When heart breaks

5 Crucial Things to Do When a Heart Breaks — JILLIAN TURECKI

It can be incredibly painful and difficult to recover from a broken heart, and if you’ve experienced heart break in love, it’s natural to wonder how you can numb the pain. After all, that despair can be hard to live with, and most people search for a quick escape, especially when it’s fresh in their mind.

The good news is, it’s possible to move forward. You CAN heal from your pain. The emotional pain doesn’t have to be something that you ruminate on for years and years.

Instead, heartbreak can be something that leads you to becoming a better version of yourself. These 5 steps will make it easier to manage the loss.

1. Allow Yourself to feel the HeartbreakWhen you experience heartbreak, it’s crucial to feel your feelings. During the early stages of being in a heartbreak spiral, you might consider avoiding the sensation entirely, trying to make it seem like you’re doing just fine.

This process of denial is one of the five stages of grief, and while it’s something you may have to go through, it’s not a safe place to stay in for long.

You need to recognize that the pain of a romantic relationship ending hurts. This is normal and healthy, and allowing yourself to express that pain is much healthier than avoiding expressing it. Whether it’s by crying, inviting over friends to watch sad movies, writing sad poetry, listening to sad music, or something else, embracing this sadness can be a crucial part of recognizing and accepting the heartbreak.

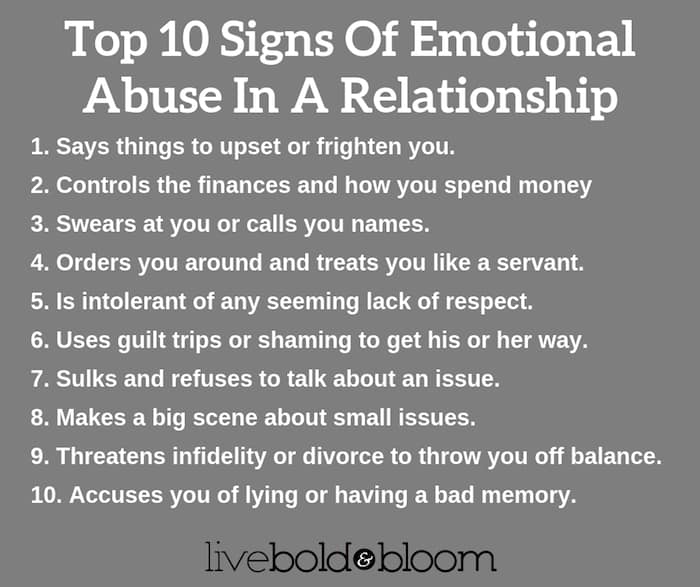

2. Understand That Being Heartbroken Is Something to Take SeriouslyEmotional pain is not “less serious” than physical pain. Your emotional pain is important, and you need to recognize that the emotions you’re feeling are as valid as someone expressing discomfort after breaking a bone. Even though the emotional pain you’re feeling may not be something that you can see from the outside, it’s still important, and you deserve to treat it as such.

Allow yourself to treat your heartbreak with the same weight that you would treat a physical injury. Give it the care and value that you would give any wound - because your brain thinks about heartbreak the same way it thinks about other types of pain. The sooner you give your pain legitimacy, the sooner you can move on from it.

3. Seek Support for your HeartbreakWhen heart break happens, a common struggle you may experience is the fear of social rejection. Are people going to treat you differently because you no longer have a partner? Will you end up with a completely different friend group because you were friends with all your partner’s friends?

This is why support structures are a necessity during heart break. These support structures may include your friends, but they can also include:

Support groups made up of people who have also experienced heartbreak

Licensed therapists who can help you work through your problems

Family members who will be on your side

These people can provide some support when you’re dealing with the emotional pain of heartbreak.

It’s an easy habit to fall into, especially when you’re hurting or feeling despair: letting yourself and your self-care fall apart. However, taking care of yourself can have a huge impact on your health, even if you don’t feel like doing it. When you get extremely bad news, like negative news about the state of your relationship, it can make you not want to take care of yourself at all. However, doing so can make it easier for you to bounce back.

When you eventually try to move forward after heartbreak, it’s easier if you already created a basis of looking out and caring for yourself as an individual. It’s simple (and tempting) to get caught in the trap of thinking of yourself as only one half of a whole. Therefore, you may feel like you have no personal identity after a heart break. However, even without a romantic relationship, you deserve to take care of yourself.

5. Look for Resources About Heartbreak and Coming Back Stronger

Look for Resources About Heartbreak and Coming Back StrongerThough it may not feel like it, it’s possible to use your heartbreak to come back as a stronger person. Sure, heartbreak can be an upsetting and painful thing to experience, but it doesn’t have to completely destroy you as a person. You can use your heartbreak to build yourself up into a better, stronger person – someone who’s able to push back against the pain you’ve experienced.

An excellent approach is to work with someone who’s experienced heartbreak and knows how to numb the ache of a broken heart. Grit & Grace: 7 Steps to Survive Heartbreak is a great tool for anyone who wants to be stronger after their heartbreak than they were before. You can get Jillian Turecki’s groundbreaking program delivered to your inbox, so you can work through the program at your own pace.

How to Numb the Pain of a Broken Heart Over TimeTo some extent, time is one of few things that really works to heal a broken heart. Sure, there are ways to get over your broken heart more easily, cutting down on the time necessary to heal. However, you can’t get it past it in a single night. At some point, you will need to let time run its course.

Sure, there are ways to get over your broken heart more easily, cutting down on the time necessary to heal. However, you can’t get it past it in a single night. At some point, you will need to let time run its course.

During that time, you have the choice: either try to forget this experience or use it to make you stronger. If you’re part of the second camp, you’ll need information that can help you transform this heartbreak into a form of strength. With some support and extra knowledge, you can not only numb the pain - but use it to your advantage.

This Is Your Brain on Heartbreak

As most of us know all too well, when you’re reeling from the finale of a romantic relationship that you didn’t want to end, your emotional and bodily reactions are a tangle: You’re still in love and want to reconcile, but you’re also angry and confused; simultaneously, you’re jonesing for a “fix” of the person who has abruptly left your life, and you might go to dramatic, even embarrassing, lengths to get it, even though part of you knows better.

What does our brain look like when we’re in the throes of such agonizing heartbreak? This isn’t just an academic question. The answer can help us better understand not only what’s going on inside our lovelorn bodies, but why humans may have evolved to feel such visceral pain in the wake of a break-up. In that light, the neuroscience of heartbreak can offer some practical—and provocative—ideas for how we can recover from love gone wrong.

Addicted to love

Advertisement XMeet the Greater Good Toolkit

From the GGSC to your bookshelf: 30 science-backed tools for well-being.

The earliest pairings of brain research and love research, from around 2005, established the baseline that would inform research going forward: what a brain in love looks like. In a study led by psychologist Art Aron, neurologist Lucy Brown, and anthropologist Helen Fisher, individuals who were deeply in love viewed images of their beloved and simultaneously had their brains scanned in an fMRI machine, which maps neural activity by measuring changes in blood flow in the brain. The fMRI’s vivid casts of yellows, greens, and blues—fireworks across gray matter—clearly showed that romantic love activates in the caudate nucleus, via a flood of dopamine.

The fMRI’s vivid casts of yellows, greens, and blues—fireworks across gray matter—clearly showed that romantic love activates in the caudate nucleus, via a flood of dopamine.

© Don Bayley

The caudate nucleus is associated with what psychologists call “motivation and goal-oriented behavior,” or “the rewards system.” To many of these experts, the fact that love fires there suggests that love isn’t so much an emotion in its own right—although aspects of it are obviously highly emotional—as it is a “goal-oriented motivational state.” (If that term seems confusing, it might help to think about it in terms of facial expressions: Emotions are characterized by particular, passing facial expressions—a frown with anger, a smile with happiness, an open mouth with shock—while if you had to identify the face of someone “in love,” it would be harder to do.) So as far as brain wiring is concerned, romantic love is the motivation to obtain and retain the object of your affections.

But romance isn’t the only thing that stimulates increases in dopamine and its rocketlike path through your reward system. Nicotine and cocaine follow exactly the same pattern: Try it, dopamine is released, it feels good, and you want more—you are in a “goal-oriented motivational state.” Take this to its logical conclusion and, as far as brain wiring is concerned, when you’re in love, it’s not as if you’re an addict. You are an addict.

Just as love at its best is explained by fMRI scans, so, too, is love at its worst. In 2010 the team who first used fMRI scanning to connect love and the caudate nucleus set out to observe the brain when anger and hurt feelings enter the mix. They gathered a group of individuals who were in the first stages of a breakup, all of whom reported that they thought about their rejecter approximately 85 percent of their waking hours and yearned to reunite with him or her. Moreover, all of these lovelorn reported “signs of lack of emotion control on a regular basis since the initial breakup, occurring regularly for weeks or months. This included inappropriate phoning, writing or e-mailing, pleading for reconciliation, sobbing for hours, drinking too much and/or making dramatic entrances and exits into the rejecter’s home, place of work or social space to express anger, despair or passionate love.” In other words, each of these bereft souls had it bad.

This included inappropriate phoning, writing or e-mailing, pleading for reconciliation, sobbing for hours, drinking too much and/or making dramatic entrances and exits into the rejecter’s home, place of work or social space to express anger, despair or passionate love.” In other words, each of these bereft souls had it bad.

Then, with appropriate controls, the researchers passed their subjects through fMRI machines, where they could look at photographs of their beloved (called the “rejecter stimulus”), and simultaneously prompted them to share their feelings and experience, which elicited statements such as “It hurt so much,” and “I hate what he/she did to me.”

A few particularly interesting patterns in brain activity emerged:

As far as the midbrain reward system is concerned, they were still “in love.” Just because the “reward” is delayed in coming (or, more to the point, not coming at all), that doesn’t mean the neurons that are expecting “reward” shut down. They keep going and going, waiting and waiting for a “fix.” Not surprisingly, among the experiment’s subjects, the caudate was still very much in love and reacted in an almost Pavlovian way to the image of the loved one. Even though cognitively they knew that their relationships were over, part of each participant’s brain was still in motivation mode.

They keep going and going, waiting and waiting for a “fix.” Not surprisingly, among the experiment’s subjects, the caudate was still very much in love and reacted in an almost Pavlovian way to the image of the loved one. Even though cognitively they knew that their relationships were over, part of each participant’s brain was still in motivation mode.

Parts of the brain were trying to override others. The orbital frontal cortex, which is involved in learning from emotions and controlling behavior, activated. As we all know, when you’re in the throes of heartbreak, you want to do things you’ll probably regret later, but at the same time another part of you is trying to keep a lid on it.

They were still addicted. As they viewed images of their rejecters, regions of the brain were activated that typically fire in individuals craving and addicted to drugs. Again, no different from someone addicted to—and attempting a withdrawal from—nicotine or cocaine.

While these conclusions explain in broad strokes what happens in our brains when we’re dumped, one scientist I interviewed describes what happens in our breakup brains in a slightly different way. “In the case of a lost love,” he told me, “if the relationship went on for a long time, the grieving person has thousands of neural circuits devoted to the lost person, and each of these has to be brought up and reconstructed to take into account the person’s absence.”

“In the case of a lost love,” he told me, “if the relationship went on for a long time, the grieving person has thousands of neural circuits devoted to the lost person, and each of these has to be brought up and reconstructed to take into account the person’s absence.”

Which brings us, of course, to the pain.

Love hurts

When you’re deep in the mire of heartbreak, chances are that you feel pain somewhere in your body—probably in your chest or stomach. Some people describe it as a dull ache, others as piercing, while still others experience it as a crushing sensation. The pain can last for a few seconds and then subside, or it can be chronic, hanging over your days and depleting you like just like the pain, say, of a back injury or a migraine.

This essay is adapted from The Little Book of Heartbreak: Love Gone Wrong Through the Ages (Plume, 2012).

But how can we reconcile the sensation of our hearts breaking—when in fact they don’t, at least not literally—with biophysical reality? What actually happens in our bodies to create that sensation? The short answer is that no one knows. The long answer is that the pain might be caused by the simultaneous hormonal triggering of the sympathetic activation system (most commonly referred to as fight-or-flight stress that ramps up heart and lung action) and the parasympathetic activation system (known as the rest-and-digest response, which slows the heart down and is tied to the social-engagement system). In effect, then, it could be as if the heart’s accelerator and brakes are pushed simultaneously, and those conflicting actions create the sensation of heartbreak.

The long answer is that the pain might be caused by the simultaneous hormonal triggering of the sympathetic activation system (most commonly referred to as fight-or-flight stress that ramps up heart and lung action) and the parasympathetic activation system (known as the rest-and-digest response, which slows the heart down and is tied to the social-engagement system). In effect, then, it could be as if the heart’s accelerator and brakes are pushed simultaneously, and those conflicting actions create the sensation of heartbreak.

While no one has yet studied what exactly goes on in the upper-body cavity during the moments of heartbreak that might account for the physical pain, the results of the aforementioned fMRI study of heartbroken individuals indicate that when the subjects looked at and discussed their rejecter, they trembled, cried, sighed, and got angry, and in their brains these emotions triggered activity in the same area associated with physical pain. Another study that explored the emotional-physical pain connection compared fMRI results on subjects who touched a hot probe with those who looked at a photo of an ex-partner and mentally relived that particular experience of rejection. The results confirmed that social rejection and physical pain are rooted in exactly the same regions of the brain. So when you say you’re “hurt” as a result of being rejected by someone close to you, you’re not just leaning on a metaphor. As far as your brain is concerned, the pain you feel is no different from a stab wound.

The results confirmed that social rejection and physical pain are rooted in exactly the same regions of the brain. So when you say you’re “hurt” as a result of being rejected by someone close to you, you’re not just leaning on a metaphor. As far as your brain is concerned, the pain you feel is no different from a stab wound.

This neatly parallels the discoveries that love can be addictive on a par with cocaine and nicotine. Much as we think of “heartbreak” as a verbal expression of our pain or say we “can’t quit” someone, these are not actually artificial constructs—they are rooted in physical realities. How wonderful that science, and specifically images of our brains, should reveal that metaphors aren’t poetic flights of fancy.

But it’s important to note that heartbreak falls under the rubric of what psychologists who specialize in pain call “social pain”—the activation of pain in response to the loss of or threats to social connection. From an evolutionary perspective, the “social pain” of separation likely served a purpose back on the savannas that were the hunting and gathering grounds of our ancestors. There, safety relied on numbers; exclusion of any kind, including separation from a group or one’s mate, signaled death, just as physical pain could signal a life-threatening injury. Psychologists reason that the neural circuitries of physical pain and emotional pain evolved to share the same pathways to alert protohumans to danger; physical and emotional pain, when saber-toothed tigers lurked in the brush, were cues to pay close attention or risk death.

There, safety relied on numbers; exclusion of any kind, including separation from a group or one’s mate, signaled death, just as physical pain could signal a life-threatening injury. Psychologists reason that the neural circuitries of physical pain and emotional pain evolved to share the same pathways to alert protohumans to danger; physical and emotional pain, when saber-toothed tigers lurked in the brush, were cues to pay close attention or risk death.

On the surface, that functionality wouldn’t seem terribly relevant now—after all, few of us risk attack by a wild animal charging at us from behind the lilacs at any given moment, and living alone doesn’t mean a slow, lonely death. But still, the pain is there to teach us something. It focuses our attention on significant social events and forces us to learn, correct, avoid, and move on.

When you look at social pain from this perspective, you have to acknowledge that in our society we’re often encouraged to hide it. We bottle it up. While of course it’s possible to be private about one’s pain and still deal with it, and it may not be so healthy to share your sob story with everyone you meet on the street, if you’re totally ignoring it and the survival theory holds true, then you’re putting yourself at risk because you’re not alerting others to a potential crisis.

While of course it’s possible to be private about one’s pain and still deal with it, and it may not be so healthy to share your sob story with everyone you meet on the street, if you’re totally ignoring it and the survival theory holds true, then you’re putting yourself at risk because you’re not alerting others to a potential crisis.

The heartbreak pill?

Several studies, also using the hot probe + image + fMRI combo, have shown that looking at an image of a loved one actually reduces the experience of physical pain, in much the same way that, say, holding a loved one’s hand during a frightening or painful procedure does, or kissing a child’s boo-boo makes the tears go away. Science shows that love is effectively a painkiller, because it activates the same sections of brain stimulated by morphine and cocaine; moreover, the effects are actually quite strong.

On one level this suggests a wonderfully simple and elegant solution, albeit a New Agey one, to physical or emotional pain: All you need is love. And it bolsters the notion, faulty though it may be for some of us, that if you’re suffering from a broken heart, moving on fast can bring relief.

And it bolsters the notion, faulty though it may be for some of us, that if you’re suffering from a broken heart, moving on fast can bring relief.

There’s a point, however, where this trend in fMRI research starts to enter a prickly realm: Because physical pain and emotional pain—like heartbreak—travel along the same pathways in the brain, as covered earlier, this means that theoretically they can be medically treated in the same way. In fact, researchers recently showed that acetaminophen—yep, regular old Tylenol—reduces the experience of social pain. “We have shown for the first time that acetaminophen, an over-the-counter medication commonly used to reduce physical pain, also reduces the pain of social rejection, at both neural and behavioral levels,” they write in their paper in the journal Psychological Science.

But some experts argue that the moment you put a toe on the slippery slope of popping pills to make you feel better emotionally, you have to wonder if doing so circumvents nature’s plan. You’re supposed to feel bad, to sit with it, to review what went wrong, even to the point of obsession, so that you learn your lesson and don’t make the same mistake again.

You’re supposed to feel bad, to sit with it, to review what went wrong, even to the point of obsession, so that you learn your lesson and don’t make the same mistake again.

While they might not admit it, for biologists and psychologists, understanding love on a chemical level is tantamount to finding the holy grail. After all, the more we understand about love in terms of science . . . well then, the closer we are to understanding what makes humans human, an advance that might be on a par with physicists cracking the mystery of the space-time continuum.

Ultimately, all this progress points to one thing: treatment, with both painkillers and antiaddiction drugs. Perhaps recovering from heartbreak could be as simple as wearing a patch (Lovaderm!) or chewing a special gum (Lovorette!) or popping a pill (Alove!) that just makes the pain go away.

If you could take a pill that assured that you could fall in love, fall out of love, or stay in love on command, would you take it?

Broken Heart Syndrome: a disease "out of the head" from which you can die

Sign up for our "Context" newsletter: it will help you understand the events.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Your heart can suffer after some unfortunate event, and your brain is most likely responsible for your "heartbreak", experts say.

Swiss scientists are conducting a study on the so-called "broken heart syndrome". nine0005

Psychological stress can cause acute transient left ventricular dysfunction. The syndrome is manifested by the sudden development of heart failure or chest pain, combined with ECG changes characteristic of myocardial infarction of the anterior wall of the left ventricle.

- Scientists have found out how stress causes heart disease

Most often, this syndrome develops against the background of stressful situations that cause strong, often sharply negative, emotions. Such events can be the death of a loved one or separation. nine0005

Scientists do not yet have complete clarity on how this happens. In the publication of scientists in the medical journal European Heart Journal, it is suggested that the syndrome is provoked by the brain's response to stress.

In the publication of scientists in the medical journal European Heart Journal, it is suggested that the syndrome is provoked by the brain's response to stress.

The "broken heart syndrome" was first described by the Japanese scientist Hikaru Sato in 1990 and was named "takotsubo cardiomyopathy" (from the Japanese "takotsubo" - a ceramic pot with a round base and a narrow neck).

Image copyright Getty Images

This is different from a "normal" heart attack, when blood flow to the heart muscle is blocked. Blockage of blood flow to the heart occurs when there is a blood clot in the coronary arteries. nine0005

However, the symptoms of broken heart syndrome and heart attack are similar in many ways, most notably difficulty breathing and chest pain.

- Scientists: the brain of boys and girls reacts differently to severe stress

- Scientists: early baldness can be a sign of heart disease

Often some sad event is a kind of trigger that provokes the onset of the syndrome. However, joyful events that cause strong emotions can also lead to the development of broken heart syndrome. For example, getting married or getting a new job. nine0005

However, joyful events that cause strong emotions can also lead to the development of broken heart syndrome. For example, getting married or getting a new job. nine0005

Broken heart syndrome can be temporary, in which case the heart muscle will recover in a few days, weeks or months, and in some cases the syndrome can be fatal.

In Britain, about 2500 patients are diagnosed with broken heart syndrome each year.

Image copyright Christian Templin, University Hospital Zurich

Image captionX-ray of the heart of a person diagnosed with takotsubo syndrome

Skip Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

End of story Podcast

The exact cause of broken heart syndrome is unknown to scientists. However, it is suggested that this syndrome may be associated with an increase in the level of stress hormones - for example, adrenaline.

However, it is suggested that this syndrome may be associated with an increase in the level of stress hormones - for example, adrenaline.

Elena Gadri from the University Hospital Zurich, together with her colleagues, studied the brain activity of 15 patients diagnosed with broken heart syndrome. nine0005

Imaging data showed significant differences in the brain activity of these patients from that observed in 39 participants in the control group, who were healthy.

Much less communication has been noted between the areas of the brain responsible for controlling emotions and the body's unconscious (automatic) responses (such as the heartbeat).

"Emotions are formed in the brain, so it is quite possible that the disease is formed in the brain. And then the brain sends the appropriate signals to the heart," says Gadry. nine0005

Further research is needed to understand the mechanism of the syndrome.

The Swiss scientists who conducted the study had no CT scans of the patients before they were diagnosed with broken heart syndrome. Therefore, researchers cannot claim that the reduction in connections between different parts of the brain was a consequence of the development of the syndrome, or that the syndrome developed due to the reduction in connections.

Therefore, researchers cannot claim that the reduction in connections between different parts of the brain was a consequence of the development of the syndrome, or that the syndrome developed due to the reduction in connections.

"This is a very important part of the study, it will help us better understand the nature of this syndrome, which is often overlooked, and it continues to be a mystery to us," says Joel Rose, head of the British organization Cardiomyopathy. nine0005

"These studies will help us understand what role the brain plays in the syndrome and why some people are affected and others are not," says Joel Rose.

"These observations confirm our long-standing assumption about the special role of the connection between the brain and heart in the formation of takotsubo cardiomyopathy," says researcher Dana Dawson from the British Heart Foundation.

Media about us

Main page

/ Press center

/ Media about the cardio center

Arguments and facts in Western Siberia

World Diabetes Day: debunking the myths

World Diabetes Day 2022 falls on November 14th. On this day, we want to draw attention to the seriousness of the disease and the need for its timely detection, treatment and prevention. To do this, we...

On this day, we want to draw attention to the seriousness of the disease and the need for its timely detection, treatment and prevention. To do this, we...

11/15/2022

Health information portal "Doctor Peter"0005

A year after covid: a scientist told what happens to the health of those who have been ill

A large-scale study of the Tyumen Cardiology Research Center has been going on for more than two years. Doctors monitor the condition of 380 covid-pneumonia survivors.

10/19/2022

Tomsk NIMC

Insidious Alzheimer: how to recognize the disease in time

September 21 is the day of the fight against Alzheimer's disease. An expert tells about what symptoms should be a reason to consult a specialist: a gerontologist, a psychiatrist of the highest category of the Tyumen cardiological ...

09/21/2022

Newspaper "Tyumenskiye Izvestiya"

Nikita Shirokov: "It's important to be on the wave of new knowledge"

Until the eighth grade, Nikita was an average student, the triples did not upset him. At 17, according to the results of the Unified State Examination, he entered the state-funded place at the Tyumen Medical Academy. At 27, he became a candidate of medical sciences and began work on a doctoral thesis ...

At 17, according to the results of the Unified State Examination, he entered the state-funded place at the Tyumen Medical Academy. At 27, he became a candidate of medical sciences and began work on a doctoral thesis ...

27.08.2022

Arguments and facts - Tyumen0005

There is very little time left until the new school year, and these one and a half weeks can still be used with health benefits.

08/25/2022

AiF-Tyumen

"Don't demonize food." Gastroenterologist about healthy nutrition

The topic of proper and healthy nutrition is shrouded in many myths and disputes. To eat or not to eat after six in the evening, whether it is necessary to follow diets, drink food or drink tea strictly after meals, what is right and what is not, with ...

06/03/2022

AiF-Tyumen

Dementia epidemic. How to live old age in a clear mind?

Minor problems with memory or thinking tend to go unnoticed, attributed to fatigue, stress and age when it comes to older people.