Adhd and gender dysphoria

How They're Linked and Tips for Parents

People with ADHD may experience higher rates of gender variance and gender dysphoria. Here’s why, and how to offer support to loved ones.

People of all ages, races, and genders question their gender identity. But are folks with certain neurodevelopmental disorders, like attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), more likely to experience gender identity issues?

Understanding how living with ADHD may impact gender identity can lead to increased compassion, support, and access to gender-affirming care for those who are neurodivergent and gender nonconforming.

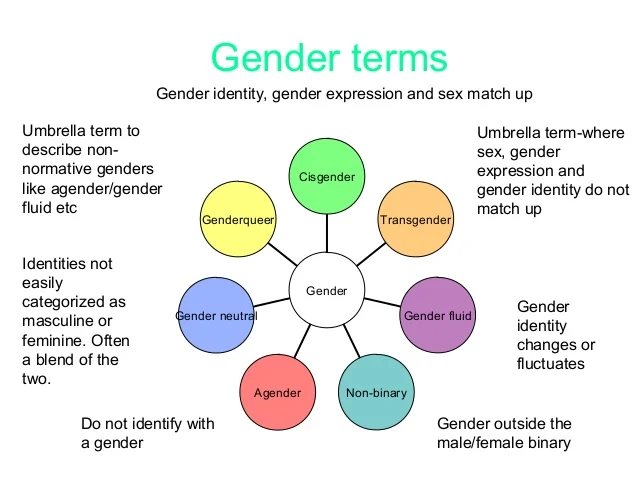

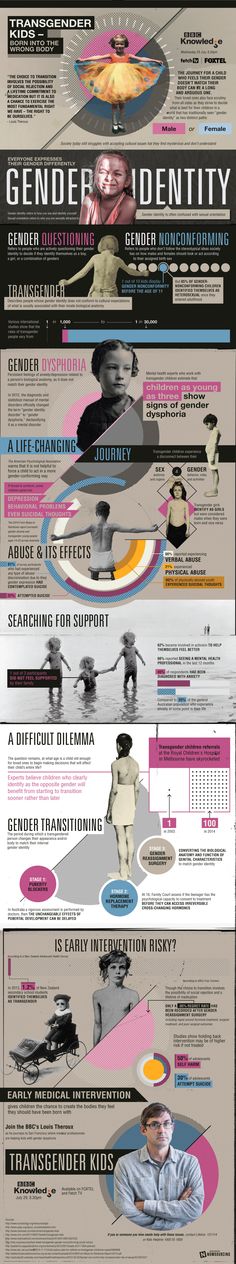

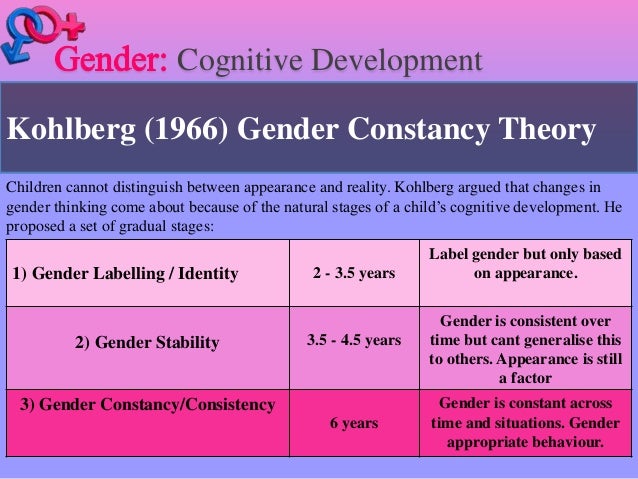

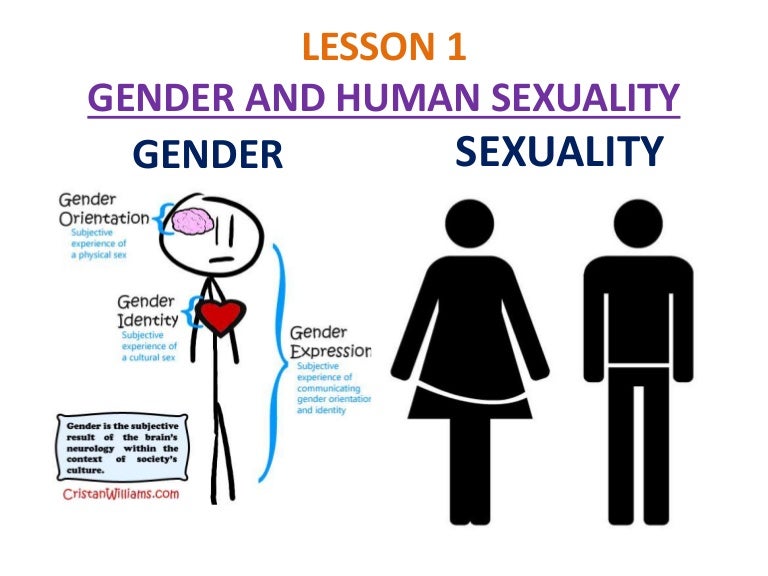

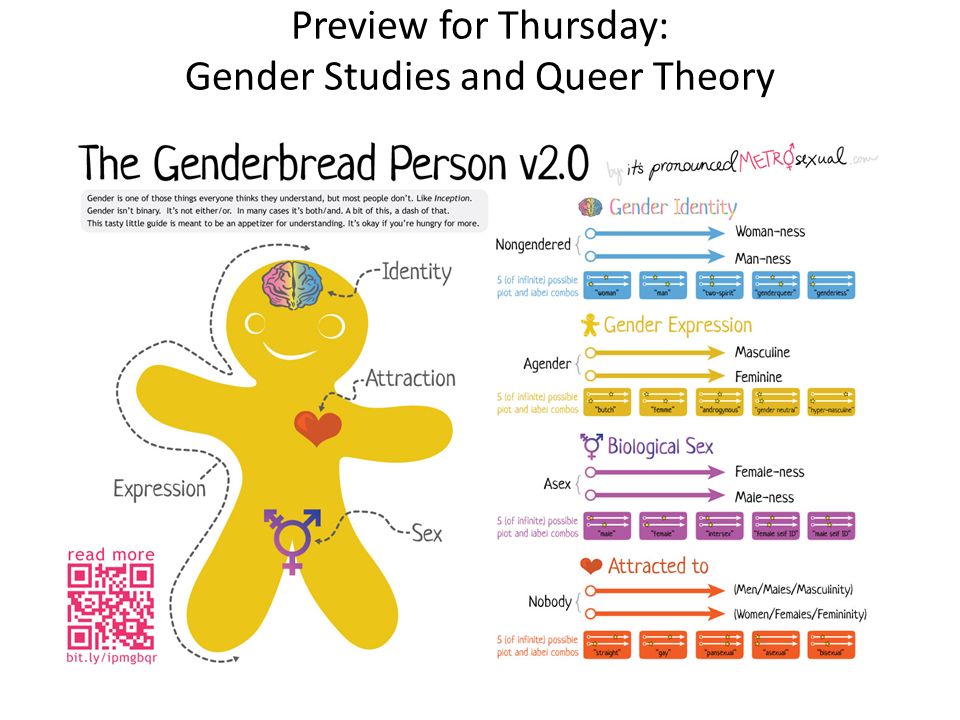

What is gender identity?

The American Psychological Associationdefines gender identity as:

“A person’s deeply felt, inherent sense of being a boy, a man, or male; a girl, a woman, or female; or an alternative gender (e.g., genderqueer, gender nonconforming, gender neutral) that may or may not correspond to a person’s sex assigned at birth or to a person’s primary or secondary sex characteristics. ”

“Since gender identity is internal, a person’s gender identity is not necessarily visible to others.”

More studies are needed on ADHD and gender. But some research suggests that people with ADHD may be more likely to question their gender.

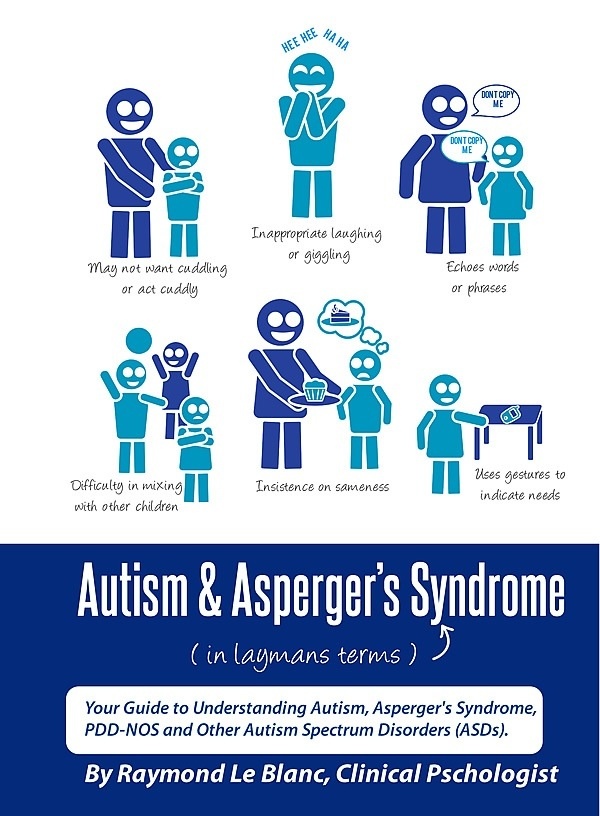

According to a 2014 study on gender variance in people living with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and ADHD, participants with ADHD were 6.64 times more likely to express gender variance.

However, ADHD advocate and certified sex educator Cate Osborn who lives with ADHD herself notes studies like these point out that ADHD doesn’t “cause” someone to question their gender identity or experience gender dysphoria.

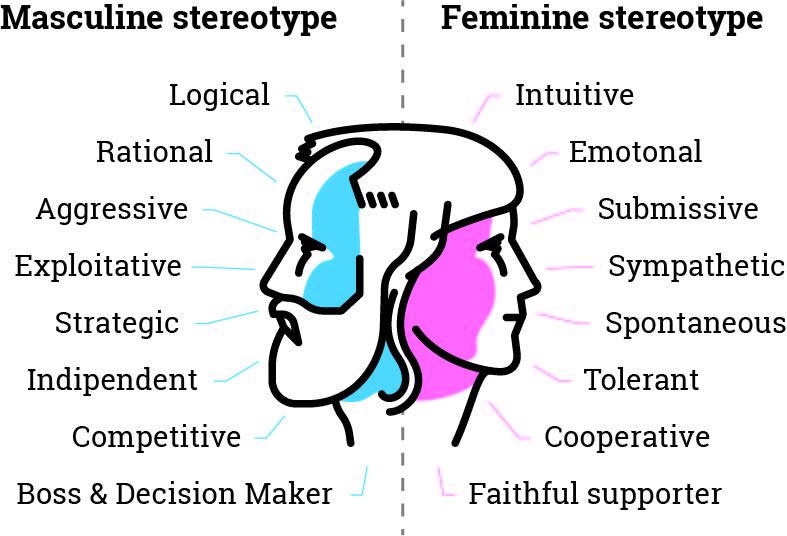

“Rather, individuals with neurodivergence are predisposed to reject the rigidity of gendered expectations placed on them by society,” they say.

A potentially helpful reframe

Instead of saying that ADHD causes someone to question their gender or experience gender dysphoria, Osborn says it would be more correct to explain it this way:

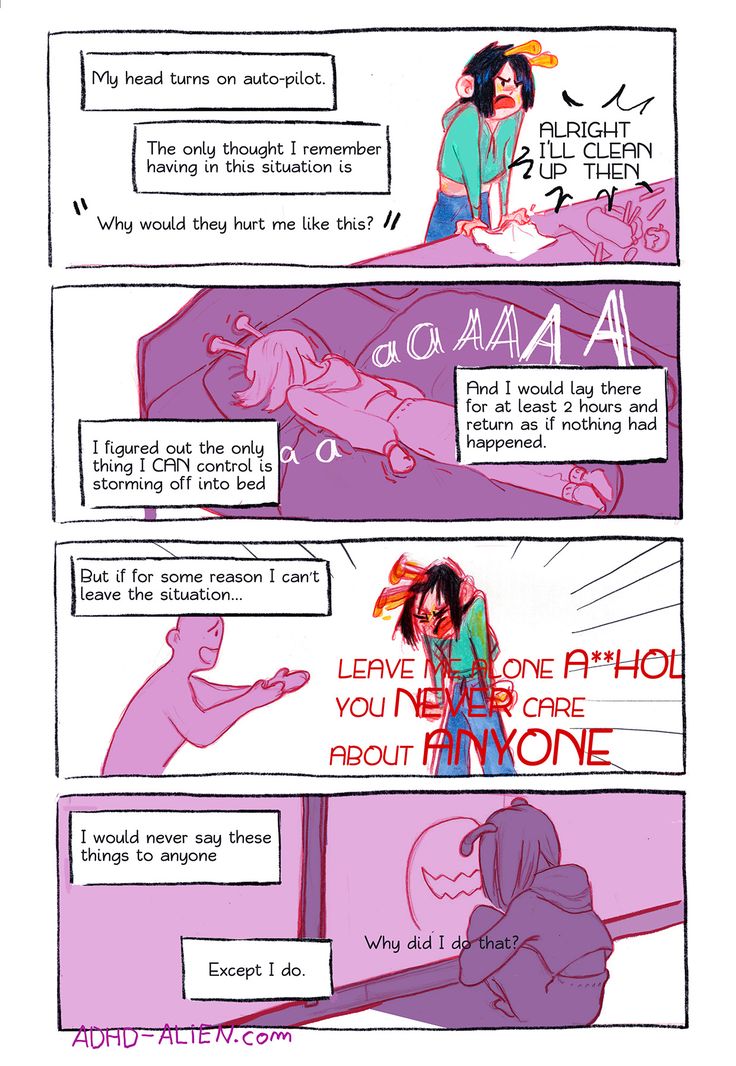

People who have ADHD often experience social rejection, bullying, and criticism from both their peers and the authority figures in their lives.

Because of this, many people with ADHD begin to perceive the world differently and come to realize that many of the expectations placed on them are arbitrary.

They can tend to reject these rules in service of their own systems and behaviors that better support them and cater to their needs.

For some people with ADHD, this includes the way they navigate and present their gender.

A 2017 study that explores 20 cases of gender dysphoria points out that 90% of cases had at least one psychiatric diagnosis. ADHD was the leading comorbidity at 75%.

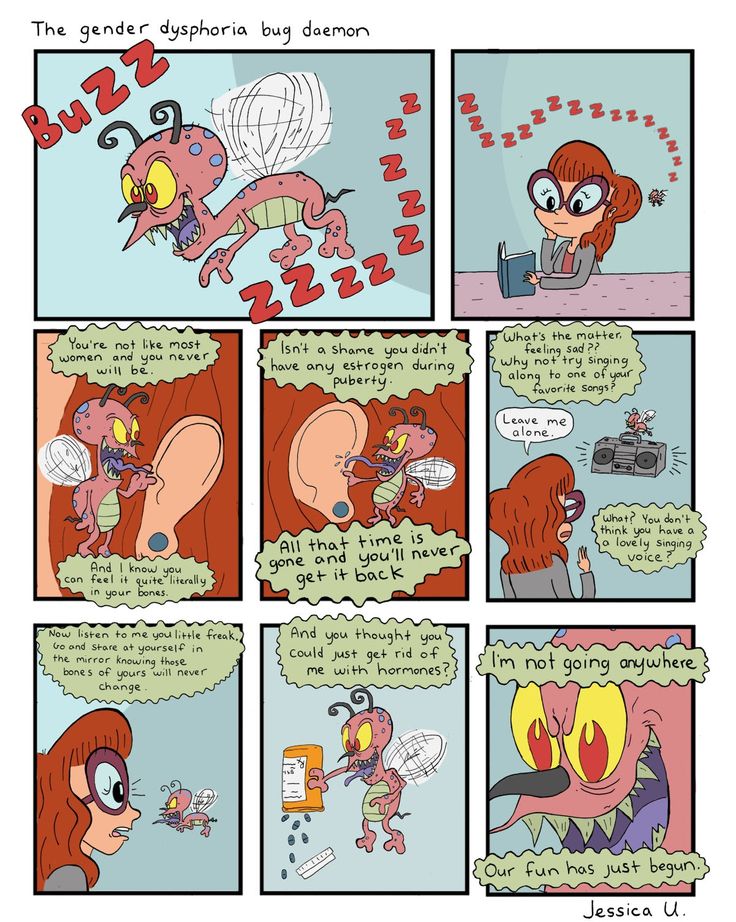

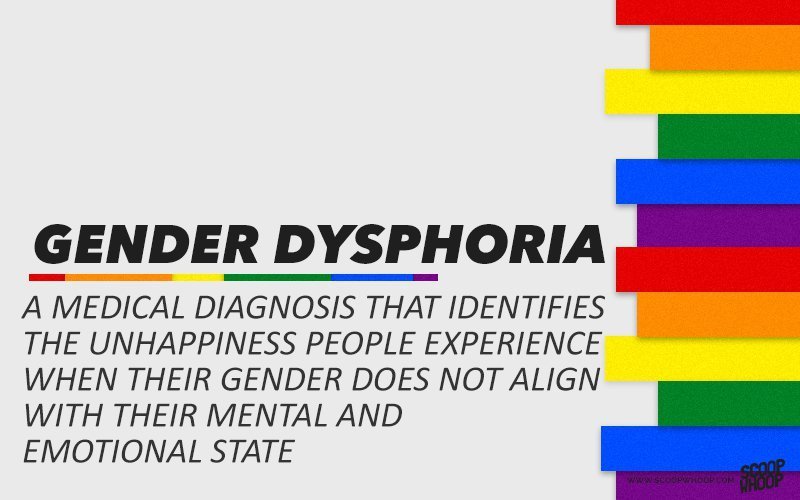

What is gender dysphoria?

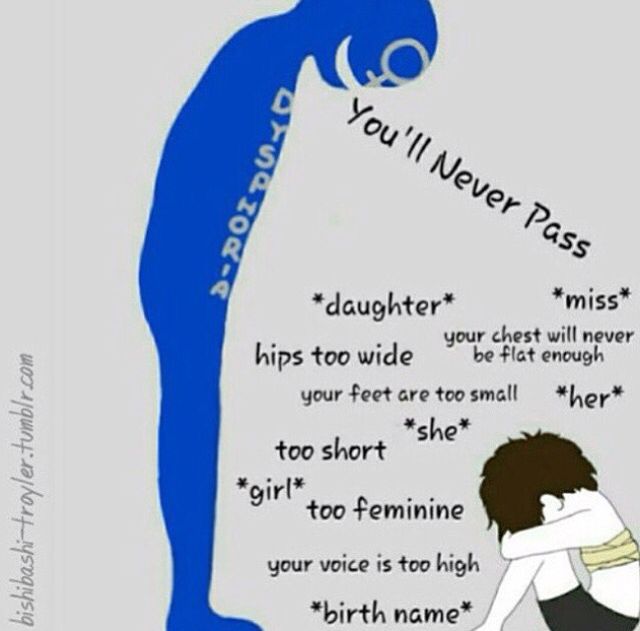

“Gender dysphoria is essentially a negative reaction to gender identity — discomfort or distress related to incongruence between a person’s gender identity, sex assigned at birth, gender identity, and/or primary and secondary sex characteristics,” says Osborn.

There are many possible explanations for this:

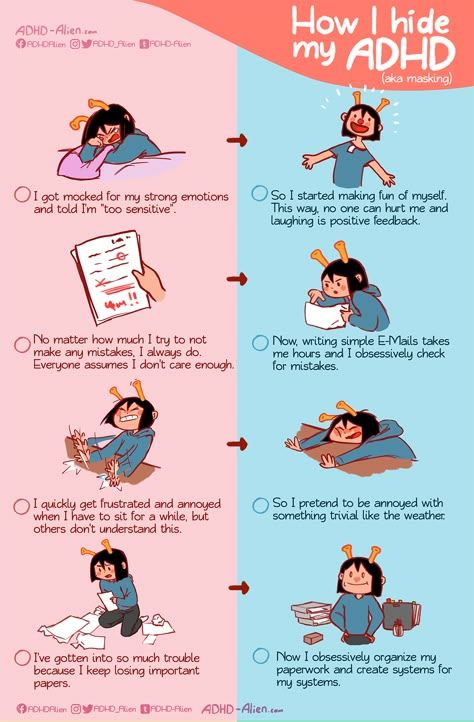

ADHD and executive dysfunction

Osborn explains that symptoms of executive dysfunction may play a large role, especially in connection with societal pressures to “perform” as a certain gender.

For example, Osborn says that a person assigned female at birth (AFAB) may feel pressure to wear makeup or jewelry. But they might lack the executive function necessary to do a full face of makeup every day or deal with sensory issues that make wearing jewelry or certain types of clothes difficult.

“Similarly, care tasks, like caring for long hair, can be difficult, whereas a short, cropped hairstyle might make for easier care and maintenance, but impact a person’s gender identity in that they don’t look how they want to or need to to feel fulfilled,” adds Osborn.

These executive dysfunction challenges could ultimately lead to higher rates of gender dysphoria for nonbinary, transgender, and gender nonconforming people with ADHD.

How we’re socialized

Many researchers now believe that how a person is socialized has much to do with how ADHD presents, says Osborn.

Whereas a young girl is much more likely to be socialized to sit still and be quiet and respectful, young boys may be more likely to be allowed to run around and roughhouse.

“As a result, there can be a lot of confusion when a woman presents as extremely hyperactive or a man presents primarily inattentive,” she adds.

“In extreme cases, this can result in a missed or misdiagnosis. I’ve heard from a lot of followers who say that their doctor basically told them that girls ‘can’t’ be hyperactive or young boys ‘never’ present as inattentive — and that’s just fundamentally not the case.”

If your child or loved one is experiencing gender identity issues, there are plenty of ways to support them through their process.

Educate yourself

There are many toxic ideas out there about what gender is, what gender isn’t, and what it “should be,” reminds Osborn.

Instead of expecting your loved one to teach you, she suggests learning about gender on your own, at your own pace.

Osborn recommends:

- engaging with content surrounding gender identity and gender diversity

- watching content created by gender nonconforming folks and experts in the space

- taking time to learn about your loved one’s specific identity and what that means to them

Process on your own

Your emotions are valid. But Osborn points out that many parents often make the mistake of putting the burden of reassurance and need for support onto their gender-questioning kid.

But Osborn points out that many parents often make the mistake of putting the burden of reassurance and need for support onto their gender-questioning kid.

“That isn’t their job,” she reminds. “They’re in the midst of a big moment of self-discovery. Let them have that without having to hold your hand through it.”

Know the importance of acceptance

Osborn explains that the majority of LGBTQIA+ kids who attempt suicide do so because they’ve been ostracized from their families and lack a safe support structure.

A 2021 study conducted by The Trevor Project found that 52% of transgender and nonbinary youth seriously considered suicide in the past year, with 1 in 5 reported attempting suicide.

The organization also found that having at least one accepting adult can drastically reduce the risk of suicide attempts in young LGBTQ+ people by 40%.

So try your best to offer support and practice acceptance.

“In trusting you with their concerns or questions about their gender, your kids are also offering you the opportunity to provide them support, acceptance, and kindness,” says Osborn.

“Remember that your acceptance can literally save their life.”

If you’re considering self-harm or suicide, you’re not alone

You can access free support right away with these resources:

- 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline.Call the Lifeline at 988 for English or Spanish, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

- The Crisis Text Line.Text HOME to the Crisis Text Line at 741741.

- The Trevor Project. LGBTQIA+ and under 25 years old? Call 866-488-7386, text “START” to 678678, or chat online 24/7.

- Veterans Crisis Line.Call 988 and press 1, text 838255, or chat online 24/7.

- Deaf Crisis Line.Call 321-800-3323, text “HAND” to 839863, or visit their website.

- Befrienders Worldwide.This international crisis helpline network can help you find a local helpline.

Encourage them to seek support

Receiving support from a therapist, accepting yourself, and being accepted by others can be incredibly healing and validating while on this journey of self-discovery.

Osborn explains that many folks find support in groups of neurodivergent people who share similar symptoms and experiences. “These groups tend to be more accepting and understanding than neurotypical peers who don’t understand the particular challenges of living with a neurodiversity.”

And when a person finds acceptance in a peer group, they note that there can be less pressure to “perform” or “mask” to avoid expressing these inclinations.

For some adults, teens, and children with ADHD, this can mean being more open and honest about their gender identity.

If you’re looking for a therapist, but you’re not sure where to start, Psych Central’s How to Find Mental Health Support resource can help.

If your kid comes to you and shares that they’d like to use a new name or different pronouns, Osborn recommends taking this seriously.

“Do not refuse because it’s ‘hard to remember’ or ‘not what you named them,’” she adds. “This is a tiny adaptation that can mean the world to your child and can literally be lifesaving.”

People living with ADHD may question their gender identity or experience gender dysphoria more often than people without ADHD. But there’s no evidence to support a direct cause-and-effect relationship between ADHD and gender nonconformity.

If you’re having a hard time navigating the process of questioning your gender identity or you’d like help supporting a loved one who is, you can consider speaking with a therapist.

And remember: There’s no one “right way” to be any gender, whether you live with ADHD or not. Your gender expression is deeply personal and deeply yours, says Osborn.

“Accepting yourself fully and completely is a deeply vulnerable process and can come with many, many mixed emotions,” she says.

“It’s OK to be unsure. It’s OK to question. It’s OK to change your mind, and it’s also OK to know with certainty that you are who you know you are. No one can take that away from you.”

No one can take that away from you.”

How They're Linked and Tips for Parents

People with ADHD may experience higher rates of gender variance and gender dysphoria. Here’s why, and how to offer support to loved ones.

People of all ages, races, and genders question their gender identity. But are folks with certain neurodevelopmental disorders, like attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), more likely to experience gender identity issues?

Understanding how living with ADHD may impact gender identity can lead to increased compassion, support, and access to gender-affirming care for those who are neurodivergent and gender nonconforming.

What is gender identity?

The American Psychological Associationdefines gender identity as:

“A person’s deeply felt, inherent sense of being a boy, a man, or male; a girl, a woman, or female; or an alternative gender (e.g., genderqueer, gender nonconforming, gender neutral) that may or may not correspond to a person’s sex assigned at birth or to a person’s primary or secondary sex characteristics. ”

”

“Since gender identity is internal, a person’s gender identity is not necessarily visible to others.”

More studies are needed on ADHD and gender. But some research suggests that people with ADHD may be more likely to question their gender.

According to a 2014 study on gender variance in people living with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and ADHD, participants with ADHD were 6.64 times more likely to express gender variance.

However, ADHD advocate and certified sex educator Cate Osborn who lives with ADHD herself notes studies like these point out that ADHD doesn’t “cause” someone to question their gender identity or experience gender dysphoria.

“Rather, individuals with neurodivergence are predisposed to reject the rigidity of gendered expectations placed on them by society,” they say.

A potentially helpful reframe

Instead of saying that ADHD causes someone to question their gender or experience gender dysphoria, Osborn says it would be more correct to explain it this way:

People who have ADHD often experience social rejection, bullying, and criticism from both their peers and the authority figures in their lives.

Because of this, many people with ADHD begin to perceive the world differently and come to realize that many of the expectations placed on them are arbitrary.

They can tend to reject these rules in service of their own systems and behaviors that better support them and cater to their needs.

For some people with ADHD, this includes the way they navigate and present their gender.

A 2017 study that explores 20 cases of gender dysphoria points out that 90% of cases had at least one psychiatric diagnosis. ADHD was the leading comorbidity at 75%.

What is gender dysphoria?

“Gender dysphoria is essentially a negative reaction to gender identity — discomfort or distress related to incongruence between a person’s gender identity, sex assigned at birth, gender identity, and/or primary and secondary sex characteristics,” says Osborn.

There are many possible explanations for this:

ADHD and executive dysfunction

Osborn explains that symptoms of executive dysfunction may play a large role, especially in connection with societal pressures to “perform” as a certain gender.

For example, Osborn says that a person assigned female at birth (AFAB) may feel pressure to wear makeup or jewelry. But they might lack the executive function necessary to do a full face of makeup every day or deal with sensory issues that make wearing jewelry or certain types of clothes difficult.

“Similarly, care tasks, like caring for long hair, can be difficult, whereas a short, cropped hairstyle might make for easier care and maintenance, but impact a person’s gender identity in that they don’t look how they want to or need to to feel fulfilled,” adds Osborn.

These executive dysfunction challenges could ultimately lead to higher rates of gender dysphoria for nonbinary, transgender, and gender nonconforming people with ADHD.

How we’re socialized

Many researchers now believe that how a person is socialized has much to do with how ADHD presents, says Osborn.

Whereas a young girl is much more likely to be socialized to sit still and be quiet and respectful, young boys may be more likely to be allowed to run around and roughhouse.

“As a result, there can be a lot of confusion when a woman presents as extremely hyperactive or a man presents primarily inattentive,” she adds.

“In extreme cases, this can result in a missed or misdiagnosis. I’ve heard from a lot of followers who say that their doctor basically told them that girls ‘can’t’ be hyperactive or young boys ‘never’ present as inattentive — and that’s just fundamentally not the case.”

If your child or loved one is experiencing gender identity issues, there are plenty of ways to support them through their process.

Educate yourself

There are many toxic ideas out there about what gender is, what gender isn’t, and what it “should be,” reminds Osborn.

Instead of expecting your loved one to teach you, she suggests learning about gender on your own, at your own pace.

Osborn recommends:

- engaging with content surrounding gender identity and gender diversity

- watching content created by gender nonconforming folks and experts in the space

- taking time to learn about your loved one’s specific identity and what that means to them

Process on your own

Your emotions are valid. But Osborn points out that many parents often make the mistake of putting the burden of reassurance and need for support onto their gender-questioning kid.

But Osborn points out that many parents often make the mistake of putting the burden of reassurance and need for support onto their gender-questioning kid.

“That isn’t their job,” she reminds. “They’re in the midst of a big moment of self-discovery. Let them have that without having to hold your hand through it.”

Know the importance of acceptance

Osborn explains that the majority of LGBTQIA+ kids who attempt suicide do so because they’ve been ostracized from their families and lack a safe support structure.

A 2021 study conducted by The Trevor Project found that 52% of transgender and nonbinary youth seriously considered suicide in the past year, with 1 in 5 reported attempting suicide.

The organization also found that having at least one accepting adult can drastically reduce the risk of suicide attempts in young LGBTQ+ people by 40%.

So try your best to offer support and practice acceptance.

“In trusting you with their concerns or questions about their gender, your kids are also offering you the opportunity to provide them support, acceptance, and kindness,” says Osborn.

“Remember that your acceptance can literally save their life.”

If you’re considering self-harm or suicide, you’re not alone

You can access free support right away with these resources:

- 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline.Call the Lifeline at 988 for English or Spanish, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

- The Crisis Text Line.Text HOME to the Crisis Text Line at 741741.

- The Trevor Project. LGBTQIA+ and under 25 years old? Call 866-488-7386, text “START” to 678678, or chat online 24/7.

- Veterans Crisis Line.Call 988 and press 1, text 838255, or chat online 24/7.

- Deaf Crisis Line.Call 321-800-3323, text “HAND” to 839863, or visit their website.

- Befrienders Worldwide.This international crisis helpline network can help you find a local helpline.

Encourage them to seek support

Receiving support from a therapist, accepting yourself, and being accepted by others can be incredibly healing and validating while on this journey of self-discovery.

Osborn explains that many folks find support in groups of neurodivergent people who share similar symptoms and experiences. “These groups tend to be more accepting and understanding than neurotypical peers who don’t understand the particular challenges of living with a neurodiversity.”

And when a person finds acceptance in a peer group, they note that there can be less pressure to “perform” or “mask” to avoid expressing these inclinations.

For some adults, teens, and children with ADHD, this can mean being more open and honest about their gender identity.

If you’re looking for a therapist, but you’re not sure where to start, Psych Central’s How to Find Mental Health Support resource can help.

If your kid comes to you and shares that they’d like to use a new name or different pronouns, Osborn recommends taking this seriously.

“Do not refuse because it’s ‘hard to remember’ or ‘not what you named them,’” she adds. “This is a tiny adaptation that can mean the world to your child and can literally be lifesaving.”

People living with ADHD may question their gender identity or experience gender dysphoria more often than people without ADHD. But there’s no evidence to support a direct cause-and-effect relationship between ADHD and gender nonconformity.

If you’re having a hard time navigating the process of questioning your gender identity or you’d like help supporting a loved one who is, you can consider speaking with a therapist.

And remember: There’s no one “right way” to be any gender, whether you live with ADHD or not. Your gender expression is deeply personal and deeply yours, says Osborn.

“Accepting yourself fully and completely is a deeply vulnerable process and can come with many, many mixed emotions,” she says.

“It’s OK to be unsure. It’s OK to question. It’s OK to change your mind, and it’s also OK to know with certainty that you are who you know you are. No one can take that away from you.”

No one can take that away from you.”

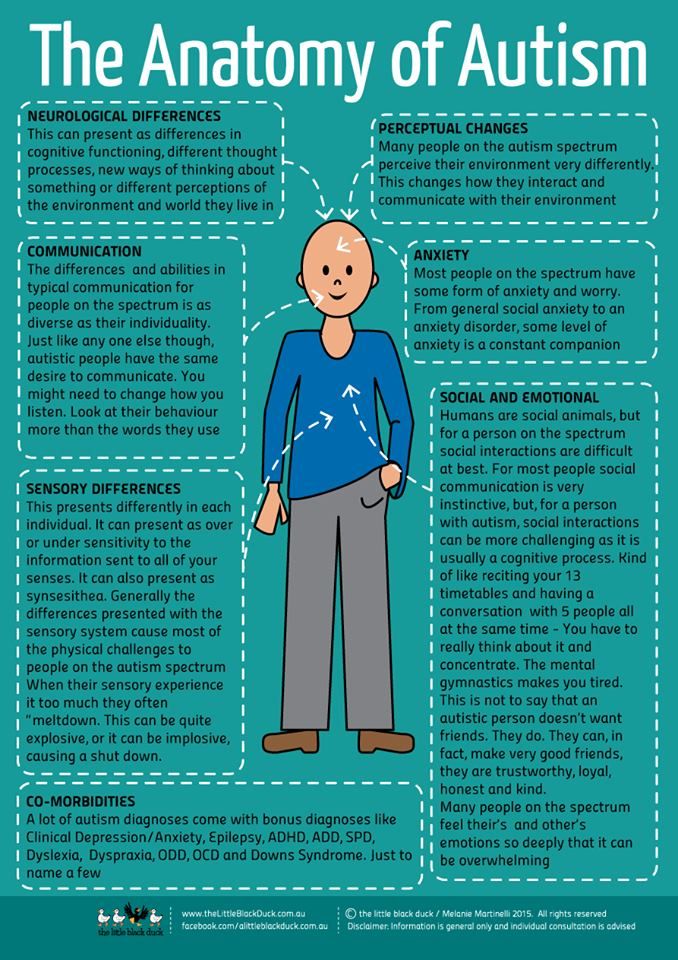

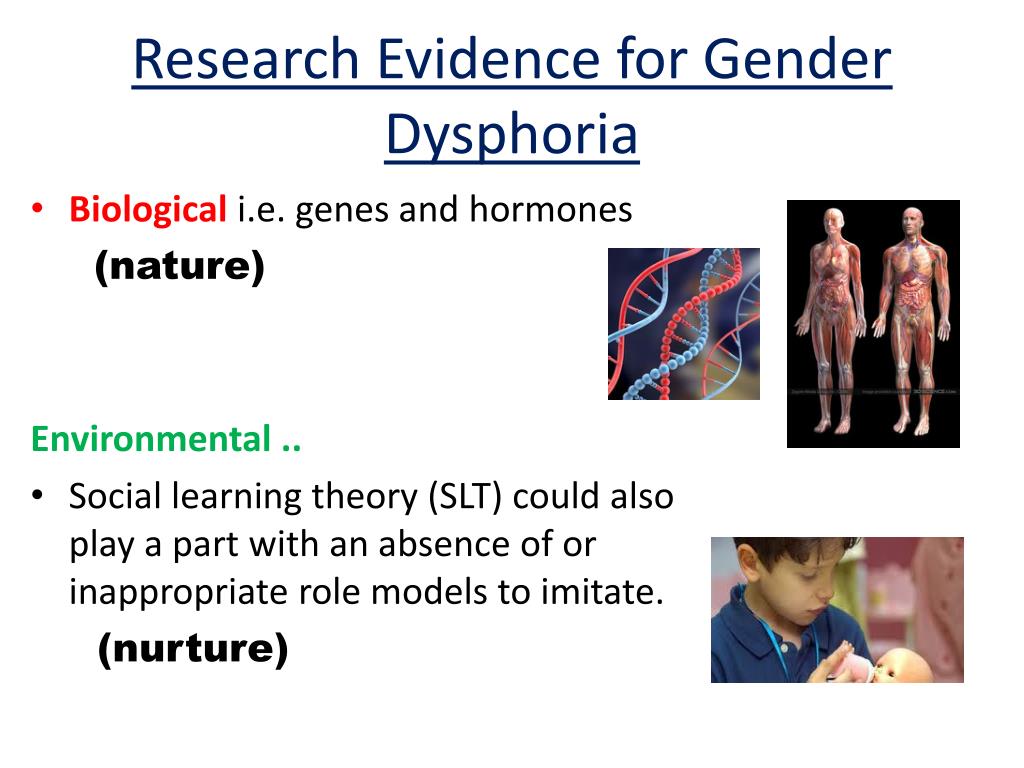

Gender non-binary and transgender have been linked to autistic traits

Researchers from the University of Cambridge, based on data from almost 642 thousand people, found that transgender and non-binary people have autism, autism-related traits and other mental disorders more often than cisgender people of people. The reasons and mechanisms for this connection remain unclear, but the authors of the paper, published in the journal Nature Communications , call for easier access to mental health care and greater support for transgender people. nine0005

The biological sex, which is determined by anatomical, physiological and genetic characteristics, does not always coincide with a person's sense of self. In this case, they say that gender does not coincide with sex, and such people are called transgender - their number is approximately 0.4-1.3 percent of the population. The gender identity of a person may not fit into a binary system (division into male and female gender) - there are people who identify themselves with different genders simultaneously or alternately, or do not associate themselves with any gender at all. nine0005

nine0005

Often the mismatch between gender identity and biological sex causes discomfort and becomes the cause of a personality disorder - gender dysphoria. In addition, a number of studies involving people with gender dysphoria have found that these groups are more likely than cisgender people to have autism spectrum disorders and other mental disorders. However, the conclusions of these studies are based on small samples, the studies used different methods for determining transgender and autistic symptoms, and analyzed people of different ages and nationalities - which means that no generalization can be directly drawn from them. nine0005

Psychologists and psychiatrists from the University of Cambridge, led by Varun Warrier and Simon Baron-Cohen, analyzed five data sets based on online surveys, a total sample of almost 642,000 people, and answered the question, whether autism spectrum disorders, autistic symptoms and other mental disorders are actually more common in transgender and non-binary people than in cisgender people.

In all five datasets, transgender and non-binary people were diagnosed with autism significantly more often than cisgender women, men, and cisgender people in general (odds ratios ranged from 3.03 to 6.36). In four of the five datasets, the relationship persisted even after adjusting for age and education (in the fifth, the effect was not statistically significant). Conversely, in the same four sets, the percentage of transgender people and people with non-binary gender was higher among those diagnosed with autism (p < 2 × 10 −16 ).

The authors then analyzed the results of four questionnaires on autism-related traits — scores on autism, classification, empathy, and sensory perception — across genders. In transgender and non-binary people, three coefficients other than empathy were on average higher than in cisgender people. The effect was observed both in people who were diagnosed with autism and in the rest, however, in the first case, the difference was more pronounced. This means that people whose gender identity does not match their biological sex are more likely to have autistic traits, even if they do not have an autism diagnosis. nine0005

This means that people whose gender identity does not match their biological sex are more likely to have autistic traits, even if they do not have an autism diagnosis. nine0005

Finally, the researchers examined the incidence of six other psychiatric disorders (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, bipolar disorder, depression, schizophrenia, learning disabilities, and obsessive-compulsive disorder) in people of different genders. The frequency of diagnoses of all six disorders (especially schizophrenia and depression) was higher in transgender people and people with non-binary gender (for example, the odds ratio for depression was greater than 3.5; all p < 2 × 10 −16 ).

The authors put forward several hypotheses about why the emergence of mental disorders is associated with gender. First, autistic individuals initially fit less into the usual social norms - perhaps because of this, it is easier for them to recognize that their gender does not match the sex and stereotypical representation of society. Secondly, it is known that some prenatal mechanisms that determine brain development (for example, sex hormones) can be associated with both the development of autism and gender behavior patterns. Finally, transgender people are more vulnerable to mental disorders, as they are subject to stress due to social rejection and discrimination. nine0005

Secondly, it is known that some prenatal mechanisms that determine brain development (for example, sex hormones) can be associated with both the development of autism and gender behavior patterns. Finally, transgender people are more vulnerable to mental disorders, as they are subject to stress due to social rejection and discrimination. nine0005

The concept of gender, its formation and connection with biological sex is the subject of Sally Hines' book Can Gender Change?. On our website you can read an excerpt in which the author explains where the binary model of gender came from, as well as how modern science looks at it.

Alisa Bakhareva

Found a typo? Select the fragment and press Ctrl+Enter.

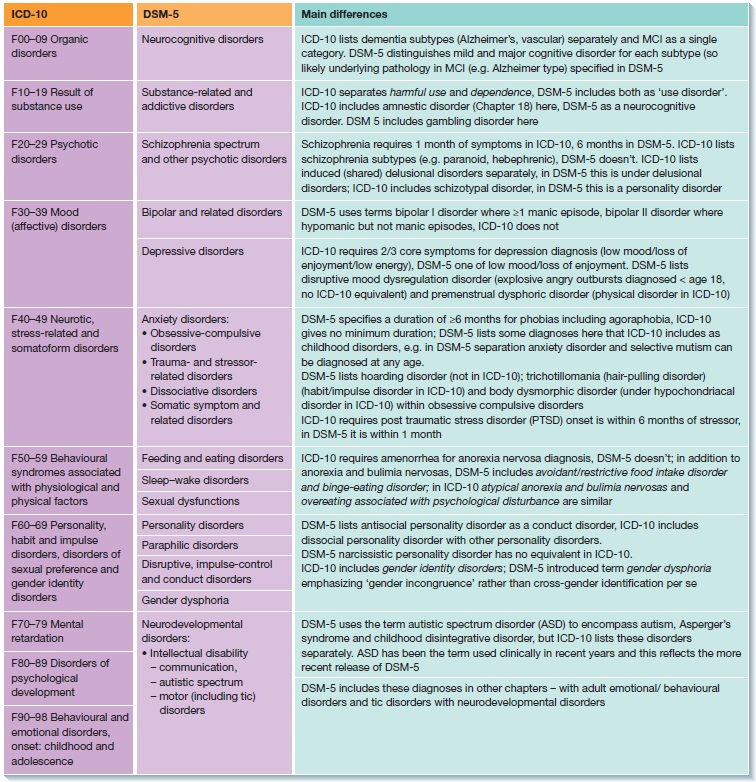

Autistic spectrum disorders in children and adolescents with gender dysphoria

Annelou L. C. De Vries, Ilse L. J. Noens, Peggy T. Cohen-Kettenis, Ina A. Van Berckelaer-Onnes, Theo A. Doreleijers

9000

In this study, co-occurrence is considered using a systematic approach. Children and adolescents (115 boys and 89girls, mean age 10.8, SD 3.58) referred to a gender identity clinic underwent a standard assessment during which GID was diagnosed and suspected cases of ASD were identified. The Dutch version of the Diagnostic Interview for Social and Communication Disorders (10th edition, DISCO-10) was used to classify ASD. The incidence of ASD in this sample of children and adolescents was 7.8% ( n = 16). Clinicians should be aware of the co-occurrence of ASD and GID and the challenges it poses in clinical management.

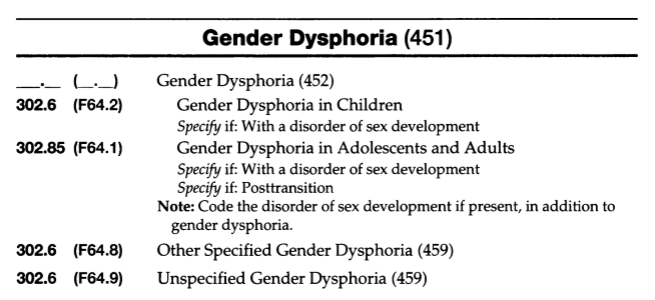

In this study, co-occurrence is considered using a systematic approach. Children and adolescents (115 boys and 89girls, mean age 10.8, SD 3.58) referred to a gender identity clinic underwent a standard assessment during which GID was diagnosed and suspected cases of ASD were identified. The Dutch version of the Diagnostic Interview for Social and Communication Disorders (10th edition, DISCO-10) was used to classify ASD. The incidence of ASD in this sample of children and adolescents was 7.8% ( n = 16). Clinicians should be aware of the co-occurrence of ASD and GID and the challenges it poses in clinical management. Keywords: autism spectrum disorder, gender identity disorder, co-occurrence, frequency of cases The official diagnosis of Gender Identity Disorder (GID) in the DSM-IV-TR is characterized by strong and persistent cross-gender identification, as well as persistent discomfort with one's biological sex and a sense of incongruence with the gender role of that sex (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). The estimated incidence of RGI in adults ranges from 1:10,000 to 1:20,000 in men and from 1:30,000 to 1:50,000 in women (for a review, see Zucker and Lawrence 2009). The prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is in the region of 60 per 10,000 according to various recent studies (for review, see Fombonne 2005), although some studies report rates over 1% (eg Baird et al. 2007). Given the reported prevalence of ASD and GID, an accidental combination should be extremely rare. However, gender identity clinics now report overrepresentation of individuals with ASD among referrals (Robinow and Knudson 2005). The proposed co-occurrence is important not only for diagnostic and organizational reasons, but also raises important theoretical questions - if, indeed, such a relationship is confirmed. nine0005

The estimated incidence of RGI in adults ranges from 1:10,000 to 1:20,000 in men and from 1:30,000 to 1:50,000 in women (for a review, see Zucker and Lawrence 2009). The prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is in the region of 60 per 10,000 according to various recent studies (for review, see Fombonne 2005), although some studies report rates over 1% (eg Baird et al. 2007). Given the reported prevalence of ASD and GID, an accidental combination should be extremely rare. However, gender identity clinics now report overrepresentation of individuals with ASD among referrals (Robinow and Knudson 2005). The proposed co-occurrence is important not only for diagnostic and organizational reasons, but also raises important theoretical questions - if, indeed, such a relationship is confirmed. nine0005

However, no systematic studies have been published to date to measure this co-occurrence. The literature on joint cases of ASD and gender dysphoria consists of seven articles describing nine case histories of individuals with ASD and associated gender identity problems, mostly children (Gallucci et al. 2005; Kraemer et al. 2005; Landen and Rasmussen 1997; Mukaddes 2002; Perera et al. 2003; Tateno et al. 2008; Williams et al. 1996). The authors from different points of view show how they understand the joint occurrence of ASD and gender dysphoria. Some argue that gender dysphoria and autism may indeed be correlated disorders (Mukaddes 2002; Tateno et al. 2008). Others suggest that cross-gender behavior arises from the predisposition to unusual interests that is characteristic of ASD (Williams et al. 1996). It has also been suggested that gender dysphoria in individuals with ASD may be considered an obsessive-compulsive disorder, separate from both ASD and GID (Landen and Rasmussen, 1997; Perera et al. 2003).

2005; Kraemer et al. 2005; Landen and Rasmussen 1997; Mukaddes 2002; Perera et al. 2003; Tateno et al. 2008; Williams et al. 1996). The authors from different points of view show how they understand the joint occurrence of ASD and gender dysphoria. Some argue that gender dysphoria and autism may indeed be correlated disorders (Mukaddes 2002; Tateno et al. 2008). Others suggest that cross-gender behavior arises from the predisposition to unusual interests that is characteristic of ASD (Williams et al. 1996). It has also been suggested that gender dysphoria in individuals with ASD may be considered an obsessive-compulsive disorder, separate from both ASD and GID (Landen and Rasmussen, 1997; Perera et al. 2003).

On the whole, the joint occurrence of gender dysphoria and ASD is currently of interest to medicine. This study was conducted to establish the incidence of ASD in children and adolescents with gender dysphoria and to describe the clinical features of individuals with both gender dysphoria and ASD. nine0005

nine0005

Method

Participants

The study involved 231 children and adolescents referred to the Clinic for Gender Identity at the University Medical Center of the Free University of Amsterdam between April 2004 and October 2007. This is the only clinic in the Netherlands with an interdisciplinary team examining children and adolescents with gender dysphoria. Nineteen children and eight adolescents were excluded from the study because they were unable to complete the assessment process. The reasons for this were the cessation of gender identity problems at the time of the assessment (in some cases due to waiting in line) or serious psychopathologies that led to the need for referral to local mental health clinics and the inability to complete the assessment. As a result, the study group consisted of 108 children (mean age 8.06, standard deviation 1.82) and 96 adolescents (mean age 13.92, standard deviation 2.29), among whom 11 children and 15 adolescents were subsequently identified with suspected ASD.

Procedure

All 204 individuals received a standard clinical evaluation according to the World Professional Association for Transgender Health Standards of Care (Meyer et al. 2001). For children under the age of 12 and for adolescents between 12 and 18, separate protocols were followed, respectively. The protocols included a psychodiagnostic interview with the child or adolescent, interviews with parents about their functioning within the research topic, as well as the developmental history of the child or adolescent, psychological testing by a specially trained psychometrist, and the collection of school information (for a detailed description of the clinical procedure and tools used, see below). in Cohen-Kettenis 2006). nine0005

Persistence of gender dysphoria in children and adolescents with ASD was assessed in 2008 or 2009 after at least 1 year and in some cases 4 years after initial assessment. Clinical data were assessed for those individuals who were still attending the gender identity clinic. If no recent information was available, the parents were contacted.

If no recent information was available, the parents were contacted.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center of the Free University of Amsterdam. Informed consent was obtained from both parents and adolescents aged 12 years and over. nine0005

Taking measurements

Intelligence

IQ was assessed using the Dutch version of the Wechsler intelligence scales for children and adults, depending on the age of the participant (Wechsler 1997; Wechsler et al. 2002).

Autism Spectrum Disorders

Children and adolescents with suspected ASD were identified through discussion at weekly staff meetings of potential ASD characteristics in all new admissions. Further diagnostic evaluation of ASD was considered either when ASD was suspected in early reports or when the examining psychologist or psychiatrist (first author, AV) suspected ASD. The parents or caregivers of individuals with presumed ASD were then invited to an interview for the diagnosis of ASD. ASD diagnoses were confirmed using the 10th edition of the Dutch version of the Diagnostic Interview for Social and Communication Disorders (DISCO-10 Wing 1999; Dutch version Van Berckelaer-Onnes et al. 2003). DISCO-10 was chosen because of its particular effectiveness in diagnosing a wide range of autism spectrum disorders. DISCO is a semi-structured 2-4 hour interview. Its algorithms make it possible to study whether the necessary criteria of various diagnostic systems for ASD are met. During the interview, responses to over 300 questions are coded for computer input. Achieved high cross-validity of items in the DISCO interview, with a kappa coefficient or intra-class correlation of 0.75 or higher for over 80% of interview items (Wing et al. 2002). DISCO-10 was led by two of the authors (IvBO or IN) formally trained in the use of DISCO-10. The diagnostic algorithms used in this study reflect the DSM-IV-TR and ICD-10 criteria for pervasive developmental disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; World Health Organization, 1993).

ASD diagnoses were confirmed using the 10th edition of the Dutch version of the Diagnostic Interview for Social and Communication Disorders (DISCO-10 Wing 1999; Dutch version Van Berckelaer-Onnes et al. 2003). DISCO-10 was chosen because of its particular effectiveness in diagnosing a wide range of autism spectrum disorders. DISCO is a semi-structured 2-4 hour interview. Its algorithms make it possible to study whether the necessary criteria of various diagnostic systems for ASD are met. During the interview, responses to over 300 questions are coded for computer input. Achieved high cross-validity of items in the DISCO interview, with a kappa coefficient or intra-class correlation of 0.75 or higher for over 80% of interview items (Wing et al. 2002). DISCO-10 was led by two of the authors (IvBO or IN) formally trained in the use of DISCO-10. The diagnostic algorithms used in this study reflect the DSM-IV-TR and ICD-10 criteria for pervasive developmental disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; World Health Organization, 1993). Based on DISCO-10, a "permanent" diagnosis, which is retrospective, as well as a "current" diagnosis can be obtained, with "permanent" including "current". This article presents only "permanent" diagnoses.

Based on DISCO-10, a "permanent" diagnosis, which is retrospective, as well as a "current" diagnosis can be obtained, with "permanent" including "current". This article presents only "permanent" diagnoses.

Gender dysphoria

Based on DSM-IV-TR criteria, children and adolescents were classified as having GID, subthreshold GID not specified (GID-NOS), or not having GID (APA 2000). Additionally, a list of Dimensional Diagnostic Criteria of the GID (DDC-GID) was used. This list was compiled by one of the authors (PCK) and describes the DSM-IV-TR subcriteria for GID criteria A and B (cross-gender identification and gender-related discomfort, respectively). Each sub-criteria can be measured by level of strength, persistence, or duration. Whether criteria A and B are met is up to the physician to decide. Criterion C is an exclusion criterion (no intersex). Criterion D (the behavior must show clinically significant distress or impairment) can range from no distress, mild distress, to severe distress (or lack of clarity) in social, occupational, family, or other areas of activity. Diagnostic criteria for GID for DISCO interviewees were specified (eg, sexual orientation, history of childhood GID) using the DDC-GID. In each case, a clinical consensus was reached between the first author (AV) and one of the clinic team members on issues of gender identity in children and adults. nine0005

Diagnostic criteria for GID for DISCO interviewees were specified (eg, sexual orientation, history of childhood GID) using the DDC-GID. In each case, a clinical consensus was reached between the first author (AV) and one of the clinic team members on issues of gender identity in children and adults. nine0005

Analysis

The incidence of ASD was calculated as the percentage of diagnoses confirmed by DISCO of the total number of children and adolescents examined, both individually and collectively. Fisher's exact tests were used to analyze differences in the incidence of ASD among individuals with GID compared with those with GID unspecified.

Independent t - tests.

Specific clinical characteristics and follow-up reports of patients with gender dysphoria were collected from clinical data and described with respect to GID classification, ASD classification, age of onset of GID, persistence of GID diagnosis at follow-up, and, for adolescents, sexual orientation.

Results

Children

According to the DISCO algorithms, seven (six boys, one girl) of 11 children with suspected ASD were diagnosed with ASD. The incidence of ASD among all 108 children evaluated (70 boys, 38 girls) was 6.4% ( n = 7). The incidence of ASD in 52 children diagnosed with GID was 1.9% ( n = 1), which is significantly lower than the incidence of ASD 13% ( n = 6) in 45 children diagnosed with GID unspecified ( p < 0.05). Of the 11 children without a diagnosis of GID, none had ASD.

The mean age of children with ASD ( M = 9.1, SE = 0.47) did not differ significantly from the mean age of children without ASD ( M = 8.0, SE = 0.18, t = -1.63, df Average IQ of children with races ( m = 82.00, SE = 3. 74) was significantly lower than the average IQ of children without races ( m = 103.92, SE = 1.18, T , DF = 101, p < 0.001).

74) was significantly lower than the average IQ of children without races ( m = 103.92, SE = 1.18, T , DF = 101, p < 0.001).

Table 1 presents the specific clinical characteristics of children with both GID and ASD. The most notable results were that six of the seven children with GID and ASD were male, all seven children met the strict criteria for autism disorder, and six of the seven children had less gender dysphoria when summed up at least 1 year after the initial evaluation. nine0005

| No. | Sex | Age | IQ | PAC according to classification | RGI according to classification | Symptoms of RGI: history | At the time of assessment | Later |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Boy | 7 | 88 | nine0209 Autism aRGI unspecified b | From an early age liked jewelry, toys for girls, women's bodies (mother) | Seemed sexually aroused when touching a woman's breasts and dressing up | No RGI to ; at age 10 no more female preferences, still attracted to female bodies with some sexual arousal | |

| 2 | Boy | 8 | nine0209 108Autism | RGI unspecified | Obsessive girl dressing, wearing high heels, interest in makeup | No further interest in girls' toys, no desire to be a girl | No RGI; compulsive dressing reduced by behavioral program at age 10, still wearing high heels | |

| 3 | Boy | 9 | 69 | Autism | RGI unspecified | Played with dolls from an early age, wore dresses, high heels, did makeup | Also likes cars, but wants to be a girl more | No RGI; happy to be a boy at age 12, but still acting girlish, causing problems with peers |

| 4 | Boy | 9 | 75 | Autism | RGI unspecified | From an early age fascinated by mermaids, fairy tales, dolls, ballet, costumes; didn't like his penis | No longer interested in dolls and clothes, currently fascinated by nature and culture, still loves ballet and theater | No RGI; at the age of 10 there is no clear desire to be a girl |

| 5 | Boy | 10 | 95 | Autism | RGI | From an early age was interested in dolls, clothes, pink, wants to be a girl | Wearing girlish clothing is restricted, but looks and acts like a girl with long hair and bright colors | Sustainable GGI; at the age of 12 a clear desire to be a girl |

| 6 | Boy | 10 | 72 | Autism | RGI unspecified | From an early age fascinated by music, dancing, dresses, glitter, long hair, girlish clothes | Also interested in music and girls' clothes, but doesn't want to be a girl | No RGI; at the age of 12 no female preferences, loves music, happy to be a boy |

| 7 | Girl | 10 | 81 | Autism | RGI unspecified | From an early age wears only trousers, short hair, plays with boyish toys | Hates being a girl, but gets angry when called a boy; anxiety due to any medical intervention | No RGI; at the age of 13, happy to be a "tomboy" |

a Autism - Autic disorder

B RGI Unfulfilled - Gender identity disorders Correctly

in RGGI - Disorder of gender identity

In accordance with suspected ASD was diagnosed with ASD. The incidence of ASD among all 96 assessed adolescents (45 boys, 51 girls) was 9.4% ( n = 9). The incidence of ASD among 77 adolescents diagnosed with GID was 6.5% ( n = 5), which is significantly lower than the incidence of ASD 37.5% ( n = 3) in eight adolescents diagnosed with GID unspecified ( p < 0.05). Of 11 adolescents without a diagnosis of GID, one suffered from ASD and transvestism fetishism, but without gender dysphoria.

The incidence of ASD among all 96 assessed adolescents (45 boys, 51 girls) was 9.4% ( n = 9). The incidence of ASD among 77 adolescents diagnosed with GID was 6.5% ( n = 5), which is significantly lower than the incidence of ASD 37.5% ( n = 3) in eight adolescents diagnosed with GID unspecified ( p < 0.05). Of 11 adolescents without a diagnosis of GID, one suffered from ASD and transvestism fetishism, but without gender dysphoria.

The mean age of adolescents with ASD ( M = 15.41, SE = 0.65) was significantly higher than that of adolescents without ASD ( M = 13.77, SE = 0.24, t = -2.09, df The average IQ of adolescents with races ( m = 89.88, SE = 5.52) did not differ significantly from the average IQ of adolescents without races ( m = 96. 67, SE = 1.72, T = 1.20, df = 85, p = 0.23).

67, SE = 1.72, T = 1.20, df = 85, p = 0.23).

Table 2 presents the specific clinical characteristics of adolescents with both GID and ASD. The most notable results were that six out of nine adolescents fully met the strict criteria for autistic disorder (the other three were for Asperger's syndrome), four adolescents were shown to have sex reassignment, two of them were girls, but no one had yet undergone sex reassignment surgery. Two teenagers refused help, and one of them was reported to have undergone sex reassignment surgery abroad. nine0005

| No. | Sex | Age | IQ | PAC according to classification | RGI according to classification | Symptoms of RGI: history | At the time of assessment | Later |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | 12 | 82 | Asperger's a | RGI unspecified b | Children's RGI | Sexual attraction to men | Does not meet the requirements for SP to ; happy to be a tomboy after consultations |

| 2 | Male | 13 | 92 | Autism | RGI d | Children's RGI | No sexual attraction to either boys or girls, no sexual arousal when crossdressing (dressing in clothing of the opposite sex) | SP shown; start of puberty suppression delayed, awaiting start of cross-sex hormones |

| 3 | Male | 14 | 106 | Asperger's | RGI | Children's RGI | Sexual attraction to boys, no sexual arousal with crossdressing | SP shown; start of puberty suppression delayed, currently taking cross-sex hormones |

| 4 | Male | 15 | 62 | Autism | FT e | No children's RGI | Sexual attraction to both girls and boys, sexual arousal in crossdressing | Does not qualify for SP; referred to cognitive behavioral therapy for disturbing sexual arousal |

| 5 | Male | 16 | ID W | Autism | RGI unspecified | Children's RGI, unspecified | Sexual attraction to gay boys, no sexual arousal with crossdressing | Refused help |

| 6 | Male | 16 | 104 | Autism | RGI unspecified | No children's RGI | Sexual attraction to girls; sometimes sexual arousal with crossdressing, in the absence of his sexual motivation | Does not qualify for SP; referred for autism treatment, still has a strong desire to change sex |

| 7 | Female | 17 | 110 | Asperger's | RGI | Children's RGI | Sexual attraction to girls, no sexual arousal with crossdressing | SP shown; start of cross-sex hormones delayed, awaiting mastectomy |

| 8 | nine0209 Male17 | 81 | Autism | RGI | Children's RGI | Sexual attraction to girls, no sexual arousal with crossdressing | Refused help; not wanting to agree with the treatment plan, performed SP surgery abroad | |

| 9 | Female | 18 | 86 | Autism | RGI | Children's RGI | Sexual attraction to girls, no sexual arousal in crossdressing FT - fetishistic transvestism f NA - no data Children and adolescents in the community mean age 10. DiscussionThe incidence of ASD of 7.8% in children and adolescents referred to a gender identity clinic is ten times higher than the prevalence of ASD of 0.6–1% in the general population (Baird et al. 2006; Fombonne 2005) . This important result confirms the clinical impression that ASD is more common in individuals with gender dysphoria than would be expected from random coincidences. nine0005 In the clinical presentation of individuals with comorbid GID and ASD in this study, most notably there is considerable diversity regarding: gender (both male and female), GID classification (GID, GID unspecified, fetishistic transvestism), ASD classification (autistic disorder, Asperger's), age of onset of GID (before or after puberty) and persistence of cross-sexual behavior (stopped or permanent). The overrepresentation of males in our study is consistent with the epidemiology of both ASD and GID (Fombonne 2005; Zucker and Lawrence 2009). Studies of girls with congenital adrenal hyperplasia who were prenatally exposed to high levels of testosterone found that they had more ASD features than controls, and some developed problems with gender identity (Dessens et al. 2005; Knickmeyer et al. 2006). However, the idea that prenatal testosterone may contribute to vulnerability to both ASD and gender dysphoria seems inapplicable in our case, as girls with ASD would then be particularly susceptible to developing gender dysphoria. In addition, exposure to prenatal androgens does not explain why gender dysphoria and ASD can coexist in men. The data obtained once again point to the lack of experimental evidence for the relationship between low testosterone levels and GID in men. nine0005 The symptoms of GID shown by individuals with ASD varied significantly. Individuals with ASD often received a diagnosis of GID, unspecified. While nearly all adolescents with GID experience sexual attraction to people of their own sex (Smith et al. 2005; Wallien and Cohen-Kettenis 2008), most adolescents with gender dysphoria and ASD are sexually attracted to partners of the opposite sex. The majority of individuals with comorbid gender dysphoria and ASD met the strict criteria for autistic disorder. For some young people, the inherent rigidity of ASD can make it extremely difficult to cope with persistent feelings of gender difference. Yet in our society, dealing with this feeling requires considerable flexibility. A normally developing young child (ages 3–5) shows more rigidity in gender-related beliefs than older children; stiffness decreases after five years (Ruble et al. 2007). Individuals with ASD may not achieve this level of flexibility in their gender development. nine0005 Most children with gender dysphoria stop when they reach puberty, while adolescents with GID are likely to continue seeking a gender change into adulthood (Cohen-Kettenis and Pfa¨fflin 2003; Wallien and Cohen-Kettenis 2008; Zucker and Bradley 1995). These results should be considered given the limitations in sampling and evaluation. First of all, we tend to believe that the actual incidence of ASD in children and adolescents referred to a gender clinic is probably higher than the reported percentages. One reason for suggesting underestimation is that some children and adolescents with ASD (diagnosed elsewhere) are unable to be assessed due to severe impairment. In other cases, although ASD features were observed, the parents tended not to report all ASD symptoms in the DISCO-10 interview as they were not the main reason for their concern about the child. Finally, it was not possible to organize a DISCO-10 interview for all participants. The clinic's gender identity specialists identified suspicious cases. Based on the epidemiology of ASD, the majority would be expected to fall into the extended spectrum, whereas in this study, pervasive developmental disorder, unspecified, was not classified even once. Second, those who studied whether the ASD criteria were met knew that the reason for the referral was a possible GID. The study was performed in a clinic specializing in gender identity issues and therefore blinding was not feasible. Third, we studied the population of individuals referred to the gender clinic. Whether the same high co-occurrence of ASD and gender dysphoria will be found in individuals whose primary concern is ASD remains unknown and is of interest for further research. Milder and atypical variants of gender dysphoria can be expected to be found as part of a variety of deviant sexual behaviors and interests, as found in a study of men with ASD (Hellemans et al. 2007). nine0005 Fourth, the categorical classification approach in the DSM-IV-TR is not suitable for studying the more subtle joint manifestations of ASD and GID. Future research should focus on multidimensional measurements and specific cognitive or neuropsychological profiles of individuals with comorbid ASD and GID. Our results for the clinical characteristics of individuals with comorbid gender dysphoria and ASD have implications for caregivers. In all cases described, the diagnostic procedure was extended to determine whether the gender dysphoria developed due to a general sense of "differentness" or to a "core" cross-gender identity. Most useful was the case-by-case approach, which took into account that rigid and concrete reflections on gender roles and difficulties in developing aspects of personal identity may play a role in this process. Thanks. This study was supported by a personal grant to the first author from the Dutch Health Research and Development Organization (ZonMw). The authors thank the families of the surveyed for participating in the study. The results of this study were presented at the 8th International Meeting on Autism Research held in Chicago May 7–9, 2009. The authors report no conflicts of interest. Open access. nine0049 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons non-commercial attribution license, which allows any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original authors and source are acknowledged.

ReferencesAmerican Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. nine0005 Baird, G., Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Chandler, S., Loucas, T., Meldrum, D., et al. (2006). Prevalence of disorders of the autism spectrum in a population cohort of children in South Thames: The special needs and autism project (SNAP). Lancet, 368 (9531), 210–215. Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. (2006). gender identity disorder. In C. Gillberg, R. Harrington, & H. C. Steinhausen (Eds.), A clinician’s handbook of child and adolescent psychiatry (pp. Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., & Pfäfflin, F. (2003). Transgenderism and intersexuality in childhood and adolescence (Vol. 46). Thousand Oaks, London, New Delhi: SAGE Publications. Dessens, A. B., Slijper, F. M., & Drop, S. L. (2005). Gender dysphoria and gender change in chromosomal females with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 34 (4), 389–397. Fombonne, E. (2005). Epidemiology of autistic disorder and other pervasive developmental disorders. nine0048 Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66 (Suppl 10), 3–8. Gallucci, G., Hackerman, F., & Schmidt, C. W. (2005). Gender identity disorder in an adult male with Asperger's syndrome. Sexuality and Disability, 23 (1), 35–40. Hellemans, H., Colson, K., Verbraeken, C., Vermeiren, R., & Deboutte, D. (2007). Sexual behavior in high-functioning male adolescents and young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Knickmeyer, R., Baron-Cohen, S., Fane, B. A., Wheelwright, S., Mathews, G. A., Conway, G. S., et al. (2006). Androgens and autistic traits: A study of individuals with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Hormones and Behavior, 50 (1), 148–153. Kraemer, B., Delsignore, A., Gundelfinger, R., Schnyder, U., & Hepp, U. (2005). Comorbidity of Asperger syndrome and gender identity disorder. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 14 (5), 292–296. Landen, M., & Rasmussen, P. (1997). Gender identity disorder in a girl with autism–a case report. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 6 (3), 170–173. Losh, M., Adolphs, R., Poe, M. D., Couture, S., Penn, D., Baranek, G. T., et al. (2009). Neuropsychological profile of autism and the broad autism phenotype. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66 (5), 518–526. Meyer, W., Bockting, W. O., Cohen-Kettenis, P. Mukaddes, N. M. (2002). Gender identity problems in autistic children. Child: Care, Health and Development, 28 (6), 529–532. Nijmeijer, J. S., Hoekstra, P. J., Minderaa, R. B., Buitelaar, J. K., Altink, M. E., Buschgens, C. J., et al. (2009). PDD symptoms in ADHD, an independent family trait? nine0048 Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37 (3), 443–453. Perera, H., Gadambanathan, T., & Weerasiri, S. (2003). Gender identity disorder presenting in a girl with Asperger's disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder. Ceylon Medical Journal, 48 (2), 57–58. Pine, D. S., Guyer, A. E., Goldwin, M., Towbin, K. A., & Leibenluft, E. (2008). Autism spectrum disorder scale scores in pediatric mood and anxiety disorders. Robinow, O., & Knudson, G. A. (2005). Asperger's disorder and GID. Paper presented at the XIX Biennial symposium of the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association. Ruble, D. N., Taylor, L. J., Cyphers, L., Greulich, F. K., Lurye, L. E., & Shrout, P. E. (2007). The role of gender constancy in early gender development. Child Development, 78 (4), 1121–1136. Smith, Y. L., van Goozen, S. H., Kuiper, A. J., & Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. (2005). Transsexual subtypes: Clinical and theoretical significance. nine0048 Psychiatry Research, 137 (3), 151–160. Tateno, M., Tateno, Y., & Saito, T. (2008). Comorbid childhood gender identity disorder in a boy with Asperger syndrome. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 62 (2), 238. Van Berckelaer-Onnes, I., Noens, I., & Dijkxhoorn, Y. (2003). Diagnostic interview for social and communication disorders—Handleiding. Wallien, M. S., & Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. (2008). Psychosexual outcome of gender-dysphoric children. nine0048 Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47 (12), 1413–1423. Wechsler, D. (1997). Wechsler adult intelligence scale-third edition (WAIS-III), Dutch version (3rd ed.). Lisse, the Netherlands: Swets and Zetlinger. Wechsler, D., Kort, W., Compaan, E. L., Bleichrodt, N., Resing, W. C. M., & Schittkatte, M. (2002). Wechsler intelligence scale for children-third edition (WISC-III) (3rd ed.). Lisse: Swets and Zettlinger. nine0005 Williams, P. G., Allard, A. M., & Sears, L. (1996). Case study: Cross-gender preoccupations with two male children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 26 (6), 635–642. Wing, L. (1999). Diagnostic interview for social and communication disorders. manual. Bromley: Center for Social and Communication Disorders. |

8, standard deviation 3.58). The frequency of ASD in a pooled sample of 129 individuals with a diagnosis of GID was 4.7% ( n = 6), which is significantly lower than the incidence rate of 17.0% ( n = 9) ASD in 53 individuals diagnosed with GID, unspecified ( p < 0.05).

8, standard deviation 3.58). The frequency of ASD in a pooled sample of 129 individuals with a diagnosis of GID was 4.7% ( n = 6), which is significantly lower than the incidence rate of 17.0% ( n = 9) ASD in 53 individuals diagnosed with GID, unspecified ( p < 0.05).

GID, unspecified, was given when cross-gender behaviors and interests were only subthreshold (mainly in children), or atypical or unrealistic. For example, an adolescent with ASD, who always felt different from his peers as a child, but had no history of childhood cross-gender behavior, came to believe that his feeling of alienation was due to gender dysphoria. He hoped that taking estrogens would alleviate his communication problems. In another teenager, cross-gender behavior indicated fetishistic transvestism rather than gender dysphoria. This is consistent with the prevalence of deviant sexual behavior in adolescents and adults with ASD (Hellemans et al. 2007). The female interests of many young boys with gender dysphoria and ASD are associated with soft tissue, luster, and long hair, and may indicate a preference for particular sensory input, typical of ASD. nine0005

GID, unspecified, was given when cross-gender behaviors and interests were only subthreshold (mainly in children), or atypical or unrealistic. For example, an adolescent with ASD, who always felt different from his peers as a child, but had no history of childhood cross-gender behavior, came to believe that his feeling of alienation was due to gender dysphoria. He hoped that taking estrogens would alleviate his communication problems. In another teenager, cross-gender behavior indicated fetishistic transvestism rather than gender dysphoria. This is consistent with the prevalence of deviant sexual behavior in adolescents and adults with ASD (Hellemans et al. 2007). The female interests of many young boys with gender dysphoria and ASD are associated with soft tissue, luster, and long hair, and may indicate a preference for particular sensory input, typical of ASD. nine0005  This may be clinically significant, as adult transsexuals who do not experience same-sex attraction show less satisfactory postoperative functioning in some studies compared to transsexuals who experience it (Smith et al. 2005). nine0005

This may be clinically significant, as adult transsexuals who do not experience same-sex attraction show less satisfactory postoperative functioning in some studies compared to transsexuals who experience it (Smith et al. 2005). nine0005  Similarly, in children under 12 years of age with comorbid ASD, gender dysphoria is relieved, while in adolescents between 12 and 18 years of age, GID remains.

Similarly, in children under 12 years of age with comorbid ASD, gender dysphoria is relieved, while in adolescents between 12 and 18 years of age, GID remains.  This may indicate a high threshold of suspicion for ASD among our clinicians, as their focus is on gender dysphoria. nine0005

This may indicate a high threshold of suspicion for ASD among our clinicians, as their focus is on gender dysphoria. nine0005  For example, observed rigidity in gender-related beliefs in young children may make children with ASD more likely to develop gender dysphoria (Ruble et al. 2007). In addition, it seems important in future studies of the gender clinic referral population to address the extended autism phenotype (clinical features that are milder but qualitatively similar to those of autism (Losh et al. 2009).)). It is possible that these traits are more common in individuals with gender dysphoria than full-blown ASD, as has been found, for example, in children with mood disorders, anxiety disorder, and ADHD (Nijmeijer et al. 2009; Pine et al. 2008).

For example, observed rigidity in gender-related beliefs in young children may make children with ASD more likely to develop gender dysphoria (Ruble et al. 2007). In addition, it seems important in future studies of the gender clinic referral population to address the extended autism phenotype (clinical features that are milder but qualitatively similar to those of autism (Losh et al. 2009).)). It is possible that these traits are more common in individuals with gender dysphoria than full-blown ASD, as has been found, for example, in children with mood disorders, anxiety disorder, and ADHD (Nijmeijer et al. 2009; Pine et al. 2008).  RAS should not be a strict exclusion criterion for gender reassignment. Only one case report describes a woman with Asperger's who underwent sex reassignment (Kraemer et al. 2005), but we know more from clinical practice. In our sample, almost half of adolescents with both ASD and GID have started a gender reassignment. It is worrying that teens who opt out of care are likely to find their own gender transition paths without psychiatric treatment or medical attention. The challenge of providing appropriate care for individuals with comorbid gender dysphoria and ASD remains a major challenge. nine0005

RAS should not be a strict exclusion criterion for gender reassignment. Only one case report describes a woman with Asperger's who underwent sex reassignment (Kraemer et al. 2005), but we know more from clinical practice. In our sample, almost half of adolescents with both ASD and GID have started a gender reassignment. It is worrying that teens who opt out of care are likely to find their own gender transition paths without psychiatric treatment or medical attention. The challenge of providing appropriate care for individuals with comorbid gender dysphoria and ASD remains a major challenge. nine0005

695–725). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

695–725). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.  Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37 (2), 260–269.

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37 (2), 260–269.  T., Coleman, E., Di Ceglie, D., Devor, H., et al. (2001). nine0048 Standards of care for gender identity disorders of the Harry Benjamin international gender dysphoria association, 6th edn. Retrieved May 25, 2007, from http://www.wpath.org/.

T., Coleman, E., Di Ceglie, D., Devor, H., et al. (2001). nine0048 Standards of care for gender identity disorders of the Harry Benjamin international gender dysphoria association, 6th edn. Retrieved May 25, 2007, from http://www.wpath.org/.  Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47 (6), 652–661.

Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47 (6), 652–661.  Leiden: University of Leiden.

Leiden: University of Leiden.