What is lyme rage

Aggressiveness, violence, homicidality, homicide, and Lyme disease

1. Dupuis MJ. Multiple neurologic manifestations of Borrelia burgdorferi infection. Rev Neurol (Paris) 1988;144(12):765–775. French. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Pachner AR. Borrelia burgdorferi in the nervous system: the new “great imitator” Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1988;539:56–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Gannon M. Ancient Lyme Disease Bacteria Found in 15-Million-Year-Old Tick Fossils. Live Science. 2014. [Accessed Jan 6, 2018]. Available from: https://www.livescience.com/46007-lyme-disease-ancient-amber-tick.html.

4. Kean WF, Tocchio S, Kean M, Rainsford KD. The musculoskeletal abnormalities of the Similaun Iceman (“ÖTZI”): clues to chronic pain and possible treatments. Inflammopharmacology. 2013;21(1):11–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Lyme disease. Center for Disease Control and Prevention; [Accessed Jan 6, 2018]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/index. html. [Google Scholar]

6. Fallon BA, Nields JA. Lyme disease: a neuropsychiatric illness. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(11):1571–1583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Fallon BA, Kochevar JM, Gaito A, Nields JA. The underdiagnosis of neuropsychiatric Lyme disease in children and adults. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1998;21(3):693–703. viii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Tager FA, Fallon BA, Keilp J, Rissenberg M, Jones CR, Liebowitz MR. A controlled study of cognitive deficits in children with chronic Lyme disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2001;13(4):500–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Greenberg R. The role of infection and immune responsiveness in a case of treatment-resistant pediatric bipolar disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2017;8:78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Hájek T, Pasková B, Janovská D, et al. Higher prevalence of antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi in psychiatric patients than in healthy subjects. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(2):297–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Banerjee R, Liu JJ, Minhas HM. Lyme neuroborreliosis presenting with alexithymia and suicide attempts. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(10):981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Bransfield RC. Suicide and Lyme and associated diseases. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:1575–1587. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Krug EG, Mercy JA, Dahlberg LL, Zwi AB. The world report on violence and health. Lancet. 2002;360(9339):1083–1088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Stahl SM, Morrissette DA, Munter N. Stahl’s Illustrated Violence. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

15. Lidz CW, Mulvey EP, Gardner W. The accuracy of predictions of violence to others. JAMA. 1993;269(8):1007–1011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Beck JC, White KA, Gage B. Emergency psychiatric assessment of violence. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(11):1562–1565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Tardiff K. Unusual diagnoses among violent patients. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1998;21(3):567–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1998;21(3):567–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Dugré JR, Dellazizzo L, Giguère CÉ, Potvin S, Dumais A. Persistency of cannabis use predicts violence following acute psychiatric discharge. Front Psychiatry. 2017;8:176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Lewis DO, Pincus JH, Feldman M, Jackson L, Bard B. Psychiatric, neurological, and psychoeducational characteristics of 15 death row inmates in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(7):838–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Feldman M, Mallouh K, Lewis DO. Filicidal abuse in the histories of 15 condemned murderers. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1986;14(4):345–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Freedman D, Hemenway D. Precursors of lethal violence: a death row sample. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(12):1757–1770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Bransfield RC. Why Violence? 1999. [Accessed October 20, 2017]. Available from: http://www.mentalhealthandillness.com/may1999.htm.

23. Sariaslan A, Lichtenstein P, Larsson H, Fazel S. Triggers for violent criminality in patients with psychotic disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(8):796–803. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Volavka J. Triggering violence in psychosis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(8):769–770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Mathers C. The Global Burden of Disease, 2004 Update. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

26. Homicide-world.png Wikimedia Commons. 2009. [Accessed October 16, 2017]. [updated June 8, 2014]. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Homicide-world.png.

27. US Peace Index [Accessed October 16, 2017]. Available from: http://peacealliance.org/cms/assets/uploads/2013/05/U.S.-Peace-Index-Overview.pdf.

28. Eppig C, Fincher CL, Thornhill R. Parasite prevalence and the worldwide distribution of cognitive ability. Proc Biol Sci. 2010;277(1701):3801–3808. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Lester D. Toxoplasma gondii and homicide. Psychol Rep. 2012;111(1):196–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lester D. Toxoplasma gondii and homicide. Psychol Rep. 2012;111(1):196–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Thornhill R, Fincher CL. Parasite stress promotes homicide and child maltreatment. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2011;366(1583):3466–3477. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Roser M. The Visual History of Decreasing War and Violence – Our World in Data. 2011. [Accessed October 16, 2017]. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/slides/war-and-violence/

32. Bransfield RC. Could a Pandemic Causing Mental Dysfunction Contribute to Global Instability?. Paper presented at: International Lyme and Associated Diseases 7th European Conference; May 19, 2017; Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

33. Retief FP, Wessels A. Did Adolf Hitler have syphilis? S Afr Med J. 2005;95(10):750, 752, 754, 756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Sacks O. Awakenings. New York: Harper Perennial; 1973. [Google Scholar]

35. Morton RS. Did Catherine the Great have syphilis? Genitourin Med. 1991;67:498–502. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

1991;67:498–502. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Nevins M. Meanderings in Medical History. Book Four. Bloomington, IN: iUniverse; 2016. [Google Scholar]

37. Dietz PE. Mentally disordered offenders. Patterns in the relationship between mental disorder and crime. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1992;15(3):539–551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Gómez JM, Verdú M, González-Megías A, Méndez M. The phylogenetic roots of human lethal violence. Nature. 2016;538(7624):233–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Bransfield R. Are There Psychoimmune and Infectious Contributors to Violence?. Paper presented at: New Jersey Psychiatric Association Meeting; September 21, 2016; Princeton, NJ. [Accessed Oct 1, 2017]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308549616_Are_There_Psychoimmune_and_Infectious_Contributors_to_Violence. [Google Scholar]

40. Shamay-Tsoory SG, Tomer R, Berger BD, Aharon-Peretz J. Characterization of empathy deficits following prefrontal brain damage: the role of the right ventromedial prefrontal cortex. J Cogn Neurosci. 2003;15(3):324–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Cogn Neurosci. 2003;15(3):324–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Adolphs R, Tranel D, Damasio H, Damasio A. Impaired recognition of emotion in facial expressions following bilateral damage to the human amygdala. Nature. 1994;372(6507):669–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Adolphs R, Baron-Cohen S, Tranel D. Impaired recognition of social emotions following amygdala damage. J Cogn Neurosci. 2002;14(8):1264–1274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Siever LJ. Neurobiology of aggression and violence. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(4):429–442. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Davidson RJ, Putnam KM, Larson CL. Dysfunction in the neural circuitry of emotion regulation – a possible prelude to violence. Science. 2000;289(5479):591–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Raine A, Buchsbaum M, LaCasse L. Brain abnormalities in murderers indicated by positron emission tomography. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;42(6):495–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Stahl SM. Deconstructing violence as a medical syndrome: mapping psychotic, impulsive, and predatory subtypes to malfunctioning brain circuits. CNS Spectr. 2014;19(5):357–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

CNS Spectr. 2014;19(5):357–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Ritov G, Ardi Z, Richter-Levin G. Differential activation of amygdala, dorsal and ventral hippocampus following an exposure to a reminder of underwater trauma. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Heath NM, Chesney SA, Gerhart JI, et al. Interpersonal violence, PTSD, and inflammation: potential psychogenic pathways to higher C-reactive protein levels. Cytokine. 2013;63(2):172–178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Eraly SA, Nievergelt CM, Maihofer AX, et al.Marine Resiliency Study Team Assessment of plasma C-reactive protein as a biomarker of posttraumatic stress disorder risk. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(4):423–431. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Zimmerman G, Shaltiel G, Barbash S, et al. Post-traumatic anxiety associates with failure of the innate immune receptor TLR9 to evade the pro-inflammatory NFκB pathway. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2:e78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2012;2:e78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Copeland WE, Wolke D, Lereya ST, Shanahan L, Worthman C, Costello EJ. Childhood bullying involvement predicts low-grade systemic inflammation into adulthood. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(21):7570–7575. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Bob P, Raboch J, Maes M, et al. Depression, traumatic stress and interleukin-6. J Affect Disord. 2010;120(1–3):231–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Bransfield RC. Intrusive symptoms and infectious encephalopathies. Neurol Psychiatry Brain Res. 2016;22:3–4. [Google Scholar]

54. Bransfield RC. The psychoimmunology of Lyme/tick-borne diseases and its association with neuropsychiatric symptoms. Open Neurol J. 2012;6:88–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Rosell DR, Siever LJ. The neurobiology of aggression and violence. CNS Spectr. 2015;20(3):254–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Lidberg L, Belfrage H, Bertilsson L, Evenden MM, Asberg M. Suicide attempts and impulse control disorder are related to low cerebrospinal fluid 5-HIAA in mentally disordered violent offenders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101(5):395–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Suicide attempts and impulse control disorder are related to low cerebrospinal fluid 5-HIAA in mentally disordered violent offenders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101(5):395–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Pucilowski O, Kostowski W. Aggressive behaviour and the central serotonergic systems. Behav Brain Res. 1983;9(1):33–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Virkkunen M, Goldman D, Nielsen DA, Linnoila M. Low brain serotonin turnover rate (low CSF 5-HIAA) and impulsive violence. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 1995;20(4):271–275. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. de Boer SF, Caramaschi D, Natarajan D, Koolhaas JM. The vicious cycle towards violence: focus on the negative feedback mechanisms of brain serotonin neurotransmission. Front Behav Neurosci. 2009;3:52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Coccaro EF, Lee R, Coussons-Read M. Elevated plasma inflammatory markers in individuals with intermittent explosive disorder and correlation with aggression in humans. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):158–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):158–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Hall A. Epidemic Encephalitis. (Encephalitis Lethargica) Bristol, UK: John Wright and Sons; 1924. [Google Scholar]

62. Cheyette SR, Cummings JL. Encephalitis lethargica: lessons for contemporary neuropsychiatry. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1995;7(2):125–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Mulder D, Parrott M, Thaler M. Sequelae of western equine encephalitis. Neurology. 1951;1:318–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. McMillan TM, Papadopoulos H, Cornall C, Greenwood RJ. Modification of severe behaviour problems following herpes simplex encephalitis. Brain Inj. 1990;4(4):399–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Ahokas A, Rimon R, Koskiniemi M, Vaheri A, Julkunen I, Sarna S. Viral antibodies and interferon in acute psychiatric disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48(5):194–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Anstett RE, Wood L. The patient exhibiting episodic violent behavior. J Fam Pract. 1983;16(3):605–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

1983;16(3):605–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Gamache FW, Jr, Ducker TB. Alterations in neurological function in head-injured patients experiencing major episodes of sepsis. Neurosurgery. 1982;10(4):468–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Rayel MG, Land WB, Gutheil TG. Dementia as a risk factor for homicide. J Forensic Sci. 1999;44(3):565–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Hoffman BF. Reversible neurosyphilis presenting as chronic mania. J Clin Psychiatry. 1982;43(8):338–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70. Varney NR, Roberts RJ, Springer JA, Connell SK, Wood PS. Neuropsychiatric sequelae of cerebral malaria in Vietnam veterans. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997;185(11):695–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Sowunmi AS. Psychosis after cerebral malaria in children. J Natl Med Assoc. 1993;85(9):695–696. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Bransfield RC. Did Infections Caused by World War I Contribute to Causing World War II? Contagion Live. Jan 5, 2018. [Accessed January 6, 2018]. Available from: http://www.contagionlive.com/news/did-infections-caused-by-world-war-i-contribute-to-causing-world-war-ii.

[Accessed January 6, 2018]. Available from: http://www.contagionlive.com/news/did-infections-caused-by-world-war-i-contribute-to-causing-world-war-ii.

73. Sobin A, Ozer M. Mental disorders in acute encephalitis. J Mt Sinai Hosp. 1966;33:73–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

74. Flegr J, Hrdy I. Influence of chronic toxoplasmosis on some human personality factors. Folia Parasitol (Praha) 1994;42(2):122–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

75. Flegr J, Zitkova S, Kodym P, Frynta D. Induction of changes in human behaviour by the parasitic protozoan Toxoplasma gondii. Parasitology. 1996;113(Pt 1):49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

76. Piekarski G. Behavioral alterations caused by parasitic infection in case of latent toxoplasma infection. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hgy [A] 1981;250(3):403–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

77. Caroff S, Mann S, Gliatto M, Sullivan K, Campbell E. Psychiatric manifestations of acute viral encephalitis. Psychiatr Ann. 2001;31:193–204. [Google Scholar]

78. Schlesinger LB. Sexual Murder: Catathymic and Compulsive Homicides. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

Schlesinger LB. Sexual Murder: Catathymic and Compulsive Homicides. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

79. Tselis A, Booss J. Behavioral consequences of infections of the central nervous system: with emphasis on viral infections. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2003;31(3):289–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

80. Rayel MG, Land WB, Gutheil TG. Dementia as a risk factor for homicide. J Forensic Sci. 1999;44(3):565–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

81. Bachet M. The concept of encephaloses criminogenic (criminogenic encephalosis) Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1951;21:794–799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

82. Coccaro EF, Lee R, Groer MW, Can A, Coussons-Read M, Postolache TT. Toxoplasma gondii infection: relationship with aggression in psychiatric subjects. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(3):334–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

83. Zimmer C. Parasite Rex: Inside the Bizarre World of Nature’s Most Dangerous Creatures New Ed Edition. New York, NY: Atria Publishing Group; 2000. [Google Scholar]

[Google Scholar]

84. Sergiev VP. Change of host’s behavior including man under the influence of parasites. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol. 2010;(3):108–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

85. Whitfield J. Worm turns fish antisocial. Nature. 2000. Jul 9, [Accessed October 21, 2017]. Available from: http://www.nature.com/news/1998/020708/full/news020708-3.html.

86. Winkler WG, Schneider NJ, Jennings WL. Experimental rabies infection in wild rodents. J Wildl Dis. 1972;8(1):99–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

87. Barnard CJ, Behnke JM, Sewell J. Environmental enrichment, immunocompetence, and resistance to Babesia microti in male mice. Physiol Behav. 1996;60(5):1223–1231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

88. Birkenheuer AJ, Correa MT, Levy MG, Breitschwerdt EB. Geographic distribution of babesiosis among dogs in the United States and association with dog bites: 150 cases (2000–2003) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2005;227(6):942–947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

89. Mitchell C. Dog aggression link-deer tick Lyme disease: dogs that are too aggressive to people. Leerburg Webboard. 2007. [Accessed October 16, 2017]. Available from: http://leerburg.com/webboard/thread.php?topic_id=20140.

Dog aggression link-deer tick Lyme disease: dogs that are too aggressive to people. Leerburg Webboard. 2007. [Accessed October 16, 2017]. Available from: http://leerburg.com/webboard/thread.php?topic_id=20140.

90. Goswani N. Tour of Duty Ends for Dog. Bennington Banner. 2006. Nov 28, [Accessed October 16, 2017]. Available from: http://www.benningtonbanner.com/stories/tour-of-duty-ends-for-dog,257240.

91. Bradley JM, Mascarelli PE, Trull CL, Maggi RG, Breitschwerdt EB. Bartonella henselae infections in an owner and two Papillon dogs exposed to tropical rat mites (Ornithonyssus bacoti) Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2014;14(10):703–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

92. Bishop BL, Cherry NA, Hegarty BC, Breitschwerdt EB. Enrichment blood culture isolation of Bartonella henselae from horses with chronic circulatory, musculoskeletal and/or neurologic deficits. Adv Biotech Micro. 2017;4(5) [Google Scholar]

93. CBSNews CBS/AP Chimp Shot Dead After Attacking Woman. 2009. Feb 17, [Accessed October 16, 2017]. Available from: www.cbsnews.com/news/chimp-shot-dead-after-attacking-woman.

Feb 17, [Accessed October 16, 2017]. Available from: www.cbsnews.com/news/chimp-shot-dead-after-attacking-woman.

94. Christoffersen J, Easton Robb P. Huge chimp shot dead after mauling woman in Conn. Associated Press; Feb 17, 2007. [Accessed October 16, 2017]. Available from: https://www.nhregister.com/news/article/Huge-chimp-shot-dead-after-mauling-woman-11635518.php. [Google Scholar]

95. Winslow JT, Hastings N, Carter CS, Harbaugh CR, Insel TR. A role for central vasopressin in pair bonding in monogamous prairie voles. Nature. 1993;365(6446):545–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

96. Tabbaa M, Paedae B, Liu Y, Wang Z. Neuropeptide regulation of social attachment: the prairie vole model. Compr Physiol. 2016;7(1):81–104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

97. MacLean EL, Gesquiere LR, Gruen ME, Sherman BL, Martin WL, Carter CS. Endogenous oxytocin, vasopressin, and aggression in domestic dogs. Front Psychol. 2017;8:161327. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

98. Heinrichs M, Domes G. Neuropeptides and social behaviour: effects of oxytocin and vasopressin in humans. Prog Brain Res. 2008;170:337–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Heinrichs M, Domes G. Neuropeptides and social behaviour: effects of oxytocin and vasopressin in humans. Prog Brain Res. 2008;170:337–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

99. Keverne EB, Kendrick KM. Maternal behaviour in sheep and its neuroendocrine regulation. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 1994;397:47–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

100. Schmelkin C, Plessow F, Thomas JJ, et al. Low oxytocin levels are related to alexithymia in anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(11):1332–1338. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

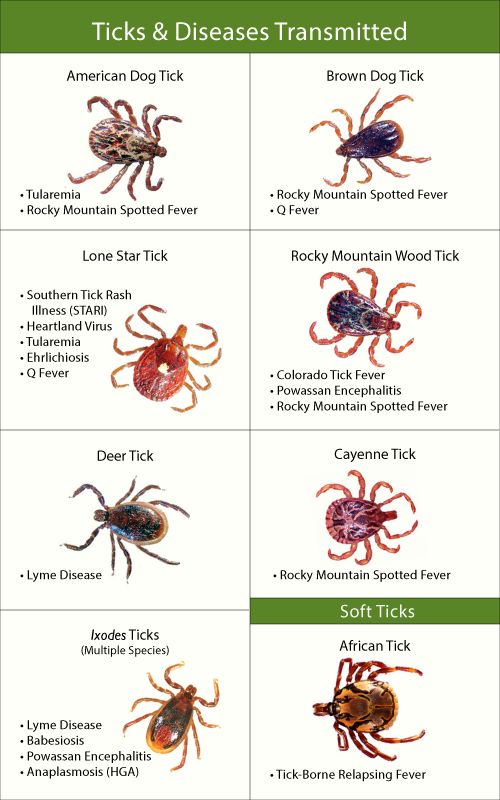

101. Norman MU, Moriarty TJ, Dresser AR, Millen B, Kubes P, Chaconas G. Molecular mechanisms involved in vascular interactions of the Lyme disease pathogen in a living host. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(10):e1000169. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

102. Moriarty TJ, Norman MU, Colarusso P, Bankhead T, Kubes P, Chaconas G. Real-time high resolution 3D imaging of the Lyme disease spirochete adhering to and escaping from the vasculature of a living host. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(6):e1000090. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(6):e1000090. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

103. Kandel ER, Schwartz JH, Jessell TM. Principles of Neural Science. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Health Professions Division; 2000. [Google Scholar]

104. Rhee H, Cameron DJ. Lyme disease and pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS): an overview. In J Gen Med. 2012;5:163–174. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

105. Barnett EM, Jacobsen G, Evans G, Cassell M, Perlman S. Herpes simplex encephalitis in the temporal cortex and limbic system after trigeminal nerve inoculation. J Infect Dis. 1994;169(4):782–786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

106. Johnson L, Wilcox S, Mankoff J, Stricker RB. Severity of chronic Lyme disease compared to other chronic conditions: a quality of life survey. PeerJ. 2014;2:e322. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

107. Sperling J, Middelveen M, Klein D, Sperling F. Evolving perspectives on Lyme borreliosis in Canada. Open Neurol J. 2012;6:94–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Open Neurol J. 2012;6:94–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

108. Logigian EL, Kaplan RF, Steere AC. Chronic neurologic manifestations of Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 1990;323(21):1438–1444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

109. Harvey R, Misselbeck W, Uphold R. Cat-scratch disease: an unusual cause of combative behavior. Am J Emerg Med. 1991;9:52–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

110. Dee JE. Ax attacker using Lyme disease as defense case intensifies debate over ailment’s effects on brain. Courant. 1999 Jan 17; [Google Scholar]

111. Fallon BA, Nields JA, Burrascano JJ, Liegner K, DelBene D, Liebowitz MR. The neuropsychiatric manifestations of Lyme borreliosis. Psychiatr Q. 1992;63(1):95–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

112. Sherr VT. Spotlight on Lyme. Lyme Alliance Inc; Concord, MI, USA: Jun, 1998. Letter to Editor. [Google Scholar]

113. Bransfield RC. Aggression and Lyme disease. Spotlight. 1998. Jun, [Accessed October 21, 2017]. Available from: http://www. thedogplace.org/health/aggression-lyme-disease-1608-bansfield-md.asp.

thedogplace.org/health/aggression-lyme-disease-1608-bansfield-md.asp.

114. Staff “I fear for my friends’ and for my family’s safety”: Palin wins restraining order against teenage stalker (and his dad) Daily Mail. 2012. Dec 12, [Accessed October 21, 2017]. Available from: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1385553/Sarah-Palin-wins-restraining-order-teenage-stalker-Shawn-Christy-dad.html#ixzz4wAYLzGST.

115. Howell T. Depraved’ mom gets five years. New Jersey Herald. 2009. Apr 16, [Accessed October 21, 2017]. Available from: http://www.njherald.com/article/20090416/ARTICLE/304169997#.

116. Cutroni L. Tusten resident surrenders after shooting at police. The River Reporter. 2006. Feb 2, [Accessed October 21, 2017]. Available from: http://www.riverreporter.com/issues/06-02-02/news-tusten.html.

117. Greenstein T. Down for the count. Chicago Tribune. 2000. Feb 13, [Accessed October 21, 2017]. Available from: http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2000-02-13/sports/0002130275_1_casino-industry-art-collection-afterglow/2.

118. Fallon BD, Schwartzenberg M, Bransfield R, et al. Late stage neuropsychiatric Lyme borreliosis. Psychosomatics. 1995;36(3):295–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

119. Bransfield RC. The Many Faces of Lyme: Neuropsychiatric Lyme Disease Case Presentations. Paper presented at: Neuropsychiatric Lyme Disease Symposium, 149th Annual Meeting; May 9, 1996; New York, NY. American Psychiatric Association; [Google Scholar]

120. Bransfield RC. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease. JAMA. 1998;280(12):1049. Author reply 1051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

121. Bransfield RC, Fallon BA, Raxlen BD, Shepler LT, Sherr VT. A modest proposal. Psychiatric News. 1998;33:18(18):16. [Google Scholar]

122. Bransfield RC, Fallon BA. Microbes and Mental Illness, Neuropsychiatric Features of Lyme Disease. Papers presented at: Microbes and Mental Illness Symposium, American Psychiatric Association Institute on Psychiatric Services Meeting; October 25, 2000; Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

[Google Scholar]

123. Bransfield R. Lyme neuroborreliosis and aggression. Paper presented at: 14th International Scientific Conference on Lyme Disease and Other Tick-Borne Disorder; April 22; 2001; Hartford, CT. [Accessed October 21, 2017]. Available from: https://sites.google.com/site/marylandlyme/symptoms-information/mental-health-issues/lyme-neuroborreliosis-agression-dr-bransfield. [Google Scholar]

124. Bransfield RC. Posttraumatic stress disorder and infectious encephalopathies. Spotlight. 2001. Nov-Dec. [Accessed October 21, 2017]. Available from: http://www.mentalhealthandillness.com/Articles/PosttraumaticStressDisorder.htm.

125. Bär KJ, Jochum T, Häger F, Meissner W, Sauer H. Painful hallucinations and somatic delusions in a patient with the possible diagnosis of neuroborreliosis. Clin J Pain. 2005;21(4):362–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

126. Schaller JL, Burkland GA, Langhoff PJ. Do bartonella infections cause agitation, panic disorder, and treatment-resistant depression? MedGenMed. 2007;9(3):54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2007;9(3):54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

127. Bransfield R. Can infections and immune reactions to them cause violent behavior?. Paper presented at: International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society Neurological/Psychiatric Lyme Disease Conference; October 29, 2011; Toronto, Canada. [Accessed October 19, 2017]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UI3Yap1Kgmo. [Google Scholar]

128. Bransfield RC. Can infections and immune reactions to them cause violent behavior? Neurol Psychiatry Brain Res. 2012;18(3):42. [Google Scholar]

129. Bransfield RC. The role of brain mechanisms in intrusive symptoms and post-traumatic stress disorders. Paper presented at: International Lyme and Associated Diseases Annual Conference; October 10, 2014; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

130. Bransfield RC. Chronic infections as aetiological factors in psychiatric disorders. Paper presented at: 21st Annual International Integrative Medicine Conference; July 19, 2015; Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar]

[Google Scholar]

131. Breitschwerdt EB, Mascarelli PE, Schweickert LA, et al. Hallucinations, sensory neuropathy, and peripheral visual deficits in a young woman infected with Bartonella koehlerae. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(9):3415–3417. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

132. Munir A, Aadil M, Rehan Khan A. Suicidal and homicidal tendencies after Lyme disease: an ignored problem. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:2069–2071. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

133. Bransfield RC. Response to Letter to Editor Suicidal and homicidal tendencies after Lyme disease: an ignored problem. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:2071. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

134. Fink PJ. Another great imposter. Philadelphia Medicine. 1999 Jun [Google Scholar]

135. Fink PJ. Another great imposter. Clinical Psychiatry News. 1999 Mar [Google Scholar]

136. Langhoff PJ. Recognizing the face of rage in tick-borne illness. [Accessed October 20, 2017];Public Health Alert. 2007 2(8):4–9. Available from: http://www.betterhealthguy.com/images/stories/PDF/PHA/2007_08.pdf. [Google Scholar]

2007 2(8):4–9. Available from: http://www.betterhealthguy.com/images/stories/PDF/PHA/2007_08.pdf. [Google Scholar]

137. Bransfield R. Can infections and immune reactions to them cause violent behavior?. Paper presented at: International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society Neurological/Psychiatric Lyme Disease Conference; October 29, 2011; Toronto, Canada. [Accessed October 19, 2017]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UI3Yap1Kgmo. [Google Scholar]

138. Bransfield RC. Antimicrobials in psychiatry. Psychiatric Times. 1999 Jul [Google Scholar]

139. Singley P. Lawyer: Southbury strangling sparked by Lyme disease or drugs. Republican-American. 2006. Feb 9, [Accessed October 20, 2017]. Available from: http://www.lymeblog.com/modules.php?name=News&file=article&sid=390.

140. Appellate Court of Connecticut Gregg Madigosky v. Commissioner of Correction (AC 38962) Decided: 2017 April 11. [Accessed October 20, 2017]. Available from: http://caselaw. findlaw.com/ct-court-of-appeals/1855564.html.

findlaw.com/ct-court-of-appeals/1855564.html.

141. Weir R. Librarian savagely beaten while sleeping in her West Islip home. Son held in slay of Mom. New York Daily News. 2006. Oct 10, [Accessed October 20, 2017]. Available from: http://www.nydailynews.com/archives/boroughs/librarian-savagely-beaten-sleeping-west-islip-home-son-held-slay-mom-article-1.645217.

142. Miller AL. Two dead in murder-suicide had advanced Lyme disease. Ocala Star Banner. 2010. Jul 10, [Accessed October 20, 2017]. Available from: http://www.ocala.com/article/LK/20100710/News/604190440/OS/

143. McQuiston JT. Man Pleads Not Guilty in Slaying on Shelter I. The New York Times. 2008. May 7, [Accessed October 20, 2017]. Available from: http://www.nytimes.com/1998/05/07/nyregion/man-pleads-not-guilty-in-slaying-on-shelter-i.html?mcubz=3.

144. McQuiston JT. Fear, Not Anger, Led to Shelter Island Slaying, Defense Says. The New York Times. 2000. May 23, [Accessed October 20, 2017]. Available from: http://www. nytimes.com/2000/05/23/nyregion/fear-not-anger-led-to-shelter-island-slaying-defense-says.html?mcubz=3.

nytimes.com/2000/05/23/nyregion/fear-not-anger-led-to-shelter-island-slaying-defense-says.html?mcubz=3.

145. Wacker T. Lyme made him do it? Lyme psychosis eyed as defense in S.I. Shooting. The Suffolk Times. 1998 May 14; [Google Scholar]

146. Bernstein J. Did Adam Lanza have Lyme disease? Counterpunch. 2013. Jan 11, [Accessed October 20, 2017]. Available from: https://www.counterpunch.org/2013/01/11/did-adam-lanza-have-lyme-disease/

147. Abrahams Wilson A. Under Our Skin 2: Emergence. [Accessed October 20, 2017]. Available from: http://underourskin.com/emergence/

148. Altimari D. Full Report Confirms No Drugs, Alcohol in Lanza’s System. The Hartford Courant. Oct 29, 2013. [Accessed October 20, 2017]. Available from: http://articles.courant.com/2013-10-29/news/hc-sandy-hook-lanza-toxicology-20131029_1_peter-lanza-adam-lanza-toxicology-report.

149. Staff The tick defense. New Jersey Law Journal. 1999;155NJLJ(1331):3. [Google Scholar]

150. Fritz M. Foreboding at Ground Zero of Lyme Disease. LA Times. 1998. Jun 7, [Accessed October 21, 2017]. Available from: http://articles.latimes.com/1998/jun/07/news/mn-57486/2.

Foreboding at Ground Zero of Lyme Disease. LA Times. 1998. Jun 7, [Accessed October 21, 2017]. Available from: http://articles.latimes.com/1998/jun/07/news/mn-57486/2.

151. Viviano J. Defense blames Lyme disease in ax attack. Register. 2001. Jan 26, [Accessed October 20, 2017]. Available from: https://groups.google.com/forum/#!topic/sci.med.diseases.lyme/9Q3813YOx70.

152. Staff Woman pleads guilty to fatal fire. Times Free Press. 2010. Dec 11, [Accessed October 20, 2017]. Available from: http://www.timesfreepress.com/news/news/story/2010/dec/11/woman-pleads-guilty-to-fatal-fire/36780/

153. Staff NY follow-up letter, Dr. Bransfield connects Lyme to opioid crisis 2017 Sept 6. LymeDisease.org. [Accessed October 20, 2017]. Available from: https://www.lymedisease.org/bransfield-lyme-opioid-crisis/?utm_source=sept+9-sleeper&utm_campaign=sept+5-sleeper+cells&utm_medium=email.

154. Shea LJ. The Neuropsychology of Lyme Disease. Paper presented at: Challenges and Controversy in Lyme Disease and Tick-Borne Illness Care Symposium; November 9, 2013; Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

[Google Scholar]

155. Blair RJ. The amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex: functional contributions and dysfunction in psychopathy. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363(1503):2557–2565. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

156. Blair RJ. The Neurobiology of Impulsive Aggression. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016;26(1):4–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

157. Lee R, Arfanakis K, Evia AM, Fanning J, Keedy S, Coccaro EF. White matter integrity reductions in intermittent explosive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41(11):2697–2703. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

158. Shraberg D, Weisberg L. The Klüver-Bucy syndrome in man. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1978;166(2):130–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

159. Morana HC, Stone MH, Abdalla-Filho E. Transtornos de person-alidade, psicopatia e serial killers. [Personality disorders, psychopathy and serial killers] Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2006;28(2):74–79. Portuguese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

160. Jha KK, Singh SK, Kumar P, Arora CD. Partial Kluver-Bucy syndrome secondary to tubercular meningitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;16:2016. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jha KK, Singh SK, Kumar P, Arora CD. Partial Kluver-Bucy syndrome secondary to tubercular meningitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;16:2016. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

161. Oumerzouk J, Mouhadi KK, Hssaini Y, et al. Klüver-Bucy syndrome complicating herpes meningoencephalitis in a pregnant woman. Presse Med. 2014;43(7–8):871–874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

162. Eikmeier G, Forquignon I, Honig H. Klüver-Bucy syndrome after herpes simplex encephalitis. Psychiatr Prax. 2013;40(7):392–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

163. Bransfield RC, Wulfman JS, Harvey WT, Usman AI. The association between tick-borne infections, Lyme borreliosis and autism spectrum disorders. Med Hypotheses. 2008;70(5):967–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

164. Daxboeck F. Mycoplasma pneumoniae central nervous system infections. Curr Opin Neurol. 2006;19(4):374–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

165. Auvichayapat N, Auvichayapat P, Watanatorn J, Thamaroj J, Jitpimolmard S. Kluver-Bucy syndrome after mycoplasmal bronchitis. Epilepsy Behav. 2006;8(1):320–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Epilepsy Behav. 2006;8(1):320–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

166. Patel R, Jha S, Yadav RK. Pleomorphism of the clinical manifestations of neurocysticercosis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006;100(2):134–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

167. De Tiège X, De Laet C, Mazoin N. Postinfectious immune-mediated encephalitis after pediatric herpes simplex encephalitis. Brain Dev. 2005;27(4):304–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

168. Locatelli C, Vergine G, Ciambra R. Kluver Bucy syndrome and central diabetes insipidus: two uncommon complications of herpes simplex encephalitis. Pediatr Med Chir. 2003;25(6):442–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

169. Mancini J, Chabrol B, Livet MO, Pinsard N. Résultat de l’encéphalite herpétique. À propos de 10 cas. [Outcome of herpetic encephalitis. Apropos of 10 cases] Ann Pediatr (Paris) 1991;38(3):143–149. French. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

170. Hart RP, Kwentus JA, Frazier RB, Hormel TL. Natural history of Klüver-Bucy syndrome after treated herpes encephalitis. South Med J. 1986;79(11):1376–1378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

South Med J. 1986;79(11):1376–1378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

171. Webster J, Lamberton PH, Donnelly C, Torrey E. Parasites as causative agents of human affective disorders? The impact of anti-psychotic, mood-stabilizer and anti-parasite medication on Toxoplasma gondii’s ability to alter host behaviour. Proc Roy Soc B Biol Sc. 2006;273(1589):1023–1030. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

172. Carroll JE, Low CA, Prather AA, et al. Negative affective responses to a speech task predict changes in interleukin (IL)-6. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25:232–238. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

173. Westling S, Ahrén B, Träskman-Bendz L, Brundin L. Increased IL-1β reactivity upon a glucose challenge in patients with deliberate self-harm. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;124(4):301–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

174. Sergiev VP. Change of host’s behavior including man under the influence of parasites. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol. 2010;(3):108–114. Russian. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

175. Constant A, Castera L, Dantzer R, et al. Mood alterations during interferon-alfa therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C: evidence for an overlap between manic/hypomanic and depressive symptoms. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(8):1050–1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

176. Lotrich FE, Sears B, McNamara RK. Anger induced by interferon-alpha is moderated by ratio of arachidonic acid to omega-3 fatty acids. J Psychosom Res. 2013;75(5):475–483. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

177. Chantal Henry C, Laurent Castéra L, Demotes-Mainard J. Hepatitis C and interferon: Watch for hostility, impulsivity. Curr Psychiatr. 2006;5(8):71–77. [Google Scholar]

178. Kleinsasser BJ, Misra LK, Bhatara VS, Sanchez JD. Risperidone in the treatment of choreiform movements and aggressiveness in a child with “PANDAS” S D J Med. 1999;52(9):345–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

179. Tillman JA, Raff GJ. Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis cured with resection of an adnexal mass. JSLS. 2009;13(3):433435. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

JSLS. 2009;13(3):433435. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

180. Khan N, Wieser HG. Limbic encephalitis: a case report. Epilepsy Res. 1994;17(2):175–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

181. Venâncio P, Brito MJ, Pereira G, Vieira JP. Anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis with positive serum antithyroid antibodies, IgM antibodies against mycoplasma pneumoniae and human herpesvirus 7 PCR in the CSF. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33(8):882–883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

182. Frohman EM, Frohman TC, Moreault AM. Acquired sexual paraphilia in patients with multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2002;59(6):1006–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

183. Bransfield RC. A structured clinical interview when neuropsychiatric Lyme disease is a possibility. Paper presented at: LDF’s 10th Annual International Scientific Conference on Lyme Borrelosis and Other Tick-borne Disorders; April 28, 1997; Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

184. Citera M, Freeman PR, Horowitz RI. Empirical validation of the Horowitz Multiple Systemic Infectious Disease Syndrome Questionnaire for suspected Lyme disease. Int J Gen Med. 2017;10:249–273. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Int J Gen Med. 2017;10:249–273. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

185. AHRQ National Guideline Clearinghouse. 2016. [Accessed April 30, 2017]. Available from: https://www.guideline.gov.

186. Cameron DJ, Johnson LB, Maloney EL. Evidence assessments and guideline recommendations in Lyme disease: the clinical management of known tick bites, erythema migrans rashes and persistent disease. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2014;12(9):1103–1135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

187. The American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines for the psychiatric evaluation of adults. Third edition. 2016. [Accessed March 3, 2017]. Available from: http://psychiatryonline.org/doi/pdf/10.1176/appi.books.9780890426760.

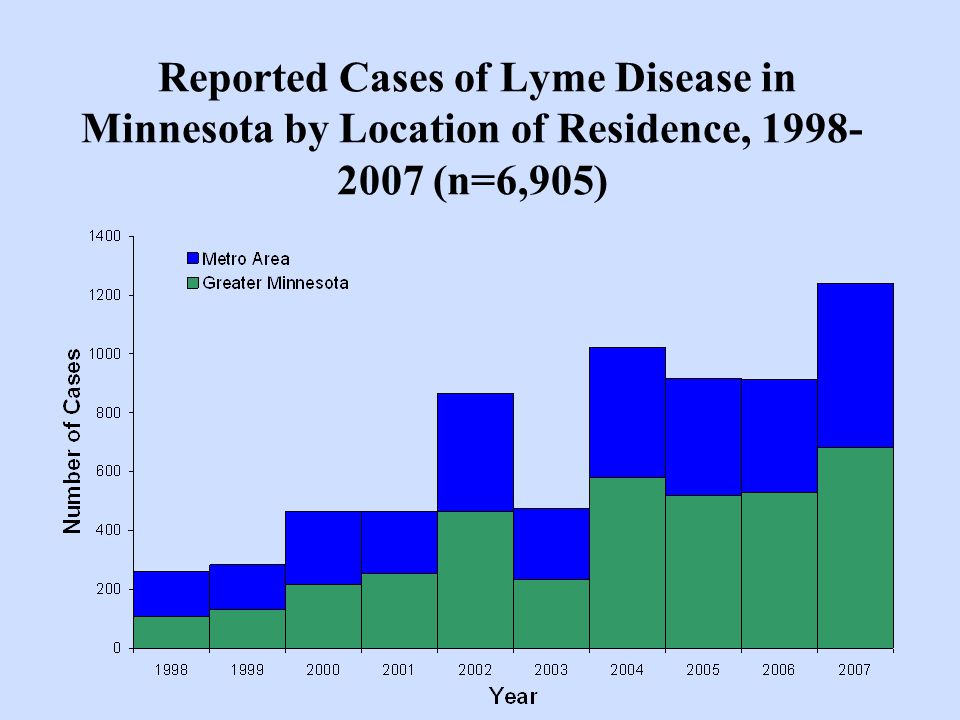

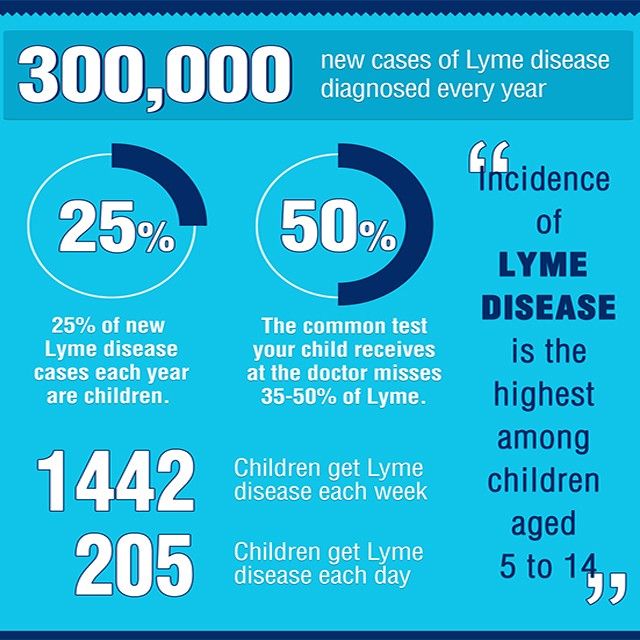

188. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention How many people get Lyme disease? 2015. [Accessed October 20, 2017]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/stats/humancases.html.

189. Glista K, Moran D. Murder-suicide of Durham couple shakes community. Hartford Courant. 2015. [Accessed October 20, 2017]. Available from: http://www.courant.com/breaking-news/hc-durham-murder-suicide-0319-20150318-story.html.

Hartford Courant. 2015. [Accessed October 20, 2017]. Available from: http://www.courant.com/breaking-news/hc-durham-murder-suicide-0319-20150318-story.html.

190. Enchassi NJ. Tribune Media Wire and CNN Wire. DA: Pennsylvania dad of heart-transplant toddler killed family, self. 2016. [Accessed October 21, 2017]. Available from http://kfor.com/2016/08/15/pennsylvania-dad-of-heart-transplant-toddler-killed-family-self-da/

191. Salvatore P, Bhuvaneswar C, Tohen M, Khalsa HM, Maggini C, Baldessarini RJ. Capgras’ syndrome in first-episode psychotic disorders. Psychopathology. 2014;47(4):261–269. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

192. Goodman RA, Mercy JA, Loya F, et al. Alcohol use and interpersonal violence: alcohol detected in homicide victims. Am J Public Health. 1986;76(2):144–149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

193. Frank C. On the reception of the concept of the death drive in Germany: expressing and resisting an ‘evil principle’? Int J Psychoanal. 2015;96(2):425–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2015;96(2):425–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rage, Extreme Irritability, and Lyme disease

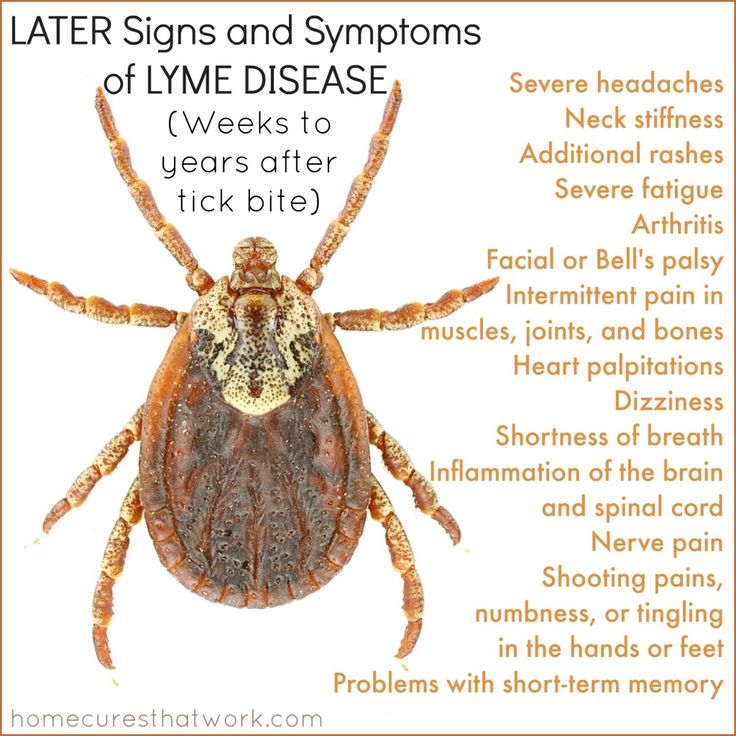

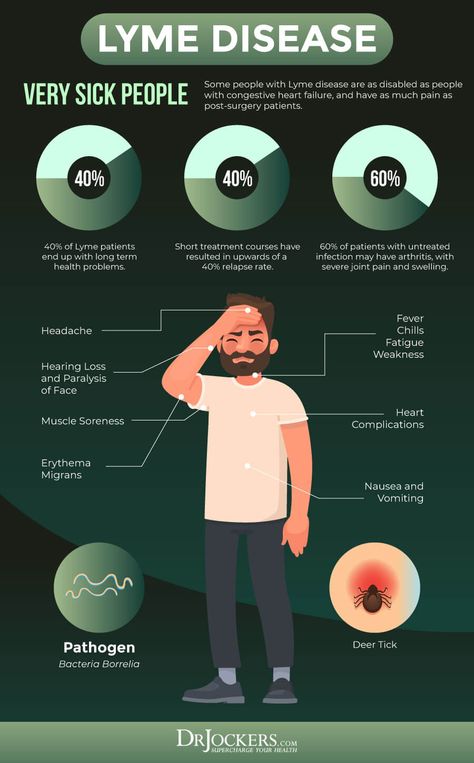

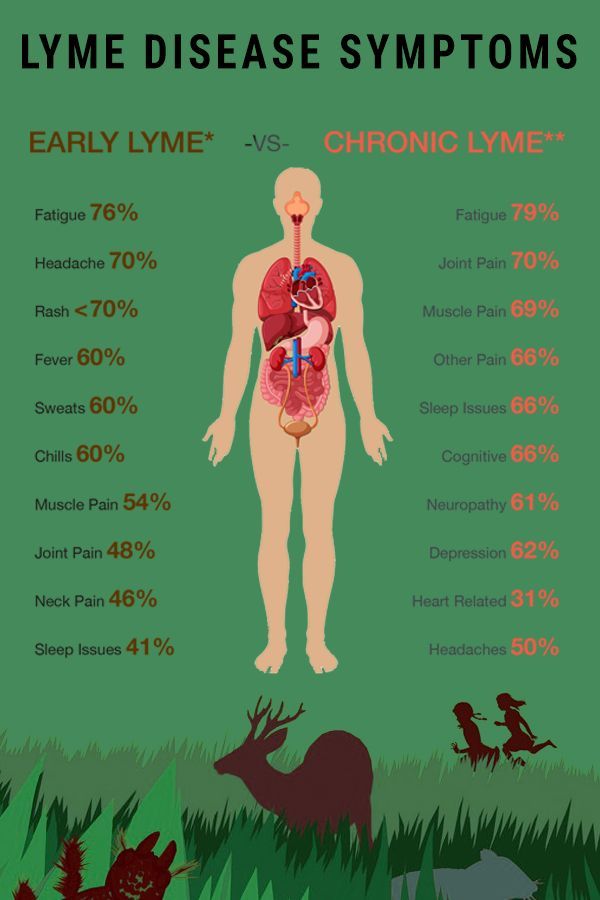

Most chronic neurologic Lyme patients presented with mild encephalopathy consisting of memory loss, depression, sleep disturbance, irritability, and difficulty finding words. “They forgot names, missed appointments, or misplaced objects. To compensate they made daily lists. Ten patients had symptoms of depression, and three of them sought psychiatric help or received antidepressant medication. Eight patients had excessive daytime sleepiness and seven had extreme irritability. They became angry over circumstances that previously caused minor annoyance. Finally, five patients had subtle symptoms of a language disturbance, with difficulty finding words. 1

The researchers conducted a second study, reproducing the chronic manifestations in a case series of 18 patients who met strict criteria for Lyme encephalopathy.68 The most common symptoms were memory loss, minor depression, somnolence, headache, irritability, hearing loss/tinnitus, and neuropathy. They also found the chronic patients’ recovery differed depending on length of treatment. The 18 Lyme encephalopathy patients were treated twice as long as the chronic neurologic Lyme patients (one month vs. two weeks), and 50 percent had “greatly improved” on follow-up. Two (11 percent) were somewhat improved on follow-up. 2

They also found the chronic patients’ recovery differed depending on length of treatment. The 18 Lyme encephalopathy patients were treated twice as long as the chronic neurologic Lyme patients (one month vs. two weeks), and 50 percent had “greatly improved” on follow-up. Two (11 percent) were somewhat improved on follow-up. 2

“The depression associated with the earlier encephalitic phase of neurologic Lyme disease is characterized by marked irritability and mood lability. Later, in the setting of encephalopathy, the depression is often more mild, characterized primarily by anhedonia, low energy, hopelessness regarding the future, and a diminished sex drive.” 3

In this case, during an initial consult with a neuropsychologist, 7-year-old Susan was diagnosed with attention deficit disorder because she had problems focusing on school work. Yet, she lived in a Lyme endemic area and had an array of other symptoms including:

lethargy

irritability

forgetfulness

headaches

poor coordination

joint pain

word-finding difficulties

light and sound sensitivity

The first infant, a 4 1/2-week-old male, presented with a fever of 101. 7, sleepiness and periodic irritability. His mother had been diagnosed with Lyme disease during her third trimester at 32 weeks’ gestation. She presented with an erythema migrans rash and was treated successfully with amoxicillin. 4

7, sleepiness and periodic irritability. His mother had been diagnosed with Lyme disease during her third trimester at 32 weeks’ gestation. She presented with an erythema migrans rash and was treated successfully with amoxicillin. 4

Logigian EL, Kaplan RF, Steere AC. Chronic neurologic manifestations of Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 1990;323(21):1438-1444.

Logigian EL, Kaplan RF, Steere AC. Successful treatment of Lyme encephalopathy with intravenous ceftriaxone. J Infect Dis. 1999;180(2):377-383.

Fallon BA, Kochevar JM, Gaito A, Nields JA. The underdiagnosis of neuropsychiatric Lyme disease in children and adults. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1998;21(3):693-703, viii.

Saetre K, Godhwani N, Maria M, et al. Congenital Babesiosis After Maternal Infection With Borrelia burgdorferi and Babesia microti. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc.

fruit punch rage or lemon lime - the effectiveness of the drug, description and composition

About the projectHow it worksAbout evidence-based medicineFeedback

About the projectHow it worksAbout evidence-based medicineFeedback

The drug does not have proven effectiveness

Dietary supplement 9010 20003 is a biologically active additive (BAA). Dietary supplements "cannot be used to treat any disease, as they are not medicines." nine0003

Dietary supplements "cannot be used to treat any disease, as they are not medicines." nine0003

This is due to different requirements for state registration, as for dietary supplements they are significantly lower than for drugs. Therefore, taking dietary supplements as a medicine or instead of a medicine is unacceptable, even if they contain the same active ingredient.

It is undeniable that dietary supplements have an effect on the body, however, we do not evaluate the proven effectiveness of supplements, because. these products are not drugs. Furthermore, the medicinal ingredients in dietary supplements “may cause serious adverse health effects through accidental misuse, overuse, or interactions with other drugs, underlying health conditions, or other pharmaceuticals in the supplement formulation.” Supplementation brings 23,000 Americans to the emergency room a year, and 2,000 more need to be hospitalized. nine0003

Rospotrebnadzor plans to ban dietary supplements whose names are similar to or very similar to drug names.

Report an error

Report an error

How the effectiveness of the drug is evaluated

- Understand which active substance of the drug should be analyzed

- Search for meta-analyses and randomized clinical trials on the active substance in international databases

- Draw conclusions Based on the amount of data collected about the proven efficacy of the drug

Scientific approach to drug selection

Evidence-based medicine is the most advanced method of clinical practice used today in all developed countries.

A doctor who uses the principles of evidence-based medicine in everyday clinical practice, makes decisions based not on personal experience or the experience of colleagues, will prescribe to the patient only those drugs that have been tested by clinical trials, that is, their effectiveness has been proven.

The meaning of evidence-based medicineInternational drug and clinical research databases

-

Worldwide database of medical publications with more than 28 million articles

-

Global independent database of medical research with 37,000 scientists from more than 130 countries

Key U. -

World Health Organization Essential Medicines List: WHO Essential Medicines List

S. online resource for originator and generic drugs

S. online resource for originator and generic drugs The drug is proven effective only when there are positive results from clinical trials with a high level of evidence

Why is this so?

Questions and Answers

How is the proven effectiveness of a medicinal product determined?

According to the principles of evidence-based medicine, the drug is considered effective only in the presence of positive results of clinical studies with a high level of evidence. The effectiveness of a drug that has even a huge number of studies of a lower level cannot be considered proven. nine0003

How are high-quality clinical trials conducted for drugs?

In randomized controlled trials (RCTs), participants are randomly assigned to groups. Some patients fall into the experimental group, while others fall into the control group. Both groups are followed for a certain period of time and analyze the outcomes formulated at the beginning of the study. The effectiveness of treatment is evaluated in comparison with the control group.

Both groups are followed for a certain period of time and analyze the outcomes formulated at the beginning of the study. The effectiveness of treatment is evaluated in comparison with the control group.

An analysis of the combined results of several RCTs is called a meta-analysis. By increasing the sample size in a meta-analysis, more statistical power is provided, and, therefore, the accuracy of assessing the effect of the analyzed intervention.

What is the therapeutic efficacy of drugs?

It is worth separating the concepts of proven efficacy and therapeutic efficacy of drugs. Therapeutic efficacy is the ability to produce an effect (for example, lowering blood pressure), proven efficacy reliably confirms therapeutic efficacy. Thus, in theory, a drug may have therapeutic efficacy without having proven efficacy. nine0003

What are the criteria for assessing the proven efficacy of a drug in the MedIQ project?

We use the world's largest and most reliable databases of drugs and clinical trials as criteria for assessing proven efficacy. An example is the List of Essential Medicines of the World Health Organization. Any drug included in this list is vital for the treatment of various diseases, proven by numerous clinical studies. nine0003

An example is the List of Essential Medicines of the World Health Organization. Any drug included in this list is vital for the treatment of various diseases, proven by numerous clinical studies. nine0003

If a drug has no studies, but it works for me, is it proven to work?

According to the principles of evidence-based medicine, a drug can be considered proven effective only if there are positive results from clinical studies of a high level of evidence. Your personal experience or the unconfirmed opinion of a doctor cannot be evidence.

I do not trust the results of your analysis. How can I check them?

The MedIQ evidence-based system is transparent, each user can check which active substance is analyzed and study the results of studies for each criterion. If you find an error, be sure to let us know. nine0003

Can I use MedIQ test results without consulting a doctor?

The information posted on the site https://mediqlab.com/ is for reference only and cannot be the basis for self-diagnosis and self-treatment. Only a specialist doctor can prescribe the correct treatment in each specific situation

Only a specialist doctor can prescribe the correct treatment in each specific situation

Feedback

We will be grateful for any comment about our service.

Fury - Official TF2 Wiki

From Team Fortress Wiki

< Anger

Ng, ahhhh...

— Sniper furious

Fury is a promotional cosmetic item for the Sniper. It is a team-colored hood with a brown veil attached. It is similar to the look of the Fury set worn by the Resistance members in game Brink .

Genuine item was awarded to players who purchased Brink before August 8, 2011.

Later, a unique quality Rage was awarded to all players who purchased Quakecon Bundle before August 6, 2012.

Contents

- 1 Painting options

- 2 Previous changes

- 3 Facts

- 4 Gallery

- 5 See also

Painting options

Main article: Can of paint

Move your mouse over the image to see how it looks on a dark background. Click on the image to enlarge it.

Click on the image to enlarge it.

| Huge variety of shades | Color #216-190-216 | Strange shade of gray | Gray barbel |

|---|---|---|---|

| nine0112 | |||

| Severe lack of color | Midnight chocolate | Brown by Radigan Conagher | Old coarse color |

| Muscular brown | Mann Co. Orange Orange | Gold australium | Gentleman pants color |

| nine0235 | |||

| Dark Salmon Injustice | Incredible pink | Purple addiction | Noble violet |

| Some slate gray | Zepheniah's Greed | Dull olive | True green |

| Bitter taste of defeat and lime nine0180 | Manna Greens | ||

| Wet lab coat (bovine) | Wet Lab Coat (BLU) | Balaclavas forever (KRS) | Balaclavas forever (BLU) |

| Team spirit (KRS) | Team Spirit (BLU) | Worker overalls (cattle) | nine0179 Worker overalls (BLU)|

| Team play value (KRS) | Team play value (BLV) | Atmosphere of courtesy (CA) | Affectionate Atmosphere (BLU) |

| Cream spirit (bovine) | Cream Spirit (BLU) | Unpainted (cattle) | Unpainted (BLU) nine0180 |

Previous changes

August 3, 2011 Patch

- Fury has been added to the game.

Learn more