Validate definition psychology

Understanding Validation: A Way to Communicate Acceptance

One of the four options we have in any problem situation is acceptance. Validation is one way that we communicate acceptance of ourselves and others. Validation doesn't mean agreeing or approving. When your best friend or a family member makes a decision that you really don't think is wise, validation is a way of supporting them and strengthening the relationship while maintaining a different opinion. Validation is a way of communicating that the relationship is important and solid even when you disagree on issues.

Validation is the recognition and acceptance of another person's thoughts, feelings, sensations, and behaviors as understandable. Self-validation is the recognition and acceptance of your own thoughts, feelings, sensations and behaviors as understandable.

Learning how to use validation effectively takes practice. Knowing the six levels of validation as identified by Marsha Linehan, Ph.D. will be helpful.

The first level is being present. There are so many ways to be present. Holding someone's hand when they are having a painful medical treatment, listening with your whole mind and doing nothing but listening to a child describe their day in first grade, and going to a friend's house at midnight to sit with her while she cries because a supposed friend told lies about her are all examples of being present.

Multi-tasking while you listen to your teenager's story about his soccer game is not being present. Being present means giving all your attention to the person you are validating.

Being present for yourself means acknowledging your internal experience and sitting with it rather than "running away" from it, avoiding it, or pushing it away. Sitting with intense emotion is not easy. Even happiness or excitement can feel uncomfortable at times.

Often one of the reasons other people are uncomfortable with intense emotion is that they don't know what to say. Just being present, paying complete attention to the person in a nonjudgmental way, is often the answer. For yourself, being mindful of your own emotion is the first step to accepting your emotion.

Just being present, paying complete attention to the person in a nonjudgmental way, is often the answer. For yourself, being mindful of your own emotion is the first step to accepting your emotion.

The second level of validation is accurate reflection. Accurate reflection means you summarize what you have heard from someone else or summarize your own feelings. This type of validation can be done by others in an awkward, sing-songy, artificial way that is truly irritating or by yourself in a criticizing way. When done in an authentic manner, with the intent of truly understanding the experience and not judging it, accurate reflection is validating.

Sometimes this type of validation helps someone sort through their thoughts and separate thoughts from emotions. "So basically I'm feeling pretty angry and hurt," would be a self-reflection. "Sounds like you're disappointed in yourself because you didn't call him back," could be accurate reflection by someone else.

Level three is mindreading . Mindreading is guessing what another person might be feeling or thinking. People vary in their ability to know their own feelings. For example, some confuse anxiety and excitement and some confuse excitement and happiness. Some may not be clear about what they are feeling because they weren't allowed to experience their feelings or learned to be afraid of their feelings.

People may mask their feelings because they have learned that others don't react well to their sensitivity. This masking can lead to not acknowledging their feelings even to themselves, which makes the emotions more difficult to manage. Being able to accurately label feelings is an important step to being able to regulate them.

When someone is describing a situation, notice their emotional state. Then either name the emotions you hear or guess at what the person might be feeling.

"I'm guessing you must have felt pretty hurt by her comment" is Level Three validation. Remember that you may guess wrong and the person could correct you. It's her emotion and she is the only one who knows how she feels. Accepting her correction is validating.

Remember that you may guess wrong and the person could correct you. It's her emotion and she is the only one who knows how she feels. Accepting her correction is validating.

Level four is understanding the person's behavior in terms of their history and biology. Your experiences and biology influence your emotional reactions. If your best friend was bitten by a dog a few years ago, she is not likely to enjoy playing with your German Shepherd. Validation at this level would be saying, "Given what happened to you, I completely understand your not wanting to be around my dog."

Self-validation would be understanding your own reactions in the context of your past experiences.

Level five is normalizing or recognizing emotional reactions that anyone would have. Understanding that your emotions are normal is helpful for everyone. For the emotionally sensitive person, knowing that anyone would be upset in a specific situation is validating. For example, "Of course you're anxious. Speaking before an audience the first time is scary for anyone."

Speaking before an audience the first time is scary for anyone."

Level six is radical genuineness. Radical genuineness is when you understand the emotion someone is feeling on a very deep level. Maybe you have had a similar experience. Radical genuineness is sharing that experience as equals.

Understanding the levels may be easy. Putting them into practice is often more difficult. Practice is the key to making validation a natural part of the way you communicate.

Consider this example. Your best friend is upset because her husband cut up her credit card. She says he's treating her like a child and is so controlling she doesn't have room to breathe. When you ask her what his reason was, she says that she overspent for the fourth time, running the balance over the limit by buying expensive shoes and they were unable to pay the bill. How do you validate her? Remember to use the highest possible level. Think of your answer before you read further!

Probably Level 2 is the highest level you could use. You could say, "I understand, you are upset because your husband cut up your credit cards without your agreement—-that made you feel like he was acting like your parent." You reflect her thoughts and emotions back to her, showing that you accept those feelings as her internal experience.

You could say, "I understand, you are upset because your husband cut up your credit cards without your agreement—-that made you feel like he was acting like your parent." You reflect her thoughts and emotions back to her, showing that you accept those feelings as her internal experience.

You probably couldn't use Level 6 or radical genuineness as it's unlikely you have similar experiences that you could understand her feelings on a deep level, such as having had the same experience and reaction. Level 5, normalizing, would not work because most people would agree his response was reasonable and not be upset in that situation. There is nothing to make her response more understandable in terms of her history, so Level 4 is not possible. Level 3 is also not applicable because she's told her feelings clearly--nothing to guess.

Let's try another example. Jesse tells you she quit her job. She quit because her boss loudly criticized her in front of other people. She's asked him twice before to not embarrass her but he loses his temper easily. She felt afraid of him because he reminded her of a verbally abusive uncle and she couldn't continue to work for him. What level of validation do you use?

She felt afraid of him because he reminded her of a verbally abusive uncle and she couldn't continue to work for him. What level of validation do you use?

Level 6 or Level 5 might work in this situation. If you have been in a similar situation or you really understand how she felt, you can validate her by saying, "I completely understand. I would have done the same thing." That would be Level 6. Level 5 would be, "I think most people would have felt the same way you did."

Though she has a history of being verbally abused, you don't use Level 4 because Level 5 fits. Always use the highest level possible. Level 4 would be to say, "Given your history of being verbally abused, I understand why you would quit." That's actually invalidating because anyone, whether they had a history of being verbally abused or not, would be upset if their boss humiliated them.

Joanna calls you and talks about her diet. She complains that she has eaten chocolate cake and other sweets and wants to eat more, but she doesn't want to gain weight. What level of validation can you use?

What level of validation can you use?

Level 3 would be a good choice. Joanna didn't mention any feelings though she is eating for emotional reasons. You could say, "Has something happened? My guess is you're upset about something." Then she might tell you that the cat she's had for six months died yesterday. At that point you could use a Level 5 or 6, depending on how you feel about losing a pet.

When Shawna was a teenager, she almost drowned in a large pond. She was a poor swimmer and swam out further than she realized. When she stopped swimming, her feet couldn't touch bottom and she swallowed water. She panicked and a friend swam to save her. Since that time she's been afraid of water. A neighbor invited her to a pool party. A guy who was flirting with her pushed her into the pool and she panicked, even though she was only in waist high water. She tells you that she's ashamed of her reaction and she hates being crazy.

Level 4 validation would work in this situation. "Given your history of almost drowning, of course you panicked when you were pushed into water. Anyone with a history of drowning would probably react the same way."

"Given your history of almost drowning, of course you panicked when you were pushed into water. Anyone with a history of drowning would probably react the same way."

Emotional Invalidation

Emotional invalidation is when a person's thoughts and feelings are rejected, ignored, or judged. Invalidation is emotionally upsetting for anyone, but particularly hurtful for someone who is emotionally sensitive.

Invalidation disrupts relationships and creates emotional distance. When people invalidate themselves, they create alienation from the self and make building their identity very challenging.

Self-invalidation and invalidation by others make recovery from depression and anxiety particularly difficult. Some believe that invalidation is a major contributor to emotional disorders.

Most people would deny that they invalidate the internal experience of others. Very few would purposefully invalidate someone else. But well-intentioned people may be uncomfortable with intense emotions or believe that they are helping when they are actually invalidating.

In terms of self-invalidation, many people would agree they invalidate themselves, but would argue that they deserve it. They might say they don't deserve validation. They are uncomfortable with their own humanness. The truth is that validation is not self-acceptance, it is only an acknowledgement that an internal experience occurred.

Verbal Invalidation

There are many different reasons and ways that people who care about you invalidate you. Here are just a few.

Misinterpreting what it means to be close: Sometimes people think that knowing just how someone else feels without having to ask means they are emotionally close to that person. It's like saying they know you as well as you know you, so they don't ask, they assume, and may even tell you how you think and feel.

Misunderstanding what it means to validate:

Sometimes people invalidate because they believe if they validate they are agreeing. A person can state, "You think it's wrong that you're angry with your friend," and not agree with you. Validation is not agreeing. But because they want to reassure you they invalidate by saying, "You shouldn't think that way."

Validation is not agreeing. But because they want to reassure you they invalidate by saying, "You shouldn't think that way."

Wanting to fix your feelings: "Come on, don't be sad. Want some ice cream?" People who love you don't want you to hurt so sometimes they invalidate your thoughts and feelings in their efforts to get you to feel happier.

Not wanting to hurt your feelings: Sometimes people lie to you in order to not hurt your feelings. Maybe they tell you that you look great in a dress that in truth is not the best style for you. Maybe they agree that your point of view in an argument when in fact they do not think you are being reasonable.

Wanting the best for you: People who love you want the best for you. So they may do work for you that you could do yourself. Or they encourage you to make friends with someone who is influential when you don't really enjoy the person, telling you that that person is a great friend when it's not true. "You should be friends with her. She'll be a good friend to you."

"You should be friends with her. She'll be a good friend to you."

There are also many different ways of invalidating. I've listed a few below.

Blaming: "You always have to be the crybaby, always upset about something and ruin every holiday." "Why didn't you put gas in the car before you got home? You never think and always make everything harder." Blaming is always invalidating. (Blaming is different from taking responsibility.)

Hoovering: Hoovering is when you attempt to vacuum up any feelings you are uncomfortable with or not give truthful answers because you don't want to upset or to be vulnerable. Saying "It's not such a big deal" when it is important to you is hoovering. Saying someone did a great job when they didn't or that your friends loved them when they didn't is hoovering. Not acknowledging how difficult something might be for you to do is hoovering. Saying "No problem, of course I can do that," when you are overwhelmed, is hoovering.

Judging: "You are so overreacting," and "That is a ridiculous thought," are examples of invalidation by judging. Ridicule is particularly damaging: "Here we go again, cry over nothing, let those big tears flow because the grass is growing."

Denying: "You are not angry, I know how you act when you're angry," and "You have eaten so much, I know you aren't hungry," invalidate the other person by saying they don't feel what they are saying they feel.

Minimizing: "Don't worry, it's nothing, and you're just going to keep yourself awake tonight over nothing" is usually said with the best of intentions. Still, the message is to not feel what you are feeling.

Nonverbal Invalidation

Nonverbal invalidation is powerful and includes rolling of the eyes and drumming of fingers in an impatient way. If someone checks their watch while you are talking with them, that is invalidating. Showing up at an important event but only paying attention to email or playing a game on the phone while there is invalidating, whether that is the message the person meant to send or not.

Nonverbal self-invalidation is working too much, shopping too much or otherwise not paying attention to your own feelings, thoughts, needs and wants.

Replacing Invalidation With Validation

The best way to stop invalidating others or yourself is by practicing validation. Validation is never about lying. Or agreeing. It's about accepting someone else's internal experience as valid and understandable. That's very powerful.

What Is Validation in Therapy & Why Is It Important?

Validation means that you understand where the other person is coming from, even if you disagree with what they say or do (Rather & Miller, 2015).

Recognizing that someone’s feelings and thoughts make sense can show that we are listening nonjudgmentally and can help build stronger relationships, especially in therapy.

It can be tricky. Crucially, we need to validate what the person feels, but not always their behavior (Rather & Miller, 2015).

This article explores the role and importance of validation in therapy before introducing helpful worksheets to improve validation skills and support a positive outcome.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Relationships Exercises for free. These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients build healthy, life-enriching relationships.

This Article Contains:

- What Is Validation in Therapy? 9 Examples

- Why Is Validation Important?

- The Psychology Behind Validation

- 6 Helpful Validation Worksheets

- 25 Validation Statements to Use in Therapy

- Validation in DBT: A Brief Explanation

- The Power of Validation in All Relationships

- Resources From PositivePsychology.com

- A Take-Home Message

- References

What Is Validation in Therapy? 9 Examples

Validation within therapy encourages and supports the understanding and acceptance of the client’s experiences, both verbally and nonverbally. It signifies that clients are heard and that their behavior is understandable (even if not appropriate) in their given context (Kocabas & Üstündağ‐Budak, 2017).

Validation is part of the process that establishes the truth or validity of what is said in therapy (American Psychological Association, 2020).

Types of validation in therapy sessions vary, yet they typically include the following (Rather & Miller, 2015; Dietz, n.d.; Kocabas & Üstündağ‐Budak, 2017):

- Active listening – remaining focused, attentive, and in the moment while maintaining eye contact

- Mindfully responding – monitoring verbal and nonverbal reactions to what is said

- Reflecting without judgment – recognizing and verbalizing what the client is feeling (such as, “I can see you are having a tough time at the moment”)

- Being tolerant – even if not in agreement with the client’s behavior, considering their history and how their thoughts and feelings may make sense

- Showing that what they say is taken seriously – such as acknowledging that something happening sounds awful, offering a tissue, or asking, “What do you need right now?” Acceptance throughout the session is crucial.

- Restating what was said – summarizing and simplifying what is said (verbally and nonverbally) by the client by providing accurate reflection (such as, “You think it is unfair that you do all the housework, and you would like things to change.”)

- Focusing on behaviors – pointing out that the current behavior may be unhelpful and has not always worked in the past

- Treating the person as an equal – seeing the client as an equal and showing them the respect they deserve

- Radical genuineness – believing in the client’s strengths and respecting that they are capable of change

Why Is Validation Important?

The relationship between the therapist and client, known as the therapeutic alliance, is a crucial indicator of a successful outcome in therapy (Eubanks, Burckell, & Goldfried, 2018).

The process of validation underpins that alliance during treatment. The therapist’s understanding and acceptance are vital aspects of the therapeutic process, ultimately encouraging growth (Kocabas & Üstündağ‐Budak, 2017).

The therapist’s understanding and acceptance are vital aspects of the therapeutic process, ultimately encouraging growth (Kocabas & Üstündağ‐Budak, 2017).

Confidence in such a trust-related relationship supports the client as they “explore and attempt the tasks that lead to therapeutic change and growth” (Kocabas & Üstündağ‐Budak, 2017, p. 319).

Validation in therapy supports the process through a combination of the following (Rather & Miller, 2015):

- Improving relationships – particularly the therapeutic alliance

- Deescalating intense emotions and conflict

- Communicating that the client is:

- Listened to

- Understood

- Not being judged

- Disagreeing with the client when appropriate yet avoiding major conflict

Validation in therapy creates a positive environment for treatment, helping the client feel accepted, understood, and not judged, and strengthens the bond between therapist and client (Kocabas & Üstündağ‐Budak, 2017).

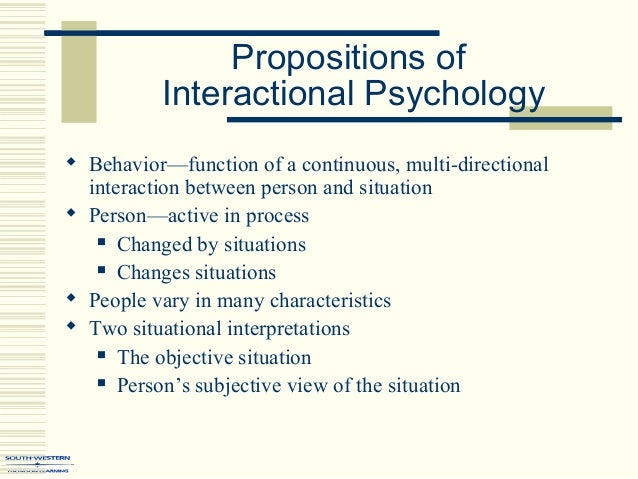

The Psychology Behind Validation

Research continues to provide support for the value of validation in therapy and elsewhere. It confirms that the content of the message must remain crucial (Tian, Solomon, & Brisini, 2020).

As far back as 1997, Marsha Linehan recognized that validation involves both empathic understanding and communication. Empathy alone is not sufficient; therapy must go further, drawing conclusions and communicating what was heard (Linehan, 1997).

Messages of support have the power to help those facing a variety of stressors by improving their degree of self-confidence and self-esteem, reducing psychological distress.

Supporting behaviors perceived as beneficial can result in the helper being recognized as sensitive and considerate. Other actions viewed as unhelpful may result in psychological reactance, promoting unwanted behavior (Tian et al., 2020).

When handled carefully and with sensitivity, support messages can provide the required validation to help people during challenging times in their lives, such as illness, marital disagreement, and poor physical health (Tian et al. , 2020).

, 2020).

6 Helpful Validation Worksheets

The following worksheets can help you develop your validation skills (inside and outside therapy) and become better at hearing, accepting, and understanding what the other person has to say.

How Are You Validating Other People?

Use the How Are You Validating Other People? worksheet to review a recent session with a client and assess how well you validated them, verbally and nonverbally (modified from Rather & Miller, 2015).

Reflect on an earlier session or part of a session, consider your validation skills and techniques, and answer the following questions:

- Were you actively listening?

- Were you mindful of your verbal/nonverbal reactions?

- Could you sum up what they were feeling in a word?

- Were you able to reflect back on what they said without judgment?

- Did you show tolerance?

- Did you respond in such a way that showed you were taking the other person seriously?

Reflect on each answer. What went well? What could you do better next time?

What went well? What could you do better next time?

What Is Your Validating Style?

The What Is Your Validating Style? worksheet is a helpful way to practice and verify your validation skills in any situation (modified from Linehan, 2015).

- Describe a situation where you were successful at being nonjudgmental in the past week.

- Describe a situation where you were successful at using your validation skills in the past week.

Then consider whether there is anything you would say or do differently the next time a similar situation arises.

Levels of Validation

Validation can be performed at several levels and assessed using the Levels of Validation worksheet (Kocabas & Üstündağ‐Budak, 2017; Linehan 1997).

Consider your ability to validate and the level you are typically validating at:

- Level one – Am I mindfully listening?

Do I listen with empathy? Do I stop what I am doing and pay full attention? - Level two – Am I accurately reflecting and acknowledging what is being said?

Am I able to play back the essence of what has been said, showing an accurate understanding? - Level three – Can I articulate the nonverbalized emotions, thoughts, and behavior?

Can I ask follow-up questions that confirm what the person is feeling or thinking? - Level four – Can I place the problem behavior in a broader context?

Do I consider the impact of how the person’s past has shaped and developed their existing problem behavior? - Level five – Can I normalize and attend to the present context?

Do I use phrases such as, “This makes sense to me, considering…”? - Level six – Do I use radical genuineness?

Do I see the other person as fragile and unable to change, or do I treat them with equality and respect?

Neutralizing Judgmental Thoughts

Sometimes it is difficult to avoid judging someone based on how they look, behave, or what they say.

In the Neutralize Judgmental Thoughts worksheet, we use the acronym CLEAR to adopt a less critical outlook when dealing with others (modified from Linehan, 2015).

- Categorize your thoughts and recognize any judgments.

- Leave behind any thoughts that adopt a (good or bad) “should” viewpoint.

- Evaluate the consequences and benefits of the actions.

- Accept the reality.

- Remind yourself that things often make sense because of the reasons around them and the context in which they happened.

Self-Validation and Self-Respect

Clients can use the process of validation on themselves as a positive method for improving self-confidence and self-esteem.

Try out the Self-Validation and Self-Respect worksheet with your client to improve their self-validation skills.

- Consider three self-validating statements you have used in the past week, such as:

- I reminded myself that there is a cause to all behavior and that I am doing my best.

- I was compassionate to myself.

- I admitted to myself that it is hard when someone invalidates me, even when they are correct.

- I acknowledged that my reactions made sense and are valid in this context.

- Any others?

- I reminded myself that there is a cause to all behavior and that I am doing my best.

- What was the outcome?

- What worked? What could you do differently?

Validating Your Child’s Opposite Sides

It can be difficult letting children experience conflicting thoughts and emotions, yet it is a crucial part of their development and an important use of validation.

Use the Validating Your Child’s Opposite Sides worksheet to help the child see that it is possible to hold more than one, seemingly conflicting, thought or belief (modified from Linehan, 2015).

Ask the child to review the following list of opposites that can both be true:

- You can be tough and gentle.

- You can be independent and want help.

- You can want to be alone and want to be connected with others.

- You can be with others and be lonely.

- You can accept yourself and still want to change.

- You may have good reason to believe what you believe and still be wrong.

- The day can be sunny, and it can rain.

- You can disagree with rules and follow them.

Explain to the child that sometimes we must accept that we can hold many different and sometimes confusing thoughts, and that we should be accepting and compassionate (self-validating) with ourselves.

25 Validation Statements to Use in Therapy

Using the right verbal cues and wording is essential for successful validation in therapy; examples include the following (modified from Validating statements, n.d.):

- What do you need from me now?

- How can I help?

- What was that like for you?

- This must be difficult for you.

- How is this affecting you?

- How are you feeling?

- You are not alone.

- Can I help you with some problem solving?

- What does safety (happiness, etc.) mean for you?

- I’m sorry to hear that.

- I hear what you are saying.

- I believe you.

- I understand.

- I hear you.

- Can you tell me more about that?

- It sounds like you did your best.

- Most people would have reacted in that way.

- I am so sorry that happened, and I am so glad you are here.

- I can’t imagine what you went through.

- You are very strong and brave.

- I can see that you are very (sad, upset, frightened, etc.).

- I can see you are making an effort.

- It must make you feel horrible to have someone do that to you.

- I would be (scared, upset, sad, etc.) too.

- I don’t have the same beliefs, but I can see this is important to you.

Validation in DBT: A Brief Explanation

Validation plays a significant role in Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT).

As one of its core strategies, validation helps clients learn and implement skills for themselves (Carson-Wong, Hughes, & Rizvi, 2018).

As DBT is seen as a client-centered therapy, it is vital that the client feels understood, accepted, and equal to the therapist. Only then can the client focus entirely on acquiring effective skills and appropriate cognitive-behavioral strategies to grow and change (Kocabas & Üstündağ‐Budak, 2017).

In DBT, validation signals that the therapist understands the client’s behavior, acknowledging their thoughts and emotions within their existing context. For therapy to be successful, that understanding must be communicated back to the client, recognizing rather than dismissing the meaning and importance of the experience to them (Kocabas & Üstündağ‐Budak, 2017).

The Power of Validation in All Relationships

Validation supports the therapeutic alliance; it also develops and maintains positive relationships outside therapy, within the family, friendships, and the workplace (Rather & Miller, 2015).

When confronted by difficult conversations or criticism without validation, we can react with anger or by shutting down. When we feel unheard and misunderstood, communication can fall apart and even, when unresolved, lead to more permanent damage to relationships (Brown, 2015).

Validation has the power and potential to reduce misunderstandings and result in a more productive, less confrontational conversation, where unnecessarily harsh criticism is reduced or avoided altogether.

Resources From PositivePsychology.com

We have many worksheets that will help you improve understanding, empathy, communication, and emotional awareness.

Try out the following free resources with your clients and work on your (and their) validation techniques:

- Listening Accurately Worksheet

This handout presents five simple steps to facilitate accurate listening and can be used to help establish communication norms at the beginning of a therapeutic relationship.

- Assess Barriers to an Accepting Attitude

After therapy sessions, practitioners can use this worksheet to reflect on what thoughts and beliefs may have held them back from having a more accepting attitude toward their clients. - Walking In Their Shoes

Practitioners can use this worksheet to become aware of opportunities to empathize with their clients’ experiences more fully using an internal frame of reference. - Radical Acceptance

This worksheet can help clients recognize that they cannot control every aspect of their experience and invites them to choose mindful responses over emotionally reactive ones when faced with distressing events. - Emotion Regulation Worksheet for Adults

This worksheet helps clients explore their emotional reactions in response to situations and consider the downstream consequences of those emotional responses. - 17 Positive Communication Exercises

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others communicate better, this collection contains 17 validated positive communication tools for practitioners. Use them to help others improve their communication skills and form deeper and more positive relationships.

Use them to help others improve their communication skills and form deeper and more positive relationships.

A Take-Home Message

The process and outcome of validation are valuable in any relationship, yet crucial in therapy, promoting the therapeutic alliance that ultimately predicts treatment outcome.

Validation signifies to the other person that they are heard.

In therapy, the client feels acknowledged and understood and is being shown empathy (Kocabas & Üstündağ‐Budak, 2017).

Beyond promoting relationships, validation is also a valuable method for acknowledging what is said by the client, while encouraging early clarification of misunderstandings and inaccuracies. Furthermore, the therapist can use the techniques to deescalate difficult situations and give confidence to the client that they are not being judged and have valid fears, hopes, concerns, and anxieties (Rather & Miller, 2015).

Not all validation is equal. Any response from the therapist must be seen as positive and helpful, promoting growth and learning in the client, rather limiting or damaging.

When done well and with sensitivity, validation offers valuable support during difficult life events and confirms that emotions are acceptable and make sense.

While integral to DBT, validation is crucial to all listening therapies. The therapist and therapeutic process benefit from clear and transparent communication by acknowledging what the client says.

The worksheets included in this article provide a practical way to recognize the strengths and weaknesses of existing validation approaches. We can use them to highlight opportunities for growth and improvement, ultimately benefiting the therapist, client, and overall therapeutic outcome.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Relationships Exercises for free.

- American Psychological Association. (2020). APA dictionary of psychology. Retrieved August 16, 2021, from https://dictionary.apa.org/validation

- Brown, B. (2015). Daring greatly: How the courage to be vulnerable transforms the way we live, love, parent, and lead.

Avery.

Avery. - Carson-Wong, A., Hughes, C. D., & Rizvi, S. L. (2018). The effect of therapist use of validation strategies on change in client emotion in individual DBT treatment sessions. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 9(2), 165–171.

- Dietz, L. (n.d.). Validation examples. DBT Self Help. Retrieved August 16, 2021, from https://www.dbtselfhelp.com/html/validation_examples.html

- Eubanks, C. F., Burckell, L. A., & Goldfried, M. R. (2018). Clinical consensus strategies to repair ruptures in the therapeutic alliance. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 28(1), 60–76.

- Kocabas, E., & Üstündağ‐Budak, M. (2017). Validation skills in counselling and psychotherapy. International Journal of Scientific Study, 5(8), 319‐322.

- Linehan, M. M. (1997). Validation and psychotherapy. In A. C. Bohart & L. S. Greenberg (Eds.), Empathy reconsidered: New directions in psychotherapy (pp.

353–392). American Psychological Association.

353–392). American Psychological Association. - Linehan, M. M. (2015). DBT skills training handouts and worksheets. Guilford Press.

- Rather, J. H., & Miller, A. (2015). DBT skills manual for adolescents. Guilford Press.

- Tian, X., Solomon, D. H., & Brisini, K. S. C. (2020). How the comforting process fails: Psychological reactance to support messages. Journal of Communication, 70(1), 13–34.

- Validating statements. (n.d.). Epower & Associates. Retrieved August 16, 2021, from https://traumainformedcare.com/TIC_PDF/Validating_statements.pdf

CONFIRMATION | it's... What is CONFIRMATION?

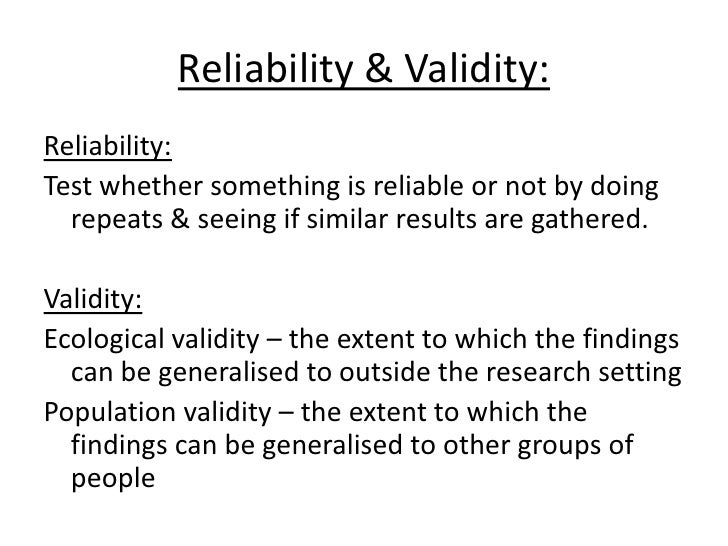

CONFIRMATION - the result of verification by empirical data (observations, measurements, experiments) of general statements (in particular, logical consequences from hypotheses). Confirmation of general judgments (scientific laws) cannot be final, since a finite set of experimental data cannot be compared with an infinite set of logical consequences from such judgments. Therefore, confirmation is considered in connection with establishing the degree of probability of scientific judgments, theories and hypotheses. nine/x[P(x) e Q(x)] is supported by the statement S that the object a is both P and β and refuted by the statement S' that a is P but not Q. For example, the observation of a black (Q) crow (F) confirms the “All crows are black” hypothesis. However, as shown by K. Hempel, such an understanding leads to “the paradox of confirmation: if the statement S confirms the statement T, then it also confirms any statement T', which is logically equivalent to T, and vice versa. Then, if T'= Yx(P(x) o β(χ)1, and T'= Yd•(CONFIRMATIONb(x) CONFIRMATION P(x)], then T' is confirmed by the observation of any non-black object (e.g., a white The paradox of confirmation is neither semantic nor syntactic; there is no formal-logical contradiction that the hypothesis of the blackness of all ravens is confirmed by the observation of a white shoe. But confirmation based on facts that have nothing to do with the original hypothesis cannot have With some modification, the “confirmation paradox” can be formulated in an even more “unnatural” form: the hypothesis is confirmed by the observation of any object in the universe, which deprives any hypothesis of value

Therefore, confirmation is considered in connection with establishing the degree of probability of scientific judgments, theories and hypotheses. nine/x[P(x) e Q(x)] is supported by the statement S that the object a is both P and β and refuted by the statement S' that a is P but not Q. For example, the observation of a black (Q) crow (F) confirms the “All crows are black” hypothesis. However, as shown by K. Hempel, such an understanding leads to “the paradox of confirmation: if the statement S confirms the statement T, then it also confirms any statement T', which is logically equivalent to T, and vice versa. Then, if T'= Yx(P(x) o β(χ)1, and T'= Yd•(CONFIRMATIONb(x) CONFIRMATION P(x)], then T' is confirmed by the observation of any non-black object (e.g., a white The paradox of confirmation is neither semantic nor syntactic; there is no formal-logical contradiction that the hypothesis of the blackness of all ravens is confirmed by the observation of a white shoe. But confirmation based on facts that have nothing to do with the original hypothesis cannot have With some modification, the “confirmation paradox” can be formulated in an even more “unnatural” form: the hypothesis is confirmed by the observation of any object in the universe, which deprives any hypothesis of value

K. Hempel formulated the logical conditions that any adequate definition of confirmation must satisfy: 1) any statement that follows from the description of the observation is confirmed by this description; 2) if the description of the observation confirms the hypothesis H, then it confirms any consequence of H and any hypothesis Η ι that is logically equivalent to H; 3) any consistent description of an observation is logically compatible with the class of all hypotheses that it confirms. The fulfillment of these conditions is necessary, but not sufficient: the definition of confirmation “should provide a rational approximation to the concept of confirmation, which is implicitly present in scientific practice and methodological discussions” (Gempel K. Logic of explanation. M., 1998, p. 73). For languages of scientific theories that are sufficiently simple in their logical structure, an exact definition of confirmation can be formulated using the satisfiability criterion: a hypothesis is confirmed by some description of an observation if it is true for a finite class of objects referred to in the description of the observation.

Hempel formulated the logical conditions that any adequate definition of confirmation must satisfy: 1) any statement that follows from the description of the observation is confirmed by this description; 2) if the description of the observation confirms the hypothesis H, then it confirms any consequence of H and any hypothesis Η ι that is logically equivalent to H; 3) any consistent description of an observation is logically compatible with the class of all hypotheses that it confirms. The fulfillment of these conditions is necessary, but not sufficient: the definition of confirmation “should provide a rational approximation to the concept of confirmation, which is implicitly present in scientific practice and methodological discussions” (Gempel K. Logic of explanation. M., 1998, p. 73). For languages of scientific theories that are sufficiently simple in their logical structure, an exact definition of confirmation can be formulated using the satisfiability criterion: a hypothesis is confirmed by some description of an observation if it is true for a finite class of objects referred to in the description of the observation. This definition applies to any hypothesis that can be formulated in terms of “observational language” using standard quantifier logic. However, its application to theoretical statements is limited due to the practical irreducibility of “theoretical terms” to “observation terms”. nine0003

This definition applies to any hypothesis that can be formulated in terms of “observational language” using standard quantifier logic. However, its application to theoretical statements is limited due to the practical irreducibility of “theoretical terms” to “observation terms”. nine0003

Modern research on inductive logic outlines ways to increase the cognitive value of the confirmation relation. To do this, we had to abandon the idea of constructing inductive logic as an analytical theory, “true in all possible worlds”, and go over to certain restrictions, due to which the logical conclusion in inductive logic becomes dependent on the empirical factor, i.e., on the specific properties of the “given world” (R. Karnap, J. Hintikka) and even from the researcher’s goals. nine0003

Lit.: Pyatnitsyn?. N. Philosophical problems of probabilistic and statistical methods. M., 1976; Reichenbach H. Experience and prediction. Chi.—L., 1961; Carnap R. The continuum of Inductive Methods. Chi. , 1952; Idem. Introduction to Semantics. Cambr. (Mass.), 1962; NicodJ. Foundations of Geometry and Induction. L., 1930; HempelC. Confirmation, Qualitative Aspects.—The Encyclopedia of Philosophy, v. 2. N. Y, 1967.

, 1952; Idem. Introduction to Semantics. Cambr. (Mass.), 1962; NicodJ. Foundations of Geometry and Induction. L., 1930; HempelC. Confirmation, Qualitative Aspects.—The Encyclopedia of Philosophy, v. 2. N. Y, 1967.

V.N. Poru

New Philosophical Encyclopedia: In 4 vols. M.: Thought. Edited by V. S. Stepin. 2001. nine0016

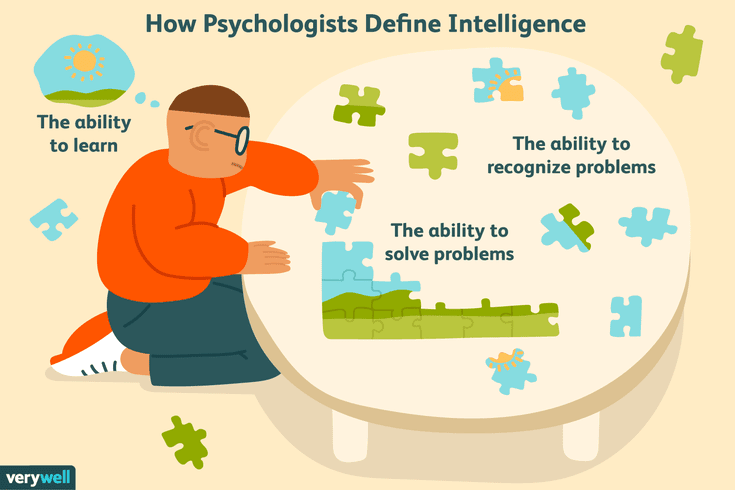

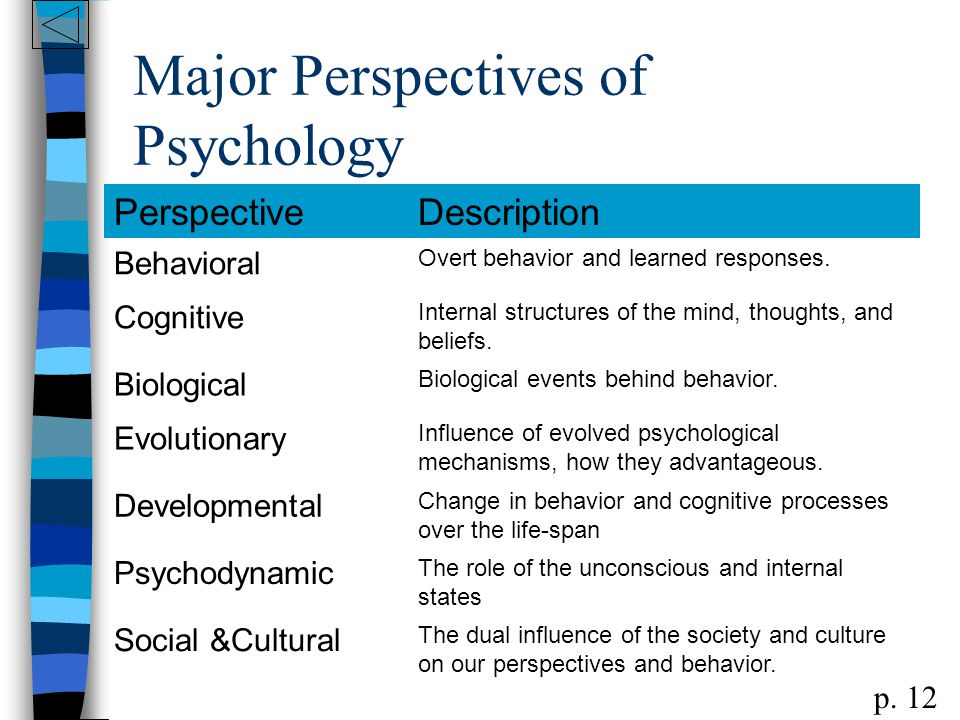

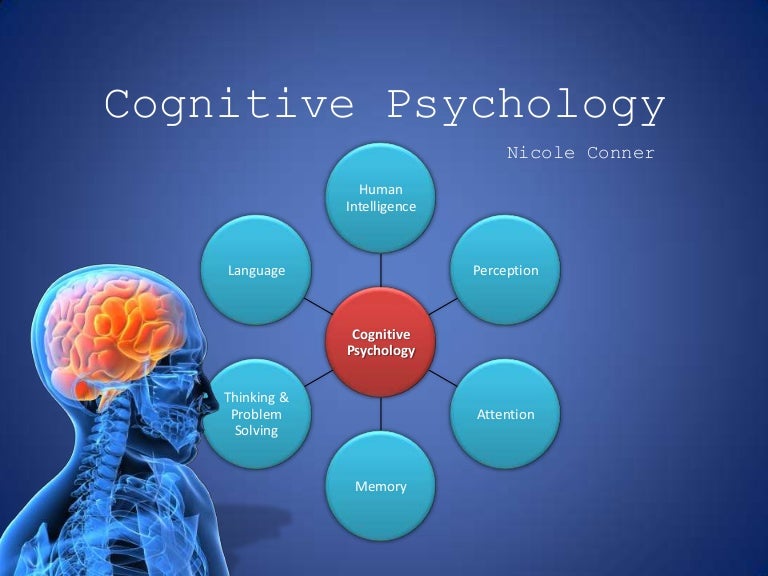

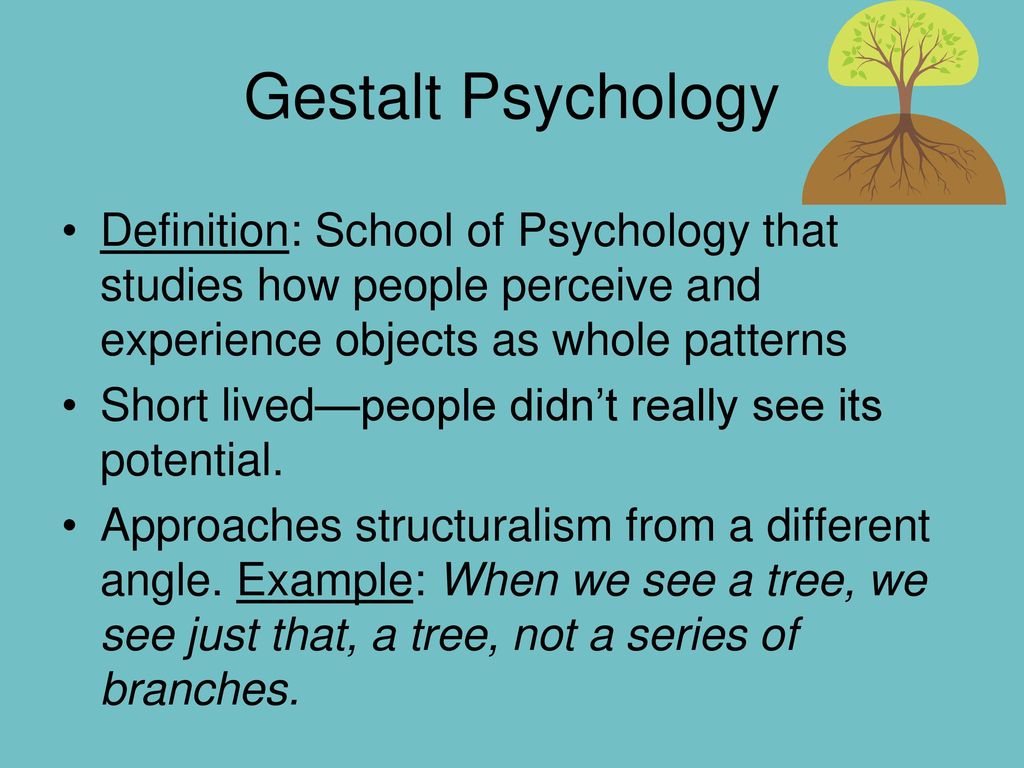

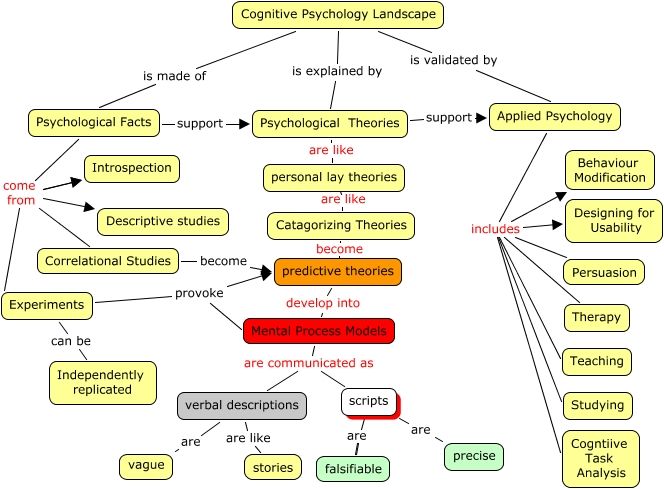

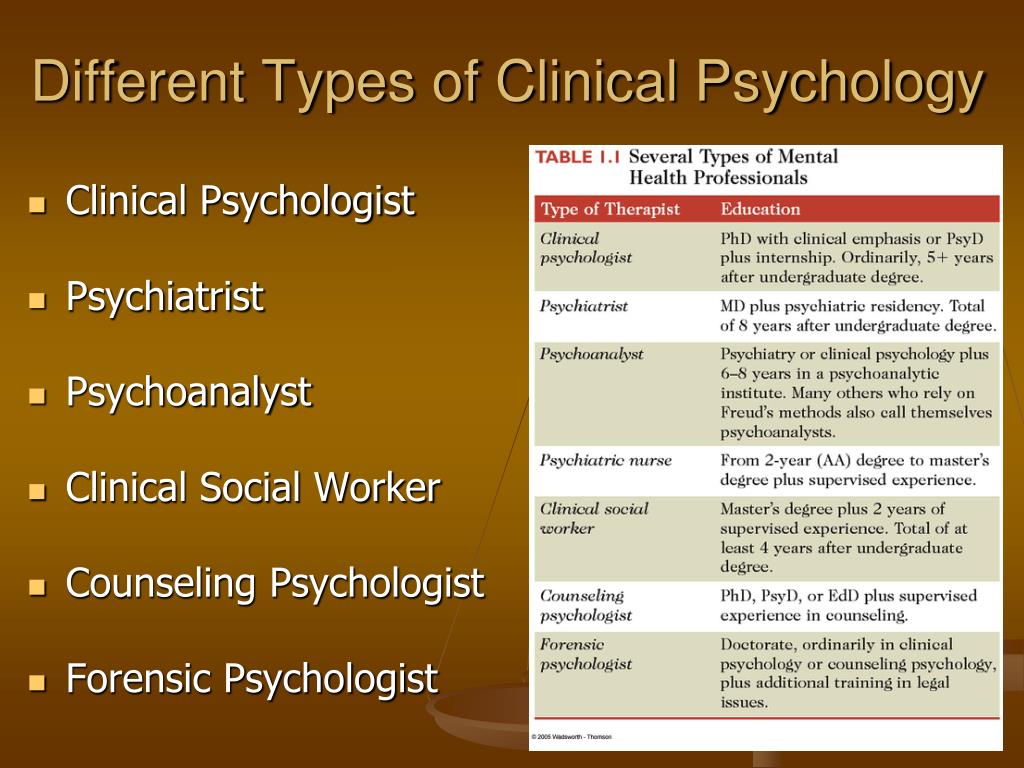

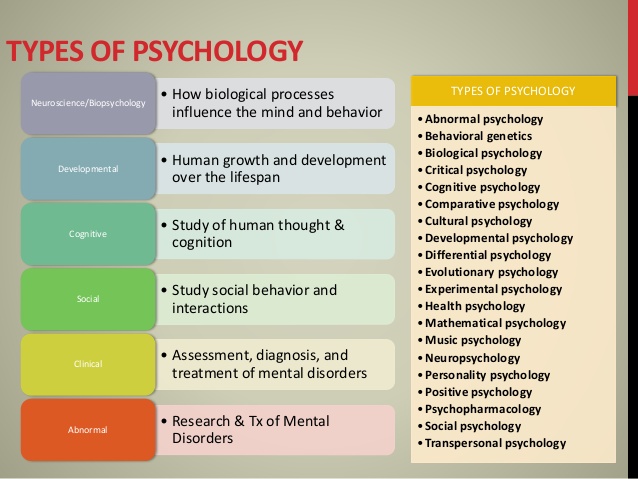

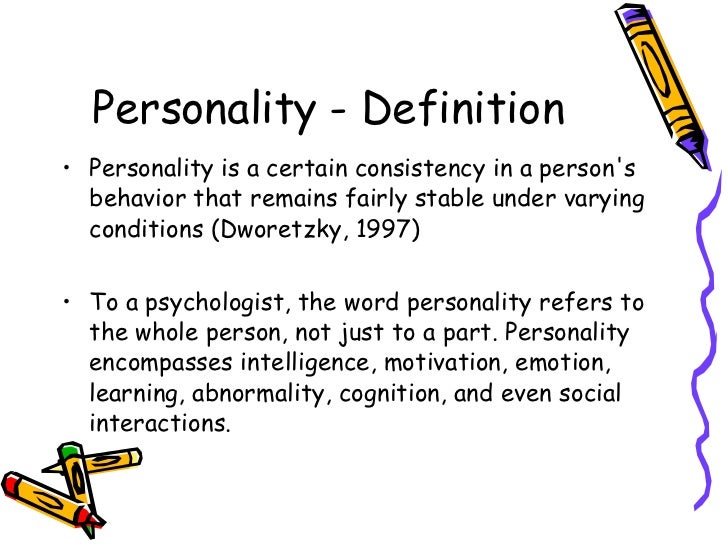

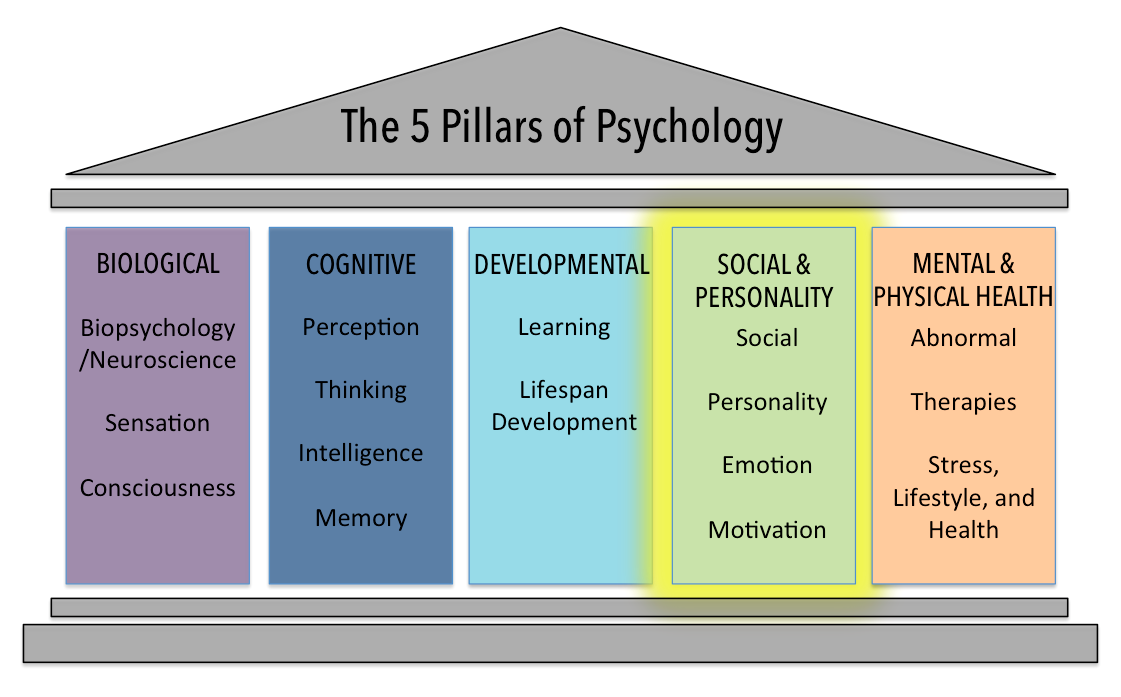

1. Definition of psychology as a science

Many people are interested in what is psychology, what is simple and clear definition of psychology. But definitions of psychology exist set, so give monosyllabic definition of psychology impossible. The simplest definition psychology as a science is: Psychology is the science of the human soul. After all, "pshyso" in Greek means “soul”, and “logia” - “science, teaching”. Standard Definition of Psychology as sciences from the psychologists themselves: Psychology - this is the science of regularities development and functioning of mental human activitiesKey concept in the study of psychology is the concept the human psyche. For the knowledge of the psyche people scientists have studied and are researching animal behavior and systems artificially established institutions, such as schools or organizations. The psychologist is a specialist in the field of practical, applied psychology (for example, legal, pedagogical, medical psychology), whose main task is to provide people timely psychological help to alleviate their mental suffering and point in the right direction life. With regard to industries and types psychology as a science and as a social phenomena, there are a lot of them: a common psychology, personality psychology, psychology collective, public, social psychology, popular psychology pop psychology, child psychology child and children, psychology of parents, educational psychology and psychology punishment, integral psychology, idealistic psychology. Target psychology as a science is to give an answer when asked why a particular person behaves in a given situation and not otherwise, and what can be done to change that person's behavior or his attitude towards what he does or does not.

For the knowledge of the psyche people scientists have studied and are researching animal behavior and systems artificially established institutions, such as schools or organizations. The psychologist is a specialist in the field of practical, applied psychology (for example, legal, pedagogical, medical psychology), whose main task is to provide people timely psychological help to alleviate their mental suffering and point in the right direction life. With regard to industries and types psychology as a science and as a social phenomena, there are a lot of them: a common psychology, personality psychology, psychology collective, public, social psychology, popular psychology pop psychology, child psychology child and children, psychology of parents, educational psychology and psychology punishment, integral psychology, idealistic psychology. Target psychology as a science is to give an answer when asked why a particular person behaves in a given situation and not otherwise, and what can be done to change that person's behavior or his attitude towards what he does or does not. nine0003

nine0003

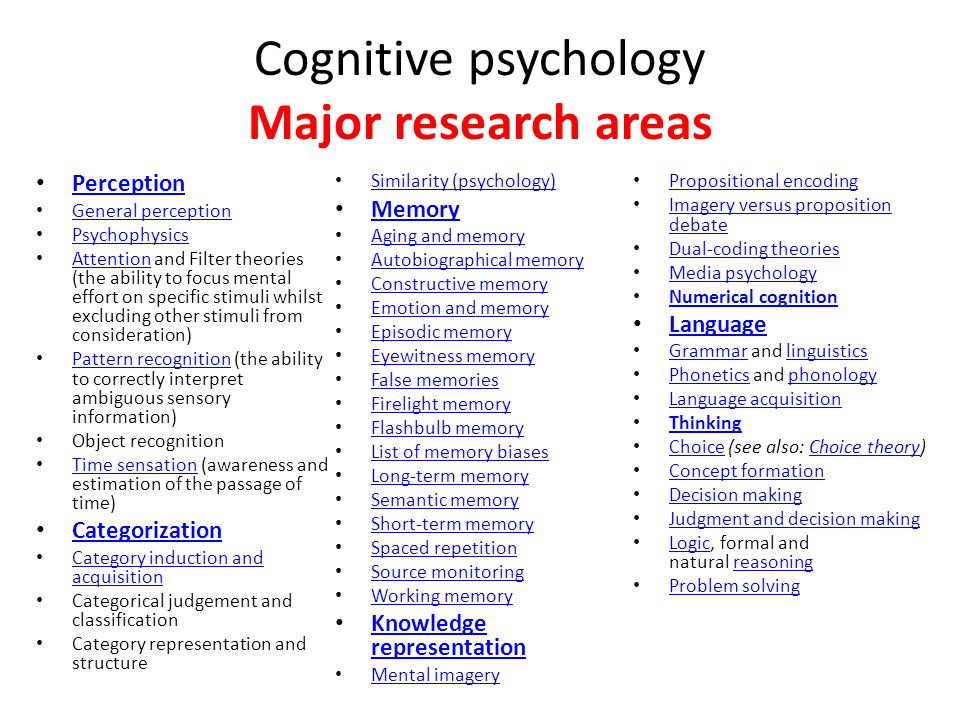

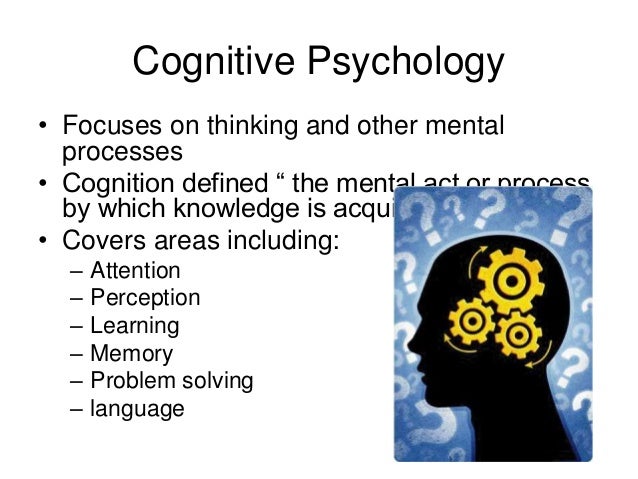

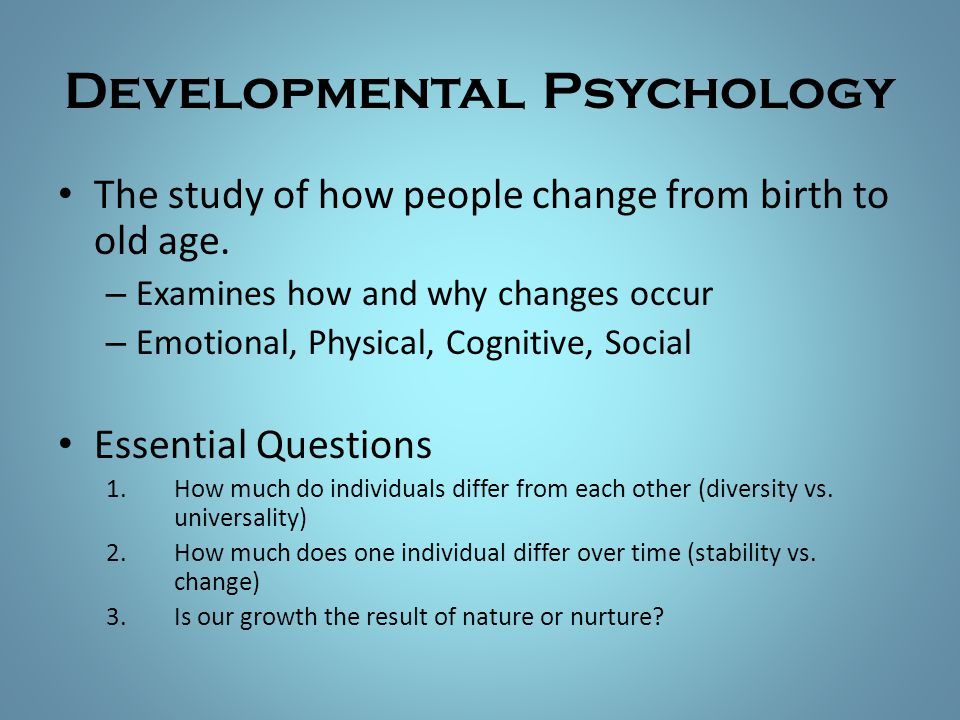

2. Main phenomena studied by modern psychology

Subject studying psychology in the first place is the psyche of man and animals, including many subjective phenomena. With the help of some such, for example, as sensations and perceptions, attention and memory, imagination, thinking and speech, man knows the world. Therefore, they are often called learning processes. Other phenomena govern his communication with people directly manage actions and deeds. They are called mental properties and states personalities include needs, motives, goals, interests, will, feelings and emotions, inclinations and abilities, knowledge and consciousness. In addition, psychology studies human communication and behavior, their dependence on mental phenomena and, in turn, the dependence of the formation and the development of mental phenomena from them. nine0003

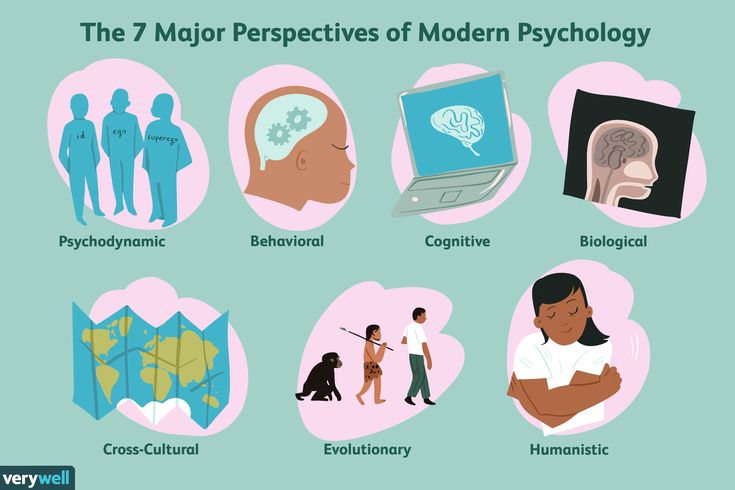

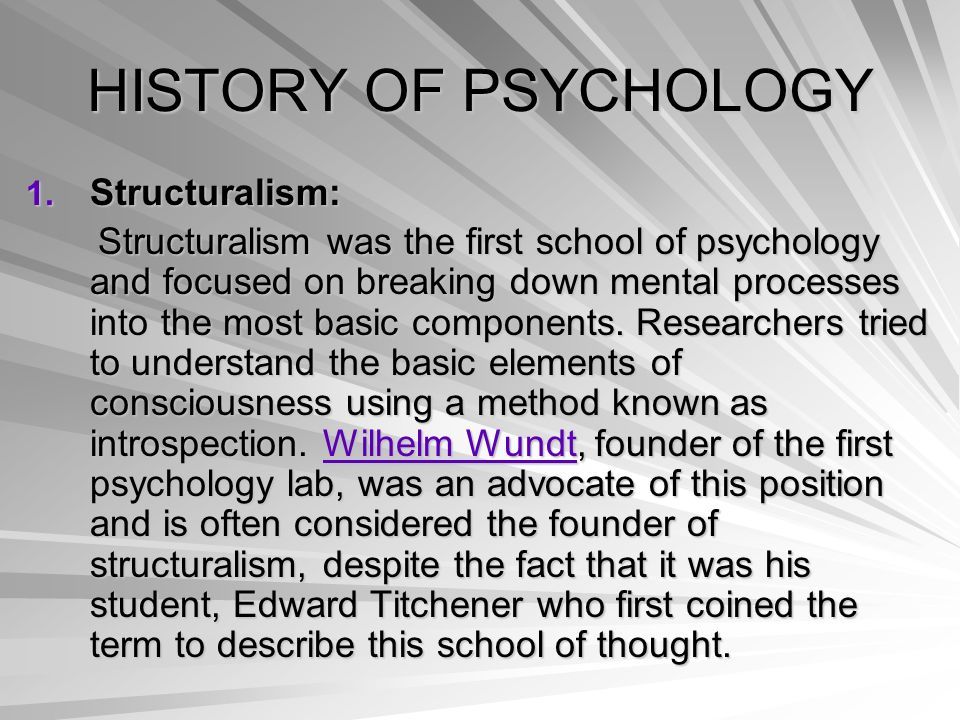

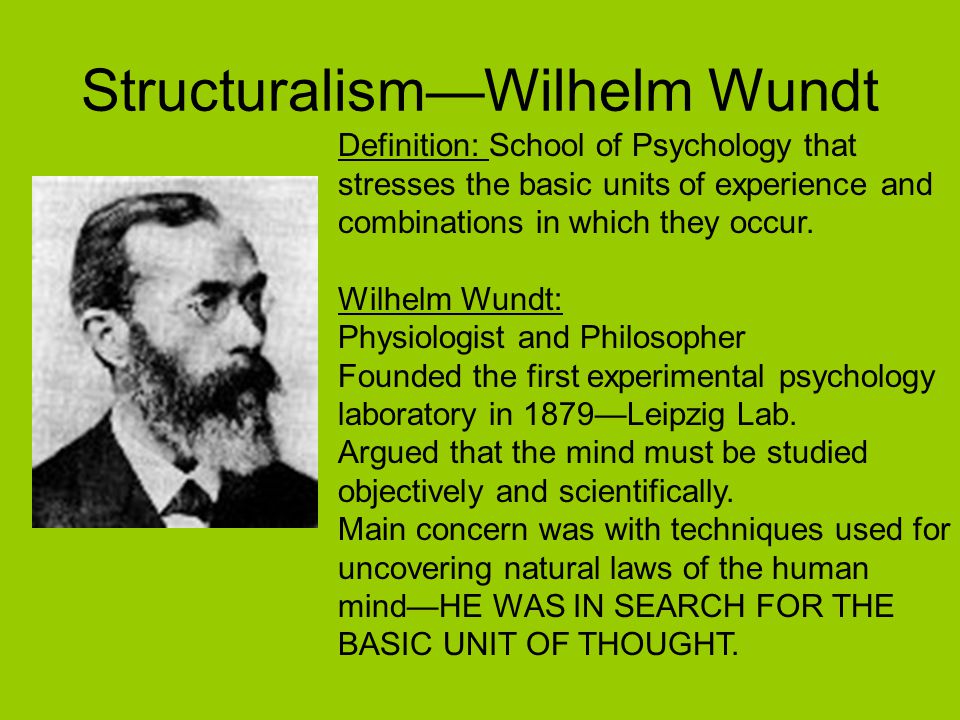

3. Formation of psychology as a science

History development of psychology as a science, is a sequence events and philosophical discoveries that led to the formation of psychology independent science, as well as determined main directions of psychology. Development psychological knowledge is studied by such science as the history of psychology, basic directions of psychology are described in the general psychology. Therefore, by contacting to the history of psychology, one can consider How did philosophical thought develop? served as the basis for the emergence and development of psychological knowledge and main directions of psychology. Conditionally development of psychology as a science divided into two main steps: one. The period of formation of psychology within other scientific disciplines (IV-V centuries BC - 60s of the XIX century) when the development took place ideas about the soul within the framework of religious systems and rituals, the development of teachings about soul, experience and knowledge (pre-paradigm period) 2. The formation of psychology as an independent scientific discipline (60s of the XIX century. - present time). AT conditions of modern reality there is hardly any question of whether whether psychological knowledge for life human society and successful existence and development of personality.

Development psychological knowledge is studied by such science as the history of psychology, basic directions of psychology are described in the general psychology. Therefore, by contacting to the history of psychology, one can consider How did philosophical thought develop? served as the basis for the emergence and development of psychological knowledge and main directions of psychology. Conditionally development of psychology as a science divided into two main steps: one. The period of formation of psychology within other scientific disciplines (IV-V centuries BC - 60s of the XIX century) when the development took place ideas about the soul within the framework of religious systems and rituals, the development of teachings about soul, experience and knowledge (pre-paradigm period) 2. The formation of psychology as an independent scientific discipline (60s of the XIX century. - present time). AT conditions of modern reality there is hardly any question of whether whether psychological knowledge for life human society and successful existence and development of personality.