Weather affecting moods

Weather and Mood: Unpacking the Connection

“Rainy day blues.” “Sunny disposition.” “A face like thunder.” “Under the weather.”

The English language is full of nods to the many ways weather can affect mood, energy, and even mental functioning.

Of course, your relationship to the environment likely isn’t so simple as “cold = bad” or “warm = good.”

If you live in a desert climate, a chilly, breezy day could offer a nice change of pace. Likewise, the hot, humid days of summer could feel downright miserable if you bike or walk to work.

Personal preference also has much to do with how the weather affects you. According to older research from 2011 that involved 497 adolescents and their mothers, people tend to fall into one of four categories:

- Summer lovers: Your mood improves in warm and sunny weather.

- Summer haters: Your mood declines in warm and sunny weather.

- Rain haters: Your mood declines on rainy days.

- Unaffected: Weather doesn’t affect your mood much.

Individual differences aside, weather and climate do affect people in a few main ways.

Read on to learn how weather can affect your emotions, who might be most sensitive to weather changes, and how climate change can impact mental health.

Weather can influence your mental health in many ways:

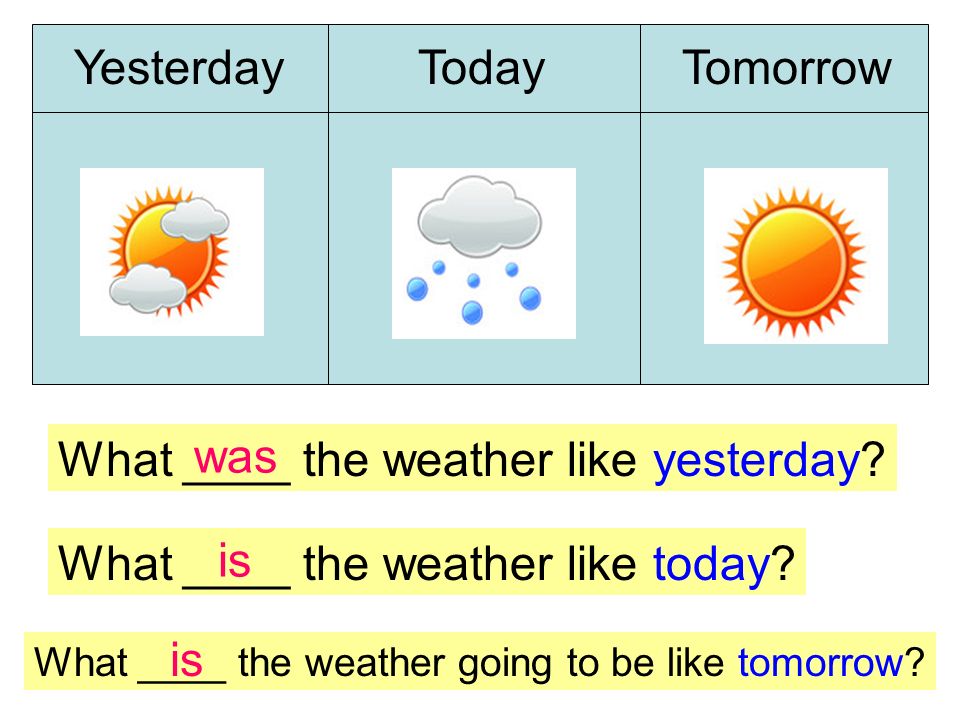

Mood

The following weather conditions are associated with low and high mood for most people:

| Low mood | High mood |

| low temperatures (below 50°F / 10°C) or high temperatures (above 70°F / 21°C) | mid-range temperatures, usually between 50°F and 70°F (10°C and 21°C) |

| high humidity | high atmospheric pressure and clear skies |

| precipitation and fog | sunlight |

Energy

Typically, cold weather gives your body the signal to settle down and “hibernate,” resulting in less energy during the winter months. Warmer temperatures can boost your energy along with your mood, but only up to the 70°F (21°C) threshold. After that, you may grow tired and feel the urge to escape the heat.

Warmer temperatures can boost your energy along with your mood, but only up to the 70°F (21°C) threshold. After that, you may grow tired and feel the urge to escape the heat.

Sunlight also impacts energy: Light tells your circadian clock to stay awake, and darkness tells your brain it’s time to rest. In other words, long, bright days can energize you. But on short or cloudy days, there’s less light to encourage you to stay awake, so you may feel groggier than usual.

Stress

If you’ve ever gotten a tingly, uneasy feeling before a storm, that was likely your body sensing a drop in atmospheric pressure. A 2019 animal study suggests drops in atmospheric pressure can activate the superior vestibular nucleus (SVN), a part of your brain that controls balance and perception. This study involved mice, but humans also have an SVN.

The study authors suggest SVN may rile up your body’s stress system before a storm, making you feel on edge. Circulating stress hormones can also sensitize your nerve endings, which could be why some people get chronic pain flare-ups when the air pressure is low.

High temperatures can also increase stress levels. Older research suggests people tend to be more irritable, or even aggressive, during hotter months. Research from 2018 links higher temperatures to increased agitation and anxiety.

Ability to think clearly and make informed decisions

Warm, sunny weather may affect brainpower by:

- boosting your memory

- helping you feel more open to new information

- improving inattentiveness, if you have ADHD

Warm weather also tends to make people more tolerant of financial risk. If you find yourself making more impulsive investments or purchases during hotter months, the weather may be one of the reasons why.

It’s worth mentioning these effects only occur if you actually go outside. Simply looking out of the window on a sunny day probably won’t have much impact.

Suicide risk

Evidence suggests people are more likely to attempt suicide in the spring and early summer than any other season. Researchers don’t know exactly why this pattern occurs, although they have a few theories:

Researchers don’t know exactly why this pattern occurs, although they have a few theories:

- More sunlight exposure and solar radiation may prompt a shift in neurotransmitter levels.

- Rapidly rising temperatures could trigger a mood episode, particularly for people with bipolar disorder.

- High pollen counts may prompt inflammation in the brain and worsen mental health symptoms.

While weather changes alone likely won’t prompt someone to attempt suicide, it could serve as an additional trigger for someone already at risk.

Having thoughts of suicide?

If you’re thinking about suicide, know you’re not alone.

You can get free, confidential support 24/7 from trained crisis counselors by dialing 988 to reach the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline.

If you prefer text-based support, just text “HOME” to 741-741 to reach the Crisis Text Line.

For plenty of people, weather has only a trivial effect on mental and physical health. However, for the 30% of people who live with meteoropathy, shifts in weather can cause symptoms like:

- irritability

- migraine

- insomnia

- trouble concentrating

- pain around old scars or injuries

These symptoms disappear when the weather improves.

Meteoropathy most commonly affects:

- women

- older adults

- people with high levels of the personality trait neuroticism

- people who have a diagnosed mood disorder

Meteoropathy isn’t a diagnosis in itself, but it can worsen mood symptoms.

Weather also has an acknowledged role in the following conditions:

Seasonal depression

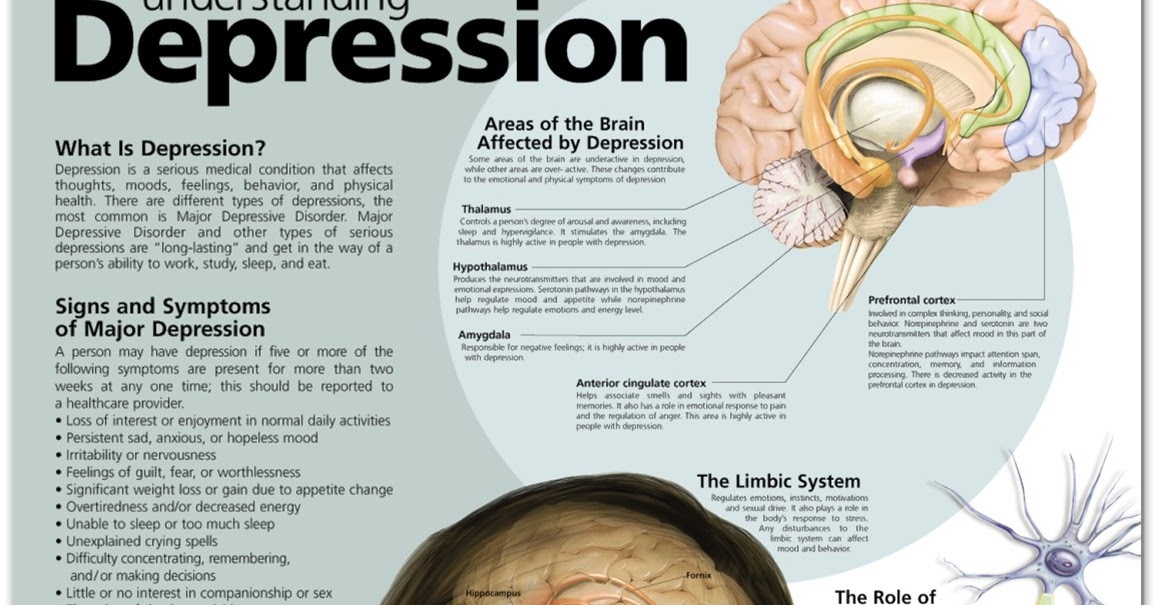

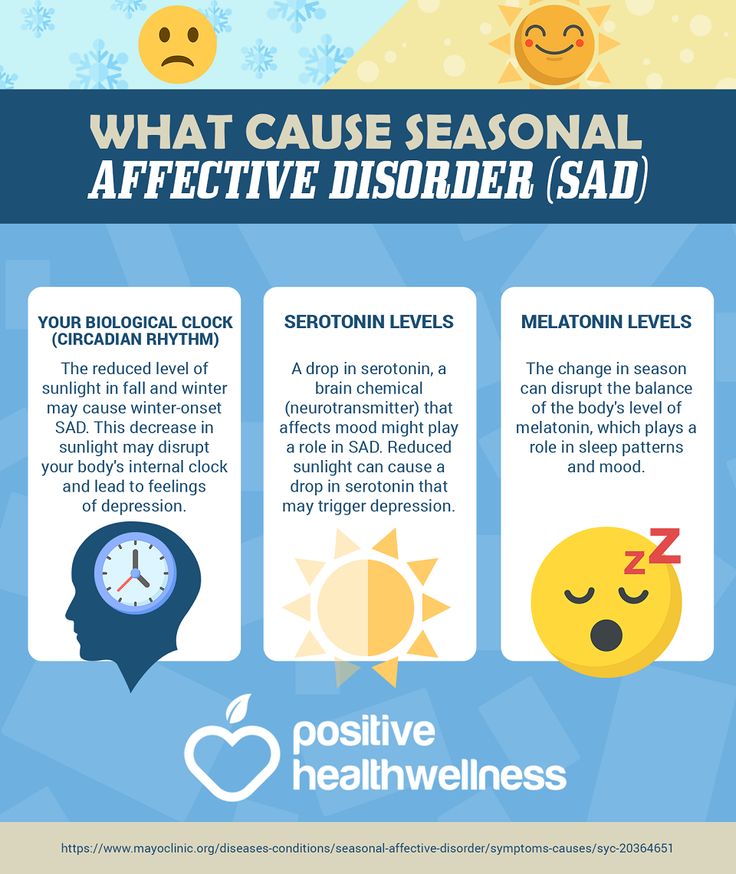

Major depressive disorder (MDD) with a seasonal pattern, which you might know as seasonal affective disorder (SAD), refers to depression symptoms that appear only during certain times of the year.

Most people with this type of depression experience symptoms like sadness, sleepiness, and increased appetite during the fall and winter months, but no symptoms in the spring and summer.

But some people with seasonal depression have symptoms that follow the opposite pattern: The warm, sunny weather of spring and summer triggers depression symptoms, and the colder winter months bring relief. Spring or summer depression symptoms may involve agitation, insomnia, and poor appetite, along with a low mood.

Major depression

Major depression can occur at any time of year. That said, symptoms may show up more frequently during chillier weather.

According to an Eastern European study of nearly 7000 participants, you’re more likely to have depression symptoms:

- during November or December

- when the temperature falls below 32°F (0°C)

- when the wind speed is higher than on previous days

- if it snowed within the last 2 days

Bipolar disorder

Roughly 1 in 4 people with bipolar disorder report a seasonal pattern in their mood symptoms. Temperature seems to serve as the key link between seasonality and bipolar symptoms.

While study results vary, there’s some general consensus: Episodes of depression occur more frequently in winter, and episodes of mania occur more frequently in spring and summer.

Research from 2020 also suggests that among people with bipolar disorder, those with a history of suicide attempts tend to have greater sensitivity to weather and more severe meteoropathy symptoms. Participants with a greater number of suicide attempts had higher scores on meteoropathy screening tests.

Participants with a greater number of suicide attempts had higher scores on meteoropathy screening tests.

Extreme weather impacts almost everyone, not just people prone to meteoropathy. According to a 2016 study, temperatures above 70°F (21°C) can:

- decrease desirable emotions, like joy

- increase unwanted emotions, like anger

- contribute to fatigue

The study found that individuals in both mild climates and harsh climates had much the same reactions to heat exposure. To put it another way, as climate change increases the number of hot days each year across the United States, moving to a cooler state probably won’t protect you.

Research from 2017 has also linked the rising temperatures of climate change to increasing levels of violence around the globe. As temperatures get hotter, stress, impulsivity, and aggression rise. Droughts and crop shortages can also cause more competition for resources.

Increased stress, aggression, and impulsivity may then play a part in more frequent collective violence, like riots and civil wars. But they can also factor into interpersonal violence, which could include assault, homicide, or sexual assault.

But they can also factor into interpersonal violence, which could include assault, homicide, or sexual assault.

One theory suggests temperature changes that affect everyday activities can heighten tension and contribute to interpersonal conflict, which can affect interactions with strangers, partners, and loved ones.

Extreme weather events

Climate change doesn’t only affect temperatures. It has also increased the rate of extreme weather events (EWEs), such as floods, hurricanes, and wildfires. These events can disrupt your life significantly and may cause mental health symptoms.

According to a 2020 review including 17 studies where participants had experienced an EWE in the past 12 months,

- 19.8% of the participants experienced symptoms of anxiety

- 21.4% of the participants experienced symptoms of depression

- 30.4% of the participants experienced symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

Children’s mental health is particularly vulnerable after EWEs. Up to 71% of child survivors of natural disasters develop post-traumatic stress symptoms.

Up to 71% of child survivors of natural disasters develop post-traumatic stress symptoms.

Even people not directly exposed to EWEs may feel anxious hearing about them. For some people, the existential threat of climate change can cause a sense of dread and hopelessness called eco-anxiety. As climate change has accelerated, eco-anxiety has become more common, especially among younger generations who will have to deal with the long-term effects.

You can’t change the weather, but you can take steps to ease its effects on your well-being.

If you suspect you might be sensitive to weather changes, consider these tips:

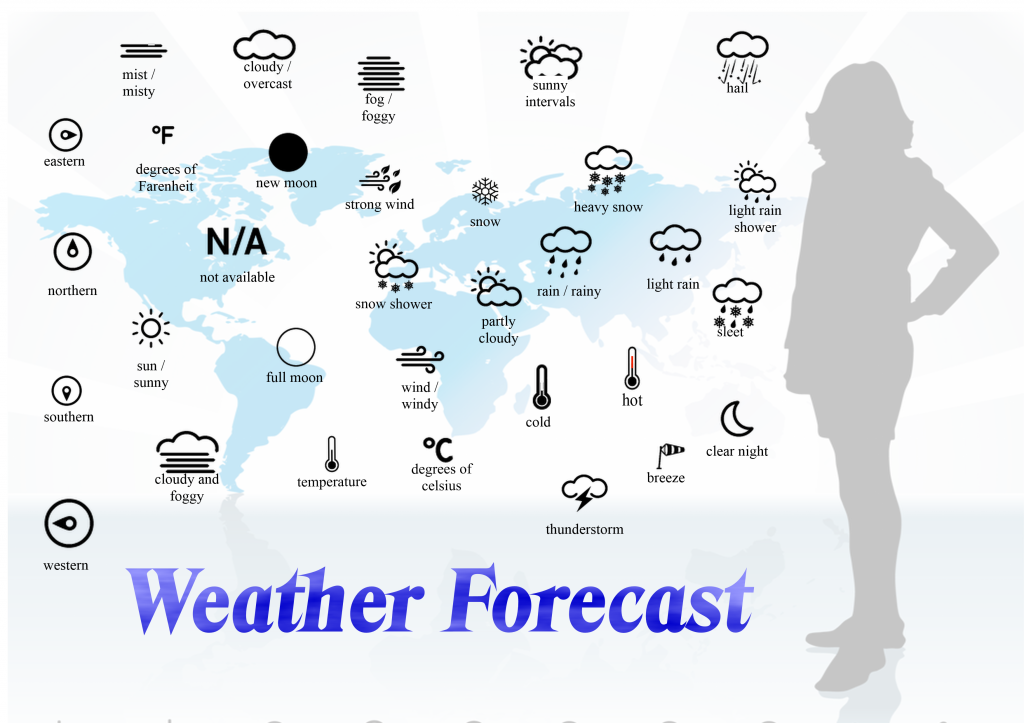

- Keep a mood journal so you can track how different weather patterns affect you.

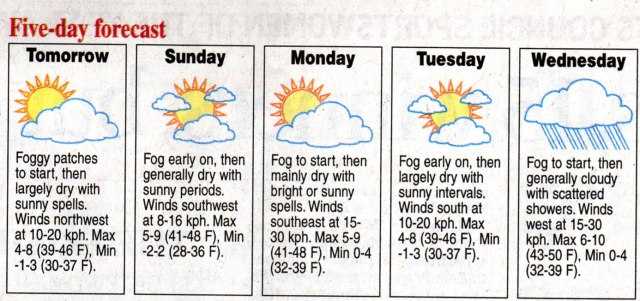

- Monitor the weather forecast so you can prepare low-stress schedules for difficult days.

- Stay inside during harsh weather. If your home doesn’t have heating or air conditioning, you may want to visit your nearest emergency warming or cooling center.

Meteoropathy typically lasts for a few days at most and will disappear once the weather improves. These symptoms can feel annoying or uncomfortable, but they generally won’t completely derail your everyday routine.

These symptoms can feel annoying or uncomfortable, but they generally won’t completely derail your everyday routine.

That said, it never hurts to check in with a healthcare professional if the weather seems to have an ongoing impact on your mood. They can help rule out any underlying conditions and offer more guidance on treatment options.

If any mental health symptoms you experience do last more than a day or so, or keep you from doing the things you usually would, you may want to connect with a professional for more support.

Here’s how to find the right therapist.

If weather changes seem to trigger mental health symptoms for you, potential treatment options might include:

- For eco-anxiety: ecotherapy, support groups

- For MDD with a seasonal pattern: light therapy, therapy, antidepressants

- For major depression: therapy, antidepressants

- For bipolar disorder: therapy, mood stabilizers, antidepressants

Your care team can offer more guidance in finding the right treatment for your needs.

FYICertain medications can make you more sensitive to weather changes.

For example, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), a common type of antidepressant, can raise your risk of dehydration and heat stroke. People who take SSRIs are 17% more likely to get hospitalized for heat-related illness than the general population.

If you have concerns about any potential side effects of your medication, the clinician who prescribed it can answer your questions and offer guidance on alternate treatment options.

While the weather has only a subtle impact on mood, energy, and cognition for many people, nearly a third of the population is highly sensitive to atmospheric changes.

What’s more, climate change has increased the frequency of extreme weather events, leaving more people vulnerable to PTSD, depression, and anxiety related to natural disasters.

Working with a therapist to address your symptoms can have benefits on a personal level — but large-scale efforts to combat climate change may do more to help prevent weather-related traumas from happening in the first place.

Emily Swaim is a freelance health writer and editor who specializes in psychology. She has a BA in English from Kenyon College and an MFA in writing from California College of the Arts. In 2021, she received her Board of Editors in Life Sciences (BELS) certification. You can find more of her work on GoodTherapy, Verywell, Investopedia, Vox, and Insider. Find her on Twitter and LinkedIn.

Why Weather Affects Mood | Psychology Today

Even as many of us are trapped indoors due to the pandemic, our moods rise on bright days and plumb the depths after days of rain. Such transitory mood swings are not well understood but animal behavior offers useful insights.

Adaptive Inactivity

Low moods are demotivating. We feel lethargic, or tired, and are less likely to exert ourselves in new, or productive, activities. While we may feel listless, dispirited, and unhappy, this could boost the biological currencies of survival and reproduction.

We wake up when it gets bright in the morning so that our activities follow a rough circadian rhythm, as do internal physiological systems from digestion to immune function. For example, we eat less often in the nighttime because insulin production slows and less sugar is withdrawn from the bloodstream, which blunts hunger.

Knowledge about the restorative value of sleep is expanding by leaps and bounds, from its effects on immune function to memory and flushing the brain of impurities (1). Feeling tired encourages us to lie down and sleep each night.

The same sort of circadian rhythm is manifested in most other vertebrates although some, like owls, become active at night. Cycles of rest and activity are surprisingly flexible and shift workers are forced to reverse the usual pattern that can impose health costs. Similarly, species that are normally diurnal can shift to becoming nocturnal due to human influence, as is true of coyotes, boars, elephants, and tigers, who avoid unwanted human attention by becoming active at night.

There are strong seasonal patterns for some species that rest more in winter. Some go to the extreme of hibernating when they sleep in a warm den through much of the cold season. In spring, longer days rouse hibernators from their slumber and motivate some species to embark on their seasonal migration.

Light and Reproduction

These effects are illustrated by the way that day length alters the hormonal status of seasonal breeders like birds. With increased day length, migratory species become increasingly restless and head off in the direction of their seasonal migration.

In spring, as day length increases, male birds experience a surge in testosterone, fight over territories, and defend them with the territorial song. Singing is itself related to testosterone because song controlling structures of the brain wax and wane with the breeding system.

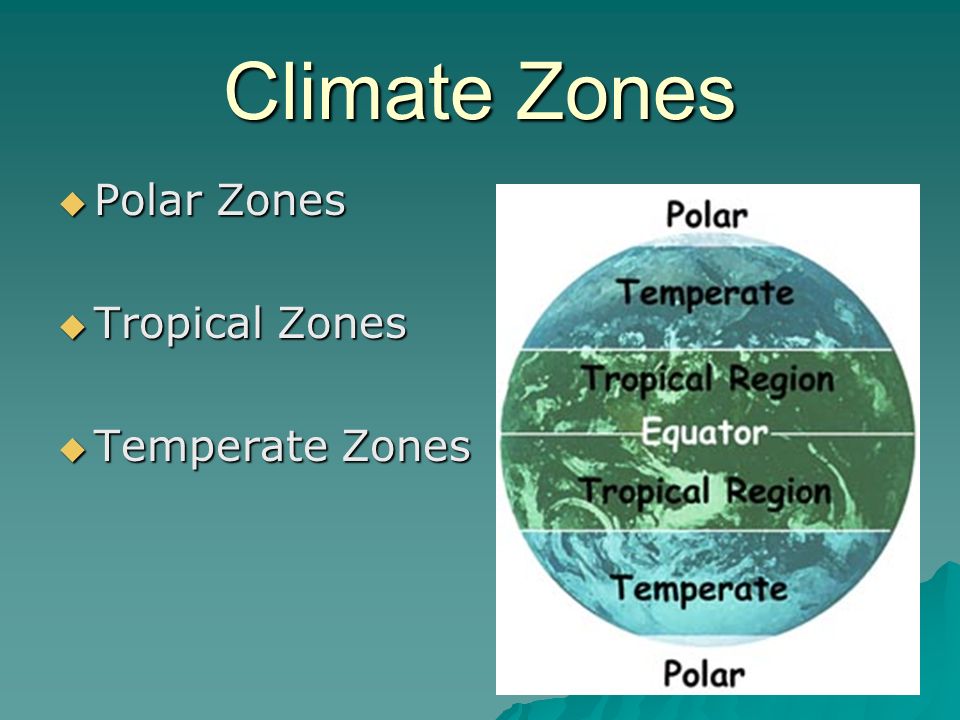

Humans are not seasonal breeders but our brains also have complex responses to day length. These are highlighted by the phenomenon of wintertime depression or seasonal affective disorder, that occurs in highly seasonal places distant from the equator where day length in winter is very short and triggers severe depression in vulnerable individuals.

Although we are not a seasonal species, our reproductive systems are affected by the length of days. Men have an annual cycle in circulating testosterone that peaks in autumn.

The Seasonal Shift

Most of us tolerate the short days of winter, although being confined at home due to extreme cold interferes with our customary activities and thereby lowers mood.

When temperatures warm up in summer, we spend more time outdoors and are more physically active whether this involves sports activities, exercise, or outdoor hobbies like gardening. Most people prefer milder temperatures and express greater feelings of optimism and joy.

One side effect of being outdoors longer is that violent crime rates go up. The fact that most civil unrest occurs in midsummer used to be attributed to extreme heat increasing irritability and aggression but there is no evidence of this. If anything, extreme heat makes us unwilling to move around, much less attack anyone.

The demotivating effect of extreme summer heat is similar to that of extreme winter cold. Both are stressful tending to increase anxiety and lower mood.

Stress and Precautionary Behavior

Extreme winter cold and extreme summer heat crimp everyday activities in similar ways. In cold climates, there is a temptation to stay indoors more and to get less exercise. When a person does brave the elements, they must spend time putting on extra winter gear that has to be removed on their return.

This is a time-consuming annoyance that we do not have when the weather is mild.

When the weather is hot, we have the trouble of putting on protective cream to prevent sunburn and wearing sun hats. Humid conditions are highly uncomfortable and demotivating. This means that we spend more time in air-conditioned buildings and vehicles and spend less time outdoors.

Whether hot or cold extreme conditions can be highly unpleasant and demotivating. We must also spend a lot of money to control the environment in our homes. All of these aspects of extreme weather make them potentially stressful, anxiety-provoking, and depressing.

All of these aspects of extreme weather make them potentially stressful, anxiety-provoking, and depressing.

Despite this, there is surprisingly little evidence that climate has any reliable impact on mood or mental health. There is a very simple explanation for this which is that we are good at adapting to the particular conditions in which we find ourselves.

Residents of Minnesota are accustomed to long, hard winters and many enjoy spending time outside pursuing winter activities such as skating and ice fishing. They are accustomed to the extreme cold and take it in their stride. There is also some physiological adaptation with greater bodily heat production after prolonged cold exposure.

So we encounter a strange paradox in which harsh weather is ostensibly stressful but has little obvious impact on mood because we are good at adapting to varied environmental conditions. This trait may be what allowed our ancestors to occupy Europe and Eurasia when they were in the grip of an ice age.

Weather and mood: is there a connection?

58621

Know Yourself

We believe that we are uplifted because the sun is shining in the morning, and, on the contrary, we are discouraged if the rain does not stop. We are sure that the weather directly affects our mood. Attempts to experimentally verify this conventional wisdom have been made repeatedly.

Researchers asked volunteers to record their emotional state several times a day for several months, and then compared the data obtained with weather reports for the same days. And... they didn't find any dependency!

David Watson, Professor of Psychology at the University of Iowa (USA), analyzed the results of twenty of the largest studies on the relationship between mood and weather, conducted since the early 1980s. It turned out that the more people participated in the experiments, the less the correlation turned out to be. In other words, psychological research refutes our intuitive conclusions: the weather and our mood are not connected in any way. What makes us believe otherwise?

What makes us believe otherwise?

Cultural stereotypes

Belief in a linear relationship between weather and state of mind comes from the distant past. The archaic view of the universe likened the inner world of man to the world of nature, and in this scheme, weather phenomena were assigned the same place that we usually assign to emotions.

Describing the sphere of feelings in this way, today we use the same words as when describing the weather: for example, the verbs “frown” and “clear up” are equally applicable to the sky and to a person’s face.

Since ancient times, people's lives have been regulated by the weather. “The sun played a special role,” says anthropologist Alexander Zubov. “It determined the rhythm of life, warmed it, made it possible to engage in gathering and hunting ... It was a source of life's blessings, and therefore all the great civilizations of antiquity, from the Aryans to the Aztecs, bowed before it.”

High spirits may be, for example, because when the weather is good, we go out more often

Today, our feelings are still influenced by traditional views and cultural stereotypes - stable and extremely simplified ideas about what is happening. If we are happy and the sun is shining outside the window, we will most likely try to attribute our excellent mood to it. But if it's raining outside, we just don't pay attention to the weather.

If we are happy and the sun is shining outside the window, we will most likely try to attribute our excellent mood to it. But if it's raining outside, we just don't pay attention to the weather.

“When a situation doesn't match our perceptions, we ignore it. This is how the mechanism of formation of stereotypes functions - prejudices, superstitions, social attitudes, - explains psychologist Margarita Zhamkochyan. - And vice versa, when we meet coincidences, we remember them, tell others about it.

In fact, we may be in high spirits, for example, because when the weather is good, we often leave the house to meet relatives and friends. This kind of social interaction always has a positive effect on us.”

Adapt to contrasts

About 60 thousand years ago, several groups of ancient people migrated from East Africa, eventually they and their descendants populated the entire globe. “Our ancestors were forced to adapt to new living conditions,” explains anthropologist Olga Artemova. “Their bodies learned to pick up any weather signals that could affect their lives. For example, low atmospheric pressure preceded a hurricane.

“Their bodies learned to pick up any weather signals that could affect their lives. For example, low atmospheric pressure preceded a hurricane.

In the genetic memory of subsequent generations, a sharp drop in pressure, causing a vague feeling of anxiety, was imprinted as a "premonition of a thunderstorm." This is how our sensitivity to weather changes developed.

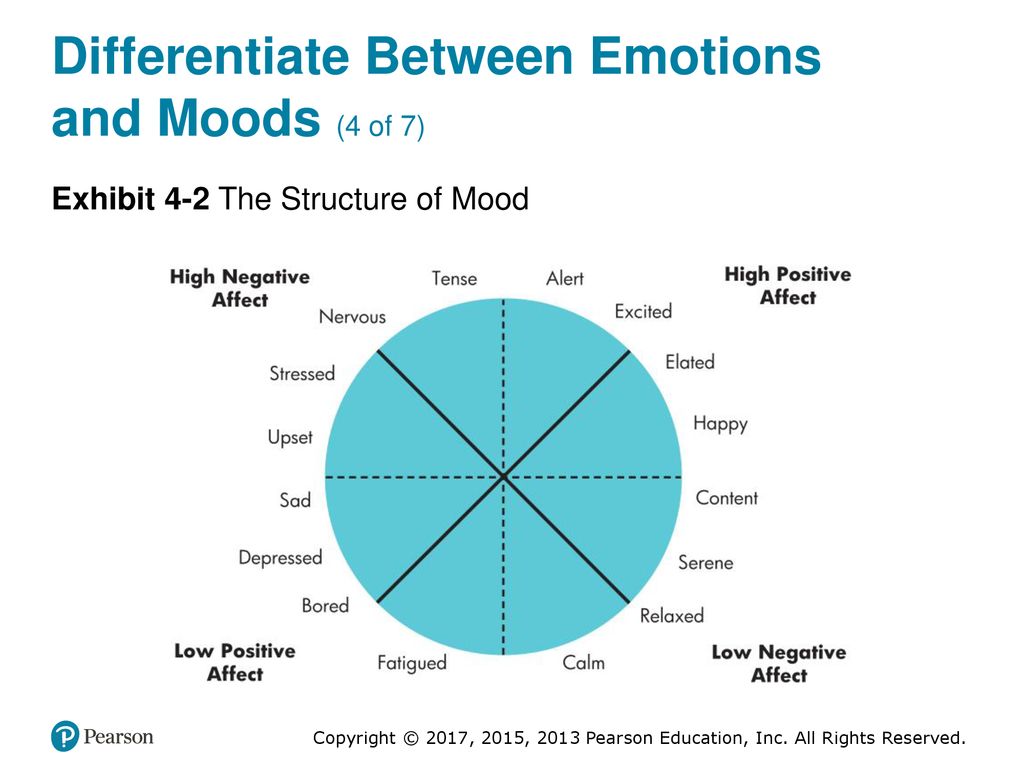

Mood is an emotional state that colors our lives, and it does not depend on specific circumstances. When we are in high spirits, we do not rejoice at something separately, but simply feel joy.

Mood can change several times even within one day, but its fluctuations or constant emotional background are seasonal and are primarily determined by the individual biological rhythm.

Why does the mood change then?

Most often, incomprehensible mood swings occur on autumn and winter days. But apathy, a feeling of depression are not connected with the weather, but are caused ... by a lack of light. The work of the body, including the nervous system, is determined by the stability of the day-night cycle. The better the light, the more serotonin, the hormone that regulates our mood, is produced.

The work of the body, including the nervous system, is determined by the stability of the day-night cycle. The better the light, the more serotonin, the hormone that regulates our mood, is produced.

When it is not enough, the libido and the ability to concentrate are reduced. “Scientists were able to identify a special type of nerve cells that register the amount of light perceived by the eyes and, in accordance with this, regulate the work of the internal biological clock,” says Margarita Zhamkochyan. “Morning light “starts” the work of these clocks.”

The natural biological alarm goes off when the receptors receive the right amount of light. In autumn and winter days, this becomes almost impossible.

Why do some of us react to changing weather with headaches, unreasonable anxiety, exacerbation of chronic diseases? Physicist Tatyana Breus explains the phenomenon of meteosensitivity as follows: “Our body is a complex coordinated system of various rhythms – cardiac, vascular, respiratory. A sharp change in air temperature, atmospheric pressure or wind strength, increased solar activity can bring the body out of a state of stable equilibrium. And we feel emotional and physical discomfort.”

A sharp change in air temperature, atmospheric pressure or wind strength, increased solar activity can bring the body out of a state of stable equilibrium. And we feel emotional and physical discomfort.”

Only 3% of the adult population has such an acute reaction to the weather. After all, weather sensitivity is a natural physiological phenomenon, thanks to which the body can adequately respond to changes in the external environment, which allows us to live in harmony with the world.

For some, the process of adaptation occurs almost imperceptibly, for others it takes more time. A painful reaction to the weather is an individual feature of those who inherited a special sensitivity of the central nervous system to the activity of the sun, or those whose body is severely weakened.

Text: Yuliana Puchkova, Zhanna Sandaevskaya Photo source: Getty Images

New on the site

Artemis, Hera, Demeter: 3 archetypes of phallic women - an analysis with psychologists

Hidden messages: how a man and a woman see the first dates - the opinion of psychologists

"Verunchik, do me a favor!" Why is it dangerous to be trouble-free

“I found out that my partner subscribed to his ex-wife in social networks. How to understand his act?

How to understand his act?

“I am always looking for illnesses in myself”: who suffers from hypochondria and how to get rid of it

Everyday life of a waiter: what they really are

March 8: what you need to know about the holiday in the XXI century - a historical analysis The psychologist told why the weather affects our mood | Society news

He also explained how to minimize this influence

The influence of weather on a person's mental state has probably been known since ancient times. In the spring, when the sun warms up, we want romance and follies, and when it's cold or cloudy, many people feel like wrapping themselves in a warm blanket and not leaving the house at all. When it’s clear outside, they talk about a “sunny” mood, and when a gloomy rain sets in, then, as a rule, it’s rainy in the soul.

Why is the mental attitude of many people so dependent on climatic conditions? We are talking about this with a clinical psychologist, the founder of the school of psychological combat "Valaal" Valery Ivanovsky.

— Valeriy Valeryevich, the weather affects the mood of people – this is an objective fact. What, in your opinion, are the reasons for the influence of climatic conditions on the human psyche?

— The influence of weather on the human body is, in a certain sense, a banality. I mean the impact is really there; there is even such a term - weather-sensitive people. But how it happens is another question.

In order not to delve into completely unnecessary details, as a thesis, we will carry out the following idea: as a result of millions of years of biological evolution, a person has formed a mechanism of adaptation close to perfection to the influence of the external environment, including weather changes. There is the autonomic nervous system, which is responsible for the work of the finest apparatus for setting the functioning of our body: it regulates the pulse, pressure, metabolism and other important processes. This unique system allows a person in almost any climatic conditions to be at the optimum of their physical and mental capabilities. Well, social evolution and scientific and technological progress made it possible for a person to survive in extreme conditions: for example, in deserts, at the North Pole or in Antarctica.

Well, social evolution and scientific and technological progress made it possible for a person to survive in extreme conditions: for example, in deserts, at the North Pole or in Antarctica.

The above, I think, can be the strongest argument regarding the influence of weather on the human psyche: it certainly exists, but its scale, I suppose, is minimal.

— But why then do many people, in simple terms, mope in cloudy and rainy weather, in the cold?

— That's right, and there's a lot of talk about the sun, vitamin D deficiency, and many other things. I think that the entire information background around this is connected with one unique feature of a person: he simultaneously exists, as it were, in two worlds. The first world is biological, in which physiological needs (food, safety, procreation) and ancient instincts rule. It is absolutely utilitarian and logical, everything is linear here, there are no abstractions.

The second world is man-made and social, in which a person, in fact, stays most of the time. This reality functions according to other laws, different from biological ones, and often conflicting with them. The beginning of the social world is given by two basic things: a collective mode of existence and one of its main phenomena - speech. On the one hand, it is a kind of comprehensive means for a person to interact with the world and himself, on the other hand, it is speech that creates a certain picture of the world in the human mind, a kind of cast from the surrounding reality.

This reality functions according to other laws, different from biological ones, and often conflicting with them. The beginning of the social world is given by two basic things: a collective mode of existence and one of its main phenomena - speech. On the one hand, it is a kind of comprehensive means for a person to interact with the world and himself, on the other hand, it is speech that creates a certain picture of the world in the human mind, a kind of cast from the surrounding reality.

The highlight is that in most cases a person interacts not with the real external world, but with its mental projection, a picture formed in his mind. It seems to be superimposed on the existing reality, but at the same time it can be much more diverse and bizarre. Let me put it simply: in this individual picture of the world, there may be things that simply do not exist in objective reality - they are generated by some whims of our consciousness. But a person perceives these abstractions of his mental picture of the world as part of objective reality!

- Wouldn't you like to say that spring romance or autumn melancholy is most often not the physical impact of some natural fluids, but social learning?

- In our previous conversations, we talked about the fact that a person from birth to seven years, in the so-called sensitive period, uncritically absorbs the picture of the world from his parents. Or, in other words, it captures their patterns of behavior, reactions to certain events, emotional attitude to the world around them and to themselves. In the process of life, this picture is improved, supplemented by various fragments, which we call life experience. In this regard, I will assume that mental reactions to the weather in many cases, paradoxically as it may seem, are dictated not by physical influence, but by those social patterns of behavior that a person learned during a sensitive period. For example, if the parents were "moping" in the fall, then the child is highly likely to do the same. And if he “captured” in childhood that the sun should be rejoiced, then he does this in adulthood.

Or, in other words, it captures their patterns of behavior, reactions to certain events, emotional attitude to the world around them and to themselves. In the process of life, this picture is improved, supplemented by various fragments, which we call life experience. In this regard, I will assume that mental reactions to the weather in many cases, paradoxically as it may seem, are dictated not by physical influence, but by those social patterns of behavior that a person learned during a sensitive period. For example, if the parents were "moping" in the fall, then the child is highly likely to do the same. And if he “captured” in childhood that the sun should be rejoiced, then he does this in adulthood.

I think that my thesis is confirmed by the variability of mental reactions to weather phenomena. Some, for example, love to walk in the rain, while others cannot be pulled out of the house at this time. Some like warmth, others prefer cool. Some like the sea air, others dream of living in the forest. And if there were some linear dependence of the state of the human psyche on climatic conditions, it seems to me that there would be no such diverse reactions.

And if there were some linear dependence of the state of the human psyche on climatic conditions, it seems to me that there would be no such diverse reactions.

In this context, I want to remind you about the placebo effect: when essential changes occur in the human body through external suggestion or self-hypnosis. It is also appropriate to recall the cortico-visceral theory developed by Konstantin Bykov - he developed the teachings of the great Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov about the influence of environmental factors on the processes occurring in the body through the cerebral cortex, which controls the higher mental functions of a person. The mechanism, I suppose, can be described as follows: it is raining, for example; the sense organs “deliver” this information to the human nervous system, it is refracted with the help of higher mental functions, after which the social template is turned on. That is, one person runs for a walk in the rain for joy, another wraps himself in a warm blanket and mopes on the couch: it all depends on what attitude he captured in a sensitive period to this phenomenon.

— Are the so-called “larks” and “owls” from the same opera?

- I think so. Our life is determined by higher mental functions, and the most important stimulus that forms behavioral reactions is the word, suggestion. Behavior in this case is both motor reactions and mental patterns that are triggered by the pronunciation of certain keywords or the occurrence of certain environmental conditions. In the family of "larks" "owls" rarely grow up, and vice versa. That is, getting up at dawn or sleeping until noon is an exclusively social learning.

— At the end of the XIX century, a doctor from the USA Albert Leffingwell conducted a study : studying the statistics of births, murders and other crimes, suicides and insanities, he came to the conclusion that the peak of activity of all the above occurs in the spring and summer. His conclusions in 1904 confirmed the American psychologist and educator Edwin Dexter, noting that in the cold season the number of cases of drunkenness increases, morbidity and mortality increase. How can this be explained?

How can this be explained?

- Actually, this is another confirmation of what I said above: everything is tied to higher mental functions, which, depending on signals from the external environment, "launch" a certain social template. Because, I think, now there is no objective reason why you need to drink more in winter than in summer or spring. But if we consider the issue in a socio-historical retrospective, the answer can be found. For centuries, in many spheres of human activity (the same agriculture, for example), activity was manifested mainly in the warm season, and from late autumn to early spring, social life seemed to freeze for objective reasons. Perhaps that is why people are accustomed to "relax" during the period of forced rest. Now such a model, as we understand it, absolutely does not correspond to reality, but the pattern continues to live.

Psychiatrists will surely tell you that the peak of exacerbations of mental illness occurs in autumn and spring. However, this, I suppose, also confirms my thesis that human behavior is largely determined not by environmental factors, but by social patterns triggered by higher mental functions. Let's look at the situation from a different angle. A psychiatrist is educated at a medical school, but education is also a form of social template. That is, the future specialist is told in a directive form that this is exactly what happens and not otherwise. Well, doctors, in turn, can already inspire this thesis to their patients: they say, well, what do you want, spring, and your anxiety has increased. That is, probably, a kind of double infection occurs: a person communicates with relatives who, again, perceive the thesis uncritically (the doctor said!). It penetrates the media, fiction, cinema, eventually acquiring the features of social reality. As a result, few now doubt that exacerbations in mental patients SHOULD occur in the fall and spring. And they are happening!

However, this, I suppose, also confirms my thesis that human behavior is largely determined not by environmental factors, but by social patterns triggered by higher mental functions. Let's look at the situation from a different angle. A psychiatrist is educated at a medical school, but education is also a form of social template. That is, the future specialist is told in a directive form that this is exactly what happens and not otherwise. Well, doctors, in turn, can already inspire this thesis to their patients: they say, well, what do you want, spring, and your anxiety has increased. That is, probably, a kind of double infection occurs: a person communicates with relatives who, again, perceive the thesis uncritically (the doctor said!). It penetrates the media, fiction, cinema, eventually acquiring the features of social reality. As a result, few now doubt that exacerbations in mental patients SHOULD occur in the fall and spring. And they are happening!

Is this some sort of so-called self-fulfilling prophecy?

Absolutely right! This is exactly what the Soviet physiologist Pyotr Anokhin called the acceptor of the result of an action: that is, a certain event occurs because everyone is waiting for it. Here the Voronya Slobidka from Ilf and Petrov's "Golden Calf" comes to mind: after each of its inhabitants thought that it must certainly burn down, it did burn down.

Here the Voronya Slobidka from Ilf and Petrov's "Golden Calf" comes to mind: after each of its inhabitants thought that it must certainly burn down, it did burn down.

I think many psychiatrists will be critical of what I am about to say. However, it would be interesting to conduct an experiment: to completely exclude from the information field (and first of all from textbooks!) references to the spring-autumn exacerbations of mental illness. For some reason, it seems to me that in this case, the seasonality will “go away”: people will start to get sick evenly, including in winter and summer.

— It is believed that men and women react differently to weather events. Why?

— Of course, there are differences between the male and female body. As a rule, men are stronger and larger, they have a lower pain threshold. There are differences in the humoral regulation of various processes. All this, of course, has an impact on the perception of climatic conditions, but to a greater extent this is influenced, I think, not by physical, but by social factors. That is, the very patterns that we have already talked about. Well, maybe a woman will rejoice in the sun or be sad in the rain a little more emotionally than a man.

That is, the very patterns that we have already talked about. Well, maybe a woman will rejoice in the sun or be sad in the rain a little more emotionally than a man.

— Do I need to struggle with my own perception of the weather – for example, if in rain or cold you want to lie down and mourn, so much so that you don’t see anyone?

— There is a universal recipe for making your life qualitatively better: you need to approach any events and phenomena consciously. Mindfulness implies that in every current moment you are aware of the deepest motive of your moods and actions. And when you know this, there is a magical opportunity to choose whether to do it or not. That is, if a person understands the reasons for his winter blues, if he realizes that there are no objective reasons for this due to external factors, that this is just a thought inspired by the lifestyle of his ancestors, he himself chooses what to do with this blues. And this recipe - awareness of every moment of your life - is suitable for all occasions, and not just for solving the problem of perceiving the weather.