Bipolar and chronic back pain

People with Bipolar Disorder Feel Pain Differently

People with Bipolar Disorder Feel Pain Differently- Conditions

- Featured

- Addictions

- Anxiety Disorder

- ADHD

- Bipolar Disorder

- Depression

- PTSD

- Schizophrenia

- Articles

- Adjustment Disorder

- Agoraphobia

- Borderline Personality Disorder

- Childhood ADHD

- Dissociative Identity Disorder

- Narcissistic Personality Disorder

- Narcolepsy

- Oppositional Defiant Disorder

- Panic Attack

- Postpartum Depression

- Schizoaffective Disorder

- Seasonal Affective Disorder

- Sex Addiction

- Specific Phobias

- Teenage Depression

- Trauma

- Featured

- Discover

- Wellness Topics

- Black Mental Health

- Grief

- Emotional Health

- Sex & Relationships

- Trauma

- Understanding Therapy

- Workplace Mental Health

- Original Series

- My Life with OCD

- Caregivers Chronicles

- Empathy at Work

- Sex, Love & All of the Above

- Parent Central

- Mindful Moment

- News & Events

- Mental Health News

- COVID-19

- Live Town Hall: Mental Health in Focus

- Podcasts

- Inside Mental Health

- Inside Schizophrenia

- Inside Bipolar

- Wellness Topics

- Quizzes

- Conditions

- ADHD Symptoms Quiz

- Anxiety Symptoms Quiz

- Autism Quiz: Family & Friends

- Autism Symptoms Quiz

- Bipolar Disorder Quiz

- Borderline Personality Test

- Childhood ADHD Quiz

- Depression Symptoms Quiz

- Eating Disorder Quiz

- Narcissim Symptoms Test

- OCD Symptoms Quiz

- Psychopathy Test

- PTSD Symptoms Quiz

- Schizophrenia Quiz

- Lifestyle

- Attachment Style Quiz

- Career Test

- Do I Need Therapy Quiz?

- Domestic Violence Screening Quiz

- Emotional Type Quiz

- Loneliness Quiz

- Parenting Style Quiz

- Personality Test

- Relationship Quiz

- Stress Test

- What's Your Sleep Like?

- Conditions

- Resources

- Treatment & Support

- Find Support

- Suicide Prevention

- Drugs & Medications

- Find a Therapist

- Treatment & Support

By LaRae LaBouff on December 30, 2016

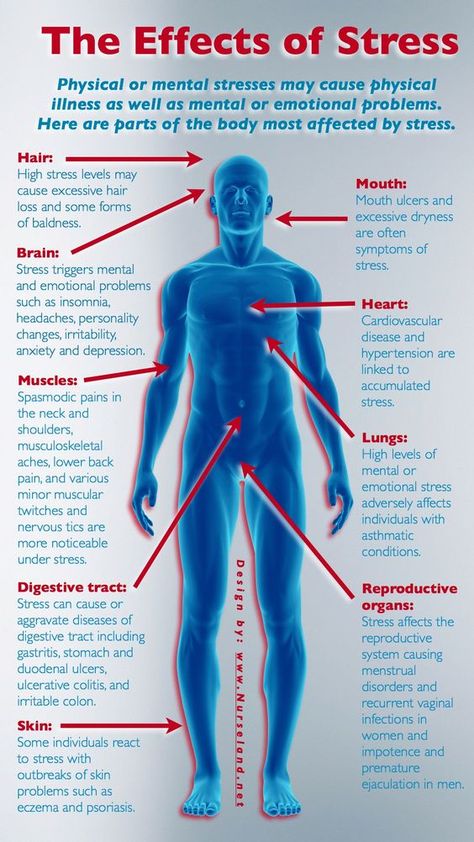

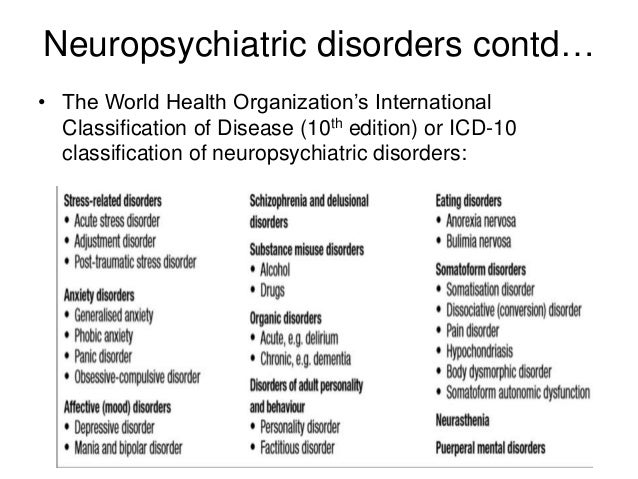

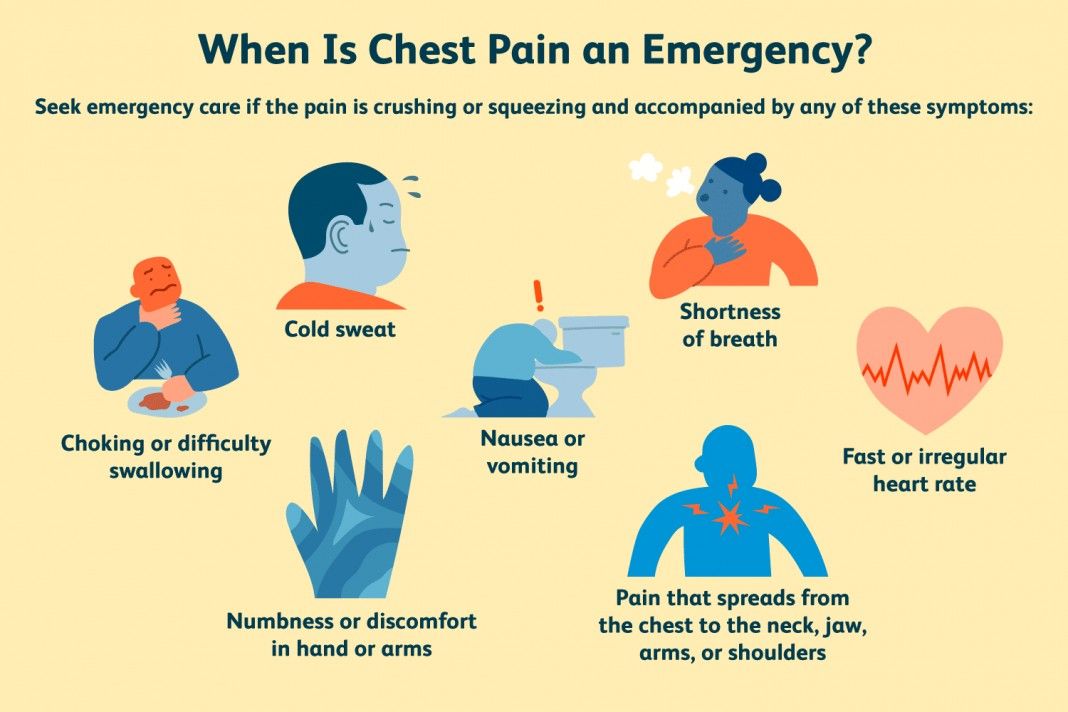

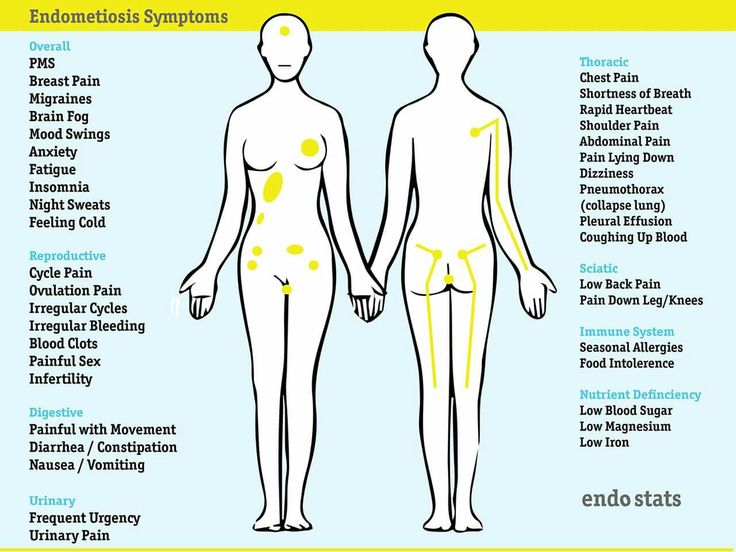

Pain in bipolar disorder is not limited to the psychological pain of depression or agitation. Physical pain is also a symptom of bipolar disorder, usually in the form of muscle aches and joint pain. There are also chronic pain illnesses linked to bipolar disorder like migraines, fibromyalgia and arthritis. Research has shown that the way the brain perceives physical pain overlaps with the network that processes psychological pain. A new study takes this a step further, showing evidence that people with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia perceive pain differently than the general population.

Scientists are still attempting to learn more about how humans perceive and process pain. It is an evolutionarily old process, making it difficult to study. From what evidence has been found, its thought the brain perceives pain in five steps:

- Contact with stimulus (pressure, cuts, burns, etc.)

- Perception (nerve endings sense the stimulus)

- Transmission (nerve endings send signals to the central nervous system)

- Pain center reception (the signal reaches the brain)

- Reaction (the brain sends back a signal for action)

Most pain sensation is dealt with in the spinal cord, but is also processed in the brain. Pain is perceived in the brain by the thalamus, anterior insular cortex, anterior cingulate cortex and the prefrontal cortex. Each of these areas can also be affected in bipolar disorder. The ACC has been linked to affect regulation and processing negative emotions, each of which have been shown to be dysfunctional in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Dysfunction in this area has also been linked to psychosis.

Pain is perceived in the brain by the thalamus, anterior insular cortex, anterior cingulate cortex and the prefrontal cortex. Each of these areas can also be affected in bipolar disorder. The ACC has been linked to affect regulation and processing negative emotions, each of which have been shown to be dysfunctional in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Dysfunction in this area has also been linked to psychosis.

The prefrontal cortex has been linked to both pain processing and bipolar disorder. In people who experience chronic pain, the prefrontal cortex appears shrunken in some patients. In bipolar disorder, the prefrontal cortex can also appear shrunken, especially when left untreated. In these cases, symptoms like problems with memory, emotional control, critical thinking and social functioning can be exacerbated.

A new study led by Amedeo Minichino and published in the journal Bipolar Disorders, has found more evidence that people with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia may experience pain differently than the general population.

They studied 17 patients with bipolar I, 21 patients with bipolar II, 20 patients with schizophrenia and 19 healthy controls. The participants were stimulated with lasers to simulate a pinprick sensation. Pain perception was then measured according participant report of 0 equaling no pain and 10 equaling the worst possible pain. Pain processing was measured through electrodes on the scalp to determine the areas of the brain stimulated during the pinprick sensation.

Those with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia showed dysfunctions in areas of the brain typically associated with processing painful stimuli as well as the part of the brain linked to psychosis.

Participants with schizophrenia showed a higher pain tolerance and reduced sensitivity. Those with bipolar disorder also showed abnormalities in pain processing, especially a lower response in the AIC and ACC. Bipolar II participants showed closer results to the healthy controls.

The authors suggest this might be related to the psychosis spectrum. A bipolar II diagnosis indicates no experiences of psychosis, whereas almost 60% of people with bipolar I experience psychosis at some point.

A bipolar II diagnosis indicates no experiences of psychosis, whereas almost 60% of people with bipolar I experience psychosis at some point.

While this is an important step in understanding the way people with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder experience pain, there is much more research needed to fully understand the link.

You can follow me on Twitter @LaRaeRLaBouff or find me on Facebook.

Image credit:Xu-Gong

FEEDBACK:

By LaRae LaBouff on December 30, 2016

Read this next

Inside Bipolar Podcast: Does Hollywood Portray Life with Bipolar Accurately?

Discussing how bipolar disorder is portrayed in Hollywood and TV on this episode of Inside Mental Health podcast

READ MORE

Inside Bipolar Podcast: Owning Our Mistakes (Caused by Symptoms)

Bipolar disorder may not be our fault, but it is our responsibility.

Owning mistakes caused by bipolar symptoms on this podcast.

Owning mistakes caused by bipolar symptoms on this podcast. READ MORE

How Are Seasonal Patterns Related to Bipolar Disorder?

People with bipolar disorder may notice a change in seasons may trigger their symptoms. Learn more about seasonal bipolar disorder and how to cope.

READ MORE

Inside Bipolar Podcast: Managing Marriage and Bipolar

Keeping Love and Marriage Alive and Healthy When Living with Bipolar Disorder on this podcast episode. Listen Now!

READ MORE

Inside Bipolar Podcast: Is Happiness Possible with Bipolar?

Can you live with bipolar disorder and be happy at the same time? This podcast episode asks a serious question. Listen Now.

READ MORE

Inside Bipolar Podcast: Stopping Mania Before It Starts

Podcast episode discussing hints and tips on preventing and minimizing the damage bipolar mania can cause.

Listen Now!

Listen Now!READ MORE

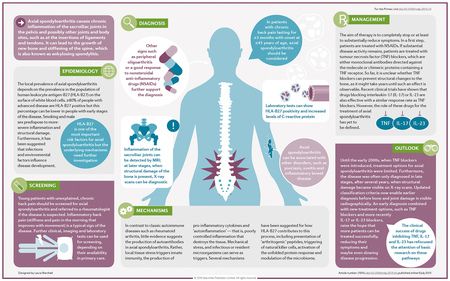

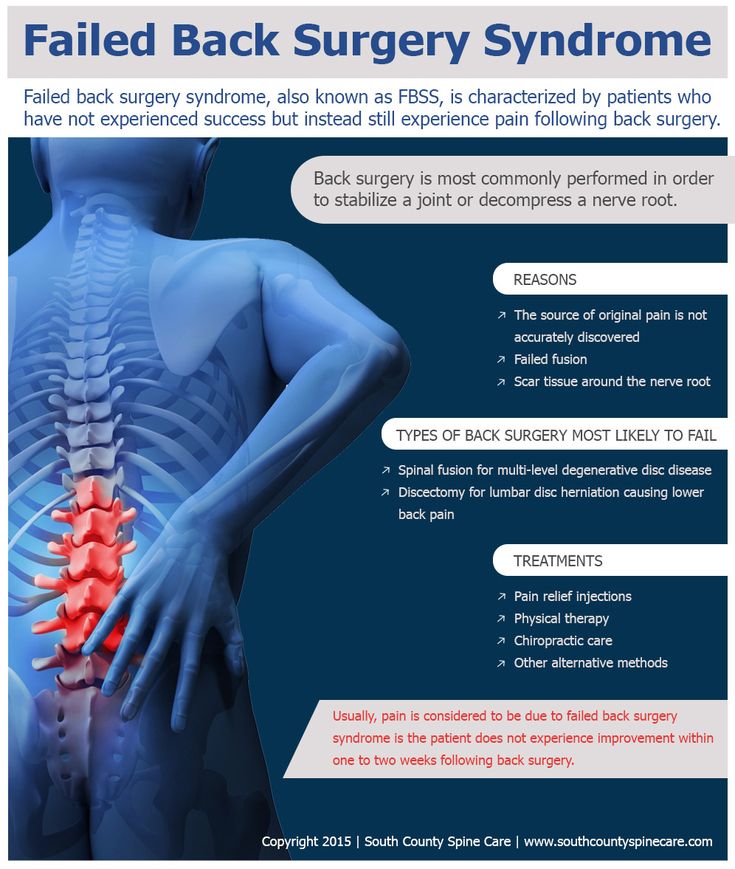

Chronic Pain and Bipolar Disorders: Diagnosis and Treatment

Bipolar and related disorders are distinct from depression, which was covered in the first installment of the A to Z Mental Health Series,¹ and are commonly found in patients who suffer from migraines and chronic pain. The 12-month prevalence of bipolar-I disorder across 11 countries ranged anywhere from 0.0% to 0.6%, with the United States having the highest prevalence (Table 1).²

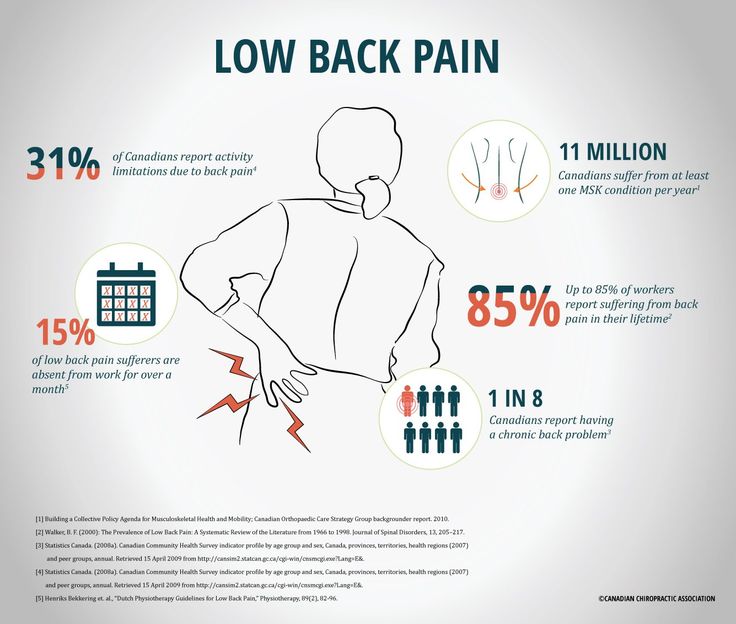

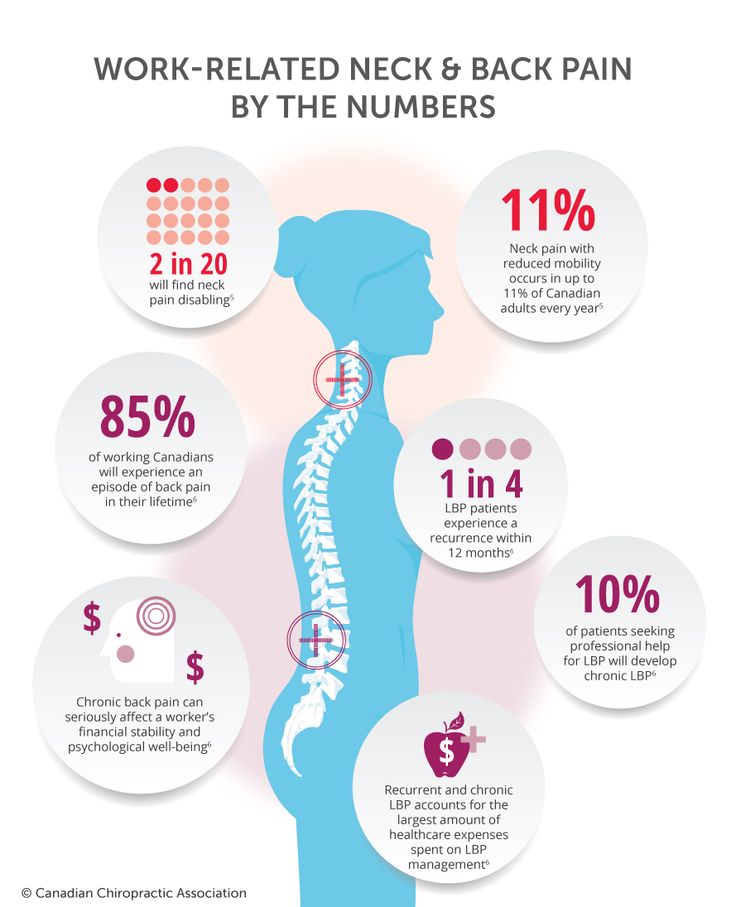

Individuals diagnosed with bipolar-I disorder have high rates of serious and often untreated comorbid medical conditions.³⁻⁵ According to a recent meta-analysis of people with bipolar disorder, the prevalence of clinical pain is approximately 29%; migraine is about 14%; and chronic pain is 24% (Table 2).⁶ In fact, individuals diagnosed with bipolar disorder report around 4 pain complaints at any given time.⁷ Musculoskeletal conditions, such as lower back pain, arthritis, and hip problems, have been found to be more prevalent among individuals with bipolar disorder than the general Department of Veteran Affairs patient population. 3 As noted, migraine is among the most common comorbid medical conditions diagnosed in individuals with bipolar disorder compared to the general population.8,9

3 As noted, migraine is among the most common comorbid medical conditions diagnosed in individuals with bipolar disorder compared to the general population.8,9

Migraines affect about 1 in 7 (14%) persons diagnosed with bipolar disorder, who are 3 times more likely to experience migraines compared to the general population.⁶ The risk of developing migraines is not the same among all types of bipolar disorders. A study by Low et al found that in the subgroup of patients with bipolar-II disorder, the lifetime prevalence of migraine was 65%.¹⁰ In the same study, the overall lifetime prevalence of migraine among all patients with bipolar disorder was 39.8% (43.8% among women and 31.4% among men).

Bipolar disorder and migraines are multifactorial in etiology—there appear to be vascular, cellular, molecular, neurochemical (serotonergic and noradrenergic), and genetic (KIAA0564) components in common between bipolar disorder and migraine conditions.¹¹

Individuals who suffer from pain and are diagnosed with a mental disorder, such as bipolar disorder, have been found to experience a worsening of psychiatric symptoms. ¹² In addition, health care professionals may at times fail to give complaints about physical health problems serious consideration among patients with serious mental illness.¹³ These patients are also less likely to recognize or monitor their comorbid medical conditions compared to the general population.¹⁴ In addition, they have an increased likelihood of experiencing conditions that cause pain, and a lower probability of receiving adequate care.¹⁵ For example, people diagnosed with bipolar disorder have an increased prevalence of depression, which has been linked to greater pain sensitivity.¹⁶ Chronic pain in persons diagnosed with bipolar disorder is associated with impaired recovery,¹⁷ greater functional incapacitation,¹¹ lower quality of life,⁷ and increased risk for suicide¹⁸ compared to individuals without pain.

¹² In addition, health care professionals may at times fail to give complaints about physical health problems serious consideration among patients with serious mental illness.¹³ These patients are also less likely to recognize or monitor their comorbid medical conditions compared to the general population.¹⁴ In addition, they have an increased likelihood of experiencing conditions that cause pain, and a lower probability of receiving adequate care.¹⁵ For example, people diagnosed with bipolar disorder have an increased prevalence of depression, which has been linked to greater pain sensitivity.¹⁶ Chronic pain in persons diagnosed with bipolar disorder is associated with impaired recovery,¹⁷ greater functional incapacitation,¹¹ lower quality of life,⁷ and increased risk for suicide¹⁸ compared to individuals without pain.

How Is Bipolar Disorder Defined?

In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), the bipolar and related disorders are broken into the following categories: bipolar-I disorder, bipolar-II disorder, cyclothymic disorder, substance/medication-induced, due to another medical condition, and “other specified category. ”¹⁹ The defining feature of bipolar-I disorder is the presence of at least 1 manic episode. Mania is defined by the DSM-5 as a distinct period of abnormally and persistently euphoric or irritable mood that lasts at least 1 week.¹⁹ Mood changes are accompanied by at least 3 of the following symptoms:

”¹⁹ The defining feature of bipolar-I disorder is the presence of at least 1 manic episode. Mania is defined by the DSM-5 as a distinct period of abnormally and persistently euphoric or irritable mood that lasts at least 1 week.¹⁹ Mood changes are accompanied by at least 3 of the following symptoms:

Being overly confident

Having racing thoughts

Being easily distractible

Being excessively involved in pleasurable activities resulting in negative consequences

Excessive talkativeness

Decreased need for sleep

Increase in goal-directed activity

The manic episode must result in marked impairment in social or occupational functioning, or require hospitalization to prevent harm to self or others (such as financial losses, illegal activities, loss of employment, and self-injurious behavior). It is necessary to meet criteria for a manic episode to make a diagnosis of bipolar-I disorder, but it is not required to have hypomanic (a mild form of mania marked by elation and hyperactivity) or major depressive episodes.

The other diagnoses under the bipolar and related disorders umbrella differ from the bipolar-I diagnosis. Bipolar-II disorder requires the presence of at least 1 episode of major depression and at least 1 hypomanic episode. Cyclothymic disorder is diagnosed when an individual experiences at least 2 years of both hypomanic and depressive periods without ever fulfilling the criteria for an episode of mania, hypomania, or major depression. The diagnosis of substance/medication-induced bipolar disorder is attributable to mania from the physiological effects of drug abuse (eg, cocaine or amphetamine intoxication), or the side effects of medications or treatments (eg, steroids, antidepressants, or stimulants). However, a manic episode that arises during treatment (eg, medications, electroconvulsive therapy, or light therapy) or drug use and persists beyond the physiological effect of the inducing agent is sufficient evidence for a manic episode, the defining feature of bipolar-I disorder diagnosis.

The other specified bipolar and related disorder category recognizes individuals, particularly children, who experience bipolar-like phenomena that do not meet the criteria for bipolar-I, bipolar-II, or cyclothymic disorders. However, if children exhibit recurrent silliness and “goofiness” beyond what is expected for their developmental level, have significant mood changes, attempt feats that are clearly dangerous and different from their normal behavior, and experience obvious and persistent increases in activity or energy levels, then a diagnosis of bipolar-I should be considered.

How Is the Diagnosis Different Now in the DSM-5?

In the DSM-5, the chapter on bipolar and related disorders was placed between the schizophrenia spectrum and depressive disorders to serve as a “bridge.” This bridge outlines how the new DSM-5 has moved away from a categorical to a dimensional approach. This decision was made due to its connection with psychosis and depression in terms of symptomatology, family history, and genetics. ² A few other details have been changed, including new mania criteria with an emphasis on changes in activity and energy, as well as mood. In addition, a new specifier—“with mixed features”—has been added that can be applied to episodes of mania or hypomania when depressive features are present, and to episodes of depression in the context of major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder when features of mania/hypomania are present. The DSM-5 also allows the specification of particular conditions for “other specified bipolar and related disorders.”

² A few other details have been changed, including new mania criteria with an emphasis on changes in activity and energy, as well as mood. In addition, a new specifier—“with mixed features”—has been added that can be applied to episodes of mania or hypomania when depressive features are present, and to episodes of depression in the context of major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder when features of mania/hypomania are present. The DSM-5 also allows the specification of particular conditions for “other specified bipolar and related disorders.”

How Do You Assess for Bipolar Disorder?

Due to informal or poor screening, the average time between onset of symptoms and formal diagnosis of bipolar disorder is greater than 7 years.²⁰ Several semi-structured interviews have been developed to assess bipolar disorder in adults. The 2 most commonly used measures are the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-4 (SCID) and the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS). The SCID and SADS both provide interview probes, symptom thresholds, and information about exclusion criteria (eg, medical or pharmacological conditions). The most reliable and valid way to obtain a diagnosis of bipolar disorder is through a structured interview with a trained mental health provider. However, several self-report measures have been developed to help identify persons most likely to meet criteria for bipolar disorders, such as the General Behavior Inventory and the Mood Disorder Questionnaire.²¹

The SCID and SADS both provide interview probes, symptom thresholds, and information about exclusion criteria (eg, medical or pharmacological conditions). The most reliable and valid way to obtain a diagnosis of bipolar disorder is through a structured interview with a trained mental health provider. However, several self-report measures have been developed to help identify persons most likely to meet criteria for bipolar disorders, such as the General Behavior Inventory and the Mood Disorder Questionnaire.²¹

What Does the Treatment of Bipolar Disorder Entail?

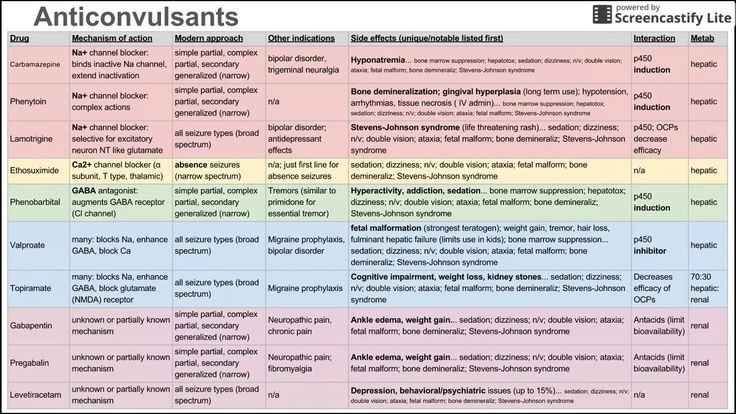

Individuals diagnosed with bipolar disorder who are treatment adherent report statistically lower levels of pain than their non-treatment-adherent counterparts.²² Given these symptom patterns, there is a need for treatments that can provide mood stabilization in addition to the treatment of pain. Medications are recommended as the first line of treatment for bipolar disorder by a psychiatric provider.²³

When treating more severe manic or mixed episodes, the initiation of either lithium plus an antipsychotic or valproate plus an antipsychotic is recommended. For less ill patients, monotherapy with lithium, valproate, or an antipsychotic may be sufficient. Monotherapy using an antidepressant is not recommended.

For less ill patients, monotherapy with lithium, valproate, or an antipsychotic may be sufficient. Monotherapy using an antidepressant is not recommended.

A better understanding of the association of bipolar disorder and chronic pain can help limit adverse pharmacological side effects. For example, a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) is often prescribed to treat chronic pain, but such medication (in the absence of a mood stabilizer) may trigger a manic episode in someone diagnosed with bipolar disorder.²⁴ There is also evidence that suggests that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may increase serum lithium levels, possibly eliciting lithium toxicity.²⁵ In addition, analgesics, such as opioids, may alter mood, increasing the risk of eliciting a manic episode.²⁶

Psychological treatment research has focused mostly on outcomes for mania and depression separately. There is strong research support for psychoeducation and systematic care, and modest support for cognitive therapy (CT) for the treatment of mania, but psychoeducation and CT only have modest support for depression (Table 3). ²⁷ Psychoeducation may be provided using the “Life Goals Program” manual²⁸ to teach patients about their symptoms and the need for medications, and to provide support in achieving occupational and social goals. Participants also create personal self-management plans detailing coping strategies for early warning signs of symptoms.

²⁷ Psychoeducation may be provided using the “Life Goals Program” manual²⁸ to teach patients about their symptoms and the need for medications, and to provide support in achieving occupational and social goals. Participants also create personal self-management plans detailing coping strategies for early warning signs of symptoms.

Systematic care consists of a system-level intervention and a group therapy component, perhaps CT. At the system level, care for bipolar patients is provided by an outpatient specialty team composed of a nurse care coordinator and a psychiatrist, with staff-patient ratios at a level that provides clients with regular appointments and easily available telephone consultations. According to the American Psychiatric Association, CT includes “a psychoeducational component regarding the biological basis of the illness, the need for medications, and the early warning signs of symptoms.” They also include “a focus on identifying maladaptive, negative thoughts about the self, and teaching patients skills to challenge these overly negative thoughts. ” Many manuals also include ideas about how to target the overly positive thoughts that might be present during mania.²⁹

” Many manuals also include ideas about how to target the overly positive thoughts that might be present during mania.²⁹

There is strong research support for family-focused therapy (FFT) and modest research support for interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (IPSRT) for bipolar disorder, but FFT and IPSRT do not have research support for mania.²⁷ FFT is a behavior-based intervention that includes psychoeducation, communication skills training, and problem-solving skills training. Families are taught to respond early to emergent symptoms, and they are provided with training about the best coping responses.³⁰ IPSRT builds upon the traditional focus of interpersonal psychotherapy by incorporating a behavioral self-monitoring program.³¹The intention is to help patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder to initiate and maintain a lifestyle characterized by more regular sleep-wake cycles, mealtimes, and other cues given by the environment. The ultimate goal is to help regulate circadian disturbances that may provoke or exaggerate episodes of mood disorder.

When the functional impairments of bipolar disorder are severe and persistent, other services may also be necessary, such as case management, assertive community treatment, psychosocial rehabilitation, and supported employment. These approaches, which have traditionally been studied in patients with schizophrenia, also show effectiveness for certain individuals diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Of course, we recommend physicians defer to a mental health professional for an accurate diagnosis and determination of appropriate treatment options.

In the next installment in the A to Z Mental Health Series, the author will discuss anxiety disorders and pain.

- Cosio D, Meshreki LM. Association between depressive disorder and chronic pain. Pract Pain Manag. 2017;17(1):19-22.

- Merikangas K, Jin R, He JP, et al. Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the world mental health survey initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(3):241-251.

- Kilbourne AM, Cornelius JR, Han X, et al.

Burden of general medical conditions among individuals with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6(5):368-373.

Burden of general medical conditions among individuals with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6(5):368-373. - Magalhães PV, Kapczinski F, Nierenberg AA , et al. Illness burden and medical comorbidity in the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125(4):303-308.

- Perron BE, Howard MO, Nienhuis JK, et al. Prevalence and burden of general medical conditions among adults with bipolar I disorder: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(10):1407-1415.

- Stubbs B, Eggermont L, Mitchell AJ, et al. The prevalence of pain in bipolar disorder: a systematic review and large-scale meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2015;131(2):

75-88. - Birgenheir DG, Ilgen MA, Bohnert AS, et al. Pain conditions among veterans with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(5):480-484.

- Jette N, Patten S, Williams J, Becker W, Wiebe S.

Comorbidity of migraine and psychiatric disorders—a national population-based study. Headache. 2008;48(4):501-516.

Comorbidity of migraine and psychiatric disorders—a national population-based study. Headache. 2008;48(4):501-516. - Ortiz A, Cervantes P, Zlotnik G, et al. Cross-prevalence of migraine and bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12(4):397-403.

- Low NC, Du Fort GG, Cervantes P. Prevalence, clinical correlates, and treatment of migraine in bipolar disorder. Headache. 2003;43(9):

940-949. - McIntyre R, Konarski JZ, Wilkins K, Bouffard B, Soczynska JK, Kennedy SH. The prevalence and impact of migraine headache in bipolar disorder: results from the Canadian community health survey. Headache. 2006;46(6): 973-982.

- Elman I, Zubieta JK, Borsook D. The missing p in psychiatric training: why it is important to teach pain to psychiatrists. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(1):12-20.

- Rethink Mental Illness. Lethal discrimination. September 2013. Available at: https://www.rethink.org/media/810988/Rethink%20Mental%20Illness%20-%20Lethal%20Discrimination.pdf. Accessed January 9, 2017.

- Kilbourne AM, McCarthy JF, Welsh D, Blow F. Recognition of co-occurring medical conditions among patients with serious mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194(8):598-602.

- De Hert M, Correll CU, Bobes J. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry. 2011;10(1):52-77.

- Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K. Depression and pain comorbidity: a literature review. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(20):2433-2445.

- Miller CJ, Abraham KM, Bajor LA, et al. Quality of life among patients with bipolar disorder in primary care versus community mental health settings. J Affect Disord. 2013;146(1):100-105.

- Ratcliffe GE, Enns MW, Belik SL, Sareen J. Chronic pain conditions and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: an epidemiologic perspective. Clin J Pain. 2008;24(3):204-210.

- American Psychiatric Association_. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders_.

5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. - Mantere O, Suominen K, Leppämäki S, Valtonen H, Arvilommi P, Isometsä E. The clinical characteristics of DSM-IV bipolar I and II disorders: baseline findings from the Jorvi Bipolar Study. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6(5):395-405.

- Miller CJ, Johnson SL, Eisner L. Assessment tools for adult bipolar disorder. Clin Psychol (New York). 2009;16(2):188-201.

- Fornaro M, De Berardis D, Iasevoli F, et al. Treatment adherence towards prescribed medications in bipolar-II acute depressed patients: relationship with cyclothymic temperament and “therapeutic sensation seeking” in response towards subjective intolerance to pain. J Affect Disord. 2013;151(2):596-604.

- Bowden CL, Hirschfield RMA, Keck PE, et al. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2010. Available at: https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/bipolar.

pdf. Accessed January 20, 2017.

pdf. Accessed January 20, 2017. - Pacchiarotti I, Bond DJ, Baldessarini RJ, et al. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) task force report on antidepressant use in bipolar disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(11):1249-1262.

- Ragheb M. The clinical significance of lithium-nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug interactions. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1990;10(5):350-354.

- Martins SS, Keyes KM, Storr CL, Zhu H, Chilcoat HD. Pathways between nonmedical opioid use/dependence and psychiatric disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;103(1-2):16–24.

- Johnson SL, Fulford D. Bipolar disorder. American Psychological Association Society of Clinical Psychology. 2017. Available at: https://www.div12.org/psychological-treatments/treatments/disorders/bipolar-disorder/. Accessed December 1, 2016.

- Sajatovic M, Davies MA, Ganocy S, et al. A comparison of the life goals program and treatment as usual for individuals with bipolar disorder.

Psychiatric Serv. 2009;60(9):1182-1189.

Psychiatric Serv. 2009;60(9):1182-1189. - Ball JR, Mitchell PB, Corry JC, Skillecorn A, Smith M, Malhi GS. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive therapy for bipolar disorder: focus on long-term change. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(2):277-286.

- Miklowitz DJ, Simoneau TL, George EL, et al. Family-focused treatment of bipolar disorder: 1-year effects of a psychoeducational program in conjunction with pharmacotherapy. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(6):582-592.

- Frank E, Swartz HA, Kupfer DJ. Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy: managing the chaos of bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(6):593-604.

Notes: This article was originally published March 13, 2017 and most recently updated June 15, 2017.

How to get rid of chronic pain?

Some people experience pain all the time, literally live with it, and there is no physiological explanation for this. They go to doctors, take a bunch of tests, but do not find any obvious reasons for their condition. However, this does not mean at all that they invent everything or want the attention of doctors. Such people do feel pain, it's just that this pain is psychosomatic, its causes do not lie in physical injuries or inflammatory processes. People with such pain find it very difficult to live, they feel despair and hopelessness and often become depressed. In most of these cases, all you need to do is trust the therapist and learn how to work with your own feelings correctly.

However, this does not mean at all that they invent everything or want the attention of doctors. Such people do feel pain, it's just that this pain is psychosomatic, its causes do not lie in physical injuries or inflammatory processes. People with such pain find it very difficult to live, they feel despair and hopelessness and often become depressed. In most of these cases, all you need to do is trust the therapist and learn how to work with your own feelings correctly.

How does chronic pain appear?

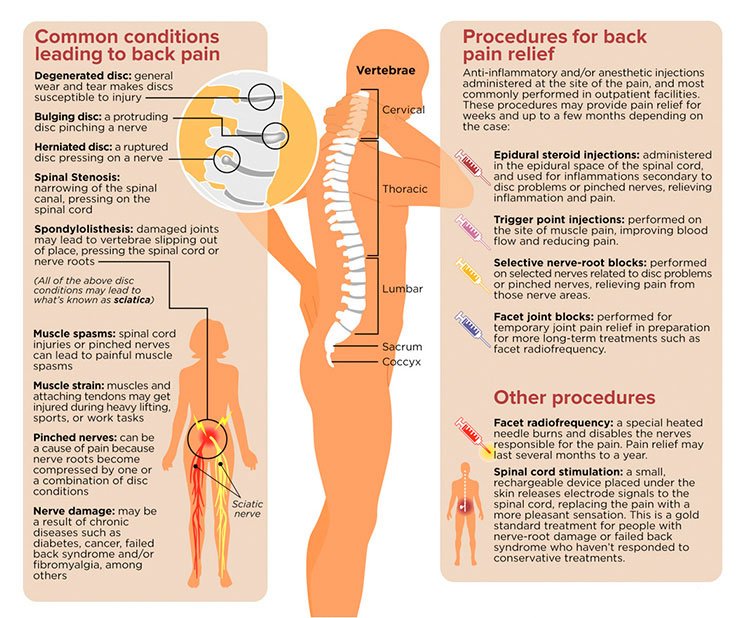

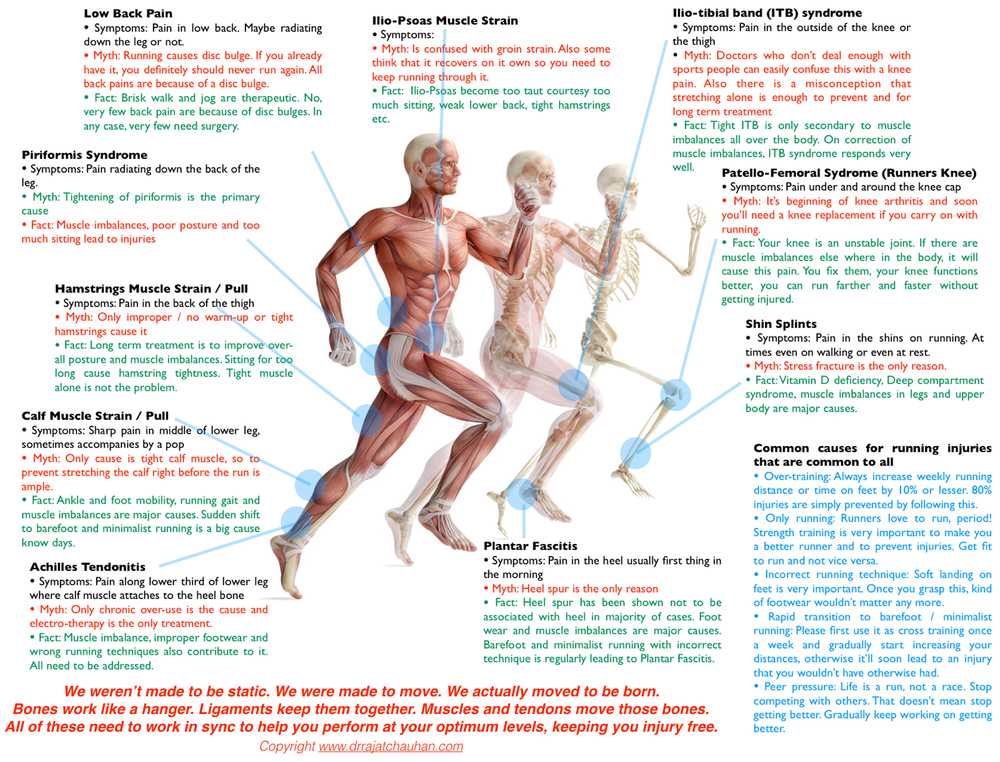

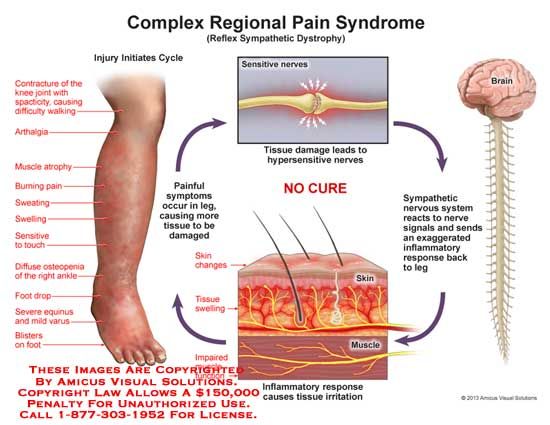

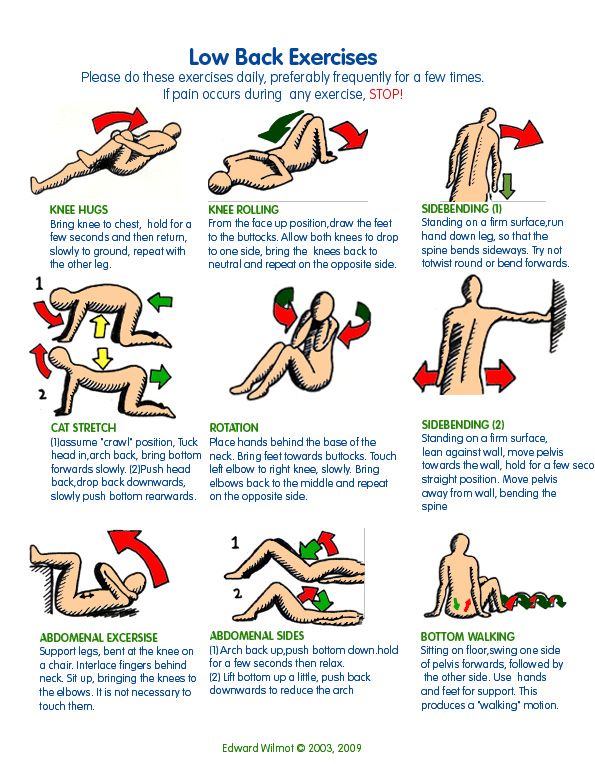

Pain can vary. For example, it may have a clear physiological cause: some kind of injury, fracture, or inflammation. But there are chronic pains that have no obvious cause. People with such pain are constantly being tested, they turn to different doctors, but they do not find any source of pain. The fact that a person is definitely in pain can be shown by such instrumental checks as functional magnetic resonance imaging or EEG - when you can see the activity of parts of the brain and nervous system during pain. Chronic pain can be felt by a person as pain in any part of the body, such as in the leg or arm, but usually such pain is expressed in the form of migraines and pain in the lower back, knees and back. And it happens that the whole body hurts completely, such a disease is called “fibromyalgia”.

Chronic pain can be felt by a person as pain in any part of the body, such as in the leg or arm, but usually such pain is expressed in the form of migraines and pain in the lower back, knees and back. And it happens that the whole body hurts completely, such a disease is called “fibromyalgia”.

Suffering for a long time from pain, a person begins to experience despair.

Chronic pain for which there is no physiological explanation usually appears suddenly. It can begin almost imperceptibly, and then gradually intensify, or it happens that acute pain immediately comes. As a general rule, to become chronic, the pain must return regularly or be felt continuously for a long time. Suffering for a long time from pain, a person begins to experience despair. First, he tries to find out the reason, and turns to a variety of doctors, but the doctors can not find anything. The person feels irritated and indignant that no one can help him. Moreover, with each new unsuccessful test, they try to convey to him that he has problems with his head, and they advise him to consult a psychiatrist. As a result, when such a patient realizes that no one can help him, he waves his hand at everything and still goes to the psychiatrist in the hope that he will explain everything to him exactly. Most often, he does not find help there either, since not all psychiatrists know that a patient with a similar problem should be referred to psychotherapy.

As a result, when such a patient realizes that no one can help him, he waves his hand at everything and still goes to the psychiatrist in the hope that he will explain everything to him exactly. Most often, he does not find help there either, since not all psychiatrists know that a patient with a similar problem should be referred to psychotherapy.

See also

Painful emotions

How do people with chronic pain live?

When a person experiences pain for a long time, it affects his behavior and life. Pain causes him to become more withdrawn and unsociable, to narrow his living space. Such people function less and less in society, work less often or even quit their jobs and apply for disability. They stop seeing friends, playing sports, eating into their depression. These people experience depression in their own way. This is not clinical depression, which is genetically inherent in a person - it is associated precisely with pain. Pain goes away and depression ends. Because people with chronic pain often eat away at their condition, many of them become obese.

Pain goes away and depression ends. Because people with chronic pain often eat away at their condition, many of them become obese.

How to cure chronic pain with psychotherapy?

If a person with chronic pain does decide to see a psychotherapist, it takes a long time for the specialist to overcome the barrier of mistrust. Indeed, most often the patient remains convinced for a long time that the pain has a physiological cause that simply no one can detect. And of course, first of all, the psychotherapist makes sure that all the necessary physiological checks have already been passed. Only when it becomes absolutely clear that the pain has no physiological cause, the therapist begins treatment.

If the psychotherapist understands that the patient's pain is due to psychosomatics, he tries to identify what could be the original psychological trigger.

First of all, the specialist finds out when the patient began to feel pain, after which it appeared. He learns how during this period the patient developed relationships with loved ones, what was the situation at work. If the psychotherapist understands that the patient's pain is due to psychosomatics, he tries to identify what could be the original psychological trigger. As a rule, in the course of therapy, a traumatic memory, a disturbing event, or a psychological trauma that provoked the onset of pain is identified. Such a cause may be a conflict at work, some kind of stressful situation in the family.

He learns how during this period the patient developed relationships with loved ones, what was the situation at work. If the psychotherapist understands that the patient's pain is due to psychosomatics, he tries to identify what could be the original psychological trigger. As a rule, in the course of therapy, a traumatic memory, a disturbing event, or a psychological trauma that provoked the onset of pain is identified. Such a cause may be a conflict at work, some kind of stressful situation in the family.

See also

First aid for anxiety attacks

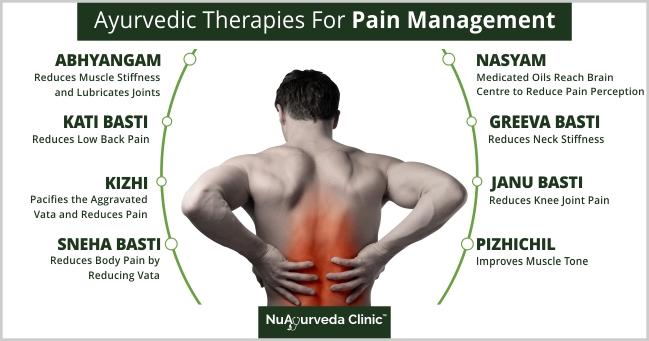

When the cause is identified, the psychotherapist tries to remove the acute pain with the help of psychological methods. In fact, it becomes easier for a person when he begins to trust the psychotherapist and independently gets involved in the work, fulfills all the recommendations. This gives the patient strength, adds self-confidence and influences the physiological correlates of pain. One of the most effective methods of dealing with such pain is meditation. It teaches a person to retreat from pain in time, look at it from the outside and relax. The patient begins to understand how to notice the pain before it starts and how not to let it get worse.

One of the most effective methods of dealing with such pain is meditation. It teaches a person to retreat from pain in time, look at it from the outside and relax. The patient begins to understand how to notice the pain before it starts and how not to let it get worse.

Typically, the process of treating chronic pain with a psychotherapist takes from 2 sessions to 3-4 months, depending on the specific problem. It does not depend so much on the nature of the pain and its cause, but on the person himself, on his involvement in the treatment process. If he is ready to follow all the recommendations and advice of a specialist, just a few meetings may be enough for treatment. The pain goes away, becoming weaker and appearing less and less. However, the most important work happens after a person has learned to interact with his pain - for the rest of his life he needs to ensure that the pain does not return. After all, there are many disturbing moments in life that can start the mechanism of pain again.

- Depression

Share:

Chronic back pain treatment with manual therapy in Moscow

Are you worried about constant back pain?

In developed countries, chronic back pain is very common, according to leading medical sources, its frequency varies from 15% to 45% of the total number of back pain visits. Back pain is the leading disease in terms of days lost from work among the working population, and the associated medical costs are truly enormous. Yet the causes of chronic back pain are often misunderstood. People who suffer from monotonous, nagging back pain, constantly or occasionally, become desperate when they cannot determine its cause.

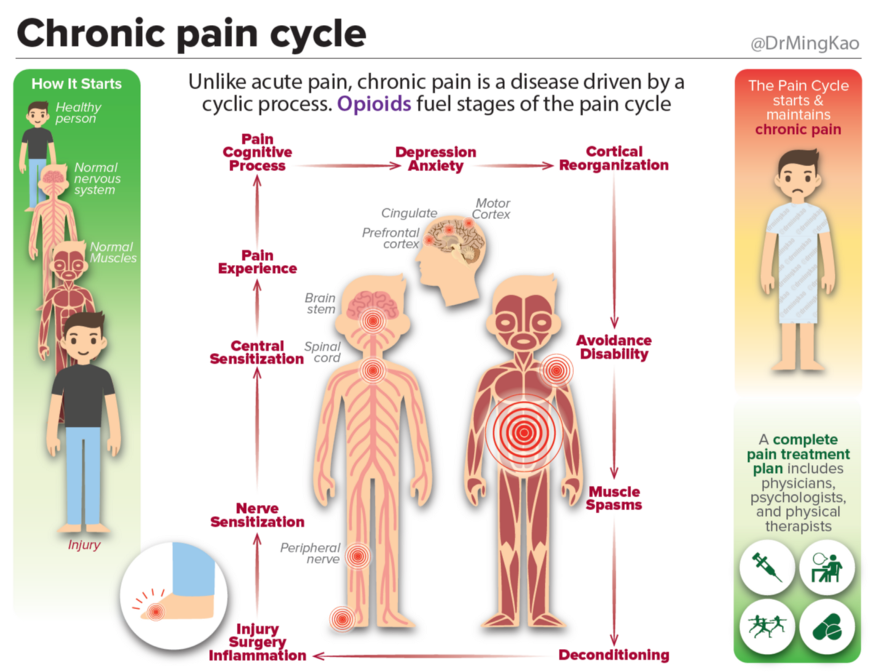

How is chronic pain different from acute pain?

From a neurophysiological point of view, these are two fundamentally different states. If acute pain is our helper and savior, i. e., it is a danger signal to which the body reacts in one way or another (for example, pulling a hand when touching a hot object) for self-preservation, which is a normal physiological reaction to an accomplished or potential tissue damage , then with chronic pain, not everything is as simple as it seems at first glance. With a long course, the pain loses its physiological function and becomes an independent disease. It already brings suffering in itself - the tissue heals, the damage is eliminated, and the pain continues.

e., it is a danger signal to which the body reacts in one way or another (for example, pulling a hand when touching a hot object) for self-preservation, which is a normal physiological reaction to an accomplished or potential tissue damage , then with chronic pain, not everything is as simple as it seems at first glance. With a long course, the pain loses its physiological function and becomes an independent disease. It already brings suffering in itself - the tissue heals, the damage is eliminated, and the pain continues.

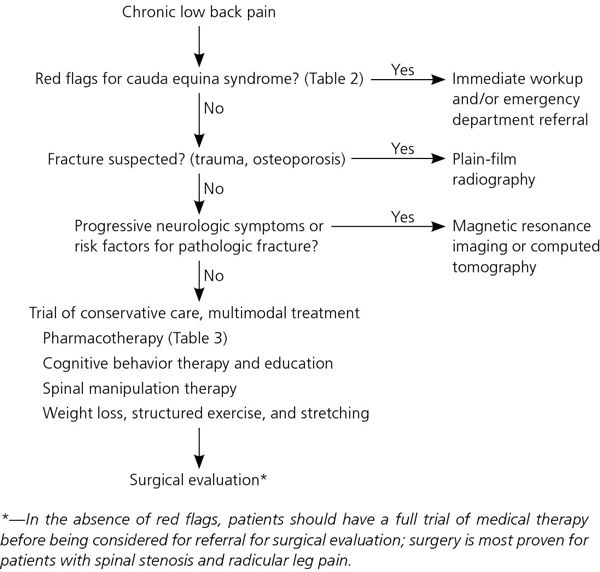

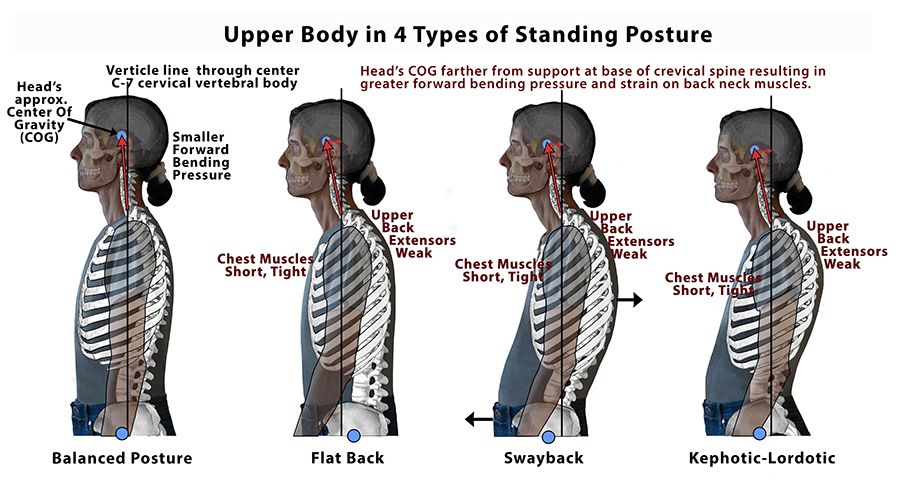

Pain in its development goes through several stages, starting from its origin from the primary focus - the place of injury (acute pain), if the cause of acute pain is not treated, then pain receptors continue to be irritated and send continuous impulses to the central nervous system (spinal cord and brain), over time, from continuous incoming information, the cells responsible for conducting and analyzing these impulses in the brain become hyperexcitable and undergo restructuring, a secondary focus of pathological impulses is formed and a change in the psycho-emotional perception of pain (subacute and chronic pain).

Acute pain is a signal of danger, chronic pain is a disease!

The cause of chronic back pain is pain that was not treated in the acute period!

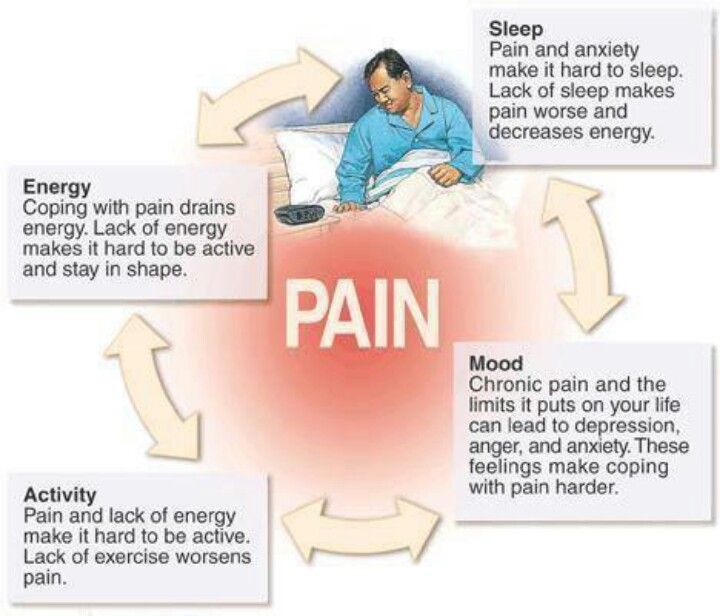

With the development of chronic back pain, from now on, the main role in its maintenance will be played not only by the primary focus of damage, but also by a change in its perception in the psycho-emotional sphere.

Companions of chronic pain:

- depression;

- decreased concentration;

- high fatigue;

- sleep disturbance;

- disability;

- decreased self-esteem;

- feeling of hopelessness.

At the same time, the rule also works in the opposite direction, i.e. people who experience prolonged stress, depression and insomnia, as independent diseases, are prone to the development of chronic pain.

Since depression and chronic pain are mutually supportive pathological processes, a vicious circle is formed. A strong link is formed between pain and depression, which is also strengthened by the phenomena of muscle spasms.

Muscle spasms occur against the background of stress in people leading a sedentary lifestyle. They cause pain that can trigger or exacerbate an existing chronic pain syndrome.

How do you know if you have chronic pain?

As mentioned above, chronic pain is a disease.

From the point of view of practical medicine, chronic pain is pain that bothers the patient for more than 12 weeks (3 months). If everyone can determine the duration of pain on their own, then it is almost impossible to assess their psycho-emotional state, especially when it comes to the subclinical course of depression.

Is treatment effective for chronic back pain?

Currently, there are many methods of treatment for patients with chronic back pain, some of them are more effective than others. Many patients who experience constant back pain have gone through more than one specialist who attributed everything to osteochondrosis of one or another part of the spine as the cause of all back pain, and received treatment that, at best, brought little improvement.

You can't delay - you need to be treated!

Many patients are trying to find information on how to cope with their illness on their own. And today, on the Internet, a large number of "advisers" have appeared who provide various kinds of recommendations. Often such recommendations are not only unable to help in solving the problem, but can also do harm. Most patients do not have sufficient knowledge to make a diagnosis and choose an adequate treatment. Each patient is unique, has his own medical history, his own anatomical features, and therefore requires an individual approach to the treatment of his disease, which will be determined by the doctor during a personal meeting with the patient. Previous self-treatment, in some cases, complicates the work of the doctor and may increase the time to achieve the desired effect of the treatment. Chronic pain has complex mechanisms already within the nervous system, they are pathological. Our task is to identify and have an effective impact on them.