Victim of abuse becomes the abuser

Why Do People Abuse | The National Domestic Violence Hotline

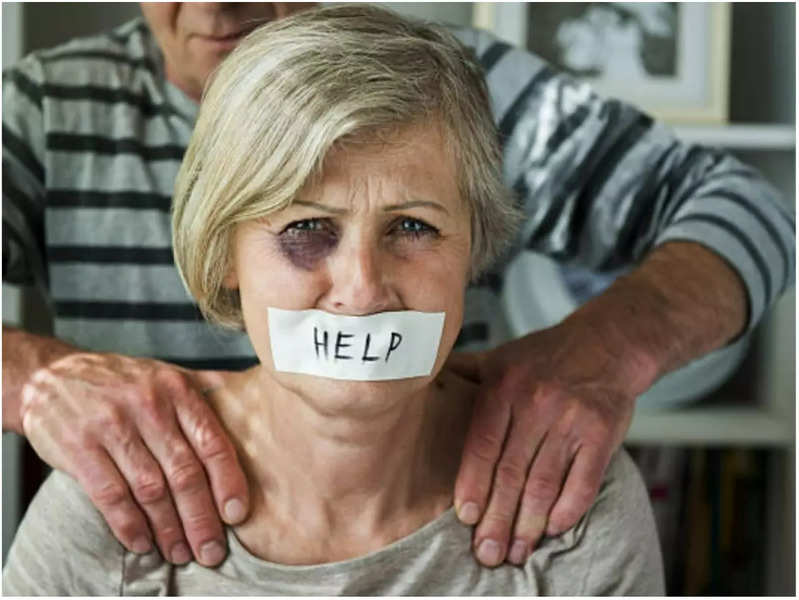

Domestic violence stems from a desire to gain and maintain power and control over an intimate partner. Abusive people believe they have the right to control and restrict their partner’s lives, often either because they believe their own feelings and needs should be the priority in the relationship, or because they enjoy exerting the power that such abuse gives them.

Tactics of abuse (in any form) may be aimed at dismantling equality in the relationship in order to make their partners feel less valuable and undeserving of respect.

Remember that everyone deserves to have a healthy, loving, and respectful relationship—no matter what.

Abuse is a learned behavior. Some people witness it in their own families growing up; others learn it slowly from friends, popular culture, or structural inequities throughout our society. No matter where they develop such behaviors, those who commit abusive acts make a choice in doing so — they also could choose not to.

There are many people who experience or witness abuse who use their experiences to end the cycle of violence and heal themselves without harming others. While outside factors (including drug or alcohol addiction) can escalate abuse, it’s important to recognize that these issues do not cause domestic abuse themselves.

Who does abuse affect?

Anyone can be abusive and anyone can be the victim of abuse. Abuse happens regardless of gender, age, sexuality, race, economic status, ability, citizenship status, or any other factor or identity. Feelings of confusion, fear, or anger are normal responses to abuse, but they may also make you feel isolated or like no one will understand. Remember that expert advocates from The Hotline are available 24/7 to talk through your situation and help you build a safety plan tailored to your circumstances.

Being abusive is a decision: it’s a strategic behavior by your partner to create their desired power dynamic.

Regardless of the circumstances of your relationship or past, no one ever deserves to be abused and you’re never responsible for your partner’s abusive actions.

Domestic violence can also strain the people who witness, intervene, or simply recognize the tragic realities of relationship abuse. It can be painful and draining — physically, mentally, emotionally, and financially — to watch the people in our lives abuse or be abused. In that regard, we are all impacted by any and all forms of abuse, and it’s on each of us to take steps in our daily interactions to end and prevent future abusive behavior.

a quote mark iconBeyond the physical risks of leaving an abusive relationship, there are countless other reasons why people stay in their relationships. Survivors deserve to be supported in their decision-making and empowered to reclaim control over their own lives—no matter the circumstances.

Why Do Some Victims of Abuse Become Abusers Themselves — And Others Don't?

Fatima, an 18-year-old Torontonian who works in a library, can do little to please her controlling mother and brother. “They both set very high standards for what kind of a person they want me to be, and when I don’t meet those standards, they yell at me — a lot,” she says. “A week never goes by without them going into a fit like this. Sometimes, they’ll gang up and yell at me together.” Transgressions as minor as being five minutes late to meet them or ducking out of the house for 20 minutes without permission result in verbal abuse, name-calling, gaslighting and slut-shaming. “They’ll yell at me about how they wish I was dead,” she continues. “Have you ever heard that voicemail that Alec Baldwin left for his daughter? It’s just like that.”

“They both set very high standards for what kind of a person they want me to be, and when I don’t meet those standards, they yell at me — a lot,” she says. “A week never goes by without them going into a fit like this. Sometimes, they’ll gang up and yell at me together.” Transgressions as minor as being five minutes late to meet them or ducking out of the house for 20 minutes without permission result in verbal abuse, name-calling, gaslighting and slut-shaming. “They’ll yell at me about how they wish I was dead,” she continues. “Have you ever heard that voicemail that Alec Baldwin left for his daughter? It’s just like that.”

Fatima’s father passed away before she was born, and she used to fantasize that he was a more gentle soul than the rest of her family, and that if he’d been alive for her upbringing, she’d be a happier person. It was heartbreaking, then, for her to learn that he was physically and emotionally abusive to Fatima’s mother and brother — perhaps even the source of some of their abusive habits. “They don’t go into detail about it often, but I know for a fact that he would hit them both a lot,” she explains. “It definitely makes me understand why they are this way.” (Fatima’s name, as well as the other victims quoted in this story, have been changed for privacy and safety.)

“They don’t go into detail about it often, but I know for a fact that he would hit them both a lot,” she explains. “It definitely makes me understand why they are this way.” (Fatima’s name, as well as the other victims quoted in this story, have been changed for privacy and safety.)

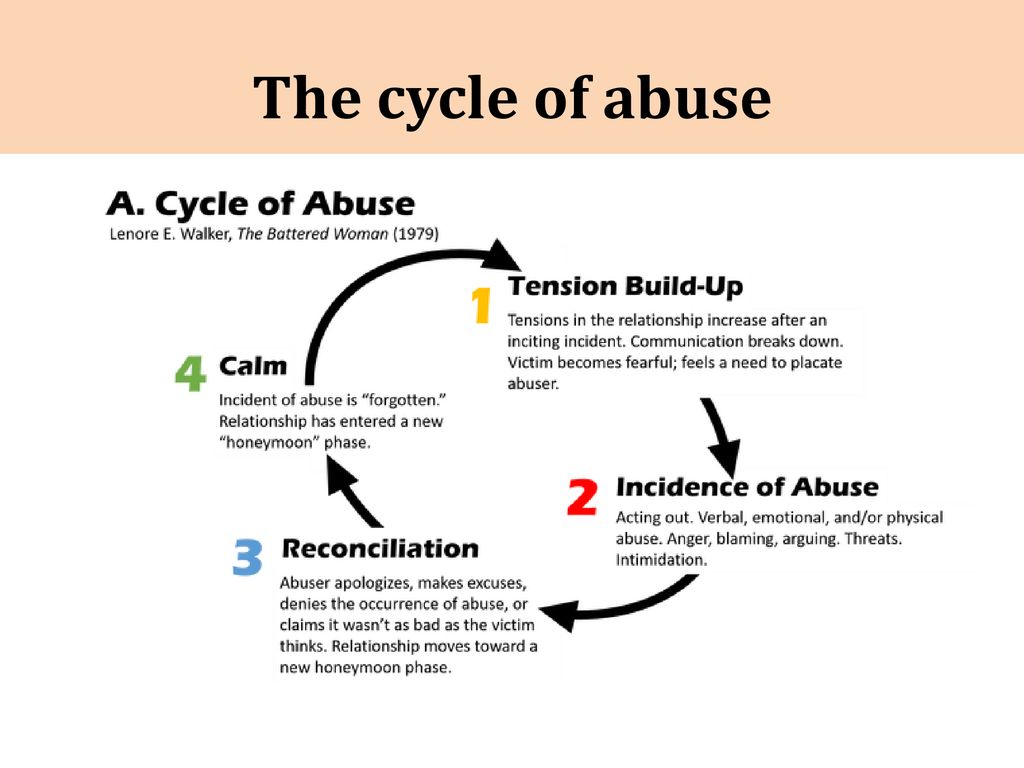

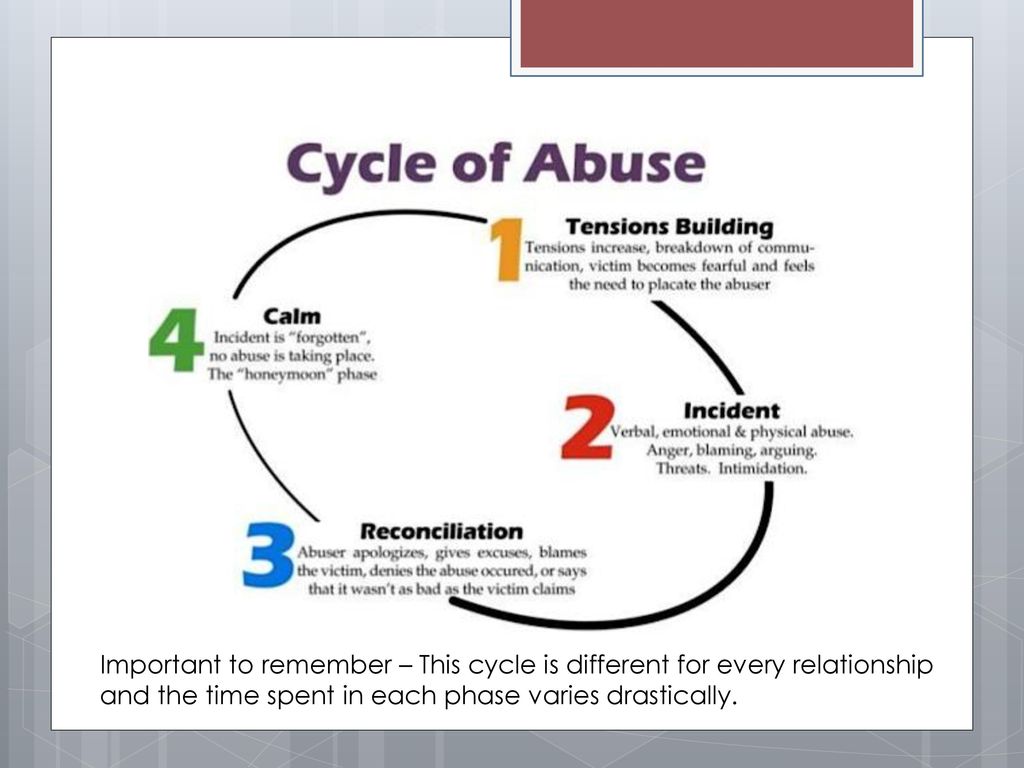

Among the difficulties of understanding abuse is that the bright line we sometimes imagine between victim and abuser is illusory. People who abuse others are often victims of abuse themselves — whether at the hands of their parents, other relatives, strangers or previous lovers — and they can repeat the patterns of abuse they were subjected to, or create new ones, in their relationships with others. A great tragedy then is that abuse can become a cycle, and the burden of breaking it necessarily falls on victims.

Not all victims of abuse will go on to abuse others, but studies suggest that about one-third of them will. Certain factors have been found to worsen the long-term impact of abuse and make it more difficult to break the chain, including abuse that started early in life, abuse that lasted a long time, abuse in which the perpetrator had a close relationship to the victim, abuse that the child experienced as particularly harmful and abuse that occurred within a cold familial environment. Victims of abuse who do go on to become abusive themselves may not always repeat the exact nature of their own abuse, either — a person who was sexually abused as a child may not go on to sexually abuse her own children, for example, but may be a neglectful parent.

Victims of abuse who do go on to become abusive themselves may not always repeat the exact nature of their own abuse, either — a person who was sexually abused as a child may not go on to sexually abuse her own children, for example, but may be a neglectful parent.

Olivia, a 27-year-old tech worker in the Bay Area, is very conscious of the need to break the cycle of abuse in her own life. Her father was neglectful, physically intimidating and explosively angry, and she’s aware that her father’s parents were similarly behaved, so she worries about this behavior continuing down the line. “My dad used to say, ‘It’s not a family holiday until someone cries,’ and there was almost a degree of pride to it,” she explains. “Or at least, since that was how things were growing up for him, it’s okay that his daughters or wife were driven to tears.” She worries that she might have the same blind spot her father does. “My dad would never have thought of himself as abusive,” she explains. “Now, I didn’t think of myself as an abuser in any of my relationships, but who was I to judge? I thought my home life was normal until high school. ”

”

This sense that abusive behavior is “normal” is one of the key reasons it can be continued by victims. “If love has been coinciding with abuse as long as you can remember, you may not even realize that what you’re seeing is abusive behavior,” says Elise Franklin, a psychotherapist based in L.A. “Someone that is used to being told, ‘You’re worthless,’ may feel strangely at home with that messaging from others, and also pass on that messaging, too. We’re creatures of patterns and habits, and if we’re not mindful, we can re-enact these over and over unconsciously.”

Franklin says that a lot of victims who have carried on the pattern of abuse in their own lives have no idea that their own experiences constituted abuse. “So many times I’ve asked patients about abuse, and gotten a firm, ‘Nope, never been through that,’ only to discover that they wouldn’t call it that but were absolutely abused,” she continues. “A lot of the time people don’t think of the behavior as abuse because they think they deserved it.”

“So many times I’ve asked patients about abuse, and gotten a firm, ‘Nope, never been through that,’ only to discover that they wouldn’t call it that but were absolutely abused,” she continues. “A lot of the time people don’t think of the behavior as abuse because they think they deserved it.”

For a patient like this, being beaten up because they threw a tantrum feels like a proportionate, deserved and normal punishment. “It’s only when someone teaches them that actually there are other responses to a tantrum,” she continues, “and that it doesn’t mean you’re ‘bad,’ that people can see a different way of behaving when they grow up.”

The feeling of abuse being justified or deserved is a crucial predictive factor in terms of whether the victim will go on to abuse others. “What seems to be a major factor in those that end the cycle of abuse is having had someone external, or something inside of them, that let them know that the abuse wasn’t their fault,” Franklin explains. “This is why therapy can be so helpful for people who have experienced abuse. ” Here, the role of people outside the immediate family can be crucial. If a child is being abused by her parents but has one teacher, neighbor, friend or cousin who can provide the perspective that the abuse isn’t normal or deserved, that can make an enormous difference to her emotional resilience and future outcomes.

” Here, the role of people outside the immediate family can be crucial. If a child is being abused by her parents but has one teacher, neighbor, friend or cousin who can provide the perspective that the abuse isn’t normal or deserved, that can make an enormous difference to her emotional resilience and future outcomes.

Emily, a 28-year-old paralegal in Chicago, has witnessed the different life outcomes of a victim who is able to get help and move on, and one who is perpetually stuck in the victimhood mode, becoming abusive as a result. “I was raised by my mom and her now-ex wife, J, both of whom were children of alcoholic mothers,” Emily explains. “My mom was able to heal and work through her own trauma healthily [she’s been in therapy and attended Al-Anon groups since the 1980s], while my stepmom was very much not able to do so and ended up emotionally abusing all of us from the time I was eight until I was 23.”

Without her mother’s positive example and a therapist who was willing to label J’s behavior as “abusive,” Emily isn’t sure she wouldn’t have become like her stepmother. “I internalized a lot of what J would say to me and how she treated me over the years,” Emily continues. “I’m still trying to unlearn some things, because I know that if I don’t do the work, I’ll inevitably repeat the patterns she taught us.”

“I internalized a lot of what J would say to me and how she treated me over the years,” Emily continues. “I’m still trying to unlearn some things, because I know that if I don’t do the work, I’ll inevitably repeat the patterns she taught us.”

Researchers in this area repeatedly stress that the relationship between victim and abuser isn’t a deterministic one — i.e., just because you were abused as a child, doesn’t mean that you’re fated to become an abuser yourself. “The vast majority of people who experience child sexual abuse won’t go on to offend,” says Allyn Walker, an assistant professor of sociology and criminal justice at Old Dominion University who studies people who are sexually attracted to children but who have never committed a sexual offense.

The numbers back them up: If around one-third of victims go on to become abusers, that means that the vast majority are able to break the cycle of abuse. “That’s a really important finding,” Cathy Spatz Widom, who researches the link between victimhood and abuse, told the National Institutes of Health. “It has this important message that, if you have a history, you shouldn’t necessarily feel that you’re bound to continue in this cycle of maltreatment.”

“It has this important message that, if you have a history, you shouldn’t necessarily feel that you’re bound to continue in this cycle of maltreatment.”

Walker cautions that believing otherwise can be very stigmatizing. “We already know that there’s huge stigma out there in terms of victims coming forward about experiencing abuse — there’s the potential that they won’t be believed, that the abuse will be downplayed and that they’ll be told they misled their abuser — all of which discourages a victim from disclosing the abuse to others,” Walker says. “Adding in this idea of ‘victims will become future offenders’ is just one more incorrect assertion that can keep them silent.”

Not to mention, victimhood is only a single predictive factor in terms of future offending. In his book, Pedophilia and Sexual Offending Against Children: Theory, Assessment and Intervention, researcher Michael Seto reports that, besides having also been sexually abused as a child, other predictive factors of offending include neurological deficits, antisociality, drug or alcohol abuse and impulsivity. “One study found that the strongest predictor from childhood of becoming an abusive parent was not having been abused, but rather having felt as a child that one was unloved and unwanted by one’s parents,” reports Daniel Goleman in the New York Times. “[This is] an attitude common, of course, among abused children, but also found in families in which there is no overt abuse.”

“One study found that the strongest predictor from childhood of becoming an abusive parent was not having been abused, but rather having felt as a child that one was unloved and unwanted by one’s parents,” reports Daniel Goleman in the New York Times. “[This is] an attitude common, of course, among abused children, but also found in families in which there is no overt abuse.”

Olivia’s father saw himself as a victim, and used his children to bolster his aggrieved sense of self. “He thinks of himself as an underdog who was beaten down on,” she explains. “We were alternatively completely ignored or rounded up to appreciate some movie or activity he liked, and sometimes we’d have to play audience to him telling us for hours about everything the world, government and his evil ex-wife (i.e., our beloved mother) was doing wrong to him.” But when her father would stomp around yelling at Olivia and her sister or punch the car roof repeatedly, he considered that justified behavior — not the behavior of a bully. “He sincerely believed the things he said when he was angry didn’t count, and didn’t need to be apologized for,” she adds.

“He sincerely believed the things he said when he was angry didn’t count, and didn’t need to be apologized for,” she adds.

Victims of abuse who have become abusive themselves are usually completely unaware that they’ve switched roles, so deeply do they see themselves as victimized, disempowered, small, abandoned and unloved. They essentially still see themselves as child-victims, and this can result in them neglecting or lashing out at their actual children. “Being abused is incredibly disempowering, so someone who has experienced that as a child might grow up trying to overcome that feeling of disempowerment, which can sometimes turn into them ‘conquering’ others,” Franklin explains. “Essentially, old, repressed anger gets turned into a kind of revenge which they take out on others — it’s an unconscious message that ‘I’m big and no one will hurt me again, and to make sure of that I’ll hurt others first,’ even if it’s their own children or partners.”

When it comes to breaking the cycle of abuse, personal responsibility is a crucial concept. In its groundbreaking therapeutic model for preventing sexual abuse among people who are sexually attracted to children, the German Prevention Network “Kein Täter werden” (meaning, “Don’t Offend”) lists “taking responsibility for one’s own behavior” as among the key therapeutic focal points identified in research as “decisive” for preventing abuse. In other words, the child-victim must recognize that he is now an adult who holds power over others, and take responsibility for the ways in which he exercises that power.

In its groundbreaking therapeutic model for preventing sexual abuse among people who are sexually attracted to children, the German Prevention Network “Kein Täter werden” (meaning, “Don’t Offend”) lists “taking responsibility for one’s own behavior” as among the key therapeutic focal points identified in research as “decisive” for preventing abuse. In other words, the child-victim must recognize that he is now an adult who holds power over others, and take responsibility for the ways in which he exercises that power.

Being abused by a person who was once, or is also, a victim can cause mixed feelings for the present victim. “At first I was very sympathetic toward her, since she’d often talk about the things she went through,” Emily says of her stepmother. “But the moment the sympathy turned to anger was when I realized she was still not growing or learning.”

“But the moment the sympathy turned to anger was when I realized she was still not growing or learning.”

Fatima says the fact that her mother and brother were abused by her father helps her to see why they’re so unrelenting in their criticism and yell so often, but it’s not much of a consolation day-to-day. “It definitely makes me understand why they are this way, but I can’t forgive them until they say sorry, which they never have,” she explains. “I’m angry at them for making me grow up so quickly and for ruining my childhood.”

If anything, Fatima thinks that their own abuse should have made them more empathetic and resolved not to continue the cycle, in the same way that it did for her. “It’s because of my mother and brother that I never, ever raise my voice at anyone, and I never resort to name-calling during arguments,” she continues. “If I came out more strongly, why couldn’t they?”

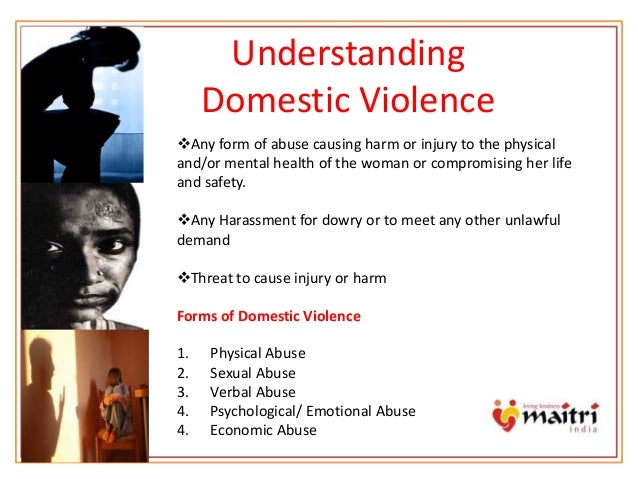

Recognition of the existence of domestic violence

Domestic violence refers to all acts of physical, sexual, psychological or economic violence that occur in the family or in the home between former or current spouses or partners.

Domestic violence is a pattern of behavior used by one person to control or dominate another with whom they have or have had an intimate or family relationship.

Domestic violence is a pattern of behavior used by one person to control or dominate another with whom they have or have had an intimate or family relationship. 8. Why has domestic violence increased during Covid-19?

Reports of domestic violence have increased worldwide during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The social impact of the coronavirus outbreak and its associated restrictions and inability to socialize can increase the tensions inherent in forced cohabitation and increase the risk of domestic violence.

Domestic violence, often perpetrated by men, is deeply rooted in a pattern of patriarchal masculinity in which men have power and control over women. As crisis and uncertainty develop on a personal and family level, abusers may want to regain control and express their resentment at the disruption caused by lockdown by increasing violent outbursts.

The economic downturn caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, accompanied by rising unemployment and loss of income, is especially dangerous for abused women, as economic control is a key tool for abusers. Lack of financial security can force victims to stay with their abusers. It is therefore essential that governments, in all areas of their public policy response to the Covid-19 pandemic, prioritize the issue of intimate partner violence.

Lack of financial security can force victims to stay with their abusers. It is therefore essential that governments, in all areas of their public policy response to the Covid-19 pandemic, prioritize the issue of intimate partner violence.

Sources: UN Women at a glance COVID-19 and ending violence against women and girls; OECD, Women at the Heart of the COVID-19 Crisis

9. Can domestic violence be justified by the perpetrator being under the influence of alcohol or drugs?

There are no excuses for domestic violence. Violence against women is a legacy of treating women as an object or property. Partners who allow themselves to be abused are often protected by a certain level of acceptance in society that violence against women is “normal”.

Stress, drugs and alcohol are factors that increase the risk of domestic violence and can trigger acts of violence. But you can not shift the blame for domestic violence on them. Many people are under stress, use alcohol or drugs, but do not allow themselves to be abused, so neither alcohol nor drugs can be an excuse for any form of violence.

There is also a widespread myth that domestic violence is a “crime of passion”, a momentary loss of control. This happens very rarely. Much more often it is not about losing control, but about establishing control. The abuser establishes control over the person he is abusing.

Source: Help Women

10. Can the behavior of victims/survivors justify domestic violence?

Too often blame for abuse is shifted to victims/survivors and offenders are acquitted. It is believed that he reacted in this way to the provocative behavior of his wife, or she herself asked for it. A woman can be blamed for the fact that she herself is to blame.

But there is no excuse for domestic violence. No one deserves a beating or moral torment.

These widespread and deeply ingrained attitudes are dangerous because any mention of provocation means that we blame the woman and exonerate the abuser from responsibility for his actions. A victim/survivor of violence cannot, under any circumstances, be found guilty of having been abused or abused in any form. Only the one who committed the violence is to blame.

Only the one who committed the violence is to blame.

Source: Help Women

11. Why is blaming the victim dangerous and harmful?

Despite significant social change, men continue to be raised from childhood in patriarchal male-dominated societies and cultures where violence against women is common and acceptable. Unfortunately, women still report that when they become a victim, they are not believed or believe that their wrong behavior was the cause of the violence.

As with any form of gender-based violence, blaming the victim is harmful and dangerous because it allows the perpetrators to be exculpated or partially exempted from punishment. A climate of tolerance for this form of violence can prevent victims/survivors from seeking help or reporting violence, and promote impunity for perpetrators. It is important that anyone who reports abuse feel confident that their report will be taken seriously and listened to.

Source: Domestic Violence and Abuse: A Problem for Trade Unions to Address, UNISON Handbook

12.

Are there male victims/survivors of domestic violence?

Are there male victims/survivors of domestic violence? Although women make up the vast majority of victims/survivors of violence, men and boys can also be victims. Many victims/male survivors of violence are reluctant to report it for fear of not being believed or seen as weak.

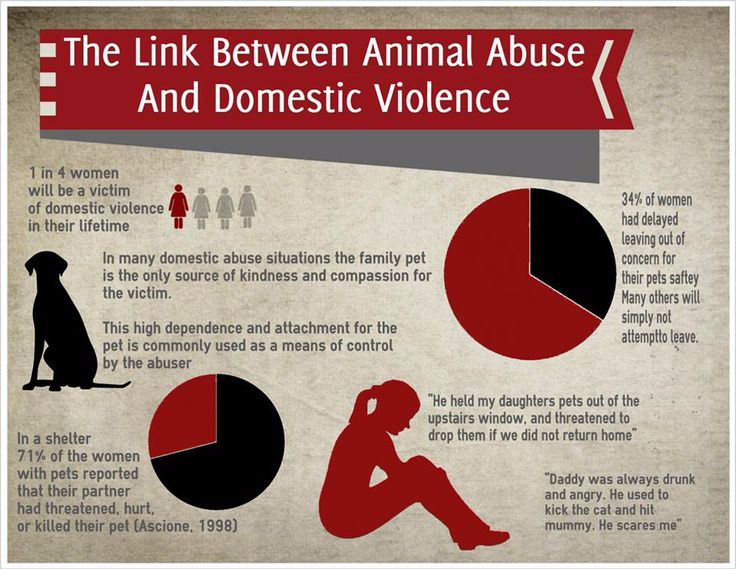

13. Why don't victims of domestic violence walk away from their abusers and report abuse?

Ending an abusive relationship is not easy; The main components of domestic violence are shame and isolation.

Many women are afraid that they will not be believed, they are afraid of losing their children, which is often threatened by abusers. These issues, together with the imposed social exclusion of women in abusive relationships, low self-esteem, financial hardship, and fear of future violence, may lead women to think they have no choice but to continue such relationships, especially if they have children. or other adults they need to take care of.

They stay, hoping that their partners can change. This makes things very complicated and means that simple solutions are rare. Women still feel responsible for maintaining families and relationships. Moreover, the offender knows how to morally hurt the victim/survivor, how to hurt, and often does it subtly, so that others may not even understand it.

This makes things very complicated and means that simple solutions are rare. Women still feel responsible for maintaining families and relationships. Moreover, the offender knows how to morally hurt the victim/survivor, how to hurt, and often does it subtly, so that others may not even understand it.

Victims/survivors of violence may find themselves in a situation where they need to live in temporary housing on welfare, in fear that children may be taken away by child welfare authorities. Breaking up a relationship can mean moving to an unfamiliar place, far away from family and friends.

Sources: Unite Trade Union “Domestic Violence and Abuse. Negotiation Guide; Domestic Violence and Abuse: A Problem for Trade Unions to Address, UNISON Handbook

14. What does Convention No. 190 and Recommendation No. 206 say about gender-based violence?

The preamble to the Convention states that “domestic violence can have an impact on employment, productivity and safety, and that governments and employers' and workers' organizations and labor market institutions can promote, through other measures, recognition of the consequences of domestic violence, responses to them and their proceedings” .

Thus, the Convention requires Member States to “take appropriate measures to … recognize the consequences of domestic violence and, as far as practicable, minimize its impact on the world of work” (Article 10 (f)).

Recommendation contains further guidance. It states that “Members shall take appropriate measures to promote the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining at all levels as a means of […] minimizing the impact of domestic violence on the world of work” (para. 4(a)).

The document lists possible measures to minimize these consequences: granting leave to victims of domestic violence; flexible working hours and protection for victims of domestic violence; temporary protection of victims of domestic violence from dismissal depending on the circumstances, excluding cases not related to domestic violence and its consequences; inclusion of cases of domestic violence in assessments of risk factors in the workplace; a referral system on government measures to mitigate the consequences of domestic violence, where they exist; and awareness-raising activities about the consequences of domestic violence (para. 18).

18).

Source: ILO Convention 190, ILO Recommendation 206

15. Why is domestic violence a problem in the workplace?

Although domestic violence occurs in the home, it can have a negative impact on the world of work.

Perpetrators may stalk their victims on their way to work or use their work computer, email or telephone to pressure, intimidate and control. In addition, abusers may work in the same place as their victims.

Stress and trauma suffered by victims/survivors of domestic violence also affect the world of work, reducing productivity.

People who are subjected to domestic violence are forced to take vacations due to abuse, and they may be late for work. They may have difficulty because of injuries, threats, or because the abuser may take the car keys or steal money to prevent them from getting to work on time.

Domestic violence not only puts the safety of the individual at risk, but also the safety of other workers and can adversely affect the working environment. Work colleagues experience the negative effects of domestic violence due to increased workload, stress, calls or visits from their colleague's abuser, and other potential security risks. Domestic violence can lead to conflict and tension between victims/survivors of domestic violence and their co-workers.

Work colleagues experience the negative effects of domestic violence due to increased workload, stress, calls or visits from their colleague's abuser, and other potential security risks. Domestic violence can lead to conflict and tension between victims/survivors of domestic violence and their co-workers.

The measures taken to deal with the coronavirus crisis and the increase in the number of teleworkers means that for many, the home has become a new place of work. This workplace is dangerous for women who are at risk of domestic violence.

Source: ILO Brief Report on Domestic Violence and its Impact on the World of Work, 2020; ITUC, Providing Workplace Support to Victims of Domestic Violence

The ECtHR has identified measures to be taken by the Russian authorities to combat domestic violence

In a comment by AG, the lawyer for the two applicants noted that the ruling would have a great impact not only on practice at the national level, but also on the development of international standards for the protection of women's rights from domestic violence in general. One of the representatives of the other applicant believes that after such a decision, victims of domestic violence will be able to apply to the ECtHR without having to exhaust domestic remedies and the Court will consider their cases in a simplified and quick manner. According to one of the AG experts, the conclusions of the ECtHR will force the Russian authorities to quickly adopt amendments to the legislation. Another believes that the case considered by the ECtHR is a clear example of how the European Convention is evolving through its interpretation by Strasbourg judges.

One of the representatives of the other applicant believes that after such a decision, victims of domestic violence will be able to apply to the ECtHR without having to exhaust domestic remedies and the Court will consider their cases in a simplified and quick manner. According to one of the AG experts, the conclusions of the ECtHR will force the Russian authorities to quickly adopt amendments to the legislation. Another believes that the case considered by the ECtHR is a clear example of how the European Convention is evolving through its interpretation by Strasbourg judges.

On December 14, the European Court issued a judgment in the case of Tunikova and Others v. Russia on the complaint of four Russian women who had experienced domestic violence.

Reason for applying to the ECtHR and position of the parties

Recall, as previously reported AG, 28 June 2019 The European Court communicated complaints by Natalia Tunikova, Elena Gershman, Margarita Gracheva and Irina Petrakova, which were connected by a single problem - the lack of effective mechanisms in the Russian Federation to combat domestic violence. For this reason, the ECtHR consolidated the applications into one case.

For this reason, the ECtHR consolidated the applications into one case.

In their complaints, the applicants pointed to violations of Art. 3 (“Prohibition of inhuman and degrading treatment”), 13 (“Right to an effective remedy”) and 14 (“Prohibition of discrimination”) of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. They referred to the failure of the Russian authorities to protect them from domestic violence due to shortcomings in domestic legal regulation and the lack of adequate remedies. According to the applicants, they were subjected to extreme forms of domestic violence, which caused them very serious and profound suffering, amounting to “torture” and not “inhuman or degrading treatment”.

Read also

Representatives of victims of domestic violence analyzed the position of the Russian authorities presented to the ECtHR true

December 30, 2019 News

Then the ECtHR put before the parties three questions. First of all, he asked for clarification as to whether the Russian authorities had fulfilled their obligation to protect the applicants from ill-treatment by their partners. In its second question, the Court clarified whether the Russian authorities recognized the seriousness and extent of the problem of domestic violence and its discriminatory impact on women. He also asked if the Russian Federation is taking any measures to achieve real gender equality and protect men and women equally from domestic violence. Noting that in the Russian Federation there is no special legislation aimed at combating domestic violence, the European Court asked the third question: is there a systemic problem of domestic violence in Russia that requires a response from the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe?

First of all, he asked for clarification as to whether the Russian authorities had fulfilled their obligation to protect the applicants from ill-treatment by their partners. In its second question, the Court clarified whether the Russian authorities recognized the seriousness and extent of the problem of domestic violence and its discriminatory impact on women. He also asked if the Russian Federation is taking any measures to achieve real gender equality and protect men and women equally from domestic violence. Noting that in the Russian Federation there is no special legislation aimed at combating domestic violence, the European Court asked the third question: is there a systemic problem of domestic violence in Russia that requires a response from the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe?

On October 22, 2019, the Government of the Russian Federation sent memorandums on each of the complaints. With the exception of separate explanations on the circumstances of the applicants' cases, the responses of the Russian authorities are identical (the documents are available from AG).

In particular, the authorities did not agree with the assertion that the mechanism for bringing the aggressor to criminal liability by way of private prosecution was ineffective. According to the Russian authorities, this approach is explained by the peculiarities of these crimes: the public danger of the act in this case is inseparable from the personal assessment of what happened by the victim and therefore cannot be formally objectified, including by law enforcement agencies. In support of this, the Government referred to the prohibition of excessive interference with private and family life. The Government also emphasized the importance of ensuring that the victim is able to resolve the conflict with the abuser on their own in order to maintain normal family relations.

The Russian side did not deny that the state should guarantee the prohibition of inhuman and degrading treatment. However, in her opinion, Art. 3 of the Convention requires the active participation of the state in solving family problems only as long as the victim faces a real and imminent threat of death. On this basis, the authorities of the Russian Federation came to the conclusion that they have fully complied with the obligation to create a legislative framework that addresses the problem of domestic violence as effectively as other forms of violence.

On this basis, the authorities of the Russian Federation came to the conclusion that they have fully complied with the obligation to create a legislative framework that addresses the problem of domestic violence as effectively as other forms of violence.

The European Court revealed imperfections in Russian legislation

After examining the case file and the arguments of the parties, the ECtHR noted that all four applicants had been subjected to physical violence by their former partners or husbands, which was confirmed by medical documentation, as well as police data. Thus, Natalya Tunikova was beaten on the head, which led to a concussion and various bruises, Elena Gershman was attacked at home and outside, as was Irina Petrakova, who endured this for seven years. In turn, the husband of Margarita Gracheva not only beat her, but also chopped off her hands, making her disabled for life. Thus, the Court noted, the nature of the physical pain and injuries caused indicates that the cases in question went beyond the limits of cruelty provided for by Art. 3 of the Convention. In addition, the psychological pressure and the unrest experienced increased the applicants' vulnerability, brought them into a state of fear, as well as emotional and psychological stress. The Court considers that these psychological aspects were serious enough to be equated with cases falling within the scope of Art. 3 of the Convention.

3 of the Convention. In addition, the psychological pressure and the unrest experienced increased the applicants' vulnerability, brought them into a state of fear, as well as emotional and psychological stress. The Court considers that these psychological aspects were serious enough to be equated with cases falling within the scope of Art. 3 of the Convention.

Having examined the arguments of the Russian side, the European Court considered that the current Russian legislation lacked a definition of “domestic violence”, adequate substantive and procedural legal provisions for the prosecution of its various forms, as well as any form of restraining orders. Consequently, it falls short of the requirements of the State's positive obligation to establish and effectively enforce a system of punishment for all forms of domestic violence and to provide adequate safeguards for victims.

The court also heeded the applicants' arguments that none of them could count on even the minimum measures of protection. None of the police or prosecutors they approached had special training or qualifications to deal with cases of domestic violence. The police remained completely passive despite reports of systematic violence against them. Law enforcement officers did not explain to women how to protect themselves in cases of violence, did not assess the risks associated with their situation, did not warn them about the risk of repeated acts of violence, did not discuss any security issues with them, did not offer any protection measures, and did not tell them where they were may receive legal, psychological or social support.

None of the police or prosecutors they approached had special training or qualifications to deal with cases of domestic violence. The police remained completely passive despite reports of systematic violence against them. Law enforcement officers did not explain to women how to protect themselves in cases of violence, did not assess the risks associated with their situation, did not warn them about the risk of repeated acts of violence, did not discuss any security issues with them, did not offer any protection measures, and did not tell them where they were may receive legal, psychological or social support.

In doing so, the European Court noted, the Russian authorities paved the way for new episodes of violence. In his opinion, the Russian authorities are not capable of investigating credible reports of ill-treatment and ensuring that those responsible are prosecuted and punished. In this connection, the Court considered that Russia had failed in its duty to investigate the ill-treatment suffered by the four Russian women. The Court also agreed with the applicants' argument that the present case illustrated the general failure of the domestic authorities to investigate credible allegations of ill-treatment and to prosecute and punish those responsible.

The Court also agreed with the applicants' argument that the present case illustrated the general failure of the domestic authorities to investigate credible allegations of ill-treatment and to prosecute and punish those responsible.

Gender discrimination in the context of domestic violence could receive protection from domestic violence from the authorities

July 11, 2019 News

The ECtHR has also pointed out that violence against women, including domestic violence, is a form of gender-based discrimination. The state's failure to protect women from domestic violence violates their right to equal protection of the law, whether or not such failure to act is intentional. With reference to the Judgment in the case of Valery Volodina v. Russia, the Court noted that women make up the vast majority of victims of domestic violence according to statistics. Violence against women often goes unreported and they are much less likely to be prosecuted and convicted of their perpetrators. Thus, the Russian authorities have failed to create conditions for real gender equality, which would allow women to live without fear of ill-treatment or attacks on their physical and psychological integrity.

Thus, the Russian authorities have failed to create conditions for real gender equality, which would allow women to live without fear of ill-treatment or attacks on their physical and psychological integrity.

The ECHR also stated that Russia has not yet adopted a law on the prevention of domestic violence, and the relevant bill itself was returned to its originator. The European Court has emphasized that domestic violence is a complex phenomenon affecting all social strata, which manifests itself in various forms, intensities and dynamics, often invisible to outsiders and hidden from the authorities. In order to fulfill their obligations under the Convention, national authorities must develop comprehensive and targeted responses covering all areas of State action, including legislation, public policies, programmes, institutional structures and monitoring mechanisms.

The Court also considered that the refusal of the Russian authorities to consider reports of domestic violence stemmed from gaps in substantive and procedural law. To address these shortcomings, the Russian authorities should immediately review or amend the legislation to bring it into line with the Convention and international standards for the prevention and punishment of domestic violence. Protection from domestic violence should cover current and former family members, spouses and partners, whether they live under the same roof or apart.

To address these shortcomings, the Russian authorities should immediately review or amend the legislation to bring it into line with the Convention and international standards for the prevention and punishment of domestic violence. Protection from domestic violence should cover current and former family members, spouses and partners, whether they live under the same roof or apart.

Thus, the ECtHR found violations of Art. 3 of the Convention in its substantive and procedural aspects, as well as the violation of Art. 14 in conjunction with art. 3. In this regard, the Court awarded Margarita Gracheva EUR 40,000 and the others EUR 20,000 in respect of non-pecuniary damage. All applicants will receive 5,000 euros in compensation for their court costs. Margarita Gracheva will also receive over 330,000 euros in compensation for material damage.

The applicants' representatives assessed the findings of the Court

In a commentary to AG, Mari Davtyan, the lawyer of the Moscow Legal Center, who represented the interests of Margarita Gracheva and Irina Petrakova at the ECtHR, noted that the ruling would certainly have a great impact not only on practice at the national level, but also on the development of international standards for the protection of women's rights against domestic violence: "It is important to note that this is the first pilot judgment in the history of the European Court in the case of domestic violence. "

"

See also

The ECtHR awarded compensation to a woman who was subjected to cyber violence

The court stated that, although the authorities had the necessary legal instruments, they had done nothing to prosecute the applicant's former partner who published her intimate photos on the Web

16 September 2021 News

According to the lawyer, the ECHR ruling once again emphasizes that domestic violence in Russia is a mass phenomenon and that the country lacks a systematic approach to the prevention and protection of victims. “Despite the fact that the European Court has previously pointed out to Russia the systemic shortcomings of protection against domestic violence in the Volodina v. Russia case, the Russian Federation continues to ignore its direct obligation to take active measures to protect the right of victims not to be subjected to domestic violence and discrimination. The Court, adhering to its principles and standards, which it developed in its previous practice, not only recognized that Russia had violated its obligations to protect women from domestic violence, but also ordered the state to take general comprehensive measures to eliminate the structural and discriminatory problem - the lack of protection women from domestic violence, including the immediate introduction of amendments to the legislation to bring it into line with the Convention and international standards for the prevention and punishment of domestic violence,” said Mari Davtyan.

She added: if the Court adopted a pilot judgment, this means that Russia will no longer be able to remain inactive and not take systemic and structural measures against domestic violence. “We very much hope that the Russian Federation will finally adopt a law against domestic violence and carry out a number of structural reforms to create an effective system for the prevention of domestic violence against women,” the lawyer concluded.

Tatyana Savvina, a lawyer for the Legal Initiative project (recognized in the Russian Federation as an NPO acting as a foreign agent. - Ed.), who represented the interests of Elena Gershman in the European Court, called the decision an important and expected step. “Today, Russia remains practically the only country in Europe where there is no comprehensive legislation punishing all forms of domestic violence and providing protective measures for victims. The cases of Elena Gershman or Irina Petrakova clearly show how the current Russian legislation helps the aggressor to go unpunished for numerous and systemic episodes of beatings. And the shocking case of Margarita Gracheva demonstrates how the complete indifference and inability of law enforcement agencies to protect victims in a situation of domestic violence lead to tragedy. The cases of these women are not some rare exception to the rule, but a consequence of the defectiveness of Russian legal regulation in the field of domestic violence,” she is convinced.

And the shocking case of Margarita Gracheva demonstrates how the complete indifference and inability of law enforcement agencies to protect victims in a situation of domestic violence lead to tragedy. The cases of these women are not some rare exception to the rule, but a consequence of the defectiveness of Russian legal regulation in the field of domestic violence,” she is convinced.

According to the lawyer, this pilot judgment of the ECtHR was all the more expected, since two years after the Volodina v. Russia case, where the Court for the first time indicated that there was no adequate regulation in the field of domestic violence in Russia, nothing was done by the Russian authorities, to rectify the situation, while the number of complaints from Russian citizens to the ECtHR on domestic violence continued to grow.

“Now the Court has indicated a list of specific and clear measures that Russia needs to take immediately. These are both legislative measures (introduction of a legislative definition of domestic violence, criminal liability, protection orders, etc. ), and measures of a different nature (for example, rehabilitation programs for aggressors, mandatory trainings on domestic violence for judges, investigators, police officers, etc.). I hope that the Russian authorities will take these measures in the near future. In the meantime, victims of domestic violence will be able to apply to the ECtHR without the need to exhaust domestic remedies (since the Court found them ineffective), and the Court will consider their cases in a simplified and quick manner,” Tatiana Savvina emphasized.

), and measures of a different nature (for example, rehabilitation programs for aggressors, mandatory trainings on domestic violence for judges, investigators, police officers, etc.). I hope that the Russian authorities will take these measures in the near future. In the meantime, victims of domestic violence will be able to apply to the ECtHR without the need to exhaust domestic remedies (since the Court found them ineffective), and the Court will consider their cases in a simplified and quick manner,” Tatiana Savvina emphasized.

It was not possible to promptly obtain comments from other representatives of the applicants.

AG experts upheld the findings of the Court

Sergei Knyazkin, a lawyer for the Center for International Human Rights Protection, believes that the case considered by the ECtHR will significantly affect the situation with domestic violence in Russia. “This is a pilot decision of the European Court, which not only sets out a statement of violations of rights under the Convention, but also indicates recommendations for bringing national legislation in line with European standards. The problem with domestic violence is very relevant in Russia, however, the mentality of certain high-ranking officials in the government and the deputy corps of Russia does not allow the adoption of the Law on the Prevention of Domestic Violence in the Russian Federation, which has been submitted to the State Duma for several years in a row,” he said.

The problem with domestic violence is very relevant in Russia, however, the mentality of certain high-ranking officials in the government and the deputy corps of Russia does not allow the adoption of the Law on the Prevention of Domestic Violence in the Russian Federation, which has been submitted to the State Duma for several years in a row,” he said.

The lawyer expressed confidence that the requirements of the European Court to bring the national legislation of Russia on the situation with domestic violence in line with European standards will allow for the rapid adoption of a law that will significantly reduce this negative aspect in Russian society. “The unprecedented amount for the European Court of indemnification for material and moral damage to an individual - more than 370 thousand euros will draw attention to this problem both in Russia and abroad. There have already been many positive changes in Russian legislation after the pilot judgments of the European Court. A significant improvement in the situation in penitentiary institutions, the reform of the cassation proceedings in criminal cases and the introduction of a “solid” cassation, the disappearance of iron cages in courtrooms, etc. After this high-profile case, I hope that already in 2022 the Law on the Prevention of Domestic Violence will be adopted in Russia and the situation in ensuring equal rights in the family will improve significantly,” Sergey Knyazkin expressed his hope.

A significant improvement in the situation in penitentiary institutions, the reform of the cassation proceedings in criminal cases and the introduction of a “solid” cassation, the disappearance of iron cages in courtrooms, etc. After this high-profile case, I hope that already in 2022 the Law on the Prevention of Domestic Violence will be adopted in Russia and the situation in ensuring equal rights in the family will improve significantly,” Sergey Knyazkin expressed his hope.

An expert on working with the European Court, Anton Ryzhov, believes that the case considered by the ECHR is a clear example of how the European Convention is evolving through its interpretation by Strasbourg judges. “There is a so-called horizontal effect of the Convention, when it applies to a much wider range of social relations than was planned at the time of its development and adoption. In fact, now it is possible to “sue” the state for what happens between private individuals, while 30 years ago it was pointless to file such complaints with the European Court. The logic of the judges of the ECHR is approximately as follows: the authorities must protect the health and well-being of their citizens, especially in a situation where the state, for certain reasons, is aware of the ongoing turmoil or outrages. And if such an unpleasant fact has occurred, then the state, represented by the competent authorities, is obliged to conduct a thorough investigation of the incident and punish those responsible,” he stressed.

The logic of the judges of the ECHR is approximately as follows: the authorities must protect the health and well-being of their citizens, especially in a situation where the state, for certain reasons, is aware of the ongoing turmoil or outrages. And if such an unpleasant fact has occurred, then the state, represented by the competent authorities, is obliged to conduct a thorough investigation of the incident and punish those responsible,” he stressed.

According to the lawyer, in this case, the European Court applied these principles, recognizing both the lack of protection for women victims of domestic violence and the lack of a proper investigation into the facts of bullying (as usual, the judges rejected the domestic pre-investigation check, which in the overwhelming majority of cases entails unmotivated refusal to initiate a criminal case). “In addition, the ECHR recognized the fact of discrimination against Russian women, who from year to year in vain expect the adoption of targeted legislation on domestic violence.