7%) followed by anxiety disorder (5.8%), alcohol abuse (5.4%), and major depressive disorder (5.1%) according to DSM-IV diagnostic criteria.[24] A recent large meta-analysis shows the prevalence of adjustment disorder to be 15.4% in adults with cancer in oncological, hematological, and palliative-care settings.[25]

Two older studies on the general hospital population found the prevalence rate of adjustment disorder with depressed mood to be 13.77% in inpatients, and 11.5% of psychiatric referrals.[5,21] Adjustment disorder was found to be the most common diagnosis (7.1%) among 127 postsurgery breast cancer patients.[22] Another study from Japan shows the prevalence of adjustment disorder to be 35% in case of recurrence on breast cancer.[23] In the acutely ill medical inpatient unit, adjustment disorder was found to be the most common axis-1 disorder (13.7%) followed by anxiety disorder (5.8%), alcohol abuse (5.4%), and major depressive disorder (5.1%) according to DSM-IV diagnostic criteria.[24] A recent large meta-analysis shows the prevalence of adjustment disorder to be 15.4% in adults with cancer in oncological, hematological, and palliative-care settings.[25]

The course and outcome have also been studied for adjustment disorders. After 5-year follow-up of 100 patients, 71% adults and 44% adolescents with adjustment disorder were well. The adult group developed major depressive disorder and alcohol abuse while adolescents developed a wider range psychiatric disorder like schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, antisocial personality disorder, drug abuse, and major depressive disorder. The predictors of poor outcome were chronicity and behavioral disturbances.[26] The risk of suicide in adjustment disorder was found to be 4%, mostly along with presence of alcohol abuse. The interval between suicidal communication and act was less than 1 month in adjustment disorder, which was lesser compared with other disorders (depression 3 months, bipolar disorder 30 months, and schizophrenia 47 months).[27] One recent study on psychological autopsy of suicide found that 15% had adjustment disorder.[28]

The adult group developed major depressive disorder and alcohol abuse while adolescents developed a wider range psychiatric disorder like schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, antisocial personality disorder, drug abuse, and major depressive disorder. The predictors of poor outcome were chronicity and behavioral disturbances.[26] The risk of suicide in adjustment disorder was found to be 4%, mostly along with presence of alcohol abuse. The interval between suicidal communication and act was less than 1 month in adjustment disorder, which was lesser compared with other disorders (depression 3 months, bipolar disorder 30 months, and schizophrenia 47 months).[27] One recent study on psychological autopsy of suicide found that 15% had adjustment disorder.[28]

Future recommendations

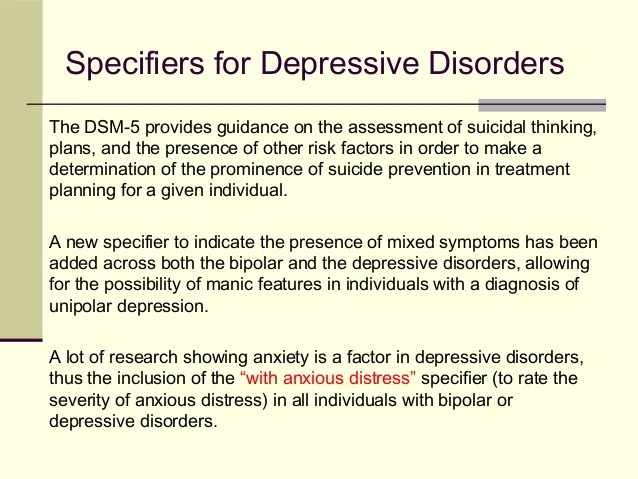

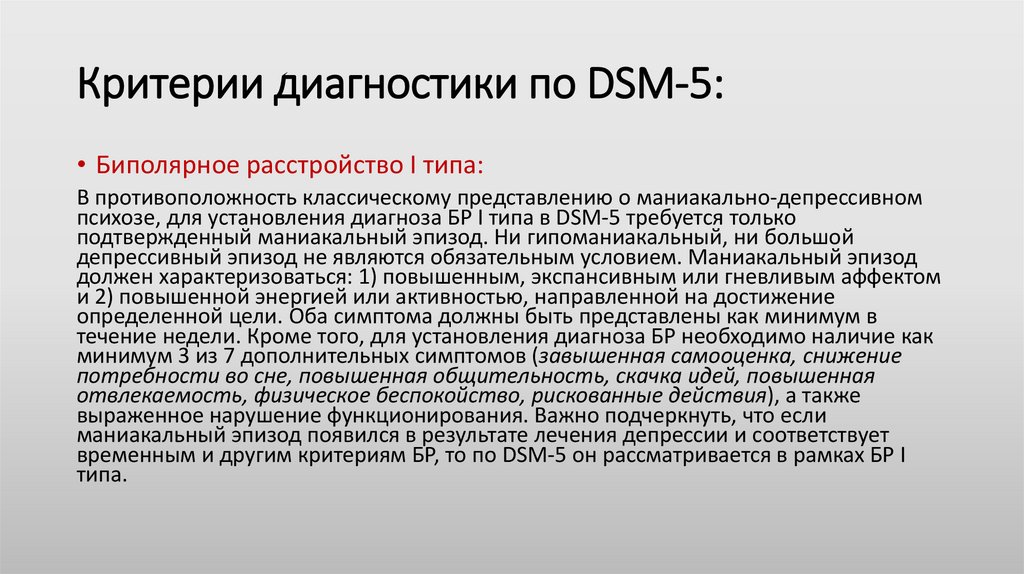

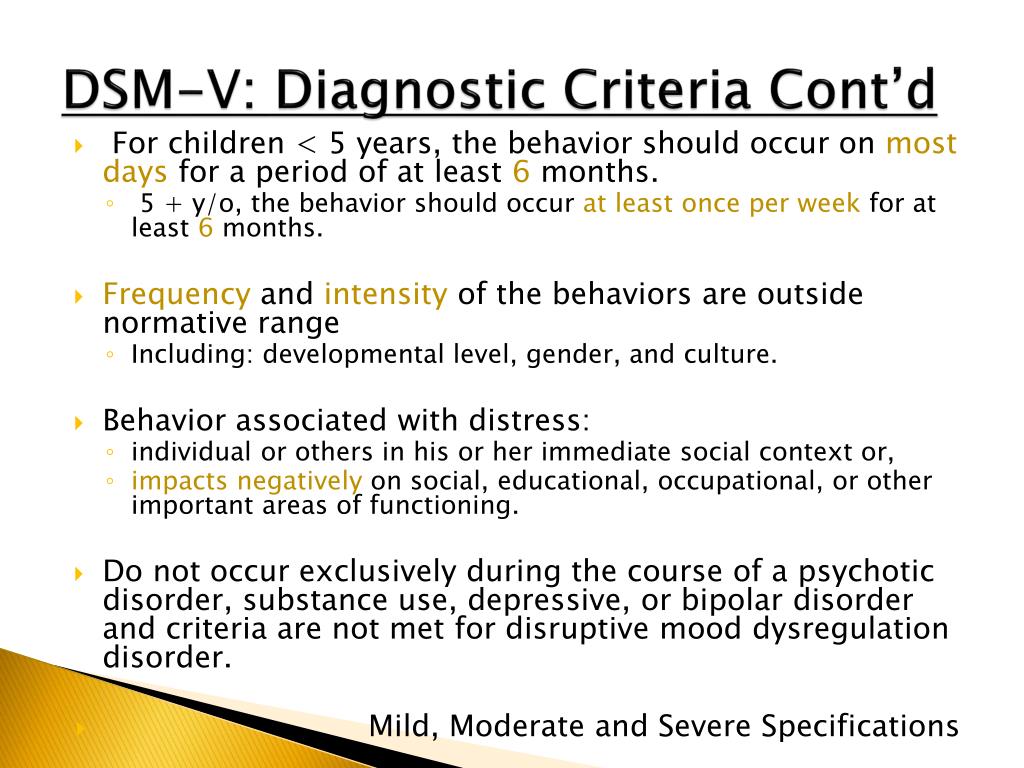

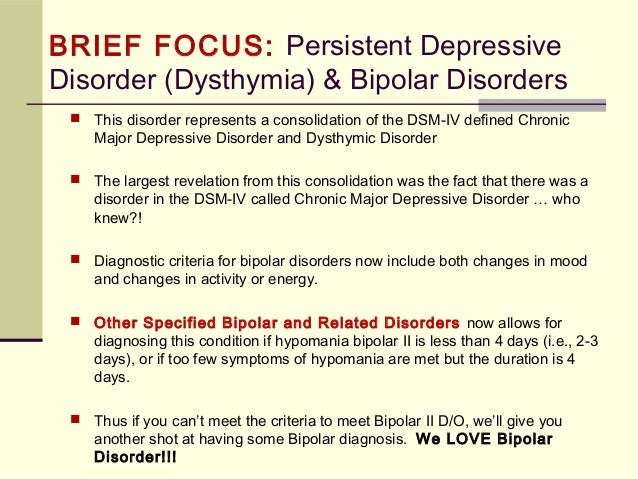

The DSM V work group on adjustment disorders proposes some revisions to the diagnostic criteria.[29] The disorder requires symptoms starting within 3 months in response to identifiable stressor (longer duration of onset for bereavement). The external context and cultural factors also need to be assessed additionally while evaluating the severity and impact of stressor. Additional specifiers have suggested that include those with features of acute stress disorder or posttraumatic stress disorder, and those related to bereavement. For the bereavement subtype, symptoms may arise within 12 months for adults and 6 months for children after the death of a close relative or friend. The severity criterion in view of the shift toward dimensionality in DSM V is still to be finalized as of writing of this text. The work group also proposes persistent complex bereavement disorder for further study in Section III, which encompasses conditions that require further research.

The external context and cultural factors also need to be assessed additionally while evaluating the severity and impact of stressor. Additional specifiers have suggested that include those with features of acute stress disorder or posttraumatic stress disorder, and those related to bereavement. For the bereavement subtype, symptoms may arise within 12 months for adults and 6 months for children after the death of a close relative or friend. The severity criterion in view of the shift toward dimensionality in DSM V is still to be finalized as of writing of this text. The work group also proposes persistent complex bereavement disorder for further study in Section III, which encompasses conditions that require further research.

It has been suggested to remove the subordination of adjustment disorder to other psychiatric diagnosis. Though stressors may trigger any other specific axis 1 disorder, adjustment disorder diagnosis to be made when there is a clear temporal relationship to the stressor and a spontaneous recovery is anticipated when stressor is removed. It has been suggested that the bereavement exclusion should be extended to other events when stressor is severe.[12] A system of symptom weighting and paying more attention to the cognitive proximity between the stressor, the symptoms and mood reactivity can be considered to reduce diagnostic ambiguities. A combined dimensional and categorical approach to classification may help to identify the longitudinal course of adjustment disorder.[30]

It has been suggested that the bereavement exclusion should be extended to other events when stressor is severe.[12] A system of symptom weighting and paying more attention to the cognitive proximity between the stressor, the symptoms and mood reactivity can be considered to reduce diagnostic ambiguities. A combined dimensional and categorical approach to classification may help to identify the longitudinal course of adjustment disorder.[30]

Some authors have proposed other subtypes and variants of adjustment disorder. Post-traumatic embitterment symptoms has been suggested to consist of mixture of despair, dysphoria, aggression, accusation, feeling of injustice, disturbed sleep and appetite, and intrusive memory. These symptoms are precipitated after an exceptional negative life event. The main emotional response is embitterment and feeling of injustice. Emotional modulation is unimpaired and the duration is more than 3 months.[31,32] Another entity, psychosomatic characterization is accompanied with demoralization, irritable mood, health anxiety, and denial. This may offer more specific clinical indication.[33]

This may offer more specific clinical indication.[33]

Adjustment disorder is a common psychiatric disorder, but has received limited attention in research settings. Many pitfalls in diagnostic criteria need to be addressed, though the concept has fair utility in the clinical setting. In both psychiatric and general medical setting, the diagnosis of adjustment disorder is a useful clinical construct, especially when patients are faced with considerable physical and psychological stresses. Further systematic research about this disorder may help in strengthening evidence base and enabling better clinical decisions.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None.

1. Strain JJ, Diefenbacher A. The adjustment disorders: The conundrums of the diagnoses. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49:121–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Katzman J, Geppert C. Adjustment disorders. In: Sadock B, Sadock V, Ruiz P, editors. Kaplan and sadock's comprehensive textbook of psychiatry. 9th ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2009. pp. 2187–96. [Google Scholar]

9th ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2009. pp. 2187–96. [Google Scholar]

3. Casey P. Adjustment disorder: Epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. CNS Drugs. 2009;23:927–38. Association AP Diagnostic and Statistical manual of mental disorders, Fourth edition: DSM-IV-TR® American Psychiatric Pub; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Despland JN, Monod L, Ferrero F. Clinical relevance of adjustment disorder in DSM-III-4 and DSM-IV. Compr Psychiatry. 1995;36:454–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Snyder S, Strain JJ, Wolf D. Differentiating major depression from adjustment disorder with depressed mood in the medical setting. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1990;12:159–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Fernández A, Mendive JM, Salvador-Carulla L, Rubio-Valera M, Luciano JV, Pinto-Meza A, et al. Adjustment disorders in primary care: Prevalence, recognition and use of services. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;201:137–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Jones R, Yates WR, Zhou MH. Readmission rates for adjustment disorders: Comparison with other mood disorders. J Affect Disord. 2002;71:199–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Readmission rates for adjustment disorders: Comparison with other mood disorders. J Affect Disord. 2002;71:199–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Bronisch T. Adjustment reactions: A long-term prospective and retrospective follow-up of former patients in a crisis intervention ward. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1991;84:86–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Greenberg WM, Rosenfeld DN, Ortega EA. Adjustment disorder as an admission diagnosis. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:459–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Casey P. Adult adjustment disorder: A review of its current diagnostic status. J Psychiatr Pract. 2001;7:32–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Casey P, Maracy M, Kelly BD, Lehtinen V, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Dalgard OS, et al. Can adjustment disorder and depressive episode be distinguished? Results from ODIN. J Affect Disord. 2006;92:291–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Baumeister H, Hutter N, Bengel J, Härter M. Quality of life in medically ill persons with comorbid mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychother Psychosom. 2011;80:275–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Psychother Psychosom. 2011;80:275–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Carta MG, Balestrieri M, Murru A, Hardoy MC. Adjustment Disorder: Epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2009;5:15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Dowrick C, Casey P, Dalgard O, Hosman C, Lehtinen V, Vázquez-Barquero JL, et al. Outcomes of Depression International Network (ODIN). Background, methods and field trials. ODIN Group. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172:359–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Maercker A, Forstmeier S, Pielmaier L, Spangenberg L, Brähler E, Glaesmer H. Adjustment disorders: Prevalence in a representative nationwide survey in Germany. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47:1745–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Casey PR, Dillon S, Tyrer PJ. The diagnostic status of patients with conspicuous psychiatric morbidity in primary care. Psychol Med. 1984;14:673–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Blacker CV, Clare AW. The prevalence and treatment of depression in general practice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1988;95:S14–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1988;95:S14–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Bruffaerts R, Sabbe M, Demyttenaere K. Attenders of a university hospital psychiatric emergency service in Belgium-general characteristics and gender differences. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:146–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Koran LM, Sheline Y, Imai K, Kelsey TG, Freedland KE, Mathews J, et al. Medical disorders among patients admitted to a public-sector psychiatric inpatient unit. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:1623–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Strain JJ, Smith GC, Hammer JS, McKenzie DP, Blumenfield M, Muskin P, et al. Adjustment disorder: A multisite study of its utilization and interventions in the consultation-liaison psychiatry setting. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1998;20:139–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Popkin MK, Callies AL, Colón EA, Stiebel V. Adjustment disorders in medically ill inpatients referred for consultation in a university hospital. Psychosomatics. 1990;31:410–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Mehnert A, Koch U. Prevalence of acute and post-traumatic stress disorder and comorbid mental disorders in breast cancer patients during primary cancer care: A prospective study. Psychooncology. 2007;16:181–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Okamura H, Watanabe T, Narabayashi M, Katsumata N, Ando M, Adachi I, et al. Psychological distress following first recurrence of disease in patients with breast cancer: Prevalence and risk factors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2000;61:131–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Silverstone PH. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in medical inpatients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1996;184:43–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, Halton M, Grassi L, Johansen C, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: A meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:160–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Andreasen NC, Hoenk PR. The predictive value of adjustment disorders: A follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139:584–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Andreasen NC, Hoenk PR. The predictive value of adjustment disorders: A follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139:584–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Runeson BS, Beskow J, Waern M. The suicidal process in suicides among young people. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93:35–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Manoranjitham SD, Rajkumar AP, Thangadurai P, Prasad J, Jayakaran R, Jacob KS. Risk factors for suicide in rural south India. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196:26–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Anon. Proposed Revision | APA DSM-5. [Last accessed on 2012 Oct 4]. Available from: http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevision/Pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=367 .

30. Casey P, Doherty A. Adjustment disorder: Implications for ICD-11 and DSM-5. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;201:90–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Linden M. Posttraumatic embitterment disorder. Psychother Psychosom. 2003;72(4):195–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Dobricki M, Maercker A. (Post-traumatic) embitterment disorder: Critical evaluation of its stressor criterion and a proposed revised classification. Nord J Psychiatry. 2010;64(3):147–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nord J Psychiatry. 2010;64(3):147–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Grassi L, Mangelli L, Fava GA, Grandi S, Ottolini F, Porcelli P, et al. Psychosomatic characterization of adjustment disorders in the medical setting: Some suggestions for DSM-V. J Affect Disord. 2007;101:251–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

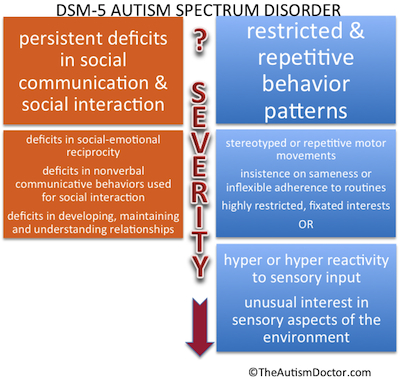

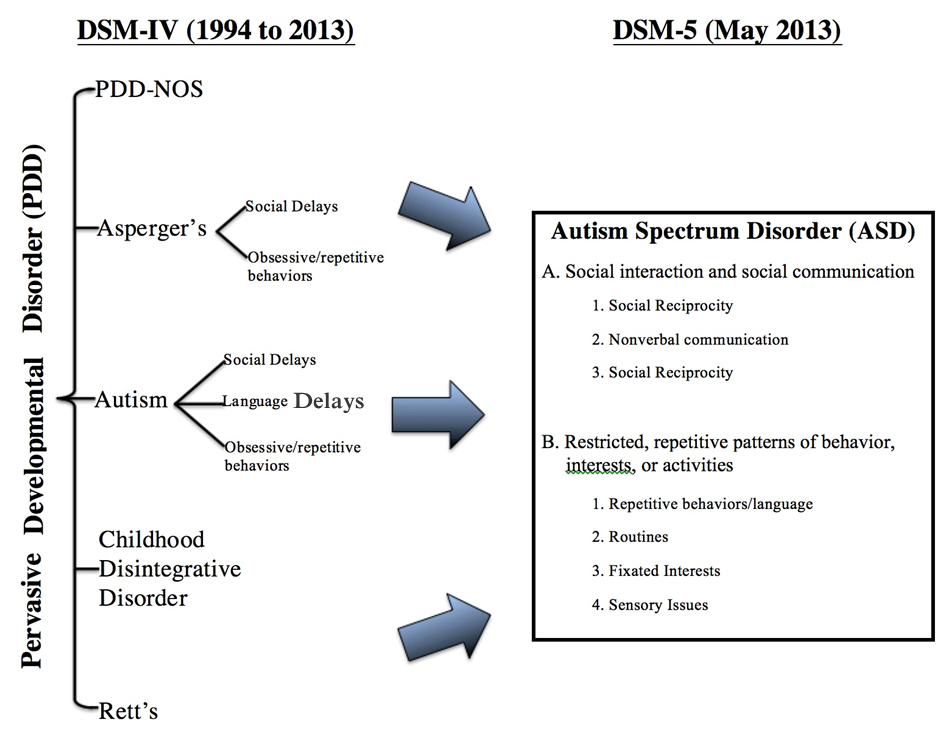

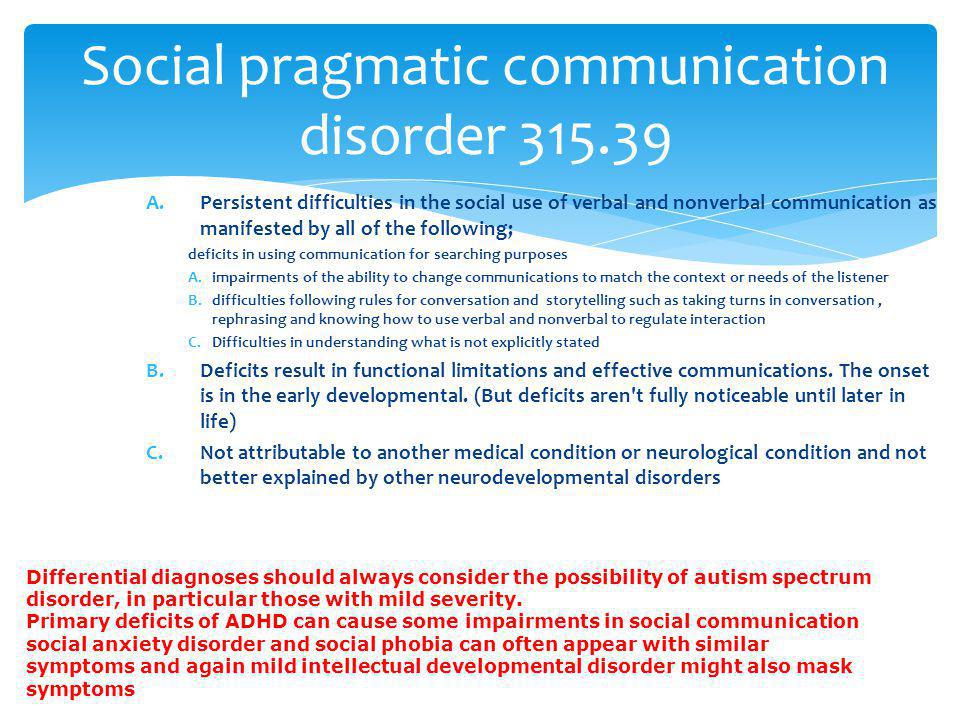

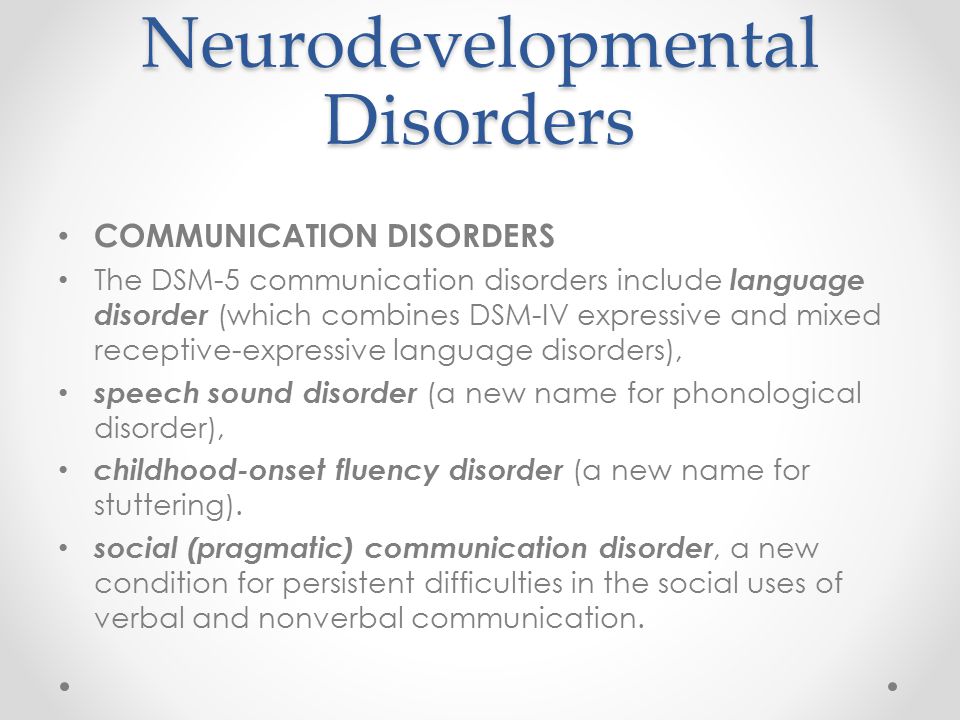

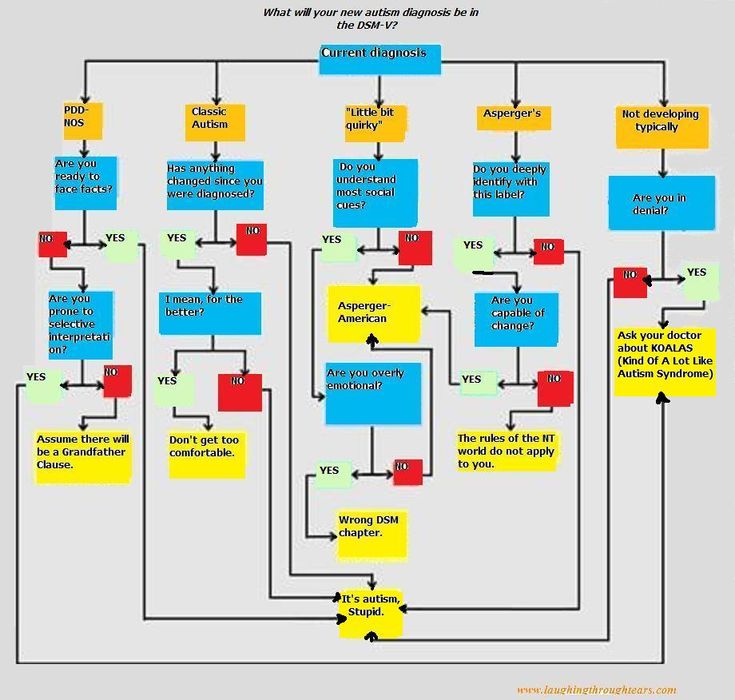

Autism spectrum disorder in DSM-5 code 299.00

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition) is a nosological system used in the United States since 2013, a “nomenclature” of mental disorders. Developed and published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). DSM-5 published May 18, 2013, supersedes DSM-IV-TR 2000.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) - A spectrum of psychological characteristics describing a wide range of abnormal behavior and difficulties in social interaction and communication, as well as severely limited interests and frequently repetitive behaviors.

Entered "Autism Spectrum Disorder":

- autism (Kanner syndrome)

- Asperger's syndrome

- childhood disintegrative disorder

- nonspecific pervasive developmental disorder

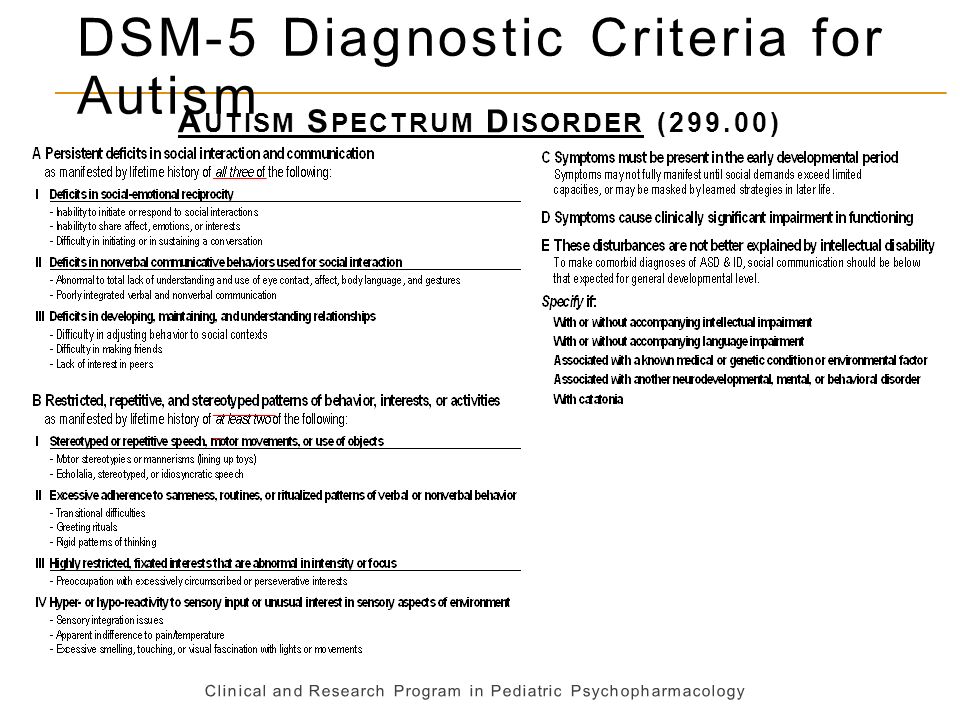

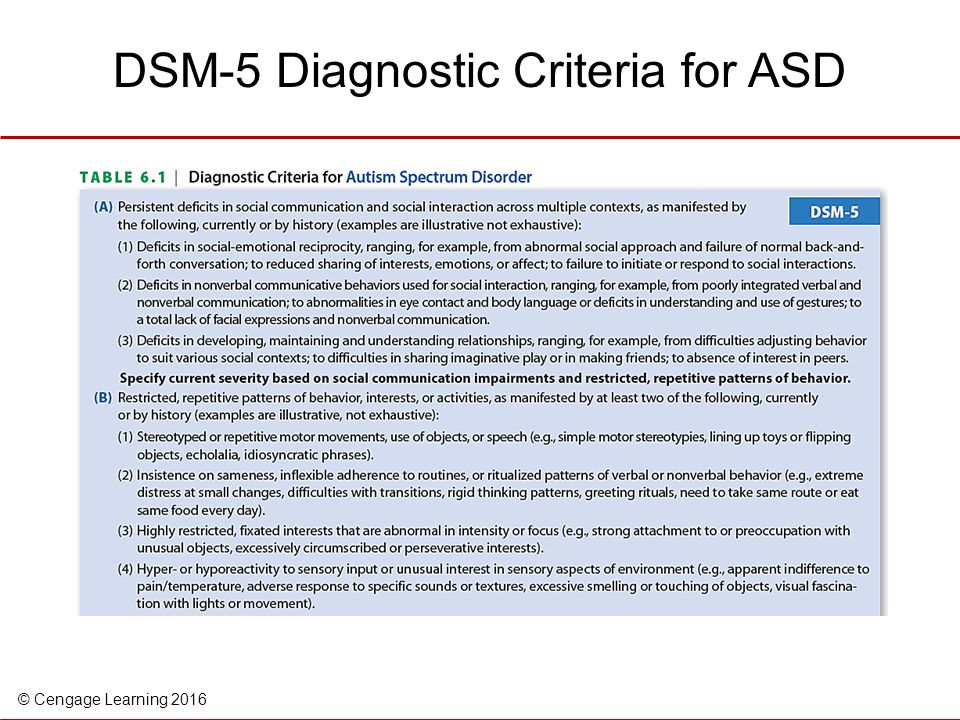

DSM-5 includes for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) 299. 00 (F84.0) the following diagnostic criteria:

00 (F84.0) the following diagnostic criteria:

A. moment or history in the following (examples are given for clarity and are not exhaustive, see text):

1. Deficiencies in social-emotional reciprocity; starting, for example, with abnormal social convergence and failures to maintain normal dialogue; to reduce the exchange of interests, emotions, as well as the impact and response; to the inability to initiate or respond to social interactions.

2. Deficiencies in non-verbal communicative behavior used in social interaction; starting, for example, with poor integration of verbal and non-verbal communication; to anomalies in eye contact and body language or deficits in understanding and using non-verbal communication; to the complete absence of facial expressions or gestures.

3. Deficiencies in establishing, maintaining and understanding social relationships; starting, for example, with difficulties in adjusting behavior to different social contexts; to difficulty participating in imaginative games and making friends; to a visible lack of interest in peers.

B. Limited, repetitive pattern of behavior, interests, or activities, as manifested by at least two of the following (examples are for illustrative purposes and are not intended to be exhaustive, see text):

1. motor movements, speech, or use of objects (eg, simple motor stereotypes, lining up toys or waving objects, echolalia, idiosyncratic phrases).

2. Excessive need for consistency, inflexible adherence to rules or patterns of behavior, ritualized forms of verbal or non-verbal behavior (eg, extreme stress at the slightest change, difficulty shifting attention, inflexible thought patterns, congratulatory rituals, insisting on a fixed route or meal ).

3. Extremely limited and fixed interests that are abnormal in intensity or direction (eg, strong attachment to or excessive preoccupation with and infatuation with unusual objects, extremely limited occupations and interests, or perseverations).

4. Over- or under-reacting to sensory input or unusual interest in sensory aspects of the environment (eg, apparent indifference to pain or environmental temperature, negative response to certain sounds or textures, excessive sniffing or touching of objects, fascination with light sources or objects in motion).

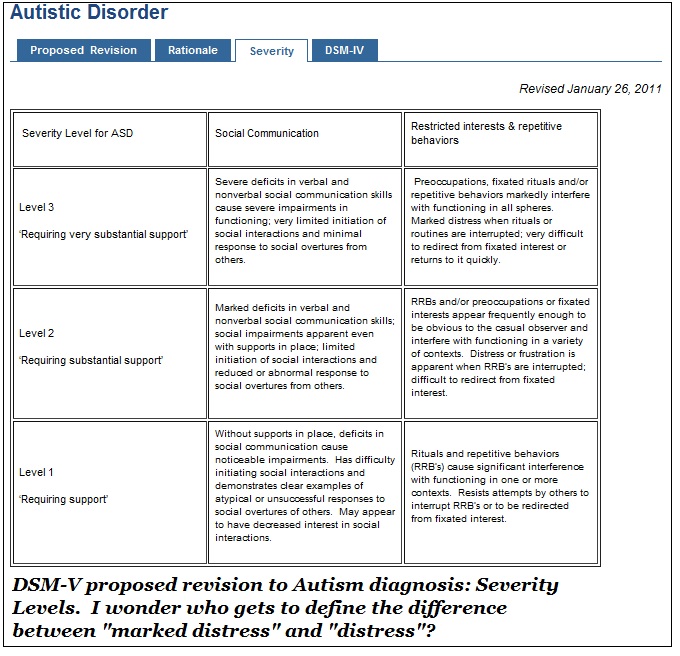

Specify severity:

Severity is based on impaired social interaction and limited, repetitive behaviors (see Table 2).

C. Symptoms must be present early in development (but may not become fully apparent until social demands exceed limited capacity, or be masked by learned strategies later in life).

D. Symptoms cause clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of daily functioning.

E. These disorders are not due to intellectual disability (mental retardation) or general developmental delay. Intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorders often coexist; in order to diagnose comorbidity between autism spectrum disorder and mental retardation, social communication must be below what is expected for the general level of development.

Note:

Individuals with well-established DSM-IV autism, Asperger's syndrome, or non-specific pervasive developmental disorder (PDD-NOS) under the DSM-V will be diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder. Individuals with significant social communication and interaction impairments whose symptoms do not meet criteria for autism spectrum disorder should undergo a diagnostic evaluation for social communication (pragmatic) disorder (315.39(F80.89)).

Additionally specify:

With/Without accompanying mental retardation (developmental delay).

With/Without an accompanying defect (speech disorder).

A disorder associated with a medical condition, or genetics, or a known environmental factor. (Coded note: Use additional code(s) to identify associated medical or genetic conditions.)

A disorder associated with impaired development, behavior, mental or other abilities of a neurological nature. (Coded note: Use additional code(s) to define neurodevelopmental mental or behavioral disorders. )

)

With/Without catatonia(s) (see criteria for catatonia associated with another psychiatric disorder, pp. 119-120, for a definition). (Coded note: Use additional code 293.89 [F06.1] for autism-related catatonia to indicate the presence of comorbid catatonia.) Severity

Severe stress and / or pronounced difficulty in changing activities or switching attention.

Severe stress and / or pronounced difficulty in changing activities or switching attention.

Sources:

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, 2013 pp. 51-53.

2. Autism Spectrum Disorder Fact Sheet, 2013, p.1

Diagnosis and classification of disorders directly related to stress: proposals for ICD-11 - World Psychiatry No.

03 2013

03 2013

Subscribe to new numbers

Diagnosis and classification of disorders directly related to stress: proposals for ICD-11 No. 03 2013

Author: Andreas Maercker1, Chris R. Brewin2, Richard A. Bryant3, Marylene Cloitre4, Mark Van Ommeren5, Lynne M. Jones6, Asma Humayan7, Ashraf Kagee8, Augusto E. Llosa9, Ce´ Cile Rousseau10, Daya J. Somasundaram11,12, Renato Souza13, Yuriko Suzuki14, Inkaweissbecker15, Simon C.Wessely16, Michael B. First17, Geoffrey M. Reed5

1Department of Psychology, Division of Psychopathology, University of Zurich, Switzerland; 2Department of Clinical, Educational and Health Psychology, University College London, London, UK; 3School of Psychology, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia; 4Division of Dissemination and Training, National Center for PTSD, Menlo Park, CA, USA; 5Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland; 6FXB Center for Health and Human Rights, Harvard School of Public Health, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA; 7Institute of Psychiatry, Benazir Bhutto Hospital, Murree Road, Rawalpindi, Pakistan; 8Department of Psychology, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa; 9Epicentre, Paris, France; 10Department of Psychiatry, McGill University Health Center, Montr_eal, Canada; 11University of Jaffna, Sri Lanka; 12Glenside Mental Health Services, Glenside, South Australia, Australia; 13International Committee of the Red Cross, Geneva, Switzerland; 14National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, National Institute of Mental Health, Tokyo, Japan; 15International Medical Corps, Washington, DC, USA; 16Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London, London, UK; 17Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY, USA

Page numbers in the issue: 190-197

The diagnostic concepts of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other stress-related disorders are intensely debated among social and neuroscientists, clinicians, epidemiologists, health care and humanitarian leaders around the world. PTSD and adjustment disorder are among the most widely used diagnoses in mental health care worldwide. This article describes proposals to improve the clinical utility of classifying disorders directly related to stress in the forthcoming 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Suggestions include a narrower concept of PTSD that does not allow for a diagnosis based on nonspecific symptoms alone; a new category of "complex PTSD", which, in addition to the core symptoms of PTSD, includes three groups of intrapersonal symptoms and symptoms related to interpersonal interaction; a new diagnosis of "prolonged grief reaction" used to characterize patients who experience an intense, painful, disabling, and abnormally persistent bereavement reaction; a significant revision of the diagnosis of "adjustment disorder", including specification of symptoms; building the concept of "acute stress response", as a normal phenomenon, which nevertheless may require clinical intervention.

PTSD and adjustment disorder are among the most widely used diagnoses in mental health care worldwide. This article describes proposals to improve the clinical utility of classifying disorders directly related to stress in the forthcoming 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Suggestions include a narrower concept of PTSD that does not allow for a diagnosis based on nonspecific symptoms alone; a new category of "complex PTSD", which, in addition to the core symptoms of PTSD, includes three groups of intrapersonal symptoms and symptoms related to interpersonal interaction; a new diagnosis of "prolonged grief reaction" used to characterize patients who experience an intense, painful, disabling, and abnormally persistent bereavement reaction; a significant revision of the diagnosis of "adjustment disorder", including specification of symptoms; building the concept of "acute stress response", as a normal phenomenon, which nevertheless may require clinical intervention. These proposals have been developed taking into account the specific aspects of their clinical use and general suitability for both low- and high-income countries.

These proposals have been developed taking into account the specific aspects of their clinical use and general suitability for both low- and high-income countries.

Keywords : classification, mental disorders, ICD, nosology, PTSD, complex PTSD, prolonged grief reaction*, cultural fit, DSM

(World Psychiatry 2013; 12:198-206)

The diagnostic concepts of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other stress-related disorders are intensely debated among social and neuroscientists, clinicians, epidemiologists, health care and humanitarian leaders around the world. PTSD and adjustment disorder are among the most widely used diagnoses in mental health care worldwide. This article describes proposals to improve the clinical utility of classifying disorders directly related to stress in the forthcoming 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Suggestions include a narrower concept of PTSD that does not allow for a diagnosis based on nonspecific symptoms alone; a new category of "complex PTSD", which, in addition to the core symptoms of PTSD, includes three groups of intrapersonal symptoms and symptoms related to interpersonal interaction; a new diagnosis of "prolonged grief reaction" used to characterize patients who experience an intense, painful, disabling, and abnormally persistent bereavement reaction; a significant revision of the diagnosis of "adjustment disorder", including specification of symptoms; building the concept of "acute stress response", as a normal phenomenon, which nevertheless may require clinical intervention. These proposals have been developed taking into account the specific aspects of their clinical use and general suitability for both low- and high-income countries.

These proposals have been developed taking into account the specific aspects of their clinical use and general suitability for both low- and high-income countries.

Key words : classification, mental disorders, ICD, nosology, PTSD, complex PTSD, prolonged grief reaction*, cultural fit, DSM

(World Psychiatry 2013; 12:198-206)

stress, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and adjustment disorder, are among the most widely used diagnoses by psychiatrists and psychologists around the world. For psychiatrists who use the ICD-10, PTSD ranks 14th in their daily clinical practice (1). Among psychologists using the ICD-10, it is the eighth most commonly used diagnosis. Among psychologists who use the DSM-IV, PTSD ranks third after generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder (2).

Stressful events can be risk factors or triggers for many mental disorders, including psychosis and depression. However, disorders directly related to stress are the only diagnoses that, in their etiology, include exposure to stressful events as a mandatory diagnostic criterion.

These diagnoses are also the subject of ongoing controversy (3,4). After the DSM-IV expanded the possibility of diagnosing PTSD to include cases where the impact of stress on a person was indirect (for example, he heard about a stressful event that happened to other people or saw it on TV), it was noted that such expansion of diagnosis blurs the boundaries of the original concept and describes the normal response to stress as a disease (3,5).

The suitability of these diagnoses across cultures is also discussed. The potential for misuse of these diagnostic categories is of particular concern in under-resourced and under-resourced countries, where their apparent simplicity makes these diagnoses easily applicable to large numbers of people who would more appropriately be seen as a normal response to extreme living conditions (6) . Another problem in these settings is that the focus on traumatic stress leads to misdiagnosis and a lack of attention to those who suffer from other widespread severe mental disorders.

Considerable controversy is also associated with the diagnosis of adjustment disorder, despite its frequent use by clinicians (1,2). Adjustment disorder is one of the most misunderstood psychiatric disorders and is often described as a wastebasket in the psychiatric classification scheme (7,8).

The forthcoming revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), currently slated for approval by the 2015 World Health Assembly, presents an opportunity for the World Health Organization (WHO) to revisit these issues and update the classification to improve clinical utility and general usability. these diagnoses (9,ten). In line with the overall organization of the revision of the ICD, a Working Group on the Classification of Disorders Directly Related to Stress was established, reporting to the International Advisory Group on the Revision of the Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders of ICD-10. This Working Group had a diverse and multidisciplinary composition of experts from all WHO regions, including from low- and middle-income countries.

The main objectives of the Working Group were to: a) review the available scientific evidence regarding disorders directly related to stress, as well as clinical and legislative information on the use and clinical utility of these diagnoses in various healthcare settings around the world, including primary and specialized assistance, b) review projects discussed during the preparation of DSM-5 in this area and assess the possibility or impossibility of their application worldwide, c) collect and prepare specific proposals, including the placement and organization of relevant categories, d) submit a draft content for these categories in the ICD-11 and related documents (including definitions, descriptions and diagnostic guidelines). Particular attention has been paid to describing disorders in different clinical settings (eg, healthcare settings or humanitarian settings) and different regions of the world, including low- and middle-income countries. The aim of the group was to identify conditions that had isolated clinical manifestations and to describe their core elements.

HISTORY

Disorders directly related to stress are a relative novelty in psychiatric classification. In the UK, the mainstream attitude towards acute stress during World War II was set out in 1942 in The Lancet by Dr. Henry Wilson, who described his experience of treating 134 patients in the London emergency department: “They all said that their reaction was due to for the fear that this fear was what they shared with all other patients and emergency workers, and, importantly, they returned to their normal work and refrained from the temptation to exaggerate the experiences they had gone through” (11). He identified reactions ranging from acute emotional disturbance to stupor and hysterical paraplegia. All of these patients were discharged within 24 hours and only six of them required further treatment over the next nine months.

However, this emphasis on normalizing responses and return to functioning has gradually shifted to more focus on lesser forms of psychopathology and an expansion of the growing mass of diagnostic categories that are considered etiologically related to stress. The ICD-8, approved by the World Health Assembly in 1965, introduced a "transitory situational disorder" that included adjustment problems, reactions to severe stress, and combat neurosis. In ICD-9, approved in 1975, two disorders were distinguished: an acute reaction to stress and an adaptation reaction. In the ICD-10, approved in 1990, in addition to acute stress reaction and adjustment disorder, two new disorders first appeared: F43.1 "Post-traumatic stress disorder" (PTSD) and F62.0 "Persistent personality change after experiencing a catastrophe", which could result from exposure to extreme stress (for example, torture or concentration camps).

The ICD-8, approved by the World Health Assembly in 1965, introduced a "transitory situational disorder" that included adjustment problems, reactions to severe stress, and combat neurosis. In ICD-9, approved in 1975, two disorders were distinguished: an acute reaction to stress and an adaptation reaction. In the ICD-10, approved in 1990, in addition to acute stress reaction and adjustment disorder, two new disorders first appeared: F43.1 "Post-traumatic stress disorder" (PTSD) and F62.0 "Persistent personality change after experiencing a catastrophe", which could result from exposure to extreme stress (for example, torture or concentration camps).

It is interesting to note that due to the influence of military psychiatry, acute stress reaction has been presented as a transient reaction occurring immediately after exposure to the stressor. It was not intended to describe a mental disorder per se, but rather to describe the general distress reactions that people typically experience in the days following exposure to traumatic events. Normally, these reactions were expected to subside within a few days (12).

Normally, these reactions were expected to subside within a few days (12).

ACTIVITIES OF WORKING GROUP

The Working Group on the Classification of Disorders Directly Related to Stress was tasked with studying and refining the classification of a mixed group of diseases, including both "Reaction to severe stress and adjustment disorders" (ICD-10 code F43) and "Persistent personality change after a disaster » (F62.0). The time frame for this work overlapped with the preparation of the DSM-5.

Within the Working Group, an agreement was reached that in this group of conditions, the stress factor is the cause of their development. These diseases are distinct from other disorders such as depression, anxiety, substance abuse or psychosomatic disorders, in which stress may be a risk factor or precipitating factor, but which may also occur in its absence.

PROPOSED CLASSIFICATION

The proposed ICD-11 classification of disorders directly related to stress covers the full range of severity from normal reactions to pathological conditions (see also 13). One of the main changes is that an acute stress response is now presented as a normal response and is therefore classified in the chapter "Factors influencing public health status and health care contact". This category is considered a legitimate target for clinical interventions, but is not defined as a mental disorder.

One of the main changes is that an acute stress response is now presented as a normal response and is therefore classified in the chapter "Factors influencing public health status and health care contact". This category is considered a legitimate target for clinical interventions, but is not defined as a mental disorder.

The draft of the new section "Disorders directly related to stress" includes "adjustment disorder", "PTSD" and "complex PTSD". In addition, for the first time, the ICD-11 will include a separate diagnosis of prolonged grief disorder. This group of diseases directly related to stress covers a set of conditions that have dissimilar psychopathological manifestations and require the previous exposure to an external stressful event or adverse experience of an extraordinary nature or degree as a reason for their development (Table 1). Events can range from less severe psychosocial stress (“life events”) to the loss of a loved one, from single traumatic events to repetitive or prolonged traumatic stress of exceptional severity. As a result, the pathology can be both mild and more severe disorders. Diagnosis of this group of disorders requires a specific, recognizable clinical picture distinct from other psychiatric disorders, as well as obvious and prolonged functional impairment.

As a result, the pathology can be both mild and more severe disorders. Diagnosis of this group of disorders requires a specific, recognizable clinical picture distinct from other psychiatric disorders, as well as obvious and prolonged functional impairment.

ICD-11 diagnoses of prolonged grief disorder, PTSD, complex PTSD, and adjustment disorder can occur in all age groups, including children and adolescents. In addition, the group includes specific attachment disorders in children, which are discussed elsewhere (14).

PRIVATE DISORDERS

PTSD

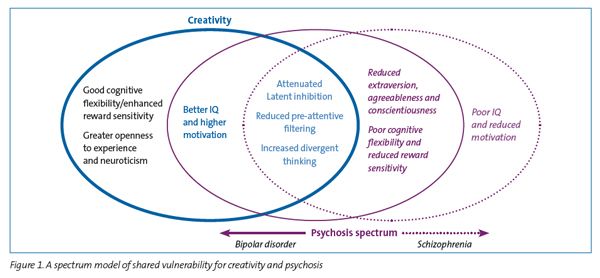

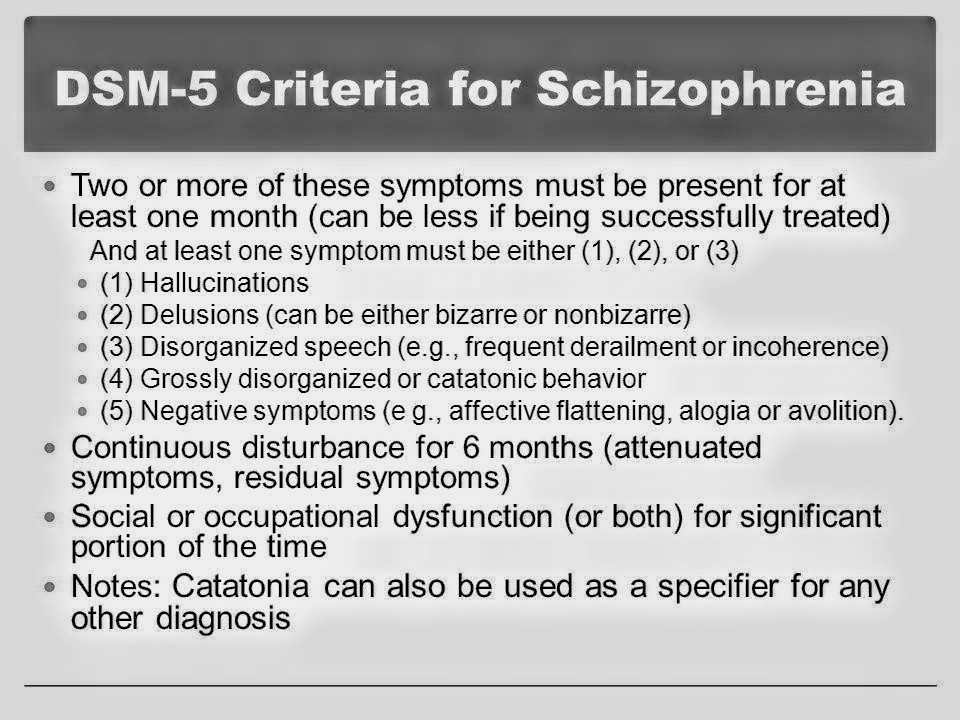

PTSD is a well-recognized clinical entity that has characteristic psychological relationships. This diagnosis is criticized for the wide combination of different clusters of symptoms, the high level of comorbidity, and in relation to the DSM-IV criteria for the fact that more than 10,000 different combinations of 17 symptoms can give this diagnosis. Several authors have called for focusing the diagnosis of this disorder on fewer major symptoms (3,15).

Studies have shown that the ICD-10 threshold for diagnosing PTSD is indeed relatively low (eg 16.17). To help distinguish PTSD from normal responses to extreme stress, a criterion for the presence of functional impairment has been proposed. In addition, a critical analysis of the empirical evidence suggested: the need to remove the statement that traumatic events "can cause general distress in almost anyone"; the need to clarify that intrusive memories are not synonymous with re-experiencing carried over into the present; an overemphasis on the importance of conscious avoidance; the need for more explicit recognition of delayed-onset PTSD (5,18). All these proposals were taken into account in the formulation of the new draft.

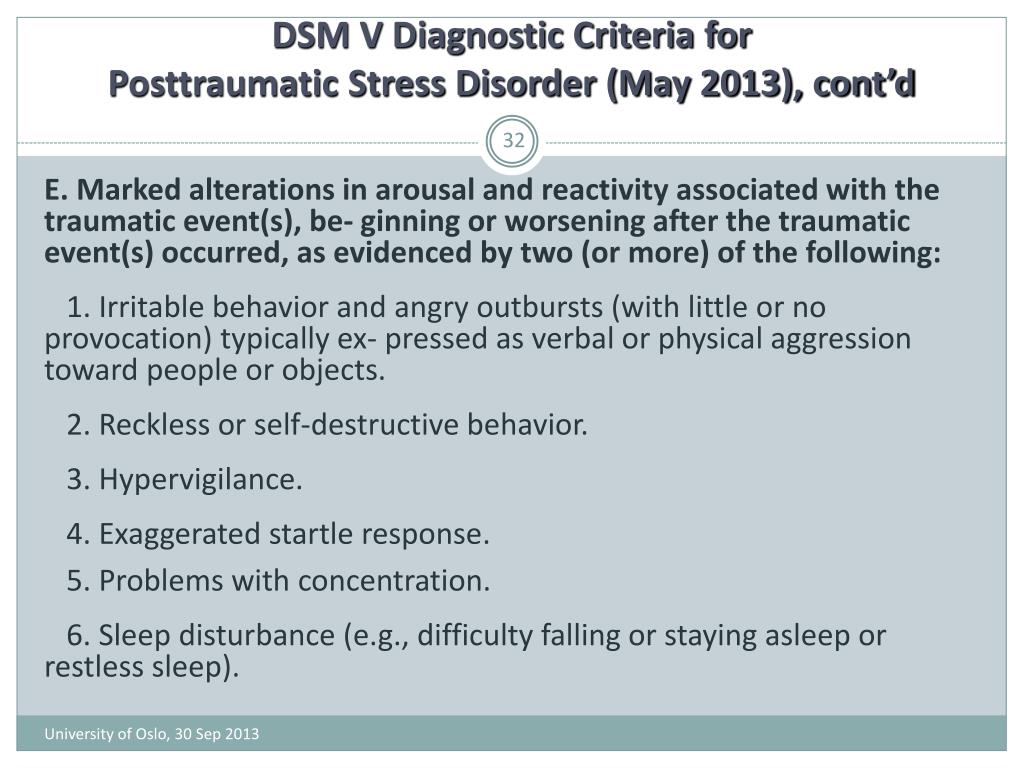

The project also seeks to increase ease of diagnosis and reduce comorbidity by identifying the core elements of PTSD rather than the "typical features" of the disorder. The first core element consists of re-experiencing the traumatic event(s) in the present as vivid intrusive memories accompanied by fear or horror, flashbacks or nightmares (see Table 1). Flashbacks are defined as vivid involuntary memories in which re-experiencing the traumatic event in the present can range from a fleeting sensation to a complete disconnection from the current environment. The second pivotal element is the avoidance of these re-experiencing, as evidenced by marked internal avoidance of thoughts and memories, or external avoidance of activities or situations that are reminiscent of the traumatic event(s). The third pivotal element is an excessive sense of continued threat in the form of heightened wakefulness levels or heightened startle responses, two symptoms of arousal that often coexist (19).

Flashbacks are defined as vivid involuntary memories in which re-experiencing the traumatic event in the present can range from a fleeting sensation to a complete disconnection from the current environment. The second pivotal element is the avoidance of these re-experiencing, as evidenced by marked internal avoidance of thoughts and memories, or external avoidance of activities or situations that are reminiscent of the traumatic event(s). The third pivotal element is an excessive sense of continued threat in the form of heightened wakefulness levels or heightened startle responses, two symptoms of arousal that often coexist (19).

The effect of these changes is to greatly simplify diagnosis and direct clinicians' attention to a combination of three main elements, each of which must be present and each of which is assessed with two symptoms. PTSD cannot be diagnosed if the person also meets the criteria for complex PTSD, as this diagnosis is more comprehensive, yet includes all the characteristic features of PTSD.

COMPLEX PTSD

Complex PTSD is a new diagnostic category that describes a profile of symptoms that may occur after exposure to a single traumatic stressor, but more commonly occurs following severe prolonged stress or multiple or recurring unavoidable adverse events (eg, genocide exposure, sexual assault). over children, the presence of children in the war, severe domestic violence, torture or slavery).

The proposed diagnosis includes the three core features of PTSD and, in addition to them, disorders in the affective sphere, the sphere of self-image and interpersonal relationships. These additional domains reflect the presence of stress-induced disturbances that are persistent, long-lasting, and end-to-end in nature, and which, when they occur, are not necessarily directly related to trauma-related stimuli. This model replaces the overlapping ICD-10 category, "Persistent personality change after a disaster", which failed to attract scientific interest and did not include disorders arising from long-term stress in early childhood. The proposed list of specific symptoms is based on recent research (20,21) and expert opinion (22).

The proposed list of specific symptoms is based on recent research (20,21) and expert opinion (22).

Affective problems include a range of symptoms resulting from difficulty regulating emotions. They can manifest themselves in increased emotional reactivity or in the absence of emotions and in the development of dissociative states (23). Behavioral disturbances may include tantrums and reckless or self-destructive behavior (24).

Problems in the sphere of ideas about oneself include persistent negative ideas about oneself as a humiliated, defeated and worthless person. They may be accompanied by deep and pervasive feelings of shame, guilt, or failure, associated, for example, with the inability to overcome negative circumstances or the inability to prevent the suffering of others.

Impairments in social functioning manifest themselves in a variety of ways, but in general they can be described as difficulty in feeling close to others. The person may consistently avoid, ridicule, or have little interest in personal relationships and social involvement in general. In other cases, the person may have close or intense relationships from time to time but have difficulty maintaining them.

In other cases, the person may have close or intense relationships from time to time but have difficulty maintaining them.

Complex PTSD can be distinguished from borderline personality disorder (BPD) by the origin of the constellation of symptoms, the risk of self-harm, and the type of therapy needed to improve outcome. A diagnosis of BPD does not require the presence of a stressor or the core symptoms of PTSD. However, they are mandatory for the diagnosis of complex PTSD. BPD is strongly characterized by fear of abandonment, identity changes, and frequent suicidal behavior. In complex PTSD, the fear of abandonment is not a necessary component of the disorder, and self-identification is stable negative rather than changing (22).

PROLONGED GRIEF RESPONSE

Prolonged grief disorder is a new diagnosis proposed for the ICD-11 that describes an abnormally persistent and dysfunctional response to bereavement. It is defined as a pronounced and persistent pattern of symptoms of sadness and longing for the deceased, or constant immersion in thoughts about him. This reaction may be associated with difficulty accepting death, a sense of loss of a part of oneself, feelings of guilt or responsibility for death, difficulty in engaging in new social and other activities due to the loss.

This reaction may be associated with difficulty accepting death, a sense of loss of a part of oneself, feelings of guilt or responsibility for death, difficulty in engaging in new social and other activities due to the loss.

It is important to note that prolonged grief disorder can only be diagnosed if symptoms persist after a period of mourning that is normative within the person's cultural context (e.g., 6 months or more after death), persistent grief goes well beyond expected social or cultural norms, and symptoms markedly impair the patient's ability to function (see Table 1). If the typical experience of grief in a person's culture is greater than 6 months, the duration criterion for making a diagnosis should be increased accordingly.

The introduction of prolonged grief reaction is a response to a growing body of evidence for the existence of an independent and severe condition that is not adequately reflected in the available urolithiasis diagnoses. Although most people report at least partial remission of acute pain of loss by about 6 months after the loss, those who continue to experience severe grief beyond this time period often have a significant deterioration in overall functioning (25). Many studies from around the world, including both Western and Eastern cultures, have identified a small but significant proportion of bereaved people who fit this definition (26).

Many studies from around the world, including both Western and Eastern cultures, have identified a small but significant proportion of bereaved people who fit this definition (26).

Several sources of evidence at once point to the need for the introduction of prolonged grief reaction. The existence of this diagnostic unit has been confirmed in a wide range of cultures, including non-Western ones, and in people of various life periods (26). Factor analysis has repeatedly demonstrated that the central component of prolonged grief reaction (longing for the deceased) is independent of nonspecific symptoms of anxiety and depression. People with prolonged grief disorder have serious psychosocial and health problems, including other mental health problems such as suicidal behavior, substance abuse, self-destructive behavior, or physical disorders such as high blood pressure and an increased incidence of cardiovascular disease (27) . Finally, there are specific brain dysfunctions and cognitive patterns associated with prolonged grief reaction (26,28).

In terms of treatment, long-term grief does not respond to antidepressant treatment, while bereavement depressive syndromes do (29). It is important to note that psychological therapies that strategically target the symptoms of prolonged grief disorder are more effective than treatments for depression (30)

The introduction of the diagnosis of prolonged grief disorder has been controversial due to concerns that it may pathologize the normal grief response (31). The Working Group considered this issue carefully and highlighted several points. First, the diagnostic criteria were developed with great care in relation to the variability of "normal" processes and attention to cultural and contextual factors. Second, the diagnosis only applies to a minority (<10%) of bereaved people who have persistent impairment. Third, it has been recognized that there is significant cultural variability in the manifestations of grief that must be taken into account in diagnostic decisions. Fourth, many people may experience fluctuating and distressing experiences in response to grief after and more than six months after the death of a loved one, but they are not necessarily candidates for a diagnosis of prolonged grief because of lack of persistence and exhaustion.

Epidemiological studies show that prolonged grief disorder is a public health problem. Accurately identifying people with this disorder can reduce the likelihood of mistreatment. The advent of evidence-based interventions that address the symptoms of prolonged grief disorder may ease the burden of disease and increase the validity of this diagnosis.

ADAPTATION DISORDER

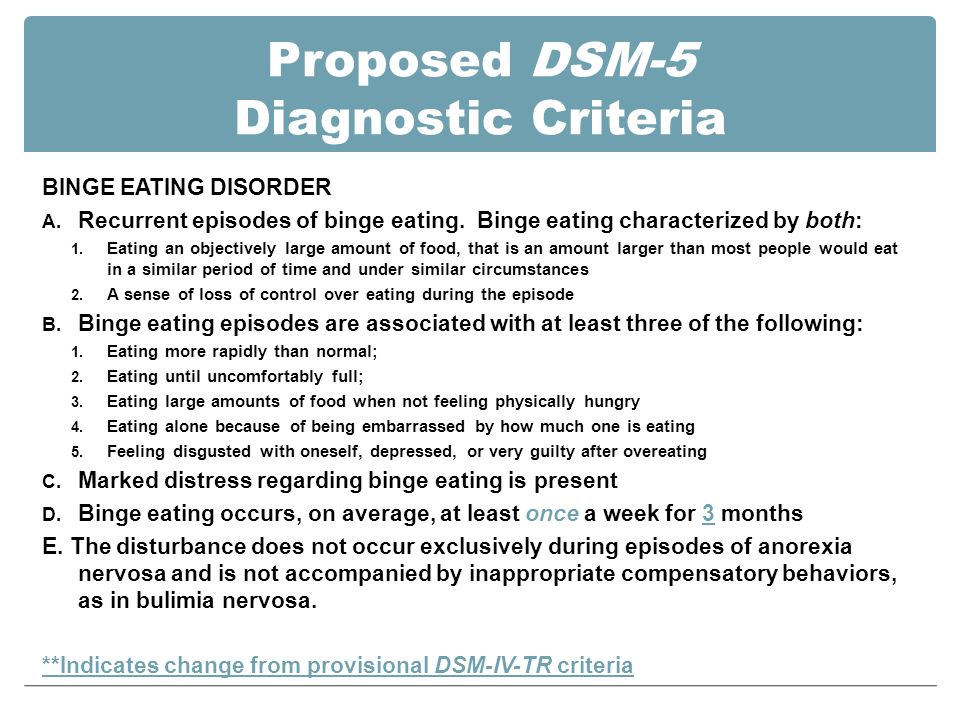

Adjustment disorder has been a poorly defined area of psychopathology in which clinical manifestations can be a variety of symptoms with a relative absence of delimiting features. This category is usually thought of as consisting of a group of subthreshold disorders associated with a triggering event or situation. Often the identification of such an inciting event is done after the fact. Adjustment disorder is primarily used as a residual category for patients who do not meet diagnostic criteria for depressive or anxiety disorders, or as a provisional diagnosis when it is not clear whether or not the patient will develop post-traumatic or mood disorder (eg, 7,8).

The proposal for the ICD-11 focuses on the fact that adjustment disorder is a response of maladjustment to an identifiable psychosocial stressor or lifestyle change. It is characterized by a preoccupation with stress and an inability to adapt, manifested by a range of symptoms that interfere with daily functioning, such as difficulty concentrating or disturbed sleep. Symptoms of anxiety or depression, impulse control problems are also often present. Symptoms appear within a month of the onset of the stressor(s) and tend to resolve within about 6 months unless the stressor persists for longer. The disorder causes significant suffering and impairment of social or occupational functioning (32).

Adjustment disorder is seen as a single continuum with normal adjustment responses, but differs from "normal" in intensity and resulting disturbances. Unlike PTSD, here the severity of the stressor is not considered in the diagnosis. However, adjustment disorders may be the result of extreme stress, when the symptoms do not meet all the criteria for PTSD.

There is no evidence for the validity or clinical utility of the adjustment disorder subtypes described in ICD-10 and have therefore been removed from ICD-11. Such subtypes can be misleading by focusing on the dominant content of distress, obscuring the underlying commonality of these disorders. Subtypes are not relevant to treatment choice and are not associated with a specific prognosis (7). The characteristic feature is often a mixture of emotional and behavioral symptoms (8). Although symptoms of either internalization or externalization may predominate, they often coexist.

ACUTE STRESS RESPONSE AS A CONDITION THAT IS NOT A MENTAL DISORDER

The ICD-10 definition of acute stress response is ambiguous. The name "reaction" and its diagnostic description suggest transience, but the location in the ICD-10 in the section of mental and behavioral disorders refers it to pathology. The confusion is exacerbated by the parallel existence of the diagnosis of "acute stress disorder" in the DSM-IV and DSM-5.

Acute stress disorder is similar in many ways to PTSD and has sometimes been considered a precursor to PTSD, but it differs from PTSD in that it has more dissociative symptoms. In DSM-5, acute stress disorder can only be diagnosed in the first month after injury, and PTSD can only be diagnosed after one month. A review of the available literature on acute stress disorder has questioned whether it is a qualitative predictor of the development of PTSD (33). An important reason for including acute stress disorder in the DSM-5 may be sensitivity to the US medical reimbursement issue, which states that treatment should not be provided for non-disorder events, even after a severe traumatic experience, when basic psychological interventions may indeed be necessary. However, WHO's position was that health financing, reimbursement, and definitions of disease were separate issues, and combining them would not help the goal of reducing the overall burden of disease (34). Thus, the argument regarding the reimbursement of the cost of services was not considered sufficient reason to designate a normal reaction as a mental disorder.

In addition, the ICD-10 and draft ICD-11 do not have a strict minimum age limit for PTSD, so this diagnosis can be used within the first month after injury, provided the symptoms are sufficiently persistent to result in impaired functioning. Therefore, there is no need for a DSM-5 diagnosis of acute stress in ICD-11, also taking into account the request of clinicians to reduce the total number of diagnoses in diagnostic systems (1,2).