What is psychological distress

Psychological Distress | Cardiac College

Psychological distress happens when you are faced with stressors that you are unable to cope with. Take action to improve your distress.

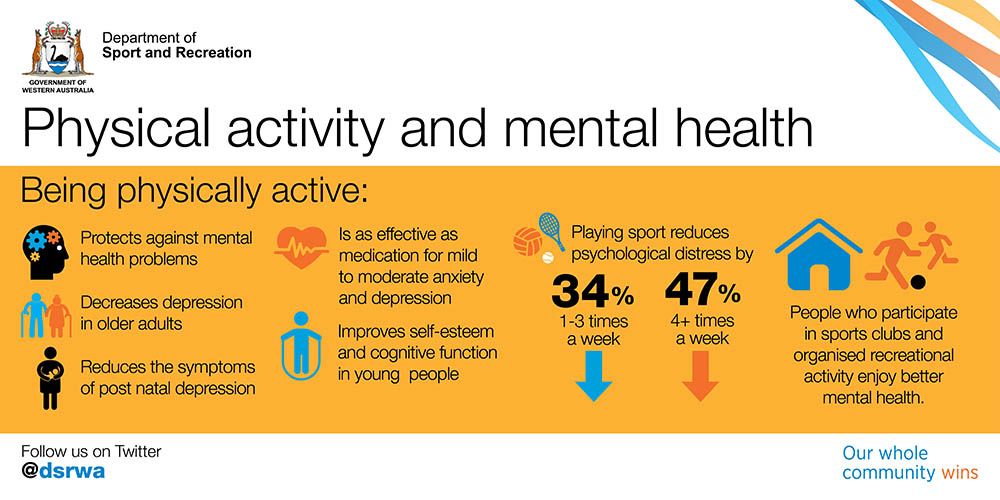

- Make lifestyle changes.

- Learn stress management techniques.

- Work with a psychologist, social worker or psychotherapist.

- Talk to your doctor about medications that could help you.

What Is Psychological Distress?

When you have been facing stress in your life for a while, you may feel overwhelmed.

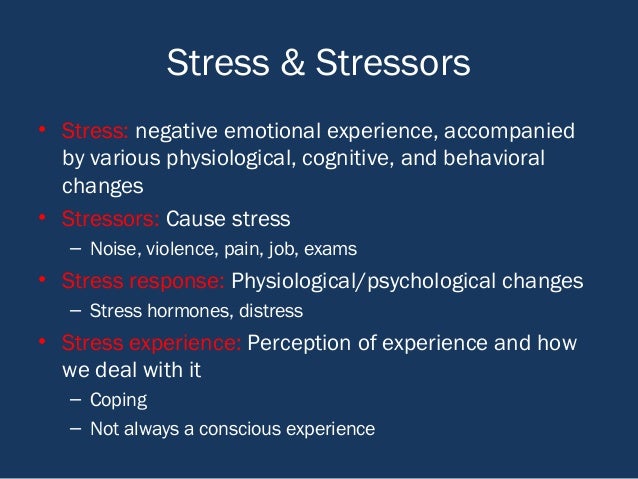

Psychological distress describes the unpleasant feelings or emotions that you may have when you feel overwhelmed. These emotions and feelings can get in the way of your daily living and affect how you react to the people around you.

What Causes Psychological Distress?

Psychological distress happens when you are faced with stressors that you are unable to cope with.

These stressors could be:

- traumatic experiences

- major life events

- everyday stressors such as workplace stress, family stress, and relationships

- health issues

What Does Psychological Distress Feel Like?

We all react differently to stress and to changes in our lives.

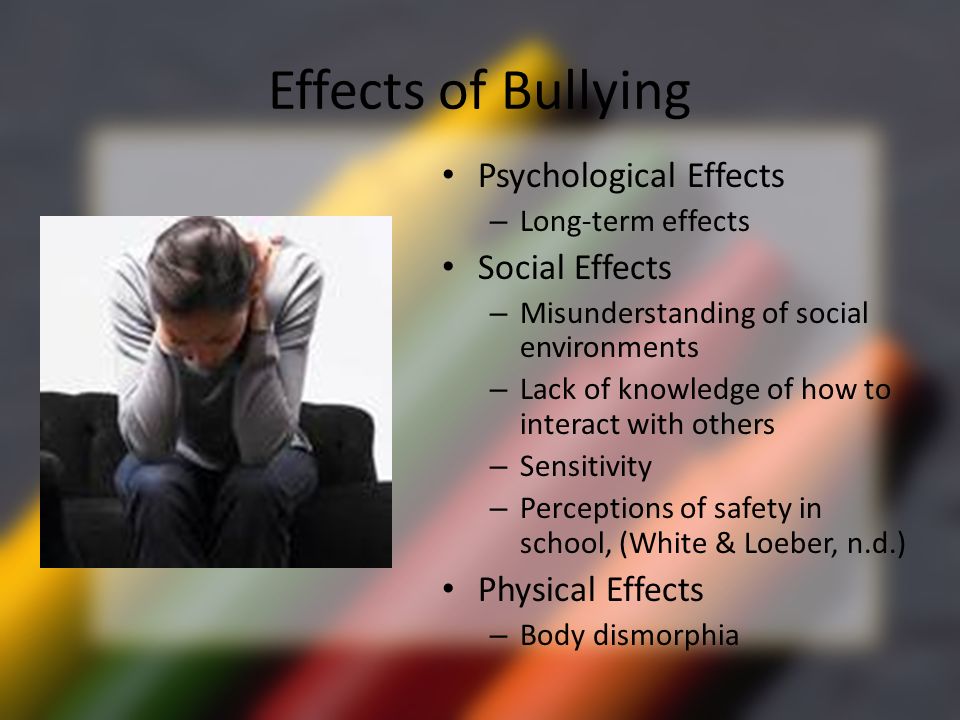

Psychological distress can come out as:

- fatigue

- sadness

- anxiety

- avoidance of social situations

- fear

- anger

- moodiness

How Does Psychological Distress Affect My Heart?

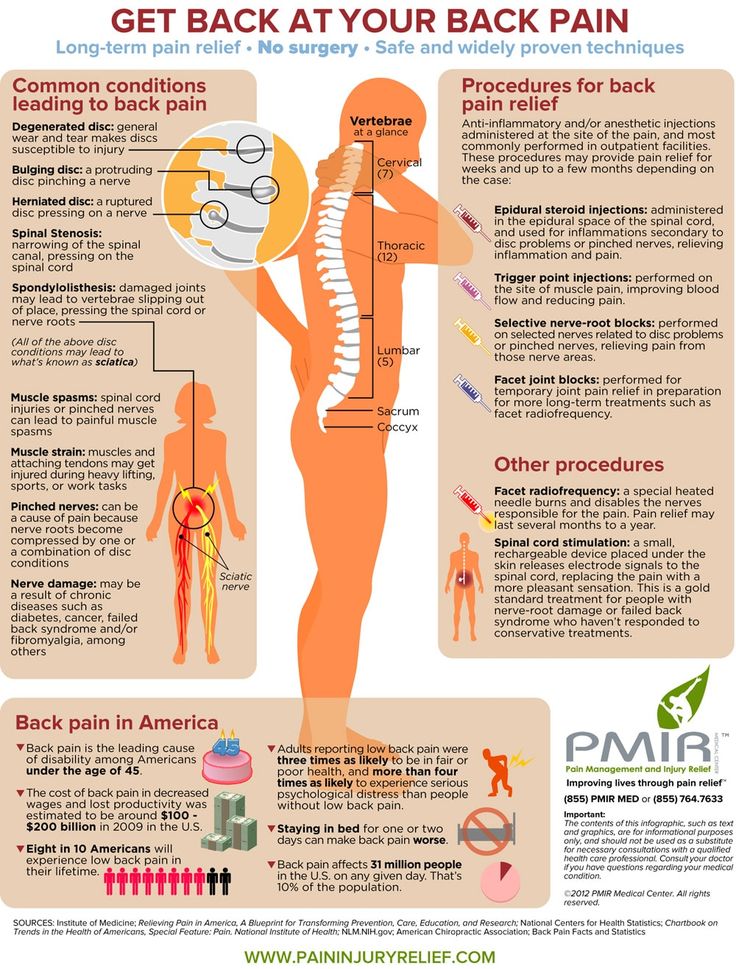

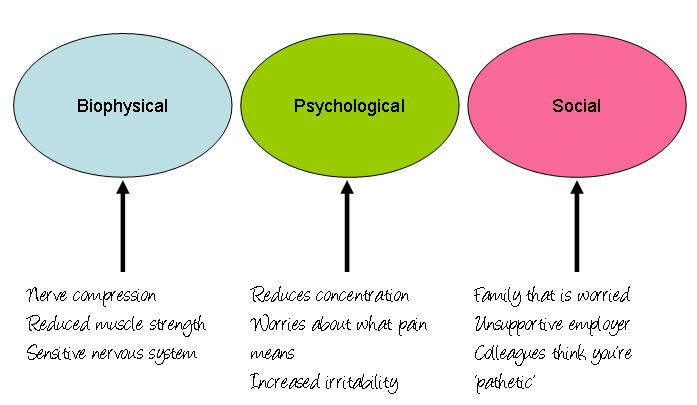

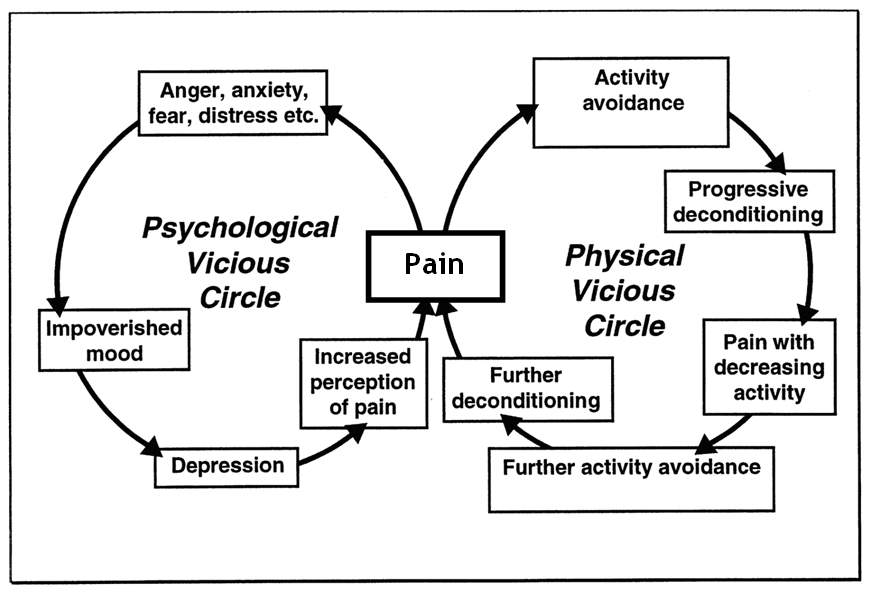

Psychological distress affects your body by:

- releasing stress hormones into your blood that cause your heart rate and blood pressure to rise.

- causing inflammatory reactions in your body that can increase plaque build-up in your arteries.

- causing your blood to become stickier. This puts you at risk for developing blood clots.

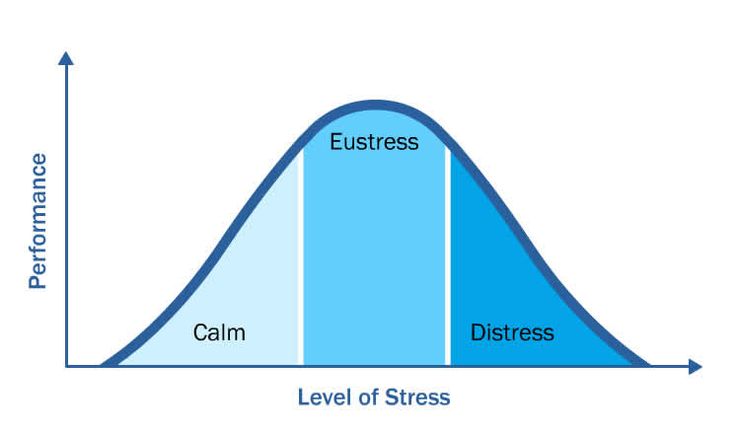

People with moderate levels of psychological distress are twice as likely to die from heart disease or other chronic illness as people with low levels of psychological distress. People with higher levels of distress have an even higher risk.

Moderate Levels of Distress

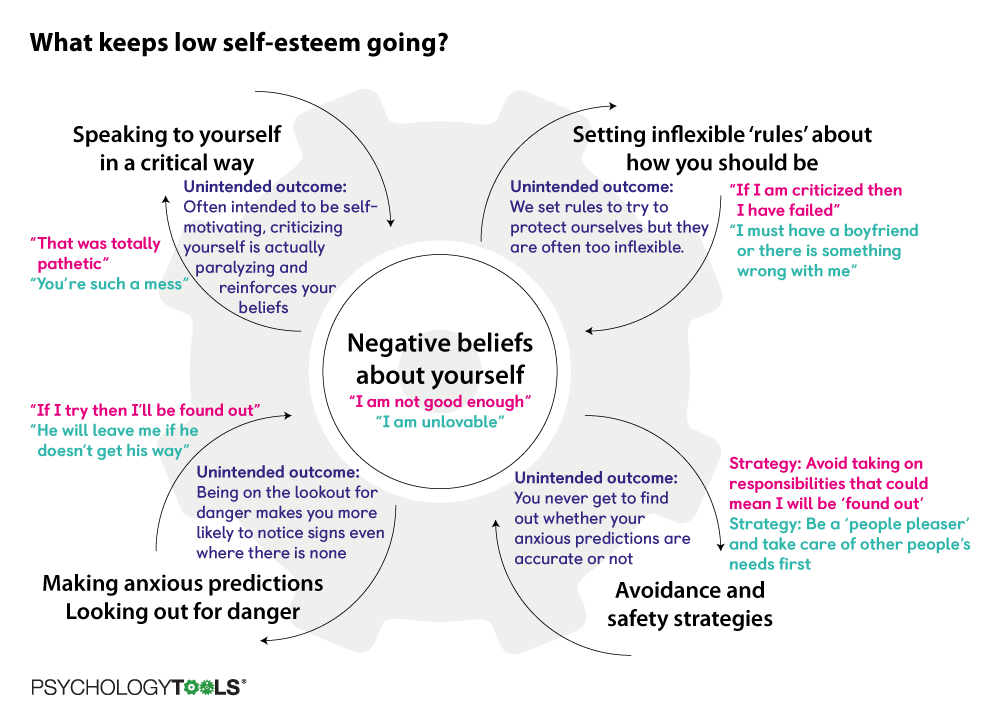

If you have moderate levels of psychological distress, you will have negative reactions to challenges in your daily life.

It is important to:

- know what causes your distress (for example, are there certain activities or people that cause you distress?)

- know what helps your distress

Take action if you have moderate psychological distress

- Make lifestyle changes.

- Monitor the daily activities that cause you distress.

- Minimize these activities.

- Talk to someone you trust about how to manage these stressors better.

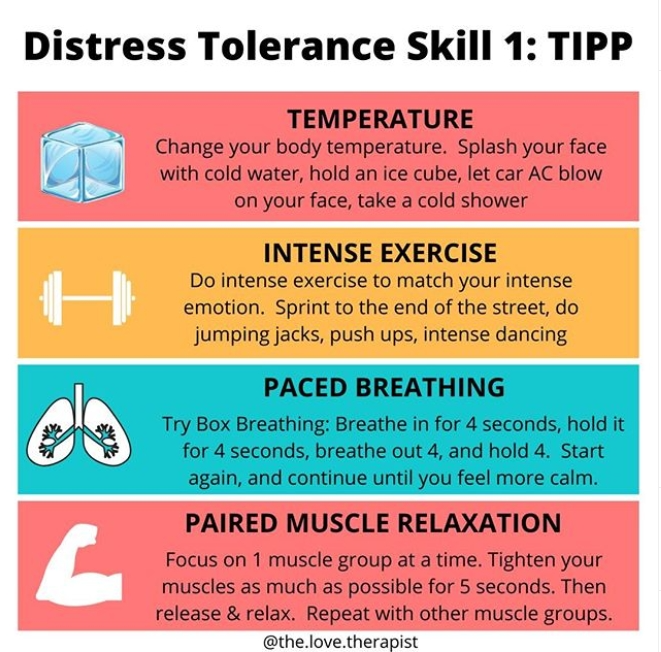

- Learn stress reduction skills such as:

- diaphragmatic breathing techniques (learning to breathe from your diaphragm or stomach)

- progressive muscle relaxation skills or yoga

- visualization

- affirmations

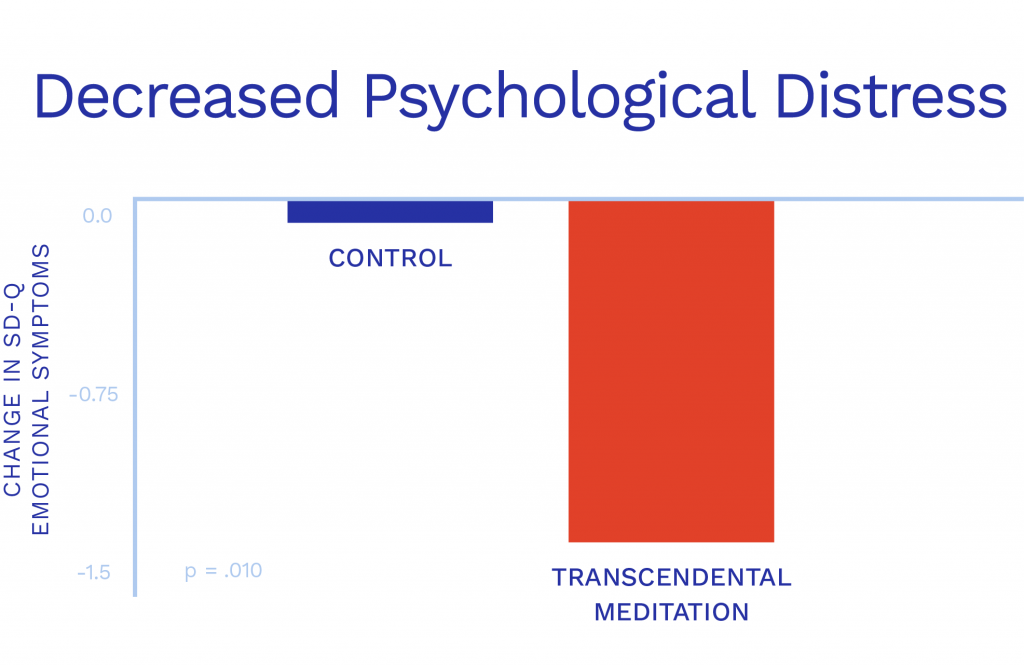

- meditation

- cognitive reframing (changing negative thoughts or learning to look at things differently)

- take a stress reduction program

High Levels of Distress

If you have high levels of distress, you are likely to develop chronic problems that affect you emotionally and physically. This is because you are feeling the mental emotions of distress and your body’s physical reaction to stress for a long time.

This is because you are feeling the mental emotions of distress and your body’s physical reaction to stress for a long time.

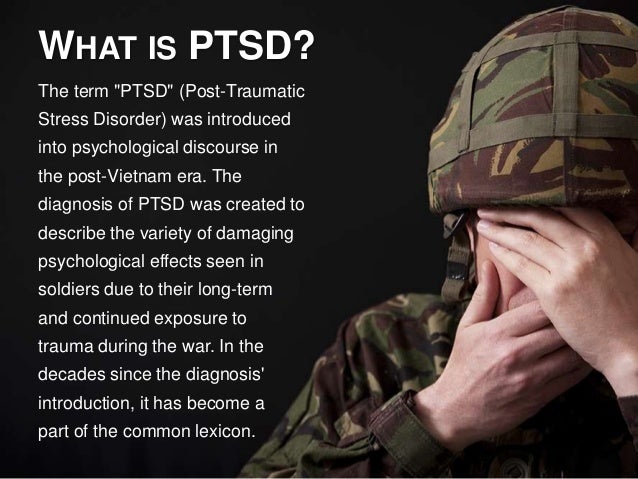

When the emotions of distress lead to psychiatric problems (mental illness), it is harder to change.

People with heart problems who also have high levels of distress may have:

- attention deficit disorder

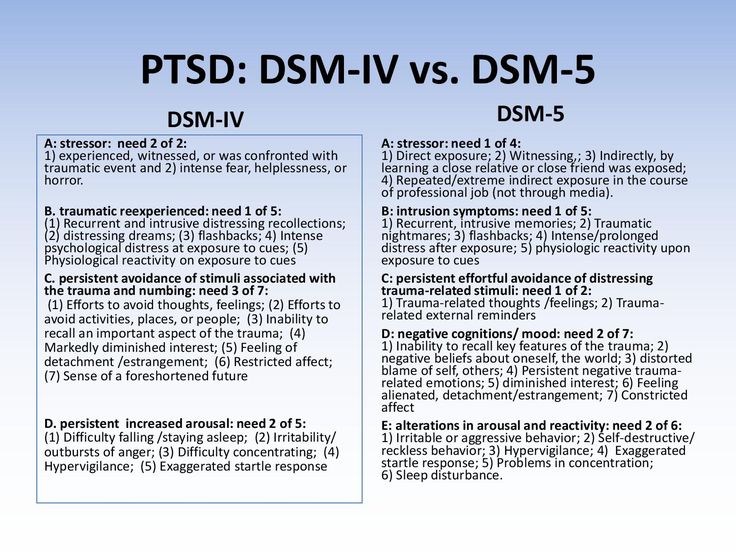

- anxiety disorders such as panic attacks, worry and post traumatic syndromes. Learn the signs of anxiety disorders and what to do if you have them »

- depression. Learn the signs of depression and what to do if you have them »

A high level of psychological distress doubles your risk of having more heart problems. If you have high levels of psychological distress you need to take steps to reduce stress.

Take action if you have high psychological distress

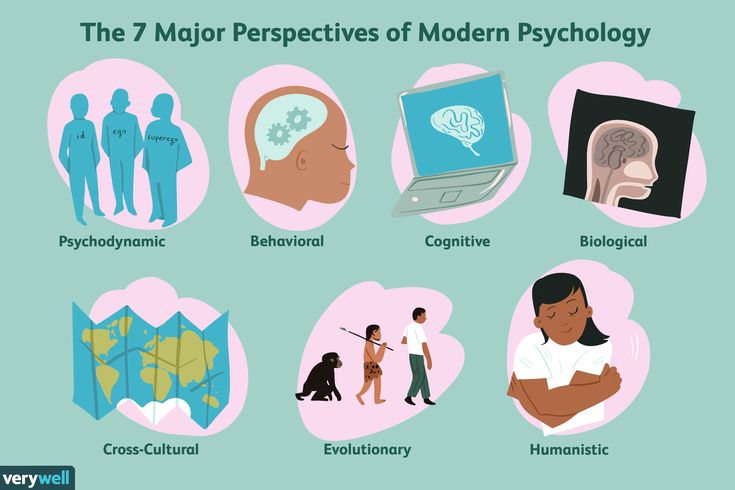

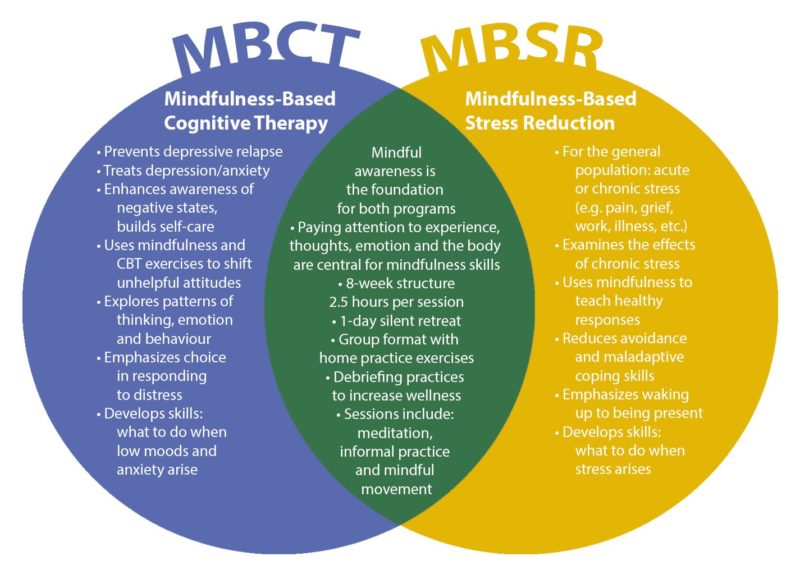

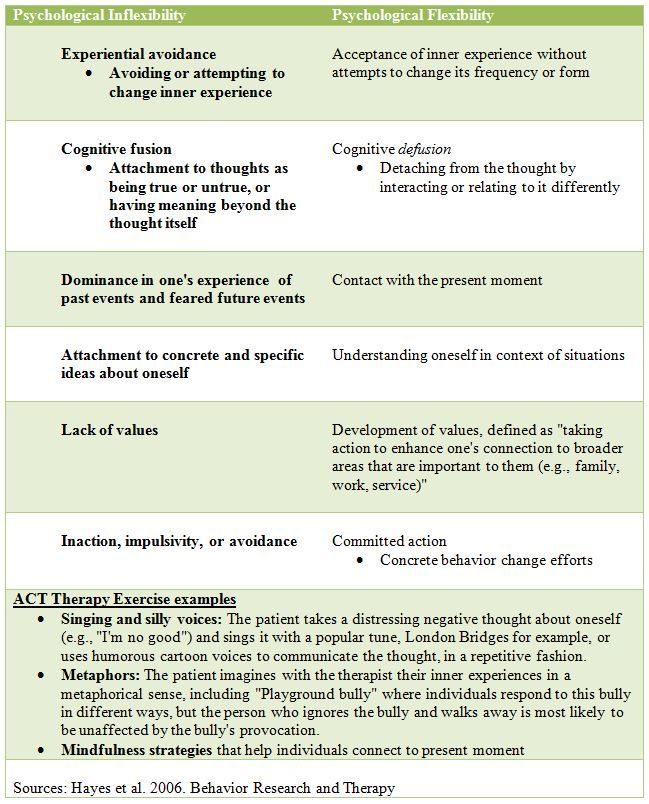

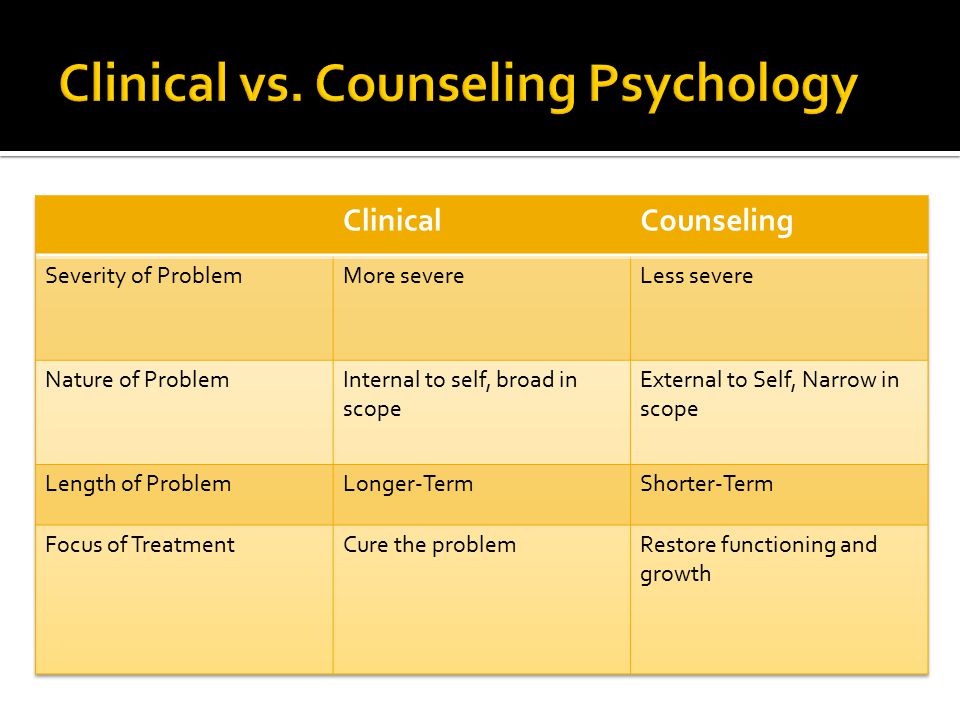

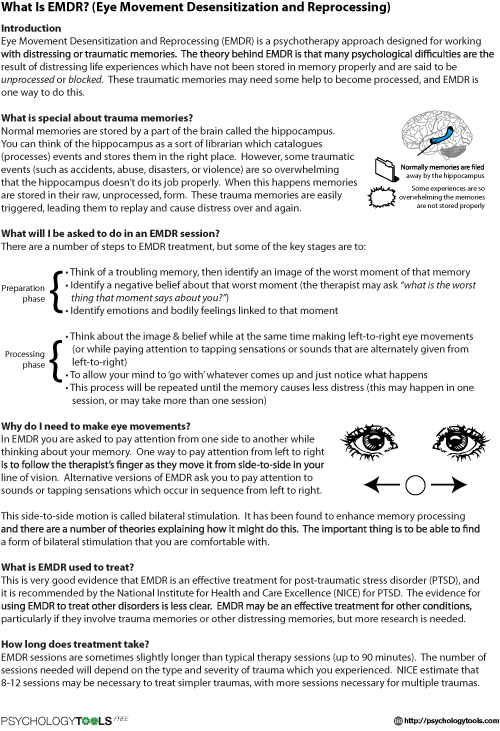

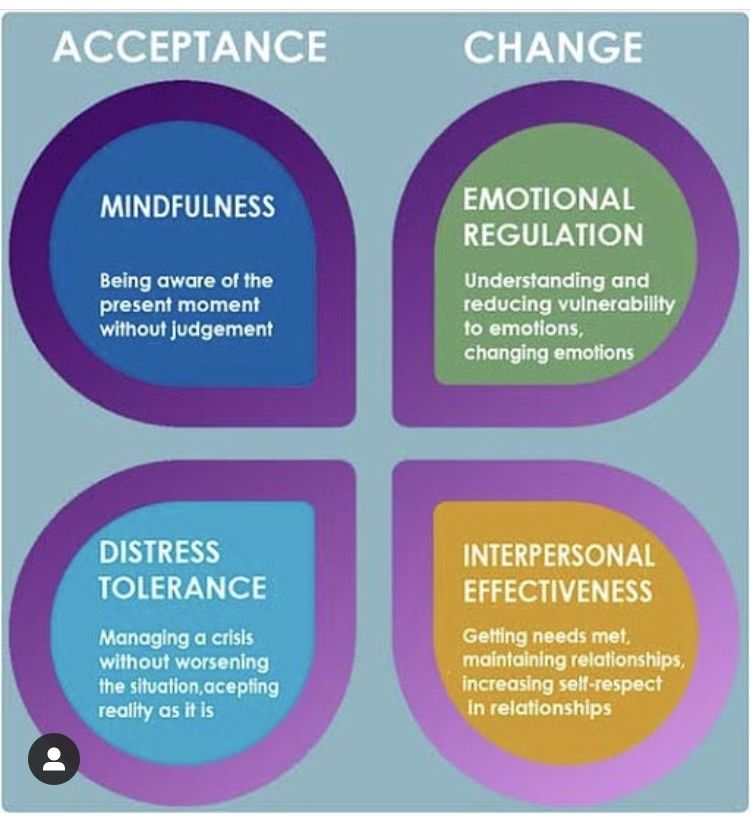

- Work with a psychologist, social worker or psychotherapist. They will guide you through making changes in your life using techniques like:

- cognitive behavioural therapy.

Learn about cognitive behavioural therapy (opens in new window) »

Learn about cognitive behavioural therapy (opens in new window) » - interpersonal therapy. Learn about interpersonal therapy (opens in new window) »

- brief psychodynamic therapy. Learn about brief psychodynamic therapy (opens in new window) »

- behavioural therapies. Learn about behavioural therapies (opens in new window) »

- Talk to your doctor about medications that could help you.

- Take a stress reduction program.

Resources

The following books are recommended resources to help with Psychological Distress.

- Minding the Body, Mending the Mind. 2nd Edition (2007). Joan Borysenko, Bantam Books: New York

- Mind your Heart (2004). Aggie Casey and Herbert Benson, Free Press; New York

- Undoing Perpetual Stress: The Missing Connection between Depression, Anxiety and 21st Century Illness (2005). Richard O’Connor, Berkley Books: New York.

- 7 Easy Steps to Less Stress and Better Sleep (2011).

Jaan Reitav.

Jaan Reitav. - Stress Less: The New Science that Shows Women how to Rejuvenate the Body and the Mind (2010).

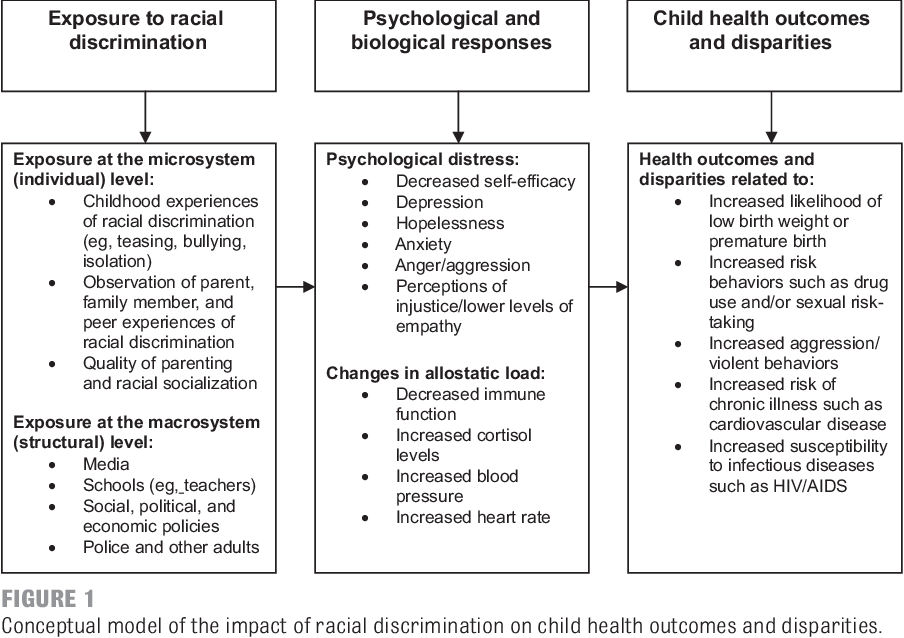

Factors Linked to Psychological Distress

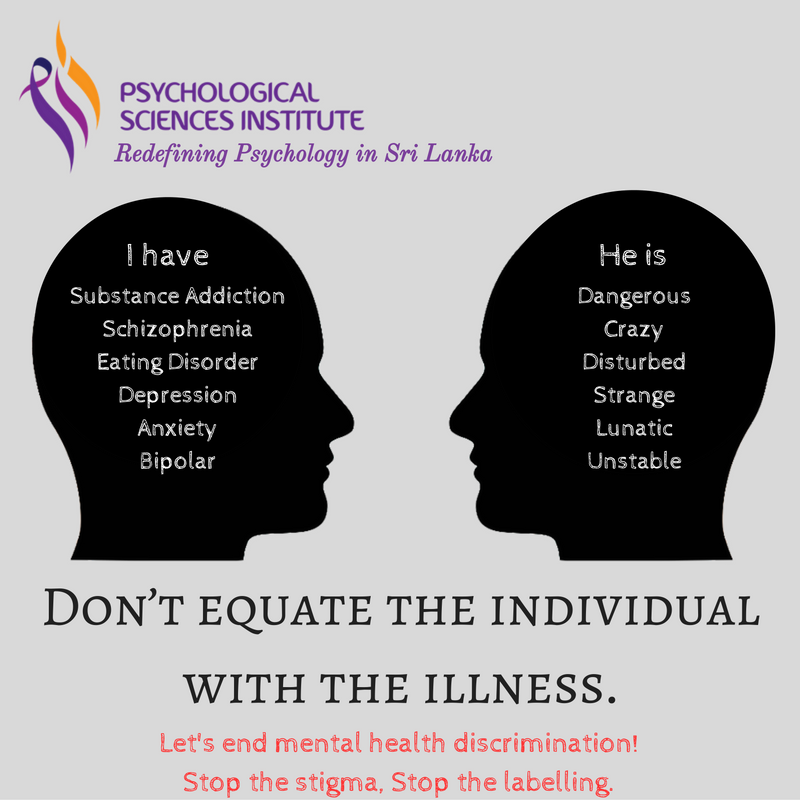

Psychological distress, a widely-used indicator of the mental health of a population, nevertheless remains vaguely understood. In numerous studies, psychological distress is “largely” defined as “a state of emotional suffering characterized by symptoms of depression and anxiety.” But how do you know if what you’re experiencing is psychological distress or a diagnosable psychological disorder, such as anxiety or depression? If you’ve had a bad day, does that mean you’re suffering psychological distress? If you lose your job and feel anxious and short-tempered, is this a sign you are in a state of psychological distress?

Psychological Distress Vs. Psychological Disorder

Psychological distress is generally considered a transient (not long-lasting) phenomenon that is related to specific stressors. It typically subsides when either the stressor is removed, or the individual adapts to the stressor.

It typically subsides when either the stressor is removed, or the individual adapts to the stressor.

- In the example of having a bad day, you’re likely experiencing transient psychological distress. Tomorrow is another day, bringing with it the opportunity to see things differently, start anew, employ healthier self-protective measures and more.

- On the other hand, if you’ve lost your job and are irritable, anxious, quick-to-anger and display other negative emotions and behavior, and such distress continues for some period of time and now interferes with your daily activities, you may have crossed over from psychological distress of a transient nature to a more deeply-embedded psychological disorder requiring treatment.

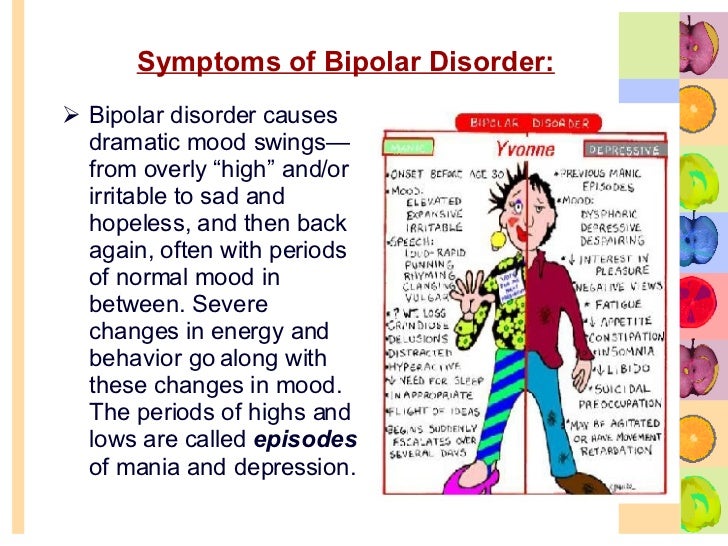

Distress that is characteristic of psychological disorders, such as anxiety and depression, involves functional impairment and “clinically significant distress” (also called “marked distress”). With anxiety disorders, symptoms do not go away and worsen over time. They also interfere with daily activities such as job, school, and relationships. To be diagnosed with depression, severe symptoms (negatively affecting how you feel, think and handle daily activities) must be present for two weeks.

They also interfere with daily activities such as job, school, and relationships. To be diagnosed with depression, severe symptoms (negatively affecting how you feel, think and handle daily activities) must be present for two weeks.

Signs of Psychological Distress

You likely know when something is off with someone you love, or within yourself. It could be transient and resolved rather quickly, or it could be indicative of an accumulation of factors causing psychological distress. WebMD lists a number of signs of emotional distress that equally apply to psychological distress.

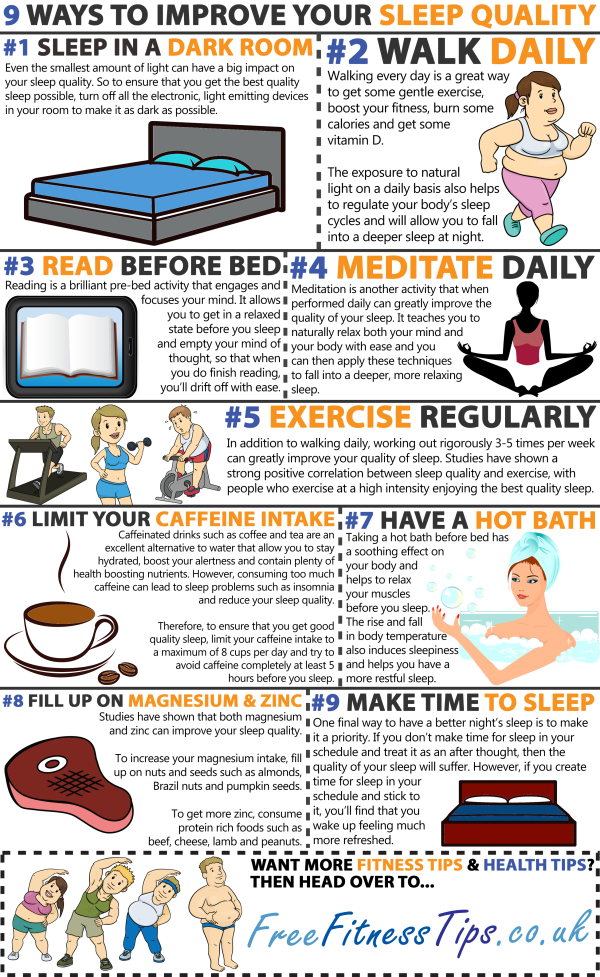

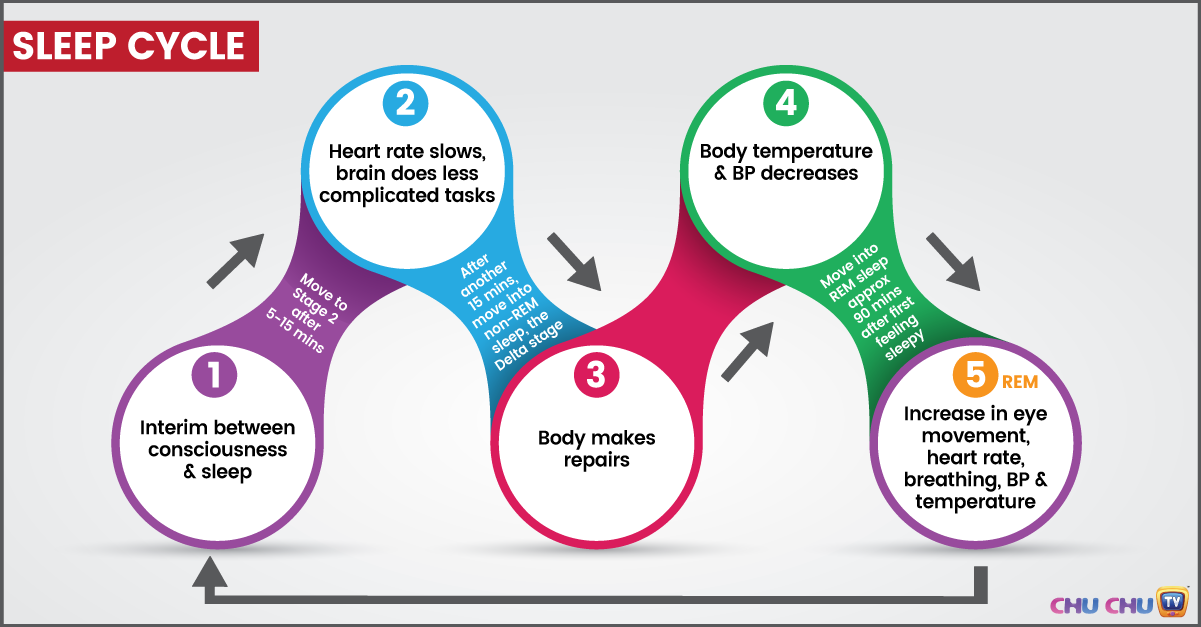

- Disturbances in sleep

- Fluctuations in weight, along with eating pattern changes

- Physical changes that are unexplained, including headache, constipation, diarrhea, chronic pain, and rumbling stomach

- Frequently provoked to anger

- Developing obsessive/compulsive behaviors

- Chronic fatigue, excessive tiredness, no energy

- Forgetfulness and memory problems

- Shying away from social activities

- No longer finding pleasure in sex

- Comments from others about your mood swings and erratic behavior

Junk Food Linked to Psychological Distress

Researchers at California’s Loma Linda University Adventist Health Sciences Center found that state adult residents consuming more unhealthy food were also likely to report psychological distress symptoms (either moderate or severe), compared to peers eating healthier diets. The study, published in the International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition, also found that nearly 17 percent of California adults are likely to suffer from mental illness, some 13.2 percent with moderate psychological distress and 3.7 percent with severe psychological distress. Researchers recommended targeted public health interventions promoting healthier diets aimed at young adults and those with less than 12 years of education.

The study, published in the International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition, also found that nearly 17 percent of California adults are likely to suffer from mental illness, some 13.2 percent with moderate psychological distress and 3.7 percent with severe psychological distress. Researchers recommended targeted public health interventions promoting healthier diets aimed at young adults and those with less than 12 years of education.

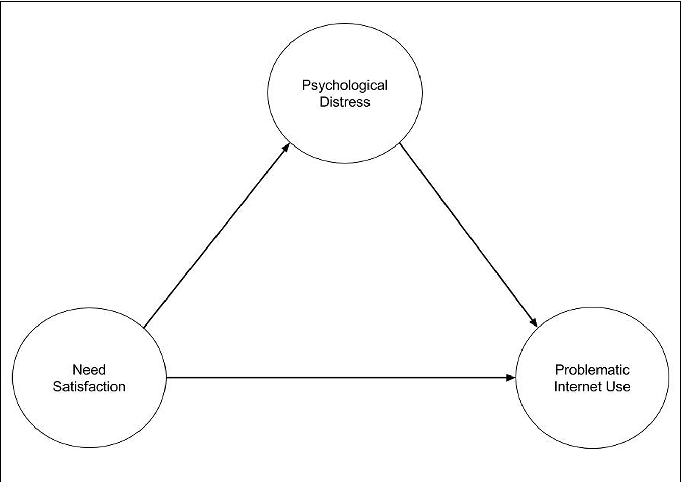

Goal Conflict and Psychological Distress Linked

A study conducted by the University of Exeter and Edith Cowan University found that personal goal conflict may increase feelings of anxiety and depression. They studied two forms of motivational conflict, inter-goal conflict (which occurs when pursuing a goal makes it difficult to pursue another goal), and ambivalence (when the individual has conflicting feelings about particular goals). Results of the study, published in Personality and Individual Differences, showed that each of these goal conflict forms were associated independently with depressive and anxious symptoms. Researchers said that those with poorer mental health are more likely to say their personal goals are in conflict with each other. Such goal conflicts can contribute to psychological distress.

Researchers said that those with poorer mental health are more likely to say their personal goals are in conflict with each other. Such goal conflicts can contribute to psychological distress.

An earlier meta-analysis by researchers from the University of California, Riverside, published in the Journal of Research in Personality, found that higher levels of goal conflict are negatively associated with psychological well-being (lower levels of positive psychological outcomes and greater levels of psychological distress).

How to Cope with Psychological Distress

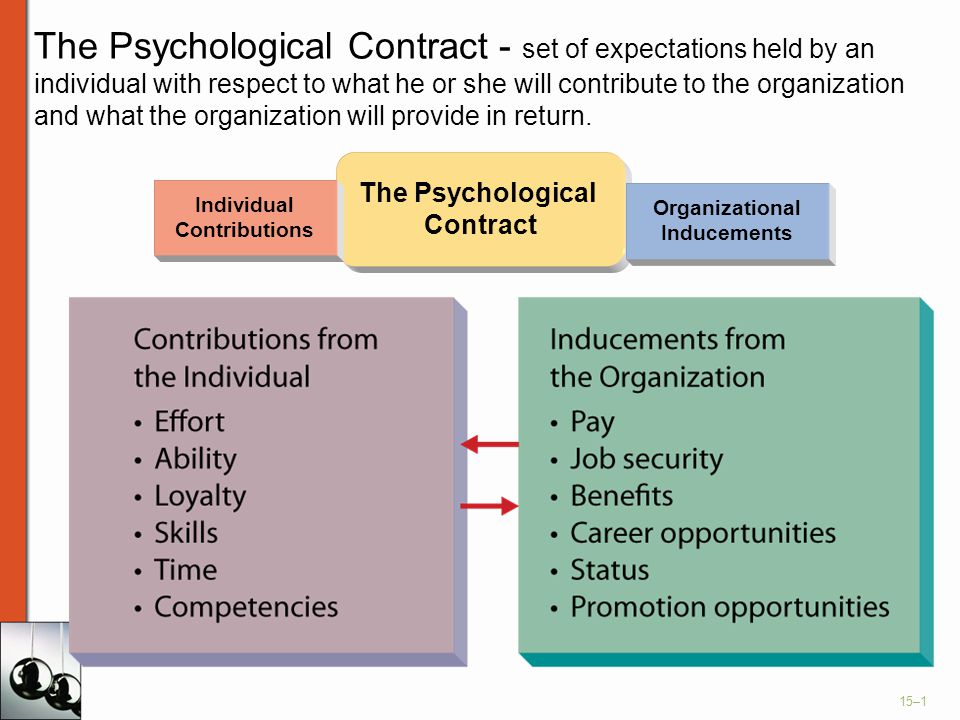

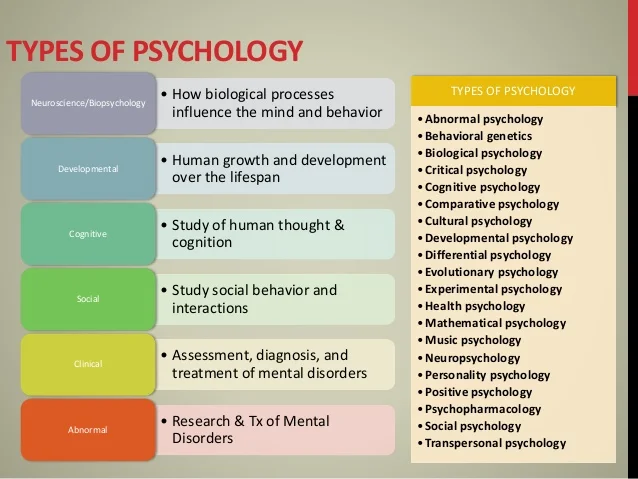

The first step in effective coping with psychological distress involves identifying the potential causes for the distress and then resolving to take steps to alleviate or overcome it. This may involve psychological counseling to get at the root cause for the psychological distress. As part of the counseling, the psychiatrist, psychologist or other mental health professional may recommend a number of different therapeutic approaches to help reduce psychological distress.

Getting out in nature – A 2019 study published in Health Place looked at the beneficial effects of greenness (green space) and serious psychological distress among adults and teens in California and found epidemiological evidence of such benefits in the study group’s mental health. While numerous other studies focused on adults and beneficial effects of green space, this population-based U.S. study aimed to fill in the gap with inclusion of teens.

Another 2019 study, published in the International Journal of Environmental Health Research, reported that even short-term time spent in an urban park contributed to improvement in subjective well-being. The effect was independent of levels of physical activity. Improvement was reported as stress reduction and recovery from mental fatigue. Researchers recommended a minimum of 20 minutes in the park to achieve benefits from being in the green space.

Try giving hugs – Researched published in PLOS One found that receiving hugs on days when subjects experienced interpersonal conflict helped attenuate the negative effects of the conflict on same-day and subsequent day. Researchers said their findings help contribute to an understanding of the role of interpersonal touch as a buffer against negative outcomes of interpersonal conflict and distress.

Researchers said their findings help contribute to an understanding of the role of interpersonal touch as a buffer against negative outcomes of interpersonal conflict and distress.

Identify what you need and focus on what you want – Psychological distress is no picnic and when you’re in the throes of it, you may be uncertain what to do next. Experts recommend healthy ways to deal with such distress that include, first and foremost, identifying what it is you need and then also focusing on what you want. You need to practice good self-care (being kind to yourself), engage in grounding, developing your nurturing self-voice and other proactive coping methods to help deal with psychological distress.

Dementia

dementia- Healthcare issues »

- A

- B

- B

- G

- D

- E

- and

- 9000 About

- P

- P

- With

- T

- in

- F

- x

- 9 h

- K.

- S

- B

- E

- S

- I

- Popular Topics

- Air pollution

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Hepatitis

- Data and statistics »

- News bulletin

- The facts are clear

- Publications

- Find country »

- A

- B

- C

- g

- D

- E

- and

- th

- K

- L

- 9000 H 9000

- in

- Ф

- x

- C hours

- Sh

- Sh.

- K

- E 9000 WHO in countries »

- Reporting

- Regions »

- Africa

- America

- Southeast Asia

- Europe

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Western Pacific

- Media Center

- Press releases

- Statements

- Media messages

- Comments

- Reporting

- Online Q&A

- Events

- Photo reports

- Questions and answers

- Update

- Emergencies "

- News "

- Disease Outbreak News

- WHO data »

- Dashboards »

- COVID-19 Monitoring Dashboard

- Basic moments "

- About WHO »

- CEO

- About WHO

- WHO activities

- Where does WHO work?

- Governing Bodies »

- World Health Assembly

- Executive committee

- Main page/

- Media Center /

- Newsletters/

- Read more/

- Dementia

Cathy Greenblat

© Photo

Dementia is a syndrome, usually chronic or progressive, in which there is a deterioration in cognitive function (ie the ability to think) to a greater extent than is expected with normal aging. There is a degradation of memory, thinking, understanding, speech and the ability to navigate, count, learn and reason. Dementia does not affect consciousness. Cognitive impairment is often accompanied, and sometimes preceded, by deterioration in emotional control, as well as degradation of social behavior or motivation.

There is a degradation of memory, thinking, understanding, speech and the ability to navigate, count, learn and reason. Dementia does not affect consciousness. Cognitive impairment is often accompanied, and sometimes preceded, by deterioration in emotional control, as well as degradation of social behavior or motivation.

Dementia is caused by a variety of illnesses and injuries that primarily or secondarily cause brain damage, such as Alzheimer's disease or stroke.

Dementia is one of the leading causes of disability and addiction among older people worldwide. It can have a profound impact not only on the people who suffer it, but also on their families and caregivers. There is often a lack of awareness and understanding about dementia, leading to stigma and barriers to diagnosis and care. The impact of dementia on caregivers, families and society as a whole can be physical, psychological, social and economic.

Signs and symptoms

Dementia affects people differently, depending on the impact of the disease and on the individual before the disease. The signs and symptoms associated with dementia go through three stages of development.

The signs and symptoms associated with dementia go through three stages of development.

Early stage: The early stage of dementia often goes unnoticed because it develops gradually. Common symptoms include:

- forgetfulness;

- loss of track of time;

- disorientation in a familiar area.

Intermediate: As dementia progresses to the intermediate stage, the signs and symptoms become more pronounced and increasingly narrowing. They include:

- forgetting about recent events and people's names;

- disorientation at home;

- increasing difficulties in communication;

- need for help with self-care;

- behavioral difficulties, including aimless walking and asking the same questions.

Late stage: In the late stage of dementia, almost complete dependence and inactivity develops. Memory impairment becomes significant, and physical signs and symptoms become more obvious. Symptoms include:

Symptoms include:

- disorientation in time and space;

- difficulty in recognizing relatives and friends;

- increasing need for help with self-care;

- difficulty in moving;

- behavioral changes that may be exacerbated and include aggressiveness.

Common forms of dementia

There are many forms of dementia. Alzheimer's disease is the most common form, accounting for 60-70% of all cases. Other common forms include vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia (abnormal protein inclusions that form inside nerve cells), and a group of diseases that contribute to frontotemporal dementia (degeneration of the frontal lobe of the brain). There are no clear boundaries between different forms of dementia, and mixed forms of dementia often coexist.

Dementia rates

There are about 50 million people with dementia worldwide, more than half, almost 60% of them, live in low- and middle-income countries. There are about 10 million new cases of the disease every year.

The proportion of the general population aged 60 and over with dementia at any point in time is estimated to be between 5% and 8%.

The total number of people with dementia is projected to be around 82 million in 2030 and 152 million by 2050. This growth will be driven in large part by an increase in the number of people with dementia in low- and middle-income countries.

Treatment and care

Currently there is no therapy to cure or change the course of dementia. Numerous new drugs are under investigation and are at various stages of clinical trials.

However, much can be done to support and improve the lives of people with dementia, their caregivers and their families. The main goals of medical care for dementia are:\n

- early diagnosis to ensure early and optimal management;

- optimization of physical health, cognitive abilities, activity and well-being;

- detection and treatment of associated physical illness;

- detection and treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms;

- provide information and long-term support for carers.

Risk factors and prevention

Although age is the most important known risk factor for dementia, it is not an inevitable consequence of aging. What’s more, dementia doesn’t just affect the elderly—early onset of dementia (defined as the onset of symptoms before the age of 65) accounts for up to 9% of all cases of dementia.

Research shows that the risk of dementia can be reduced by exercising regularly, not smoking, avoiding the harmful use of alcohol, controlling your weight, eating well, and maintaining normal blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar levels. Other risk factors include depression, low educational attainment, social isolation, and cognitive inactivity.

Social and economic impact

Dementia has a significant social and economic impact in terms of medical costs, social care costs and informal care. In 2015, total global public spending on dementia was estimated at US$818 billion, corresponding to 1.1% of the world's gross domestic product (GDP). Total spending as a share of GDP ranged from 0.2% in low-income countries to 1.4% in high-income countries.

Total spending as a share of GDP ranged from 0.2% in low-income countries to 1.4% in high-income countries.

Impact on families and caregivers

Dementia can have a profound impact on the families of affected people and those who care for them. The physical, emotional and financial burden can put a lot of stress on families and caregivers, and they need support from the health, social, financial and legal systems.

Human rights

People with dementia are often denied the basic rights and freedoms that other people have. In many countries, physical means and chemicals are widely used in nursing homes and intensive care facilities to retain patients, even though there are regulations in place to protect the human rights to freedom and choice.

Providing high-quality care for people with dementia and their caregivers requires appropriate and supportive legal and regulatory frameworks based on internationally recognized human rights standards.

WHO activities

WHO recognizes dementia as a public health priority. In May 2017, the World Health Assembly approved the Global Health Sector Action Plan for the Response to Dementia 2017-2025. The plan is a comprehensive program of action for policy makers, international, regional and national partners and WHO in the following areas:

In May 2017, the World Health Assembly approved the Global Health Sector Action Plan for the Response to Dementia 2017-2025. The plan is a comprehensive program of action for policy makers, international, regional and national partners and WHO in the following areas:

- taking action on dementia as a public health priority; raising awareness about dementia and creating supportive environment initiatives for people with dementia; reduced risk of developing dementia;

- reduced risk of dementia; diagnosis, treatment and care;

- dementia information systems; support for carers of people with dementia; and

- research and innovation.

An international monitoring platform, the Global Dementia Observatory, has been established for policy makers and researchers to facilitate monitoring and sharing of information on dementia policy, health care, epidemiology and research. WHO is also developing a knowledge-sharing platform to facilitate the sharing of best practices in the field of dementia.

WHO has developed a dementia action plan to assist Member States in the development and operationalization of dementia action plans. This guidance is closely linked to the WHO Global Observatory on Dementia and includes relevant methodologies, such as a checklist, to guide the preparation, development and implementation of action plans for dementia. In addition, this guide can be helpful in identifying stakeholders and setting priorities.

The WHO Guidelines for Reducing the Risk of Cognitive Impairment and Dementia provide evidence-based recommendations for interventions to reduce modifiable risk factors for dementia such as physical inactivity and unhealthy diets, and to manage medical conditions associated with dementia including hypertension and diabetes.

Dementia is also a priority condition under the Mental Health Gap Action Program (mhGAP), which is an important resource for general practitioners, especially in low- and middle-income countries, to use in providing health care first line for psychiatric and neurological problems and disorders caused by the use of psychoactive substances.

WHO has developed the iSupport program to provide caregivers of people with dementia with information and skills. The iSupport web tool is available as a printed manual and is already in use in a number of countries. An online version of "iSupport" will be available soon.

","datePublished":"2022-09-20T12:00:00.0000000+00:00","image":"https://cdn.who.int/media/images/default-source/imported/en -dementia_ce93dcb3-2920-4021-9af5-32cbbee9bf9f.jpg?sfvrsn=1a94c86c_3","publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"World Health Organization: WHO","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject"," url":"https://www.who.int/Images/SchemaOrg/schemaOrgLogo.jpg","width":250,"height":60}},"dateModified":"2022-09-20T12:00: 00.0000000+00:00","mainEntityOfPage":"https://www.who.int/ru/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia","@context":"http://schema.org ","@type":"Article"};

Key Facts

- Dementia is a syndrome in which memory, thinking, behavior and ability to perform daily activities deteriorate.

- Dementia mainly affects the elderly, but is not a normal condition of aging.

- There are about 50 million people with dementia worldwide, and almost 10 million new cases occur each year.

- Alzheimer's disease is the most common cause of dementia, accounting for 60-70% of all cases.

- Dementia is one of the leading causes of disability and addiction among older people worldwide.

- Dementia has a physical, psychological, social and economic impact not only on those affected, but also on their caregivers, families and society as a whole.

Dementia

Dementia is a syndrome, usually chronic or progressive, in which cognitive function (i.e. the ability to think) deteriorates to a greater extent than is expected with normal aging. There is a degradation of memory, thinking, understanding, speech and the ability to navigate, count, learn and reason. Dementia does not affect consciousness. Cognitive impairment is often accompanied, and sometimes preceded, by deterioration in emotional control, as well as degradation of social behavior or motivation.

Dementia is caused by a variety of illnesses and injuries that primarily or secondarily cause brain damage, such as Alzheimer's disease or stroke.

Dementia is one of the leading causes of disability and addiction among older people worldwide. It can have a profound impact not only on the people who suffer it, but also on their families and caregivers. There is often a lack of awareness and understanding about dementia, leading to stigma and barriers to diagnosis and care. The impact of dementia on caregivers, families and society as a whole can be physical, psychological, social and economic.

Signs and symptoms

Dementia affects people differently, depending on the impact of the disease and on the individual before the disease. The signs and symptoms associated with dementia go through three stages of development.

Early stage: The early stage of dementia often goes unnoticed because it develops gradually. Common symptoms include:

- forgetfulness;

- loss of track of time;

- disorientation in a familiar area.

Intermediate: As dementia progresses to the intermediate stage, the signs and symptoms become more pronounced and increasingly narrowing. They include:

- forgetting about recent events and people's names;

- disorientation at home;

- increasing difficulties in communication;

- need for help with self-care;

- behavioral difficulties, including aimless walking and asking the same questions.

Late stage: In the late stage of dementia, almost complete dependence and inactivity develops. Memory impairment becomes significant, and physical signs and symptoms become more obvious. Symptoms include:

- disorientation in time and space;

- difficulty in recognizing relatives and friends;

- increasing need for help with self-care;

- difficulty in moving;

- behavioral changes that may be exacerbated and include aggressiveness.

Common forms of dementia

There are many forms of dementia. Alzheimer's disease is the most common form, accounting for 60-70% of all cases. Other common forms include vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia (abnormal protein inclusions that form inside nerve cells), and a group of diseases that contribute to frontotemporal dementia (degeneration of the frontal lobe of the brain). There are no clear boundaries between different forms of dementia, and mixed forms of dementia often coexist.

Alzheimer's disease is the most common form, accounting for 60-70% of all cases. Other common forms include vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia (abnormal protein inclusions that form inside nerve cells), and a group of diseases that contribute to frontotemporal dementia (degeneration of the frontal lobe of the brain). There are no clear boundaries between different forms of dementia, and mixed forms of dementia often coexist.

Dementia rates

There are about 50 million people with dementia worldwide, more than half, almost 60% of them, live in low- and middle-income countries. There are about 10 million new cases of the disease every year.

The proportion of the general population aged 60 and over with dementia at any point in time is estimated to be between 5% and 8%.

The total number of people with dementia is projected to be around 82 million in 2030 and 152 million by 2050. This growth will be driven in large part by an increase in the number of people with dementia in low- and middle-income countries.

Treatment and care

Currently there is no therapy to cure or change the course of dementia. Numerous new drugs are under investigation and are at various stages of clinical trials.

However, much can be done to support and improve the lives of people with dementia, their caregivers and their families. The main goals of medical care for dementia are:

- early diagnosis to ensure early and optimal management;

- optimization of physical health, cognitive abilities, activity and well-being;

- detection and treatment of associated physical illness;

- detection and treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms;

- provide information and long-term support for carers.

Risk factors and prevention

Although age is the most important known risk factor for dementia, it is not an inevitable consequence of aging. What’s more, dementia doesn’t just affect the elderly—early onset of dementia (defined as the onset of symptoms before the age of 65) accounts for up to 9% of all cases of dementia.

Research shows that the risk of dementia can be reduced by exercising regularly, not smoking, avoiding the harmful use of alcohol, controlling your weight, eating well, and maintaining normal blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar levels. Other risk factors include depression, low educational attainment, social isolation, and cognitive inactivity.

Social and economic impact

Dementia has a significant social and economic impact in terms of medical costs, social care costs and informal care. In 2015, total global public spending on dementia was estimated at US$818 billion, corresponding to 1.1% of the world's gross domestic product (GDP). Total spending as a share of GDP ranged from 0.2% in low-income countries to 1.4% in high-income countries.

Impact on families and caregivers

Dementia can have a profound impact on the families of affected people and those who care for them. The physical, emotional and financial burden can put a lot of stress on families and caregivers, and they need support from the health, social, financial and legal systems.

Human rights

People with dementia are often denied the basic rights and freedoms that other people have. In many countries, physical means and chemicals are widely used in nursing homes and intensive care facilities to retain patients, even though there are regulations in place to protect the human rights to freedom and choice.

Providing high-quality care for people with dementia and their caregivers requires appropriate and supportive legal and regulatory frameworks based on internationally recognized human rights standards.

WHO activities

WHO recognizes dementia as a public health priority. In May 2017, the World Health Assembly approved the Global Health Sector Action Plan for the Response to Dementia 2017-2025. The plan is a comprehensive program of action for policy makers, international, regional and national partners and WHO in the following areas:

- taking action on dementia as a public health priority; raising awareness about dementia and creating supportive environment initiatives for people with dementia; reduced risk of developing dementia;

- reduced risk of dementia; diagnosis, treatment and care;

- dementia information systems; support for carers of people with dementia; and

- research and innovation.

An international monitoring platform, the Global Dementia Observatory, has been established for policy makers and researchers to facilitate monitoring and sharing of information on dementia policy, health care, epidemiology and research. WHO is also developing a knowledge-sharing platform to facilitate the sharing of best practices in the field of dementia.

WHO has developed a dementia action plan to assist Member States in the development and operationalization of dementia action plans. This guidance is closely linked to the WHO Global Observatory on Dementia and includes relevant methodologies, such as a checklist, to guide the preparation, development and implementation of action plans for dementia. In addition, this guide can be helpful in identifying stakeholders and setting priorities.

The WHO Guidelines for Reducing the Risk of Cognitive Impairment and Dementia provide evidence-based recommendations for interventions to reduce modifiable risk factors for dementia such as physical inactivity and unhealthy diets, and to manage medical conditions associated with dementia including hypertension and diabetes.

Dementia is also a priority condition under the Mental Health Gap Action Program (mhGAP), which is an important resource for general practitioners, especially in low- and middle-income countries, to use in providing health care first line for psychiatric and neurological problems and disorders caused by the use of psychoactive substances.

WHO has developed the iSupport program to provide caregivers of people with dementia with information and skills. The iSupport web tool is available as a printed manual and is already in use in a number of countries. An online version of "iSupport" will be available soon.

Autism

Autism- Health »

- A

- B

- C

- D

- D

- E

- С

- and

- K

- L

- m

- 9000

- x

- C hours

- Sh

- Sh

- K

- 9

- E 9000 Popular Topics

- Air pollution

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Hepatitis

- Data and statistics »

- News bulletin

- The facts are clear

- Publications

- Find the country »

- A

- B

- B

- G

- D

- E

- and

- L

- O

- P

- R

- C

- T

- U

- Ф

- x

-

- 9000 E

- Yu

- I

004 H

- WHO in countries »

- Reporting

- Regions »

- Africa

- America

- Southeast Asia

- Europe

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Western Pacific

- Media Center

- Press releases

- Statements

- Media messages

- Comments

- Reporting

- Online Q&A

- Events

- Photo reports

- Questions and answers

- Update

- Emergencies "

- News "

- Disease Outbreak News

- WHO data »

- Dashboards »

- COVID-19 Monitoring Dashboard

- Basic moments "

- About WHO »

- CEO

- About WHO

- WHO activities

- Where does WHO work?

- Governing Bodies »

- World Health Assembly

- Executive committee

- Main page/

- Media Center /

- Newsletters/

- Read more/

- Autism

Key Facts

- Autism, also called autism spectrum disorder, is a diverse group of pathological conditions caused by the development of the brain.

- Signs of autism can be detected in early childhood, but it is often not diagnosed until later in life.

- Approximately 1 in 100 children have autism.

- The abilities and needs of people with autism can vary and change over time. Some people with autism are able to lead independent and productive lives, while others become severely disabled and require lifelong care and support.

- Evidence-based psychosocial interventions improve communication skills and social behavior, which positively affects the well-being and quality of life of people with autism and their caregivers.

- Care for people with autism must be accompanied by local and community action to make physical and social environments and relationships more accessible, inclusive and supportive.

Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) are a group of different conditions. All of them are characterized by certain difficulties with social interaction and communication. Other features include atypical patterns of action and behaviors, such as difficulty moving from one activity to another, focus on details, and unusual responses to external stimuli.

All of them are characterized by certain difficulties with social interaction and communication. Other features include atypical patterns of action and behaviors, such as difficulty moving from one activity to another, focus on details, and unusual responses to external stimuli.

The abilities and needs of people with autism can vary and change over time. Some people with autism are able to live independent and productive lives, while others become severely disabled and require lifelong care and support. Autism often negatively affects educational or employment opportunities. In addition, for family members of people with autism, care and support responsibilities can often be a source of significant stress. Community attitudes and the level of support from local and national governments are important determinants of the quality of life of people with autism.

Signs of autism can be identified in early childhood, but the condition is often diagnosed at much later stages.

People with autism often have comorbid conditions and illnesses, including epilepsy, depression, anxiety, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, as well as behavioral problems such as sleep disturbances or self-harm. The level of intellectual abilities of people with autism varies in a wide range from severe cognitive impairment to a high level of intelligence.

Epidemiology

It is estimated that autism affects about 1 in 100 children worldwide (1). At the same time, we are talking about an average indicator, and the prevalence rates of autism recorded according to different studies vary widely. Nevertheless, according to some reputable controlled studies, the real numbers are much higher. The prevalence of autism in many low- and middle-income countries is unknown.

Causes

Available scientific evidence indicates many factors that may increase the likelihood of children developing autism, including environmental and genetic factors.

Available epidemiological data do not establish a causal relationship between autism and measles, mumps and rubella vaccination. Past studies suggesting such a causal relationship have been many methodological problems were found (2), (3).

Similarly, there is no evidence that any childhood vaccine can increase the risk of developing autism. Evidence reviews on a potential association between the preservative thiomersal and aluminum adjuvants contained in inactivated vaccines and the risk of developing autism strongly suggest that vaccines do not lead to an increase in this risk.

Needs assessment and care management

A range of interventions, from early childhood and throughout life, can contribute to the optimal development, well-being and quality of life of people with autism. Timely evidence-based psychosocial interventions at an early age can improve the ability of children with autism to communicate and interact effectively with others. It is recommended to monitor the development of children as part of the planned provision of medical care to mothers and children.

It is recommended to monitor the development of children as part of the planned provision of medical care to mothers and children.

It is important that, once diagnosed, children, adolescents and adults diagnosed with autism and their caregivers have access to relevant information, referrals and practical support tailored to their individual needs. constantly changing needs and preferences.

The health care needs of people with autism are complex, requiring them to provide comprehensive services, including health promotion, care and rehabilitation services. Therefore, it is important to ensure cooperation with other sectors, in particular with the education system, employment and the social sector.

Interventions to help people with autism and other developmental disabilities should be planned and implemented with the participation of people with these conditions themselves. Caring for people with autism should be accompanied by local action. and at the level of society as a whole, in order to make the physical and social environment and relationships more accessible, inclusive and supportive.

Human rights

All people, including those with autism, have the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.

Yet people with autism often face stigma and discrimination: their health care and education rights are unfairly denied, and their opportunities to participate in society are limited.

People with autism may experience the same health problems as the rest of the population. In addition, they may have special health care needs related to autism and other related conditions. They can be are more vulnerable to chronic noncommunicable diseases associated with behavioral risk factors such as physical inactivity and poor diet, and are at greater risk of violence, injury and abuse.

People with autism, like the rest of the population, need affordable health services to meet their general health needs, including health promotion and prevention services, as well as acute and chronic disease management. However less than in the general population, the level of satisfaction of the medical needs of people with autism is at a lower level. These people are also more vulnerable in humanitarian emergencies. One of the common barriers is the insufficient level of knowledge and understanding of the specifics of autism by medical professionals.

However less than in the general population, the level of satisfaction of the medical needs of people with autism is at a lower level. These people are also more vulnerable in humanitarian emergencies. One of the common barriers is the insufficient level of knowledge and understanding of the specifics of autism by medical professionals.

WHO Resolution on Autism Spectrum Disorders

In May 2014, the Sixty-seventh World Health Assembly adopted a resolution on "Comprehensive and concerted efforts for the management of autism spectrum disorders", supported by over 60 countries.

The resolution calls on WHO to work with Member States and partner agencies to strengthen national capacity to address ASD and other developmental disabilities.

WHO activities

WHO and partners recognize the need to strengthen countries' capacity to promote the optimal health and well-being of all people with autism.

The main activities of WHO in this regard are:

- promoting the adoption of targeted measures by national governments to improve the quality of life of people with autism;

- develop recommendations for policies and action plans to address autism in the broader context of physical, mental, brain health and care for people with disabilities;

- help to empower healthcare professionals to provide appropriate and effective care for people with autism and achieve optimal health and well-being; and

- promote and support an inclusive and supportive environment for people with autism and other developmental disabilities.

WHO comprehensive mental health action plan 2013–2030 and World Health Assembly Resolution WHA73.10 "Global action against epilepsy and other neurological disorders" contain calling on countries to address significant gaps in the early detection, care, treatment and rehabilitation of people with mental and neurodevelopmental disorders, including and autism. The resolution also calls on countries to take action to meet the social, economic, educational and other needs of people living with mental and neurological disorders and their families, and to develop surveillance and related research activities.

References

(1) Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Zeidan J et al. Autism Research 2022 March.

(2) Wakefield's affair: 12 years of uncertainty whereas no link between autism and MMR vaccine has been proven. Maisonneuve H, Floret D. Presse Med. 2012 Sep; French https://pubmed.

Learn more