Ocd and procrastination

OCD and Compulsive Procrastination | Psychology Today

Source: cottonbro/pexels

Did you know that OCD can actually inhibit your ability to clean your house?

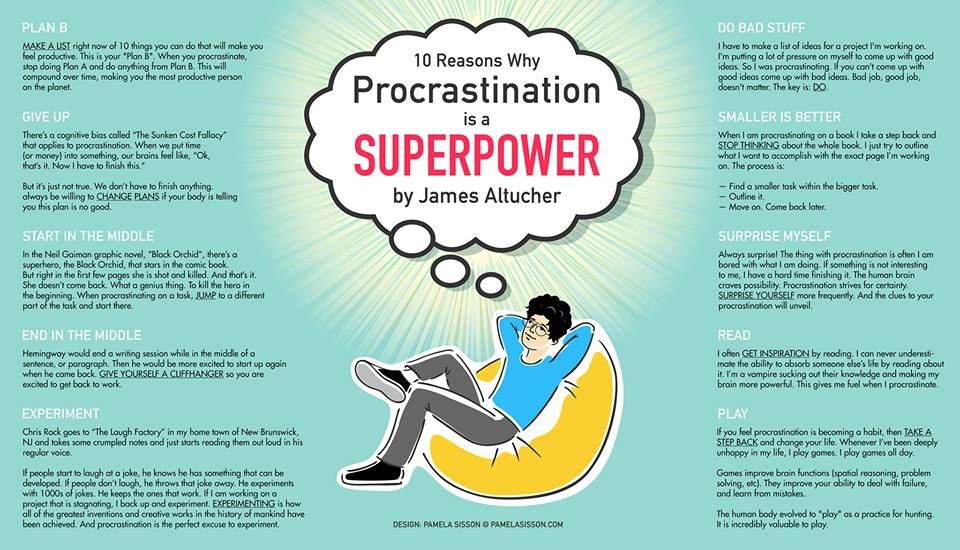

Ask why people procrastinate, and you’ll likely get answers such as avoidance, distraction, or sheer laziness. One you probably won’t hear is OCD, a disorder commonly associated with excessive focus and attention to detail. However, the devilish nature of OCD allows it to manifest in counterintuitive ways. Associated with OCD are symptoms that feed directly into procrastination: repetitive behavior, compulsive avoidance, and anxiety about the future. Understanding OCD can help us recognize and escape the cycle of procrastination — whether or not one has the disorder.

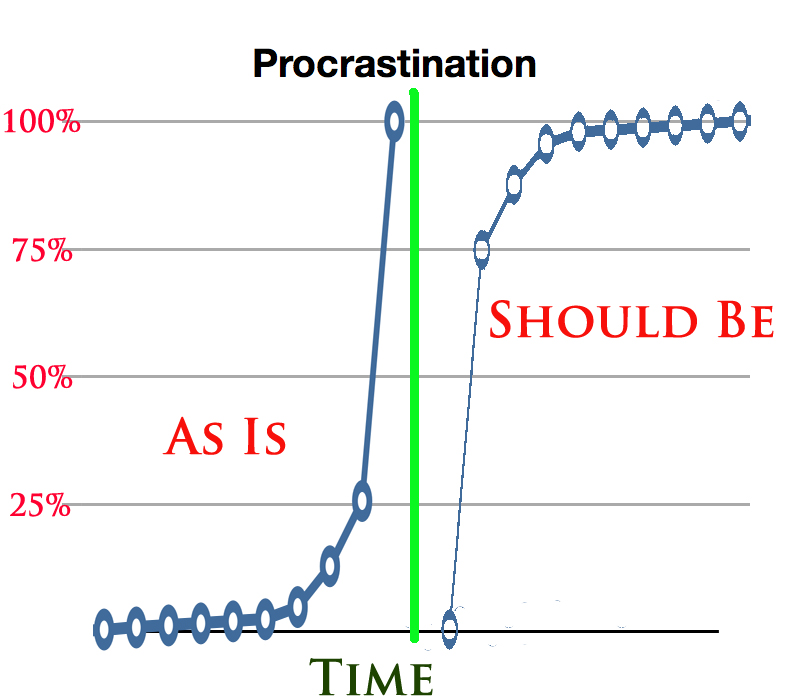

Procrastination is related to a cognitive error in the coordination of cause-effect relationships, as described by Niklas Törneke: "Take the rule 'In order to recover, I have to avoid pain.' Based on this rule, the individual might act in a way meant to keep pain away, and as a result, he won’t experience that the short-term and long-term consequences specified in the rule (not feeling pain and recovering) are not coordinated over time.

The person takes action to avoid pain and pain is avoided, so the behavior is negatively reinforced… tracking of relatively short-term consequences (limited physical activity → no pain) will block tracking of more long-term consequences (activity → pain → recovery). This becomes a vicious circle where well-functioning short-term tracking does not work in the long run. However, the fact that this tracking works in the short term means there is a risk that the governing function of the rule as a whole is reinforced." (Törneke)

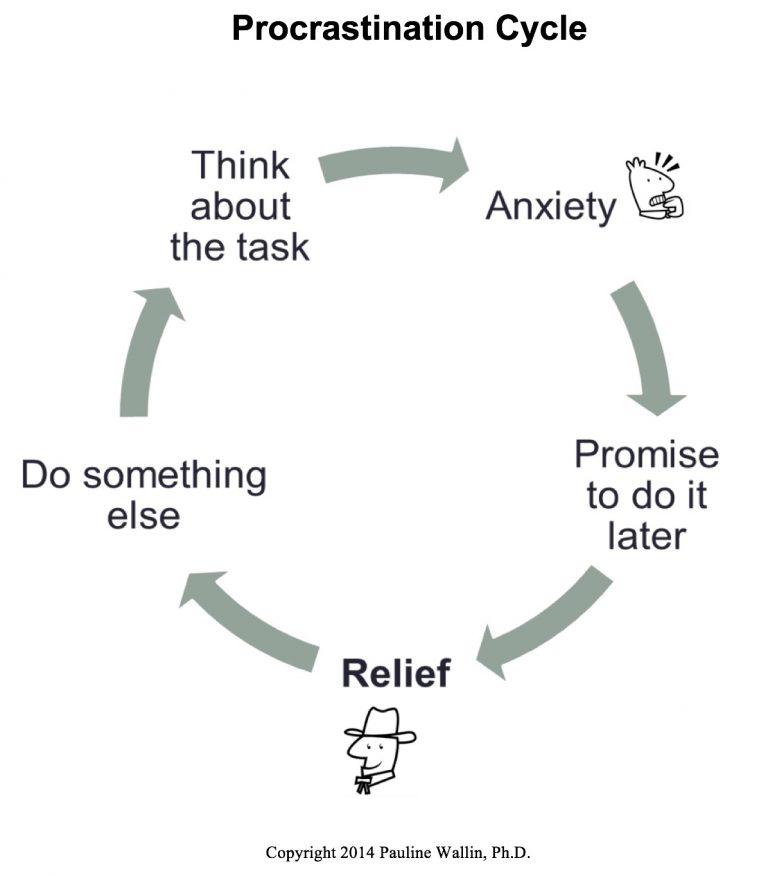

Once you understand this cycle, it’s apparent that OCD can feed into procrastination. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder is fueled by a cycle of uncertainty, aversion, and repetition. It starts when you experience anxiety related to an uncertain threat, like illness or death; you perform an action intended to hold the threat at bay; and, when that action doesn’t completely eliminate your feared outcome with 100% certainty, you repeat it until it becomes a compulsive ritual.

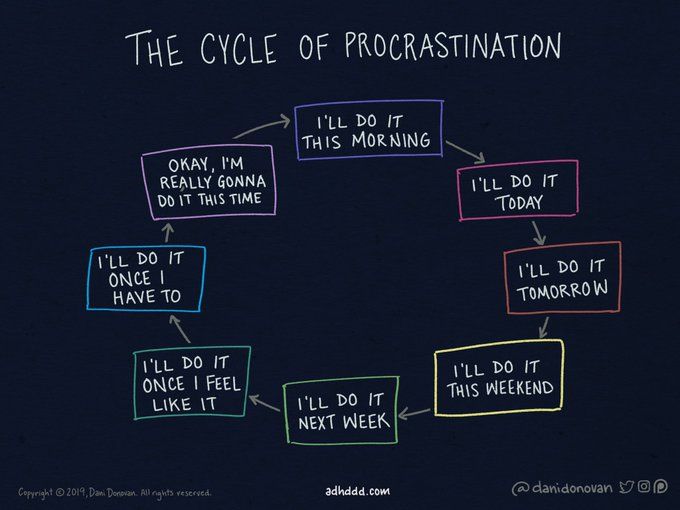

With procrastination, you are faced with a particular task that you desperately want to avoid; you devise another activity to perform instead; and when that activity is over and you find yourself back where you started, you begin another cycle to hold it off a little longer. And, as is always the case with Obsessive-Compulsive rituals, this can easily spiral out of control, wasting time and energy on useless repetition while exacerbating the original problem.

So how do you break the cycle of compulsive procrastination? Here are two suggestions that might be helpful:

1. Look creatively at the task you’re trying to avoid and see if there’s a less burdensome way of approaching the problem. Here’s a simple, personal example: I used to hate shaving and put it off for as long as possible; my facial hair would oscillate between “ruggedly handsome” and “borderline neckbeard” on a regular 3-to-4 day cycle. This went on until, as I was consciously experimenting with different strategies, I discovered that shaving with a safety razor under a hot shower only took me a minute or so, and was virtually effortless. The solution was simple in retrospect, but if I hadn’t tried out new strategies I’d still be procrastinating and wearing a neckbeard twice a week. Brainstorming a list or consulting with friends or treatment providers is a good place to start. Even if an idea seems silly, it’s usually at least worth a try. Trying and rejecting a hundred somewhat inane ideas is all worth it when you find the one that turns your pet peeve into a nonissue.

The solution was simple in retrospect, but if I hadn’t tried out new strategies I’d still be procrastinating and wearing a neckbeard twice a week. Brainstorming a list or consulting with friends or treatment providers is a good place to start. Even if an idea seems silly, it’s usually at least worth a try. Trying and rejecting a hundred somewhat inane ideas is all worth it when you find the one that turns your pet peeve into a nonissue.

2. A second method for challenging compulsive procrastination is to break down the task you’re avoiding into smaller, more manageable chunks. Making small but measurable progress on a task fosters a sense of accomplishment, while reducing associated aversion. If you hate vacuuming, maybe start by just vacuuming a single room or piece of furniture — sometimes just flipping the "on" switch is a good place to start. Even if it seems inconsequential, it helps to build momentum and disrupt the cycle of inertia. Any progress is still better than none.

One of the things that makes OCD so frustrating is its ability to manifest in unanticipated ways. Procrastination is just one way OCD can catch you off guard and complicate your life from an unexpected angle. But like all OCD symptoms, understanding procrastination reveals obvious patterns — and opportunities to change for the better.

Procrastination is just one way OCD can catch you off guard and complicate your life from an unexpected angle. But like all OCD symptoms, understanding procrastination reveals obvious patterns — and opportunities to change for the better.

Copyright, Fletcher Wortmann, 2020

When Obsessive-Compulsive Thoughts Are 'Triggered' : NPR

When Obsessive-Compulsive Thoughts Are 'Triggered' In his memoir Triggered: A Memoir of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, Fletcher Wortmann describes the intrusive, overwhelming anxieties that plagued him, and recounts how he gradually learned to cope with what some call the "doubting disorder."

Author Interviews

Heard on Talk of the Nation

NPR Staff

When Obsessive-Compulsive Thoughts Are 'Triggered'

From a young age, Fletcher Wortmann spent countless hours absorbed by his obsessions. In third grade, he became consumed with the idea that every nonwater substance on the planet would soon freeze. He spent hours laying plans for how he and his family would survive. Over and over, he replayed an imagined apocalypse.

In third grade, he became consumed with the idea that every nonwater substance on the planet would soon freeze. He spent hours laying plans for how he and his family would survive. Over and over, he replayed an imagined apocalypse.

Though he wouldn't be diagnosed until many years later, in retrospect Wortmann realizes the episode marked his "first full-blown bout" with obsessive-compulsive disorder.

In his memoir Triggered, Wortmann examines the origins of his anxieties and how he came to be overwhelmed by intrusive thoughts.

"One of the most ... misunderstood aspects of OCD," Wortmann tells NPR's Neal Conan, "is that many people believe that it has to involve visible physical compulsion, such as hand-washing or counting or organizing things."

After his sophomore year in college, Wortmann was diagnosed with purely obsessional obsessive-compulsive disorder — also called "pure O" — where the compulsive behaviors are entirely internal, intrusive thoughts.

"I think everyone experiences these kind of things. Your mind will just sort of settle on something really distressing and upsetting, and ... most people are able to shake it off. Unfortunately, with obsessive-compulsive disorder, the thoughts take on kind of a life of [their] own, and you begin to wonder: 'What do these mean? How can I make them go away?' "

He discusses how he gradually learned to cope with what some call the "doubting disorder."

Interview Highlights

Fletcher Wortmann was diagnosed with a form of obsessive-compulsive disorder after his sophomore year in college. Cydney Ambrose hide caption

toggle caption

Cydney Ambrose

Fletcher Wortmann was diagnosed with a form of obsessive-compulsive disorder after his sophomore year in college.

Cydney Ambrose

On the challenges of diagnosis

"I'd had a number of therapists growing up. I eventually had a breakdown and was brought to McLean Hospital, and up to the point of that hospitalization, people misunderstood, misdiagnosed. They would try to reassure me ... those thoughts don't mean anything, which ironically is the worst thing you can do for someone with OCD, because trying to reassure them and tell them that they are safe, it doesn't help with the fundamental issue of uncertainty and just sort of serves as another ritual, another metaphorical hand-washing that can't really give them the absolute certainty they would desire."

On thinking of OCD as a third-person character

"There's an almost schizophrenic aspect to it sometimes. There's a sense of being taunted by someone, the way it continually hones in on your worst fears and traumas and anxieties. There's a very adversarial aspect to it.

There's a very adversarial aspect to it.

"And ironically, I think overcoming that has been part of my successful treatment because eventually you have to learn ... OCD is, it's like diabetes. It's a condition. It's not something I'll ever be able to completely exorcise or cure.

"So accepting it just as a psychological mechanism, rather than as my evil doppelganger, has been very helpful."

On using exposure response therapy to treat OCD

"What I had to do [was] ... sit down and face directly whatever it was I was afraid of without performing the ritual to try to protect myself. ... Mine was tricky and kind of weird to describe because of the purely obsessional thoughts. ...

"I had friends who had contamination issues who would have to sit there with their hands in a toilet for two hours without washing, or with their hands in a bucket of biohazard junk.

"And it's a terrible, challenging, traumatizing process. ... But I found through ERP [exposure response therapy] I was able to really confront the things I was frightened of without obsession and eventually managed my disorder much better. "

"

On taking medication for OCD

"I was very hesitant to take medication, and I think because of this cultural myth we have that medication turns you into a zombie or a robot, or it changes who you are. That hasn't been my experience. I found it's been useful in helping me get into a place where the exposure response therapy ... was more acceptable and doable and less painful.

"And that myth of psychiatric medication as a kind of, you know, giving up or selling out, that really disturbs me because I think that's part of what prevented me from really seeking out this kind of help I needed for so long. And I wonder how many other people out there are resisting therapy when they could really benefit from it."

On procrastination as a symptom of OCD

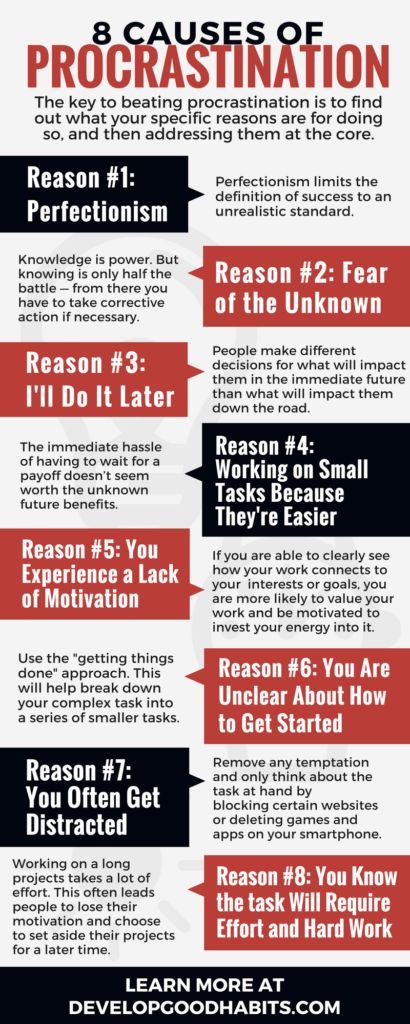

"It's funny — procrastination can be a symptom of OCD in the sense that because you know a project will require so much of your effort, and you're so frightened of screwing up, it's easy to just keep putting it off and putting it off and putting it off. ...

...

"I was really excited about writing Triggered. I think my primary issue was in editing and revising it and trying to make the text absolutely perfect. And of course there are any number of changes that have to be made as part of the publication process. ... They'd come to me, and they'd say, 'Oh, you can't use those song lyrics for legal reasons.' And I'd be like, 'Ah, you've plunged a knife into my chest.' "

Sponsor Message

Become an NPR sponsor

"No, I'm not just lazy": how to understand that your procrastination is a sign of illness

Ask a friend a question: why do we procrastinate? Most likely, you will hear in response: “Well, we avoid work, we get distracted, sometimes we just get lazy.” Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) will probably not be mentioned by anyone. The main feature of OCD is excessive attention to detail. It would seem that a person obsessed with cleanliness should constantly tidy up the room. However, it is OCD that can keep him from cleaning up. We tell you how to understand that you are idle not because you are lazy, but because of anxiety, and how to deal with it.

We tell you how to understand that you are idle not because you are lazy, but because of anxiety, and how to deal with it.

How procrastination and OCD work

There is really nothing surprising about the connection between idleness and OCD. Some of the symptoms of this disorder lead directly to procrastination—repetitive behaviors, compulsive avoidance, anxious thoughts about the future. By understanding the features of OCD, you will learn to recognize the vicious cycle of procrastination.

Procrastination is associated with a cognitive error in coordinating cause and effect relationships. As psychiatrist Niklas Thorneke explains, it is that we reinforce behaviors that help us reach our immediate goals but get in the way of our long-term goals. For example, a person who has been injured might follow the rule, "In order to recover, I must avoid pain." As a result, he begins to move less, and this will really allow him not to feel pain. There will be a so-called negative reinforcement - avoiding unpleasant stimuli will help to consolidate the new habit. However, this behavior will hinder the long-term outcome of recovery.

However, this behavior will hinder the long-term outcome of recovery.

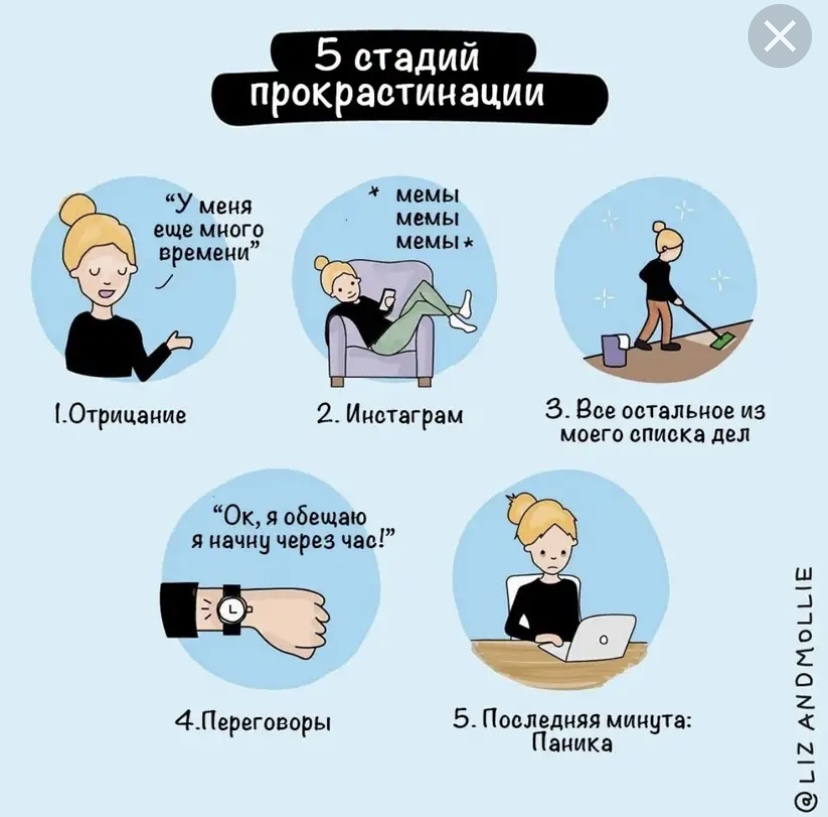

OCD begins with you experiencing anxiety about a vague threat, such as illness or death. Then you take actions to avoid the threat. When you realize that your actions did not completely eliminate the frightening outcome, you begin to repeat the action until it turns into a compulsive, that is, obsessive, ritual.

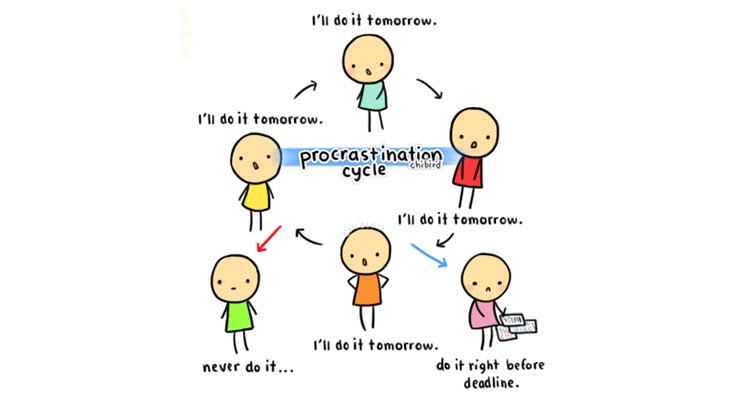

In the case of compulsive procrastination, you encounter a particular activity that you are desperately trying to avoid. Instead, you come up with another activity. When you complete it, your state becomes the same as it was before the start of this distracting activity, and you start it again. As with other obsessive-compulsive rituals, things can easily get out of control. You will start to waste a lot of time and energy on the useless repetition of the ritual, while your true problem only gets worse.

How to deal with procrastination

So how do you get out of the vicious cycle of compulsive procrastination? Try these two tips:

1. Look at the activity you're trying to avoid creatively and see if there's a less difficult way for you to approach it. For example, if you are a man, you may hate to shave and constantly put off shaving until your cheeks, chin and even neck are overgrown with stubble. If you experiment with different approaches to shaving, you may eventually find that you like to shave with a warm water safety razor. If you had not tried new ways, you would still put off shaving until the last, overgrown with stubble.

Look at the activity you're trying to avoid creatively and see if there's a less difficult way for you to approach it. For example, if you are a man, you may hate to shave and constantly put off shaving until your cheeks, chin and even neck are overgrown with stubble. If you experiment with different approaches to shaving, you may eventually find that you like to shave with a warm water safety razor. If you had not tried new ways, you would still put off shaving until the last, overgrown with stubble.

When you find yourself constantly putting off a task, just take a piece of paper and write down new ideas about solving it. Even if the idea seems stupid, try it anyway. Going through a hundred stupid ideas is not a waste of time if in the end you find one that will help you. Consulting with friends or a psychologist is also a good option.

2. The second way to deal with compulsive procrastination is to break a complex task into smaller, more manageable chunks. Even advancing one step creates a sense of achievement and reduces aversion to an unpleasant task. If you don't like vacuuming, then try to start with at least one room. Sometimes just getting started is an important step. Even if it seems insignificant, it is a necessary push that will help overcome the inertia of idleness. Even the smallest progress is better than no progress.

Even advancing one step creates a sense of achievement and reduces aversion to an unpleasant task. If you don't like vacuuming, then try to start with at least one room. Sometimes just getting started is an important step. Even if it seems insignificant, it is a necessary push that will help overcome the inertia of idleness. Even the smallest progress is better than no progress.

One of the tricky things about OCD is that it can show up in unexpected ways. Procrastination is just one of the manifestations of this disorder. However, as with all other manifestations of OCD, it is enough to understand how procrastination works, and you will see opportunities for overcoming it.

Only useful posts and stories on our Instagram

Tyranny of procrastination - offtopic on vc.ru

3046 views

On the origin, mechanisms and fight against the phenomenon of procrastination

Taylor Mitchell Brown First of all, we would fulfill our obligations, then we would embody personal desires and all our deadlines would be observed easily and naturally. But, unfortunately, such a world does not exist.

But, unfortunately, such a world does not exist.

The tendency to procrastinate is annoying. Whether we're avoiding paying bills, going to the dentist, or trying to sort things out after a trip, we often love putting off everyday tasks until tomorrow. But tomorrow, as you know, the desire to deal with pending cases also does not arise.

To deal with this phenomenon, we need to go back in time. Procrastination is the result of human evolution. We just haven't evolved enough to avoid her curse. Despite this sad fact, understanding procrastination is the best way to deal with it. And to understand it, we'll start by looking at momentum.

Impulse

Before mammals supplanted the once dominant reptiles on the surface of the planet, animals roamed the Earth without thinking too much about tomorrow. Impulses arose in their brains and they acted under their influence. These impulses are the main cause of procrastination.

Impulses are created by physiological mechanisms in the brain. A significant part of the impulses are bursts of dopamine, a biochemical substance that performs many functions in the body. Dopamine is a key element of the psychomotor and reward systems that encourage a person to do what he wants. In most cases, what we do is useful for survival.

A significant part of the impulses are bursts of dopamine, a biochemical substance that performs many functions in the body. Dopamine is a key element of the psychomotor and reward systems that encourage a person to do what he wants. In most cases, what we do is useful for survival.

The dopamine impulse consists of two parts. First, it motivates us to do what we desire. Let's say we want chocolate, which means that dopamine is being produced. Secondly, it makes us feel good: when we eat chocolate, the brain releases dopamine again. Both of these mechanisms create momentum, pushing us towards what we find enjoyable.

Animal life has been regulated by such impulses for hundreds of millions of years. The impulses made me satisfy desires right now and did not allow me to think about desires in the future. In other words, it would have been difficult for ancient creatures to understand how avoiding Starbucks coffee purchases today could greatly increase your savings at the end of the month. This ability came later.

This ability came later.

Foresight

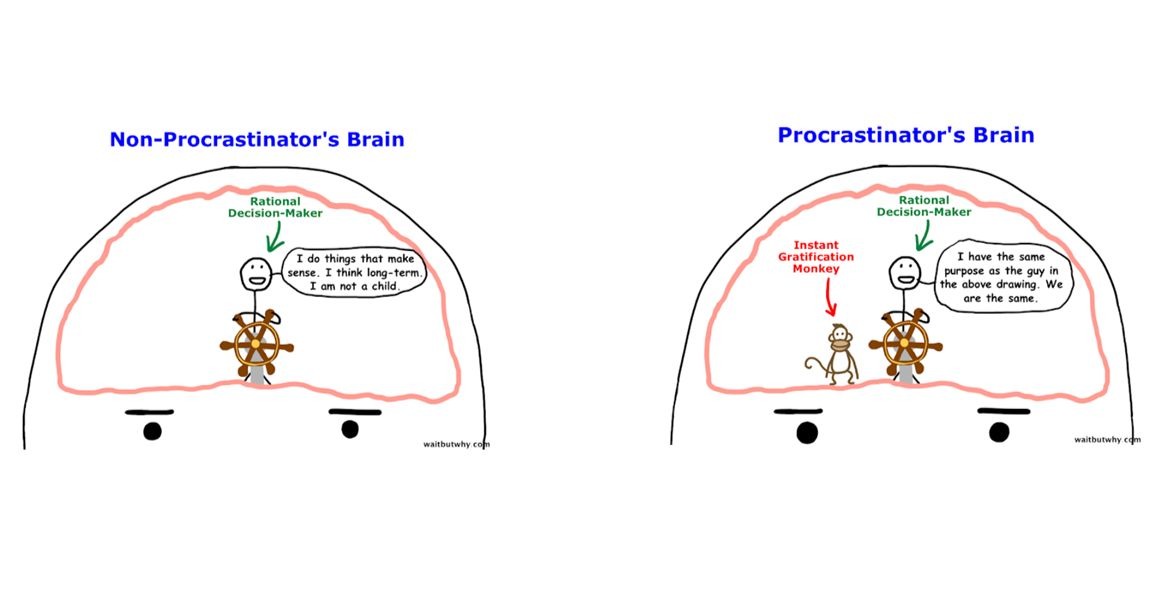

We could not develop the ability to suppress impulses until we learned to see into the future. It was necessary to accept the idea of the interaction of current goals and delayed goals. For the most part, this ability came about with the development of the frontal lobes of the brain: the larger they became, the better we could suppress immediate desires in favor of desires in the future.

The frontal lobes provide foresight by interacting with areas of the brain that generate bursts of dopamine. For example, when a dopamine signal occurs, it is first processed by the frontal lobes to determine whether it should be followed or not. If the frontal lobes, looking into the future, decide what is not needed, the impulse is suppressed.

The significance of the frontal lobes in impulse control is supported by research in clinical neurophysiology. For example, if a part of the prefrontal cortex is damaged in a person, he loses the ability to make connections between future rewards and what can be received right now. The result is an inability to defer rewards.

The result is an inability to defer rewards.

One of the most famous cases of damage to the frontal lobes is the case of Phineas Gage, who was pierced in the brain by a metal beam in an explosion. After the accident, he went from a respectable young man to an irritable brute: he spent all his money, lost his job, and treated all his friends horribly. In other words, he became a victim of momentary impulses.

The era of dinosaurs has been replaced by the era of mammals, armed with the best means of adaptation - the frontal lobes of the brain that control impulses. By occupying the niche that had opened up, they developed the ability to better see the future. This kind of clairvoyance allowed them to suppress momentary desires for the sake of future goals.

The never-ending battle

Procrastination occurs as a result of a battle between two systems - the strength of dopamine impulses, on the one hand, and the ability of the frontal lobes of the brain to suppress them, on the other. The loss of the frontal lobes means the victory of the impulses and the surrender of the person to them.

The loss of the frontal lobes means the victory of the impulses and the surrender of the person to them.

Overzealous dopamine activity is the cause of failure of the impulse control system. People taking drugs that restore dopamine circulation in the brain, such as those with Parkinson's disease or restless legs syndrome, develop an impulse control disorder, which is expressed in the occurrence of pathological gambling or compulsive shopping. In other words, their impulses become too strong to be ignored.

There are other problems with the frontal lobes. Some people, for example, from birth have the genetic features of dopamine receptors in the nerve cells of the frontal lobes of the brain. These features do not allow receptors to correctly understand the meaning of dopamine signals. Such people are more likely to suffer from disorders such as ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) and OCD (obsessive-compulsive disorder), which also affect the control of dopamine impulses.

The interplay between the frontal lobes and dopamine activity also explains our tendency to procrastinate. We respond to the temptation of immediate reward—checking Instagram, playing the guitar, or watching a series. If the frontal lobes are not strong enough to suppress the temptation, then we lose the ability to focus on the task at hand. The result is procrastination.

Know your enemy

I don't think procrastination can be completely beaten, but the damage from it can be minimized. The most promising way to do this is knowing that if you can clearly identify the factors that contribute to procrastination, you will be able to eliminate them more easily from your life. At least it gives hope.

The two most important reasons for procrastination are how long you have to wait for a result (distance) and how much you really want to do something. As a general rule, the longer the outcome, the more likely you are to procrastinate. The same applies to things you don't want to do: the less you want to do them, the more easily you are influenced by other impulses.

Distance is a real problem because our frontal lobes unfortunately don't understand the meaning of future rewards very well. This is why immediate desires usually have a stronger effect than those that are far away. With this in mind, we can try to add more value to the things that lie ahead of us by reflecting on the many benefits of completing them. You can also try implementing a punishment system to make immediate rewards less desirable.

The true desirability of a task similarly affects our tendency to procrastinate. If a task is especially undesirable, it will be difficult for us to distract ourselves from the impulses to do something else. Again, the best strategy for this dilemma is to identify the benefits of a future reward, giving it more power than competing immediate rewards.

Regardless of the strategy we choose to deal with procrastination, we must keep in mind that it is completely insurmountable. We postpone things for later, because. there is always something more attractive.