Zoloft for aspergers

Medications for Autism I Psych Central

There is no cure for autism spectrum disorder, but medications might help improve some behaviors related to the condition, such as hyperactivity and aggression.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder, meaning it can affect the way a person behaves, interacts, and communicates.

Autism exists on a spectrum, and there’s a wide range of support needs within that spectrum. The level of support needed varies from person to person. No two autistic people are alike.

So, clinicians will work with you to determine the level of your individual needs. This will help them develop the right management plan for you.

There is no single best way to manage autism. Services typically include behavioral therapies and educational programs. In some cases, medication might be used to help manage certain conditions that often occur alongside autism.

But medications are not intended to act as a “cure” for autism. If you or your child are prescribed medication, consider monitoring for behavior changes and side effects, and track progress. If you see anything concerning, reach out to your healthcare or mental health professional.

Medication for autism is a complicated and controversial topic.

Researchers estimate that more than 50% of autistic children and adolescents are prescribed medications to help manage autism-related behaviors or co-occurring conditions.

A 2013 study showed that 64% percent of autistic children were prescribed at least one psychiatric medication, and 35% percent were taking more than one. Autistic adults may be more likely to take more than one medication.

There is no medication for autism itself or for its core symptoms, which are usually classified into three categories:

- difficulties with social interactions

- trouble communicating

- repetitive behaviors

Medication may, however, be used to manage behaviors or conditions that tend to co-occur with autism.

A class of antidepressants called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are commonly used to treat depression. They work by changing your levels of serotonin — a neurotransmitter in the brain believed to be responsible for stabilizing your mood.

Research indicates that SSRIs might help reduce the intensity and frequency of these autism-related behaviors:

- repetitive actions

- anxiety

- irritability

- tantrums

- aggressive actions

SSRIs that might be prescribed include:

- fluoxetine (Prozac)

- sertraline (Zoloft)

- escitalopram (Lexapro)

- paroxetine (Paxil)

- citalopram (Celexa)

- fluvoxamine (Luvox)

The SSRIs most commonly prescribed to autistic people are fluoxetine and sertraline.

Sertraline is often the top choice because its side effects are milder than those of other SSRIs and because it has fewer interactions with other drugs. Also, it has been approved by the FDA for treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in children, though not for autism.

However, two other more recent studies — one in 2019 and another in 2020 — show that SSRIs, particularly fluoxetine (Prozac), do not improve repetitive behaviors in autistic children and adolescents. These findings echo results from earlier research.

Yet, these medications remain widely prescribed because they sometimes help manage symptoms of conditions that co-occur with autism, like anxiety and depression. In fact, according to a 2019 clinical trial, approximately 21% to 32% of autistic children and adolescents are prescribed SSRIs.

SSRIs can have significant side effects, such as:

- agitation

- anxiety

- diarrhea or constipation

- weight change

- dizziness

- dry mouth

Parents and caregivers of autistic children are often concerned that the long-term effects of SSRIs have yet to be fully determined. The FDA continues to require black box warnings on SSRI labels advising of an increased risk of suicidal ideation and behavior in teens and young adults. This warning has been in effect since 2004.

This warning has been in effect since 2004.

Tricyclic antidepressants are the oldest of the antidepressants, dating back to the 1960s. They work by reducing the reuptake, or absorption, of two neurotransmitters — norepinephrine (also called noradrenaline) and serotonin.

This increases availability of these neurotransmitters in the central nervous system, which is believed to help improve behaviors such as:

- irritability

- hyperactivity

- inappropriate speech

Common tricyclics used include:

- amitriptyline (Elavil)

- clomipramine (Anafranil)

- desipramine (Norpramin)

Tricyclic medications are less commonly used because they tend to cause more severe side effects than SSRIs.

You may also have a higher chance of overdosing with tricyclics than other antidepressants. Taking even a small amount over your normal dose can lead to an overdose.

The most common side effects of tricyclics are:

- weight gain

- drowsiness

- dizziness

- dry mouth

- constipation

- urinary retention (when your bladder doesn’t feel empty)

- confusion

- blurred vision or dry eyes

The atypical antipsychotics risperidone (Risperdal) and aripiprazole (Abilify) are the only two medications approved by the FDA to help reduce irritability in autistic children and teens.

This category of newer drugs has different side effects than the original antipsychotics. Antipsychotic medications are thought to work by affecting dopamine, a neurotransmitter in your brain associated with pleasure and reward. Dopamine is also believed to contribute to mood and decision-making.

Other atypical antipsychotics sometimes prescribed are:

- clozapine (Clozaril)

- olanzapine (Zyprexa)

- quetiapine fumarate (Seroquel)

- ziprasidone (Geodon)

Two older antipsychotics sometimes used include:

- haloperidol (Haldol)

- chlorpromazine (Thorazine)

Common side effects associated with atypical antipsychotics include:

- sleepiness

- weight gain

- trouble with movement

- tremors

Stimulants are often prescribed for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). It’s common for autistic children to also have ADHD, or some of the same symptoms — such as hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity.

Methylphenidate (Ritalin) is the stimulant most commonly prescribed to autistic children with ADHD.

Other stimulants that might be used include:

- amphetamine mixed salts (Adderall, Adderall XR)

- methylphenidate XR (Concerta, Metadate CD)

- dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine)

- dexmethylphenidate (Focalin)

However, research on whether stimulants are in fact helpful in autistic children with ADHD is mixed. While some studies say that it’s effective and children are able to tolerate this medication, others state the opposite.

The challenge with stimulants is finding a medication with side effects that the child can tolerate. In some cases, stimulants can cause behaviors to worsen, possibly leading to aggressiveness or violent meltdowns.

Anxiety is a common co-occurring condition in autistic people. Some research suggests that around 50% of autistic adults and children live with anxiety. If you have autism, you might experience:

- social anxiety

- panic attacks

- obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

- generalized anxiety (GAD)

Managing anxiety in autistic children and adults is complicated. Sometimes, the same symptoms occur in both autism and anxiety disorders, so it’s difficult to know which one came first. Are the autism-related behaviors causing the anxiety, or is the anxiety causing the autism-type behaviors?

Sometimes, the same symptoms occur in both autism and anxiety disorders, so it’s difficult to know which one came first. Are the autism-related behaviors causing the anxiety, or is the anxiety causing the autism-type behaviors?

Also, research into anxiety treatments for autistic children and adults is minimal and often contradictory.

According to the National Institutes of Mental Health, the three main medications for anxiety are:

- antidepressants

- anti-anxiety medications

- beta-blockers

Research is mixed about whether these work for anxiety in autistic people. One study recommends that anti-anxiety medication be used only after behavioral interventions have not helped. Also, correcting problematic situations like bullying at school might help improve the anxiety.

The researchers suggest the following medications might be tried, but with caution and careful medical supervision, as some of them carry a black box warning from the FDA regarding their use in children:

- sertraline (Zoloft)

- fluoxetine (Prozac)

- clonidine (Catapres)

- buspirone

- citalopram (Celexa)

- escitalopram (Lexapro)

Each medication carries its own side effects, but some common ones include:

- dizziness

- drowsiness

- headache

- nausea and vomiting

- dry mouth

- constipation or upset stomach

Anti-seizure medications are sometimes used to treat other medical conditions co-occurring with autism, like seizure disorders.

Epilepsy, a seizure disorder, is common in autistic people. Research suggests that epilepsy occurs in about 12% of autistic people.

Common anti-seizure medications used are:

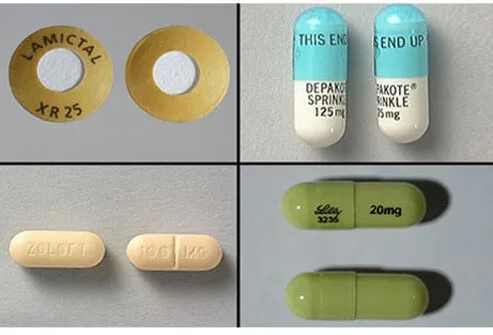

- carbamazepine (Tegretol)

- clonazepam (Klonopin)

- diazepam (Valium)

- divalproex (Depakote)

- lamotrigine (Lamictal)

- levetiracetam (Keppra)

- oxcarbazepine (Trileptal)

- topiramate (Topamax)

The common side effects of anti-seizure medications include:

- weight gain

- stomach problems

- headache

- fatigue or drowsiness

- aggression

- agitation

Finding the right medication for your child can be challenging. Giving medicine to an autistic child is never an easy choice. You might worry that the medication will somehow change your child into someone you don’t know, or that the side effects will be too much for them.

You may even wonder if medication is needed at all.

You might start out by asking your doctor — or your child’s doctor — whether medication is even an option.

Remember: Medications don’t cure autism. They can, however, treat symptoms or behaviors associated with autism.

If a doctor has recommended that you or your child take medication, here are some questions to consider asking:

- Why are you recommending medication?

- What can I expect the medication to do?

- What side effects I should watch out for?

- Who do I contact if my child has problems or I have concerns?

- Are there any foods or medicines that will affect this medication?

- How often will we come back for follow-up visits? Who will we see?

- Will insurance cover this? How much will it cost?

Once your child has started medication, unwanted side effects may arise, like increased irritability or agitation. Also, symptoms may remain even after starting the medication.

A regimen of polypharmacy — taking several medications to manage one condition — might be started.

If you or your child are experiencing side effects, a second drug may be prescribed to help manage them. A separate drug might also be suggested for each individual symptom.

A separate drug might also be suggested for each individual symptom.

For example, a stimulant might be given for inattention, an SSRI for depression or anxiety, and an antipsychotic for aggression.

Polypharmacy can be useful, but it can sometimes cause adverse drug interactions. Be aware of each medication being prescribed, and why. Make sure both you and all your caregivers know the potential side effects or drug interactions to watch out for.

Whether you’re the caregiver of an autistic child or an autistic adult, you’re not alone. There are many social services, community education programs, and other resources available to help you.

Here are some tips for finding the services you need:

- Your doctor, local health department, or school can provide information about special programs or resources. You can find resources near you through the Autism Society.

- Your local chapter of the National Autism Association can also provide help and resources.

- If you need help with employment and career issues, you can visit the U.S. Department of Labor autism resource list.

- You can find an autism support group where you can share information and learn about treatment options and programs.

- During meetings with school staff and medical professionals, consider taking detailed notes. These will help you make decisions about treatment along the way.

- It’s a good idea to keep any copies of medical reports or evaluations. These will be helpful when you apply for special programs.

Medications for Autism I Psych Central

There is no cure for autism spectrum disorder, but medications might help improve some behaviors related to the condition, such as hyperactivity and aggression.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder, meaning it can affect the way a person behaves, interacts, and communicates.

Autism exists on a spectrum, and there’s a wide range of support needs within that spectrum. The level of support needed varies from person to person. No two autistic people are alike.

The level of support needed varies from person to person. No two autistic people are alike.

So, clinicians will work with you to determine the level of your individual needs. This will help them develop the right management plan for you.

There is no single best way to manage autism. Services typically include behavioral therapies and educational programs. In some cases, medication might be used to help manage certain conditions that often occur alongside autism.

But medications are not intended to act as a “cure” for autism. If you or your child are prescribed medication, consider monitoring for behavior changes and side effects, and track progress. If you see anything concerning, reach out to your healthcare or mental health professional.

Medication for autism is a complicated and controversial topic.

Researchers estimate that more than 50% of autistic children and adolescents are prescribed medications to help manage autism-related behaviors or co-occurring conditions.

A 2013 study showed that 64% percent of autistic children were prescribed at least one psychiatric medication, and 35% percent were taking more than one. Autistic adults may be more likely to take more than one medication.

There is no medication for autism itself or for its core symptoms, which are usually classified into three categories:

- difficulties with social interactions

- trouble communicating

- repetitive behaviors

Medication may, however, be used to manage behaviors or conditions that tend to co-occur with autism.

A class of antidepressants called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are commonly used to treat depression. They work by changing your levels of serotonin — a neurotransmitter in the brain believed to be responsible for stabilizing your mood.

Research indicates that SSRIs might help reduce the intensity and frequency of these autism-related behaviors:

- repetitive actions

- anxiety

- irritability

- tantrums

- aggressive actions

SSRIs that might be prescribed include:

- fluoxetine (Prozac)

- sertraline (Zoloft)

- escitalopram (Lexapro)

- paroxetine (Paxil)

- citalopram (Celexa)

- fluvoxamine (Luvox)

The SSRIs most commonly prescribed to autistic people are fluoxetine and sertraline.

Sertraline is often the top choice because its side effects are milder than those of other SSRIs and because it has fewer interactions with other drugs. Also, it has been approved by the FDA for treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in children, though not for autism.

However, two other more recent studies — one in 2019 and another in 2020 — show that SSRIs, particularly fluoxetine (Prozac), do not improve repetitive behaviors in autistic children and adolescents. These findings echo results from earlier research.

Yet, these medications remain widely prescribed because they sometimes help manage symptoms of conditions that co-occur with autism, like anxiety and depression. In fact, according to a 2019 clinical trial, approximately 21% to 32% of autistic children and adolescents are prescribed SSRIs.

SSRIs can have significant side effects, such as:

- agitation

- anxiety

- diarrhea or constipation

- weight change

- dizziness

- dry mouth

Parents and caregivers of autistic children are often concerned that the long-term effects of SSRIs have yet to be fully determined. The FDA continues to require black box warnings on SSRI labels advising of an increased risk of suicidal ideation and behavior in teens and young adults. This warning has been in effect since 2004.

The FDA continues to require black box warnings on SSRI labels advising of an increased risk of suicidal ideation and behavior in teens and young adults. This warning has been in effect since 2004.

Tricyclic antidepressants are the oldest of the antidepressants, dating back to the 1960s. They work by reducing the reuptake, or absorption, of two neurotransmitters — norepinephrine (also called noradrenaline) and serotonin.

This increases availability of these neurotransmitters in the central nervous system, which is believed to help improve behaviors such as:

- irritability

- hyperactivity

- inappropriate speech

Common tricyclics used include:

- amitriptyline (Elavil)

- clomipramine (Anafranil)

- desipramine (Norpramin)

Tricyclic medications are less commonly used because they tend to cause more severe side effects than SSRIs.

You may also have a higher chance of overdosing with tricyclics than other antidepressants. Taking even a small amount over your normal dose can lead to an overdose.

Taking even a small amount over your normal dose can lead to an overdose.

The most common side effects of tricyclics are:

- weight gain

- drowsiness

- dizziness

- dry mouth

- constipation

- urinary retention (when your bladder doesn’t feel empty)

- confusion

- blurred vision or dry eyes

The atypical antipsychotics risperidone (Risperdal) and aripiprazole (Abilify) are the only two medications approved by the FDA to help reduce irritability in autistic children and teens.

This category of newer drugs has different side effects than the original antipsychotics. Antipsychotic medications are thought to work by affecting dopamine, a neurotransmitter in your brain associated with pleasure and reward. Dopamine is also believed to contribute to mood and decision-making.

Other atypical antipsychotics sometimes prescribed are:

- clozapine (Clozaril)

- olanzapine (Zyprexa)

- quetiapine fumarate (Seroquel)

- ziprasidone (Geodon)

Two older antipsychotics sometimes used include:

- haloperidol (Haldol)

- chlorpromazine (Thorazine)

Common side effects associated with atypical antipsychotics include:

- sleepiness

- weight gain

- trouble with movement

- tremors

Stimulants are often prescribed for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). It’s common for autistic children to also have ADHD, or some of the same symptoms — such as hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity.

It’s common for autistic children to also have ADHD, or some of the same symptoms — such as hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity.

Methylphenidate (Ritalin) is the stimulant most commonly prescribed to autistic children with ADHD.

Other stimulants that might be used include:

- amphetamine mixed salts (Adderall, Adderall XR)

- methylphenidate XR (Concerta, Metadate CD)

- dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine)

- dexmethylphenidate (Focalin)

However, research on whether stimulants are in fact helpful in autistic children with ADHD is mixed. While some studies say that it’s effective and children are able to tolerate this medication, others state the opposite.

The challenge with stimulants is finding a medication with side effects that the child can tolerate. In some cases, stimulants can cause behaviors to worsen, possibly leading to aggressiveness or violent meltdowns.

Anxiety is a common co-occurring condition in autistic people. Some research suggests that around 50% of autistic adults and children live with anxiety. If you have autism, you might experience:

Some research suggests that around 50% of autistic adults and children live with anxiety. If you have autism, you might experience:

- social anxiety

- panic attacks

- obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

- generalized anxiety (GAD)

Managing anxiety in autistic children and adults is complicated. Sometimes, the same symptoms occur in both autism and anxiety disorders, so it’s difficult to know which one came first. Are the autism-related behaviors causing the anxiety, or is the anxiety causing the autism-type behaviors?

Also, research into anxiety treatments for autistic children and adults is minimal and often contradictory.

According to the National Institutes of Mental Health, the three main medications for anxiety are:

- antidepressants

- anti-anxiety medications

- beta-blockers

Research is mixed about whether these work for anxiety in autistic people. One study recommends that anti-anxiety medication be used only after behavioral interventions have not helped. Also, correcting problematic situations like bullying at school might help improve the anxiety.

Also, correcting problematic situations like bullying at school might help improve the anxiety.

The researchers suggest the following medications might be tried, but with caution and careful medical supervision, as some of them carry a black box warning from the FDA regarding their use in children:

- sertraline (Zoloft)

- fluoxetine (Prozac)

- clonidine (Catapres)

- buspirone

- citalopram (Celexa)

- escitalopram (Lexapro)

Each medication carries its own side effects, but some common ones include:

- dizziness

- drowsiness

- headache

- nausea and vomiting

- dry mouth

- constipation or upset stomach

Anti-seizure medications are sometimes used to treat other medical conditions co-occurring with autism, like seizure disorders.

Epilepsy, a seizure disorder, is common in autistic people. Research suggests that epilepsy occurs in about 12% of autistic people.

Common anti-seizure medications used are:

- carbamazepine (Tegretol)

- clonazepam (Klonopin)

- diazepam (Valium)

- divalproex (Depakote)

- lamotrigine (Lamictal)

- levetiracetam (Keppra)

- oxcarbazepine (Trileptal)

- topiramate (Topamax)

The common side effects of anti-seizure medications include:

- weight gain

- stomach problems

- headache

- fatigue or drowsiness

- aggression

- agitation

Finding the right medication for your child can be challenging. Giving medicine to an autistic child is never an easy choice. You might worry that the medication will somehow change your child into someone you don’t know, or that the side effects will be too much for them.

Giving medicine to an autistic child is never an easy choice. You might worry that the medication will somehow change your child into someone you don’t know, or that the side effects will be too much for them.

You may even wonder if medication is needed at all.

You might start out by asking your doctor — or your child’s doctor — whether medication is even an option.

Remember: Medications don’t cure autism. They can, however, treat symptoms or behaviors associated with autism.

If a doctor has recommended that you or your child take medication, here are some questions to consider asking:

- Why are you recommending medication?

- What can I expect the medication to do?

- What side effects I should watch out for?

- Who do I contact if my child has problems or I have concerns?

- Are there any foods or medicines that will affect this medication?

- How often will we come back for follow-up visits? Who will we see?

- Will insurance cover this? How much will it cost?

Once your child has started medication, unwanted side effects may arise, like increased irritability or agitation. Also, symptoms may remain even after starting the medication.

Also, symptoms may remain even after starting the medication.

A regimen of polypharmacy — taking several medications to manage one condition — might be started.

If you or your child are experiencing side effects, a second drug may be prescribed to help manage them. A separate drug might also be suggested for each individual symptom.

For example, a stimulant might be given for inattention, an SSRI for depression or anxiety, and an antipsychotic for aggression.

Polypharmacy can be useful, but it can sometimes cause adverse drug interactions. Be aware of each medication being prescribed, and why. Make sure both you and all your caregivers know the potential side effects or drug interactions to watch out for.

Whether you’re the caregiver of an autistic child or an autistic adult, you’re not alone. There are many social services, community education programs, and other resources available to help you.

Here are some tips for finding the services you need:

- Your doctor, local health department, or school can provide information about special programs or resources.

You can find resources near you through the Autism Society.

You can find resources near you through the Autism Society. - Your local chapter of the National Autism Association can also provide help and resources.

- If you need help with employment and career issues, you can visit the U.S. Department of Labor autism resource list.

- You can find an autism support group where you can share information and learn about treatment options and programs.

- During meetings with school staff and medical professionals, consider taking detailed notes. These will help you make decisions about treatment along the way.

- It’s a good idea to keep any copies of medical reports or evaluations. These will be helpful when you apply for special programs.

Drug load is a problem for people with autism

06/09/17

Many children and adults with autism take many drugs at the same time, which can lead to serious side effects and may not even be effective

Source: Spectrum News

Connor was diagnosed with autism early at the age of 18 months. Even at that age, his condition was obvious. “He would arrange things in rows, turn lights on and off non-stop,” says his mom, Melissa. He was bright, but did not speak until he was 3 years old and quickly lost his temper. When he went to school, he couldn't sit at his desk, shouted out answers without raising his hand, and freaked out when he didn't understand something in math or couldn't write by hand at the same speed as everyone else. “One day he wrapped himself in a carpet like a roll and refused to come out until I arrived at school,” recalls Melissa.

Even at that age, his condition was obvious. “He would arrange things in rows, turn lights on and off non-stop,” says his mom, Melissa. He was bright, but did not speak until he was 3 years old and quickly lost his temper. When he went to school, he couldn't sit at his desk, shouted out answers without raising his hand, and freaked out when he didn't understand something in math or couldn't write by hand at the same speed as everyone else. “One day he wrapped himself in a carpet like a roll and refused to come out until I arrived at school,” recalls Melissa.

Connor was prescribed his first psychiatric drug, methylphenidrate (Ritalin), when he was 6 years old. The drug did not last long, but at the age of 7, the parents tried again. The psychiatrist suggested a low dose of dextroamphetamine (Adderall), a psychostimulant used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The drug markedly improved his behavior at school: now he could sit at his desk longer and follow what the teachers were saying. His handwriting "like a chicken's paw" became legible. Then his handwriting became neat. Then perfect. And then he became the subject of Connor's obsession.

His handwriting "like a chicken's paw" became legible. Then his handwriting became neat. Then perfect. And then he became the subject of Connor's obsession.

“We were told that there would always be pros and cons. The drug helped him get through a day of school and we thought it was worth it,” says Melissa. And he was worth it. For some time.

But when Adderall's action ended at the end of the day, Connor felt worse than ever. During the day he wept and refused to do anything. Because of the psychostimulant, it became difficult for him to fall asleep in the evening. So after a month or two, the psychiatrist added a second drug, guanfacine (Intuniv), to treat ADHD, anxiety, and hypertension, which can also reduce insomnia. The psychiatrist hoped this would ease Connor's daytime and help him sleep.

In a sense, the effect was the opposite. During the day he began to feel better, but Connor developed very severe mood swings and was so irritated every evening that he was very difficult to deal with. And now, instead of just tossing and turning in bed, he began to categorically refuse to go to bed. “He didn’t go to bed because he was always angry about something,” says Melissa. “He worked himself up and couldn’t stop, every night he got upset and started crying.”

And now, instead of just tossing and turning in bed, he began to categorically refuse to go to bed. “He didn’t go to bed because he was always angry about something,” says Melissa. “He worked himself up and couldn’t stop, every night he got upset and started crying.”

Seven months later, the parents said that it was simply impossible to continue taking this combination. They replaced guanfacine with over-the-counter melatonin, which helped Connor sleep better without any visible side effects. However, a year later, he developed a tolerance for Adderall. Connor's psychiatrist increased the dosage, and this, in turn, led to the development of tics: Connor began to jerk his head and sniffle. During a medical examination at the age of 9, the doctor noticed that over the past two years he had hardly grown. His weight had not changed at all since the age of 7, and now he was much lower than normal.

This is where the drug experiments stopped. The parents removed the child from all prescription drugs, and today, at almost 13 years old, Connor still does not take any medication. His tics are almost gone. Although he still struggles to concentrate in class, his mom thinks the risks outweigh the benefits, and she's against new drugs. “If we can somehow manage without drugs, then we will manage without them.”

His tics are almost gone. Although he still struggles to concentrate in class, his mom thinks the risks outweigh the benefits, and she's against new drugs. “If we can somehow manage without drugs, then we will manage without them.”

Connor is just one of many, many children with autism who are being prescribed multiple drugs at the same time. Phoenix started taking risperidone (Risperdal) at just 4 years old. This drug has been approved for the treatment of irritability in autism. He is now 15 years old and has experience with over ten different psychiatric medications. Ben is 34 and has autism but has been misdiagnosed with other disorders in the past. He was in middle school when his mother insisted that he start taking drugs for depression and behavioral problems. The doctor tried one antidepressant after another, but nothing worked. In high school, at age 15, he was misdiagnosed as having bipolar affective disorder and was prescribed an anticonvulsant drug and an antidepressant.

It is not uncommon for children with autism to take two, three, or even four drugs at the same time. The same is true for many adults with autism. There are not enough statistics on this subject, but the limited information currently available suggests that adults with autism are even more likely to be prescribed multiple drugs than children.

Specialists are particularly concerned about prescribing psychiatric drugs to children because such drugs can have unwanted effects on brain development and are rarely tested on children.

In general, polypharmacy—taking more than one drug at the same time—is very common among people with autism. One study found that among 33,000 people with autism under the age of 21, at least 35% were taking two psychotropic drugs at the same time, and 15% were taking three drugs.

“Psychotropic drugs are so commonly prescribed for people with autism because there are few treatment options,” says Lisa Kroen, director of the Autism Research Program at Kaiser Permanente in California. - Is such a drug load bad? This question is difficult to answer. We just don't know - no research has been done."

- Is such a drug load bad? This question is difficult to answer. We just don't know - no research has been done."

Sometimes, as in Connor's case, a second drug is given to treat side effects of the first. Most often, doctors prescribe drugs for each individual symptom - a psychostimulant for concentration, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) for depression, an antipsychotic for aggression, and so on. (Children with autism who also have epilepsy take anticonvulsant drugs. But since such drugs are effective and available, they are usually not considered part of the polypharmacy problem.)

“Kids come to me on Zoloft, Depakota and risperidone,” says Matthew Siegel, professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at Tufts University in Medford, Massachusetts. Zoloft is an antidepressant, Depakot is a mood stabilizer, and risperidone is an antipsychotic. Three psychotropic drugs per patient.”

In other cases, due to moves, changes in insurance, or dissatisfaction with treatment, people on the spectrum end up with many different doctors, each with their own opinion, who may add a new drug but not remove the old one.

Why is there such confusion? Because there is no single drug for the treatment of autism itself.

There are so-called key characteristics of autism - repetitive behaviors, difficulties with social interaction and impaired communication. Behavioral therapy can help with these three characteristics, but no drug can change them. Those drugs that are prescribed to people with autism are the treatment of peripheral problems that greatly complicate life - ADHD, irritability, anxiety, aggression, self-aggression.

The current practice that leads people to take cocktails of psychotropic drugs can be ineffective and harmful. Each doctor decides for himself what will be effective and safe, because there are simply no studies. “We have so few single drug studies, so few studies comparing different drugs alone,” says Brian King, professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco. “We still have a lot to learn before we even get to research into different combinations of drugs. ”

”

Datura drug

The US Food and Drug Administration has approved only two drugs for children and adolescents with autism: risperidone and aripiprazole. Both are atypical antipsychotics and are prescribed to treat behavioral problems associated with increased irritability, for example, if a child has aggression, tantrums, and self-aggression. These drugs relieve such problems in about 30-50% of cases - they do not help the rest.

This is a huge gap: psychiatric problems are common in children with autism. A 2010 study found that 80% of children with autism who presented to a mental health center also had ADHD, 61% had at least two anxiety disorders, and 56% had clinical depression.

Multiple diagnoses lead to drug cocktails, but there are no clinical trials for drug combinations, so in most cases it is not known how different psychotropic drugs interact with each other. "Each drug has its own side effects, and when you prescribe a mixture of them, you are effectively prescribing a new drug that has not been studied," says King. “And if we are talking about autism, when there can be severe communication disorders, then the risks are even greater, because it is difficult for patients to tell you that they feel bad from your drugs.”

“And if we are talking about autism, when there can be severe communication disorders, then the risks are even greater, because it is difficult for patients to tell you that they feel bad from your drugs.”

What's more, researchers say these drugs may not work at all for people with autism.

“Many studies have examined the use of drugs to treat ADHD in people with autism. The same is true for drugs to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder and repetitive behaviors, says Daniel Couri, a pediatrician at the National Children's Hospital in Columbus, Ohio. “And virtually all of these studies have shown that these drugs are much less effective for people with autism than for people without autism.”

These studies are relatively rare and were mostly uncontrolled. In 2013, a meta-analysis of existing studies found that most studies of psychiatric drugs for autism are either too small or poorly designed to tell if the drugs are effective. The existing data, the researchers write, “can only be considered speculation that needs to be evaluated in well-controlled studies. ”

”

The symptoms of depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, ADHD and other psychiatric conditions seem to be the same in people with and without autism. But the causes of autism are very different, which means that the biochemical processes behind them can differ and vary from person to person.

"It's a huge problem with treating autism in general," Siegel says. Autism is caused by so many genetic variations that the condition of each individual can be unique, which means that treatment must be individualized. Even in ideal conditions of clinical trials, the drug can only help 20% of people. The antipsychotics aripiprazole and risperidone stand out because they can be as effective as 50%. “50% is like a record in this area,” Siegel says.

Paradoxically, another reason children and adults with autism may be given different drugs, as in the case of Connor, is that doctors use the second drug to reduce the side effects of the first. Antipsychotics, for example, can lead to weight gain and metabolic disorders, as well as involuntary muscle contractions. Some doctors add metformin for weight gain and benztropine (Cogentin) to relieve involuntary movements.

Some doctors add metformin for weight gain and benztropine (Cogentin) to relieve involuntary movements.

But every new drug brings its own potential side effects. Metformin can cause muscle pain and, less commonly, anxiety and nervousness. Benztropine can lead to confusion and memory problems. Physicians with little experience in treating patients with autism may mistake side effects for new symptoms and prescribe new drugs in response. In the vast majority of cases, psychotropic drugs are prescribed by doctors with little or no experience with autism, Siegel says. "People just don't know what they're doing, so it's not surprising that kids end up taking multiple drugs."

Toxic Pills

As a preteen, Ben had problems typical of a child with autism: social anxiety, difficulty communicating with peers, mild depression, violent temper tantrums, inattention, and disruptive behavior in class. When he was 12 years old, school testing revealed he had sensory processing problems and dysgraphia (problems with handwriting), but not autism. At the mother's request, the doctor tried an antidepressant. It didn't help and only led to headaches. A new antidepressant followed, and then another. The side effects weren't worth taking, so Ben got a short break from his medication.

At the mother's request, the doctor tried an antidepressant. It didn't help and only led to headaches. A new antidepressant followed, and then another. The side effects weren't worth taking, so Ben got a short break from his medication.

Two years later, when he was 16 years old and his problems at school and at home were getting worse, his mother again insisted on medication. A new doctor prescribed a newly approved SSRI, citalopram (Celexa), recommending that Ben and his mother see a specialist. But for a year, life was too busy to look for a specialist, and Ben just took citalopram.

Over the next year, the situation at the school got worse and worse. Ben was bullied more and more often by his classmates, he increasingly responded to them with aggression, so his mother finally took him to a psychotherapist. He diagnosed Ben with bipolar affective disorder and referred him to a psychiatrist with a recommendation to add valproic acid (Depakote) to his drugs. Ben recalls that the psychiatrist asked him a couple of questions, and then simply gave him a prescription for the two drugs that the therapist asked for. Ben's autism was never diagnosed.

Ben's autism was never diagnosed.

“That's when things really changed,” says Ben. He gained a lot of weight. He couldn't concentrate in class. He made scenes at school and at home, his anxiety reached a new peak. “My behavior has become more aggressive and unpredictable,” he says. In the middle of the night, he would wake up terrified, and then just walk in circles around the room. “I don’t think that such an escalation would have happened without drugs,” he said. He started fighting with his father. “I fell into complete despair, sobbed, I could punch a hole in the wall with my fist.”

Five drugs and five psychiatrists later, Ben became lethargic, irritable, angry and unable to concentrate on anything.

Finding a combination of drugs is especially difficult if the attending physician changes all the time. In Ben's case, not only was he misdiagnosed, but the family moved twice. In addition, his psychotherapist and psychiatrist did not discuss his diagnosis and treatment with each other. In other cases, people may not have access to doctors who understand autism. Some people change doctors hoping to find an approach they like, or are forced to do so because of insurance changes. The list of drugs is growing due to "the lack of one person responsible for the entire treatment process," says Shafali Jeste, a pediatric neurologist at the University of California, Los Angeles: "In our city, this happens all the time."

In other cases, people may not have access to doctors who understand autism. Some people change doctors hoping to find an approach they like, or are forced to do so because of insurance changes. The list of drugs is growing due to "the lack of one person responsible for the entire treatment process," says Shafali Jeste, a pediatric neurologist at the University of California, Los Angeles: "In our city, this happens all the time."

The stack of prescriptions may become thicker as the child transitions from adolescence to adulthood.

"People who are prescribed drugs often stay on them for long periods of time and don't even try to determine if they still need them," says David Posey, a psychiatrist in Indianapolis, Indiana. It is usually recommended to review the drug regimen at least once a year, to evaluate the possibility of reducing the dosage, but this is not always possible. "If the drug worked, families might be against trying to take it off."

Jeste says that her clinic is often visited by people with a long list of drugs, but without a well-formed medical record and anamnesis, and it is sometimes impossible for her and her colleagues to understand why a particular drug was ever prescribed and whether it helps. In these cases, she gradually reduces the dosage of one drug after another.

In these cases, she gradually reduces the dosage of one drug after another.

Ben was not lucky enough to find such a specialist. By the end of his last year at school, he fell asleep in class and felt so bad that he dropped out. “Then my parents were getting divorced,” Ben recalls that time. “There was complete chaos around, I was losing all my support, I was losing my usual daily routine, I started sleeping in the car.”

He started smoking marijuana, which he said made him euphoric when combined with antidepressants. But at the same time, she helped him function. “It helped me connect with people better than drugs,” he says. Ben says marijuana helped him better understand how psychiatric drugs work on him, and that they cause the same mood swings, just much more slowly. "I had the idea that maybe the mood cycles I often experience coincide with the drug use."

At the age of 21, he made the decision to get rid of both illegal drugs and prescription drugs. A year later, he was diagnosed with autism. Now he has learned to step aside and take deep breaths every time he feels a fit of anger coming on. No more holes in the wall. He goes for a run six times a week, and physical activity helps him stay calm, clear and focused. Autism may have been responsible for the initial mood swings and aggression, but he says the drugs are a vicious circle.

Now he has learned to step aside and take deep breaths every time he feels a fit of anger coming on. No more holes in the wall. He goes for a run six times a week, and physical activity helps him stay calm, clear and focused. Autism may have been responsible for the initial mood swings and aggression, but he says the drugs are a vicious circle.

Treatment

Multiple medications are not always a bad thing. Some children have very serious problems in their lives, their behavior can pose a serious threat to themselves and others, and in these cases, medication may be the only way out.

Phoenix was one of those children. “He was a little tornado,” his mom says. One day in early 2007, she received a call from the kindergarten asking her to pick him up early because he was being very aggressive, knocking over tables and chairs for no apparent reason. He escaped twice that day - once he jumped out of the car on the way home, then climbed out of the bedroom window. The police found him in the middle of a busy highway. He was only four years old.

The police found him in the middle of a busy highway. He was only four years old.

Sally, Phoenix's mother, says he has always been a difficult child. But when his mood swings escalated into aggression, he could lash out at people and try to harm his older brother, who also had autism. “He was strong beyond his years,” she says. She knew that at all costs she must help him deal with his anger, for the safety of both boys.

His doctor tried risperidone, then added guanfacine and Adderall. However, this did not affect his aggression. Sally recalls that every morning she and her husband woke up, looked at each other and said: “How is Phoenix now?” After that, "everything inside her froze." It was obvious that drugs needed to be selected, but the family could not cope with him at home. When Phoenix was 6 years old, he was first admitted to the hospital.

By 2009, his clinic had already changed psychiatrists twice. The new psychiatrist replaced Adderall with Vyvans. A blood test then showed that Phoenix had an increased risk of developing breasts, a serious but rare side effect of risperidone called gynecomastia. The psychiatrist changed risperidone to Seroquel. “It was a disaster,” Sally says. Phoenix climbed out of the windows, got up and walked around the classroom, attacked his brother for no reason. None of the drug combinations alleviated the aggression and mood swings. Aude

The psychiatrist changed risperidone to Seroquel. “It was a disaster,” Sally says. Phoenix climbed out of the windows, got up and walked around the classroom, attacked his brother for no reason. None of the drug combinations alleviated the aggression and mood swings. Aude

The case shocked the whole family and ended with a new hospitalization and a new drug combination. The doctors replaced Seroquel with another neuroleptic, Geodon, and also prescribed valproic acid and guanfacine. Since Phoenix's brother, Mack, was greatly helped by Strattera's anti-ADHD drug, the hospital staff replaced Vyvans with Strattera.

Phoenix has been in four different inpatient programs, been hospitalized six times, tried more than a dozen drugs, sometimes four at a time. Hospitalizations helped to take him off certain drugs and gradually introduce others that, at least temporarily, controlled his mood swings. But every time after he was discharged, the drug combinations stopped working and he returned to aggression, mostly against his brother. The first two stationary programs did not help at all. They created stability and structure in his life: every day was the same, the daily routine was very reliable. But the programs could not adjust the drug regimen. And when he returned home, where such a tough regime no longer existed, he began to attack his brother. "We've had holes in our doors from the time Phoenix tried to get to Mac," she says.

The first two stationary programs did not help at all. They created stability and structure in his life: every day was the same, the daily routine was very reliable. But the programs could not adjust the drug regimen. And when he returned home, where such a tough regime no longer existed, he began to attack his brother. "We've had holes in our doors from the time Phoenix tried to get to Mac," she says.

The next two programs focused on children with autism, and they provided the necessary assistance to Phoenix. He was 12 when he entered the third program and began taking an antipsychotic commonly prescribed for bipolar disorder, olanzapine (Zyprexa). And in the fourth inpatient program, when he was 13 years old, doctors found what seemed to be the perfect combination: olanzapine, valproic acid, guanfacine and atomoxetine. He spent weekends at home, but lived at a nearby facility for a week, where he also received behavioral therapy and social adjustment support. “For the first time when he came home, we really enjoyed his company, we were able to see what a real Phoenix is,” says Sally.

But a common side effect of Zyprexa is weight gain, and the drug made Phoenix constantly hungry. “On weekends, he emptied the refrigerator at three in the morning,” she says. The overly thin boy began to suffer from obesity. “He looked like a balloon about to burst,” his mother says. He was sitting and he was short of breath. We had to take it off the Zyprexa."

His doctor took him off Zyprexa and put him on another antipsychotic and then another (Seroquel) until the combination started to work.

Phoenix is now 15 years old, on four drugs and has been stable for over a year. His mood is also stable. “The aggression is gone,” Sally says. He developed a sense of humor and started watching TV with his family and discussing what he saw with them. He also began to develop the capacity for empathy. Now, if he sees that a child at school is behaving the same way as he once did, he says to his brother: "I must apologize to you and mom." According to Sally: “He saw himself from the outside, and it affected him very much. One day, for no reason, he came into the kitchen and said: "You know, mom, I love you." He never said that."

One day, for no reason, he came into the kitchen and said: "You know, mom, I love you." He never said that."

When new symptoms appear, the temptation to change medications can be very strong, especially with a difficult treatment history where parents are used to thinking about the drug approach first. But very often new problems can be solved with simple methods.

This fall, Phoenix began to fall asleep in class during the day. One of the previous drugs had had the same effect on him - he was so sleepy that he could fall asleep even during lunch in a noisy restaurant. Sally was very worried. She was afraid that this meant that the effect of the psychostimulant was ending, or this was some new side effect. She did not want to change the already established treatment regimen.

Before taking him to the doctor, she decided to investigate. She bought a device to restrict and monitor her home Wi-Fi network. It turned out that Phoenix got up at night and spent hours playing on the computer. She started turning off the Internet at night, and Phoenix immediately became alert during the school day.

She started turning off the Internet at night, and Phoenix immediately became alert during the school day.

“It's not uncommon for children to take more than one drug. The question is: do people just try everything in the hope that it will help, or is there some kind of rational justification? says Lawrence Scahill, director of clinical trials at the Marcus Autism Center at Emory University. When treatment decisions are made carefully and with a very clear goal in mind, drug combinations can be very helpful. Under these circumstances, Scahill believes, "we can talk about the so-called rational polypharmacy."

The path of the Phoenix, although very thorny, led him to favorable results. This is an example of how polypharmacy, with care, attention and perseverance, can help people with autism live fulfilling lives.

However, the decision to take drugs always depends on the individual doctor, individual family, individual person. "Every time it's an experiment, but it's not a controlled experiment," Scahill says. Ben, Phoenix and Connor: Each of them faced different problems with no ready-made solutions, because prescribing drugs for autism is still more art than science. There are still no clear rules, and one can only hope that they will nevertheless appear.

Ben, Phoenix and Connor: Each of them faced different problems with no ready-made solutions, because prescribing drugs for autism is still more art than science. There are still no clear rules, and one can only hope that they will nevertheless appear.

See also:

Does a child with autism need to take medication?

Autism treatment - present and future

Autism and mental health

We hope that the information on our website will be useful or interesting for you. You can support people with autism in Russia and contribute to the work of the Foundation by clicking on the "Help" button.

Methods and treatment, Psychiatry

Elon Musk admitted that he had Asperger's syndrome

- Billionaires

- Timur Batyrov Editorial Forbes

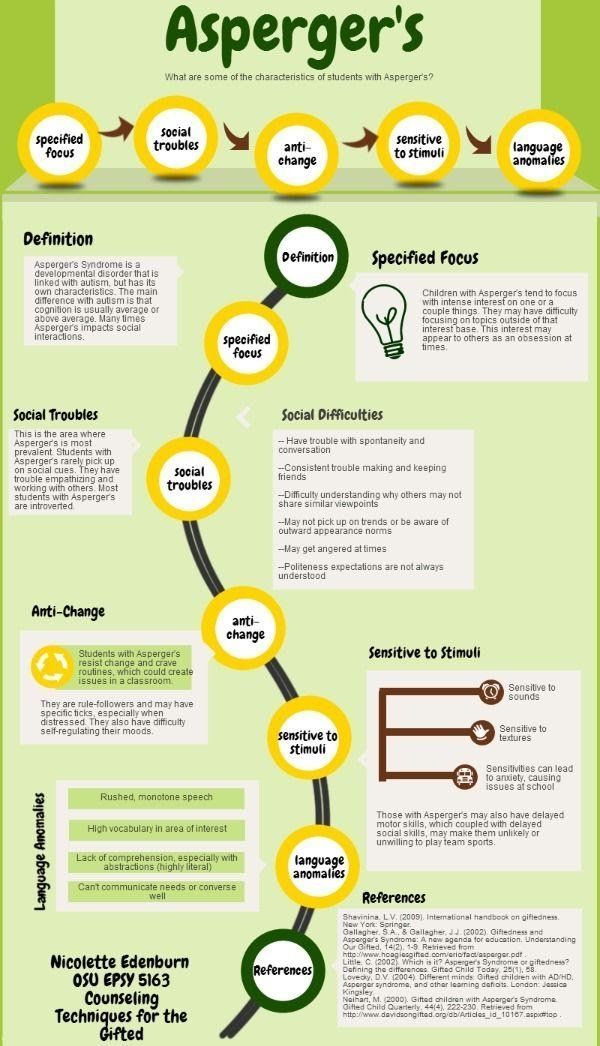

Billionaire Elon Musk admitted that he has Asperger's syndrome. This is an autism spectrum disorder whose carriers have difficulties with communication and socialization, but they often have increased cognitive and verbal abilities. He stated this on the air of the Saturday Night Live television program on NBC, which he hosted.

“I'm honored to host Saturday Night Live. <...> My performance today is historic because I am the first SNL host with Asperger's. Or at least the first one to admit it,” Musk said.

"Elon's tweet doesn't match reality": Tesla doubts the possibility of releasing a drone by the end of the year In 2003, a former TV show participant, actor and comedian Dan Aykroyd, who repeatedly spoke about having Asperger's syndrome, became the host of one of the editions of Saturday Night Live, the Daily Beast notes.

Asperger's Syndrome is an autism spectrum disorder. Its owners have difficulties with communication and socialization, but they often have increased cognitive and verbal abilities. Billionaire PayPal founder Peter Thiel noted that many successful entrepreneurs have a "mild form" of this syndrome, or traits of it. According to him, they allow you to create real innovations in a conformist environment, not paying attention to social conventions.

“Look, I know I sometimes say and write weird things, that's how my brain works. To everyone I offended, I want to say the following. I reinvented electric cars and send people to Mars, you thought I would be a calm and normal dude?” Musk said in his welcoming speech.

Elon Musk became the highest paid CEO in the US

Musk was announced to host an episode of Saturday Night Live in April.