What is social exchange

What Is Social Exchange Theory?

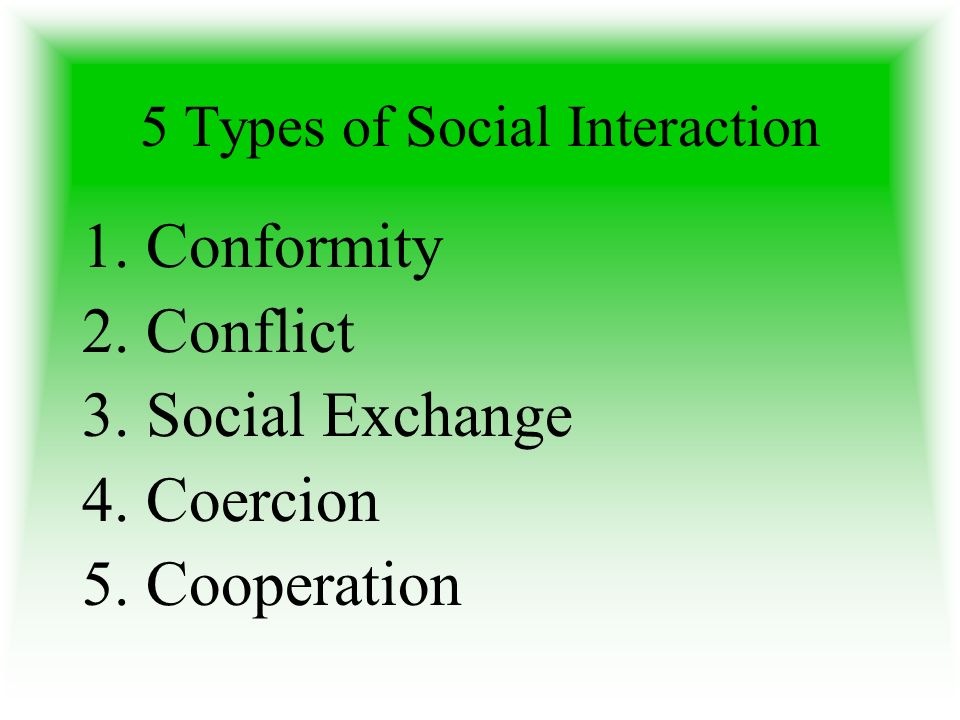

We’re taught to weigh pros and cons. In some cases, the words “pro” and “con” may be swapped out for “risk” and “reward.” While this practice typically contributes to whether one pursues something material, the sociological concept known as social exchange theory applies the same principles to person-to-person interaction in order to better understand relationship dynamics. But how exactly does this theory work?

History and Definition of the Theory

The genesis of social exchange theory goes back to 1958, when American sociologist George Homans published an article entitled “Social Behavior as Exchange.” Homans devised a framework built on a combination of behaviorism and basic economics. In the immediate years that followed, other studies expanded the parameters of Homans’ fundamental concepts.

Social exchange theory is a concept based on the notion that a relationship between two people is created through a process of cost-benefit analysis. In other words, it’s a metric designed to determine the effort poured in by an individual in a person-to-person relationship. The measurement of the pluses and minuses of a relationship may produce data that can determine if someone is putting too much effort into a relationship.

The theory is unique in the sense that it doesn’t necessarily measure relationships on emotional metrics. Rather, its systematic processes rely on mathematics and logic to determine balance within a relationship. While the theory can be used to measure romantic relationships, it can also be applied to determine the balance within a friendship.

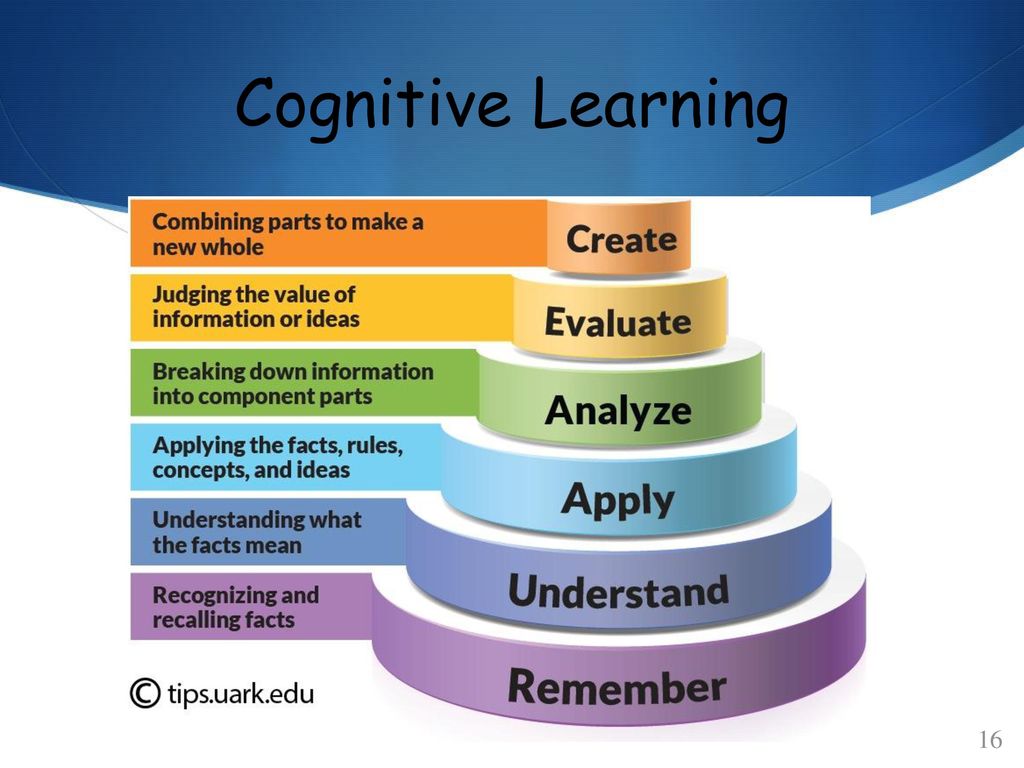

The foundation of social exchange theory rests on several core assumptions regarding human nature and the nature of relationships. The first assumption is that humans tend to seek out rewards and avoid punishments. Another tenet is the assumption that a person begins an interaction to gain maximum profit with minimal cost — the individual is driven by “what’s in it for me?” A third assumption is that individuals tend to calculate the profit and cost before engaging. Finally, the theory assumes that people know that this “payoff” will vary from person to person, as well as with the same person over time.

Finally, the theory assumes that people know that this “payoff” will vary from person to person, as well as with the same person over time.

How This Theory Works

The theory’s core assumptions establish a fundamental foundation within social exchange theory — one size does not fit all. A person’s expectations, as set by comparison levels, allow the theory to be viewed on a sliding scale, one that adjusts on an individual basis. If an individual’s personal relationship samples are set on a certain level, he or she will tend to use this level as a baseline for future relationships.

For example, if a person enters a new relationship after a succession of poor friendships or disastrous romantic relationships, that person’s expectations at the start of a new relationship are going to be lower than those of a person who has a tight group of friends. Conversely, if a person’s ex-girlfriend provided him with a ton of gifts and affections, he may enter into his next relationship expecting similar behaviors.

These levels of expectation can often work in conjunction with another core concept of the theory’s functionality: costs vs. benefits. This is perhaps the theory’s most known commodity, as it establishes a “give and take” metric that can be analyzed to determine how much effort one party may be putting into the relationship.

The “costs” in this theory component are things that a person may see as a negative in a relationship. A friend who constantly borrows money or a partner who consistently doesn’t do his expected chores in the house may rack up a lot of cost. “Benefits,” as they pertain to this theory, are traits that an individual may see as positive attributes. The friend who’s always willing to lend an ear in times of trouble or constantly extends an invitation for a Sunday afternoon beer may offer plenty of benefits.

According to the theory, a worthwhile relationship will be as far away from the cost category as possible. Even if there are a few costs involved in the relationship — and human behavior dictates there probably will be — if enough positive traits outweigh the negative traits, then the costs hold no value.

If the costs far outweigh the benefits, it may be an indicator that it’s time to move on; however, the theory’s aspect of evaluating alternatives prevents this decision from being automatic. Alternative evaluation involves analyzing possible replacements for an existing relationship, a process that weighs costs and benefits against a person’s comparison levels. This analysis may drive a person to the conclusion that the relationship he or she is currently in is still better than anything else that’s out there, a decision that may also cause a person to reassess the cost vs. benefit value of an existing relationship.

Putting the Theory Into Practice

From a sociological standpoint, applying the metrics that collectively build social exchange theory can be a great tool to analyze relationships and human behavior. The dynamics that go into making this theory work can be useful for sociologists to develop their own theories and concepts regarding the ways in which humans behave with each other. Make use of the social exchange theory through a career in social work by earning a Master’s Degree in Social Work.

Make use of the social exchange theory through a career in social work by earning a Master’s Degree in Social Work.

5 Specializations in Social Work Careers

How Social Workers Make a Difference

A Day in the Life of a Licensed Clinical Social Worker (LCSW)

What is Social Exchange Theory?

Social work is a challenging yet rewarding profession. Social workers typically have clients across all demographics who have a wide range of needs. They identify those needs by analyzing the client’s behavior and the social systems affecting the client’s opportunities and decisions. Using a comprehensive approach, social workers can help clients live healthier, safer and happier lives.

Social workers are often a type of mental health practitioner. They act as counselors in addition to helping clients navigate legal and social support systems. Because of this, they need to understand different theories regarding human behavior and interaction.

One is rational choice theory, which believes people make decisions based on their preferences. A related theory is social exchange theory, which looks at all human interactions as an exchange of value where someone benefits and someone pays a price. Understanding how someone views rewards vs. costs, as well as their expectations and preferences for relationships, can help social workers improve a client’s personal relationships and outlook on life.

A related theory is social exchange theory, which looks at all human interactions as an exchange of value where someone benefits and someone pays a price. Understanding how someone views rewards vs. costs, as well as their expectations and preferences for relationships, can help social workers improve a client’s personal relationships and outlook on life.

The basic definition of social exchange theory is that people make decisions by consciously or unconsciously measuring the costs and rewards of a relationship or action, ultimately seeking to maximize their reward. This theory focuses on face-to-face relationships and isn’t meant to measure behavior or change at a societal level.

According to social exchange theory, a person will weigh the cost of a social interaction (negative outcome) against the reward of that social interaction (positive outcome). These costs and rewards can be material, like money, time or a service. They can also be intangible, like effort, social approval, love, pride, shame, respect, opportunity and power.

Each person wants to get more from an interaction or relationship than they give. When a relationship costs a person more than it rewards them, they end it. But when a relationship provides enough rewards, they continue it. What is or isn’t enough depends on various factors, including a person’s expectations and comparisons with other possible interactions and relationships.

Another aspect of social exchange theory is that people expect equity in exchange. People expect to be rewarded equally for incurring the same costs, and when they aren’t, they are displeased.

Social exchange theory was developed by George Homans, a sociologist. It first appeared in his essay “Social Behavior as Exchange,” in 1958. Homans studied small groups, and he initially believed that any society, community or group was best seen as a social system. To study that social system, it was first necessary to look at an individual’s behavior, instead of the social structures individuals created.

It was by studying small groups that Homans began to see the rewards and punishments each member of the group got from the group and other members. He developed a framework of elements of social behavior: interaction, sentiments and activities. These elements all had to be considered regarding a groups’ internal and external systems. He used this framework to study several groups—a study he published in “The Human Group,” his first book.

He developed a framework of elements of social behavior: interaction, sentiments and activities. These elements all had to be considered regarding a groups’ internal and external systems. He used this framework to study several groups—a study he published in “The Human Group,” his first book.

Later, Homans began to explain further the most basic level of social situations, called elementary social behavior, which is at least two people interacting, with one either rewarding or punishing the actions of the other. This idea reflects Homans adopting B.F. Skinner’s behavioral psychology theories about human behavior as well as basic principles of economics.

Homans suggested several propositions that theorize social behavior as an exchange of material and non-material goods, like time, money, effort, approval, prestige, power, etc. Every person provides rewards and endures costs. People expect to receive as much reward as they give to another and will choose actions that are likely to provide the greatest reward.

Homans is not the only person to develop social exchange theory. Many sociologists and other professionals have advanced social exchange theory. Peter Michael Blau didn’t focus on behaviorism, and instead, focused his theory on concepts such as preferences, interests, indifference curves and supply and demand. More modern takes on social exchange theory borrow from both men and particularly focus on power dynamics. Because of this variety, social exchange theory is not one solidified theory. Instead, different theorists use various concepts and assumptions for their particular application.

Several assumptions make up social exchange theory:

Social exchange theory can be applied to many situations, including:

Social workers can use the theory of social exchange to help their clients repeat positive interactions and behaviors. First, social workers must understand that every person is looking for rewards within a relationship. Clients want more positive outcomes from their relationship with the social worker than negative outcomes. They want the rewards they receive to be greater than the cost. Social workers can create interactions in which the clients receive some benefit. When a person receives rewards for certain actions, they tend to repeat them. But when a person receives the same reward over and over, it becomes less effective. Social workers must keep this in mind and vary their interactions with their clients.

They want the rewards they receive to be greater than the cost. Social workers can create interactions in which the clients receive some benefit. When a person receives rewards for certain actions, they tend to repeat them. But when a person receives the same reward over and over, it becomes less effective. Social workers must keep this in mind and vary their interactions with their clients.

Many social workers strive to help their clients improve their personal relationships, whether those are between spouses, parents and children, other relatives, friends or coworkers. Social workers can discuss with their clients how they choose to interact with others and why. The workers can help clients take a closer look at their behavior, including why they pursue or end relationships.

In social exchange theory, people tend to make comparisons, often unconsciously. They compare their relationship to their expectations, previous similar relationships, and alternative relationships. The point of comparison is to help a person decide when they’re receiving enough of a net benefit. But if someone doesn’t have healthy relationships to compare to, they might continue to pursue unhealthy or unsafe relationships. Social workers can help clients navigate their expectations and comparisons in search of safe, healthy and happy relationships.

But if someone doesn’t have healthy relationships to compare to, they might continue to pursue unhealthy or unsafe relationships. Social workers can help clients navigate their expectations and comparisons in search of safe, healthy and happy relationships.

Social workers also can use social exchange theory to understand their interactions with their clients. By identifying the intrinsic rewards that they receive from helping their clients, workers gain motivation to continue their work.

There are several limitations or weaknesses associated with social exchange theory. The theory can seem overly simplistic. What people get out of relationships vs. what the relationships cost them can be complex. While the theory can help someone take a broad look at a relationship, there are many more factors to consider in terms of whether they should continue or end the relationship.

It doesn’t address selflessness or altruism. There are times when people will act in a way that benefits another at great cost to themselves without expectations of a future benefit in return. The theory doesn’t account for people who don’t seek out the greatest benefit in a relationship or who continue relationships in which there is a net cost to themselves instead of a net reward.

The theory doesn’t account for people who don’t seek out the greatest benefit in a relationship or who continue relationships in which there is a net cost to themselves instead of a net reward.

Social exchange theory believes people behave in a certain way to establish trust and intimacy. This assumption is most related to romantic relationships. But not every relationship has these goals. When two people aren’t concerned with establishing trust and intimacy, then it calls into question how they measure the benefits and costs to themselves or their motivations for the interaction.

Additionally, social exchange theory assumes relationships have a linear structure. In reality, relationships progress, retreat, skip stages, or repeat certain stages.

Future social workers learn about different theories and practice methods while obtaining a Bachelor’s Degree in Social Work (BSW) and a Master of Social Work (MSW). Their programs might include learning more about the strengths and weaknesses of social exchange theories and other rational choice theories. Understanding these theories can help social workers understand their client’s past and current relationships, as well as their own relationships with their clients.

Understanding these theories can help social workers understand their client’s past and current relationships, as well as their own relationships with their clients.

Are you interested in a career in social work? You may want to consider an online degree in social work.

Last updated: February 2022

Theory of social exchange

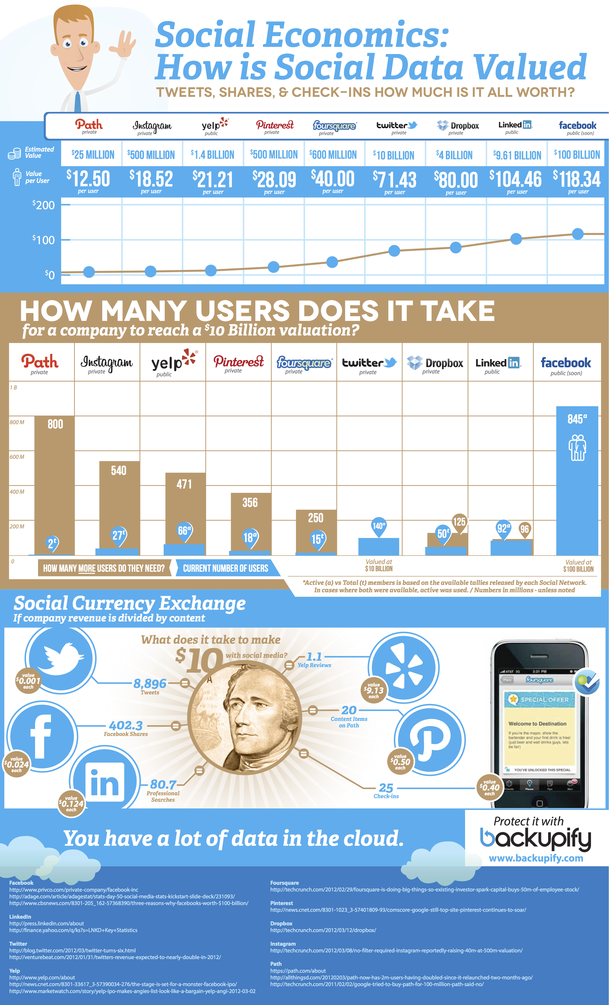

The theory of social exchange spread mainly in the West.

This theory focused on the motives that determine the interaction of people in the aspect of economic relations related to the exchange of goods.

Theorists of the concept of social exchange considered material and spiritual values as the subject of exchange. It is the exchange of these values in all spheres of society, in their opinion, that forms society.

The study of the mechanisms of social exchange contributes to the explanation of social relationships in society. nine0004

Exchange theory was conceived as an attempt to apply the principles and rules of behavioral psychology research, in combination with other ideas, to the sociological problems of understanding the essence of the social. Provided that the theory of exchange was articulated by the scientific community a long time ago, the peak of its development and relevance falls on the 50-60s of the XX century and is associated with the name of George Homans and Peter Blau.

Provided that the theory of exchange was articulated by the scientific community a long time ago, the peak of its development and relevance falls on the 50-60s of the XX century and is associated with the name of George Homans and Peter Blau.

Theory of social exchange by J. Homans

J. Homans (1910-1989) – prominent American sociologist, author of The Human Group (1950), Social Behavior and Its Elementary Forms (1961), The Nature of Social Science (1967) and others.

The main influence on him was the views of V. Pareto and T. Parsons. Homans criticized the theory of social action and identified patterns in human behavior that correspond to different types of social organization.

Homans' concept was a reaction to the crisis of methodology that arose in America after the war. nine0004

Homans tried to explain how the behavior of an individual with his inherent mental characteristics helps to maintain stable social structures.

The sociologist has long observed face-to-face contact between individuals in small groups in industrial plants. This allowed him to identify some patterns of behavior of people in small groups. So, Homans revealed the dependence of mutual sympathy in a group on the frequency of communication between individuals. By the same reason, the sociologist designated the similarity of behavior and the manifestation of feelings among members of a small group. nine0003 According to Homans, the universal incentives that determine the world movement are personal interests.

This allowed him to identify some patterns of behavior of people in small groups. So, Homans revealed the dependence of mutual sympathy in a group on the frequency of communication between individuals. By the same reason, the sociologist designated the similarity of behavior and the manifestation of feelings among members of a small group. nine0003 According to Homans, the universal incentives that determine the world movement are personal interests.

Sociologist studied elementary forms of social behavior. He identified the determining features of social behavior in human psychology. He also applied the methods of the psychological direction of behaviorism in sociology.

The central definition of Homans' sociology is the notion of social action.

Social action, according to Homans, is the direct contacts of an individual, during which an exchange of values takes place, based on the principle of rationality, i.e. people interact based on a certain interest. They always strive to get the most benefit at the lowest cost. nine0004

They always strive to get the most benefit at the lowest cost. nine0004

The subject of exchange is something that has a social value.

The value of an individual consists of qualities to be exchanged.

But essentially equal exchanges do not exist, which leads to social inequality.

According to J. Homans, human behavior is determined by the rewards that a person received for his actions in the past. Thus, the sociologist defined the principles of reward:

- The frequency of repetition of a certain type of behavior depends on the frequency of rewards. In other words, the more a type of behavior is rewarded, the more often it will be repeated. nine0037

- When rewarding certain types of behavior under certain conditions, the person tries to recreate these conditions.

- The higher the reward, the more effort a person is willing to spend in order to receive this reward.

- If a person's needs are close to saturation, then he will make much less effort to satisfy them.

Thus, proceeding from these provisions, Homans explains the functioning of all social processes. nine0003 The exchange of rewards and punishments is the basis of social action, and human behavior performs the function of payment.

Homans' theory has been criticized, according to which the presented theory cannot explain the functioning of social objects at the macro level.

Theory of exchange P. Blau

P. Blau (1918-2002) - Austro-American sociologist, student of J. Homans, author of "The Dynamics of Bureaucracy" (1955), Exchange and the Power of Social Life (1964).

However, unlike his teacher J. Homans, the sociologist focused not on the mental motives of behavior, but on sociological interactions in different types of social structures.

The main difference between Blau's theory and Homans' theory is that in P. Blau the exchange relations are immediately institutionalized.

Definition 2 Exchange, according to Blau, is an action that depends on rewards received by some people from others and ends with the end of receiving these rewards. nine0004

nine0004

Social life is a "bazaar" in which actors interact with each other in order to obtain the greatest benefit.

P. Blau defined the following laws of exchange:

- The greater the benefit a person expects, the greater the likelihood of a certain activity.

- The more rewards people have exchanged with each other, the more likely the following acts of exchange are.

- The more often mutual obligations are violated during the exchange, the less the role of negative sanctions (punishments) becomes. nine0037

- As the moment of reward approaches, the value of the activity decreases, and the probability of its implementation is significantly reduced.

- The more exchange relationships that take place, the more likely it is that the exchange will be governed by the rules of "fair exchange".

Blau extrapolated the laws of exchange to interactions between organizations and other social structures. In their relationship, the exchange is indirect, therefore it is indirect. Factors of normativity and control actively "intervene" in it. This interpretation made it possible for Blau to transfer the interpretation of exchange from the micro level to the meso level. nine0004

Factors of normativity and control actively "intervene" in it. This interpretation made it possible for Blau to transfer the interpretation of exchange from the micro level to the meso level. nine0004

P. Blau defined the following types of rewards:

- money;

- social approval;

- respect;

- concessions.

Those in power receive the highest rewards. That is why social groups are structured according to the principles of a hierarchy of power, prestige, approval, etc.

Power relations form two forces in the group: on the one hand, the desire for integration, on the other hand, the inclination towards opposition and conflict. The main source of conflict is the imbalance in exchange relations, resulting from the unequal attitude of various associations to the possession of resources. nine0003 Conflict, according to P. Blau, is a source of change, clarification of normativity and values.

Social structures were interpreted by the sociologist as a multidimensional space, which is formed by lines of differentiation. He characterized them as a series of successive levels on an ever larger scale. Let's take an example. The structure of the work collective has a direct social environment - the conditions in the organizational unit where they work. In the structure of the firm, the immediate social environment will be market conditions. nine0004

He characterized them as a series of successive levels on an ever larger scale. Let's take an example. The structure of the work collective has a direct social environment - the conditions in the organizational unit where they work. In the structure of the firm, the immediate social environment will be market conditions. nine0004

Blau tried to integrate the theory of exchange and social structure in the context of social interaction.

Exchange theory alone cannot explain complex social structures. Similarly, the theory of social structure alone is not able to explain many relationships and processes in society, because it is deprived of the analytical possibilities of characterizing people's behavior.

P. Blau outlined two "pictures" of social analysis.

- The first picture is the result of using the theory of exchange to analyze the micro-processes that are associated with interpersonal interaction. nine0037

- The second picture is the active application of the theory of social structure to characterize the macro-processes of society.

Here the main problem is the depth and density of the connection between these levels of analysis.

Here the main problem is the depth and density of the connection between these levels of analysis.

Summing up, it is important to note that the theoretical and practical resources of the theory of social exchange have not been fully exhausted to date. Social exchange permeates the daily social life of people. Social exchange

defines various levels of social interaction, acts as real and ideal models of behavior. nine0004

Problem solving from 1 day / from 150 rubles Course work from 5 days / from 1800 rubles abstract from 1 day / from 700 rubles nine0004

Social exchange: scope and significance

Various scientific concepts seek to answer these and other questions and explain the nature of complex social interaction. One of them is the theory of social exchange, which became an independent branch of sociology in the 1950s and 1960s. XX century. It is based on the idea that the driving force of social communication is the desire of its participants to receive various kinds of rewards (direct and indirect, tangible and intangible). nine0004

One of them is the theory of social exchange, which became an independent branch of sociology in the 1950s and 1960s. XX century. It is based on the idea that the driving force of social communication is the desire of its participants to receive various kinds of rewards (direct and indirect, tangible and intangible). nine0004

The methodological basis of the theory of social exchange was one of the leading areas of American psychology - behaviorism (from the English "behavior" - behavior), which had a serious impact on ideas about the human psyche. According to behaviorism, human behavior is controlled by reactions (motor, emotional, verbal, etc.) to certain influences (stimuli) from the environment. That is, behavior is a response to the impact of a particular stimulus. And the stronger the stimulus, the faster the response to it. At the same time, the incentive that contributes to obtaining the greatest preferences turns out to be the most attractive, since in the process of interacting with each other, people strive to obtain the maximum benefit. We are talking about the very principle of reward, which formed the basis of the theory of social exchange. nine0004

We are talking about the very principle of reward, which formed the basis of the theory of social exchange. nine0004

Representatives of this scientific direction were interested, first of all, in the models of formation of behavioral norms at the level of interpersonal interaction. The mental and cultural characteristics of a person, his consciousness, thinking and complex emotional world did not find a worthy place within their teachings, for which they were constantly criticized by a significant part of the professional community. Among the advantages of the direction are exceptional attention to the human psyche, bold experiments, and the introduction of mathematical methods of analysis into psychology. nine0004

One of the founders of behaviorism, Burres Frederick Skinner (1904-1990), introduced into scientific circulation the concept of the so-called "operant behavior" (actions aimed at obtaining the desired result), which is based on the mutually beneficial cooperation of people in the process of communication. The essence of the term is that an action (or inaction) is affected by its consequences. The action occurs under the influence of a certain stimulus, and the consequence is often a reward for the efforts made. nine0004

The essence of the term is that an action (or inaction) is affected by its consequences. The action occurs under the influence of a certain stimulus, and the consequence is often a reward for the efforts made. nine0004

These Skinner ideas had a significant impact on the founder of the theory of social exchange, George Homans (1910-1989), who admitted that his sphere of interest was not consciousness, but the actions of people: “We will be much more interested in the actions of people than their relationships, especially if the latter do not lead to action. We are fed up with the social science in which people always 'orient themselves', or in fact only 'orient themselves' towards action, but never act"[1]. The five axioms of the theory of exchange put forward by Homans (with some assumptions) corresponded to these principles

1. Axiom of success: "It is true of all human actions that the more frequently they are encouraged, the more likely they are to be repeated." At the same time, the more often a person is encouraged, the more active will be his actions that contribute to such a result. However, rewards that are too frequent are satiating, so occasional rewards are sometimes welcome.

However, rewards that are too frequent are satiating, so occasional rewards are sometimes welcome.

2. Stimulus axiom: “If in the past one or another stimulus (or set of stimuli) was associated with a reward for an act, then the more similar other stimuli are to it, the more likely it is that a person will reproduce the same or similar act.” Among examples, Homans gives the following: if a person caught a fish in a dirty pond, he will try to do it again, since his actions once led to the desired result. But if the conditions under which success was achieved were too difficult, or the reward was received too quickly, this postulate may not work. nine0004

3. Axiom of value: “The more valuable the result of his action seems to a person, the more likely he is to reproduce this action.” Values can be both tangible (money, etc.) and intangible (any kind of help, advice, etc.).

4. Axiom of deprivation-satiation: "The more regularly a person's deed is rewarded, the less he begins to appreciate each subsequent reward. " Homans draws attention to the ratio in this case of price and benefit, since only that action is beneficial, the reward for which exceeds the costs. And, therefore, the greater the benefit a person derives from his actions, the more likely he is to repeat them in the future. nine0004

" Homans draws attention to the ratio in this case of price and benefit, since only that action is beneficial, the reward for which exceeds the costs. And, therefore, the greater the benefit a person derives from his actions, the more likely he is to repeat them in the future. nine0004

5. Axiom of aggression-approval: "If the action does not cause the expected reward or, on the contrary, causes an unexpected punishment, then the acting subject will experience a feeling of anger: the likelihood that aggressive behavior will be more valuable to him will increase." Being an adherent of behaviorism, Homans here still admits the existence of conscious states of mind that affect human behavior.[2]

Thus, the theory of social exchange proposed by J. Homans was created under the serious influence of the ideas of behaviorism, which in a number of cases were directly transferred from the field of psychology to the sociological context (since the scientist considered the psychological models of human behavior to be universal). The disadvantage of Homans' concept can be considered that he focused only on the mutually beneficial cooperation of people, which significantly limits the scope of scientific understanding. Concentrating only on the level of behavioral reflexes within the framework of elementary social behavior, the researcher did not go beyond the study of interpersonal social interaction. The mechanisms for the formation of larger social formations could not "fit" into his theory of exchange. The sociologist even considered the emergence of power as a special case of asymmetric social exchange, in which “one person has a greater ability to reward others in exchange than others can reward him”[3]. At the same time, this asymmetry, according to the idealistic views of the scientist, tends to level out as a result of social evolution. nine0004

The disadvantage of Homans' concept can be considered that he focused only on the mutually beneficial cooperation of people, which significantly limits the scope of scientific understanding. Concentrating only on the level of behavioral reflexes within the framework of elementary social behavior, the researcher did not go beyond the study of interpersonal social interaction. The mechanisms for the formation of larger social formations could not "fit" into his theory of exchange. The sociologist even considered the emergence of power as a special case of asymmetric social exchange, in which “one person has a greater ability to reward others in exchange than others can reward him”[3]. At the same time, this asymmetry, according to the idealistic views of the scientist, tends to level out as a result of social evolution. nine0004

And although Homans' merits in describing a number of regularities in human behavior are indisputable, the American sociologist, describing the processes and results of social exchange, underestimated the role of the social system of society, a number of social institutions in the process of human interaction. Consequently, his theory of social exchange, limited to the interpretation of the behavior of individuals in small groups, cannot give an idea of large-scale social phenomena. In addition, it is obvious that exchange is an important, but not the only form of social communication. nine0004

Consequently, his theory of social exchange, limited to the interpretation of the behavior of individuals in small groups, cannot give an idea of large-scale social phenomena. In addition, it is obvious that exchange is an important, but not the only form of social communication. nine0004

The theory of social exchange owes its development to another eminent American sociologist. Peter Mikael Blau (1918-2002), supplementing the teachings of J. Homans, used the principles of social exchange to explain the functioning of society's macrostructures. Blau's task was to "understand social structure by analyzing the social processes that govern relations between individuals and groups. The main question ... is how social life is organized into more complex structures of human associations” [4]. nine0004

Unlike Homans, Blau focuses his efforts on the study of individual actions not in themselves, but as tendencies within large social structures. The transition from elementary to complex social structures is important: “The main goal of the sociological study of the processes of interpersonal interaction is to lay the foundation for understanding evolving social structures and emerging emergent[5] social forces that characterize the development of the latter”[6].

To achieve this goal within the framework of social exchange, Blau proposes a four-stage model for the transition from interpersonal exchange to social education:

1. Interpersonal exchange. Stops at the stage when the reward is not provided with equal resources.

2. Differentiation of status and power. Provides a transition to the creation of an organization recognized by all participants.

3. Legitimation and organization. The social structure that emerged as a result of interpersonal exchange begins to influence this exchange. At this stage, there are two types of social organization: emergent groups that appeared in the process of natural integration, and specially created groups to achieve specific goals[7]. nine0004

4. Opposition and change. At this stage, there is opposition to the system and, as a result, a change in the existing system. The strength of the opposition depends on solidarity, cohesion, politicization, and the expressiveness of the ideology of opposition groups and parties.

Thus, in contrast to Homans' theory of exchange, "Blau's mediating in the stimulus-response scheme are relations of power, understood as the establishment of a legitimate monopoly on rewards, organizationally formalized as ranks-statuses"[8]. To legitimize power in the eyes of society, it is necessary to have norms and values shared by all participants in social exchange. They also act as connecting links in large social organizations when direct interaction between participants is impossible: “Generally speaking, everyone agrees that values and norms serve as mediators of social life and connecting links of social interaction. They make indirect (indirect) social exchange possible and govern the processes of social integration and differentiation in complex social structures, as well as the processes of social organization" [9]. At the same time, the concept of norm reflects the nature of the exchange between the individual and the community, and the concept of value allows us to explore the relationship between communities.

This interpretation expands the simplified scheme of J. Homans, who did not go beyond interpersonal exchange. “Shared values can be perceived as mediating links in social transactions, expanding the boundaries of social interaction and the structure of social relations in social space and time. Consensus on the issue of social values serves as the basis for removing social interactions beyond direct social contacts and for establishing social structures for a period longer than the length of a human life”[10], Blau noted. Essentially, social exchange is the exchange of values within society. Common values act as mediators, both in the processes of social integration and in the case of conflicts and confrontation, they also legitimize the social order. nine0004

The scientist identified four types of values. The first - particularistic values - are the basis of integration and solidarity in social groups. They unite people on the basis of concepts that are equally important for each of them (the reputation of an institution/institution, patriotism, duty, etc. ), extending personal feelings to collective relations. It is these values that form groups within society. The second type - universal values - perform the functions of evaluating objects of exchange, and also determine the value of an individual contribution and reward for it (empowerment, increase in social status). These values give an idea of the significance for society of the actions of its members. The third type of values - the so-called "legitimate authority" performs the function of social control over the distribution of power. We are talking about a value system that allows some people to have more power than others (this is how bosses appear - from the director of a small institution to the president of a country). This system requires social control, which allows organizing the fourth type of values - oppositional ones. These values legitimize the opposition, make it possible to explain the essence of social conflicts, and are the basis of social development.

), extending personal feelings to collective relations. It is these values that form groups within society. The second type - universal values - perform the functions of evaluating objects of exchange, and also determine the value of an individual contribution and reward for it (empowerment, increase in social status). These values give an idea of the significance for society of the actions of its members. The third type of values - the so-called "legitimate authority" performs the function of social control over the distribution of power. We are talking about a value system that allows some people to have more power than others (this is how bosses appear - from the director of a small institution to the president of a country). This system requires social control, which allows organizing the fourth type of values - oppositional ones. These values legitimize the opposition, make it possible to explain the essence of social conflicts, and are the basis of social development. They manifest themselves in social groups that have not found recognition in legitimate institutions. The function of this type of values is to change the social structure of society. Being a “counter-institutional component”, oppositional values are “basic values and ideals that have not been implemented and have not found their embodiment in explicit institutional forms, which is why they become a force for social change”[11]. An example of the embodiment of oppositional values is the emergence of socialism in a capitalist society. nine0004

They manifest themselves in social groups that have not found recognition in legitimate institutions. The function of this type of values is to change the social structure of society. Being a “counter-institutional component”, oppositional values are “basic values and ideals that have not been implemented and have not found their embodiment in explicit institutional forms, which is why they become a force for social change”[11]. An example of the embodiment of oppositional values is the emergence of socialism in a capitalist society. nine0004

Thus, according to Blau's concept, "value context is a means that forms social relations." In addition, “social values mediate bonds in social associations and interactions on a large scale”[12]. Values determine the formation of the main social processes - integration, differentiation, organization and confrontation.

“Value consensus”, based on the theory of social exchange, allowed Peter Blau to develop the concept of power, which is nothing but a kind of social exchange, defined as “the ability of individuals or groups to impose their will on others in spite of their resistance through the threat of punishment or refusal to regular rewards, since both the first and the second, in the end, act as negative sanctions”[13]. It is curious that the dividing line between positive and negative sanctions is often conditional, since “the only difference between punishment and reward can be revealed only in relation to the initial position of the object, i.e. in comparison with the situation that took place before the subject's attempts to influence the object. If the position of the object has worsened, then we are talking about punishment, if it has improved, about rewards” [14]. Negative sanctions are not always in the realm of physical coercion: “People can be forced to do something out of fear of losing their jobs, losing their social status, paying a fine, or being ostracized”[15]. Often, the absence of the expected reward from the subject of power is perceived as a punishment. nine0004

It is curious that the dividing line between positive and negative sanctions is often conditional, since “the only difference between punishment and reward can be revealed only in relation to the initial position of the object, i.e. in comparison with the situation that took place before the subject's attempts to influence the object. If the position of the object has worsened, then we are talking about punishment, if it has improved, about rewards” [14]. Negative sanctions are not always in the realm of physical coercion: “People can be forced to do something out of fear of losing their jobs, losing their social status, paying a fine, or being ostracized”[15]. Often, the absence of the expected reward from the subject of power is perceived as a punishment. nine0004

The source of power in the process of exchange is the distribution of available resources, which causes the superiority of some and the dependence of others. Power allows you to exchange resources for the "necessary" behavior, it owns the tools of distribution and deprivation of rewards. Power includes special types of influence: “Inciting a person to provide a service for a reward is not the exercise of power over him until the ongoing rewards make him obey the command, and not just provide these services” [16]. At the same time, freedom of choice is only in one thing: instead of obedience, you can choose punishment. nine0004

Power includes special types of influence: “Inciting a person to provide a service for a reward is not the exercise of power over him until the ongoing rewards make him obey the command, and not just provide these services” [16]. At the same time, freedom of choice is only in one thing: instead of obedience, you can choose punishment. nine0004

This concept of power, born in the framework of Peter Blau's theory of social exchange, corresponds to the classical definition of power formulated by Max Weber: "Power means any opportunity to exercise one's own will within given social relations, even against resistance, regardless of what this possibility is based on" [17]. A feature of power in both concepts is subordination. However, in the case of an ideal embodiment of the exchange theory with its postulates of mutually beneficial cooperation and partnership, the power structure would not have such a serious foundation in the form of goods and resources, and, consequently, leverage on those who do not possess them. nine0004

nine0004

Unlike George Homans, who developed the psychological concept of the theory of exchange, Peter Blau, taking the same interpersonal relations as a basis, revealed on their basis (taking into account their constant complication and development) the mechanisms for the formation of large social structures. Having expanded the theory of exchange to macroprocesses, Blau, nevertheless, did not cease to assert that interpersonal relations lie at its basis. However, these relationships go beyond the behaviorist concept of man and his capabilities. They develop both within the framework of social, as well as political and economic interaction of subjects on the basis of receiving remuneration in response to the efforts expended. At the same time, large social structures ideally perform only organizational and regulatory functions. And the opposition (“regenerating force”) is necessary for the redistribution of resources. nine0004

The theory of social exchange, despite the unceasing criticism of the narrowness of its concept and the weakness of the operated tools, expands the understanding of social organization, the basic principles of social interaction, allows for the analysis of various processes of social development, and its capabilities in the field of social forecasting are especially relevant in the conditions of modern reality .

The exchange theory still has its followers and opponents. In many ways, the limitations of this theory are related to the criticism of its initial premises, that is, behaviorism. But the ideas of Peter Blau and his colleagues work in practice. Often, even social and charitable projects involve the exchange, albeit unequal, and intangible values. Understanding the mechanisms of this exchange can help to understand why it is important for people to have their merit appreciated, and whether it is possible to build relationships based on mutual evaluation. nine0178

[1] Theory of exchange by J. Homans//http://socio.rin.ru/cgi-bin/article.pl?id=1311

[2] Osipov G.V. History of sociology of Western Europe and the USA. M., 2001. S. 408-411.

[3] Gromov I.A., Matskevich A.Yu., Semenov V.A. Western theoretical sociology. M., 1996. S. 110.

[4] Ritzer J. Modern sociological theories. St. Petersburg, 2002. P. 328.

P. 328.

[5] Emergent social forces (groups) appear in the process of integration. They are not affected by the type of activity of people, nor their quality. They arise from associations as a whole. nine0004

[6] Diao Liming. The social structure of modern societies in Russia and China: dissertation abstract for the degree. candidate of sociological sciences. Vladivostok, 2010. P.27.

[7] In advancing the thesis about these types of organizations, Peter Blau went beyond the narrow framework of the “elementary social behavior” of the behaviorists.

[8] Peter Mikael Blau//The latest philosophical dictionary. Ufa, 1998. P. 81.

[9] Osipov G.V. Decree op. P. 416.

[10] Ibid. P.417. nine0004

[11] Ostrovskaya E.A. Institutionalization of the religious model of society. Abstract of the dissertation for the degree of doctor of sociological sciences. SPb., 2003.

[12] Osipov G.V. Decree op. P. 417.

[13] Ledyaev VG Power: conceptual analysis.