What does it mean when you hear voices

Hearing voices | Mental Health Foundation

While hearing voices can be a symptom of some mental health problems, not everyone who hears voices has a mental illness. Hearing voices is actually quite a common experience: around one in ten of us will experience it at some point in our lives.

Hearing voices is sometimes called an ‘auditory hallucination’. Some people have other hallucinations, such as seeing, smelling, tasting or feeling things that don’t exist outside their mind. Whatever your experience, you’re not alone.

What’s it like to hear voices?

Everyone’s experience of hearing voices is different. The voices can vary in how often you hear them, what they sound like, what they say, and whether they’re familiar or unfamiliar.

Sometimes hearing voices can be upsetting or distressing. They may say hurtful or frightening things. However, some people's voices may be neutral or more positive. You may feel differently about your voices at different times in your life.

Why do people hear voices?

It’s common to think that hearing voices must be a sign of a mental health condition, but many people who are not mentally unwell hear voices.

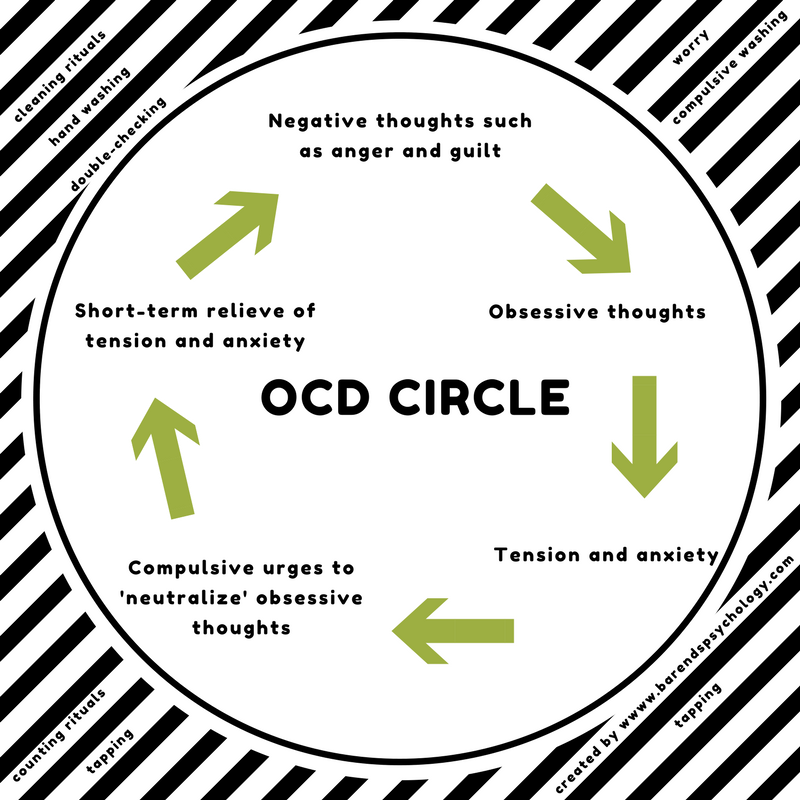

People may hear voices because of:

- traumatic life experiences, which may be linked to post-traumatic stress disorder

- stress or worry

- lack of sleep

- extreme hunger

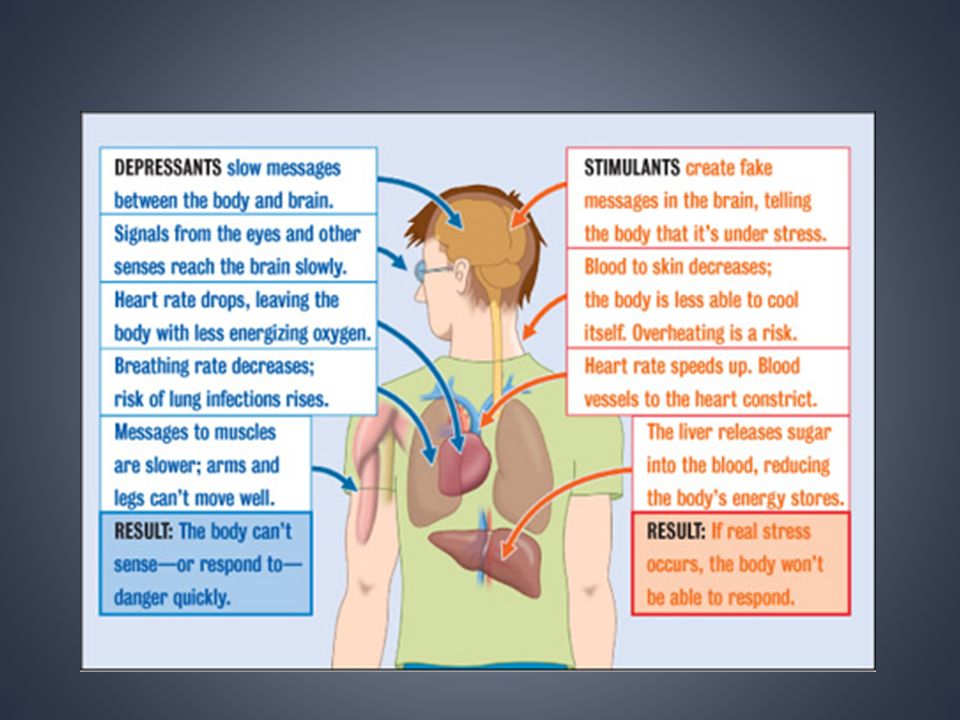

- taking recreational drugs, or as a side-effect of prescribed drugs

- mental health conditions such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or severe depression

Getting support

If you hear voices, talk to your GP. They will usually check for any physical reasons you could be hearing voices before diagnosing you with a mental health condition or referring you to a psychiatrist.

If your voices are the result of a mental health condition, you may be offered:

- talking therapy, such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). CBT can help you learn what triggers your voices and how to manage them.

It can also help you stand up to them if they’re critical or negative

It can also help you stand up to them if they’re critical or negative - medication, most likely an antipsychotic drug. This may stop the voices, make them quieter or make you feel less concerned about them. You may only need medication for a short time while you learn other techniques to manage the voices

You may also be offered family intervention (where support is provided to both you and your family), art or creative therapy, or therapy for experiences of trauma.

Rethink has more information about the treatment you may be offered.

Ways you can look after yourself

Sometimes, voices are a problem because of your relationship with them. Changing your relationship can make you feel differently about them.

Understanding your voices

Understanding how your voices relate to your life may help you to manage their voices.

This could include keeping a diary of your voices. You could note what they say, how they make you feel and how you manage them. This may help you to notice patterns of what makes you feel bad, what makes you feel good, or what triggers your voices.

This may help you to notice patterns of what makes you feel bad, what makes you feel good, or what triggers your voices.

Taking control

Some people find that standing up to the voices, choosing when to pay attention to them and when to ignore them, and focusing on more positive voices can help them feel more in control. Talking therapy can help you with this, as it can be difficult on your own.

Keeping busy

Keeping busy can distract you from the voices, help you express yourself, feel more relaxed, and allow you to meet new people. You could try listening to music or audiobooks, keeping up with hobbies or doing something creative such as writing or painting.

Sharing your experiences

There can be a stigma around hearing voices, making it hard to talk about them, even to friends or family. Peer support groups can provide a non-judgemental space where you can feel heard, accepted and less alone. Some groups are in person, such as the ones listed on the Hearing Voices Network website. Others are online, such as the Intervoice forum, Voice Collective forum and Mind’s Side by Side community.

Others are online, such as the Intervoice forum, Voice Collective forum and Mind’s Side by Side community.

Looking after yourself

Though it can be difficult, looking after and being kind to yourself is important. This can include things like eating a healthy diet, finding ways to stay physically active, managing stress or spending time outdoors. It may help to set goals around these activities and to reward yourself for working towards them.

Further information and resources

Educational Voice Hearing Network aims to improve understanding of what it’s like for people who hear voices. They have a guide for employers who want to support people who hear voices in the workplace.

Hearing Voices Network provides information and support for people who hear voices and have other unusual sensory experiences.

Intervoice is an international network for people who hear voices. They have information on living with voices and offer workshops and events.

Mind has more information about living with voices, including personal stories from people who hear voices.

Understanding Voices has information on different approaches to hearing voices and ways to manage distressing voices.

Voice Collective supports children and young people who hear voices, see visions, or have other unusual sensory experiences or beliefs.

Causes, Symptoms, Types & Treatment

Overview

What are auditory hallucinations?

Auditory hallucinations happen when you hear voices or noises that aren’t there. The sounds you hear may seem real, but they’re not.

A person may perceive auditory hallucinations as coming through their ears, on the surface of their body, in their mind or from anywhere in the space around them. They can occur as frequently as daily or as an isolated episode.

Auditory hallucinations are often associated with schizophrenia and other mental health conditions, but they can happen for several other reasons, such as hearing loss, and aren’t always a sign of a mental health condition.

Researchers estimate that 5% to 28% of people in the United States experience auditory hallucinations. They’re the most common type of hallucination.

They’re the most common type of hallucination.

Some people experience auditory hypnogogic hallucinations that specifically take place as they’re falling asleep. These types of hallucinations are common and usually not a cause for concern.

What are the types of auditory hallucinations?

The two main types of auditory hallucinations are verbal (hearing voices) and hearing sounds or noises.

Auditory verbal hallucinations (hearing voices)

An auditory verbal hallucination is the phenomenon of hearing voices in the absence of any speaker.

The experience of hearing voices can vary greatly from person to person and even for the same person. They can vary in how often you hear them, what they sound like, what they say and whether they’re familiar or unfamiliar.

The voices may come from a single source, such as a television, or multiple sources. It may be a singular voice or multiple voices. They may talk directly to the person, have discussions with them or describe events taking place.

The voices may be positive, negative or neutral. Sometimes, hearing voices can be upsetting or distressing. They may command you to do something that may cause harm to yourself or others.

Auditory verbal hallucinations most commonly affect people with schizophrenia and/or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), but they can happen to people who don’t have any health conditions.

Hearing sounds or noises

Auditory hallucinations can take the form of hearing sounds or noises, such as music, animal calls, nature sounds or background noises. They may seem like they’re coming from anywhere in the space around you or in your mind. The noise volume can vary from very quiet to very loud.

Is it normal to hear auditory hallucinations?

If you experience auditory hallucinations just as you’re falling asleep (hypnogogic hallucinations) or waking up (hypnopompic hallucinations), it’s considered normal and usually not a cause for concern. Up to 70% of people experience these types of hallucinations at least once.

If you experience auditory hallucinations while you’re wide awake, it may be — but isn’t always— a symptom of a mental health or neurological condition. Talk to your healthcare provider about the hallucinations and any other symptoms you have.

Possible Causes

What are the possible causes of auditory hallucinations?

Several situations and conditions — both temporary and chronic — can cause auditory hallucinations.

Scientists don’t yet know the exact mechanisms in your brain that cause auditory hallucinations, but they have a few theories, including:

- Spontaneous activation of the auditory network in your brain, which consists of the left superior temporal gyrus, transverse temporal gyri (Heschl's gyri) and the left temporal lobe.

- An imbalance of dopamine and serotonin, which are neurotransmitters.

Schizophrenia and auditory hallucinations

Approximately 75% of people with schizophrenia experience auditory hallucinations — usually hearing voices.

Schizophrenia refers to both a single condition and a spectrum of conditions that fall under the category of psychotic disorders. These are conditions where a person experiences some form of disconnection from reality. Those disconnections can take several different forms, including experiencing hallucinations.

Schizophrenia is characterized by:

- Psychosis (disconnection from reality).

- Hallucinations.

- Delusions (false beliefs).

- Disorganized speech and behavior.

- Restricted range of emotions.

- Impaired reasoning and problem-solving.

- Occupational and social dysfunction.

Schizophrenia is a chronic condition that may progress through several phases, although the length and patterns of the phases can vary. People with schizophrenia are more likely to experience hallucinations during the active phase.

Other mental health conditions that can cause auditory hallucinations

People with other mental health conditions can experience auditory hallucinations. They affect:

They affect:

- 20% to 50% of people with bipolar disorder.

- 40% of people with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

- 14% of people with an anxiety disorder.

- 10% of people with major depression.

Hearing impairment and hallucinations

Auditory hallucinations occur in 16% of adults with hearing impairment, which can take two forms: simple hallucinations (tinnitus) and complex hallucinations (speech and music).

According to studies, the more severe the hearing impairment, the more likely it is that you’ll experience auditory hallucinations.

Neurological causes of auditory hallucinations

Several neurological conditions can cause auditory hallucinations, including:

- Sleep disorders, such as narcolepsy and insomnia.

- Parkinson’s disease.

- Stroke.

- Migraine.

- Brain tumors or lesions in your temporal lobe, brainstem or thalamus.

Other causes of auditory hallucinations

Several other — usually temporary — conditions and situations can cause auditory hallucinations, including:

- Alcohol and recreational drug use.

- Lack of sleep.

- Extreme hunger.

- Certain prescribed medications (as a side effect).

- Extreme stress or grief.

- Infections, such as UTIs, especially in people who are older.

- Recovering from anesthesia after a surgery or procedure.

Care and Treatment

How are auditory hallucinations treated?

The treatment for auditory hallucinations depends on the cause. Hallucinations caused by temporary conditions, such as extreme hunger or lack of sleep, will stop once the underlying condition has been treated or resolved.

Medications to manage auditory hallucinations

Healthcare providers only prescribe medication to manage auditory hallucinations if they’re part of an underlying chronic condition. Medications include:

- Neuroleptics (antipsychotics): These medications may help decrease the frequency and severity of auditory hallucinations in people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

The antipsychotic medication clozapine (Clozaril®) is the most effective option for treating symptoms of schizophrenia, including hallucinations, but it can cause dangerous side effects that affect your blood.

The antipsychotic medication clozapine (Clozaril®) is the most effective option for treating symptoms of schizophrenia, including hallucinations, but it can cause dangerous side effects that affect your blood. - Psychotropic medications: Psychotropic medications, such as antidepressants and mood stabilizers, can help treat auditory hallucinations in people with severe depression or mania.

Psychotherapy (talk therapy) for auditory hallucinations

For people with mental health conditions who experience auditory hallucinations, psychotherapy (talk therapy) can help in conjunction with medication.

Psychotherapy is a term for a variety of treatment techniques that aim to help you identify and change troubling emotions, thoughts and behaviors. Working with a mental health professional, such as a psychologist or psychiatrist, can provide support, education and guidance to you and your family.

Types of psychotherapy that can help with auditory hallucinations include:

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT): This type of therapy helps you learn how to modify how you experience auditory hallucinations, ultimately offering an improved sense of control over them.

CBT implements reality testing and can be provided in an individual or group setting.

CBT implements reality testing and can be provided in an individual or group setting. - Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT): This type of therapy involves active acceptance and achievement of worthwhile goals despite experiencing auditory hallucinations. ACT may help reduce auditory hallucinations and may increase your feeling of control over them.

- Hallucination-focused integrative treatment (HIT): This is a specific treatment for auditory verbal hallucinations (hearing voices) that involves techniques from cognitive behavioral therapy, psychoeducation, coping training, rehabilitation and medication. It emphasizes active family involvement, crisis intervention (when required) and specialized motivational strategies.

How can I stop auditory hallucinations?

If you’re experiencing auditory hallucinations only as you’re falling asleep (hypnogogic hallucinations), they may decrease in frequency if you do the following:

- Get enough quality sleep.

- Follow a regular sleep schedule.

- Avoid alcohol and certain drugs and medications.

If you experience auditory verbal hallucinations (hearing voices) due to a mental health or neurological condition, it’s important to talk to your healthcare provider about them. Aside from medication and talk therapy, other techniques may help you manage and cope with them, including:

- Distraction techniques, such as listening to music on headphones, exercising, cooking or doing a hobby may help quiet the voices.

- Joining a support group with other people who experience auditory verbal hallucinations.

- Taking control, such as ignoring the voices or standing up to them.

When to Call the Doctor

When should auditory hallucinations be treated by a doctor or healthcare provider?

Auditory hallucinations have several causes — some of which are normal and harmless. But if you’re experiencing auditory hallucinations that are causing you distress, talk to your healthcare provider.

If you or someone you know is experiencing auditory hallucinations and is detached from reality, you or they should get checked by a healthcare provider as soon as possible.

A note from Cleveland Clinic

It’s important for people experiencing auditory hallucinations to talk about them with their family and healthcare team, especially if they’re causing distress. Auditory hallucinations caused by a mental health condition are usually manageable with treatment and can become disturbing or dangerous if they’re not treated. Discuss all possible symptoms with your healthcare provider, no matter how minor or bizarre you may think they are. Hallucinations can make you feel nervous, paranoid and frightened, so it's important to be with and talk with someone you can trust.

How auditory hallucinations change the concept of normal and pathological - Knife

Eleanor Longden first heard a voice when she was a student. The voice calmly and patiently described everything she did: "she leaves the library", "she goes to a lecture", "she opens the door". When she was angry and had to hide her feelings, the voice became irritated, but otherwise did not bother her much.

When she was angry and had to hide her feelings, the voice became irritated, but otherwise did not bother her much.

On the advice of her friend, Eleanor nevertheless decided to go to a psychiatrist. She was admitted to the clinic, diagnosed with schizophrenia and prescribed antipsychotic drugs. But this did not help her get rid of the hallucinations - on the contrary, there were more voices, and they sounded more and more hostile. Gradually, Eleanor began to do what the doctors did not advise her to do: she began to pay attention to the content of the voices and try to decipher their meaning. She began to communicate with them: if the voices ordered her not to leave the house, she thanked them for the reminder that she did not feel safe, and then assured that there was nothing to be afraid of. nine0003

Later, she came to the conclusion that each voice symbolized a lost and rejected part of her own personality - memories of childhood trauma and abuse, feelings of anger, guilt and shame: "Voices came to replace this pain, turned it into words.

"

" When she learned to work with these emotions, the voices began to subside. Although they never completely disappeared, Eleanor stopped taking her medication and was able to return to her normal life.

Hallucinations of a healthy person

In the traditional biomedical model, hallucinations are an insignificant symptom, a sign of genetic abnormalities and an imbalance of neurotransmitters. Voices must be ignored and silenced. Trying to discuss them with the patient means pushing him into delusional reasoning and tearing him even more away from reality. Despite great efforts and years of research, this model has not been able to explain how such hallucinations occur and offer effective treatments.

In psychiatric clinics, hallucinations are usually treated with antipsychotics, substances that block dopamine receptors in the brain. But this method does not help everyone. Up to 30% of people with schizophrenia hear voices even on strong doses of antipsychotics. Psychiatrists recognize that voices in the head can appear for a variety of reasons. They are found not only in schizophrenia, but also in bipolar disorder, severe depression, post-traumatic syndrome, as well as in absolutely healthy people. nine0003

Psychiatrists recognize that voices in the head can appear for a variety of reasons. They are found not only in schizophrenia, but also in bipolar disorder, severe depression, post-traumatic syndrome, as well as in absolutely healthy people. nine0003

If you hear voices, it doesn't necessarily mean you're crazy.

It is estimated that between 5% and 15% of people hear voices coming from nowhere at some point in their lives, usually in a situation of great stress or loss. The vast majority of them do not have a psychiatric diagnosis. In healthy people, hallucinations often consist of one or two words - for example, a recently deceased spouse may suddenly call you by name from the next room. In children, hallucinations generally happen everywhere - it seems to be a normal part of human growing up. nine0003

Some people hear voices almost every day without experiencing other psychiatric problems. People with schizophrenia are more likely to encounter hostile voices: they threaten, call for violence, shower derogatory comments, and encourage suicide.

People without a clinical voice diagnosis, on the other hand, are usually given support and comfort. They advise not to miss the train, suggest a solution to a difficult problem, or warn of a dangerous turn on the road. nine0008

Researchers at Yale University studied a group of mediums—people who claim to have supernatural powers, such as reading minds from a distance or transmitting messages from spirits. Scientists conducted a psychiatric examination and made sure that these people really hear extraneous voices, but do not meet other criteria for schizophrenia. Apart from hallucinations and some strange ideas, they are absolutely healthy.

It turns out that the relationship with voices is very dependent on our own expectations and ideas. Stanford scientists found that schizophrenics in Ghana and India are more likely to perceive auditory hallucinations in a positive way: they hear relatives or gods who give advice, scold or give orders about homework. But among the American participants, no one reported a positive impression of hallucinations - the voices more often came from an unknown source, insulted and humiliated, ordered to commit suicide or harm other people. nine0003

nine0003

If schizophrenia is just a biological disease, why such a difference? Anthropologist Tanya Luhrmann suggests that it's all about our ideas about the boundaries of our "I".

In Western culture, each person has an isolated, separate identity, and any encroachment on this territory is perceived as a hostile invasion. And in more collectivist cultures, the self is defined through relationships with people and other beings.

Voices are perceived as another variant of this relationship and therefore do not pose a great danger. nine0003

“Historical and cultural conditions strongly influence how mental suffering is experienced,” Luhrmann points out. Psychiatric disorders are undoubtedly "real" phenomena that require treatment. But how we treat them can affect the very development of the disease. Not all schizophrenics could become shamans if they were born in the Amazon. But even to Westerners, voices can really convey something important.

Voting Recognition Movement

In 1987, Dutch psychiatrist Marius Romm worked with a patient named Patsy Hage who heard hostile voices. At first, Romm refused to discuss the content of the hallucinations with her - like most psychiatrists, he believed that this would only make them stronger. But Haige insisted that the voices were not just a symptom of an illness, that they meant something. Together they discovered that the most important voice reminded Haige of her mother's voice. They concluded that the hallucinations were due to a strict upbringing and an inability to express their emotions. After that, the girl began to recover. nine0003

At first, Romm refused to discuss the content of the hallucinations with her - like most psychiatrists, he believed that this would only make them stronger. But Haige insisted that the voices were not just a symptom of an illness, that they meant something. Together they discovered that the most important voice reminded Haige of her mother's voice. They concluded that the hallucinations were due to a strict upbringing and an inability to express their emotions. After that, the girl began to recover. nine0003

Shortly afterwards, Romm and Hage hosted a program on Dutch television about auditory hallucinations.

More than 450 people called the studio to talk about their experiences with voices. Thus was born the Hearing Voices movement, an international network of therapeutic groups that advocate an alternative approach to auditory hallucinations.

They believe that voices should not be rejected and suppressed, but listened to, accepted and tried to build friendly relations with them. nine0003

nine0003

This is very different from the traditional medical model, in which a person who talks with his voices is the standard psycho. Despite its near-radical focus, the movement gained support among many psychologists and psychiatrists around the world. Hearing Voices chapters exist in over 35 countries including the UK, France, Canada and the US.

Eleanor Longden, after her recovery, became a psychiatrist herself and a well-known voice activist. She sees her hallucinations not as an occasional symptom of an illness, but as a source of insight into complex emotional issues. nine0003

The main question of psychiatry, in her opinion, is not what is wrong with you, but what happened to you. Voices should be perceived as a forgotten and rejected part of your personality. Learning more about your voices means learning more about yourself.

Modern research shows that psychological trauma and hallucinations are more strongly linked than smoking and lung cancer. Those who have experienced sexual abuse and other traumatic experiences several times in their lives are more than 50 times more likely to develop psychosis. Hallucinations in schizophrenia and post-traumatic disorder can be the same, so psychiatrists often misdiagnose. Instead of psychotherapy, they prescribe antipsychotics, which are almost useless in these cases. nine0003

Those who have experienced sexual abuse and other traumatic experiences several times in their lives are more than 50 times more likely to develop psychosis. Hallucinations in schizophrenia and post-traumatic disorder can be the same, so psychiatrists often misdiagnose. Instead of psychotherapy, they prescribe antipsychotics, which are almost useless in these cases. nine0003

The opposite strategy offered by Hearing Voices - listening to voices and accepting even the most evil of them as part of oneself - really helps to restore mental balance for many. Members of the organization often tell the same story: at first, the voices were hostile and terrified me, but once I decided to interact with them, they became more manageable, sometimes even helpful. For example, they advise you to go to bed on time or eat healthy food. The voice becomes a kind of imaginary friend who is always there. nine0003

But this movement also has many critics. Some of them believe that activists are rejecting scientific knowledge by downplaying the research of scientific psychiatrists.

Others fear that therapy groups are pushing people to stop taking medication. They argue that the movement draws too much attention to the adoption of votes, instead of solving the problem that provoked them.

The main goal of activists is to eliminate the stigma associated with mental illness. They want to create a future in which anyone can walk down the street, speak with their own voices, and yet no one considers them crazy. nine0003

Previously, homosexuality was also considered a disease, but now we know that it is all about social attitudes and stereotypes. Voices do not always lead to suffering and aggression: many people can learn to live with their voices and not harm anyone. “Hearing voices is a natural, albeit unusual, variation on the human experience,” the organization says in its manifesto. Strange, but now many psychologists and psychiatrists are almost ready to agree with this.

Schizophrenia death

The idea that schizophrenia is a distinct disease with a distinct set of symptoms has long been criticized. Biomedicine has not yet been able to explain how this disease occurs, nor to offer adequate methods of treatment. Despite promising claims and new drugs, the number of people getting better is not increasing over time. Many psychiatrists are beginning to suggest that the very concept of schizophrenia is part of the problem.

Biomedicine has not yet been able to explain how this disease occurs, nor to offer adequate methods of treatment. Despite promising claims and new drugs, the number of people getting better is not increasing over time. Many psychiatrists are beginning to suggest that the very concept of schizophrenia is part of the problem.

Auditory hallucinations, visions and other unusual experiences occur in many people and do not necessarily indicate an underlying pathology. Approximately 75% of people who have heard voices one or more times in their lives are mentally healthy. nine0003

Only 20% of people with potential signs of psychosis develop a full psychotic disorder. This has led many researchers to conclude that schizophrenia is the extreme end of the spectrum, on which there are other conditions that need different treatments.

And sometimes they may not need it at all.

Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Maastricht, Jim van Os, suggested that the term "schizophrenia" be abolished and replaced by the concept of psychotic spectrum disorders . Research on schizophrenia can be compared to looking at different parts of an elephant through a magnifying glass: we have solid work on the tail, torso, and ears, but no clear picture of the whole animal. But this elephant probably just doesn't exist. We must stop trying to find a single cause of the disease and study all the variety of its manifestations.

Research on schizophrenia can be compared to looking at different parts of an elephant through a magnifying glass: we have solid work on the tail, torso, and ears, but no clear picture of the whole animal. But this elephant probably just doesn't exist. We must stop trying to find a single cause of the disease and study all the variety of its manifestations.

An important part of the problem is that schizophrenia is often described as an incurable chronic brain disease. Some doctors tell patients that it would be better if they got cancer - then they would have at least some hope of recovery. nine0003

Because of these stereotypes, people who start hearing voices immediately come to the conclusion that they are doomed. The diagnosis works like a self-fulfilling prophecy - increasing anxiety and leading to worsening symptoms.

Psychiatrists hope that the concept of the psychotic spectrum can help develop new treatments. First, it will become easier to determine who is at the greatest risk. Secondly, it will be clear to everyone that completely different therapeutic approaches should be used for different conditions, and not to offer everyone loading doses of antipsychotics. nine0003

Secondly, it will be clear to everyone that completely different therapeutic approaches should be used for different conditions, and not to offer everyone loading doses of antipsychotics. nine0003

For people who hear unpleasant voices, recently a promising method appeared - avatar therapy.

The patient is seated in front of a monitor where they create a virtual avatar with a face and voice that most closely resembles the source of hostile sounds. With the help of this avatar, a person gradually learns to control auditory hallucinations and make them more tolerable. Clinical trials have shown that this method works even more effectively than sessions with a psychotherapist. nine0003

Most psychiatrists still consider voices in the head to be a symptom of an underlying pathology. But it is only possible to truly declare them a sign of illness if the voices really cause suffering and harm to a person. So far, no one is going to refuse this criterion.

We live in a post-schizophrenic age, says Trinity College psychiatrist Simon McCarthy Jones: "And whatever emerges from the ashes of this outdated concept, it must first and foremost help people."

neuroscientist talks about the nature of auditory hallucinations - T&P

Hallucinations are something that occurs in the absence of an external stimulus, but is perceived as real. They can be associated with all the senses, that is, they can be visual, tactile and even olfactory. Probably the most common type of hallucination is when a person "hears voices". They are called auditory verbal hallucinations. T&P continues a special project with New with the translation of an article by neuroscientist Paul Allen, published on the Serious Science website, about auditory hallucinations and the nature of their occurrence. nine0137

Definition of the term

Although auditory hallucinations are commonly associated with mental illnesses such as bipolar disorder, they are not always a sign of illness. In some cases, they can be caused by lack of sleep; Marijuana and stimulant drugs can also cause perceptual disturbances in some people. It has been experimentally proven that hallucinations can occur due to a prolonged absence of sensory stimuli: in the 1960s, experiments were conducted (which would now be impossible for ethical reasons), during which people were kept in dark rooms without sound. In the end, people began to see and hear things that were not there in reality. So hallucinations can occur both in patients and in mentally healthy people. nine0003

In some cases, they can be caused by lack of sleep; Marijuana and stimulant drugs can also cause perceptual disturbances in some people. It has been experimentally proven that hallucinations can occur due to a prolonged absence of sensory stimuli: in the 1960s, experiments were conducted (which would now be impossible for ethical reasons), during which people were kept in dark rooms without sound. In the end, people began to see and hear things that were not there in reality. So hallucinations can occur both in patients and in mentally healthy people. nine0003

Research into the nature of this phenomenon has been going on for quite some time: psychiatrists and psychologists have been trying to understand the causes and phenomenology of auditory hallucinations for about a hundred years (or maybe longer). In the last three decades, it became possible to use encephalograms, which helped researchers of that time to understand what was happening in the brain during moments of auditory hallucinations. And now we can look at its different areas involved in these periods using functional magnetic resonance scanning or positron tomography. These technologies have helped psychologists and psychiatrists develop models of auditory hallucinations in the brain, mostly related to the function of language and speech. nine0003

And now we can look at its different areas involved in these periods using functional magnetic resonance scanning or positron tomography. These technologies have helped psychologists and psychiatrists develop models of auditory hallucinations in the brain, mostly related to the function of language and speech. nine0003

Proposed theories for the mechanisms of auditory hallucinations

Some studies have shown that when patients experience auditory hallucinations, that is, they hear voices, activity in a part of their brain called Broca's area increases. This area is located in the small frontal lobe of the brain and is responsible for speech production: when you speak, it is Broca's area that works. One of the first to investigate this phenomenon were professors Philip McGuire and Suchy Shergill from King's College London. They noticed that their patients' Broca's area was more active during auditory hallucinations compared to when the voices were silent. This suggests that auditory hallucinations are produced by the speech and language centers of our brain. The results of these studies led to the creation of internal speech models of auditory hallucinations. nine0003

The results of these studies led to the creation of internal speech models of auditory hallucinations. nine0003

When we think about something, we generate inner speech - an inner voice that voices our thinking. For example, when we ask the question "What am I going to eat for lunch?" or “What will the weather be like tomorrow?”, we generate inner speech and are believed to activate Broca’s area. But how does this inner speech begin to be perceived by the brain as external, not coming from itself? According to internal speech models of auditory verbal hallucinations, such voices are thoughts generated inside the consciousness or internal speech, somehow incorrectly defined as external, alien. More complex models of the process of how we track our own inner speech follow from this. nine0003

© Kate MacDowell

English neuroscientist and neuropsychologist Chris Frith and others have suggested that when we engage in thinking and internal speech, Broca's area sends a signal to an area of our auditory cortex called Wernicke's area. This signal contains information that the speech we perceive is generated by us. This is because the transmitted signal is supposed to dampen the neuronal activity of the sensory cortex, so it is not activated as much as it is from external stimuli, such as someone talking to you. This model is known as the self-monitoring model, and it suggests that people with auditory hallucinations are deficient in this process, causing them to be unable to distinguish between internal and external speech. Although the evidence for this theory is rather weak at the moment, it is certainly one of the most influential models of auditory hallucinations that have emerged over the past 20 to 30 years. nine0003

This signal contains information that the speech we perceive is generated by us. This is because the transmitted signal is supposed to dampen the neuronal activity of the sensory cortex, so it is not activated as much as it is from external stimuli, such as someone talking to you. This model is known as the self-monitoring model, and it suggests that people with auditory hallucinations are deficient in this process, causing them to be unable to distinguish between internal and external speech. Although the evidence for this theory is rather weak at the moment, it is certainly one of the most influential models of auditory hallucinations that have emerged over the past 20 to 30 years. nine0003

Consequences of hallucinations

About 70% of schizophrenic patients hear voices to some extent. They are treatable, but not always. Usually (though not in all cases) votes have a negative impact on the quality of life and health. For example, patients who hear voices and do not respond to treatment have an increased risk of suicide (sometimes voices call for self-harm). One can imagine how hard it is for people even in everyday situations, when they constantly hear humiliating and insulting words addressed to them. nine0003

One can imagine how hard it is for people even in everyday situations, when they constantly hear humiliating and insulting words addressed to them. nine0003

But auditory hallucinations do not only occur in people with mental disorders. Moreover, these voices are not always evil. Thus, Marius Romm and Sandra Escher lead a very active "Society of Hearing Voices" - a movement that speaks about their positive aspects and fights against their stigmatization. Many people who hear voices live active and happy lives, so we cannot assume that voices are inherently bad. Yes, they are often associated with aggressive, paranoid and anxious behavior of patients, but it may be due to emotional distress, and not the presence of voices. Nor is it surprising that the anxiety and paranoia that are often at the core of mental illness show up in what these voices say. But, as already mentioned, many people without a psychiatric diagnosis state that they hear voices, and for them this can be a positive experience, since voices can calm or even suggest the direction in which to move in life. Professor Iris Sommer from the Netherlands has carefully studied this phenomenon: the healthy people she studied, hearing voices, described them as something positive, useful and giving self-confidence. nine0003

Professor Iris Sommer from the Netherlands has carefully studied this phenomenon: the healthy people she studied, hearing voices, described them as something positive, useful and giving self-confidence. nine0003

Treating hallucinations

People diagnosed with schizophrenia are usually treated with antipsychotic medications that block postsynaptic dopamine receptors in the striatum, the brain's striatum. Antipsychotics are effective in many cases: as a result of treatment, psychotic symptoms subside, especially auditory hallucinations and mania. Some patients, however, do not respond well to antipsychotics. Approximately 25-30% of patients who hear voices are almost unaffected by drugs. Antipsychotics also have serious side effects, so these medications are not suitable for all patients. nine0003

For other methods, there are many options for non-pharmacological treatment. Their degree of effectiveness also varies. For example, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). Its use for the treatment of psychosis is somewhat controversial, as many researchers believe that it has little effect on the symptoms and overall outcome of the disease. But there are types of CBT designed specifically for patients who hear voices. This therapy is usually aimed at changing the patient's attitude towards the voice so that the latter is perceived as less negative and unpleasant. The effectiveness of this treatment remains in question. nine0003

Its use for the treatment of psychosis is somewhat controversial, as many researchers believe that it has little effect on the symptoms and overall outcome of the disease. But there are types of CBT designed specifically for patients who hear voices. This therapy is usually aimed at changing the patient's attitude towards the voice so that the latter is perceived as less negative and unpleasant. The effectiveness of this treatment remains in question. nine0003

I am currently leading a study at King's College London to see if we can teach patients to self-regulate neural activity in the auditory cortex. This is achieved with the help of neural feedback, which is sent in real time using MRI. An MRI scanner is used to measure the signal coming from the auditory cortex. This signal is then sent back to the patient via a visual interface, which the patient must learn to control (that is, move the lever up and down). It is expected that we will be able to teach voice-hearing patients to control the activity of their auditory cortex, which in turn may allow them to better control their voices. Researchers are not yet sure whether this method will be clinically effective, but some preliminary data will be available in the next few months. nine0003

It is expected that we will be able to teach voice-hearing patients to control the activity of their auditory cortex, which in turn may allow them to better control their voices. Researchers are not yet sure whether this method will be clinically effective, but some preliminary data will be available in the next few months. nine0003

Population prevalence

About 24 million people worldwide are living with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and about 60% or 70% of them have heard voices. There is evidence that from 5% to 10% of the population without a psychiatric diagnosis at some point in their lives also heard them. Some of us sometimes thought that someone was calling us by name, and then it turned out that there was no one around. So there is evidence that auditory hallucinations are more common than we think, although accurate epidemiological statistics are hard to come by. nine0003

The most famous person who heard voices was probably Joan of Arc. From modern history, one can recall Syd Barrett, the founder of the Pink Floyd group, who suffered from schizophrenia and auditory hallucinations. But, again, someone can draw inspiration for art from voices, and some even experience musical hallucinations - something like vivid auditory images - but scientists still doubt whether they can be equated with hallucinations.

But, again, someone can draw inspiration for art from voices, and some even experience musical hallucinations - something like vivid auditory images - but scientists still doubt whether they can be equated with hallucinations.

Unanswered questions

Science currently does not have a clear answer to the question of what happens in the brain when a person hears voices. Another problem is that researchers do not yet know why people perceive them as aliens coming from an external source. It is important to try to understand the phenomenological aspect of what exactly people experience when they hear a voice. For example, when tired or on stimulants, they may experience hallucinations, but not necessarily perceive them as coming from outside. The question is why do people lose the sense of their own activity when they hear voices. Even if we believe that the cause of auditory hallucinations is an excessive activity of the auditory cortex, why do people still think that God, a secret agent or an alien is talking to them? It is also important to study the belief systems that people build around their voices.