Vaccines causing autism proof

Discussing Vaccines and Autism | Southwest Autism Research & Resource Center (SARRC)

Do Vaccines Cause Autism?

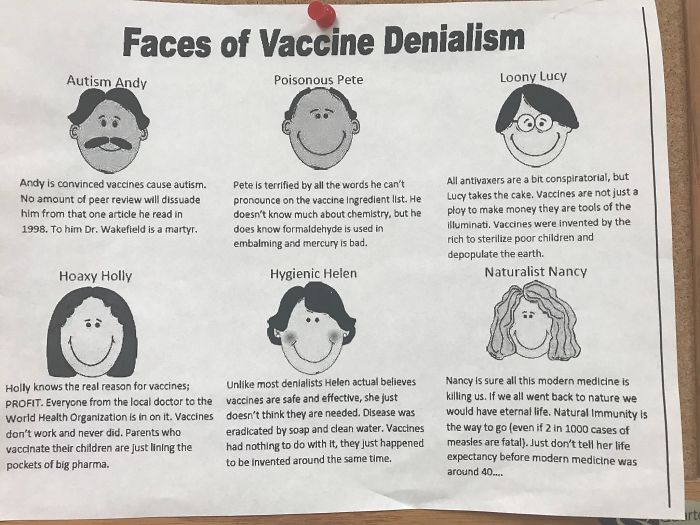

Some parents of children with ASD wonder whether a link exists between autism and vaccines. The concern first started with the MMR vaccine, an immunization against measles, mumps, and rubella. Some parents believe this vaccine causes the onset of autism. Despite these strongly held beliefs by proponents of the vaccine theory, there is no scientific proof that the MMR vaccine—or any other vaccine—causes autism.

Correlation in Time

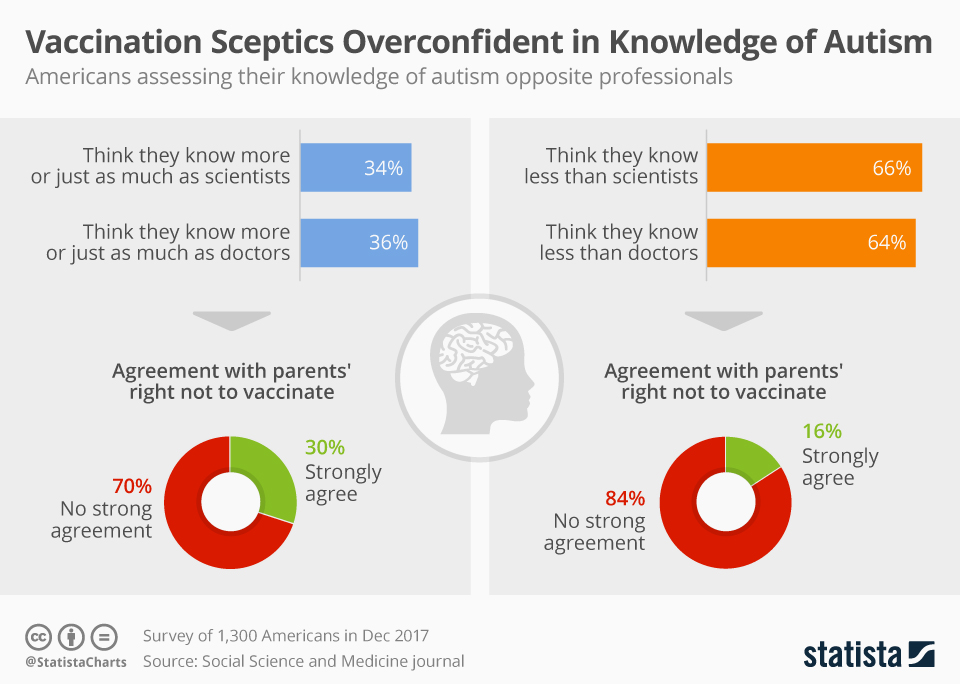

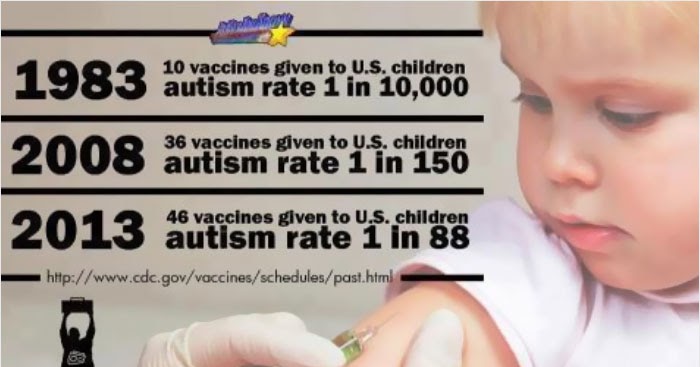

What does exist is a correlation in time between when children are immunized and when they are diagnosed with autism. In other words, children are vaccinated at various times throughout early childhood. ASD is also often diagnosed during early childhood. Just because two events like these happen around the same time does not mean that one causes the other ("correlation does not equal causation"). Media reports, activist groups, and even some respected medical professionals (turned authors) can scare people with more subjective evidence into believing vaccines cause autism.

Research Supports Vaccinating

The onset of autism in a child likely occurs long before developmental delays or behaviors emerge, quite possibly before a child is born. For many children, signs of ASD exist from birth and their development is never typical. A smaller percentage of children seem to develop typically. Then, usually between ages 1 and 2, they regress (or appear to lose skills). Children who experience this regression present the most puzzling evidence for a vaccine-autism link. Researchers have investigated the link in these children specifically but still no evidence for a link between autism and vaccines was found.

Relative to the total number of people with ASD, very few parents actually report a dramatic loss of skills associated with a specific vaccination. However, parents who choose not to vaccinate their child (hoping to protect against autism) expose their child to other health concerns. And unfortunately, some of these unvaccinated children develop ASD anyway. Because professionals cannot provide parents a definitive explanation for the onset of autism in their child, any parent questioning the role of vaccines is understandable, but science does not support a link.

Because professionals cannot provide parents a definitive explanation for the onset of autism in their child, any parent questioning the role of vaccines is understandable, but science does not support a link.

SARRC's Message on Vaccines

At SARRC, we believe the ultimate decision to vaccinate a child is a personal choice. If asked, we would recommend vaccinations because dozens of reputable scientific studies have failed to show a link between vaccines and autism, while numerous other studies demonstrate that the risks from the diseases the vaccines are meant to prevent are dangerous to a child’s health and well-being. Our research focuses on early identification of autism because it leads to early intensive intervention, which is the most important support we can provide for a child diagnosed with autism at this time.

Read more about autism and vaccines in a Q&A with SARRC's Vice President and Research Director Christopher J. Smith, PhD, here.

MMR vaccines and autism

- All topics »

- A

- B

- C

- D

- E

- F

- G

- H

- I

- J

- K

- L

- M

- N

- O

- P

- Q

- R

- S

- T

- U

- V

- W

- X

- Y

- Z

- Resources »

- Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Multimedia

- Publications

- Questions & answers

- Tools and toolkits

- Popular »

- Air pollution

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Hepatitis

- Monkeypox

- All countries »

- A

- B

- C

- D

- E

- F

- G

- H

- I

- J

- K

- L

- M

- N

- O

- P

- Q

- R

- S

- T

- U

- V

- W

- X

- Y

- Z

- Regions »

- Africa

- Americas

- South-East Asia

- Europe

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Western Pacific

- WHO in countries »

- Statistics

- Cooperation strategies

- Ukraine emergency

- All news »

- News releases

- Statements

- Campaigns

- Commentaries

- Events

- Feature stories

- Speeches

- Spotlights

- Newsletters

- Photo library

- Media distribution list

- Headlines »

- Focus on »

- Afghanistan crisis

- COVID-19 pandemic

- Northern Ethiopia crisis

- Syria crisis

- Ukraine emergency

- Monkeypox outbreak

- Greater Horn of Africa crisis

- Latest »

- Disease Outbreak News

- Travel advice

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- WHO in emergencies »

- Surveillance

- Research

- Funding

- Partners

- Operations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- WHO's Health Emergency Appeal 2023

- Data at WHO »

- Global Health Estimates

- Health SDGs

- Mortality Database

- Data collections

- Dashboards »

- COVID-19 Dashboard

- Triple Billion Dashboard

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Highlights »

- Global Health Observatory

- SCORE

- Insights and visualizations

- Data collection tools

- Reports »

- World Health Statistics 2022

- COVID excess deaths

- DDI IN FOCUS: 2022

- About WHO »

- People

- Teams

- Structure

- Partnerships and collaboration

- Collaborating centres

- Networks, committees and advisory groups

- Transformation

- Our Work »

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Activities

- Initiatives

- Funding »

- Investment case

- WHO Foundation

- Accountability »

- Audit

- Programme Budget

- Financial statements

- Programme Budget Portal

- Results Report

- Governance »

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Election of Director-General

- Governing Bodies website

- Member States Portal

Extract from report of GACVS meeting of 16-17 December 2002, published in the WHO Weekly Epidemiological Record on 24 January 2003

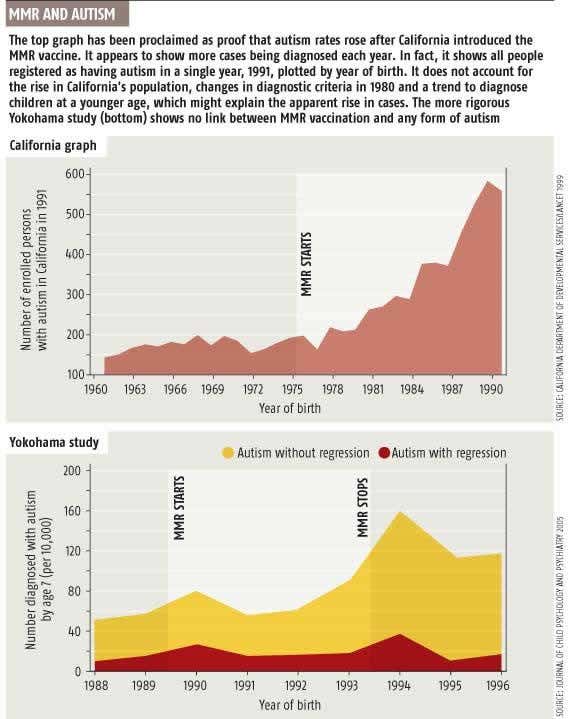

Concerns about a possible link between vaccination with MMR and autism were raised in the late 1990s, following publication of studies claiming an association between natural and vaccine strains of measles virus and inflammatory bowel diseases, and separately, MMR vaccine, bowel disease and autism. WHO, on the recommendation of GACVS, commissioned a literature review by an independent researcher of the risk of autism associated with MMR vaccine; the outcome of the review was presented to GACVS for its consideration.

WHO, on the recommendation of GACVS, commissioned a literature review by an independent researcher of the risk of autism associated with MMR vaccine; the outcome of the review was presented to GACVS for its consideration.

Autistic spectrum disorder represents a continuum of cognitive and neurobehavioral disorders including autism. The prevalence of autism varies considerably with case ascertainment, ranging from 0.7 – 21.1 per 10 000 children (median 5.2 per 10 000) while the prevalence of autistic spectrum disorder is estimated to be 1 - 6 per 1000. Eleven epidemiological studies (representing the most recent studies, mostly in the last 4 years) were reviewed in detail, taking into consideration study design (including ecologic, case control, case-crossover and cohort studies) and limitations. The review concluded that existing studies do not show evidence of an association between the risk of autism or autistic disorders and MMR vaccine. Three laboratory studies were also reviewed. It was concluded that the alleged persistence of measles vaccine virus in the gastrointestinal tract of children with autism and inflammatory bowel disease requires further investigation through independent studies before the laboratory findings of the published studies, which have serious limitations, can be considered confirmed.

It was concluded that the alleged persistence of measles vaccine virus in the gastrointestinal tract of children with autism and inflammatory bowel disease requires further investigation through independent studies before the laboratory findings of the published studies, which have serious limitations, can be considered confirmed.

Based on the extensive review presented, GACVS concluded that no evidence exists of a causal association between MMR vaccine and autism or autistic disorders. The Committee believes the matter is likely to be clarified by a better understanding of the causes of autism. GACVS also concluded that there is no evidence to support the routine use of monovalent measles, mumps and rubella vaccines over the combined vaccine, a strategy which would put children at increased risk of incomplete immunization. Thus, GACVS recommends that there should be no change in current vaccination practices with MMR.

Full report of GACVS meeting of 16-17 December 2002, published in the WHO Weekly Epidemiological Record on 24 January 2003

"Vaccinations Cause Autism" Asya Kazantseva debunks myths in her book "Someone Is Wrong on the Internet!".

Facts and myths.

Facts and myths. In February, Corpus publishing house publishes a book by science journalist Asya Kazantseva, laureate of the Enlightener award — “Someone is wrong on the Internet! Scientific studies of controversial issues. The book is published with the support of the Evolution Foundation. In it, the author debunks a dozen myths and explains how to learn how to analyze information in order to figure out whether this or that statement is true. Meduza publishes a fragment of the second chapter of the book.

"Vaccines cause autism"

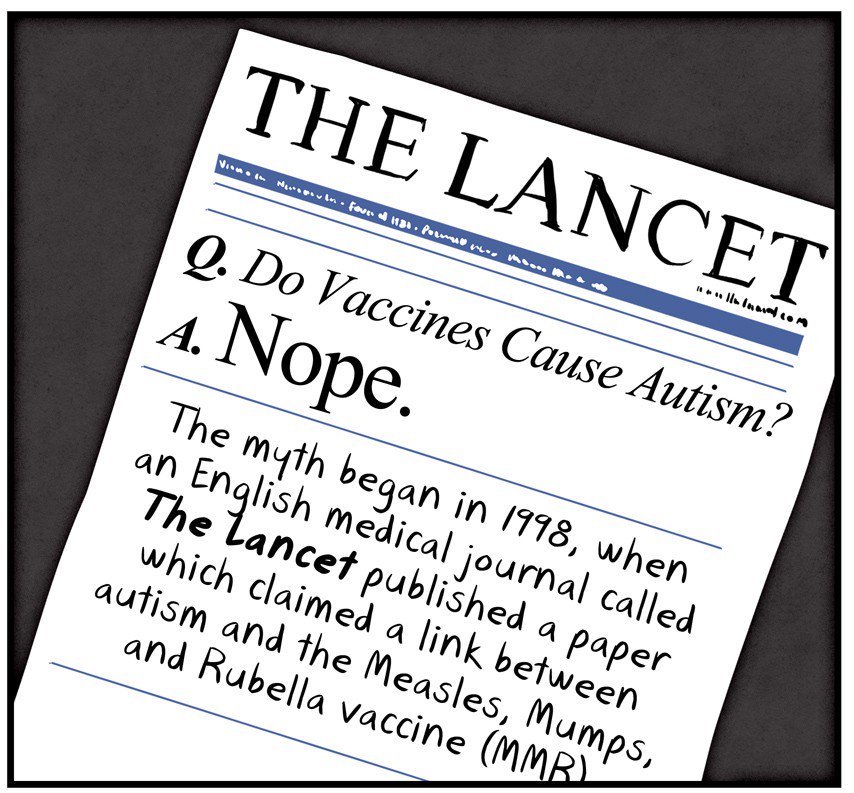

Apparently not. This myth comes from a single scientific publication that was subsequently withdrawn from the journal because the author was found to have manipulated the data.

The boy, known to the public as "Patient 11", appeared to be quite healthy until he was a year and a month old. At this age, alarming symptoms began to appear. When trying to speak, the child uttered all the syllables very slowly, stretching out the sounds. He demonstrated stereotyped, repetitive hand movements. The child's condition gradually worsened, and by the age of one and a half it became clear that we were talking about autism.

He demonstrated stereotyped, repetitive hand movements. The child's condition gradually worsened, and by the age of one and a half it became clear that we were talking about autism.

Another child, "patient 2", developed like all children up to one year and nine months. But then he started screaming at night and banging his head against the crib. Later, he was also diagnosed with autism.

Both children aged one and three months were vaccinated against measles, rubella and mumps. Both, along with ten other children, were the subjects of Andrew Wakefield's famous study on the link between vaccines and autism, published in 1998 in the renowned medical journal The Lancet.

A few years later, medical journalist Brian Dear noticed one small detail: Wakefield's article indicated that the first signs of autism appeared in patient 11 a week after vaccination (instead of two months before it), in patient 2 two months later. weeks (rather than six months). This was in stark contrast to the parents Deer interviewed. Patient 2's mother subsequently explained this discrepancy by saying that Deer pressured her and demanded a clear answer about the time of onset of the disease, like a tabloid press representative, and she was confused. Patient 11's dad said, "If Wakefield's article really describes my son's case, then it is a clear fabrication."

Patient 2's mother subsequently explained this discrepancy by saying that Deer pressured her and demanded a clear answer about the time of onset of the disease, like a tabloid press representative, and she was confused. Patient 11's dad said, "If Wakefield's article really describes my son's case, then it is a clear fabrication."

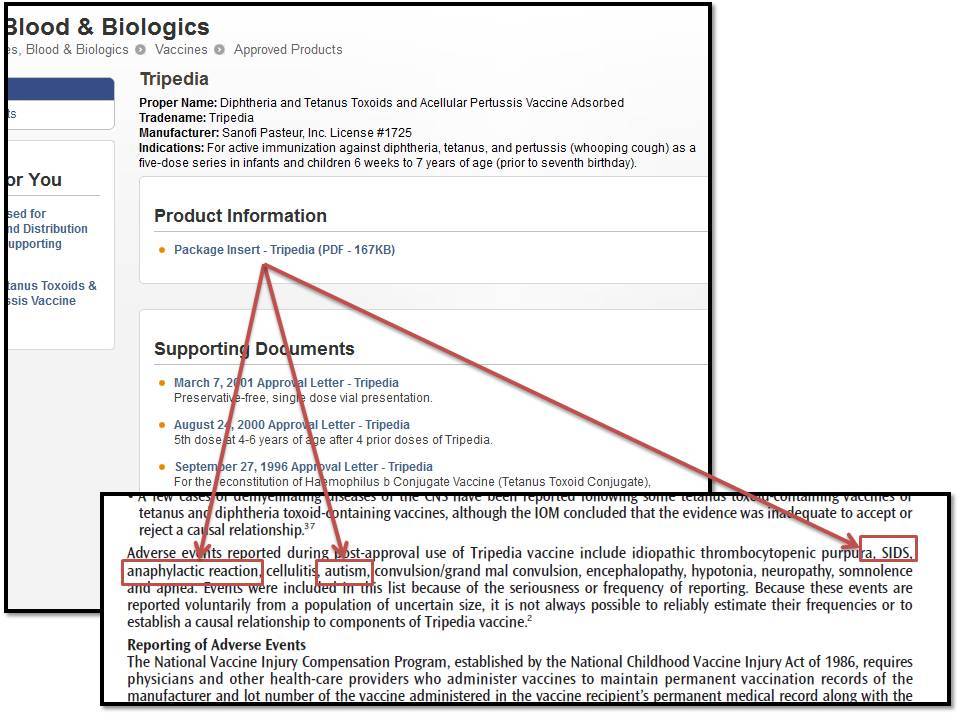

A perplexed Brian Dear got the British General Medical Council to request medical records for all the children in Wakefield's study. There really were a lot of inconsistencies. Wakefield claimed that the children he studied suffered from regressive autism (with the loss of achieved skills), but this diagnosis was confirmed for only one boy. Wakefield's hypothesis was that the weakened measles virus contained in the vaccine settles in the cells of the intestine and causes inflammation, and then leads to symptoms of autism - but at least some of the children who did have intestinal problems suffered from them even before they received the measles vaccine. To detect colitis, Dr. Wakefield performed colonoscopies on many children - a very unpleasant procedure - without any clear medical indications, which raised serious questions about the ethics of the study. In addition, it was found that patients were recruited through acquaintances, mainly among opponents of vaccinations.

To detect colitis, Dr. Wakefield performed colonoscopies on many children - a very unpleasant procedure - without any clear medical indications, which raised serious questions about the ethics of the study. In addition, it was found that patients were recruited through acquaintances, mainly among opponents of vaccinations.

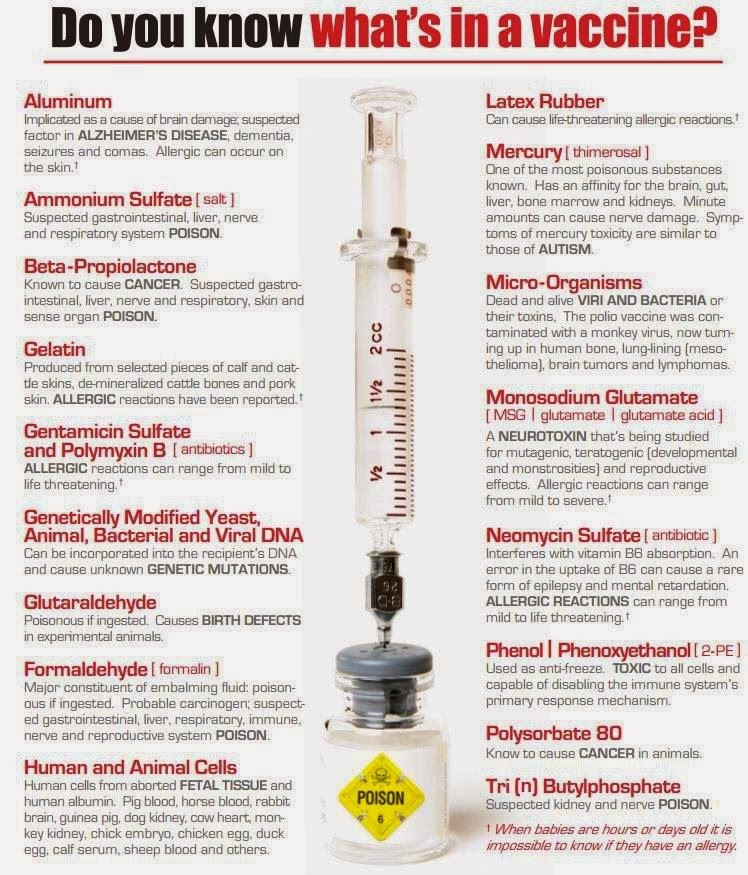

The idea that autism is not caused by a virus but by a mercury-based preservative (merthiolate, aka thiomersal) seems to have originated independently of Wakefield. According to current scientific understanding, doses of the preservative contained in vaccines are harmless, including not increasing the likelihood of developing autism, but out of sympathy for the worried public, many manufacturers have excluded it from vaccines anyway.

In general, even assuming that Wakefield's study was not a deliberate falsification, it is obvious that the work was carried out extremely sloppy and the data supposedly supporting Wakefield's hypothesis about the connection between vaccinations, intestinal disorders and autism are literally far-fetched. Why would the doctor risk his reputation so much? While Wakefield was still at the height of his fame and giving interviews left and right about his research, he emphasized that he did not think children should be vaccinated against measles, rubella and mumps at the same time; separate vaccines must be used. It was not difficult for Brian Dear to find out that Andrew Wakefield had just patented one such measles vaccine - a little less than a year before he discovered the dire danger of a complex vaccine. There were a number of other interesting circumstances, such as Wakefield colluding with a company that was going to sue vaccine manufacturers.

Why would the doctor risk his reputation so much? While Wakefield was still at the height of his fame and giving interviews left and right about his research, he emphasized that he did not think children should be vaccinated against measles, rubella and mumps at the same time; separate vaccines must be used. It was not difficult for Brian Dear to find out that Andrew Wakefield had just patented one such measles vaccine - a little less than a year before he discovered the dire danger of a complex vaccine. There were a number of other interesting circumstances, such as Wakefield colluding with a company that was going to sue vaccine manufacturers.

After analyzing the totality of the established facts, the editors of The Lancet decided to withdraw Wakefield's article (it can still be found on the Internet, but every page is crossed out with a bright red RETRACTED inscription), and the British General Medical Council deprived Wakefield of the right to practice medicine.

Twelve carefully selected children are not enough to find out whether circumstance X causes consequence Y. Even if they all really, without falsifications, developed autism after vaccination, you can just as well find twelve children who developed it after they first tasted zucchini; stayed overnight at grandma's; visited Disneyland. Research on large samples is important - and in the case of vaccination, as you might guess, there is no shortage of them, because there are many vaccinated children (and unvaccinated, unfortunately, too).

Even if they all really, without falsifications, developed autism after vaccination, you can just as well find twelve children who developed it after they first tasted zucchini; stayed overnight at grandma's; visited Disneyland. Research on large samples is important - and in the case of vaccination, as you might guess, there is no shortage of them, because there are many vaccinated children (and unvaccinated, unfortunately, too).

In Denmark, every person has a personal identification number, like our TIN, but medical information is also tied to it, including data on vaccinations and diagnoses.

This circumstance made it possible to analyze the state of health of all children born between January 1, 1991 and December 31, 1998 - a total of 537,303 of them, of which 440,655 were vaccinated against measles, rubella and mumps, and 96,648 for one reason or another, they were not vaccinated. In the first group, autism was diagnosed in 269children, and in the second group - 47. According to rough estimates, it turns out that 0.06% of children in the vaccinated group and 0.05% in the unvaccinated group develop autism - generally speaking, this is much more like a statistical error than a strict causal - follow-up relationship. But the authors of the work used more complex calculation algorithms, they were interested in such an indicator as person-years, the number of years included in the observation, and, in addition, they adjusted for the sex of children, their birth weight and a number of other factors that, according to statistics may have an impact on the likelihood of developing autism. With this calculation, it turned out that the chances of getting autism for a vaccinated child are even lower than for an unvaccinated one, although the level of discrepancy between the numbers is about the same, statistically unreliable. Unfortunately, based on the results of this study, we cannot say “Measles vaccination protects against autism!” — but anti-vaccinators cannot say that measles vaccination causes it.

According to rough estimates, it turns out that 0.06% of children in the vaccinated group and 0.05% in the unvaccinated group develop autism - generally speaking, this is much more like a statistical error than a strict causal - follow-up relationship. But the authors of the work used more complex calculation algorithms, they were interested in such an indicator as person-years, the number of years included in the observation, and, in addition, they adjusted for the sex of children, their birth weight and a number of other factors that, according to statistics may have an impact on the likelihood of developing autism. With this calculation, it turned out that the chances of getting autism for a vaccinated child are even lower than for an unvaccinated one, although the level of discrepancy between the numbers is about the same, statistically unreliable. Unfortunately, based on the results of this study, we cannot say “Measles vaccination protects against autism!” — but anti-vaccinators cannot say that measles vaccination causes it.

These figures illustrate well why large samples are important. No matter how we twist them and count them, we will not be able to pull out a statistically significant difference from there if it is not there - neither in one nor in the other direction. But if we took from the entire population, for example, only 50 vaccinated, among whom there would be two people with autism by chance, and only 50 unvaccinated, among whom there would be four people with autism, the results would be much more interesting.

A similar large-scale study with similar conclusions was also carried out in Finland, but I did not refer to it: the work states that it is supported by the pharmaceutical company Merck, and this fact, of course, entails suspicions of bias. And in general, whenever possible, it is always better to refer not to individual studies, but to meta-analyses that summarize the results of the work of several independent groups. Another large meta-analysis on the search for a link between autism and vaccination against measles, rubella and mumps was published in the summer of 2014. It included five large cohort studies (which compare the risk of developing the disease in large groups of children, in this case vaccinated and unvaccinated) and five case-control studies (here the focus is on children who have already developed autism, and scientists are investigating what vaccinations they received and whether these circumstances may be related). A total of 1,266,327 children were analyzed, and the authors confidently state that there is no link between vaccination and autism spectrum disorders. At the end there is a touching lyrical digression: “I am an epidemiologist, and I consider our findings reliable,” writes one of the authors. “At the same time, as a father of three children, I understand the fears associated with vaccination. My first two children had febrile seizures due to routine vaccinations. But this did not become a reason for me to refuse to vaccinate a third child, I was just more attentive to his condition.

It included five large cohort studies (which compare the risk of developing the disease in large groups of children, in this case vaccinated and unvaccinated) and five case-control studies (here the focus is on children who have already developed autism, and scientists are investigating what vaccinations they received and whether these circumstances may be related). A total of 1,266,327 children were analyzed, and the authors confidently state that there is no link between vaccination and autism spectrum disorders. At the end there is a touching lyrical digression: “I am an epidemiologist, and I consider our findings reliable,” writes one of the authors. “At the same time, as a father of three children, I understand the fears associated with vaccination. My first two children had febrile seizures due to routine vaccinations. But this did not become a reason for me to refuse to vaccinate a third child, I was just more attentive to his condition.

Cochrane Collaboration, a not-for-profit organization, is said to publish the best articles summarizing drug trial results. There is no established variant of transliteration, the variants "Cochran" and "Cochrane" coexist with numerous derivatives from them. Whatever the case, she has a scientific review on the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine, including the results of 64 large studies involving a total of 14,700,000 children (fourteen million, Carl!). The work is mainly devoted to evaluating the effectiveness of the vaccine (it turns out that a single dose insures against measles in 95% of cases), but it is also noted that the association of vaccination with autism (as well as with asthma, leukemia, hay fever, type 1 diabetes, gait disorders, Crohn's disease, demyelinating diseases and susceptibility to bacterial and viral infections - that's how many horror stories! ) is highly unlikely. Translated from the polite language of science into human language, this means “there is no connection,” just serious scientists try not to make categorical statements.

There is no established variant of transliteration, the variants "Cochran" and "Cochrane" coexist with numerous derivatives from them. Whatever the case, she has a scientific review on the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine, including the results of 64 large studies involving a total of 14,700,000 children (fourteen million, Carl!). The work is mainly devoted to evaluating the effectiveness of the vaccine (it turns out that a single dose insures against measles in 95% of cases), but it is also noted that the association of vaccination with autism (as well as with asthma, leukemia, hay fever, type 1 diabetes, gait disorders, Crohn's disease, demyelinating diseases and susceptibility to bacterial and viral infections - that's how many horror stories! ) is highly unlikely. Translated from the polite language of science into human language, this means “there is no connection,” just serious scientists try not to make categorical statements.

Spoons were found, but the sediment remained

When a person writes a scientific article (or even a popular science book) that serious people will read before publication, he is forced to be careful in wording, refer to sources, not make unsubstantiated strong statements, all the time sprinkle his speech with phrases like “probably ”, “it is not excluded”, “it can be assumed”.

Then, when the author, using the dividends from his printed text, finds himself at a press conference, in front of a television camera, answering questions after a public lecture, he usually allows himself a much greater degree of categoricalness. This is largely an involuntary reaction: you yourself remember better what seems vivid to you, but you cannot double-check it in the mode of direct speech; you understand that if you answer quite correctly, then this is a story for half an hour, and the regulations require two minutes; finally, it's hard not to say what journalists and the audience are obviously and frankly expecting from you, and they are expecting something simple, bright and delightful. Even if you don't want to mislead anyone, it's almost inevitable in spoken language. And if you deliberately want to mislead the public, there is nothing easier than doing it during a public speech. They tell you: “There is no scientific evidence to support your theory,” and you answer: “There is a lot of such data, you are just not familiar with the literature. ” If you do it with a confident enough air, the sympathy of the public will be on your side, and no one will double-check.

Directly in the Lancet publication, Wakefield says the following verbatim about the connection between autism and vaccination: “If there is a causal relationship between the syndrome we have described and vaccination against measles, rubella and mumps, then we can expect an increase in the frequency of the syndrome after the introduction of the vaccine in the UK in 1988 . The available data do not allow us to judge whether there is any change in the frequency of the syndrome or an association with vaccination.” In subsequent public statements, this logically escalated into statements that the complex vaccine causes autism and its use should be stopped.

The content of Wakefield's speeches was not corrected even after the exposure - well, where to go now? “There was no fraud in my research, no falsification, no hoaxes,” the former scientist stands his ground as the TV presenter reads out a long, long line of evidence of forgery. It is important here that any normal person, endowed with the ability to empathize, but not deeply immersed in the topic, when watching such an interview, involuntarily wonders if Wakefield is right - otherwise why would he look so self-confident?

The results of Wakefield's work were not long in coming. In 1997, 91.5% of two-year-old children were vaccinated against measles, mumps and rubella in England. After parents began to massively refuse vaccination, this figure crept down and reached 79.9%. Only after 2004, when the main body of information found by Brian Deer was published, did vaccination rates begin to recover, but it was not until 2012 that a return to baseline was achieved. A similar pattern was observed in other parts of the United Kingdom - Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Wakefield's ideas also influenced other countries; on Russian anti-vaccination websites, he still enjoys honor and respect.

Decreased vaccination rates have predictably increased the incidence of measles. If in 1998 in England and Wales there were 56 laboratory-confirmed cases of measles, then in 2006 there were already 740, and in 2008 this figure reached 1370, and the British Health Protection Agency was forced to state that measles was again in United Kingdom with an endemic disease (that is, the virus is constantly circulating in the population, and is not imported from time to time by sick travelers). The incidence remains high today: during the years of fear of the vaccine, there were quite enough unvaccinated children who grew up so that the measles virus could easily be transmitted from person to person without disappearing from the island.

Is Andrew Wakefield personally to blame for the triumphant return of measles to the UK and neighboring countries? The question is ambiguous. The first measles outbreak after his publications, which broke out in Dublin in 2000 and resulted in the death of three people, could well have been unrelated to Wakefield's charm - even before his speeches, there was not too high a level of vaccination. The boy who died of measles in England in 2006 (the first victim in 14 years, according to WHO) was not vaccinated against measles, not because of his parents' love for Wakefield, but for medical reasons (but, of course, his chances of facing measles has risen significantly due to its widespread prevalence in the UK). During the measles outbreak in Wales in 2013, according to media reports, it was mostly children whose missed routine measles vaccinations fell ill during the period of maximum fear of vaccination, but it is still not possible to establish how many children got measles precisely because of Wakefield, and how many were not vaccinated for some other reason. Wakefield himself, commenting on the situation in Wales, blames the government for everything: if only they would provide people with a good vaccine against measles (tacitly it is implied: for example, the one I patented) instead of the terrible complex vaccine against measles, rubella and mumps - you see, people would then be vaccinated and not get sick.

The boy who died of measles in England in 2006 (the first victim in 14 years, according to WHO) was not vaccinated against measles, not because of his parents' love for Wakefield, but for medical reasons (but, of course, his chances of facing measles has risen significantly due to its widespread prevalence in the UK). During the measles outbreak in Wales in 2013, according to media reports, it was mostly children whose missed routine measles vaccinations fell ill during the period of maximum fear of vaccination, but it is still not possible to establish how many children got measles precisely because of Wakefield, and how many were not vaccinated for some other reason. Wakefield himself, commenting on the situation in Wales, blames the government for everything: if only they would provide people with a good vaccine against measles (tacitly it is implied: for example, the one I patented) instead of the terrible complex vaccine against measles, rubella and mumps - you see, people would then be vaccinated and not get sick.

Where did the vaccine-autism conspiracy come from and why do we know it's a lie

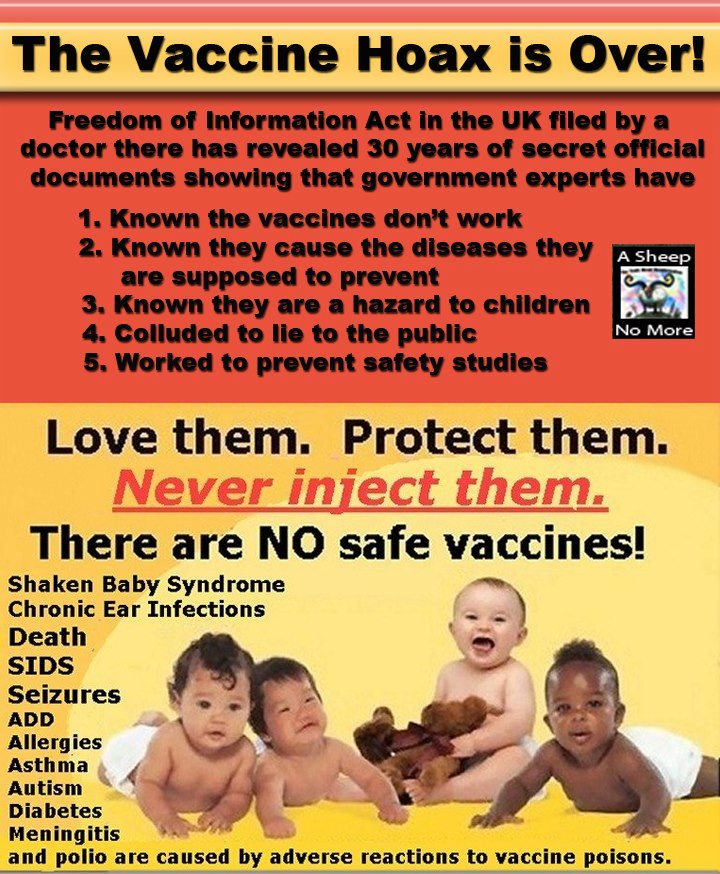

Whatever conspiracy theorists claim, vaccines don't cause autism. Where did this conspiracy theory come from and why do we know it's not true?

The term "autism" refers to a range of autistic disorders that affect how the brain processes information. Each disorder manifests itself in its own way: in some as problems with social skills, in others as repetitive actions, in others as speech or even non-verbal features. Some people with autism need help with daily life, others can live completely independently.

The exact cause of autistic disorders is unknown. There are several factors that seem to increase the risk of developing autism. These are mainly genes and their combinations, to a lesser extent - external factors, such as difficulties during pregnancy and childbirth or the advanced age of one or both parents.

Vaccines, on the other hand, have no effect on the development of autistic disorders, but on the contrary, they save millions of children from illness and death.

Andrew Wakefield in The Lancet

The myth that vaccines cause autism in children became popular in the late 90s due to the publication of the now former British doctor Andrew Wakefield. This work marked the beginning of not only the conspiracy theory about autism, but also largely popularized the modern anti-vaccine movement.

In 1998, the prestigious medical journal The Lancet published an article with Wakefield as the main author. It talked about the link between the MMR vaccine (combined measles, mumps and rubella vaccine) and autism disorders.

Over the past 20 years, scientists have refuted these findings dozens of times in major studies published in prestigious peer-reviewed medical journals. The Lancet withdrew the publication of the article, 10 of Wakefield's co-authors retracted what he had written, and he himself was deprived of his medical license and permanently banned from practicing medicine in the UK.

Issues with article

What was wrong with Wakefield's article?

First, only 12 children participated in his study.

Second, as the investigative reporter who met with all 12 families later learned, all Wakefield's cases involved "distortion and alteration" of the facts.

Third, Wakefield may have had a financial interest in discrediting the MMR vaccine. A few months before the article was published in The Lancet, Wakefield filed a patent for his own measles vaccine. In addition, while writing the article, Wakefield was being paid by his parents' lawyers who were suing the MMR vaccine manufacturers.

Finally, the British General Medical Council - the UK's official register of medical practitioners - took away Wakefield's license in 2010. The Council called his professional practice "irresponsible and dishonorable", saying that not only did he perform unnecessary and painful medical procedures on children (such as a spinal tap), but once at his son's birthday party he paid the children £5 for blood samples.

Real consequences of false science

Since then, dozens of studies have been conducted that have disproved any link between the MMR vaccine and autism, and Wakefield's conclusions have not been confirmed by repeating his work once.

Perhaps the most famous and large-scale study was conducted in Denmark, where they studied 657461 children born in the country from 1999 to 2010. 657461, not 12. Scientists concluded that the vaccine does not contribute to the development of autism and does not increase its risk.

For 20 years, major medical institutes, journals, organizations and scientists have been saying there is no link between MMR or any other vaccine and autism.

But Wakefield doesn't go back on his word. He continues his anti-vaccination activities and is one of the protagonists of this movement. He recently directed the acclaimed—and immediately debunked—movie Vaxxed, in which the characters made a series of fake claims about vaccines.

Unfortunately, the promotion of fake science has real consequences.

Measles is one of the diseases that has been almost eradicated by vaccines, but measles outbreaks have been on the rise in recent years and the number of cases is on the rise.