Types of cognitive distortions

22 Examples & Worksheets (& PDF)

We tend to trust what goes on in our brains. After all, if you can’t trust your own brain, what can you trust?

Generally, this is a good thing—our brain has been wired to alert us to danger, attract us to potential mates, and find solutions to the problems we encounter every day.

However, there are some occasions when you may want to second guess what your brain is telling you. It’s not that your brain is purposely lying to you, it’s just that it may have developed some faulty or non-helpful connections over time.

It can be surprisingly easy to create faulty connections in the brain. Our brains are predisposed to making connections between thoughts, ideas, actions, and consequences, whether they are truly connected or not.

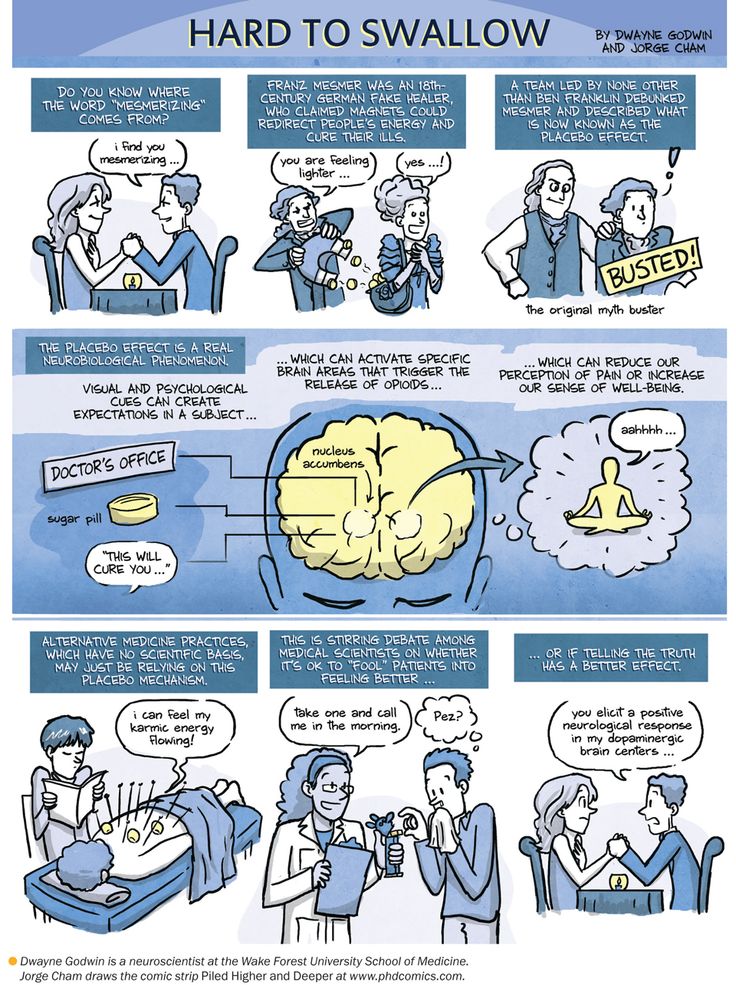

This tendency to make connections where there is no true relationship is the basis of a common problem when it comes to interpreting research: the assumption that because two variables are correlated, one causes or leads to the other. The refrain “correlation does not equal causation!” is a familiar one to any student of psychology or the social sciences.

It is all too easy to view a coincidence or a complicated relationship and make false or overly simplistic assumptions in research—just as it is easy to connect two events or thoughts that occur around the same time when there are no real ties between them.

There are many terms for this kind of mistake in social science research, complete with academic jargon and overly complicated phrasing. In the context of our thoughts and beliefs, these mistakes are referred to as “cognitive distortions.”

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive CBT Exercises for free. These science-based exercises will provide you with a detailed insight into Positive CBT and will give you additional tools to address cognitive distortions in your therapy or coaching.

This Article Contains:

- What are Cognitive Distortions?

- Experts in Cognitive Distortions: Aaron Beck and David Burns

- A List of the Most Common Cognitive Distortions

- Changing Your Thinking: Examples of Techniques to Combat Cognitive Distortions

- A Take-Home Message

- References

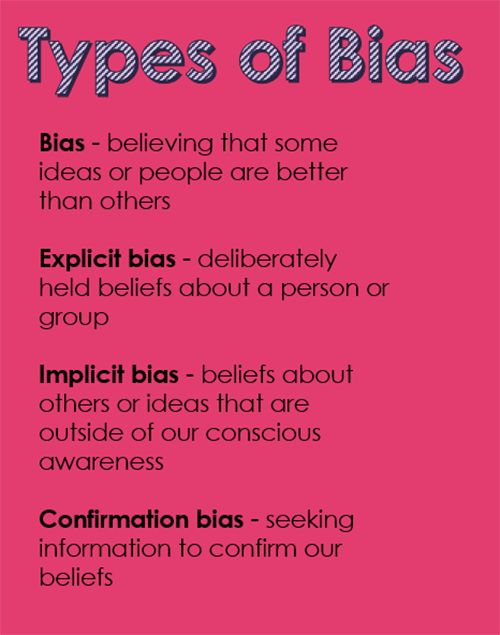

What are Cognitive Distortions?

Cognitive distortions are biased perspectives we take on ourselves and the world around us. They are irrational thoughts and beliefs that we unknowingly reinforce over time.

They are irrational thoughts and beliefs that we unknowingly reinforce over time.

These patterns and systems of thought are often subtle–it’s difficult to recognize them when they are a regular feature of your day-to-day thoughts. That is why they can be so damaging since it’s hard to change what you don’t recognize as something that needs to change!

Cognitive distortions come in many forms (which we’ll cover later in this piece), but they all have some things in common.

All cognitive distortions are:

- Tendencies or patterns of thinking or believing;

- That are false or inaccurate;

- And have the potential to cause psychological damage.

It can be scary to admit that you may fall prey to distorted thinking. You might be thinking, “There’s no way I am holding on to any blatantly false beliefs!” While most people don’t suffer in their daily lives from these kinds of cognitive distortions, it seems that no one can completely escape these distortions.

If you’re human, you have likely fallen for a few of the numerous cognitive distortions at one time or another. The difference between those who occasionally stumble into a cognitive distortion and those who struggle with them on a more long-term basis is the ability to identify and modify or correct these faulty patterns of thinking.

As with many skills and abilities in life, some are far better at this than others–but with practice, you can improve your ability to recognize and respond to these distortions.

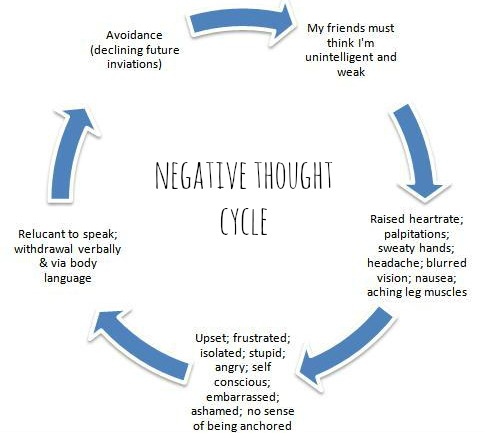

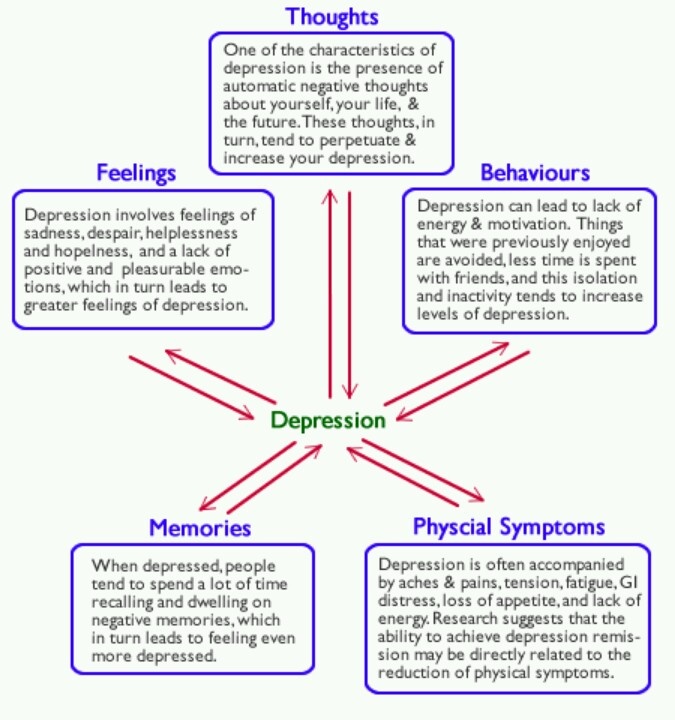

These distortions have been shown to relate positively to symptoms of depression, meaning that where cognitive distortions abound, symptoms of depression are likely to occur as well (Burns, Shaw, & Croker, 1987).

In the words of the renowned psychiatrist and researcher David Burns:

“I suspect you will find that a great many of your negative feelings are in fact based on such thinking errors.”

Errors in thinking, or cognitive distortions, are particularly effective at provoking or exacerbating symptoms of depression. It is still a bit ambiguous as to whether these distortions cause depression or depression brings out these distortions (after all, correlation does not equal causation!) but it is clear that they frequently go hand-in-hand.

It is still a bit ambiguous as to whether these distortions cause depression or depression brings out these distortions (after all, correlation does not equal causation!) but it is clear that they frequently go hand-in-hand.

Much of the knowledge around cognitive distortions come from research by two experts: Aaron Beck and David Burns. Both are prominent in the fields of psychiatry and psychotherapy.

Experts in Cognitive Distortions: Aaron Beck and David Burns

If you dig any deeper into cognitive distortions and their role in depression, anxiety, and other mental health issues, you will find two names over and over again: Aaron Beck and David Burns.

These two psychologists literally wrote the book(s) on depression, cognitive distortions, and the treatment of these problems.

Aaron Beck

Aaron Beck. Image Retrieved by URL.

Aaron Beck began his career at Yale Medical School, where he graduated in 1946 (GoodTherapy, 2015). His required rotations in psychiatry during his residency ignited his passion for research on depression, suicide, and effective treatment.

In 1954, he joined the University of Pennsylvania’s Department of Psychiatry, where he still holds the position of Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry.

In addition to his prodigious catalog of publications, Beck founded the Beck Initiative to teach therapists how to conduct cognitive therapy with their patients–an endeavor that has helped cognitive therapy grow into the therapy juggernaut that it is today.

Beck also applied his knowledge as a member or consultant for the National Institute of Mental Health, an editor for several peer-reviewed journals, and lectures and visiting professorships at various academic institutions throughout the world (GoodTherapy, 2015).

While there are clearly many honors, awards, and achievements Beck may be known for, perhaps his greatest contribution to the field of psychology is his role in the development of cognitive therapy.

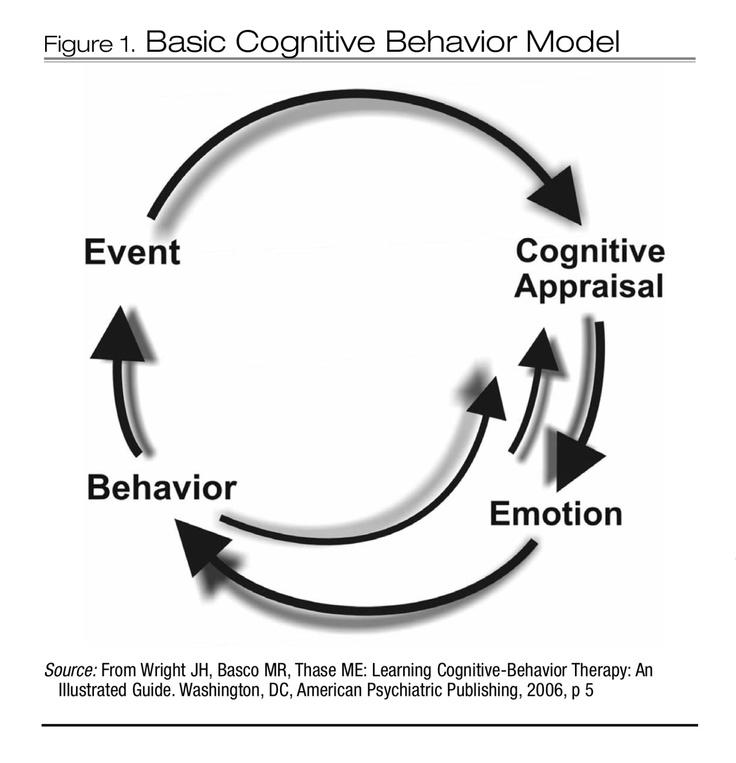

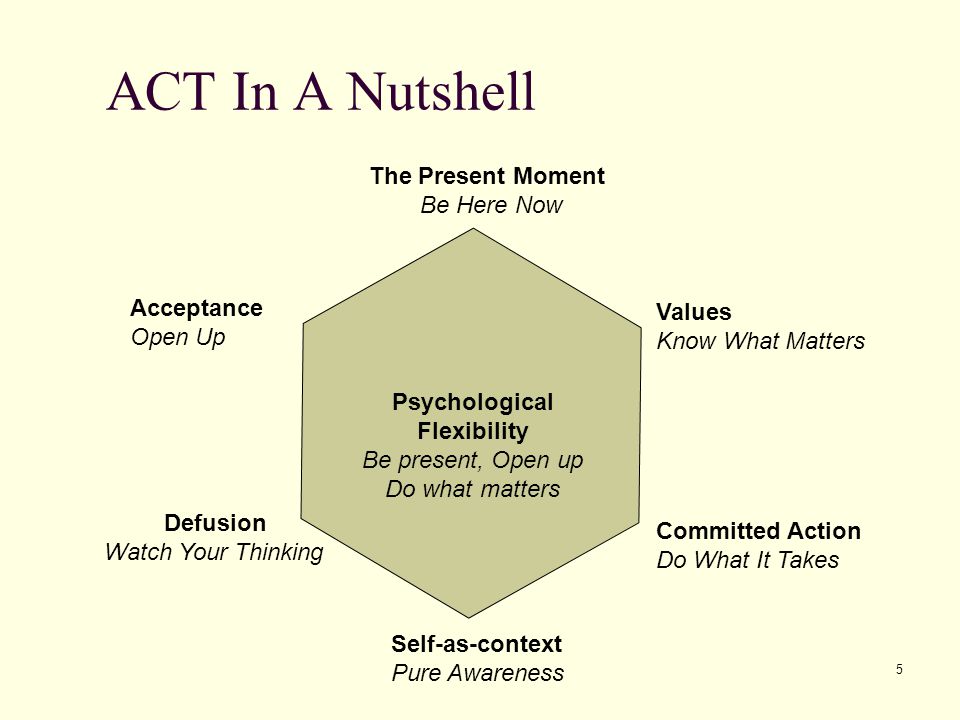

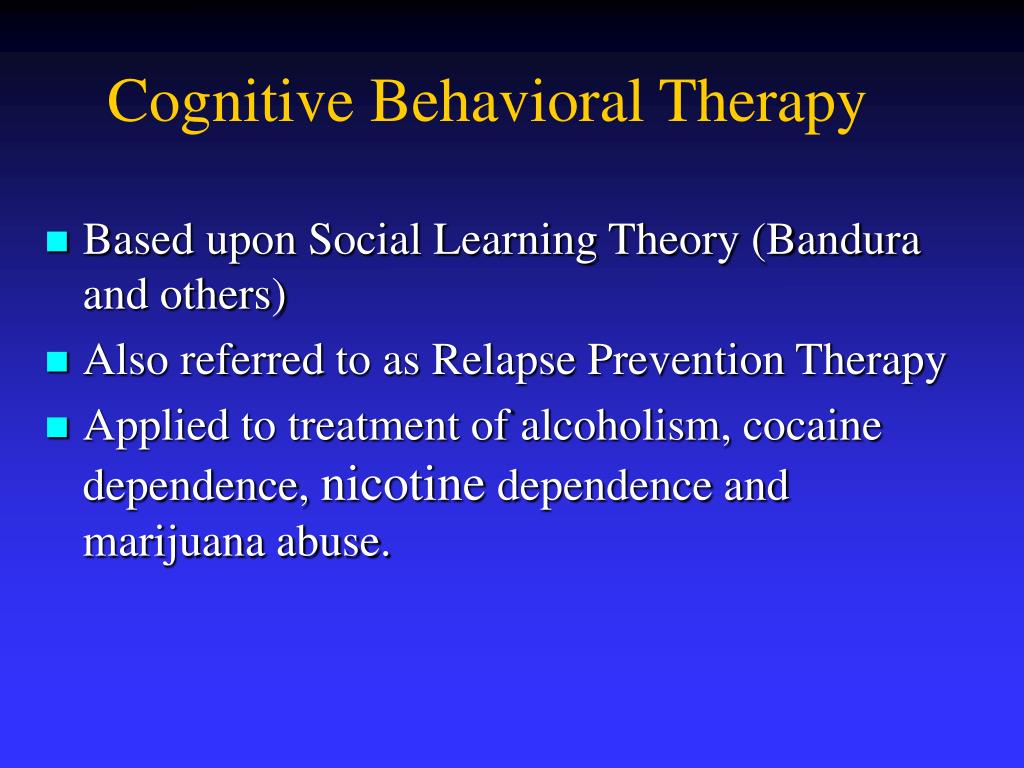

Beck developed the basis for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, or CBT, when he noticed that many of his patients struggling with depression were operating on false assumptions and distorted thinking (GoodTherapy, 2015). He connected these distorted thinking patterns with his patients’ symptoms and hypothesized that changing their thinking could change their symptoms.

He connected these distorted thinking patterns with his patients’ symptoms and hypothesized that changing their thinking could change their symptoms.

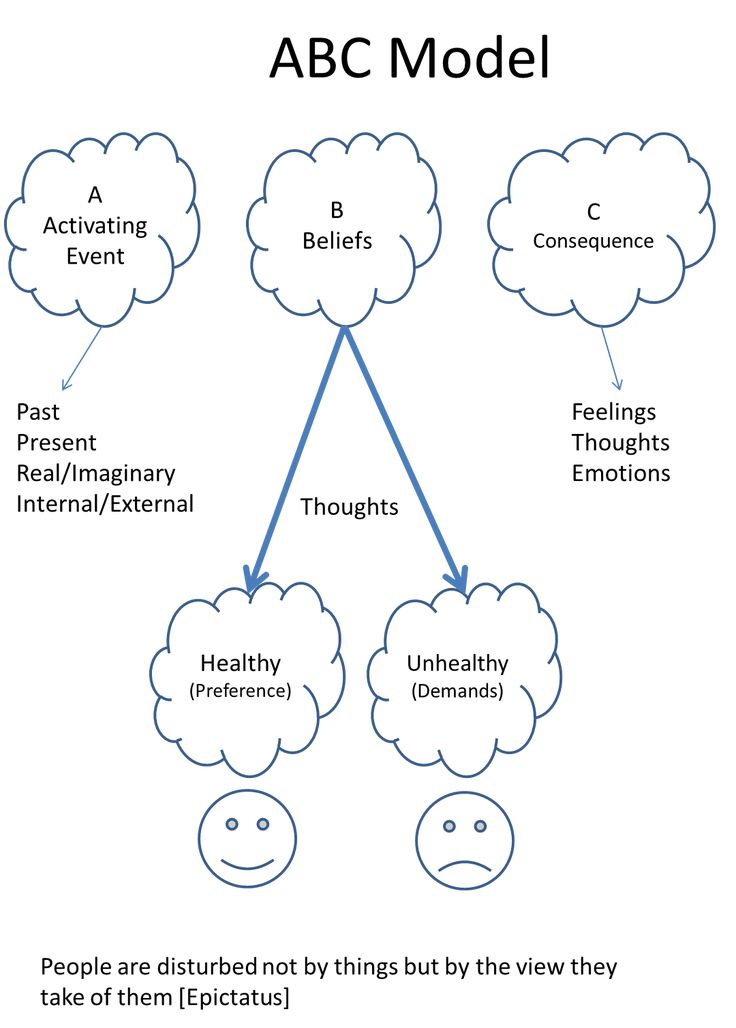

This is the foundation of CBT – the idea that our thought patterns and deeply held beliefs about ourselves and the world around us drive our experiences. This can lead to mental health disorders when they are distorted but can be modified or changed to eliminate troublesome symptoms.

In line with his general research focus, Beck also developed two important scales that are among some of the most used scales in psychology: the Beck Depression Inventory and the Beck Hopelessness Scale. These scales are used to evaluate symptoms of depression and risk of suicide and are still applied decades after their original development (GoodTherapy, 2015).

David Burns

Another big name in depression and treatment research, Dr. David Burns, also spent some time learning and developing his skills at the University of Pennsylvania – it seems that UPenn is particularly good at producing future leaders in psychology!

Burns graduated from Stanford University School of Medicine and moved on to the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, where he completed his psychiatry residency and cemented his interest in the treatment of mental health disorders (Feeling Good, n. d.).

d.).

He is currently serving as a Professor Emeritus of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the Stanford University School of Medicine, in addition to continuing his research on treating depression and training therapists to conduct effective psychotherapy sessions (Feeling Good, n.d.). Much of his work is based on Beck’s research revealing the potential impacts of distorted thinking and suggesting ways to correct this thinking.

He is perhaps most well known outside of strictly academic circles for his worldwide best-selling book Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy. This book has sold more than 4 million copies within the United States alone and is often recommended by therapists to their patients struggling with depression (Summit for Clinical Excellence, n.d.).

This book outlines Burns’ approach to treating depression, which mostly focuses on identifying, correcting, and replacing distorted systems and patterns of thinking. If you are interested in learning more about this book, you can find it on Amazon with over 1,400 reviews to help you evaluate its effectiveness.

To hear more about Burns’ work in the treatment of depression, check out his TED talk on the subject below.

As Burns discusses in the above video, his studies of depression have also influenced the studies around joy and self-esteem. The most researched form of psychotherapy right now is covered by his book, Feeling Good, aimed at providing tools to the general public.

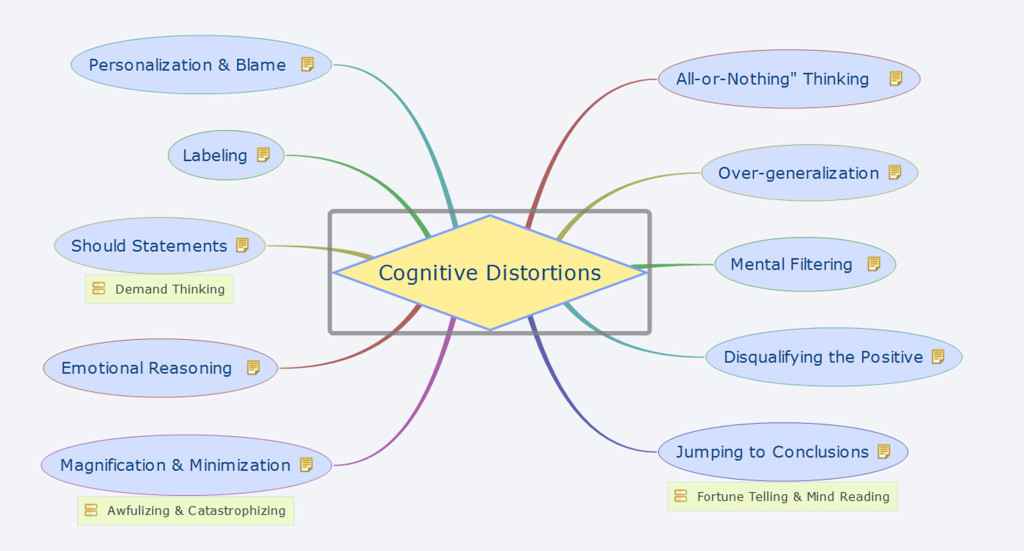

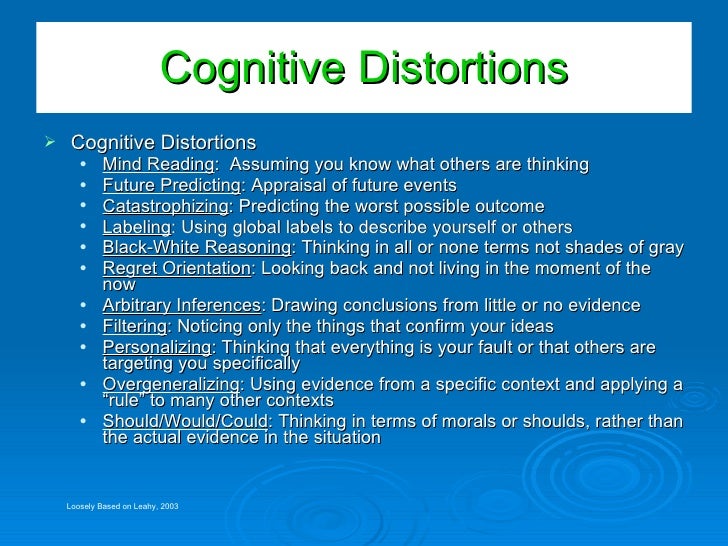

A List of the Most Common Cognitive Distortions

Beck and Burns are not the only two researchers who have dedicated their careers to learn more about depression, cognitive distortions, and treatment for these conditions.

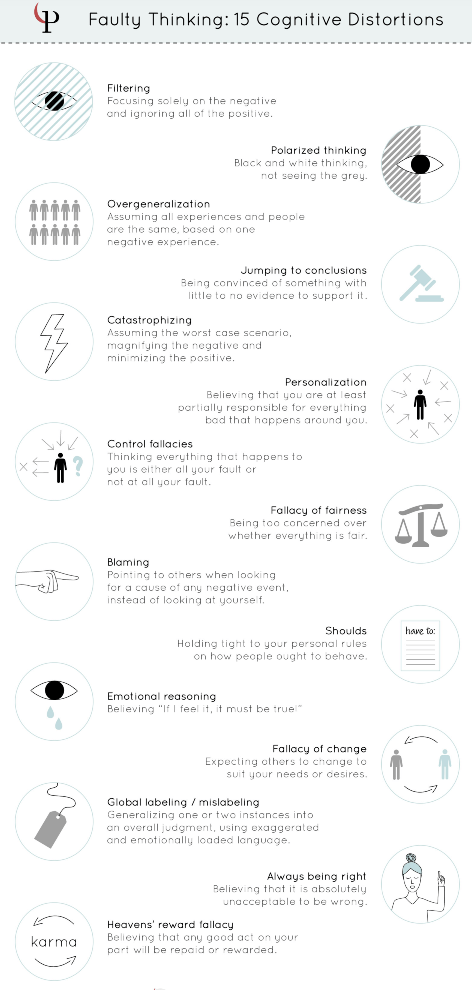

There are many others who have picked up the torch for this research, often with their own take on cognitive distortions. As such, there are numerous cognitive distortions floating around in the literature, but we’ll limit this list to the most common sixteen.

As such, there are numerous cognitive distortions floating around in the literature, but we’ll limit this list to the most common sixteen.

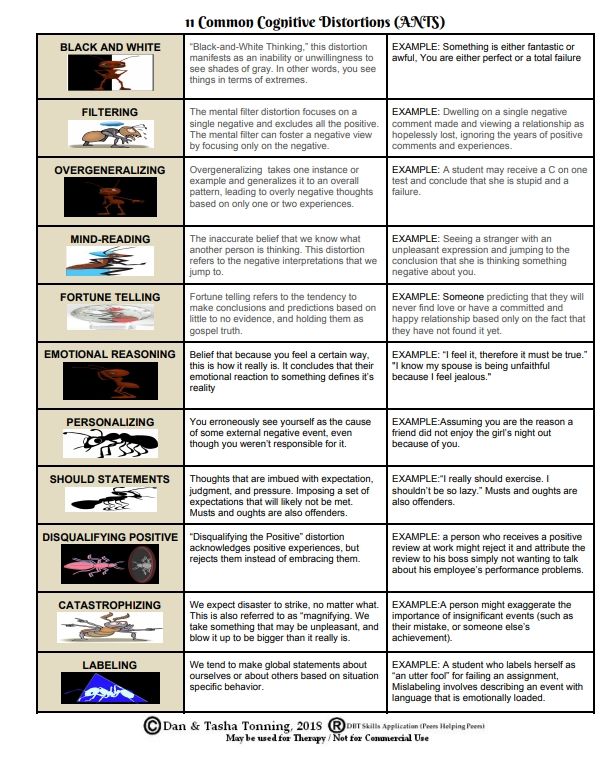

The first eleven distortions come straight from Burns’ Feeling Good Handbook (1989).

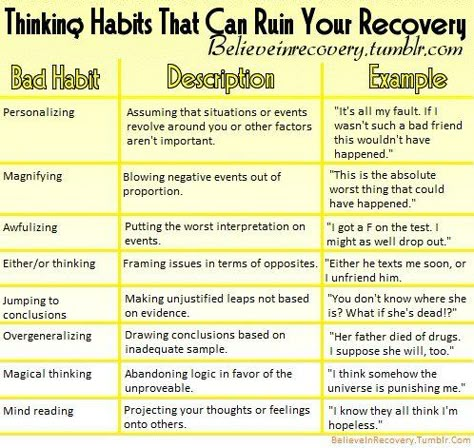

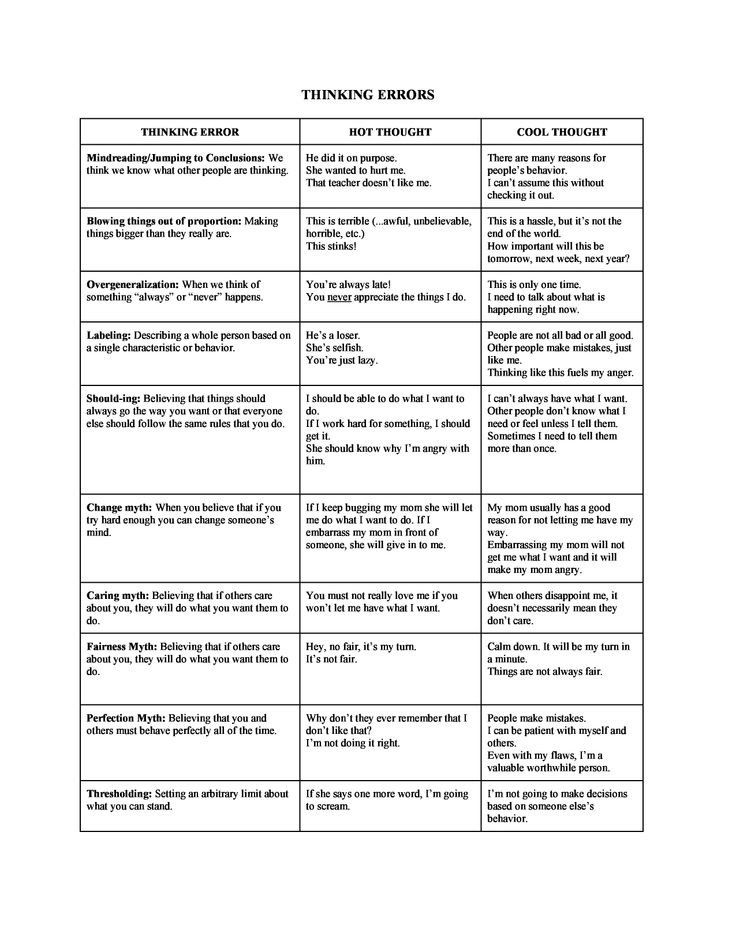

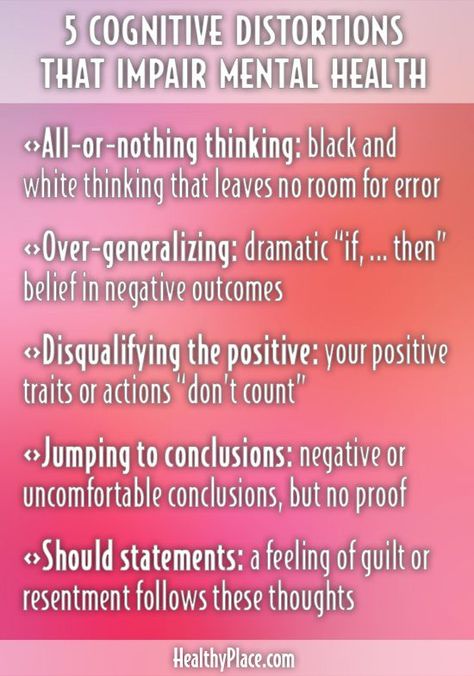

1. All-or-Nothing Thinking / Polarized Thinking

Also known as “Black-and-White Thinking,” this distortion manifests as an inability or unwillingness to see shades of gray. In other words, you see things in terms of extremes – something is either fantastic or awful, you believe you are either perfect or a total failure.

2. Overgeneralization

This sneaky distortion takes one instance or example and generalizes it to an overall pattern. For example, a student may receive a C on one test and conclude that she is stupid and a failure. Overgeneralizing can lead to overly negative thoughts about yourself and your environment based on only one or two experiences.

3. Mental Filter

Similar to overgeneralization, the mental filter distortion focuses on a single negative piece of information and excludes all the positive ones. An example of this distortion is one partner in a romantic relationship dwelling on a single negative comment made by the other partner and viewing the relationship as hopelessly lost, while ignoring the years of positive comments and experiences.

An example of this distortion is one partner in a romantic relationship dwelling on a single negative comment made by the other partner and viewing the relationship as hopelessly lost, while ignoring the years of positive comments and experiences.

The mental filter can foster a decidedly pessimistic view of everything around you by focusing only on the negative.

4. Disqualifying the Positive

On the flip side, the “Disqualifying the Positive” distortion acknowledges positive experiences but rejects them instead of embracing them.

For example, a person who receives a positive review at work might reject the idea that they are a competent employee and attribute the positive review to political correctness, or to their boss simply not wanting to talk about their employee’s performance problems.

This is an especially malignant distortion since it can facilitate the continuation of negative thought patterns even in the face of strong evidence to the contrary.

5.

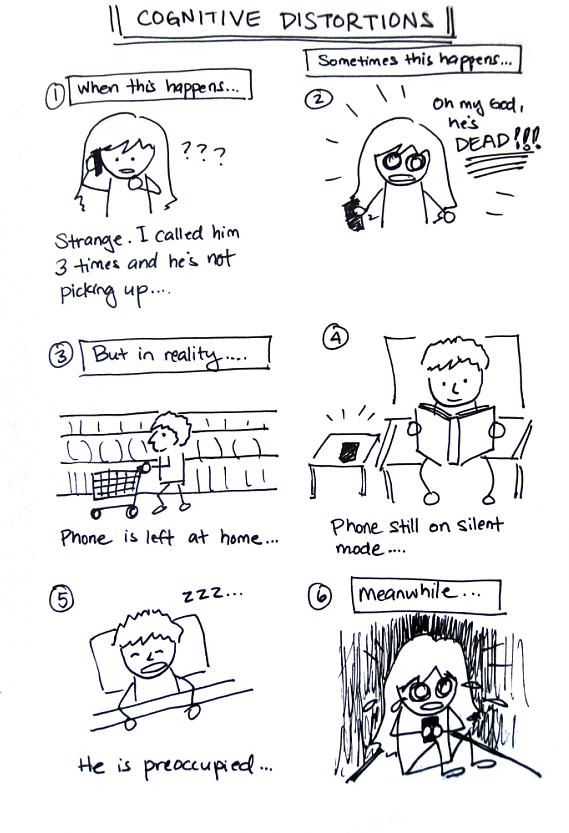

Jumping to Conclusions – Mind Reading

Jumping to Conclusions – Mind ReadingThis “Jumping to Conclusions” distortion manifests as the inaccurate belief that we know what another person is thinking. Of course, it is possible to have an idea of what other people are thinking, but this distortion refers to the negative interpretations that we jump to.

Seeing a stranger with an unpleasant expression and jumping to the conclusion that they are thinking something negative about you is an example of this distortion.

6. Jumping to Conclusions – Fortune Telling

A sister distortion to mind reading, fortune telling refers to the tendency to make conclusions and predictions based on little to no evidence and holding them as gospel truth.

One example of fortune-telling is a young, single woman predicting that she will never find love or have a committed and happy relationship based only on the fact that she has not found it yet. There is simply no way for her to know how her life will turn out, but she sees this prediction as fact rather than one of several possible outcomes.

7. Magnification (Catastrophizing) or Minimization

Also known as the “Binocular Trick” for its stealthy skewing of your perspective, this distortion involves exaggerating or minimizing the meaning, importance, or likelihood of things.

An athlete who is generally a good player but makes a mistake may magnify the importance of that mistake and believe that he is a terrible teammate, while an athlete who wins a coveted award in her sport may minimize the importance of the award and continue believing that she is only a mediocre player.

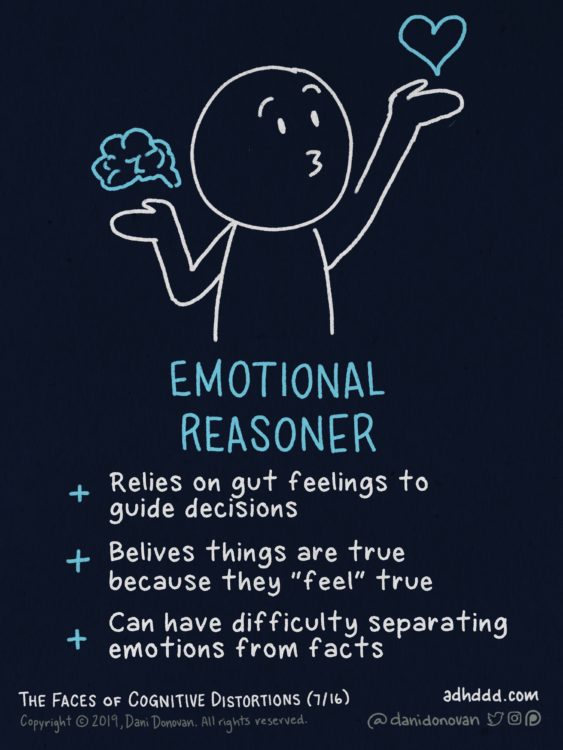

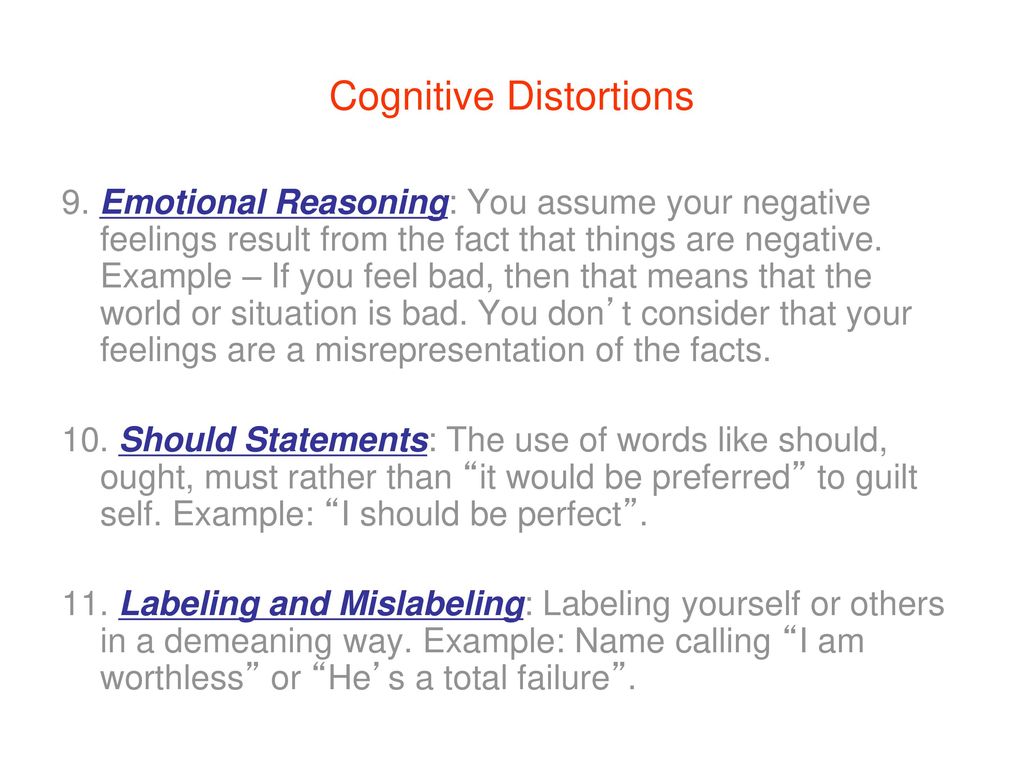

8. Emotional Reasoning

This may be one of the most surprising distortions to many readers, and it is also one of the most important to identify and address. The logic behind this distortion is not surprising to most people; rather, it is the realization that virtually all of us have bought into this distortion at one time or another.

Emotional reasoning refers to the acceptance of one’s emotions as fact. It can be described as “I feel it, therefore it must be true. ” Just because we feel something doesn’t mean it is true; for example, we may become jealous and think our partner has feelings for someone else, but that doesn’t make it true. Of course, we know it isn’t reasonable to take our feelings as fact, but it is a common distortion nonetheless.

” Just because we feel something doesn’t mean it is true; for example, we may become jealous and think our partner has feelings for someone else, but that doesn’t make it true. Of course, we know it isn’t reasonable to take our feelings as fact, but it is a common distortion nonetheless.

Relevant: What is Emotional Intelligence? + 18 Ways to Improve It

9. Should Statements

Another particularly damaging distortion is the tendency to make “should” statements. Should statements are statements that you make to yourself about what you “should” do, what you “ought” to do, or what you “must” do. They can also be applied to others, imposing a set of expectations that will likely not be met.

When we hang on too tightly to our “should” statements about ourselves, the result is often guilt that we cannot live up to them. When we cling to our “should” statements about others, we are generally disappointed by their failure to meet our expectations, leading to anger and resentment.

10. Labeling and Mislabeling

These tendencies are basically extreme forms of overgeneralization, in which we assign judgments of value to ourselves or to others based on one instance or experience.

For example, a student who labels herself as “an utter fool” for failing an assignment is engaging in this distortion, as is the waiter who labels a customer “a grumpy old miser” if he fails to thank the waiter for bringing his food. Mislabeling refers to the application of highly emotional, loaded, and inaccurate or unreasonable language when labeling.

11. Personalization

As the name implies, this distortion involves taking everything personally or assigning blame to yourself without any logical reason to believe you are to blame.

This distortion covers a wide range of situations, from assuming you are the reason a friend did not enjoy the girls’ night out, to the more severe examples of believing that you are the cause for every instance of moodiness or irritation in those around you.

In addition to these basic cognitive distortions, Beck and Burns have mentioned a few others (Beck, 1976; Burns, 1980):

12. Control Fallacies

A control fallacy manifests as one of two beliefs: (1) that we have no control over our lives and are helpless victims of fate, or (2) that we are in complete control of ourselves and our surroundings, giving us responsibility for the feelings of those around us. Both beliefs are damaging, and both are equally inaccurate.

No one is in complete control of what happens to them, and no one has absolutely no control over their situation. Even in extreme situations where an individual seemingly has no choice in what they do or where they go, they still have a certain amount of control over how they approach their situation mentally.

13. Fallacy of Fairness

While we would all probably prefer to operate in a world that is fair, the assumption of an inherently fair world is not based in reality and can foster negative feelings when we are faced with proof of life’s unfairness.

A person who judges every experience by its perceived fairness has fallen for this fallacy, and will likely feel anger, resentment, and hopelessness when they inevitably encounter a situation that is not fair.

14. Fallacy of Change

Another ‘fallacy’ distortion involves expecting others to change if we pressure or encourage them enough. This distortion is usually accompanied by a belief that our happiness and success rests on other people, leading us to believe that forcing those around us to change is the only way to get what we want.

A man who thinks “If I just encourage my wife to stop doing the things that irritate me, I can be a better husband and a happier person” is exhibiting the fallacy of change.

15. Always Being Right

Perfectionists and those struggling with Imposter Syndrome will recognize this distortion – it is the belief that we must always be right. For those struggling with this distortion, the idea that we could be wrong is absolutely unacceptable, and we will fight to the metaphorical death to prove that we are right.

For example, the internet commenters who spend hours arguing with each other over an opinion or political issue far beyond the point where reasonable individuals would conclude that they should “agree to disagree” are engaging in the “Always Being Right” distortion. To them, it is not simply a matter of a difference of opinion, it is an intellectual battle that must be won at all costs.

16. Heaven’s Reward Fallacy

This distortion is a popular one, and it’s easy to see myriad examples of this fallacy playing out on big and small screens across the world. The “Heaven’s Reward Fallacy” manifests as a belief that one’s struggles, one’s suffering, and one’s hard work will result in a just reward.

It is obvious why this type of thinking is a distortion – how many examples can you think of, just within the realm of your personal acquaintances, where hard work and sacrifice did not pay off?

Sometimes no matter how hard we work or how much we sacrifice, we will not achieve what we hope to achieve. To think otherwise is a potentially damaging pattern of thought that can result in disappointment, frustration, anger, and even depression when the awaited reward does not materialize.

To think otherwise is a potentially damaging pattern of thought that can result in disappointment, frustration, anger, and even depression when the awaited reward does not materialize.

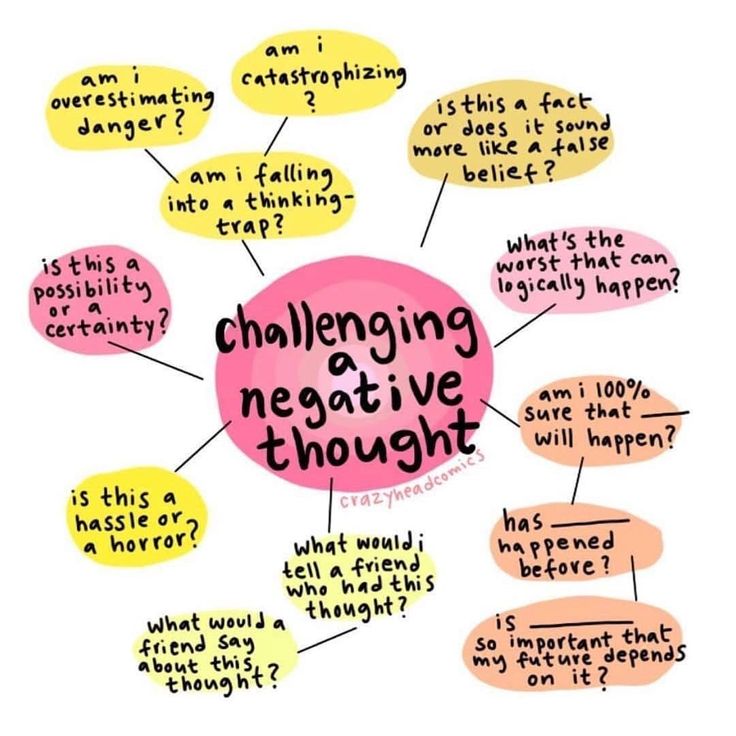

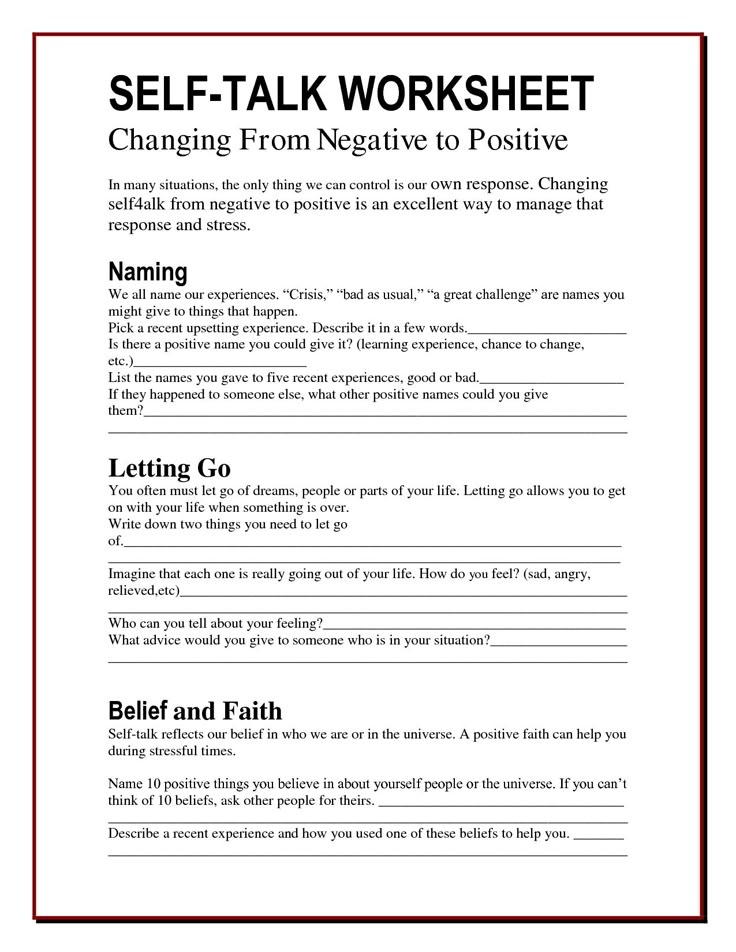

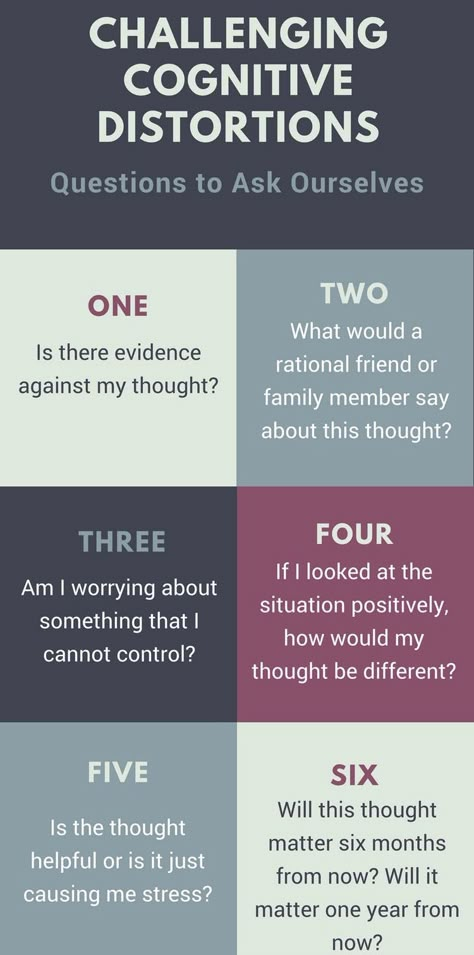

Changing Your Thinking: Examples of Techniques to Combat Cognitive Distortions

These distortions, while common and potentially extremely damaging, are not something we must simply resign ourselves to living with.

Beck, Burns, and other researchers in this area have developed numerous ways to identify, challenge, minimize, or erase these distortions from our thinking.

Some of the most effective and evidence-based techniques and resources are listed below.

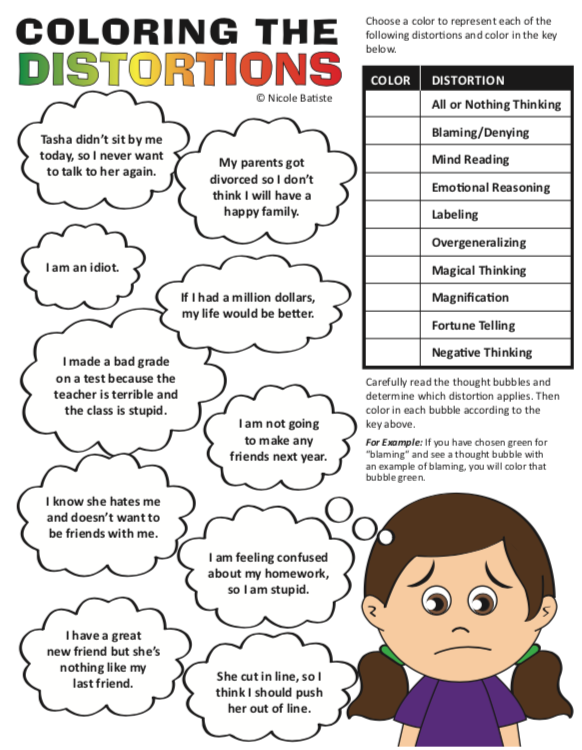

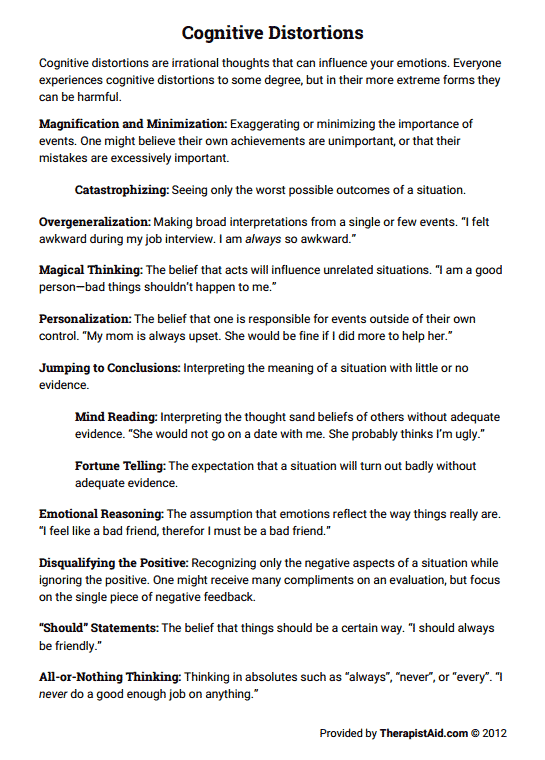

Cognitive Distortions Handout

Since you must first identify the distortions you struggle with before you can effectively challenge them, this resource is a must-have.

The Cognitive Distortions handout lists and describes several types of cognitive distortions to help you figure out which ones you might be dealing with.

The distortions listed include:

- All-or-Nothing Thinking;

- Overgeneralizing;

- Discounting the Positive;

- Jumping to Conclusions;

- Mind Reading;

- Fortune Telling;

- Magnification (Catastrophizing) and Minimizing;

- Emotional Reasoning;

- Should Statements;

- Labeling and Mislabeling;

- Personalization.

The descriptions are accompanied by helpful descriptions and a couple of examples.

This information can be found in the Increasing Awareness of Cognitive Distortions exercise in the Positive Psychology Toolkit©.

Automatic Thought Record

This worksheet is an excellent tool for identifying and understanding your cognitive distortions. Our automatic, negative thoughts are often related to a distortion that we may or may not realize we have. Completing this exercise can help you to figure out where you are making inaccurate assumptions or jumping to false conclusions.

The worksheet is split into six columns:

- Date/Time

- Situation

- Automatic Thoughts (ATs)

- Emotion/s

- Your Response

- A More Adaptive Response

First, you note the date and time of the thought.

In the second column, you will write down the situation. Ask yourself:

- What led to this event?

- What caused the unpleasant feelings I am experiencing?

The third component of the worksheet directs you to write down the negative automatic thought, including any images or feelings that accompanied the thought. You will consider the thoughts and images that went through your mind, write them down, and determine how much you believed these thoughts.

After you have identified the thought, the worksheet instructs you to note the emotions that ran through your mind along with the thoughts and images identified. Ask yourself what emotions you felt at the time and how intense the emotions were on a scale from 1 (barely felt it) to 10 (completely overwhelming).

Next, you have an opportunity to come up with an adaptive response to those thoughts. This is where the real work happens, where you identify the distortions that are cropping up and challenge them.

Ask yourself these questions:

- Which cognitive distortions were you employing?

- What is the evidence that the automatic thought(s) is true, and what evidence is there that it is not true?

- You’ve thought about the worst that can happen, but what’s the best that could happen? What’s the most realistic scenario?

- How likely are the best-case and most realistic scenarios?

Finally, you will consider the outcome of this event. Think about how much you believe the automatic thought now that you’ve come up with an adaptive response, and rate your belief. Determine what emotion(s) you are feeling now and at what intensity you are experiencing them.

You can access the Automatic Thought Record Worksheet here.

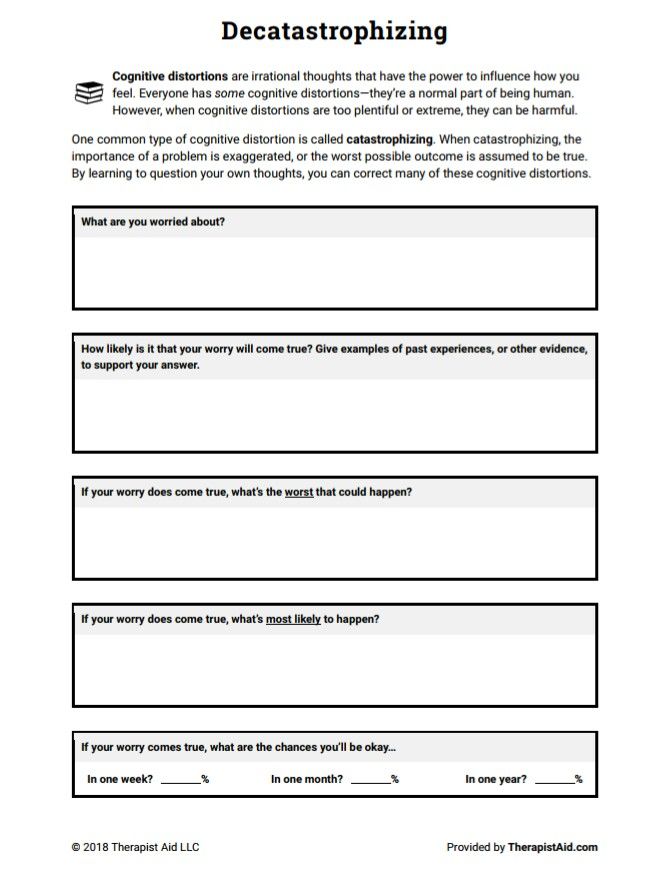

Decatastrophizing

This is a particularly good tool for talking yourself out of catastrophizing a situation.

The worksheet begins with a description of cognitive distortions in general and catastrophizing in particular; catastrophizing is when you distort the importance or meaning of a problem to be much worse than it is, or you assume that the worst possible scenario is going to come to pass. It’s a reinforcing distortion, as you get more and more anxious the more you think about it, but there are ways to combat it.

First, write down your worry. Identify the issue you are catastrophizing by answering the question, “What are you worried about?”

Once you have articulated the issue that is worrying you, you can move on to thinking about how this issue will turn out.

Think about how terrible it would be if the catastrophe actually came to pass. What is the worst-case scenario? Consider whether a similar event has occurred in your past and, if so, how often it occurred. With the frequency of this catastrophe in mind, make an educated guess of how likely the worst-case scenario is to happen.

After this, think about what is most likely to happen–not the best possible outcome, not the worst possible outcome, but the most likely. Consider this scenario in detail and write it down. Note how likely you think this scenario is to happen as well.

Next, think about your chances of surviving in one piece. How likely is it that you’ll be okay one week from now if your fear comes true? How likely is it that you’ll be okay in one month? How about one year? For all three, write down “Yes” if you think you’d be okay and “No” if you don’t think you’d be okay.

Finally, come back to the present and think about how you feel right now. Are you still just as worried, or did the exercise help you think a little more realistically? Write down how you’re feeling about it.

This worksheet can be an excellent resource for anyone who is worrying excessively about a potentially negative event.

You can download the Decatastrophizing Worksheet here.

Cataloging Your Inner Rules

Cognitive distortions include assumptions and rules that we hold dearly or have decided we must live by. Sometimes these rules or assumptions help us to stick to our values or our moral code, but often they can limit and frustrate us.

Sometimes these rules or assumptions help us to stick to our values or our moral code, but often they can limit and frustrate us.

This exercise can help you to think more critically about an assumption or rule that may be harmful.

First, think about a recent scenario where you felt bad about your thoughts or behavior afterward. Write down a description of the scenario and the infraction (what you did to break the rule).

Next, based on your infraction, identify the rule or assumption that was broken. What are the parameters of the rule? How does it compel you to think or act?

Once you have described the rule or assumption, think about where it came from. Consider when you acquired this rule, how you learned about it, and what was happening in your life that encouraged you to adopt it. What makes you think it’s a good rule to have?

Now that you have outlined a definition of the rule or assumption and its origins and impact on your life, you can move on to comparing its advantages and disadvantages. Every rule or assumption we follow will likely have both advantages and disadvantages.

Every rule or assumption we follow will likely have both advantages and disadvantages.

The presence of one advantage does not mean the rule or assumption is necessarily a good one, just as the presence of one disadvantage does not automatically make the rule or assumption a bad one. This is where you must think critically about how the rule or assumption helps and/or hurts you.

Finally, you have an opportunity to think about everything you have listed and decide to either accept the rule as it is, throw it out entirely and create a new one, or modify it into a rule that would suit you better. This may be a small change or a big modification.

If you decide to change the rule or assumption, the new version should maximize the advantages of the rule, minimize or limit the disadvantages, or both. Write down this new and improved rule and consider how you can put it into practice in your daily life.

You can download the Cataloging Your Inner Rules Worksheet.

Facts or Opinions?

This is one of the first lessons that participants in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) learn – that facts are not opinions. As obvious as this seems, it can be difficult to remember and adhere to this fact in your day to day life.

As obvious as this seems, it can be difficult to remember and adhere to this fact in your day to day life.

This exercise can help you learn the difference between fact and opinion, and prepare you to distinguish between your own opinions and facts.

The worksheet lists the following fifteen statements and asks the reader to decide whether they are fact or opinion:

- I am a failure.

- I’m uglier than him/her.

- I said “no” to a friend in need.

- A friend in need said “no” to me.

- I suck at everything.

- I yelled at my partner.

- I can’t do anything right.

- He said some hurtful things to me.

- She didn’t care about hurting me.

- This will be an absolute disaster.

- I’m a bad person.

- I said things I regret.

- I’m shorter than him.

- I am not loveable.

- I’m selfish and uncaring.

- Everyone is a way better person than I am.

- Nobody could ever love me.

- I am overweight for my height.

- I ruined the evening.

- I failed my exam.

Practicing making this distinction between fact and opinion can improve your ability to quickly differentiate between the two when they pop up in your own thoughts.

Here is the Facts or Opinions Worksheet.

In case you’re wondering which is which, here is the key:

- I am a failure. False

- I’m uglier than him/her. False

- I said “no” to a friend in need. True

- A friend in need said “no” to me. True

- I suck at everything. False

- I yelled at my partner. True

- I can’t do anything right. False

- He said some hurtful things to me. True

- She didn’t care about hurting me. False

- This will be an absolute disaster. False

- I’m a bad person. False

- I said things I regret. True

- I’m shorter than him. True

- I am not loveable.

False

False - I’m selfish and uncaring. False

- Everyone is a way better person than I am. False

- Nobody could ever love me. False

- I am overweight for my height. True

- I ruined the evening. False

- I failed my exam. True

Putting Thoughts on Trial

This exercise uses CBT theory and techniques to help you examine your irrational thoughts. You will act as the defense attorney, prosecutor, and judge all at once, providing evidence for and against the irrational thought and evaluating the merit of the thought based on this evidence.

The worksheet begins with an explanation of the exercise and a description of the roles you will be playing.

The first box to be completed is “The Thought.” This is where you write down the irrational thought that is being put on trial.

Next, you fill out “The Defense” box with evidence that corroborates or supports the thought. Once you have listed all of the defense’s evidence, do the same for “The Prosecution” box. Write down all of the evidence calling the thought into question or instilling doubt in its accuracy.

Once you have listed all of the defense’s evidence, do the same for “The Prosecution” box. Write down all of the evidence calling the thought into question or instilling doubt in its accuracy.

When you have listed all of the evidence you can think of, both for and against the thought, evaluate the evidence and write down the results of your evaluation in “The Judge’s Verdict” box.

This worksheet is a fun and engaging way to think critically about your negative or irrational thoughts and make good decisions about which thoughts to modify and which to embrace.

Click here to see this worksheet for yourself (TherapistAid).

A Take-Home Message

Hopefully, this piece has given you a good understanding of cognitive distortions. These sneaky, inaccurate patterns of thinking and believing are common, but their potential impact should not be underestimated.

Even if you are not struggling with depression, anxiety, or another serious mental health issue, it doesn’t hurt to evaluate your own thoughts every now and then. The sooner you catch a cognitive distortion and mount a defense against it, the less likely it is to make a negative impact on your life.

The sooner you catch a cognitive distortion and mount a defense against it, the less likely it is to make a negative impact on your life.

What is your experience with cognitive distortions? Which ones do you struggle with? Do you think we missed any important ones? How have you tackled them, whether in CBT or on your own?

Let us know in the comments below. We love hearing from you.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. For more information, don’t forget to download our 3 Positive CBT Exercises for free.

- Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapies and emotional disorders. New York, NY: New American Library.

- Burns, D. D. (1980). Feeling good: The new mood therapy. New York, NY: New American Library.

- Burns, D. D. (1989). The feeling good handbook. New York, NY: Morrow.

- Burns, D. D., Shaw, B. F., & Croker, W. (1987). Thinking styles and coping strategies of depressed women: An empirical investigation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 25, 223-225.

- Feeling Good. (n.d.). About. Feeling Good. Retrieved from https://feelinggood.com/about/

- GoodTherapy. (2015). Aaron Beck. GoodTherapy LLC. Retrieved from https://www.goodtherapy.org/famous-psychologists/aaron-beck.html

- Summit for Clinical Excellence. (n.d.). David Burns, MD. Summit for clinical excellence faculty page. Retrieved from https://summitforclinicalexcellence.com/partners/faculty/david-burns/

- TherapistAid. (n.d.). Cognitive restructuring: Thoughts on trial. Retrieved from https://www.therapistaid.com/worksheets/putting-thoughts-on-trial.pdf

15 Cognitive Distortions to Blame for Your Negative Thinking

A distorted thought or cognitive distortion — and there are many — is an exaggerated pattern of thought that’s not based on facts. It consequently leads you to view things more negatively than they really are.

In other words, cognitive distortions are your mind convincing you to believe negative things about yourself and your world that are not necessarily true.

Our thoughts have a great impact on how we feel and how we behave. When you treat these negative thoughts as facts, you may see yourself and act in a way based on faulty assumptions.

Everyone falls into cognitive distortions on occasion. It’s part of the human experience. This happens particularly when we’re feeling down.

But if you engage too frequently in negative thoughts, your mental health can take a hit.

You can learn to identify cognitive distortions so that you’ll know when your mind is playing tricks on you. Then you can reframe and redirect your thoughts so that they have less of a negative impact on your mood and behaviors.

The most common cognitive distortions or distorted thoughts include:

- filtering

- polarization

- overgeneralization

- discounting the positive

- jumping to conclusions

- catastrophizing

- personalization

- control fallacies

- fallacy of fairness

- blaming

- shoulds

- emotional reasoning

- fallacy of change

- global labeling

- always being right

You may identify with some more than others or recognize you tend to use one in particular for specific situations. This is natural.

This is natural.

Self-examination might be the first step toward reversing negative thinking and some of these thought patterns.

Here’s a closer look at the list of cognitive distortions:

Filtering

Mental filtering is draining and straining all positives in a situation and, instead, dwelling on its negatives.

Even if there are more positive aspects than negative in a situation or person, you focus on the negatives exclusively.

Example

It’s performance review time at your company, and your manager compliments your hard work several times. In the end, they make one improvement suggestion. You leave the meeting feeling miserable and dwell on that one suggestion all day long.

Polarization or all-or-nothing thinking

Polarized thinking is thinking about yourself and the world in an “all-or-nothing” way.

When you engage in thoughts of black or white, with no shades of gray, this type of cognitive distortion is leading you.

Example

Your coworker was a saint until she ate your sandwich. Now, you cannot stand her. Or, you got a B on your last test, so you have failed at being a good student despite getting only A’s before that.

All-or-nothing thinking usually leads to extremely unrealistic standards for yourself and others that could affect your relationships and motivation.

Black-or-white thoughts may also set you up for failure.

Example

You’ve decided to eat healthy foods. But today, you didn’t have time to prepare a meal, so you eat a bacon burger. This immediately leads you to conclude that you’ve ruined your healthy eating routine, so you decide to no longer even try.

When you engage in polarized thinking, everything is in “either/or” categories. This might make you miss the complexity of most people and situations.

Overgeneralization

When you overgeneralize something, you take an isolated negative event and turn it into a never-ending pattern of loss and defeat.

With overgeneralization, words like “always,” “never,” “everything,” and “nothing” are frequent in your train of thought.

Example

You speak up at a team meeting, and your suggestions are not included in the project. You leave the meeting thinking, “I ruined my chances for a promotion. I never say the right thing!”

Overgeneralization can also manifest in your thoughts about the world and its events.

Example

You’re running late for work, and on your way there, you hit a red light. You think, “Nothing ever goes my way!”

Discounting the positive

Discounting positives is similar to mental filtering. The main difference is that you dismiss it as something of no value when you do think of positive aspects.

Example

If someone compliments the way you look today, you think they’re just being nice.

If your boss tells you how comprehensive your report was, you discount it as something anyone else could do.

If you do well in that job interview, you think it’s because they didn’t realize you’re not that good.

Jumping to conclusions

When you jump to conclusions, you interpret an event or situation negatively without evidence supporting such a conclusion. Then, you react to your assumption.

Example

Your partner comes home looking serious. Instead of asking how they are, you immediately assume they’re mad at you. Consequently, you keep your distance. In reality, your partner had a bad day at work.

Jumping to conclusions or “mind-reading” is often in response to a persistent thought or concern of yours.

Example

You feel insecure about your relationship. So, when you see your partner looking serious, you assume they might be losing interest in you.

Catastrophizing

Catastrophizing is related to jumping to conclusions. In this case, you jump to the worst possible conclusion in every scenario, no matter how improbable it is.

This cognitive distortion often comes with “what if” questions. What if he didn’t call because he got into an accident? What if she hasn’t arrived because she really didn’t want to spend time with me? What if I help this person and they end up betraying or abandoning me?

Several questions might follow in response to one event.

Example

What if my alarm doesn’t go off? What if then I’m late for the important meeting? What if I get fired after I’ve worked so hard for this job?

Personalization

Personalization leads you to believe that you’re responsible for events that, in reality, are completely or partially out of your control.

This cognitive distortion often results in you feeling guilty or assigning blame without contemplating all factors involved.

Example

Your child has an accident, and you blame yourself for allowing them to go to that party.

You feel that if your partner had woken earlier, you would have been ready on time for work.

With personalizing, you also take things personally.

Example

Your friend is talking about their personal beliefs regarding parenting, and you take their words as an attack against your parenting style.

Control fallacies

The word fallacy refers to an illusion, misconception, or error.

Control fallacies can go two opposite ways: You either feel responsible or in control of everything in your and other people’s lives, or you feel you have no control at all over anything in your life.

Example

You couldn’t complete a report that was due today. You immediately think, “Of course I couldn’t complete it! My boss is overworking me, and everyone was so loud today at the office. Who can get anything done like that?”

In this example, you place all control of your behavior on someone else or an external circumstance. This is an external control fallacy.

The other type of control fallacy is based on the belief that your actions and presence impact or control the lives of others.

Example

You think you make someone else happy or unhappy. You think all of their emotions are controlled directly or indirectly by your behaviors.

Fallacy of fairness

This cognitive distortion refers to measuring every behavior and situation on a scale of fairness. Finding that other people don’t assign the same value of fairness to the event makes you resentful.

In other words, you believe you know what’s fair and what isn’t, and it upsets you when other people disagree with you.

The fallacy of fairness will lead you to face conflict with certain people and situations because you feel the need for everything to be “fair” according to your own parameters.

But fairness is rarely absolute and can often be self-serving.

Example

You expect your partner to come home and massage your feet. It’s only “fair” since you spent all afternoon making them dinner.

But they arrive exhausted and only want to take a bath. They believe it’s “fair” to take a moment to relax from the day’s chaos, so they can pay full attention to you and enjoy your dinner instead of being distracted and tired.

They believe it’s “fair” to take a moment to relax from the day’s chaos, so they can pay full attention to you and enjoy your dinner instead of being distracted and tired.

Blaming

Blaming refers to making others responsible for how you feel.

“You made me feel bad” is what usually defines this cognitive distortion. However, even when others engage in hurtful behaviors, you’re still in control of how you feel in most situations.

The distortion comes from believing that others have the power to affect your life, even more so than yourself.

Example

Your partner comments on your new dress and you feel upset for the rest of the day. “You make me feel bad about myself,” you tell them.

Shoulds

As cognitive distortions, “should” statements are subjective ironclad rules you set for yourself and others without considering the specifics of a circumstance.

You tell yourself that things should be a certain way with no exceptions.

Example

You think people should always be on time, or that someone who is independent should also be self-sufficient and never ask for help.

When it comes to yourself, you might believe you should always make your bed, or you should always make people laugh.

“You should be better,” you constantly tell yourself.

When these things don’t happen — they really depend on many factors — you feel guilty, disappointed, let down, or frustrated.

You may believe you’re trying to motivate yourself with these statements, such as “I should go to the gym every day.”

However, when circumstances change, and you can’t do what you should, you become angry and upset. You got out of work late and couldn’t get to the gym, for example.

Emotional reasoning

Emotional reasoning leads you to believe that the way you feel is a reflection of reality. “I feel this way about this situation, hence it must be a fact,” defines this cognitive distortion.

Example

Feeling inadequate in a situation turns into, “I don’t belong anywhere.”

This cognitive distortion might also lead you to believe future events depend on how you feel.

Example

You may firmly believe something bad will happen today because you woke up feeling anxious.

You might also assess a random situation based on your emotional reaction. If someone says something that makes you angry, you immediately conclude that person is treating you poorly.

Fallacy of change

The fallacy of change has you expecting other people will change their ways to suit your expectations or needs, particularly when you pressure them enough.

Example

You want your partner to focus only on you, despite knowing that they’ve always been very social and value time with friends.

So, every time they go out, you let them know it’s not OK with you. Eventually, you know they will change their ways and want to stay home all the time.

Global labeling

Labeling or mislabeling refers to taking a single attribute and turning it into an absolute.

This happens when you judge and then define yourself or others based on an isolated event.

The labels assigned are usually negative and extreme.

Example

You see your new teammate applying makeup before a meeting, and you call them “shallow.” Or, they don’t submit a report on time, and you label them “useless.”

This is an extreme form of overgeneralization that leads you to judge an action without taking the context into account. This, in turn, leads you to see yourself and others in ways that might not be accurate.

Assigning labels to others can impact how you interact with them. This, in turn, could add friction to your relationships.

When you assign those labels to yourself, it can hurt your self-esteem and confidence, leading you to feel insecure and anxious.

Always being right

This desire turns into a cognitive distortion when it trumps everything else, including evidence and other people’s feelings.

In this cognitive distortion, you see your own opinions as facts of life. This is why you will go to great lengths to prove you’re right.

Example

You quarrel with your sibling about how your parents haven’t supported you enough. You’re convinced this was the case all the time, while your sibling believes it varied according to the situation.

Since your sibling doesn’t feel the same way, you become angry and say things that rub your sibling the wrong way.

You know they’re getting upset, but you continue the argument to prove your point.

Most irrational patterns of thought can be reversed once you’re aware of them. This applies to negative thinking, too.

Still, cognitive distortions sometimes go hand in hand with mental health conditions, such as personality disorders. This makes it more challenging to reframe.

Reaching out to a mental health professional can help if you feel the process is too overwhelming.

Meanwhile, try to remember that it’s not the events but your thoughts that upset you in many instances.

You might not be able to change the events, but you can work on redirecting your distorted thoughts.

Beginning with small changes can be helpful. Here are some tips:

1. Thinking about your thoughts

If an event is upsetting you, step away from it if you can and try to focus on what you’re telling yourself about the event.

2. Replacing absolutes

Once you focus on your thoughts and recognize a pattern, consider replacing statements such as “always” and “nothing” with “sometimes” and “this.”

3. Defining yourself and others

Try labeling the behavior. Instead of labeling yourself “lazy” because you didn’t clean today, consider: “I just didn’t clean today.” One action doesn’t have to define you.

4. Searching for positive aspects

Even if it’s challenging at first, what if you find at least three positive examples in each situation. It might not feel natural, but eventually, it may become a spontaneous habit.

5. Does evidence back up your negative thought?

Before concluding, consider asking, investigating, and questioning yourself and others to ensure you have as many facts as possible. If you can, make an extra effort to believe these facts.

If you can, make an extra effort to believe these facts.

Cognitive distortions are negative filters that impact how you see yourself and others.

When our thoughts are distorted, our emotions are, too. By becoming aware and redirecting these negative thoughts, you can significantly improve your mood and quality of life.

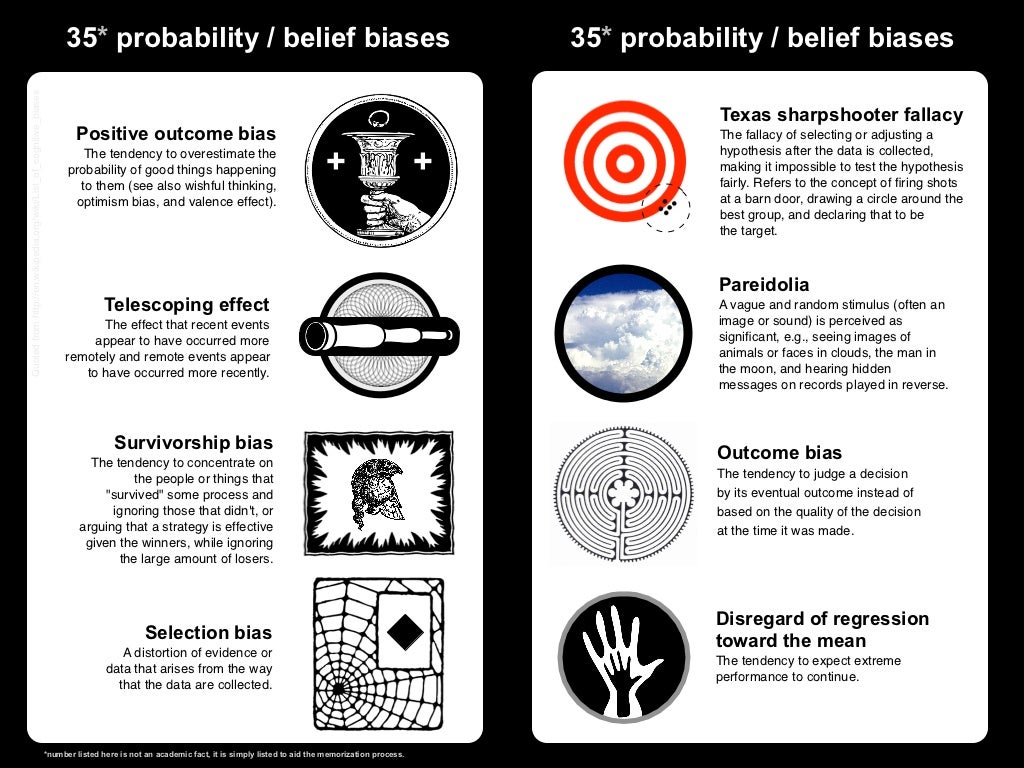

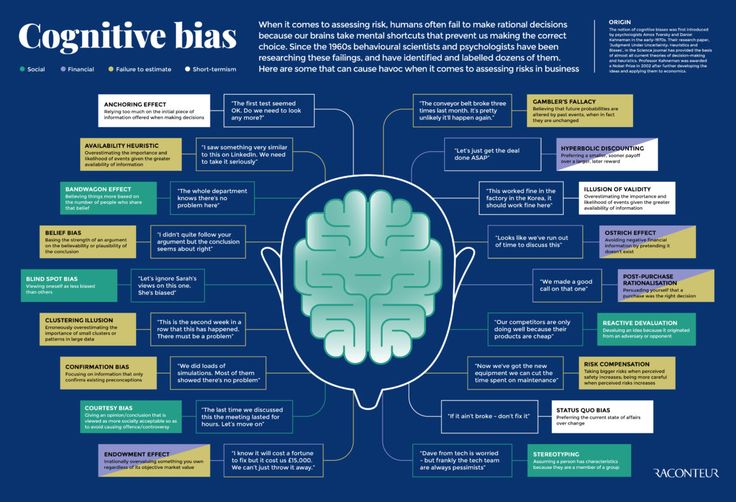

Top 15 cognitive biases | PSYCHOLOGIES

126,254

Knowing Yourself A Human Among Humans

Typically, our mind uses cognitive distortions to reinforce some kind of negative emotion or negative line of reasoning. The voice in our head sounds rational and authentic, but in reality only reinforces our poor opinion of ourselves.

For example, we say to ourselves, "I always fail when I try to do something new." This is an example of "black and white" thinking - with this cognitive distortion, we perceive the situation only in absolute categories: if we fail in one thing, then we are doomed to endure it in the future, in everything and always. nine0003

nine0003

If we add “I must be a complete loser” to these thoughts, this is an example of overgeneralization - such a cognitive distortion generalizes ordinary failure to the scale of our entire personality, we make it our essence.

Here are the main examples of cognitive distortions that are worth remembering and practicing, tracking them and responding to each in a more calm and measured way.

1. Filtering

We focus on the negative while filtering out all the positive aspects of the situation. Obsessed with an unpleasant detail, we lose objectivity, and reality is blurred and distorted. nine0003

2. Black and white thinking

With black and white thinking, we see everything either in black or in white, there can be no other shades. We must do everything perfectly or we will fail - there is no middle ground. We rush from one extreme to another, not allowing the idea that most situations and characters are complex, composite, with many shades.

3.

Overgeneralization

Overgeneralization With this cognitive distortion, we come to a conclusion based on a single aspect, a "piece" of what happened. If something bad happens once, we convince ourselves that it will happen again and again. We begin to see a single unpleasant event as part of an endless chain of defeats. nine0003

4. Jumping to conclusions

The other person hasn't said a word yet, and we already know exactly what he feels and why he behaves the way he does. In particular, we are confident that we can determine how people feel about us.

For example, we may conclude that someone does not love us, but we will not lift a finger to find out if this is true. Another example: we convince ourselves that things will go wrong, as if it were a fait accompli.

5. Injection

We live in anticipation of a catastrophe that is about to break out, ignoring the objective reality. The same can be said about the habit of minimizing and exaggerating. When we hear about a problem, we immediately turn on “what if? . .”: “If this happens to me? What if tragedy happens?

.”: “If this happens to me? What if tragedy happens?

We exaggerate the importance of minor events (say, our own mistake or someone else's achievement) or, conversely, mentally reduce an important event until it seems tiny (for example, our own desired qualities or the shortcomings of others). nine0003

6. Personification

With this cognitive distortion, we believe that the actions and words of others are a personal reaction to us, our words and actions. We also constantly compare ourselves to others, trying to figure out who is smarter, better looking, and so on.

In addition, we can consider ourselves the cause of some unpleasant event, for which we objectively do not bear any responsibility. For example, a skewed chain of reasoning might be: “We were late for dinner, so the hostess dried the meat. If only I had hurried my husband, this would not have happened. nine0003

7. False conclusion about control

If we feel that we are controlled from the outside, then we feel like a helpless victim of fate. The fallacy of control makes us responsible for the pain and happiness of everyone around us. "Why are not you happy? Is it because I did something wrong?

The fallacy of control makes us responsible for the pain and happiness of everyone around us. "Why are not you happy? Is it because I did something wrong?

8. False conclusion about fairness

We feel offended that we have been treated unfairly, but others may have a different point of view on this matter. Remember, as children, when things didn't go the way we wanted them to, adults would say, "Life isn't always fair." nine0003

Those of us who judge every situation "fairly" often end up feeling bad. Because life is sometimes "unfair" - not everything and not always develops in our favor, no matter how much we would like it.

9. Blame

We believe that other people are responsible for our pain, or vice versa, we blame ourselves for every problem. An example of such a cognitive distortion is expressed in the phrase: “You keep making me feel bad about myself, stop it!” No one can "make you think" or make you feel - we ourselves control our emotions and emotional reactions. nine0003

nine0003

10. "I (shouldn't)"

We have a list of ironclad rules about how we and the people around us should behave. Anyone who breaks one of the rules causes our anger, and we get angry at ourselves when we break them ourselves. We often try to motivate ourselves with what we should or shouldn't do, as if we're doomed to get punished before we do anything.

For example: “I have to go in for sports. I shouldn't be so lazy." “Must”, “must”, “should” are from the same series. The emotional consequence of this cognitive distortion is guilt. And when we use a “should” approach to other people, we often feel anger, impotent rage, frustration, and resentment. nine0003

11. Emotional arguments

We believe that what we feel must automatically be true. If we feel stupid or boring, then we really are. We take for granted how our unhealthy emotions reflect reality. "That's how I feel, so it must be true."

12. False conclusion about change

We tend to expect others to change to suit our desires and demands. You just need to press or cajole properly. The drive to change others is so persistent because we feel like our hopes and happiness depend entirely on those around us. nine0003

You just need to press or cajole properly. The drive to change others is so persistent because we feel like our hopes and happiness depend entirely on those around us. nine0003

13. Labeling

We generalize one or two qualities to a global judgment, we take the generalization to the extreme. This cognitive bias is also called labeling. Instead of analyzing the error in the context of a particular situation, we attach an unhealthy label to ourselves. For example, we say “I am a loser” after failing in some business.

Faced with the unpleasant consequences of someone's behavior, we can attach a label to the person who behaved in such a way

“He/she constantly throws his children at strangers” - about a parent whose children spend every day in kindergarten. Such a label is usually charged with negative emotions.

14. Desire to always be right

All our life we try to prove that our opinions and actions are the most correct. Being wrong is unthinkable, so we go to great lengths to demonstrate that we are right. “I don’t care if my words hurt you, I will still prove to you that I am right and win this argument.” The consciousness of being right for many is more important than the feelings of people around, including even those closest to them. nine0003

Being wrong is unthinkable, so we go to great lengths to demonstrate that we are right. “I don’t care if my words hurt you, I will still prove to you that I am right and win this argument.” The consciousness of being right for many is more important than the feelings of people around, including even those closest to them. nine0003

15. False conclusion about the reward in heaven

We are sure that our sacrifices and caring for others to the detriment of our own interests will surely pay off - as if someone invisible is keeping score. And we feel bitter disappointment when we do not receive the long-awaited reward.

Text: Ksenia Tatarnikova Photo Source: Unsplash

New on the site

“I have always made special New Year gifts for my friends, but now I have neither the strength nor the desire to do so. Why?"

"After the sudden death of my husband, I can hear his breathing at night"

A promising cure for depression has been found. The secret is in the combination of a drug and a computer program

A man on the verge of a nervous breakdown: how to understand that a loved one is depressed — 14 signs

“Being rejected is their main fear”: answering basic questions about eating disorders

literature that will decorate the New Year holidays for you and your child

“I told my mother about my father’s betrayal and I hate him for betrayal”

How to spend the New Year holidays with mental health benefits: 6 tips

15 cognitive distortions / Sudo Null IT News

This article is about how to distinguish reliable information from distorted information, and how to correctly present information in order to convince other people.

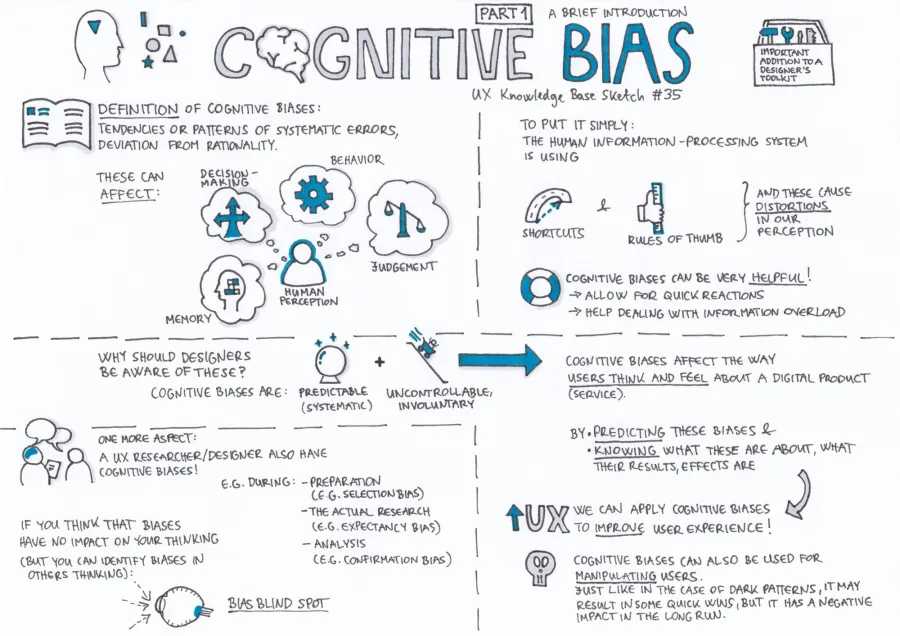

Let's start with the fact that people do not always think rationally. This is a given, which is due to the principles of our intellect, developed in the process of evolution. Conditionally, let's imagine the mind divided into two Systems. The device of the mind is not so simple, but the described simplification will make it possible to understand the causes of distortions. The first system generates solutions and hypotheses quickly "if we touch a hot object, we will withdraw our hand." The second, makes decisions by logical reasoning. The first System generates hypotheses, and the second accepts or rejects them. This way of thinking is slow and energy-consuming. Logical reasoning is used by people less often and requires more effort. This is the cause of most cognitive distortions. nine0003

Thus, the “I agree by default” checkbox allowed to increase the number of those who agree to donate to 86% in Sweden, while in Denmark, where, when obtaining rights, you need to give consent yourself, that is, make an informed choice, the number of those who agree to donate is 4% .

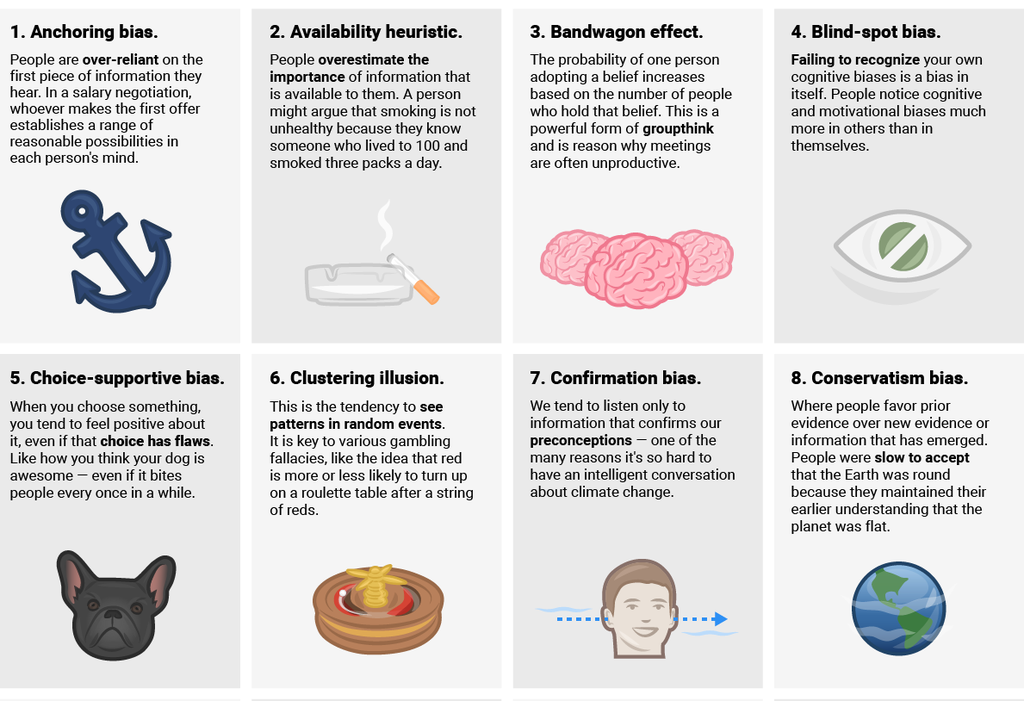

Consider some of the cognitive distortions:

Priming

Context shapes the direction of thought. If the conversation is about food, recipes, taste, etc., then the word "m ... o" most people will continue as meat than soap. Experiments show that when people are shown images or words associated with old age, people begin to walk more slowly. Money-minded people become independent and selfish, and are less likely to help others. This is due to the fact that the image gives rise to associations that shape our behavior. The priming effect is used in branding. Name without hesitation the name of a fast food restaurant, or the most fashionable mobile phone. nine0003

Illusion of truth

The more recognizable the image, the more the statement is associated with security and truth. Thus, the frequent repetition of a lie makes the deception plausible. Truth is like feeling familiar. Recognizable = lightness. The more contrast the color, the simpler the perception, the more plausible the statement. Simple words convince better than complex ones. Poems are perceived as information containing deep meaning. The font and rhythm of prose influence the sense of believability.

The more contrast the color, the simpler the perception, the more plausible the statement. Simple words convince better than complex ones. Poems are perceived as information containing deep meaning. The font and rhythm of prose influence the sense of believability.

Cognitive tension mobilizes System 2. If you want people to start analyzing information, use poorly readable text, blurry pictures, etc.

Context sets credibility. Answer the question “how many animals of each type did Moses take with him on the ark?”. Most will answer 2, not noticing that the ark was built by Noah, and Moses is present in another biblical story. If you put Steve Jobs in the place of Moses, people will immediately notice the inconsistency.

Snap effect

The starting point affects our estimate. If you ask 2 questions to groups of people "The height of the sequoia is more or less than 365 meters, and what is the height, in your opinion?" and “The height of the sequoia is more or less than 55 meters, and what is the height, in your opinion?” people will give different ratings. The numbers 365 and 55 are taken randomly. Those who were given a reference of 365 would, on average, give an answer of 257 meters, and those who were given a reference of 55 would answer 86 meters. nine0003

The numbers 365 and 55 are taken randomly. Those who were given a reference of 365 would, on average, give an answer of 257 meters, and those who were given a reference of 55 would answer 86 meters. nine0003

Binding example - restriction of the offer "no more than X units of goods in one hand."

Retrospective distortion

People change their point of view with a transfer to the perception of the past. If an event has occurred, a person overestimates the probability of his own forecast in the past and vice versa. The illusion of understanding the past gives rise to the illusion of a predictable future. People wonder how it was possible to make such an obvious mistake, forgetting that at the moment of making the decision the mistake was not obvious. nine0003

Ignoring statistics and random events

People strive to find causal relationships even where there is no connection. The sequence of events is endowed with a causal relationship. The illusion of skill, caused by the luck of brokers in the stock market, is perceived as professionalism. In a coin toss, the sequences O, O, O, O, P, and O, P, O, P, P are equally likely, but people think the second sequence is more likely. “He had daughters born 3 times, now a boy will be born” or “He has a light hand, Sergey has already scored 2 goals today, I will give him a pass to score the third one.” nine0003

The illusion of skill, caused by the luck of brokers in the stock market, is perceived as professionalism. In a coin toss, the sequences O, O, O, O, P, and O, P, O, P, P are equally likely, but people think the second sequence is more likely. “He had daughters born 3 times, now a boy will be born” or “He has a light hand, Sergey has already scored 2 goals today, I will give him a pass to score the third one.” nine0003

Regression to the mean

The result is made up of 2 factors: professionalism and luck. If an athlete performed very well, then with a high degree of confidence, we can say that he is a professional and the day was very successful, and vice versa. But the level of luck tends to average as the number of attempts increases. In subsequent attempts, the likelihood that the athlete will perform worse than on a good day is greater, and vice versa. This explains the illusion of the effectiveness of punishment. It seems to people that the punishment affects the improvement of the future result, although this is just a regression to the mean. nine0003

nine0003

Distortions of probabilistic events

Rare events that evoke vivid images and associations attract more attention and people exaggerate the likelihood of their occurrence. Examples are air crashes, terrorist attacks, cataclysms, etc. The media play a role in evoking such images. People see less value in products that seem risky and are willing to pay extra to minimize the risk of rare events. If a rare event does not cause vivid images, then it is ignored. A rare event needs to be “overloaded with details” in order for us to present it and give it more weight. nine0003

People ignore prior probability and judge by stereotype or reason. Man does not derive the particular from the general, but he derives the general from the particular. The associative image prevails over statistics. Probability is harder to estimate than the "how many of" value.

Imagine a young man named Sergei. Sergey wears glasses, is an introvert, understands technology and has Linux on his computer. Arrange the assumptions about Sergey in descending order: 1) Sergey is a designer 2) Sergey graduated from a technical university and a programmer 3) Sergey is a waiter 4) Sergey is a programmer. Points 2 and 4 are important here. Most will place the answer 2 above 4, but this is a mistake. Programmers who graduated from a technical university make up only a fraction of programmers. Therefore, the likelihood that Sergey is just a programmer is higher. People ignore the prior probability and choose a vivid description, since a vivid description is easier to present. nine0003

Arrange the assumptions about Sergey in descending order: 1) Sergey is a designer 2) Sergey graduated from a technical university and a programmer 3) Sergey is a waiter 4) Sergey is a programmer. Points 2 and 4 are important here. Most will place the answer 2 above 4, but this is a mistake. Programmers who graduated from a technical university make up only a fraction of programmers. Therefore, the likelihood that Sergey is just a programmer is higher. People ignore the prior probability and choose a vivid description, since a vivid description is easier to present. nine0003

A common mistake is manipulation on small samples. As a result of the study, it was found that small schools predominate among schools with high academic performance. Casual explanations were found for this, and a large amount of money was invested in the creation of such schools. The error was that with a small sample (the number of students), “anomalous situations” are more likely. It is more likely that all students are smart or stupid. The picture is similar among oncological diseases. Both the healthiest and the least healthy are residents of small settlements, but this is due to the probability of an event in a small sample, and not to clean air or hard work. nine0003

The picture is similar among oncological diseases. Both the healthiest and the least healthy are residents of small settlements, but this is due to the probability of an event in a small sample, and not to clean air or hard work. nine0003

Low probability events are exaggerated and high probability events are downplayed.

At the same time, psychologically the transition of 0–5% (the appearance of a chance) and 99–100% (the onset of uniqueness) is more significant than the transition of 50–55%.

Mean estimate distortion. Less is better.

If people are offered 2 service sets, where one consists only of items without defects, and the other of the same number of items without defects, to which items with small defects are added, then the majority will value a large set more than a small one. But when evaluated separately, people will appreciate a large service containing defects cheaper than a small one. This is due to the fact that people estimate the cost, not on the basis of the principle of integrating the cost of individual objects, but on the basis of the average cost of parts. So, a set of expensive pen + Chinese pen will be less valuable than just an expensive pen. nine0003

So, a set of expensive pen + Chinese pen will be less valuable than just an expensive pen. nine0003

Reference point and loss effect

The desire to lose is stronger than the desire to win. For example, for games involving money, the coefficient of the gain-to-loss ratio is 2. For health matters, the coefficient is 50, which indicates sensitivity to losses. People are less likely to take risks to win and more likely to take risks when losses are imminent. This is the basis of the insurance business model. Danger is more important than opportunity. Due to the difference in the price of losses, the poor are more willing to buy insurance from the rich, concessions are “charged up” in negotiations, etc. Playing with many attempts minimizes the effect of loss aversion (it is easier to go into business if you know that there will be a second chance). nine0003

The expected value does not depend linearly with the increase in payoff. This is described on a logarithmic scale. In this case, it is not the quantitative state that is important, but the degree of change. An increase in wealth from $1 million to $10 million is emotionally more significant than an increase from $10 million to $20 million, but comparable to an increase from $10 million to $100 million.

In this case, it is not the quantitative state that is important, but the degree of change. An increase in wealth from $1 million to $10 million is emotionally more significant than an increase from $10 million to $20 million, but comparable to an increase from $10 million to $100 million.

The possession effect is that things that are meant for personal use and that evoke an emotional response cause a greater sense of loss. How much are you willing to sell your favorite mug or concert tickets for your favorite band? But if the item is originally intended for sale or exchange, there is no sense of loss. So, if a person is offered an equivalent choice of additional salary or vacation, after the first choice, it is harder to change position, since there is a starting point and the change is perceived as a loss plus gain, where the loss has more weight. nine0003

Irrecoverable loss error - it is easier to continue investing in an unpromising business than to fix a loss.

Regret is stronger if caused by action rather than inaction (Sergey sold dollars and bought rubles in June 1998 or Sergey did not buy dollars). The unusual situation increases regret (Sergei decided to give a ride to a fellow traveler, although he never did this and was robbed).

The unusual situation increases regret (Sergei decided to give a ride to a fellow traveler, although he never did this and was robbed).

Optimist's mistake

My own experience is understandable. Because of this, a planning error occurs, people plan based on available data, and not statistical facts. The fallacy of opinion is that people think they are smarter than the rest. The neglect of competition is due to the effect of exclusivity. Due to the fact that their own experience is understandable, people tend to exaggerate their own contribution to the common cause. A useful technique for overcoming the error of an optimist is a “lifetime epicrisis”, during which a failure is presented and the reasons that led to it are analyzed. nine0003

Halo effect

People project an assessment of the known qualities of an object onto unknown qualities. A good speaker is perceived as a professional, a pleasant person is presented as frank, etc. Thus, competence is associated with strength and reliability, and people with a pronounced chin and a slight smile are perceived as more competent. Properties are also projected onto surrounding objects, so to increase the rating it is beneficial for a politician to meet with champions and award winners and avoid debates with unpopular colleagues. The professionalism of a manager is measured by the financial performance of the company, although according to research, the correlation between leadership skills and company success is 0.3. Competent management guarantees success with a probability of 60%. nine0003

Thus, competence is associated with strength and reliability, and people with a pronounced chin and a slight smile are perceived as more competent. Properties are also projected onto surrounding objects, so to increase the rating it is beneficial for a politician to meet with champions and award winners and avoid debates with unpopular colleagues. The professionalism of a manager is measured by the financial performance of the company, although according to research, the correlation between leadership skills and company success is 0.3. Competent management guarantees success with a probability of 60%. nine0003

Information delivery effect

90% accuracy is perceived as more positive than a 10% error claim.

The wording changes the perception. Imagine 2 essentially identical statements of the question “would you agree to a game with a 10% chance of winning $95 and a 90% chance of losing 5” or “Will you pay $5 for a lottery where 10% of the tickets win $100?”.

People would be more willing to refuse a “discount for…” than agree to a “surcharge for…”.

A kilometer per liter of gasoline distorts consumption (counting practice in the USA). It is more correct to count in liters per kilometer. nine0003

A reminder that people are being watched makes them behave more decently.

People feel free from responsibility if they believe that others are aware of the situation.

Confidence in the statement decreases with the increase in the number of arguments.

It is better to "keep 50%" than "lose 50%" of the state.

Better "95% patient survival" than "5% patient mortality".

Neglect of quantity and ranking of significance

When deciding on importance, people ignore quantitative indicators. When conducting a charity campaign, raising money to save 100 tigers or 10,000 tigers will not affect the average amount of donations.

People tend to determine significance based on the place of an image within a category. Tigers rank high within the “animals” category, and migraine sufferers rank low among other sick people (although migraine ruins people’s lives more often than other “significant” but rare diseases). If fundraising for endangered tigers and for people with migraine is done independently, the average donation for tigers will be higher. But if both of these proposals are placed in the same context, then donations for people will become higher, since the position of the category “people” is higher than the position of the category “animals”. nine0003

Tigers rank high within the “animals” category, and migraine sufferers rank low among other sick people (although migraine ruins people’s lives more often than other “significant” but rare diseases). If fundraising for endangered tigers and for people with migraine is done independently, the average donation for tigers will be higher. But if both of these proposals are placed in the same context, then donations for people will become higher, since the position of the category “people” is higher than the position of the category “animals”. nine0003

The effect of neglecting the denominator is that it is psychologically better to have an 8 in 100 chance than a 1 in 10 chance. The 0.001% risk of a child dying is felt to be less worth considering than the death of ten children in a million. A disease that kills 186 people out of 1,000 seems more dangerous than a disease that kills 24% of people, and than one that kills 24 out of 100. The expression "every year the mentally ill kill 1 thousand people" has a greater effect than "the risk of death at the hands of a mentally ill person is 0. 00036%, which is comparable to the risk of death at the hands of a normal person.” nine0003

00036%, which is comparable to the risk of death at the hands of a normal person.” nine0003

Substitution of questions

Difficult questions are replaced by simple ones. When people are asked "Are you happy?", the person is answering the question "What mood am I in". Will the company be successful? is replaced with “do you like the technology, the team, etc.”. The answer is affected by the priming effect if you ask "how many dates?", And then "are you happy?" then the second question will be replaced by the first.

People tend to replace the general with the particular.

The illusion of focus creates a distortion in favor of goods and activities that are attractive at first (cars, telephone) than activities that take more time and excitement (dance). The focusing effect amplifies the damaging effort directed at the subject's weak spot. nine0003

Ignore duration

Experiments have shown that people ignore the duration of exposure.