What is the prodromal stage

Early signs, diagnosis and therapeutics of the prodromal phase of schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

• of interest

•• of considerable interest

1. Bleuler E. In: Dementia Praecox of the Group of Schizophrenias. Zinkin J, editor. NY, USA: International Universities Press; 1950. (1911) (Translator) [Google Scholar]

2. Kraepelin E, Barclay R, Robertson GM. Dementia Praecox and Paraphrenia. Edinburgh, UK: E & S Livingstone; 1919. [Google Scholar]

3. Hughlings-Jackson J. Intellectual warnings of epileptic seizures. In: Taylor J, editor. Selected Writings of John Hughlings-Jackson. London, UK: Hodder and Stoughton; 1931. pp. 274–275. [Google Scholar]

4. Strauss J, Carpenter W. The prediction of outcome in schizophrenia: II. Relationships between predictors and outcome variables. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1974;31:37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Andreasen N, Olsen S. Negative v positive schizophrenia: definition and validation. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1982;39:789–794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Andreasen N, Grove W. Evaluation of positive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Psychobiol. 1986;1:108–121. [Google Scholar]

7. Schneider K. In: Clinical Psychopathology. Hamilton MW, editor. NY, USA: Grune and Stratton Inc; 1959. (Translator) [Google Scholar]

8. Carpenter WT, Strauss JS, Muleh S. Are there pathognomonic symptoms in schizophrenia: an empiric investigation of Schneider’s first-rank symptom. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1973;28:847–852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Liddle P. The symptoms of chronic schizophrenia: a re-examination of the positive–negative dichotomy. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1987;151:145–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Nuechterlein KH, Barch DM, Gold JM, Goldberg TE, Green MF, Heaton RK. Identification of separable cognitive factors in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2004;72:29–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Mesholam-Gately RI, Giuliano AJ, Goff KP, Faraone SV, Seidman LJ. Neurocognition in first-episode schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Neuropsychology. 2009;23:315–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Neurocognition in first-episode schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Neuropsychology. 2009;23:315–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Meltzer HY, Thompson PA, Lee MA, Ranjan R. Neuropsychologic deficits in schizophrenia: relation to social function and effect of antipsychotic drug treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;14:S27–S33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Green MF, Kern RS, Braff DL, Mintz J. Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the ‘right stuff?’ Schizophr. Bull. 2000;26:119–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. McGurk SR, Meltzer HY. The role of cognition in vocational functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2000;45:175–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Leeson VC, Barnes TRE, Hutton SB, Ron MA, Joyce EM. IQ as a predictor of functional outcome in schizophrenia: a longitudinal, four-year study of first-episode psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 2009;107:55–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Gold JM, Hahn B, Strauss GP, Waltz JA. Turning it upside down: areas of preserved cognitive function in schizophrenia. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2009;19:294–311. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gold JM, Hahn B, Strauss GP, Waltz JA. Turning it upside down: areas of preserved cognitive function in schizophrenia. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2009;19:294–311. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Malla A, Payne J. First-episode psychosis: psychopathology, quality of life, and functional outcome. Schizophr. Bull. 2005;31:650–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Brewer WJ, Wood SJ, Phillips LJ, et al. Generalized and specific cognitive performance in clinical high-risk cohorts: a review highlighting potential vulnerability markers for psychosis. Schizophr. Bull. 2006;32:538–555. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Murray RM, Lewis SW. Is schizophrenia a neurodevelopmental disorder? Br. Med. J. 1987;295:681–682. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Davidson M, Reichenberg A, Rabinowitz J, Weiser M, Kaplan Z, Mark M. Behavioural and intellectual markers for schizophrenia in apparently healthy male adolescents. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1999;156:1328–1335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Munro JC, Russell AJ, Murray RM, Kerwin RW, Jones PB. IQ in childhood psychiatric attendees predicts outcome of later schizophrenia at 21 year follow-up. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2002;106:139–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Schenkel LS, Silverstein SM. Dimensions of premorbid functioning in schizophrenia: a review of neuromotor, cognitive, social, and behavioral domains. Genet. Soc. Gen. Psychol. Monogr. 2004;130:241–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Walker E. Developmentally moderated expressions of the neuropathology of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 1994;20:453–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Walker E, Lewis N, Loewy R, Palyo S. Motor dysfunction and risk for schizophrenia. Dev. Psychopathol. 1999;11:509–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Zipursky R, Christensen B, Mikulis D. Stable deficits in gray matter volumes following a first episode of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2004;71:515–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Marshall M, Lewis S, Lockwood A, Drake R, Jones P, Croudace T. Association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in cohorts of first-episode outcome patients: a systematic review. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2005;62:975–983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marshall M, Lewis S, Lockwood A, Drake R, Jones P, Croudace T. Association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in cohorts of first-episode outcome patients: a systematic review. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2005;62:975–983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, Lieberman JA. Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2005;162:1785–1804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Barnes TRE, Leeson VC, Mutsatsa SH, Watt HC, Hutton SB, Joyce EM. Duration of untreated psychosis and social function: 1-year follow-up study of first-episode schizophrenia. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2008;193:203–209. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Addington J, Van Mastrigt S, Addington D. Duration of untreated psychosis: impact on 2-year outcome. Psychol. Med. 2004;34:277–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Harrington SM, McGorry PD, Krstev H. Does treatment delay in first-episode psychosis really matter? Psychol. Med. 2003;33:97–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Med. 2003;33:97–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Shenton M, Dickey C, Frumin M, McCarley R. A review of MRI findings in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2001;49:1–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Vita A, De Peri L, Silenzi C, Dieci M. Brain morphology in first-episode schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of quantitative magnetic resonance imaging studies. Schizophr. Res. 2006;82:75–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Wright I, Rabe-Hesketh S, Woodruff P, David A, Murray R, Bullmore E. Meta-analysis of regional brain volumes in schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2000;157:16–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Lappin J, Morgan K, Morgan C, et al. Gray matter abnormalities associated with duration of untreated psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 2006;83:145–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Pantelis C, Velakoulis D, McGorry PD, et al. Neuroanatomical abnormalities before and after onset of psychosis: a cross-sectional and longitudinal MRI comparison. Lancet. 2003;361:281–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2003;361:281–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Lieberman JA, Malaspina D, Jarskog LF. Preventing clinical deterioration in the course of schizophrenia: the potential for neuroprotection. Prim. Psychiatry. 2006;13:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. McGlashan TH, Miller TJ, Woods SW. Pre-onset detection and intervention research in schizophrenia psychoses: current estimates of benefit and risk. Schizophr. Bull. 2001;27:563–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Phillips LJ, McGorry P, Yung AR, McGlashan TH, Cornblatt B, Klosterkotter J. Prepsychotic phase of schizophrenia and related disorders: recent progress and future opportunities. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2005;187:33–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Cornblatt BA, Lencz T, Smith CW, Cornell CU, Auther AM, Nakayama E. The schizophrenia prodrome revisited: a neurodevelopmental perspective. Schizophr. Bull. 2003;29:633–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Schultze-Lutter F, Ruhrmann S, Berning J, Maier W, Klosterkotter J. Basic symptoms and ultrahigh risk criteria: symptom development in the initial prodromal state. Schizophr. Bull. 2010;36:182–191. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Basic symptoms and ultrahigh risk criteria: symptom development in the initial prodromal state. Schizophr. Bull. 2010;36:182–191. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. an der Heiden W, Hafner H. The epidemiology of onset and course of schizophrenia. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2000;250:292–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Rosen JL, Miller TJ, D’Andrea JT, McGlashan TH, Woods SW. Comorbid diagnoses in patients meeting criteria for the schizophrenia prodrome. Schizophr. Res. 2006;85:124–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Gross G, Huber G, Klosterkotter J, Linz M. BSABS: Bonn Scale for the Assessment of Basic Symptoms. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 1987. [Google Scholar]

44. Yung AR, McGorry PD. The initial prodrome in psychosis: descriptive and qualitative aspects. Aust. NZ J. Psychiatry. 1996;30:587–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Schultze-Lutter F, Klosterkotter J. Bonn Scale for the Assessment of Basic Symptoms – prediction list, BSABS-P. Cologne, Germany: University of Cologne; 2002. [Google Scholar]

Cologne, Germany: University of Cologne; 2002. [Google Scholar]

46. Klosterkotter J, Hellmich M, Steinmeyer EM, Schultze-Lutter F. Diagnosing schizophrenia in the initial prodromal phase. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2001;58:158–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Siever LJ, Davis KL. The pathophysiology of schizophrenia disorders: perspectives from the spectrum. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2004;161:398–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Olsen KA, Rosenbaum B. Prospective investigations of the prodromal state of schizophrenia: review of studies. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2006;113:247–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Yung AR, Yuen HP, McGorry PD, Phillips LJ, Kelly D, Dell’Olio M. Mapping the onset of psychosis: the comprehensive assessment of at-risk mental states. Aust. NZ J. Psychiatry. 2005;39:964–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Yung AR, McGorry PD. The prodromal phase of first episode psychosis: past and current conceptualizations. Schizophr. Bull. 1996;22:353–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. McGorry PD, Yung AR, Phillips LJ. Ethics and early intervention in psychosis: keeping up the pace and staying in step. Schizophr. Res. 2001;51:17–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. de Koning MB, Bloemen OJN, van Amelsvoort TAMJ, et al. Early intervention in patients at ultra high risk of psychosis: benefits and risks. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2009;119:426–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Cadenhead K. Vulnerability markers in the schizophrenia spectrum: implications for phenomenology, genetics, and the identification of the schizophrenia prodrome. Psychiatry Clin. N. Am. 2002;25:837–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Mason O, Startup M, Halpin S, Schall U, Conrad A, Carr V. Risk factors for transition to first episode psychosis among individuals with “at-risk mental states” Schizophr. Res. 2004;71:227–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. McGlashan TH, Zipursky RB, Perkins DO, et al. The PRIME North American randomized double-blind clinical trial of olanzapine versus placebo in patients at risk of being prodromally symptomatic for psychosis. I. Study rationale and design. Schizophr. Res. 2003;61:7–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

I. Study rationale and design. Schizophr. Res. 2003;61:7–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, Cadenhead DO, Ventura J, McFarlane CA. Prodromal assessment with the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes and the Scale of Prodromal Symptoms: predictive validity, interrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophr. Bull. 2003;29:703–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Morrison AP, French P, Walford L, et al. Cognitive therapy for the prevention of psychosis in people at ultra-high risk. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2004;185:291–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] •• Seminal article on the first well-designed psychological intervention in ultra-high-risk (UHR) participants.

58. Nieman DH, Rike WH, Becker HE, et al. Prescription of antipsychotic medication to patients at ultra high risk of developing psychosis. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2009;24:223–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Cannon TD, Cadenhead K, Cornblatt B, et al. Prediction of psychosis in youth at high clinical risk: a multisite longitudinal study in North America. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2008;65:28–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2008;65:28–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Yuen HP, McGorry PD. Risk factors for psychosis in an ultra high-risk group: psychopathology and clinical features. Schizophr. Res. 2004;67:131–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Bak M, Delespaul P, Hanssen M, de Graaf R, Vollebergh W, van Os J. How false are “false” positive psychotic symptoms? Schizophr. Res. 2003;62:187–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Yung AR, Yuen HP, Berger G, et al. Declining transition rate in ultra high risk (prodromal) services: dilution or reduction of risk? Schizophr. Bull. 2007;33:673–681. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Green MF. What are the functional consequences of the neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? Am. J. Psychiatry. 1996;153:321–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Harvey PD, Howanitz E, Parrella M, et al. Symptoms, cognitive functioning, and adaptive skills in geriatric patients with lifelong schizophrenia: a comparison across treatment sites. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1998;155:1080–1086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Am. J. Psychiatry. 1998;155:1080–1086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Harvey PD, Silverman JM, Mohs RC, et al. Cognitive decline in late-life schizophrenia: a longitudinal study of geriatric chronically hospitalized patients. Biol. Psychiatry. 1999;45:32–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Jahshan C, Heaton RK, Golshan S, Cadenhead KS. Course of neurocognitive deficits in the prodrome and first episode of schizophrenia. Neuropsychology. 2010;24:109–120. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Bersani G, Orlandi V, Kotzalidis GD, Pancheri P. Cannabis and schizophrenia: impact on onset, course, psychopathology and outcomes. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2002;252:86–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Boydell J, Dean K, Dutta R, Giouroukou E, Fearon P, Murray R. A comparison of symptoms and family history in schizophrenia with and without prior cannabis use: implications for the concept of cannabis psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 2007;93:203–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Hambrecht M, Hafner H. Cannabis, vulnerability, and the onset of schizophrenia: an epidemiological perspective. Aust. NZ J. Psychiatry. 2000;34:468–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] • Clearly delineates various pathways of potential effects of cannabis on the course of schizophrenia.

Hambrecht M, Hafner H. Cannabis, vulnerability, and the onset of schizophrenia: an epidemiological perspective. Aust. NZ J. Psychiatry. 2000;34:468–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] • Clearly delineates various pathways of potential effects of cannabis on the course of schizophrenia.

70. Cassano GB, Pini S, Saettoni M, Rucci P, Dell’Osso L. Occurrence and clinical correlates of psychiatric comorbididty in patients with psychotic disorders. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 1998;59:60–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Stefanis NC, Delespaul P, Henquet C, Bakoula C, Stefanis CN, Van Os J. Early adolescent cannabis exposure and positive and negative dimensions of psychosis. Addiction. 2004;99:1333–1341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Compton MT, Weiss PS, West JC, Kaslow NJ. The associations between substance use disorders, schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, and Axis IV psychosocial problems. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2005;40:939–946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

73. Drake RE, Wallach MA. Substance abuse among the chronic mentally ill. Hosp. Community Psychiatry. 1989;40:1041–1046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Substance abuse among the chronic mentally ill. Hosp. Community Psychiatry. 1989;40:1041–1046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

74. D’Souza DC, Abi-Saab WM, Madonick S, Forselius-Bielen K, Doersch A, Braley G. δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol effects in schizophrenia: implications for cognition, psychosis, and addiction. Biol. Psychiatry. 2005;57:594–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

75. Kavanagh DJ. Management of co-occuring substance use disorders. In: Mueser KT, Jeste DV, editors. Clinical Handbook of Schizophrenia. NY, USA: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 459–470. [Google Scholar]

76. Compton MT, Goulding SM, Walker EF. Cannabis use, first-episode psychosis, and schizotypy: a summary and synthesis of recent literature. Curr. Psychiatry Rev. 2007;3:161–171. [Google Scholar]

77. Arseneault LM, Cannon M, Witton J, Murray M. Causal association between cannabis and psychosis: examination of the evidence. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2004;184:110–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] • Rigorous review of prospective studies addressing the potential causal association between cannabis use and risk of developing psychosis.

78. Phillips LJ, Curry C, Yung AR, Yuen HP, Adlard S, McGorry PD. Cannabis use is not associated with development of psychosis in an ‘ultra’ high-risk group. Aust. NZ J. Psychiatry. 2002;36:800–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

79. Kristensen K, Cadenhead KS. Cannabis abuse and risk for psychosis in a prodromal sample. Psychiatry Res. 2007;151:151–154. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

80. Cannon T. Neurodevelopment and the transition from schizophrenia prodrome to schizophrenia: research imperatives. Biol. Psychiatry. 2008;64:737–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

81. McGorry PD, Nelson B, Amminger P, et al. Intervention in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis: a review and future directions. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2009;70:1206–1212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] • Succinct review of the influence of interventions tested in UHR individuals.

82. Goetz D, Goetz R, Yale S, et al. Comparing early and chronic psychosis clinical characteristics. Schizophr. Res. 2004;70:120. [Google Scholar]

Schizophr. Res. 2004;70:120. [Google Scholar]

83. Lieberman JA, Tollefson GD, Charles C, et al. Antipsychotic drug effects on brain morphology in first-episode psychosis. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2005;62:361–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

84. Keefe RSE, Silva SG, Perkins DO, Lieberman JA. The effects of atypical antipsychotic drugs on neurocognitive impairment in schizophrenia: a review and meta-analysis. Schizophr. Bull. 1999;25:201–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

85. Keefe RSE, Sweeney JA, Hongbin G, Hamer RM, Perkins DO, McEvoy JP. Effects of olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone on neurocognitive function in early psychosis: a randomized, double-blind 52-week comparison. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2007;164:1061–1071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

86. Tandon R, DeQuardo J, Taylor S, et al. Phasic and enduring negative symptoms in schizophrenia: Biological markers and relationship to outcome. Schizophr. Res. 2000;45:191–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

87. Meltzer HY, Thompson PA, Lee MA, Ranjan R. Neuropsychologic deficits in schizophrenia: relation to social function and effect of antipsychotic drug treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;14:S27–S33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Neuropsychologic deficits in schizophrenia: relation to social function and effect of antipsychotic drug treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;14:S27–S33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

88. McGurk SR, Meltzer HY. The role of cognition in vocational functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2000;45:175–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

89. McGorry PD, Yung AR, Phillips LJ, et al. Randomized controlled trial of interventions designed to reduce the risk of progression to first-episode psychosis in a clinical sample with subthreshold symptoms. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2002;59:921–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] •• Seminal article on the first randomized, controlled pharmacological intervention in UHR participants.

90. Phillips LJ, McGorry PD, Yuen JP, et al. Medium term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of interventions for young people at ultra high risk of psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 2007;96:25–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

91. Cannon TD, van Erp TG, Rosso IM, et al. Fetal hypoxia and structural brain abnormalities in schizophrenic patients, their siblings, and controls. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2002;59:35–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fetal hypoxia and structural brain abnormalities in schizophrenic patients, their siblings, and controls. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2002;59:35–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

92. Woods SW, Breier A, Zipursky RB, et al. Randomized trial of olanzapine versus placebo in the symptomatic acute treatment of the schizophrenic prodrome. Biol. Psychiatry. 2003;54:453–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

93. McGlashan TH, Zipursky RB, Perkins DO. Randomized, double-blind trial of olanzapine versus placebo in patients prodromally symptomatic for psychosis. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2006;163:790–799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

94. Woods SW, Tully EM, Walsh BC, Hawkins KA, Callahan JL, Cohen SJ. Aripiprazole in the treatment of the psychosis prodrome: an open-label pilot study. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2007;191:S96–S101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

95. Ruhrmann S, Bechdolf A, Kuhn K-U, Wagner M, Schultze-Lutter F, Janssen B. Acute effects of treatment for prodromal symptoms for people putatively in a late initial prodromal state of psychosis. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2007;191:S88–S95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Br. J. Psychiatry. 2007;191:S88–S95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

96. Moncrieff J. Does antipsychotic withdrawal provoke psychosis? Review of the literature on rapid onset psychosis (supersensitivity psychosis) and withdrawal-related relapse. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2006;114:3–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

97. Cornblatt BA, Lencz T, Smith CW, et al. Can antidepressants be used to treat the schizophrenia prodrome? Results of a prospective, naturalistic treatment study of adolescents. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2007;68:546–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

98. Fusor-Poli P, Valmaggia L, McGuire P. Can antidepressants prevent psychosis? Lancet. 2007;370:1746–1748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

99. Walker EF, Cornblatt BA, Addington J, et al. The relation of antipsychotic and antidepressant medication with baseline symptoms and symptom progression: a naturalistic study of the North American Prodrome Longitudinal sample. Schizophr. Res. 2009;115:50–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

100. Benton MK, Schroeder HE. Social skills training with schizophrenics: a meta-analytic evaluation. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1990;58:741–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Benton MK, Schroeder HE. Social skills training with schizophrenics: a meta-analytic evaluation. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1990;58:741–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

101. Combs DR, Adams SD, Penn DL, Roberts D, Tiegreen J, Stern P. Social cognition and interaction traning (SCIT) for inpatients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: preliminary findings. Schizophr. Res. 2007;91:112–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

102. Pitschel-Walz G, Leucht S, Bauml J, Kissling W, Engel RR. The effect of family interventions on relapse and rehospitalization in schizophrenia – a meta-analysis. Schizophr. Bull. 2001;27:73–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

103. McGurk SR, Twamley EW, Sitzer DI, McHugo GJ, Mueser KT. A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2007;164:1791–1802. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

104. Gould RA, Mueser KT, Bolton E, Mays V, Goff D. Cognitive therapy for psychosis in schizophrenia: an effect size analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2001;48:3335–3342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Res. 2001;48:3335–3342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

105. Gaudiano BA. Is symptomatic improvement in clinical trials of cognitive–behavioral therapy for psychosis clinically significant? J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2006;12:11–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

106. Pilling S, Bebbington P, Kuipers E, et al. Psychological treatments in schizophrenia: II. Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of social skills training and cognitive remediation. Psychol. Med. 2002;32:783–791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

107. Rathod S, Turkington D. Cognitive–behavioral therapy for schizophrenia: a review. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 2005;18:159–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

108. Turkington D, Dudley R, Warman DM, Beck AT. Cognitive–behavioral therapy for schizophrenia: a review. J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2004;10:5–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

109. Zimmerman G, Favrod J, Trieu VH, Pomini V. The effect of cognitive behavioral treatment on the positive symptoms of schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2005;77:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schizophr. Res. 2005;77:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

110. Falloon IR. Early intervention for first episodes of schizophrenia: a preliminary exploration. Psychiatry. 1992;55:4–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

111. Morrison AP, French P, Parker S, et al. Three-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of cognitive therapy for the prevention of psychosis in people at ultrahigh risk. Schizophr. Bull. 2007;33:682–687. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

112. Bechdolf A, Wagner M, Veith V, et al. Randomized controlled multicentre trial of cognitive behavior therapy in the early intitial prodromal state: effects on social adjustment post treatment. Early Intervent. Psychiatry. 2007;1:71–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

113. Nordentoft M, Thorup A, Petersen L, et al. Transition rates from schizotypal disorder to psychotic disorder for first-contact patients included in the OPUS trail. A randomized clinical trial of integrated treatment and standard treatment. Schizophr. Res. 2006;83:29–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schizophr. Res. 2006;83:29–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

114. Berger GE, Smesny S, Amminger GP. Bioactive lipids in schizophrenia. Int. Rev. Psychiatry. 2006;18:85–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

115. Amminger GP, Berger GE, Schzfer MR, Klier C, Friedrich MH, Feucht M. Omega-3 fatty acids supplementation in children with autism: a double-blind randomized, placebo-controlled pilot study. Biol. Psychiatry. 2007;61:551–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

116. Berger GE, Proffitt T-M, McConchie M, Yuen JP, Wood SJ, Amminger P. Ethyl-eicosapentaenoic acid in first-episode psychosis: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2007;68:1867–1875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

117. Emsley R, Myburgh C, Oosthuizen P, van Rensburg SJ. Randomized, placebo-controlled study of ethyl-eicosapentaenoic acid as supplemental treatment in schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2002;159:1596–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

118. Richardson AJ, Montgomery P. The Oxford–Durham study: a randomized, controlled trial of dietary supplementation with fatty acids in children with developmental coordination disorder. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1360–1366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pediatrics. 2005;115:1360–1366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

119. Amminger GP, Schaefer MR, Papageorgiou K, et al. Omega 3 fatty acids reduce the risk of early transition to psychosis in ultra-high risk individuals: a double-blind randomized, placebo-controlled treatment study. Schizophr. Bull. 2007;33 Suppl:418–419. [Google Scholar]

120. Amminger GP, Schaefer MR, Papageorgiou K, Klier CM, Cotton SM, Harrigan SM. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids for indicated prevention of psychiatric disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2010;67:146–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] •• Important study demonstrating significant outcomes of a low-risk, effective treatment for UHR individuals.

121. Cornblatt BA, Lencz T, Kane JM. Treatment of the schizophrenia prodrome: is it presently ethical? Schizophr. Res. 2001;51:31–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

122. McGorry PD, Yung A, Phillips L. Ethics and early intervention in psychosis: keeping up the pace and staying in step. Schizophr. Res. 2001;51:17–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

123. McGlashan T. Psychosis treatment prior to psychosis onset: ethical issues. Schizophr. Res. 2001;51:47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

124. Haroun N, Dunn L, Haroun A, Cadenhead KS. Risk and protection in prodromal schizophrenia: ethical implications for clinical practice and future research. Schizophr. Bull. 2006;32:166–178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

125. McGlashan TH. Early detection and intervention in psychosis: an ethical paradigm shift. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2005;187:S113–S115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

126. Compton MR, Goulding SM, Ramsay CE, Addington J, Corcoran C, Walker EF. Early detection and intervention for psychosis: perspectives from North America. Clin. Neuropsychiatry. 2008;5:263–272. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

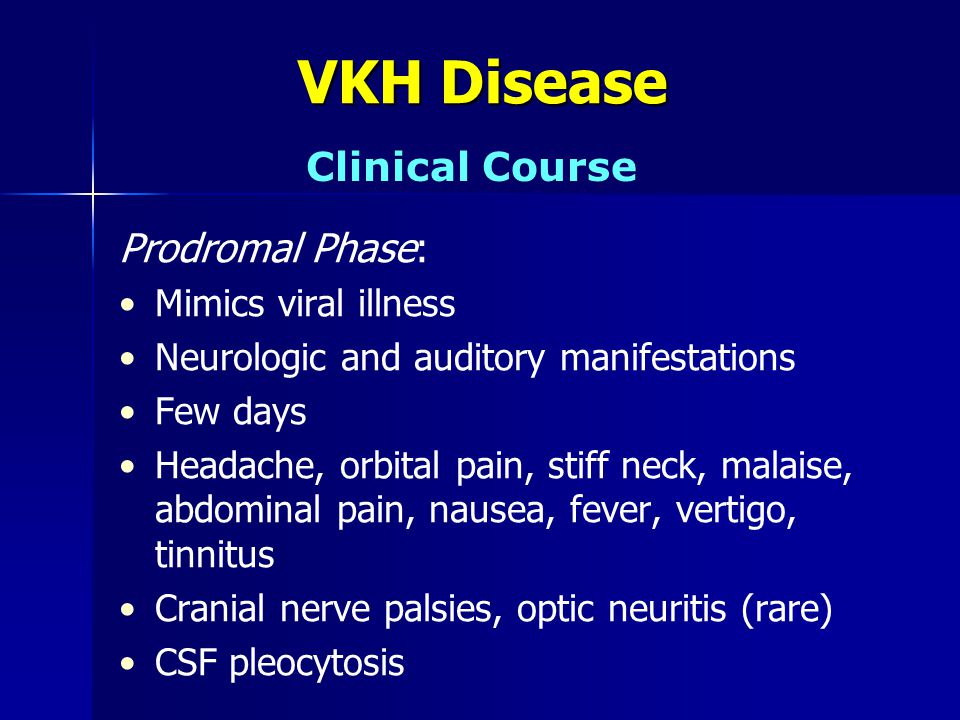

Prodromal period - Definition and Examples

Prodromal period

n., [pɹəʊˈdɹəʊməl ˈpɪərɪəd]

Definition: Stage of a disease wherein the early signs and symptoms appear but not yet clinically specific nor severe

Table of Contents

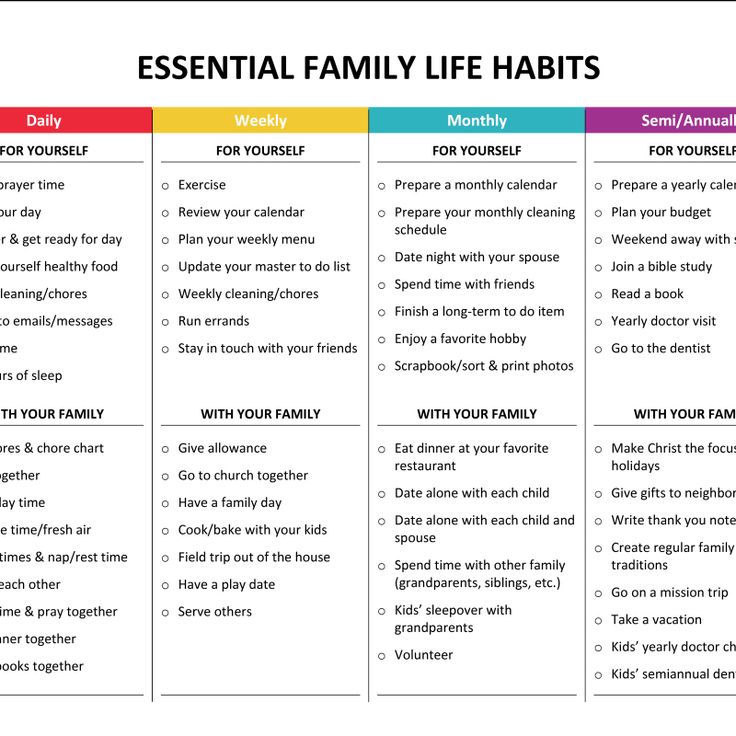

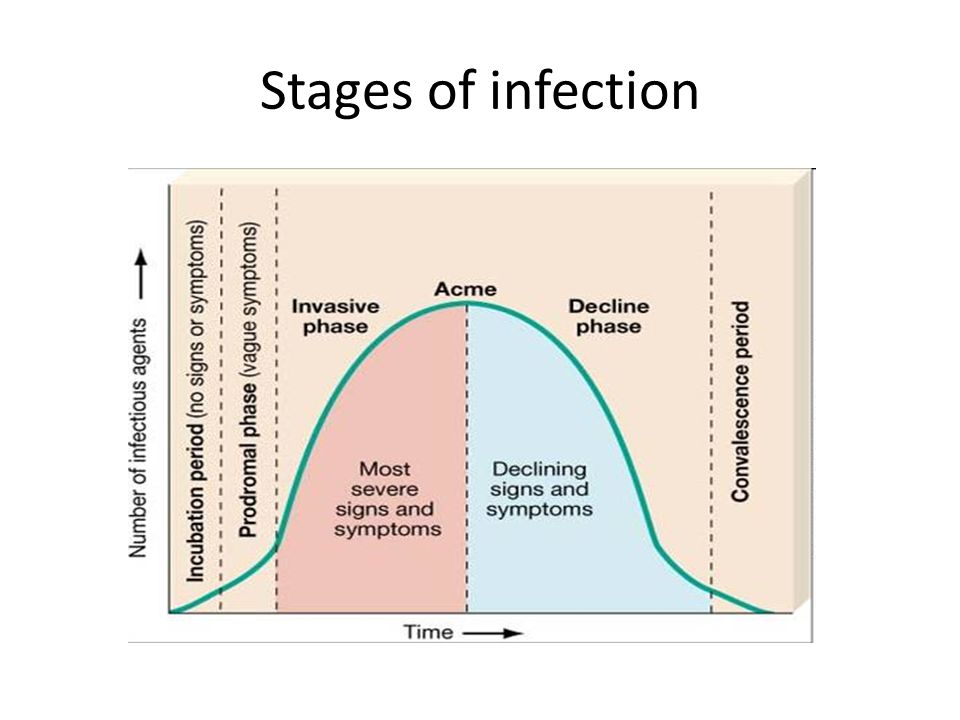

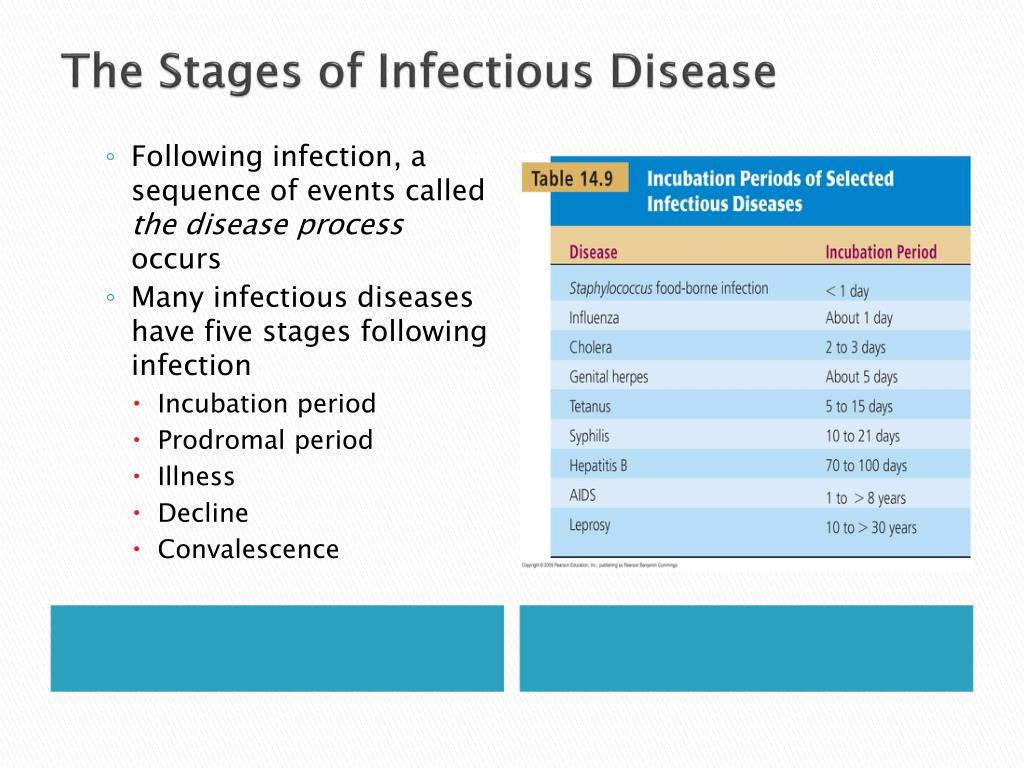

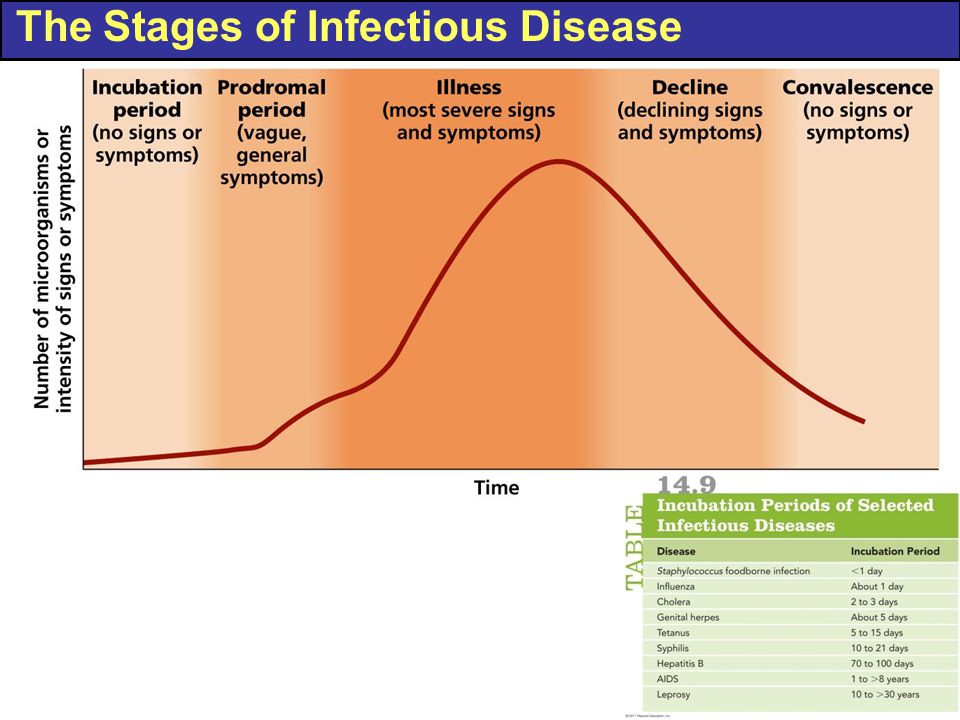

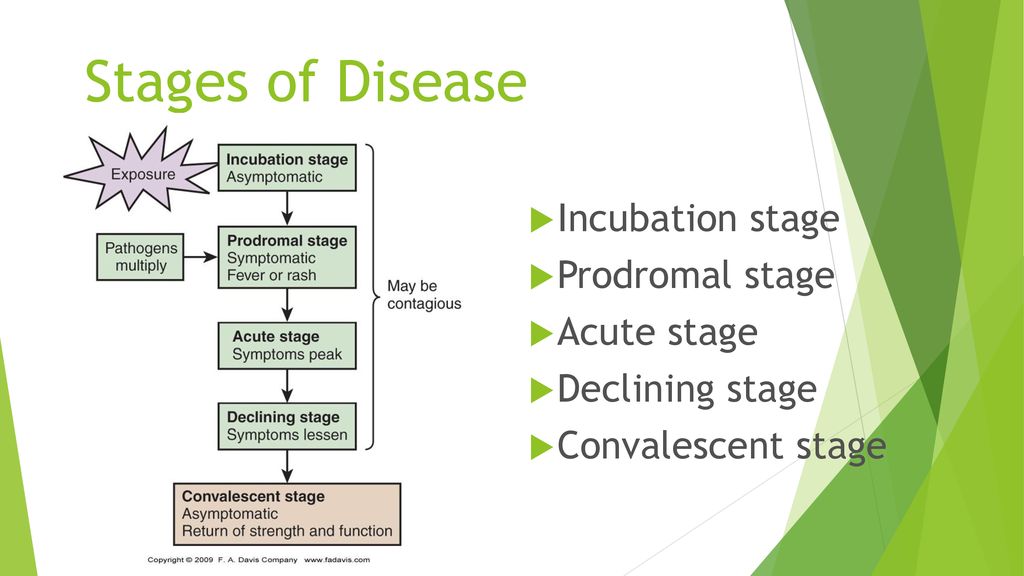

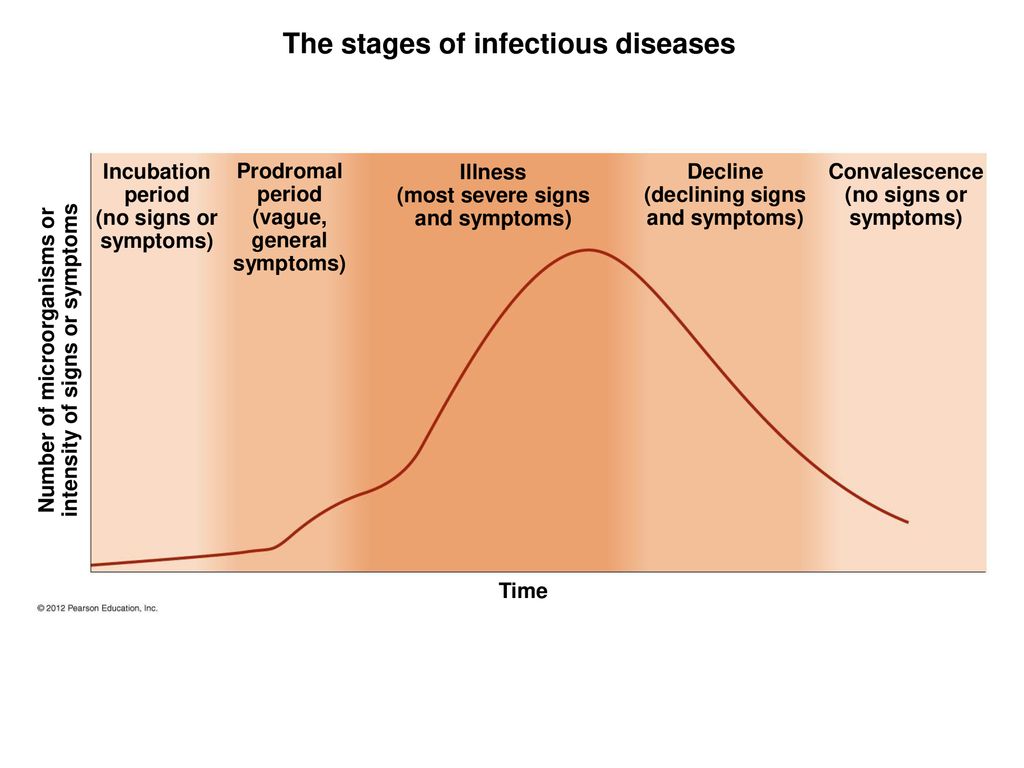

There are five stages (or phases) of a disease. (Hattis, 2020). These stages are (1) Incubation period, (2) Prodromal period, (3) Illness period, (4) Decline period, and (5) Convalescence period.

(Hattis, 2020). These stages are (1) Incubation period, (2) Prodromal period, (3) Illness period, (4) Decline period, and (5) Convalescence period.

Prodromal Period Definition

The prodromal period is also known as the prodromal stage. In this stage of the disease, there is an increase in the number of infections causing the immune system of the body to start to react against infectious agents. We can also define the prodromal period as a phase where the number of pathogens continues to increase. Before the specific symptoms of the disease appear, some early symptoms start appearing in this phase.

Biology definition:

The prodromal period is the period characterized by the presence of early signs and nonspecific symptoms of a disease. It is the period between the incubation period and the illness period. During this period, the symptoms are not highly specific and the affected individual may feel discomfort but, generally, may still be able to perform usual functions.

It is the period between the incubation period and the illness period. During this period, the symptoms are not highly specific and the affected individual may feel discomfort but, generally, may still be able to perform usual functions.

Synonym: prodromal stage. See also: incubation period, illness period, convalescent period

What is prodrome?

In the field of medicine, the term “prodrome” is characterized as a stage in which some early signs and symptoms start to appear before the appearance of any specific diagnostic-related symptoms. These early signs and symptoms indicate the beginning of any disease.

“Prodrome” comes from the Greek word “prodromos”, which means “running before”. Sometimes, in the prodrome phase, the symptoms are non-specific, but sometimes they may relate to a particular disease.

For Example: In many infectious diseases, some symptoms that are non-specific and appear in the prodromal phase are loss of appetite, headache, malaise, and fever. (Kenneth W. Lindsay, 2011)

(Kenneth W. Lindsay, 2011)

What happens in the prodromal phase?

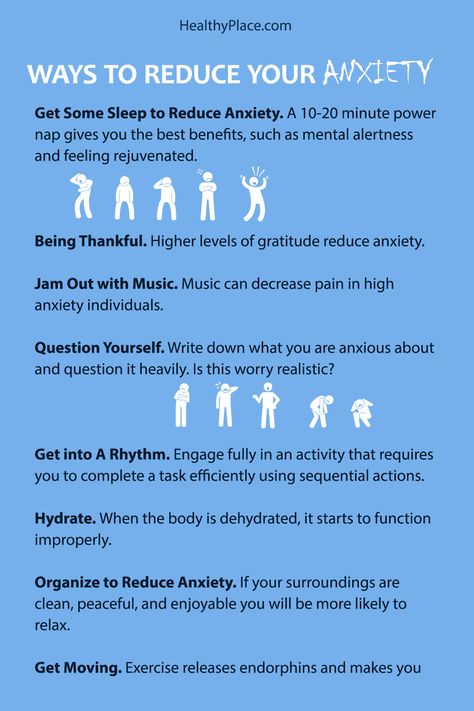

After the incubation period, the prodromal period follows. In this period, the host had some symptoms like inflammation, pain, swelling, soreness, and fever. These general symptoms are due to the activation of the immune system. It is difficult to make a diagnosis based on these general signs and symptoms. The symptoms appear to be more exact and specific in the illness phase, which comes after the prodromal phase (Bhandari, 2020).

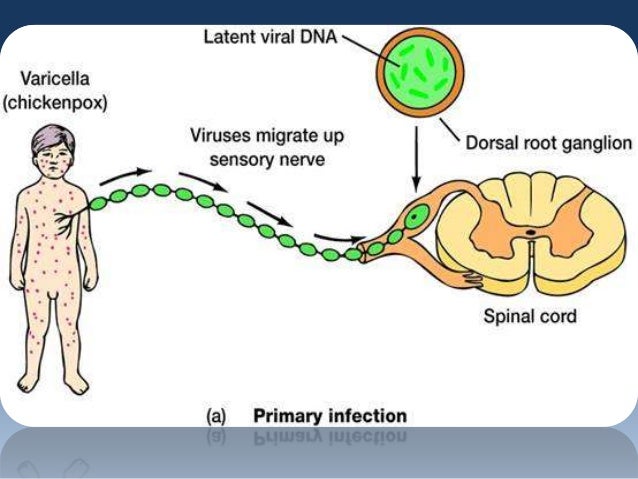

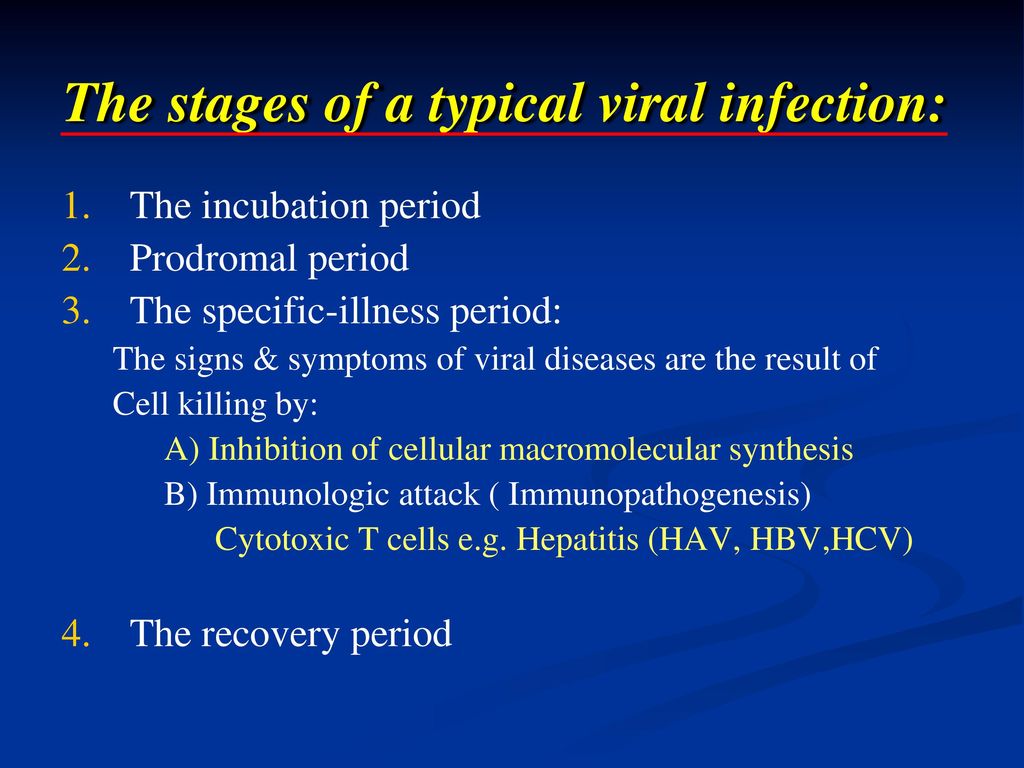

What is the prodromal period of an infectious disease?

In the prodromal period, the pathogens replicate continuously. The immune system of the body gets activated and some general symptoms start appearing. Symptoms are fatigue and low-grade fever. In the prodromal stage, there are higher chances that the host might transfer the infection to others.

It depends on the type of infection and how long the prodromal period lasts. For instance, the incubation period of flu is about 2 days.![]() In this case, the prodromal period might overlap the incubation period and the beginning of the illness. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says that there are higher chances that the pathogen virus transfers to another one day earlier to the appearance of symptoms and up to the week after the illness period (Eske, 2021).

In this case, the prodromal period might overlap the incubation period and the beginning of the illness. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says that there are higher chances that the pathogen virus transfers to another one day earlier to the appearance of symptoms and up to the week after the illness period (Eske, 2021).

Watch this video below to understand the different stages of the disease.

Prodromal Phase of Common Diseases and Conditions

Some of the well-known prodromal symptoms of common diseases are described below.

- Prodromal phase of pneumonia

- Prodromal phase of malaria

- Prodromal phase of influenza

- Prodromal phase of meningitis

- Prodromal phase of schizophrenia

Prodromal phase of pneumonia

The prodromal signs of pneumonia in the patient include coughing (with bloody, green, or yellow mucus). The patient also had a lack of appetite, stabbing pain in the chest, shallow breathing, shortness of breath, low energy, chills, and fever.

The patient also had a lack of appetite, stabbing pain in the chest, shallow breathing, shortness of breath, low energy, chills, and fever.

- In bacterial pneumonia, the patient may have a high-grade fever. Due to insufficient oxygen in the blood, the patients may have blue nail beds.

- Viral pneumonia takes some days to develop but shows symptoms similar to influenza. The symptoms are dry cough, weakness, fever, muscular pain, and headache. A patient should get proper medical treatment if the symptoms (blue lips, fever) get worse in a few days.

Prodromal phase of malaria

In the prodromal phase of malaria, the symptoms are fever (remains for up to two days), lack of appetite, pain in the body, headache, and fatigue. If the patient has weak immunity, malaria starts with a sudden and extreme feeling of sickness. The fever may be at 39°C and higher. The fever does not follow a regular pattern. Some other symptoms include respiratory distress, confusion, vomiting, nausea, icterus, and dry cough.

The fever may be at 39°C and higher. The fever does not follow a regular pattern. Some other symptoms include respiratory distress, confusion, vomiting, nausea, icterus, and dry cough.

Prodromal phase of influenza

The most common source of morbidity and mortality is influenza. Influenza is a worldwide occurring viral infection. This viral disease mainly spreads in two ways.

- Direct contact with the nasal secretion of patient

- Inhaling the coughed and sneezed droplets of the patients

The symptoms of the prodromal phase of infection include a runny and stuffy nose, sore throat, rigors, myalgia, malaise, and fever.

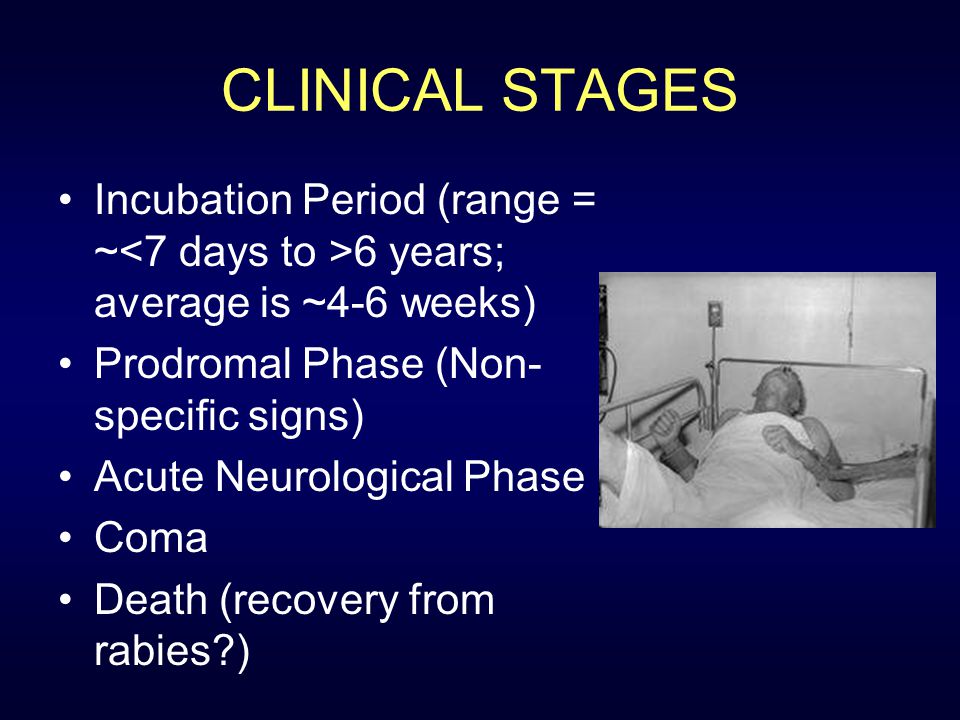

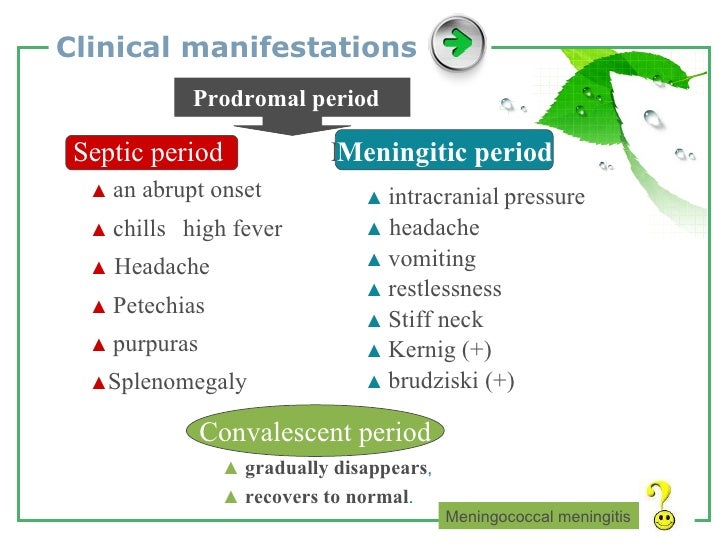

Prodromal phase of meningitis

The infection of protective membranes (meninges) that surrounds the brain and spinal cord is known as meningitis. It affects any person but most commonly it affects babies, teenagers, young children, and young adults. It proves a very serious condition if not treated timely. Some non-specific symptoms appear in the prodromal stage that may last throughout the illness. The symptoms are loss of appetite, respiratory disorder, headache, joint and muscular pain, irritability, lethargy, vomiting, nausea, and fever.

It affects any person but most commonly it affects babies, teenagers, young children, and young adults. It proves a very serious condition if not treated timely. Some non-specific symptoms appear in the prodromal stage that may last throughout the illness. The symptoms are loss of appetite, respiratory disorder, headache, joint and muscular pain, irritability, lethargy, vomiting, nausea, and fever.

Some specific symptoms in the case of bacterial meningitis are seizures, stiffness in the neck, photophobia, headache, confusion, drowsiness, and focal neuro deficit.

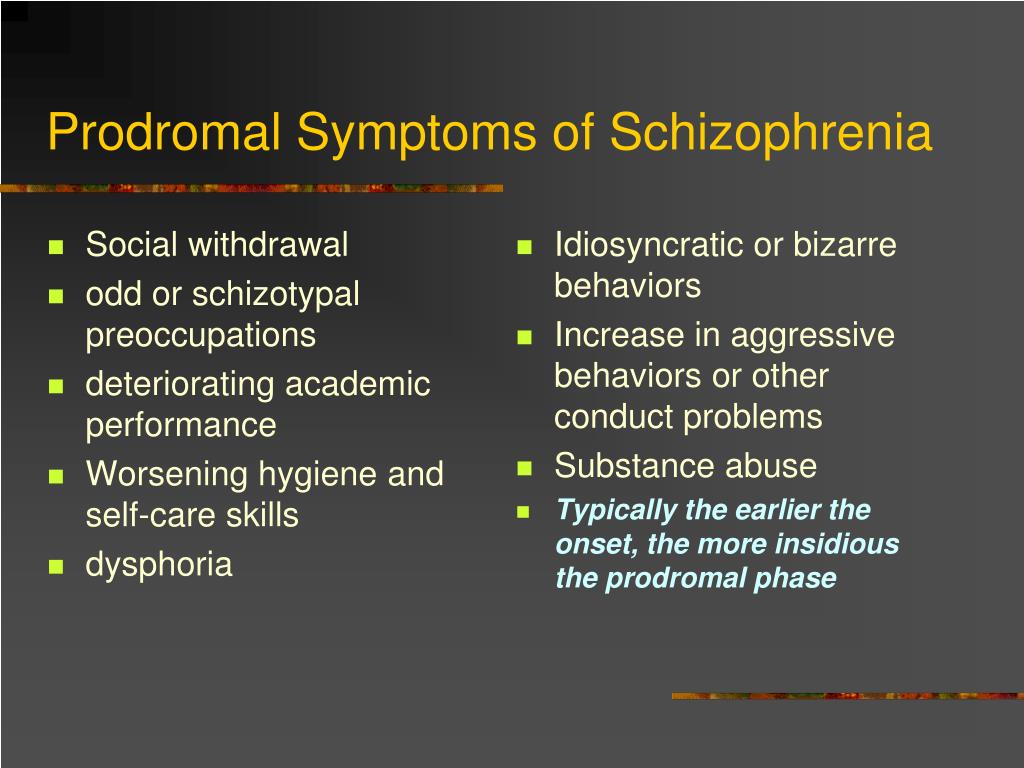

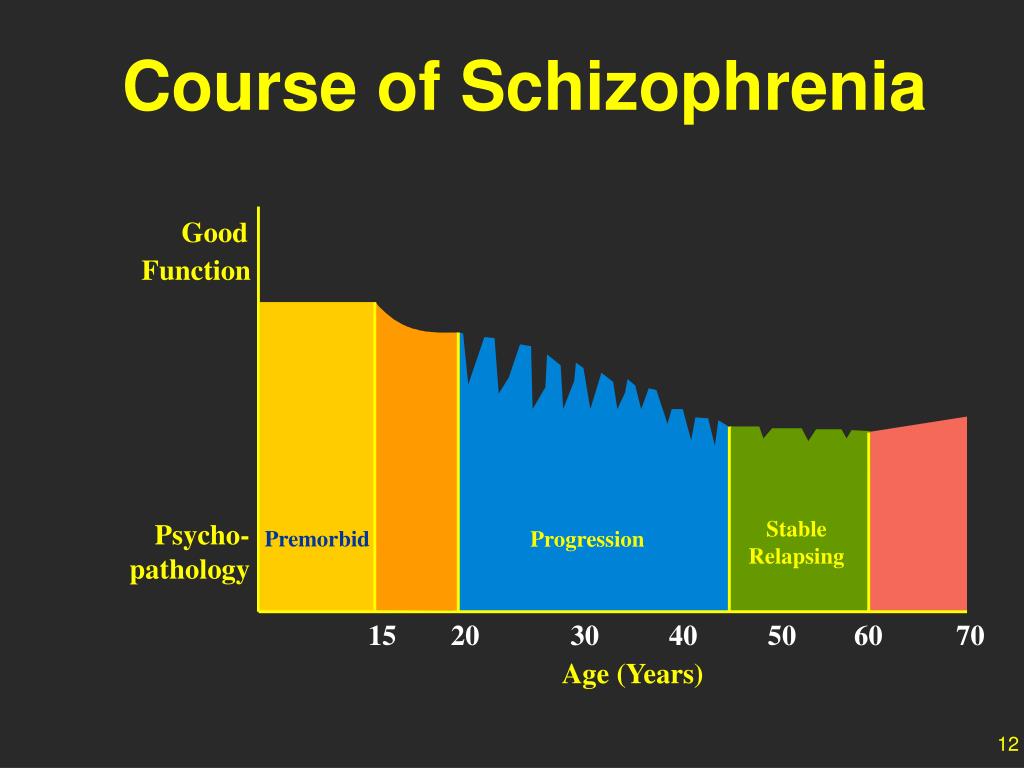

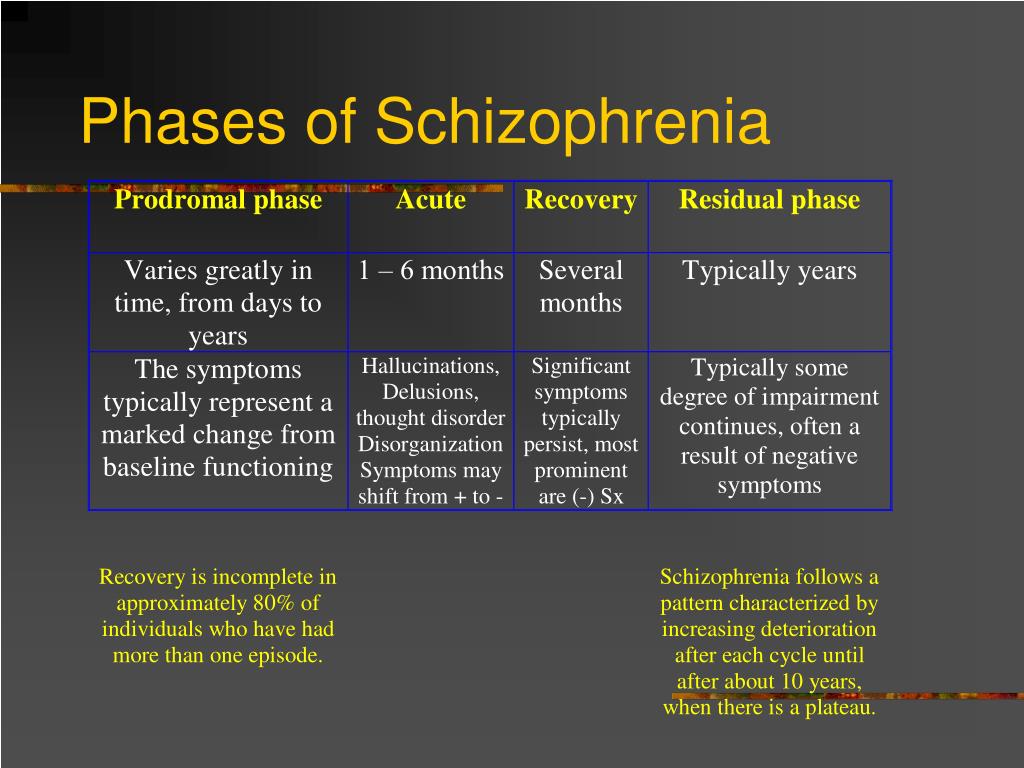

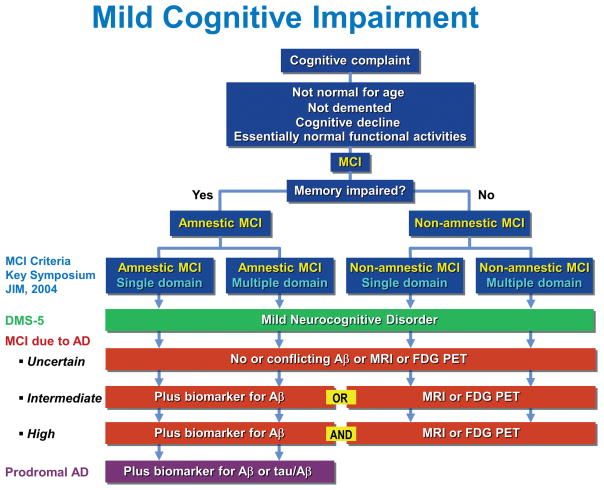

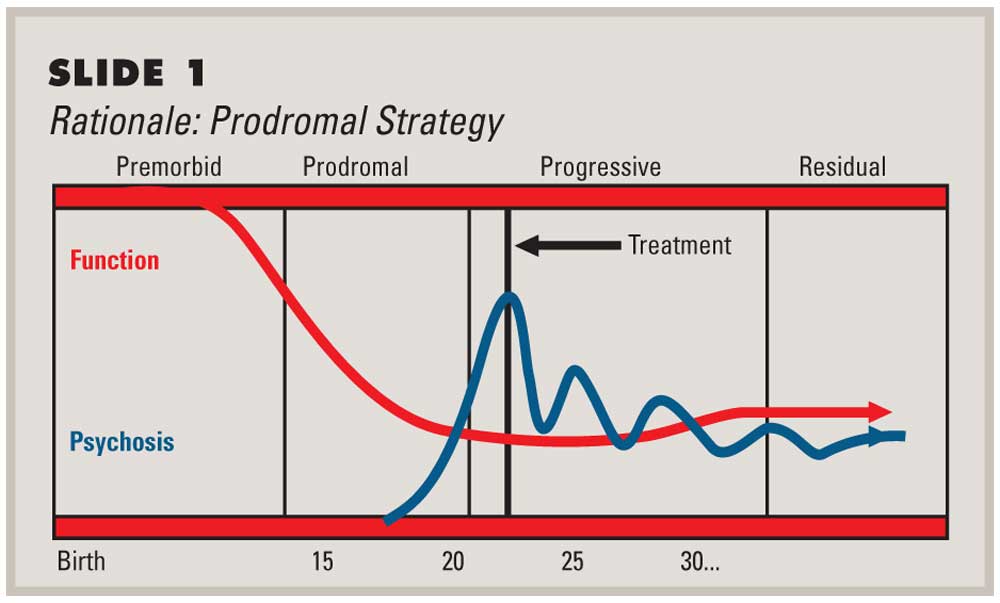

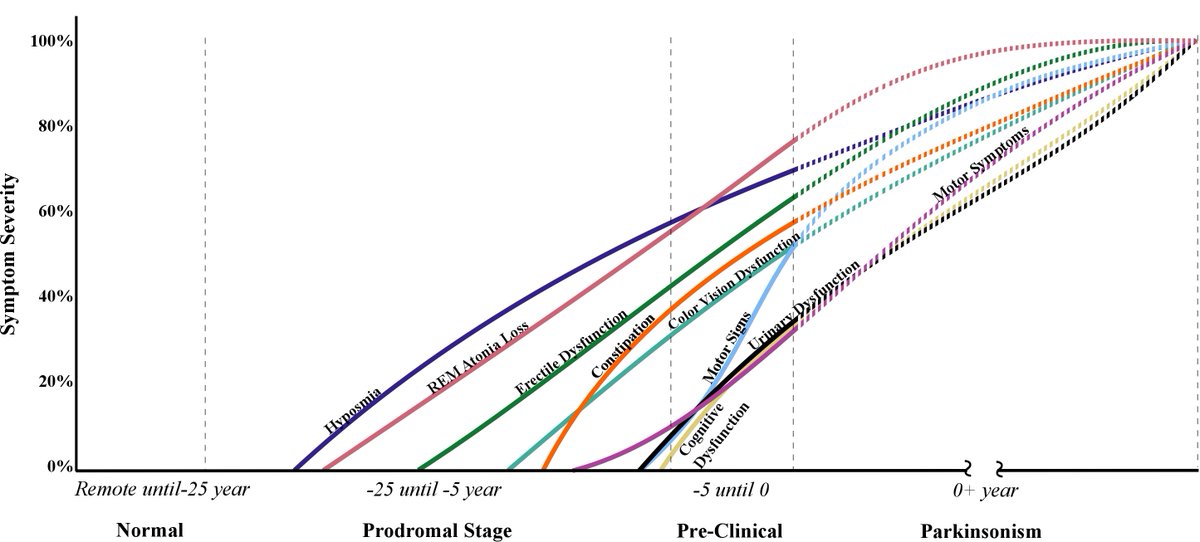

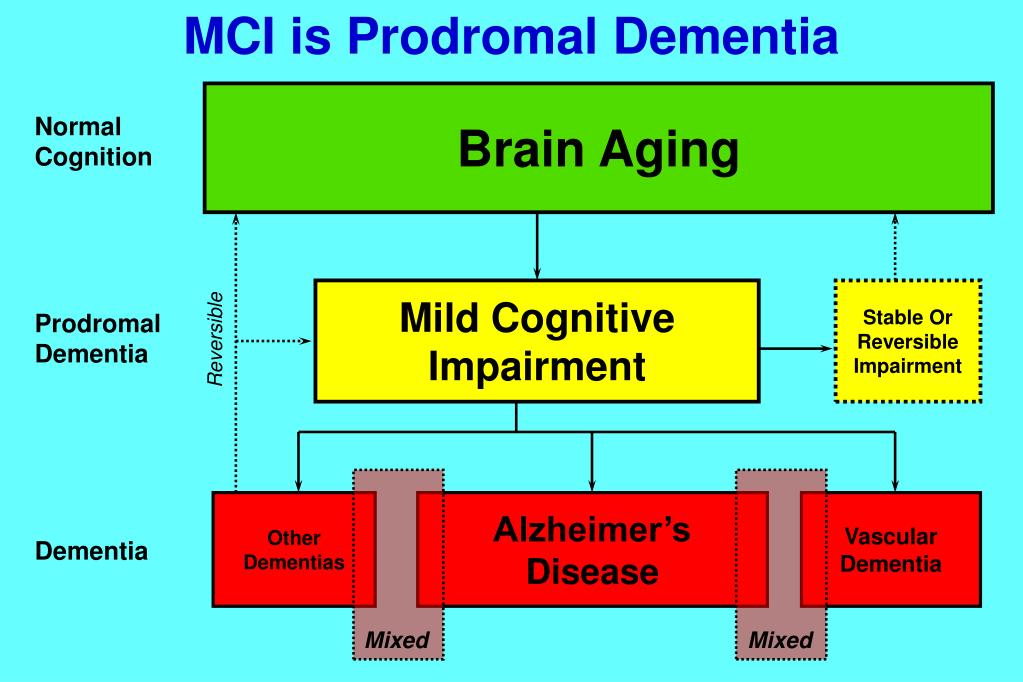

Prodromal Schizophrenia

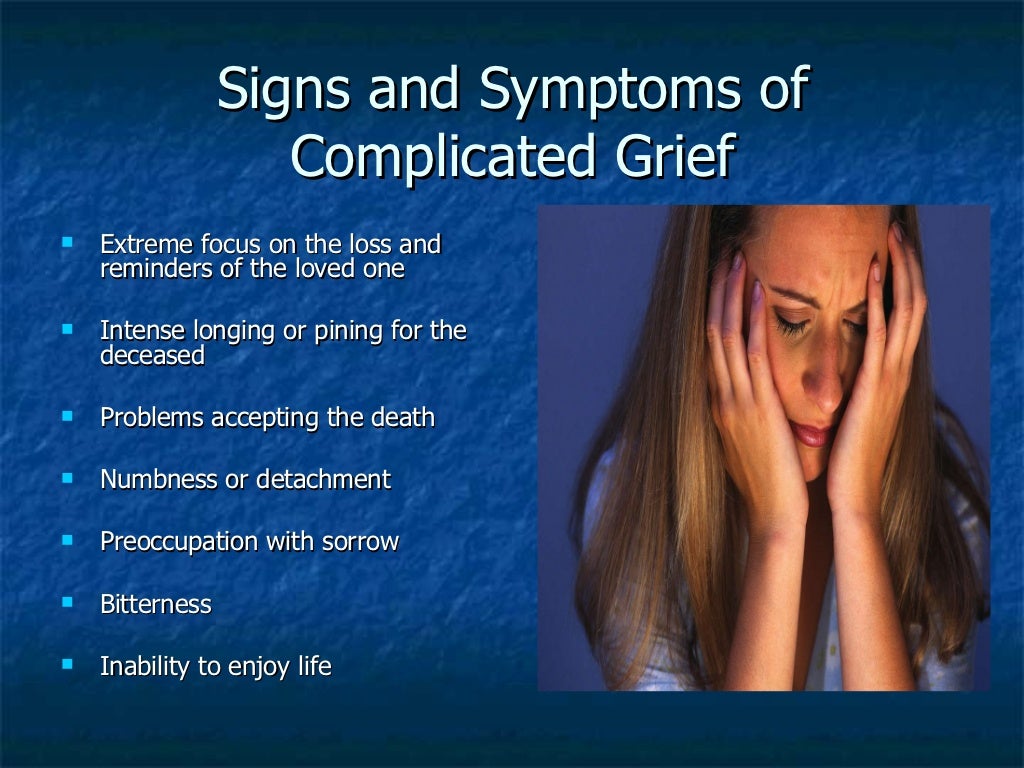

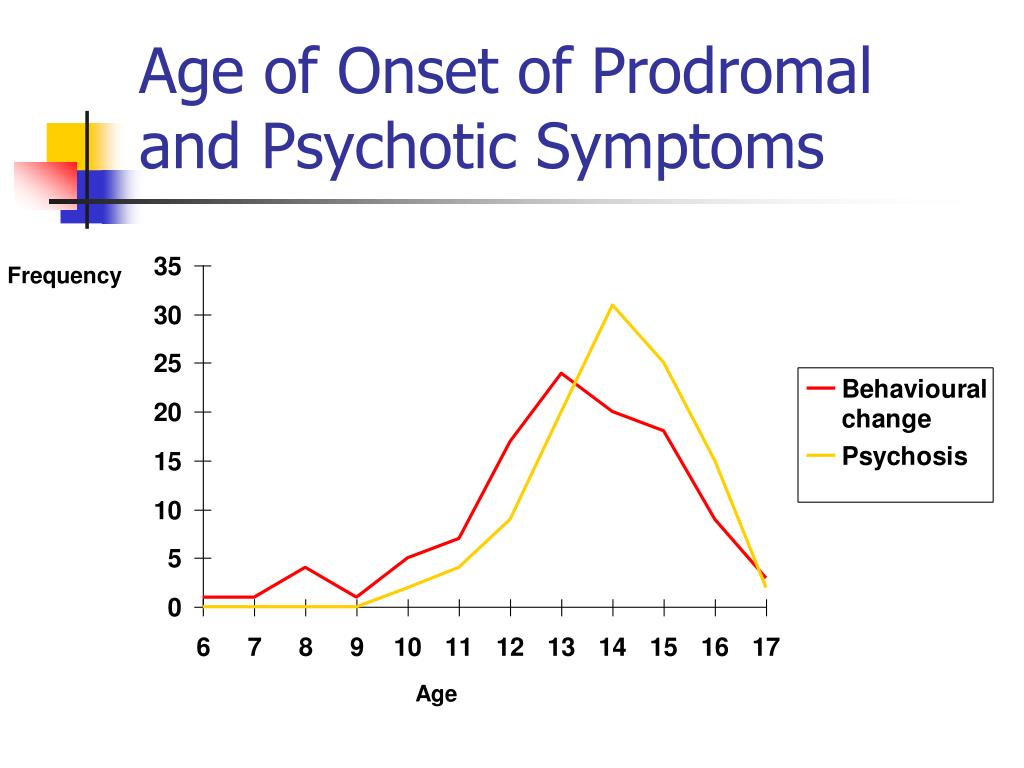

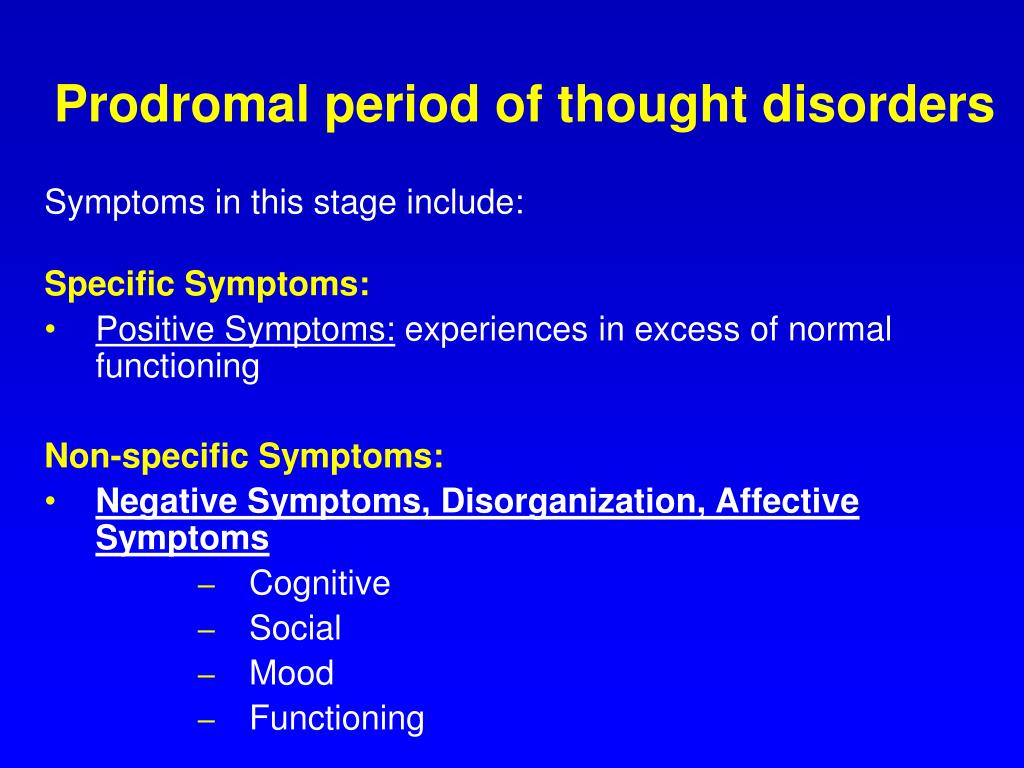

Schizophrenia is defined as a chronic illness of the nervous system. It affects the way a person behaves, thinks, or feels. The thought of investigating the prodromal of schizophrenia is almost 100 years back but now it is recently accepted. There is an unusual behavioral alteration in this disease. The prodromal period of schizophrenia usually remains for several years. It causes many social consequences on the person. In the prodromal period, there are several cognitive and behavioral modifications in a person. Such modification continues to progress with time and leads to psychosis. Some symptoms of the prodromal period of schizophrenia are the problem in sleeping, anxiety, irritability, changes in daily routine, difficulty in concentration, neglecting personal hygiene, lack of motivation, erratic behavior, and social isolation (Subotnik, 1988).

The prodromal period of schizophrenia usually remains for several years. It causes many social consequences on the person. In the prodromal period, there are several cognitive and behavioral modifications in a person. Such modification continues to progress with time and leads to psychosis. Some symptoms of the prodromal period of schizophrenia are the problem in sleeping, anxiety, irritability, changes in daily routine, difficulty in concentration, neglecting personal hygiene, lack of motivation, erratic behavior, and social isolation (Subotnik, 1988).

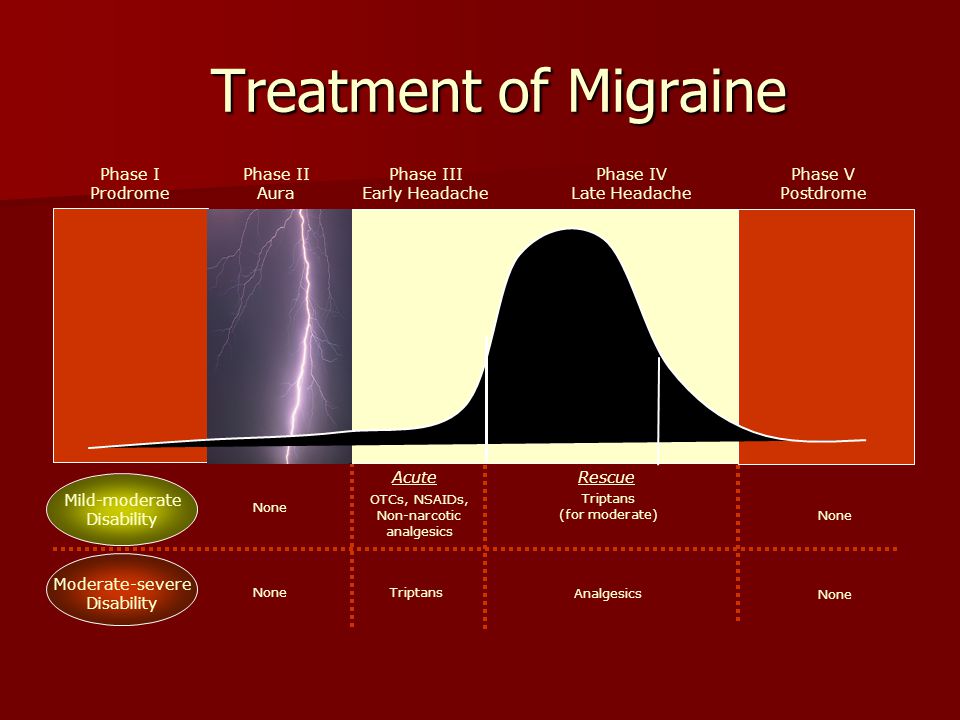

Prodromal phase of schizophrenia

The prodromal phase of schizophrenia usually starts in the 20s or in the teenage years. Due to this, it is difficult that either the alteration in the behavior is due to schizophrenia or because of young adult behavior. Research for the treatment of schizophrenia includes those patients which are in their phase. Some researchers suggest that using some strategies and modifying them according to the need of the patient, may prove helpful for the patient in coping and give better results.

Try to answer the quiz below to check what you have learned so far about prodromal period.

Quiz

Choose the best answer.

1. Early signs and symptoms but not yet clinically specific

Incubation period

Prodromal period

Illness period

2. Specific symptoms appear

Incubation period

Prodromal period

Illness period

3. An agent of disease

Vector

Pathogen

Host

4. A general symptom characterized by high body temperature

Malaise

Fever

Rashes

5. Which of the following is a symptom during a prodromal phase of meningitis?

Photophobia

Focal neuro deficit

Nausea

Send Your Results (Optional)

Your Name

To Email

Next

FGBNU NTsPZ.

‹‹Endogenous organic mental illness ››

‹‹Endogenous organic mental illness ›› Feedback form

Question about the work of the siteQuestion to a specialistQuestion to the administration of the clinic

email address

Name

Message text

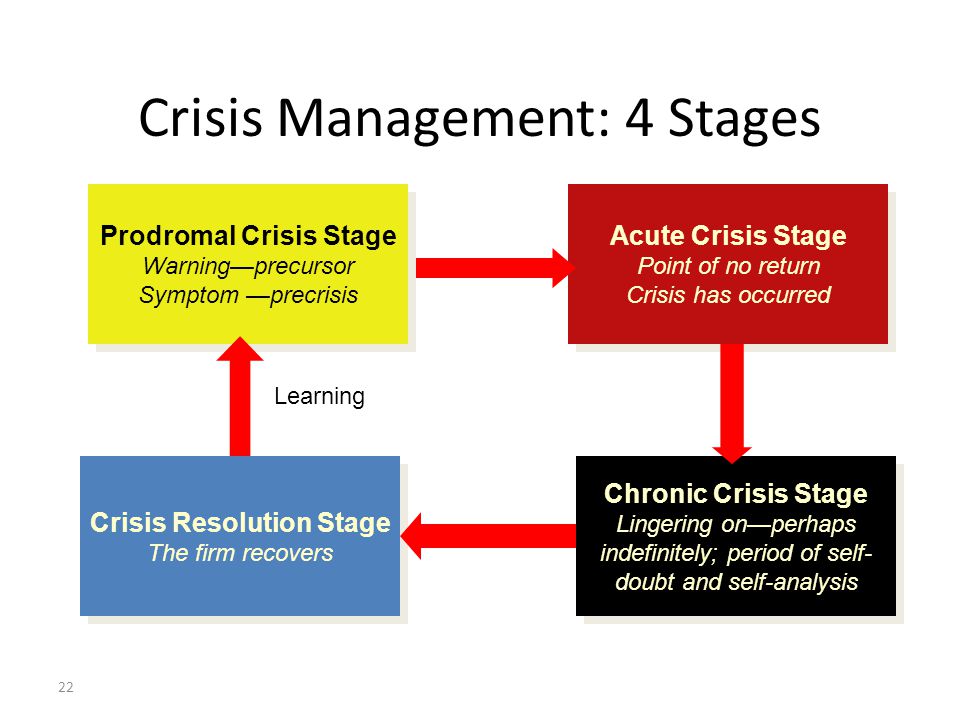

The clinical picture of epileptic disease is polymorphic. It consists of prodromal disorders, various convulsive and non-convulsive paroxysms, personality changes and psychoses (acute and chronic). nine0005

In epileptic disease, the prodromal period of the disease and the prodrome of the paroxysmal state are distinguished.

The prodromal period of the disease includes various disorders that precede the first paroxysmal state, i.e., the manifestation of the disease in the most typical manifestation.

Usually, several years before the first paroxysmal attack, episodic attacks of dizziness, headaches, nausea, dysphoric conditions, sleep disturbances, and asthenic disorders are observed. In some patients, there are rare absences, as well as a pronounced readiness for convulsive reactions to the effects of various exogenous hazards [Vorobiev S. P., 1965]. In some cases, symptoms more specific to epilepsy are also detected - the predominance of polymorphic variable non-convulsive paroxysmal conditions that have a number of features [Boldyrev A.I., 1971]. Most often, these are short-term myoclonic twitches of individual muscles or muscle groups, hardly noticeable to others, often without changes in consciousness and timed to a certain time of day. These conditions are often combined with short-term sensations of heaviness in the head, headaches of a certain localization, paresthesias, as well as vegetative and ideational non-convulsive paroxysms. Vegetative paroxysms are manifested by sudden breathing difficulties, a change in the rhythm of breathing, heart attacks, etc. Ideatory paroxysms most often have the character of violent thoughts, acceleration or deceleration of thinking. As the disease progresses, the manifestations described in the prodromal period become more pronounced and frequent. nine0005

P., 1965]. In some cases, symptoms more specific to epilepsy are also detected - the predominance of polymorphic variable non-convulsive paroxysmal conditions that have a number of features [Boldyrev A.I., 1971]. Most often, these are short-term myoclonic twitches of individual muscles or muscle groups, hardly noticeable to others, often without changes in consciousness and timed to a certain time of day. These conditions are often combined with short-term sensations of heaviness in the head, headaches of a certain localization, paresthesias, as well as vegetative and ideational non-convulsive paroxysms. Vegetative paroxysms are manifested by sudden breathing difficulties, a change in the rhythm of breathing, heart attacks, etc. Ideatory paroxysms most often have the character of violent thoughts, acceleration or deceleration of thinking. As the disease progresses, the manifestations described in the prodromal period become more pronounced and frequent. nine0005

Prodromes of paroxysms immediately precede the development of an epileptic seizure. According to most researchers, they occur in 10% of cases (in the remaining patients, seizures develop without obvious precursors). The clinical picture of the seizure prodrome is nonspecific, with a wide range of symptoms. In some patients, the duration of the prodrome is several minutes or several hours, in others it is equal to a day or more. Typically, the prodrome includes asthenic disorders with symptoms of irritable weakness and persistent headache, different in nature, intensity and localization. nine0005

According to most researchers, they occur in 10% of cases (in the remaining patients, seizures develop without obvious precursors). The clinical picture of the seizure prodrome is nonspecific, with a wide range of symptoms. In some patients, the duration of the prodrome is several minutes or several hours, in others it is equal to a day or more. Typically, the prodrome includes asthenic disorders with symptoms of irritable weakness and persistent headache, different in nature, intensity and localization. nine0005

Paroxysm may be preceded by paroxysmal affective disorders: periods of mild or more pronounced depression with a hint of displeasure, irritability; hypomanic states or pronounced mania. Often in the prodrome, patients experience melancholy, a feeling of impending and inevitable disaster, do not find a place for themselves. Sometimes these states are less pronounced and are limited to a feeling of discomfort: patients complain of slight anxiety, heaviness in the heart, a feeling that something unpleasant should happen to them. The prodrome of paroxysms may include senestopathic or hypochondriacal disorders. Senestopathic phenomena are expressed in vague and varied sensations in the head, various parts of the body and internal organs. Hypochondriacal disorders are characterized by excessive suspiciousness of patients, increased attention to unpleasant sensations in the body, their well-being and body functions. Patients prone to self-observation, according to prodromal phenomena, determine the approach of paroxysm. Many of them take precautions: stay in bed, at home, try to be in the circle of their loved ones so that the attack passes in more or less favorable conditions. nine0005

The prodrome of paroxysms may include senestopathic or hypochondriacal disorders. Senestopathic phenomena are expressed in vague and varied sensations in the head, various parts of the body and internal organs. Hypochondriacal disorders are characterized by excessive suspiciousness of patients, increased attention to unpleasant sensations in the body, their well-being and body functions. Patients prone to self-observation, according to prodromal phenomena, determine the approach of paroxysm. Many of them take precautions: stay in bed, at home, try to be in the circle of their loved ones so that the attack passes in more or less favorable conditions. nine0005

PRODROMAL - What is PRODROMAL?

The word consists of 13 letters: first p, second p, the third o fourth d, fifth p, the sixth o seventh m, eighth a, ninth l, tenth b, eleventh n, twelfth s, last th, nine0005

The word prodromal in English letters (transliteration) - prodromalnyi

- The letter p occurs 1 time.

Words with 1 letter p

Words with 1 letter p - The letter p occurs 2 times. Words with 2 letters p

- The letter o occurs 2 times. Words with 2 letters o

- The letter d occurs 1 time. Words with 1 letter d

- The letter m occurs 1 time. Words with 1 letter m

- The letter a occurs 1 time. Words with 1 letter a

- The letter l occurs 1 time. Words with 1 letter l

- The letter ь occurs 1 time. Words with 1 letter ь

- The letter н occurs 1 time. Words with 1 letter н

- The letter ы occurs 1 time. Words with 1 letter ы

- The letter and occurs 1 time. Words with 1 letter y

Prodrome

Prodromal period (Greek πρόδρομος - running ahead, harbinger) - the period of the disease that occurs between the incubation period and the disease itself. nine0005 en.wikipedia.

org

Prodromal period (from the Greek. prodromes - running ahead, harbinger), the period of disease precursors. In P. p. of infections, nonspecific ones are noted (weakness, headache, slight fever) ...

TSB. — 1969—1978

PRODROMAL PERIOD (from the Greek. prodromos - a harbinger) - the stage of the precursors of the disease - the appearance of its nonspecific signs (eg, malaise, fever, loss of appetite, gastralgia, etc. in the preicteric period of Botkin's disease). nine0005 Big Encyclopedic Dictionary

Prodromal period The prodromal period is the period of the disease following the incubation period and passing into the peak period. P.p. duration ranges from a few hours to many weeks.

Dictionary of Microbiology

Prodromal period - (Greek prodromos - running ahead) - the earliest stage of the disease, in which the disease is latent, asymptomatic or with occasional and short-term individual symptoms.

nine0005 Zhmurov V.A. Large explanatory dictionary of terms in psychiatry

Prodromal I (Prodromal)

PRODROMAL I (prodromal) - relating to the period preceding the onset of the first symptoms of any infectious disease (for example, a rash or fever).

vocabulary.ru

Prodromal I (Prodromal) - relating to the period preceding the onset of the first symptoms of any infectious disease (for example, rash or fever). nine0005 Medical terms from A to Z

Prodromal I (Prodromal) referring to the period preceding the onset of the first symptoms of any infectious disease (eg, rash or fever).

Medical terms. - 2000

Prodromal II (Subclinical)

PRODROMAL II (subclinical) - this term is used to describe the period preceding the detection of obvious symptoms of the disease.

nine0005 vocabulary.ru

Prodromal II (Subclinical) - this term is used to describe the period preceding the detection of obvious symptoms of the disease.

Medical terms from A to Z

Prodromal II (Subclinical) This term is used to describe the period prior to the discovery of overt symptoms of the disease. Source: Medical Dictionary

Medical terms. - 2000

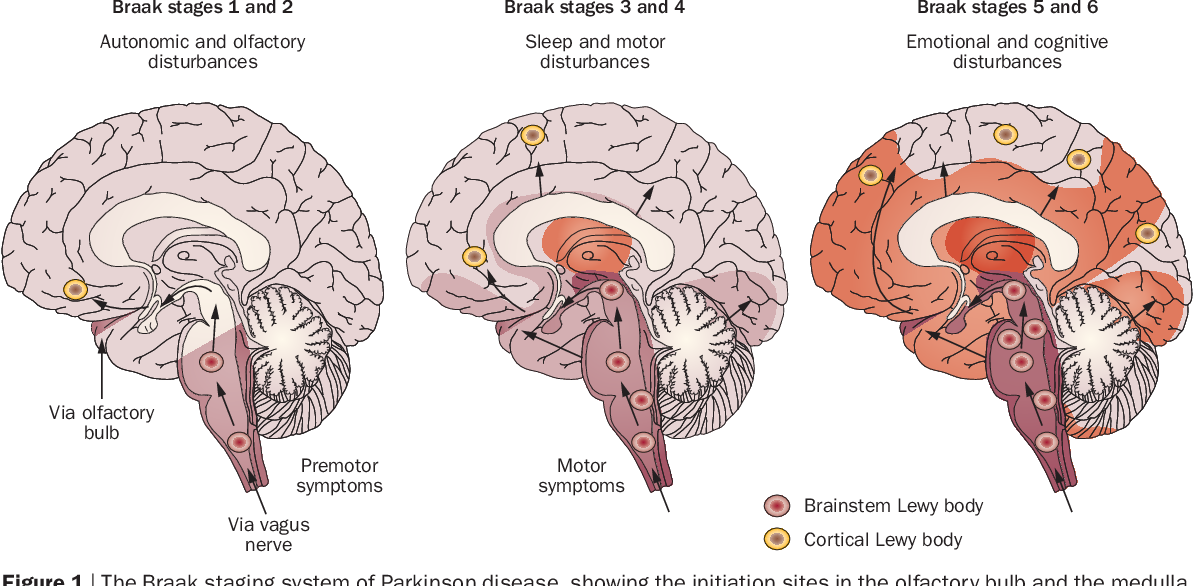

Schizophrenia prodromal period

Schizophrenia prodromal period - a period of time preceding the onset of an acute psychotic state for a number of weeks, months, but more often years, during which mild cognitive impairment is detected in patients ...

vocabulary.ru

Russian

Prodromal.