Ptsd and mindfulness

The Science of How Mindfulness Relieves Post Traumatic Stress

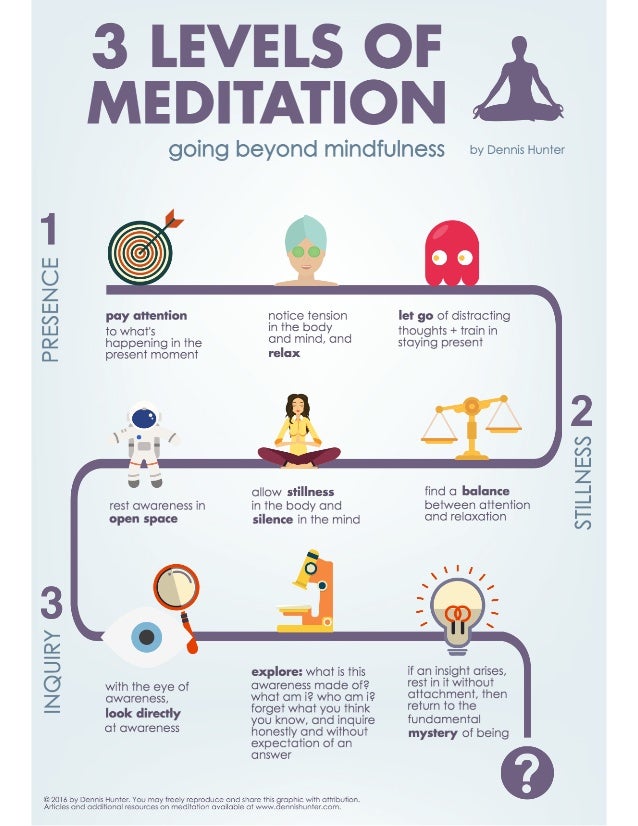

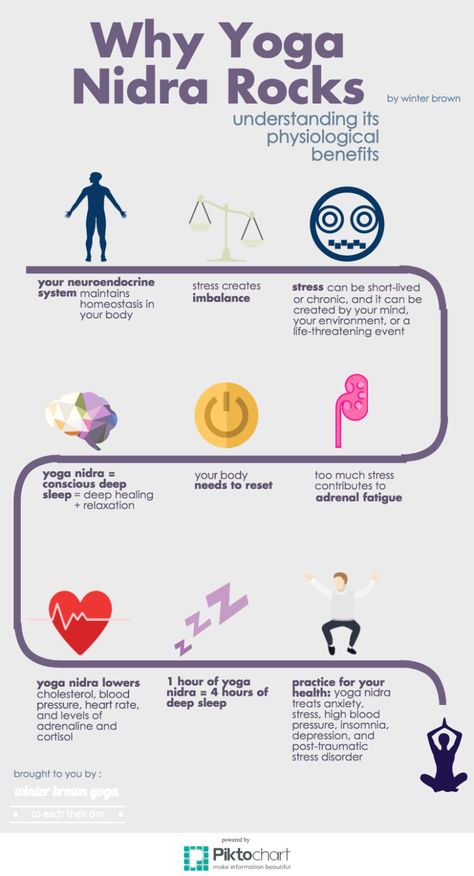

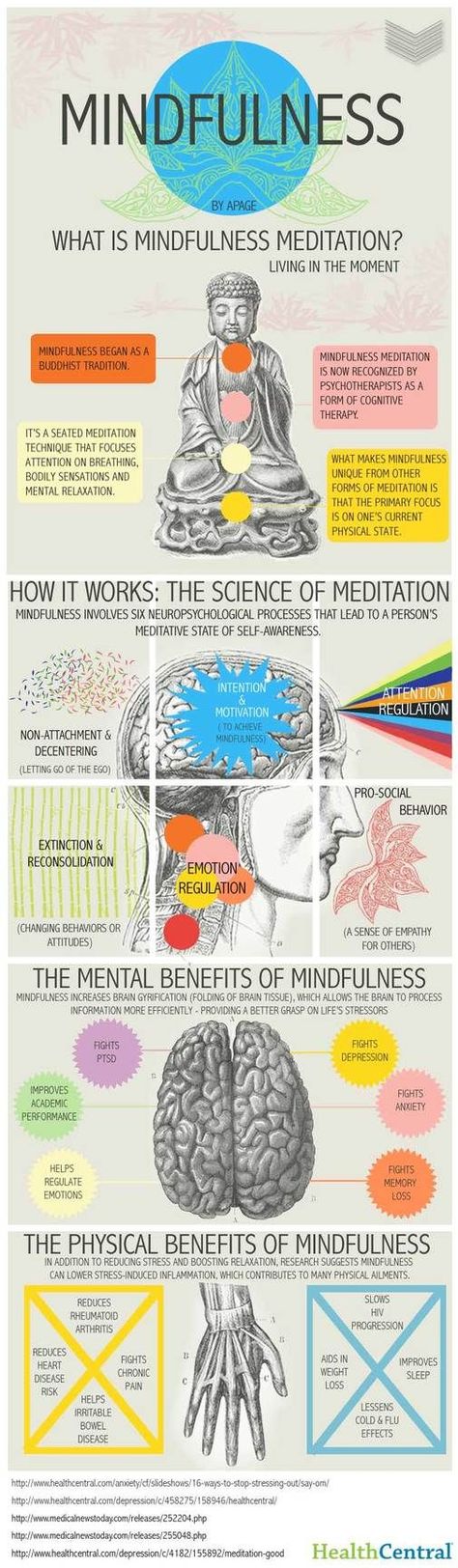

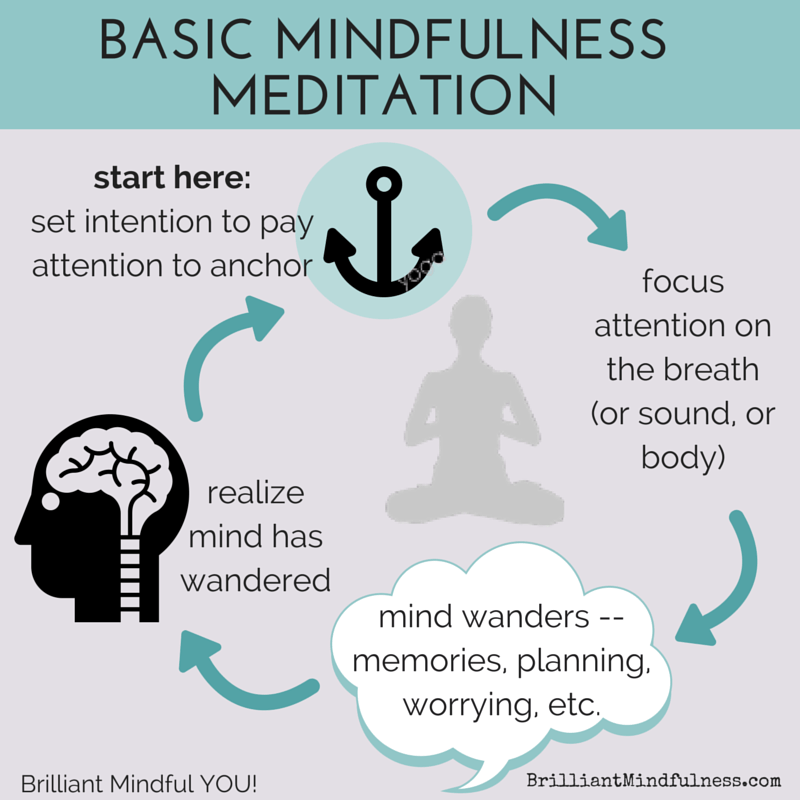

Pain, loss and traumatic events are part of the human experience, yet most of us don’t talk about that part of our lives. According to a Health Care Policy report from Harvard Medical School, approximately 60% of North Americans experience at least one traumatic event in their lifetime. Some of these individuals may go on to develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a condition marked by intense, disturbing thoughts and feelings related to a traumatic experience that last long after the traumatic event has ended. A recent review of the research finds that mindfulness-based programs such as Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction (MBSR) may provide relief from post-traumatic symptoms such as anxiety, sleep disturbance, and difficulty concentrating.

Understanding Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Post-traumatic stress and PTSD may occur after experiencing or witnessing a shocking or dangerous event. During the event, fear triggers a cascade of hormones like cortisol and adrenaline that flood the nervous system and mobilize the body’s defenses. Once the threat subsides, the nervous system usually “resets,” initiating the healing and recovery process.

In some cases, or when stress is chronic, the system does not reset, and the physical and psychological effects of acute or prolonged stress manifest as symptoms of traumatic stress. Not everyone who survives a trauma develops PTSD, and not everyone with PTSD has experienced or observed a life-threatening event. Sudden, unexpected death or loss, or persistent environmental threat can also lead to a person developing post-traumatic stress symptoms.

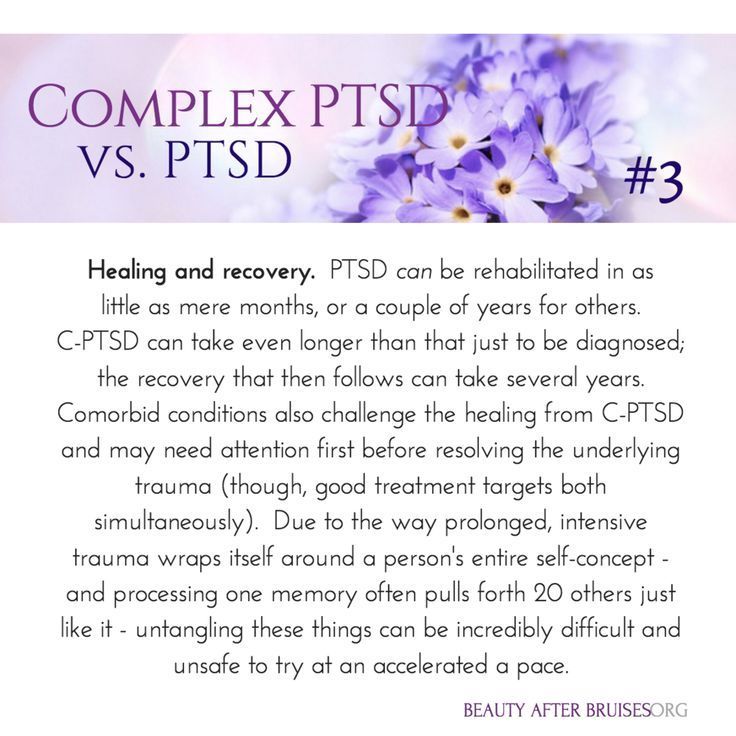

It is important to note that post-traumatic stress symptoms are not, in and of themselves, pathological. They represent the mind and body’s natural process of recovery following severe, often painful life experiences. Often more chronic and extremely traumatic events require longer periods of healing and repair.

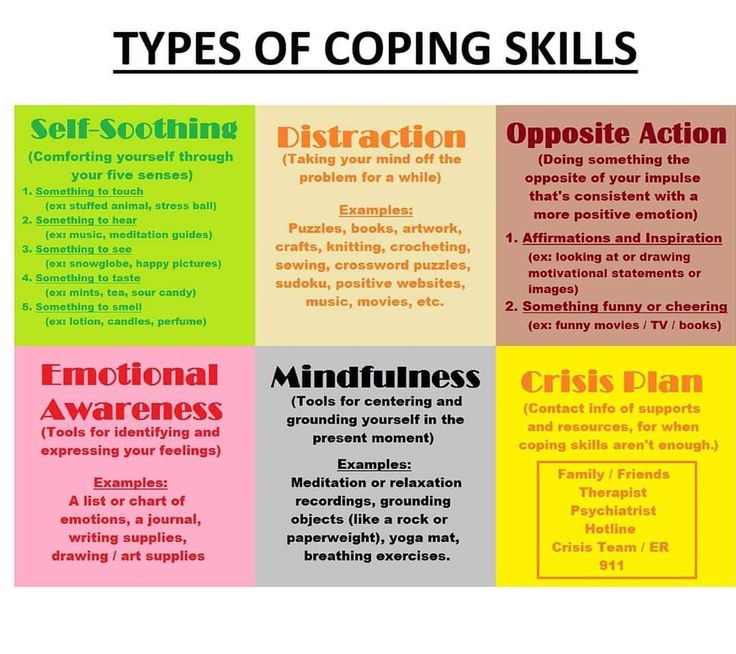

As resilience builds, symptoms often lessen and eventually subside altogether. For some, however, post-traumatic symptoms can be accompanied by significant depression, anxiety, panic, and thoughts of suicide. In these cases, evidence-based treatment approaches under the care of a medical professional may be necessary to help alleviate the impacts of trauma.

The Symptoms of PTSD

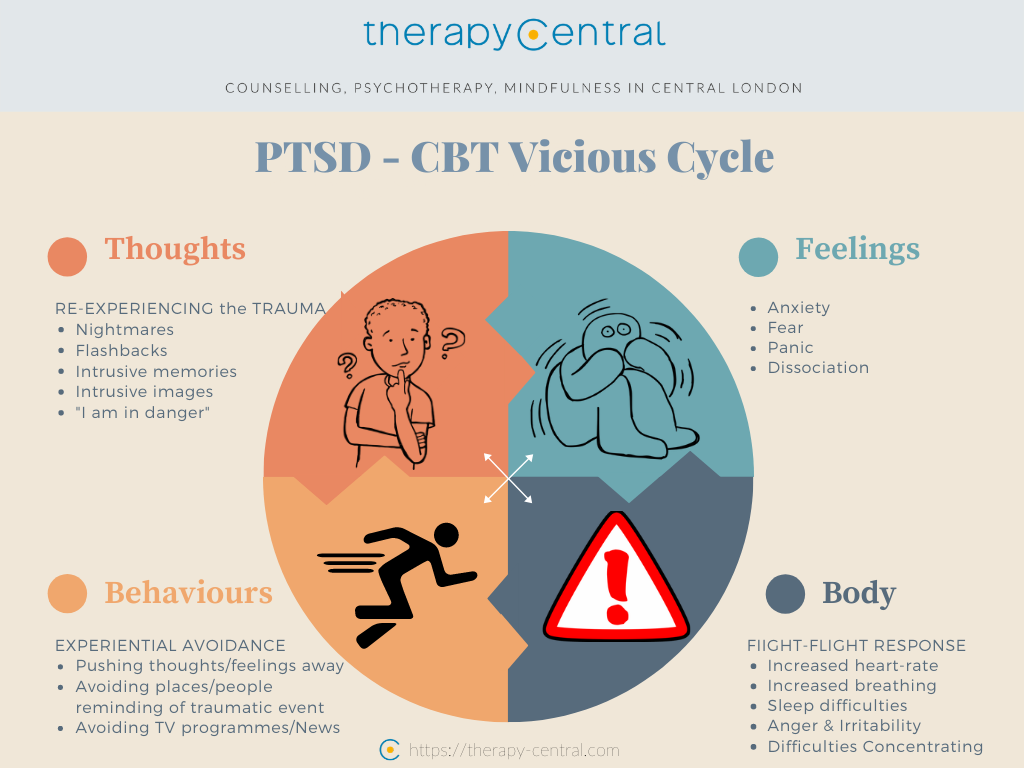

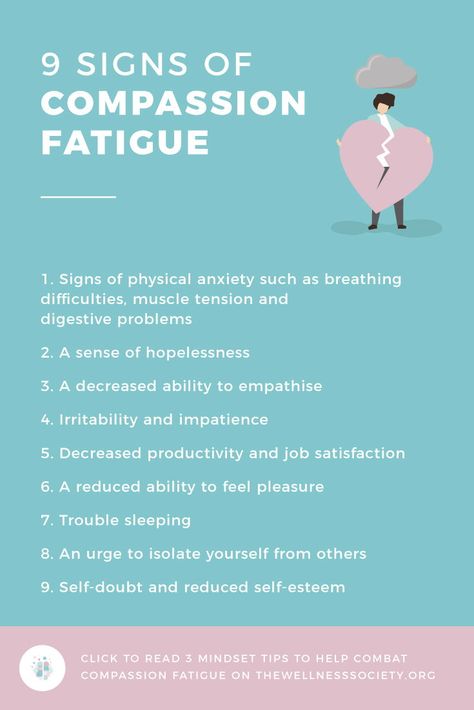

Although there are many causes of trauma, people with PTSD have a great deal in common. According to non-profit Anxiety and Depression Association of America, PTSD is characterized by three primary symptoms:

- Repeating or reimagining the experience — Most have intrusive memories or bad dreams that occur in combination with physical symptoms like a racing heart and shortness of breath.

- Avoidance— Individuals also tend to avoid objects, places, or events that trigger recollection of the initial experience, and learn to numb physical and emotional sensations when under duress.

- Hyperactivity — The combination of unresolved nervous system hyperactivity and emotional distress can result in tension, anger, irritability, a tendency to startle easily, or difficulties coping with life events. This is often accompanied by difficulties sleeping, eating, and concentrating, and a tendency toward sadness, depression, social isolation, guilt, and a lack of trust in others and the world.

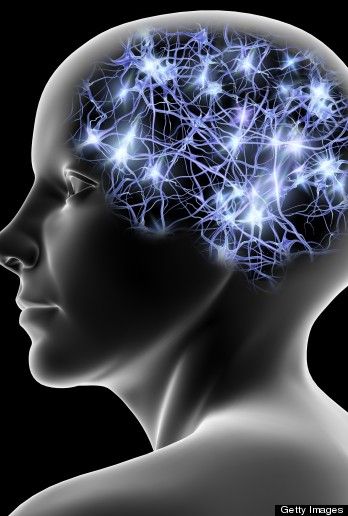

How Traumatic Stress Affects the Brain

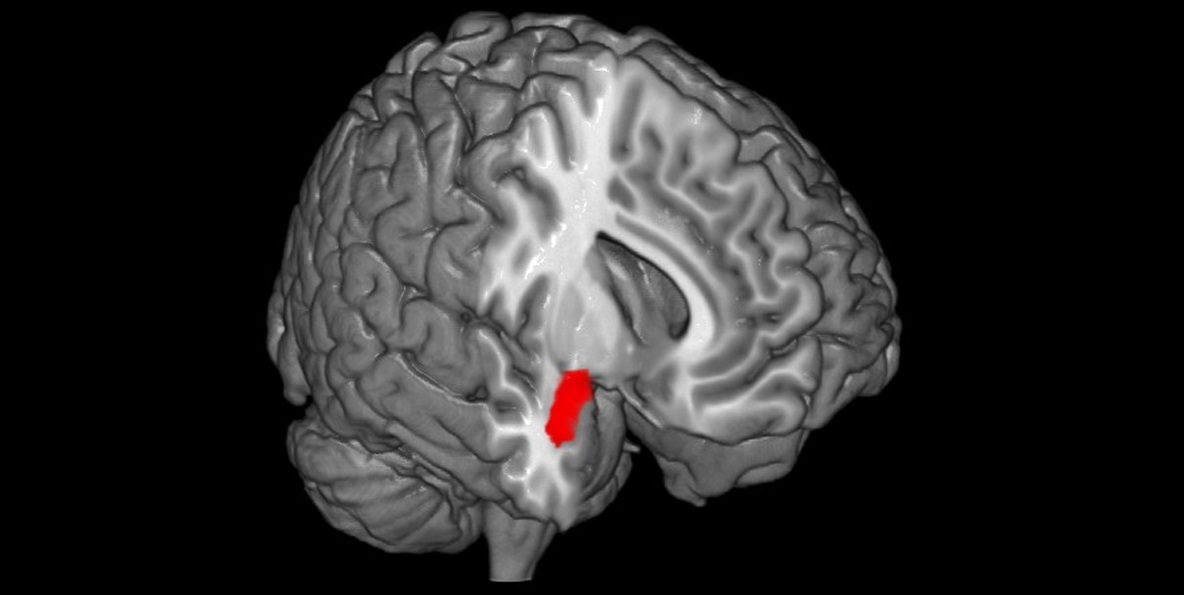

Acute and persistent traumas are also known to impact the structure and function of the brain and nervous system. Human and animal studies find that traumatic stress is associated with decreased volume in the hippocampus, anterior cingulate cortex, and left amygdala; brain regions that are highly sensitive to environmental threat.

The hippocampus, part of the brain’s emotion processing center (limbic system), plays an important role in learning, memory, and emotion processing. It is particularly vulnerable to stress, and tends to be smaller in volume in those with PTSD.

The anterior cingulate links the limbic system to the prefrontal cortex—often referred to as the brain’s “thinking center.” It plays an important role in emotional regulation and cognitive flexibility.

All told, these brain signaling anomalies may be related to greater difficulty regulating and coping with negative thoughts, feelings, and memories — a hallmark of post-traumatic stress.

The amygdala, another hub for cognitive and emotional processing, has also been found to be smaller in those with a history of trauma, although there doesn’t appear to be a connection between the size of the amygdala and the severity of PTSD symptoms. Researchers do believe that decreased regulation of the amygdala may be associated with an increased risk of developing post-traumatic symptoms or a diagnosis of PTSD.

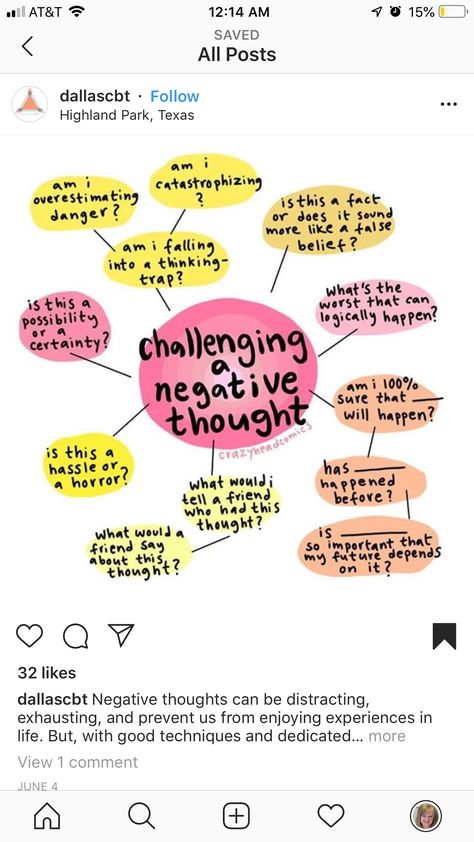

All told, these brain signaling anomalies may be related to greater difficulty regulating and coping with negative thoughts, feelings, and memories — a hallmark of post-traumatic stress.

But traumatic stress is not inevitable. For some, social support such as friends, family, or a support group, and a nervous system that is able to reset after a highly stressful event can reduce the odds of developing PTSD. For those with repeated exposure to extreme stressors, a history of adverse childhood events, a lack of social support, a history of psychological problems, or prolonged or chronic environmental threat, treatment is often a viable option to move from trauma to wellbeing.

The Impact of Mindfulness-Based Treatment on PTSD

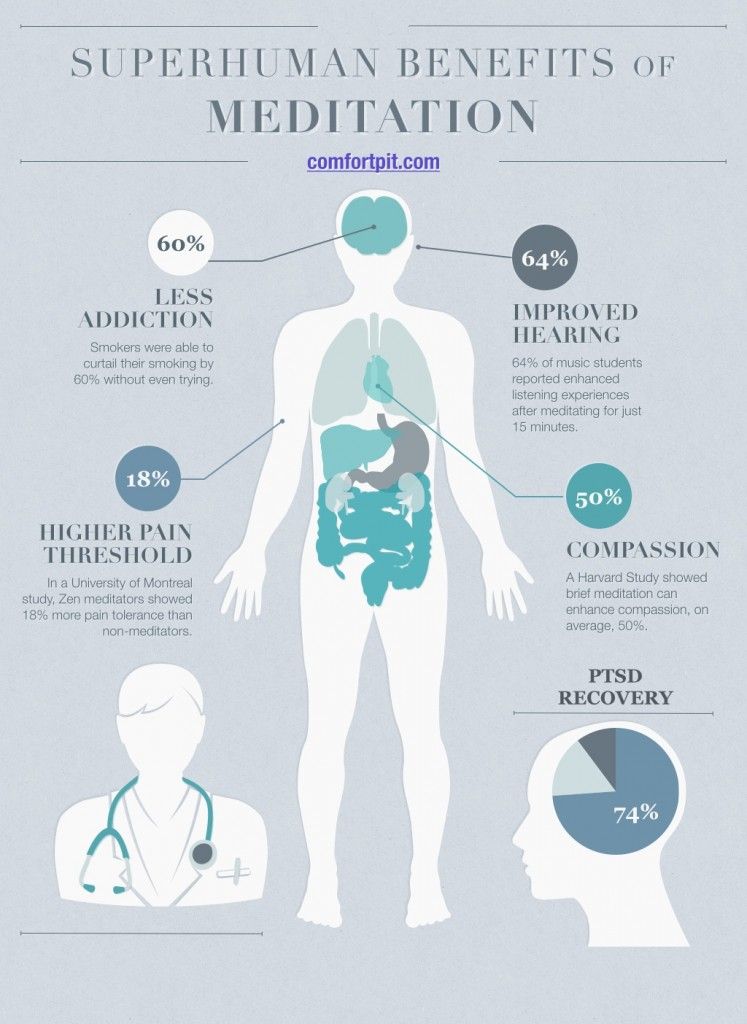

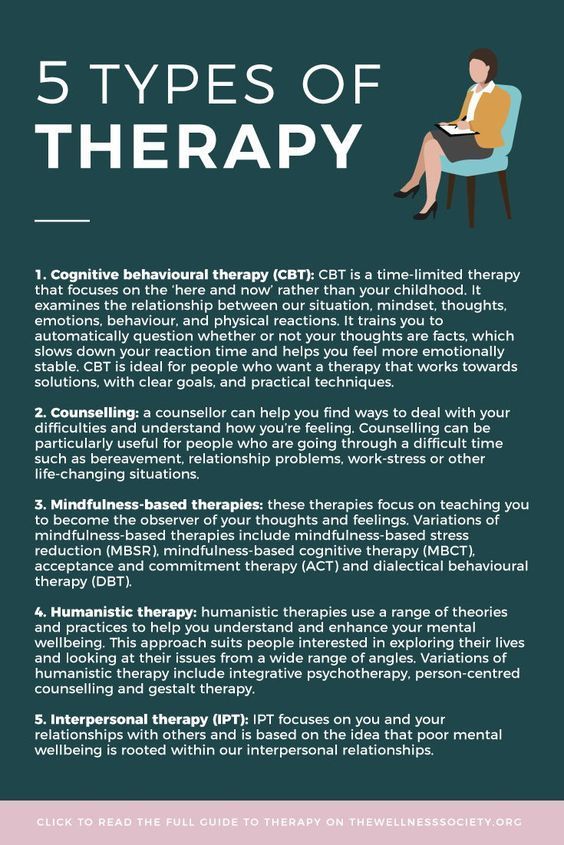

Historically, cognitive forms of psychotherapy with or without medication were the first line of treatment for PTSD. But many with PTSD avoid therapy due to social stigma, cost, guilt, shame, or an inability to seek help. In response to the need for alternative forms of treatment, more providers and trauma sufferers are turning to mindfulness-based interventions.

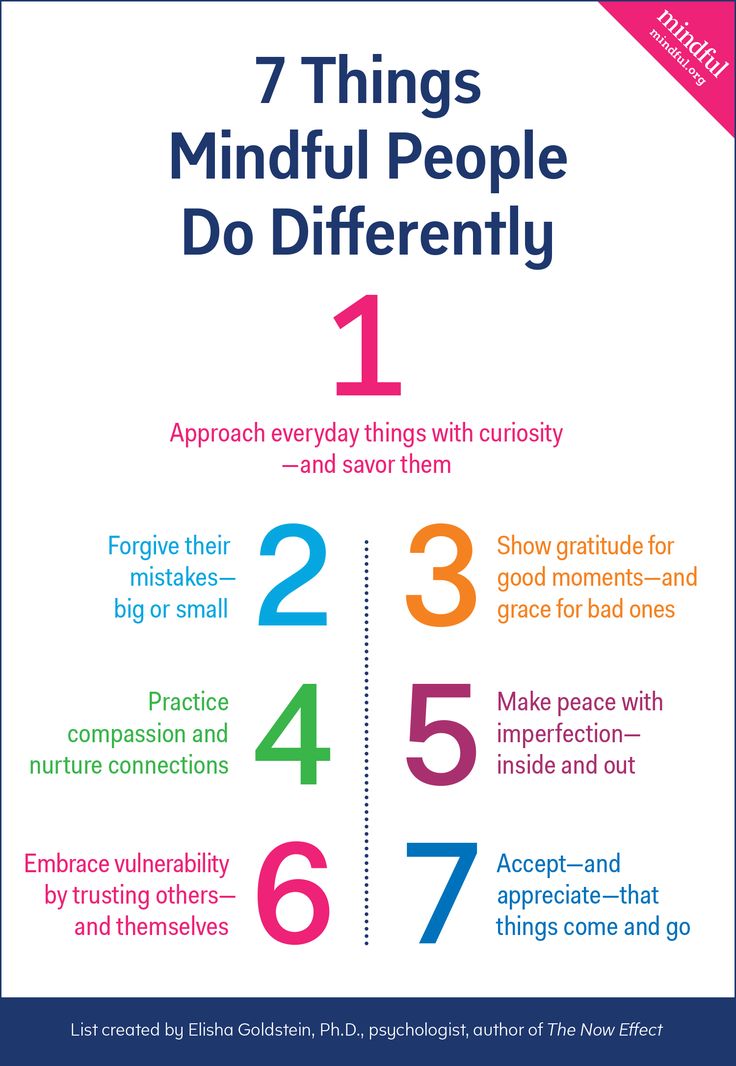

There is some debate among professionals as to whether mindfulness-based interventions for PTSD are effective. Some suggest that an increase in mindfulness may help individuals to better cope with intrusive thoughts and memories, and be more equipped to handle emotional distress. Correlational studies, which examine the relationship between two or more factors, show that higher levels of dispositional mindfulness are associated with fewer concurrent PTSD symptoms in survivors of natural disasters, victims of sexual abuse or assault, and firefighters.

Some suggest that an increase in mindfulness may help individuals to better cope with intrusive thoughts and memories, and be more equipped to handle emotional distress. Correlational studies, which examine the relationship between two or more factors, show that higher levels of dispositional mindfulness are associated with fewer concurrent PTSD symptoms in survivors of natural disasters, victims of sexual abuse or assault, and firefighters.

Others suggest that mindfulness-based practices like meditation may cause considerable distress for some practitioners. For example, in a study of 60, adult meditators (43% female) and 32 meditation experts (25% female), 88% of participants reported “challenging or difficult meditation experiences [that] bled over into daily life…” that ranged from a few days to more than 10 years.

We have yet to understand what types of practices may, or may not exacerbate symptoms in those with a history of traumatic exposure. In addition, there are a number of well-researched conventional approaches such as cognitive therapy, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), and medications shown to reduce PTSD symptoms. There is some skepticism as to whether mindfulness alternatives are appropriate first-line therapies for PTSD.

There is some skepticism as to whether mindfulness alternatives are appropriate first-line therapies for PTSD.

Do Mindfulness-Based Therapies Reduce Trauma Symptoms?

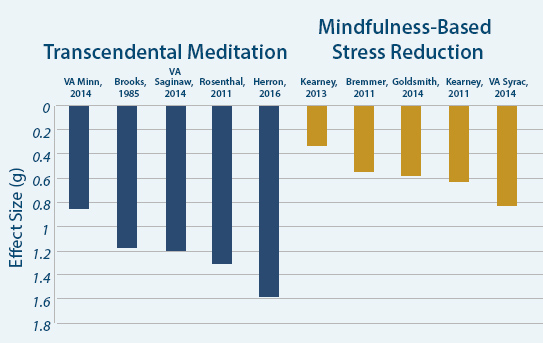

A meta-analysis of 18 studies compared the effects of mindfulness-based interventions to those of a randomized control group in reducing the psychological symptoms of traumatic stress and PTSD. This study included data on 1,219 participants. Researchers found that individuals who participated in the mindfulness-based interventions demonstrated significantly lower levels of PTSD symptoms following treatment than various control group members.

They also found that the longer the mindfulness intervention, the greater the reduction in traumatic stress symptoms. Additionally, individuals who received mindfulness-based interventions reported higher levels of mindfulness at the end of treatment compared to control group members.

Researchers found that individuals who participated in the mindfulness-based interventions demonstrated significantly lower levels of PTSD symptoms following treatment than various control group members.

The review also uncovered some important caveats. Among them was the discovery that increased mindfulness following an intervention was not linked to fewer PTSD symptoms after treatment. Although this finding may have been the result of methodological problems in the research, it appears that becoming more mindful does not necessarily translate to experiencing less traumatic stress.

The severity of PTSD symptoms at the onset of an intervention was also not related to changes in mindfulness or a reduction of symptoms following treatment. Those with and without a PTSD diagnosis responded similarly to mindfulness-based therapies.

Finally, although researchers anticipated that trauma-specific mindfulness-based interventions would outperform traditional programs like mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), results from these programs have been found to be comparable, suggesting that mindfulness training on its own may be impactful.

Although these findings are encouraging, the review’s authors note of a potential source of bias known as the file drawer problem: the possible over-inflation of positive results that may occur when only studies with positive or significant statistical effects are published. It is important to not overlook the possibility that studies with negative outcomes are underreported or tossed out altogether.

It is important to not overlook the possibility that studies with negative outcomes are underreported or tossed out altogether.

Indeed, in recent years, contemplative scientists have called into question whether the negative or harmful effects of meditation have been suppressed in the research literature. This is of particular importance when considering the use of mindfulness-based therapies with those with a trauma history, for whom meditation and contemplation may exacerbate an already unstable nervous system. This thorny dilemma will require additional, high-quality studies to be resolved.

How Mindfulness-Based Therapies May Change Brain Structure

Brain imaging studies provide another promising research avenue that may inform our understanding of how mindfulness-based therapies aid in trauma recovery. In one study, 23 male Iraq and Afghanistan combat veterans were randomly assigned to either a Mindfulness-Based Exposure Therapy (MBET) group, which combines mindfulness with traditional exposure therapy, or a present-centered group therapy (PCGT), which encourages acceptance of thoughts and emotions as they occur in the present moment.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) brain scans performed before and after treatment showed that those receiving MBET had significantly more connections between the default mode network (DMN), which is associated with mind wandering and rumination, and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC).

This implies that mindfulness training may enable those experiencing post-traumatic stress to be better able to inhibit or reduce the pernicious cycle of negative thoughts, feelings, and memories that accompany traumatic stress. MBET group participants also had fewer symptoms of post-traumatic stress, however, their symptom reduction was not significantly different from those in the PCGT group.

Findings from this study of veterans with PTSD parallel those conducted with adults without PTSD in which meditation has been found to benefit physical and mental health and change the structure and function of the DMN, amygdala, and hippocampus, affecting our impulses and decision-making.

Although many questions remain unanswered, including whether or not these brain changes translate to greater health, happiness, and well-being, they suggest that mindfulness may be beneficial for healing from adversity.

Mindfulness-based treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of the treatment literature and neurobiological evidence

1. Kessler RC. Posttraumatic stress disorder: the burden to the individual and to society. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the national comorbidity survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Van Ameringen M, Mancini C, Patterson B, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder in Canada. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2008;14:171–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th Ed. Washington (DC): APA; 2013. [Google Scholar]

[Google Scholar]

5. Armour C, Karstoft KI, Richardson JD. The co-occurrence of PTSD and dissociation: differentiating severe PTSD from dissociative-PTSD. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49:1297–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Bennett DC, Modrowski CA, Kerig PK, et al. Investigating the dissociative subtype of posttraumatic stress disorder in a sample of traumatized detained touth. Psychol Trauma. 2015;7:465–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Lanius RA, Brand B, Vermetten E, et al. The dissociative subtype of posttraumatic stress disorder: rationale, clinical and neurobiological evidence, and implications. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:701–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Spiegel D, Lewis-Fernández R, Lanius R, et al. Dissociative disorders in DSM-5. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9:299–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Wolf EJ, Miller MW, Reardon AF, et al. A latent class analysis of dissociation and posttraumatic stress disorder: evidence for a dissociative subtype. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:698–705. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:698–705. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Wolf EJ, Lunney CA, Miller MW, et al. The dissociative subtype of PTSD: a replication and extension. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:679–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Cahill SP, Rothbaum BO, Resick PA, et al. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for adults. In: Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, et al., editors. Effective treatments for PTSD: practice guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. 2nd ed. New York (NY) and London (UK): The Guilford Press; 2012. pp. 139–222. [Google Scholar]

12. Steenkamp MM, Litz BT, Hoge CW, et al. Psychotherapy for military-related PTSD. JAMA. 2015;314:489–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Bradley R, Greene J, Russ E, et al. A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy for PTSD. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:214–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Schottenbauer MA, Glass CR, Arnkoff DB, et al. Nonresponse and dropout rates in outcome studies on PTSD: review and methodological considerations. Psychiatry. 2008;71:134–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Psychiatry. 2008;71:134–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Goetter EM, Bui E, Ojserkis RA, et al. A systematic review of dropout from psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder among Iraq and Afghanistan combat veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:401–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Kehle-Forbes SM, Meis LA, Spoont M, et al. Treatment initiation and dropout from prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy in a VA outpatient clinic. Psychol Trauma. 2015;8:107–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Zayfert C, DeViva JC, Becker CB, et al. Exposure utilization and completion of cognitive behavioral therapy for PTSD in a “real world” clinical practice. J Trauma Stress. 2005;18:637–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Bae H, Kim D, Park CP. Dissociation predicts treatment response in eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) for posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Dissociation. 2016;17:112–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Price M, Kearns M, Houry D, et al. Emergency department predictors of posttraumatic stress reduction for trauma-exposed individuals with and without an early intervention. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82:336–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Emergency department predictors of posttraumatic stress reduction for trauma-exposed individuals with and without an early intervention. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82:336–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Wolf EJ, Lunney CA, Schnurr PP. The influence of the dissociative subtype of posttraumatic stress disorder on treatment efficacy in female veterans and active duty service members. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016;84:95–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Cloitre M, Petkova E, Wang J, et al. An examination of the influence of a sequential treatment on the course and impact of dissociation among women with PTSD related to childhood abuse. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:709–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Resick PA, Suvak MK, Johnides BD, et al. The impact of dissociation on PTSD treatment with cognitive processing therapy. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:718–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Stein DJ, Koenen KC, Friedman MJ, et al. Dissociation in posttraumatic stress disorder: evidence from the world mental health surveys. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:302–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:302–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Frost KD, Laska KM, Wampold BE. The evidence for present-centered therapy as a treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2014;27:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2003;10:144–56. [Google Scholar]

26. Banks K, Newman E, Saleem J. An overview of the research on mindfulness-based interventions for treating symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. J Clin Psychol. 2015;71:935–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Lang AJ, Strauss JL, Bomyea J, et al. The theoretical and empirical basis for meditation as an intervention for PTSD. Behav Modif. 2012;36:759–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Follette V, Palm KM, Pearson AN. Mindfulness and trauma: implications for treatment. J Ration-Emot Cogn-Behav Ther. 2006;24:45–61. [Google Scholar]

29. Baer RA. Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: a conceptual and empirical review. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2003;10:125–43. [Google Scholar]

Baer RA. Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: a conceptual and empirical review. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2003;10:125–43. [Google Scholar]

30. Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living: using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York (NY): Bantam Dell; 1990. [Google Scholar]

31. Kabat-Zinn J, Massion A, Kristeller J, et al. Effectiveness of a meditation-based stress reduction program in the treatment of anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:936–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Teasdale JD, Segal SV, Williams JMG, et al. Prevention of relpase/recurrence in major depression by mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:615–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Chiesa A, Serretti A. Mindfulness based cognitive therapy for psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2011;187:441–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Fjorback LO, Arendt M, Ornbol E, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;124:102–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;124:102–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. King AP, Block SR, Sripada RK, et al. Altered default mode network (DMN) resting state functional connectivity following a mindfulness-based exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in combat veterans of Afghanistan and Iraq. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33:289–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. King AP, Block SR, Sripada RK, et al. A pilot study of mindfulness-based exposure therapy in OEF/OIF combat veterans with PTSD: altered medial frontal cortex and amygdala responses in social–emotional processing. Front Psychiatry. 2016;7:154. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Frewen P, Rogers N, Flodrowski L, et al. Mindfulness and metta-based trauma therapy (MMTT): initial development and proof-of-concept of an internet resource. Mindfulness. 2015;6:1322–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Thompson RW, Arnkoff DB, Glass CR. Conceptualizing mindfulness and acceptance as components of psychological resilience to trauma. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2011;12:220–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Trauma Violence Abuse. 2011;12:220–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Hinton DE, Ojserkis RA, Jalal B, et al. Loving-kindness in the treatment of traumatized refugees and minority groups: a typology of mindfulness and the nodal network model of affect and affect regulation. J Clin Psychol. 2013;69:817–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Hofmann SG, Grossman P, Hinton DE. Loving-kindness and compassion meditation: potential for psychological interventions. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:1126–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Herman JL. Posttraumatic stress disorder as a shame disorder. In: Dearing RL, Tangney JP, editors. Shame in the therapy hour. Washington (DC): American Psychological Association; 2011. [Google Scholar]

42. Lee DA, Scragg P, Turner S. The role of shame and guilt in traumatic events: a clinical model of shame-based and guilt-based PTSD. Br J Med Psychol. 2001;74:451–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Frewen PA, Dean JA, Lanius RA. Assessment of anhedonia in psychological trauma: development of the Hedonic Deficit and Interference Scale. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2012;3:8585. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Assessment of anhedonia in psychological trauma: development of the Hedonic Deficit and Interference Scale. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2012;3:8585. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Frewen PA, Dozois DJA, Lanius RA. Assessment of anhedonia in psychological trauma: psychometric and neuroimaging perspectives. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2012;3:8587. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Etter DW, Gauthier JR, McDade-Montez E, et al. Positive affect, childhood adversity, and psychopathology in psychiatric inpatients. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2013;4:20771. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Boughner E, Thornley E, Kharlas D, et al. Mindfulness-related traits partially mediate the association between lifetime and childhood trauma exposure and PTSD and dissociative symptoms in a community sample assessed online. Mindfulness. 2016;7:672–9. [Google Scholar]

47. Chopko BA, Schwartz RC. The relation between mindfulness and posttraumatic growth: a study of first responders to trauma-inducing incidents. J Ment Health Couns. 2009;31:363–76. [Google Scholar]

J Ment Health Couns. 2009;31:363–76. [Google Scholar]

48. Dahm KA, Meyer EC, Neff KD, et al. Mindfulness, self-comparssion, posttraumatic stress disorder, and functional disability in U.S. Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:460–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Glück TM, Tran US, Raninger S, et al. The influence of sense of coherence and mindfulness on PTSD symptoms and posttraumatic cognitions in a sample of elderly Austrian survivors of World War II. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016;28:435–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Nitzan-Assayag Y, Aderka IM, Bernstein A. Dispositional mindfulness in trauma recovery: prospective relations and mediating mechanisms. J Anxiety Disord. 2015;36:25–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Smith BW, Ortiz JA, Steffen LE, et al. Mindfulness is associated with fewer PTSD symptoms, depressive symptoms, physical symptoms, and alcohol problems in urban firefighters. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79:613–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Thompson BL, Waltz J. Mindfulness and experiential avoidance as predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder avoidance symptom severity. J Anxiety Disord. 2010;24:409–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Zerubavel N, Messman-Moore TL. Staying present: incorporating mindfulness into therapy for dissociation. Mindfulness. 2015;6:303–14. [Google Scholar]

54. Corrigan FM. Mindfulness, dissociation, EMDR and the anterior cingulate cortex: a hypothesis. Contemp Hypn. 2002;19:8–17. [Google Scholar]

55. Michal M, Beutel ME, Jordan J, et al. Depersonalization, mindfulness, and childhood trauma. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195:693–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, et al. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 2006;13:27–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Walach H, Buchheld N, Buttenmüller V, et al. Measuring mindfulness — the Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI) Pers Individ Dif. 2006;40:1543–55. [Google Scholar]

2006;40:1543–55. [Google Scholar]

58. Frewen P, Lanius R. Healing the traumatized self: consciousness, neuroscience, treatment. New York (NY) and London (UK): WW Norton & Company; 2015. [Google Scholar]

59. Follette VM, Briere J, Rozelle D, et al., editors. Mindfulness-oriented interventions for trauma: integrating contemplative practices. New York (NY): The Guildford Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

60. Rauch SL, Shin LM, Phelps EA. Neurocircuitry models of posttraumatic stress disorder and extinction: human neuroimaging research — past, present, and future. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:376–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Patel R, Spreng RN, Shin LM, et al. Neurocircuitry models of posttraumatic stress disorder and beyond: a meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:2130–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Hayes JP, Hayes SM, Mikedis AM. Quantitative meta-analysis of neural activity in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Mood Anxiety Disord. 2012;2:9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2012;2:9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Lanius RA, Vermetten E, Loewenstein RJ, et al. Emotion modulation in PTSD: clinical and neurobiological evidence for a dissociative subtype. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:640–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Felmingham K, Kemp AH, Williams L, et al. Dissociative responses to conscious and non-conscious fear impact underlying brain function in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Med. 2008;38:1771–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Hopper JW, Frewen PA, van der Kolk BA, et al. Neural correlates of reexperiencing, avoidance, and dissociation in PTSD: symptom dimensions and emotion dysregulation in responses to script-driven trauma imagery. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20:713–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Lanius RA, Vermetten E, Loewenstein RJ, et al. Emotion modulation in PTSD: clinical and neurobiological evidence for a dissociative subtype. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:640–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Lutz J, Herwig U, Opialla S, et al. Mindfulness and emotion regulation — an fMRI study. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2013;9:776–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lutz J, Herwig U, Opialla S, et al. Mindfulness and emotion regulation — an fMRI study. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2013;9:776–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Ives-Deliperi VL, Howells F, Stein DJ, et al. The effects of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in patients with bipolar disorder: a controlled functional MRI investigation. J Affect Disord. 2013;150:1152–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Desbordes G, Negi LT, Pace TWW, et al. Effects of mindful-attention and compassion meditation training on amygdala response to emotional stimuli in an ordinary, non-meditative state. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012;6:1–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70. Taylor VA, Grant J, Daneault V, et al. Impact of mindfulness on the neural responses to emotional pictures in experienced and beginner meditators. Neuroimage. 2011;57:1524–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Hölzel BK, Hoge EA, Greve DN, et al. Neural mechanisms of symptom improvements in generalized anxiety disorder following mindfulness training. NeuroImage Clin. 2013;2:448–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

NeuroImage Clin. 2013;2:448–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Tang YY, Hölzel BK, Posner MI. The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

73. Hölzel BK, Ott U, Gard T, et al. Investigation of mindfulness meditation practitioners with voxel-based morphometry. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2008;3:55–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

74. Santarnecchi E, D’Arista S, Egiziano E, et al. Interaction between neuroanatomical and psychological changes after mindfulness-based training. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e108359. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

75. Lanius RA, Frewen PA, Tursich M, et al. Restoring large-scale brain networks in PTSD and related disorders: a proposal for neuroscientifically-informed treatment interventions. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2015;6:27313. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

76. Krystal H. Integration and self-healing: affect, trauma, alexithymia. New York (NY): Routledge; 1988. [Google Scholar]

New York (NY): Routledge; 1988. [Google Scholar]

77. Frewen PA, Lanius RA, Dozois DJA, et al. Clinical and neural correlates of alexithymia in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 2008;117:171–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

78. Marchand WR. Neural mechanisms of mindfulness and meditation: evidence from neuroimaging studies. World J Radiol. 2014;6:471–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

79. Menon V. Large-scale brain networks and psychopathology: a unifying triple network model. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15:483–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

80. Greicius MD, Krasnow B, Reiss AL, et al. Functional connectivity in the resting brain: a network analysis of the default mode hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:253–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

81. Qin P, Northoff G. How is our self related to midline regions and the default-mode network? Neuroimage. 2011;57:1221–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

82. Spreng RN, Mar RA, Kim ASN. The common neural basis of autobiographical memory, prospection, navigation, theory of mind, and the default mode: a quantitative meta-analysis. J Cogn Neurosci. 2009;21:489–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

The common neural basis of autobiographical memory, prospection, navigation, theory of mind, and the default mode: a quantitative meta-analysis. J Cogn Neurosci. 2009;21:489–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

83. Menon V, Uddin LQ. Saliency, switching, attention and control: a network model of insula function. Brain Struct Funct. 2010;214:655–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

84. Seeley WW, Menon V, Schatzberg AF, et al. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2349–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

85. Dosenbach NUF, Fair DA, Miezin FM, et al. Distinct brain networks for adaptive and stable task control in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11073–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

86. Lovero KL, Simmons AN, Aron JL, et al. Anterior insular cortex anticipates impending stimulus significance. Neuroimage. 2009;45:976–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

87. Seeley WW, Menon V, Schatzberg AF, et al. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2349–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Seeley WW, Menon V, Schatzberg AF, et al. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2349–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

88. Habas C, Kamdar N, Nguyen D, et al. Distinct cerebellar contributions to intrinsic connectivity networks. J Neurosci. 2009;29:8586–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

89. Koechlin E, Summerfield C. An information theoretical approach to prefrontal executive function. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007;11:229–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

90. Sheline YI, Barch DM, Price JL, et al. The default mode network and self-referential processes in depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1942–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

91. Mason MF, Norton MI, Van Horn JD, et al. Wandering minds: the default mode network and stimulus-independent thought. Science. 2007;315:393–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

92. Koch SBJ, van Zuiden M, Nawijn L, et al. Aberrant resting-state brain activity in posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33:592–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Aberrant resting-state brain activity in posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33:592–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

93. Lanius RA, Bluhm RL, Coupland NJ, et al. Default mode network connectivity as a predictor of post-traumatic stress disorder symptom severity in acutely traumatized subjects. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;121:33–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

94. Sripada R, King AP, Welsh RC, et al. Neural dysregulation in post-traumatic stress disorder: evidence for disrupted equilibrium between salience and default mode brain networks. Psychosom Med. 2012;29:997–1003. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

95. Rabinak CA, Angstadt M, Welsh RC, et al. Altered amygdala resting-state functional connectivity in post-traumatic stress disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2011;2:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

96. Sripada RK, King AP, Garfinkel SN, et al. Altered resting-state amygdala functional connectivity in men with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2012;37:241–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2012;37:241–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

97. Jin C, Qi R, Yin Y, et al. Abnormalities in whole-brain functional connectivity observed in treatment-naive post-traumatic stress disorder patients following an earthquake. Psychol Med. 2014;44:1927–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

98. Bluhm RL, Williamson PC, Osuch EA, et al. Alterations in default network connectivity in posttraumatic stress disorder related to early-life trauma. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2009;34:187–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

99. Daniels JK, Mcfarlane AC, Bluhm RL, et al. Switching between executive and default mode networks in posttraumatic stress disorder: alterations in functional connectivity. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2010;35:258–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

100. Cisler JM, Scott Steele J, Smitherman S, et al. Neural processing correlates of assaultive violence exposure and PTSD symptoms during implicit threat processing: a network-level analysis among adolescent girls. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2013;214:238–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2013;214:238–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

101. Rabellino D, Tursich M, Frewen PA, et al. Intrinsic connectivity networks in post-traumatic stress disorder during sub- and supraliminal processing of threat-related stimuli. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;132:365–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

102. Hasenkamp W, Barsalou LW. Effects of meditation experience on functional connectivity of distributed brain networks. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012;6:38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

103. Simon R, Engström M. The default mode network as a biomarker for monitoring the therapeutic effects of meditation. Front Psychol. 2015;6:776. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

104. Hölzel BK, Lazar SW, Gard T, et al. How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011;6:537–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

105. Brewer JA, Worhunsky PD, Gray JR, et al. Meditation experience is associated with differences in default mode network activity and connectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:20254–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Meditation experience is associated with differences in default mode network activity and connectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:20254–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

106. Garrison KA, Zeffiro TA, Scheinost D, et al. Meditation leads to reduced default mode network activity beyond an active task. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2015;15:712–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

107. Farb NAS, Segal ZV, Mayberg H, et al. Attending to the present: mindfulness meditation reveals distinct neural modes of self-reference. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2007;2:313–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

108. Jang JH, Jung WH, Kang DH, et al. Increased default mode network connectivity associated with meditation. Neurosci Lett. 2011;487:358–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

109. Farb NAS, Segal ZV, Anderson AK. Mindfulness meditation training alters cortical representations of interoceptive attention. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2013;8:15–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

110. Zeidan F, Martucci KT, Kraft RA, et al. Neural correlates of mindfulness meditation-related anxiety relief. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2013;9:751–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

111. Paul NA, Stanton SJ, Greeson JM, et al. Psychological and neural mechanisms of trait mindfulness in reducing depression vulnerability. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2013;8:56–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

112. Doll A, Hölzel BK, Boucard CC, et al. Mindfulness is associated with intrinsic functional connectivity between default mode and salience networks. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015;9:461. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

113. McTeague LM, Goodkind MS, Etkin A. Transdiagnostic impairment of cognitive control in mental illness. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;83:37–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

114. Downar J, Blumberger DM, Daskalakis J. The neural crossroads of psychiatric illness: an emerging target for brain stimulation. Trends Cogn Sci. 2016;20:107–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Trends Cogn Sci. 2016;20:107–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

115. Wang X, Xu M, Song Y, et al. The network property of the thalamus in the default mode network is correlated with trait mindfulness. Neuroscience. 2014;278:291–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

116. Liddell BJ, Brown KJ, Kemp AH, et al. A direct brainstem-amygdala-cortical “alarm” system for subliminal signals of fear. Neuroimage. 2005;24:235–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

117. Phillips ML, Williams LM, Heining M, et al. Differential neural responses to overt and covert presentations of facial expressions of fear and disgust. Neuroimage. 2004;21:1484–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

118. Williams LM, Liddell BJ, Kemp AH, et al. Amygdala-prefrontal dissociation of subliminal and supraliminal fear. Hum Brain Mapp. 2006;27:652–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

119. Williams LM, Liddell BJ, Rathjen J, et al. Mapping the time course of nonconscious and conscious perception of fear: an integration of central and peripheral measures. Hum Brain Mapp. 2004;21:64–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hum Brain Mapp. 2004;21:64–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

120. Porges SW. The polyvagal theory: neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. New York (NY): Norton; 2011. [Google Scholar]

121. Porges SW. The polyvagal perspective. Biol Psychol. 2007;74:116–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

122. Rabellino D, Densmore M, Frewen PA, et al. The innate alarm circuit in post-traumatic stress disorder: conscious and subconscious processing of fear- and trauma-related cues. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2016;248:142–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

123. Rabellino D, Densmore M, Frewen PA, et al. Aberrant functional connectivity of the amygdala complexes in PTSD during subconscious processing of trauma-related stimuli. PLoS ONE. 2016;15:e0163097. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

124. Harricharan S, Rabellino D, Frewen P, et al. fMRI functional connectivity of the periaqueductal gray in PTSD and its dissociative subtype. Brain Behav. 2016;6:e00579. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brain Behav. 2016;6:e00579. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

125. Steuwe C, Daniels JK, Frewen PA, et al. Effect of direct eye contact in PTSD related to interpersonal trauma: an fMRI study of activation of an innate alarm system. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2014;9:88–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

126. Steuwe C, Daniels JK, Frewen PA, et al. Effect of direct eye contact in women with PTSD related to interpersonal trauma: psycho-physiological interaction analysis of connectivity of an innate alarm system. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2015;232:162–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

127. Schauer M, Elbert T. Dissociation following traumatic stress. Zeitschrift für Psychol J Psychol. 2010;218:109–27. [Google Scholar]

128. Kozlowska K, Walker P, McLean L, et al. Fear and the defense cascade. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2015;23:263–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

129. Cole MA, Muir JJ, Gans JJ, et al. Simultaneous treatment of neurocognitive and psychiatric symptoms in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder and history of mild traumatic brain injury: a pilot study of mindfulness-based stress reduction. Mil Med. 2015;180:956–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mil Med. 2015;180:956–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

130. Earley MD, Chesney MA, Frye J, et al. Mindfulness intervention for child abuse survivors: a 2.5-year follow-up. J Clin Psychol. 2014;70:933–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

131. Goldsmith RE, Gerhart JI, Chesney SA, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for posttraumatic stress symptoms: building acceptance and decreasing shame. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2014;19:227–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

132. Kearney DJ, McDermott K, Malte C, et al. Association of participation in a mindfulness program with measures of PTSD, depression and quality of life in a veteran sample. J Clin Psychol. 2012;68:101–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

133. Kearney DJ, Mcdermott K, Malte C, et al. Effects of participation in a mindfulness program for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized controlled pilot study. J Clin Psychol. 2013;69:14–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

134. Kimbrough E, Magyari T, Langenberg P, et al. Mindfulness intervention for child abuse survivors. J Clin Psychol. 2010;66:17–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mindfulness intervention for child abuse survivors. J Clin Psychol. 2010;66:17–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

135. Bergen-Cico D, Possemato K, Pigeon W. Reductions in cortisol associated with primary care brief mindfulness program for veterans with PTSD. Med Care. 2014;52:S25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

136. Possemato K, Bergen-Cico D, Treatman S, et al. A randomized clinical trial of primary care brief mindfulness training for veterans with PTSD. J Clin Psychol. 2016;72:179–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

137. Niles BL, Klunk-Gillis J, Ryngala DJ, et al. Comparing mindfulness and psychoeducation treatments for combat-related PTSD using a telehealth approach. Psychol Trauma. 2012;4:538–47. [Google Scholar]

138. Polusny MA, Erbes CR, Thuras P, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for posttraumatic stress disorder among veterans a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314:456–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

139. Gallegos AM, Lytle MC, Moynihan JA, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction to enhance psychological functioning and improve inflammatory biomarkers in trauma-exposed women: a pilot study. Psychol Trauma. 2015;7:525–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Psychol Trauma. 2015;7:525–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

140. Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, et al. The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. J Trauma Stress. 1995;8:75–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

141. Stephenson KR, Simpson TL, Martinez ME, et al. Changes in mindfulness and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among veterans enrolled in mindfulness-based stress reduction. J Clin Psychol. 2017;73:201–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

142. King AP, Erickson TM, Giardino ND, et al. A pilot study of group mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) for combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Depress Anxiety. 2013;30:638–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

143. Kim SH, Schneider SM, Bevans M, et al. PTSD symptom reduction with mindfulness-based stretching and deep breathing exercise: randomized controlled clinical trial of efficacy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:2984–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

144. Rosenthal JZ, Grosswald S, Ross R, et al. Effects of transcendental meditation in veterans of operation enduring freedom and operation Iraqi freedom with posttraumatic stress disorder: a pilot study. Mil Med. 2011;176:626–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rosenthal JZ, Grosswald S, Ross R, et al. Effects of transcendental meditation in veterans of operation enduring freedom and operation Iraqi freedom with posttraumatic stress disorder: a pilot study. Mil Med. 2011;176:626–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

145. Catani C, Kohiladevy M, Ruf M, et al. Treating children traumatized by war and Tsunami: a comparison between exposure therapy and meditation-relaxation in north-east Sri Lanka. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9:22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

146. Bormann JE, Oman D, Walter KH, et al. Mindful attention increases and mediates psychological outcomes following mantram repetition practice in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Med Care. 2014;52:S13–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

147. Kearney DJ, Malte CA, McManus C, et al. Loving-kindness meditation for posttraumatic stress disorder: a pilot study. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26:426–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

148. Kearney DJ, Mcmanus C, Malte CA, et al. Loving-kindness meditation and the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions among veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Med Care. 2014;52:S32–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Med Care. 2014;52:S32–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

149. Neuner F, Catani C, Ruf M, et al. Narrative exposure therapy for the treatment of traumatized children and adolescents (KidNET): from neurocognitive theory to field intervention. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2008;17:641–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

150. Yehuda R, Hoge CW, McFarlane AC, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2015;1:15057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

151. Zoladz PR, Diamond DM. Current status on behavioral and biological markers of PTSD: a search for clarity in a conflicting literature. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37:860–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

152. Baker DG, Nievergelt CM, O’Connor DT. Biomarkers of PTSD: neuropeptides and immune signaling. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:663–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

153. Nazarov A, Jetley R, McNeely H, et al. Role of morality in the experience of guilt and shame within the armed forces. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;132:4–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

154. Ma SH, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: replication and exploration of differential relapse prevention effects. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:31–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

155. Piet J, Hougaard E. The effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for prevention of relapse in recurrent major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:1032–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

156. Hiraoka R, Meyer EC, Kimbrel NA, et al. Self-compassion as a prospective predictor of PTSD symptom severity among trauma-exposed U.S. Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:127–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

ᐈ PTSD Diagnosis ~【Post Traumatic Stress Disorder】

Post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, is a severe mental condition that progresses as a result of a single or recurring event that has a negative impact on a person's mental health. Symptoms of PTSD can appear immediately or several months after the injury.

Symptoms of PTSD can appear immediately or several months after the injury.

The likelihood of developing post-traumatic stress disorder is the same for patients of different age groups. The main risk factor is the severity of the injury, the initial state of the psyche, psychological and biological predisposition.

Classification

In the modern classification, 4 types of post-traumatic syndrome are distinguished:

Acute.

Appears in the first days after a stressful situation. Symptoms appear very brightly within 2-3 months.

Chronic.

Characterized by a gradual increase in signs of pathology, exhaustion of the nervous system, changes in character and interests.

Deformation.

Manifested in patients with a long-term chronic mental disorder. Progress leads to the formation of phobias, neuroses, feelings of anxiety.

Delayed.

The clinical picture becomes apparent 3-6 months after the injury. Various external stimuli can provoke the progress of PTSD.

Various external stimuli can provoke the progress of PTSD.

There are also 3 stages of PTSD: acute, chronic and delayed.

In the first case, this is the period of the beginning of an extreme situation. The state is saved until it ends. Characterized by excessive anxiety for one's own life, lethargy, confusion.

A chronic condition occurs after the trigger has been removed if the patient feels restless. It is possible that the clouding of the mind persists, the person does not understand what happened. Often there are changes in speech and motor functions.

In some cases, with PTSD, the stages of such a plan are not observed, a delayed form appears, that is, the characteristic symptoms appear after a few months, and before that the patient feels normal.

This medical problem also varies in severity. With a mild course of post-traumatic syndrome, the patient's state of health remains unchanged, the ability to work professionally and the ability to communicate with other individuals is preserved. With a severe degree of damage, chronic mental disorders are diagnosed, schizophrenia is possible. With prolonged progress, PTSD leads to malfunctions of the brain, affects the functioning of the endocrine and nervous systems.

With a severe degree of damage, chronic mental disorders are diagnosed, schizophrenia is possible. With prolonged progress, PTSD leads to malfunctions of the brain, affects the functioning of the endocrine and nervous systems.

Post-traumatic syndromes are characterized by diverse signs, depending on which the division into clinical types is provided: When detecting post-traumatic stress disorder, the main task of a specialist is to correctly differentiate the diagnosis by establishing the type and type. The main factor provoking post-traumatic stress disorder is a tragic event, a traumatic situation. A psychologically healthy person can face PTSD, but the course of the disease will be easier for him than for a person with a shaken psyche. In all cases, the syndrome has an undulating course, often leading to a permanent change in personality. There is a reassessment of one's own ideals, one's importance in life, a change in old ideas. The list of PTSD symptoms includes the following changes: According to statistics, the disease in children is detected no more often than in adults, but experts in the field of psychotherapy assure that the disorder in children progresses faster. Children are a risk group due to an increased predisposition to post-traumatic stress syndrome, impressionability and sensitivity. The reasons for the development of the problem in children are psychological trauma, unfavorable social conditions and individual developmental characteristics. Pathology is diagnosed by a child psychiatrist. The doctor determines what traumatic event occurred and what changes in the nervous system it provoked. During the diagnosis, the patient's reaction to the impact of stimuli is assessed, the presence of memories reproduced in a dream, during a game or in stories is clarified. A consultation with a child psychologist will allow you to establish the type of disorder, determine the scheme of influence and establish a prognosis for recovery. Treatment of PTSD in children is a long-term work with a child psychologist or psychotherapist. Complex therapy requires the combined use of several techniques. The patient is shown cognitive-behavioral correction, psychotherapy and drug treatment aimed at stabilizing the work of the central nervous system. The diagnosis of PTSD should not be ignored. Over time, the problem can worsen and lead to irreversible complications. Only acute disorders can be corrected, after the transition to a chronic form, therapy is complicated, a pathological change in personality is observed. A person manifests pronounced narcissistic qualities, the development of alcoholism and drug addiction is not excluded. Together, these factors are unfavorable signs, and therefore aggravate the prognosis for recovery. Post-traumatic stress disorder is established on the basis of the patient's complaints about psychological trauma, tragic events in the past. Self-testing for PTSD is not always accurate because some factors may be hidden. Often the psychiatrist recommends an additional consultation in the presence of relatives or people from close circle. This allows you to differentiate the diagnosis and exclude the presence of other, symptomatically similar diseases. The treatment of PTSD is determined individually, taking into account the characteristics of the patient, the type of pathology and the presence or absence of concomitant disorders. The most effective are cognitive behavioral therapy and hypnotherapy. According to the indications, psychotherapy is combined with medication. Treatment of PTSD often requires the use of adrenergic blockers, antidepressants, tranquilizers, neuroleptics. As auxiliary methods, therapeutic massage is used. A rehabilitation doctor or psychotherapist can help prevent the development of serious problems. The doctor should explain to the patient that an acute reaction to stress is normal for the human body. Another prevention of PTSD is to avoid possible stress and maintain mental balance. The article is for informational purposes only. Please remember: self-medication can harm your health. The author of the article: Kulik Maria Sergeevna Doctor-psychologist of the second category If a problem is found, the patient should consult a psychiatrist. Specialists of the MEDICOM clinic working with the latest techniques will help you to undergo high-quality diagnostics and treatment of PTSD in Kyiv. You can seek help and take a test for PTSD at the clinic's subdivisions located in Obolon and Pechersk. Mental health requires careful attention, so it is better to contact professionals! all specialists The main causes of PTSD

Causes of PTSD include:

Clinical symptoms of PTSD

PTSD in children: features

Complications

Diagnostics

Diagnosis of PTSD is provided with the help of special questionnaires confirming the presence of criteria similar to the disease.

Diagnosis of PTSD is provided with the help of special questionnaires confirming the presence of criteria similar to the disease. Treatment

Prevention of PTSD

The main task is to start the impact immediately after the injury, to work out the event in a quality manner in order to prevent the problem from becoming chronic. Also, to prevent the development of post-traumatic stress disorder will help:

The main task is to start the impact immediately after the injury, to work out the event in a quality manner in order to prevent the problem from becoming chronic. Also, to prevent the development of post-traumatic stress disorder will help:

Sources

Which doctor treats PTSD?

If signs of PTSD are found in a child, consultation with a child psychiatrist or psychologist is necessary. The consequences of PTSD can be irreversible, so it is very important to undergo a full examination, determine the type of pathology, establish the cause and work out a treatment regimen.

If signs of PTSD are found in a child, consultation with a child psychiatrist or psychologist is necessary. The consequences of PTSD can be irreversible, so it is very important to undergo a full examination, determine the type of pathology, establish the cause and work out a treatment regimen. Certificates

Reviews

10/23/2021 18:14

Alexander

To the author. Definitely, PTSD is really serious. Skoda, which doctors know, do not outperform neither sick nor relatives. I broke my ankle for 3 years: 4 operations, then 3 fates in the police, fear that I would become disabled, depression, and the pressure of my relatives simply made me crazy. I don’t show how self-tapping can come in. Obov'yazkovo idit to the psychologist.

I don’t show how self-tapping can come in. Obov'yazkovo idit to the psychologist.

11.09.2021 20:40

Galina Andriivna Sinyavska

She licked on the wet bed near the kitchen. I had a compression fracture of the ridge, I wanted to die. I had to visit a psychologist. Without її help, I would not have run into it. The psychologist gave a reason to overcome fears and come to the solution of the problem.

07/30/2021 10:47

Valentina

Thank you majesty, that important article was written with grace. I learned a lot of new things. At once, I’ll lie on the knight with a fracture, I’ll be respectful to the new. I would not have thought before that about the mental state of a person after a serious injury, you also need to be turbulent.

15.06.2021 18:26

Vitaly

Thank you for the information and help. Kulik Maria Sergeevna is a very good specialist. So far, we have come to the consultation without the child, in order to reconnoiter the situation, so to speak. The doctor was very friendly, asked a lot of questions, then gave recommendations on how to behave with our son after being beaten by classmates at school. He is very closed, and we are slowly slipping into despair. Now the only hope is for Maria Sergeevna.

The doctor was very friendly, asked a lot of questions, then gave recommendations on how to behave with our son after being beaten by classmates at school. He is very closed, and we are slowly slipping into despair. Now the only hope is for Maria Sergeevna.

05/22/2021 11:55

Olga

I thank Kulik Mariya Sergievna for help. We have fired houses, it became late at night. Thank you to relatives from Kiev, who gave them a seat. Alesina became unrecognizable. The axis of infection from Sergiyk seems to be a psychologist, who at night finds uncontrollable panic on him, and it is unrealistic to calm down. Already after the third session, I remembered the progress.

05/01/2021 12:21

Mikhailo Valentinovich

Thank you for the information. Children are especially susceptible to mental trauma at a time. Recently, my team died of cancer, I can’t know the language of the child, although earlier we were closer. At the nearest future, I will turn to her for help to a psychologist.

04/11/2021 13:32

Leonid

I like a good article and service, I often look in when something hurts for information on symptoms and diseases. But I'm interested in PTSD. How did we experience stress in our childhood without psychologists and corrective methods? Like normal grew.

12/16/2020 18:16

Grigory Titov

Very good service, they cover a lot of relevant topics, and most importantly, they immediately write which specialist you can contact for help. We went to MEDIKOM to Maria Sergeevna, a cool psychologist. The child stuttered and was very complex about this. But with the joint efforts of a speech therapist and a psychologist, the situation was corrected. Nikita is now studying, and successfully, in the 8th grade. He became very cheerful and sociable.

Show 3 more

Total 8 reviews

leave feedback

What is PTSD syndrome and why is it dangerous?

Prolonged exposure to severe stressors can lead to the formation of a traumatic mental disorder. We tell you what leads to the appearance of PTSD and what to do if you find its signs in yourself?

We tell you what leads to the appearance of PTSD and what to do if you find its signs in yourself?

Anna Zalesskaya

Getty Images

Daria Milay

clinical psychologist, psychotherapist, author of books and innovative psychotherapeutic methods

What is PTSD syndrome?

symptoms, signs, stages

PTSD is a delayed reaction to a severe, stressful event or situation that happened in the past. A person cannot overcome what happened, his attention is focused on a psycho-traumatic episode, which makes him live the worst moments and the emotions, feelings and experiences that accompany them again and again.

There are several stages:

- Acute (lasts about 6 weeks after the traumatic event). A person experiences pronounced anger, fear, irritability, anxiety. At this moment, the timely help of a specialist and the support of loved ones is needed.

- Chronic (lasts from 7 weeks to 6 months). The appearance of various kinds of phobias, behavioral disorders, a feeling of eternal fatigue, unwillingness to live. The victim has a low chance of a full recovery.

- Delayed (several years after the events). There is an exacerbation of the symptoms of PTSD, a person tries to escape from reality, may succumb to various kinds of addictions or fall into the deepest depression. A cure at this stage is almost impossible; what remains is control and maintenance of an acceptable state.

Symptoms:

- dissociation - constant thoughts about what happened, involuntary vivid memories, emotions about the traumatic factor;

- avoidance - attempts to repress, forget traumatic events, refusal to talk about them, apathy, lack of interest in the present, loneliness, feeling of uselessness;

- physiological hyperactivity - a subconscious desire to always “run away” somewhere, anger, irritability, excitability, sleep problems.

Types of PTSD

Anxious

A person cannot sleep peacefully, his mood fluctuates, he is unable to adapt in society - and all because of attacks of high anxiety for no reason.

Asthenic

Complete indifference to what is happening around, a sense of inadequacy, lack of appetite.

Dysphoric

High level of irritability, aggression, often after a surge of negative emotions a person feels satisfaction or, conversely, shame.

Somatomorphic

Clinical disorders of various body systems or internal organs appear. The person begins to experience the fear of death.

What causes PTSD and how does it develop?

PTSD develops gradually. Trauma occurs immediately at the moment of exposure to a traumatic factor and two more days after. PTSD is formed in a week due to the concentration on the events that have occurred and their consequences. Extremely rarely, PTSD can be caused by domestic problems - divorce, lawsuits, a big loss, loss of housing.

PTSD is formed in a week due to the concentration on the events that have occurred and their consequences. Extremely rarely, PTSD can be caused by domestic problems - divorce, lawsuits, a big loss, loss of housing.

Internal causes of PTSD:

age;

low level of intelligence;

increased level of emotionality, anxiety;

taking drugs and alcohol;

sociopathy;

old psychotrauma or mental problems.

In this case, the syndrome can develop not only among the direct participants in the events, but also among observers.

Who is at risk?

There are several categories of people at risk of developing PTSD:

Representatives of law enforcement agencies - they are most often at risk of developing a disorder.

Women. Highly emotional, as well as those who often endure violence.

Children and teenagers.