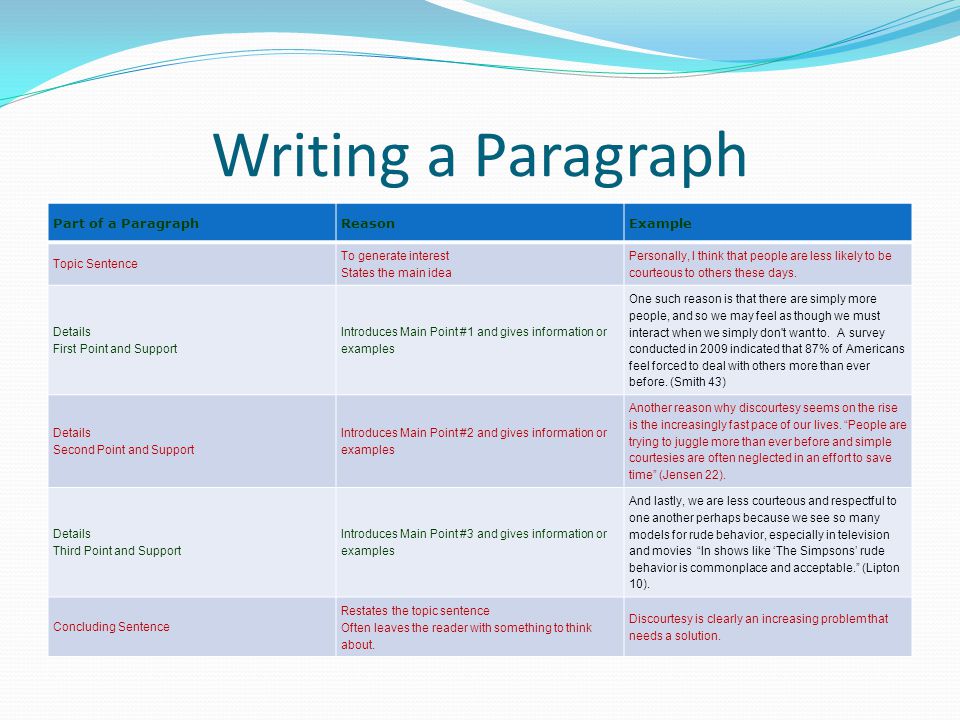

Why do people follow the crowd

Middle Ground Essay: The Effect of Others

Middle Ground Essay: The Effect of Others

We spend our lives watching and responding to each other.

Spend time in any public space watching the crowds and you’ll see examples of what scientists call social influence—the varied ways people change their behavior because of the presence of others. Notice how individuals respond to orders and requests, go along with a group, mirror the actions of others, compete, and cooperate. We are finely tuned to the people around us, relying on each other for cues about how to behave so that we can efficiently navigate our social environments. The influence of others is so pervasive that we can experience it even when there is no real person there: we’ll adjust our behavior in response to an implied presence (say, a security camera and a No Trespassing sign) or an imagined one (“What would my mother say?”).

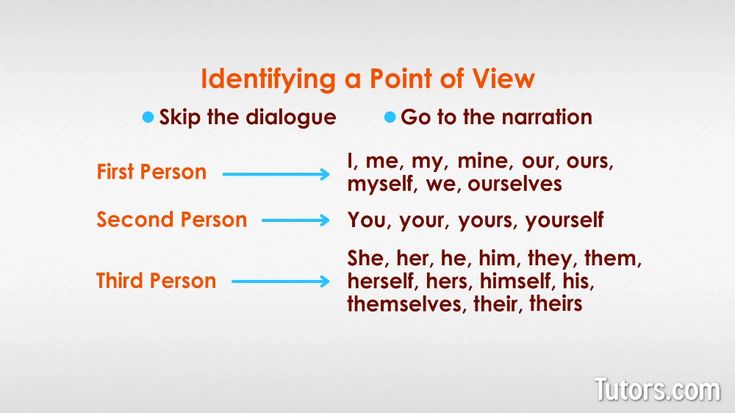

Social influence

Conformity

You’ve almost certainly experienced it: unsure what to do in a situation, you look around to see what others are doing, and change your behavior to match.

Do you always follow the crowd?

Do you always follow the crowd?

Most of us don’t like to be called conformists (at least in Western societies, where individuality and uniqueness are prized), but going along with the crowd is a natural and often useful tendency. Humans evolved to live in groups; since early on, we’ve needed ways to smooth interactions, reduce conflict, and coordinate action. For example, traffic flows better—and more safely—if cars all drive in the same direction and pedestrians all cross the street together. Conforming to the group can be a matter of survival.

Middle Ground: Don't Push This Button

Do you usually follow orders or rules, or ignore them? INTERACTIVE

The smoke filled room study

The tendency to conform has two different roots. Sometimes, in confusing situations, we assume that other people know more than we do, so we follow their lead. That assumption might be right—but often it’s not. Say you’re walking by a building and see smoke coming out. Do you call 911? If other people look unconcerned, you might decide it’s not an emergency. But others may decide not to phone for help because you don’t look concerned. Scientists call this potential misinterpretation by a group pluralistic ignorance. It can lead to the bystander effect, where no one from a crowd steps forward to help in a situation where action is needed. It’s a paradox: the more people who witness an emergency, the less chance that any of them will act, because they’re all conforming to the group’s behavior.

Sometimes, in confusing situations, we assume that other people know more than we do, so we follow their lead. That assumption might be right—but often it’s not. Say you’re walking by a building and see smoke coming out. Do you call 911? If other people look unconcerned, you might decide it’s not an emergency. But others may decide not to phone for help because you don’t look concerned. Scientists call this potential misinterpretation by a group pluralistic ignorance. It can lead to the bystander effect, where no one from a crowd steps forward to help in a situation where action is needed. It’s a paradox: the more people who witness an emergency, the less chance that any of them will act, because they’re all conforming to the group’s behavior.

In which situation is the person in distress more likely to get help from a bystander?

Middle Ground: Stand By or Step Up?

What do you do when a stranger needs help? INFOGRAPHIC

The other reason people conform and go along with the crowd is that we all want to be liked and accepted. The desire to fit in is so strong that people sometimes conform to a group consensus even when it goes against their own judgment—at least in public. In private, they’re much more likely to follow their own minds.

Compliance

When the pressure from others gets more explicit, conformity blends into another type of social influence: compliance, when we respond to a direct request made by someone else.

Are you more likely to comply with a request made by someone wearing a uniform?

Are you more likely to comply with a request made by someone wearing a uniform?

Social scientists have identified various compliance strategies, and you may be using some of them—or have been the target of them—without being aware of it. For example, if someone asks for a very small favor (“Can you tell me how to get to the library?”), and you comply, you’re more likely to agree with a second, larger request (“Oh no, that’s farther away than I thought—can you spare two bucks for the bus?”). This is called the foot-in-the-door technique. It works because complying with the first request shapes or reinforces our self-image (“I’m a helpful person!”), providing us with a rationale for agreeing to the second request (“That’s who I am—I help out when needed.”).

For example, if someone asks for a very small favor (“Can you tell me how to get to the library?”), and you comply, you’re more likely to agree with a second, larger request (“Oh no, that’s farther away than I thought—can you spare two bucks for the bus?”). This is called the foot-in-the-door technique. It works because complying with the first request shapes or reinforces our self-image (“I’m a helpful person!”), providing us with a rationale for agreeing to the second request (“That’s who I am—I help out when needed.”).

The Power of a (Bogus) Uniform

Obedience

When pressure from others gets even stronger, it can lead to obedience—when we respond to a demand issued by an authority figure. The world is full of orders given by people who have power over us, either in person (the boss, a cop, your parent) or via written words (as on road signs). The pressure to conform in such situations can be extreme, and obedience can have a dark side. In one famous experiment, a researcher set up a situation where subjects had to decide whether to follow orders to inflict pain on another person. The disturbing results showed how hard it is for people to resist authority.

The disturbing results showed how hard it is for people to resist authority.

This experiment was done decades ago, in a different social time. Would today’s generation, supposedly more critical and less trusting of authority, respond the same way? Scientists recently ran a modified version of the study. The test subjects reacted similarly, confirming the powerful role of social influence.

People in groups

Social loafing

Pulling Together

Working together, do you pull your weight?

Social influence also plays an important role when people work in groups. Much of this influence is direct or intentional—for example, we often work harder because our co-workers are depending on us to meet a deadline. But sometimes the mere presence of others can shape our behavior: As work groups grow larger, individual group members tend to decrease the effort they put in, especially when their individual contribution can’t be identified. This tendency is called social loafing. One of the first people to study social loafing was a French agricultural engineer who noticed that adding more farm workers to a job didn’t increase productivity as much as expected. In the early 1900s, he ran a series of simple experiments, having men pull carts either alone or together. In theory, two men should pull twice as much weight as a single man (200%). Instead, he found that together they pulled only 186% of the weight—each man pulled less than he had alone. The more men on the job, the less each one pulled individually.

One of the first people to study social loafing was a French agricultural engineer who noticed that adding more farm workers to a job didn’t increase productivity as much as expected. In the early 1900s, he ran a series of simple experiments, having men pull carts either alone or together. In theory, two men should pull twice as much weight as a single man (200%). Instead, he found that together they pulled only 186% of the weight—each man pulled less than he had alone. The more men on the job, the less each one pulled individually.

How hard would you pull? Would you work harder if you knew that others could tell how hard you pulled?

How hard would you pull? Would you work harder if you knew that others could tell how hard you pulled?

This tendency has been documented many times since, in various situations. It's affected somewhat by culture and circumstance—for example, workers from societies where interdependence is the norm tend to loaf less than those from more individualistic cultures—but it’s still universal. Does this mean that people are slackers? Not necessarily. When many hands are making light work, it’s reasonable to ease up a bit—as long as things are kept fair and everyone reduces their effort by the same amount. And there’s a certain logic to holding back if you believe your contribution isn’t important, or if it can’t be seen and recognized.

Does this mean that people are slackers? Not necessarily. When many hands are making light work, it’s reasonable to ease up a bit—as long as things are kept fair and everyone reduces their effort by the same amount. And there’s a certain logic to holding back if you believe your contribution isn’t important, or if it can’t be seen and recognized.

But when only some people loaf, the whole group suffers and its chances of success decrease. Voting in elections is one example. There are many reasons why people don’t vote, but social loafing can contribute to the problem. If you think that enough other people will vote and that the outcome will be fine without your participation, or that your vote doesn’t really matter, that might be enough to keep you away from the polls.

Given the potential problems with social loafing, how can we limit it? Social scientists have identified several effective strategies:

- Make personal efforts identifiable

- Ensure each person feels their effort is important

- Highlight that personal efforts will improve group performance

- Increase team spirit

Quick vs. slow thinking

slow thinking

We pay close attention to others, and often follow their lead. It’s natural to go along with a group—and there can be wisdom in crowds.

But before you follow, think for a minute. Where is the crowd headed? Would you go there on your own if the group wasn’t drawing you along?

Further Reading

Keshia Naurana Badalge (2017). “Our Phones Make Us Feel Like Social-Media Activists, But They're Actually Turning Us Into Bystanders.” (article)

Jerry M. Burger (2009). “Replicating Milgram: Would People Still Obey Today?” American Psychologist, 64(1), 1–11. (abstract)

Robert B. Cialdini (2007). Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion. (book)

Steven J. Karau and Kipling D. Williams (1993). “Social Loafing: A Meta-Analytic Review and Theoretical Integration." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 65(4): 681–706. (abstract)

D.A. Kravitz and B. Martin (1986). "Ringelmann Rediscovered: The Original Article. " Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(5): 93–941. (abstract)

" Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50(5): 93–941. (abstract)

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1713638. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

The Science Behind Why People Follow the Crowd

Source: Neko1998/Flickr

It may seem that we are in control of our thoughts and behavior. But social psychology tells a different story.

Social psychology is defined as “the scientific study of how we think about, influence, and relate to one another." We are social beings. Most of us communicate with others every day, spending large portions of our waking hours in some form of communication.

One lesson from social psychology is the influence others have on us. Research shows we do not have as much control over our thoughts and behavior as we think. We take cues from our environment, especially other people, on how to act.

We take cues from our environment, especially other people, on how to act.

How groups influence us

Consider the concept of group polarization. The idea is that likeminded people in a group reinforce one another’s viewpoints. Group polarization strengthens the opinions of each person in the group.

In a study by French psychologists Serge Moscovici and Marisa Zavalloni, researchers asked participants some questions. First, researchers asked about their opinion of the French president. Second, they asked about their attitude toward Americans. The researchers then asked the participants to discuss each topic as a group.

After a discussion, groups who held a tentative consensus became more extreme in their opinions. For example, participants held slightly favorable attitudes toward the French president. But their attitudes magnified as group members spoke with one another. They held slightly negative attitudes toward Americans. But their attitudes intensified as each member learned others shared their views about their allies abroad. The researchers concluded, “Group consensus seems to induce a change of attitudes in which subjects are likely to adopt more extreme positions." When we see our uncertain opinions reflected back to us, our beliefs strengthen.

The researchers concluded, “Group consensus seems to induce a change of attitudes in which subjects are likely to adopt more extreme positions." When we see our uncertain opinions reflected back to us, our beliefs strengthen.

Many of us also enjoy being with others who share similar beliefs. In one experiment, researchers invited people to discuss issues including same-sex marriage, affirmative action, and climate change. People in one group came from predominantly liberal Boulder, Colorado. People in another group came from mostly conservative Colorado Springs. The discussions on controversial topics led to increased agreement within the groups. Beliefs we hold are strengthened when we are around others who hold similar views.

If other people do it, that means it’s right. Right?There is a heuristic most of us use to determine what to do, think, say, and buy: the principle of social proof. To learn what is correct, we look at what other people are doing. In his bestselling book Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, psychologist Robert Cialdini writes, “Whether the question is what to do with an empty popcorn box in a movie theater, how fast to drive on a certain stretch of highway, or how to eat the chicken at a dinner party, the actions of those around us will be important in defining the answer.” Social proof is a shortcut to decide how to act.

In his bestselling book Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, psychologist Robert Cialdini writes, “Whether the question is what to do with an empty popcorn box in a movie theater, how fast to drive on a certain stretch of highway, or how to eat the chicken at a dinner party, the actions of those around us will be important in defining the answer.” Social proof is a shortcut to decide how to act.

Cialdini has used the principle of social proof to prevent environmental theft. Consider the case of Arizona’s Petrified Forest National Park. Visitors would arrive at the park and learn of past thievery from prominent signs: “Your heritage is being vandalized every day by theft losses of petrified wood of 14 tons a year, mostly a small piece at a time.”

In one experiment, Cialdini removed the sign from a specific path in the park to measure any differences it might make. The path with no sign had one-third less theft than the path with the sign. Visitors interpreted the sign’s message as permission. Put differently, visitors thought it was “normal” to take small pieces of wood, because so much was stolen every year.

Put differently, visitors thought it was “normal” to take small pieces of wood, because so much was stolen every year.

Researchers have also used the principle of social proof to help people overcome their fears. In one study, Albert Bandura and his colleagues worked with a group of young children frightened of dogs. The children watched a four-year-old boy happily play with a dog for 20 minutes a day for four days. After the four day period, 67 percent of the children who watched the boy play with the dog were willing to enter a playpen with a dog. When the researchers conducted a follow-up study one month later, they found the same children were willing to play with a dog. Watching a little boy have fun with a dog reduced fear in children. They used the behavior of a boy playing with a dog as a model to change their own behavior.

Why do others influence us so much?Clearly, others affect our behavior. One reason for this is that we live in a complex world. We use the decisions of others as a heuristic, or mental shortcut, to navigate our lives. English philosopher and mathematician Alfred North Whitehead once said, “Civilization advances by extending the number of operations we can perform without thinking about them."

We use the decisions of others as a heuristic, or mental shortcut, to navigate our lives. English philosopher and mathematician Alfred North Whitehead once said, “Civilization advances by extending the number of operations we can perform without thinking about them."

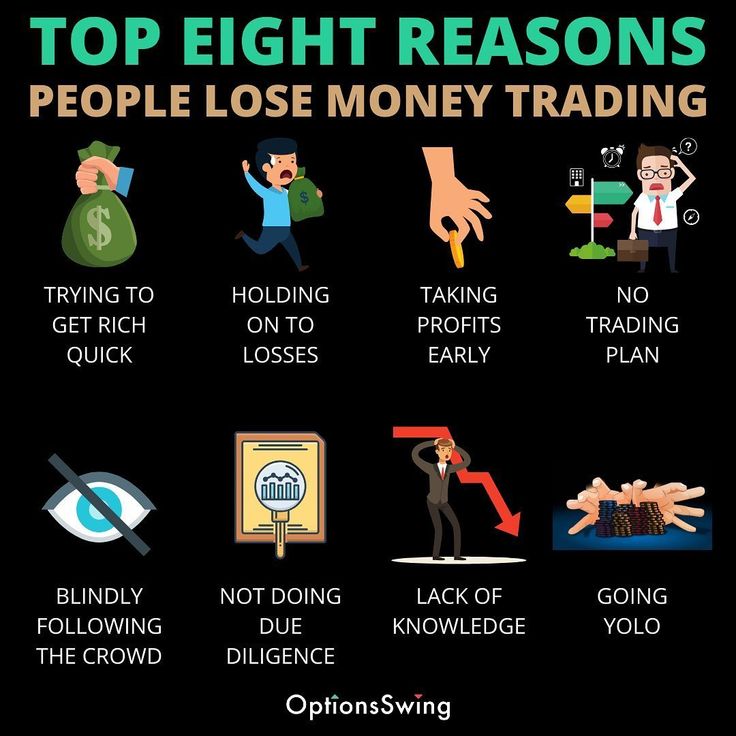

In his book Influence, Cialdini uses the example of advertisers informing us that a product is the “fastest-growing” or “best-selling.” Advertisers don’t have to persuade us that a product is good, they only need to say others think so.

Cialdini notes that consumers often use a simple heuristic: Popular is good. Following the crowd allows us to function in a complicated environment. Most of us do not have time to increase our knowledge of all merchandise and research every advertised item to measure its usefulness.

Instead, we rely on signals like popularity. If everyone else is buying something, the reasoning goes, there is a good chance the item is worth our attention.

A second reason others influence us is that humans are social. We have survived because of our ability to band together. Early humans who formed groups were more likely to survive. This affected our psychology.

We have survived because of our ability to band together. Early humans who formed groups were more likely to survive. This affected our psychology.

As Julia Coultas, a researcher at the University of Essex, puts it, “For an individual joining a group, copying the behaviour of the majority would then be a sensible, adaptive behaviour. A conformist tendency would facilitate acceptance into the group and would probably lead to survival if it involved the decision, for instance, to choose between a nutritious or poisonous food, based on copying the behaviour of the majority.”

In our evolutionary past, our ancestors were under constant threat. Keen awareness of others helped our ancestors survive in a dangerous and uncertain world. Modern humans have inherited such adaptive behaviors.

These behaviors include banding together and promoting social harmony. This includes not dissenting from the group. In a hunter-gatherer group, being ostracized or banished could have been a death sentence.

Thoughtful reflection on social influence may lead us to a greater awareness of ourselves and our relationships with others.

Majority Effect: Why We Go Stupid in Crowds

- Michael Bond

- BBC Future

Image credit: iStock BBC Future.

Most psychologists would never dream of experimenting with decision-making processes in a busy London pub, but from the Daniel Richardson, you can't think of a better place.

A researcher at University College London studies the influence of others on our thinking - for example, he is interested in how the behavior of others we observe influences our own choices in a given situation.

To do this, Richardson needs the subjects of his research to be in a situation of real communication, and not in a laboratory where subjects are usually isolated from each other.

(More BBC Future articles in Russian)

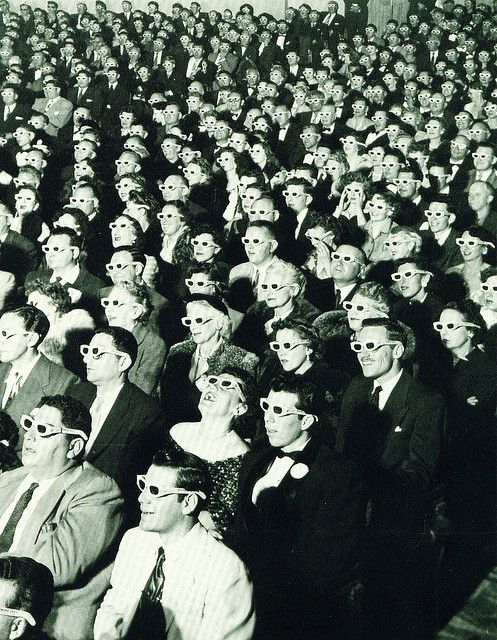

Tonight I joined a group of about 50 people at the Phoenix Arts Club in Soho, London.

We are taking part in one of Richardson's experiments. The establishment has a cheerful and friendly atmosphere; the experimenter standing in front of us with his shirt sleeves rolled up informally resembles an entertainer.

However, we are dealing with a serious scientific study. Each participant was given a password to access a website specially created for the experiment, which allows moving the dot-cursor across the screen of a personal smartphone.

This displays the cursor movements of all participants on a large wall-mounted TV screen. Thus, our collective decisions can be observed by everyone present - and Richardson keeps a record of the process for scientific purposes.

When all participants move their individual dots at the same time, it looks like a swarm of angry bees is moving across the screen.

After we learned how to control cursors, Richardson asks his first question: "Have you ever cheated on an exam?"

According to the conditions of the experiment, moving the cursor to the right side of the screen center means "yes", to the left - "no".

Photo Credit: Getty

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

End of story Podcast

First, we answer each question one by one: on the big screen, our cursor movements are not displayed. Then we do the same in the group.

Richardson wants to see if our answers are the same in both cases. In other words, do we give more honest answers when we answer without seeing the answers of others?

Then the main part of the experiment begins. Now we are offered to agree or disagree with a number of statements.

Now we are offered to agree or disagree with a number of statements.

"The UK should leave the EU," says Richardson. Almost all cursors on the wallboard flicker to the left: our answer is no.

"London Underground strikes should be banned by law." The swarm of cursors freezes in indecision - we are afraid to be the first to make a choice and hope to hide behind the backs of others.

"A person who treats friends in a restaurant has the right to take the largest portion for himself." There is a general hum of indignation, and the cursors rush to the left - a categorical "no".

But how many of us experienced a moment of hesitation when answering the same question individually?

Unfortunately, on the same evening, the results of the experiment are not made public to us - after analysis, they will be included in Richardson's doctoral dissertation.

However, the scientist assumes that eventually his experiments will demonstrate the detrimental effects of conformism.

Decisions made in a group tend to be more biased and less intelligent than those made individually.

"People interacting usually leads not to consensus, but to making the worst possible decisions," Richardson explains. decisions".

Richardson's research into conformity follows a tradition of experimental psychology that has been going on for more than 60 years.

Harvard psychologist in the 1950s Solomon Asch demonstrated that people often accept the majority view, even if it is obviously wrong, and even if they have to deny their own feelings in doing so.

Image copyright Dean Hochman Flikr CC BY 2.0

Around the same time Reed Tuddenham of the University of California found that his students give ridiculous answers to simple questions - say, they say that newborn boys have a life expectancy of 25 years - if they think their classmates before them answered the same way.

Group conformity is strikingly different from the "wisdom of the crowd" effect described in the book of the same name by the American financial analyst James Shuroviesky.

This effect lies in the fact that the generalized opinion of a large group of people allows you to give more accurate answers or predictions than the opinion of any individual member of the group.

This occurs only when crowd members make judgments independently of each other, and the greatest effect is observed in groups with a heterogeneous composition.

At the same time, in close-knit groups whose members share common values, the desire for collective unity prevails.

So when Richardson shows us a photograph of a killer whale and asks us how much we think the whale weighs, the swarm of cursors on the screen will give him a less accurate result than if he had taken the average of our individual responses.

At least that's what the theory says. The data from today's experiment will help Richardson and his students test this theory, as well as approach the more fundamental question of why our attitudes and cognitive processes change in the presence of other people.

Saying goodbye to us in the pub, Richardson shares his last thought about social media.

"We think the internet is an information highway. It's actually the highway that our misconceptions travel on. Twitter and Facebook are great communication tools, but it's possible that our urge to use them to spreading prejudice actually makes us all dumber."

Read original of this article in English is available on the website BBC Future .

Crowd Psychology: Myth and Reality

- David Edmonds

- BBC Radio 4 Presenter

to help you understand the events.

Copyright © iStock

Does crowd psychology research help policing?

The psychology of the crowd is a complex issue. Some believe that the crowd can easily become aggressive - after all, the mind and will of an individual person is lost in the general "herd mentality".

However, leading social psychologists involved in the study of crowd behavior believe that this traditional view is wrong.

"This perception of the crowd as something inherently aggressive is dangerous, not just because it is wrong, but because it may eventually become right. If we treat the crowd with such an idea, we only provoke it" - says social psychology professor Steve Reicher.

Of course, there are different types of crowds, and in order to control them, different approaches are needed.

Aggressive crowd

Of course, there is a violent type of crowd. Sometimes sports fans become aggressive.

For example, in the 70s and 80s of the last century, British football stadiums regularly became the site of hooligan skirmishes between fans of rival clubs.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,Clashes erupted between police and locals in the US city of Ferguson after police shot and killed an unarmed 18-year-old boy

Political rallies and demonstrations can also turn into pogroms and violence, although they usually begin quite peacefully.

There are also spontaneous riots, which usually break out because of some incident - for example, a murder committed by police officers.

Thus, the riots in Ferguson, a suburb of St. Louis, which occurred in August 2014, began after the police shot and killed black youth Michael Brown.

In Britain in August 2011, the murder of black Michael Duggan by policemen in north London provoked a wave of riots throughout the country.

Riots are not usually random, and it would be a mistake to write everything off as some kind of mass insanity.

Safe crowds

Despite popular belief that crowds are dangerous, Clifford Stott of Keele University in Staffordshire also points out that not all crowds are violent.

"The fact that we use terms of pathological conditions in relation to the crowd, the very idea that people in the crowd go berserk, does not make it possible to realize the true nature of such behavior," says Stott.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,The Glastonbury Festival is one of those events where you don't have to tame the crowd

In some cases, the crowd remains calm despite provocations. A good example is the human rights movement in the United States in the 1950s and 60s.

Protesters largely remained calm despite police provocations. The absence of violence was part of the ideology of the movement.

Most often, people in the crowd are peaceful, and we ourselves look for opportunities to join them, simply because we like to be in the company. Watching football in a half-empty stadium is a dubious pleasure.

Music festivals attract visitors, not least because of the opportunity to listen to your favorite artists in the company of the same fans.

What is considered a crowd

Of course, in connection with this, the question arises: what should be considered a crowd?

Compare the situation: you are sitting among the fans in a crowded stadium or in a commuter train full of passengers. In the first case, you are most likely having fun, in the second - perhaps not very comfortable.

In the first case, you are most likely having fun, in the second - perhaps not very comfortable.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Photo caption,There is no psychological connection between pedestrians on the streets of a bustling city

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

The End of the Story Podcast

Part of the reason is that there is no psychological connection between the train passengers, they do not feel any unity among themselves. Now imagine that the train is stuck in a tunnel and the driver announces that for technical reasons the stop will last indefinitely. What will happen next?

People can start socializing and even, for example, share sandwiches. Now they are part of a group, there is a psychological connection between them, life has been made difficult for them by the railway company.

Emotional connection can affect us in many different ways. Earlier this year, the results of an unusual experiment conducted by Professor Steve Reicher of the University of St. Andrew were published.

A group of 135 students were asked to smell sweaty T-shirts. Some of them sniffed a T-shirt with the emblem of their university, others - a regular T-shirt.

The latter spent less time doing this activity and then washed their hands more thoroughly.

The authors of the study concluded that the degree of disgust depended on the emotional connection with the garment.

In a crowded train car, we often find it disgusting to snuggle up to someone else's body, while at a music festival this doesn't bother us.

Feeling of unity

The study of crowd psychology has many practical applications. Firstly, it helps to better control the mass congestion of people. In the past, the British police used a tactic called "containment", or, as it is popularly known, "boiling pot tactics".

The police cordon off the crowd, preventing the protesters from leaving the fences, and hold the cordon until they decide it is safe to disperse the demonstration.

The European Court of Human Rights, after considering the complaint, recognized this tactic as legal.

Even if it's legal, Professor Reicher thinks it's a terrible way to deal with the threat of unrest. In a confined space, a sense of unity among the demonstrators is enhanced - just like the passengers of a broken train.

Image copyright AFP

Image captionFormer London Police Chief Bob Broadhurst admits crowd control methods were too harsh in the past

When police use the 'boiling pot' tactic, all demonstrators end up in the same situation and it helps them cohesion. They may feel that their legal rights are being violated, and those who call for a rebuff to the police are gaining popularity.

At the same time, it is often those who were initially peaceful who, as a result, react most sharply to harsh police measures.

"Each group has its own idea of what is good and what is bad, and attacking what they consider their legal rights can make them angry," says Prof. Reicher.

"The irony of the 'boiling pot' is that experienced protesters may not like this tactic, but at least they are used to it," says Reicher. Problems, according to him, arise precisely with those who have never experienced this on themselves - they are angry, not expecting such an attitude towards themselves.

Police officers are often afraid of just a few aggressive people, but at the same time they treat the entire crowd equally and thus only help to spread their influence over peaceful protesters.

"Convince, not protect"

Crowd psychologist Prof. Clifford Stott believes that the police should help legitimate demonstrations rather than hinder them.

"The best way to deal with problems like this is to promote law-abiding protesters, not focus on lawbreakers," he says.

The police seem to be starting to use academic research on crowd psychology in their work. Bob Broadhurst was for many years the Chief of Public Order for the London Police.

For example, he was in charge of the police operation during the 2009 G20 summit in London and the accompanying anti-globalization street protests. Then the "boiling pot" technique was also applied to the demonstrators.

He still thinks this is a perfectly acceptable tactic, but admits that it may have been applied too harshly in the past.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,Police hold back a crowd during an anti-globalization demonstration on April 1, 2009

During those demonstrations, London newspaper salesman Ian Tomlinson was hit with a police baton and subsequently died in hospital.