Adhd sleep cycle

ADHD and Sleep Problems: Why You're Always Tired

ADHD and Sleep Problems

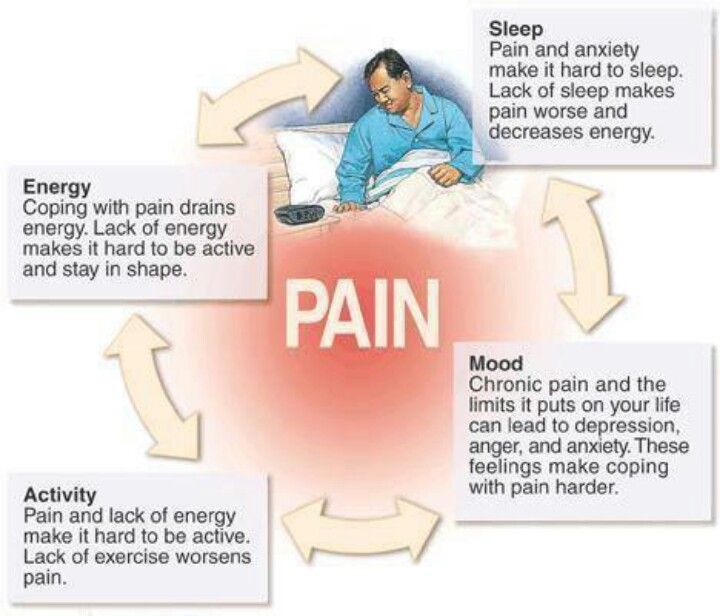

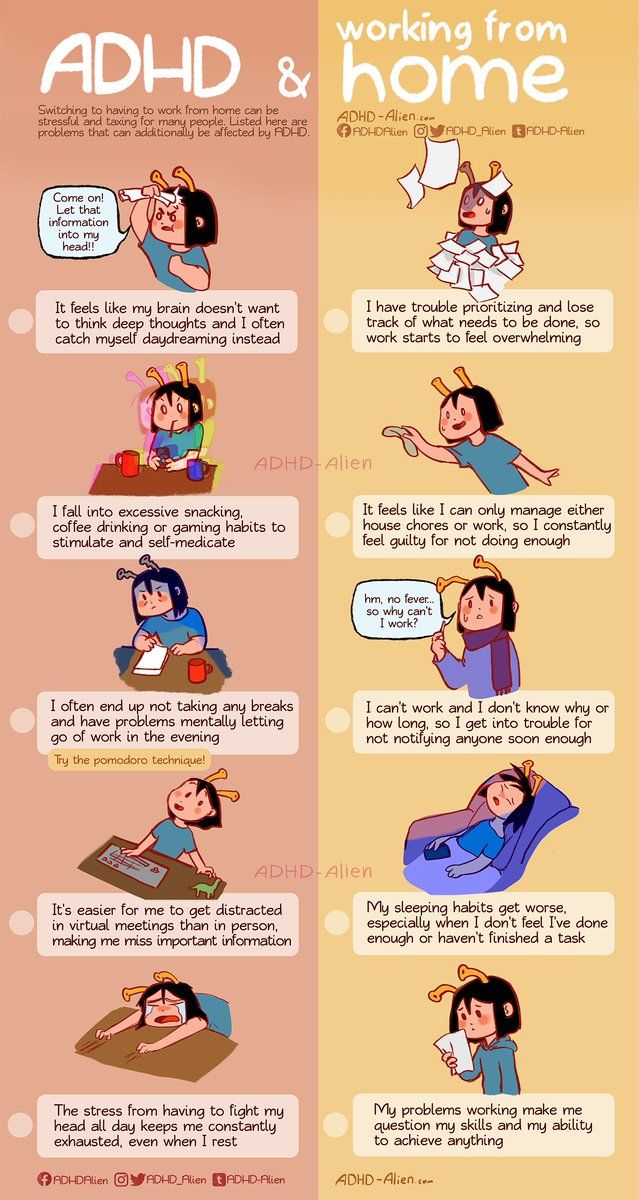

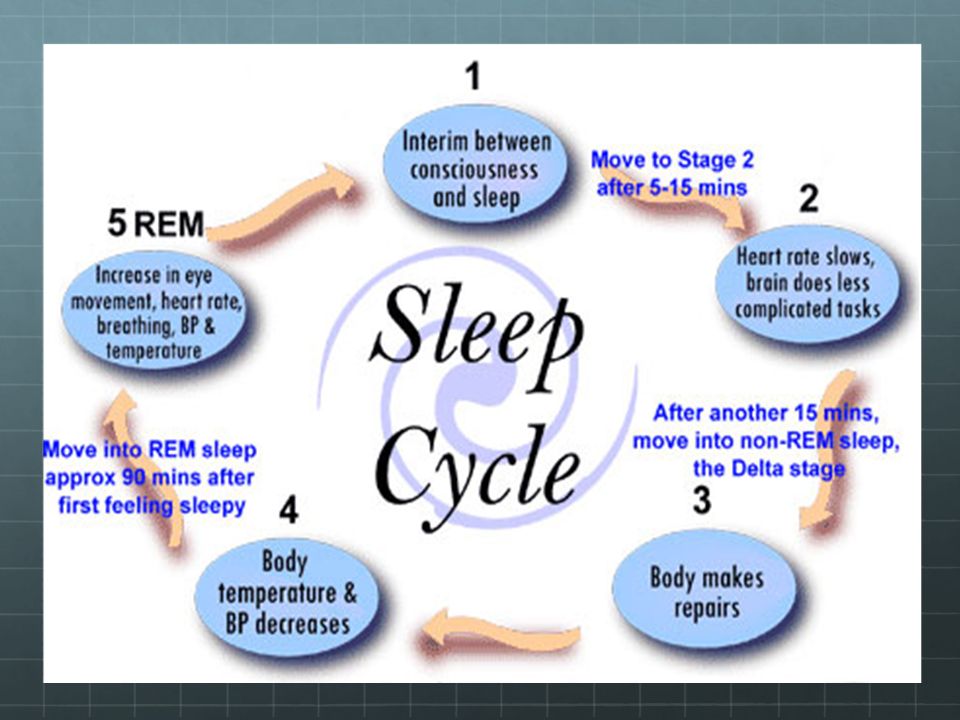

Adults with ADHD rarely fall asleep easily, sleep soundly through the night, and then wake up feeling refreshed. More often, ADHD’s mental and physical restlessness disturbs a person’s sleep patterns — and the ensuing exhaustion hurts overall health and treatment. This is widely accepted as true. But, as with most of our knowledge about ADHD in adults, we’re only beginning to understand the stronger link between ADHD and sleep, that creates difficulties:

- Falling asleep

- Staying asleep

- Waking up

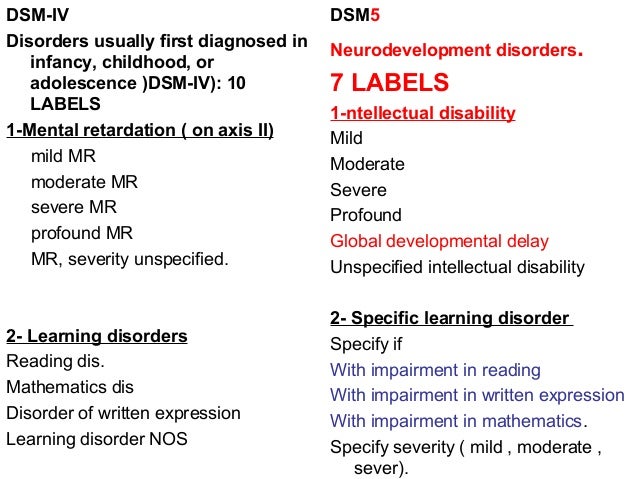

Sleep disturbances caused by ADHD have been overlooked for a number of reasons. Sleep problems did not fit neatly into the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

(DSM) requirement that all ADHD symptoms must be present by age 7. Sleep disturbances associated with ADHD generally appear later in life, at around age 12, on average. Consequently, the arbitrary age cutoff has prevented recognition of night owls and sleep disturbances in ADHD until recently, when studies of adults have become more common. Just as ADHD does not go away at adolescence, it does not go away at night either. It continues to impair life functioning 24 hours a day.

In early attempts to define the syndrome, sleep disturbances were briefly considered a criterion for ADHD, but were dropped from the symptoms list because evidence of them was thought to be too nonspecific. As research has expanded to include adults with ADHD, the causes and effects of sleeping disturbances have become clearer.

For now, sleeping problems tend either to be overlooked or to be viewed as coexisting problems with an unclear relationship to ADHD itself and to the mental fatigue so commonly reported by individuals with ADHD. Sleep disturbances have been incorrectly attributed to the stimulant-class medications that are often the first to be used to treat ADHD.

The Four Big ADHD Sleep Problems

No scientific literature on sleep lists ADHD as a prominent cause of sleep disturbances. Most articles focus on sleep disturbance due to stimulant-class medications, rather than looking at ADHD as the cause. Yet adults with ADHD know that the connection between their condition and sleep problems is real. Sufferers often call it “perverse sleep” — when they want to be asleep, they are awake; when they want to be awake, they are asleep.

[Watch This Video: 5 Fixes for “I Can’t Sleep”]

The four most common sleep disturbances associated with ADHD are:1. Difficulty Falling Asleep with ADHD

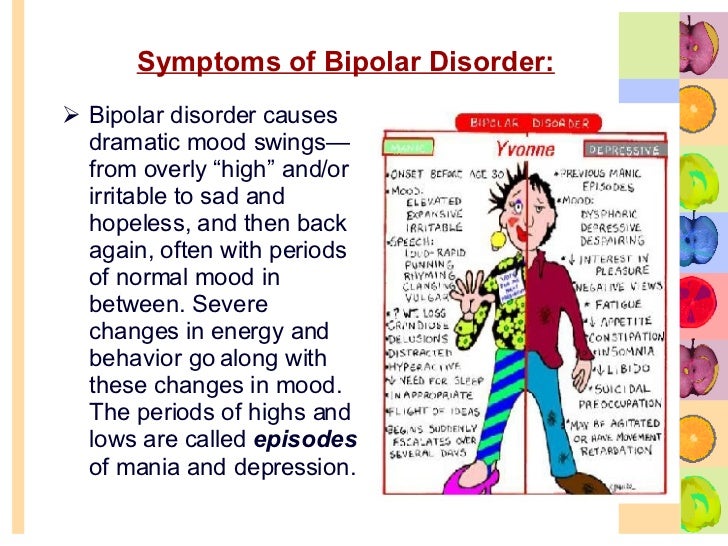

About three-fourths of all adults with ADHD report inability to “shut off my mind so I can fall asleep at night.” Many describe themselves as “night owls” who get a burst of energy when the sun goes down. Others report that they feel tired throughout the day, but as soon as the head hits the pillow, the mind clicks on. Their thoughts jump or bounce from one worry to another. Unfortunately, many of these adults describe their thoughts as “racing,” prompting a misdiagnosis of a mood disorder, when this is nothing more than the mental restlessness of ADHD.

Their thoughts jump or bounce from one worry to another. Unfortunately, many of these adults describe their thoughts as “racing,” prompting a misdiagnosis of a mood disorder, when this is nothing more than the mental restlessness of ADHD.

Prior to puberty, 10 to 15 percent of children with ADHD have trouble getting to sleep. This is twice the rate found in children and adolescents who do not have ADHD. This number dramatically increases with age: 50 percent of children with ADHD have difficulty falling asleep almost every night by age 12 ½ by age 30, more than 70 percent of adults with ADHD report that they spend more than one hour trying to fall asleep at night.

2. Restless Sleep with ADHD

When individuals with ADHD finally fall asleep, their sleep is restless. They toss and turn. They awaken at any noise in the house. They are so fitful that bed partners often choose to sleep in another bed. They often awake to find the bed torn apart and covers kicked onto the floor. Sleep is not refreshing and they awaken as tired as when they went to bed.

Sleep is not refreshing and they awaken as tired as when they went to bed.

[How Sleep Deprivation Looks a Lot Like ADHD]

3. Difficulty Waking Up with ADHD

More than 80 percent of adults with ADHD in my practice report multiple awakenings until about 4 a.m. Then they fall into “the sleep of the dead,” from which they have extreme difficulty rousing themselves.

They sleep through two or three alarms, as well as the attempts of family members to get them out of bed. ADHD sleepers are commonly irritable, even combative, when roused before they are ready. Many of them say they are not fully alert until noon.

4. Intrusive Sleep with ADHD

Paul Wender, M.D., a 30-year veteran ADHD researcher, relates ADHD to interest-based performance. As long as persons with ADHD were interested in or challenged by what they were doing, they did not demonstrate symptoms of the disorder. (This phenomenon is called hyperfocus by some, and is often considered to be an ADHD pattern. ) If, on the other hand, an individual with ADHD loses interest in an activity, his nervous system disengages, in search of something more interesting. Sometimes this disengagement is so abrupt as to induce sudden extreme drowsiness, even to the point of falling asleep.

) If, on the other hand, an individual with ADHD loses interest in an activity, his nervous system disengages, in search of something more interesting. Sometimes this disengagement is so abrupt as to induce sudden extreme drowsiness, even to the point of falling asleep.

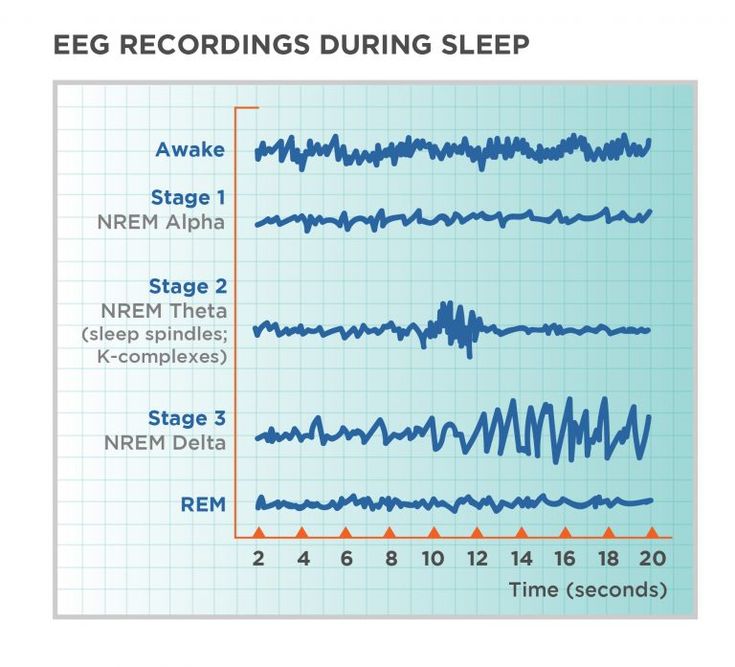

Marian Sigurdson, Ph.D., an expert on electroencephalography (EEG) findings in ADHD, reports that brain wave tracings at this time show a sudden intrusion of theta waves into the alpha and beta rhythms of alertness. We all have seen “theta wave intrusion,” in the student in the back of the classroom who suddenly crashes to the floor, having “fallen asleep.” This was probably someone with ADHD who was losing consciousness due to boredom rather than falling asleep. This syndrome is life-threatening if it occurs while driving, and it is often induced by long-distance driving on straight, monotonous roads. Often this condition is misdiagnosed as “EEG negative narcolepsy.” The extent of incidence of intrusive “sleep” is not known, because it occurs only under certain conditions that are hard to reproduce in a laboratory.

Why Do People with ADHD Have Problems Sleeping?

There are several theories about the causes of sleep disturbance in people with ADHD, with a telling range of viewpoints. Physicians base their responses to their patients’ complaints of sleep problems on how they interpret the cause of the disturbances. A physician who looks first for disturbances resulting from disorganized life patterns will treat problems in a different way than a physician who thinks of them as a manifestation of ADHD.

Thomas Brown, Ph.D., longtime researcher in ADHD and developer of the Brown Scales, was one of the first to give serious attention to the problem of sleep in children and adolescents with ADHD. He sees sleep disturbances as indicative of problems of arousal and alertness in ADHD itself. Two of the five symptom clusters that emerge from the Brown Scales involve activation and arousal:

- Organizing and activating to begin work activities.

- Sustaining alertness, energy, and effort.

Brown views problems with sleep as a developmentally-based impairment of management functions of the brain — particularly, an impairment of the ability to sustain and regulate arousal and alertness. Interestingly, he does not recommend treatments common to ADHD, but rather recommends a two-pronged approach that stresses better sleep hygiene and the suppression of unwanted and inconvenient arousal states by using medications with sedative properties.

The simplest explanation is that sleep disturbances are direct manifestations of ADHD itself. True hyperactivity is extremely rare in women of any age. Most women experience the mental and physical restlessness of ADHD only when they are trying to shut down the arousal state of day-to-day functioning in order to fall asleep. At least 75 percent of adults of both genders report that their minds restlessly move from one concern to another for several hours until they finally fall asleep. Even then, they toss and turn, awaken frequently, and sometimes barely sleep at all.

The fact that 80 percent of adults with ADHD eventually fall into “the sleep of the dead” has led researchers to look for explanations. No single theory explains the severe impairment of the ability to rouse oneself into wakefulness. Some patients with ADHD report that they sleep well when they go camping or are out of doors for extended periods of time.

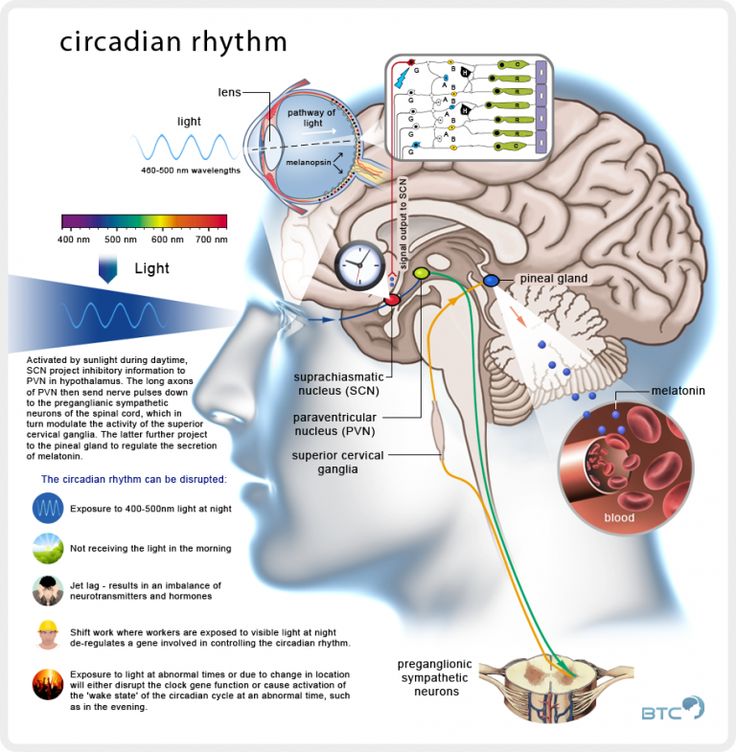

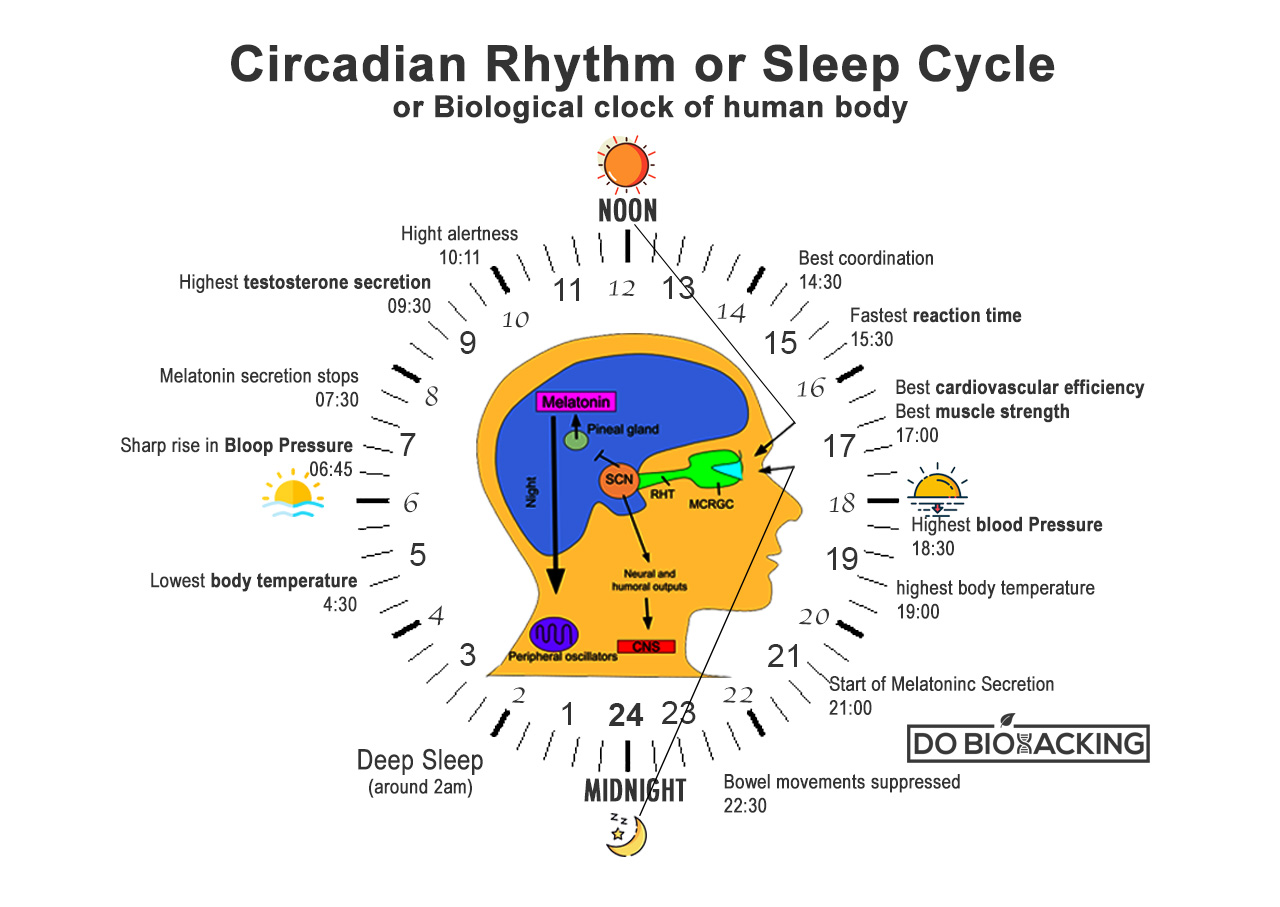

One hypothesis is that the lack of an accurate circadian clock may also account for the difficulty that many with ADHD have in judging the passage of time. Their internal clocks are not “set.” Consequently, they experience only two times: “now” and “not now.” Many of my adult patients do not wear watches. They experience time as an abstract concept, important to other people, but one which they don’t understand. It will take many more studies to establish the links between circadian rhythms and ADHD.

[Read This Next: Tired of Feeling Tired? How to Solve Common Sleep Problems]

How to Get to Sleep with ADD

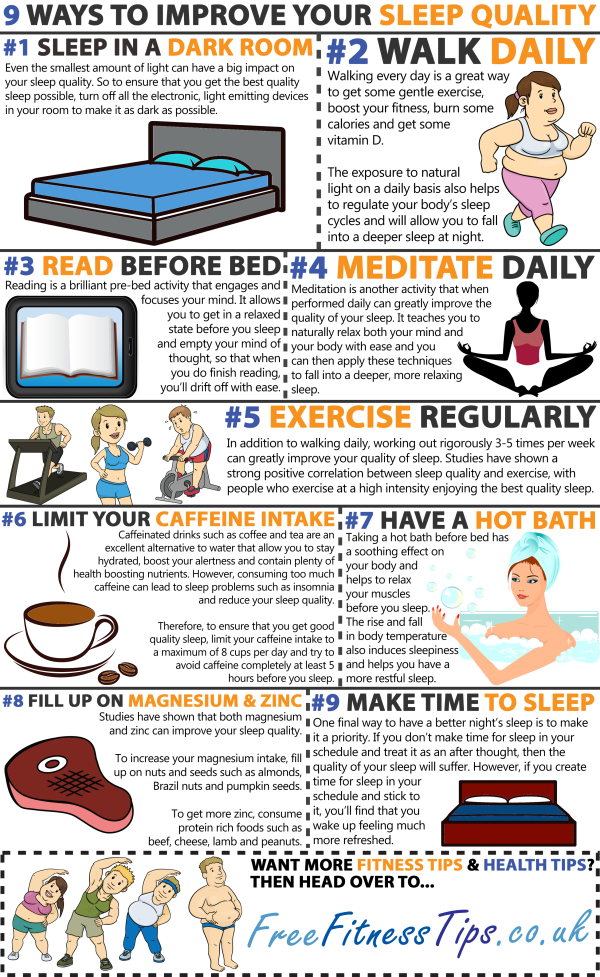

No matter how a doctor explains sleep problems, the remedy usually involves something called “sleep hygiene,” which considers all the things that foster the initiation and maintenance of sleep. This set of conditions is highly individualized. Some people need absolute silence. Others need white noise, such as a fan or radio, to mask disturbances to sleep. Some people need a snack before bed, while others can’t eat anything right before bedtime. A few rules of sleep hygiene are universal:

This set of conditions is highly individualized. Some people need absolute silence. Others need white noise, such as a fan or radio, to mask disturbances to sleep. Some people need a snack before bed, while others can’t eat anything right before bedtime. A few rules of sleep hygiene are universal:

- Use the bed only for sleep or sex, not as a place to confront problems or argue.

- Have a set bedtime and a bedtime routine and stick to it — rigorously.

- Avoid naps during the day.

Two more elements of good sleep hygiene seem obvious, but they should be stressed for people with ADHD.

- Get in bed to go to sleep. Many people with ADHD are at their best at night. They are most energetic, thinking clearest, and most stable after the sun goes down. The house is quiet and distractions are low. This is their most productive time. Unfortunately, they have jobs and families to which they must attend the next morning, tasks made harder by inadequate sleep.

- Avoid caffeine late at night. Caffeine can cause a racing ADHD brain to grow more excitable and alert. Caffeine is also a diuretic, although not as potent as experts once thought, and may cause sleep disruptions brought on by needing to go to the bathroom. It is a good strategy to avoid consuming any liquids shortly before bedtime.

Treatment Options for ADHD-Related Sleep Problems

If the patient spends hours a night with thoughts bouncing and his body tossing, this is probably a manifestation of ADHD. The best treatment is a dose of stimulant-class medication 45 minutes before bedtime. This course of action, however, is a hard sell to patients who suffer from difficulty sleeping. Consequently, once they have determined their optimal dose of medication, I ask them to take a nap an hour after they have taken the second dose.

Generally, they find that the medication’s “paradoxical effect” of calming restlessness is sufficient to allow them to fall asleep. Most adults are so sleep-deprived that a nap is usually successful. Once people see for themselves, in a “no-risk” situation, that the medications can help them shut off their brains and bodies and fall asleep, they are more willing to try medications at bedtime. About two-thirds of my adult patients take a full dose of their ADHD medication every night to fall asleep.

Most adults are so sleep-deprived that a nap is usually successful. Once people see for themselves, in a “no-risk” situation, that the medications can help them shut off their brains and bodies and fall asleep, they are more willing to try medications at bedtime. About two-thirds of my adult patients take a full dose of their ADHD medication every night to fall asleep.

What if the reverse clinical history is present? One-fourth of people with ADHD either don’t have a sleep disturbance or have ordinary difficulty falling asleep. Stimulant-class medications at bedtime are not helpful to them. Dr. Brown recommends Benadryl, 25 to 50 mg, about one hour before bed. Benadryl is an antihistamine sold without prescription and is not habit-forming. The downside is that it is long-acting, and can cause sleepiness for up to 60 hours in some individuals. About 10 percent of those with ADHD experience severe paradoxical agitation with Benadryl and never try it again.

Experts point out that sleep disturbances in people diagnosed with ADHD are not always due to ADHD-related causes. Sometimes patients have a co-morbid sleep disorder in addition to ADHD. Some professionals will order a sleep study for their patients to determine the cause of the sleep disturbance. Such tests as a Home Sleeping Test, Polysomnogram, or a Multiple Sleep Latency Test may be prescribed. If there are secondary sleep problems, doctors may use additional treatment options to manage sleep time challenges.

Sometimes patients have a co-morbid sleep disorder in addition to ADHD. Some professionals will order a sleep study for their patients to determine the cause of the sleep disturbance. Such tests as a Home Sleeping Test, Polysomnogram, or a Multiple Sleep Latency Test may be prescribed. If there are secondary sleep problems, doctors may use additional treatment options to manage sleep time challenges.

The next step up the treatment ladder is prescription medications. Most clinicians avoid sleeping pills because they are potentially habit-forming. People quickly develop tolerance to them and require ever-increasing doses. So, the next drugs of choice tend to be non-habit-forming, with significant sedation as a side effect. They are:

- Melatonin. This naturally occurring peptide released by the brain in response to the setting of the sun has some function in setting the circadian clock. It is available without prescription at most pharmacies and health food stores.

Typically the dosage sizes sold are too large. Almost all of the published research on Melatonin is on doses of 1 mg or less, but the doses available on the shelves are either 3 or 6 mg. Nothing is gained by using doses greater than one milligram. Melatonin may not be effective the first night, so several nights’ use may be necessary for effectiveness.

Typically the dosage sizes sold are too large. Almost all of the published research on Melatonin is on doses of 1 mg or less, but the doses available on the shelves are either 3 or 6 mg. Nothing is gained by using doses greater than one milligram. Melatonin may not be effective the first night, so several nights’ use may be necessary for effectiveness. - Periactin. The prescription antihistamine, cyproheptadine (Periactin), works like Benadryl but has the added advantages of suppressing dreams and reversing stimulant-induced appetite suppression.

- Clonidine. Some practitioners recommend in a 0.05 to 0.1 mg dose one hour before bedtime. This medication is used for high blood pressure, and it is the drug of choice for the hyperactivity component of ADHD. It exerts significant sedative effects for about four hours.

- Antidepressant medications, such as trazodone (Desyrel), 50 to 100 mg, or mirtazapine (Remeron), 15 mg, used by some clinicians for their sedative side effects.

Due to a complex mechanism of action, lower doses of mirtazapine are more sedative than higher ones. More is not better. Like Benadryl, these medications tend to produce sedation into the next day, and may make getting up the next morning harder than it was.

Due to a complex mechanism of action, lower doses of mirtazapine are more sedative than higher ones. More is not better. Like Benadryl, these medications tend to produce sedation into the next day, and may make getting up the next morning harder than it was.

Problems Waking Up with ADHD

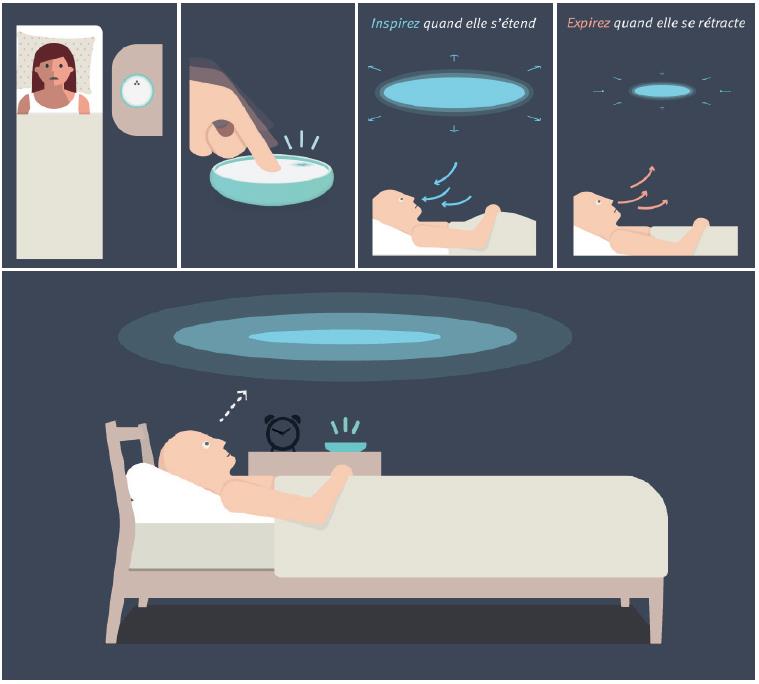

Problems in waking and feeling fully alert can be approached in two ways. The simpler is a two-alarm system. The patient sets a first dose of stimulant-class medication and a glass of water by the bedside. An alarm is set to go off one hour before the person actually plans to rise. When the alarm rings, the patient rouses himself enough to take the medication and goes back to sleep. When a second alarm goes off, an hour later, the medication is approaching peak blood level, giving the individual a fighting chance to get out of bed and start his day.

A second approach is more high-tech, based on evidence that difficulty waking in the morning is a circadian rhythm problem. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the use of sunset/sunrise-simulating lights can set the internal clocks of people with Delayed Sleep Phase Syndrome. As an added benefit, many people report that they sharpen their sense of time and time management once their internal clock is set properly. The lights, however, are experimental and expensive (about $400).

As an added benefit, many people report that they sharpen their sense of time and time management once their internal clock is set properly. The lights, however, are experimental and expensive (about $400).

Disturbances of sleep in people with ADHD are common, but are almost completely ignored by our current diagnostic system and in ADHD research. These patterns become progressively worse with age. Recognition of sleep disturbance in ADHD has been hampered by the misattribution of the difficulty falling asleep to the effects of stimulant-class medications. We now recognize that sleep difficulties are associated with ADHD itself, and that stimulant-class medications are often the best treatment of sleep problems rather than the cause of them.

[ADHD Directory: Find an ADHD Specialist or Clinic Near You]

William Dodson, M.D., is a member of ADDitude’s ADHD Medical Review Panel.

Previous Article Next Article

Delayed Circadian Rhythm Phase: A Cause of Late-Onset ADHD among Adolescents?

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

- PMC6487490

J Child Psychol Psychiatry. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2019 Dec 1.

Author manuscript; available in PMC 2019 Dec 1.

Published in final edited form as:

J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018 Dec; 59(12): 1248–1251.

Published online 2018 Sep 3. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12956

PMCID: PMC6487490

NIHMSID: NIHMS1021756

PMID: 30176050

, Ph.D.1,* and , Ph.D.1

Author information Copyright and License information Disclaimer

Late-onset attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has been a topic of significant debate within our field. One question focuses on whether there may be alternative explanations for the onset of inattentive and/or hyperactive symptoms in adolescence. Adolescence is a developmental period associated with a normative circadian rhythm phase delay, and there is significant overlap in the behavioral and cognitive manifestations and genetic underpinnings of ADHD and circadian misalignment. Delayed circadian rhythm phase is also common among individuals with traditionally-diagnosed ADHD, and exposure to bright light may be protective against ADHD, a process potentially mediated by improved circadian timing. In addition, daytime sleepiness is prevalent in late-onset ADHD. Despite these converging lines of evidence, circadian misalignment is yet to be considered in the context of late-onset ADHD – a glaring gap. It is imperative for future research in late-onset ADHD to consider a possible causal role of delayed circadian rhythm phase in adolescence. Clarification of this issue has significant implications for research, clinical care, and public health.

In addition, daytime sleepiness is prevalent in late-onset ADHD. Despite these converging lines of evidence, circadian misalignment is yet to be considered in the context of late-onset ADHD – a glaring gap. It is imperative for future research in late-onset ADHD to consider a possible causal role of delayed circadian rhythm phase in adolescence. Clarification of this issue has significant implications for research, clinical care, and public health.

In the last two years, a significant debate has arisen in our field regarding the occurrence and validity of a “late-onset” Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) phenotype, characterized by the emergence of ADHD symptoms during adolescence. At the heart of this controversy is the traditional conception of ADHD as a neurodevelopmental disorder with onset prior to age 12. The primary evidence for late-onset ADHD consists of four population studies that have consistently demonstrated emergence of ADHD in adolescence, leading researchers to suggest that a late onset of symptoms may represent the “rule rather than the exception” among adults with ADHD. Analysis from a multi-site treatment evaluation study (Multimodal Treatment of ADHD; MTA) also identified cases of ADHD onset in adolescence; however, symptoms were transient (i.e., emerging in adolescence and ceasing prior to adulthood) and/or better explained by substance use or other psychiatric conditions (Caye et al., 2017).

Analysis from a multi-site treatment evaluation study (Multimodal Treatment of ADHD; MTA) also identified cases of ADHD onset in adolescence; however, symptoms were transient (i.e., emerging in adolescence and ceasing prior to adulthood) and/or better explained by substance use or other psychiatric conditions (Caye et al., 2017).

Two theoretical frameworks have been proposed to explain the emergence of ADHD in adolescence: (1) a complex phenotype, which highlights unstable interactions between neurobiological and environmental pressures over time that result in ADHD onset at different points over the lifespan (e.g., underlying ADHD symptoms are attenuated in childhood under certain environmental conditions, such as parental support, and manifest when supports are later removed, resulting in late-onset), and (2) a restricted phenotype, which questions whether potential underlying contributors to ADHD symptoms, such as substance use and other psychiatric disorders, should be considered as causes, or alternatively, exclusionary conditions in conceptualizations of late-onset ADHD (Caye et al. , 2017). In either framework, one question remains paramount: is late-onset ADHD a “true” phenotype of ADHD or a manifestation of other physical, mental, and environmental problems that develop during adolescence?

, 2017). In either framework, one question remains paramount: is late-onset ADHD a “true” phenotype of ADHD or a manifestation of other physical, mental, and environmental problems that develop during adolescence?

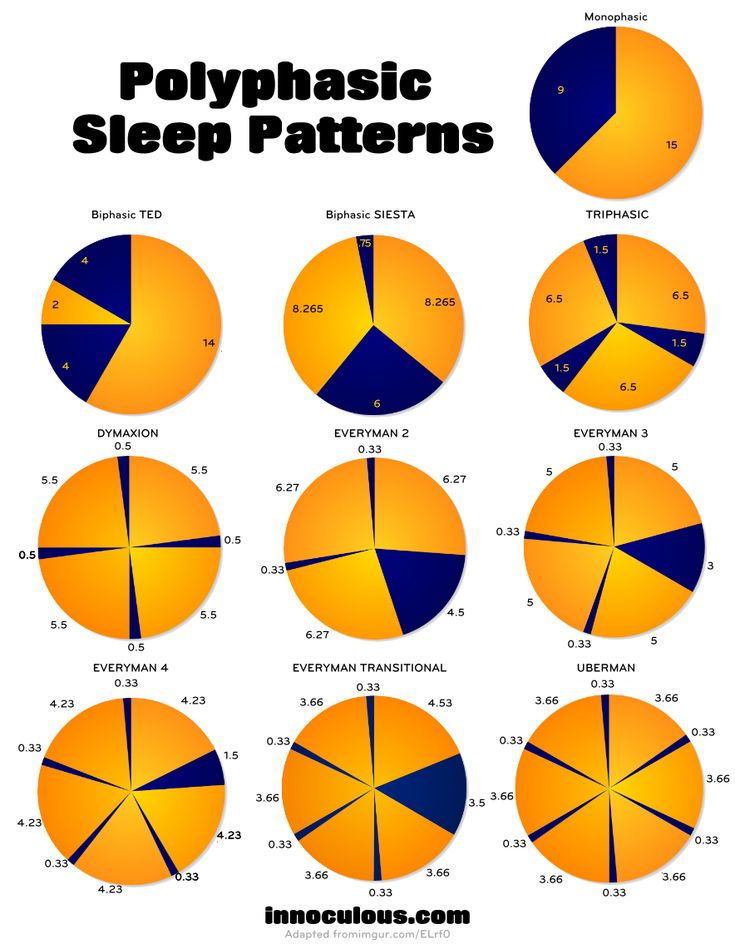

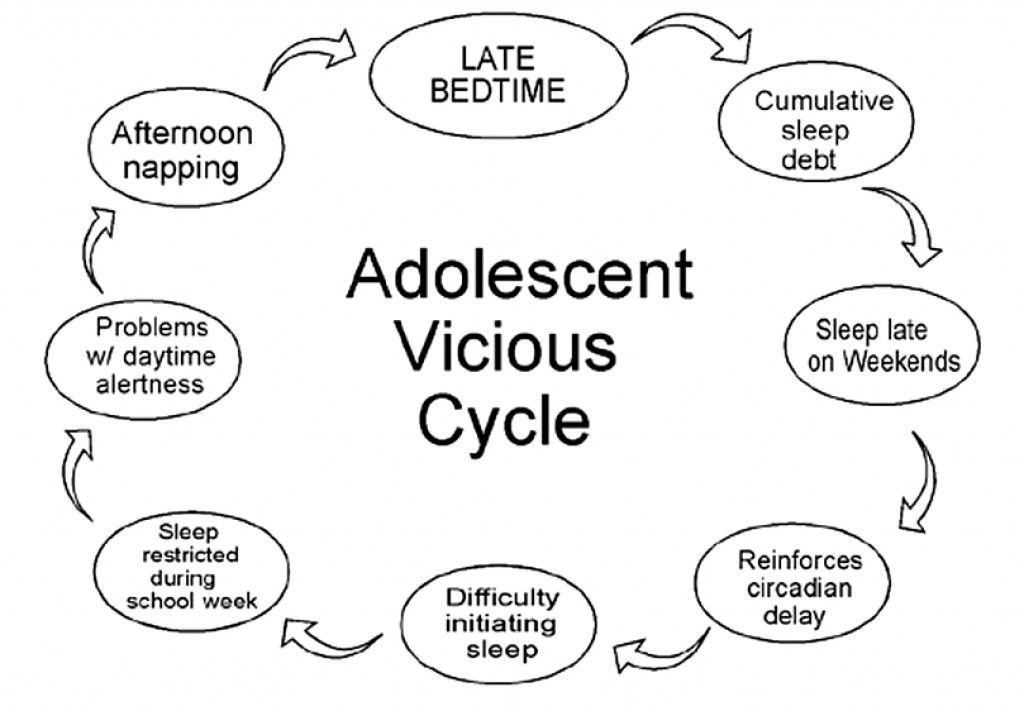

Thus, an acknowledged threat to the late-onset ADHD phenotype concept is the presence of other medical or psychiatric conditions which may “mimic” ADHD symptoms and explain ADHD emergence later in life. For example, conditions such as depression and substance use, which are both associated with inattention, represented a primary explanation for late onset of ADHD symptoms in the MTA study, and were not consistently ruled out in population studies assessing late-onset ADHD (Caye et al., 2017). Another potential explanation for ADHD symptom onset in adolescence that has not been considered is delayed circadian rhythm phase. Delayed circadian rhythm phase is common in adolescence and refers to an endogenous preference for later sleeping and waking times (Roenneberg et al. , 2004). Circadian phase delays – particularly more extreme delays - often result in a misalignment between an adolescent’s internal circadian rhythm and social time, which interferes with social and school performance (e.g., school; Kelley et al., 2015), as well as social jetlag (i.e., variability in sleep/wake schedule across weekdays versus weekends), a phenomenon which independently interferes with daytime functioning (Coogan and McGowan, 2017).

, 2004). Circadian phase delays – particularly more extreme delays - often result in a misalignment between an adolescent’s internal circadian rhythm and social time, which interferes with social and school performance (e.g., school; Kelley et al., 2015), as well as social jetlag (i.e., variability in sleep/wake schedule across weekdays versus weekends), a phenomenon which independently interferes with daytime functioning (Coogan and McGowan, 2017).

There are several reasons to critically consider a role of circadian rhythm misalignment in late-onset ADHD. First, delayed circadian rhythm phase is prevalent and impairing among adults with traditionally-diagnosed (childhood-onset) ADHD. Up to 75% of adults with childhood-onset ADHD exhibit delayed circadian rhythm phase, including a rise in salivary dim-light melatonin onset (DLMO) and alterations in core body temperature and actigraphy-measured sleep-related movements occurring approximately 1.5 hours later in the night than healthy adults. In addition, adults with childhood-onset ADHD exhibit a delay in early morning cortisol rise (i.e., a hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenocortical (HPA) marker of circadian phase), with secretion occurring two hours later than healthy controls. Adults with childhood-onset ADHD are also frequently “night owls” who display delayed circadian preference and increased alertness in the evening (Kooij, 2017, Coogan and McGowan, 2017).

In addition, adults with childhood-onset ADHD exhibit a delay in early morning cortisol rise (i.e., a hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenocortical (HPA) marker of circadian phase), with secretion occurring two hours later than healthy controls. Adults with childhood-onset ADHD are also frequently “night owls” who display delayed circadian preference and increased alertness in the evening (Kooij, 2017, Coogan and McGowan, 2017).

Among adults with childhood-onset ADHD, this circadian rhythm delay and greater evening alertness disrupts sleep (i.e., difficulties initiating and maintaining sleep), results in accumulating sleep debt and daytime sleepiness, and interferes with the timing of meals and activity patterns, which in turn may increase ADHD severity (Kooij, 2017), particularly hyperactivity. Indeed, links between delayed circadian phase and hyperactivity are also observed in healthy adults without ADHD, suggesting that the circadian delay-ADHD relationship may occur across a continuum of psychiatric health (Bijlenga et al. , 2013). When circadian rhythm delays are treated by bright light therapy, ADHD severity is reduced in adults with childhood-onset ADHD (Coogan and McGowan, 2017). These findings have led researchers to suggest that ADHD and sleeplessness resulting from delayed circadian phase in adulthood may represent “two sides of the same physiological and mental coin” (Kooij, 2017).

, 2013). When circadian rhythm delays are treated by bright light therapy, ADHD severity is reduced in adults with childhood-onset ADHD (Coogan and McGowan, 2017). These findings have led researchers to suggest that ADHD and sleeplessness resulting from delayed circadian phase in adulthood may represent “two sides of the same physiological and mental coin” (Kooij, 2017).

Second, the primary evidence for late-onset ADHD focuses on the emergence of ADHD symptoms during adolescence. Three of the four population-based studies concluded with the last point of data collection occurring in young adulthood (ages 17–19), suggesting the symptoms emerged between the ages of 12 (DSM cutoff for ADHD) and late adolescence. In addition, results from the MTA study suggested that for the majority of individuals displaying late-onset ADHD, symptoms were time-limited to the adolescent period and remitted prior to adulthood (Caye et al., 2017). Adolescence is also characterized by normative shifts toward delayed circadian preference in the general population, with variability in the extent of this shift across individuals, such that some individuals shift more toward eveningness than others. For most individuals, circadian preference subsequently shifts again – returning toward morningness – in early adulthood. Indeed, this occurrence is believed to represent a primary biological marker signaling the end of adolescence (Roenneberg et al., 2004). This pattern pinpoints adolescence as a developmental window wherein risk for both delayed circadian phase and emergence of late-onset ADHD symptoms may co-occur. Interestingly, an investigation with adults with childhood-onset ADHD indicated that delayed sleep phase was age-related for healthy controls (i.e., specific to adolescence) but not adults with ADHD, wherein delayed sleep phase tended to be chronic across adulthood (Bijlenga et al., 2013), suggesting the biological shift marking the end of adolescence may not have occurred for these individuals.

For most individuals, circadian preference subsequently shifts again – returning toward morningness – in early adulthood. Indeed, this occurrence is believed to represent a primary biological marker signaling the end of adolescence (Roenneberg et al., 2004). This pattern pinpoints adolescence as a developmental window wherein risk for both delayed circadian phase and emergence of late-onset ADHD symptoms may co-occur. Interestingly, an investigation with adults with childhood-onset ADHD indicated that delayed sleep phase was age-related for healthy controls (i.e., specific to adolescence) but not adults with ADHD, wherein delayed sleep phase tended to be chronic across adulthood (Bijlenga et al., 2013), suggesting the biological shift marking the end of adolescence may not have occurred for these individuals.

Third, there is remarkable overlap in the behavioral and neurocognitive deficits observed in adolescents with ADHD and those with sleep loss resulting from delayed circadian phase, suggesting a strong potential for circadian rhythm misalignment to mimic ADHD symptoms. Specifically, among adolescents, sleep loss occurring in the context of normative circadian misalignment results in increased daytime sleepiness as well as difficulties with attention, distractibility, emotional regulation, memory, and impulsivity/risk-taking (Kelley et al., 2015), symptoms that are also observed in individuals with ADHD. Indeed, adolescents with delayed sleep phase and/or eveningness chronotype preference exhibit higher rates of ADHD symptoms compared to adolescents without circadian delay. Interestingly, among adults, the relationship between eveningness chronotype and ADHD severity may be mediated by social jetlag; however, this has yet to be studied among adolescents (Coogan and McGowan, 2017). Similarly, adolescents with delayed circadian phase and/or eveningness chronotype preference also display poorer school performance, which may be due to circadian disruptions to attention and cognition. Interestingly, when the timing of cognitive testing is aligned with adolescents’ circadian preferences, their performance on executive functioning tasks, including risk-tasking, inhibitory control, and working memory, is enhanced (Kelley et al.

Specifically, among adolescents, sleep loss occurring in the context of normative circadian misalignment results in increased daytime sleepiness as well as difficulties with attention, distractibility, emotional regulation, memory, and impulsivity/risk-taking (Kelley et al., 2015), symptoms that are also observed in individuals with ADHD. Indeed, adolescents with delayed sleep phase and/or eveningness chronotype preference exhibit higher rates of ADHD symptoms compared to adolescents without circadian delay. Interestingly, among adults, the relationship between eveningness chronotype and ADHD severity may be mediated by social jetlag; however, this has yet to be studied among adolescents (Coogan and McGowan, 2017). Similarly, adolescents with delayed circadian phase and/or eveningness chronotype preference also display poorer school performance, which may be due to circadian disruptions to attention and cognition. Interestingly, when the timing of cognitive testing is aligned with adolescents’ circadian preferences, their performance on executive functioning tasks, including risk-tasking, inhibitory control, and working memory, is enhanced (Kelley et al. , 2015).

, 2015).

Fourth, research supports a common genetic basis underlying the expression of delayed circadian phase and ADHD. Specifically, polymorphisms in genes regulating the internal circadian clock that have been related to circadian phase delay have also been associated with ADHD symptoms, particularly the T3111C single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) of the CLOCK gene in adults and children. There is also preliminary support for an association between a PERIOD 2 (PER2) polymorphism and ADHD symptoms in children, although the association did not reach significance at the study- or genome-wide level and warrants replication. Finally, one study examined the molecular rhythmic expression of BMAL1 and PER2 genes in adults with childhood-onset ADHD using oral mucosa sampling, and found rhythmic expression of both genes among healthy adults, but not those with ADHD (Coogan and McGowan, 2017).

Fifth, visual detection of bright light in the environment is integral to the regulation and synchronization of circadian rhythms to the solar day in humans, and adequate alignment between light exposure, the biological circadian clock, and human daytime behaviors is critical for survival, health, and adaptation to the environment. Links between light exposure and cognitive functioning, including attention and executive functioning, are also well-established. Specifically, light exposure appears to directly result in increased attention, alertness, and vigilance, as well as indirectly support the same cognitive processes through the impact of light detection on circadian rhythmicity (LeGates et al., 2014).

Links between light exposure and cognitive functioning, including attention and executive functioning, are also well-established. Specifically, light exposure appears to directly result in increased attention, alertness, and vigilance, as well as indirectly support the same cognitive processes through the impact of light detection on circadian rhythmicity (LeGates et al., 2014).

Regarding ADHD, there is evidence to suggest that ADHD prevalence rates are lowest in regions of the world where exposure to solar intensity is highest. Indeed, in one study, solar intensity was found to have a dose-response relationship with ADHD prevalence, explaining up to 41% of the variance in ADHD prevalence among children and up to 57% of the variance among adults, suggesting that exposure to bright light may be protective against ADHD, and this effect which may be driven by improvement in circadian regularity and timing (Arns et al., 2013). In addition, adults with childhood-onset ADHD may be hypersensitive to light, resulting in prolonged use of sunglasses throughout the year, which may also interfere with dopamine and melatonin regulation and circadian functioning (Kooij, 2017).

Sixth, a study assessing prevalence of late-onset ADHD in clinical settings found high rates of excessive daytime sleepiness among individuals with a late-onset ADHD presentation (~60%). In addition, for most of the individuals with late-onset ADHD criteria, onset of both daytime sleepiness and ADHD occurred in adulthood, suggesting that the emergence of these symptoms may coincide (Lopez et al., 2017). Daytime sleepiness frequently results from delayed circadian phase and thus, may be an indicator of circadian misalignment in late-onset ADHD.

Taken together, this evidence begs the question: Could delayed circadian phase, emerging more so for some adolescents than others, result in a late-onset ADHD presentation? There are at least two mechanisms by which circadian rhythm misalignment in adolescence might contribute to late-onset ADHD. First, delayed circadian phase may directly result in onset of “ADHD-like” symptoms for some adolescents; for example, those who experience greater shifts toward eveningness. For example, individuals may be predisposed to experience delayed circadian rhythm phase due to variants in clock genes. During adolescence, these genetic variants may determine the expression of delayed circadian phase, and misalignment between intrinsic circadian rhythms and social time (e.g., school start time) may result in sleep loss, social jet lag, daytime sleepiness, and perhaps reduced light exposure, as these adolescents may sleep more during the day (e.g., weekends, after school naps). Sleep loss may then result in the appearance of symptoms that mimic ADHD, including poorer attention and greater impulsivity and distractibility. This explanation is consistent with the restricted phenotype framework, which suggests that alternative explanations (in this case, circadian rhythm misalignment) may account for the appearance of ADHD-like symptoms in adolescence (Caye et al., 2017).

For example, individuals may be predisposed to experience delayed circadian rhythm phase due to variants in clock genes. During adolescence, these genetic variants may determine the expression of delayed circadian phase, and misalignment between intrinsic circadian rhythms and social time (e.g., school start time) may result in sleep loss, social jet lag, daytime sleepiness, and perhaps reduced light exposure, as these adolescents may sleep more during the day (e.g., weekends, after school naps). Sleep loss may then result in the appearance of symptoms that mimic ADHD, including poorer attention and greater impulsivity and distractibility. This explanation is consistent with the restricted phenotype framework, which suggests that alternative explanations (in this case, circadian rhythm misalignment) may account for the appearance of ADHD-like symptoms in adolescence (Caye et al., 2017).

Alternatively, delayed circadian phase may indirectly result in late-onset ADHD. For example, circadian misalignment may serve as a neurobiological stressor, not stable over time but specific to adolescence, which triggers the expression of underlying ADHD traits. Specifically, individuals may be predisposed to both delayed circadian phase and ADHD due to variants in clock genes. During adolescence, these variants determine the expression of delayed circadian phase, which then contributes to sleep loss, social jetlag, daytime sleepiness, and reduced light exposure. Sleep loss may then result in increased psychosocial stress; for example, by impairing academic, emotional, or social functioning (Kelley et al., 2015). Increased stress, in turn, may potentially result in ADHD onset by triggering expression of underlying genes, increasing the severity of subthreshold symptoms, and/or altering the trajectory of neural maturation. This hypothesis is consistent with the broad phenotype framework of late-onset ADHD (Caye et al., 2017). It should be noted that the proposed mechanisms are speculative and require empirical examination, as described below. In addition, it is important to note that relationships between delayed circadian phase and ADHD symptoms are likely to be bidirectional; for example, adolescents struggling with inattention are also more likely to stay up late to complete work, consume more caffeine, and overuse nighttime technology, which may in turn impact sleep timing (Lunsford-Avery et al.

Specifically, individuals may be predisposed to both delayed circadian phase and ADHD due to variants in clock genes. During adolescence, these variants determine the expression of delayed circadian phase, which then contributes to sleep loss, social jetlag, daytime sleepiness, and reduced light exposure. Sleep loss may then result in increased psychosocial stress; for example, by impairing academic, emotional, or social functioning (Kelley et al., 2015). Increased stress, in turn, may potentially result in ADHD onset by triggering expression of underlying genes, increasing the severity of subthreshold symptoms, and/or altering the trajectory of neural maturation. This hypothesis is consistent with the broad phenotype framework of late-onset ADHD (Caye et al., 2017). It should be noted that the proposed mechanisms are speculative and require empirical examination, as described below. In addition, it is important to note that relationships between delayed circadian phase and ADHD symptoms are likely to be bidirectional; for example, adolescents struggling with inattention are also more likely to stay up late to complete work, consume more caffeine, and overuse nighttime technology, which may in turn impact sleep timing (Lunsford-Avery et al. , 2016).

, 2016).

Taken together, evidence suggests consideration of circadian rhythm misalignment is vital to informing our understanding of late-onset ADHD. From a research perspective, it is important to clarify whether circadian rhythm misalignment in adolescence represents (1) a better explanation for the occurrence of ADHD-like symptoms emerging later in development, (2) a neurobiological stressor triggering onset of a “true” ADHD phenotype, or both. Longitudinal studies evaluating ADHD symptoms though childhood, adolescence, and adulthood and including measures of circadian preference and/or objective measures of circadian timing (e.g., DLMO) may assess the extent to which circadian misalignment is present in individuals with late-onset ADHD as well as the temporal order of onset of circadian misalignment, stressors, and ADHD symptoms.

Experimental treatment outcome studies may also shed light on whether circadian misalignment directly results in ADHD-like symptoms. For example, if adolescents exhibit both late-onset ADHD and circadian misalignment, investigating the impact of circadian rhythm treatments, such as melatonin and/or bright light therapies, on ADHD severity in the absence of ADHD-specific treatments (e. g., stimulants) may elucidate whether delayed circadian phase is contributing to an ADHD-like presentation. If ADHD symptoms remit following circadian intervention, this would suggest that symptoms were due to circadian misalignment rather that a true ADHD presentation. Additional treatment outcomes studies comparing the efficacy of circadian treatments and traditional ADHD interventions on ADHD severity would further clarify this issue.

g., stimulants) may elucidate whether delayed circadian phase is contributing to an ADHD-like presentation. If ADHD symptoms remit following circadian intervention, this would suggest that symptoms were due to circadian misalignment rather that a true ADHD presentation. Additional treatment outcomes studies comparing the efficacy of circadian treatments and traditional ADHD interventions on ADHD severity would further clarify this issue.

Clinically, enhanced understanding of delayed circadian phase and its role in ADHD onset may critically impact how we assess and treat adolescents and adults presenting with a concern about ADHD. If circadian misalignment plays a causal role in the emergence of ADHD symptoms in adolescence, best-practice evaluations for ADHD may benefit from circadian rhythm assessment, which would aid differential diagnosis. Additionally, treatments targeting circadian misalignment such as light therapy and/or melatonin may be more appropriate than traditional ADHD interventions such as stimulants. Finally, from a public health standpoint, if late-onset ADHD symptoms result from circadian misalignment, accurate diagnosis may contribute to lower healthcare costs through implementation of effective treatments (reducing frequency of subsequent visits) and elimination of unnecessary ADHD-specific interventions that may not provide benefit to the patient. These are open questions for scientific inquiry; however, from the reviewed evidence, it is clearly imperative for models of late-onset ADHD to account for the potential influence of circadian rhythms on changes in behavior and attention over the lifespan.

Finally, from a public health standpoint, if late-onset ADHD symptoms result from circadian misalignment, accurate diagnosis may contribute to lower healthcare costs through implementation of effective treatments (reducing frequency of subsequent visits) and elimination of unnecessary ADHD-specific interventions that may not provide benefit to the patient. These are open questions for scientific inquiry; however, from the reviewed evidence, it is clearly imperative for models of late-onset ADHD to account for the potential influence of circadian rhythms on changes in behavior and attention over the lifespan.

Dr. Lunsford-Avery receives funding for studies on sleep and ADHD from the National Institute of Mental Health grant K23-MH-108704. Dr. Lunsford-Avery has received consulting fees from Behavioral Innovations Group. Dr. Kollins has received research support and/or consulting fees from the following commercial sources: Akili Interactive, Bose, Jazz, KemPharm, Medgenics, Neos, Otsuka, Rhodes, Shire, and Sunovion.

- Arns M, van der Heijden KB, Arnold LE, & Kenemans JL (2013). Geographic Variation in the Prevalence of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: The Sunny Perspective. Biological Psychiatry, 74, 585–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijlenga D, van der Heijden KB, Breuk M, van Someren EJ, Lie ME, Boonstra AM, Swaab HJT & Kooij JJS (2013). Associations Between Sleep Characteristics, Seasonal Depressive Symptoms, Lifestyle, and ADHD Symptoms in Adults. Journal of Attention Disorders, 17, 261–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caye A, Sibley MH, Swanson JM, & Rohde LA (2017). Late-Onset ADHD: Understanding the Evidence and Building Theoretical Frameworks. Curr Psychiatry Rep, 19, 106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coogan AN, & McGowan NM (2017). A systematic review of circadian function, chronotype and chronotherapy in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord, 9, 129–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley P, Lockley SW, Foster RG, & Kelley J (2015).

Synchronizing education to adolescent biology: ‘let teens sleep, start school later’. Learning Media and Technology, 40, 210–226. [Google Scholar]

Synchronizing education to adolescent biology: ‘let teens sleep, start school later’. Learning Media and Technology, 40, 210–226. [Google Scholar] - Kooij S (2017). Circadian rhythm and sleep in ADHD – cause or life style factor? 30th Annual European Neuropsychopharmacology Congress (pp. S535). Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- LeGates TA, Fernandez DC, & Hattar S (2014). Light as a central modulator of circadian rhythms, sleep and affect. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 15, 443–454. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez R, Micoulaud-Franchi JA, Galera C, & Dauvilliers Y (2017). Is adult-onset attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder frequent in clinical practice? Psychiatry Res, 257, 238–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunsford-Avery JR, Krystal AD & Kollins SH (2016). Sleep disturbances in adolescents with ADHD: A systematic review and framework for future research. Clin Psychol Rev, 50, 159–174. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roenneberg T, Kuehnle T, Pramstaller PP, Ricken J, Havel M, Guth A, & Merrow M (2004).

A marker for the end of adolescence. Curr Biol, 14, R1038–1039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

A marker for the end of adolescence. Curr Biol, 14, R1038–1039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Features of sleep organization in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Features of sleep organization in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder Website of the publishing house "Media Sfera"

contains materials intended exclusively for healthcare professionals. By closing this message, you confirm that you are a registered medical professional or student of a medical educational institution.

Kalashnikova T.P.

Perm State Medical University. acad. E.A. Wagner» of the Ministry of Health of Russia

Anisimov G.V.

The first medical and pedagogical center "Lingua Bona"

Features of sleep organization in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Authors:

Kalashnikova T.P., Anisimov G.V.

More about authors

Journal: Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. S.S. Korsakov. Special issues. 2021;121(4‑2): 55‑60

S.S. Korsakov. Special issues. 2021;121(4‑2): 55‑60

DOI: 10.17116/jnevro202112104255

How to quote:

Kalashnikova T.P., Anisimov G.V. Features of sleep organization in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. S.S. Korsakov. Special issues. 2021;121(4‑2):55‑60.

Kalashnikova TP, Anisimov GV. Features of the organization of sleep in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Zhurnal Nevrologii i Psikhiatrii imeni S.S. Korsakova. 2021;121(4‑2):55‑60. (In Russ.)

https://doi.org/10.17116/jnevro202112104255

Read metadata

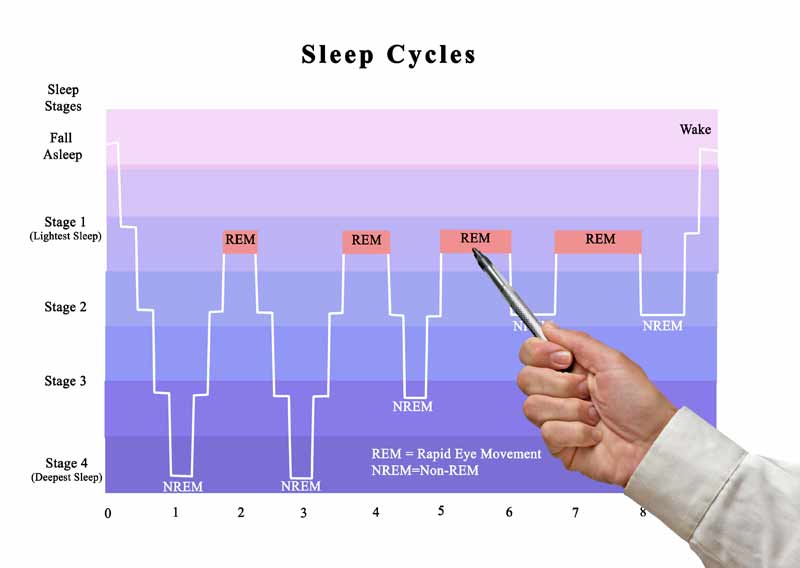

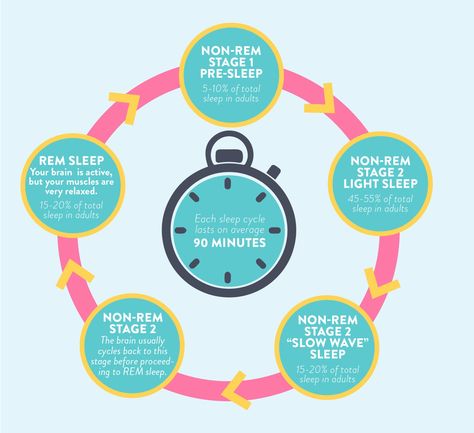

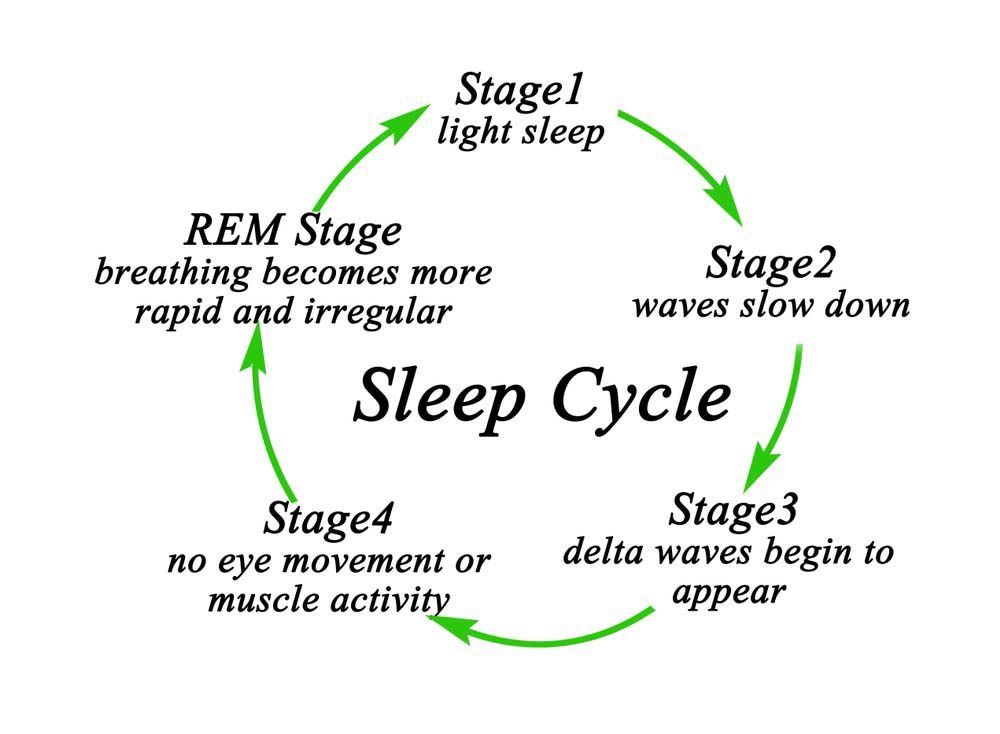

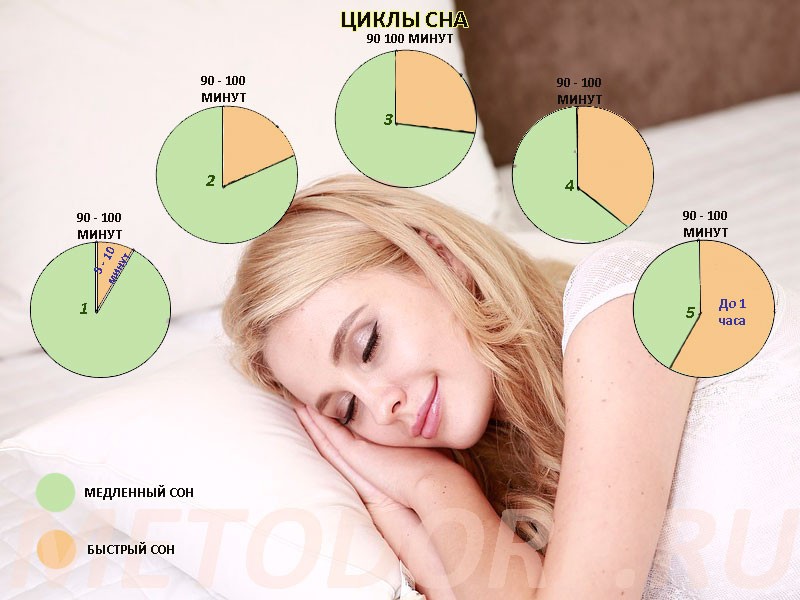

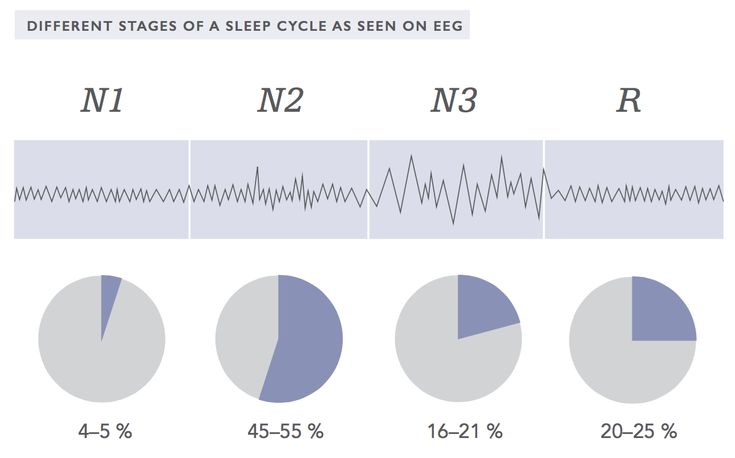

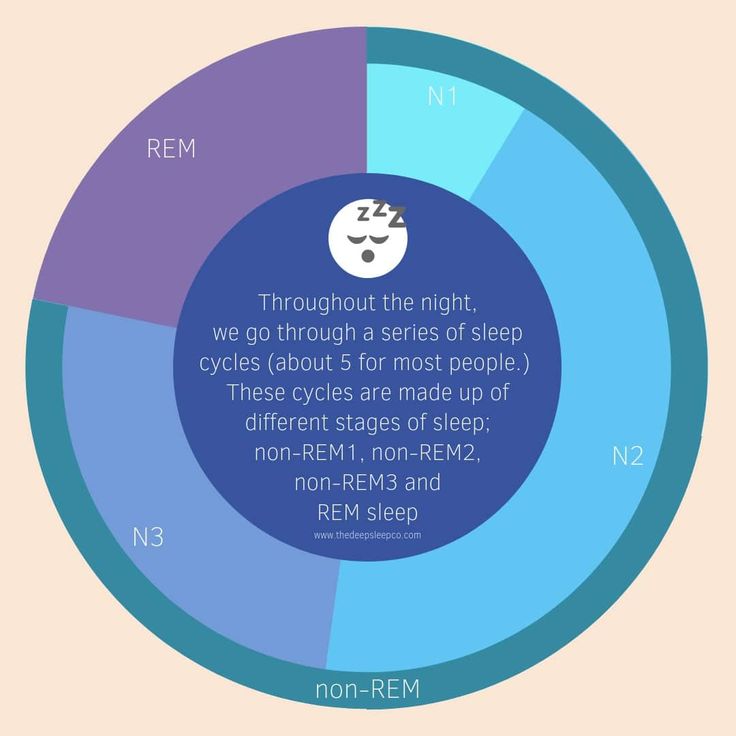

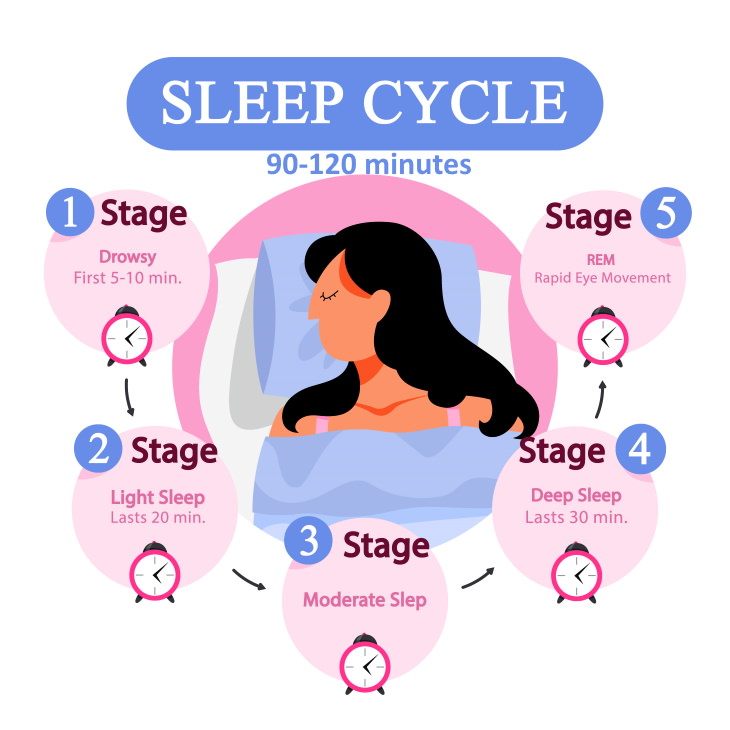

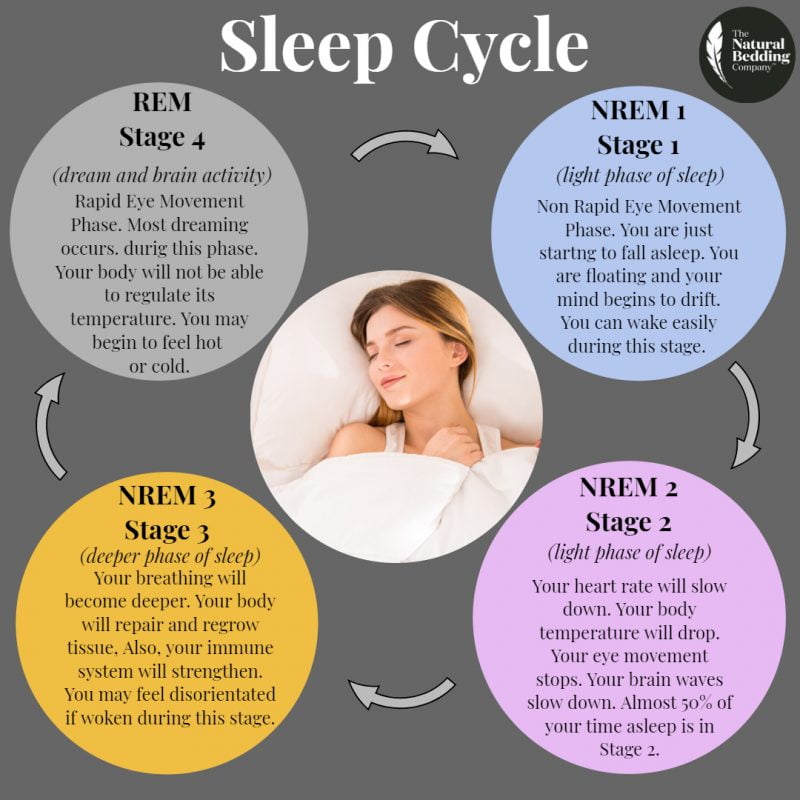

The article reflects modern ideas about the clinical features of sleep in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), the macrostructure of sleep, its cyclic organization and possible common links in the pathogenesis of sleep disorders and regulatory functions, the level of social exclusion of patients with ADHD. Typical for children with ADHD are difficulty going to sleep and prolonged falling asleep (resistance to sleep time), increased motor activity associated with sleep, including the association of ADHD with restless legs syndrome (RLS) and periodic leg movement syndrome during sleep (Periodic Leg Movement during Sleep—PLMS), daytime sleepiness. The presence of circadian desynchrony in children with ADHD explains the relationship between chronotype, circadian typology, and clinical manifestations of the syndrome. Multidirectional information about the representation of the phase of REM sleep - sleep with rapid eye movements (REM) according to nocturnal polysomnography in children with ADHD depends on age. However, the change in the proportion of REM sleep during the night is considered as a leading factor in the pathogenesis of ADHD manifestations. Common pathogenetic mechanisms for sleep disorders and ADHD are identified: various variants of melatonin, dopamine, serotonin metabolism disorders aggravated by "social jet lag", as well as changes in the concentration of iron and ferritin in the blood, which can explain the frequency of RLS and PLMS in children with ADHD.

Typical for children with ADHD are difficulty going to sleep and prolonged falling asleep (resistance to sleep time), increased motor activity associated with sleep, including the association of ADHD with restless legs syndrome (RLS) and periodic leg movement syndrome during sleep (Periodic Leg Movement during Sleep—PLMS), daytime sleepiness. The presence of circadian desynchrony in children with ADHD explains the relationship between chronotype, circadian typology, and clinical manifestations of the syndrome. Multidirectional information about the representation of the phase of REM sleep - sleep with rapid eye movements (REM) according to nocturnal polysomnography in children with ADHD depends on age. However, the change in the proportion of REM sleep during the night is considered as a leading factor in the pathogenesis of ADHD manifestations. Common pathogenetic mechanisms for sleep disorders and ADHD are identified: various variants of melatonin, dopamine, serotonin metabolism disorders aggravated by "social jet lag", as well as changes in the concentration of iron and ferritin in the blood, which can explain the frequency of RLS and PLMS in children with ADHD. This group of patients showed a change in the number of sleep cycles during the night. Possible strategies for correcting sleep disorders in children with ADHD and their impact on the manifestation of ADHD are discussed.

This group of patients showed a change in the number of sleep cycles during the night. Possible strategies for correcting sleep disorders in children with ADHD and their impact on the manifestation of ADHD are discussed.

Keywords:

preschool children

sleep disorders

ADHD

polysomnography in children

R.E.M. sleep

homeostres

Authors:

Kalashnikova T.P.

Perm State Medical University. acad. E.A. Wagner» of the Ministry of Health of Russia

Anisimov G.V.

The first medical and pedagogical center "Lingua Bona"

References:

- Kovalzon V.M. Fundamentals of somnology. Moscow: BINOM; 2012.

- Mulas F, Rojas M, Gandía R. Sleep in neurodevelopmental disorders. Review Medicine (B Aires). 2019;79(3):33-36.

- Nevšímalová S, Bruni O. Sleep Disorders in Children. Springer International Publishing Switzerland; 2017.

- Kalil NF, Nunes ML. Evaluation of sleep organization in patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and ADHD as a comorbidity of epilepsy.

Sleep Med. 2017;33:91-96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2016.08.013

Sleep Med. 2017;33:91-96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2016.08.013 - Miano S, Esposito M, Foderaro G, Ramelli GP, Pezzoli V, Manconi M. Sleep-Related Disorders in Children with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Preliminary Results of a Full Sleep Assessment Study. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2016;22(11):906-914. https://doi.org/10.1111/cns.12573

- Serhat T, Somuk BT, Sapmaz E, Bilgiç A. Effect of adenotonsillectomy on sleep problems, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms, and quality of life of children with adenotonsillar hypertrophy and sleep-disordered breathing. J Psychiatry Med. 2019;54(3):231-241. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091217419829988

- Hvolby A. Associations of sleep disturbance with ADHD: Implications for treatment. ADHD Atten. Deficit Hyperact. Discord. 2015;7:1-18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-014-0151-0

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd edition. American Psychiatric Association; Washington DC, USA.

1980.

1980. - Hiscock H, Sciberras E, Mensah F, Gerner B, Efron D, Khano S, Oberklaid F. Impact of a behavioral sleep intervention on symptoms and sleep in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and parental mental health: randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2015;20:350:h68. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h68

- Kirov R, Brand S. Sleep problems and their effect in ADHD. Expert Rev Neurother. 2014;14(3):287-299. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737175.2014.885382

- Wilhelm I, Diekelmann S, Molzow I, Wilhelm I, Diekelmann S, Molzow I, Ayoub A, Mölle M, Born J. Sleep selectively enhances memory expected to be of future relevance. J Neurosci. 2011;31(5):1563-1569. Pediatric Res. 2019:85(4):449-455. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3575-10.2011

- Bolden Jennifer 1, Jenna E Gilmore-Kern 1, Jonathan P, Fillauer 1. Associations among sleep problems, executive dysfunctions, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptom domains in college students. J Am Coll Health.

2019;67(4):320-327. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2018.1481070

2019;67(4):320-327. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2018.1481070 - Schlarb AA, Sopp R, Ambiel D. Chronotype-related differences in childhood and adolescent aggression and antisocial behavior—a review of the literature. J Chronobiol Int. 2014;31(1):1-16. https://doi.org/10.3109/07420528.2013.829846

- Van der Heijden KB, Smits MG, Van Someren EJ, Ridderinkhof KR, Gunning WB. Effect of melatonin on sleep, behavior, and cognition in ADHD and chronic sleep-onset insomnia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:233-241. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000246055.76167.0d

- Bijlenga D, Madelon A, Vollebregt JJ, Kooij S, Arns M. The role of the circadian system in the etiology and pathophysiology of ADHD: time to redefine ADHD? Atten Defi Hyperact Disord. 2019;11(1):5-19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-018-0271-z

- Veatch OJ, Goldman SE, Adkins KW, Malow BA. Melatonin in children with autism spectrum disorders: how does the evidence fi t together? J Nat Sci.

2015;1(7):e125.

2015;1(7):e125. - Coogan AN, McGowan NM. A systematic review of circadian function, chronotype and chronotherapy in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Atten Defi Hyperact Disord. 2017;9(3):129-147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-016-0214-5

- Veenman B, Luman M, Oosterlaan J. Further Insight into the Effectiveness of a Behavioral Teacher Program Targeting ADHD Symptoms Using Actigraphy, Classroom Observations and Peer Ratings. Front Psychol. 2017;11:8:1157. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01157

- Benk Durmus F, Rodopman Arman A, Ayaz AB. Chronotype and its relationship with sleep disorders in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Chronobiol Int. 2017;34(7):886-894. https://doi.org/10.1080/07420528.2017.1329207

- McGowan NM, Voinescu BI, Coogan AN. Sleep quality, chronotype and social jetlag differentially associate with symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults. Chronobiol Int. 2016;33(10):1433-1443. https://doi.

org/10.1080/07420528.2016.1208214

org/10.1080/07420528.2016.1208214 - Miano S, Amato N, Foderaro G, Pezzoli V, Ramelli GP, Toffolet L, Manconi M. Sleep phenotypes in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Sleep Med. 2019;60:123-131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2018.08.026

- Gruber R, Fontil L, Bergmame L, Wiebe ST, Amsel R, Frenette S, Carrier J. Contributions of circadian tendencies and behavioral problems to sleep onset problems of children with ADHD. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12(1):212. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-212

- De Crescenzo F, Licchelli S, Ciabattini M, Menghini D, Armando M, Alfieri P, Mazzone L, Pontrelli G, Livadiotti S, Foti F, Quested D, Vicari S. The use of actigraphy in the monitoring of sleep and activity in ADHD: A meta-analysis. SleepMed Rev. 2016;26:9-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2015.04.002

- Vigliano P, Galloni GB, Bagnasco I, Delia G, Moletto A, Mana M, Cortese S. Sleep in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) before and after 6-month treatment with methylphenidate: a pilot study.

Eur J Pediatr. 2016;175(5):695-704. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-016-2695-9

Eur J Pediatr. 2016;175(5):695-704. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-016-2695-9 - Kirov R, Brand S, Banaschewski T, Rothenberger A. Opposite Impact of REM Sleep on Neurobehavioral Functioning in Children with Common Psychiatric Disorders Compared to Typically Developing Children . Front Psychol. 2017;7:2059. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.02059

- Silvestri R, Gagliano A, Aricò I, Calarese T, Cedro C, Bruni O, Condurso R, Germanò E, Gervasi G, Siracusano R, Vita G, Bramanti P Sleep disorders in children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) recorded overnight by video-polysomnography. Sleep Med. 2009;10(10):1132-1138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2009.04.003

- Bioulac S, Micoulaud-Franchi JA, Philip P. Excessive daytime sleepiness in patients with ADHD — diagnostic and management strategies. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(8):608. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-015-0608-7

- Lucas I, Mulraney M, Sciberras E. Sleep problems and daytime sleepiness in children with ADHD: associations with social, emotional and behavioral functioning at school, a cross-sectional study.

Behav Sleep Med. 2019;17(4):411-422. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2017.1376207

Behav Sleep Med. 2019;17(4):411-422. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2017.1376207 - Wagner J, Schlarb AA. Subtypes of ADHD and their association with sleep disturbances in children. somnologie. 2012;16(2):118-124.

- Angriman M, Caravale B, Novelli L, Ferri R, Bruni O. Sleep in children with neurodevelopmental disabilities. Neuropediatrics. 2015;46(3):199-210. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1550151

- Garcia-Rill E, Charlesworth A, Heister D, Meijun Ye, Hayar A. The developmental decrease in REM sleep: the role of transmitters and electrical coupling. Sleep. 2008;31(5):673-690. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/31.5.673

- Chamorro M, Lara JP, Insa I, Espadas M, Alda-Diez JA. Evaluation and treatment of sleep problems in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: an update of the evidence. Rev Neurol. 2017:64(9):413-421. https://doi.org/10.33588/rn.6409.2016539

- Van der Heijden KB, Stoffelsen RJ, Popma A, Swaab H. Sleep, chronotype, and sleep hygiene in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorder, and controls.

Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;27(1):99-111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-017-1025-8

Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;27(1):99-111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-017-1025-8 - Chieffi S, Carotenuto M, Monda V, Valenzano A, Villano I, Precenzano F, Tafuri D, Salerno M, Filippi N, Nuccio F, Ruberto M, De Luca V, Cipolloni L, Cibelli G, Mollica MP, Iacono D, Nigro E, Monda M, Messina G, Messina A. Orexin System: The Key for a Healthy Life. front Physiol. 2017;31:8:357. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2017.00357

- Vincenza S, Maiello M, Pallucchini A, Novi M, Elefante C, De Dominicis F, Palagini L, Biederman J, Perugi G. Adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and clinical correlates of delayed sleep phase disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113162

- Li J, Hu Z, de Lecea L. The Hypocretins/orexins: integrators of multiple physiological functions. Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171(2):332-350. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.12415

- Youssef J, Singh K, Huntington N, Becker R, Kothare SV. Relationship of serum ferritin levels to sleep fragmentation and periodic limb movements of sleep on polysomnography in autism spectrum disorders.

Pediatric Neurol. 2013;49(4):274-278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.06.012

Pediatric Neurol. 2013;49(4):274-278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.06.012 - Langberg JM, Breaux RP, Cusick CN, Green CD, Smith ZR, Molitor SJ. Intraindividual variability of sleep/wake patterns in adolescents with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60(11):1219-1229. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13082

- Miano S, Ninfa A, Garbazza C, Abbafati M, Foderaro G, Pezzoli V, Ramelli GP, Manconi M. Shooting a high-density electroencephalographic picture on sleep in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Sleep. 2019;42(11):zsz167. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsz167

- Kalashnikova T.P., Anisimov G.V., Kravtsov Yu.I., Seliverstova G.A., Kravtsova E.Yu., Konshina N.V. , Skurikhin A.V. Clinical and electroencephalographic characteristics of sleep in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. S.S. Korsakov. 2013;1(113):38-41.

- Craig SG, Weiss MD, Hudec KL, Gibbins C.

The Functional Impact of Sleep Disorders in Children with ADHD. J Atten Discord. 2020;24(4):499-508. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054716685840

The Functional Impact of Sleep Disorders in Children with ADHD. J Atten Discord. 2020;24(4):499-508. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054716685840 - Konshina N.V. Clinical and polysomnographic features of sleep in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Perm Medical Journal. 2013;3:26-29.

- France KG, Blampied NM, Wilkinson PJ. Treatment of infant sleep disturbance by trimeprazine in combination with extinction. DevBehav Pediatr. 1991;12(5):308-314.

- Khachatryan L.G., Maksimova M.S., Ozhegova I.Yu., Belousova N.A. Therapy of long-term consequences of perinatal damage to the nervous system in children. Russian medical journal. 2016;6:373-375.

- S. A. Syunyakov, T. S. Syunyakov, L. V. Romasenko, M. V. Metlina, A. S. Lapitskaya, Yu. A. Aleksandrovsky, G. G. Neznamov Therapeutic efficacy and safety of using Homeostres as an anxiolytic agent in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. Psychiatry. 2014;16(3):62-69.

- Galland BC, Tripp EG, Taylor BJ.

The sleep of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder on and off methylphenidate: a matched case-control study. J Sleep Res. 2010;19(2):366-373. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2869.2009.00795.x

The sleep of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder on and off methylphenidate: a matched case-control study. J Sleep Res. 2010;19(2):366-373. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2869.2009.00795.x - Villano I, Messina A, Valenzano A, Moscatelli F, Esposito T, Monda V, Esposito M, Precenzano F, Carotenuto M, Viggiano A , Chieffi S, Cibelli G, Monda M, Messina G. Basal Forebrain Cholinergic System and Orexin Neurons: Effects on Attention. Front Behav Neurosci. 2017;31:11:10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2017.00010

- Holvoet E, Gabriëls L. Disturbed sleep in children with ADHD: is there a place for melatonin as a treatment option? Tijdschr Psychiatr. 2013;55(5):349-357.

- Arns M, Kenemans JL. Neurofeedback in ADHD and insomnia: vigilance stabilization through sleep spindles and circadian networks. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;44:183-194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.10.006

Close metadata

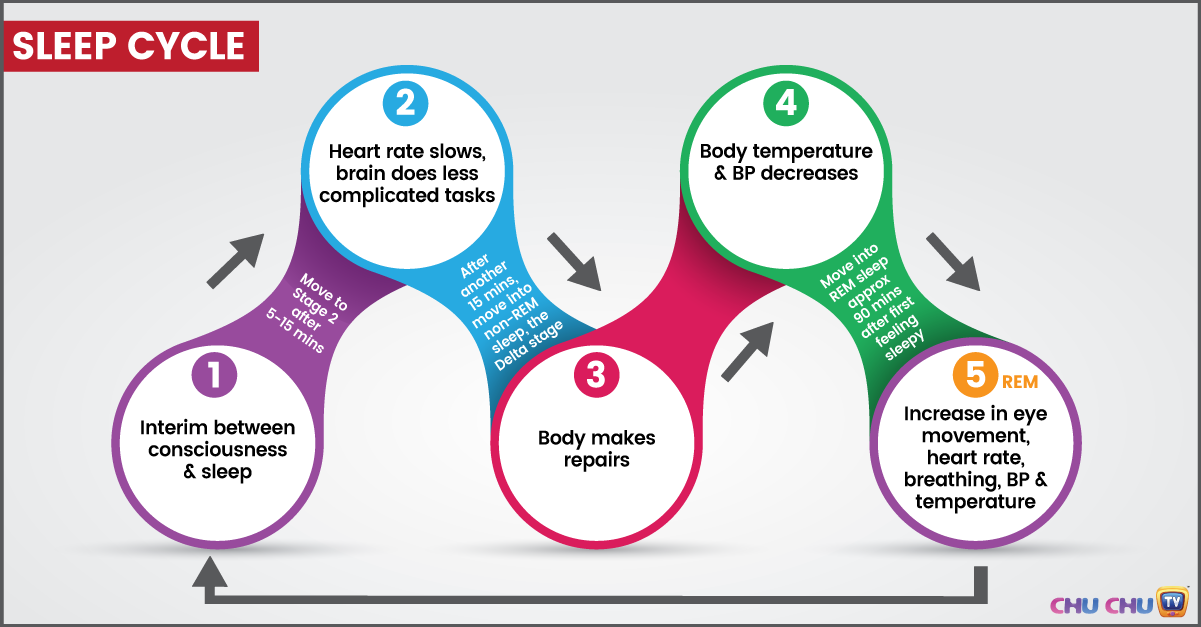

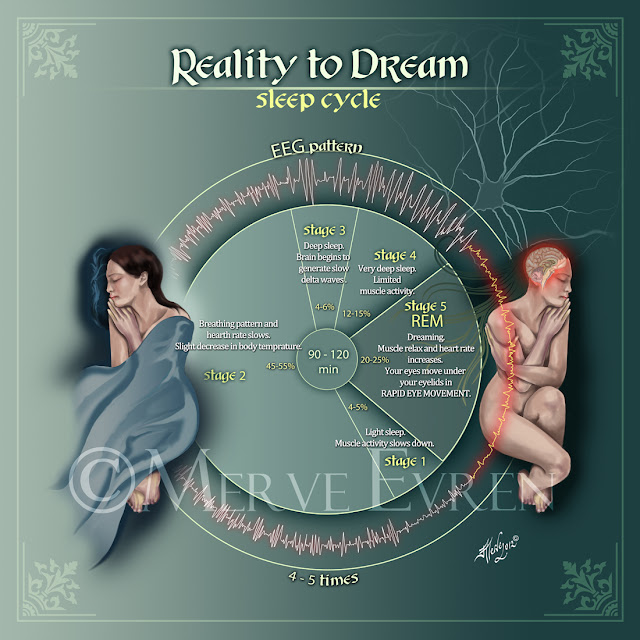

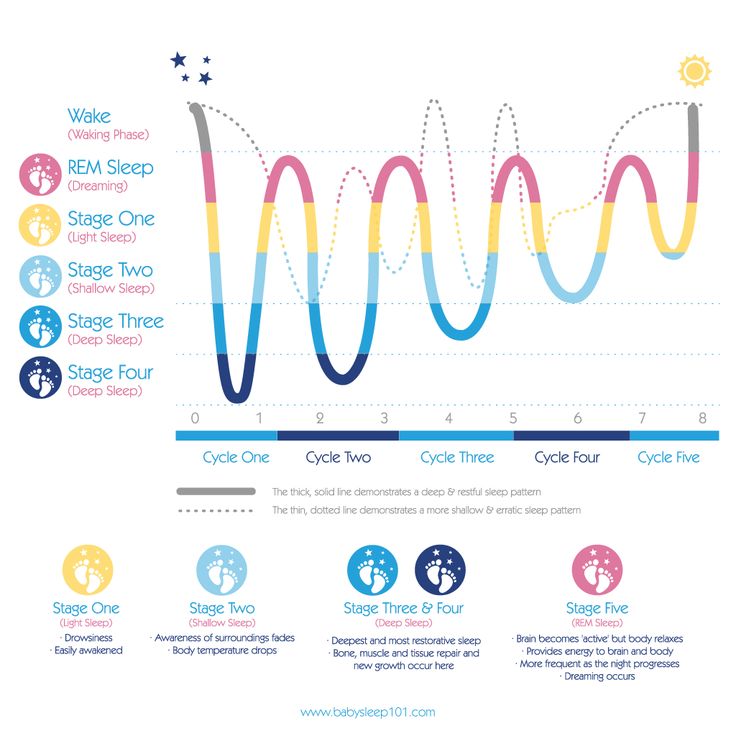

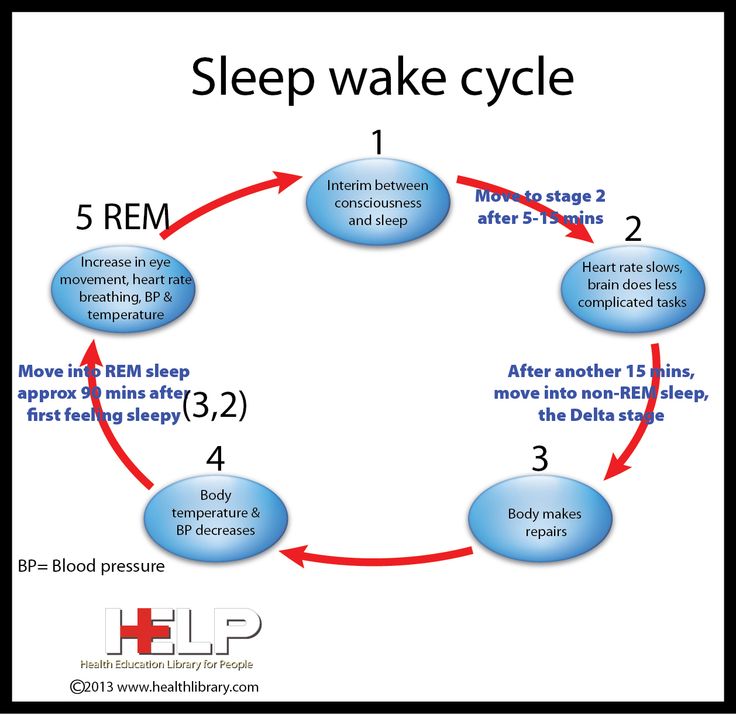

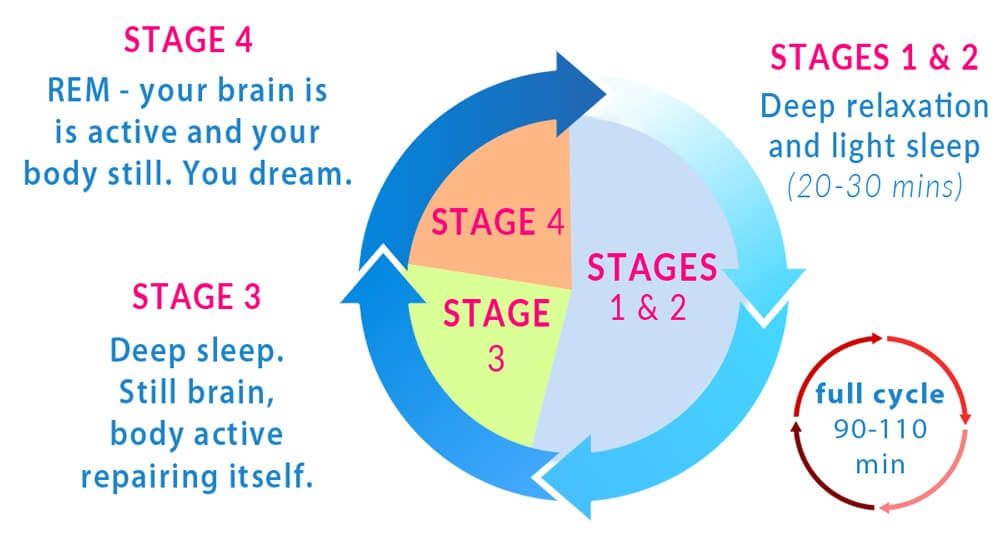

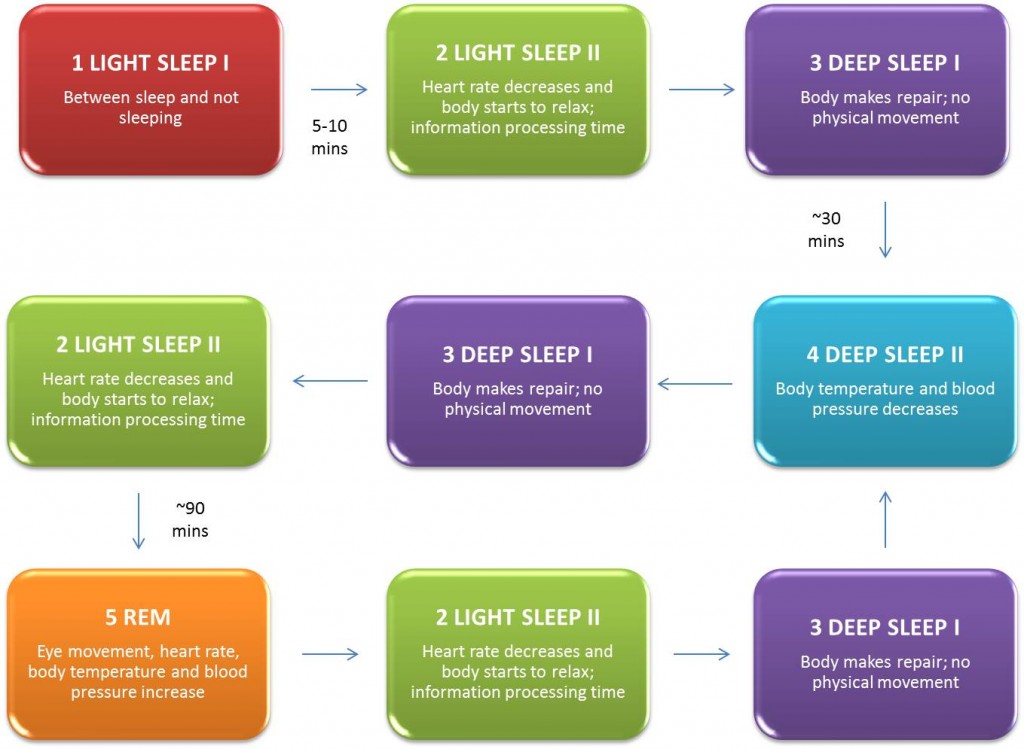

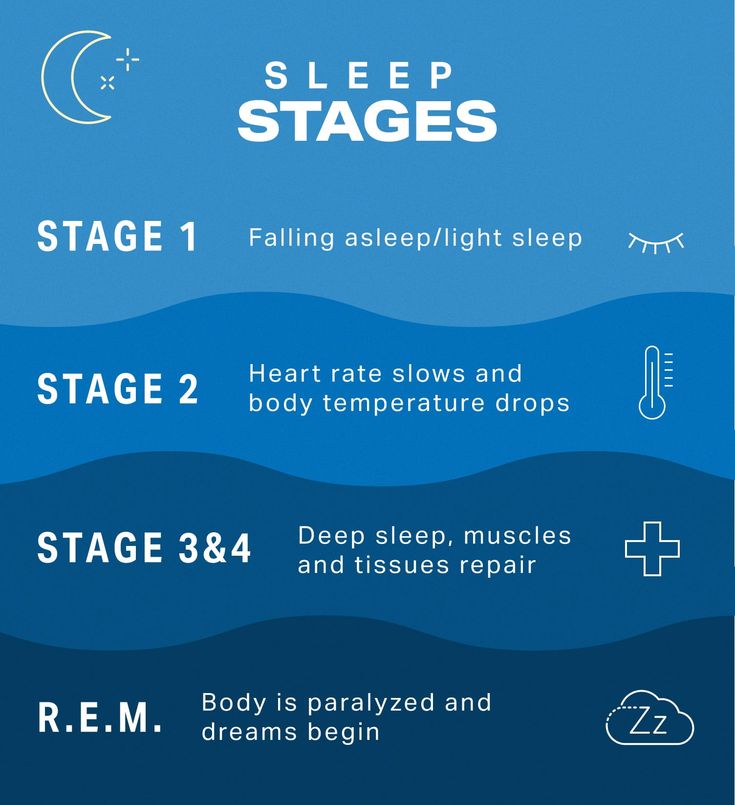

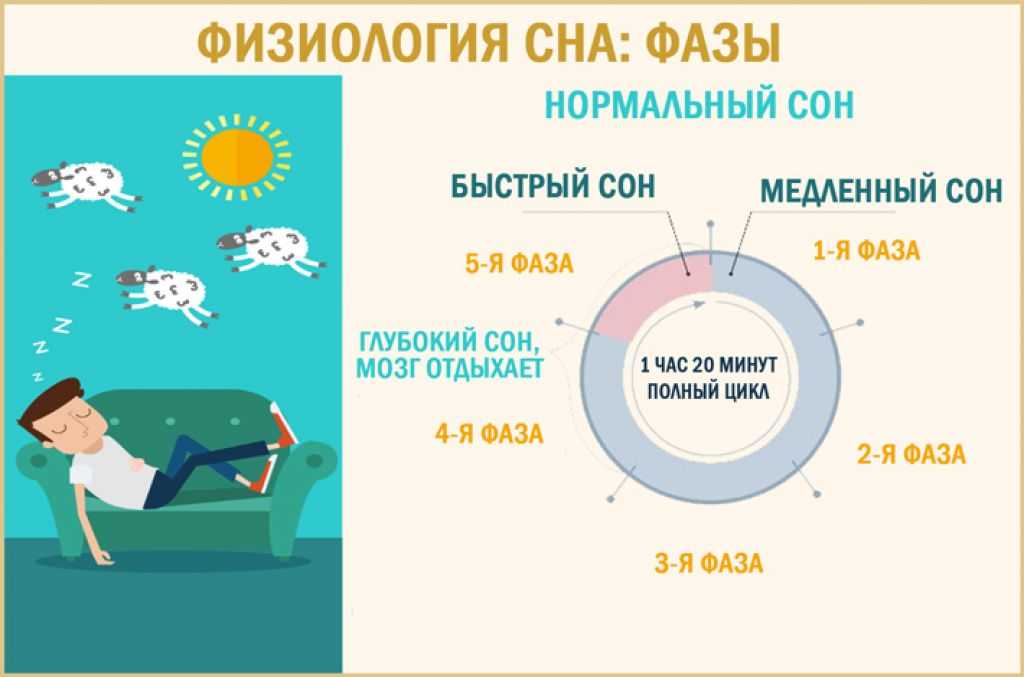

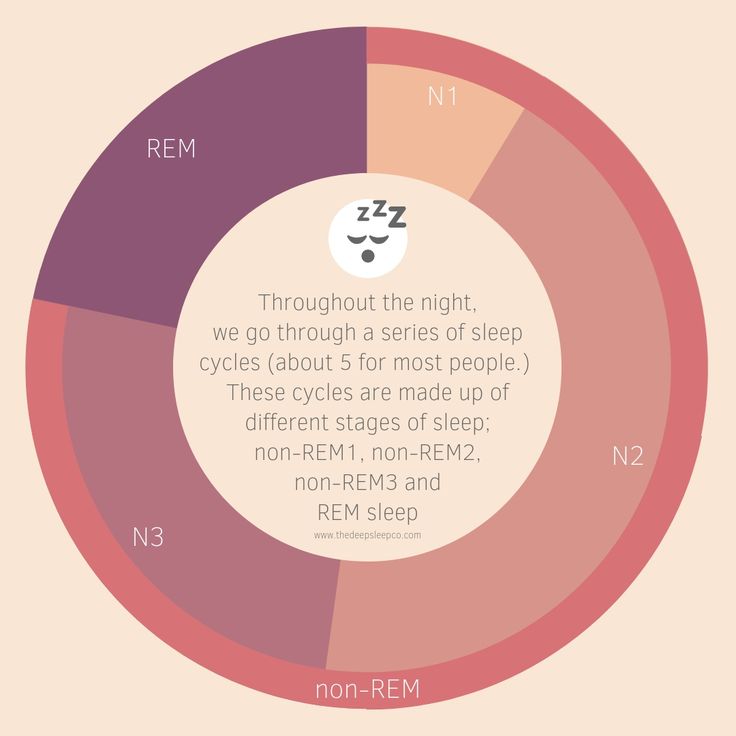

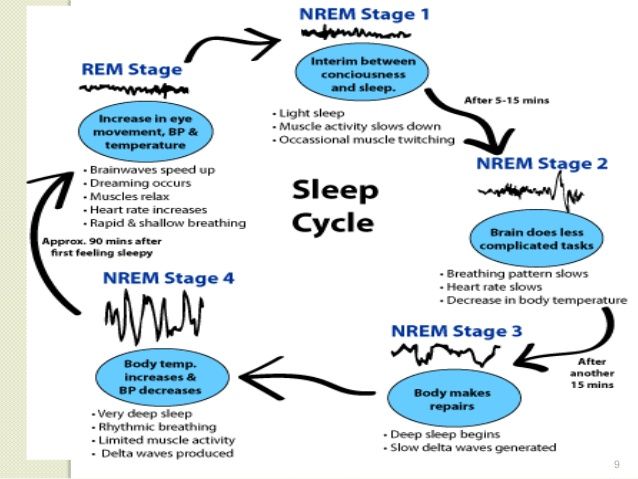

The reciprocal influence of sleep structure, emotional status and cognitive functions is well known. Each of the fundamental states of the brain — wakefulness, REM sleep — rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, and non-REM sleep — slow-wave sleep (NREM) — have their own neuroanatomical basis, neurophysiological, neurochemical characteristics, and functions [1]. A deeper understanding of the mechanisms involved in sleep-wake cycle disorders and deviant developmental variants may lead to new diagnostic and therapeutic strategies, including those at the early stages of ontogeny [2, 3].

Each of the fundamental states of the brain — wakefulness, REM sleep — rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, and non-REM sleep — slow-wave sleep (NREM) — have their own neuroanatomical basis, neurophysiological, neurochemical characteristics, and functions [1]. A deeper understanding of the mechanisms involved in sleep-wake cycle disorders and deviant developmental variants may lead to new diagnostic and therapeutic strategies, including those at the early stages of ontogeny [2, 3].

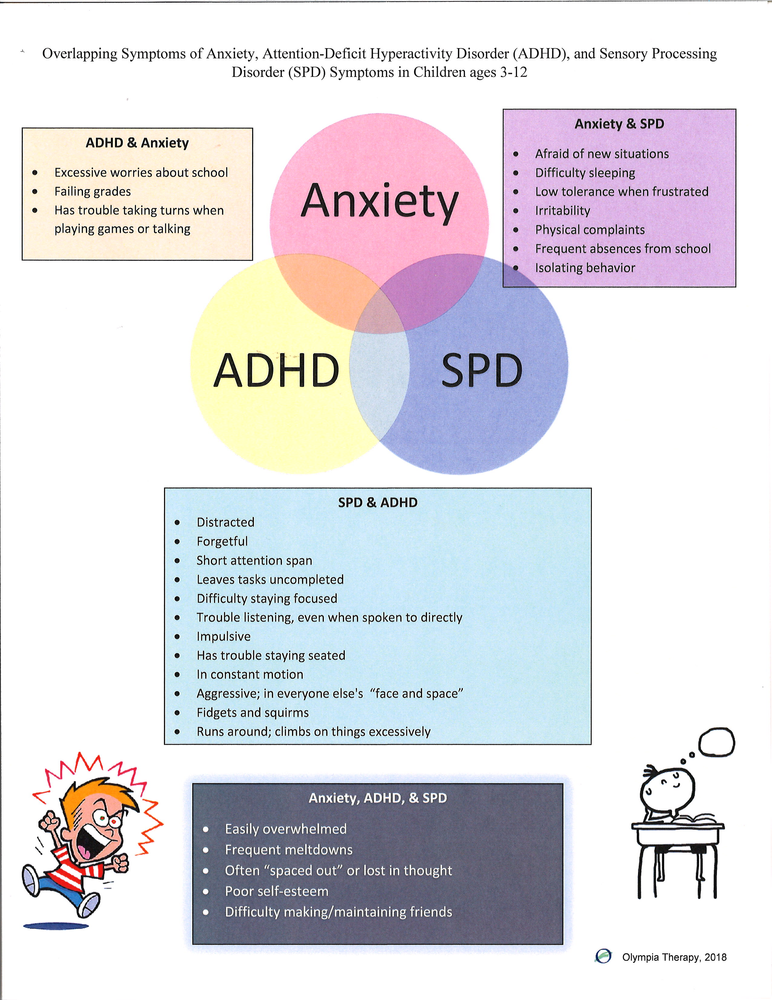

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in recent decades is considered as the most common cause of behavioral disorders, difficulties in school and social adaptation in children with normal intelligence. ADHD is heterogeneous, including several clinical variants, transforms in the process of growing up a child, has a high comorbidity with oppositional defiant behavior, anxiety and depression, tics, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Multidirectional changes in sleep in children with ADHD may be associated with the heterogeneity of clinical cases [2, 4–6]. Sleep problems occur in 25–50% of children and adolescents with ADHD [7].

Sleep problems occur in 25–50% of children and adolescents with ADHD [7].

In early attempts to define diagnostic criteria for ADHD, sleep disorders were considered as one of the possible criteria for verification of the syndrome, as reflected in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) 3rd edition. However, these data were excluded from subsequent and current editions of the DSM and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) because there was no convincing evidence that the presence of sleep disorders could be one of the criteria for diagnosing ADHD [8].

Difficulty going to sleep and prolonged falling asleep (Resistance bedtime, sleep resistance, resistance to sleep time) are the most common complaints in patients with ADHD [9]. Often, prolonged falling asleep in ADHD is regarded as the result of taking psychostimulants, and the syndrome itself is not considered as a direct cause of insomnia. However, at the present stage, this point of view is untenable [10, 11].

In the process of ontogeny, prolonged falling asleep in patients with ADHD undergoes evolution. At primary school age, 10-15% of children have difficulty getting themselves to sleep. This is 2 times more common than in healthy peers. By 12.5 years, 50% of children with ADHD have difficulty falling asleep, and by age 30, 7% of patients report spending more than 1 hour trying to fall asleep at night [12].

A significant increase in the “evening” activity type (eveningness type) was demonstrated in children with ADHD at the age of 7–12 years, which positively correlated with prolonged falling asleep and daytime sleepiness [13]. The results of 13 studies have shown that children and adolescents with a late chronotype are more likely to suffer from daytime disorders, in particular, they have a tendency to aggression [14].

Sleep initiation disorder, marked variability in sleep onset with frequent awakenings in children with ADHD belongs to the category of circadian rhythm disorders (CRSWD) and is detected in 70% of cases (compared to 20% in healthy peers). At the same time, cortical connections change and the perception of environmental signals necessary for the development of the rhythm of sleep and wakefulness is disturbed. This manifests itself in inadequate thalamic signals to the hypothalamus, the formation and aggravation of CRSWD [15, 16].

At the same time, cortical connections change and the perception of environmental signals necessary for the development of the rhythm of sleep and wakefulness is disturbed. This manifests itself in inadequate thalamic signals to the hypothalamus, the formation and aggravation of CRSWD [15, 16].

Many studies have shown that CRSWD is based on a change in the activity of the gene that regulates the circadian rhythm ( CLOCK ). There are a small number of genetic studies reporting an association between CLOCK gene polymorphisms and ADHD symptoms. Polymorphism can lead to inversion of endogenous melatonin secretion, which reaches a maximum in the daytime [17, 18].

The late chronotype in children with ADHD is associated with a delay in changes in circadian phase markers, in particular melatonin synthesis, and, as a result, a delay in the onset of sleep [10, 19].

Although genetic and/or epigenetic abnormalities in circadian sleep regulation may predispose children to CRSWD, poor sleep hygiene, negative associations, and social jet lag contribute to maintaining sleep problems [20, 21].

Thus, circadian desynchrony is an important factor mediating the proposed relationship between chronotype, circadian typology, and ADHD [22].

The features of dreams in children with ADHD are demonstrated. The content of dreams in children with ADHD is more negatively toned, including more failures, threats, negative consequences and physical aggression, which may be associated with pronounced emotional problems [9].

Anxiety during sleep is the second topical aspect of dissomnia disorders in children with ADHD. Actigraphy indicates an increase in motor activity in patients with ADHD, which is most pronounced in the combined subtype and the type with a predominance of hyperactivity [23, 24].

Sleep disturbances in children associated with ADHD include restless legs syndrome (RLS) and periodic limb movement sleep syndrome (PLMS). There is evidence of a relationship between the severity of daytime hyperactivity and the severity of RLS [2]. RLS is detected in children with ADHD in 44% of cases with a tendency to decrease with age [10]. However, the presence of RLS and PLMS cannot be fully explained by the neurobiological mechanisms of ADHD. It was assumed that RLS and PLMS are based on dopamine deficiency in the nigrostriatal system. But this requires further study. Most likely, RLS and PLMS, including those associated with ADHD, are interrelated with impaired regulation of REM sleep [25].

The importance of iron deficiency in ADHD, PLMS and RLS as a common metabolic link is also discussed. Children with ADHD have low serum ferritin [26]. This is an independent risk factor for the formation of sleep-related movement disorders, including PLMS and RLS. The change in ferritin concentration is not specific in children with ADHD. Similar changes have been found in children with autism spectrum disorders [16].

A number of studies have demonstrated excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) in children with ADHD [27]. However, the potential impact of daytime sleepiness on school performance in patients needs to be clarified. A number of studies have shown that daytime sleepiness was more correlated with emotional and behavioral problems at school than total sleep duration. However, it did not affect the average grade of students in subjects [28]. Children with a predominance of inattention have more pronounced hypersomnia and excessive daytime sleepiness than patients with other subtypes of ADHD [29].

The neurobiological mechanisms underlying ADHD and sleep regulation have much in common. Alterations in dopamine levels and norepinephrine deficiency are key neurochemical determinants of ADHD symptoms. Both neurotransmitters play a critical role in NREM-REM sleep alternation. Serotonin levels are also important. Serotonin plays a key role in switching sleep phases, and its deficiency is considered as an important neurochemical mechanism for the psychopathology of ADHD [30, 31].

In addition, there is a commonality of biochemical transformations of serotonin and melatonin. Melatonin is synthesized from the amino acid tryptophan, which is involved in the synthesis of serotonin, and it, in turn, under the influence of the enzyme serotonin-N-acetyltransferase, is converted into melatonin. Melatonin is an indole derivative of serotonin. Thus, a violation of serotonin metabolism can affect the synthesis of melatonin, and, as a result, indirectly on the quality of sleep [16].

Impaired melatonin metabolism is associated with impaired expression of a gene that affects the enzyme N-Acetylserotonin O-methyltransferase (ASMT), which catalyzes the final reaction in melatonin biosynthesis. However, the widespread use of mass media in combination with the bright screen of multimedia devices can contribute to changes in melatonin secretion [32].

Developmental disorders, including ADHD, are associated with many CYP1A2 gene polymorphisms that alter melatonin degradation. This may explain the lack of effectiveness in a number of situations when melatonin is used to correct circadian rhythms in patients [33].

Finally, orexin deficiency may also contribute to both the clinical manifestations of ADHD and sleep disturbance. Orexin neurons are "multi-tasking" neurons. There is evidence that the orexin/hypocretinergic system contributes to the maintenance of attention by increasing the release of cortical acetylcholine and modulating the activity of cortical neurons [34, 35]. Orexin neurons have connections to areas of the brain involved in cognition and mood regulation, including the hippocampus. Orexins enhance hippocampal neurogenesis and improve spatial learning and memory performance. Conversely, orexin deficiency leads to learning deficits and memory loss, as well as depression [34, 36].

Available data on the structure of sleep according to polysomnography (PSG) in patients with ADHD are rather contradictory, which may be due to different methodological factors (sample of the observation group, clinical identification of ADHD, the impact of drug therapy, the presence of comorbid conditions, adaptation to laboratory conditions and etc. ).

Changes in REM sleep are among the most common PSG changes in ADHD. Nine (64%) of 14 polysomnography reports recorded changes in REM sleep in children with ADHD [37]. Given the fundamental properties of REM sleep, this deserves focused attention. Powerful endogenous brain activation during REM sleep plays a unique role, providing stimulation-dependent development of the child's CNS, and expression of genes associated with changes in plasticity in the cortical zones occurs [1].

Changes (increase and decrease) in REM sleep have a different focus and severity in different studies [26, 37].

A lower proportion of REM sleep in children with ADHD has been associated with higher rates of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, with impaired cognitive function, including language skills and working memory [29, 38, 39].

In studies that included children aged 8 to 15-16 years with the combined subtype of ADHD, an increase in REM sleep was observed, which was associated with high levels of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. In addition, sleep in patients with ADHD may be characterized by a disturbance in the alternation of NREM and REM sleep phases [2, 37].

It is emphasized that the proportion of REM sleep in children with ADHD depends on age. Patients younger than 9-10 years of age have a reduced proportion of REM sleep compared to healthy peers. On the contrary, in children older than 9–10 years, there is an increase in REM sleep during the night [5]. Overall, the results point to an opposite effect of REM sleep on neurobehavioral functioning [28].

The authors' own research based on nocturnal PSG (without adaptation night) revealed the following features of sleep in children with ADHD aged 5–9years: a decrease in total sleep time, an increase in the latency and duration of the drowsiness stage, an increase in the latent period of REM sleep with a decrease in its duration, an increase in wakefulness during sleep, an increase in the number of awakenings, including more than 3 minutes, a decrease in the sleep efficiency index. At the same time, the level of anxiety did not affect the structure of sleep [40].

Considering that hereditary factors are considered in the pathogenesis of ADHD, it would be important to identify PSG patterns of genetic screening. However, such multilateral studies are lacking. There is one study comparing nighttime actigraphy scores and the presence of a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) for catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT). The authors demonstrated that among children with ADHD with the Val-Val SNP gene, more stable sleep indicators were recorded [41].