Activities for schizophrenia

Helping someone with schizophrenia | Your Health in Mind

Often people who are close to the person with schizophrenia are confused and unsure about the illness and their role in helping the person recover.

They may be afraid of accidentally doing something that could make things worse.

Is it an emergency?

Get help immediately if the person:

- has deliberately injured themselves

- talks about suicide or killing someone else (read our fact sheet on helping a suicidal person)

- is disorientated (does not know who they are, where there are, or what time of day it is)

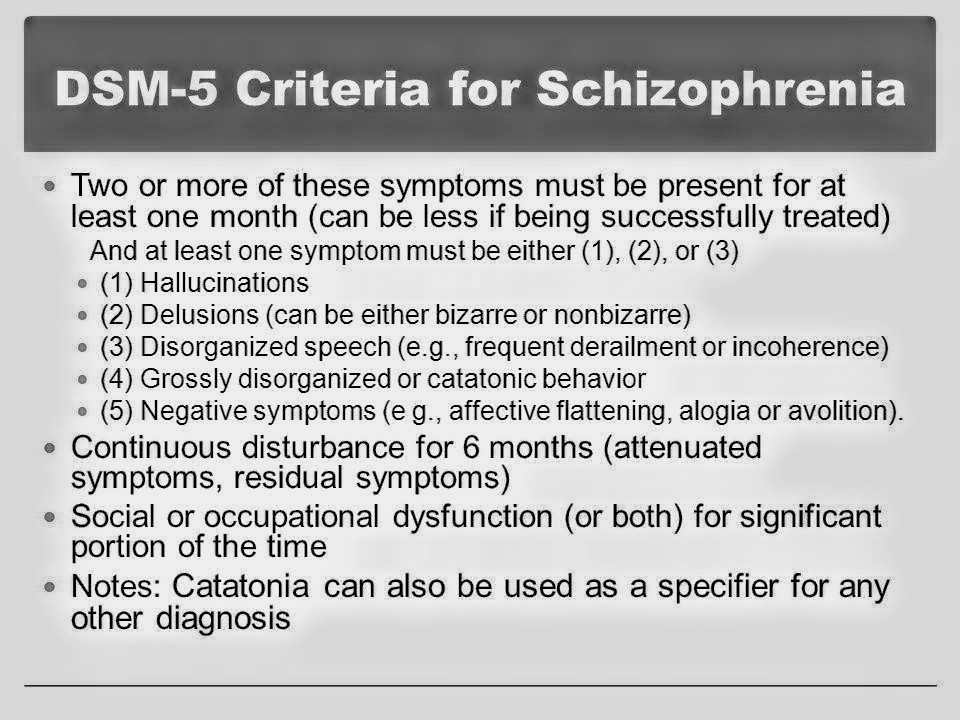

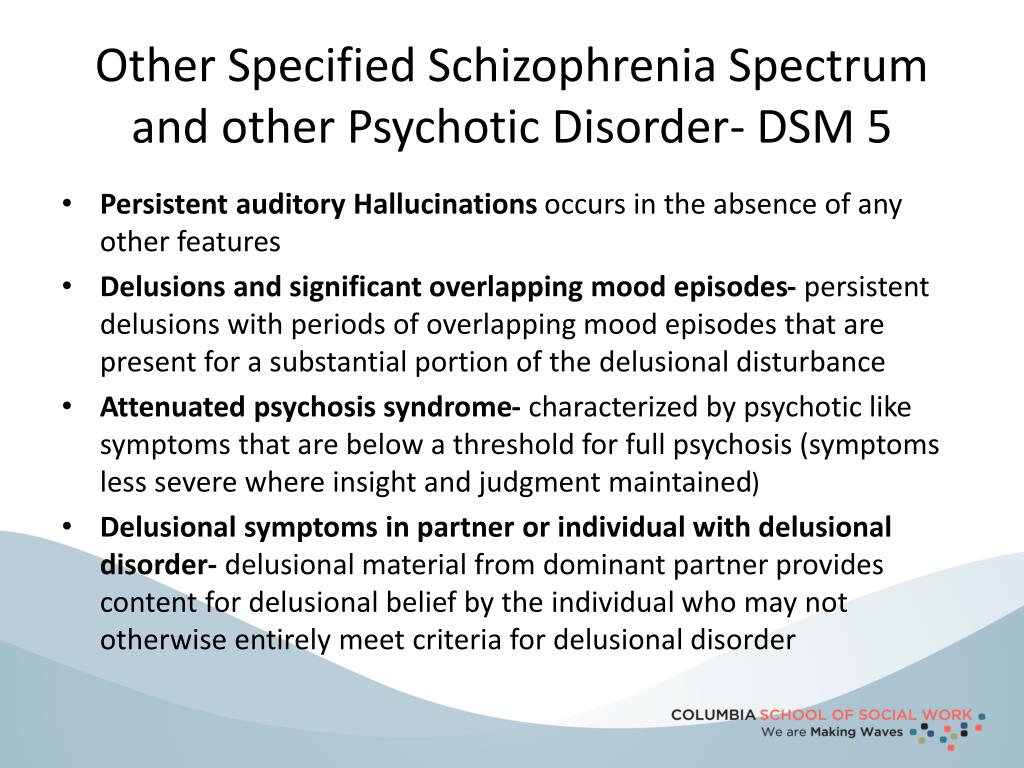

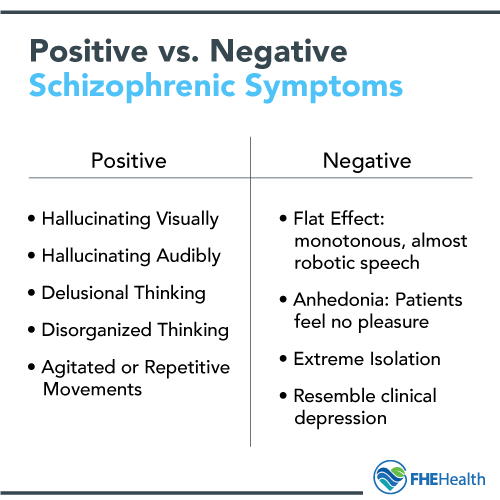

- has hallucinations (hearing or seeing things that are not real) or delusions (very strange beliefs, often based on the content of the hallucinations)

- is confused or not making sense.

If the person has any of these symptoms, call 000 in Australia or 111 in New Zealand, or visit the emergency department at your nearest hospital.

How to help someone with schizophrenia

If you are the family, friend or carer of someone with schizophrenia, these are some things you can do to help:

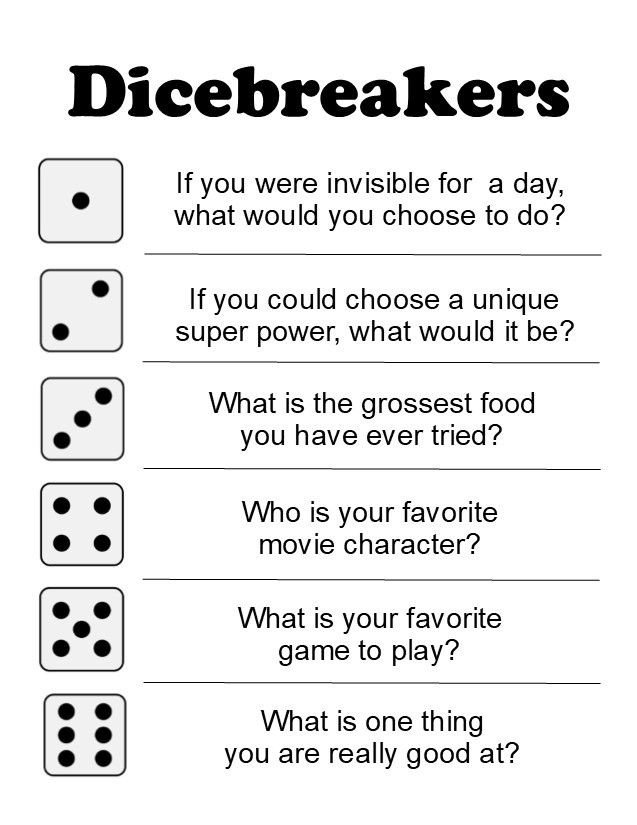

- Focus on the person’s strengths – the things they enjoy or are good at.

- Keep reminding them that they have a role as a member of their family and community.

- Consider doing a family psychoeducation program. This is a chance to learn about the illness, how to communicate better and how to deal with problems. Ask someone from the health-care team about psychoeducation programs near you.

- If you cannot join a psychoeducation program, consider making an appointment with a psychologist to learn more about schizophrenia and how you can help the person.

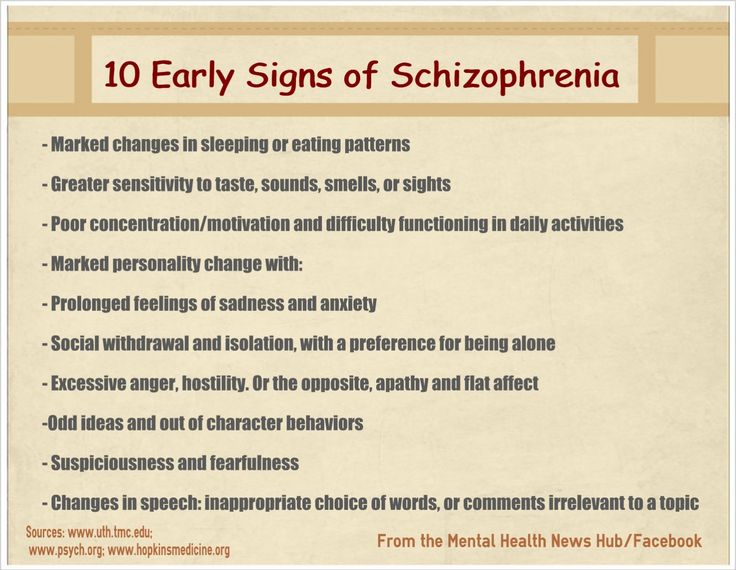

- Learn to recognise the early warning signs of a psychotic episode and have a plan for what to do.

- Learn motivational techniques to encourage the person to do things for themselves.

- Keep track of their health-care visits and help make sure they don’t miss them.

- Encourage them to choose someone (e.g. a friend, their partner or another family member) who will help and support them for as long as they need help. It is very important to have someone they trust who will keep trying to help them. Sometimes when a person with schizophrenia is unwell they may turn against people they are normally close to.

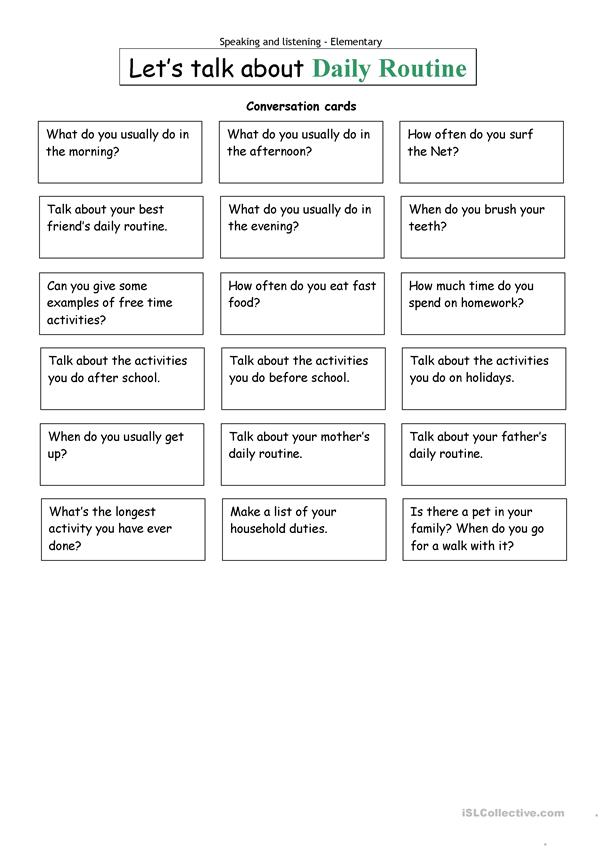

- Encourage them to participate in one-to-one activities, for example card games, chess, jigsaw puzzles, walking.

- Don’t leave them alone after a hospital visit. When someone with schizophrenia has been in hospital, the first week back at home can be very hard emotionally. During this time, people need lots of support to stay safe.

More about caring for someone with a mental illness

Things that do not help

Do not constantly remind them to take medication. Instead make a mutual plan to work together to overcome forgetfulness, and to set up a routine to follow.

What happens if the person doesn’t want help?

Generally an adult has the right to refuse treatment. But they can be treated without their consent to reduce the risk of serious harm to themselves or others, or if there is a risk that their health will seriously deteriorate.

But they can be treated without their consent to reduce the risk of serious harm to themselves or others, or if there is a risk that their health will seriously deteriorate.

Support and information for families

Mental Health Carers Australia

1300 554 660

SANE Australia

1800 187 263

Supporting Families in Mental Illness (New Zealand)

0800 732 825

8 Ways to Help a Loved One With Schizophrenia

When people with schizophrenia have supportive caregivers, they’re better equipped to achieve independence and live successful lives. But support may mean different things to different people living with schizophrenia.

For some, it may mean accepting a considerable amount of help from loved ones to finish school and find work. Others may need support in maintaining relationships and setting goals for themselves. And how each caregiver supports their loved one may differ from person to person.

“Supporting an individual’s autonomy is very important when it comes to engaging in care. Each person is different, and respecting their boundaries and unique needs is crucial,” says Aubrey Moe, PhD, a psychologist in the department of psychiatry and behavioral health at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus.

Each person is different, and respecting their boundaries and unique needs is crucial,” says Aubrey Moe, PhD, a psychologist in the department of psychiatry and behavioral health at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus.

Here are eight ways you can support a loved one with schizophrenia.

RELATED: Schizophrenia: Popular Myths, Real Facts

1. Encourage Them to Schedule Regular Doctor's AppointmentsThere are several reasons someone with schizophrenia may not attend doctor's appointments. Some may not believe that they have an illness or need medical help, while others may realize the need for help but can't get themselves to make the appointments. And others may be busy and have a hard time attending regular appointments.

Keeping doctor's appointments is critical, because the sooner the person is treated, the better the outcome, says Krista Baker, a licensed clinical professional counselor and director of operations of the community psychiatry program at the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore.

Arguing with your loved one or attempting to convince them to view their symptoms a certain way won’t be effective. Instead, remind your loved one how treatment can help them reach whatever goals they may have for their lives, says Baker.

“There needs to be a sense of motivation on the person’s part,” Baker says.

Dr. Moe adds that some people with schizophrenia may find direct, repeated reminders about doctor’s appointments or medications from family members to be helpful. But others may find this type of reminder to be intrusive or unwanted.

Other ways to support a loved one with schizophrenia include suggesting they use calendar reminders in their smartphones or online healthcare portals to keep track of doctor's appointments and prescriptions, Moe says. This may allow them to feel more empowered and in control of their healthcare, she says.

Some people may not want their loved one involved in their care, Moe advises. “Individuals with schizophrenia may also prefer more privacy when it comes to sharing their healthcare-related information with family or friends, and may find it preferable to plan reminders or care with their therapists or other members of their healthcare teams,” says Moe.

People with schizophrenia may not always notice that their medication is improving their mental health or thought processes, but they often notice the side effects, says Baker. These can include tiredness, dizziness, muscle cramps, and weight gain, and may cause people to stop taking their medications.

Finances, stigma, cooccurring substance use disorders, and cultural influences can also play a role in whether a person takes their medication consistently, according to a review article first published in April 2016 in The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine.

When your loved one has been using medication consistently, it can be helpful to point out positive changes that align with your loved one's goals — for example, showing up to work more often or having a better social life.

Being understanding of your loved one’s concerns about medication side effects is also essential. It’s helpful to show understanding that although the medication may have benefits, there may be unwanted side effects, too, and to encourage your loved one to discuss these concerns with their doctor.

It’s helpful to show understanding that although the medication may have benefits, there may be unwanted side effects, too, and to encourage your loved one to discuss these concerns with their doctor.

Working with a doctor to find a medication and dose that keeps schizophrenia symptoms under control with the fewest side effects can help your loved one stick to their treatment plan, Baker says. Medication calendars and weekly pillboxes may also help a person with schizophrenia remember to take medications regularly.

RELATED: A Therapist Speaks: Are Lower Doses of Antipsychotic Meds Better in the Long Run?

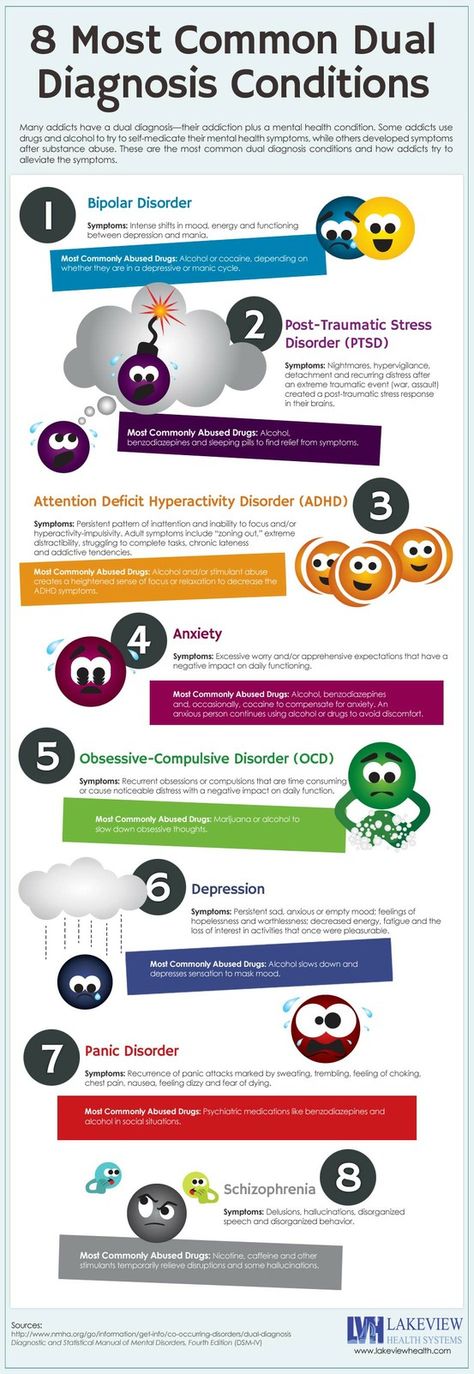

3. Help Them Avoid Alcohol and Illicit DrugsWhen people with schizophrenia experience symptoms, such as hearing voices, some may seek relief by using alcohol and drugs, which work quickly to help them feel different. Caregivers can help prevent substance abuse by clearing the house of drugs and alcohol and by talking to their loved one about how abstaining from drugs and alcohol can help them maintain their overall health and achieve their goals.

The best approach may be to help your loved one consider the negative impact of substance use on their symptoms and quality of life, with the goal of facilitating a shift toward healthier behaviors, suggests Moe.

When possible, it’s helpful to work with your loved one to make a plan for coping with negative symptoms when they’re feeling well and not experiencing a crisis, adds Moe. Therapy can also be helpful for learning new coping skills and strategies, and empowering people with schizophrenia become less reliant on substance use to cope, Moe says.

4. Help Them Reduce Their StressStress can make it hard for a person with schizophrenia to function and may trigger a relapse. For someone living with schizophrenia, a loud, chaotic household and other sources of stress might intensify delusions, hallucinations, and other symptoms. “Everyone wants to be treated respectfully,” says Baker, “and we all do better in calm, inviting environments.”

However, keeping quiet to avoid upsetting the person can add to the stress of other family members. Use quiet but firm voices and create a calm and safe home environment, Baker advises.

Use quiet but firm voices and create a calm and safe home environment, Baker advises.

And don’t forget to include your loved one with schizophrenia in planning a supportive and safe environment for them, as each person experiences their symptoms and deals with their stressors differently, says Moe.

5. Help Them Maintain a Healthy WeightMedications to treat schizophrenia can cause weight gain, which can increase the risk of obesity-related health conditions. People living with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders have high rates of physical health problems and cardiometabolic risk factors like high blood pressure and high cholesterol, says Moe.

Eating a nutritious diet is the best way to maintain a healthy weight, but not everyone can plan their meals in advance. Baker says that caregivers can help by accompanying the person with schizophrenia to the grocery store and talking to them about healthy foods. A registered dietitian nutritionist can also help teach your loved one about making nutritious choices and educate them about meal planning.

Regular exercise is another way to promote weight maintenance and general well-being. Engaging in aerobic exercises like walking or other activities like stretching or yoga can be beneficial for weight management among people with schizophrenia, says Moe. And while not a replacement for appropriate psychiatric care, exercise is a noninvasive and low-cost approach to improving both mental and physical health, Moe says.

Your loved one with schizophrenia should consult with their healthcare providers to determine the best approach for integrating exercise into their wellness plan, Moe adds.

RELATED: Newly Approved Antipsychotic for Schizophrenia and Bipolar I Disorder Lessens Weight Gain, Studies Show

6. Try to Limit Power StrugglesSchizophrenia usually sets in during late adolescence, a time when young people tend to want independence and freedom. But whatever the age of your loved one, people with schizophrenia don't want to be micromanaged and hounded about everything from taking medications to cleaning their rooms, Baker says.

Rather than using phrases like, "You need to go out and get a job," Baker advises caregivers to focus on the person's own goals and what needs to be done to achieve them. "We want to think about individuals moving down the same path they would have chosen if they had never been diagnosed," she says.

Family therapists can often help families avoid power struggles and work on dialogue that benefits a person with schizophrenia, Baker adds.

7. Help Them Maintain Their Social SkillsPeople with schizophrenia tend to have a reversed sleep cycle, staying awake late into the night and then waking up in the afternoon, Baker says. Sleeping late can disrupt routines and encourage isolation. Other symptoms of schizophrenia, such as social withdrawal and poor interpersonal skills, can also contribute to this isolation.

Caregivers can help their loved one maintain social skills by adhering to routines, including planned social activities and outings. One could also take an active role by getting the person into a community program, planning an outing with them once a week, or helping them keep in contact with friends, Baker suggests. Whatever activity you choose, it should preferably be something your loved one is interested in doing and possibly helped plan.

Whatever activity you choose, it should preferably be something your loved one is interested in doing and possibly helped plan.

RELATED: Keeping Your Relationship Strong After a Schizophrenia Diagnosis

8. Know That You May Have to Intervene, if NecessaryPeople with schizophrenia who refuse treatment or help of any sort may need to be hospitalized. In some cases, families may need to call the police for help if their loved one becomes a danger to themselves or others. Once treatment starts and symptoms subside, families can redirect their loved one back toward their life goals.

“Treatment works, but it doesn’t work overnight,” says Baker. “It’s a process.”

If you have specific concerns for your loved one’s safety, working with their healthcare providers to create coping and safety plans is an important way to prepare for difficult symptoms when they arise, says Moe.

Additional reporting by Michelle Pugle.

Schizophrenia: Popular Myths, Real Facts

By5 Beneficial Foods for People With Schizophrenia

ByWhat Life’s Really Like With Schizophrenia: A #NoFilter Memoir

BySchizophrenia and Pregnancy: What to Know

BySchizophrenia Treatment

ByWhat Is Schizophrenia? Symptoms, Causes, Diagnosis, and Treatment

ByWhat Is Schizoaffective Disorder?

BySchizophrenia Signs and Symptoms

ByA Therapist Speaks: Are Lower Doses of Antipsychotic Meds Better in the Long Run?

ByShowing the Truth About Schizophrenia

BySchizophrenia

Schizophrenia- Healthcare issues »

- A

- B

- B

- G

- D

- E

- and

- 9000 About

- P

- P

- With

- T

- U

- F

- x

- S

- B

- E

- S

- I

005

- Popular Topics

- Air pollution

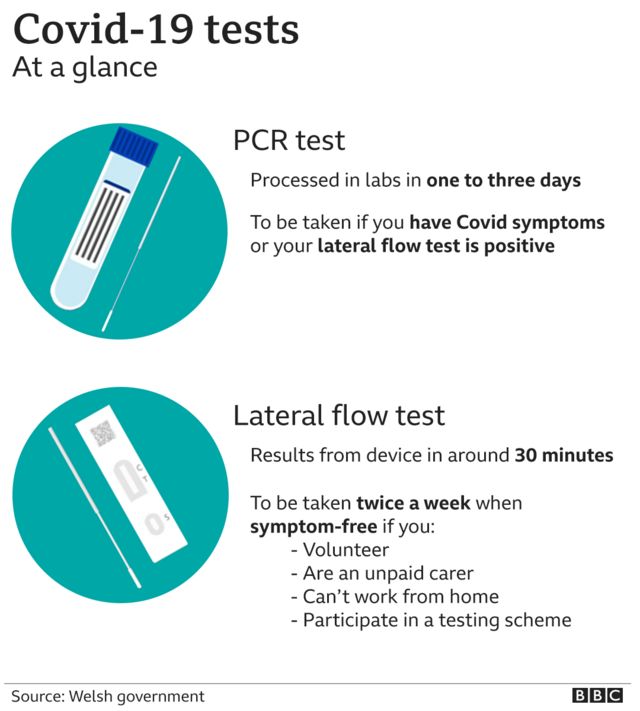

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Hepatitis

- Data and statistics »

- News bulletin

- The facts are clear

- Publications

- Find country »

- A

- B

- C

- g

- D

- E

- and

- th

- K

- L

- 9000 N

- 9000

- in

- f

- x

- C

- hours

- Sh

- Sh.

- 9000 WHO in countries »

- Reporting

- Regions »

- Africa

- America

- Southeast Asia

- Europe

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Western Pacific

- Media Center

- Press releases

- Statements

- Media messages

- Comments

- Reporting

- Online Q&A

- Events

- Photo reports

- case studies

- Questions and answers

- Speeches

- Update

- Emergencies "

- News "

- Disease Outbreak News

- WHO data »

- Dashboards »

- COVID-19 Monitoring Dashboard

- Basic moments "

- About WHO »

- CEO

- About WHO

- WHO activities

- Where does WHO work?

- Governing Bodies »

- World Health Assembly

- Executive committee

- Main page/

- Media Center /

- Newsletters/

- Read more/

- Schizophrenia

Key Facts

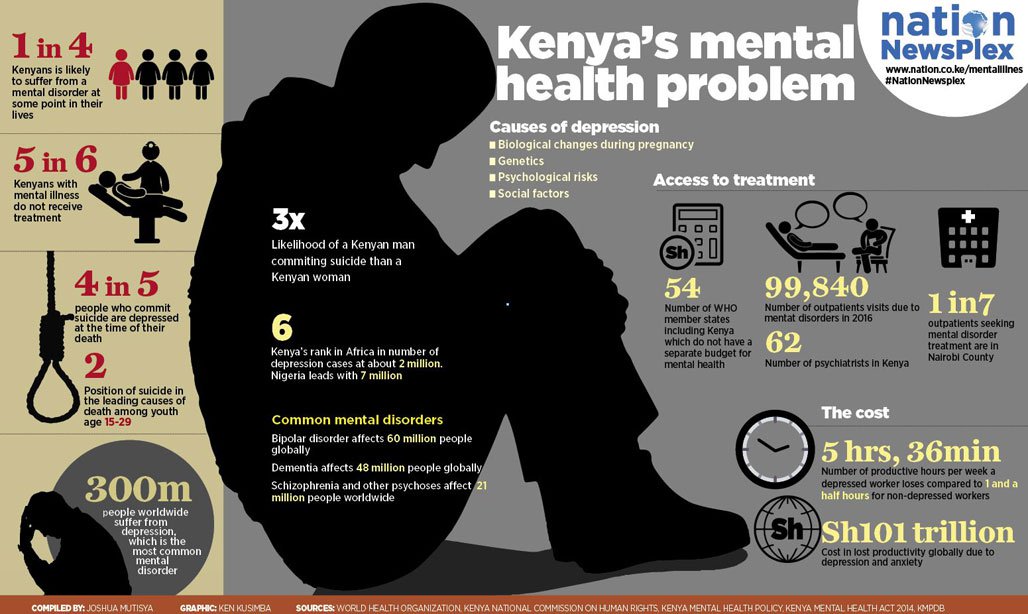

- Schizophrenia is a severe mental disorder that affects approximately 24 million people, or 1 in 300 people worldwide.

- Schizophrenia causes psychosis, is associated with severe disability, and can negatively affect all areas of life, including personal, family, social, academic and work life.

- People with schizophrenia are often subject to stigma, discrimination and human rights violations.

- Worldwide, more than two thirds of people with psychosis do not receive specialized mental health care.

- There are a number of effective options for helping patients with schizophrenia, which can lead to a complete recovery of at least one in three patients.

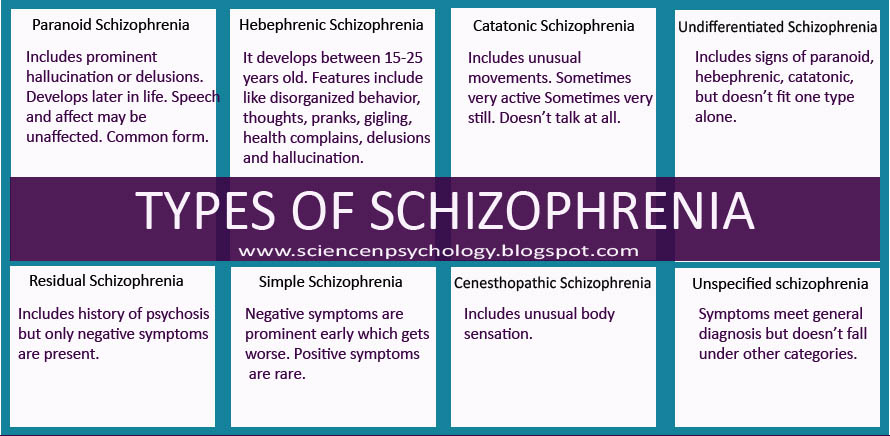

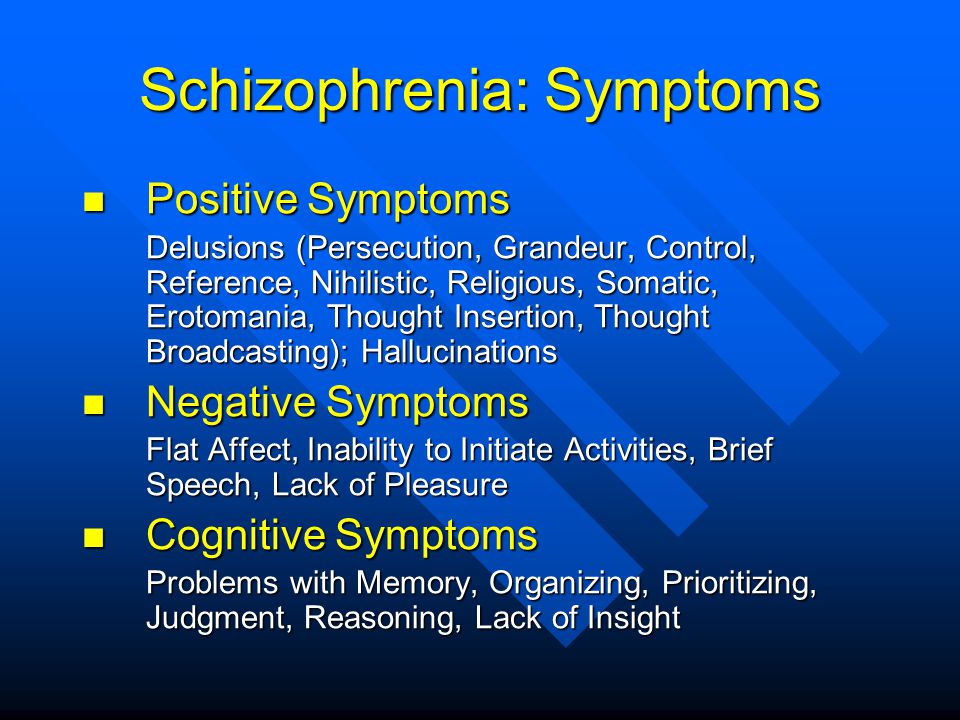

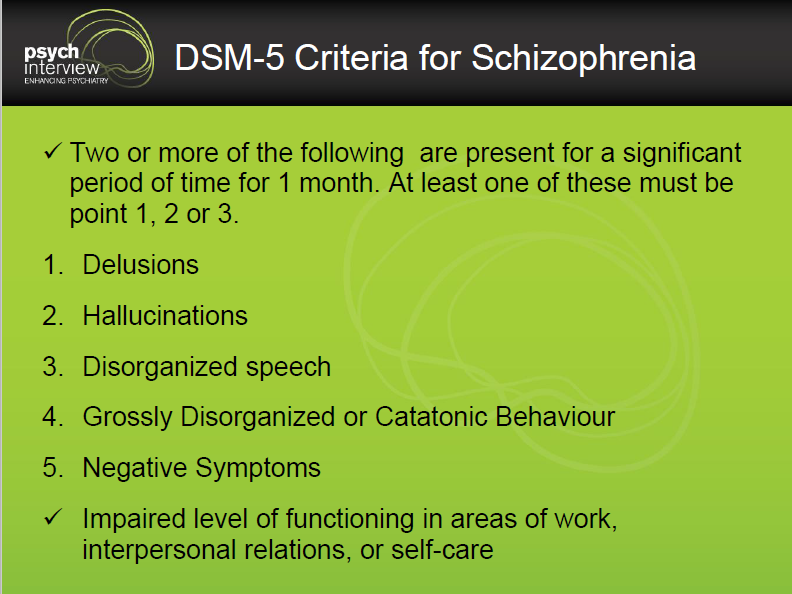

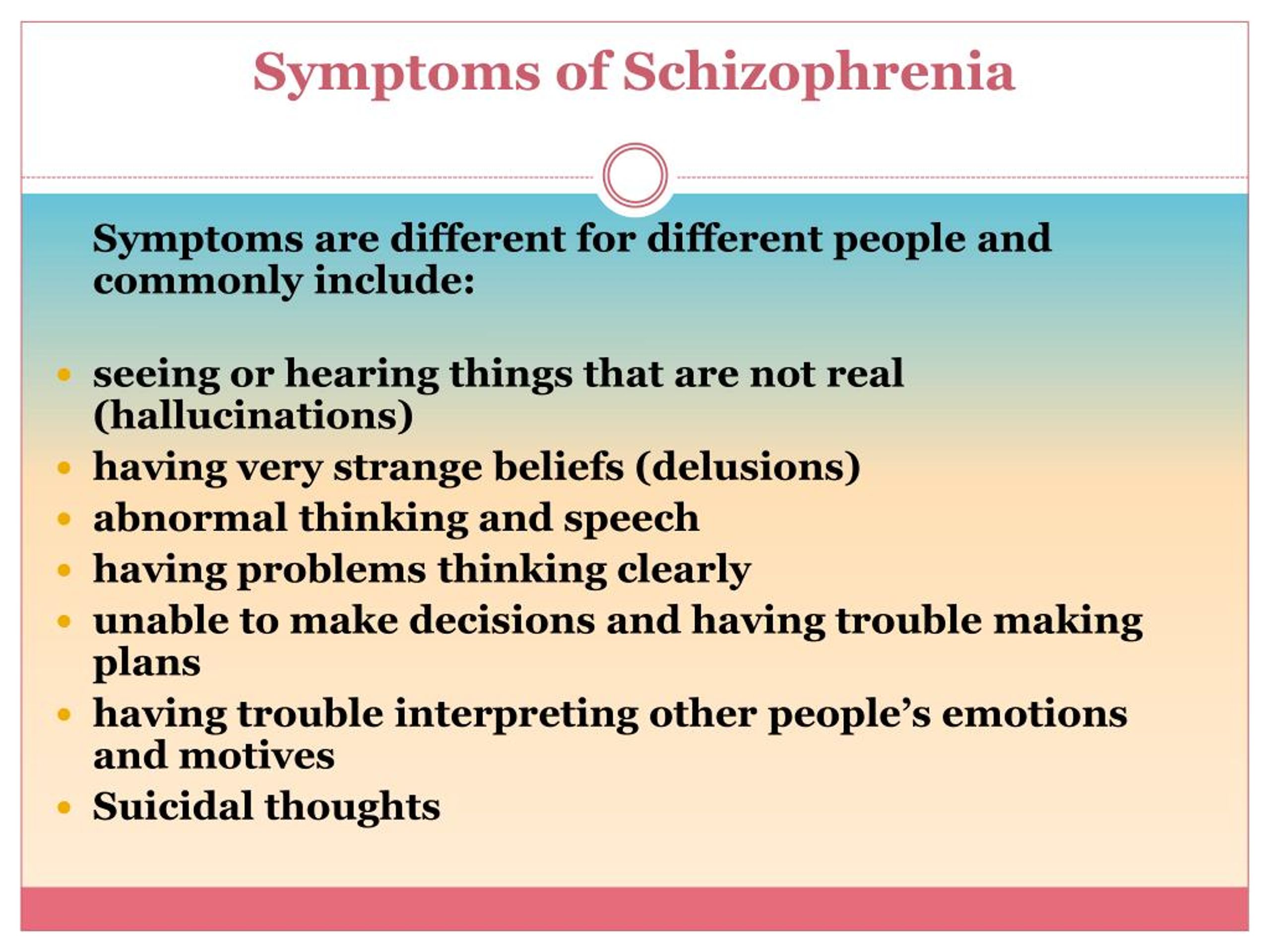

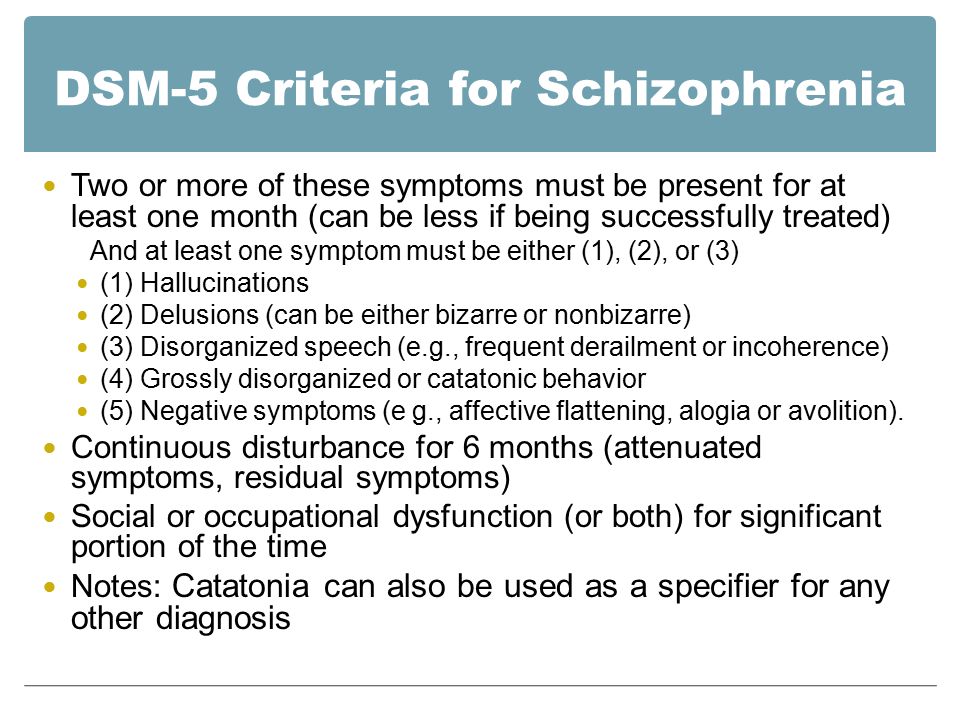

Symptoms

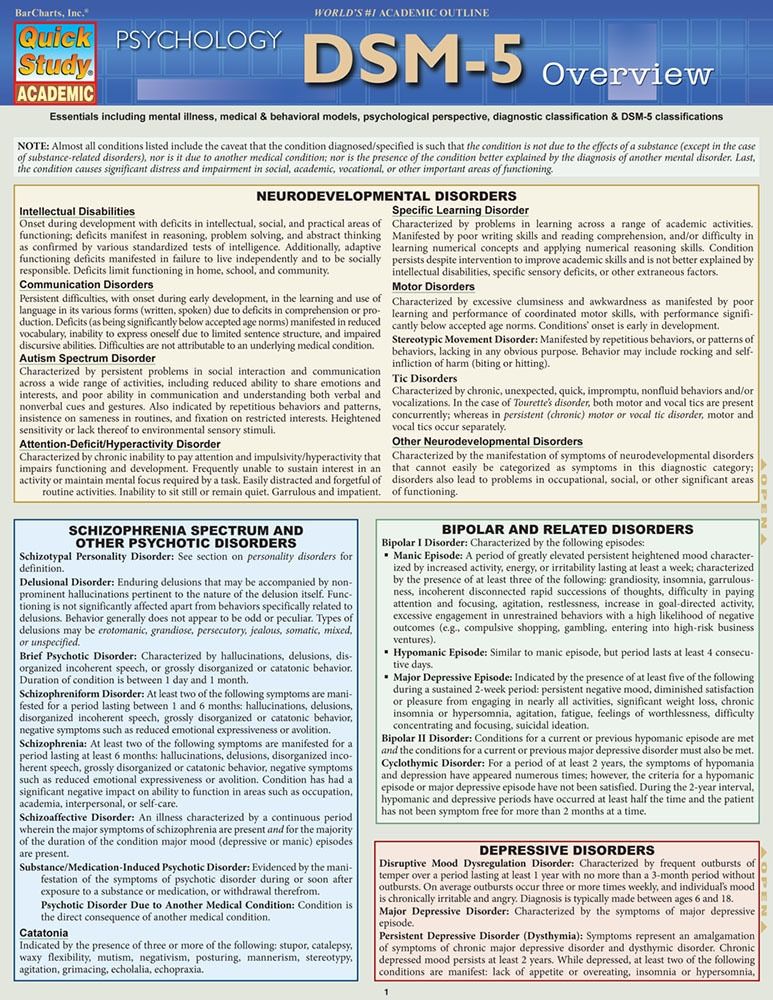

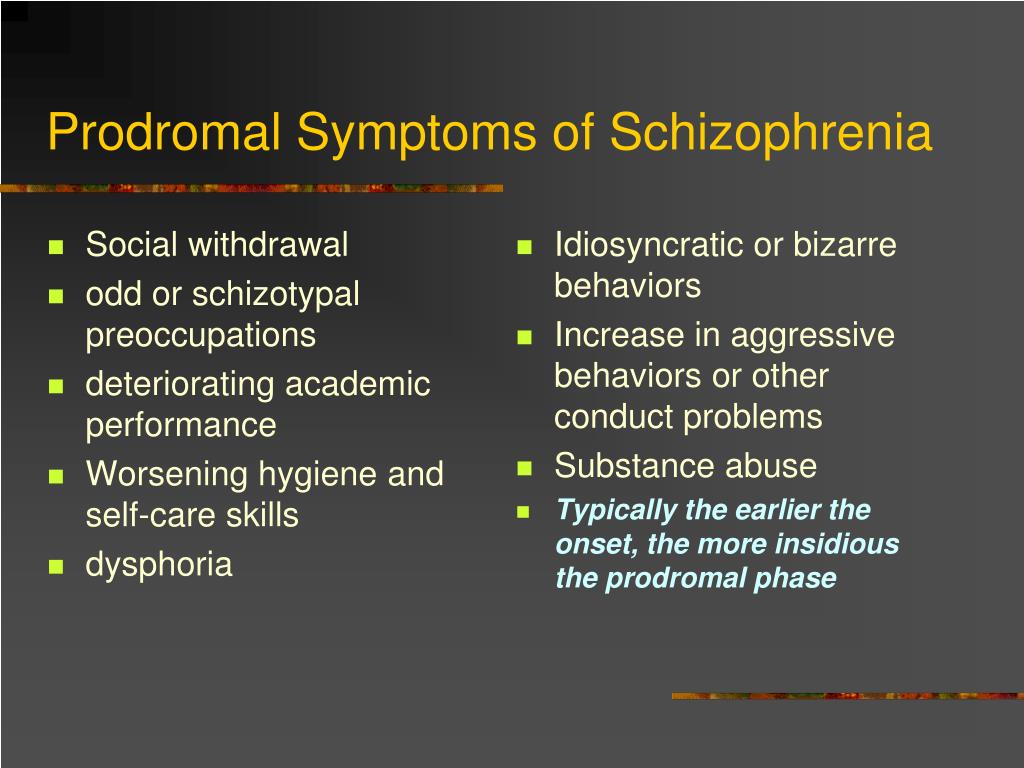

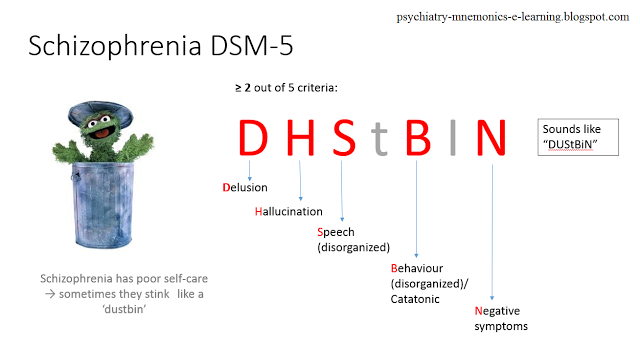

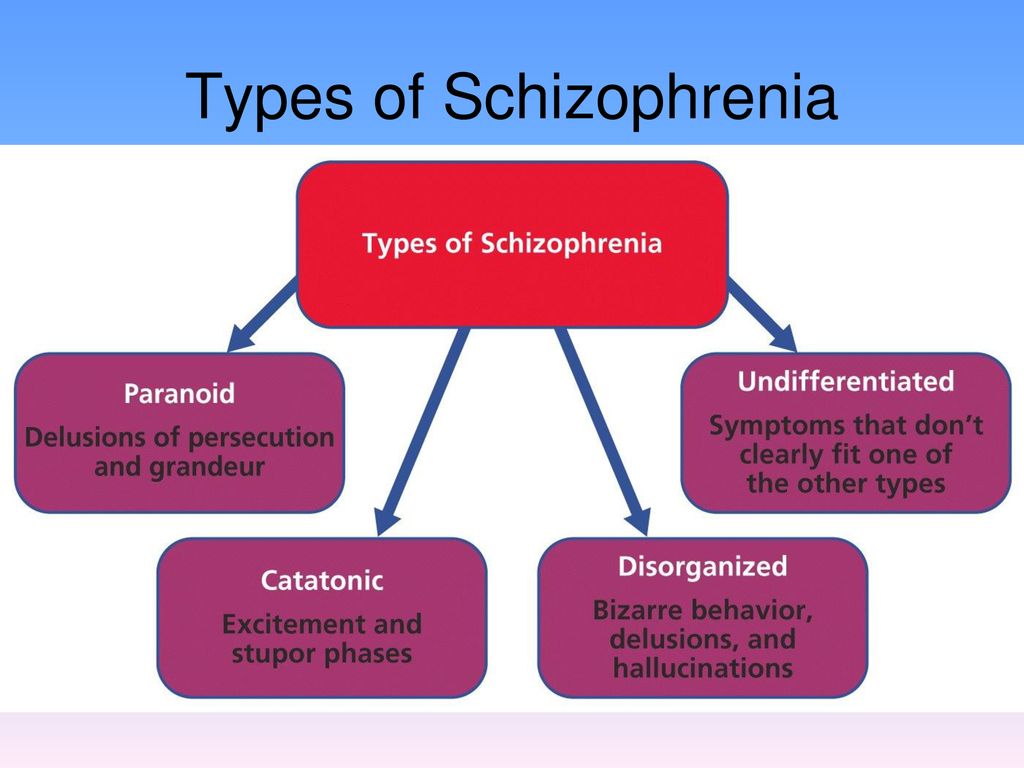

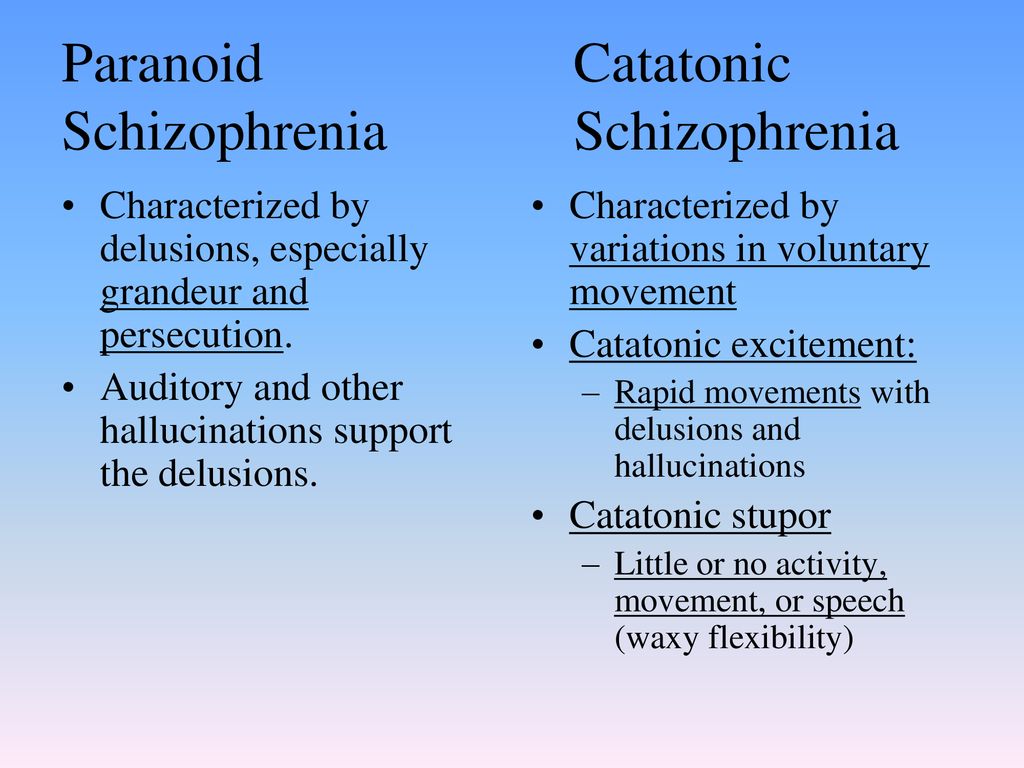

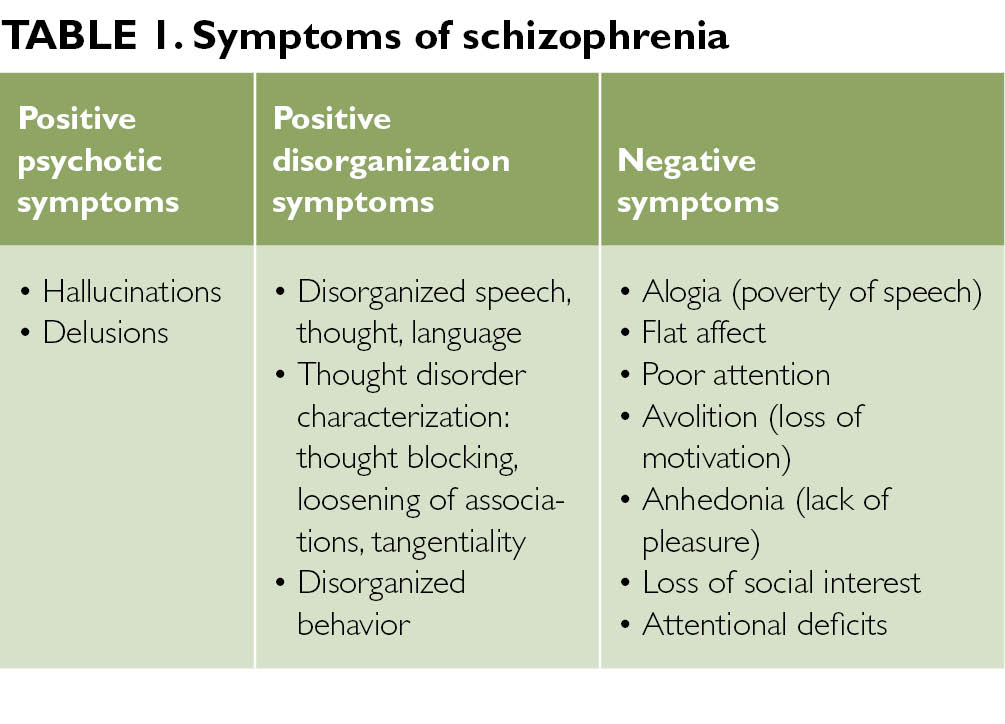

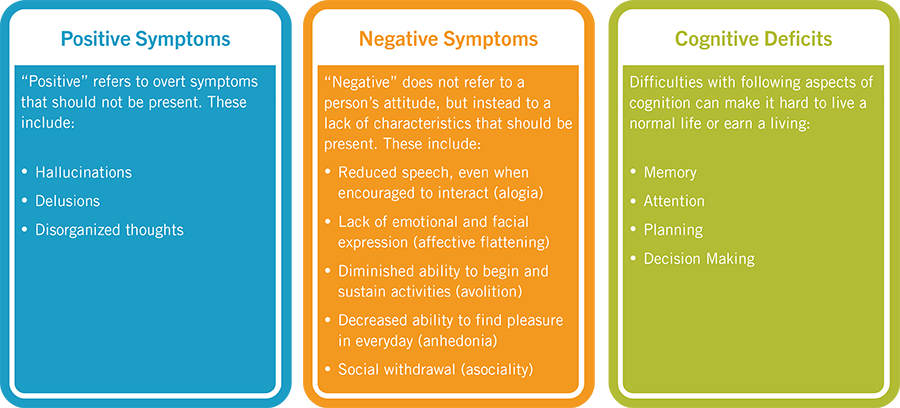

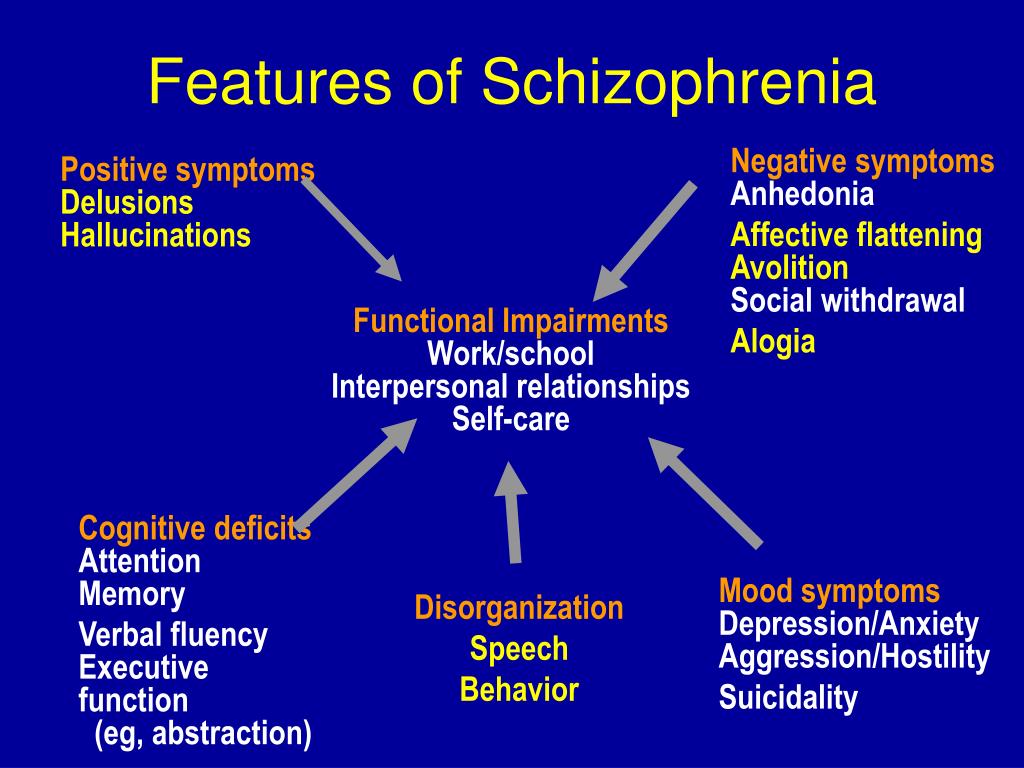

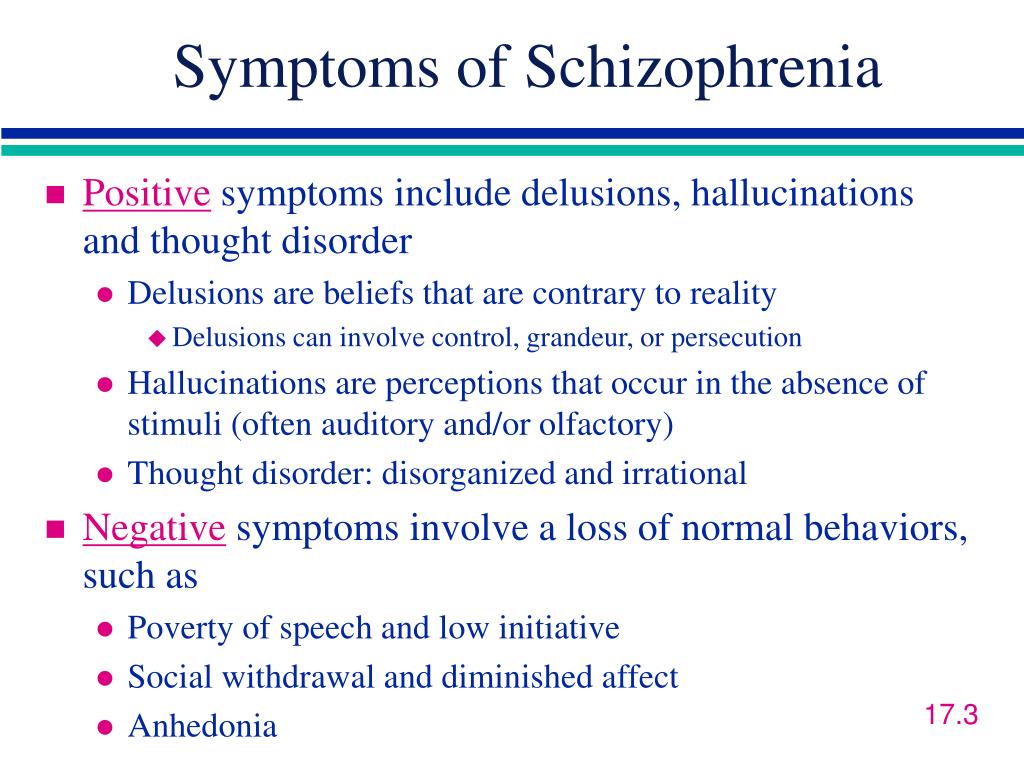

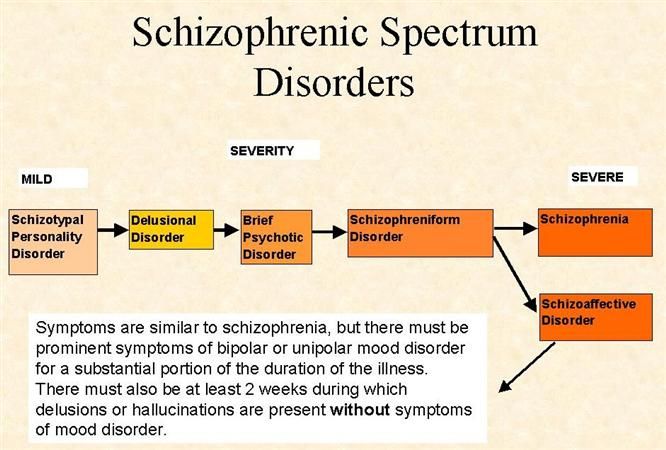

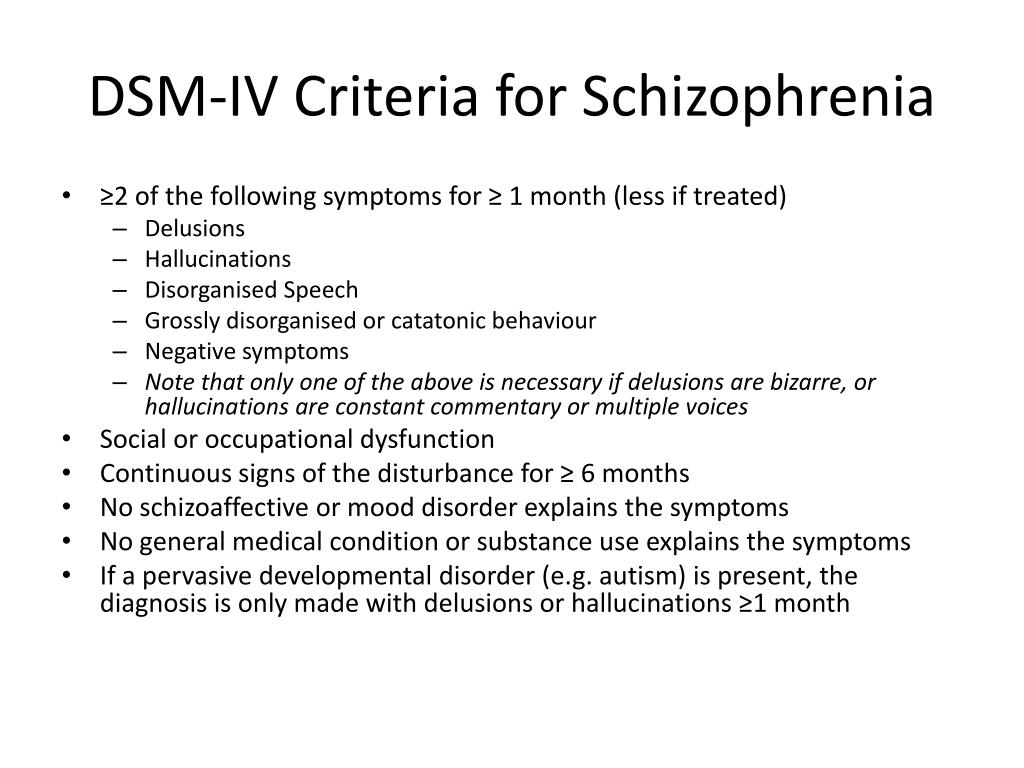

Schizophrenia is characterized by significant disturbances in the perception of reality and behavioral changes, such as:

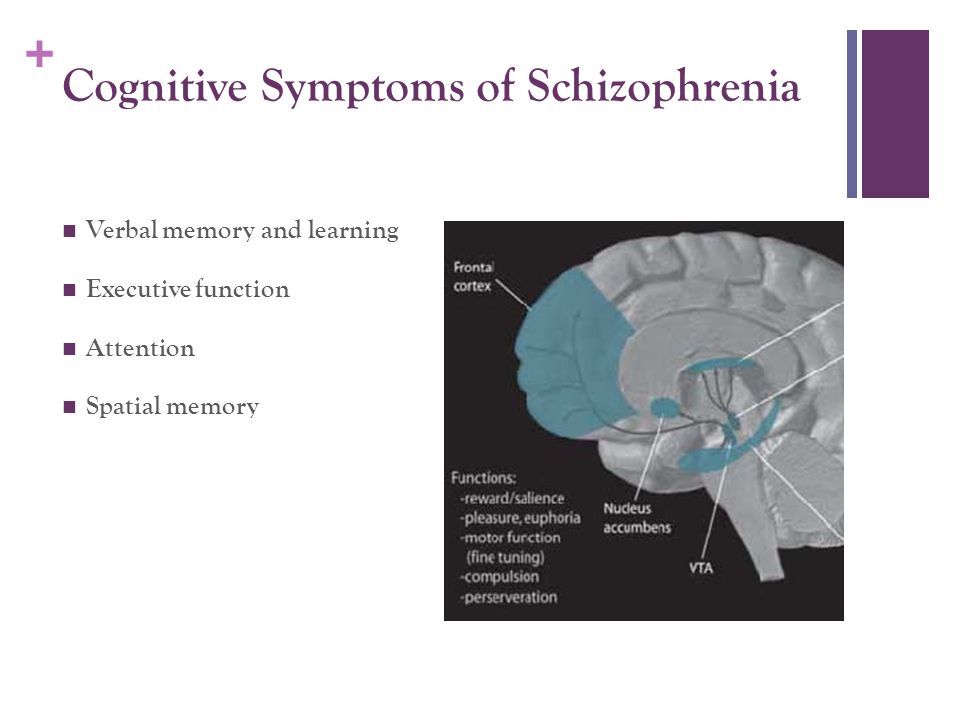

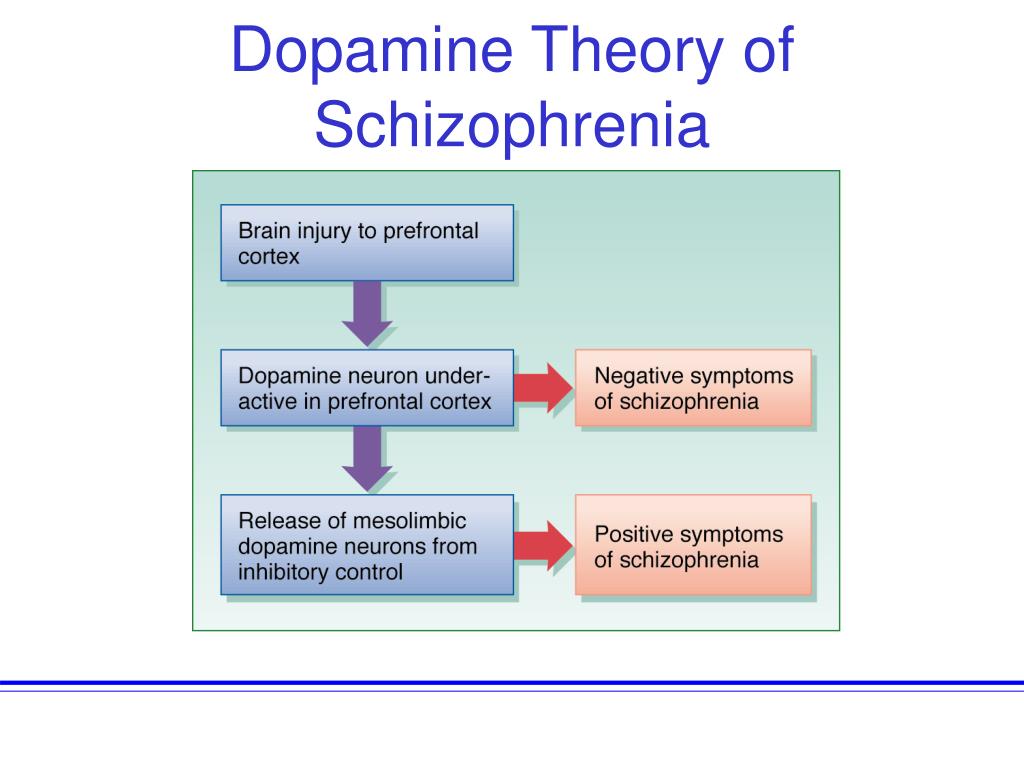

People with schizophrenia often also experience persistent cognitive or thinking problems that affect memory, attention, or problem-solving skills.

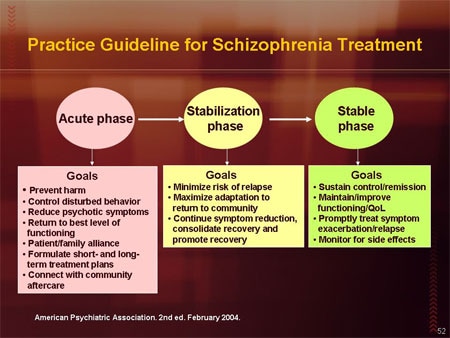

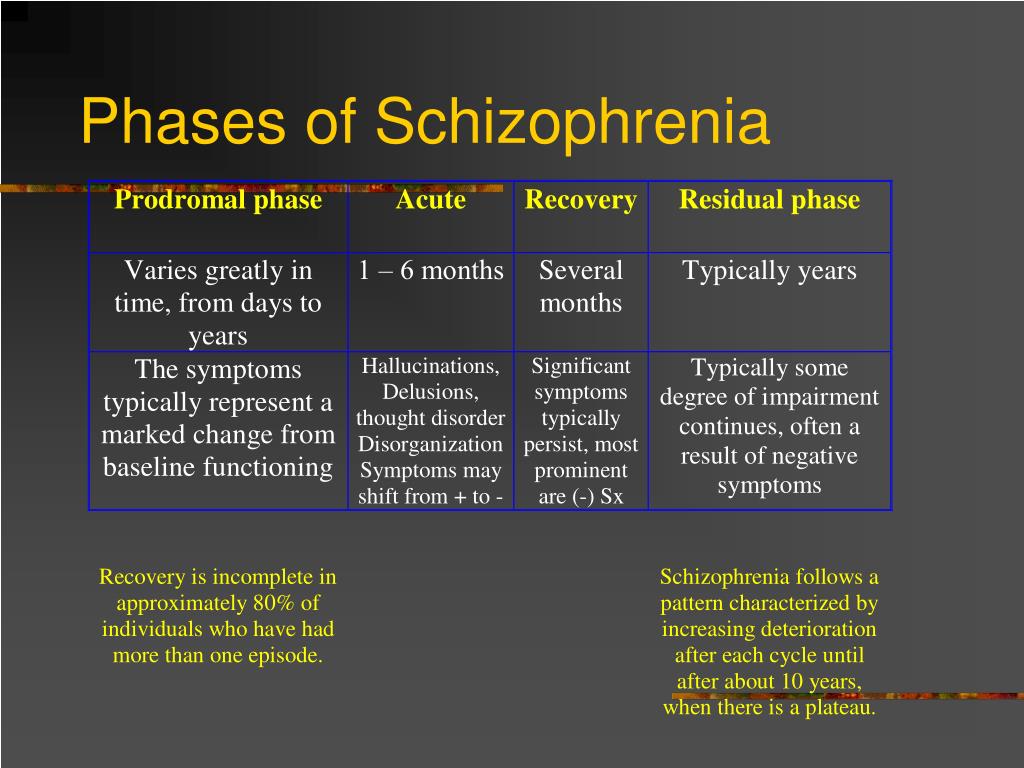

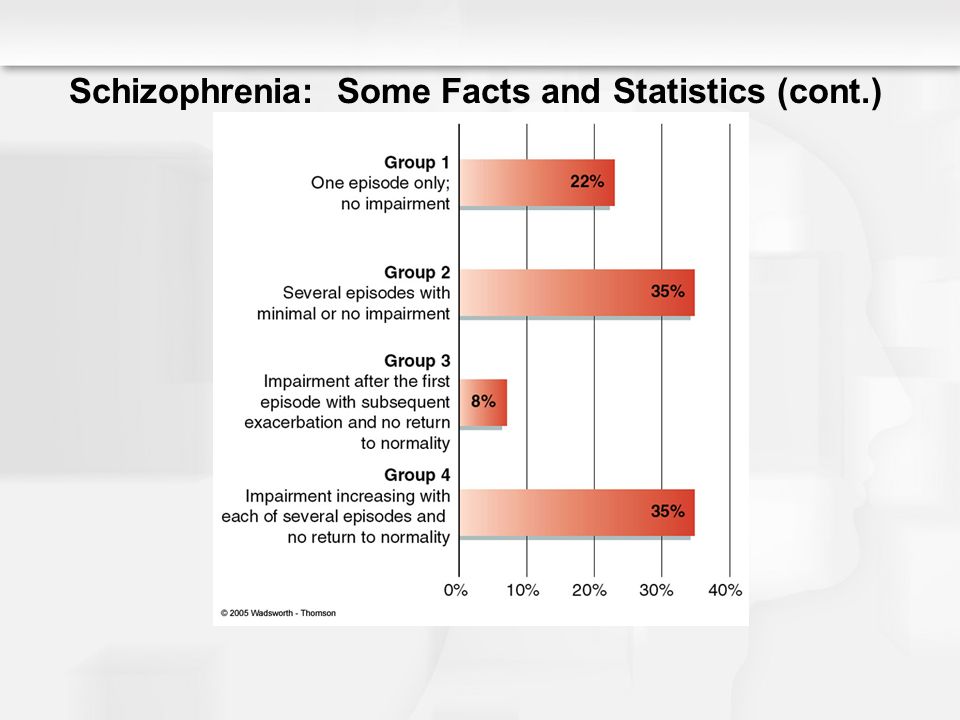

At least one third of patients with schizophrenia experience complete remission of symptoms (1). In some, periods of remission and exacerbation of symptoms follow each other throughout life, in others there is a gradual increase in symptoms.

Scope and impact

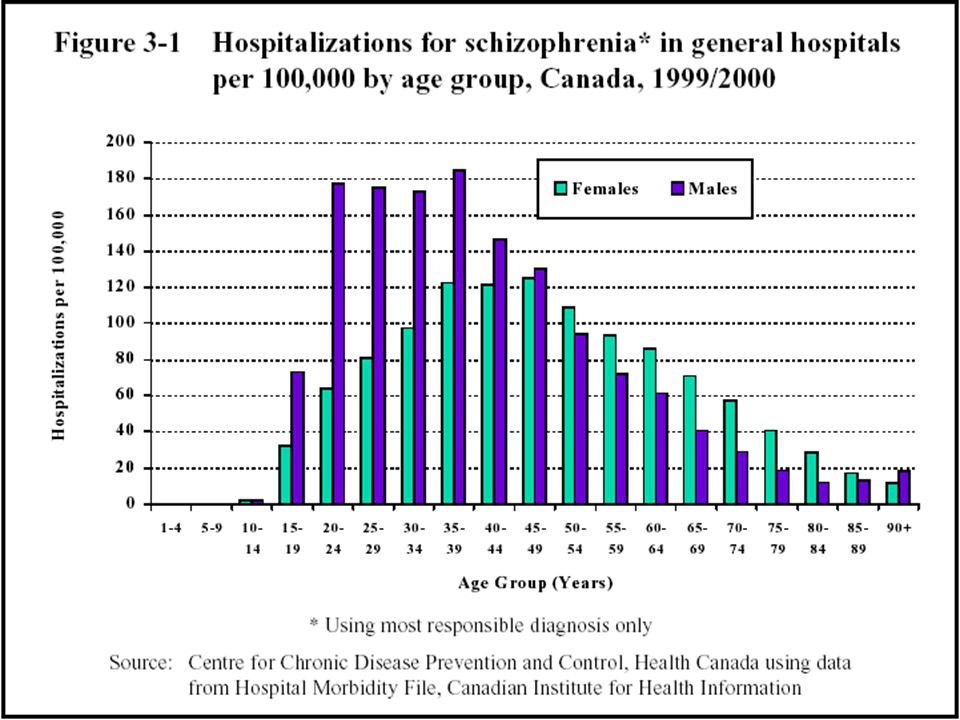

Schizophrenia affects approximately 24 million people, or 1 in 300 people (0.32%) worldwide. Among adults, the rate is 1 in 222 (0.45%) (2). Schizophrenia is less common than many other mental disorders. Onset is most common in late adolescence and between the ages of 20 and 30; while women tend to have a later onset of the disease.

Schizophrenia is often accompanied by significant stress and difficulties in personal relationships, family life, social contacts, studies, work or other important areas of life.

People with schizophrenia are 2-3 times more likely to die early than the population average (2). It is often associated with physical illnesses such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic disease, and infectious disease.

It is often associated with physical illnesses such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic disease, and infectious disease.

Patients with schizophrenia often become the object of human rights violations both within the walls of psychiatric institutions and in everyday life. Significant stigmatization of people with this disease is a widespread phenomenon that leads to their social isolation and has a negative impact on their relationships with others, including family and friends. This creates grounds for discrimination, which in turn limits access to health services in general, education, housing and employment.

Humanitarian emergencies and health crises can cause intense stress and fear, disrupt social support mechanisms, lead to isolation and disruption of health services and supply of medicines. All these shocks can have a negative impact on the lives of people with schizophrenia, in particular by exacerbating existing symptoms of the disease. People with schizophrenia are more vulnerable during emergencies to various human rights violations and, in particular, face neglect, abandonment, homelessness, abuse and social exclusion.

Causes of schizophrenia

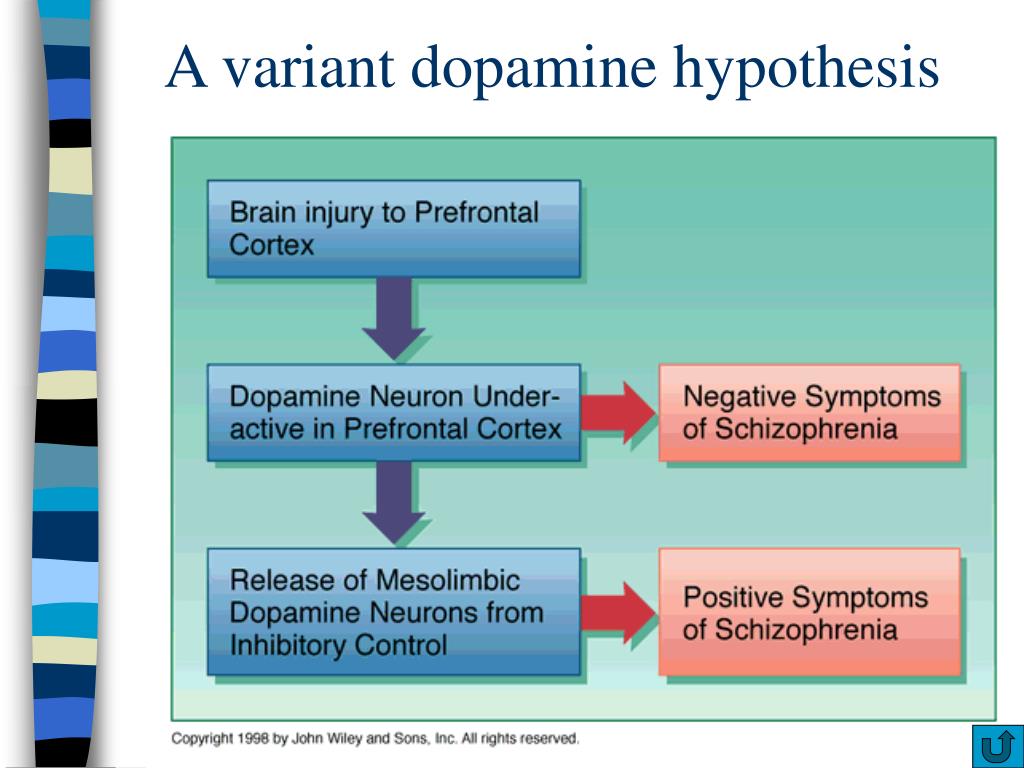

Science has not established any single cause of the disease. It is believed that schizophrenia may be the result of the interaction of a number of genetic and environmental factors. Psychosocial factors may also influence the onset and course of schizophrenia. In particular, heavy marijuana abuse is associated with an increased risk of this mental disorder.

Assistance services

At present, the vast majority of people with schizophrenia do not receive mental health care worldwide. Approximately 50% of patients in psychiatric hospitals are diagnosed with schizophrenia (4). Only 31.3% of people with psychosis get specialized mental health care (5). Much of the resources allocated to mental health services are inefficiently spent on the care of patients admitted to psychiatric hospitals.

Available scientific evidence clearly indicates that hospitalization in psychiatric hospitals is not an effective way of providing care for mental disorders and is regularly associated with the violation of the fundamental rights of patients with schizophrenia. Therefore, it is necessary to ensure the expansion and acceleration of work on the transfer of functions in the field of mental health care from psychiatric institutions to the level of local communities. Such work should begin with the organization of the provision a wide range of quality community-based mental health services. Options for community-based mental health care include integrating this type of care into primary health care and hospital care. general care, setting up community mental health centres, outpatient care centres, social housing with nursing care and social home care services. Involvement in the care process is important the patient with schizophrenia, his family members and members of local communities.

Therefore, it is necessary to ensure the expansion and acceleration of work on the transfer of functions in the field of mental health care from psychiatric institutions to the level of local communities. Such work should begin with the organization of the provision a wide range of quality community-based mental health services. Options for community-based mental health care include integrating this type of care into primary health care and hospital care. general care, setting up community mental health centres, outpatient care centres, social housing with nursing care and social home care services. Involvement in the care process is important the patient with schizophrenia, his family members and members of local communities.

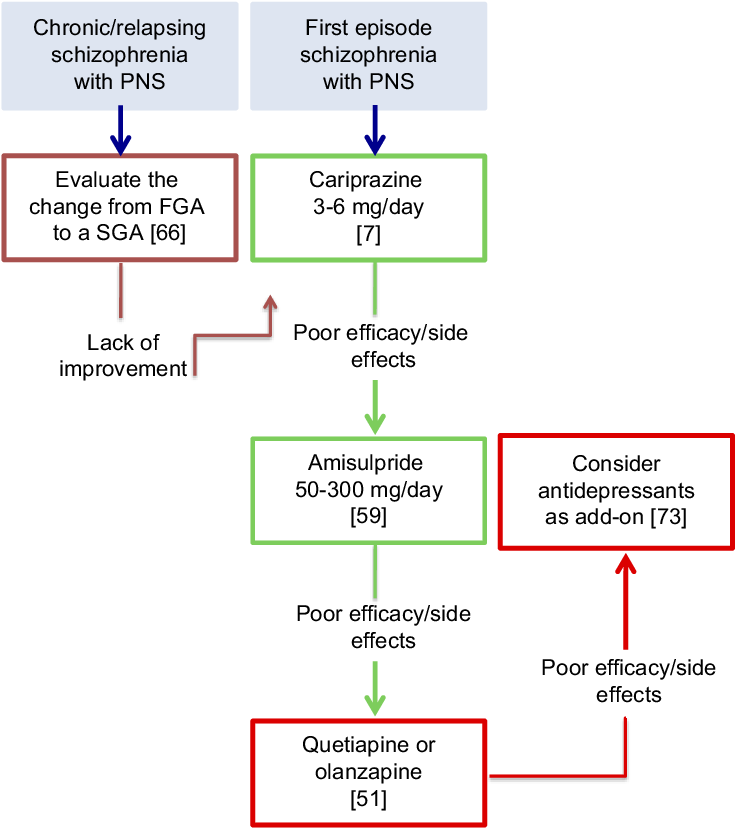

Schizophrenia management and care

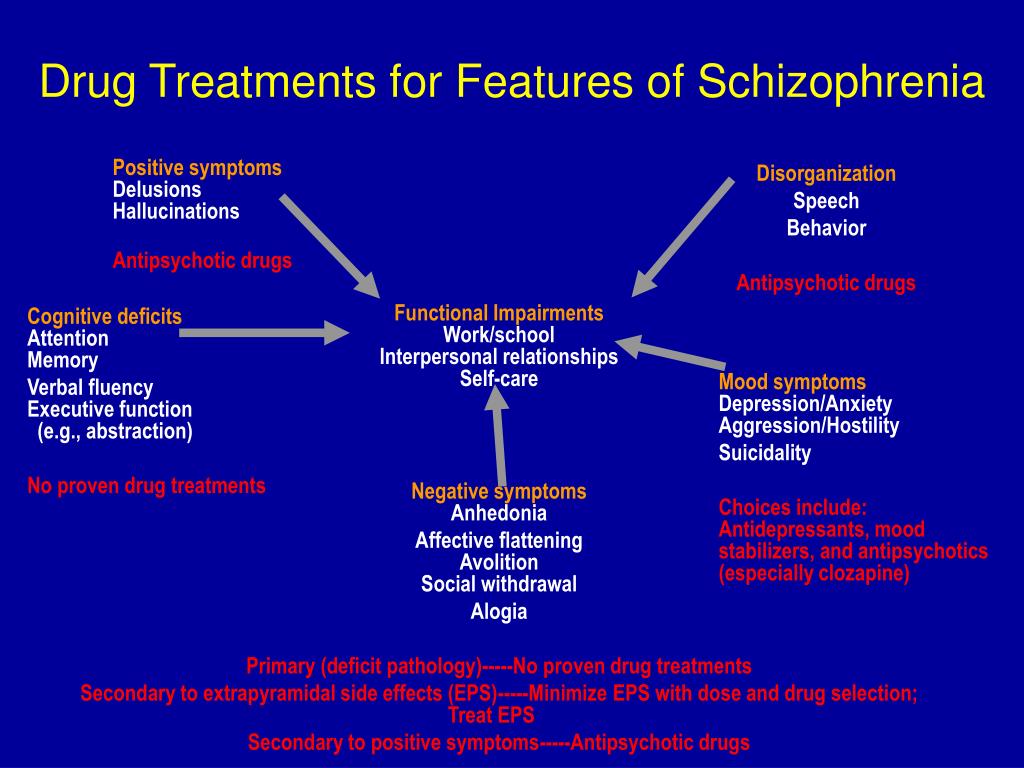

There are a number of effective approaches to treating people with schizophrenia, including medication, psychoeducation, family therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and psychosocial rehabilitation (eg, life skills education). The most important interventions for helping people with schizophrenia are assisted living, special housing and employment assistance. It is extremely important for people with schizophrenia and their families and/or caregivers to a recovery-centered approach that empowers people to participate in decisions about their care.

The most important interventions for helping people with schizophrenia are assisted living, special housing and employment assistance. It is extremely important for people with schizophrenia and their families and/or caregivers to a recovery-centered approach that empowers people to participate in decisions about their care.

WHO action

steps are in place to ensure that appropriate services are provided to people with mental disorders, including schizophrenia. One of the key recommendations The action plan is to transfer the function of providing assistance from institutions to local communities. WHO Special Mental Health Initiative aims to further progress towards the goals of the Comprehensive Plan mental health action 2013–2030 by ensuring that 100 million more people have access to quality and affordable mental health care.

The WHO Mental Health Gap Action Program (mhGAP) is working to develop evidence-based technical guidelines, tools and training packages to scale up services in countries, especially in low-resource settings. The program focuses on a priority list of mental health disorders, including psychosis, and aims to strengthen the capacity of non-specialized health workers in as part of an integrated approach to mental health care at all levels of care. To date, the mhGAP Program has been implemented in more than 100 WHO Member States.

The program focuses on a priority list of mental health disorders, including psychosis, and aims to strengthen the capacity of non-specialized health workers in as part of an integrated approach to mental health care at all levels of care. To date, the mhGAP Program has been implemented in more than 100 WHO Member States.

The WHO QualityRights project aims to improve the quality of care and better protect human rights in mental health and social care settings and to expand opportunities of various organizations and associations to defend the rights of persons with mental disorders and psychosocial disabilities.

The WHO guidelines on community mental health services and human rights-based approaches provide information for all stakeholders who intend to develop or transform mental health systems and services. health in accordance with international human rights standards, including the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Bibliography

(1) Harrison G, Hopper K, Craig T, Laska E, Siegel C, Wanderling J. Recovery from psychotic illness: a 15- and 25-year international follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry 2001;178:506-17.

Recovery from psychotic illness: a 15- and 25-year international follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry 2001;178:506-17.

(2) Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx). http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool?params=gbd-api-2019-permalink/27a7644e8ad28e739382d31e77589dd7 (accessed 25 September 2021)

(3) LaursenTM, Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB. Excess early mortality in schizophrenia. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology , 2014;10, 425-438.

(4) WHO. Mental health systems in selected low- and middle-income countries: a WHO-AIMS cross-national analysis. WHO: Geneva, 2009

(5) Jaeschke K et al. Global estimates of service coverage for severe mental disorders: findings from the WHO Mental Health Atlas 2017 Glob Ment Health 2021;8:e27.

FGBNU NTsPZ. ‹‹Pathology of mental activity in schizophrenia: motivation, communication, cognition››

The difficulty of revealing the nature of mental illness is primarily due to the extreme complexity and indirectness of the relationship between the main clinical (psychopathological) manifestations of diseases and their biological essence. In this respect, they undoubtedly "superior" all other diseases of the human body. Psychopathological phenomena in the form of altered behavior of patients, their actions, ideas, statements, and the like are the final, effective expression of the disturbed flow of a complex chain of brain processes.

In this respect, they undoubtedly "superior" all other diseases of the human body. Psychopathological phenomena in the form of altered behavior of patients, their actions, ideas, statements, and the like are the final, effective expression of the disturbed flow of a complex chain of brain processes.

The indirectness of the connection between clinical manifestations and the biological essence of diseases dictates a growing trend throughout the world towards their multidisciplinary study, expressing the objective need to “drag” the entire chain that mediates this connection. Since clinical manifestations are the resultant expression of the disturbances of complex brain processes hidden behind them, it is impossible to reveal the nature of the underlying disturbances of brain activity only on the basis of the analysis of these manifestations. Therefore, processes are subject to study at all levels of complexity, studied using the methods of the relevant sciences: psychology, neurophysiology, biochemistry, biophysics, genetics, etc. Each link of the study is necessary, but not sufficient to clarify the nature and mechanisms of the development of mental pathology.

Each link of the study is necessary, but not sufficient to clarify the nature and mechanisms of the development of mental pathology.

The most responsible in this chain is the transition from clinical manifestations to their biological mechanisms through the study of the patterns of disturbance of mental processes and personality traits, which for quite a long time was underestimated by the epigones of the doctrine of higher nervous activity. This caused serious damage to domestic psychiatry and medicine in general.

If psychopathological data reveal regularities in 90,428 manifestations of 90,429 disturbed mental processes [136], then experimental psychological studies should answer the question: how are patterns of structure (flow) mental processes themselves and personality traits in a particular pathology? Therefore, the main task of psychological research in the study of the pathology of the psyche is the study of mental processes, mental activity and related personality traits.

The expediency, validity of the study of certain specific types of mental activity are determined by the characteristics of the disease under study, known psychopathological data about it.

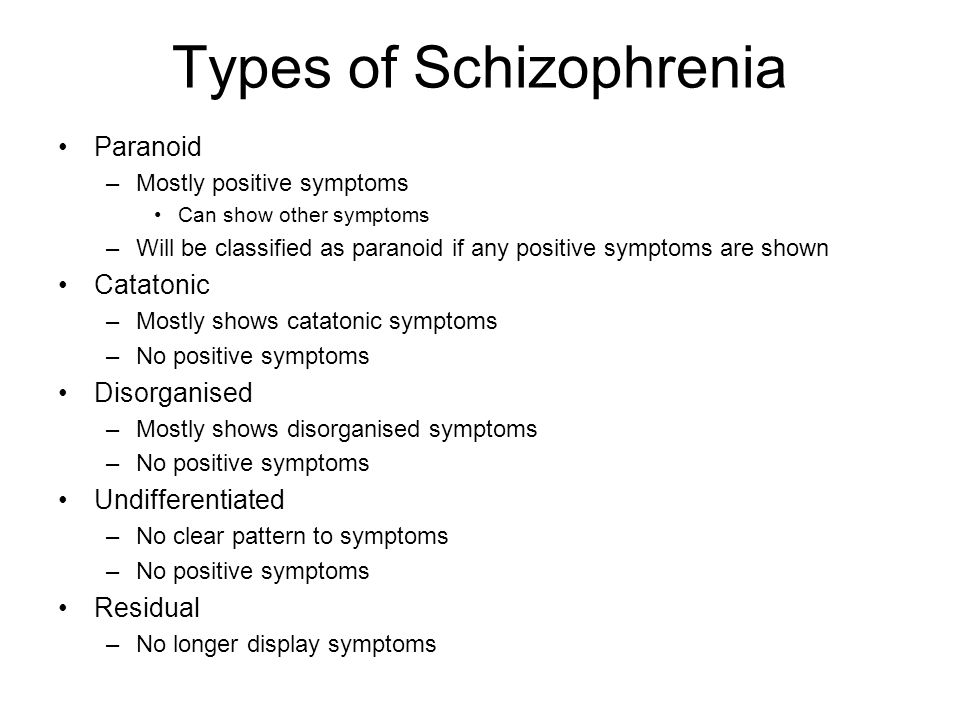

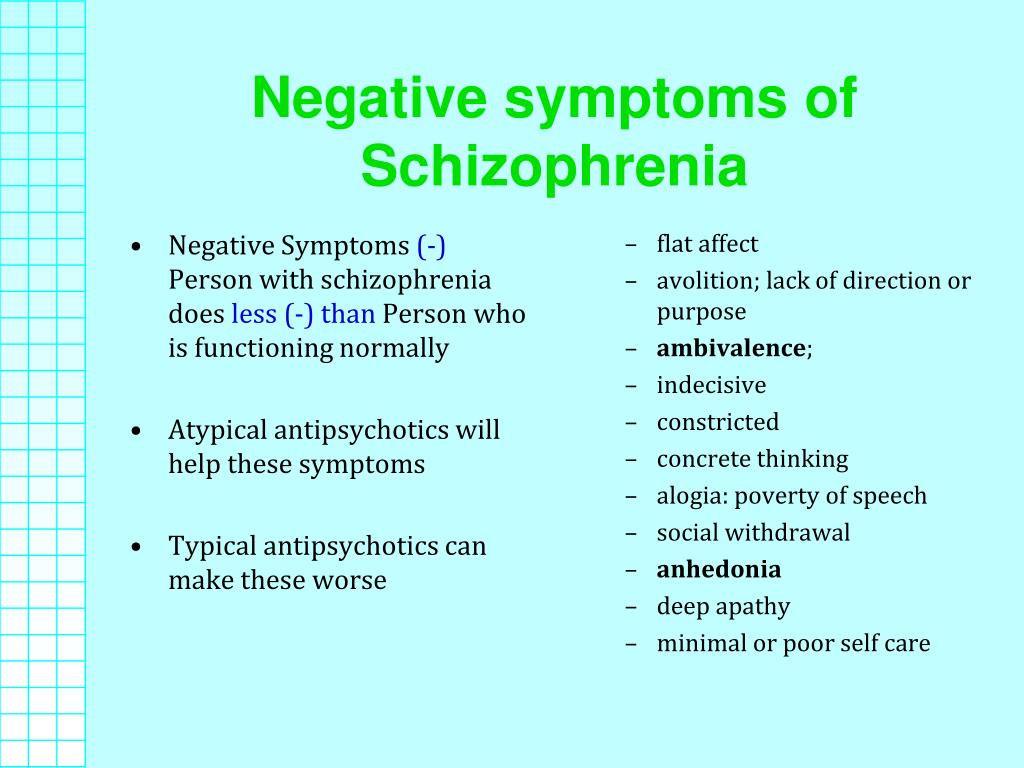

Considering the problem of mental disorders in schizophrenia, we do not mean all possible and observed types of its pathology during the course of the disease, but those changes whose manifestations are reflected in the so-called negative changes, negative symptoms of the disease, related to persistent, irreversible personality changes, characteristic for schizophrenia. This does not include all those various disorders of thinking and perception that, developing quite quickly, characterized by dynamism and, as a rule, reversibility (spontaneously or under the influence of therapy), arise in connection with the severity of the condition of patients and are observed in the picture of various syndromes - catatonic, hallucinatory - paranoid, paraphrenic, etc. We are talking about those changes in mental processes, the psychopathological manifestations of which, characterized by persistence (stability or progression) and entering the structure of various syndromes, can be observed from the very beginning of the disease (even to its manifest manifestations). They appear most clearly outside acute conditions, with a continuous sluggish course of the process or in remissions.

They appear most clearly outside acute conditions, with a continuous sluggish course of the process or in remissions.

One of the oldest (but not obsolete) problems that determine the significance of experimental psychological research on the patterns of changes in cognitive processes is the problem of the uniqueness of negative psychopathological manifestations of thinking and perception in schizophrenia. The common thing that unites most clinicians, regardless of their views on the nature, essence and course of schizophrenia, is the emphasis on the unusual, bizarre thinking disorders in schizophrenia, the inability to apply to them the well-known "measure" of dementia, which occurs in other mental illnesses, in particular in organic brain damage.

According to many authors, in contrast to the pathology of thinking in organic lesions of the central nervous system, when the abilities and operations of reproduction, attention, synthesis, abstraction, etc. are simultaneously violated, in schizophrenia patients, sometimes even with a gross defect, can perform well some types of rather complex mental activity (counting operations, solving structural-spatial problems, playing chess, etc. ), while demonstrating a good ability to concentrate and reproduce previously learned material.

), while demonstrating a good ability to concentrate and reproduce previously learned material.

These clinical data, “not giving in themselves the opportunity to understand the nature of the disturbed flow of thought processes, have constantly stimulated and continue to stimulate researchers to reveal the essence of changes in cognitive processes. And it's not just a subjective desire and need to understand this strange. a tangle of features, this is a paradoxical combination, inexplicable from the point of view of the “normal psyche” and having no analogies among other known types of its pathology. The need to study the regularities of the altered course of cognitive processes underlying these manifestations is dictated by deeper motives associated with the position that these changes express the “special” or peculiarity of the pathology of brain activity, which, in particular, this disease differs from other mental disorders. diseases.

Another motive that determines the interest and objective significance of studying the characteristics of mental activity in schizophrenia associated with its negative psychopathological manifestations is due to the significance of these manifestations themselves (persistent, irreversible personality changes) in the overall clinical picture of the disease. With all the successes of “flow” psychiatry, with the fundamental role of the criterion of dynamics (change) of syndromes used to detect stereotypes of the development of the disease (forms of the course), the psychopathological characteristic of negative changes in the psyche of three schizophrenia remains today one of the clinical criteria cementing the concept of schizophrenia and delimiting it. from other mental illnesses.

With all the successes of “flow” psychiatry, with the fundamental role of the criterion of dynamics (change) of syndromes used to detect stereotypes of the development of the disease (forms of the course), the psychopathological characteristic of negative changes in the psyche of three schizophrenia remains today one of the clinical criteria cementing the concept of schizophrenia and delimiting it. from other mental illnesses.

It is hardly necessary to reveal the significance of revealing the mechanisms, deepening our knowledge of the essence of those psychopathological manifestations, which, being so typical, serve both to unify the concept of schizophrenia and to distinguish it from other nosological categories.

Despite the fact that since the time of E. Bleuler [172] thought disorders were considered as the main, primary symptom of schizophrenia, on the basis of which the secondary symptoms of the disease were formed, many authors, including E. Bleuler himself, went beyond the scope of this pathology when analyzing this pathology. study of the actual cognitive processes. So, M. O. Gurevich and M. Ya. Sereysky [40] believed that in patients with schizophrenia, thinking is disturbed while the “prerequisites of intellect” are preserved, not so much intellectual abilities suffer as the ability to use them. At the same time, they proceeded from the opposition of the intellect, accepted in functional psychology, as a set of isolated abilities and thinking, the essence of which lies in a special “interpsychic activity” that integrates and regulates intellectual functions. I. Berce [170], X. Grule [189] talked about the potential preservation of intelligence in schizophrenia and a decrease in the activity of thinking as a result of a decrease in overall mental activity.

study of the actual cognitive processes. So, M. O. Gurevich and M. Ya. Sereysky [40] believed that in patients with schizophrenia, thinking is disturbed while the “prerequisites of intellect” are preserved, not so much intellectual abilities suffer as the ability to use them. At the same time, they proceeded from the opposition of the intellect, accepted in functional psychology, as a set of isolated abilities and thinking, the essence of which lies in a special “interpsychic activity” that integrates and regulates intellectual functions. I. Berce [170], X. Grule [189] talked about the potential preservation of intelligence in schizophrenia and a decrease in the activity of thinking as a result of a decrease in overall mental activity.

The facts that testify to the preservation of memory in patients with schizophrenia with a peculiar change in thinking served as the basis for the assumption of a number of authors about disunity, the lack of consistency between the actual thinking in these patients and the experience of the past. The reason for this separation was seen each time in accordance with the general psychological theory, which was shared by this or that researcher.

The reason for this separation was seen each time in accordance with the general psychological theory, which was shared by this or that researcher.

Thus, E. Bleiler [15] believed that the separation of thinking from experience in patients with schizophrenia is a consequence of the loosening of associations, and this leads to the establishment of false connections that do not correspond to experience. The result of this "disengagement" is also that these patients are better than healthy ones, perceive deviations from the usual and can carry out ideas that healthy people seem unthinkable. E. Bleuler suggested that such features of schizophrenic thinking as a penchant for the new, an unusual way of thinking, freedom from traditions in the absence of a rough break in associations, should favor productivity in the field of art.

Other authors [169-171; 189] tried to explain the dissociation of the thinking of patients with schizophrenia from the experience of the past, based on the opposition of productive and reproductive thinking. They talked about the disruption of productive thinking in patients with schizophrenia with intact reproductive activity. “The dissociation of the mental task from the experience of the past” is a consequence of the “hypotension of consciousness” [170]. This decline leads in the end from "active production to bare reproduction ... Instead of a thinking processing of the content of experience, a blind play of forms of thinking appears." According to Behringer, the judgments of patients with schizophrenia are each time built anew outside the usual material of thinking, the problem is not solved in terms of existing experience and knowledge. The author sees the reason for such disunity in the insufficiency of the “intentional arc”.

They talked about the disruption of productive thinking in patients with schizophrenia with intact reproductive activity. “The dissociation of the mental task from the experience of the past” is a consequence of the “hypotension of consciousness” [170]. This decline leads in the end from "active production to bare reproduction ... Instead of a thinking processing of the content of experience, a blind play of forms of thinking appears." According to Behringer, the judgments of patients with schizophrenia are each time built anew outside the usual material of thinking, the problem is not solved in terms of existing experience and knowledge. The author sees the reason for such disunity in the insufficiency of the “intentional arc”.

Based on the opposition of productive thinking to reproductive, the conclusion about the inability of patients with schizophrenia to productive activity [169; 189; 94] contradicts the known facts about the preserved ability of these patients to perform certain types of mental (and not purely reproductive) activities: mathematical thinking, playing chess, constructive activity, etc. These same facts do not give grounds for such a categorical conclusion about the separation of the actual thinking with past experience. Such disunity would make it impossible for any productive activity in patients with schizophrenia.

These same facts do not give grounds for such a categorical conclusion about the separation of the actual thinking with past experience. Such disunity would make it impossible for any productive activity in patients with schizophrenia.

Practically all researchers who developed the problems of schizophrenic defect further relied on these data, which testify to the peculiarity of mental disorders in patients with schizophrenia. The main characteristics of a schizophrenic defect were primarily autism (the patient is fenced off from other people, immersed in his inner world, loss of contact with others), emotional impoverishment, and a decrease in mental activity. Most authors emphasize the presence of dissociation at different levels of mental activity, both at the level of thinking and in a broader sense, partiality is also noted in emotional life in the distribution of interests and orientation of the individual. These features form that special quality that manifests itself in any syndromic "design" of the clinical picture of schizophrenia. This originality at different stages of the study of schizophrenia was designated in different ways: as “schism”, “weakening of intention”, “discordance”, “personality changes”. This quality is especially evident when the severity of the condition is weakened - in remission, at the stages of a sluggish, calm course, or in the outcome of the disease. Many authors associate the specificity of the manifestations of a schizophrenic defect primarily with personality changes, a violation of the personality structure (disharmony of the personality type [135], deformation of the personality structure [196], personality discordance [183], and the presence of pseudo-organic features is noted by some of them only when the defect deepens.

This originality at different stages of the study of schizophrenia was designated in different ways: as “schism”, “weakening of intention”, “discordance”, “personality changes”. This quality is especially evident when the severity of the condition is weakened - in remission, at the stages of a sluggish, calm course, or in the outcome of the disease. Many authors associate the specificity of the manifestations of a schizophrenic defect primarily with personality changes, a violation of the personality structure (disharmony of the personality type [135], deformation of the personality structure [196], personality discordance [183], and the presence of pseudo-organic features is noted by some of them only when the defect deepens.

Another approach to considering a schizophrenic defect underestimates its specificity, since its main manifestations include a reduction in the energy potential [179], as well as asthenic and pseudo-organic disorders. Changes in the sphere of personality, emotions, thinking are generally not considered in this case as signs of a defect, since they are reversible and are included in the defect for the second time.

In recent years, in the systematics of the schizophrenic defect, there has been a tendency to consider it as "polythetic", having a complex structure, including both pseudo-organic disorders and schizoid personality changes [167]. V. Yu. Vorobyov [26] formulated a hypothesis about the "integration" nature of the schizophrenic defect, which combines both schizoid and pseudo-organic changes. According to this concept, with a slow pace of the course of the disease, schizoid personality changes come to the fore, which culminate in the formation of a “Verschroben” type defect. In the progressive course of schizophrenia, pseudo-organic disorders predominate in the structure of the defect, and personality disorders are formed according to the type of deficient schizoids. The integration of two trends in the development of a single defect made it possible to combine two extreme points of view in the interpretation of a schizophrenic defect, which assess its specificity in different ways.

For the psychological analysis of such a complex and controversial phenomenon as the pathology of mental activity in schizophrenia, it is necessary to consider all available clinical and experimental data from the standpoint of modern psychological science, using its new theoretical and methodological approaches.

The greatest number of experimental works was devoted to the study of cognitive processes in schizophrenia (thinking, perception). Many of them were and are still being conducted in line with the traditional analysis of the correlation between the levels of cognitive processes - sensory-concrete and abstract [29; 190; 185; 222; 181; 210; 235]. On this path, a large number of contradictory facts were obtained, some of which testified to the predominantly "concrete" nature of the thinking of patients with schizophrenia, others, on the contrary, to the "overabstractness" of these patients. A number of studies conducted in terms of comparing the two levels of thinking did not confirm both the conclusion about the concreteness of the thinking of patients with schizophrenia, and the opposite conclusion about the abstract nature of the thinking of these patients. The authors of these studies, using various tests for the classification of objects and the formation of concepts, note the unusual generalizations of patients with schizophrenia.

The authors of these studies, using various tests for the classification of objects and the formation of concepts, note the unusual generalizations of patients with schizophrenia.

Thus, the results of studies conducted in terms of analyzing the levels of thinking indicate the inadequacy of this approach to identify the pathology of thinking that is specific to patients with schizophrenia. The futility of this trend is increasingly recognized by many of its former supporters.

Another line of research into mental processes was associated with the identification of the facts and mechanisms of the so-called "over-inclusions" in schizophrenia. This term was introduced by N. Cameron [173; 174; 175], who in his works emphasized the significant difference between the thinking of patients with schizophrenia and children's thinking, on the one hand, and from thinking disorders observed in organic diseases of the central nervous system, on the other. The author characterizes the thinking of patients as "super-inclusive", i. e., when solving various problems, patients attract an excessive number of categories or, as it was designated later, information. Cameron associated this phenomenon with a violation of interpersonal relations, thereby emphasizing the role of the social determination of this pathology.

e., when solving various problems, patients attract an excessive number of categories or, as it was designated later, information. Cameron associated this phenomenon with a violation of interpersonal relations, thereby emphasizing the role of the social determination of this pathology.

In the future, studies of the pathology of mental activity were carried out mainly within the framework of the cognitive direction. Its essence is to fix the post-behavioral orientation of psychology, which includes in its subject a set of cognitive processes (perception, memory, thinking, representation). The leading determinant of behavior here is not a stimulus, but knowledge of the reality surrounding a person, its ultimate goal is to analyze the patterns of organization and functioning of internal representations of the environment.

Research on cognitive orientation has gone in two directions. The first was based on the informational approach to the analysis of mental phenomena and mental pathology; the second, not limited to the analysis of cognitive processes proper, raised the question of the influence of interpersonal relations on these processes.

The facts of overinclusion in cognition in schizophrenia have been widely described and often received a very ambiguous interpretation in different studies. Thus, in the works of the Canadian researcher T. Vekovich and his colleagues [247], these phenomena were interpreted from the standpoint of the well-known and currently widespread selective theory of the American psychologist J. Bruner [22]. The presence of hyperinclusions in the thinking of patients with schizophrenia was associated with their inability to maintain the set [234] or with the inability to resist emotional stimuli [242]. Further studies of the problem of super-inclusive cognition are connected both with the refinement of the concept itself and with the improvement of methods for its study [177].

The direction of research related to the study of superinclusions in schizophrenia seems to be productive, first of all, in relation to revealing facts that reflect the originality of the pathology of thinking in schizophrenia compared to other types of thinking disorders. These facts testify to the expansion of the amount of information in patients with schizophrenia, the range of properties and relationships included in the thinking process. Despite numerous attempts to give different interpretations of these facts, the true psychological mechanisms of this pathology remain unclear. The data obtained are either analyzed from the standpoint of information theory, or attempts are made to interpret them from the standpoint of various physiological theories. At the same time, the actual psychological patterns of the pathology of cognitive activity are not the subject of analysis.

These facts testify to the expansion of the amount of information in patients with schizophrenia, the range of properties and relationships included in the thinking process. Despite numerous attempts to give different interpretations of these facts, the true psychological mechanisms of this pathology remain unclear. The data obtained are either analyzed from the standpoint of information theory, or attempts are made to interpret them from the standpoint of various physiological theories. At the same time, the actual psychological patterns of the pathology of cognitive activity are not the subject of analysis.

The second line of research related to cognitive orientation is carried out in line with the psychodynamic concept, emphasizing the leading role of environmental influences (primarily intra-family relations) in the formation of the pathology of mental processes. Most actively these works are carried out in the USA (National Institute of Mental Health, Yale University, etc. ). These studies are aimed at studying families with a schizophrenic descendant [206; 226; 248; 249].

). These studies are aimed at studying families with a schizophrenic descendant [206; 226; 248; 249].

Inclusion in the study of parents and their offspring suggested the possibility of searching for common features of the psyche, for this purpose the cognitive style of both was determined. These works emphasized the leading role of environmental, intra-family relations in the formation of both the pathology of the psyche and schizophrenia itself.

However, at present, the opinion is increasingly asserted that the violation of family relations is a necessary, but not sufficient condition for the development of schizophrenia and the formation of a special cognitive style, which is considered as the “main pathology” in schizophrenia [186], i.e. in the development This pathology is allowed to be influenced by other factors, in particular genetic and constitutional. In this regard, work is underway using twin material [216].

The field of study of cognitive styles lies at the intersection of the psychology of cognitive processes and the psychology of personality. Interest in it, which was clearly indicated in American psychology in the early 1950s, testifies to the realization of the fact that the study of only general patterns inherent in all people cannot satisfy the psychologist. No less important is the question of the individual characteristics of cognitive activity. Thus, the study of cognitive styles was a necessary addition to the study of the general mechanisms of cognitive activity. Cognitive style is considered as a feature of cognitive processes (primarily perception and thinking), which is consistently manifested in a person in various situations, when solving various problems. It should be emphasized that here we are talking about the stylistic features of cognitive activity, studied regardless of its content.

Interest in it, which was clearly indicated in American psychology in the early 1950s, testifies to the realization of the fact that the study of only general patterns inherent in all people cannot satisfy the psychologist. No less important is the question of the individual characteristics of cognitive activity. Thus, the study of cognitive styles was a necessary addition to the study of the general mechanisms of cognitive activity. Cognitive style is considered as a feature of cognitive processes (primarily perception and thinking), which is consistently manifested in a person in various situations, when solving various problems. It should be emphasized that here we are talking about the stylistic features of cognitive activity, studied regardless of its content.

The undoubted advantage of this approach is going beyond the study of cognitive processes proper, the study of their personal aspect. However, the very concept of "cognitive style impairment" is based on the consideration of a conglomerate of various types of pathological reactions and processes without analyzing their internal relationships as a reflection of a single system.

An important place in modern research is occupied by questions about the role of social mediation of mental activity. They address a wide range of issues, in particular, those related to the ability of patients with schizophrenia to generate ideas and make decisions in interpersonal problem situations, to solve interpersonal problems [220]. Schizophrenic patients have been shown to have less complex and differentiating personality constructs than healthy individuals. A number of authors have studied the influence of social reinforcement and social assessments on the behavior of patients with schizophrenia. The results of the studies showed a lower susceptibility of patients to social reinforcement and a decrease in the role of social assessments, which, of course, has an impact on the quality of interpersonal relationships and functioning. To study it, various theoretical models are created. However, the individual components that make up the structure of interpersonal functioning, as a rule, are studied in isolation from each other, and not in a single system [245].

A complete picture of the features of the social behavior of patients with schizophrenia, including both motivational, and regulatory, and behavioral components, can only be obtained by implementing an activity approach in a study that involves studying patients in real activity, in the process of their "live" interaction with others.

The activity approach to the analysis of mental phenomena is being developed in Russian psychology, it is based on the works of S. L. Rubinshtein [123], A. N. Leontiev [77]. Its essence is the position that the mental is formed and realized in human activity through a complex interaction of external and internal conditions.

S. L. Rubinshtein revealed the principle of individualization of personality as the selectivity of the internal in relation to the external, the ability of the internal to transform the external, mediate it and objectify it. Developing these provisions further, K.A. Abulkhanova-Slavskaya [2] emphasizes the fundamental importance of this method in constructing a theory of personality and in developing its typology. The peculiarity of this approach is that this method does not imply a set of personality traits, but reveals the driving forces of its activity, correlates them with social needs, with social driving forces. Often in social psychology, the internal activity of the individual and his social positions are torn apart, the dynamics is seen only in the change of role positions, in their performance, which does not affect the internal activity of the individual. The dialectical principle - external causes act through internal conditions - fixes not a factorial coincidence of certain personality traits with certain social processes, but causal ways of connecting external and internal tendencies, realizing the principle of personality analysis through its life activity. The organization of life by a person is carried out with the simultaneous counter process of regulation on the part of society and on the basis of self-regulation. One of the forms of activity, which can rightfully be considered the driving force of the personality, is its orientation.

The peculiarity of this approach is that this method does not imply a set of personality traits, but reveals the driving forces of its activity, correlates them with social needs, with social driving forces. Often in social psychology, the internal activity of the individual and his social positions are torn apart, the dynamics is seen only in the change of role positions, in their performance, which does not affect the internal activity of the individual. The dialectical principle - external causes act through internal conditions - fixes not a factorial coincidence of certain personality traits with certain social processes, but causal ways of connecting external and internal tendencies, realizing the principle of personality analysis through its life activity. The organization of life by a person is carried out with the simultaneous counter process of regulation on the part of society and on the basis of self-regulation. One of the forms of activity, which can rightfully be considered the driving force of the personality, is its orientation.

The personal approach helps bridge the gap between considering thinking as intelligence, on the one hand, and a cognitive attitude to the world, on the other. The subject of the first is the solution of problems and tasks, the subject of the second is the knowledge of the social world. Accordingly, the mechanisms of intelligence as creativity and problem solving are one, the mechanisms of a cognitive attitude to the world are different. As K.A. Abulkhanova-Slavskaya notes [3], it is possible to reveal the unity and difference between the two areas of knowledge that are developing separately today only through the analysis of personality. The predominance of the problematic aspect in cognitive terms, the ability to overcome mindset thinking, etc., depend not only on the intellectual potential of the individual, her creativity, but also on her socio-psychological position, the transition to the allocation of the universal and generally valid. If a person stands on generally significant positions, his thinking is not monological, but dialogical, the object is considered simultaneously from different positions; her attitudes, cognitive schemes are more general in comparison with a person who occupies an egocentric position.

The basis that determines the consideration of the human psyche as a whole is the personality in the unity of its initial motives and motives, its orientation and ultimate goals. The task is psychological. science is the allocation of individual components and the disclosure of structural relationships within this unity. This approach was developed in a number of studies by Soviet psychologists. In pathopsychology, such a personal approach was carried out primarily in the works of B. V. Zeigarnik [46-50].

B. V. Zeigarnik pointed out two possible ways in the study of personality pathology: more direct - observation of the behavior and reactions of the patient in the experimental situation along with the analysis of data from case histories and indirect identification of personality changes using the experiment, for example, in the study of cognitive processes, since cognitive processes do not exist in isolation from the attitudes of the individual, his needs, emotions. She clearly preferred methods that implement the activity approach compared to the use of questionnaires, questionnaires, etc. Such an activity approach was implemented in experimental studies by studying the system of motives in patients [49; 51].

She clearly preferred methods that implement the activity approach compared to the use of questionnaires, questionnaires, etc. Such an activity approach was implemented in experimental studies by studying the system of motives in patients [49; 51].

The category of the syndrome, syndromic psychological analysis of mental disorders are the central point of this work.

Following A. R. Luria [82], who studied patients with local (focal) brain pathology, since the late 60s we have been developing and applying a syndromic psychological approach in studying the nature of mental illness [111; 112; 114; 115]. The ontological basis of the syndrome is any pathological state of the body that causes a change in the complex (system) of interrelated functions and processes.

Continuing this line of research in relation to the analysis of the pathology of mental activity in patients with schizophrenia, we examine the disturbance of motivation in the structure of the main pathological topsychological syndrome. It is a system of disturbed mental processes and properties that make up the psychological basis for negative changes in the psyche in schizophrenia (autism, decreased mental activity, emotional changes, etc.). The task of the study is to identify individual components within this single system and analyze their relationships. The definition of the leading components in the structure of the psychological syndrome will allow us to consider its varieties.

It is a system of disturbed mental processes and properties that make up the psychological basis for negative changes in the psyche in schizophrenia (autism, decreased mental activity, emotional changes, etc.). The task of the study is to identify individual components within this single system and analyze their relationships. The definition of the leading components in the structure of the psychological syndrome will allow us to consider its varieties.

Research hypothesis: the leading component of the pathopsychological syndrome that determines the specifics of a schizophrenic defect (all its varieties) is a violation of the need-motivational characteristics of mental activity. They include a system of needs, primarily the need for communication, characteristics of mental activity determined by needs, and emotional-volitional processes.

Violation of the performance component of regulation - the means of carrying out activities (abilities, operations, methods of action, skills, abilities, etc. ) - is secondary and depends on the level of decrease in the need-motivational characteristics of the psyche.

) - is secondary and depends on the level of decrease in the need-motivational characteristics of the psyche.

The hypothesis and the main tasks determined the methodological methods of the study, which involve the inclusion of subjects in activities that differ in structure, content, complexity, and degree of social mediation, the implementation of which is associated with different levels of regulation.

According to the formulated hypothesis, the introduction of various kinds of motivating stimuli into the experimental situation was of particular importance. This made it possible to discover the hidden, reserve capabilities of the subjects, which, due to a decrease in motivation, remained unrealized in them. At the same time, the very fact of the possibility of increasing the level of activity under the influence of motivating incentives could be the most direct evidence of the motivational nature of the decrease in the level of social regulation of activity.

An essential feature of the study was the principle of clinical certainty of the studied group of patients.