What causes involuntary mouth movements

What Is Tardive Dyskinesia? Symptoms, Causes, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention

By Paula DerrowMedically Reviewed by Jason Paul Chua, MD, PhD

Reviewed:

Medically Reviewed

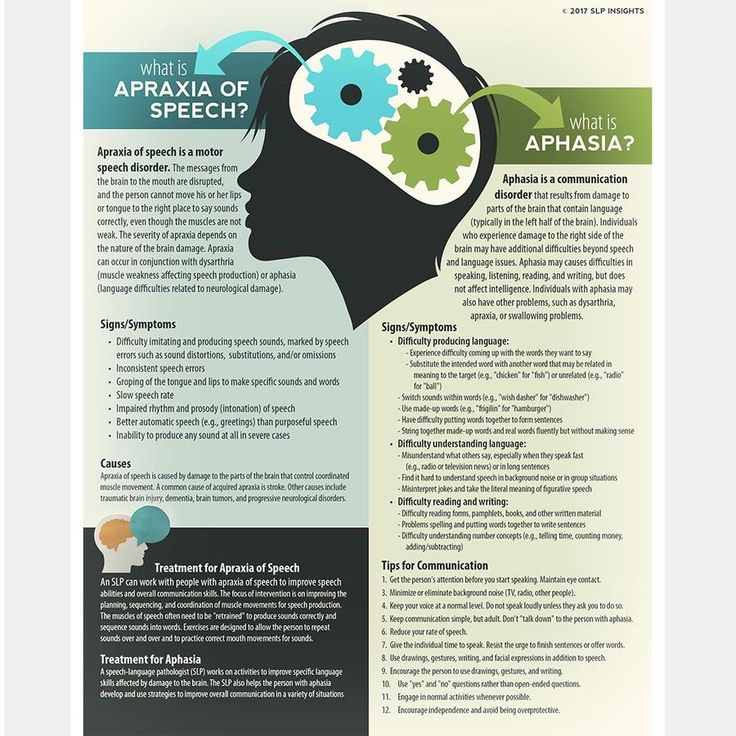

Sometimes medications used to treat serious conditions can bring on serious conditions of their own. That’s the case with tardive dyskinesia (TD), a disorder marked by random and involuntary muscle movements that usually occur in the face, tongue, lips, or jaw.

It’s typically caused by long-term use of antipsychotic medications that block dopamine receptors, but it can be caused by some other drugs as well. Antipsychotic medications are used to treat a number of mental illnesses and mood disorders, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression.

Signs and Symptoms of Tardive Dyskinesia

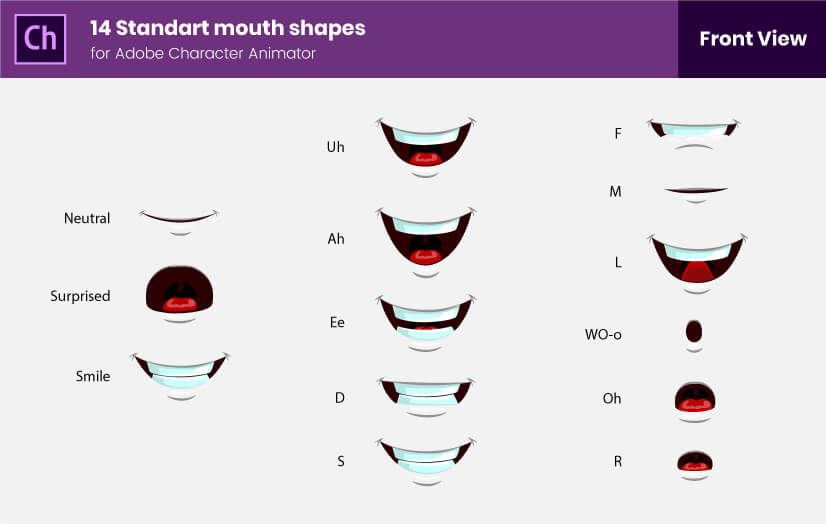

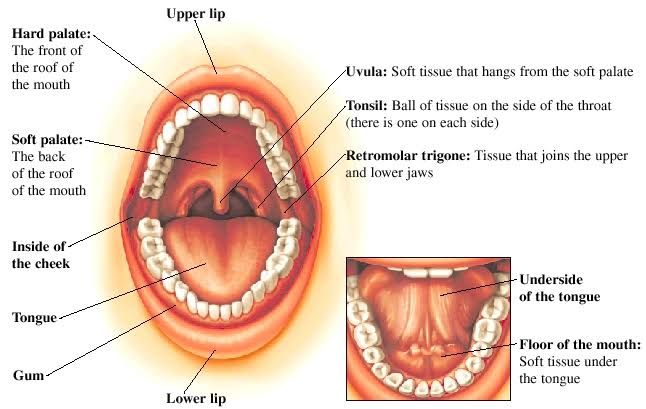

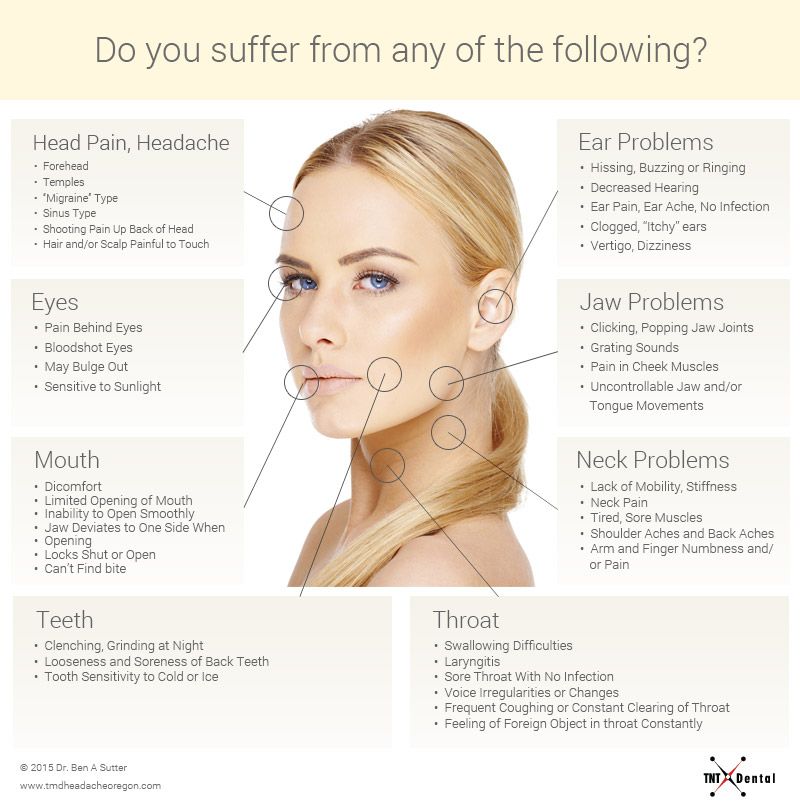

Tardive dyskinesia mainly causes these involuntary movements of the face, tongue, lips, or jaw:

- Lip smacking, puckering, or pursing

- Tongue thrusting or protrusion

- Grimacing

- Repetitive chewing motions

- Rapid eye blinking

It can also cause rocking, jerking, flexing, or thrusting of the trunk or hips and repetitive writhing, twisting, or dancing movements of the fingers or toes, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (PDF).

Antipsychotic drugs can cause tremor, too. This type of involuntary movement disorder is a rhythmic shaking of one or more body parts, whereas movements caused by tardive dyskinesia are irregular and unrhythmic.

RELATED: What’s the Difference Between Tremors and Dyskinesia Associated With Parkinson’s Disease?

Causes and Risk Factors for Tardive Dyskinesia

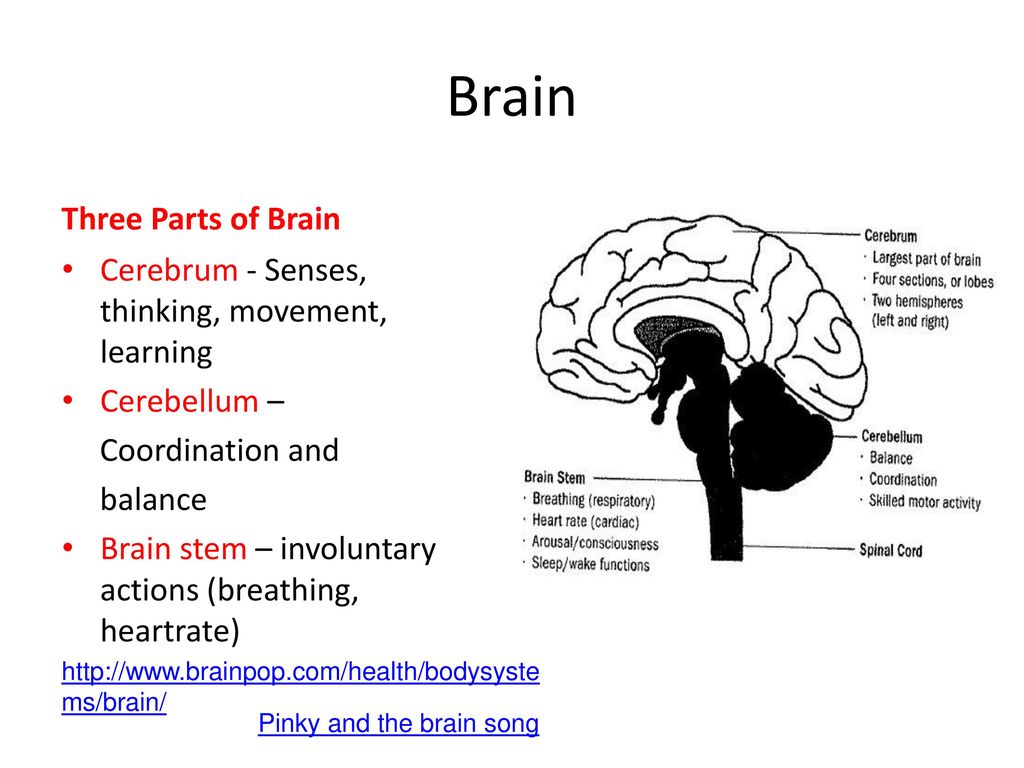

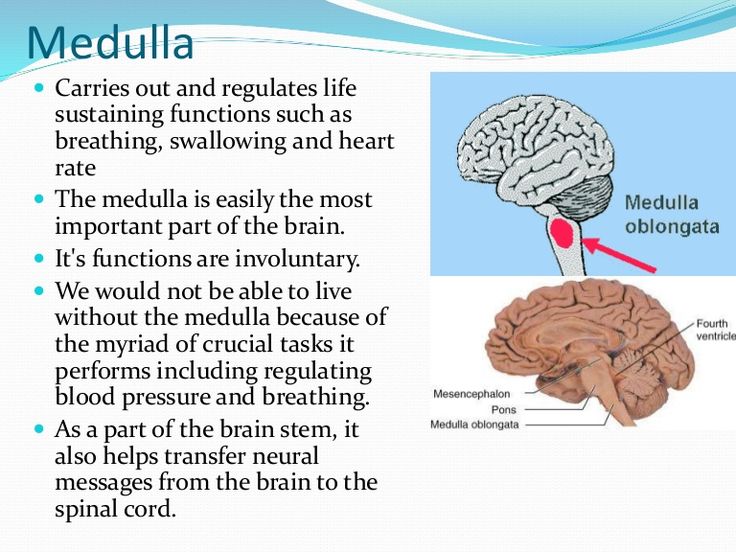

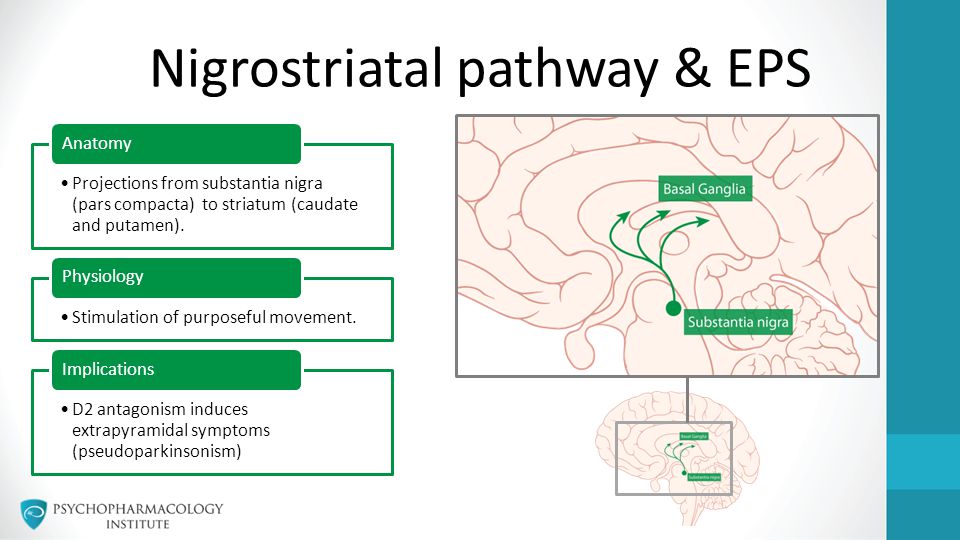

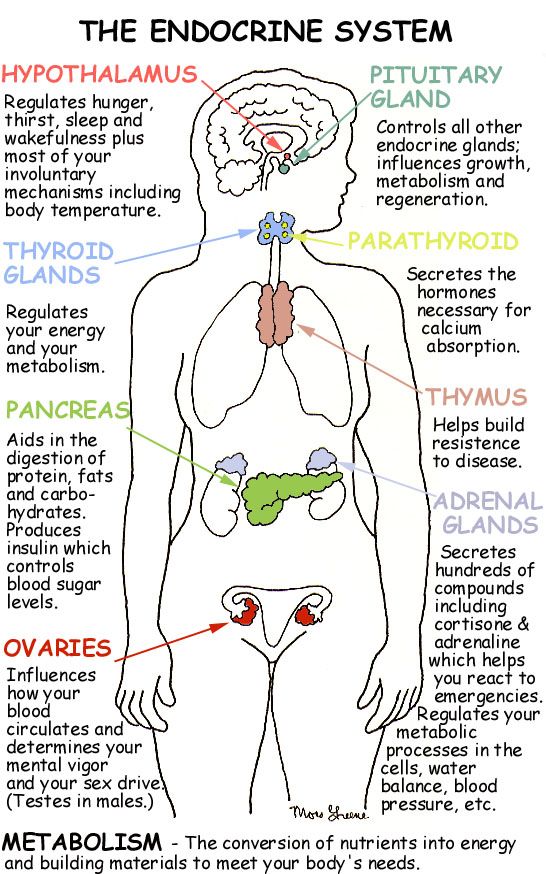

Tardive dyskinesia is mainly caused by an older class of drugs used to treat psychiatric disorders. These antipsychotic medications, also called neuroleptic drugs, work by blocking dopamine receptors in the brain. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that helps control the brain’s reward and pleasure centers. It also plays a major role in motor functioning.

It's not clear why or how tardive dyskinesia symptoms begin, but they're thought to be related to the chronic blocking of dopamine receptors.

The older antipsychotic drugs that cause tardive dyskinesia include:

- Chlorpromazine (Thorazine, Promapar)

- Fluphenazine (Prolixin, Permitil)

- Haloperidol (Haldol)

- Perphenazine (Trilafon)

- Prochlorperazine (Compazine, Compro, or Procomp)

- Thioridazine (Mellaril)

- Trifluoperazine (Stelazine)

So-called second-generation, or atypical, antipsychotics can also cause tardive dyskinesia, according the American Academy of Neurology, although they are less likely to. These drugs include:

These drugs include:

- Aripiprazole

- Clozapine

- Olanzapine

- Quetiapine

- Risperidone

- Sertindole

- Ziprasidone

The following antidepressants may also cause TD, according to MedlinePlus:

- Amitriptyline (Elavil)

- Fluoxetine (Prozac)

- Phenelzine (Nardil)

- Sertraline (Zoloft)

- Trazodone (Desyrel, Oleptro)

Other drugs that can cause TD include:

- Metoclopramide (Reglan, Metozolv ODT), which is used to treat gastroparesis, or slowed stomach emptying

- Phenytoin (Dilantin, Phenytek), which treats seizures

It usually takes many months or years to develop symptoms of tardive dyskinesia, but the side effect can sometimes arise in just six weeks.

It’s possible, although rare, for tardive dyskinesia symptoms to start after a person has stopped taking a medication that can cause it, per the Cleveland Clinic.

According to a report published in June 2018 in the Journal of Neurological Sciences, some of the risk factors for developing tardive dyskinesia include older age, being female, and being white or of African descent. The longer a person has been ill, the more likely they are to develop the symptoms. People with diabetes, who smoke cigarettes, or who abuse alcohol or other substances may be at higher risk, too.

The longer a person has been ill, the more likely they are to develop the symptoms. People with diabetes, who smoke cigarettes, or who abuse alcohol or other substances may be at higher risk, too.

Dyskinesia can also develop in people with schizophrenia who haven’t used antipsychotics, a type known as spontaneous dyskinesia. It is estimated to occur in 25 percent of patients between 30 and 50 years old and in up to 40 percent of people 60 or older, per research. However, since most people with schizophrenia are treated with antipsychotics these days, spontaneous dyskinesia is rarely seen.

How Is Tardive Dyskinesia Diagnosed?

A doctor may make a diagnosis of tardive dyskinesia if a person is taking a medication that can cause it, has signs and symptoms of the problem, or has undergone testing to rule out other neurological or movement disorders that can cause similar symptoms. Other conditions that can cause involuntary or uncoordinated movements include Huntington’s disease, cerebral palsy, Tourette syndrome, and dystonia per the National Organization for Rare Disorders.

Doctors may also use a tool called the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) to detect tardive dyskinesia in people who are taking neuroleptic drugs and to track the severity of their symptoms over time. During an AIMS test, your doctor will gauge the involuntary movement throughout your body on a five-point scale, assessing the severity of movements. The AIMS may be administered before a neuroleptic drug is prescribed so the doctor has a baseline against which to compare future results, according to an article published in April 2022 in StatPearls.

Prognosis of Tardive DyskinesiaThe long-term prognosis for people with tardive dyskinesia varies. When diagnosed early, stopping the medication that is triggering symptoms can resolve the problem, though in some cases, the symptoms may persist indefinitely or worsen over time, according to an article published in 2021 in the journal Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment.

Duration of Tardive Dyskinesia

Stopping the medication that is causing the problem can ease the symptoms, though in some cases the condition is irreversible.

Treatment and Medication Options for Tardive Dyskinesia

There is no standard treatment for tardive dyskinesia. Most likely, your doctor will adjust the medication thought to be causing the symptoms. In many cases, neuroleptic medications will be lowered to the lowest possible dose or discontinued if possible. But there’s limited evidence that lowering the dose, administering the drug intermittently, or stopping the drug altogether will reduce tardive dyskinesia symptoms.

Abruptly stopping a neuroleptic medication is not recommended because doing so can worsen tardive dyskinesia or even cause it in a person who is not already affected by it.

Medication OptionsTwo drugs, deutetrabenazine (Austedo) and valbenazine (Ingrezza), are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia. Both belong to a class of drugs known as selective VMAT2 (vesicular monoamine transporter-2) inhibitors. They are also referred to as dopamine-depleting drugs because of the effect they have in the brain.

Studies of valbenazine show it to be well tolerated, with fatigue or sedation as the main side effect.

More common side effects of deutetrabenazine are akathisia (restlessness), depression, and diarrhea. Deutetrabenazine has a black box warning for depression and suicidality, but data from studies of its effectiveness in treating tardive dyskinesia did not show an increased risk of suicide.

While both drugs have been found to suppress symptoms of tardive dyskinesia, they do not cure TD, and symptoms can recur if the drugs are stopped.

Some other drugs may improve tardive dyskinesia symptoms, but the evidence for them is considered insufficient to recommend them broadly as treatment for tardive dyskinesia.

Alternative and Complementary TherapiesVarious alternative therapies have been studied for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia, but their effectiveness is unclear.

For example, there’s some evidence that branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) — leucine, valine, and isoleucine — which are typically marketed as supplements for building muscle, can decrease TD symptoms. So far, researchers have deemed BCAAs promising and worth studying further.

So far, researchers have deemed BCAAs promising and worth studying further.

Ginkgo biloba extract may also be effective in improving TD symptoms and “should be considered as treatment,” according to an article published in Neurology.

But these findings are still preliminary, and larger and higher-quality studies are needed before these or any other alternative therapies can be recommended for routine use.

Note that any supplement can cause side effects of its own, and many have potential interactions with prescription and over-the-counter drugs. So while preparations of BCAAs and ginkgo biloba are readily available for purchase at retail drugstores and online, it’s a good idea to discuss their use with your doctor before self-treating with these or any other dietary supplements.

Prevention of Tardive DyskinesiaWhen it comes to TD, the best strategy is prevention. That means judicious prescribing of antipsychotic drugs by healthcare providers, regularly monitoring patients for symptoms, and acting quickly to intervene and change treatment when symptoms occur.

Changing medications may also help. While all antipsychotics carry the risk of TD, the second generation of antipsychotics carry less of a risk, according to a meta-analysis published in October 2018 in World Psychiatry.

More About Dopamine

What Is Dopamine?

Some street drugs can mimic the effects of dopamine, an important neurotransmitter.

Complications of Tardive Dyskinesia

Tardive dyskinesia can interfere with eating, speaking, breathing, walking, and other activities of daily living.

The involuntary movements caused by tardive dyskinesia can also cause a person to feel embarrassed or self-conscious and to avoid social interaction. This self-isolation may compound the social isolation already experienced because of the mental or physical disorder necessitating taking the drug in the first place, per an article published in 2019 in Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment.

The low quality of life associated with tardive dyskinesia may lead some people to stop their drug therapy on their own, potentially leading to a relapse in their disease symptoms and, for some, the need for hospitalization.

Research and Statistics: Who Has Tardive Dyskinesia?

According to a meta-analysis published in October 2018 in World Psychiatry, TD tends to occur in about 20 percent of people being treated with first-generation antipsychotics.

Research suggests that women and older patients are at a higher risk of developing the condition. In postmenopausal women in particular, incidence rates are as high as 30 percent.

In people being treated with second-generation antipsychotics, the rate of TD tends to be one-third of the rate of occurrence with first-generation medications, according to the World Psychiatry meta-analysis.

Black Americans and Tardive Dyskinesia

Research summarized in the summer 2017 issue of the Ochsner Journal suggests that being of African descent appears to elevate one’s risk of developing TD. An evaluation of 1,149 patients with TD found that in inpatient settings, African American patients were more likely to develop TD than Americans of European descent.

However, these results may not have taken into consideration the potential confounding factors, such as socioeconomic status and the ways in which doctors might treat African American patients differently with antipsychotics.

Related Conditions and Causes of Tardive Dyskinesia

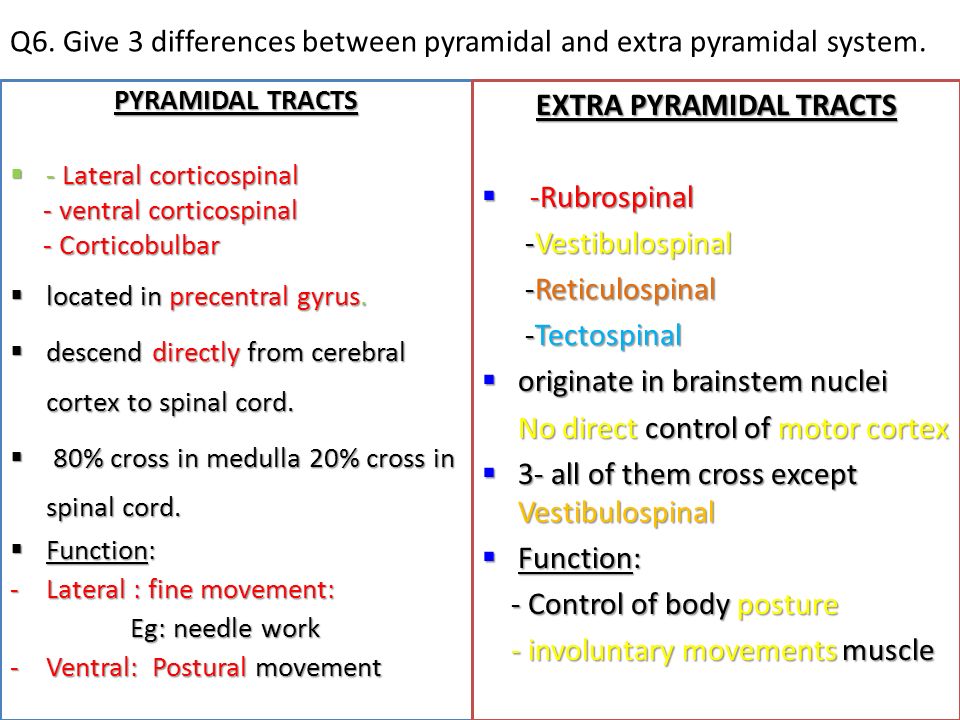

Tardive dyskinesia is one of several extrapyramidal side effects, which are commonly called drug-induced movement disorders. Others include:

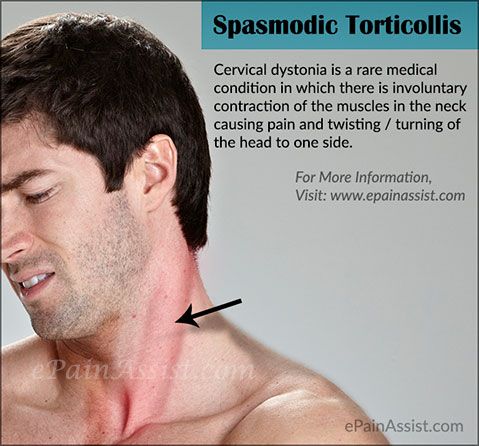

- Dystonia causes involuntary muscle movement leading to abnormal postures — for example, twisting the neck so the head is rotated and held at an odd angle — and repetitive motions. It occurs within two to five days of starting a drug in most cases.

- Akathisia is characterized by a feeling of internal restlessness and a compelling urge to move, leading to repetitive movements such as leg crossing, swinging, or shifting from one foot to another. It usually starts within four weeks of starting or increasing the dosage of the medication causing it.

Tardive akathisia is akathisia that starts after the causative drug has been started or discontinued.

Tardive akathisia is akathisia that starts after the causative drug has been started or discontinued. - Drug-induced parkinsonism causes tremor, rigid muscles, and slowed movement.

While extrapyramidal symptoms are more likely to occur with first-generation antipsychotics, they can occur with second-generation antipsychotics as well.

Extrapyramidal symptoms can go away on their own or with treatment. However, they can be painful while they last, and without treatment, they can lead to serious and even life-threatening complications.

Resources We Love

National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI)

NAMI is a grassroots mental health organization that offers education, support, and advocacy. The toll-free NAMI help line can be reached Monday through Friday from 10 a.m. to 10 p.m. Eastern time at 800-950-NAMI (6264) or at [email protected].

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)

NINDS provides a wealth of information on movement disorders, including tardive dyskinesia. It also maintains a database of clinical trials.

It also maintains a database of clinical trials.

MedlinePlus

A service of the National Library of Medicine, MedlinePlus presents health and medical information in a reader-friendly manner.

Mental Health America

Mental Health America is a community-based nonprofit that provides education and peer support and that advocates for mental health awareness and care for all Americans.

Additional reporting by Carlene Bauer and Ingrid Strauch.

Editorial Sources and Fact-Checking

- Tardive Dyskinesia Checklist [PDF]. National Alliance on Mental Illness.

- Treatment of Tardive Syndromes. American Academy of Neurology. July 2013.

- Tardive Dyskinesia. MedlinePlus. June 23, 2020.

- Tardive Dyskinesia. Cleveland Clinic. December 20, 2021.

- Solmi M, Pigato G, Kane J, Correll C. Clinical Risk Factors for the Development of Tardive Dyskinesia. Journal of Neurological Sciences.

June 2018.

June 2018. - Fenton WS. Prevalence of Spontaneous Dyskinesia in Schizophrenia. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2000.

- Tardive Dyskinesia. National Organization for Rare Diseases. 2018.

- Vasan S, Padhy R. Tardive Dyskinesia. StatPearls. April 30, 2022.

- Citrome L, Isaacson SH, Larson D, Kremens D. Tardive Dyskinesia in Older Persons Taking Antipsychotics. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2021.

- Bergman H, Rathbone J, Agarwal V, et al. Antipsychotic Reduction and/or Cessation and Antipsychotics as Specific Treatments for Tardive Dyskinesia. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. February 2018.

- Caroff SN. Recent Advances in the Pharmacology of Tardive Dyskinesia. Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience. November 30, 2020.

- Cornett E, Novitch M, Kaye AD, et al. Medication-Induced Tardive Dyskinesia: A Review and Update. The Ochsner Journal. Summer 2017.

- Bhidayasiri R, Fahn S, Weiner WJ, et al.

Evidence-Based Guideline: Treatment of Tardive Syndromes. Neurology. July 30, 2013.

Evidence-Based Guideline: Treatment of Tardive Syndromes. Neurology. July 30, 2013. - Carbon M, Kane J, Leucht S, Correll C. Tardive Dyskinesia Risk With First‐ and Second‐Generation Antipsychotics in Comparative Randomized Controlled Trials: A Meta‐Analysis. World Psychiatry. October 2018.

- Caroff SN. Overcoming Barriers to Effective Management of Tardive Dyskinesia. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2019.

- Patel RS, Mansuri Z, Chopra A. Analysis of Risk Factors and Outcomes in Psychiatric Inpatients With Tardive Dyskinesia: A Nationwide Case-Control Study. Heliyon. May 2019.

- D'Souza RS, Hooten WM. Extrapyramidal Symptoms. StatPearls. May 2, 2022.

Show Less

By subscribing you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

5 Surprising Signs You’re About to Get Migraine

The classic warning sign of migraine is aura — but many people experience other migraine signs, including food cravings, frequent urges to urinate, sleepiness. ..

..

By Lisa Haney

Quiz: Am I at Risk for Tardive Dyskinesia?

If you take certain medications for your mental health, you could be at risk for developing a condition called tardive dyskinesia, which causes involuntary...

By Erica Patino

Myths and Facts About Tardive Dyskinesia

Tardive dyskinesia is a type of movement disorder that’s most often caused by long-term use of antipsychotic medication. Learn the facts about it here...

By Becky Upham

6 Things People With Tardive Dyskinesia Want You to Know

The symptoms of tardive dyskinesia (TD) can include involuntary movements like lip smacking, tongue movement, and more. Read real accounts of what it’...

By Becky Upham

Quiz: Am I at Risk for Tardive Dyskinesia?

What Is Psychosis? Symptoms, Causes, Diagnosis, and Treatment

What Is Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)? Symptoms, Causes, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Does Parkinson's disease cause involuntary mouth movements?

People with Parkinson’s disease may experience involuntary movements such as tremors, which can occur in the muscles of the face. Medication can also cause involuntary movements that affect the mouth.

Medication can also cause involuntary movements that affect the mouth.

Parkinson’s disease affects the control of body movements and can cause involuntary movements. In certain cases, these affect the face and mouth.

In Parkinson’s disease, nerve cells in the brain experience damage or die. These cells can no longer produce the chemical dopamine, which is important for controlling movement.

This article will explore the involuntary mouth movements that can occur in people with Parkinson’s disease, why they occur, treatment, and more.

People with Parkinson’s disease experience involuntary movement changes throughout the body. These may include:

- tremors

- muscle stiffness

- slowed movements

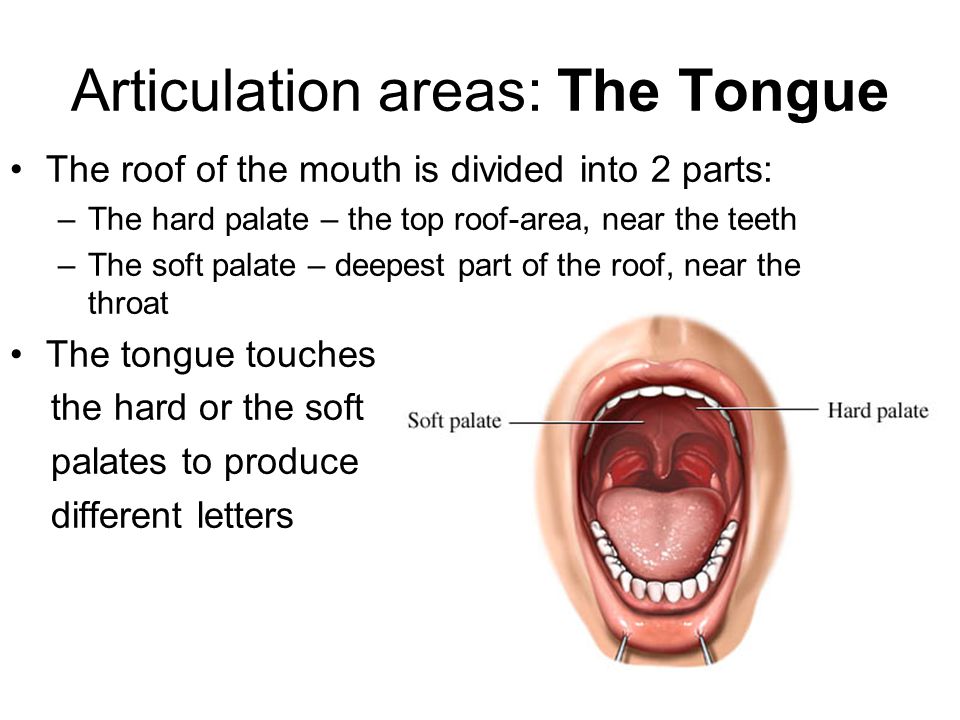

Taking Parkinson’s medications over a long period may also lead to involuntary movements. These can affect speech, chewing, and facial expressions and may involve:

- twisting of the neck

- grimacing

- tongue and lip movements

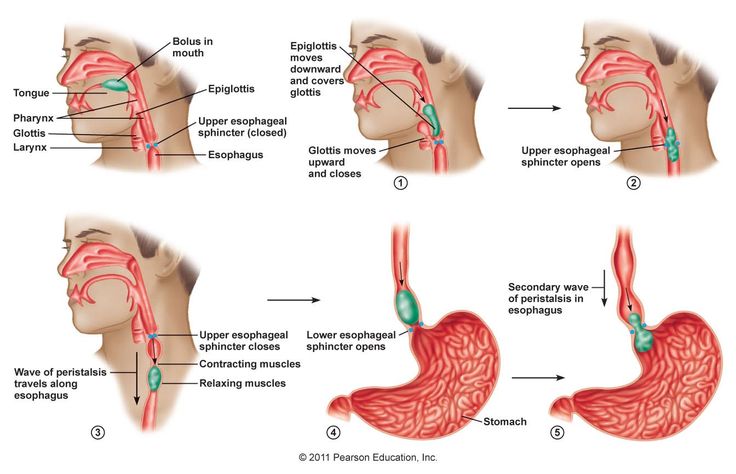

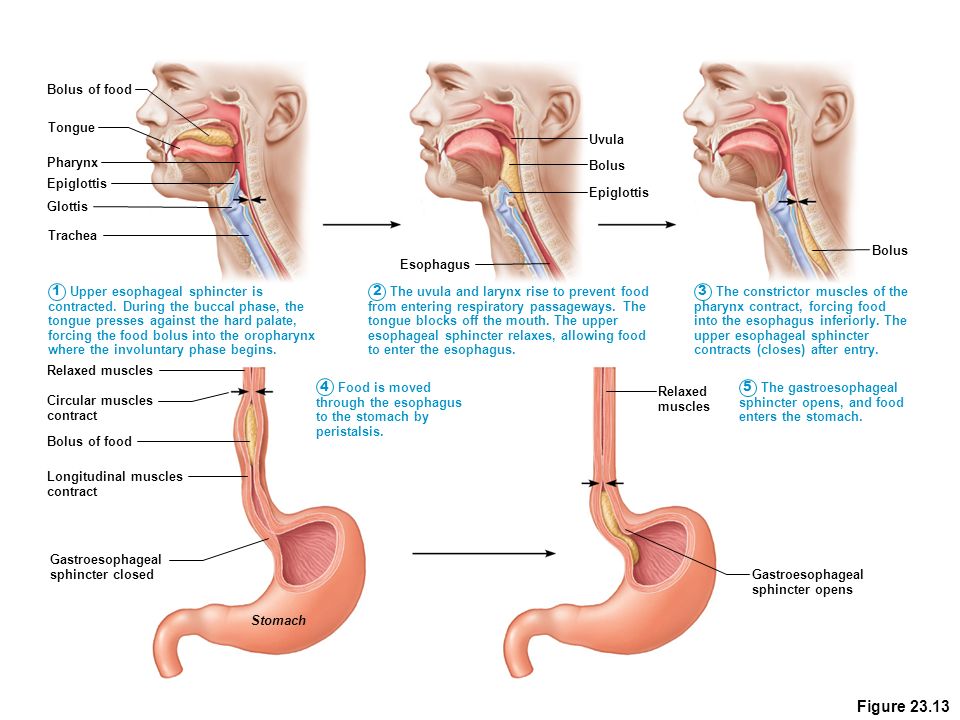

- difficulty with swallowing

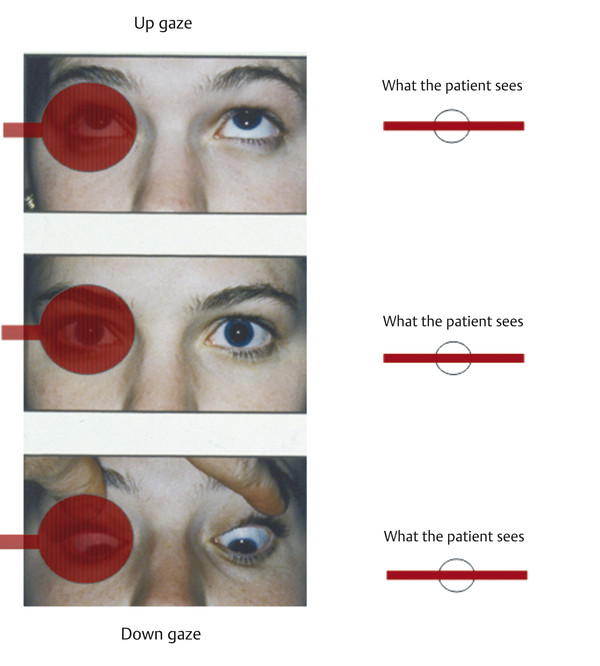

Facial tremors

Tremors affecting the face are relatively uncommon in Parkinson’s disease. One study found that only 5% of participants with the condition exhibited facial tremors. Another study identified facial tremors in 18.1% of participants with Parkinson’s disease.

One study found that only 5% of participants with the condition exhibited facial tremors. Another study identified facial tremors in 18.1% of participants with Parkinson’s disease.

Researchers believe that the risk of lip and jaw tremors increases among people who have had Parkinson’s disease for longer. It may also be more common among females and older individuals.

Parkinson’s disease can also cause stiffness in facial muscles. The lips of individuals who experience this may lack any sign of movement, known as facial masking.

Learn more about Parkinson’s tremors and how they differ from other tremors.

Jaw movements

Similarly, involuntary movements and stiffness can affect the jaw in people with Parkinson’s disease.

Individuals experiencing involuntary jaw movements may develop altered chewing patterns. Those with jaw rigidity may experience a reduced range of motion while chewing or speaking.

Involuntary tongue movements

Some people with Parkinson’s disease experience tongue movements they cannot control.

These can affect speaking and swallowing and make it difficult to chew food, as the tongue may expel it from the mouth.

Involuntary movements in and around the mouth can cause a range of symptoms, including:

- Teeth knocking: Some people may experience knocking of their teeth due to facial tremors.

- Involuntary opening and closing of the jaw: This can lead to difficulty with speech and eating.

- Side-to-side tongue movements: These may also cause difficulty with eating or speaking.

- Incomplete opening of the mouth: In certain cases, jaw rigidity can make it difficult to open the mouth fully.

- Involuntary lip movements: These can affect speaking patterns.

- Reduced facial expressions: Lip rigidity can also weaken lip muscles and reduce the range of facial expressions a person can make.

Although involuntary mouth movements are not as common as some other signs of Parkinson’s disease, they may impact the quality of life for people with this condition who experience them.

Learn more about other symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.

Although there is currently no cure for Parkinson’s disease, many treatments are available to help manage its symptoms.

Levodopa

The most effective medication for Parkinson’s disease is levodopa, which goes under the brand name Sinemet (carbidopa/levodopa). This drug may help reduce movement symptoms associated with this condition.

However, levodopa can also cause involuntary movements affecting the jaw, lips, or tongue. Some individuals taking levodopa for Parkinson’s disease may develop involuntary mouth movements due to their treatment.

Exercise and physical therapy

Certain forms of exercise that may help with movement symptoms include:

- dance

- tai chi

- yoga

- boxing

Exercise and physical therapy may help a person manage Parkinson’s symptoms without the side effects associated with other treatments.

Other treatment options

Some individuals with Parkinson’s disease may benefit from deep brain stimulation (DBS), in which surgeons place a pulse-generating device under the skin of the chest or stomach, connected to one or two fine wires that surgeons insert into specific brain areas.

The device delivers high frequency stimulation that may change electrical signals in the brain that cause Parkinson’s symptoms.

Researchers are also looking into vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) as a treatment. Similar to DBS, this involves using a device to stimulate certain brain areas in an effort to reduce symptoms. A surgeon can implant this device within the brain. However, noninvasive forms of VNS are also available.

Vibrotactile stimulation devices are another potential treatment for involuntary movements. They deliver vibrations to different muscles in the body. These devices may help reduce tremors and other involuntary movements.

Because no single treatment works best for everyone with Parkinson’s disease, it is best for individuals experiencing involuntary mouth movements to speak with a healthcare professional. They can help design an appropriate treatment plan specific to each person.

Learn more about treatment options.

Several medications may help address involuntary movements, such as:

- levodopa

- pramipexole

- ropinirole

- selegiline

- amantadine

Tips when starting new medications

Before beginning a new medication, it is best to speak with a medical professional about proper dosage and timing. Parkinson’s disease medications can also cause side effects that may include:

Parkinson’s disease medications can also cause side effects that may include:

- nausea

- dizziness

- involuntary movements

- confusion

- sleepiness

When beginning a new medication, keeping a diary and noting any physical changes or side effects can be helpful. If any negative side effects occur, it is best to consult a healthcare professional as soon as possible.

Doctors advise that anyone experiencing new or worsening Parkinson’s disease symptoms contact a healthcare professional.

Muscle stiffness, tremors, changes in walking patterns, and speech changes are all common symptoms. New or worsening mouth movements may also be important for healthcare professionals to know about.

It is also best for individuals who develop negative side effects from Parkinson’s medications to seek medical advice. Although many side effects are minor, levodopa can cause severe side effects such as hallucinations or psychosis.

Parkinson’s disease can cause involuntary muscle movements that may affect the face and mouth. Movements affecting the mouth can occur in the jaw, tongue, or lips.

Movements affecting the mouth can occur in the jaw, tongue, or lips.

Although these movements are less common than other Parkinson’s disease symptoms, they may negatively affect a person’s quality of life if they do occur. Involuntary mouth movements may affect speech, chewing patterns, and facial expressions.

Experts recommend that individuals experiencing new or worsening involuntary mouth movements contact a healthcare professional. Effective treatment may help people with Parkinson’s disease manage these and other symptoms.

Hemifacial spasm (facial hemispasm) - treatment, symptoms, causes, diagnosis

Hemifacial spasm was first described by Gowers in 1884, and is a segmental myoclonus of the muscles innervated by the facial nerve. The disease occurs at the age of 50-60 years, almost always on the one hand, although sometimes, in severe cases, there is a bilateral lesion. Hemifacial spasm usually begins with short clonic movements of the circular muscle of the eye and over several years covers other muscles of the face (frontal, subcutaneous, zygomatic, etc. ).

).

Clonic movements gradually progress to sustained tonic contractions of the muscles involved. Chronic irritation of the facial nerve or nucleus (which is considered the main cause of hemifacial spasm) can occur due to various reasons.

The muscles of the face are subject to the same movement disorders as the muscles of the limbs or trunk. Myoclonus, dystonia and other movement disorders manifest as specific syndromes in the facial muscles. A clear understanding of the mechanism of development of disorders allows for the correct diagnosis and selection of adequate treatment.

Causes of hemifacial spasm include: vascular compression, nerve mass compression, brainstem lesions from stroke or multiple sclerosis, and secondary causes such as trauma or Bell's palsy.

Although there are various treatments for craniofacial movement disorders, botulinum toxin-assisted chemodenervation has proven to be very effective in treating these disorders, outperforming both medical and surgical treatment in some cases.

Irritation of the nucleus of the facial nerve is believed to lead to hyperexcitability of the nucleus, while irritation of the proximal nerve can lead to epaptic transmission within the facial nerve. This mechanism explains the rhythmic, involuntary myoclonic contractions that are seen in hemifacial spasm.

Compressive lesions (eg, tumor, arteriovenous malformation, Paget's disease) and non-compressive lesions (eg, stroke, multiple sclerosis, basilar meningitis) may present with hemifacial spasm. Most cases of hemifacial spasm, which were previously considered idiopathic, were probably caused by abnormal blood vessels and compression of the facial nerve within the cerebellopontine angle.

Epidemiology

Hemifacial spasm occurs in people of different races with the same frequency. There is some predominance of this disease in women. Idiopathic hemifacial spasm usually develops in the fifth or sixth decade of life. The development of hemifacial spasm in patients younger than 40 years of age is unusual, and is often a symptom of a neurological disease (eg, multiple sclerosis).

Symptoms

Involuntary facial muscle movements are the only symptom of hemifacial spasm. Fatigue, anxiety, or reading can speed up movement. Spontaneous hemifacial spasm is manifested by facial spasms, which are myoclonic spasms and are similar to segmental myoclonuses that can occur in other parts of the body. Post-paralytic hemifacial spasm, such as after Bell's palsy, manifests as facial synkinesis and contracture.

There are a number of conditions similar to hemifacial spasm.

Masticatory muscle spasm

Masticatory muscle hemispasm is similar to hemifacial spasm and occurs when the motor trigeminal nerve is irritated. This is a rare condition representing segmental myoclonus, and is manifested by unilateral involuntary contractions of the muscles innervated by the trigeminal nerve (masticatory). As with hemifacial spasm, masseter hemispasm is well treated with medication and botulinum toxin. In addition, there is evidence that surgery may be effective in some cases.

Myoclonic movements

Myoclonic movements in the facial muscles can also occur with lesions of the brain or brainstem. They differ from hemifacial spasm in the distribution of abnormal movements (more generalized, possibly bilateral) and may be diagnosed by neurophysiology. Imaging may reveal deeper causes. Central myoclonus responds well to anticonvulsant therapy.

Oromandibular dystonia

Oromandibular dystonia is a muscular dystonia affecting the lower muscles of the face, predominantly the jaw, pharynx and tongue. If oromandibular dystonia occurs in combination with blepharospasm, then this is called Mej's syndrome.

Botulinum therapy is most effective in the treatment of oromandibular dystonia. Medications are also used to some extent for oromandibular dystonia.

Craniofacial tremor

Craniofacial tremor may be associated with essential tremor, Parkinson's disease, thyroid dysfunction, electrolyte imbalance. This condition rarely occurs in isolation. Focal motor seizures must sometimes be distinguished from other facial movement disorders, in particular hemifacial spasm. Postictal weakness and greater involvement of the lower face are hallmarks of focal motor seizures.

This condition rarely occurs in isolation. Focal motor seizures must sometimes be distinguished from other facial movement disorders, in particular hemifacial spasm. Postictal weakness and greater involvement of the lower face are hallmarks of focal motor seizures.

Facial chorea

Facial chorea occurs in the context of a systemic movement disorder (eg Huntington's disease, Sydenham's chorea). Chorea is an episodic complex of movements without a pattern. A similar condition, spontaneous orofacial dyskinesia, occurs in older people without teeth. As a rule, the installation of prostheses gives a good effect.

Tics

Facial tics are short, repetitive, coordinated spontaneous movements of the grouped muscles of the face and neck. Tics may occur physiologically or in association with diffuse encephalopathy. Some drugs (eg, anticonvulsants, caffeine, methylphenidate, antiparkinsonian drugs) may cause tics. Single, repetitive, stereotyped movements are characteristic of tics.

Facial myokymia

Facial myokymia is manifested by vermicular twitches under the skin, often with an undulating distribution. This condition differs from other abnormal facial movements by characteristic discharges on the EMG, which are short, repetitive bursts of motor unit potentials in the range of 2-60 Hz, with periods of silence up to several seconds. Myokymia of the face can occur with any process in the brain stem. Most cases of facial myokymia are idiopathic and resolve on their own within a few weeks.

Diagnosis

Early cases of hemifacial spasm can sometimes be difficult to distinguish from facial myokymia, tics, or myoclonus, which may be caused by pathological processes in the cerebral cortex or brainstem. In such cases, the most valuable diagnostic method is neurophysiological testing.

Wide and variable synkinesia on blink tests and high-frequency discharges on electromyography (EMG) with appropriate clinical features are diagnostic criteria for hemifacial spasm. Stimulation of one branch of the facial nerve can spread and cause a response in the muscle innervated by the other branch. Synkinesia is absent in essential blepharospasm, dystonia, or epilepsy. Needle myography shows irregular, short, high frequency bursts of potentials (150-400 Hz) of motor units that correlate with clinically observed facial movements.

Stimulation of one branch of the facial nerve can spread and cause a response in the muscle innervated by the other branch. Synkinesia is absent in essential blepharospasm, dystonia, or epilepsy. Needle myography shows irregular, short, high frequency bursts of potentials (150-400 Hz) of motor units that correlate with clinically observed facial movements.

Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging is the diagnostic method of choice when there is a need to exclude compression. Angiography of cerebral vessels is usually of little value in diagnosing hemifacial spasm. Ectasized blood vessels are rarely identified, and these findings (changes) in the vessels can be difficult to correlate with nerve exposure. Performing angiography and/or magnetic resonance angiography is usually used to perform surgical vascular decompression.

Treatment

For most patients with hemifacial spasm, electromyography (EMG) guided botulinum toxin is the treatment of choice. Chemodenervation is safe and has a good healing effect in most patients, especially those with sustained contractions. The disappearance of spasms occurs 3-5 days after the injection and lasts about 6 months.

The disappearance of spasms occurs 3-5 days after the injection and lasts about 6 months.

Drugs used in the treatment of hemifacial spasm include carbamazepine and benzodiazepines (for non-compressive lesions). Carbamazepine, benzodiazepines, baclofen may also be used in patients who refuse botulinum toxin injections. Compression injuries must be treated surgically. Microvascular surgical decompression may be effective for those patients who do not respond to botulinum toxin injections.

Botulinum toxin injections

Botulinum toxin injections are performed under EMG control. Side effects of toxin injections (eg, facial asymmetry, ptosis, facial muscle weakness) are usually temporary. Most patients note a good therapeutic effect from the introduction of the toxin. Medications may be used early in the development of hemifacial spasm or in patients who refuse to receive botulinum toxin.

The most effective drugs are carbamazepine and benzodiazepines (eg clonazepam). Often, the effectiveness of the drug decreases over time, requiring more aggressive treatment.

Often, the effectiveness of the drug decreases over time, requiring more aggressive treatment.

Surgical decompression is used when there is pressure on the nerve.

Nervous tic. Causes and treatment

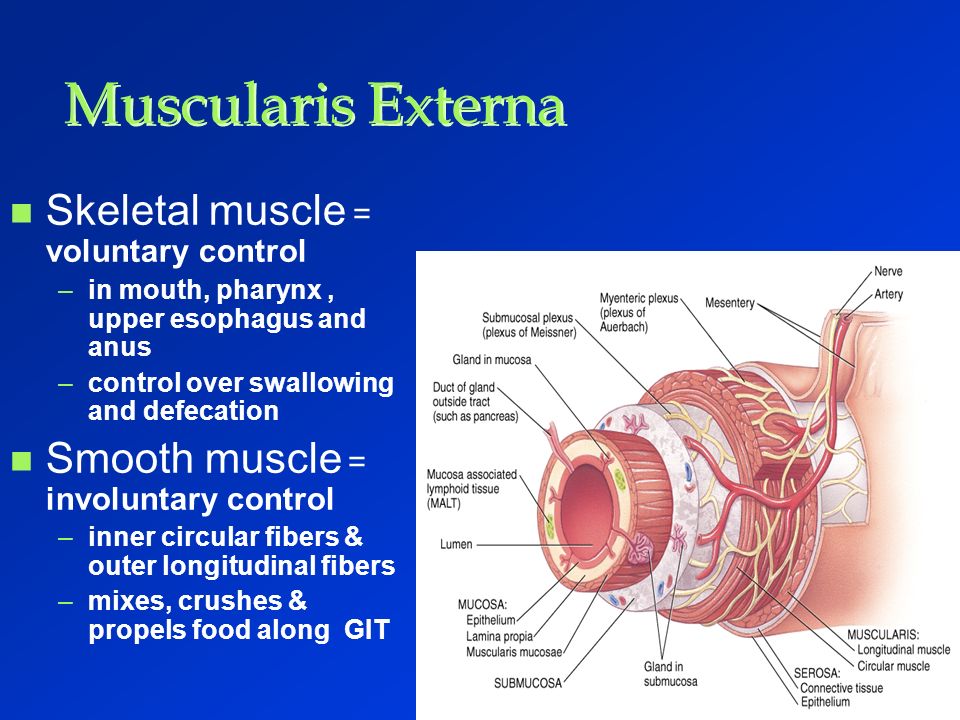

A tic is an accelerated, repetitive contraction of certain muscles, most commonly the face or arms. A nervous tic may look like a normal purposeful human movement, but in this case they are absolutely devoid of practical need. A nervous tic occurs without the "permission" of a person, only in the waking state and can rarely be suppressed by the will of the owner. Nervous tics are chaotic.

Automation of our movements without the participation of the cerebral cortex is handled by the extrapyramidal system of the brain. Excessive excitement in this area leads to the appearance of a tick, as one of the symptoms of an increase in the activity of the extrapyramidal system.

Most often, nervous tics appear in the mimic muscles of the face, for example, in twitching of the eyelids. Almost every person who has experienced psycho-emotional stress is familiar with this symptom. In this case, a person can be absolutely healthy. A separate group prone to the appearance of tics is children aged 2-10 years.

Almost every person who has experienced psycho-emotional stress is familiar with this symptom. In this case, a person can be absolutely healthy. A separate group prone to the appearance of tics is children aged 2-10 years.

Nervous tics may be primary (pass as quickly as they started without medical intervention). The main causes of primary nervous tics in adults are frequent severe stress, exhaustion of the nervous system, and chronic fatigue.

There are many more reasons for the appearance of secondary nervous tics. These are (neuro-circulatory) dystonia, diabetes mellitus, kidney and liver diseases, brain tumors, injuries received during childbirth, trigeminal neuralgia, mental illness. This also includes past infectious diseases, the result of taking medications, carbon monoxide poisoning, etc.

Hereditary nervous tics are called Terett's disease. It affects children whose parents suffer from this pathology. The probability of transmission of the disease is 50%, while the severity of the course can be different and weaken with age.

In the reproduction of nervous tics, one muscle group or several may take part, in which case they are called complex. In addition, a nervous tic can begin in one location, and then affect more and more muscles incrementally. Such a nervous tic is called generalized.

The most common are mimic nervous tics: blinking, blinking, twitching of the nose, head, tongue sticking out, licking.

Motor nervous tics - involuntary movement of limbs: shrugging shoulders, throwing legs forward, clenching fists, etc.

Vocal tics: whistling, squeaking, clattering tongue, coughing, clearing throat, grunting, etc.

With sensory tics, a person feels discomfort in some part of the body and, as a result, makes involuntary movements.

Complicated nervous tics include: repetition of gestures, snapping fingers, rubbing certain places, jumping, repetition of abuse, simple, already said own or other people's words.

Diagnosis of nervous tics includes a blood test to detect inflammatory changes in the body.